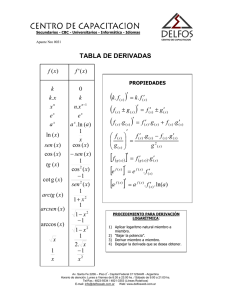

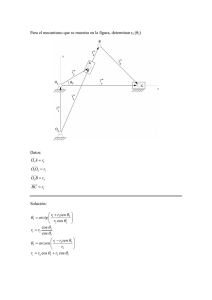

Untitled-7 1 6/23/09 2:03:14 PM Cálculo 2 0-Prelim L2.indd i 1/12/09 18:04:21 REVISORES TÉCNICOS MÉXICO José de Jesús Ángel Ángel Universidad Anáhuac Norte Miguel Ángel Arredondo Morales Universidad Iberoamericana León Víctor Armando Bustos Peter Instituto Tecnológico y de Estudio Superiores de Monterrey, Campus Toluca Aureliano Castro Castro Universidad Autónoma de Sinaloa Javier Franco Chacón Tecnológico de Monterrey, Campus Chihuahua Sergio Fuentes Martínez Universidad Anáhuac México Norte Enrique González Acosta Instituto Tecnológico y de Estudios Superiores de Monterrey, Campus Sonora Norte Miguel Ángel López Mariño Instituto Tecnológico y de Estudios Superiores de Monterrey, Campus Central de Veracruz Eleazar Luna Barraza Universidad Autónoma de Sinaloa Tomás Narciso Ocampo Paz Instituto Tecnológico de Toluca Velia Pérez González Universidad Autónoma de Chihuahua Ignacio Ramírez Vargas Instituto Tecnológico y de Estudios Superiores de Monterrey, Campus Hidalgo Héctor Selley Universidad Anáhuac Norte Jorge Alberto Torres Guillén Universidad de Guadalajara Enrique Zamora Gallardo Universidad Anáhuac Norte COLOMBIA Petr Zhevandrov Universidad de La Sabana Jorge Augusto Pérez Alcázar Universidad EAN Liliana Barreto Arciniegas Pontificia Universidad Javeriana Gustavo de J. Castañeda Ramírez Universidad EAFIT Jairo Villegas G. Universidad EAFIT PERÚ Carlos Enrique Peralta Santa Cruz Universidad Continental de Ciencias e Ingeniería 0-Prelim L2.indd ii 1/12/09 18:04:21 Cálculo 2 de varias variables Novena edición Ron Larson The Pennsylvania State University The Behrend College Bruce H. Edwards University of Florida Revisión técnica Marlene Aguilar Abalo Instituto Tecnológico y de Estudios Superiores de Monterrey, Campus Ciudad de México José Job Flores Godoy Universidad Iberoamericana Joel Ibarra Escutia Instituto Tecnológico de Toluca Linda M. Medina Herrera Instituto Tecnológico y de Estudios Superiores de Monterrey, Campus Ciudad de México MÉXICO • BOGOTÁ • BUENOS AIRES • CARACAS • GUATEMALA • MADRID • NUEVA YORK SAN JUAN • SANTIAGO • SÃO PAULO • AUCKLAND • LONDRES • MILÁN • MONTREAL NUEVA DELHI • SAN FRANCISCO • SINGAPUR • ST. LOUIS • SIDNEY • TORONTO 0-Prelim L2.indd iii 1/12/09 18:04:21 Director Higher Education: Miguel Ángel Toledo Castellanos Editor sponsor: Pablo E. Roig Vázquez Coordinadora editorial: Marcela I. Rocha Martínez Editora de desarrollo: Ana L. Delgado Rodríguez Supervisor de producción: Zeferino García García Traducción: Joel Ibarra Escutia, Ángel Hernández Fernández, Gabriel Nagore Cázares, Sergio Antonio Durán Reyes CÁLCULO 2 DE VARIAS VARIABLES Novena edición Prohibida la reproducción total o parcial de esta obra, por cualquier medio, sin autorización escrita del editor. DERECHOS RESERVADOS © 2010, respecto a la novena edición en español por McGRAW-HILL/INTERAMERICANA EDITORES, S.A. DE C.V. A Subsidiary of The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. Edificio Punta Santa Fe Prolongación Paseo de la Reforma Núm. 1015, Torre A Piso 17, Colonia Desarrollo Santa Fe Delegación Álvaro Obregón C.P. 01376, México, D.F. Miembro de la Cámara Nacional de la Industria Editorial Mexicana, Reg. Núm. 736 ISBN 978-970-10-7134-2 Traducido de la novena edición de: Calculus. Copyright © 2010 by Brooks/Cole, a Cengage Learning Company. All rights reserved. ISBN-13: 978-1-4390-3033-2 TI es una marca registrada de Texas Instruments, Inc. Mathematica es una marca registrada de Wolfram Research, Inc. Maple es una marca registrada de Waterloo Maple, Inc. 1234567890 109876543210 Impreso en China Printed in China 0-Prelim L2.indd iv 1/12/09 18:04:21 C ontenido Unas palabras de los autores Agradecimientos Características CAPÍTULO 10 Cónicas, ecuaciones paramétricas y coordenadas polares 10.1 Cónicas y cálculo 10.2 Curvas planas y ecuaciones paramétricas PROYECTO DE TRABAJO: Cicloides 10.3 Ecuaciones paramétricas y cálculo 10.4 Coordenadas polares y gráficas polares PROYECTO DE TRABAJO: Arte anamórfico 10.5 Área y longitud de arco en coordenadas polares 10.6 Ecuaciones polares de las cónicas y leyes de Kepler Ejercicios de repaso SP Solución de problemas CAPÍTULO 11 Vectores y la geometría del espacio 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 11.5 Vectores en el plano Coordenadas y vectores en el espacio El producto escalar de dos vectores El producto vectorial de dos vectores en el espacio Rectas y planos en el espacio PROYECTO DE TRABAJO: Distancias en el espacio 11.6 Superficies en el espacio 11.7 Coordenadas cilíndricas y esféricas Ejercicios de repaso SP Solución de problemas CAPÍTULO 12 Funciones vectoriales 12.1 Funciones vectoriales PROYECTO DE TRABAJO: Bruja de Agnesi 12.2 Derivación e integración de funciones vectoriales 12.3 Velocidad y aceleración 12.4 Vectores tangentes y vectores normales 12.5 Longitud de arco y curvatura Ejercicios de repaso SP Solución de problemas ix x xii 695 696 711 720 721 731 740 741 750 758 761 763 764 775 783 792 800 811 812 822 829 831 833 834 841 842 850 859 869 881 883 v 0-Prelim L2.indd v 1/12/09 18:04:22 vi Contenido CAPÍTULO 13 Funciones de varias variables 13.1 13.2 13.3 Introducción a las funciones de varias variables Límites y continuidad Derivadas parciales PROYECTO DE TRABAJO: Franjas de Moiré 13.4 Diferenciales 13.5 Regla de la cadena para funciones de varias variables 13.6 Derivadas direccionales y gradientes 13.7 Planos tangentes y rectas normales PROYECTO DE TRABAJO: Flora silvestre 13.8 Extremos de funciones de dos variables 13.9 Aplicaciones de los extremos de funciones de dos variables PROYECTO DE TRABAJO: Construcción de un oleoducto 13.10 Multiplicadores de Lagrange Ejercicios de repaso SP Solución de problemas CAPÍTULO 14 962 969 970 978 981 983 14.1 14.2 14.3 14.4 984 992 1004 1012 1019 1020 1026 1027 1038 1044 1045 1052 1055 Análisis vectorial 15.1 15.2 15.3 Campos vectoriales Integrales de línea Campos vectoriales conservativos e independencia de la trayectoria 15.4 Teorema de Green PROYECTO DE TRABAJO: Funciones hiperbólicas y trigonométricas 15.5 Superficies paramétricas 15.6 Integrales de superficie PROYECTO DE TRABAJO: Hiperboloide de una hoja 15.7 Teorema de la divergencia 0-Prelim L2.indd vi 886 898 908 917 918 925 933 945 953 954 Integración múltiple Integrales iteradas y área en el plano Integrales dobles y volumen Cambio de variables: coordenadas polares Centro de masa y momentos de inercia PROYECTO DE TRABAJO: Centro de presión sobre una vela 14.5 Área de una superficie PROYECTO DE TRABAJO: Capilaridad 14.6 Integrales triples y aplicaciones 14.7 Integrales triples en coordenadas cilíndricas y esféricas PROYECTO DE TRABAJO: Esferas deformadas 14.8 Cambio de variables: jacobianos Ejercicios de repaso SP Solución de problemas CAPÍTULO 15 885 1057 1058 1069 1083 1093 1101 1102 1112 1123 1124 1/12/09 18:04:22 Contenido 15.8 Teorema de Stokes Ejercicios de repaso PROYECTO DE TRABAJO: El planímetro SP Solución de problemas 0-Prelim L2.indd vii vii 1132 1138 1140 1141 Apéndice A Demostración de teoremas seleccionados A-2 Apéndice B Tablas de integración A-4 Soluciones de los ejercicios impares Índice analítico A-9 I-57 1/12/09 18:04:22 U nas palabras de los autores ¡Bienvenido a la novena edición de Cálculo! Nos enorgullece ofrecerle una nueva versión revisada de nuestro libro de texto. Mucho ha cambiado desde que escribimos la primera edición hace más de 35 años. En cada edición los hemos escuchado a ustedes, esto es, nuestros usuarios, y hemos incorporado muchas de sus sugerencias para mejorar el libro. A lo largo de los años, nuestro objetivo ha sido siempre escribir con precisión y de manera legible conceptos fundamentales del cálculo, claramente definidos y demostrados. Al escribir para estudiantes, nos hemos esforzado en ofrecer características y materiales que desarrollen las habilidades de todos los tipos de estudiantes. En cuanto a los profesores, nos enfocamos en proporcionar un instrumento de enseñanza amplio que emplea técnicas pedagógicas probadas, y les damos libertad para que usen en forma más eficiente el tiempo en el salón de clase. También hemos agregado en esta edición una nueva característica denominada ejercicios Para discusión. Estos problemas conceptuales sintetizan los aspectos clave y proporcionan a los estudiantes mejor comprensión de cada uno de los conceptos de sección. Los ejercicios Para discusión son excelentes para esa actividad en el salón de clase o en la preparación de exámenes, y a los profesores puede resultarles valioso integrar estos problemas dentro de su repaso de la sección. Éstas y otras nuevas características se unen a nuestra pedagogía probada en el tiempo, con la meta de permitir a los estudiantes y profesores hacer el mejor uso del libro. Esperamos que disfrute la novena edición de Cálculo. Como siempre, serán bienvenidos los comentarios y sugerencias para continuar mejorando la obra. Ron Larson Bruce H. Edwards ix 0-Prelim L2.indd ix 1/12/09 18:04:22 A gradecimientos Nos gustaría dar las gracias a muchas personas que nos ayudaron en varias etapas de este proyecto a lo largo de los últimos 35 años. Su estímulo, críticas y sugerencias han sido invaluables. Revisores de la novena edición Ray Cannon, Baylor University Sadeq Elbaneh, Buffalo State College J. Fasteen, Portland State University Audrey Gillant, Binghamton University Sudhir Goel, Valdosta State University Marcia Kemen, Wentworth Institute of Technology Ibrahima Khalil Kaba, Embry Riddle Aeronautical University Jean-Baptiste Meilhan, University of California Riverside Catherine Moushon, Elgin Community College Charles Odion, Houston Community College Greg Oman, The Ohio State University Dennis Pence, Western Michigan University Jonathan Prewett, University of Wyoming Lori Dunlop Pyle, University of Central Florida Aaron Robertson, Colgate University Matthew D. Sosa, The Pennsylvania State University William T. Trotter, Georgia Institute of Technology Dr. Draga Vidakovic, Georgia State University Jay Wiestling, Palomar College Jianping Zhu, University of Texas at Arlington Miembros del Comité de Asesores de la novena edición Jim Braselton, Georgia Southern University; Sien Deng, Northern Illinois University; Dimitar Grantcharov, University of Texas, Arlington; Dale Hughes, Johnson County Community College; Dr. Philippe B. Laval, Kennesaw State University; Kouok Law, Georgia Perimeter College, Clarkson Campus; Mara D. Neusel, Texas Tech University; Charlotte Newsom, Tidewater Community College, Virginia Beach Campus; Donald W. Orr, Miami Dade College, Kendall Campus; Jude Socrates, Pasadena City College; Betty Travis, University of Texas at San Antonio; Kuppalapalle Vajravelu, University of Central Florida Revisores de ediciones anteriores Stan Adamski, Owens Community College; Alexander Arhangelskii, Ohio University; Seth G. Armstrong, Southern Utah University; Jim Ball, Indiana State University; Marcelle Bessman, Jacksonville University; Linda A. Bolte, Eastern Washington University; James Braselton, Georgia Southern University; Harvey Braverman, Middlesex County College; Tim Chappell, Penn Valley Community College; Oiyin Pauline Chow, Harrisburg Area Community College; Julie M. Clark, Hollins University; P.S. Crooke, Vanderbilt University; x 0-Prelim L2.indd x 1/12/09 18:04:22 Agradecimientos xi Jim Dotzler, Nassau Community College; Murray Eisenberg, University of Massachusetts at Amherst; Donna Flint, South Dakota State University; Michael Frantz, University of La Verne; Sudhir Goel, Valdosta State University; Arek Goetz, San Francisco State University; Donna J. Gorton, Butler County Community College; John Gosselin, University of Georgia; Shahryar Heydari, Piedmont College; Guy Hogan, Norfolk State University; Ashok Kumar, Valdosta State University; Kevin J. Leith, Albuquerque Community College; Douglas B. Meade, University of South Carolina; Teri Murphy, University of Oklahoma; Darren Narayan, Rochester Institute of Technology; Susan A. Natale, The Ursuline School, NY; Terence H. Perciante, Wheaton College; James Pommersheim, Reed College; Leland E. Rogers, Pepperdine University; Paul Seeburger, Monroe Community College; Edith A. Silver, Mercer County Community College; Howard Speier, Chandler-Gilbert Community College; Desmond Stephens, Florida A&M University; Jianzhong Su, University of Texas at Arlington; Patrick Ward, Illinois Central College; Diane Zych, Erie Community College Muchas gracias a Robert Hostetler, de The Behrend College, en The Pennsylvania State University, y a David Heyd, de la misma institución, por sus importantes contribuciones a las ediciones previas de este texto. Una nota especial de agradecimiento a los profesores que respondieron nuestra encuesta y a los más de dos millones de estudiantes que han usado las ediciones anteriores de la obra. También quisiéramos agradecer al personal de Larson Texts, Inc., que apoyó en la preparación del manuscrito, realizó el diseño editorial, levantó la tipografía y leyó las pruebas de las páginas y suplementos en la edición en inglés. En el ámbito personal, estamos agradecidos con nuestras esposas, Deanna Gilbert Larson y Consuelo Edwards, por su amor, paciencia y apoyo. Además, una nota especial de gratitud para R. Scott O’Neil. Si usted tiene sugerencias para mejorar este texto, por favor siéntanse con la libertad de escribirnos. A lo largo de los años hemos recibido muchos comentarios útiles tanto de los profesores como de los estudiantes, y los valoramos sobremanera. Ron Larson Bruce H. Edwards 0-Prelim L2.indd xi 1/12/09 18:04:22 C aracterísticas Herramientas pedagógicas PARA DISCUSIÓN Para discusión 72. ¡NUEVO! Los ejercicios para discusión que aparecen ahora en cada sección sintetizan los conceptos principales de cada una y muestran a los estudiantes cómo se relacionan los temas. A menudo constituyen problemas de varias partes que contienen aspectos conceptuales y no computacionales, y que pueden utilizarse en discusiones de clase o en la preparación de exámenes. y f B C A D E x a) ¿Entre qué par de puntos consecutivos es mayor la razón de cambio promedio de la función? b) ¿La razón de cambio promedio de ƒ entre A y B es mayor o menor que el la razón de cambio instantáneo en B? c) Trazar una recta tangente a la gráfica entre los puntos C y D cuya pendiente sea igual a la razón de cambio promedio de la función entre C y D. Desarrollo de conceptos 11. Utilizar la gráfica para responder a las siguientes preguntas. Considerar la longitud de la gráfica de f(x) 5/x, desde (1, 5) hasta (5, 1): y y (1, 5) (1, 5) 5 5 4 4 DESARROLLO DE CONCEPTOS 3 3 2 (5, 1) 2 (5, 1) 1 1 x x 1 2 3 4 5 1 2 3 4 5 a) Estimar la longitud de la curva mediante el cálculo de la distancia entre sus extremos, como se muestra en la primera figura. b) Estimar la longitud de la curva mediante el cálculo de las longitudes de los cuatro segmentos de recta, como se muestra en la segunda figura. c) Describir cómo se podría continuar con este proceso a fin de obtener una aproximación más exacta de la longitud de la curva. Los ejercicios de desarrollo de conceptos son preguntas diseñadas para evaluar la comprensión de los estudiantes en torno a los conceptos básicos de cada sección. Estos ejercicios animan a los estudiantes a verbalizar y escribir respuestas, lo que promueve habilidades de comunicación técnica que serán invaluables en sus futuras carreras. AYUDAS DE ESTUDIO Las ayudas de estudio distinguen errores comunes, indican casos especiales que pueden provocar confusión, y amplían a conceptos importantes. Estas ayudas proporcionan a los estudiantes información puntual, similar a los comentarios del profesor en clase. EJEMPLO 1 Levantamiento de un objeto Determinar el trabajo realizado al levantar un objeto de 50 libras a 4 pies. Solución La magnitud de la fuerza requerida F es el peso del objeto, como se muestra en la figura 7.48. Así, el trabajo realizado al levantar el objeto 4 pies es W FD Trabajo (fuerza)(distancia). 50S4D Fuerza 50 libras, distancia 4 pies. 200 libras-pies. AYUDA DE ESTUDIO Cuando se use la definición para encontrar la derivada de una función, la clave consiste en volver a expresar el cociente incremental (o cociente de diferencias), de manera que $x no aparezca como factor del denominador. AYUDA DE ESTUDIO El ejemplo 3 también se puede resolver sin hacer uso de la regla de la cadena, si se observa que y x6 3x4 3x2 1 AYUDA DE ESTUDIO Tener en cuenta que se puede comprobar la respuesta de un problema de integración al derivar la C l j l 7 EJEMPLOS A lo largo del texto, se trabajan ejemplos paso a paso, que muestran los procedimientos y técnicas para resolver problemas, y dan a los estudiantes una comprensión amplia de los conceptos del cálculo. xii 0-Prelim L2.indd xii 1/12/09 18:04:22 Características xiii EJERCICIOS La práctica hace al maestro. Los ejercicios son con frecuencia el primer lugar que consultan los estudiantes en un libro de texto. Los autores han dedicado mucho tiempo analizándolos y revisándolos; el resultado es un completo y sólido conjunto de ejercicios de diferentes tipos y niveles de dificultad al final de cada sección para considerar todos los estilos de aprendizaje de los estudiantes. 4.3 Ejercicios En los ejercicios 1 y 2, utilizar el ejemplo 1 como modelo para evaluar el límite n lím O nm@ i1 En los ejercicios 13 a 22, formular una integral definida que produce el área de la región. (No evaluar la integral.) 13. f Xci C $xi f x 5 14. f x 6 3x y y 5 sobre la región delimitada por las gráficas de las ecuaciones. 6 5 4 3 2 1 4 1. f SxD x, y 0, x 0, x3 3 63.2 (Sugerencia: Sea ci 3i 2Yn 2.) 2. 3 f SxD x, y 0, x 0, 3 3 (Sugerencia: Sea ci i n .) En los ejercicios 3 a 8, evaluar la integral definida mediante la definición de límite. 15. 6 3 8 dx 3. 2 1 4 x3 dx 5. 1 2 1 7. 4x2 dx 6. 1 x2 1 dx 2x2 3 dx 8. 1 \\ 64. Promedio de ventas Unay compañía ajusta un modelo a los datos y de ventas mensuales de un producto de temporada. El modelo es 8 4 Pt t 3 0 b t b 24 , SSt6D 1.8 0.5 sen 4 6 4 2 donde S son las ventas (en miles) y t es el tiempo en meses. 2 1 x dx 4. 2 Ciclo respiratorio El volumen V en litros de aire en los pulmones durante un ciclo respiratorio de cinco segundos se aproxima x x 2 3 2 1 1 2 3 4 5 mediante 1 2 3 4 el5 modelo V 0.1729t 0.1522t 0.0374t donde t es el tiempo en segundos. Aproximar el volumen medio de aire en los pulmones16. durante un ciclo. f SxD 4 x f SxD x 2 1 x1 2 a) Utilizar una herramienta de graficación para representar ƒ(t) 0.5 sen(PtY6) para 0 b t b 24. Emplear la gráfica para explicar por qué el valor medio de ƒ(t) es cero sobre el intervalo. b) Recurrir a una herramienta de graficación para representar S(t) y la recta g(t) tY4 1.8 en la misma ventana de observación. Utilizar la gráfica y el resultado del apartado a) para explicar por qué g recibe el nombre recta de tendencia. APLICACIONES “¿Cuándo usaré esto?”, los autores tratan de responder esta pregunta de los estudiantes con ejercicios y ejemplos que se seleccionaron con todo cuidado. Las aplicaciones se toman de diversas fuentes: eventos actuales, datos de trabajo, tendencias industriales, y se relacionan con una amplia gama de intereses. Entender dónde se usa (o puede usarse) el cálculo fomenta una comprensión más completa del material. 318 CAPÍTULO 4 4 Ejercicios de repaso 2. y 15. Velocidad y aceleración Se lanza una pelota hacia arriba verticalmente desde el nivel del suelo con una velocidad inicial de 96 pies por segundo. fa a) ¿Cuánto tardará la pelota en alcanzar su altura máxima? ¿Cuál es la altura máxima? ¿Cuándo la velocidad de la pelota es la mitad de la velocidad inicial? c) ¿A qué altura está la pelota cuando su velocidad es la mitad de la velocidad inicial? x x b) En los ejercicios 3 a 8, encontrar la integral indefinida. 5. 7. 4x2 x 3 dx x4 4. 8 dx x3 6. 2x 9 sen x dx 8. 16. 2 3 3x x4 dx 4x2 x2 1 dx 5 cos x 2 sec2 x dx Encontrar la solución particular de la ecuación diferencial ƒa(x) 6x cuya gráfica pasa por el punto (1, 2). 10. Encontrar la solución particular de la ecuación diferencial ƒaa(x) 6(x 1) cuya gráfica pasa por el punto (2, 1) y es tangente a la recta 3x y 5 0 en ese punto. Campos de pendientes En los ejercicios 11 y 12 se da una ecuación diferencial, un punto y un campo de pendientes. a) Dibujar dos soluciones aproximadas de la ecuación diferencial en el campo de pendiente, una de las cuales pase a través del punto indicado. b) Utilizar la integración para encontrar la solución particular de la ecuación diferencial y utilizar una herramienta de graficación para representar la solución. dy 2x 4, dx S4, 2D 1 dy x2 2x, S6, 2D dx 2 12. y −1 t 0 5 10 15 20 25 30 v1 0 2.5 7 16 29 45 65 0 21 38 51 60 65 18. d) 30 40 50 60 21 40 62 78 83 a) Emplear una herramienta de graficación para determinar un modelo de la forma v at3 bt2 ct d para los datos. 3n1 n 1 3n2 n 1 2 SeaFSxD 19. 5 n n 1 2i 20. i 12 22. x 1 f SxD dx f 1 f 13. % 1 a) Utilizar esta fórmula para aproximar el error de la aproximación. cos x dx. Encontrar 1 % 1 b) Utilizar esta fórmula para aproximar 1 sen t 2 dt. Utilizar una herramienta de graficación para completar la tabla. 0 1.0 1.5 1.9 2.0 2.1 2.5 3.0 4.0 5.0 1 dx. 1 x2 c) Probar que la aproximación gaussiana de dos puntos es exacta para todos los polinomios de grado 3 o menor. 2 a) 1 3 7. Arquímedes demostró que el área de un arco parabólico es igual a 2< del producto de la base y la altura (ver la figura). 2 FXxC x h FXxC 4i 1 i1 20 ii 2 1 i1 23. Escribir en notación sigma a) la suma de los primeros diez enteros impares positivos, b) la suma de los cubos de los primeros n enteros positivos y c) 6 10 14 18 · · · 42. 24. Calcular cada suma para x1 2, x2 1, x3 5, x4 3 y 7 % x b) 12 i1 7 La aproximación gaussiana de dos puntos para f es % 20 i1 −2 % x 3 . . . n 6. 1 dt, x > 0. t Encontrar L(1). Encontrar La(x) y La(1). Utilizar una herramienta de graficación para aproximar el valor de x (hasta tres lugares decimales) para el cual L(x) 1. Demostrar que L(x1 x2) L(x1) L(x2) para todos los valores positivos de x1 y x2. x 2. 1 1 1 1 . . . 31 32 33 310 2 % 1 En los ejercicios 17 y 18, utilizar la notación sigma para escribir la suma. 17. Sea SxD a) b) c) Reescribir las velocidades en pies por segundo. Usar las capacidades de regresión de una herramienta de graficación para encontrar los modelos cuadráticos para los datos en el apartado a). c) Aproximar la distancia recorrida por cada carro durante los 30 segundos. Explicar la diferencia en las distancias. 20 6 −1 20 5 Solución de problemas x 1. a) b) 21. −6 64 SP En los ejercicios 19 a 22, utilizar las propiedades de las sumas y el teorema 4.2 para calcular las sumas. y x 10 0 Modelado matemático La tabla muestra las velocidades (en millas por hora) de dos carros sobre una rampa de acceso a una carretera interestatal. El tiempo t está en segundos. v2 9. 11. 0 v Los ejercicios de repaso ubicados al final de cada capítulo proporcionan a los estudiantes más oportunidades para practicar. Estos conjuntos de ejercicios constituyen una revisión completa de los conceptos del capítulo y son un medio excelente para que los estudiantes preparen un examen. una distancia de 264 pies. Encontrar la distancia en la cual el automóvil puede llegar al reposo a partir de una velocidad de 30 millas por hora, suponiendo la misma desaceleración constante. y fa 3. t EJERCICIOS DE REPASO Integración En los ejercicios 1 y 2, utilizar la gráfica de f para dibujar una gráfica de ƒ. 1. 65. Modelado matemático Se prueba un vehículo experimental en una pista recta. Parte del reposo y su velocidad v (metros por segundo) se registra en la tabla cada 10 segundos durante un minuto. 1 1 sen t 2 dt. Utilizar una FSxD x2 x2 2 herramienta de graficacón para completar la tabla y estimar lím GSxD. Sea GSxD xm2 x 1.9 1.95 1.99 2.01 b) 2.1 GXxC c) c) Utilizar la definición de la derivada para encontrar el valor exacto del límite lím GSxD. xm2 SOLUCIÓN DE PROBLEMAS b a) En los ejercicios 3 y 4, a) escribir el área bajo la gráfica de la función dada definida sobre el intervalo indicado como un límite. Después b) calcular la suma del apartado a) y c) calcular el límite tili d l lt d d l t d b) 8. Graficar el arco parabólico delimitado por y 9 x2 y el eje x. Utilizar una integral apropiada para encontrar el área A. Encontrar la base y la altura del arco y verificar la fórmula de Arquímedes. Demostrar la fórmula de Arquímedes para una parábola general. Galileo Galilei (1564-1642) enunció la siguiente proposición relativa a los objetos en caída libre: El tiempo en cualquier espacio que se recorre por un cuerpo acelerado uniformemente es igual al tiempo en el cual ese mismo espacio se recorrería por el mismo cuerpo movién- Estos conjuntos de ejercicios al final de cada capítulo prueban las habilidades de los estudiantes con preguntas desafiantes que retan su pensamiento. 0-Prelim L2.indd xiii 1/12/09 18:04:26 xiv Características Cálculos clásicos con relevancia contemporánea TEOREMAS Los teoremas proporcionan el marco conceptual del cálculo; se enuncian claramente y se distinguen del resto del texto por medio de recuadros para tener una rápida referencia visual. Las demostraciones más importantes muchas veces siguen al teorema, y se proporcionan otras más en un apéndice. TEOREMA 4.9 EL TEOREMA FUNDAMENTAL DEL CÁLCULO Si una función ƒ es continua en el intervalo cerrado [a, b] y F es una antiderivada de ƒ en el intervalo [a, b], entonces % b f SxD dx FSbD FSaD. a DEFINICIONES Al igual que con los teoremas, las definiciones se enuncian claramente utilizando palabras sencillas y precisas; también se separan del texto mediante recuadros para tener una rápida referencia visual. DEFINICIÓN DE LONGITUD DE ARCO Sea la función dada por y f(x) que represente una curva suave en el intervalo [a, b]. La longitud del arco de f entre a y b es % b s 1 F fSxDG 2 dx. a Similarmente, para una curva suave dada por x g(y), la longitud de arco de g entre c y d es % d s 1 F gS yDG 2 dy. c La regla de L’Hôpital también puede aplicarse a los límites unilaterales, como se demuestra en los ejemplos 6 y 7. Forma indeterminada 00 EJEMPLO 6 Encontrar lím sen xx. x0 PROCEDIMIENTOS Solución Porque la sustitución directa produce la forma indeterminada 00, proceder como se muestra abajo. Para empezar, asumir que el límite existe y es igual a y. y lím sen xx Los procedimientos aparecen separados del texto para brindar una referencia fácil. Estas líneas proporcionan a los estudiantes instrucciones paso a paso que les ayudarán a resolver problemas de manera rápida y eficiente. NOTAS Forma indeterminada 00. x0 ln y ln lím sen x x x0 Tomar un logaritmo natural de cada lado. lím lnsen xx Continuidad. lím x lnsen x Forma indeterminada 0 · (@). lnsen x lím x0 1x Forma indeterminada @Y@. cot x lím x0 1x 2 Regla de L’Hôpital. x 2 lím x0 tan x Forma indeterminada 0Y0. 2x lím 0 x0 sec2x Regla de L’Hôpital. x0 x0 Las notas proporcionan detalles adicionales acerca de los Ahora, porque ln y 0, concluir que y e 1, y se sigue que teoremas, definiciones y ejemplos. Ofrecen una profundización adicional o generalizaciones importantes que los estulím sen x 1. diantes podrían omitir involuntariamente. Al igual que las ayudas de estudio, NOTA Al aplicar la fórmula para la longitud de arco a una curva, hay que asegurarse de que la curva se recorra una sola vez en el intervalo de integración. Por ejemplo, el círculo dado por las notas resultan invaluax ⫽ cos t y y ⫽ sen t, recorre una sola vez el intervalo 0 ⱕ t ⱕ 2, pero recorre dos veces el interbles para los estudiantes. valo 0 ⱕ t ⱕ 4. I 0 x x0 0-Prelim L2.indd xiv 1/12/09 18:04:33 xv Características Ampliar la experiencia del cálculo ENTRADAS DE CAPÍTULO Ecuaciones diferenciales 6 Las entradas de capítulo proporcionan motivación inicial para el material que se abordará en el capítulo. Además de los objetivos, en la entrada de cada capítulo un concepto importante se relaciona con una aplicación del mundo real. Esto motiva a los estudiantes a que descubran la relevancia del cálculo en la vida. En este capítulo se estudiará una de las más importantes aplicaciones del cálculo: las ecuaciones diferenciales. El lector aprenderá nuevos métodos para resolver diferentes tipos de ecuaciones diferenciales, como las homogéneas, lineales de primer orden y de Bernoulli. Posteriormente aplicará esas reglas para resolver ecuaciones diferenciales en problemas de aplicación. En este capítulo, se aprenderá: n Cómo generar un campo de pendientes de una ecuación diferencial y encontrar una solución particular. (6.1) n Cómo usar una función exponencial para modelos de crecimiento y decrecimiento. (6.2) n Como usar el método de separación de variables para resolver ecuaciones diferenciales. (6.3) n Cómo resolver ecuaciones diferenciales lineales de primer orden y la ecuación diferencial de Bernoulli. (6.4) EXPLORACIÓN Converso del teorema 4.4 ¿Es verdadero el converso del teorema 4.4 ? Esto es, si una función es integrable, ¿tiene que ser continua? Explicar el razonamiento y proporcionar ejemplos. Describir las relaciones entre continuidad, derivabilidad e integrabilidad. ¿Cuál es la condición más fuerte? ¿Cuál es la más débil? ¿Qué condiciones implican otras condiciones? ■ Dr. Dennis Kunkel/Getty Images ■ Según el tipo de bacteria, el tiempo que le toma duplicar su peso al cultivo puede variar mucho, desde varios minutos hasta varios días. ¿Cómo usaría una ecuación diferencial para modelar la tasa de crecimiento del peso del cultivo de una bacteria? (Vea la sección 6.3, ejercicio 84.) EXPLORACIÓN Suponer que se pide encontrar una de las siguientes integrales. ¿Cuál elegiría? Explicar la respuesta. EXPLORACIONES Las exploraciones proporcionan a los estudiantes retos únicos para estudiar conceptos que no se han cubierto formalmente. Les permiten aprender mediante el descubrimiento e introducen temas relacionados con los que están estudiando en el momento. Al explorar temas de esta manera, se estimula a que los estudiantes piensen de manera más amplia. a) % % % % x3 1 dx o x 2x3 1 dx b) tanS3xD sec 2 S3xD dx Una función y f(x) es una solución de una ecuación diferencial, si la ecuación se satisface cuando y y sus derivadas se remplazan por f(x) y sus derivadas. Una manera de resolver una ecuación diferencial es mediante los campos de pendientes, los cuales muestran la forma de todas las soluciones de una ecuación diferencial. (Ver sección 6.1) o 405 tan S3xD dx NOTAS HISTÓRICAS Y BIOGRAFÍAS Las notas históricas proporcionan a los estudiantes información sobre los fundamentos del cálculo; las biografías les ayudan a sensibilizar y a enseñarles acerca de las personas que contribuyeron a la creación formal del cálculo. DESAFÍOS DEL EXAMEN PUTNAM n n1 o n 1 n donde n 8? 134. Demostrar que si x es positivo, entonces loge 1 1 1 . > x 1x Estos problemas fueron preparados por el Committee on the Putnam Prize Competition. © The Mathematical Association of America. Todos los derechos reservados. Las preguntas del examen Putnam aparecen en algunas secciones y se toman de los exámenes Putnam reales. Estos ejercicios extenderán los límites del entendimiento de los estudiantes en relación con el cálculo y brindarán desafíos adicionales para aquellos más interesados. The Granger Collection Preparación del examen Putnam 133. ¿Cuál es mayor LA SUMA DE LOS PRIMEROS CIEN ENTEROS BLAISE PASCAL (1623-1662) El maestro de Carl Friedrich Gauss (17771855) pidió a sus alumnos que sumaran todos los enteros desde 1 hasta 100. Cuando Gauss regresó con la respuesta correcta muy poco tiempo después, el maestro no pudo evitar mirarle atónito. Lo siguiente fue lo que hizo Gauss: Pascal es bien conocido por sus 1 2 3 . . . 100 contribuciones a diversas áreas de las ... 1 matemáticas y de la física, así como por 100 99 98 . . . 101 su influencia con Leibniz. Aunque buena 101 101 101 100 101 parte de su obra en cálculo fue intuitiva y 5 050 carente del rigor exigible en las matemáticas 2 modernas, Pascal anticipó muchos Esto se generaliza por medio del teorema resultados relevantes. 4.2, donde 100 Oi t 1 100S101D 5 050. 2 PROYECTOS DE SECCIÓN Los proyectos aparecen en algunas secciones y exploran a mayor profundidad las aplicaciones relacionadas con los temas que se están estudiando. Proporcionan una forma interesante y entretenida para que los estudiantes trabajen e investiguen ideas de manera conjunta. PROYECTO DE TRABAJO Demostración del teorema fundamental Utilizar una herramienta de graficación para representar la función y1 sen2t en el intervalo 0 b t b P. Sea F(x) la siguiente función de x. % b) Utilizar las funciones de integración de una herramienta de graficación para representar F. c) Emplear las funciones de derivación de una herramienta de graficación para hacer la gráfica de F (x). ¿Cómo se relaciona esta gráfica con la gráfica de la parte b)? d) Verificar que la derivada de y (1Y2)t (sen 2t)Y4 es sen2t. Graficar y y escribir un pequeño párrafo acerca de cómo esta gráfica se relaciona con las de los apartados b) y c). x FSxD sen 2 t dt 0 a) Completar la tabla. Explicar por qué los valores de ƒ están creciendo. x 0 PY6 PY3 PY2 2PY3 5PY6 P FXxC 0-Prelim L2.indd xv 1/12/09 18:04:35 xvi Características Tecnología integrada para el mundo actual Encontrar INVESTIGACIONES CON SISTEMAS ALGEBRAICOS POR COMPUTADORA Cambio de variables EJEMPLO 5 % x2x 1 dx. Los ejemplos a lo largo del libro se acompañan de investigaciones que emplean un sistema algebraico por computadora (por ejemplo, Maple®) para explorar de manera adicional un ejemplo relacionado en el libro. Permiten a los estudiantes explorar el cálculo manipulando funciones, gráficas, etc., y observar los resultados. Solución Como en el ejemplo previo, considerar que u 2x 1 para obtener dx duY2. Como el integrando contiene un factor de x, se tiene que despejar x en términos de u, como se muestra. x Su 1DY2 u 2x 1 Resolver para x en términos de u. Después de esto, utilizando la sustitución, se obtiene % x2x 1 dx % % u 1 1Y2 du u 2 2 1 Su3Y2 u1Y2D du 4 1 u5Y2 u3Y2 C 3Y2 4 5Y2 1 1 S2x 1D5Y2 S2x 1D3Y2 C. 10 6 Razonamiento gráfico En los ejercicios 55 a 58, a) usar una herramienta de graficación para representar gráficamente la función, b) representar su función inversa utilizando la herramienta de graficación y c) determinar si la gráfica de la relación inversa es una función inversa. Explicar la respuesta. EJERCICIOS CON HERRAMIENTAS DE GRAFICACIÓN La comprensión con frecuencia mejora utilizando una gráfica o visualización. Los ejercicios de tecnología de graficación piden a los estudiantes recurrir a una herramienta de graficación para ayudar a encontrar una solución. CAS Campos de pendientes En los ejercicios 67 a 72, usar un sistema algebraico por computadora para a) trazar la gráfica del campo de pendientes para la ecuación diferencial y b) trazar la gráfica de la solución que satisface la condición inicial especificada. 67. dy 0.25y, dx y0 4 68. dy 4 y, dx y0 6 69. dy 0.02y10 y, dx 70. dy 0.2x2 y, dx y0 9 71. dy 0.4y3 x, dx y0 1 72. y dy 1 x8 sen e , dx 2 4 a CAS 79. % % 1 dx x 2 4x 13 80. 1 dU 1 sen U 82. En los ejercicios 33 a 40, usar un sistema algebraico por computadora para determinar la primitiva que atraviesa el punto dado. Usar el sistema para hacer la gráfica de la antiderivada resultante. 33. 35. f SxD x 3 x 4 5x dx, 6, 0 34. x 2 10x 25 x2 x 2 dx, 0, 1 x 2 22 36. 6x 2 1 dx, 2, 1 x 2x 13 x3 dx, 3, 4 x 2 42 ¡NUEVO! De igual manera que los ejercicios con herramientas de graficación, algunos ejercicios pueden resolverse mejor utilizando un sistema algebraico por computadora. Estos ejercicios son nuevos en esta edición. 0-Prelim L2.indd xvi hSxD x4 x 2 A lo largo del libro, los recuadros de tecnología dan a los estudiantes una visión de cómo la tecnología puede usarse para ayudar a resolver problemas y explorar los conceptos del cálculo. No sólo proporcionan discusiones acerca de dónde la tecnología tiene éxito, sino también sobre dónde puede fracasar. % % x2 dx x 2 4x 13 ex ex 2 3 dx TECNOLOGÍA La regla de Simpson puede usarse para dar una buena aproximación del valor de la integral en el ejemplo 2 (para n 10, la aproximación es 1.839). Al usar la integración numérica, sin embargo, se debe estar consciente de que la regla de Simpson no siempre da buenas aproximaciones cuando algunos de los límites de integración están cercanos a una asíntota vertical. Por ejemplo, usando el teorema fundamental del cálculo, se obtiene % 1.99 EJERCICIOS CON SISTEMAS ALGEBRAICOS POR COMPUTADORA 56. TECNOLOGÍA En los ejercicios 79 a 82, usar un sistema algebraico por computadora para encontrar la integral. Usar el sistema algebraico por computadora para hacer la gráfica de dos antiderivadas. Describir la relación entre las gráficas de las dos antiderivadas. 81. y0 2 y0 2 CAS 55. 0 x3 4 x 2 dx 6.213. Aplicando la regla de Simpson (con n 10) para esta integral se produce una aproximación de 6.889. 1/12/09 18:04:40 1059997_cop10.qxd 9/2/08 10-1.qxd 3/12/09 16:44 3:48 PM Page 695 Page 695 1100 Cónicas, ecuaciones Conics, Parametric paramétricas Equations, and y Polar Coordinates coordenadas polares En este chapter, capítulo you se analizarán y seand write In this will analyze escribirán ecuaciones de cónicas usando equations of conics using their properties. sus propiedades. También se aprenderá You will also learn how to write and graph cómo escribir y graficar ecuaciones parametric equations and polar equations, paramétricas y polares, y cómo se and see how calculus cansebeverá used to study puede usar el cálculo para estudiar tales these graphs. In addition to the rectangular gráficas. de las equationsAdemás of conics, youecuaciones will also study rectangulares de cónicas, polar equations of conics.también se estudiarán ecuaciones polares de cónicas. In this chapter, you should learn the En este capítulo, se aprenderá: following. n Cómo analizar y escribir ecuaciones I How to analyze and write equations of de una parábola, una elipse y una a parabola, an ellipse, and a hyperbola. hipérbola. (10.1) (10.1) n Cómo trazar una curva representada I How to sketch a curve represented by por ecuaciones paramétricas. (10.2) I parametric equations. (10.2) n Cómo usar un conjunto de ecuacioI How to use a set of parametric equations nes paramétricas para encontrar la to find the slope of a tangent line to a pendiente de una línea tangente a curve and the arc length of a curve. una curva y la longitud de arco (10.3) de una curva. (10.3) I How to sketch the graph of an equation n Cómo dibujar la gráfica de una ecuain polar form, find the slope of a tangent ción en forma polar, encontrar la line to a polar graph, and identify special pendiente de una línea tangente a polar graphs. (10.4) una gráfica polar e identificar gráfiI How to find the area of a region cas polares especiales. (10.4) bounded by a polar graph and find the n Cómo encontrar el área de una arc length of a polar graph. (10.5) región acotada por una gráfica polar I How to analyze and write a polar y encontrar la longitud de arco de equation of apolar. conic.(10.5 (10.6 una gráfica )) n Cómo analizar y escribir una ecuación polar de una cónica. (10.6) © Chuck Savage/Corbis Thepuede path ofmodelar a baseball hit at a particular height de at an anglebateada with theahorizontal Se la trayectoria de una pelota béisbol una alturacan be modeled using parametric equations. How can a set of parametric equations¿Cómo be específica a un ángulo con el horizontal utilizando ecuaciones paramétricas. I used to find the minimum angle at which the ball must leave the bat in order for se puede usar un conjunto de ecuaciones paramétricas para encontrar el ángulothe hit to beala cual homelarun? (See Section Exercise 75.)el golpe sea un jonrón? (Ver mínimo pelota debe salir 10.2, del bate para que la sección 10.2, ejercicio 75.) En de coordenadas polares, graficar una ecuación unaabout curvaa alrededor decalled un punto fijo In el thesistema polar coordinate system, graphing an equation involvesimplica tracingtrazar a curve fixed point the pole. llamado el polo. Considerar una región acotada por una curva y por los rayos que contienen los puntos extremos Consider a region bounded by a curve and by the rays that contain the endpoints of an interval on the curve. Youde un sobreoflacircles curva.toPueden usarsethe sectores para aproximar área de región. En la canintervalo use sectors approximate area ofcirculares such a region. In Sectionel10.5, youtalwill see how thesección limit 10.5 se verá cómo es posible usar el proceso de límite para encontrar esta área. process can be used to find this area. 695 695 10-1.qxd 3/12/09 696 16:44 Page 696 CAPÍTULO 10 Cónicas, ecuaciones paramétricas y coordenadas polares 10.1 Cónicas y cálculo n n n n Entender la definición de una sección cónica. Analizar y dar las ecuaciones de la parábola utilizando las propiedades de la parábola. Analizar y dar las ecuaciones de la elipse utilizando las propiedades de la elipse. Analizar y dar las ecuaciones de la hipérbola utilizando las propiedades de la hipérbola. Secciones cónicas Bettmann/Corbis Toda sección cónica (o simplemente cónica) puede describirse como la intersección de un plano y un cono de dos hojas. En la figura 10.1 se observa que en las cuatro cónicas básicas el plano de intersección no pasa por el vértice del cono. Cuando el plano pasa por el vértice, la figura que resulta es una cónica degenerada, como se muestra en la figura 10.2. HYPATIA (370-415 D.C.) Los griegos descubrieron las secciones cónicas entre los años 600 y 300 a.C. A principios del periodo alejandrino ya se sabía lo suficiente acerca de las cónicas como para que Apolonio (269-190 a.C.) escribiera una obra de ocho volúmenes sobre el tema. Más tarde, hacia finales del periodo Alejandrino, Hypatia escribió un texto titulado Sobre las cónicas de Apolonio. Su muerte marcó el final de los grandes descubrimientos matemáticos en Europa por varios siglos. Los primeros griegos se interesaron mucho por las propiedades geométricas de las cónicas. No fue sino 1900 años después, a principios del siglo XVII, cuando se hicieron evidentes las amplias posibilidades de aplicación de las cónicas, las cuales llegaron a jugar un papel prominente en el desarrollo del cálculo. Circunferencia Secciones cónicas Parábola Figura 10.1 Punto Cónicas degeneradas Recta Dos rectas que se cortan Figura 10.2 Existen varias formas de estudiar las cónicas. Se puede empezar, como lo hicieron los griegos, definiendo las cónicas en términos de la intersección de planos y conos, o se pueden definir algebraicamente en términos de la ecuación general de segundo grado Ax2 + Bxy + Cy2 + Dx + Ey + F = 0. PARA MAYOR INFORMACIÓN Para conocer más sobre las actividades de esta matemática, consultar al artículo “Hypatia and her Mathematics” de Michael A. B. Deakin en The American Mathematical Monthly. Hipérbola Elipse Ecuación general de segundo grado. Sin embargo, un tercer método en el que cada una de las cónicas está definida como el lugar geométrico (o colección) de todos los puntos que satisfacen cierta propiedad geométrica, funciona mejor. Por ejemplo, la circunferencia se define como el conjunto de todos los puntos (x, y) que son equidistantes de un punto fijo (h, k). Esta definición en términos del lugar geométrico conduce fácilmente a la ecuación estándar o canónica de la circunferencia (x - h)2 +(y - k)2 = r2. Ecuación estándar o canónica de la circunferencia. Para información acerca de la rotación de ecuaciones de segundo grado en dos variables, ver el apéndice D. 1059997_1001.qxp 9/2/08 10-1.qxd 3/12/09 1059997_1001.qxp 3:49 PM Page 697 16:44 Page 697 9/2/08 3:49 PM Page 697 10.1 Conics Calculus SECCIÓN 10.1 and Cónicas y cálculo 697 697 10.1 Conics and Calculus 697 Parabolas Parábolas A x x, ylosthat AUna parabola is the setconjunto of all points are equidistant from a fixed linerecta called parábola es el de todos puntos (x, y) equidistantes de una fija llaParabolas the directrix and a fixed point called the focus not on the line. The midpoint between mada directriz y de un punto fijo, fuera de dicha recta, llamado foco. El punto medio entre the focus the directrix the line passing the A parabola is theesset allvertex, points x, ythe that are equidistant afocus fixedand lineel called el foco yand la directriz elisof vértice, y la and recta que pasa por elthrough focofrom ythe el vértice es eje de vertex is the axis of the parabola. Note in Figure 10.3 that a parabola is symmetric the directrix and a fixed point called the focus not on the line. The midpoint between la parábola. Obsérvese en la figura 10.3 que la parábola es simétrica respecto de su eje. with the respect its the axis.directrix is the vertex, and the line passing through the focus and the focustoand vertex is the axis of the parabola. Note in Figure 10.3 that a parabola is symmetric TEOREMA 10.1 toECUACIÓN with respect its axis. ESTÁNDAR O CANÓNICA DE UNA PARÁBOLA THEOREM 10.1 STANDARD EQUATION OF A PARABOLA La forma estándar o canónica de la ecuación de una parábola con vértice The form the of a parabola with vertex h, k and (h, k)standard y directriz es EQUATION y 5ofkSTANDARD 2 pequation THEOREM 10.1 OF A PARABOLA directrix y 2 k p is vertical. sThe x 2standard hd 5 4psform y 2 kof d. the equation of a Eje parabola with vertex h, k and x h 2 4p y k . Vertical axis directrix y k p is Para la directriz x 5 h 2 p, la ecuación es For directrix2x 2 h p, the equation is h 4psx4p Vertical axis Eje horizontal. s y 2 xkd 5 2 yhd. k . y k 2 4p x h . Horizontal axis Forse directrix x enh el eje p, the El foco encuentra a p equation unidadesis(distancia dirigida) del vértice. Las The focus lies on the axis p units (directed distance) from the vertex. The coordenadas sonx las hsiguientes. 2 y delk foco 4p . Horizontal axis coordinates of the focus are as follows. Eje vertical. sThe h, k focus 1 pd lies on the axis p units (directed distance) from the vertex. The h, k p, pkd Vertical axis scoordinates h1 of the focus are as follows. Eje horizontal. h p, k Horizontal axis h, k p Vertical axis h p, k Horizontal axis Eje Pa r a b Parábola o la A x Pa r a b o F l a o c u s Foco d2 d2 (x, y)(x, y) pd1 d 1 d d F o c u s 2 d2 V e r t e Vértice x (x, y) d1 d 2 1 p d1 d2 Di r e c Directriz trix V e rte x d1 p Figure 10.3 10.3 Figura Di r e c t r i x Figure 10.3 EXAMPLE Finding Focus of a parábola Parabola EJEMPLO 1 1 Hallar el the foco de una y y= 1 2 − x − 12 x 2 y V ér t i c e y = 12 − x − 12 x 2 1 )V −ér1,t i 12c )e p = − 12 1 Foco p = − 12 −2 −1 )− 1, 12 ) x Foco x −2 −1 −1 −1 Parabola with a vertical axis, p < 0 Figure 10.4 Parábola p < p0 < 0 Parabolacon withejea vertical, vertical axis, Figura Figure10.4 10.4 1 1 2 EXAMPLE Findingdada thepor Focus Find theelfocus parabola given by y of a Parabola x x. Hallar foco of de the la1 parábola 2 2 1 1 2 Solución el parabola foco, se convierte canónica completando el Find the focus of the given by ay la forma x . o estándar Solution ToPara findhallar the focus, convert to standard form xby completing the square. 2 2 cuadrado. 1 1 2 y 2 x 2x Write original equation. Solution To find the focus, convert to standard form by completing the square. 1 2x 2 yy 5121 12 1x 2x Factor out 12.la ecuación original. Reescribir 2 x 1 y2 x2 x2 Write original equation. 2y 11 212x x 2 22 Multiply each side by 2. 1 SacarFactor wQ como y 5y2 s1 212x 22xx d x 2 outfactor. . 2y 1 2 x 2 2x Group terms. 2 2 2 Multiplicar cada lado por 2y 5 2y1 212x2 2 2xx x Multiply each side by2.2. 2y 2 x 2x 1 Add and subtract 1 on right side. 2 2y 21sx 2 1x 2xd 2x Group terms. Agrupar términos. x 2 2x 2y 1 5 1 2y 2 2 2y 2 2 x 2x 1 Add and subtract 1 on right side. 2 5 Sumarinystandard restar 1 form. en el lado derecho. 2 22ysx 11 2x 1 1d x 1 2y Write x 2 2x 1 2y 2 x 2 1 2x 1equation 1 5 22ywith 1 2 x h 2 4 p y k , you can conclude that Comparing this x 12 2 y 1 Write in standard form. sx1,1 1d 2 k5 22 1d h 1, s y 2and p 2 12. Expresar en la forma estándar o canónica. Comparing this equation with x h 4 p y k , you can conclude that Because p is negative, the parabola opens 2downward, as shown in Figure 10.4. So, the Si se compara esta x 2 hd p5 4ps y1. 2 kd, se concluye que h 1, ecuación k 1, con sand focus of the parabola is p units from the vertex, or2 k 5 11 theyparabola h 5 21,p is negative, p 5opens 2 12. downward, as shown in Figure 10.4. So, the Because h, k p 1, 2 . Focus focus of the parabola is p units from the vertex, or Como p es negativo, la parábola se abre hacia abajo, como se muestra en la figura 10.4. Por tanto,h,elk focop de la parábola del vértice, o sea 1, 12 . se encuentra a p unidades Focus A line segment that passes through the focus of a parabola and has endpoints on 1 sh, k 1 is pdcalled 5 s21, the parabola a focal focal chord perpendicular to the axis 2 d. chord. The specificFoco. of the parabola is the latus The next how to the on A line segment thatrectum. passes through theexample focus ofshows a parabola anddetermine has endpoints length the latusisrectum thechord. length The of the corresponding intercepted arc. to the axis theofparabola called aand focal specific focal chord perpendicular of the parabola is the latus rectum. The next example shows how to determine the A un segmento de la recta que pasa por el foco de una parábola y que tiene sus extrelength of the latus rectum and the length of the corresponding intercepted arc. mos en la parábola se le llama cuerda focal. La cuerda focal perpendicular al eje de la parábola es el lado recto (latus rectum). El ejemplo siguiente muestra cómo determinar la longitud del lado recto y la longitud del correspondiente arco cortado. 10-1.qxd 3/12/09 698 16:44 Page 698 CAPÍTULO 10 Cónicas, ecuaciones paramétricas y coordenadas polares Longitud de la cuerda focal y longitud de arco EJEMPLO 2 Encontrar la longitud del lado recto de la parábola dada por x 2 5 4py. Después, hallar la longitud del arco parabólico cortado por el lado recto. y Solución Debido a que el lado recto pasa por el foco (0, p) y es perpendicular al eje y, las coordenadas de sus extremos son s2x, pd y sx, pd. Al sustituir, en la ecuación de la parábola, y por p se obtiene x2 = 4py x 5 ± 2p. x 2 5 4ps pd Lado recto o latus rectum (−2p, p) Entonces, los extremos del lado recto son s22p, pd y s2p, pd, y se concluye que su longitud es 4p, como se muestra en la figura 10.5. En cambio, la longitud del arco cortado es (2p, p) x (0, p) E E! E 2p Longitud del lado recto o latus rectum: 4p s5 Figura 10.5 22p Emplear la fórmula de longitud del arco. !1 1 s y9 d2 dx 2p 52 11 0 12px 2 2 y5 dx x2 4p y9 5 x 2p 2p 5 5 5 5 < Fuente de luz en el foco 1 !4p 2 1 x 2 dx p 0 2p 1 x!4p 2 1 x 2 1 4p 2 ln x 1 !4p 2 1 x 2 2p 0 1 f2p!8p 2 1 4p 2 lns2p 1 !8p 2 d 2 4p 2 lns2pdg 2p 2p f!2 1 ln s1 1 !2 dg 4.59p. 3 | |4 Simplificar. Teorema 8.2. Una propiedad muy utilizada de la parábola es su propiedad de reflexión. En física, se dice que una superficie es reflejante o reflectante si la tangente a cualquier punto de la superficie produce ángulos iguales con un rayo incidente y con el rayo reflejado resultante. El ángulo correspondiente al rayo incidente es el ángulo de incidencia, y el ángulo correspondiente al rayo que se refleja es el ángulo de reflexión. Un espejo plano es un ejemplo de una superficie reflejante o reflectante. Otro tipo de superficie reflejante es la que se forma por revolución de una parábola alrededor de su eje. Una propiedad especial de los reflectores parabólicos es que permiten dirigir hacia el foco de la parábola todos los rayos incidentes paralelos al eje. Éste es el principio detrás del diseño de todos los espejos parabólicos que se utilizan en los telescopios de reflexión. Inversamente, todos los rayos de luz que emanan del foco de una linterna con reflector parabólico son paralelos, como se ilustra en la figura 10.6. Eje TEOREMA 10.2 PROPIEDAD DE REFLEXIÓN DE UNA PARÁBOLA Sea P un punto de una parábola. La tangente a la parábola en el punto P produce ángulos iguales con las dos rectas siguientes. Reflector parabólico: la luz se refleja en rayos paralelos Figura 10.6 1. La recta que pasa por P y por el foco 2. La recta paralela al eje de la parábola que pasa por P 10-1.qxd 3/12/09 16:44 Page 699 SECCIÓN 10.1 699 Cónicas y cálculo Bettmann/Corbis Elipses NICOLÁS COPÉRNICO (1473-1543) Copérnico comenzó el estudio del movimiento planetario cuando se le pidió que corrigiera el calendario. En aquella época, el uso de la teoría de que la Tierra era el centro del Universo, no permitía predecir con exactitud la longitud de un año. Más de mil años después de terminar el periodo alejandrino de la matemática griega, comienza un renacimiento de la matemática y del descubrimiento científico en la civilización occidental. Nicolás Copérnico, astrónomo polaco, fue figura principal en este renacimiento. En su trabajo Sobre las revoluciones de las esferas celestes, Copérnico sostenía que todos los planetas, incluyendo la Tierra, giraban, en órbitas circulares, alrededor del Sol. Aun cuando algunas de las afirmaciones de Copérnico no eran válidas, la controversia desatada por su teoría heliocéntrica motivó a que los astrónomos buscaran un modelo matemático para explicar los movimientos del Sol y de los planetas que podían observar. El primero en encontrar un modelo correcto fue el astrónomo alemán Johannes Kepler (1571-1630). Kepler descubrió que los planetas se mueven alrededor del Sol, en órbitas elípticas, teniendo al Sol, no como centro, sino como uno de los puntos focales de la órbita. El uso de las elipses para explicar los movimientos de los planetas es sólo una de sus aplicaciones prácticas y estéticas. Como con la parábola, el estudio de este segundo tipo de cónica empieza definiéndola como lugar geométrico de puntos. Sin embargo, ahora se tienen dos puntos focales en lugar de uno. Una elipse es el conjunto de todos los puntos (x, y), cuya suma de distancias a dos puntos fijos llamados focos es constante. (Ver la figura 10.7.) La recta que une a los focos interseca o corta a la elipse en dos puntos, llamados vértices. La cuerda que une a los vértices es el eje mayor, y su punto medio es el centro de la elipse. La cuerda a través del centro, perpendicular al eje mayor, es el eje menor de la elipse. (Ver la figura 10.8.) (x, y) d1 d2 Vértice Foco Eje mayor (h, k) Foco Centro Vértice Foco Foco Eje menor Figura 10.7 Figura 10.8 PARA MAYOR INFORMACIÓN Para saber más acerca de cómo “hacer explotar” una elipse para convertirla en una parábola, consultar al artículo “Exploding the Ellipse” de Arnold Good en Mathematics Teacher. TEOREMA 10.3 ECUACIÓN ESTÁNDAR O CANÓNICA DE UNA ELIPSE La forma estándar o canónica de la ecuación de una elipse con centro (h, k) y longitudes de los ejes mayor y menor 2a y 2b, respectivamente, donde a > b, es sx 2 hd 2 s y 2 kd2 1 51 a2 b2 El eje mayor es horizontal. sx 2 hd 2 s y 2 kd2 1 5 1. b2 a2 El eje mayor es vertical. o Si los extremos de una cuerda se atan a los alfileres y se tensa la cuerda con un lápiz, la trayectoria trazada con el lápiz será una elipse Figura 10.9 Los focos se encuentran en el eje mayor, a c unidades del centro, con c 2 5 a 2 2 b 2. La definición de una elipse se puede visualizar si se imaginan dos alfileres colocados en los focos, como se muestra en la figura 10.9. 10-1.qxd 3/12/09 700 16:44 Page 700 CAPÍTULO 10 Cónicas, ecuaciones paramétricas y coordenadas polares EJEMPLO 3 Completar cuadrados Encontrar el centro, los vértices y los focos de la elipse dada por 4x 2 1 y 2 2 8x 1 4y 2 8 5 0. Solución Al completar el cuadrado se puede expresar la ecuación original en la forma estándar o canónica. (x − 1)2 (y + 2)2 + =1 16 4 4x 2 1 y 2 2 8x 1 4y 2 8 5 0 y 2 4x 2 Vértice 2 1 4y 5 8 4sx 2 1d2 1 s y 1 2d 2 5 16 x −2 Escribir la ecuación original. 4sx 2 2 2x 1 1d 1 s y 2 1 4y 1 4d 5 8 1 4 1 4 Foco −4 2 8x 1 y2 sx 2 1d2 s y 1 2d2 1 51 4 16 4 Centro Escribir la forma estándar o canónica. Así, el eje mayor es paralelo al eje y, donde h 5 1, k 5 22, a 5 4, b 5 2 y c 5 !16 2 4 5 2!3. Por tanto, se obtiene: Foco Centro: −6 s1, 22d sh, kd. sh, k ± ad. Vértices: s1, 26d y s1, 2d Vértice Elipse con eje mayor vertical Focos: Figura 10.10 s1, 22 2 2!3 d y s1, 22 1 2!3 d sh, k ± cd. La gráfica de la elipse se muestra en la figura 10.10. NOTA Si en la ecuación del ejemplo 3, el término constante F 5 28 hubiese sido mayor o igual a 8, se hubiera obtenido alguno de los siguientes casos degenerados. 1. F 5 8, un solo punto, s1, 22d: sx 2 1d 2 s y 1 2d 2 1 50 4 16 2. F > 8, no existen puntos solución: EJEMPLO 4 sx 2 1d 2 s y 1 2d 2 1 < 0 4 16 n La órbita de la Luna La Luna gira alrededor de la Tierra siguiendo una trayectoria elíptica en la que el centro de la Tierra está en uno de los focos, como se ilustra en la figura 10.11. Las longitudes de los ejes mayor y menor de la órbita son 768 800 kilómetros y 767 640 kilómetros, respectivamente. Encontrar las distancias mayor y menor (apogeo y perigeo) entre el centro de la Tierra y el centro de la Luna. Luna Solución Para comenzar se encuentran a y b. 800 2a 5 768 768,800 Tierra a 5 384,400 384 400 640 2b 5 767 767,640 383 820 b 5 383,820 Perigeo Apogeo Longitud del eje mayor. Despejar a. Longitud del eje menor. Despejar b. Ahora, al emplear estos valores, se despeja c como sigue. 108 c 5 !a 2 2 b 2 < 21 21,108 Figura 10.11 La distancia mayor entre el centro de la Tierra y el centro de la Luna es a 1 c < 405,508 363,292 292 kilómetros. 405 508 kilómetros y la distancia menor es a 2 c < 363 10-1.qxd 3/12/09 16:44 Page 701 SECCIÓN 10.1 PARA MAYOR INFORMACIÓN Para más información acerca de algunos usos de las propiedades de reflexión de las cónicas, consultar el artículo “Parabolic Mirrors, Elliptic and Hyperbolic Lenses” de Mohsen Maesumi en The American Mathematical Monthly. Consultar también el artículo “The Geometry of Microwave Antennas” de William R. Paezynski en Mathematics Teacher. Cónicas y cálculo 701 En el teorema 10.2 se presentó la propiedad de reflexión de la parábola. La elipse tiene una propiedad semejante. En el ejercicio 112 se pide demostrar el siguiente teorema. TEOREMA 10.4 PROPIEDAD DE REFLEXIÓN DE LA ELIPSE Sea P un punto de una elipse. La recta tangente a la elipse en el punto P forma ángulos iguales con las rectas que pasan por P y por los focos. Uno de los motivos por el cual los astrónomos tuvieron dificultad para descubrir que las órbitas de los planetas son elípticas es el hecho de que los focos de las órbitas planetarias están relativamente cerca del centro del Sol, lo que hace a las órbitas ser casi circulares. Para medir el achatamiento de una elipse, se puede usar el concepto de excentricidad. DEFINICIÓN DE LA EXCENTRICIDAD DE UNA ELIPSE La excentricidad e de una elipse está dada por el cociente c e5 . a Para ver cómo se usa este cociente en la descripción de la forma de una elipse, obsérvese que como los focos de una elipse se localizan a lo largo del eje mayor entre los vértices y el centro, se tiene que 0 < c < a. En una elipse casi circular, los focos se encuentran cerca del centro y el cociente c/a es pequeño, mientras que en una elipse alargada, los focos se encuentran cerca de los vértices y el cociente c/a está cerca de 1, como se ilustra en la figura 10.12. Obsérvese que para toda elipse 0 < e < 1. La excentricidad de la órbita de la Luna es e 5 0.0549, y las excentricidades de las nueve órbitas planetarias son las siguientes. Focos Mercurio: e 5 0.2056 a c a) Júpiter: e 5 0.0484 Venus: e 5 0.0068 Saturno: e 5 0.0542 Tierra: e 5 0.0167 Urano: e 5 0.0472 Marte: e 5 0.0934 Neptuno: e 5 0.0086 Por integración se puede mostrar que el área de una elipse es A 5 pab. Por ejemplo, el área de la elipse c es pequeño a x2 y2 1 251 2 a b Focos está dada por a E E a A54 0 c 5 b) c es casi 1 a c Excentricidad es el cociente . a Figura 10.12 4b a b !a 2 2 x 2 dx a py2 a 2 cos 2 u du. Sustitución trigonométrica x 5 a sen q . 0 Sin embargo, encontrar el perímetro de una elipse no es fácil. El siguiente ejemplo muestra cómo usar la excentricidad para establecer una “integral elíptica” para el perímetro de una elipse. 10-1.qxd 3/12/09 702 16:44 Page 702 CAPÍTULO 10 Cónicas, ecuaciones paramétricas y coordenadas polares Encontrar el perímetro de una elipse EJEMPLO 5 Mostrar que el perímetro de una elipse sx 2ya 2d 1 s y 2yb 2d 5 1 es E py2 !1 2 e 2 sen sin 2 u du. 4a e5 0 c a Solución Como la elipse dada es simétrica respecto al eje x y al eje y, se sabe que su perímetro C es el cuádruplo de la longitud de arco de y 5 sbyad!a 2 2 x 2 en el primer cuadrante. La función y es diferenciable (o derivable) para toda x en el intervalo f0, ag excepto en x 5 a. Entonces, el perímetro está dado por la integral impropia E E d d→a a !1 1 s y9 d 2 dx 5 4 C 5 lim lím 4 0 E! a !1 1 s y9 d 2 dx 5 4 0 11 0 b 2x 2 dx. sa 2 2 x 2d a2 Al usar la sustitución trigonométrica x 5 a sen sin u, se obtiene C54 E E E E py2 sin sen u sa cos ud du !1 1 ab cos u 0 py2 54 2 22 2 2 !a 2 cos 2 u 1 b 2 sen sin 22 u du 0 py2 54 !a 2s1 2 sen sin 22 ud 1 b 2 sen sin 22 u du 0 py2 54 ÁREA Y PERÍMETRO DE UNA ELIPSE !a 2 2 sa2 2 b 2dsen sin 22 u du. 0 En su trabajo con órbitas elípticas, a principios del siglo XVII, Johannes Kepler desarrolló una fórmula para encontrar el área de una elipse, A 5 pab. Sin embargo, tuvo menos éxito en hallar una fórmula para el perímetro de una elipse, para el cual sólo dio la siguiente fórmula de aproximación C 5 p sa 1 bd. Debido a que e 2 5 c 2ya 2 5 sa 2 2 b 2dya 2, se puede escribir esta integral como E py2 C 5 4a !1 2 e 2 sen sin 22 u du. 0 Se ha dedicado mucho tiempo al estudio de las integrales elípticas. En general dichas integrales no tienen antiderivadas o primitivas elementales. Para encontrar el perímetro de una elipse, por lo general hay que recurrir a una técnica de aproximación. EJEMPLO 6 Aproximar el valor de una integral elíptica Emplear la integral elíptica del ejemplo 5 para aproximar el perímetro de la elipse x2 y2 1 5 1. 25 16 y 6 x2 y2 + =1 25 16 Solución Como e 2 5 c 2ya 2 5 sa 2 2 b 2dya 2 5 9y25, se tiene E C 5 s4ds5d 2 0 x −6 −4 2 −2 py2 4 6 −2 22 Aplicando la regla de Simpson con n 5 4 se obtiene C < 20 C ≈ 28.36 unidades sin u du. !1 2 9 sen 25 1p6 21142f1 1 4s0.9733d 1 2s0.9055d 1 4s0.8323d 1 0.8g < 28.36. −6 Figura 10.13 Por tanto, el perímetro de la elipse es aproximadamente 28.36 unidades, como se muestra en la figura 10.13. 10-1.qxd 3/12/09 16:44 Page 703 SECCIÓN 10.1 Cónicas y cálculo 703 Hipérbolas (x, y) d2 d1 Foco Foco d2 − d1 es constante d2 − d1 = 2a c La definición de hipérbola es similar a la de la elipse. En la elipse, la suma de las distancias de un punto de la elipse a los focos es fija, mientras que en la hipérbola, el valor absoluto de la diferencia entre estas distancias es fijo. Una hipérbola es el conjunto de todos los puntos (x, y) para los que el valor absoluto de la diferencia entre las distancias a dos puntos fijos llamados focos es constante. (Ver la figura 10.14.) La recta que pasa por los dos focos corta a la hipérbola en dos puntos llamados vértices. El segmento de recta que une a los vértices es el eje transversal, y el punto medio del eje transversal es el centro de la hipérbola. Un rasgo distintivo de la hipérbola es que su gráfica tiene dos ramas separadas. a Vértice Centro Vértice TEOREMA 10.5 ECUACIÓN ESTÁNDAR O CANÓNICA DE UNA HIPÉRBOLA La forma estándar o canónica de la ecuación de una hipérbola con centro sh, kd es Eje transversal Figura 10.14 sx 2 hd2 s y 2 kd2 2 51 a2 b2 El eje transversal es horizontal. s y 2 kd2 sx 2 hd2 2 5 1. a2 b2 El eje transversal es vertical. o Los vértices se encuentran a a unidades del centro y los focos se encuentran a c unidades del centro, con c2 5 a 2 1 b2. NOTA En la hipérbola no existe la misma relación entre las constantes a, b y c, que en la elipse. En la hipérbola, c2 5 a 2 1 b2, mientras que en la elipse, c2 5 a 2 2 b2. n Una ayuda importante para trazar la gráfica de una hipérbola es determinar sus asíntotas, como se ilustra en la figura 10.15. Toda hipérbola tiene dos asíntotas que se cortan en el centro de la hipérbola. Las asíntotas pasan por los vértices de un rectángulo de dimensiones 2a por 2b, con centro en (h, k). Al segmento de la recta de longitud 2b que une sh, k 1 bd y sh, k 2 bd se le conoce como eje conjugado de la hipérbola. TEOREMA 10.6 ASÍNTOTAS DE UNA HIPÉRBOLA Si el eje transversal es horizontal, las ecuaciones de las asíntotas son b y 5 k 1 sx 2 hd a Asíntota Eje conjugado (h, k + b) (h − a, k) (h, k) a b y 5 k 2 sx 2 hd. a Si el eje transversal es vertical, las ecuaciones de las asíntotas son a y 5 k 1 sx 2 hd b b y y a y 5 k 2 sx 2 hd. b (h + a, k) (h, k − b) Asíntota Figura 10.15 En la figura 10.15 se puede ver que las asíntotas coinciden con las diagonales del rectángulo de dimensiones 2a y 2b, centrado en (h, k). Esto proporciona una manera rápida de trazar las asíntotas, las que a su vez ayudan a trazar la hipérbola. 10-1.qxd 3/12/09 704 16:44 Page 704 CAPÍTULO 10 Cónicas, ecuaciones paramétricas y coordenadas polares Uso de las asíntotas para trazar una hipérbola EJEMPLO 7 Trazar la gráfica de la hipérbola cuya ecuación es 4x 2 2 y 2 5 16. TECNOLOGÍA Para verificar la gráfica obtenida en el ejemplo 7 se puede emplear una herramienta de graficación y despejar y de la ecuación original para representar gráficamente las ecuaciones siguientes. y1 5 !4x 2 2 16 y2 5 2 !4x 2 2 16 Solución Para empezar se escribe la ecuación en la forma estándar o canónica. x2 y2 2 51 4 16 El eje transversal es horizontal y los vértices se encuentran en s22, 0d y s2, 0d. Los extremos del eje conjugado se encuentran en s0, 24d y s0, 4d. Con estos cuatro puntos, se puede trazar el rectángulo que se muestra en la figura 10.16a. Al dibujar las asíntotas a través de las esquinas de este rectángulo, el trazo se termina como se muestra en la figura 10.16b. y y 6 6 (0, 4) 4 (−2, 0) x2 y2 − =1 4 16 (2, 0) x x −6 4 −4 −6 6 4 −4 6 −4 (0, −4) −6 −6 a) b) Figura 10.16 DEFINICIÓN DE LA EXCENTRICIDAD DE UNA HIPÉRBOLA La excentricidad e de una hipérbola es dada por el cociente c e5 . a Como en la elipse, la excentricidad de una hipérbola es e 5 cya. Dado que en la hipérbola c > a resulta que e > 1. Si la excentricidad es grande, las ramas de la hipérbola son casi planas. Si la excentricidad es cercana a 1, las ramas de la hipérbola son más puntiagudas, como se muestra en la figura 10.17. y y La excentricidad es grande La excentricidad se acerca a 1 Vértice Foco Vértice Foco e = ac c Foco Foco Vértice Vértice x x e = ac a c a Figura 10.17 10-1.qxd 3/12/09 16:44 Page 705 SECCIÓN 10.1 Cónicas y cálculo 705 La aplicación siguiente fue desarrollada durante la Segunda Guerra Mundial. Muestra cómo los radares y otros sistemas de detección pueden usar las propiedades de la hipérbola. EJEMPLO 8 Dos micrófonos, a una milla de distancia entre sí, registran una explosión. El micrófono A recibe el sonido 2 segundos antes que el micrófono B. ¿Dónde fue la explosión? y Solución Suponiendo que el sonido viaja a 1 100 pies por segundo, se sabe que la explosión tuvo lugar 2 200 pies más lejos de B que de A, como se observa en la figura 10.18. El lugar geométrico de todos los puntos que se encuentran 2 200 pies más cercanos a A que a B es una rama de la hipérbola sx 2ya 2d 2 s y 2yb 2d 5 1, donde 4 000 3 000 2 000 d2 B d1 A −2 000 Un sistema hiperbólico de detección 2 000 3 000 −1 000 −2 000 280 2c 5 55280 200 d2 2 d1 5 2a 5 22200 Figura 10.18 c= 1 milla 5 280 pies = = 2 640 pies. 2 2 a= 2 200 pies = 1100 pies 2 x y Como c2 5 a 2 1 b2, se tiene que b2 5 c2 2 a2 5 5 759 600 y se puede concluir que la explosión ocurrió en algún lugar sobre la rama derecha de la hipérbola dada por Mary Evans Picture Library x2 y2 2 5 1. 11,210,000 210 000 55,759,600 759 600 CAROLINE HERSCHEL (1750-1848) La primera mujer a la que se atribuyó haber detectado un nuevo cometa fue la astrónoma inglesa Caroline Herschel. Durante su vida, Caroline Herschel descubrió ocho cometas. En el ejemplo 8, sólo se pudo determinar la hipérbola en la que ocurrió la explosión, pero no la localización exacta de la explosión. Sin embargo, si se hubiera recibido el sonido también en una tercera posición C, entonces se habrían determinado otras dos hipérbolas. La localización exacta de la explosión sería el punto en el que se cortan estas tres hipérbolas. Otra aplicación interesante de las cónicas está relacionada con las órbitas de los cometas en nuestro sistema solar. De los 610 cometas identificados antes de 1970, 245 tienen órbitas elípticas, 295 tienen órbitas parabólicas y 70 tienen órbitas hiperbólicas. El centro del Sol es un foco de cada órbita, y cada órbita tiene un vértice en el punto en el que el cometa se encuentra más cerca del Sol. Sin lugar a dudas, aún no se identifican muchos cometas con órbitas parabólicas e hiperbólicas, ya que dichos cometas pasan una sola vez por nuestro sistema solar. Sólo los cometas con órbitas elípticas como la del cometa Halley permanecen en nuestro sistema solar. El tipo de órbita de un cometa puede determinarse de la forma siguiente. 1. Elipse: 2. Parábola: 3. Hipérbola: v < !2GMyp v 5 !2GMyp v > !2GMyp En estas tres fórmulas, p es la distancia entre un vértice y un foco de la órbita del cometa (en metros), v es la velocidad del cometa en el vértice (en metros por segundo), M < 1.989 3 1030 kilogramos es la masa del Sol y G < 6.67 3 1028 metros cúbicos por kilogramo por segundo cuadrado es la constante de gravedad. 1059997_1001.qxp 9/2/08 3:49 PM Page 706 1059997_1001.qxp 9/2/08 3:49 PM Page 706 1059997_1001.qxp 1059997_1001.qxp 9/2/08 3:49PM PM Page Page706 706 1059997_1001.qxp 9/2/08 3:49 PM Page 706 1059997_1001.qxp 9/2/08 3:49 PM Page 706 10-1.qxd 3/12/099/2/08 16:44 3:49 Page 706 1059997_1001.qxp 9/2/08 3:49 PM Page 706 1059997_1001.qxp 9/2/08 3:49 PM Page 706 1059997_1001.qxp 9/2/08 3:49 PM Page 706 1059997_1001.qxp 9/2/08 3:49 PM Page 706 1059997_1001.qxp 9/2/08 3:49 PM Page 706 1059997_1001.qxp 9/2/08 9/2/08 3:49 3:49 PM PM Page Page 706 706 1059997_1001.qxp 706 706 706 706 706 706 706 706 706 706 706 706 706 CAPÍTULO 10Conics, Cónicas, ecuaciones paramétricas y coordenadas polares Chapter 10 Parametric Equations, and Polar Coordinates Chapter 10 Conics, Parametric Equations, and Polar Coordinates Chapter 10 Parametric Equations, and Polar Coordinates Chapter 10 Conics, Conics, Parametric Equations, and Polar Coordinates Chapter 10 Conics, Parametric Equations, and Polar Coordinates Chapter 10 Conics, Parametric Equations, and Polar Coordinates Chapter 10 Conics, Parametric Equations, and Polar Coordinates Chapter Conics, Parametric Equations, and Polar Coordinates Chapter 10 Conics, Parametric Equations, and Polar Coordinates Chapter 1010 Conics, Conics, Parametric Equations, and Polar Coordinates Chapter 10 Parametric Equations, and Polar Coordinates Chapter 10 10 Conics, Conics, Parametric Parametric Equations, Equations, and and Polar Polar Coordinates Coordinates Chapter Exercises www.CalcChat.com forforworked-out solutions to odd-numbered exercises. 10.1 Ejercicios SeeSee 10.1 Exercises See www.CalcChat.com worked-out solutions odd-numbered exercises. 10.1 Exercises www.CalcChat.com for worked-out solutions tototo odd-numbered exercises. 10.1 See www.CalcChat.com for worked-out solutions toodd-numbered odd-numbered exercises. See www.CalcChat.com worked-out solutions to odd-numbered exercises. Exercises See www.CalcChat.com forfor worked-out solutions exercises. 10.1 Exercises See www.CalcChat.com for worked-out solutions to odd-numbered exercises. 10.1 Exercises See www.CalcChat.com for worked-out solutions to odd-numbered exercises. 10.1 Exercises See www.CalcChat.com for worked-out solutions to odd-numbered exercises. 10.1 SeeSee www.CalcChat.com for worked-out solutions to odd-numbered exercises. www.CalcChat.com for worked-out solutions to odd-numbered exercises. En10.1 los ejercicios 1 amatch 8, relacionar laSee ecuación con sugraph. gráfica. [Lassolutions En los ejercicios 17 find a 20, the hallar el vértice, eland focodirectrix y la directriz de See www.CalcChat.com for worked-out worked-out solutionsIn to odd-numbered odd-numbered exercises. Exercises www.CalcChat.com for to exercises. In Exercises 1– 8, the equation with its [The Exercises 17–20, vertex, focus, of the In Exercises 1– match the equation with its graph. [The In Exercises 17–20, find the vertex, focus, and directrix the In 8,8,8, In Exercises 17–20, find the vertex, focus, and directrix ofofof the InExercises Exercises1– 1– 8,match matchthe theequation equationwith withits itsgraph. graph.[The [The In Exercises 17–20, find the vertex, focus, and directrix of the In Exercises 1– 8, match the equation with its graph. [The In Exercises 17–20, find the vertex, focus, and directrix of the In Exercises 1– match the equation with its graph. [The In Exercises 17–20, find the vertex, focus, and directrix the gráficas están marcadas a),(c), b), (d), c), d), e),(f), f),with g) yand h).] In Exercises 1–1– 8,(a), match the equation its graph. [The graphs are labeled (b), (e), (g), (h).] graphs are labeled (a), (b), (c), (d), (e), (f), (g), and (h).] In Exercises 8, match the equation with its graph. [The graphs are labeled (a), (b), (c), (d), (e), (f), (g), and (h).] In Exercises 1– 8, match the equation with its graph. [The graphs are labeled (a), (b), (c), (d), (e), (f), (g), and (h).] graphs are labeled (a), (b), (c), (d), (e), (f), (g), and (h).] graphs are labeled (a), (b), (c), (d), (e), (f), (g), and (h).] In Exercises 1– 8, match the equation with its graph. [The In Exercises 1– 8, match the equation with its graph. [The graphs are labeled (a), (b), (c), (d), (e), (f), (g), and (h).] y graphs are labeled (a), (b), (c), (d), (e), (f), (g), and (h).] [The a) b) y y graphs are labeled (a), (b), (c), (d), (e), (f), (g), and (h).] In Exercises 1– 8, match the equation with its graph. [The graphs are labeled (a), (b), (c), (d), (e), (f), (g), and (h).] In Exercises 1– 8, match the equation with its graph. (a) (b) graphs are labeled (e), (f),yy(g), yyy and (h).] yy yyy (a), (b), (c), (d), (a) (b) (a) (b) (a) (b) (a) (b) (a) (b) y(g), y (a), graphs are labeled labeled (b), (c), (c), (d), (d), (e), (f), (g), and (h).] (h).] (a)(a) are (b)(e), graphs (f), y and y(a), (b), 8 4 y y (b) y y 4 (a) (b) (a) (b) 4 444y 88 888y (a) (b) 4 686yy (a) (b) 224 yy4 668866 8 (a) (b) 4 486 44686444 6 864 4 64464 x −8− 8−6−6 4 4 − 2− 2 222 222444 444 −−8−8 8−6 −6 −2 −6 8−−6 −−2−22 2 4 − 8 −6 −−4−24 −8 2 4 −−88−6 −6 −6 −6 −4 −−−−−422−244− 2 222 444 −8 −4 − 4 22 44 − 8 −6 −8 −6 −8 − 4 − 4 − 2 yy−y24 (c) c)(c) yy yy (c) (c) (c) (c) −−y44 (c)(c) y (c) yyy (c) (c) 4 4yy 4 (c) (c) 44 44 2242 224422 4 42 xx x x xx 2 − 6−−4 − 4 − 2 −6 −2 422242 22 2444 4666 6 xx 666−4 − 4 − −−6−6−−4 − 2 2 6 6 4 4 −−44−−2−22 2 22 4 6 x − 6 −4−4 −2 2 4 6 xxx −6 − −−4422−2 2 4 6 −4−444 222 444 666 xx −−−666−−−444− −−−4222− −4 −−66 −−44 −−−−22−444 − 4 22 44 66 −−44 (e) (e) e) y (e) (e) (e) (e) (e)(e) (e) (e) (e) (e) (e) 4 2 2244222 2 x 4242 2 2 22 44 4 2 22 22 44 44 22 2 4 2 4 −4 222 444 −4−4 −4 −4 −4 −4 2 4 4 2 −4 −4 −4y−4 −4 y y (d) d) (d) (d) −4yyyyy (d) −4 (d) (d) (d)(d) y (d) 4 (d) 44 444yyy (d) 4 (d) 2244 yy4 (d) 2244222 2 x 4242 2 2 22 2 44 4 66 6 2 4 6 2 22 4 44 6 66 − 2222 −2 2 4 6 −−2− −2−22 2 24 46 6 −−−−4−2224− 2 22 44 66 −4 −−4−42−44 22 44 66 −4 −22 − 4 −− −−444 (f(f) ) (ff) (f)(f(f ) )) −−44 y (f ) (f(f)))(f ) (f (f)) (f x −8 −4 −2 2 4 −4 −6 −8 y yy yyy y 6 y y 66 666yy 6 6 yy6 266 2266222 2 − 6 6 − 2− 2222 2 2 2 6 −−6− −6−66 −−2−2−22 22 22 66 666 x −6 − 222 2 6 − 6 − 2 2 6 −−−666 −−−222 222 666 − 6− 6 −−−622−6−66 22 −−66 66 −6 −−666 − 6 − 4x4x 1. y22y2 225 25 −4x 4x 1.1.1. −4x 66 5 1.yyyy5 1. 55 4x (g) (g) (g) (g) (g) (g) g) (g)(g) (g) (g) (g) (g) (g) 2 1 x −3 −1 1 3 −2 yy yyy yy y y 4 yyy 444 444 y y 4 242 4 2224422 2 4242 2 −2−2 2 2 4 6 x −2 −2 −2 −2 − 2−222 222 222 444 444 666 666 −2 −2 2 4 6 −−2 −2−22 −2−2 −2 2 24 46 6 −2 −2 −2 −−−4−224− 2 22 44 66 −−4−42−44 −4 −2 −2 22 44 66 −4 −22 − 4 −− −−444 2 2s y y112d2d 2. sx x1 2 22d5 25 25 −−1 4444dd4 2s2ys 1 2d 2.2.sxs1 (h) (h) (h) (h) (h) (h) h) (h)(h) (h) (h) (h) (h) (h) 144d4d2d 55 522s2yssyy11 122d2dd 2.sxssxx11 2. 2. sx2 y22 y52 5 4x 4x 4dd22242 5 2ys 1 y s1 22 d2 2d 1. 1. 2. s2. s1 x2241 d52ss225 y1dd1221 5 1. 2. sxsxxssxs2 5 4x 1 5 sss1 1 1. 2. 25 2 2 5 22s y 2 2d xxx2 2 222dd2d2dd2d21 yyyyy211 544x 4x 1 4 2 1 1. syyyxy2221 2. s x d y 1 5 4x 1 4 1. 2. 2 1 2 s 1 d 1 3. 4. s 2 s y 1112d1d22d2ddd25 2 22d5 2 2 s x 1 4 5 22 s y 2 2 d 1 5 3. 4. s x 2 2 d s y 1 2 2 s x 1 4 d 22 s y 2 2 d 1 11111 3.3. 4. 144x 522 22 222d2dd 3.syyxs2sxx1 4.ssxx 16 1 4d4d2d 55 22 ssyy22 1 5 3. 4. 212s y41 22d25 25 22221 s y 5 4. 5 4x 1 4 d 5 1. 2. s x 2 d s y 1 1 d 5 1 4 d 5 2 s y 1 2 d 1. 2. 16 4 2d2 1 ssyy4 2dd2 5 2 2 1 1 sx s1x 1 4d2245 22 s y 2 2 d 1 1 3. 3. 4. 16 16 4 16 4 s x 2 2 1 1 2 16 4 s x 2 2 d s y 1 1 d sx2 2 d2 1 d5 22 5 s2 y 22 2d 1 5 22 5 3. 4. 162y16 1 444d2dd2 5 2222 2 1 s1y 14 14d225 51115 1 3. xss2sx2xx21 4. x4. 3. 4.4. sssyyy 2 22ddd 1 5 221 2 2 2xx 2 16 4 s 2 2 d s y 1 1 d 2 yy2y222 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 s 2 2 d s y 1 1 d 2 2 2 x y 16 4 16 4 x x y 16 4 5 122 11 5. 6. xxxx2 11yyy2 5 xxx1 11 5 22 2 22dd 15 5 11 3. 4. 1 4y49ydydy2225 5 1 5 3. 4. 5 111 ssyy 2 5. 6. y 1 1 5 1 5.5. 6. 1 5 1 5 1 5.s4sxxx42221 6. 1 5 1 5 1 5. 6. 2 2 2 2 16 16 1 5 1 1 5 1 6. 4 x16 216 222 16 222 y5 1 4 x4x244x19y1 y9y29992 y5 5 1 116 5. 45. 6.16 16 16 16 x16 y216 16 x16 xx16 yy16 1 5 1 5 5. 6. 225 1 x2922225 5 111 1 12y1 51y115 12 21 5. yx2422221 6. s6. 1 5. 6. 1 5 xx16 dy16 222 22 4 9 16 16 2 2 4 9 16 x y y 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 x x y 2 2 2 2 y x s x 2 2 d y 4 9 16 9xss2 yy4yy2 2 xx9xx25 sxs16 22d916 yy11yy2551 1 2 xx1 2 2d2d2d2 1 7. 8. 12 55 5 5. 6. 1 5 5 5. 6. 2 7. 8. sx 2 216 d222 y 5y5 2 1111111 1 11 7.7. 8.8. 7.16 8.16 2 5 2 7. 8. 221 25 224 25 91 2 2 16 16 x5 s2 x999222 4yy416 9x1x9x221212155 2 222d 222 y21 y s x 2 d y4y22424245 1 2 5 15 1 1 7.16 8. 9 4y2 16 16 s x 2 2 d 16 9 y x s x 2 d 2 5 1 7. 8. 2 5 1 2 5 7. 8. 16 1 9 4 2 5 1 2 5 7. 8. 2 xx1122 5 7. y16 8. ssxx 2 22 16 11 9dd22 2 y4y4422 5 4 111 9 y 2 2 2 16 9 16 1 9 InIn Exercises 9–16, find the vertex, focus, and directrix ofofthe 2 9–16, 59–16, 2 5 11 of 7.Exercises 8.focus, 2 5 11 find 2 5 7. 8. Exercises find the vertex, focus, and directrix the In the vertex, directrix the In Exercises 9–16, find the vertex, focus, and of the In Exercises 9–16, find the vertex, focus, and directrix of the In Exercises find the vertex, focus, and directrix of 16 and 4 16 11 9–16, 99 and 4directrix In Exercises 9–16, find the vertex, focus, and directrix of the thethe parabola, sketch itsfind graph. parabola, and sketch its graph. In Exercises 9–16, the vertex, focus, and directrix of parabola, and sketch its graph. In Exercises 9–16, find the vertex, focus, and directrix of the parabola, and sketch its graph. parabola, and sketch its graph. parabola, and sketch its graph. In Exercises 9–16, find the vertex, focus, and directrix of the In Exercises 9–16, find the vertex, focus, and directrix of the parabola, and sketch itshallar graph. En los2 ejercicios 9sketch a 16, el vértice, el foco y la directriz de and graph. 2 1 6y parabola, and sketch its graph. In Exercises 9–16, find the vertex, and directrix of of the the parabola, and sketch itsits graph. In Exercises 9–16, find the vertex, focus, and xfocus, y 225 28x 5 0directrix 9. parabola, 10. 2 parabola, and sketch its graph. 25 22 1 28x 6y 10. la parábola, y trazar su gráfica. xx2xx2x21 yy2yy2y25 28x 6y 555 00000 9.9.9. 10. 5 28x 1 6y 5 9. 10. 5 28x 1 6y 5 9. 10. 5 28x 1 6y 10. parabola, and sketch its graph. x y 5 28x 1 6y 5 0 9. 10. parabola, and sketch its graph. 25d 1 s y 2 3d2 25 0 26d2 21 8s y 1 7d 5 0 x2x21 sx2x22 11. 12. x1 y5 5 28x 1 0y 17d75 10. 28x 5 9. 10. 25 22 5 26y 1 55d51 ddd1 1 yyy22 2 662d62dd2d1 1 11. 12. 5 28x 1 6y 9.ssxs9. 10. 55d28x ssysyss2 33d332d32dd2d5 00000 12. 666y d6y 8005 0 000 11. yyyxss2s1 5 1 5 9. 10. 1 1 2 5 2 1 177d7ddd55 5 11. 12.sxsxxxss2s2 xx1 1 1 2 5 xx2 2 1 yy11 5 11. 12. 5 1 80s888sy8ssyssy1 11. 12. s x 1 5 d 1 s y 2 3 d 5 0 s x 2 6 d 1 1 75 d 750d 05 0 11. 12. 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2235 221 y y 2 4y 2 4x 5 0 1 6y 8x 1 25 13. 14. x y 5 28x 1 6y 5 0 2 2 s x 1 5 d 1 s y 2 d 5 0 s x 2 6 d 1 8 s y 1 11. 12. 9. 10. x y 5 28x 1 6y 5 0 9. 10. 2 2 2 2 s x 1 5 d 1 s y 2 3 d 0 s x 2 6 d 1 8 s y 1 7 d 5 11. 12. 2 2 2 2 2 5 1 25 13. 14. 1 5d4y d2 12 sy4x y4x 2 5 00 2 6d6y d11 1 sy1 y1 1 75 d5 5 11. 12. 4y 4x 5 0330d00d0 5 6y 8x 25 000000 0 13. 14. 1 54y 1 s4x 2 2 66y 1 888x s1 1 725 d5 11. 12. 2 4y 2 5 1 6y 1 8x 5 13.yyssxyy2yx22 14.yyssxyy2yx21 2 4y 2 4x 5 1 6y 1 8x 1 25 13. 14. 2 2 5 1 8x 25 13. 14. y y 2 4y 2 4x 5 0 1 6y 1 8x 1 25 5 0 13. 14. 2 2 24x 2 4y yssx2x22221 xss2xx22221 1 4y 43d04d255 00 8x 12 15. 16. 1 y2 2 2 d21 1 y8x 1 d25 5005 0 y1 2 4y 2 4x 05 1 6y 1 1 13. 14. 11. 12. 1 554y dd1 ss4x y4x 5 2 666y d4y 1 888x ss2 y2 1 775 d5 5 11. 12. 2 4y 2 4x 5 1 6y 8x 1 25 5 13. 14. 2 2y 1 4x 1 4y 2 1 1 8x 2 12 5 15. 16. 2 4y 2 5 1 6y 1 1 25 5 13. 14. 4x 4y 22 434005 000000 4y 11 8x 12 0000000 0 15. 16. 2 2 5 1 25 13. 14. 1 4x1 1 4y 2 455 5 1 4y 1 8x 2 125 5 15.xxyy2yxx22x21 16.yyy2yyy2y21 1 4x 1 4y 2 45 1 4y 1 8x 2 12 5 15. 16. 1 4x 4y 1 4y 8x 2 12 15. 16. y x 1 4x 1 4y 2 4 5 0 1 4y 1 8x 2 12 5 0 15. 16. 2 2 2 2 2 2 1 1 8x 5 00 0 y1 x1 1 1 4 05 0 14. 1 4y 1 8x 2 2 4y 2 4x 5 04 5 6y 1 25 13. 14. yxxyx222 2 2 5 yyyyy2221 5 13. 4x 1 4y 2 5 4y 1 8x 2 12 5 15. 16. 1 4y 4x4x 1 4x 4y4y 2 0442 5 16y 4y1 18x 8x1 225 1212 50005 15.15. 16.16. 1 4x 1 4y 2 00 1 4y 1 8x 2 12 5 15. 16. 22 1 22 1 2 2 y x 1 4x 1 4y 2 4 5 0 1 4y 1 8x 2 12 5 15. 16. y x 4x 1 4y 2 4 5 0 4y 1 8x 2 12 5 0 15. 16. 15. x 1 4x 1 4y 2 4 5 0 16. y 1 4y 1 8x 2 12 5 00 la parábola. Luego usar unavertex, herramienta dethe graficación In Exercises 17–20, the focus, and directrix of para thethe parabola. Then use a afind graphing utility toto graph parabola. parabola. Then use graphing utility graph the parabola. In Exercises 17–20, find the vertex, focus, and directrix of parabola. Then use aafind graphing utility to graph the parabola. In Exercises 17–20, find the vertex, focus, and directrix of the parabola. Then use agraphing graphing utility to graph the parabola. parabola. Then use afind graphing utility to graph the parabola. parabola. Then use utility to graph the parabola. In Exercises 17–20, the vertex, focus, and directrix of the the In Exercises 17–20, the vertex, focus, and directrix of representar la parábola. parabola. Then use a graphing utility to graph the parabola. 1 parabola. Then a graphing utility to graph the parabola. Then use aafind graphing utility to graph the parabola. In Exercises 17–20, find the vertex, vertex, focus, and directrix of the parabola. Then use graphing utility to5graph graph the parabola. In Exercises 17–20, the directrix the yfocus, 5 2 y22y2 221 xThen 11 y y5 0use s111x1s22x2 222 8x 1parabola. 6d6of 17. 18. 161and parabola. use a graphing utility to the parabola. 2 2 y 2 1 x 5 0 2 8x 1 d 17. 18. 22 xxx1 yyy5 00000 sx x22 8x 11 66d66d6ddd 17. 18. 5 1 1 5 2 8x 1 17.yyyyy21 18.yyy5 yyto 5 2 1 xx1 1 yyuse 5 2 8x 1 17. 18. 21 22 5 8x 17. 18. 62 616s66s6sxsxsxx 1 1 5 5 2 2 8x 1 17. 18. 1 the parabola. Then graphing utility utility graph the parabola. 5 2 1 xThen 1 y45 5 00aa0graphing 2 8x 1 6d0 6d 17. 18. parabola. use graph parabola. 2 4x 21 22s8y yyy2y2y222222 2 5 xy2yy2x2to 2x 1 98x 561 19. 20. 2 5 1 x2 1 y5 5 x2 2 17. 18. 11612 5 2 1 x 1 y 5 0 s x 8x 1 17. 18. 2y 2y2 621 22 2 4x 4 0 2x 1 8y 1 9 19. 20. 5 2 1 x 1 y s x 2 8x 1 65 17. 18. 6 y 2 4x 2 4 5 0 x 2 2x 1 8y 1 9 5 0ddd00000 19. 20. y 5 2 y 1 x 1 y 5 0 s x 2 8x 1 65 17. 18. y 2 4x 2 4 5 0 x 2 2x 8y 1 9 19. 20. 6 y 2 4x 2 4 5 0 x 2 2x 1 8y 1 9 5 19. 20. 2 2 4x 2 4 5 0 x 2x 1 8y 1 9 5 19. 20. 6 22 22 y 2 4x 2 4 5 0 x 2 2x 1 8y 1 9 5 19. 20. 1 1 1 yy2222 y1 2 4x 2yy2 45 5 0 0 xy225 222 2x 8y8x 11 95 0 0 19. 20. 2 2 22 2 2 1 x4x1 1 55 s2x x1 2 8x 1 17. 18. 4x 40005 x2 2 1 8y 96dd05 19. 20. y y x s x 6 17. 18. 2 2 25 4x 2 4 x 2x 1 8y 1 9 5 19. 20. 6 6 y 2 2 4 5 0 x 2 2x 8y 1 9 5 19. 20. y 2 4x 21–28, 221–28, 4 5 find 0 findananequation x ofthe 2the 2x 1 8y 1 9 5 00 19. 20. of In Exercises parabola. In Exercises equation parabola. In Exercises 21–28, find an equation of the parabola. In Exercises 21–28, find an equation of the parabola. In Exercises 21–28, find an equation of the parabola. 2 2 2 2 In 21–28, equation the parabola. EnExercises los ejercicios 210find a 28,an hallar una de8y parábola. 2 4x 2 2 5 0find xof 2 2 2x 1 8yla1 1 5 00 19. 20. ecuación yy 2 4x 44 5 xof 1 99 5 19. 20. In Exercises 21–28, an equation the2x parabola. In Exercises find equation of parabola. In Exercises 21–28, find an equation of the parabola. In Exercises 21–28, find anan equation of thethe parabola. s5, 421–28, d4d find 1d1d s22, 21. Vertex: 22. Vertex: In Exercises 21–28, an equation of the parabola. s 5, 22, s 21. Vertex: 22. Vertex: 44d4d44) 11d1d1) s22, 21. Vertex: 22. s(5, 5, 22, 1dd 21.Exercises Vertex:s5, 22.Vertex: Vertex: s21–28, 5, dd find an equation 22, ss(22, 21. Vertex: 22. Vertex: ss5, ss22, 21. Vertex: 22. Vertex: Vértice: 22. Vértice: 21. In of the parabola. parabola. 5, 22, 1d d1d 21. Vertex: 22. Vertex: In Exercises 21–28, an equation of the s3, 4s4d445,ddd 4d find 21 s22, Focus: Focus: s22, Vertex: 22. Vertex: s 5, 22, 1 d s 21. Vertex: 22. Vertex: s 3, 22, 21 s Focus: Focus: 5, 1 d d ddd 21.21. Vertex: 22. Vertex: s 3, 4 d 22, 21 s Focus: Focus: s 5, 4 d 22, 1 d s 21. Vertex: 22. Vertex: s 3, 4 d 22, 21 s Focus: Focus: s 3, 4 d 22, 21 s Focus: Focus: Foco: (3, 4) Foco: (22, 21) ss3, 44dd 21 ss22, Focus: Focus: 3, 22, 21 d d Focus: Focus: 5, 4dd5dddd4d 22, 1dd21 ss22, 21. Vertex: 22. Vertex: sssss0, 5443, ss2, 2s22, d2d21 23. Vertex: 24. Focus: s Focus: Focus: 5, 22, 1 s 21. Vertex: 22. Vertex: 3, Focus: Focus: s 0, 2, 23. Vertex: 24. Focus: 3, 4 22, 21 s Focus: Focus: 23. Vértice: 24. Foco: 545dd5d55) 22dd22d21 23. 24. 22, s2, Focus: 0, 2, d ddd 23.Vertex: Vertex:ss0, 24.Focus: Focus:ss2, ss(0, 0, dd ss2, 23. Vertex: 24. Focus: ss3, 0, 23. Vertex: 24. Focus: 0, 5 d s 2, 2 d 23.23. Vertex: 24. Focus: y45y0, 5 22 Directrix: Directrix: 22, 21 s22, Focus: Focus: 523 d23 222 d22 Vertex: Focus: ssss3, dddd5 21 dd Focus: Focus: 0, 2, 23. Vertex: 24. 23 xx5 5 22 Directrix: Directrix: s3, 0, d5 2,xxsx22x2, 25 d5 23.Directrix: Vertex: 24.24. Focus: Directriz: Directriz: yy4sy55 23 Directrix: 0, sss2, 23. Vertex: 24. Focus: 5 23 xdd5 522 22 Directrix: Directrix: y5y5 5 23 5 22 Directrix: Directrix: 23 Directrix: Directrix: y 5 23 x 5 22 Directrix: Directrix: y y s 0, 5 d s 2, 2 d 23. Vertex: 24. Focus: 25. 26. y 5 23 x 5 22 Directrix: Directrix: s 0, 5 d s 2, 2 d 23. Vertex: 24. Focus: yyy yyyyy y y 5 23 x 5 22 Directrix: Directrix: y y 25. 26. 5 23 x 5 22 Directrix: Directrix: 25. 26. y y 25. 26. x 5 22 25.Directrix:y y 5 23 26.Directrix: 25. 26. 25. 26. y (2,(2, 4)4) (0, 4) 23 25.25. 26.26. y (2, y4) (2, 4) y 5 x 5 22 Directrix: Directrix: y y 4) (0, 4) y 5 23 x 5 22 Directrix: Directrix: (2, 4) (2, 4) (0, y y 4 (2, 4) (0, 4) 25. 26. y (0, 4) 25. 26.444444y 25. 26. (2, (2, 4) 4) (0, (0, 4) 4) (2, 4) (0, 4) (2,4) 4) (0,4) 4) 25. 26. 344 yy4 (2, 25. 26. 3 yy (0, 3 33443333 333333 (2, 4) 4) (2, (0, 4) 4) (0, 2332 3 2443 3 3 2 22322 223332222 2 1332 2 33 2 112221111 (0, 0) 222 (−2, 0) (2, 0)0) (4, 0)0) (0, 0) (−2, 0) (4, (2, (2, 0) (0, 0) (4, 1 (0, (−2, 0)0) (2, 0)0) 0)0) (4, 0)0) (−2, 0) (2, 0) (−2, (2, (−2, (2, (0, 0) 0) (4, 0) (4, 0) x0) x0) (4, 1 (0, 20) 20) 2121 (0, (−2,(−2, (2, x(2, 0) 0) 20) 3 (4, x(4, 0) 1 (0,1 (0, xxxxx0) xxxxx0) 0) −1 1 (−2, 0) (2, 0) (0, 0) (4, 0) x x (−2, 0) (2, 0) (0, 0) 1 2 3 (4, 0) −1 1 1 2 3 −1 1 (−2, 0) (2, 0) (0, 0) 1 2 3 (4, 0) −1 1 −1 −1 1 11 2 22 3 33 −1 1 11 x x 11 10) 2 3 −1 0) 1 xxx xxx (−2, 0) (2, 0) (0,through (4, 0) (−2, (2, 0) (0, 1 22 2 33s0,3 3(4, 110) −1 11 1toto yd3,d0) s(3, 3, 44)d4,dy, 27. Axis isis−1 parallel axis; graph passes −1 1 2 3 −1 1 ys 0, , s 3, 27. Axis parallel axis; graph passes through El eje es paralelo al eje y; la gráfica pasa por (0, 3), 27. x x x x ys 0, 3 d , s 3, 4 27. Axis is parallel to axis; graph passes through y-axis; 0,33d3,dd,,s3, 3,4d4,d4,dd,, 27.Axis Axisisis isparallel paralleltoto toy-yaxis;graph graphpasses passesthrough throughs0, ss0, ss3, 27. Axis parallel graph passes through 27. y-axis; 27.27. Axis is11 parallel axis; graph passes s−1 4, and 11through 22 33 s0,s3 −1 s4, 11 . 11 to to and y-axis; 0,d,3sd3, , s43,d,4d, Axis isd.dparallel graph passes through (4, s11). 4, 11parallel d.d.dd.. to y0, 3, 27. Axis is parallel to axis; graph passes through 4, 11 and ssis 4, 11 and ss4, and y-axis; 0,333ddd,,, sss3, 3,444ddd,,, 27.and Axis parallel to yaxis; graph graph passes passes through through sss0, 27. Axis 4,iss11 11 . 5d. 22; and yd11 s0, 2sd2s3, 28. Directrix: endpoints ofofpasses latus rectum are and 4, and s 4, 11 d . and ys 0, 3 d , 3, 4and 27. Axis is parallel to axis; graph passes through y 5 22; s 0, d 28. Directrix: endpoints latus rectum are s 4, 11 d . and ys 0, 3 d , 4and dd,, 27. Axis is parallel to axis; graph through y 5 22; 28. Directriz: extremos del lado recto (latus rectum) son 22; s0, 22d2d2dand 28. ofofof latus rectum are s4, 11ydy. 5 and 5 22;endpoints 0, dand 28.Directrix: Directrix: endpoints of latus rectum are yy55 22; ss0, 28. Directrix: endpoints latus rectum are and 22; ss0, 28. Directrix: endpoints latus rectum are y 5 22; 0, 2 d 28.28. Directrix: endpoints of latus rectum are and sand 8, 2 d . s 4, 11 d . and s 8, 2 d . y 5 22; s 0, 2 d Directrix: endpoints of latus rectum are s 4, 11 d . y s 0, 2 d s 8, 2 d . s 8, 2 d . 22; 0, 28. Directrix: endpoints of latus rectum are and 8, 22dd.. y 5 ss8, 8, 5 22; 22; endpoints 0,222ddd and 28. sDirectrix: endpoints of of latus latus rectum rectum are are sss0, andand 28. sDirectrix: 8,s228,dd..2d. yy 5 s 8, 2 d . y 5 22; s 0, 2 d 28. Directrix: endpoints of latus rectum are and s8,8,22dd.. 29–34, y 5 22; s0, 2d and 28.Exercises endpoints of latus rectum areeccentricity sDirectrix: In find the center, foci, vertices, and In Exercises 29–34, find the center, foci, vertices, and eccentricity En los ejercicios 29 afind 34, hallar elfoci, centro, el foco, el vértice y la In Exercises find the center, vertices, and eccentricity In 29–34, the center, foci, vertices, and eccentricity In Exercises 29–34, find the center, foci, vertices, and eccentricity In Exercises 29–34, find the center, foci, vertices, and eccentricity s8, 8,ellipse, sExercises 22dd.. 29–34, In Exercises 29–34, find the center, foci, vertices, and eccentricity of the and sketch its graph. of the ellipse, and sketch its graph. In Exercises 29–34, find the center, foci, vertices, and eccentricity excentricidad de la elipse y trazar su gráfica. ofof the ellipse, and sketch its graph. In Exercises 29–34, find the center, foci, vertices, and eccentricity of the ellipse, and sketch its graph. of the ellipse, and sketch its graph. ellipse, and sketch its graph. Inthe Exercises 29–34, findthe the center, foci,vertices, vertices,and andeccentricity eccentricity In Exercises 29–34, find foci, of the ellipse, and sketch itscenter, graph. of the ellipse, and sketch its graph. 2 1 229–34, 2vertices, 2 5 of the ellipse, and sketch its graph. In Exercises find the center, foci, vertices, and eccentricity of the ellipse, and sketch itscenter, graph. In Exercises find the foci, and 3x3x 16x y229–34, 5 1616 1 7y7y 6363eccentricity 29. 30. 2 2 2 2 of the ellipse, and sketch its graph. 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 16x 1 y 5 1 5 29. 30. 29. 30. 16x yyyy2555 16 7y7y 63 29. 30. 3x111 16x 1 5 16 1 7y555 5 63 29. 30.3x 3x 16x 1 16 63 29. 30. 3x 16x 1 16 63 29. 30. 21 of the ellipse, and sketch its graph. graph. 3x223x 16x 1 y2 22and 5 16 12 7y 7y 227y 5 63 29.the 30.30. of ellipse, sketch s16x x16x 2 d32222dy1 s2ys16 2 1d1222d222 its s52ys y63 1 6d6222d222 16x 5 16 1 5 22233 22 1 22 s5 3x 1 5 1 7y 5 29. 30. 222 y 27y s x 2 y 2 1 3x 1 y 5 16 1 63 29.29. 30. s x 2 d s y 2 1 d y 1 663 3x 16x 1 y 5 16 7y 63 29. 30. s x 2 3 d s y 2 1 d s y 1 s x 2 3 d s y 2 1 d s y 1 1 5 1 s x 1 4 d 1 31. 32. s x 2 3 d s y 2 1 d s y 1 6d66d6dd2d551 1 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 1 5 1 s x 1 4 d 1 31. 32. sx 16 2 3d2y21 2 1d225 s y63 1 1111 32. 44d4d47y 1111 31. 1 1 31.16x 32.sxs3x xx21 d2d11 1 5 31. 32. 21 25 25 25 1y4 2 1 21 31. 32. 2x 22 221 xsxs1 31. 32. 225 3x 16x y31 5sssyy16 16 1 7y 5 63 29. 30. s 2 d s y25 2 15 d s y 61 65 d5 1 5 1 5 29. 30. 16 25 1y4 2 2 s x 2 3 d 2 1 d s y 1 1 5 1 5 1 1 s 1 4 d 1 31. 32. 16 25 1y4 16 25 1y4 16 1y4 s x 2 3 d y 2 1 d s y 1 2 16 25 1y4 sx22 3d 21 s1y 2 1d 5 1 66ddd2 5 5 1 32. 5 s1 x 41 d1 s1y 1y4 32. 22241 1 s x 1 d 31. 16 25 1 5 1 s x 4 d 5 31.31. 32. 1 5 1 5 111 s x 1 4 d 1 31. 32. 9x 1 4y 1 36x 2 24y 1 36 5 0 33. 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 16 25 1y4 2 2 16 25 1y4 s x 2 3 d s y 2 1 d s y 1 6 d 2 2 2 2 s x 2 3 d s y 2 1 d s y 1 6 d 33. 9x 1 4y 1 36x 2 24y 1 36 5 0 2 2 9x 1 4y 1 36x 2 24y 1 36 5 0 33. 16 25 1y4 4y 111 36x 24y 1 3636 5 0 ss00xx 1 33. 16 25222 1y4 5 9x1 1 4y1 1 36x 2 24y 1 36 5 33.9x 9x 4y 36x 24y 1 5 33. 22 1 9x 11 4y 36x 24y 5 33. 2 1 5 5 11 31. 32. 5 111 31. 32. 9x229x 4y 1 1 36 36 5 05 0 5010 44dd 1 33.33. 21 22 36x 2 24y 2 1 25y 64x 1 150y 1 279 16x 34. 16 25 1y4 22 22 2 21 1 36x 2 24y 1 36 16 25 1y4 222 224y 9x 1 4y 36x 2 24y 1 36 5 005 33. 21 236x 21 22 34. 16x 25y 2 64x 1 150y 1 279 5 0000 21 22 1 25y 2 64x 1 150y 1 279 5 16x 34. 9x 1 4y 1 36x 2 24y 1 36 5 33. 25y 64x 1 150y 1 279 0 34. 9x 4y 1 2 24y 1 36 5 0 33. 1 25y 2 64x 1 150y 1 279 5 16x 34.16x 1 25y 2 64x 1 150y 1 279 5 16x 34. 1 25y 2 64x 1 150y 1 279 5 0 16x 34. 2 2 2 64x 1 150y 1 279 5 0 25y 16x 34.34. 24y 2 22 22 2211 22 25y 9x 1 36x 24y 1150y 36 5 33. 1 1 1 0 9x 1 36x 264x 24y 1 36 00279 33. 21 222 2 1 25y 2 1 150y 1 279 5 16x 34. 14y 25y 2 64x 64x 1the 150y 15 279 5 005 0 and 16x16x 34.Exercises 1 25y 1 150y 1 279 5 16x 34. In 35–38, find center, foci, vertices of the En los ejercicios 35 64x afind 38, hallar el centro, eland foco yvertices el vértice de la In Exercises 35–38, find the center, foci, and the In Exercises 35–38, the center, foci, vertices ofofof the In Exercises 35–38, find the center, foci, and vertices of the In Exercises 35–38, find the center, foci, and vertices of the 2 2 2 2 In Exercises 35–38, find the center, foci, and vertices the 1 25y 2 64x 1 150y 1 279 5 0 16x 34. 1 25y 2 64x 1 150y 1 279 5 0 16x 34. In Exercises 35–38, find the center, foci, and vertices of of thethe ellipse. Use a graphing utility to graph the ellipse. elipse. Con ayuda de una herramienta de graficación represenellipse. Use a graphing utility to graph the ellipse. In Exercises 35–38, find the center, foci, and vertices ellipse. Use a graphing utility to graph the ellipse. In Exercises 35–38, find the center, foci, and vertices of the ellipse. Use a graphing utility to graph the ellipse. ellipse. Use a graphing utility to graph the ellipse. ellipse. Use a graphing utility to graph the ellipse. In Exercises 35–38, find the center, foci, and vertices of the In Exercises find the to center, foci, and vertices of the ellipse. Use a 35–38, graphing utility graph thethe ellipse. tar la elipse. ellipse. Use a2 2graphing utility to graph ellipse. 2Use ellipse. aa graphing graphing utility to graph the ellipse. In Exercises 35–38, find the center, foci, and vertices of of the the ellipse. Use graphing utility to graph the ellipse. ellipse. In Exercises 35–38, find the center, and vertices 12x 1 20y 2 12x 1 40y 2 37 550foci, 35. 2 ellipse. a utility to graph the 22Use 222 2 2 2 2 12x 1 20y 2 12x 1 40y 2 37 0 35. 12x 1 20y 12x 1 40y 2 37 5 0 35. 12x 1 20y 2 12x 1 40y 2 37 5 0 35. 12x 1 20y 2 12x 1 40y 2 37 5 0 35. 12x 1 20y 2 12x 1 40y 2 37 5 0 35. 2 2 ellipse. Use a graphing utility to graph the ellipse. 12x 1 20y 2 12x 1 40y 2 37 5 0 35. ellipse. Use a graphing utility to graph the ellipse. 2 2 2 2 2 2 221 36x 9y 48x 2 36y 1 4343 537 0 00 0 36. 35. 12x 1 20y 2 12x 1 40y 2 37 5 2 1 2 12x 1 40y 2 35. 212x 2220y 2221 12x 20y 2 12x 1 40y 2 37 5 35. 221 21 22 36x 1 9y 48x 2 36y 1 36. 12x 1 20y 2 12x 1 40y 2 37 35. 36x 9y 48x 22 36y 11 43 555 05000005 36. 12x 20y 2 12x 1 40y 2 37 5 35. 36x 1 9y 1 48x 2 36y 1 43 36. 36x 1 9y 1 48x 2 36y 1 43 5 36. 36x 1 9y 1 48x 36y 43 36. 21 21 36x 9y 48x 2 36y 1 43 5 0000 0 36. 2 2222 1 21 223x 2 21 221 2 x 1 2y 2 4y 0.25 5 0 37. 12x 1 20y 12x 1 40y 2 37 5 35. 36. 36x 1 9y 1 48x 2 36y 1 43 5 2 2 2 2 36x 9y 48x 2 36y 1 43 36. 12x 1 20y 2 12x 1 40y 2 37 5 35. 236x 229y 36x 1 48x 2 36y 1 43 5 36. 22 2 22 22 xx2x21 1 2y 3x 1 4y 1 0.25 5 000 005 37. 1 9y 1 48x 2 36y 155 43 5 0 36. xx36x 2y 2 3x 1 4y 11 0.25 005 37. 1 9y 1 48x 2 36y 1 43 36. 1 2y 2 3x 1 4y 1 0.25 5 37. 1 2y 2 3x 1 4y 1 0.25 5 37. 1 2y 2 3x 1 4y 0.25 37. 2 xx222 x1 2y 3x 1 4y 1 0.25 5 05 37. 222 2 222 1 222 4.8x 2x y 1 2 6.4y 1 3.12 0 38. 36x 9y 1 48x 2 36y 1 43 36. 1 2y 2 3x 1 4y 1 0.25 5 0 37. 2 2 2 2y 2 3x 1 4y 1 0.25 5 0 37. 36x 1 9y 1 48x 2 36y 1 43 36. 2 2 2 x 1 2y 2 3x 1 4y 1 0.25 5 0 37. 2 2 2 2 2 2 2x 1 y 1 4.8x 2 6.4y 1 3.12 5 38. 1 2 3x 1 4y 11 0.25 55 37. 2x y2y 4.8x 224y 6.4y 3.12 00000 38. xx2x 2y 2 3x 1 1 0.25 5 0055 37. 2x21 1 1 4.8x 2 6.4y 1 3.12 5 38. 1 4.8x 2 6.4y 1 3.12 38. 2x 11 yyyy211 4.8x 6.4y 1 3.12 38. 2x 1 4.8x 2 6.4y 1 3.12 5 00 0 38. 211 22 22y 2 1 22 21 2222 x 3x 1 4y 1 0.25 5 0 2x 1 y 1 4.8x 2 6.4y 1 3.12 5 37. 38. 2 2x 1 y 4.8x 2 6.4y 1 3.12 38. x 2y 2 3x 1 4y 1 0.25 5 0 37. 2x 1 1 4.8x 2 6.4y 1 3.12 5 38. 2x2 1 1 yyy239–44, 1 4.8x 4.8xfind 2 6.4y 6.4y 1 3.12 3.12 5 5of005 0the ellipse. 38.Exercises 2x 1 2 1 38. In ananequation In Exercises 39–44, find equation of the ellipse. In Exercises an equation ofof0of the ellipse. In Exercises 39–44, find an equation the ellipse. In Exercises 39–44, find an equation the ellipse. 239–44, In Exercises find an equation the ellipse. 2x22 1 1 yy239–44, 1 4.8xfind 2 6.4y 1 3.12 5 5 0of 38. 2x 1 4.8x 2 6.4y 1 3.12 38. In Exercises 39–44, find an equation of thethe ellipse. En los ejercicios 39 a 44, hallar una ecuación de In Exercises 39–44, find an equation of ellipse. In Exercises 39–44, find an equation of the ellipse. In Exercises 39–44, find an equation of the ellipse. s0, s 0, 0 d 3la d, selipse. 8, 3d 39. Center: 40. Vertices: In Exercises 39–44, find an equation of the ellipse. sss0, sss0, sss8, 39. Center: 40. Vertices: s0, s0, 00d00d0ddd 33d333,d3,ddsd,,8, 33d33d3ddd 39. Center: 40. Vertices: 0, 0, 8, 39. Center: 40. Vertices: 0, 0, 8, 39. Center: 40. Vertices: s s 0, 0, s,s8, 39. Center: 40. Vertices: In Exercises 39–44, find an equation of the ellipse. s s 0, 0 d 0, 3 d , 8, d 3d 39. Center: 40. Vertices: In Exercises 39–44, find an equation of the ellipse. 3 s 5, 0 d Focus: Eccentricity: 0, 0ddd 0d Centro: 40. Vértices: (0, (8, 3) 39. 333d8, , s338, Center: Vertices: 5, Focus: Eccentricity: sssss0, 0, 0, 39. Center: 40. Vertices: 0, 0,s343340, 3343), 8, 39.39. Center: 40.40. Vertices: s5, 00ds0000d0, Focus: Eccentricity: 5, 0ddd Focus: Eccentricity: 5, Focus: Eccentricity: 3dd44d,4,,sss8, sss5, sss0, 33ddd Focus: Eccentricity: 39. Center: 40. Vertices: 3 5, 0 d Focus: Eccentricity: 3 sss5, 6, 05,d 0d Vertex: Foco: Excentricidad: s00) Focus: Eccentricity: 0, 33344d3d,, ss48, 8, 33dd 39.Vertex: Center: 40. Vertices: Vertices: ss0, 0, 39. Center: 40. ss0, Vertex: Focus: Eccentricity: 5, Focus: Eccentricity: s(5, s6, 6, Vertex: 6, Vertex: s5, 6, Vertex: ss6, 0000d00dd00dd0ddddd Focus: Eccentricity: 4 s5, 6, Vertex: 343 s 3, 1 d , s 3, 9 d 0, ± 9 d s 41. Vertices: 42. Foci: Vértice: (6, 0) s 6, 0 d Vertex: s 0 d Focus: Eccentricity: ss5, Focus: Eccentricity: ss0s3, sss3, sss0, 41. Vertices: 42. Foci: ss6, 6, Vertex: Vertex: 3, 1d01ddd11,d1,ddsd,,3, 99d99d9ddd ± 9± s0, 41. 42. 3, 0, 41.Vertices: Vertices: 42.Foci: Foci: 3, 3, 0, ±± 41. Vertices: 42. Foci: s6, s,3, 9d999d9ddd4d4 ss0, 41. Vertices: 42. Foci: 003, Vertex: s3, 3, 13, 3, 0,s±± 41. Vertices: 42. Foci: Minor axis length: 6993, Major axis length: 2222 s 3, 1dddd,,,,1ssssd3, 3, 96dddd9d 41. Vértices: 42. Foco: (0, 69) s , s 0, ± 9d 22 41. Vertices: 42. Foci: s 6, 0 d Vertex: s 6, 0 d Vertex: Minor axis length: Major axis s 3, 1 0, ± s 41. Vertices: 42. Foci: s 3, 1 3, 9 0, ± dlength: s 41. Vertices: 42. Foci: Minor axis length: 6 Major axis length: Minoraxis axis length: Major axis 22 Minor axis Major axis length: 22 axis length: 22 s3,length: 1length: d, s3, 9666d6 ± 999 ddlength: s0, 41. Minor Vertices: 42. Major Foci: Minor axis length: Major axis length: 22 22 22 s s 0, 0 d 1, 2 d 43. Center: 44. Center: Longitud del Longitud mayor: Minor axis Major axis length: , ss3, 3,menor: 0, 41. Vertices: 42. Foci: 3, 101dddddeje ,length: 96966dd 6 6 44. 992dlength: dlength: ss0, 41. Vertices: 42. Foci: ss±± sssss0, 00dlength: 22dd2dddeje 43. Center: 44. Center: Minor axis length: Major length: 22 Minor axis Major axis 22 saxis saxis 0, 03, dlength: 1, 2del 43. s1, 0, 1, 43.Center: Center: 44.Center: Center: 0, 1, 43. Center: 44. Center: s s 0, 0 1, 43. Center: 44. Center: Minor Major axis 22 ss1, ss0, 00, dd 0d 6 21, 43. Center: 44. Center: Major axis: horizontal Major axis: vertical 0,s0horizontal 0length: 1,svertical 2dddvertical dvertical 43. Centro: 44. Centro: 2d 22 Center: Center: Minor axis Major axis 22 Minor axis 6 Major axis Major Major axis: saxis: 0, 1, 43. Center: 44. Center: s1, s0, 0, dhorizontal 1, 2length: 43.43. Center: 44.44. Center: Major axis: Major axis: Major horizontal Major vertical Major axis: horizontal Major axis: Major axis: horizontal Major axis: vertical ssaxis: saxis: 00length: ddhorizontal 22length: dvertical 43. Center: 44. Center: Major axis: Major axis: Points on the ellipse: Points on the ellipse: Eje mayor: horizontal Eje mayor: vertical Major axis: horizontal Major axis: vertical s s 0, 0 d 1, 2 d 43. Center: 44. Center: son son 0, 0the dhorizontal 1, 2the dvertical 43. Points Center: 44. Points Center: Points ellipse: Points the ellipse: Major axis: Major axis: vertical Major axis: horizontal Major axis: on the ellipse: on the ellipse: Points on the ellipse: Points on ellipse: Points on the ellipse: Points on the ellipse: Points on the ellipse: Points on the ellipse: Major axis: horizontal Major axis: vertical Points on the ellipse: Points on the ellipse: sMajor 3, 1Points d1,ds,axis: 4, 0on dthe sMajor 1, 6Points d6,ds,axis: 3, 2on dthe Puntos en ladhorizontal elipse: Puntos en ladvertical elipse: the ellipse: the ellipse: Major axis: horizontal Major axis: vertical s 3, s 4, 0 s 1, s 3, 2 Points on the ellipse: Points on the ellipse: Points on ellipse: Points on ellipse: s3, 1 d , s 4, 0 d s 1, 6 d , s 3, 2 d 3,11d1,dd,s,on 4,0the 1,66d6,dd,s,on 3,2the ss3, ss4, 0d0dd ellipse: ss1, ss3, 2d2dd ellipse: sPoints sPoints 1, ss3, 3, 13, dd,,1ss4, 4, 04, dd 0dellipse: sPoints 1, 61, dd,,6ss3, 3, 23, dd 2dellipse: 3, 1 4, 0 s 1, 6 3, 2 s d , s s d , s on the on the Points on the ellipse: Points on the ellipse: ssPoints 3, 1 d , s 4, 0 d s 1, 6 d , s 3, 2 d s3,3,11dd,,ss4,4,00dd ss1,1,66dd,,ss3,3,22dd 3, 11dd,, ss4, 4, 00dd 1, 66dd,, ss3, 3, 22dd ss3, ss1, 1059997_1001.qxp 9/2/08 9/2/08 3:49 3:49 PM PM Page Page 707 707 1059997_1001.qxp 10-1.qxd 3/12/09 16:44 1059997_1001.qxp 9/2/08 3:49Page PM 707 Page 707 SECCIÓN Cónicas y cálculo 10.110.1Conics Conics and Calculus Calculus 10.1 and 10.1 Conics and Calculus In los Exercises 45–52, find the center, center, foci, andyvertices vertices ofdethe the In Exercises 45–52, find the foci, and En ejercicios 45 a 52, hallar el centro, el foco el vérticeof la In Exercises 45–52, find theusando center, foci, and vertices of the hyperbola, and sketch its graph graph using asymptotes as an anayuda. aid. hyperbola, sketch its using as aid. hipérbola, y and trazar su gráfica lasasymptotes asíntotas como hyperbola, and sketch its graph using asymptotes as an aid. xx22 yy22 xx22 45. yy22 2 46. x 2 2 5 11 2 y2 5 5 11 2 x2 5 45. 46. 45. 46. 9 16 5 1 2 9 25 45. y 2 5 1 46. 25 2 16 9 25 1622 2111dd2d22 sssyyy1 1 22d2d22 1 33dd 2 55dd22 ssxx 2 1 ssyy 1 ssxx 2 2 s y 122dd2 5 5111 2 sx 2 5d2 5 5 11 47. ssxx2 48. s y 1 3d2 2 22 2 5 47. 48. 47. 48. 2 1 d 225 2 64 64 5 1 444 111 2 51 47. 48. 225 4 222 1 225 64 9x2222 2yyy 2 236x 36x2 26y 6y1 118 185 5000 49. 9x 9x 2 2 36x 2 6y 1 18 5 49. 49. 49. 9x222 2 y 2 222 36x 2 6y 1 18 5 0 2 16x 16x 1 1 64x 64x 2 2 208 208 5 5 00 50. yy 2 50. 50. 2 1 64x 2 208 5 0 50. y2222 2 16x 22 1 2 x 2 9y 1 2x 2 54y 2 805 5000 51. x 2 9y 2x 2 54y 2 80 5 51. 51. x 2 2 9y 2 1 2x 2 54y 2 80 51. x 2222 9y 2221 2x 2 54y 2 80 5 0 9x 2 24y 4y 1 154x 54x1 18y 8y1 178 785 5000 52. 9x 9x 2 4y 1 54x 1 8y 1 78 5 52. 52. 52. 9x 2 2 4y 2 1 54x 1 8y 1 78 5 0 In los Exercises 5353 56, find the el center, foci, andyvertices vertices ofdethe the In Exercises 53 ––56, find the center, foci, and En ejercicios a 56, hallar centro, el foco el vérticeof la In Exercises 53aa–graphing 56, find utility the center, foci,the and vertices and of the hyperbola. Use graphing utility to graph graph the hyperbola and its hyperbola. Use to hyperbola its hipérbola. Trazar la hipérbola y sus asíntotas con ayuda de una hyperbola. a graphing utility to graph the hyperbola and its asymptotes.Use asymptotes. herramienta de graficación. asymptotes. 9y2222 2xxx2221 12x 2x1 154y 54y1 162 625 5000 53. 9y 9y 2 1 2x 1 54y 1 62 5 53. 53. 53. 9y222 2 x222 1 2x 1 54y 1 62 5 0 9x 2 y 1 54x 1 10y 1 55 5000 54. 9x 2 y 1 54x 1 10y 1 55 5 54. 2 2 54. 9x 22 y 21 54x 1 10y 1 55 5 54. 9x22 2 y 221 54x 1 10y 1 55 5 0 3x2 2 22y 2y2 2 26x 6x2 212y 12y2 227 275 5000 55. 3x 3x 2 2y 2 6x 2 12y 2 27 5 55. 55. 55. 3x 222 2 2y222 2 6x 2 12y 2 27 5 0 3y 2 x 1 6x 2 12y 5 0 56. 3y 2 x 1 6x 2 12y 5 0 56. 2 2 56. 3y 22 x 21 6x 2 12y 5 0 56. 3y 2 x 1 6x 2 12y 5 0 In Exercises Exercises 57– 57–64, 64, find find an an equation equation of of the the hyperbola. hyperbola. In En ejercicios 64, hallar una ecuación de la hipérbola. In los Exercises 57–57 64,afind an equation of the hyperbola. 1, 00dd 0, ±±44dd 57. Vertices: Vertices:ss±±1, 58. Vertices: Vertices: ss0, 57. 58. 58. 57. s0,64) ± 4d 57. Vértice: Vertices:s±s±1,1,0d0d 58. Vértice: Vertices:(0, 5 ±±5x 5x 5 ±±2x 2x Asymptotes:yy 5 Asymptotes: yy 5 Asymptotes: Asymptotes: y 5 y65x Asíntota: y 5 y62x Asíntota: 5 ± 5x 5 ± 2x Asymptotes: Asymptotes: 2, ±±33dd 2, ±±33dd 59. Vertices: Vertices:ss2, 60. Vertices: Vertices: ss2, 59. 60. 59. 60. s2,±±3d3d s2,±±3d3d 59. Vértice: Vertices:s2, 60. Vértice: Vertices:s2, 0, 55dd 2, ±±55dd Point on on graph: graph:ss0, Foci: ss2, Point Foci: Punto gráfica: Foco: s0, 5ds0, 5d 2, ± ± 55dd Point de on una graph: Foci: ss2, 0, 00dd 0, 00dd 61. Center: Center:ss0, 62. Center: Center: ss0, 61. 62. 61. Centro: 62. Centro: s 0, 0 d s 0, 61. Center: s0, 0d 62. Center: s0,00dd 0, 22dd 6, 00dd Vertex:ss0, Vertex: ss6, Vertex: Vertex: 0, 22dd Vértice: Vértice: 6, 00)d Vertex: ss0, Vertex: s(6, 0, 44dd 10, 00dd Focus:ss0, Focus: ss10, Focus: Focus: s 0, 4 d Foco: Foco: (10, Focus: s0, 4d Focus: s10,0)0d 0, 22dd,, ss6, 6, 22dd 20, 00dd 63. Vertices: Vertices:ss0, 64. Focus: Focus: ss20, 63. 64. 63. 64. 0, 22dd,, ss6, 6,2222dd s20,0)0d 63. Vértices: Vertices:ss0, 64. Foco: Focus:(20, 3 5 5 xx ±344xx Asymptotes:yy2 5 Asymptotes: yy 5 Asymptotes: Asymptotes: 3 ± 3 y22 5 y3x5 323x y 5 y±5 Asíntota: Asíntota: 4x ± x Asymptotes: Asymptotes: 3 4 5 44 2 2233xx yy 5 yy 5 5 44 2 2 32xx 3 In Exercises Exercises 65 65 and and 66, 66, find find equations equations for for (a) (a) the the tangent tangent lines lines In En ejercicios 65 y66, 66,find hallar de las rectasvalue tanIn Exercises 65 and equations for (a) the tangent lines andlos (b) the normal normal lines to the theecuaciones hyperbola fora) the given and (b) the lines to hyperbola for the given value gentes y b) las rectas normales a la hipérbola para el valor dado and (b) the normal lines to the hyperbola for the given value x. of x. of de x. of x. xx22 yy22 xx222 2 yy222 5 5 1, 1, xx 5 5 66 2xx 2 5 5 1, 1, xx 5 5 44 65. xx22 2 66. yy22 2 65. 66. 9 2 9 65. 66. 2 y 5 1, x 5 6 2 222 5 5 1,1, xx 5 5 44 65. 9 2 y 5 1, x 5 6 66. 444 2 9 4 2 In Exercises Exercises 67–76, 67–76, classify classify the the graph graph of of the the equation equation as as aa In En los ejercicios 67 an aan76, clasificar gráfica la ecuación In Exercises 67–76, classify theaala graph ofde the equation como as a circle, parabola, ellipse, or hyperbola. circle, aa parabola, ellipse, or hyperbola. circunferencia, parábola, elipse circle, a parabola, an ellipse, oroahipérbola. hyperbola. 1 4y 4y22 2 2 6x 6x 1 1 16y 16y 1 1 21 21 5 5 00 67. xx22 1 67. 67. 1 4y 4y22 2 2 6x 6x 1 1 16y 16y 1 1 21 21 5 5 00 67. xx22 1 4x22 2 2 yy22 2 2 4x 4x 2 2 33 5 5 00 68. 4x 68. 2 2 2 2 68. 4x 2 2yy 2 24x 4x2 2335 500 68. 4x 2 8y 8y 2 2 8x 8x 5 5 00 69. yy22 2 69. 2 8y 2 8x 5 0 69. y 2 69. 25x22 2 2 10x 10x 2 2 200y 200y 2 2 119 119 5 5 00 70. 25x 70. 22 2 10x 2 200y 2 119 5 0 25x 70. 25x 2 10x 2 200y 2 119 5 70. 2 1 2 2 2 2 4x 4y 16y 1 15 5 0 71. 71. 4x 1 4y 2 16y 1 15 5 0 0 4x221 14y 4y222 2 16y1 1 15 5 0 71. 4x 71. 2 4y 4y 5 5 xx 16y 1 55 15 5 0 72. yy22 2 1 72. 2 y x 1 5 72. 2 222 4y 5 4y9y 522 2 x2136x 5 1 72. 9x21 1 9y 36x 1 6y 6y 1 1 34 34 5 5 00 73. y9x 73. 73. 9x22 1 9y22 2 36x 1 6y 1 34 5 0 2 1 yy6y2 73. 2xssx1 x2 29yyydd 5 5 y36x yss33 2 2 212x 2x34 74. 9x 2x dd 5 0 74. 74. 2xsx 2 y2d2 5 ys3 2 y 2 2x2d2 3 s x 2 1 d 5 6 1 2 s y 1 1 d 75. 3sx 2 1yd 5 5 y6s3122syy212x 1d 75. 2x 74. 75. 3sx 2 1d2222 5 6 1 2s y 1 1d22 22 1133ddd 5 5636 36 2 y2 2 76. 399ssxsxx2 1 5 2 44yssy1 76. 1 2 s 1 d22dd 75. 76. 9sx 1 3d2 5 36 2 4s y 2 2d2 2 76. 9sx 1 3d 5 36 2 4s y 2 2d2 707 707 707 707 WRRIITTIINNGG AABBOOUUTT CCOONNCCEEPPTTSS W Desarrollo W R I T I N G A B Ode U Tconceptos CONCEPTS (a) Give Give the the definition definition of of aa parabola. parabola. (a) a) definición de of parábola. (a) Dar Givelathe definition a parabola. h, kkdd.. (b) Give Givethe thestandard standardforms formsof ofaaparabola parabolawith withvertex vertexat atssh, (b) b) Dar estándar o canónicas de una parábola kd. (b) Givelas theformas standard forms of a parabola with vertex at sh, con (c) In your own words, state the reflective property of aa (c) vértice In yourenown state the reflective property of sh, kwords, d. (c) parabola. In your own words, state the reflective property of a parabola. c) Expresar, con sus propias palabras, la propiedad de reparabola. 78. (a) (a)flexión Give the the definition of an an ellipse. ellipse. 78. Give of dedefinition una parábola. 78. (a) Give the definition of an ellipse. h, kkdd.. (b)Dar Give the standardde forms of an an ellipse ellipse with with center center at atssh, Give standard forms of 78. (b) a) lathe definición elipse. kd. (b) Dar Givelas theformas standard forms ofo an ellipse with center at sh, con b) estándar canónicas de una elipse 79. (a) (a) Give Give the the definition definition of of aa hyperbola. hyperbola. 79. 79. (a) centro Give the of a hyperbola. en definition sstandard h, kd. forms (b) Give Give the the standard forms of of aa hyperbola hyperbola with with center center at at (b) (b) Give the standard forms of a hyperbola with center at 79. a) Dar h, kla kdd..definición de hipérbola. ssh, sh, klas d. formas estándar o canónicas de una hipérbola con b) (c) Dar Write equations equations for for the the asymptotes asymptotes of of aa hyperbola. hyperbola. (c) Write centro sh, kd. for the asymptotes of a hyperbola. (c) Write en equations 80. Define Define the the eccentricity eccentricity of of an an ellipse. ellipse. In In your your own own words, words, 80. c) Dar las ecuaciones deoflasanasíntotas una 80. describe Define eccentricity ellipse. de In affect yourhipérbola. own words, describethe how changes in in the the eccentricity eccentricity affect the ellipse. ellipse. how changes the describelahow changes in the eccentricity affect the ellipse. 80. Definir excentricidad de una elipse. Describir, con sus propias palabras, cómo afectan a la elipse las variaciones en 81. Solar Solar Collector A A solar solar collector collector for for heating heating water water is is la excentricidad. 81. Collector 81. constructed Solar Collector solar collectorsteel for that heating waterinto is constructed with aa A sheet of stainless stainless steel that is formed formed into with sheet of is constructed with a sheet of(see stainless steel thatwater is formed into the shape shape of parabola (see figure). The water flow aa parabola figure). will flow Recolector oofpanel de energía solar UnThe recolector owill panel de 81. the the shape of a parabola (see figure). The water will flow through solar pipepara thatcalentar is located located at the theconstruye focus of of the the parabola. At through aa pipe that is at focus energía agua se conparabola. una hojaAt de through a pipefrom that the is located atthe thepipe? focus of the parabola. At what distance distance from vertex is the pipe? what vertex acero inoxidable en the forma de is parábola (ver la figura). El agua what distance from the vertex is the pipe? fluye a través de un mtubo situado en el foco de la parábola. ¿A 66 m 6m qué distancia del vértice se encuentra el tubo? 77. 77. 77. cm 33 cm 3 cm 6m 16 m m 3 cm 16 16 m m 11 m 1m 1m 16 m Notdrawn drawnto toscale scale Not Not drawn to scale Figure for for 81 81 Figure for for 82 82 Figure Figure Figure for 81 Figure for No 82está dibujado a escala 82. Beam Beam Deflection Deflection A A simply simply supported supported beam beam that that is is 16 16 meters meters 82. FiguraDeflection para 81 A simply supported Figura para 82. long Beam beam82 that figure). is 16 meters long has has aa load load concentrated concentrated at at the the center center (see figure). The (see The long has aof concentrated at viga theis (see figure). The deflection ofload the beam at its itsUna center iscenter centimeters. Assume Deformación de una viga de metros deAssume longitud 82. deflection the beam at center 33 16 centimeters. deflection ofcarga the beam its center is parabolic. 3 centimeters. that the the shape shape of the the deflected beamen is parabolic. soporta una que seatconcentra el centro (ver laAssume figura). that of deflected beam is thatviga the shape of the en deflected beam is parabolic. La se deforma la parte central 3 centímetros. Suponer (a) Find Find an an equation equation of of the the parabola. parabola. (Assume (Assume that that the the origin origin is is (a) que,at deformarse, la forma de una (a) Find an equation ofviga the adquiere parabola.la(Assume that theparábola. origin is atalthe the center of the the beam.) center of beam.) at the center of the beam.) a) de laof (Suponer que el ori(b) Encontrar How far far una fromecuación the center center ofparábola. the beam beam is the the deflection deflection (b) How from the the is está en el centro de la parábola.) (b) gen How far from the center of the beam is the deflection centimeter? 11 centimeter? 1 centimeter? b) ¿A distancia del tangent centro de lato viga de 1 centímetro la 5 ax ax22 at 83. Find Find anqué equation of the the tangent line to thees parabola at yy 5 83. an equation of line the parabola 2 deformación producida? y 5 ax 83. xFind an equation of the tangent line to the parabola at x5 5 xx00.. Prove x-intercept Prove that that the the xintercept of of this this tangent tangent line line is is x00.0una that de thelax-recta intercept of athis tangent yline is2 sxx05 y2, 5 ax 83. sxHallar ecuación tangente la parábola dd..Prove 0y2, sen x0y2, Demostrar quedistinct la intersección estato recta tangente xProve 50dx.0. that 84. (a) (a) Prove that any any two two distinct tangent de lines to parabola 84. tangent lines aa parabola el eje s x y2, 0 d . x es 84. con (a) intersect. Prove that any two distinct tangent lines to a parabola intersect. 0 intersect. que dos rectas tangentes distintas cualesquiera a 84. (b) a) (b) Demostrar Demonstrate the the result result of of part part (a) (a) by by finding finding the the point point Demonstrate sethe cortan o intersecan. (b) una Demonstrate result of part (a)lines by finding point of parábola intersection of the tangent lines to the the the parabola of intersection of the tangent to parabola b) Ilustrar del inciso a)sshallando el de intertangent the x22 2 2intersection 4xel2 2resultado 4y 5 5 0of 0 at 0,lines 6,punto atthe the points andto xof 4x 4y 0, 00dd and ss6, 33dd.. parabola the points sección las 5rectas tangentes a 0lad and parábola x2 2 4x de 2 4y 0 at the s6, 3d. x 2 2 4x 2 points s0, 85. (a) (a) Prove Prove that that ifif any any two two tangent tangent lines lines to to aa parabola parabola intersect intersect at at 85. en los puntos 5 0that stangent 0, 0d y slines 6, 3d.to a parabola intersect at 85. (a) 4y Prove if any twopoint right angles, angles, their point of intersection intersection must must lie lie on on the the right their of 85. a) Demostrar que their si dospoint rectasoftangentes a unamust parábola se corright angles, intersection lie on the directrix. directrix. tan o intersecan en ángulos rectos, su punto de intersección directrix. (b) debe Demonstrate the result of of part part (a) (a) by by proving proving that that the the (b) Demonstrate result estar en lathe directriz. 22 2 (b) tangent Demonstrate thethe result of part (a) by4y proving that the x 2 4x 2 4y 1 8 5 0 tangent lines to the parabola at the x 4x 2 1 8 5 0 lines to parabola at the b) Ilustrar el resultado 55del inciso a) probando que las x 22 2 4x 2 4y angles, 1 8 5 and 0 atthat tangent lines55dto the parabola the 22, d and 3, 454dd intersect pointstangentes and intersect at right right ss22, 3, points rectas a lassparábola los x 2 at 4x 2 4yangles, 1 8 5and 0 enthat s 22, 5 d 3, points and intersect at right angles, and that s d the point point of intersection lies on the the directrix. the of lies on puntos y s3, 54 d 4se cortan endirectrix. ángulo recto y que el s 22, 5intersection d the point of intersection lies on the directrix. punto de intersección se encuentra en la directriz. 10-1.qxd 3/12/09 708 16:44 Page 708 Chapter 10 10Conics, Parametric Equations, and Polar Coordinates CAPÍTULO Cónicas, ecuaciones paramétricas y coordenadas polares 86. point on graph of x 2el punto 8y that is cercano closest to the 86. Find Sobrethe la gráfica dethe más al foco x2 5 8y hallar focus of the parabola. de la parábola. 94. Área Area Hallar Find a una formula for the area of thedeshaded region in the 94. fórmula para el área la región sombreada figure. de la figura. Año 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 A 280 286 291 298 305 307 317 a) Emplear funciones de regresión una herramienta gra(a) Use the las regression capabilities of de a graphing utility todefind 2 1 bt 1 c ficación hallar unAmodelo A5 a modelpara of the form theatdata. Let t bt forma c for at 2 de la para los datos, donde t represente el año y t 5to9 1999. corresponda represent the year, with t 9 corresponding 1999. (b) aUse a graphing utility to plot the data and graph the model. b) Emplear una herramienta de graficación para representar los (c) Find dA dt and sketch its graph for 9 t 15. What datos y la gráfica del modelo. information about the average amount of time women c) Hallar su gráfica # graph t # 15.of ¿Qué dAydt y dibujar spent watching television is givenpara by 9the the información derivative? acerca de la cantidad promedio de tiempo que las mujeres dedicaron a ver televisión proporciona la gráfica 89. Architecture A church window is bounded above by a de la derivada? parabola and below by the arc of a circle (see figure). Find the 89. surface Arquitectura El ventanal area of the window. de una iglesia está limitado en la parte superior por una parábola, y en la parte inferior por el arco ft de una8circunferencia (ver la figura). Hallar el área de la superParabolic ficie del ventanal. supporting cable 4 ft 8 pies Circle 4 pies 8 ft radius Radio 8 pies de la Figure forcircunferencia 89 (60, 20) Cable parabólico y de sujeción x (60, 20) x Figure for 91 90. Arc Length Find the arc length of the parabola 4x Figura 89 para 91 overpara the interval 0 y Figura 4. y2 0 91. Design is la suspended Longitud de arcoA cable Hallaroflaa suspension longitud debridge arco de parábola 90. Bridge (in they 2shape of el a parabola) two towers that are 120 intervalo 0between # y # 4. 4x 2 5 0 en 20 meters abovede theunroadway (see figure). 91. meters Diseñoapart de unand puente El cable puente colgante estáThe suscables touch the roadway midway between the towers. pendido (formando una parábola) de dos torres a 120 metros una (a) for de thealtura parabolic of each cable. de laFind otraany equation a 20 metros sobreshape la autopista. Los cables tocan la autopista en el punto medio entre ambas torres. (b) Find the length of the parabolic supporting cable. a) HallarArea la ecuación para la formareceiving parabólica deiscada cable. 92. Surface A satellite signal dish formed by b) Hallar the la longitud cable de suspensión. revolving paraboladel given byparabólico the y-axis. The x 2 20y about of una the dish is r feet.Un Verify that the area satelital of the 92. radius Área de superficie receptor de surface una antena dish is given se forma porbyrevolución alrededor del eje y de la parábola x2 5r 20y. El radio del2 plato es r pies. Verificar que el área de la x x del 1 plato estádxdada por 100 r 2 3 2 1000 . 2superficie 10 15 0 r x 2 p 2d3y2 2 11000 2p x 1 1Sketch the dx 5 fs100 93. Investigation graphs of x 21 r 4py for p 00014g,. 12, 1, 32, 10 15 0 and 2 on the same coordinate axes. Discuss the change in the 93. graphs Investigación En el mismo eje de coordenadas trazar las gráas p increases. ficas de x 2 5 4py con p 5 14, 12, 1, 32, y 2. Analizar la variación que se presenta en las gráficas a medida que p aumenta. E ! 1 2 y y y 87. Radio anddeTelevision ReceptionEn In areas,la Recepción radio y televisión las mountainous áreas montañosas, reception television suele is sometimes poor. Consider recepción of deradio radioand y televisión ser deficiente. Considean where a en hillelis represented by the of the raridealized un casocase idealizado que la gráfica de graph la parábola parabola a transmitter is punto located at 1)the point x x 2, una colina, en el (21, se localiy 5 x 2 xy2, representa is located otheren side the hill , and a receiver za 1, un1transmisor, y al otro lado deonlathe colina, el of punto (x0, at 0), the point x0, un What is ¿Qué the closest the receiver can puede be to the 0 .receptor. se encuentra tan cerca de la colina ubihill while still maintaining carse el receptor para que launobstructed señal no se reception? obstruya? 88. Modeling Data TheLa table shows the average amounts of time Modelo matemático tabla siguiente muestra las cantidades proA (in minutes) women spent watching each day for thea medio A de tiempo (en minutos) por díatelevision que las mujeres dedicaron years through 2005. (Source: Nielsen Media Research) ver la 1999 televisión de 1999 a 2005. (Fuente: Nielsen Media Research) x 22 = 4py x = 4py 4 1 h h −2 − 1 −2 −1 x x 95. 95. 96. 96. 97. 97. y 4 1 x 1 1 2 2 3 x 3 Figure for 94 Figure for 96 Figura para 94 Figura para 96 Writing On page 699, it was noted that an ellipse can be Redacción página 699 asestring señalóofque se puede una drawn using En twolathumbtacks, fixed length trazar (greater elipse usando dosbetween alfileres,the una cuerda than the distance tacks), anddea longitud pencil. If fija the (mayor ends of a la los dos alfileres) y un extremos thedistancia string areentre fastened at the tacks and thelápiz. stringSiislos drawn taut de la cuerda se sujetan a los alfileres y se tensa la cuerda con el with a pencil, the path traced by the pencil will be an ellipse. lápiz, la trayectoria que recorre el lápiz es una elipse. (a) What is the length of the string in terms of a? a) ¿Cuál es la longitud de la cuerda en términos de a? (b) Explain why the path is an ellipse. b) Explicar por qué la trayectoria trazada por el lápiz es una Construction of a Semielliptical Arch A fireplace arch is to be elipse. constructed in the shape of a semiellipse. The opening is to have Construcción de un semielíptico Se va arco a height of 2 feet at arco the center and a width of a5 construir feet alongelthe de una chimenea en forma de una semielipse. El claro debe tener base (see figure). The contractor draws the outline of the ellipse 2bypies alturashown en el centro y 5 pies de ancho en lathe base (ver the de method in Exercise 95. Where should tacks bela figura). El constructor el perfil de la elipse siguiendo el placed and what shouldbosqueja be the length of the piece of string? método mostrado en el ejercicio 95. ¿Dónde deben colocarse los Sketch the ellipse that consists of all points x, y such that the alfileres y cuál debe ser la longitud del trozo de cuerda? sum of the distances between x, y and two fixed points is Trazar la elipse consta de todos 16 units, and theque foci are located at los the puntos centers(x, of y) thetales two que setsla suma de las distancias entre (x, y) y dos puntos fijos es 16 unidaof concentric circles in the figure. To print an enlarged copy of des, y los focos localizan los centros de los dos conjuntos de the graph, go tosethe websiteenwww.mathgraphs.com. circunferencias concéntricas que se muestran en la figura. 16 17 14 15 17 12 13 16 11 15 9 10 13 14 8 12 7 10 11 5 6 8 9 3 4 6 7 1 2 5 2 1 3 4 4 3 1 2 1 6 5 2 7 3 9 8 5 4 10 6 11 7 13 12 9 8 15 14 11 10 12 17 16 13 15 14 17 16 98. Orbit of Earth Earth moves in an elliptical orbit with the at one the foci. La TheTierra length half of is 98. sun Órbita de of la Tierra seof mueve enthe unamajor órbitaaxis elíptica 149,598,000 theLa eccentricity Findeje con el Sol enkilometers, uno de los and focos. longitud deis la0.0167. mitad del the minimum maximum es distance mayor es 149distance 598 000(perihelion) kilómetros yand la the excentricidad 0.0167. (aphelion) of Earth from the sun. Hallar la distancia mínima (perihelio) y la distancia máxima (afelio) entre Tierra y el Sol. 99. Satellite Orbit la The apogee (the point in orbit farthest from the satélite perigee (the point in(elorbit closest to Earth) 99. Earth) Órbitaand de un El apogeo punto de la órbita másoflean elliptical orbityofel an Earth(el satellite A and P. jano a la Tierra) perigeo punto are de lagiven órbitabymás cercano Show that thedeeccentricity of thede orbit a la Tierra) la órbita elíptica un is satélite de la Tierra están dados por A y P. Mostrar que la excentricidad de la órbita es A P e A 2 P. e 5A P . A1P 100. Explorer 18 On November 27, 1963, the United States satellite Explorer 18. Its Estados low andUnidos high 100. launched Explorerthe 18 research El 27 de noviembre de 1963, points the surface ofpuntos Earth were miles and lanzó above el Explorer 18. Sus bajo 119 y alto sobre la 123,000 superficie miles. eccentricity of its yelliptical de la Find Tierrathefueron 119 millas 123 000orbit. millas, respectivamente. Hallar la excentricidad de su órbita elíptica. 1059997_1001.qxp 9/2/08 3:49 PM Page 709 10-1.qxd 3/12/09 16:44 Page 709 SECCIÓN Cónicas y cálculo 10.110.1Conics and Calculus 101. de noviembre 1975, 101. Explorer Explorer 55 55 ElOn20November 20, de 1975, theEstados United Unidos States lanzó el satélite de investigación Explorer55. 55.Its Suslow puntos bajo launched the research satellite Explorer and high ypoints alto sobre superficie Tierra fueron de 96and millas y abovelathe surface de of la Earth were 96 miles 1865 1miles. 865 millas. Encontrar la excentricidad de su órbita elíptica. Find the eccentricity of its elliptical orbit. Para C A P S Tdiscusión ONE 102. Considerar Consider the equation 102. la ecuación 9x2 1 4y2 2 36x 2 24y 2 36 5 0. a) la graph gráfica ecuación círculo, (a)Clasificar Classify the of de the la equation as acomo circle,un a parabola, una parábola, elipse o una hipérbola. an ellipse, or una a hyperbola. 2-term in 2 Classify b) el 4y término 4y2theenequation la ecuación (b)Cambiar Change the to 24ypor . 24y2. Clasificar la gráfica de la nueva ecuación. the graph of the new equation. c) 9x2in enthe la ecuación 9x2-term (c)Cambiar Change elthetérmino original original equationpor to 4x22. Clasificar la gráfica de the la nueva ecuación. Classify the graph of new equation. d) se podría cambiar ecua(d)Describir Describeuna onemanera way en youquecould change the la original ción original quegraph su gráfica fuera una parábola. equation so para that its is a parabola. 103. El cometa Halley Quizás el más conocido de todos los come103. tas, Halley’s Comet Probably mostelíptica famous el cometa Halley, tiene unathe órbita conofelall Solcomets, en uno Halley’s comet, has an elliptical orbit with the sun de sus focos. Se estima que su distancia máxima al Solatesone de focus.UA Its (unidad maximum distance from the sun is 6approximately 35.29 astronómica millas) y que < 92.956 3 10 35.29 AU (1 astronomical unitUA. 3 excentricidad 106 miles), and < 92.956 su distancia mínima es de 0.59 Hallar la de its minimum distance is approximately 0.59 AU. Find the la órbita. eccentricity of the orbit. 104. La ecuación de una elipse con centro en el origen puede ex104. presarse The equation of an ellipse with its center at the origin can be written as 2 y x2 1 5 1. y 2 e 2d ax22 a 2s1 2 1 2 5 1. 2 2 a a que s1 2cuando e d e → 0, y a permanece constante, la elipMostrar seShow se aproxima that as ae una → circunferencia. 0, with a remaining fixed, the ellipse 709 709 2 Área y volumen 108. 9x 1 4y 2 1En 36xlos 2ejercicios 24y 1 36 109 5 0y 110, hallar a) el área de la región limitada por la elipse, b) el volumen y el área de la superficie del sólidoIngenerado de (a) la región alreArea and Volume Exercisespor 109revolución and 110, find the area of dedor de subounded eje mayor y c) el volumen y el the region by (esferoide the ellipse,prolato), (b) the volume and surface área la superficie del sólido generado the por region revolución la area de of the solid generated by revolving aboutdeits región de su eje menor (esferoide oblato).and surface major alrededor axis (prolate spheroid), and (c) the volume area of2 the 2solid generated by revolving the region about its y minorx axis 109. 1 (oblate 5 1 spheroid). 4 1 x2 x 22 yy22 y2 109. 110. 1 1 51 110. 11 5 5 11 4 16 9 16 9 111. Longitud de arco Usar las funciones de integración de una 111. Arc Length Use the integration capabilities of a graphing herramienta de graficación para aproximar, con una precisión utility to approximate to two-decimal-place accuracy the de dos cifras decimales, la integral elíptica que representa el elliptical integral representing the circumference of the ellipse perímetro de la elipse y 22 x 22 1 5 1. 25 49 112. el teorema10.4 10.4bymostrando que la tangente a una 112. Probar Prove Theorem showing that therecta tangent line to an elipse puntoPP makes forma ángulos iguales conlines las rectas a traellipseenatun a point equal angles with through P vés y de(see los figure). focos (ver la figura). [Sugerencia: enconand de thePfoci [Hint: (1) Find the slope of1)the tantrar pendiente de find la recta P,lines 2) encontrar tangentlaline at P, (2) the tangente slopes ofenthe through las P and gentes de las rectas a través de P y cada uno de los focos y 3) each focus, and (3) use the formula for the tangent of the angle usar la fórmula de la tangente del ángulo entre dos rectas.] between two lines.] yy yy xx22 yy22 + =1 aa22 + bb22 = 1 Recta Tangent tangente line ββ (x0,,yy0)) PP==(x 0 0 (−a, (−a, 0) 0) (0, (0, 10) 10) (a, (a, 0) 0) αα xx x (−(−c, c, 0)0) (c,(c,0)0) (0, (0, −10) −10) approachesuna a circle. 105. Considerar partícula que se mueve en el sentido de las reloj siguiendo la trayectoria elíptica 105. manecillas Consider adel particle traveling clockwise on the elliptical path x22 y2 x 1 y2 5 1. 100 125 5 1. 100 25 La partícula abandona la órbita en el punto s28, 3d y viaja a lo The particle leavestangente the orbitaatlathe point¿En and travels in s28, 3d punto largo de una recta elipse. qué cruzará straight line to the ellipse. At what point will the laa partícula el ejetangent y? particle cross the y- axis? 106. Volumen El tanque de agua de un carro de bomberos mide 16 106. pies Volume They water tank on atransversales fire truck is 16 feet long, and its de largo, sus secciones son elipses. Hallar sections are ellipses. volume of water in the elcross volumen de agua que hay Find en el the tanque cuando está parcialpartially filled tank shownen in la thefigura. figure. mente lleno como seas muestra Figura 112 Figure para for 112 El área elipse presentada en laisfigura 113. 113. Geometría Geometry The areadeoflathe ellipse in the figure twiceestheel doble del What círculo. longitud tiene el eje mayor? area ofdel theárea circle. is ¿Qué the length of the major axis? 114. 114. Conjetura Conjecture a) quethe la ecuación elipse puede (a) Mostrar Show that equationde ofuna an ellipse can beexpresarse written ascomo 2 2 ssxx 2 2 hhdd2 1 ss yy 2 2 kkdd2 5 1. 1 2 2 2 5 1. aa 2 aa 2ss11 2 2 ee 2dd 5 pies 3 pies 9 pies In Exercises 107 and 108, determine the points at which dy/dx is En losorejercicios determinar los puntos los and que zero does not 107 existyto108, locate the endpoints of the en major dy/dx es cero, o no existe, para localizar los extremos de los ejes minor axes of the ellipse. mayor y menor de la elipse. 107. 16x 2 1 9y 2 1 96x 1 36y 1 36 5 0 107. 16x 2 1 9y 2 1 96x 1 36y 1 36 5 0 108. 9x 2 1 4y 2 1 36x 2 24y 1 36 5 0 Figura 113 Figure para for 113 115. 115. 116. 116. b) una herramienta de graficación, (b) Mediante Use a graphing utility to graph the ellipse representar la elipse sx 2 2d2 s y 2 3d2 2 5 1 sx 24 2d2 1 4ssy1 2 2 3ed2d 5 1 1 2 4 4s1 2 e d for e 5 0.95, e 5 0.75, e 5 0.5, e 5 0.25, and e 5 0. para e 5 0.95, e 5 0.75, e 5 0.5, e 5 0.25,y e 5 0. (c) Use the results of part (b) to make a conjecture about the c) Usar los in resultados inciso b) para una conjetura change the shapedel of the ellipse as e hacer approaches 0. acerca de la variación en la forma de la elipse a medida que Find an equation of the hyperbola such that for any point on e se aproxima a 0. the hyperbola, the difference between its distances from the Hallar tal que, para todo punto, points suna and s10, de is hipérbola 6. 2, 2decuación 2d la la diferencia entre sus distancias a los puntos (2, 2) y (10, 2) Find an equation of the hyperbola such that for any point on sea 6. the hyperbola, the difference between its distances from the Hallar de la3hipérbola points suna 23,ecuación 0d and s23, d is 2. tal que, para todo punto, la diferencia entre sus distancias a los puntos (23, 0) y (23, 3) sea 2. 10-1.qxd 3/12/09 710 16:44 Page 710 CAPÍTULO 10 Cónicas, ecuaciones paramétricas y coordenadas polares 117. Dibujar la hipérbola que consta de todos los puntos (x, y) tales que la diferencia de las distancias entre (x, y) y dos puntos fijos sea 10 unidades, y los focos se localicen en los centros de los dos conjuntos de circunferencias concéntricas de la figura. 9 7 8 5 6 4 3 1 2 17 16 15 14 13 12 10 11 13 14 15 16 17 x2 y2 2 251 2 a b en el punto sx0, y0d es sx0ya 2dx 2 s y0yb2dy 5 1. 122. Mostrar que la ecuación de la recta tangente a 2 1 4 3 6 5 7 8 10 9 12 11 123. Mostrar que las gráficas de las ecuaciones se cortan en ángulos rectos: 2y 2 x2 51 2 1 a b2 118. Considerar una hipérbola centrada en el origen y con eje transversal horizontal. Emplear la definición de hipérbola para obtener su forma canónica o estándar: x2 a2 2 2 y 5 1. b2 x2 2 s c2 vm2 y2 51 2 vs2 dyvm2 donde vm es la velocidad inicial de la bala y vs es la velocidad del sonido, la cual es aproximadamente 1 100 pies por segundo. 120. Navegación El sistema LORAN (long distance radio navigation) para aviones y barcos usa pulsos sincronizados emitidos por estaciones de transmisión muy alejadas una de la otra. Estos pulsos viajan a la velocidad de la luz (186 000 millas por segundo). La diferencia en los tiempos de llegada de estos pulsos a un avión o a un barco es constante en una hipérbola que tiene como focos las estaciones transmisoras. Suponer que las dos estaciones, separadas a 300 millas una de la otra, están situadas en el sistema de coordenadas rectangulares en s2150, 0d y s150, 0d y que un barco sigue la trayectoria que describen las coordenadas sx, 75d. (Ver la figura.) Hallar la coordenada x de la posición del barco si la diferencia de tiempo entre los pulsos de las estaciones transmisoras es 1 000 microsegundos (0.001 segundo). y 10 8 6 4 75 Espejo x 75 −75 −150 Figura para 120 150 x −10 −4 2y 2 x2 5 1. 2 2 a 2b b2 2 124. Demostrar que la gráfica de la ecuación Ax 2 1 Cy 2 1 Dx 1 Ey 1 F 5 0 es una de las siguientes cónicas (excepto en los casos degenerados). Condición a) Círculo A5C b) Parábola A 5 0 o C 5 0 (pero no ambas) c) Elipse AC > 0 d) Hipérbola AC < 0 ¿Verdadero o falso? En los ejercicios 125 a 130, determinar si la afirmación es verdadera o falsa. Si es falsa, explicar por qué o dar un ejemplo que demuestre que es falsa. 125. Es posible que una parábola corte a su directriz. 126. En una parábola, el punto más cercano al foco es el vértice. 127. Si C es el perímetro de la elipse y2 x2 1 2 5 1, b < a 2 a b entonces 2pb ≤ C ≤ 2pa. 128. Si D Þ 0 o E Þ 0, entonces la gráfica de y2 2 x2 1 Dx 1 Ey 5 0 es una hipérbola. 129. Si las asíntotas de la hipérbola sx 2ya 2d 2 s y 2yb2d 5 1 se cortan o intersecan en ángulos rectos, entonces a 5 b. 130. Toda recta tangente a una hipérbola sólo corta o interseca a la hipérbola en el punto de tangencia. Preparación del examen Putnam y 150 −150 y Cónica 119. Localización del sonido Con un rifle posicionado en el punto s2c, 0d se dispara al blanco que se encuentra en el punto sc, 0d. Una persona escucha al mismo tiempo el disparo del rifle y el impacto de la bala en el blanco. Demostrar que la persona se encuentra en una de las ramas de la hipérbola dada por c 2 vs2yvm2 121. Espejo hiperbólico Un espejo hiperbólico (como los que usan algunos telescopios) tiene la propiedad de que un rayo de luz dirigido a uno de los focos se refleja al otro foco. El espejo que muestra la figura se describe mediante la ecuación sx 2y36d 2 s y 2y64d 5 1. ¿En qué punto del espejo se reflejará la luz procedente del punto (0, 10) al otro foco? 2 4 −4 −6 −8 −10 Figura para 121 8 10 131. Dado un punto P de una elipse, sea d la distancia del centro de la elipse a la recta tangente a la elipse en P. Demostrar que sPF1dsPF2dd 2 es constante mientras P varía en la elipse, donde PF1 y PF2 son las distancias de P a los focos F1 y F2 de la elipse. 9 2 132. Hallar el valor mínimo de su 2 vd2 1 !2 2 u2 2 v con 0 < u < !2 y v > 0. 1 2 Estos problemas fueron preparados por el Committee on the Putnam Prize Competition. © The Mathematical Association of America. Todos los derechos reservados. 10-2.qxd 3/12/09 16:45 Page 711 SECCIÓN 10.2 SECCIÓN 10.2 Curvas planas y ecuaciones paramétricas Curvas planas y ecuaciones paramétricas 711 711 10.2 Curvas planas y ecuaciones paramétricas n n n n Trazar la gráfica de una curva dada por un conjunto de ecuaciones paramétricas. Eliminar el parámetro en un conjunto de ecuaciones paramétricas. Hallar un conjunto de ecuaciones paramétricas para representar una curva. Entender dos problemas clásicos del cálculo: el problema de la tautocrona y el problema de la braquistocrona. Curvas planas y ecuaciones paramétricas Hasta ahora, se ha representado una gráfica mediante una sola ecuación con dos variables. En esta sección se estudiarán situaciones en las que se emplean tres variables para representar una curva en el plano. Considérese la trayectoria que recorre un objeto lanzado al aire con un ángulo de 45°. Si la velocidad inicial del objeto es 48 pies por segundo, el objeto recorre la trayectoria parabólica dada por Ecuación rectangular: x2 + x y = − 72 y 24 2, 24 2 − 16 18 t=1 9 (0, 0) t=0 x 9 y52 18 27 36 45 54 63 72 Ecuaciones paramétricas: x = 24 2t y = −16t2 + 24 2t Movimiento curvilíneo: dos variables de posición y una de tiempo x2 1x 72 Ecuación rectangular. como se muestra en la figura 10.19. Sin embargo, esta ecuación no proporciona toda la información. Si bien dice dónde se encuentra el objeto, no dice cuándo se encuentra en un punto dado (x, y). Para determinar este instante, se introduce una tercera variable t, conocida como parámetro. Expresando x y y como funciones de t, se obtienen las ecuaciones paramétricas Figura 10.19 x 5 24!2 t Ecuación paramétrica para x. y 5 216t 2 1 24!2 t. Ecuación paramétrica para y. y A partir de este conjunto de ecuaciones, se puede determinar que en el instante t 5 0, el objeto se encuentra en el punto (0, 0). De manera semejante, en el instante t 5 1, el objeto está en el punto s24!2, 24!2 2 16d, y así sucesivamente. (Más adelante, en la sección 12.3, se estudiará un método para determinar este conjunto particular de ecuaciones paramétricas, las ecuaciones de movimiento.) En este problema particular de movimiento, x y y son funciones continuas de t, y a la trayectoria resultante se le conoce como curva plana. DEFINICIÓN DE UNA CURVA PLANA Si f y g son funciones continuas de t en un intervalo I, entonces a las ecuaciones x 5 f std y y 5 gstd se les llama ecuaciones paramétricas y a t se le llama el parámetro. Al conjunto de puntos (x, y) que se obtiene cuando t varía sobre el intervalo I se le llama la gráfica de las ecuaciones paramétricas. A las ecuaciones paramétricas y a la gráfica, juntas, es a lo que se llama una curva plana, que se denota por C. NOTA Algunas veces es importante distinguir entre una gráfica (conjunto de puntos) y una curva (los puntos junto con las ecuaciones paramétricas que los definen). Cuando sea importante hacer esta distinción, se hará de manera explícita. Cuando no sea importante se empleará C para representar la gráfica o la curva, indistintamente. n 10-2.qxd 3/12/09 712 16:45 Page 712 CAPÍTULO 10 Cónicas, ecuaciones paramétricas y coordenadas polares Cuando se dibuja (a mano) una curva dada por un conjunto de ecuaciones paramétricas, se trazan puntos en el plano xy. Cada conjunto de coordenadas (x, y) está determinado por un valor elegido para el parámetro t. Al trazar los puntos resultantes de valores crecientes de t, la curva se va trazando en una dirección específica. A esto se le llama la orientación de la curva. EJEMPLO 1 Trazado de una curva Trazar la curva dada por las ecuaciones paramétricas t y5 , 2 x 5 t2 2 4 y 22 ≤ t ≤ 3. Solución Para valores de t en el intervalo dado, se obtienen, a partir de las ecuaciones paramétricas, los puntos (x, y) que se muestran en la tabla. y 4 2 t=1 t=3 t=2 x t=0 t = −1 4 t = −2 t 22 21 0 1 2 3 x 0 23 24 23 0 5 y 21 22 0 1 2 1 3 2 6 −2 1 −4 Ecuaciones paramétricas: x = t2 − 4 y y = t , −2 ≤ t ≤ 3 2 Al trazar estos puntos en orden de valores crecientes de t y usando la continuidad de f y de g se obtiene la curva C que se muestra en la figura 10.20. Hay que observar las flechas sobre la curva que indican su orientación conforme t aumenta de 22 a 3. Figura 10.20 y NOTA De acuerdo con el criterio de la recta vertical, puede verse que la gráfica mostrada en la figura 10.20 no define y en función de x. Esto pone de manifiesto una ventaja de las ecuaciones paramétricas: pueden emplearse para representar gráficas más generales que las gráficas de funciones. n 4 t= 1 2 2 t=1 t= 3 2 x t=0 1 t=− 2 t = −1 4 A menudo ocurre que dos conjuntos distintos de ecuaciones paramétricas tienen la misma gráfica. Por ejemplo, el conjunto de ecuaciones paramétricas 6 −2 −4 x 5 4t 2 2 4 y Ecuaciones paramétricas: y 5 t, 21 ≤ t ≤ 3 3 2 x = 4t2 − 4 y y = t, −1 ≤ t ≤ 2 Figura 10.21 tiene la misma gráfica que el conjunto dado en el ejemplo 1 (ver la figura 10.21). Sin embargo, al comparar los valores de t en las figuras 10.20 y 10.21, se ve que la segunda gráfica se traza con mayor rapidez (considerando t como tiempo) que la primera gráfica. Por tanto, en las aplicaciones, pueden emplearse distintas ecuaciones paramétricas para representar las diversas velocidades a las que los objetos recorren una trayectoria determinada. La mayoría de las herramientas de graficación cuenta con un modo paramétrico de graficación. Se puede emplear uno de estos dispositivos para confirmar las gráficas mostradas en las figuras 10.20 y 10.21. ¿Representa la curva dada por TECNOLOGÍA x 5 4t 2 2 8t y y 5 1 2 t, 2 12 ≤ t ≤ 2 la misma gráfica que la mostrada en las figuras 10.20 y 10.21? ¿Qué se observa respecto a la orientación de esta curva? 10-2.qxd 3/12/09 16:45 Page 713 SECCIÓN 10.2 Curvas planas y ecuaciones paramétricas 713 Eliminación del parámetro A encontrar la ecuación rectangular que representa la gráfica de un conjunto de ecuaciones paramétricas se le llama eliminación del parámetro. Por ejemplo, el parámetro del conjunto de ecuaciones paramétricas del ejemplo 1 se puede eliminar como sigue. Despejar t de una de las ecuaciones Ecuaciones paramétricas x 5 t2 2 4 y 5 ty2 Sustituir en la otra ecuación x 5 s2yd 2 2 4 t 5 2y Ecuación rectangular x 5 4y 2 2 4 Una vez eliminado el parámetro, se ve que la ecuación x 5 4y 2 2 4 representa una parábola con un eje horizontal y vértice en s24, 0d, como se ilustra en la figura 10.20. El rango de x y y implicado por las ecuaciones paramétricas puede alterarse al pasar a la forma rectangular. En esos casos, el dominio de la ecuación rectangular debe ajustarse de manera que su gráfica coincida con la gráfica de las ecuaciones paramétricas. En el ejemplo siguiente se muestra esta situación. EJEMPLO 2 Ajustar el dominio después de la eliminación del parámetro Dibujar la curva representada por las ecuaciones y x5 1 t=3 t=0 −2 1 −1 x 1 !t 1 1 y y5 t , t > 21 t11 eliminando el parámetro y ajustando el dominio de la ecuación rectangular resultante. 2 Solución Para empezar se despeja t de una de las ecuaciones paramétricas. Por ejemplo, se puede despejar t de la primera ecuación. −1 −2 1 !t 1 1 1 2 x 5 t11 1 t115 2 x 1 1 2 x2 t5 2215 x x2 x5 t = −0.75 −3 Ecuaciones paramétricas: x = 1 , y = t , t > −1 t+1 t+1 y x 1 −1 2 −2 −3 Ecuación rectangular: Figura 10.22 Despejar t. y5 t t11 Ecuación paramétrica para y. y5 (1 2 x2)yx2 [(1 2 x2)yx2] 1 1 Sustitución de t por s1 2 x 2dyx 2. −1 y = 1 − x2, x > 0 Elevar al cuadrado cada lado. Sustituyendo ahora, en la ecuación paramétrica para y, se obtiene 1 −2 Ecuación paramétrica para x. y 5 1 2 x 2. Simplificar. La ecuación rectangular, y 5 1 2 x 2, está definida para todos los valores de x. Sin embargo, en la ecuación paramétrica para x se ve que la curva sólo está definida para t > 21. Esto implica que el dominio de x debe restringirse a valores positivos, como se ilustra en la figura 10.22. 10-2.qxd 3/12/09 714 16:45 Page 714 CAPÍTULO 10 Cónicas, ecuaciones paramétricas y coordenadas polares En un conjunto de ecuaciones paramétricas, el parámetro no necesariamente representa el tiempo. El siguiente ejemplo emplea un ángulo como parámetro. Emplear trigonometría para eliminar un parámetro EJEMPLO 3 Dibujar la curva representada por x 5 3 cos u y y 5 4 sen sin u, 0 # u # 2p al eliminar el parámetro y hallar la ecuación rectangular correspondiente. y π θ =2 Solución Para empezar se despejan cos u y sen u de las ecuaciones dadas. 3 cos u 5 2 1 θ =π −4 θ=0 −2 1 −1 2 4 x x 3 y sen u 5 y 4 Despejar cos u y sen u. sin 2 u 1 cos 2 u 5 1 para formar una ecuación A continuación, se hace uso de la identidad sen en la que sólo aparezcan x y y. −1 cos2 u 1 sen sin2 u 5 1 −2 3π θ= 2 Ecuaciones paramétricas: x = 3 cos θ , y = 4 sen θ Ecuación rectangular: x2 y2 + =1 9 16 Figura 10.23 13x2 1 14y2 2 −3 2 Identidad trigonométrica. 51 Sustituir. x2 y2 1 51 9 16 Ecuación rectangular. En esta ecuación rectangular, puede verse que la gráfica es una elipse centrada en s0, 0d, con vértices en s0, 4d y s0, 24d y eje menor de longitud 2b 5 6, como se muestra en la figura 10.23. Obsérvese que la elipse está trazada en sentido contrario al de las manecillas del reloj ya que u va de 0 a 2p . El empleo de la técnica presentada en el ejemplo 3 permite concluir que la gráfica de las ecuaciones paramétricas x 5 h 1 a cos u y y 5 k 1 b sen sin u, 0 # u # 2p es una elipse (trazada en sentido contrario al de las manecillas del reloj) dada por sx 2 hd 2 s y 2 kd 2 1 5 1. a2 b2 La gráfica de las ecuaciones paramétricas x 5 h 1 a sen sin u y y 5 k 1 b cos u, 0 # u # 2p también es una elipse (trazada en sentido de las manecillas del reloj) dada por sx 2 hd 2 s y 2 kd 2 1 5 1. a2 b2 Emplear una herramienta de graficación en modo paramétrico para elaborar las gráficas de varias elipses. En los ejemplos 2 y 3 es importante notar que la eliminación del parámetro es principalmente una ayuda para trazar la curva. Si las ecuaciones paramétricas representan la trayectoria de un objeto en movimiento, la gráfica sola no es suficiente para describir el movimiento del objeto. Se necesitan las ecuaciones paramétricas que informan sobre la posición, dirección y velocidad, en un instante determinado. 10-2.qxd 3/12/09 16:45 Page 715 SECCIÓN 10.2 Curvas planas y ecuaciones paramétricas 715 Hallar ecuaciones paramétricas Los primeros tres ejemplos de esta sección ilustran técnicas para dibujar la gráfica que representa un conjunto de ecuaciones paramétricas. Ahora se investigará el problema inverso. ¿Cómo determinar un conjunto de ecuaciones paramétricas para una gráfica o una descripción física dada? Por el ejemplo 1 ya se sabe que tal representación no es única. Esto se demuestra más ampliamente en el ejemplo siguiente, en el que se encuentran dos representaciones paramétricas diferentes para una gráfica dada. Hallar las ecuaciones paramétricas para una gráfica dada EJEMPLO 4 Hallar un conjunto de ecuaciones paramétricas para representar la gráfica de y 5 1 2 x 2, usando cada uno de los parámetros siguientes. a) t 5 x b) La pendiente m 5 dy en el punto sx, yd dx Solución a) Haciendo x 5 t se obtienen las ecuaciones paramétricas x5t y 5 1 2 x 2 5 1 2 t 2. y b) Para expresar x y y en términos del parámetro m, se puede proceder como sigue. dy 5 22x dx m x52 2 m5 y 1 m=0 m=2 m = −2 x −2 −1 m=4 1 Despejar x. Con esto se obtiene una ecuación paramétrica para x. Para obtener una ecuación paramétrica para y, en la ecuación original se sustituye x por 2my2. 2 −1 y 5 1 2 x2 −2 m y512 2 2 2 −3 Derivada de y 5 1 2 x 2. Escribir la ecuación rectangular original. 1 2 m = −4 y512 2 m2 4 Sustitución de x por 2my2. Simplificación. Por tanto, las ecuaciones paramétricas son Ecuación rectangular: y = 1 − x2 Ecuaciones paramétricas: m2 m x=− ,y=1− 4 2 Figura 10.24 x52 m 2 y y512 m2 . 4 En la figura 10.24 obsérvese que la orientación de la curva resultante es de derecha a izquierda, determinada por la dirección de los valores crecientes de la pendiente m. En el inciso a), la curva tenía la orientación opuesta. Para usar de manera eficiente una herramienta de graficación es importante desarrollar la destreza de representar una gráfica mediante un conjunto de ecuaciones paramétricas. La razón es que muchas herramientas de graficación sólo tienen tres modos de graficación: 1) funciones, 2) ecuaciones paramétricas y 3) ecuaciones polares. La mayor parte de las herramientas de graficación no están programadas para elaborar la gráfica de una ecuación general. Supóngase, por ejemplo, que se quiere elaborar la gráfica de la hipérbola x 2 2 y 2 5 1. Para hacer la gráfica de la hipérbola en el modo función, se necesitan dos ecuaciones: y 5 !x 2 2 1 y y 5 2 !x 2 2 1. En el modo paramétrico, la gráfica puede representarse mediante x 5 sec t y y 5 tan t. TECNOLOGÍA 10-2.qxd 3/12/09 716 16:45 Page 716 CAPÍTULO 10 Cónicas, ecuaciones paramétricas y coordenadas polares CICLOIDES Galileo fue el primero en llamar la atención hacia la cicloide, recomendando que se empleara en los arcos de los puentes. En cierta ocasión, Pascal pasó ocho días tratando de resolver muchos de los problemas de las cicloides, problemas como encontrar el área bajo un arco y el volumen del sólido de revolución generado al hacer girar la curva sobre una recta. La cicloide tiene tantas propiedades interesantes y ha generado tantas disputas entre los matemáticos que se le ha llamado “la Helena de la geometría” y “la manzana de la discordia”. EJEMPLO 5 Ecuaciones paramétricas de una cicloide Determinar la curva descrita por un punto P en la circunferencia de un círculo de radio a que rueda a lo largo de una recta en el plano. A estas curvas se les llama cicloides. Solución Sea u el parámetro que mide la rotación del círculo y supóngase que al inicio el punto P 5 sx, yd se encuentra en el origen. Cuando u 5 0, P se encuentra en el origen. Cuando u 5 p, P está en un punto máximo sp a, 2ad. Cuando u 5 2p, P vuelve al eje x en s2p a, 0d. En la figura 10.25 se ve que /APC 5 1808 2 u. Por tanto, AC BD 5 a a AP cos u 5 2coss1808 2 u d 5 2coss/APCd 5 2a sin u 5 sen sins1808 2 u d 5 sen sins/APCd 5 sen lo cual implica que AP 5 2a cos u y BD 5 a sen sin u. PARA MAYOR INFORMACIÓN Para más información acerca de las cicloides, consultar el artículo “The Geometry of Rolling Curves” de John Bloom y Lee Whitt en The American Mathematical Monthly. X 5 au. Además, como Como el círculo rueda a lo largo del eje x, se sabe que OD 5 PD BA 5 DC 5 a, se tiene sen u x 5 OD 2 BD 5 au 2 a sin y 5 BA 1 AP 5 a 2 a cos u. Por tanto, las ecuaciones paramétricas son x 5 asu 2 sen sin u d y y 5 as1 2 cos u d. Cicloide: x = a(θ − sen θ ) y = a(1 − cos θ) y P = (x, y) (3π a, 2a) (π a, 2a) 2a A a θ O C B D πa x (2πa, 0) 3π a (4π a, 0) Figura 10.25 TECNOLOGÍA Algunas herramientas de graficación permiten simular el movimiento de un objeto que se mueve en el plano o en el espacio. Se recomienda usar una de estas herramientas para trazar la trayectoria de la cicloide que se muestra en la figura 10.25. La cicloide de la figura 10.25 tiene esquinas agudas en los valores x 5 2np a. Obsérvese que las derivadas x9su d y y9su d son ambas cero en los puntos en los que u 5 2np. xsu d 5 asu 2 sen sin u d x9su d 5 a 2 a cos u x9s2npd 5 0 ysu d 5 as1 2 cos u d y9su d 5 a sen sin u y9s2npd 5 0 Entre estos puntos, se dice que la cicloide es suave. DEFINICIÓN DE UNA CURVA SUAVE Una curva C representada por x 5 f std y y 5 gstd en un intervalo I se dice que es suave si f9 y g9 son continuas en I y no son simultáneamente 0, excepto posiblemente en los puntos terminales de I. La curva C se dice que es suave a trozos si es suave en todo subintervalo de alguna partición de I. 10-2.qxd 3/12/09 16:45 Page 717 SECCIÓN 10.2 Curvas planas y ecuaciones paramétricas 717 Los problemas de la tautocrona y de la braquistocrona B A C El tiempo que requiere un péndulo para realizar una oscilación completa si parte del punto C es aproximadamente el mismo que si parte del punto A Figura 10.26 El tipo de curva descrito en el ejemplo 5 está relacionado con uno de los más famosos pares de problemas de la historia del cálculo. El primer problema (llamado el problema de la tautocrona) empezó con el descubrimiento de Galileo de que el tiempo requerido para una oscilación completa de un péndulo dado es aproximadamente el mismo ya sea que efectúe un movimiento largo a alta velocidad o un movimiento corto a menor velocidad (ver la figura 10.26). Más tarde, Galileo (1564-1642) comprendió que podía emplear este principio para construir un reloj. Sin embargo, no logró llegar a la mecánica necesaria para construirlo. Christian Huygens (1629-1695) fue el primero en diseñar y construir un modelo que funcionara. En su trabajo con los péndulos, Huygens observó que un péndulo no realiza oscilaciones de longitudes diferentes en exactamente el mismo tiempo. (Esto no afecta al reloj de péndulo porque la longitud del arco circular se mantiene constante dándole al péndulo un ligero impulso cada vez que pasa por su punto más bajo.) Pero al estudiar el problema, Huygens descubrió que una pelotita que rueda hacia atrás y hacia adelante en una cicloide invertida completa cada ciclo en exactamente el mismo tiempo. A The Granger Collection B Una cicloide invertida es la trayectoria descendente que una pelotita rodará en el tiempo más corto Figura 10.27 JAMES BERNOULLI (1654-1705) James Bernoulli, también llamado Jacques, era el hermano mayor de John. Fue uno de los matemáticos consumados de la familia suiza Bernoulli. Los logros matemáticos de James le han dado un lugar prominente en el desarrollo inicial del cálculo. El segundo problema, que fue planteado por John Bernoulli en 1696, es el llamado problema de la braquistocrona (en griego brachys significa corto y cronos significa tiempo). El problema consistía en determinar la trayectoria descendente por la que una partícula se desliza del punto A al punto B en el menor tiempo. Varios matemáticos se abocaron al problema y un año después el problema fue resuelto por Newton, Leibniz, L’Hôpital, John Bernoulli y James Bernoulli. Como se encontró, la solución no es una recta de A a B, sino una cicloide invertida que pasa por los puntos A y B, como se muestra en la figura 10.27. Lo sorprendente de la solución es que una partícula, que parte del reposo en cualquier otro punto C, entre A y B, de la cicloide tarda exactamente el mismo tiempo en llegar a B, como se muestra en la figura 10.28. A C B Una pelotita que parte del punto C tarda el mismo tiempo en llegar al punto B que una que parte del punto A Figura 10.28 PARA MAYOR INFORMACIÓN Para ver una demostración del famoso problema de la braquistocrona, consultar el artículo “A New Minimization Proof for the Brachistochrone” de Gary Lawlor en The American Mathematical Monthly. 1059997_1002.qxp 9/2/08 3:49 PM Page 718 10-2.qxd 3/12/09 16:45 Page 718 1059997_1002.qxp 9/2/08 3:49 PM Page 718 1059997_1002.qxp 9/2/08 3:49 PM Page 718 1059997_1002.qxp 1059997_1002.qxp 9/2/08 9/2/08 3:49 3:49 PM PM Page Page 718 718 718 718 CAPÍTULO Cónicas, ecuaciones paramétricas coordenadas polares Chapter 1010 Conics, Parametric Equations, and yPolar Coordinates 718 718 718 Chapter 10 Conics, Parametric Equations, and Polar Coordinates Chapter Chapter10 10 Conics, Conics,Parametric ParametricEquations, Equations,and andPolar PolarCoordinates Coordinates Ejercicios See www.CalcChat.com for worked-out solutions to odd-numbered exercises. 10.2 10.2 Exercises Exercises See See www.CalcChat.com for worked-out solutions to odd-numbered exercises. 10.2 Exercises See www.CalcChat.com for worked-out worked-out solutions solutions to totoodd-numbered odd-numbered exercises. exercises. www.CalcChat.com for 10.2 Exercises See www.CalcChat.com 10.2 x 3 exercises. 4 cos 25.odd-numbered x 5 !t y yfor5worked-out 13 2 t. solutions 25. 1. Considerar las ecuaciones paramétricas t and y 3 t. 1. Consider the parametric equations x a) Construir una tabla de valores para t 5 0, 1,and 2, and Construct table of values for t x 0, 1, t2, 3, y3 y 4.3 t. 1.(a)Consider theaparametric equations x t y 33 t.t. una 1.1. b) Consider the parametric equations and x in Consider the points parametric equations Trazar los puntos (x, y) generados la tabla yand dibujar x, yof (b)(a) Plot the generated table, a t enthe 0,t and Construct a table values for 1, 2,y 3, andsketch 4. t 0, (a) Construct a table of values for 1, 2, 3, and 4.4. gráfica de lastable ecuaciones paramétricas. Indicar la oriengraph of the parametric equations. Indicate the orientation t 0, (a)(b) Construct a of values for 1, 2, 3, and Plot the points x, y generated in the table, and sketch a tación de points la gráfica. ofgraph the x,x,yy generated (b) the inin the table, of the parametric equations. the sketch orientation (b) Plot Plot thegraph. points generated theIndicate table, and and sketchaa graph of the parametric equations. Indicate the orientation c)(c)Verificar la gráfica elaborada en el inciso b) empleando Use a graphing utility to confirm your graph in part (b).una of the graph. graph of the parametric equations. Indicate the orientation ofofthe graph. herramienta de graficación. the graph. (d)(c)Find rectangular equation by eliminating theinparameter, Usethe a graphing utility to confirm your graph part (b). (c) Use aasketch graphing utility totoconfirm your graph ininpart (b). d) Hallar la ecuación rectangular mediante eliminación del and its graph. Compare the graph in part (b) with the (c)(d) Use graphing utility confirm graph partparameter, (b).paFind the rectangular equation byyour eliminating the rámetro yrectangular dibujar su gráfica. Comparar la gráfica generada en graph of the rectangular equation. (d) Find the equation by eliminating the parameter, andthe sketch its graph. Compare graph in the partparameter, (b) with the (d) Find rectangular equation by the eliminating eland inciso b) its congraph. la gráfica de la the ecuación rectangular. 2 sketch Compare graph in part (b) with the x graph 4 cosin part y with 2 sinthe. 2. Consider theofparametric equations and (b) graph thegraph. rectangular equation. and sketch its Compare the graph the rectangular equation. x 5 4 cos 2 u y y 5 2. Considerar ecuaciones paramétricas graphofoflas theparametric rectangular equation. x 4 cos 2 and y 2 sin . 2. Consider the equations (a) a table of values forx 4 cos 22,2 and, y0, 2ysin . . senConstruct u. 2.2. 2Consider 2 and 4 y 4 2 sin 2 . Considerthe theparametric parametricequations equations x 4 cos , and , 0, sketch Construct a table valuespara for in the table, y .a a)(b)(a) Construir una tabla deyof valores x, Plot the points generated 4 , ,2 , ,0, (a) aatable ofofvalues for y4y . .2 (a) Construct Construct table values for 0, 4orientation 2the 44the 22una a graph of the parametric equations. 2 tabla 4 sketch b) (b) Trazar (x,x,y)y generados en la y dibujar Plotlos thepuntos points generated inIndicate table, and of the graph. x, y (b) Plot the points generated in the table, and sketch gráfica de las ecuaciones paramétricas. Indicar la orientax, y graph the parametric equations. the orientation (b) Plot the of points generated in theIndicate table, and sketch aa graph of the Indicate la gráfica. (c)ción Use graphing utility toequations. confirm your graphthe inorientation part (b). ofdeathe graph. graph of the parametric parametric equations. Indicate the orientation ofofthe graph. thethe graph. c)(d)(c) Verificar gráfica elaborada enbyeleliminating inciso empleando una Find rectangular equation theinparameter, Use alagraphing utility to confirm your b) graph part (b). (c) Use a graphing utility totoconfirm your graph ininpart (b). herramienta and sketch its graficación. graph. the graph in part (b) with (c)(d)Use a graphing utilityCompare confirm graph partparameter, (b). the Find the de rectangular equation byyour eliminating the graph ofrectangular the rectangular equation. (d) Find the equation by eliminating the parameter, d) lasketch ecuación rectangular mediante la in eliminación delthe and its graph. Compare the graph part (b) with (d)Hallar Find the rectangular equation by eliminating the parameter, and sketch its graph. Compare the graph in part (b) yofdibujar suselected gráfica. Comparar la generada 2, 3 the 2 (e)parámetro If graph values were from the interval of thegraph. rectangular equation. and sketch its Compare the graph in gráfica part (b)with with the graph ofofthe rectangular equation. en elIf inciso b)of con la gráfica de lafrom ecuación rectangular. for the table in were part (a), would thethe graph in part 2, (b)3 be2 graph the rectangular equation. (e) values selected interval different? Explain. 2, 22gbe (e) IfIf values were selected interval u enthe py2, y2 e)(e)Si se seleccionaran defrom elthe intervalo for theofof table in valores part (a), would graph fin part 2,33p(b) values were selected from the interval for the table in part (a), would the graph in part (b) be para la del a),would ¿seríathe diferente la part gráfica fordifferent? thetabla tableExplain. in inciso part (a), graph in (b) del be In Exercises 3–20, sketch the curve represented by the different? Explain. inciso b)? Explicar different? Explain.el razonamiento. parametric equations the curve orientation of the curve), In Exercises 3–20, (indicate sketch the represented by the and write the corresponding rectangular equation by In Exercises 3–20, sketch the curve represented by the equations (indicate the orientation of the curve), Inparametric Exercises 3–20, thecurva curve byecuathe En los ejercicios 3 a 20,sketch trazar la querepresented representa las eliminating the parameter. parametric equations (indicate the the and paramétricas write the corresponding rectangular equation parametric equations (indicate the orientation orientation ofcurva) the curve), curve), ciones (indicar la orientación de laof y, eli-by and write the rectangular equation by eliminating the corresponding parameter. and the minando el parámetro, x write 2t 3, ycorresponding 3tdar 1la ecuación x rectangular 5 4t, equation y correspon2 5tby 3. 4.rectangular eliminating the parameter. eliminating the parameter. diente. 5.3.x x t 2t 1, 3,y y t 2 3t 1 6.4.x x 2t52, y4t, t y4 12 5t xx 2t 3, yy2 3t 11 x 5 4t, yy 422 5t 3. 4. 2 2t 3, 3t 3. 5. 4. 3. 4. x 3 t 1, t y t , y t 15t 6.x x 52 2t 24t, 2 2 x 2tt 2222, yt, yt 4444 t 21 t x t , y 7. 8. x x t 1, y t 5. 6. 2 2 2 t 2tt 5.5. xx5 tt1 1,1, yy5 6.6. xx5 2t2t , , yy5 tt 1 11 7. x t 3, y t2222 8. x 4 t 2 t, y t 2 t 3 t, 3 x 22 t, y 8 22 t x y t 5 9. 10. t t 2 x t , y 7. 8. 3 3 7.7. xx5 tt , , yy5 2 8.8. xxx5 ttt221 t,t,t, yyy5 ttt222 ttt 4 t,1 y 2 2 t, y t t 5 8 t 9. x 10. x x t t, 3,y yt 5 11. 12. xx 4414t, y, y8 tt 1 x 9. 10. t, y t t 5 t3 t, t y1 8 t 10. x 9.9. x 10. 11. x t 3, y 12. x 1 1 , y t 1 t 111 t, y t 2 13. x 2t, y y t t2tt 3 14. x 11. 12. 3, y t 3 11. xx tt 3, 12. xxx5 1111 t ,, , yyy5 ttt2 111 11. 12. t 3t t 3 , y y e t 12 15. 16. 13.x x e 2t, 14.x x e tt, tt y1 , ey2t t1 2 x 2t, y t 2 x t 11t1,, , yyy5 tt2tt1 222 13. 14. 2t, 13. 14.16. xxx5x 2t, 22 1, 0 14. 13. sec <xx5x 2,tt2 17. e t,yy, 5y y tt2 e3tcos e , 2 y< e 1 15. 3t3t 2t2t tt,t y 3t tt x e e 1 x e eee2t2t 111 15. 16. t , 2y 3t 2t,t, yy 2 x e e 1 x e 15. 16. x 5 e , y 5 e 1 1 x 5 e , y 5 2 15. 16. 18. cos , 0 < 2, 2 < 17.x x tansec , , y y sec << py2, << u ≤ p xxx5 sec ,, , 2 000 ≤ u < < 2,2, py222 < < 17. sec cos8sec 17. u,, ,2 y,y,y5yycos cos usen 17. x x sec 8 tan cos 19. 18. 222 222 xxx5 tan sec 18. 2 , , yy 2 tan sec 18. ucos , ,y , 5 u sen 18. x x tan 3 8cos y ysec 7 8sen 20. 19. x 8 cos , y 8 sen 19. cos sen 19.20. 19. xx x 88 cos 3 cos,, ,yy y 88 sen 7 sen In Exercises 21–32, a graphing utility to graph the curve , , yy use 77sen 20. cos sen 20. xxx 333cos 20. cosby ,theyparametric 7 sen equations (indicate the orientation represented In Exercises 21–32, use a graphing utility to graph the curve ofrepresented theejercicios curve). Eliminate the parameter and write the In Exercises 21–32, graphing utility toto graph the curve En los ause 32,aausar una herramienta dethe graficación by 21 the parametric equations (indicate orientation In Exercises 21–32, use graphing utility graph the curve corresponding rectangular equation. represented by the parametric equations (indicate the orientation para la que representa ecuaciones paramétricas of trazar the curve). Eliminate the las parameter and write the represented bycurva the parametric equations (indicate the orientation of the curve). Eliminate the parameter write (indicar la orientación de la curva). Eliminar el and parámetro ythe dar corresponding rectangular equation. of the curve). Eliminate the parameter and write , y 4 cosequation. 2 21. x 6 sen 2rectangular 22. x cos , y 2 sen 2 the corresponding lacorresponding ecuación rectangular correspondiente. rectangular equation. 2 cos 2 ,3ycos 2 sen 2 23. 2 , y 4 cos 2 24. 21.x x 4 6 sen 22.x x cos xx 66sen 22 , ,yy 44cos 22 xx cos , y 22sen 21. 22. sen cos cos sen22 21.23. 22. y x 41 2sen 5 2, y3 3sen cos cos 24.y x 23. 24. cossen cos 23. xx y 44 212cos 24. xx y 22 5 33cos 3 sen yy y 5 3 sen 11 sen sen y 5 3 sen | | | | 26. x 5 sec u 26. u x tansec 25.y x 2 35 sen4 cos 26.y 5 xx 33 44cos xx sec 25. 26. 3 3 cos sec 25. 26. 27. x 5 28. x 5 y 5 3 tan u u, y 5 sen sin 33 u 27. 28. y 4 sec 2 u,5 sen y cos tan yy 2233 55sen y tan sen,3 lny t 3 tan 29. 30. y5 ln cos 2t, 3 y, 5y t 22 sin 3 29. 30. x t ,4 sec x tan 27.x 5 28.yx 5 333 , xx 442t sec ,, yy 3t3t 33tan y sin2333 xx cos 27. 28. t 2t 2t 3 sec tan cos 27. 28. , 2t, y, 5yyett sin 31. 32. 31. 32. x e t ,, yy 5 e3 ln t x e ln t 29.x 5 30.x 5 33 xx t t3, , yyt 33lnlnt t3t xx lnln2t, t 222 29. 30. 2t, yy 29.31. 30.32. x e2t, x e , y e y tet 3t 2t –36, determine 3t 2t Comparingtt Plane Curves In Exercises 33 any Comparación de curvas planas En los ejercicios 33tt a 36, deter31. 32. 31. xx ee ,t, yy ee3t 32. xx ee2t,, yy eet differences theentre curves the parametric equations. Are minar toda between diferencia las curvas de 33 las–36, ecuaciones paraComparing Plane Curves InofExercises determine any the graphs¿Son the same? Are the orientations the determine same? the Comparing Plane Curves In Exercises 33 any métricas. iguales lascurves gráficas? iguales las Are orientadifferences between the of the¿Son parametric equations. Are Comparing Plane Curves In Exercises 33–36, –36, determine any curves smooth? differences between the ofofExplicar. the equations. Are ciones? ¿Son suaves lascurves curvas? the graphs theExplain. same? Are the orientations the same? Are differences between the curves theparametric parametric equations. Arethe the graphs the same? Are the orientations the same? Are the curves smooth? Explain. the graphs the same? Are the orientations the same? Are the cosu 33. a) (a) xx5 t t Explain. (b) xx5 cos 33. b) curves curvessmooth? smooth? Explain. t 11 cosu 1 11 33. (a) (b) yy5x 2t2t1 yy5x 22cos xx t t2t t xx cos 33. (b) t cos 33. (a) (a) (b) t (c) xx5y ee 2t 1 (d) xx5y ee 2 cos 1 c) d) y 2t2t2t tt11 yy 22cos 1 t y5x 2e2etcos 2ee 1 11 1 1 et1 (c) (d) yyy5x 2e y 1 x eett t 2t2 (c) xx ee tt t t (d) (d) 4t 2 1y cos 34. (c) (a) xx5y 22cos (b) xxx5y ! 2e 2e u 1 11 t t 34. a) b) 4t tt tt yy 2e yy 2e 1 1 t t 2e 2sen 1 t 4t12 1 t 2sincos 34. (a) (b) yy5x 22e sin u 1 yy5x 1yt x 4t4t222 112t2tt t x 22cos 34. (b) 34. (a) (a) (b) (c) xxx5y ! (d) xxx5y 2 ! 2t sin 1 4t42 ee c) d) tcos y 22sin yy 11t tt t 42t t t x ee 4 e2t (c) (d) yyy5x ! 4sin yy5 xx 44 ee2t2t2t xx tt (c) (d) t (c) (d) cosu 4 t cos 35. a) (a) xx5y cos (b) xx5y cos es2 ud 35. b) yy eett t 2 2 yy 44 2 2 t t sin u sins2 ud cos cos 35. (a) (b) yy5x 22sen sin yy5x 22sen sin xx cos 35. (b) 2 cos cos 35. (a) (a) x0x0<y<cos (b) u <2<2sin p 00<y<u <2<sin p 2 2 22 yy 22sin y 2 sin 2 2 3 2 sin t1<1,1,yy5 s2tdt3 3 36. a) (a) xx50 t<t1sin (b) xyx50 2t <yy5 t3t < 36. b) 1,1, << < << < < < < 0 00 < t3 36. (a) x t 1, y t3 (b)0 x< < t 1, y 37. Conjetura 33 33 37. (a) Conjecture y t x t 1, y t x t 1, 36. (b) 3 3 t t 1, y 36. (a) x t 1, y t (b) x Usar herramienta de graficación paracurves trazar las curvas repre(a)Conjecture Use una a graphing utility to graph the represented by 37.a) 37. sentadas los conjuntos de ecuaciones paramétricas. twoapor sets of dos parametric 37. Conjecture Conjecture (a)theUse graphing utility toequations. graph the curves represented by (a) graphing graph xx the 5aa44two cos tt ofutility xxparametric 5 44to cos s2t cossets cos td the equations. (a) Use Use graphing utility to graph the curves curves represented represented by by the two sets of parametric equations. the two sets of parametric equations. yy 5 3 sin t y 5 3 sin s 2t d sen sen t t y x 3 4sincos t t x 3 4sincos xx 44cos xx en 4 cos t t si se cambia el signo del t cambio cos b) eltthe la gráfica (b) Describir Describe the graph when the sign of the y cos 3 sin t change y 4in 3 sin t yparameter 3 sin t y 3 sin t parámetro. is changed. y 3 sin t y 3 sin t (b) Describe the change in the graph when the sign of the c) conjetura al cambio enthe la gráfica de (b) Describe the in the graph when the sign ofof the (c)Formular Make a una conjecture about change graph of parameter changed. (b) Describe theischange change inrespecto the the graph whenin the sign the las ecuaciones paramétricas cuando se of cambia el signo del parameter isisequations changed. parametric when the sign the parameter parameter changed. (c) Make a conjecture about the change in the graph isof parámetro. changed. (c) aa conjecture about the change inin the the graph parametric equations when sign of (c) Make Make conjecture about thethe change the parameter graph ofof is d) Probar la conjetura con otro conjunto de ecuaciones paraequations when the sign of the parameter (d)parametric Test your conjecture with another set of parametric changed. parametric equations when the sign of the parameter isis métricas. changed. equations. (d)changed. Test your conjecture with another set of parametric (d) Test your conjecture with another 38. Redacción Revisar los ejercicios 33 36 set yset escribir un párrafo 38. (d) Writing Review Exercises 33–36 anda write a of short paragraph equations. Test your conjecture with another of parametric parametric equations. breve que describa cómo las gráficas de curvas representadas describing how the graphs of curves represented by equations. 38. Writing Review Exercises 33–36 and write a short different paragraph por diferentes conjuntos de33–36 ecuaciones paramétricas sets of parametric equations can differ even though 38. Writing Review Exercises and aashort paragraph describing how the graphs of curves represented by pueden different 38. Writing Review Exercises 33–36 andwrite write shorteliminating paragraph diferir aun cuando la eliminación del parámetro dé equation. la misma thesets parameter each yields thediffer same rectangular describing how the ofof curves represented by of parametric equations can even though eliminating describing howfrom the graphs graphs curves represented by different different ecuación rectangular. sets ofofparameter parametric equations can even the each yields the same rectangular equation. sets parametricfrom equations candiffer differ eventhough thougheliminating eliminating In the Exercises 39–42, eliminate the parameter and obtain the parameter the parameter from from each each yields yields the the same same rectangular rectangular equation. equation. standard form of the arectangular equation. En ejercicios 39 42, eliminar elparameter parámetroand y obtener Inlos Exercises 39–42, eliminate the obtain la the In Exercises 39–42, eliminate the parameter and obtain the forma estándar o canónica de la ecuación rectangular. standard form of the rectangular equation. In Exercises 39–42, eliminate the parameter and obtain the x1, y1 and x2, yequation. 39. Line through 2 : standard standardform formofofthe therectangular rectangular equation. x Line x1que tpasa x2 por 39.39.Recta y1d yxys21x, 2y, 2yt2: d:y2 y1 x1x,1syx,11, and through xx11, ,yy11 and xx22, ,yy22 : : 39. Line through 39. through and 1 1 40. Line Circle: x h r cos sin x x t x x , y 2yy1y21 x 5 x1 1 1 t sx2 2 2 x1d,1 y, 5 1 k t s ty2ry2 2 y1dy1 xx xx11 t t xx22 xx11 , , yy yy11 t t yy22 yy11 1 1 41. Ellipse: xx 2hh x 5 arcos y1y u,kk y2 5 br sin 40.Circunferencia: Circle: cos sin 40. h 1 ,r, cos k 11 r sen sin u 40. Circle: xx hh rrcos , , yy kk rrsin 40. Circle: 42. Hyperbola: x h h cos acos sec , , y y k k sin bsin tan 41. Ellipse: x a b 41. Ellipse: Elipse: xx 5 hh 1 aa cos cos u, yy 5 kk 1 bb sin sin u sen 41. 41.42.Ellipse: x hx ahcos a, ,sec y , ky bksin b tan Hyperbola: 42. Hyperbola: Hipérbola: x 5 h 1 a sec u,, yy 5 kk 1 bb tan tan u 42. 42. Hyperbola: xx hh aasec sec , y k b tan || 10-2.qxd 3/12/09 16:45 Page 719 SECCIÓN 10.2 En los ejercicios 43 a 50, emplear los resultados de los ejercicios 39 a 42 para hallar un conjunto de ecuaciones paramétricas para la recta o para la cónica. 43. 44. 45. 46. 47. 48. 49. 50. Desarrollo de conceptos (continuación) y c) Recta: pasa por (0, 0) y (4, 27) Recta: pasa por (1, 4) y (5, 22) Círculo: centro: (3, 1); radio: 2 Círculo: centro: (26, 2); radio: 4 Elipse: vértices (610, 0); foco: (68, 0) Elipse: vértices: (4, 7), s4, 23d; foco: (4, 5), s4, 21d Hipérbola: vértice: s± 4, 0d; foco: s± 5, 0d Hipérbola: vértice: s0, ± 1d; foco: s0, ± 2d 52. y 5 4y(x 2 1) 53. y 5 x3 54. y 5 x2 x 1 2 3 −2 −3 −4 4 y e) y f) 3 2 1 4 x −3 −2 −1 1 1 2 3 x i) x 5 t 2 2 1, 1 −1 −1 −3 2 3 y5t12 ii) x 5 sen u 2 1, y 5 sin sen u 1 2 iii) Curva de Lissajous: x 5 4 cos u, y 5 2 sen sin 2u cos3 u, y 5 2 sen sin33 u v) Evolvente o involuta de un círculo: x 5 cos u 1 u sen sin u, y 5 sen sin u 2 u cos u sen ud, y 5 2s1 2 cos ud 59. Cicloide: x 5 2su 2 sin 60. Cicloide: x 5 u 1 sen sin u, y 5 1 2 cos u 61. Cicloide alargada: x 5 u 2 32 sen sin u, y 5 1 2 32 cos u 62. Cicloide alargada: x 5 2u 2 4 sen sin u, y 5 2 2 4 cos u 63. Hipocicloide: x 5 3 cos3 u, y 5 3 sen sin3 u 64. Cicloide corta: x 5 2u 2 sen sin u, y 5 2 2 cos u 65. Hechicera o bruja de Agnesi: x 5 2 cot u, y 5 2 sen sin2 u y5 3t 2 1 1 t3 sin u cos u vi) Curva serpentina: x 5 cot u,ÊÊ y 5 4 sen 69. Cicloide corta Un disco de radio a rueda a lo largo de una recta sin deslizar. La curva trazada por un punto P que se encuentra a b unidades del centro (b < a) se denomina cicloide corta o acortada (ver la figura). Usar el ángulo u para hallar un conjunto de ecuaciones paramétricas para esta curva. y y 4 2a (π a, a + b) P 3 b θ a x (0, a − b) Desarrollo de conceptos 1 (x, y) θ x 1 67. Explicar el proceso del trazado de una curva plana dada por ecuaciones paramétricas. ¿Qué se entiende por orientación de la curva? 68. Asociar cada conjunto de ecuaciones paramétricas con su gráfica correspondiente. [Las gráficas están etiquetadas a), b), c), d), e) y f).] Explicar el razonamiento. y a) −2 1 2 2 1 x −3 −2 −1 −2 −4 Figura para 69 3 4 Figura para 70 70. Epicicloide Un círculo de radio 1 rueda sobre otro círculo de radio 2. La curva trazada por un punto sobre la circunferencia del círculo más pequeño se llama epicicloide (ver la figura). Usar el ángulo u para hallar un conjunto de ecuaciones paramétricas de esta curva. ¿Verdadero o falso? En los ejercicios 71 a 73, determinar si la afirmación es verdadera o falsa. En caso de que sea falsa, explicar por qué o dar un ejemplo que muestre que es falsa. 4 x −2 −1 y b) 2 4 sin2 iv) Evoluta de una elipse: x 5 En los ejercicios 59 a 66, emplear una herramienta de graficación para representar la curva descrita por las ecuaciones paramétricas. Indicar la dirección de la curva e identificar todos los puntos en los que la curva no sea suave. 3t , 1 1 t3 2 3 −2 x −1 −1 y 5 2x 2 5, t 5 0 en el punto (3, 1) y 5 4x 1 1, t 5 21 en el punto (22, 27) y 5 x2, t 5 4 en el punto (4, 16) y 5 4 2 x2, t 5 1 en el punto (1, 3) 66. Hoja o folio de Descartes: x 5 4 3 2 1 En los ejercicios 55 a 58, encontrar un conjunto de ecuaciones paramétricas para la ecuación rectangular que satisface la condición dada. 51. 56. 57. 58. y d) 4 En los ejercicios 51 a 54, hallar dos conjuntos diferentes de ecuaciones paramétricas para la ecuación rectangular. 51. y 5 6x 2 5 719 Curvas planas y ecuaciones paramétricas 1 2 3 71. La gráfica de las ecuaciones paramétricas x 5 t 2 y y 5 t 2 es la recta y 5 x. 72. Si y es función de t y x es función de t, entonces y es función de x. 10-2.qxd 3/12/09 720 16:45 Page 720 CAPÍTULO 10 Cónicas, ecuaciones paramétricas y coordenadas polares 73. La curva representada por las ecuaciones paramétricas x 5 t y y 5 cos t se pueden escribir como una ecuación de la forma y 5 f(x). PROYECTO DE TRABAJO Para discusión Cicloides 74. Considerar las ecuaciones paramétricas x 5 8 cos t y y 5 8 sen t. En griego, la palabra cycloid significa rueda, la palabra hipocicloide significa bajo la rueda, y la palabra epicicloide significa sobre la rueda. Asociar la hipocicloide o epicicloide con su gráfica. [Las gráficas están marcadas a), b), c), d), e) y f).] a) Describir la curva representada por las ecuaciones paramétricas. b) ¿Cómo se representa la curva por las ecuaciones paramétricas x 5 8 cos t 1 3 y y 5 8 sen t 1 6 comparada a la curva descrita en el inciso a)? Hipocicloide, H(A, B) c) ¿Cómo cambia la curva original cuando el coseno y el seno se intercambian? 1A 2B B2t A2B y 5 sA 2 Bd sen sin t 2 B sen sin1 t B 2 Movimiento de un proyectil En los ejercicios 75 y 76, considerar un proyectil que se lanza a una altura de h pies sobre el suelo y a un ángulo u con la horizontal. Si la velocidad inicial es v0 pies por segundo, la trayectoria del proyectil queda descrita por las ecuaciones paramétricas x 5 xv0 cos uc t y y 5 h 1 xv0 sen sin uc t 2 16t 2. 75. La cerca que delimita el jardín central en un parque de béisbol tiene una altura de 10 pies y se encuentra a 400 pies del plato de home. La pelota es golpeada por el bate a una altura de 3 pies sobre el suelo. La pelota se aleja del bate con un ángulo de u grados con la horizontal a una velocidad de 100 millas por hora (ver la figura). Trayectoria descrita por un punto fijo en un círculo de radio B que rueda a lo largo de la cara interior de un círculo de radio A x 5 sA 2 Bd cos t 1 B cos Epicicloide, E(A, B) Trayectoria descrita por un punto fijo en un círculo de radio B que rueda a lo largo de la cara exterior de un círculo de radio A 1A 1B B2t A1B y 5 sA 1 Bd sen sin t 2 B sen sin1 t B 2 x 5 sA 1 Bd cos t 2 B cos I. H(8, 3) II. E(8, 3) III. H(8, 7) IV. E(24, 3) V. H(24, 7) 10 pies a) VI. E(24, 7) y b) y θ 400 pies x 3 pies a) Dar un conjunto de ecuaciones paramétricas para la trayectoria de la pelota. b) Usar una herramienta de graficación para representar la trayectoria de la pelota si u 5 158. ¿Es el golpe un home run? c) Usar una herramienta de graficación para representar la trayectoria de la pelota si u 5 238. ¿Es el golpe un home run? d) Hallar el ángulo mínimo al cual la pelota debe alejarse del bate si se quiere que el golpe sea un home run. 76. Una ecuación rectangular para la trayectoria de un proyectil es y 5 5 1 x 2 0.005 x 2. c) y x d) y x e) y x f) y a) Eliminar el parámetro t de la función de posición del movimiento de un proyectil para mostrar que la ecuación rectangular es 16 sec22 u 2 x 1 stan ud x 1 h. v02 b) Usar el resultado del inciso a) para hallar h, v0 y u. Hallar las ecuaciones paramétricas de la trayectoria. c) Usar una herramienta de graficación para trazar la gráfica de la ecuación rectangular de la trayectoria del proyectil. Confirmar la respuesta dada en el inciso b) y dibujar la curva representada por las ecuaciones paramétricas. d) Usar una herramienta de graficación para aproximar la altura máxima del proyectil y su rango. y52 x x Ejercicios basados en “Mathematical Discovery via Computer Graphics: Hypocycloids and Epicycloids” de Florence S. Gordon y Sheldon P. Gordon, College Mathematics Journal, noviembre de 1984, p. 441. Uso autorizado por los autores. 10-3.qxd 3/12/09 16:47 Page 721 SECCIÓN 10.3 SECCIÓN 10.3 Ecuaciones paramétricas y cálculo Ecuaciones paramétricas y cálculo 721 721 10.3 Ecuaciones paramétricas y cálculo n n y n Pendiente y rectas tangentes 30 20 Hallar la pendiente de una recta tangente a una curva dada por un conjunto de ecuaciones paramétricas. Hallar la longitud de arco de una curva dada por un conjunto de ecuaciones paramétricas. Hallar el área de una superficie de revolución (forma paramétrica). Ahora que ya se sabe representar una gráfica en el plano mediante un conjunto de ecuaciones paramétricas, lo natural es preguntarse cómo emplear el cálculo para estudiar estas curvas planas. Para empezar, hay que dar otra mirada al proyectil representado por las ecuaciones paramétricas x = 24 2t y = −16t 2 + 24 2t θ 10 x 5 24!2t 45° x 10 20 30 En el momento t, el ángulo de elevación del proyectil es u, la pendiente de la recta tangente en ese punto Figura 10.29 y y 5 216t 2 1 24!2t como se ilustra en la figura 10.29. De lo visto en la sección 10.2, se sabe que estas ecuaciones permiten localizar la posición del proyectil en un instante dado. También se sabe que el objeto es proyectado inicialmente con un ángulo de 45°. Pero, ¿cómo puede encontrarse el ángulo u que representa la dirección del objeto en algún otro instante t? El teorema siguiente responde a esta pregunta proporcionando una fórmula para la pendiente de la recta tangente en función de t. TEOREMA 10.7 FORMA PARAMÉTRICA DE LA DERIVADA Si una curva suave C está dada por las ecuaciones x 5 f std y y 5 g std, entonces la pendiente de C en sx, yd es dy dyydt 5 , dx dxydt y ( f(t + ∆t), g(t + ∆t)) DEMOSTRACIÓN ∆y En la figura 10.30, considérese Dt > 0 y sea Dy 5 gst 1 Dtd 2 gstd y Dx 5 f st 1 Dtd 2 f std. Como Dx → 0 cuando Dt → 0, se puede escribir ( f(t), g(t)) ∆x x La pendiente de la recta secante que pasa por los puntos s f std, g stdd y s f st 1 Dtd, gst 1 Dtdd es Dy yD x. Figura 10.30 dx Þ 0. dt dy Dy 5 lím lim dx Dx →0 Dx gst 1 Dtd 2 gstd 5 lím lim . Dt→0 f st 1 Dtd 2 f std Dividiendo tanto el numerador como el denominador entre Dt, se puede emplear la derivabilidad o diferenciabilidad de f y g para concluir que dy fgst 1 Dtd 2 gstdgyDt 5 lím lim dx Dt→0 f f st 1 Dtd 2 f stdgyDt gxt 1 Dtc 2 gxtc lim lím Dt→0 Dt 5 f xt 1 Dtc 2 f xtc lím lim Dt→0 Dt g9std f9std dyydt . 5 dxydt 5 10-3.qxd 3/12/09 722 16:47 Page 722 CAPÍTULO 10 Cónicas, ecuaciones paramétricas y coordenadas polares Derivación o diferenciación y forma paramétrica EJEMPLO 1 Hallar dyydx para la curva dada por x 5 sin sen tt y y 5 cos t. AYUDA DE ESTUDIO La curva del ejemplo 1 es una circunferencia. Emplear la fórmula dy 5 2tan t dx para hallar su pendiente en los puntos (1, 0) y (0, 1). Solución dy dyydt 2sin sen t 5 5 5 2tan t dx dxydt cos t Como dyydx es función de t, puede emplearse el teorema 10.7 repetidamente para hallar las derivadas de orden superior. Por ejemplo, 3 4 2 d y d dy 5 dx 2 dx dx 3 4 d 3y d d 2y 3 5 dx dx dx 2 3 4 d dy dt dx 5 dxydt d d 2y dt dx 2 5 . dxydt 3 4 Segunda derivada. Tercera derivada. Hallar pendiente y concavidad EJEMPLO 2 Para la curva dada por 1 y 5 st 2 2 4d, t ≥ 0 4 hallar la pendiente y la concavidad en el punto s2, 3d. x 5 !t y Solución Como y (2, 3) 3 t=4 m=8 2 x −1 1 Forma paramétrica de la segunda derivada. En sx, yd 5 s2, 3d, se tiene que t 5 4, y la pendiente es 2 dy 5 s4d 3y2 5 8. dx −1 x= t 1 4 (t 2 − 4) En (2, 3), donde t 5 4, la gráfica es cóncava hacia arriba Figura 10.31 Forma paramétrica de la se puede hallar que la segunda derivada es d d 3y2 fdyydxg ft g d 2y dt dt s3y2d t 1y2 5 5 5 5 3t. dx 2 dxydt dxydt s1y2d t21y2 1 y= dy dyydt s1y2d t 5 5 5 t 3y2 dx dxydt s1y2d t21y2 Y, cuando t 5 4, la segunda derivada es d 2y 5 3s4d 5 12 > 0 dx 2 por lo que puede concluirse que en (2, 3) la gráfica es cóncava hacia arriba, como se muestra en la figura 10.31. Como en las ecuaciones paramétricas x 5 f std y y 5 gstd no se necesita que y esté definida en función de x, puede ocurrir que una curva plana forme un lazo y se corte a sí misma. En esos puntos la curva puede tener más de una recta tangente, como se muestra en el ejemplo siguiente. 10-3.qxd 3/12/09 16:47 Page 723 SECCIÓN 10.3 EJEMPLO 3 x = 2t − π sen t y = 2 − π cos t y Recta tangente (t = π /2) Una curva con dos rectas tangentes en un punto x 5 2t 2 p sen sin t Solución Como x 5 0 y y 5 2 cuando t 5 ± py2, y (0, 2) π dy dyydt p sen sin t 5 5 dx dxydt 2 2 p cos t x se tiene dyydx 5 2 py2 cuando t 5 2 py2 y dyydx 5 py2 cuando t 5 py2. Por tanto, las dos rectas tangentes en (0, 2) son −2 Recta tangente (t = −π /2) y2252 Esta cicloide alargada tiene dos rectas tangentes en el punto (0, 2) Figura 10.32 y 5 2 2 p cos t y se corta a sí misma en el punto (0, 2), como se ilustra en la figura 10.32. Hallar las ecuaciones de las dos rectas tangentes en este punto. 4 −π 723 La cicloide alargada dada por 6 2 Ecuaciones paramétricas y cálculo 1p2 2 x p Recta tangente cuando t 5 2 . 2 y y225 1p2 2 x. Recta tangente cuando t 5 p . 2 Si dyydt 5 0 y dxydt Þ 0 cuando t 5 t0, la curva representada por x 5 f std y y 5 gstd tiene una tangente horizontal en s f st 0d, gst 0dd. Así, en el ejemplo 3, la curva dada tiene una tangente horizontal en el punto s0, 2 2 pd (cuando t 5 0). De manera semejante, si dxydt 5 0 y dyydt Þ 0 cuando t 5 t0, la curva representada por x = f(t) y y = g(t) tiene una tangente vertical en s f st 0d, gst 0dd. Longitud de arco Se ha visto cómo pueden emplearse las ecuaciones paramétricas para describir la trayectoria de una partícula que se mueve en el plano. Ahora se desarrollará una fórmula para determinar la distancia recorrida por una partícula a lo largo de su trayectoria. Recuérdese de la sección 7.4 que la fórmula para hallar la longitud de arco de una curva C dada por y 5 hsxd en el intervalo fx0, x1g es s5 5 E E! x1 x0 x1 !1 1 fh9sxdg 2 dx 11 x0 1dy dx 2 2 dx. Si C está representada por las ecuaciones paramétricas x 5 f std y y 5 gstd, a ≤ t ≤ b, y si dxydt 5 f9std > 0, se puede escribir s5 E! x1 x0 11 1dy dx 2 2 dx 5 E! E! E !1 E x1 x0 b 5 a b 5 a 11 1dyydt dxydt 2 2 dx sdxydtd 2 1 sdyydtd 2 dx dt sdxydtd2 dt dx dt 2 1 1dydt2 2 2 dt b 5 !f f 9stdg 2 1 fg9stdg 2 dt. a 10-3.qxd 3/12/09 724 16:47 Page 724 CAPÍTULO 10 Cónicas, ecuaciones paramétricas y coordenadas polares TEOREMA 10.8 LONGITUD DE ARCO EN FORMA PARAMÉTRICA Si una curva suave C está dada por x 5 f std y y 5 gstd y C no se corta a sí misma en el intervalo a # t # b (excepto quizás en los puntos terminales), entonces la longitud de arco de C en ese intervalo está dada por E !1 b s5 a dx dt 1 dy dt E b 2 1 2 2 2 dt 5 !f f 9stdg 2 1 fg9stdg 2 dt. a NOTA Al aplicar la fórmula para la longitud de arco a una curva, hay que asegurarse de que la curva se recorra una sola vez en el intervalo de integración. Por ejemplo, el círculo dado por x 5 cos t y y 5 sen t, recorre una sola vez el intervalo 0 # t # 2p, pero recorre dos veces el intervalo 0 # t # 4p. n En la sección anterior se vio que si un círculo rueda a lo largo de una recta, cada punto de su circunferencia trazará una trayectoria llamada cicloide. Si el círculo rueda sobre otro círculo, la trayectoria del punto es una epicicloide. El ejemplo siguiente muestra cómo hallar la longitud de arco de una epicicloide. Calcular la longitud de arco EJEMPLO 4 Un círculo de radio 1 rueda sobre otro círculo mayor de radio 4, como se muestra en la figura 10.33. La epicicloide trazada por un punto en el círculo más pequeño está dada por ARCO DE UNA CICLOIDE La longitud de un arco de una cicloide fue calculada por vez primera en 1658 por el arquitecto y matemático inglés Christopher Wren, famoso por reconstruir muchos edificios e iglesias en Londres, entre los que se encuentra la Catedral de St. Paul. y t se enta em cr x −2 2 −2 −6 x = 5 cos t − cos 5t y = 5 sen t − sen 5t E !1 E E E E E py2 54 py2 0 5 20 5 20 5 20 5 40 dx dt py2 0 py2 Figura 10.33 2 2 dt Forma paramétrica de la longitud de arco. !2 2 2 sen sin t sen sin 5t 2 2 cos t cos 5t dt !2 2 2 cos 4t dt 0 py2 !4 sen sin22 2t dt Identidad trigonométrica. 0 py2 sin 2t dt sen 3 4 5 220 cos 2t 5 40 2 1 1dydt2 !s25 sen sin t 1 5 sen sin 5td2 1 s5 cos t 2 5 cos 5td2 dt 0 Un punto en la circunferencia pequeña es el que traza una epicicloide en la medida que el círculo pequeño rueda alrededor de la circunferencia grande y 5 5 sen sin t 2 sen sin 5t. Solución Antes de aplicar el teorema 10.8, hay que observar en la figura 10.33 que la curva tiene puntos angulosos en t 5 0 y t 5 py2. Entre estos dos puntos, dxydt y dyydt no son simultáneamente 0. Por tanto, la porción de la curva que se genera de t 5 0 a t 5 py2 es suave. Para hallar la distancia total recorrida por el punto, calcular la longitud de arco que se encuentra en el primer cuadrante y multiplicar por 4. 0 in y Hallar la distancia recorrida por el punto al dar una vuelta completa alrededor del círculo mayor. s54 2 −6 x 5 5 cos t 2 cos 5t py2 0 Para la epicicloide de la figura 10.33, una longitud de arco de 40 parece correcta, puesto que la circunferencia de un círculo de radio 6 es 2p r 5 12p < 37.7. 10-3.qxd 25/2/10 13:07 Página 725 SECCIÓN 10.3 EJEMPLO 5 0.5 pulg Ecuaciones paramétricas y cálculo 725 Longitud de una cinta magnetofónica Una cinta magnetofónica de 0.001 pulgadas de espesor se enrolla en una bobina cuyo radio interior mide 0.5 pulgadas y cuyo radio exterior mide 2 pulgadas, como se muestra en la figura 10.34. ¿Cuánta cinta se necesita para llenar la bobina? 0.001 pulg Solución Para crear un modelo para este problema, supóngase que a medida que la cinta se enrolla en la bobina, su distancia r al centro se incrementa en forma lineal a razón de 0.001 pulgadas por revolución, o 2 pulg r 共0.001兲 4 000 x r cos (x, y) y r θ 1 000 donde está medido en radianes. Se pueden determinar las coordenadas del punto (x, y) correspondientes a un radio dado x = r cos θ y = r sen θ y , 000 2 22000 x y r sen sin . Al sustituir r, se obtienen las ecuaciones paramétricas x Figura 10.34 cos 冢22000 000 冣 y y sin . sen 冢22000 000 冣 La fórmula de la longitud de arco se puede emplear para determinar que la longitud total de la cinta es s 冕 44000 000 11000 000 冪冢ddx冣 冢ddy冣 d 2 冕 冕 4000 4 000 2 1 22000 000 1 22000 000 1 1 冪 2 1 ln 冪 2 1 22000 000 2 1 000 1000 4000 4 000 1 000 1000 冪共 sen sin cos 兲2 共 cos sen sin 兲 2 d 冪 2 1 d 冢 冣冤 ⱍ ⱍ冥 44000 000 11000 000 Tablas de integración (apéndice B), fórmula 26. 781 pulgadas ⬇ 11 11,781 inches ⬇ 982 982 pies feet PARA MAYOR INFORMACIÓN Para más información sobre las matemáticas de una cinta magnetofónica, consultar “Tape Counters” de Richard L. Roth en The American Mathematical Monthly. La gráfica de r a se llama espiral de Arquímedes. La gráfica de r 兾2 000 (ejemplo 5) es de este tipo. I NOTA La longitud de la cinta del ejemplo 5 puede ser aproximada si se suman las porciones circulares de la cinta. El radio de la más pequeña es de 0.501 y el radio de la más grande es de 2. s ⬇ 2 共0.501兲 2 共0.502兲 2 共0.503兲 . . . 2 共2.000兲 1500 1 500 兺 2 共0.5 0.001i兲 i1 500(0.5 500)(1 501)/2兴 1500 共0.5兲 0.001(1 0.001共1500 兲共1501 兲兾2兴 2 关关1 786 inches pulgadas ⬇ 11 11,786 10-3.qxd 3/12/09 726 16:47 Page 726 CAPÍTULO 10 Cónicas, ecuaciones paramétricas y coordenadas polares Área de una superficie de revolución La fórmula para el área de una superficie de revolución en forma rectangular puede usarse para desarrollar una fórmula para el área de la superficie en forma paramétrica. TEOREMA 10.9 ÁREA DE UNA SUPERFICIE DE REVOLUCIÓN Si una curva suave C dada por x 5 f std y y 5 gstd no se corta a sí misma en un intervalo a # t # b, entonces el área S de la superficie de revolución generada por rotación de C, en torno a uno de los ejes de coordenadas, está dada por E E b 1. S 5 2p a b 2. S 5 2p !1dxdt2 1 1dydt2 dx dy f std!1 2 1 1 2 dt dt 2 gstd a 2 2 dt Revolución en torno al eje x: g(t) ≥ 0. dt Revolución en torno al eje y: f(t) ≥ 0. 2 Estas fórmulas son fáciles de recordar si se considera al diferencial de la longitud de arco como ds 5 !1dxdt2 1 1dydt2 dt. 2 2 Entonces las fórmulas se expresan como sigue. E b 1. S 5 2p 2. S 5 2p a Hallar el área de una superficie de revolución EJEMPLO 6 ( 32 , 3 2 3 ) ) , 23) f std ds a y y E b gstd ds 3 2 Sea C el arco de la circunferencia C 1 x2 1 y 2 5 9 (3, 0) x −1 1 4 −1 −2 −3 Esta superficie de revolución tiene un área de superficie de 9phas a surface area The surface of revolution Figura 10.35 of 9p. Figure 10.35 que va desde s3, 0d hasta s3y2, 3!3y2d, como se ve en la figura 10.35. Encontrar el área de la superficie generada por revolución de C alrededor del eje x. Solución C se puede representar en forma paramétrica mediante las ecuaciones x 5 3 cos t y 5 3 sen sin t, y 0 # t # py3. (El intervalo para t se obtiene observando que t 5 0 cuando x 5 3 y t 5 py3 cuando x 5 3y2.d En este intervalo, C es suave y y es no negativa, y se puede aplicar el teorema 10.9 para obtener el área de la superficie E E E S 5 2p 5 6p 5 6p py3 0 py3 s3 sen sin td!s23 sen sin td2 1 s3 cos td2 dt sin t!9ssen sin22 t 1 cos 2 td dt sen 0 py3 3 sen sin t dt 0 3 4 5 218p cos t 5 218p 5 9p. Fórmula para el área de una superficie de revolución. py3 0 1 12 2 12 Identidad trigonométrica. 1059997_1003.qxp 9/8/08 3:54 PM 1059997_1003.qxp 9/8/08 3:54Page PM 10-3.qxd 3/12/09 16:47 8/08 1059997_1003.qxp 3:54 PM Page 727 9/8/08 1059997_1003.qxp 9/8/08 3:54 PM 1059997_1003.qxp 9/8/08 3:54 3:54 PM PM 1059997_1003.qxp 9/8/08 3:54 PM Page 727 Page 727 727 Page Page 727 Page 727 727 Page 727 10.3 10.310.3Parametric Parametric Equations andCalculus Calculus SECCIÓN Ecuaciones paramétricas y cálculo 10.3 Equations and 10.3 Parametric Equations and Calculus Parametric Equations and Calculus 727 10.3 Parametric Equations and Calculus 10.3 Parametric Equations and Calculus 10.3 Parametric ParametricEquations Equationsand andCalculus Calculus 10.3 727 727 727 727 727 727 727 727 Exercises www.CalcChat.comforforworked-out worked-outsolutions solutionstotoodd-numbered odd-numberedexercises. exercises. 10.3 Exercises Ejercicios SeeSeeSeewww.CalcChat.com 10.3 10.3 Exercises www.CalcChat.com for worked-out solutions to odd-numbered exercises. 10.3 Exercises 10.3 See www.CalcChat.com for worked-out solutions to odd-numbered exercises. Exercises See www.CalcChat.com for worked-out solutions toto odd-numbered exercises. Exercises See www.CalcChat.com for worked-out solutions odd-numbered exercises. 10.3 See www.CalcChat.com for worked-out solutions to odd-numbered exercises. 10.3 Exercises See www.CalcChat.com for worked-out solutions to odd-numbered exercises. ParametricEquations Equations Parameter dydx. Exercises 1–4,4, Parametric Parameter Ecuaciones paramétricas Parámetro /dx.dy dx. InInExercises 1– En los ejercicios 1 find afind 4, dy hallar Parametric Equations Parameter In Exercises 1– 4, find dy//dx. / 2 3 2 3 Parametric Equations Parameter x t t Parametric Equations Parameter t 2, y t 3t 21. Parametric Equations Parameter 2 3 Parametric Parameter es 1– 4, find dy/dx. In t tParameter 11 t 1Equations 2,2, yy 5tt3 23t3t 21. dy In Exercises 1– find 2 1– 21. xParametric dydx. In1.Exercises Exercises 1–4,4, 4,find find6tdy dx. 3 3t,t,y y5 4 42 t t /dx. In xx 5 tt2222 2 tt Equations tt 5 21 1 2, y t333 3t 21. xx t 2t2, ,yy1– 4, 77find 6t dy///dx. 1. Exercises 2.2.x x5 ! 3 2 3 7 6t 2 1. x t2232, y2 2. x21. x333 t, ty 4t t2, y t 3t 21. xxx tttt22 t1tt 2,2, ttt 3331p11 ttt33 3t 3t 21. 2, yyyy3 sin 3t 21. 2 2 3 x t t 1 t 2, t 3t 21. 2 2 2 u 2 u y2 x x t , y 7 6t t, y 4 t 1. 2. x 4 cos , y 22. x 2e , y e x sin , y cos y 7 6t t, y 4 t 2. 3. 4. 2 x x t , y 7 6t t, y 4 t 1. 2. t , ,2yuy, y75 7 cos t 1. x x5 sen 2. x x5 2e 2 3 ,t, yy5 e4 22. sin 3. 4. cos u,,, yyy 5333sin sin u u 5 334 22. xxx 5444cos sen 6t6t2u 1. 2. cos sin 22. cos 3. xx tsin 4. xx 2et,, yy 4e 22t22 3 3434 222 , y 222 22 2 34 x2e 4yyycoseee , y22 3 sin 2e , ,y,, yyy e cos n2 , y cos2 4. xxx 444cos ,,, yyy 333sin 22. x2x22. 2e , xxx sin 3.3. 4.4. cos sin 22. , sin cos cos sin 22. x 2e , sin cos 3. 4. 2 2 2 2 2 d In Exercises 5 –14, find and and find the slope dy dx y/dx , x 4 cos , y 3 sin 22. x 2e y e x sin , y cos 3. 4. 4 444 de las rectas tan2 2 /dxdy In Exercises 5 –14, and thelaslope dy/ dx , and dxddy2y/dx d y / 2dx , asífind En los ejercicios 5 a find 14, hallar como penEn los ejercicios 23find afind 26,the hallar las ecuaciones 4tangentlines / In Exercises 23–26, the equations of the linesatatthe the In Exercises 5 –14, find and and find the slope dy y/dx , In Exercises 23–26, equations of the tangent / 22y/dx 22,2 and and concavity (if possible) at the given value of the parameter. 2 2 2 2 2 d In Exercises 5 –14, find and find the slope dy dx and concavity (if possible) at the given value of the parameter. dExercises es 5 –14, find dy/ dx and and find the slope y/dx In Exercises 23–26, find the equations the tangent lines at the d y/dx In 5(if –14, find and and find the slope dy ,, of diente y la ,concavidad (de ser posible) en2,el punto corresponInExercises Exercises –14, find and and find theslope slope dy dx y/dx gentes en el the punto en el que laitself. curva seofcorta a sí misma. //at/dx point where thecurve curve crosses itself. /dx and concavity possible) the given value the parameter. dd2In In 55–14, find and and find the dy y/dx point where crosses Exercises 23–26, find the equations of the tangent lines at the In Exercises 23–26, find the equations of the tangent lines at the In Exercises 23–26, find the equations of the tangent lines at the InExercises Exercises 23–26, find theequations equations thetangent tangentlines linesatatthe the and concavity (if possible) atthe the given value ofthe the parameter. vity (if possible) at thediente given value the parameter. point where 23–26, the curve crosses itself. ofofthe and concavity possible) at of In find the al valorof(if dado del parámetro. and concavity (if possible) thegiven givenvalue value theparameter. parameter. Parametric Equations Point and concavity (if possible) atatthe given value ofofthe parameter. Parametric Equations Point point where the curve crosses itself. point where the curve crosses itself. point where the curve crosses itself. point where the curve crosses itself. sen 23. x 5 2 sin 2t, y 5 3 sin t sen x 2 sin 2t, y 3 sin t 23. Parametric Equations Point point where the curve crosses itself. 23. x 2 sin 2t, y 3 sin t etric Equations Point x 4t, 4t, t 33 23. x 2 sin 2t, y 3 sin t Equations Point Parametric Equations Point Punto Parametric Equations Point xParametric yy paramétricas 3t3t 22 5.5.Ecuaciones sen 2 cos 5 sin 24. 2t, t2ttt 2 psin 23. sin 2t, sin 23. cosyt,yyt,t, y3yy33sin sinttt 23. xtPoint 24.xxxxx 522222sin x 4t, y Equations 3t 2 t 23sin 2t, y 3 sin t 24. 5. Parametric sinp 2t, sin 23. cos 2t2t 23. x 4t, y 3t 2 t 3 5. x t , y 3t 1 t 1 y 3t 2 t 3 6. sin t 24. xx 2222sin 2t,cosyt, 33y3 sin2tt x t 3 5. 4t, y 3t 2 t 5 3 5. 4t, y 3t 2 3 5. x t x t , y 3t 1 1 6. 3t 25. 5. cos t, y 2t 25. sinxxxxxt 5t2t222t 2t,t,t,cos 3t 24. xtt 231 25. 2t 24. cos t,t, tt3tyyy23t 2t 2 11 sin sin 24. 6. xx 4t, t ,y y 3t3t 22 1 cos sintttt 24. yyyt,5 2t2t 11 sin 24. 2t 1 t , y 3t 1 7.xxxx5 ! 25. xx 2t222323 t, cosy t, t33y33 22 3t 3t 1113t3t 6.6. yy15 3t ttttt5 11121111 6. , yyy1, 3tt2 6. t t tttt,t,,,1, yy 3t 7. 3 2 x 5 t 2 6t, y 5 t 26. 2 3 x 3t 1 6. t, y t 3t 1 x t 25. 3 2 t, y t 3t 1 25. 3t 126. 25. xt t 1 t, y t 26.xxx t t2t 6t, 7. x t 2 1, y t222 3t t,6t, y y 3t t 3t 1 25. 25. 0111 1, y t 2 3t y 3t 8.xxxxx5 ttt2tt1t 1, 26. xx tt3333 t,6t, y y t t2222 3t 1 1,1, t2tt2y21 3t3t 7.7. yyyy154,t4, ttttt5 21 7. 1, 3t 7. 5t5t 4t4t 8. 7. 26. xtt t003 1 6t, y t 2 xxx tt3t 3 6t, yyy tt2t 2 26. 6t, 26. 8. xx tt2222 1,5ty 4,t y 3t4t 6t,27 26. x ejercicios t 27 6t, y y28, t find 26. En los 28, hallar los puntos dehorizontal tangencia and horiInExercises Exercises 27 and findall alltodos points any)ofof horizontal and 0 4,4, 5t 4, y 4t xxx ttt22t 5t 8.8. 5t 4t In and points (if(if any) ttttt5 00000 8. 5t 4, yy4yy sen4t 4t 8. x t 5t 4, 4t 8. x 4 cos , y 9. In Exercises 27 and 28, find allporción points (if any) of horizontal and 9. x 4 cos , y 4 sen zontal y vertical (si los hay) a la de la curva que se muestra. vertical tangency to the portion of the curve shown. vertical to 28, the portion of the (if curve shown. p44 27 and 28, find all points In Exercises (iftangency any)27 ofand horizontal and In Exercises find all points any) of horizontal and 9. x 4 cos , y 4 sen In Exercises 27 and 28, find all points (if any) of horizontal and In Exercises 27 and 28, find all points (if any) of horizontal and vertical tangency to 28, thefind portion of the(if curve In Exercises 27 and all points any)shown. of horizontal and u5 4 9. cos , y 4 sen xx 444cos sen 9.9. cos sen cos , ,,4,,yyyyy 34444sin sen tangency to the portion of the curve shown. vertical tangency to the portion vertical of curve shown. vertical tangency to the portion of the curve shown. 4cos cos 9.9. xxxx cos vertical tangency tothe theportion portion of thexcurve curve shown. 10. 5 2u Evolvente de un círculo: 28. 27. 2 xshown. 27.the Involute ofoaainvoluta circle: 28. , y 3 sinsen 0444404 10. vertical tangency to of the x 2 27. Involute of circle: 28. 0 10. x cos , y 3 sin 27. Involute of a circle: 28. x 2 xxxx5 cos u,,,,y0yyy5 3333sen sin u u 5 0000 of a circle: 10. s , y 3 sin cos sin 10. cos sin 10. y 2s1 2 cos ud x 5 cos u 1 u sen u cos sin 10. cos y 2 1 cos sin x 2 27. Involute 28. x 2 27. Involute of a circle: 28. x 2 27. Involute of a circle: 28. 27. xInvolute Involute 28. yxx 2221 5cos cos of a circle: sin ,sec y , ,y3ysin11 22tan 0 10. 2 sec tan 11.xxx 2cos 27. 28. 11. x cos of a circle: y 2 1 cos sin 6 p 11. x 2 sec , y 1 2 tan 6 x cos y 2 1 cos sin sen ucos xu 5 cos 2cos sin1 u 2cos cos sin cos y 2 1 cos sin cos sin u xxx5 2221 sec 11. yxyxyx 5 sin sec tan 11. 6 sec , y 1 2 tan sec tan 11. yy 2211 cos sin secu,,,, yyyy5 11111 2222tan tanu 11. y cos sin yy cos 11. 12.xxxx 22 t,t,sec yy yy6 , yt t 111 2 tan t t sin 2666266 12. y cos y sin cos y y y sin cos sin y cos cos 12. xx 5 !t,t, yy 5 !tt 2 11 yy sin y tttt5 2222 12. xxx ttt 1311 12. t, y t 1 tt,t,t,3yyy2 12. t 22 y 12. y 88yyyy 10 10yyyyy x t, y t 1 t 12. 3 3 , y sin x cos 13. 8 10 y 13. x cos 3 , y sin 3 p 8 10 sin3333u cos3333u,, yy 5 sen 13. xx 5 cos 88 u 5 444 8 13. 6886886 10 10 10 ,,, yyy sin sin xxx cos 10 13. 810 s 3 , y sin 3 sin cos 13. sin331 cos cos33 sin 13. 444 8644 10 8 , y sin x cos 13. 4 x , y 14. 46 46666 686 sin , y 1 cos 14. x 8 8 θ 8 6 4 8 sinu,, yy 5 11 2 cos cosu 14. xx 5 u 2 sen θθ 64 86 sin u5p 4 242442 xxx sin ,,, yyy 111 cos 14. θ sin , y 1 cos 14. 464 sin cos 14. sin cos 14. 6 6 6 2 4 6 4 x x x sin , y 1 cos 14. θ θ In Exercises 15–18, find an equation of the tangent line at each θ θ x 64 In Exercises 15–18, find an equation of the tangent 2 line at each 22 −6 −2 In Exercises 15–18, equation of the tangent at each −6 −2222 22θ2 444 666 888 x En los ejercicios 15 curve. yfind 18, an hallar una ecuación para laline recta tan4 2442442 −6 −2 given point on the x In Exercises 15–18, find an equation of the tangent line at each x x given point on15–18, the curve. es 15–18, find an equation of the tangent line atan each 42 x In Exercises find equation of the tangent line at −6 −2 2 4 6 8 InExercises Exercises 15–18, find an equation the tangentline lineat at each each given point on the de curve. In 15–18, find equation the gente en cada uno los an puntos dadosofof de la curva. xxx −4 −6 −2 2 −4 2222 4444 6666 8888 x 2222 −6 −2 6 8 −6tangent −2 2 4 each −6 −2 −6 −2 −4 given point on the curve. on the curve. given point on the curve. 10 12 22 444 666 888 10 2 1012 12 x given point on the curve. 6 8 −6 −2 2 4 −4 2 x 2 cot x 2 3 cos 15. 16. given on the curve. x point 2 cot 15. 16. x 2 3 cos x 2 4 6 8 10 12 xxxxx −4 −4 u −4 −4 cotu2 cos 15. xx 5 22cot 16. xx 5 22 2 33cos −4 15. 16. 10 12 2−4 4 6 8 10 12 2222 4444 6666 8888 10 10 12 10 12 12 sin23 cos y 3 2 sin cot 16. xyxxxy 2222sin cot x 2 3 cos 15. 16. cot x 2 3 cos 15. 16. cot x 2 3 cos 15. 16. sin 2 4 6 8 10 12 cot cos 15. yxy 5 222sen 16. yyxy 5 3323 1 2232sin 22 sin sin sin u u sen 2 222 In Exercises 29–38, find all points (if any) of horizontal and y3 22sin y En los ejercicios 29 a 38, hallar todos los puntos de tangencia 2 sin y sin sin 2 sin In Exercises 29–38, find all points (if any) of horizontal and yyy 2232sin y 3 y y sin2y y sin In Exercises 29–38, find all points (if any) ofutility horizontal and y 2 sin yy yy33 22sin vertical tangency to the curve. Use a graphing to confirm horizontal y vertical (si los hay) a la curva. Usar una herramien3 4 + 3 y y vertical tangency to the curve. Use a graphing utility to confirm In Exercises 29–38, find all points (if any) of horizontal and y y y In Exercises 29–38, find all points (if any) of horizontal and y y y 3 4 + 3 In Exercises 29–38, find all points (if any) of horizontal and In Exercises Exercises 29–38, find all points points (if any) any) ofof horizontal and 6 y 66 y vertical tangency to the curve. Uselos a (if graphing utility to confirm In 29–38, find all horizontal and (2,5)5) 44 ++ 332 33,, 22, 2 6 6y 666 y (2, your results. ta graficación para confirmar resultados. your results. vertical tangency adegraphing utility to confirm vertical tangency to the curve. Use aaagraphing utility to confirm 5)5) vertical tangency to the curve. Use graphing utility to confirm 33,, 22 curve. Use 4+3 3 5 (2, 3the 444++ vertical tangency to the curve. Use graphing utility to confirm 22323to (2, + 3 6 5 6 your results. 6666 6 6 vertical tangency to the curve. Use a graphing utility to confirm , 2 6 ,2 4 + 23 3 , 2 5656 (2, (2, 5) (2, 5) 64 your results. (2,5) 5) your results. 2 ,2 your results. 2 your results. (0,2)2)2 22 33 4 29.xxresults. 30.xx t t 1,1, yy t 2t 2 3t3t 29. 5555 (2, 5) 22 your 44 t,t, yy t 2t2 29. 30. −2−5 23, , 342 44 (0,(0, 2) (0, 2) 5 1 x 4 t, y t x t 1, y t2222 3t 29. 30. ,223 3, 233 444 (0, 2) 2 3 ,1 − − 2 2 3 4 (0, 2) (0, 2) (0,22) 2) −−−3 2223, ,,323 4 23 , 31, 12 4, 29. x(−(−1,1,43)3) t, y t 2 30. 31.xxxxx t44t4 4,t,1, yyyy ttt322tt323 3t3t xxx ttt 1,1, yy tt 2 3t 29. 30. 30. t, 3t 29. 30. t, 29. 30. y 31. (0, 2 2 , t, yy tt 29. 30. x t 1,1, yy t t2 3t3t − 333, 222 2 1 (−1, 3t3 23 1211 31. xx 4t 2 4, (− 1,3)3) 333 3 3 2 3, 2 , 3 2 1 2 , 3 x t 4, y t 3t 31. 3 33t 31. t t 3t3t 3t 31. 32.xxx t t2t 4, 31. 1 x(− (− 1, 3) 4, 31. (− 1,t3) 3) 4, y 2 t t yy2,2, ytt3y t 3t 32. 22 33, ,222x x (−1, 31. 111 (− 1,1,3)3) t33333 3t 32. xx tt22222 4,t y 2, t y 3t x 3 − 4 −− 2 2 4x 2 x 2 x 2 − 4 2 2 4 1 32. x 3 cos , y 3 sin x t t 2, y t 3t 32. 33. 1 x t t 2, y t 32. x 5 t 2 t 1 2, y 5 t 3t 32. 1 1 32. x x 3t2cos t, y2, 3y sin t33 2 3t 1 33. x −4 − 4 −2 − 2 2 2 4 4 xxxx 1 2 3 4 5 6 xx 3t3t 32. −1−11 33. xx t3 cost , 2,y y3 sint −2 −−−4444 − −−−2222−2 222 444 xx −1 111 222 333 444 555 666 xxxx 2 2 4 − 2 4 −1 x 3 cos , y 3 sin 33. sin 33. , y 3 sin 33. x 1 32 cos 34.xxx 5cos 33cos cos 333sin sin 33. sen cos, ,u,,,,yyyyyy 5 sin −22 3 42 5 46 33. −−1 4 − 2−2 22sin 22u 34. −1 1−2 −1 111 222 3333 4444 5555 6666 x −1 cos sin 33. −1 , y 2 3sin 2 34. xx 3cos −2 −2 −1 −2 2 −2 41 2 2 3 4 5 6 2 4 x t 4 x t 17. 18. −2 , y 2 sin 34. x cos , y 2 sin 2 x 5 3 cos , y sen 34. 35. x cos , y 2 sin 34. x 5 cos u , y 5 2 sin sen 34. sin2222u 22 sen 34. x x 5cos 3, ,cos 17. x t 2 4 18. x t 4 2 35. yy ,, 22ysin 34. 17. x t22224 4 18. x t4443 2 5 32cos y 2 2 sen 35. xx cos 2 4 x t 4 2 x t 17. 18. x 5 3 cos , y 2 sen 35. 4 2 18. 35. cos233 cos sin 22 sen 2 36. senxxx 4554cos 36. 442t 17. 18. 35. xy txt3t4 5t 22t 3 cos , y 17. yxxxxy tt2t2tt2 2t 18. yxx35. cos sen 35. , , y,y,, y2yy2sin 17. 18. 35. y tt3333 2t y t2223 42t , y 2 sin 2 sen 36. xx 54 cos322222cos 2, y 18, 2 3 2 0, 0 , 3, 1 , 3, 3 2, 0 , 3, 2 10 2t t y , y t 36. yy0, t 2t t x 4 cos y 2 sin x sec , y tan , 36. 37. y t t 2t t x 4 cos y 2 sin , 36. x 5 4 cos u , y 5 2 sin u 36. sen y 0 t,t3 3, t t 2 , y 18, 10 2t 1 , y 3, 3 4cos cos,2 ,y, yytan22sin sin 36. x x sec 37. y2, yy0, 00t,2t, 3, 2t 36. 3, 1 , y 3, 3 2, 0 , 3, 2 , y 18, 10 , y tan 37. xx 4sec 0,0, 000,,, 3,3,3, 333 2,2, 000x,,, 3,3, 10 sec 3, 1 , y 3, 3 2, 211,1,y,,yyy18, 3, 10 tan 37. cosu cos2 u2,,,,, , yyyyyy5 tan sec222,,,,yyy y18, tan 37. 38.xxxx 5cos 3, 18, 10 37. sec tan 37. 0, 3, 3, 2, 3, 18, 10 sec tan 37. cos 38. 0, 0 , 19–22, 3, 1 ,(a) 3,aa3graphing 0 , 3,totograph 2graph , y the 18, 10 y use 37. Exercises 19–22, (a) use graphing2, utility thecurve curve cos cos22222 , , yy tan 38. xx sec InInExercises utility 2de graficación In Exercises 19–22, use a graphing utility tocos graph the curve cos 38. a) usar una herramienta En los ejercicios 19 a(a) 22, , athe ygraphing cos x (b) 38. xxx 5 cos 38. cos 5 cos cos u 38. , yyy–yy 44, cos cos22 u,,,,39 38. represented by the parametric equations, use In Exercises 19–22, (a) use a graphing utility to graph curve represented the parametric equations, (b)to use a graphing cos xExercises cos 38. es 19–22, (a) use a graphing utility by to graph the curve In determinethe thet tintervals intervalson onwhich whichthe the In Exercises 19–22, (a) use a graphing utility graph the curve In Exercises 19–22, (a) use a graphing utility to graph the curve In Exercises 39 – 44, determine represented by the parametric equations, (b) use a graphing para trazar la curva representada por las ecuaciones paramétriIn Exercises 19–22, (a) use a graphing utility to graph the curve dx/dt, dy/dt, dy/dx utilitytotofind find anddy/dx the given value the In Exercises 39 –downward 44, determine the t intervals on which the dx/dt, dy/dt, and atatExercises the given value ofofdetermine the represented by the parametric equations, (b) use aa–graphing graphing d by the parametric utility equations, (b) use a graphing represented by the parametric equations, (b) use a curve is concave or concave upward. represented by the parametric equations, (b) use graphing curve is concave downward or concave upward. In 39 44, the t intervals on which the In Exercises 39 – 44, determine the t intervals on which the In Exercises 39 – 44, determine the t intervals on which the dy/dt, utility to find and at the(b) given value of the twhich en losthe que En los a 44, determinar intervalos dewhich In Exercises Exercises 39–39 –44, 44, determine thelos intervals on on the cas, represented bydx/dt, the parametric equations, use atographing b) usar una herramienta dedy/dx graficación para dxydt, parameter, (c) find an equation of thetangent tangent linehallar theof curve curve isejercicios concave downward or concave upward. In 39 determine the t t intervals (c) find an equation of the line to the curve dy/dx nd dx/dt, dy/dt, and parameter, given value of and the dy/dt, dy/dx utility to find at given value the dx/dt, dy/dt, dy/dx utility tothe find and at the given value of the dx/dt, dy/dt, dy/dx utilityyat find and atthe the given value ofuna the or concave is(d) concave downward curve isis concave downward or concave upward. curve concave downward or concave upward. parameter, (c)dx/dt, find an equation of thecurve tangent line to the curve 2cóncava 3hacia la curva es abajo o cóncava hacia arriba. curve isupward. concave downward orconcave concave upward. dx/dt, dy/dt, dy/dx utility toto find and at the given of the dyydt dyydx para elof valor dado del parámetro, c)value hallar 2 3 y t x 3t , t 39. at the given value the parameter, and use a graphing curve is concave downward or upward. 39. x 3t 2, y t 3 t the tangent given(c) value of the parameter, and (d) line use ato the graphing (c) find an equation at of line the curve parameter, find an equation of tangent to curve parameter, (c) find an equation of the the tangent line the curve parameter, (c) findto an equation the tangent line the curve 39. x 3t222, y2 t333 2t at the given of the parameter, and (d)elline use a the graphing parameter, (c) find an equation ofof tangent toto ecuación de lavalue recta tangente athe lathe curva en dado 2valor 3curve utility to graph thecurve curve and tangent line from (c).del 39. at the given of the parameter, and (d) use aaapart graphing 39. t(c). utility to graph the and the tangent from xline 3t , ypart t 22,2,, t 2ty,yy, yytt3t 3 t 2tttt t 3t 3 39. 40.xxxx 23t3t n value of the parameter, and (d)value use aof graphing at the given value the parameter, and (d) use graphing 39. 3t 39. at the given value of the parameter, and (d) use graphing 40. utility graph the of curve and the tangent line part (c). 39. at the to given value the parameter, and (d) from use apara graphing parámetro, y d) usar una herramienta de graficación trazar 2 , t222y2, yt t2222t t3333 40. xx 3t 2 2 3 utility to graph the curve and the tangent line from part (c). raph the curve and the tangent line from part (c). utility to graph the curve and the tangent line from part (c). 2,, t,yyy 5 utility graph the curveand and the tangent line2from from (c). 40. 2ttt3t 3lnlnt t xline t part , part y (c). t t 40. 41.xxxx 52t 2222t1 ttln 40. 40. Parametric Equations Parameter t ,ln 40. 2 t, yy tt2t 22t1 41. utility totoygraph the curve tangent la curva la recta tangente delthe inciso c).Parameter Parametric Equations 40. 41. xx 22t2 t ln, t,y y t 2t t ln t Parametric Equations Parameter 2 x 2t ln t, y 2t 41. 2 x 2t ln t, y 2t 41. t, ,1yyln t,lnlnt yt 5 2t 2 lnln 41.tParameter 42.xx 5t 2t 41. x Parameter 6t,yy Equations t x 112t ln t, y 2t ln t42. etric Equations 19.xParametric lnttt 41. Parametric Equations Parameter Parametric Equations Parameter 6t, t 2t2 44 19. 41. Parametric Equations Parameter Ecuaciones paramétricas Parámetro t2222, yln t, ln yt 2t ln t 42. xx 2t x 6t, y t t 1 4 19. 2 2 42. yln 42.ttt x 111 t , y ln t 43.xxxx 5sen tt2tsen ,2,, t,yt,yy 5 42. 6t, 19. ln ttcost,t, 00<<t t<< 42. y t2 4 1yyy ttt2222 11444 lnttcos 42. xx t6t, 19. 43. 6t, 19. , t,y yy ln 42. t t 111 19. 19. t y2, 2,yyt 1 4 33 20.xxxx t6t, cos t, 0 < t < 43. xx tsen t 20. x sen t, y cos t, 43. t x sen t, y cos t,t, t,0000t,< < 43. 4cos cos t<<22 t43. < xx 54sen 43.t x 1 sen t, y cos t, 0 < 44. 44. 20. x t 2, y 1t11 3 sin t, cos t,sen << << 1 sen t,t,t,yyyy5y cos cos <00ttttt<< <tp 43. 22sen 0t, < x sen t, t, < 43. t 1 x t 2, y 3 t 1 20. 2, y 3 t 1 x 4 cos t, y 2 sen t < 2 44. 0 < x t 2, y 3 t 1 20. x t 2, y 3 t 1 20. t x 1 4 cos t, y 2 sen t, 044. 20. x t 2, y 20. t ttt 3 44. < txxx< 2444cos 44. t, y 2 sen t, < t << 22 0 cos t, y 2 sen t, < t 0 44. cos t, y 2 sen t, < t 44. 0 t 44. x 4 cos t, y 2 sen t, 0 < t << 22 ) ) ( ))))) ) ))))) ) ) ) ) ) ( )))) ) )))) ) ) )) )) )()) ))) )))))) ))) 9/2/08 1059997_1003.qxp 9/2/08 3:50 PM Page 728 1059997_1003.qxp 9/2/08 Page 3:50728 PM Page 728 10-3.qxd 3/12/09 16:47 3:50 PM Page 728 1059997_1003.qxp 9/2/08 3:50 PM Page 728 1059997_1003.qxp 9/2/08 3:50 PM 1059997_1003.qxp 9/2/08 3:50 PM Page 728 1059997_1003.qxp 9/2/08 9/2/08 3:50 3:50 PM PM Page Page728 728 1059997_1003.qxp Page 728 1059997_1003.qxp 9/2/08 3:50 PM Page 728 728 CAPÍTULO Cónicas, ecuaciones paramétricas y coordenadas polares Chapter 10 10 Conics, Parametric Equations, and Polar Coordinates 728 Chapter 10 Conics, Parametric Equations, and Polar Coordinates Conics,728 ParametricChapter Equations, and Polar Coordinates 10 Conics, Parametric Equations, and Polar Coordinates 728 Chapter 728 Chapter 10 Conics, Parametric Equations, and Polar Coordinates 728 Chapter10 10 Conics, Conics,Parametric ParametricEquations, Equations,and andPolar PolarCoordinates Coordinates 728 Chapter 10 Conics, Parametric Equations, and Polar Coordinates 728 Chapter 10 Conics, Parametric Equations, and Polar Coordinates Arc Length In Exercises 45– 48, write an integral that repre63. Descartes ConsiderConsiderar the parametric equations paraLongitud de arco En los ejercicios 45 a 48, dar una integral que 63. Folium Hoja (ooffolio) de Descartes las ecuaciones Arcthe Length In Exercises 45– 48, write an integral that repre63. Folium of Descartes Consider the parametric equations sents arc of de the curve the given Dodado. notConsider the represente la length longitud arco de on la 63. curva en elinterval. intervalo métricas In Exercises 45– 48,Arc write an integral that repreFolium of Descartes parametric equations Length In Exercises 48, write integral that repreFolium 4t of Descartes Consider parametric equations 4t2 2 2the sents the length of 45– the curve on an the given interval. Do not 63. Arc Length In 45– 48, write an that repre63. of Descartes evaluate thelaarc integral. Arc Length In Exercises 45– 48, write an integral that repre63. Folium of Descartes Consider the parametric equations No evaluar integral. and y Consider c length of the curvesents on the given interval. Do curve not Arc Length InExercises Exercises 45– 48, write anintegral integral that repre63.xFolium Folium4t of Descartes Consider theparametric parametricequations equations 4t 4t3 . the 4t Arc Length In Exercises 45– 48, write an integral that repre63. Folium of Descartes Consider the parametric equations 3 Descartes 2 Arc Length In Exercises 45– 48, write an integral that repre63. Folium of Consider the the arc length of the on the given interval. Do not evaluate thelength integral. 4t 4t x5 y 5 y 14t 2 3t. 3 . parametric equations x 1 4t t 3 3 y and sents the arc of the curve on the given interval. Do not sents the arc length of the curve on the given interval. Do not integral. sents the arc length of the curve on the given interval. Do not 2 x y . and 1 1 t 1 1 t sents the arc length of the curve on the given interval. Do not 1 t 1 t 2 sents the length of the curve on theIntervalo given Do not1 t 3 x 4t 4t evaluate thearc integral. 4t 2232. 4t4t3 and y Parametric Equations Interval 1 interval. t3 Ecuaciones paramétricas evaluate the yyyy 1 to4t4t xxxx 1Use4t ... . the curve represented by the evaluate the integral. tgraph and evaluate theintegral. integral. and utility evaluate the integral. (a) at tuna graphing 33 3 and Parametric Equations Interval and evaluate the integral. 3. a) Usar herramienta de pararepresented trazar la curva 1 1 tt3333tgraficación y x and 3 1 t 1 2 3 2 1 t 1 ric Equations Interval 3a graphing utility (a) Use to graph the curve by the 1 t 3 45. Parametric x 3t t Equations , 2 y 2t 3 2 1 t 1 t 45. Interval parametric equations. (a) Useta graphing utility to graph(a) the Use curve represented by the descrita por las ecuaciones paramétricas. Parametric Equations Interval y 2t 1 3 45. x 3t t , Parametric Equations Interval a graphing utility to graph the curve represented by the 2 3 2 Parametric Equations Interval Parametric Equations Interval parametric equations. 1 t 3 t , y 2t Parametric Equations Interval 2 3 2 (a) Use a graphing utility to graph the curve represented by 1 x ln t, y 4t 3 t 5 46. (a) Use utility to graph curve represented by the equations. Useaaauna agraphing utility graph the curve represented bythe the 1 tparametric 3 45. x 3t t ,22 2 y 2t 33 322 2 46. (a) Use graphing utility to graph the curve represented by the (b) Use graphing utility to findthe the points oflos horizontal (a) Use graphing utility totograficación graph the curve represented by the b)(a) Usar herramienta de para hallar puntos de parametric equations. 1111 1 ttt t t 3333 5 45. xxxx x 3t ln t,ttt 22t,,, ,yyyyy 4t2t 3 46. 3 2 2t 45. 3t 2t 45. 3t 3 2 2t 45. 3t parametric equations. (b) Use a graphing utility to find the points of horizontal t parametric equations. y 4t 3 1 t 5 12 tUse t t 5a32graphing utility to find thetangencia 45.xxx lne3tt, 2, t , y4ty 2t32t 1 parametric equations. 47. parametric equations. tangency to the curve. (b) points of horizontal y 1 46. parametric equations. horizontal a la curva. 47. t (b) Use a graphing utility to find the points of horizontal xxxx x ln y 2, 4t 1111 2ttt t 5t555 2 46. y4t 32t 47. tangency to theutility curve.to ln 33 1 46. 46. lnlnt,et, t, 4t 46. (b) Use aaaagraphing find of horizontal (b) Use graphing utility to find the points of horizontal t yyyyyt,2 4t 2, y 2t 1 t,t, 4t 46. Usethe graphing utility findthe the points horizontal 012 tangency sen y2t t33 1 cos t ttt 52 to the curve. 48. (b) Use utility to the points of (c) Use integration capabilities of apoints graphing utility tode c)(b) Usar las funciones de integración de una herramienta xxx e2tln 47. (b) Use a graphing graphing utility toto find find the points ofof horizontal horizontal tangency to the curve. t t t 2, 48. x e y 2t 1 2 t 2 2, 47. x t sen t, y t cos t 0 t 48. t tangency to the curve. (c) Use the integration capabilities of a loop. graphing utility to x e y 2t 1 2 t 2 2, 47. tangency to the curve. x e y 2t 1 2 t 2 2, 47. t tangency to the curve. x e y 2t 1 2 t 2 2, 47. tangency to the curve. approximate arc length of the closed Hint: Use sen t, y t cos t48. 0 t graficación para aproximar la longitud de arco del lazo cer1 t t the2 integration capabilities 47.x x t e sen2,t, y y 2tt cos (c)2 Use of a graphing utility to tangency to the curve. 0 t (c) Use the integration capabilities of a graphing utility to approximate the arc length of the closed loop. Hint: Use Arc Length In Exercises 49–56, find the arc length of the curve xxxx ttt t sen t,t, yyyy ttt t cos 0000 approximate ttt t 48. (c) Use capabilities of utility to sen cos 48. 0graphing tsobre 1.utility symmetry and integrate over the interval (c) Use the integration capabilities of aaagraphing graphing utility to senIn costttt t find the 48. rado. (Sugerencia: Usar la of simetría e aintegrar elUse interlength of the closed loop. Hint: Use (c) Usethe theintegration integration capabilities sen t,t,Exercises cos 48. (c) Use the integration capabilities ofof graphing utility toto x Length tde arco sen t, y los tejercicios cos 0 hallar t length 48. Arc 49–56, arc ofthe thearc curve (c) Use the integration capabilities of a graphing utility to approximate the arcintegrate length thethe closed loop. Longitud Enthe 49 a 56, la longitud de 0 Hint: tHint: 1.Use symmetry and over interval on the interval. In Exercises 49–56,Arc find thegiven arc length of curve approximate the arc length of the closed loop. Hint: approximate the arc length of the closed loop. Use valo 0 t 1. symmetry and integrate over the interval approximate the arc length of the closed loop. Hint: Use Length In Exercises 49–56, find the arc length of the curve approximate the arc length of the closed loop. Hint: Use 64. Witch of Agnesi Consider the the parametric equations onLength thelagiven interval. approximate arc length of the closed Hint: Use 0 loop. t 1. symmetry and the integrate over interval arco de curva en el intervalo dado. Arc In 49–56, find the Arc Length In Exercises 49–56, find the arc length of the curve interval. Arc Length InExercises Exercises 49–56, findthe thearc arclength lengthof thecurve curve 000equations ttt t 1. symmetry and over interval 64. Witch of Agnesi Consider thethe parametric Length In Exercises 49–56, find the arc length of curve 1. symmetry and integrate over the interval 0ecuaciones symmetry andintegrate integrate over the interval Arc Length In Exercises 49–56, find the arc length ofofthe the curve 1.1. onArc theParametric given interval. symmetry and integrate over the interval Equations Interval 64. Witch of Agnesi Consider the parametric equations 64. Hechicera o bruja de Agnesi Considerar las 0 t symmetry and integrate over the interval on the given interval. 64. Witch of Agnesi Consider the parametric equations 1. paraon the given interval. onthe theParametric giveninterval. interval. on given Equations Interval 2 parametric 64. Witch of Agnesi Consider the equations on the given interval. 64. Witch of Agnesi Consider the parametric equations x 4 cot , y 4 sin . and métricas 64. Witch of Agnesi Consider the parametric equations ric Equations Interval 64. Witch Witch of of Agnesi Agnesi Consider Consider the 2parametric parametric equations equations xEcuaciones 3t 5,Equations y 7 2t 1 t 3 49. Parametric 64. paramétricas Intervalo Interval 2 . x 4 cot sin , 2 and y 4 the Parametric Interval x 2 3t Equations 5, y 7 2t 14 cott 3and y 4 sin2 , 49. Parametric Equations Interval xInterval . Parametric Equations 2 2 u, Parametric Equations Interval 2 5, y 7 2t 1 t 3 x 4 cot y 4 sin . 2 and Parametric Equations Interval sen y x 5 4 cot u y 5 4 sin u y y2t 7 2t 01 t t 23 50. xx 3tt , 25, 22, 2 2 2 49. xxxx Use 4444cot ,,, , the yyyy 444to sin .. and 2 2 2 cot sin and cot 4 sin and (a) a graphing utility graph curve represented by the 2 x 3t 5, y 7 2t 1 t 3 49. x t , y 2t 0 t 2 50. cot sin and 5, 111 t t 333 49. 2the 2222.. . y 3 7777 2t 49. xxxx0 23t x (a)4 Use cot a graphing , 4 sinto graph and y utility 3t3t 5, 2t 49. 222 curve 2 y 2t 25,2tyyy2t 2t2t 3 49. represented by the 51. a) curve Emplear una herramienta de graficación para 2 2 trazar la curva xx t 6t3t ,22t2, y 2 y5, 01(a)1t tUset24a graphing 50. parametric equations. 3 utility to graph the represented by the xxxx x ttt222t,,,6t 0000 1 ttt t t 2222 4 50. 2t 3 51. 2t 50. (a) Use a graphing utility to graph the curve represented by the , yyyy,4y y2t 2t 50. parametric equations. 2t 50. descrita por las ecuaciones paramétricas. 1 t y 2t3 x t , 2t 0 t 2 50. 2 3 (a) Use a graphing utility to graph the curve represented by t 4 0 equations. 52. xx 6tt ,2 2 y1, y2t 34t 3 3 (a) Use utility graph curve represented by the (a) Useaaaagraphing utility graph the curve represented bythe the 1 1 t parametric 51. (a) Use graphing utility to graph the curve represented by the (b) Use graphing utilityto findthe the points of horizontal 2 (a) Use graphing utility tototo graph the curve represented by the parametric equations. 1111 t1tt t 444t 4 0 xxxx x 6t 51. 1, 2t y2t333 3 4t 3 52. 2t,,,2, yy 6t y 2t 51. 3 6t y 51. 2 parametric equations. (b) Use a graphing utility to find the points of horizontal 6t 2t 51. b) Utilizar una herramienta de graficación para hallar los punparametric equations. 1 1, y 4t 3 parametric equations. x 1 t 4 51. 26t ,t y 0 2t 3 parametric equations. tangency to the curve. points ofequations. horizontal xx t e22t2 cos 1 tUse t a0 graphing utility to find 1, t,y y 4t 3e3 3 t 3sen t 52. parametric (b) the Use a tangencia graphing utility find the points of horizontal 0(b) 53. 1111 ttt t 0000 52. tangency to the curve.toto tos de horizontal a find la curva. x tt 2 1, 1,1, yyyy 4t 4t4t33 333t3 52. 52. (b) Use utility of 52. (b) Use aaagraphing graphing utility to the points of horizontal (b) Useathe graphing utility findthe the horizontal cosyt, 4t y e 3 sen t 53.xxx x tt 2t e t1, 10 tangency t 2 0 to the curve. 1, 4t 52. (b) Use graphing utility totofind find the points ofofhorizontal horizontal (c) Use integration capabilities of points apoints graphing utility t (b) Use a graphing utility to find the points of horizontal tangency to the curve. cos t, y e sen t 53. x 0 e t tcos t, y e t sen t 2 1 c) Usar las funciones de integración de una herramienta de tangency to the curve. (c) Use the integration capabilities of a graphing utility 0 t tangency to the curve. 2 tangency to the curve. t t 2 tangency to the curve. t t to approximate the arc length over the interval tUse xxxx5 arcsen 1tsen 54. tcost,t, integration capabilities of a graphing utility ee2t cos t,t,t, yyyyy5 ln ee2t sen ttt t 2 00(c) 53. tangency to the curve. ttcos ttsen 2 the 2 t 53. 1 e e sin t 53. e cos e sen 0 t 53. (c) Use the integration capabilities of a graphing utility x e cos t, y e sen t 0 t 53. graficación para aproximar la longitud de arco en el intervato approximate the arc length over the interval 2 0 t x arcsen t, y ln 1 t 54. 1 2 2 (c) Use the integration capabilities of aaaagraphing utility 4over 2. (c) Use the integration capabilities of graphing utility 1 12 the arc length interval (c) Use thethe integration capabilities graphing utility tt, t,y2 y3t ln1 1 t 2 en t, y ln 1 t54. 222 (c) Use the integration capabilities ofof graphing utility 55. xx 0 arcsen (c) integration capabilities a graphing utility toloUse approximate the arc length of over the interval 00 t tto 2approximate 11 1 4the 2.the 22 2 11 1 to approximate arc length over the interval 0 t x arcsen t, y ln 1 t 54. x t, y 3t 1 0 t 55. 2 2 to approximate the arc length over the interval 0 t x arcsen t, y ln 1 t 54. 4 2. to approximate the arc length over the interval 2 0 t x arcsen t, y ln 1 t 54. ! arcsin t,t, 1 2 t 54. 2 arcsen to approximate the arc length over the interval 22 2 arcsen t,t 5y yy5 ln ln 1 t 54. xxx 5 65. Writing 0 t y 3t 1 0 t 1 to approximate the arc length over the interval arcsen ln 1 t 54. 4 2. xx t, t, y y 3t 5 11 0 t t 122 55. 65.65.Redacción 444 2. Writing 2.2. 56. 3t 55. t3t2 1131111 t,t, yyyyy5 3t 55. 65. 1000Writing 0 1 tt t t 1111 2 55. 2.utility to graph each set of parametric (a) Use44 a graphing2. xxxx5x !t,t,t, 55. 3t 55. 10 6t 3 1 t5 56. 65. Writing 5 3t t 55 510 1 6t 65. Writing (a) Use a graphing utility to graph each set of parametric a) Usar una herramienta de graficación para representar cada y 1 t 2 65. Writing 65. Writing 1 t 3 65. Writing 5 equations. x t, y 1 t 2 56. 1 t 5 (a) Use a graphing utility to graph each set of parametric 1 t 65. Writing 10 6t xxxx5 t,t,t, yyyy510ttt 5 16t131133 1111 ttt t 2222 56. (a) Use a graphing utility to graph each set of parametric 56. equations. conjunto de ecuaciones paramétricas. t, 56. t, 56. x y 56. (a) Use a graphing utility to graph each set of parametric Arc Length In Exercises 57– 60, find the arc length of the curve 3 10 6t 1 equations. t 2 56. x t, y 10 (a) Use parametric 10 6t (a) Use aaaa graphing graphing utility utility to to graph graph each each set set of parametric 33 10 (a) utility each set of 3 6t 6t6t (a) Use graphing utility to graph each set ofof parametric parametric equations. xUse t graphing sin t x to 2t graph sin 2t Length In10 equations. [0, ]. curve57– 60, find the arc length of the curve 2Exercises on Arc the interval equations. In Exercises 57– 60,Arc find the arc length of the equations. sen x t sin t x 2t sin 2t x 5 t 2 sin t x 5 2t 2 sin s 2t d equations. sen Length In Exercises 60, find the arc length thetcurve x 2t sin 2tequations. [0, 2 ].57– on the interval xlength t ofof sin cos cos 2t 2t Arc Length In Exercises 57– 60, the Arc Length In Exercises 57– 60, find the arc length of the curve al [0, 2 ]. xy t 1 sin t t xy 2t1 sin Arc Length 57– 60,find find thearc arc length ofthe thecurve curve Arc Length In 57– 60, find arc length of the curve 3 the 3 Arc Length In Exercises 57– 60, find the arc length of the curve [In ].].los ejercicios 0,Exercises 2Exercises on the interval ttt tt t xxxyx5 y ttt1t 2 1 sin y 2t 1 sin cos cos 12t2 cos s2t 2t d2t x a cos , y a sin 57. Hypocycloid perimeter: sin 2t sin Longitud de arco En 57 a 60, hallar la longitud de y 1 cos 2txxxxyx5 sincos sin sin 2t sin 2t [ 0, 2 on the interval 3 , y y a1 3 cos t [ ] 0, 2perimeter: .]. on the interval t sin t x 2t sin 2t2t [ 0, 2 on the interval [ ] 0, 2 . on the interval x a cos sin 57. Hypocycloid 0 t 2 0 t y 1 cos t y 1 cos 2t [ ] 0, 2 . on the interval 3 3 arco de curva en el intervalo [cos 0, 23p cos , y la circumference: a sin perimeter: loid perimeter: x a57. yyy0y 0≤ 111t1 ≤ cos yyy0y 0≤ 111t1 ≤ cos xx aacos ,3y],. y a sin 58. Hypocycloid Circle cos cos 2t 2cos p2tttt t pcos2t a sin 3 t33 3 2 cos cos 2t2t y 1 t cos y 1 t cos 2t 0 t 57. Hypocycloid perimeter: cos 58. Circle circumference: cos sin 57. Hypocycloid perimeter: cos333 3 ,,,,y,yyyy 0aaaaasin sin33 57. Hypocycloid perimeter:xxxxxx aaaaaacos 0 t 2 0 t cos sin 57. Hypocycloid perimeter: (b) Compare the graphs of the two sets of parametric , y a sin rcumference: x a cos cos sin 57. Hypocycloid perimeter: x hipocicloide: a x sin 59. Circle Cycloid arch: 3 u,cos 3u 0000Compare ttt t 222las 0 t b) (b) Comparar gráficas de los dos conjuntos de equations ecuaciones 0 t a cos ,xy,5y aacos a1 sin 58. circumference: sen 57. y 5 a sin Perímetro de una 000of tt t two sets graphs the of parametric equations 0 parametric t (a).22Ifthe cos ,,, y,yyy (b)aaaasin 58. Circle circumference: 1Compare cos the graphs of the two sets of 59. Cycloid arch: x axxxx aaaasin cos sin 58. Circle circumference: in part the curve represents the motion of a particle cos sin 58. Circle circumference: equations cos sin 58. Circle circumference: sin 59. ,58. y Cycloid a 1 circumference: cos arch: x a paramétricas del inciso a). Si la curva representa mox a cos , y a sin Circle x cos sin , y sin cos 60. Involute of a circle: (b) Compare the graphs of the two sets of parametric equations in part (a). If the curve represents the motion of aelparticle sin x, y5 a acos 1 u, ycos arch: x de aun círculo: sen 58. Circunferencia 5 a sin u (b) Compare the graphs of the two sets of parametric equations and what can you about the average speeds t is time, (b) Compare the of the two sets ofofparametric equations aaa x sin 59. Cycloid arch: cos ,,, y,yyy aaasin ycos 60. Involute of xaxxxcircle: part (a). If the cos curve represents the motion agraphs particle (b) Compare the graphs the two sets parametric equations 59. Cycloid arch: (b) Compare the graphs of the two sets parametric sin a1111 in, cos cos sin 59. Cycloid arch: vimiento de una partícula yyou tinfer esinfer tiempo, ¿qué puede inferirse (b) Compare the graphs ofof the two sets of parametric equations in part (a). Ifof the curve represents theof motion ofaverage a equations particle a cos sin sin cos 59. Cycloid arch: sin , y sin of a circle: x cos 60. and is time, what can about the speeds t in part (a). IfIf curve represents the motion of aaaparticle x x cos sinud,, yy and Involute a circle: of the particle on the paths represented by the two sets oflas in part (a). the curve represents the motion of particle is2time, the average speeds part (a). Ifthe the curve represents the motion particle 5cos asu 2 sin 5 sin astsin 1modeled cos cos uwhat dcosthecan you infer about 59. Arco deof sen in (a). If the curve represents the motion of particle acerca de las velocidades promedio de laaverage partícula en sin cos 60. Involute of aaacicloide: 61. of auna Projectile path by ininof part (a). Ifwhat the curve represents the motion ofofaatwo particle sin 60. Involute of circle: and isthe time, can you infer about the speeds tpart cos of a projectile sin ,,,, y,yyyy issin sin cos 60.Path Involute acircle: circle:xxxxxThecos particle on the paths represented by the sets of cos sin sin cos 60. Involute of circle: cos sin sin cos 60. Involute ofof aProjectile circle: and is time, what can you infer about the average speeds t parametric equations? 61. Path of a The path of a projectile is modeled by the and is time, what can you infer about the average speeds t of the particle on the paths represented two sets of you and isthe time, what can you infer about the average speeds tis and time, what can infer the average ttby trayectorias representadas por losabout dos by conjuntos despeeds ecuaparametric equations and is time, what can you infer about the average speeds 60. Evolvente o involuta de un círculo: Projectile The path61. of aPath projectile is modeled by the of the particle on the paths represented the two sets of parametric equations? of a Projectile The path of a projectile is modeled by the of the on the paths represented two of parametric equations of the particle on the paths represented by the two sets of equations? theparticle particle on the pathsdetermine represented bythe the twosets sets of particle on the paths represented by the two sets of (c) parametric Without graphing the curve, theby time required for 61. of path isis by ciones paramétricas? 61. Path of aauaProjectile Projectile The path of projectile modeled by the ofofthe the particle on the paths represented by the two sets ofof xPath 5 cos 1 u sin u, yThe 5 sin u of 2 uaprojectile cos u parametric ic equations equations? 61. Path Projectile The path projectile ismodeled modeled bythe the 61. Path ofofacos Projectile The path ofofaaaasin projectile is16t modeled by the 2 61. Path of a equations Projectile path of projectile modeled by the parametric parametric equations? ysen 90 30 t is xparametric 90 30 sen t andThe (c) Without graphing the curve, determine the time required for parametric equations? parametric equations? parametric equations? a particle to traverse the same path as in parts (a) and (b) if equations 2 (c)30 Without graphing the curve, determine the time required for parametric equations parametric equations? parametric equations c) Without Sin trazar la curva, determinar el tiempo que requiere laif x 90 cos 30 t and y 90 sin t 16t parametric equations (c) graphing the curve, determine the time required for 2 parametric equations a particle to traverse the same path as in parts (a) and (b) cos 30 t and y 90 sin 3090tcos 16t 2 to traverse the same path (c) Without graphing the determine the required the is modeled bycurve, (c) Without graphing the curve, determine the time required for as inpath parts (a) and (b) 30 t measured y in90 sin 30 t a particle 16tun and (c) Without graphing the curve, determine thetime time required for 61. xTrayectoria de un proyectil trayectoria (c) Without graphing the determine time para recorrer las mismas que(b) enfor los x and y30are where feet. 2 proyectil se (c) Without graphing the curve, determine the time required for apartícula particle to traverse theifcurve, same path as trayectorias in the parts (a)required and iffor xxx where 90 30 yyy La 90 sin 30 tt t de16t and the path istraverse modeled by 90 cos 90 sin 30 16t and 90cos 30ytttare t de 90 sin 30the 16t222is2 modeled by and a particle to the same path as in parts (a) and (b) ifif xcos and measured in feet. x 90 cos 30 y 90 sin 30 t path 16t and a particle to traverse the same path as in parts (a) and (b) a particle to traverse the same path as in parts (a) and (b) 1 1 1 describe por medio las ecuaciones paramétricas aa particle to the same path as in parts and (b) if incisos a) ysin b)traverse si la and trayectoria está descrita por(a) and y are measured in feet.where particle to traverse the same path as in parts (a) and (b) ifif the path is modeled by y 1 cos x t t t . (a) Use a graphing utility to graph the path of the projectile. 2 1is 2 1 by 2 1 x and y are measured in feet. the path modeled the path is modeled by 1 1 1 the path is modeled by x y where and are measured in feet. and y 1 cos x t sin t t . (a) Use a graphing utility to graph the path of the projectile. the path is modeled by 2 1 1 1 yyyprojectile. and are feet. where and measured feet. the modeled where and measured in feet. xwhere 5path s90xxxxcos 308 dare t measured yin 5approximate s90 sen sin 308d t 22t 16t y x 51path t 22issen sin 1 s2 td2 yby y 5 1 2 coss 21t d. 2 and y 1 xcos sin of a graphing utility to graph(a) the the y are where and are measured inin feet. (b) Use agraphing graphing utility to range 2 t the 2 t2 . y 1 cos 2t111 .1 Use aof utility to graph the path xof the the projectile. 66. Writing 2 t111t1 sin 2 t111 1 and x sin (a) Use a graphing utility to graph the path of the projectile. (b) Use a graphing utility to approximate the range of the and cos x t sin (a) Use a graphing utility to graph the path of the projectile. 1 2 cos2122tttt2t.... . and yyyyy 11111 cos x t sin (a) Use a graphing utility to graph the path of the projectile. and cos sin 2122tttt2t and (a) projectile. Use graphing utility to graph graph the the path path of of the the projectile. projectile. 66.66.Redacción Writing a graphing utility to approximate ofenthe x ayaathe ygraphing serange midenutility pies. donde and cos xx 222tt2 sin (a) Use to 2 2 the motion of a 66. Writing (b) Use graphing utility to approximate the range of the (a) Each set of parametric equations represents projectile. 66. Writing (b) Use a graphing utility to approximate the range of the (b) Use graphing utility to approximate approximate the range ofof the the ctile. (b) Usethe graphing utility approximate the range the a) Cada conjunto de ecuaciones paramétricas representa el mo66. Writing (a) Each set ofa parametric equations represents the motion of a (c) Use integration capabilities of a para graphing utility to (b) Use aaauna graphing utility the range of 66. Writing a) Utilizar herramienta detotograficación trazar la trayecprojectile. 66. Writing particle. Use graphing utility to graph each set. 66. Writing (a)ofEach set of parametric represents theparametric motion of equations a projectile. (c) Use the integration capabilities a graphing utility toequations projectile. (a) Each set of represents the motion of a projectile. projectile. vimiento de una partícula. Usar una herramienta de grafiparticle. Use a graphing utility to graph each set. approximate the arc length of the path. Compare this result the integration capabilities of a graphing utility to projectile. toria the del proyectil. (a) Each set of equations represents the a (a) Each set of parametric equations represents the motion of particle. Use athis graphing utility to graph each set. (c) Use integration capabilities apath. graphing utility to (a) Each set ofparametric parametric equations represents themotion motionof Second First Particle approximate arc length of of the Compare result (a) Each set of represents the motion ofofaaa particle. Use aparametric graphing equations utility toParticle graph each set. (c) Use the integration capabilities of utility to cación para representar cada conjunto. with range ofthe the projectile. (c) Use the integration capabilities of graphing utility to oximate the arc length of the path. Compare this result (c) Use the integration capabilities ofaaaaCompare agraphing graphing utility to (c) Use the integration capabilities of graphing utility to particle. Use a graphing utility to graph each set. Second Particle First Particle particle. Use a graphing utility to graph each set. (c) Use the integration capabilities of graphing utility to approximate the arc length of the path. this result particle. Use a graphing utility to graph each set. b) Utilizar una herramienta de graficación para estimar el particle. Use a graphing utility to graph each set. with the range of length the projectile. Second Particle First Particle tot graph each set. xparticle. 3 cosUse t a graphing x utility 4 sin approximate the arc Compare this result approximate the arc length of the path. Compare this result Second Particle the range of the projectile. First Particle approximate thethe arcprojectile. length ofthe thepath. path. Compare this61 result approximate the arc length of the path. Compare this result 62. Path ofthea del Projectile If the of projectile in Exercise is approximate the arc length of the path. Compare this result with range of alcance proyectil. Second First x Particle 3 cos t x 4Particle sin t Second Particle First Particle Primera partícula Segunda partícula First Particle Second Particle Second Particle First Particle with the range of the projectile. 62. Path of a Projectile If the projectile in Exercise 61 is x 3 cos t x 4 sin t with the range of the projectile. Second Particle First Particle with the range theis projectile. sintt cos with range of the projectile. launched at an angle with the horizontal, its parametric xy 34cos xy 43sin tt a Projectile If the62.projectile inathe Exercise with the range ofof61 the projectile. Path of Projectile If the projectile in Exercise 61 is x 3 cos t x 4 sin t y 4 sin t y 3 cos c) Utilizaraare las funciones de the integración de in unaExercise herramienta de launched at an angleIfIf withprojectile the horizontal, x 33cos xx5 44sen sin costtt t sinttt t t cos sin Path Projectile 61 equations y in 4Exercise sinitst parametric 62. Path of Projectile projectile 61 cos sin at an angle with 62. the horizontal, its parametric 62. Pathof ofataaaaan Projectile If the the projectile in its Exercise 61isis is y 3 cos t y0xxx54t33sin 2 0xx 3t44cos 2t 62. Path of Projectile If the projectile in Exercise 61 is t y 62. Path of Projectile If the projectile in Exercise 61 is launched angle with the horizontal, parametric graficación para aproximar la longitud de arco de la trayecequations yyyy5 yyyy5 0 4444sin tsinttt t 2 0 3333cos tcosttt t2 launched at an angle with the horizontal, its parametric sin cos launched atatare an angle with the horizontal, its parametric sen s are launched an angle with the horizontal, its parametric sin cos launched at an angle with the horizontal, its parametric 2 0 t 2 0 t 2 y 4 sin t y 3 cos launched at an with the its proyectil. parametric (b) 0Determine equations are xequations 90 cos t angle 90 sin tel alcance 16t . 2del and toria. Comparar este yresultado conhorizontal, t 2 the number0of points t 2oftintersection. equations are 0000Determine ttt t 2222 the number 0000of tpoints equations are t and y x 902are cos 90 sin(b)t Determine 16t . the number of points of(b) t t 2222of intersection. equations are equations are intersection. 0 the t particles 2 number 0points cos t and y 9062. sinxTrayectoria t 9016t (c) Determine Will everofbe attt the place at the same 2del ejercicio 61 se (b) the of2same intersection. proyectil el proyectil cos . det un y to find 90Sisin t 16t .22 2maximizes the and Use a graphing utility the angle that (b) Determine the number of points intersection. (c) WillIf the particles ever be at of the same place at the same xxx Use 90 cos tt t and yyy to 90 sin t(c) 16t ..the (b) Determine the number of points of intersection. 2 90 cos 90 sin t 16t and (b) Determine the number of points of intersection. 90 cos 90 sin t 16t . and (b) Determine the number of points of intersection. time? so, identify the point(s). 2 a graphing utility find the angle that maximizes the Will particles ever be at the same place at the same b) Determinar el número de puntos de intersección. x 90 cos t y 90 sin t 16t . and (b) Determine the number of points of intersection. lanza formando un ángulo con lamaximizes horizontal,thesus range ofthat the maximizes projectile. Whatu angle arcecuaciones length of (c) Willtime? the particles ever be atpoint(s). the same place at the same raphing utility to find theUse angle If so, identify the (c) Will the particles ever be atat the same place atatatthe same a graphing utility totheWhat find the angle that maximizes the the (c) Will the particles ever be atat the same place the same range of the projectile. angle maximizes length of point(s).(d) time? Ifthe so,arc identify (c) WillIf the particles ever be the same place the same paramétricas son (c) Will the particles ever be the same place the same Explain what happens if the motion of the particle c) ¿Estarán las partículas en algún momento ensecond el at mismo lugar Use a graphing utility to find the angle that maximizes the (c) Will the particles ever be at the same place at the same the trajectory? time? so, identify the point(s). Use a graphing utility to find the angle that maximizes the the projectile. What anglerange maximizes the arc length of Use a graphing utility to find the angle that maximizes the Use a graphing utility to find the angle that maximizes the time? If so, identify the point(s). Use a graphing utility to find the angle that maximizes the (d) Explain what happens if the motion of the second particle of the projectile. What angle maximizes the arc length of time? If so, identify the point(s). the trajectory? time? If so, identify the point(s). is represented by 2 time? If so, identify the point(s). al mismo tiempo? Si es así, identificar esos puntos. range of the projectile. What angle maximizes the arc length of what happens of the what second particle range ofof the projectile. What angle maximizes the arc length ofof if the motion sen xrange 5trajectory? s90of dprojectile. t y y5 s90 angle sin udmaximizes t maximizes 2(d)16tExplain . the ctory? range theuprojectile. What angle thearc arclength length the What of (d) Explain happens motion of the second particle range ofcos the projectile. What angle maximizes the arc length of is represented by ifififthe the (d) Explain happens the second (d) what happens the motion of the second particle the trajectory? is represented by (d) Explain the motion the second particle the trajectory? (d) Explain what happens if the motion of the second particle d) Explicar qué ocurre de la partícuxExplain 2 what 3what sin t,happens y si elif 2ifmovimiento 4motion cos t, of tsegunda 2 . particle 0ofthe the trajectory? (d) Explain what happens the motion of the second particle is represented by the trajectory? Usar una herramienta de graficación para hallar el ángulo que is represented by x 2 3 sin t, y 2 4 cos t, 0 t 2 . is represented by is represented by is represented by la se representa por 2 maximiza 3 sin t, yla 2 4 cos t,x is 0represented 2 t,.by y 2 4 cos t, 0 t 2 . maximiza el alcance del proyectil. ¿Qué xángulo 2 t 3 sin xxxx 2222 3333sin sin cos sint,t, cost,t, 2 ..... . sin t,t,t, yyyyy5 222222 44444cos cos t,t, 00000# tttt t# 22222p longitud de arco de la trayectoria? x 5 2 1 3 sin t, cos t, sen hapter 10 1059997_1003.qxp 9/2/08 3:50 PM Page 729 10-3.qxd 3/12/09 16:47 Page 729 1059997_1003.qxp 9/2/08 3:50 PM Page 729 1059997_1003.qxp 9/2/08 3:50 1059997_1003.qxp PM Page 729 9/2/08 3:50 PM Page 729 SECCIÓN 10.3 Parametric Ecuaciones paramétricas y cálculo 729 10.3 Equations and Calculus 729 10.3 Parametric Equations and Calculus 729 10.3 Parametric Equations and 10.3 CalculusParametric 729Equations and Calcul Área de una superficie En los ejercicios 67 a 70, una inte84. de una deradius una esfera de radiobyr Surface Area In Exercises 67–70, write an dar integral that 84. Área Surface Areasuperficie A portionUna of a porción sphere of r is removed gral que represente el área la67–70, superficie generada por revolusecutting elimina un cone cono circular vértice el centro de represents area of thedesurface generated revolving the outcortando a circular its con vertex at rthe center ofby the Surface Areathe In Exercises write anbyintegral that 84. Surface Area A portion of awith sphere of radius isenremoved Surface Area In Exercises 67–70, Surface writeuna Area anherramienta integral In Exercises that 67–70, 84. Surface write an Area integral A portion that of aforma sphere 84. un Surface ofángulo radiusArea removed A portion by of a sphere of radius r ruis. Hallar ción de la curva alrededor del eje la esfera. El vértice del cono 2 x. Usar de el área curve about x-axis. a graphing utility approximate sphere.out The vertex ofcone the cone forms an angle the 2 . Find represents the the area of theUse surface generated by to revolving the cutting a circular with its vertex at the of center of the represents the area of the surface represents generated the by revolving area of the thesurface generated cutting out by arevolving circular cone the with its vertex cuttingatout the acenter circular of cone the with its vertex at the graficación de superficie eliminada decone la esfera. the integral. surface areavertex removed from the sphere. curve aboutpara the aproximar x-axis. Use laa integral. graphing utility to approximate sphere. The of the forms an angle of 2 . Find the curve about the x-axis. Use a graphing curve utility about to theapproximate x-axis. Use a graphing sphere. utilityThe to vertex approximate of the cone formssphere. an angle The of vertex of the cone forms an angle o 2 . Find the integral. 1059997_1003.qxp 9/2/08 3:50 PM Page 729surface area removed from the sphere. Ecuaciones Intervalo the integral. the integral. surface area removed from the sphere. surface area removed from Parametricparamétricas Equations Interval Area In Exercises 85 and 86, find the area of the region. (Use the sphere. Área En los ejercicios 85 y hallar el área de la región. (Usar 67. t1 22 0Interval #t# 4 4 Parametric Equations the result of Exercise 83.) 67.xParametric x5 4t,3t, y y5 t 0 t Area In Exercises 85 and 86, find the area of the region. (Use el resultado del ejercicio 83.) Equations Parametric IntervalEquations Area In Interval Exercises 85 and 86, findArea the area In of Exercises the region. 85 and (Use86, find the area of the the result of Exercise 83.) 67. x 13t,12 2 y t 2 0 t 4 2 2 2 the result of Exercise 83.) thexxresult ofuExercise 83.) 85. xx5 202sin 86. sintu 4 cot 67. 67. x 03t,0# tyt # 68. 85. 86. 5 22cot sen t 23 3 t 34t 3 2 68.x x5 43t,t ,t ,yy y5t t 1 14 2 2 85. x 2 sin 86. xyy5 222cot 222u2 sin tanu sin 10 2 t 3 222u tan sen 68. x 1 t 2, y t 3 sin sen 85. xyy52202sin 86.85. 86. x 2 cot x x 2 cot 2sin sin 0t , t y 3pt 3 t 3 68. x 4 t 22, y t 3 68. x 4 cosu2 , , y y5 cos 69. 04 0≤ u ≤ y 2 sin22 tan y 2 sin22 2 cosu 69.x x5 cos y 2 sin y 2 sin2 y 2 sin tan y 2 sin tan 22 0 < 00 << u << p 2 0 2 69. x cos22 , y cos Parametric Equations and Calcul 0 0< , yp2 cos 69. x cos , y cos 69. x cos 0 0 < 10.3 < 0 < 2 yy 2 0 <0 < < y y 0 < < sinsinu, , y y5 u 1 cos 0 0≤ u ≤ 2 70. cosu 70.x x5 u 1 sen 2 2 22 y y sin , y cos 0 70. x y y y sin , y cos 70. x 0 sin , 2 y cos 0 22y 70. x 2 2 Surface Area In Exercises 67–70, write an integral that 84. Surface Area A portion of a sphere of radius r Surface Area In Exercises 71–76, find the the surface Área de una superficie En los ejercicios 71 aarea 76, of encontrar el 2 211 revolving the 112 a circular cone with its vertex at the represents the of the surface generated by cutting out generated by revolving the 71–76, curve about each given axis. Surface Area In Exercises find the area the surface área de la superficie generada por revolución de laofarea curva alredeSurface Area In Exercises 71–76, curve Surface find the Area area of In the Exercises surface 71–76, find the area of the surface 1 about theaxis. x-axis. Use a graphing utility 1to approximatex x sphere. 11The vertex of the cone forms an angle o generated revolving the curve given dor de cadabyuno de los ejes dados.about each 1 x 1 generated by revolving generated eacha)given by each given axis. y 3t, the 0 curve t 3,about eje ycurve about −2 71. x 2t, ejerevolving x axis. b) the −2 −1 − 1 area removed −2 −1 −1 the integral. surface 11 2 2 x −2 11 22 from the sphere. x x −1 −1 71. a) eje b)b)eje 2t,t, yy 3t, 3,t 2, −1 4 002t, tt0 3, 72.xx x 2t, ejexxyx 3t,b) ejeyy ty 3, −2 − 1 −1 1 2 −2 −1 1 2 y 3t, 2t, 0eje 71. 71. xParametric a)a) eje eje x −2−2 In − 1−1 1 1852 and − 1 of the −2 a)−1 1b) eje 2 y 2 Equations Interval Area Exercises 86, find the−2area −1 − 1 72. x t, y 4 2t, 0 t 2, a) eje x b) eje y −2 2 −1 1−−1 −1 −2 −2 y 4, y 2t,5 sen 0 , t 0 2,72. t,, ejeeje yxy y 4t b)2t, t 2, 72. a)0eje xt 4 b) eje y the result −of Exercise 83.) 73.x x t, 5 cos 67. xx a)3t, 2eje 0y 2 −2 −2 −2 − 2−2 −2 , y 5 sen , 0 , eje y 73. x 5 1cos 2 y , y sen 1, 0t 73. cos 5 sen , CAS 0 73. yt 3 Closed Curves 85. 2 sin2 87–92, use a 86. x 2 cot 2 , 51eje 2, xxeje t 3, y, y t 5 1, 74.x x 5 3cos 68. Areas2 ,of0eje Simple In xExercises 2 y4 t , y t 3 CAS Áreas de curvas cerradas simples En los ejercicios 87 a 92, usar 1 y of 2Exercise sin2 87–92, tan83 touse y 2 sin2 computer algebraClosed systemCurves and the In result match y 3 t 1, 1 3 t , 02, eje y 1 ,3 eje x 74. CAS Areas of Simple Exercises a 75.xx x 13 tta33,,cos 1 t 2, x y 3 t , y t 1, 1 CAS t Areas 2, y ,t y 1, a sen 74. 74.eje yof un eje sistema algebraico porCurves computadora y of el resultado deluse ejerciCAS Areas Simple Closed In Exercises Simple 87–92, Closed Curves a In Exercises 8 3 the closed curve with its area. (These exercises were based on 2 3 3 computer algebra system and the result of Exercise 83 to match x cos 0 relacionar cos yy absen , eje 3x, y cos 3 75. cos sen3 ,,, 000 69. 76.xx x aa acos 3 ,,, y cio 83 para la and curva con su área.83(Estos ejersystem thecerrada result computer Exercise algebra system to match and the result a sen eje x , y a sen , 0 computer , algebra eje x with 75. 75. x 2 a, , cos 0of 0 <of Exercis < 2Area “The Surveyor’s Formula,” by Bart< Braden, College the closed curve its area. (These exercises were based on 2 with cicios fueron adaptados del artículo “The Surveyor’s Area the closed curve with its area. (These the exercises closed curve were based its on area. (These exercises w cos , y b sen , 2 , 0 76. x a) aeje x eje y b) Mathematics Journal, Septemberby 1986, 335–337, 2Surveyor’s , 76. x a cos , y b sen , 0 76. x 2 ,a cos , y b sen , 0 “The Area Formula,” Bart pp. Braden, Collegeby y Formula” Braden en la publicación de yseptiembre de Surveyor’s Area Formula,” “The by Bart Surveyor’s Braden, Area College Formula,” by Bart Bra sin , y cos “The 0 deofBart 70. x a) eje x b) eje y permission the 2author.) Mathematics Journal, September 1986, pp. 335–337, by eje x eje y eje x eje y a) b) a) b) 1986 del College Mathematics Journal, pp. 335-337, con autorMathematics Journal, September Mathematics 1986, pp. Journal, 335–337, September by 1986, pp. WRITING ABOUT CONCEPTS 2 permission of the author.) 3 ización autor.) permission of the author.) of the author.) (a) 83the (b)the (c) 2permission a2 abdel a2 W R I T I N G A B O U T C O N C E P T S 8 surface 77. Give the parametric form of the derivative. Surface Area In Exercises 71–76, find area of W R I T I N G A B Ode U Tconceptos C O N C E P T SW R I T I N G A B O U T C O N C E P T S 8 Desarrollo 3 22 1 1 883 ab 338 2 a222ab (a) (b) (c) ab given each axis. 77. Give the parametric form of thegenerated derivative.by revolving the curve about a)(d) b)(e) c)(f)22p6(a) aa22a 83 ab (a) (b) (c) (b) 38 a 2 (c) 2 a 2 a 33 ab 88p a 77. Give the parametric form of the derivative. 77. Give the parametric form of the derivative. In Dar Exercises 78paramétrica and 79, mentally determine dy/dx. 2 77. la forma de la derivada. x (d) (e) (f) 6 a ab 2 ab d)87.p ab e) 2tpb)ab2eje y (f) f) 66p88. aa22 Astroid: (d) (e)t 21 ab (f) 6 a 2 −2 − 1 aba) eje x0(e) ab y 3t, 0 t 3, (d) 71. x 2t,dy/dx. Ellipse: 2 2 −2 −1 0 In Exercises 78 and 79, mentally determine En losx ejercicios 783 y79, 79,mentally determinar In78. Exercises In Exercises 78 dy/dx. and determine dy/dx. t, 78 y and 79.determine x mentalmente t, ydy/dx. 6t 5 79, mentally 87. 3 t −1 Ellipse: 88. Astroid: 0 t 2 0−1 2 2, 72. x t, y 4 2t, 0 t 87. xEllipse: a cos x a) beje cos 87. Ellipse: Elipse: 88.87. Astroide: 88. Astroid: 88. Astroid: 0 0 0t t t 2 2 0x t t b)2 eje y 79. xx 5t,t, yy 5 6t 6t 2 55 78. x 5 t, y 5 33 79. 3 3 78. x Give t, y integral 3 79. x 78. t,x y t, parametric 6ty 53 form. 79. x x t, x a cos by cos tt 5 3ttt sin6t sin 3−2 80.Dar formula forlaarc length cos xxyx5aaacos x a cos− 23 t xxy5,bbacos bcos cos tt x 5in cosarco , yen forma 5 sen , 0 73. eje ytt 80. la the fórmula integral para longitud de 3 ty 2 y y a sin t y a sin 3 80. Give the integral formula for arc the length in parametric form.of 33tt t 81.paramétrica. Givethe theintegral integral formulas of the surfaces asin sin sen sen yy 5 ain tt yy y5 aasin asinsin y a sin 3 t 80. Give formula for for arc length 80. areas Give in the integral form. formula for arc length parametric form. 1 3parametric ya y xcurve3 tof 1 t 2, eje y , is yrevolved t 1,about 74. CAS Areas of Simple Closed Curves In Exercises revolution formed when a smooth C 81. Give the integral formulas for the areas the surfaces of y y y y y y 8 a 81. parathe lasareas áreas superficies de 81. Dar Givelas thefórmulas integral integrales formulas for 81. Giveofde the the integral surfacesformulas of for the areas of the surfaces of 3 , y about 3 , computer algebra system and the result of Exercis (a) the xaxis and (b) the yaxis. a revolution formed when a smooth curve C is revolved a sen x a cos 0 , eje x 75. revolución generadas pora smooth revolución deCuna curva suave C a smooth curve C isaarevolved about a a revolution formed when curve revolution is revolved formed about when a the closedaa curve with its area. (These exercises w (a) the x-axis and (b) the y-del axis. alrededor a) del y b)yeje cosx-axis , y andb(b) senthe, y-0axis. 2 , 76.y.x (a)athe (a) the x-axis andeje(b)x the axis. “The Surveyor’s Area xFormula,” by Bart Bra b a a) eje x b) eje y Mathematics Journal,x September 1986, pp. CAPSTONE C AP PS S(a) OSketch N EE a graph of a curveC 82. Wdefined T ITNOby GN Ethe A B Oparametric UT CONCEPTS CPara A TTdiscusión O N ARPI S b bb x equations thatparametric x of g t a and f t such dx dt > 0 82. (a) Sketch a graph curvey defined bythe the 77. (a) Giveby of the defined derivative. 82. (a) Sketch a graph of a curve defined 82. Sketch theparametric parametric a graph form of a curve by the parametric and dyla dt all real numbers 82. a) Dibujar gráfica una por las equations x < 0g for tde and ycurva f definida t sucht. that dx ecuaciodt > 0 equations x g t and y f t suchequations that dx xdt >g0t and y 89. such that0 dx tdt >2 0 f t Cardioid: nes paramétricas 5 real g(t) yIn y Exercises 5 f(t) manera que and numbers dy dt < 0 forxofall t. bydethe (b) Sketch curve defined parametric 78 and mentally determine dy/dx. and numbers all real 89. numbers dy dta <graph t.and dy dt 0 for allareal < 79, 0 for Cardioid: 0 t ≤2 2p x t.2a cos dxydt > 0 y dyydt < 0 para todos los números reales t. 89. Cardioid: Cardioide: 89. 0s0t ≤t ta cos 2 2td equations and such that x g t y f t dx dt < 0 (b) Sketch a graph of a curve defined by the parametric (b) Sketch a graph of a curve defined (b) by Sketch the parametric a 3graph of a curve defined by the parametric 78. x t, y 79. x t, y 6t 5 x 2a cos t a cos 2t 2acos sin tt 2 aacos sin2t 2t and dyladt all numbers b) Dibujar gráfica unareal por las equations x < 0g for tdeand ycurva f definida t sucht. that dx ecuaciodt < 0 xy5 2a 2a cos cos 2t equations x g t and y f t suchequations that dx xdt <g0t and y f xt such thatt dxa dt < 0 y nes 5 real g(t)numbers y y 5 f(t) yy 5 2a sin t a sin 2t and paramétricas dy dt < 0 forx all t. de manera que 2a sintt 2 aasin sin 2t sen sen y 2a sin 2t and dy dt < 0 for all real numbers t.and dt < formula realarc numbers t. parametric 0 for allfor 80. los Give thedy integral length in form. dxydt < 0 y dyydt < 0 para todos números reales t. y yy Give formulas for the areas of the surfaces of 83. Use integration by substitution to 81. show thatthe if yintegral is a continuous revolution formed when x a x b, x f t anda smooth curve C is revolved about function of on the interval where 83. Use integration by substitution to show that if y is a continuous 83. Mediante Use integration by substitution to83. show Use that integration if yx-que isaxis a si continuous byy substitution to show that if y is a continuous (a) the y-axis. por sustitución una 83. y g t of ,integración then x x on the interval a x mostrar b, the x and f es t(b)and function where a x afunction b, xx onx fthe t f sand a x b, where xa f t and functioncontinua of x on de thex en interval where of interval función el intervalo ≤ x ≤ b, donde y 5 t d y b g t , then t 2 x td,, entonces y g t , then then xx yy 5 ggystdx a g t f t dt b t a a bba tt222t C A PbS T O N E t 2 1 dx 5 dt yy dx ggsttd ff9stttd dt dt y dx g t f t dt t1 a 82. ag(a) a graph ofon a curve defined by the parametric andSketch a, f t 2 b, and both f aret1continuous aawhere f t1 tt11 x g on tenand y f t such that dx dt > 0 t1, t 2ff. st1t1d 5a,a,f f ts2t 2d 5b,b,and where bothggcomo and fequations are continuous donde y tanto son continuas f 9 where f t and fand onall a, f t 2 b, and both gwhere f are t1dycontinuous b, and g andt.f are continuous on realboth numbers dta, <f t02 for fttt11,,, ttt22g... 1 t1, t 2 . 1 2 (b) Sketch a graph of a curve defined by the parametric equations x g t and y f t such that dx dt < 0 and dy dt < 0 for all real numbers t. E xx permission of the author.) baaa (a) 83 ab (b) a2 (c) 2 a 2 (d) Deltoid: ab 90. 0 (e)t 2 ab 2 90. Deltoid: 0 t 2 x 2a cos t a cos 90.87. Deltoide: 90. 89. Deltoid: Cardioid: Ellipse: 0 0 0 t t t 2 2 22t xxy5 2a cos t aaacos 2t 2a sin sin 2t2t 2a cos 2t x x 2a cos cos tttt 1 t a cos acos cos 2t b2a cos yt yy 5 2a sin a sin 2t 2aa2a sin 2t2t sen sen y y 2a sin sin sin ttt 2 t aasin asinsin 2t y yy (f) 6 a 2 90. 88. Deltoid: Astroid: 0 x a2acos cos3 t y a sin 2a sin3 t y yy a a a E a aa 89. Cardioid: 0 x x a b a t 2 90. Deltoid: 0 x 2a cos t a cos 2t x 2a cos t y 2a sin t a sin 2t y 2a sin t y 83. Use integration by substitution to show that if y is a continuous 3 8 y 10-3.qxd 3/12/09 9/2/08 16:47 3:50 Page PM 730 Page 730 1059997_1003.qxp 1059997_1003.qxp 9/2/08 3:50 PM Page 730 730 730 730 CAPÍTULO 10 Cónicas, ecuaciones paramétricas y coordenadas polares Chapter 10 Conics, Parametric Equations, and Polar Coordinates Chapter 10 Conics, Parametric Equations, and Polar Coordinates 91. Reloj de arena: s0 ≤ t ≤ 2pd 92. Lágrima: s0 ≤ t ≤ 2pd 91. Hourglass: 0 t 2 92. Teardrop: 0 ≤ t ≤ 2 5 a sen sin 2t 0 t 2 x 5 2a cos t 2t a≤sen sin 0 ≤ 2 2t 91. xHourglass: 92. Teardrop: x a sin 2t x 2a cos t a sin 2t yx 5 basen sin sin t sin t2t x y 52abcos t a sin 2t sen y b sin t y b sin t y y y b sin yt y b sin yt b y b b b b b y x a a a a a a x x x Centroide EnExercises los ejercicios 94, the hallar el centroide de la Centroid In 93 and9394,y find centroid of the region Centroid In the Exercises 93ofand 94, findecuaciones the centroid of theand region región limitada por la gráfica las paramétricas bounded by graph thede parametric equations they bounded the (Use graph ofresult theelof parametric equations los ejes de by coordenadas. resultado ejercicio and 83.) the coordinate axes. the(Usar Exercisedel 83.) coordinate axes. (Use the result of Exercise 83.) 93. x 94. x t, y 4 t 4 t, y t t, y 4 t 4 t, y t 93. x 94. x Volumen EnExercises los ejercicios 95 y96, 96,find hallar volumen Volume In 95 and theelvolume of del thesólido solid generado revolución torno al ejethe x by de la limitada Volume Inrevolving Exercises 95en and 96,bounded find volume of the formed bypor the region theregión graphs ofsolid the por la equations gráfica deabout las the ecuaciones dadas. elofgraphs resultado del formed by revolving by the of 83.) the given theregion (Use the(Usar result Exercise x-axis. bounded ejercicio 83.) given equations about the x-axis. (Use the result of Exercise 83.) 95. x 6 cos , y 6 sen 95. 95. x 6 cos , y 6 sen 96. x cos , y 3 sin , a > 0 sin 96. 96. xx 5 cos cos u,, yy 5 33sen sin u,, aa >> 00 97. Cycloid Use the parametric equations 97. Emplear las ecuaciones paramétricas 97. Cicloide Cycloid Use the parametric equations y a 1 cos , a > 0 and x a sin xx 5 aasu 2 sen sin ud, a ,>a 0> 0 yand y 5y as1a21 coscos sin ud to answer the following. para responder lo siguiente. to answer the following. 2 2. 2. dx and y dx (a)Hallar Find dy dyydx a) y d 2dyydx (a) Find dy dx and d 2y dx 2. (b)Hallar Find the equation ofdethe line at en theelpoint b) las ecuaciones la tangent recta tangente puntowhere en el (b)que Find thep equation of the tangent line at the point where 6.y6. u5 6. (c)Localizar Find all points of horizontal tangency. c) todos (if losany) puntos (si los hay) de tangencia hori(c)zontal. Find all points (if any) of horizontal tangency. (d) Determine where the curve is concave upward or concave (d)Calcular Determine where thecurva curvecóncava is concave concave downward. d) dónde es la haciaupward arriba or y dónde es downward. abajo. (e)cóncava Find thehacia length of one arc of the curve. (e)Hallar Find the length ofdeone la longitud un arc arcoofdethela curve. curva. 98. e) Use the parametric equations 98. Use the parametric equations 98. Emplear las ecuaciones paramétricas 1 y 3t 1 t3 x t2 3 and 2 1 3t t33 t3 xx 5 tt2!33 yand y 5y 3t 2 3 3 to answer the following. to answer the following. para los incisos siguientes. (a) Use a graphing utility to graph the curve on the interval (a)Emplear Use a graphing utility todegraph the curve the la interval a) una graficación paraon trazar curva 3 t 3.herramienta 3 intervalo t 3. 232 ≤ t ≤2 3. en el (b) Find dy dx and d y dx . 2 y dx 2. 2. dx and (b)Hallar Find dy 8 dyydx b) y d 2dyydx 3, 83 . (c) Find the equation of the tangent line at the point 8 . (c)Hallar Find the equationde of la therecta tangent line atenthe point s!3, 3, c) la ecuación tangente el punto 3 3 d. (d) Find the length of the curve. (d) Find the length of the curve. d) la curva. (e)Hallar Find la thelongitud surfacedearea generated by revolving the curve (e)Hallar Find the surface generated by revolving the curve e) de la area superficie generada por revolución de la aboutel theárea x-axis. aboutenthe x-axis. curva torno al eje x. 99. Involute of a Circle The involute of a circle is described by 99. Evolvente Involute ofo involuta aPCircle involute a circle described by 99. deThe círculo La of evolvente involuta de un the endpoint of a string that is held taut as it isoisunwound from the endpoint P of anot string isfigure). held taut as una it that is unwound from círculo está por el(see extremo P Show de cuerda que se a spool that descrita does turnthat a parametric arepresentation spool that does not involute turn that a que parametric mantiene tensa mientras se (see desenrolla un carrete no gira of the isfigure).deShow representation the involute (ver la figura). of Mostrar que laissiguiente es una representación x r cos de la sin y r sin cos . paramétrica evolvente oand involuta x r cos sin y r sin cos . and y x 5 rscos u 1 u sen sin ud y 5 rssen sin u 2 u cos ud. y y y 1 1 1 r rθ rr θ P rθ P r P x x x Figura para 99 Figura para 100 Figure for 99 Figure for 100 Evolvente involuta de un círculo La figura muestra un seg100. Figure foro99 Figure for 100 mento deofcuerda sujetoThe a un círculo de aradio cuerda 100. Involute a Circle figure shows piece1.ofLastring tiedes 100. Involute of with a Circle Thelarga shows a piece ofisopuesto string tied justo lo suficientemente llegar al lado del to a circle a radius offigure onepara unit. The string just long to a circle with athe radius one Thecircle. stringFind is círculo. Encontrar elopposite áreaofque seunit. cubre cuando la just cuerda enough to reach side of the the long arease enough to reach the opposite of las the manecillas circle. Finddel thereloj. area desenrolla en sentido contrario al unwound de that is covered when the stringside is counterclockwise. that is covered when the string is unwound counterclockwise. a) Usar herramienta degraph graficación paragiven trazar 101. (a) Use auna graphing utility to the curve by la curva 101. (a) utility to graph the curve given by dadaUse pora graphing 2 1 t 2t x 11 2 tt222, y 20 t 20. 2t t 2 , 2t 1 1 t x 5 , y 5 220 x 20 ≤ t ≤ 20. 2, y 2,, 2 2 11 1 tt 11 1 tt (b) Describe la thegráfica graph yand confirm la your result analytically. b) Describir confirmar respuesta en forma ana(b) lítica. Describe the graph and confirm your result analytically. (c) Discuss the speed at which the curve is traced as t (c) Discuss the speed which curvela iscurva traced as t t 20 at increasesla from toa20. c) Analizar velocidad la cual the se traza cuando 20 increases from to 20. aumentaAde 220 amoves 20. from the origin along the positive 102. Tractrix person 102. Tractrix A person moves from along positive axis pulling a persona weight at end the of aorigin 12-meter rope. 102. yTractriz Una sethe mueve desde el origen athe lo Initially, largo del yaxis pulling a weight at the end of a 12-meter rope. Initially, 12, 0 . the weight is located at the point eje y positivo tirando un peso atado al extremo de una cuerda 0. the weight is located at Inicialmente, the point 12, el de 12 de96 largo. estáthat situado en el (a) In metros Exercise of Section 8.7, it waspeso shown the path punto s 12, 0 d . (a) In Exercise 96 of Section 8.7, it was shown that the path of the weight is modeled by the rectangular equation of the weight is96modeled by the8.7 rectangular a) En el ejercicio de la sección se mostróequation que la trayec12 144 x 2 toria del12peso mediante la 144 siguiente y ln 12se describe x 2 ecuación 2 144 x x y 12 ln 144 x 2 rectangular x where 0 < x 12 12. utility to graph the 2 !Use 144a2graphing x2 y 5 212 2 !144 2 x 2 12. Use where 0 <lnxequation. rectangular x a graphing utility to graph the rectangular equation. (b) donde Use a graphing to graph the parametric una herramienta de equations graficación 0 < x ≤ utility 12. Usar (b) para Use representar a graphing utility to graph the parametric equations la ecuación rectangular. t t x 12 y t para 12 tanh and b) Usar unasech herramienta de graficación trazar t t la gráfica 12 12 x las12ecuaciones sech y t 12 tanh and de 12 12 paramétricas where t 0. How does this graph compare with t t the graph ygraph x 5part 12t sech 5 either) t 2compare 12 do tanhyou where How does thisy(if graph withthink the graph in (a)?0. 12 Which is a 12 in part (a)? Which graph (if either) do you think is a better representation of the path? donde t ≥ 0. Comparar esta gráfica con la del inciso a). better representation of the path? (c) ¿Qué Use the parametric for the tractrix verify that gráfica (si hay equations alguna) representa mejor latotrayectoria? (c) Use the parametric equations for of thethe tractrix to verify ythe distance from the intercept tangent linepara tothat the c) Emplear las ecuaciones paramétricas de la tractriz veythe distance from the intercept of of thethe tangent line of to the point of tangency is independent location thela rificar que la distancia de la intersección con el eje y de point of tangency. tangency is independent of the location of the pointtangente of recta al punto de tangencia es independiente de point of tangency. la ubicación del punto de tangencia. True or False? In Exercises 103 and 104, determine whether True or False? In Exercises 103 104,y explain determine the statement is true or false. If it and is false, whywhether or give ¿Verdadero o falso? En los ejercicios 103 104, determinar si la the statement is true If itSiisesfalse, why orqué giveo an example that showsoritfalse. is false. afirmación es verdadera o falsa. falsa,explain explicar por an thatque shows it is false. darexample un ejemplo demuestre que es falsa. 103. If x f t and y g t , then d 2 y dx 2 g t f t . 2 2 yydx 2g5 tg0 s 103. If and d 2 y dx , then f tdyf t .0 std. Sixx curve y y y5bygsgxtdt, entonces 5f f sttdgiven 104. The a horizontal tangent at t 3, y td2 has 3 y 22 3 t 104. The curve given by has a horizontal tangent at x t , La curva por dy 5dt 05 horizont una 0. tangente the origindada because whentiene dy dt 0 when 0. the origin because tal en el origen puesto que dyydt 5 t0 cuando t 5 0. 105. Tape Another use usar to solve 105. Recording Cinta de grabación Otro method método you que could se puede para 105. Recording Tape Another method you with couldanuse to radius solve Example 5 is to find the area of the reel inner solucionar el ejemplo 5 es encontrar el área del carrete con un Example 5 is to findouter the area ofof the2 reel withand an then inneruse radius of 0.5interior inch and radius inches, the radio de an 0.5 pulgadas y un radio exterior de 2 pulgadas, of 0.5 inch and an outer radius of 2 where inches,the andwidth then isuse the formula for the area of the rectangle y después usar la fórmula para el área del rectángulo0.001 cuyo formula for themethod area oftothe rectanglehow where thetape width is 0.001 inch. this determine is required anchoUse es de 0.001 pulgadas. Utilizar estemuch método para determiinch. Use this method to determine how much tape is required to fill the reel. nar cuánta cinta se necesita para llenar el carrete. to fill the reel. 1 2 10-4.qxd 3/12/09 16:56 Page 731 SECCIÓN 10.4 SECCIÓN 10.4 731 731 Coordenadas polares y gráficas polares Coordenadas polares y gráficas polares 10.4 Coordenadas polares y gráficas polares n n n n n Comprender el sistema de coordenadas polares. Expresar coordenadas y ecuaciones rectangulares en forma polar y viceversa. Trazar la gráfica de una ecuación dada en forma polar. Hallar la pendiente de una recta tangente a una gráfica polar. Identificar diversos tipos de gráficas polares especiales. Coordenadas polares a gid cia i dir P = (r, θ) tan r is =d Hasta ahora las gráficas se han venido representando como colecciones de puntos (x, y) en el sistema de coordenadas rectangulares. Las ecuaciones correspondientes a estas gráficas han estado en forma rectangular o en forma paramétrica. En esta sección se estudiará un sistema de coordenadas denominado sistema de coordenadas polares. Para formar el sistema de coordenadas polares en el plano, se fija un punto O, llamado polo (u origen), y a partir de O se traza un rayo inicial llamado eje polar, como se muestra en la figura 10.36. A continuación, a cada punto P en el plano se le asignan coordenadas polares (r, u), como sigue. θ = ángulo dirigido r 5 distancia dirigida de O a P u 5 ángulo dirigido, en sentido contrario al de las manecillas del reloj desde el eje — polar hasta el segmento OP Eje polar O Coordenadas polares Figura 10.36 La figura 10.37 muestra tres puntos en el sistema de coordenadas polares. Obsérvese que en este sistema es conveniente localizar los puntos con respecto a una retícula de circunferencias concéntricas cortadas por rectas radiales que pasan por el polo. π 2 π 2 π 2 θ =π 3 (2, π3 ) π 1 2 3 0 π 2 3π 2 3π 2 a) b) 3 0 π 2 θ = −π 6 π 3, − 6 ( ) 3π 2 0 3 θ = 11π 6 11π 3, 2 6 ( ) c) Figura 10.37 COORDENADAS POLARES El matemático al que se le atribuye haber usado por primera vez las coordenadas polares es James Bernoulli, quien las introdujo en 1691. Sin embargo, ciertas evidencias señalan la posibilidad de que fuera Isaac Newton el primero en usarlas. En coordenadas rectangulares, cada punto sx, yd tiene una representación única. Esto no sucede con las coordenadas polares. Por ejemplo, las coordenadas sr, ud y sr, 2p 1 ud representan el mismo punto [ver los incisos b) y c) de la figura 10.37]. También, como r es una distancia dirigida, las coordenadas sr, ud y s2r, u 1 pd representan el mismo punto. En general, el punto sr, ud puede expresarse como sr, ud 5 sr, u 1 2npd o sr, ud 5 s2r, u 1 s2n 1 1dpd donde n es cualquier entero. Además, el polo está representado por s0, ud, donde u es cualquier ángulo. 10-4.qxd 3/12/09 732 16:56 Page 732 CAPÍTULO 10 Cónicas, ecuaciones paramétricas y coordenadas polares Transformación (o cambio) de coordenadas y Para establecer una relación entre coordenadas polares y rectangulares, se hace coincidir el eje polar con el eje x positivo y el polo con el origen, como se ilustra en la figura 10.38. Puesto que sx, yd se encuentra en un círculo de radio r, se sigue que r 2 5 x 2 1 y 2. Para r > 0, la definición de las funciones trigonométricas implica que (r, θ ) (x, y) r y θ Polo x cos u 5 , r y tan u 5 , x y y sin sen u 5 . r x Eje polar (eje x) x (Origen) Si r < 0, estas relaciones también son válidas, como se puede verificar. TEOREMA 10.10 TRANSFORMACIÓN (O CAMBIO) DE COORDENADAS Relación entre coordenadas polares y rectangulares Las coordenadas polares sr, ud de un punto están relacionadas con las coordenadas rectangulares sx, yd de ese punto como sigue. y 1. x 5 r cos u 2. tan u 5 x y 5 r sen sin u r 2 5 x2 1 y 2 Figura 10.38 y 2 π 3, 6 ) (x, y) = 3 , 3 2 2 ) (r, θ) = 1 ( (r, θ) = (2, π ) −2 ( 1 −1 EJEMPLO 1 x 2 (x, y) = (−2, 0) Transformación (o cambio) de coordenadas polares a rectangulares a) Dado el punto sr, ud 5 s2, pd, x 5 r cos u 5 2 cos p 5 22 −1 y y 5 r sen sin u 5 2 sen sin p 5 0. Por tanto, las coordenadas rectangulares son sx, yd 5 s22, 0d. −2 b) Dado el punto sr, ud 5 s!3, py6d, Para pasar de coordenadas polares a rectangulares, se hace x 5 r cos u y y 5 r sen u. x 5 !3 cos p 3 5 6 2 y 5 !3 sen sin y p !3 5 . 6 2 Por tanto, las coordenadas rectangulares son sx, yd 5 s3y2, !3y2d. Ver la figura 10.39. Figura 10.39 EJEMPLO 2 Transformación (o cambio) de coordenadas rectangulares a polares a) Dado el punto del segundo cuadrante sx, yd 5 s21, 1d, tan u 5 y 2 (r, θ) = ( 3π 2, 4 ) π (r, θ) = 2 , 2 (x, y) = (0, 2) ( 3p . 4 r 5 !x 2 1 y 2 5 !s21d 2 1 s1d 2 (x, y) = (−1, 1) x −1 u5 Como u se eligió en el mismo cuadrante que sx, yd, se debe usar un valor positivo para r. ) 1 −2 y 5 21 x 1 2 5 !2 Esto implica que un conjunto de coordenadas polares es sr, ud 5 s!2, 3py4d. Para pasar de coordenadas rectangulares a polares, se toma tan u 5 yyx y r 5 !x 2 1 y 2 . b) Dado que el punto sx, yd 5 s0, 2d se encuentra en el eje y positivo, se elige u 5 py2 y r 5 2, y un conjunto de coordenadas polares es sr, ud 5 s2, py2d. Figura 10.40 Ver la figura 10.40. 10-4.qxd 3/12/09 16:56 Page 733 SECCIÓN 10.4 π 2 Coordenadas polares y gráficas polares 733 Gráficas polares Una manera de trazar la gráfica de una ecuación polar consiste en transformarla a coordenadas rectangulares para luego trazar la gráfica de la ecuación rectangular. π 1 2 3 0 EJEMPLO 3 Trazado de ecuaciones polares Describir la gráfica de cada ecuación polar. Confirmar cada descripción transformando la ecuación a ecuación rectangular. 3π 2 a) r 5 2 a) Círculo: r 5 2 b) u 5 p 3 c) r 5 sec u Solución π 2 π 1 2 3 a) La gráfica de la ecuación polar r 5 2 consta de todos los puntos que se encuentran a dos unidades del polo. En otras palabras, esta gráfica es la circunferencia que tiene su centro en el origen y radio 2. (Ver la figura 10.41a.) Esto se puede confirmar utilizando la relación r 2 5 x 2 1 y 2 para obtener la ecuación rectangular 0 x 2 1 y 2 5 22. b) La gráfica de la ecuación polar u 5 py3 consta de todos los puntos sobre la semirrecta que forma un ángulo de py3 con el semieje x positivo. (Ver la figura 10.41b.) Para confirmar esto, se puede utilizar la relación tan u 5 yyx para obtener la ecuación rectangular 3π 2 b) Recta radial: u 5 Ecuación rectangular. p 3 y 5 !3 x. π 2 Ecuación rectangular. c) La gráfica de la ecuación polar r 5 sec u no resulta evidente por inspección simple, por lo que hay que empezar por pasarla a la forma rectangular mediante la relación r cos u 5 x. π 1 2 3 0 r 5 sec u r cos u 5 1 x51 3π 2 Ecuación polar. Ecuación rectangular. Por la ecuación rectangular se puede ver que la gráfica es una recta vertical. (Ver la figura 10.41c.) c) Recta vertical: r 5 sec u Figura 10.41 TECNOLOGÍA Dibujar a mano las gráficas de ecuaciones polares complicadas puede ser tedioso. Sin embargo, con el empleo de la tecnología, la tarea no es difícil. Si la herramienta de graficación que se emplea cuenta con modo polar, usarlo para trazar la gráfica de las ecuaciones de la serie de ejercicios. Si la herramienta de graficación no cuenta con modo polar, pero sí con modo paramétrico, se puede trazar la gráfica de r 5 f sud expresando la ecuación como x 5 f sud cos u y 5 f sud sen sin u. 6 −9 9 −6 Espiral de Arquímedes Figura 10.42 Por ejemplo, la gráfica de r 5 12u que se muestra en la figura 10.42 se generó con una herramienta de graficación en modo paramétrico. La gráfica de la ecuación se obtuvo usando las ecuaciones paramétricas 1 x 5 u cos u 2 1 y 5 u sen sin u 2 con valores de u que van desde 24p hasta 4p. Esta curva es de la forma r 5 au y se denomina espiral de Arquímedes. 10-4.qxd 3/12/09 734 16:56 Page 734 CAPÍTULO 10 Cónicas, ecuaciones paramétricas y coordenadas polares EJEMPLO 4 NOTA Una forma de bosquejar la gráfica de r 5 2 cos 3u a mano, es elaborar una tabla de valores. u 0 p 6 p 3 p 2 2p 3 r 2 0 22 0 2 Si se amplía la tabla y se representan los puntos gráficamente se obtiene la curva mostrada en el ejemplo 4. n Trazado de una gráfica polar Dibujar la gráfica de r 5 2 cos 3u. Solución Para empezar, se expresa la ecuación polar en forma paramétrica. x 5 2 cos 3u cos u y 5 2 cos 3u sen sin u y Tras experimentar un poco, se encuentra que la curva completa, la cual se llama curva rosa, puede dibujarse haciendo variar a u desde 0 hasta p, como se muestra en la figura 10.43. Si se traza la gráfica con una herramienta de graficación, se verá que haciendo variar a u desde 0 hasta 2p, se traza la curva entera dos veces. π 2 π 2 π 0 π 0 1 2 p 6 0 ≤ u ≤ 3π 2 p 3 0 ≤ u ≤ π 2 π 0 1 2 3π 2 π 2 0 p 2 π 2 π 0 1 2 π 0 1 2 3π 2 0 ≤ u ≤ π 1 2 3π 2 0 ≤ u ≤ π 2 3π 2 2p 3 0 ≤ u ≤ 5p 6 1 2 3π 2 0 ≤ u ≤ p Figura 10.43 Usar una herramienta de graficación para experimentar con otras curvas rosa (estas curvas son de la forma r 5 a cos nu o r 5 a sen sin nud. Por ejemplo, las curvas que se muestran en la figura 10.44 son otros dos tipos de curvas rosa. r = 2 sen 5θ r = 0.5 cos 2θ 2 π 2 3 −3 0 0.2 0.3 0.4 −2 Curvas rosa Figura 10.44 Generada con Mathematica 10-4.qxd 3/12/09 16:56 Page 735 SECCIÓN 10.4 Coordenadas polares y gráficas polares 735 Pendiente y rectas tangentes Para encontrar la pendiente de una recta tangente a una gráfica polar, considerar una función diferenciable (o derivable) r 5 f sud. Para encontrar la pendiente en forma polar, se usan las ecuaciones paramétricas x 5 r cos u 5 f sud cos u y y 5 r sen sin u 5 f sud sen sin u. Mediante el uso de la forma paramétrica de dyydx dada en el teorema 10.7, se obtiene π 2 dy dyydu 5 dx dxydu Recta tangente r = f( θ) 5 (r, θ ) f sud cos u 1 f 9sud sin sen u 2f sud sen sin u 1 f9sud cos u con lo cual se establece el teorema siguiente. π 0 TEOREMA 10.11 PENDIENTE EN FORMA POLAR Si f es una función diferenciable (o derivable) de u, entonces la pendiente de la recta tangente a la gráfica de r 5 f sud en el punto sr, ud es 3π 2 dy dyydu f sud cos u 1 f9sud sen sin u 5 5 dx dxydu 2f sud sen sin u 1 f9sud cos u Recta tangente a una curva polar Figura 10.45 siempre que dxydu Þ 0 en sr, ud. (Ver la figura 10.45.) En el teorema 10.11 se pueden hacer las observaciones siguientes. 1. Las soluciones dy dx 5 0 dan una tangente horizontal, siempre que Þ 0. du du 2. Las soluciones dx dy 5 0 dan una tangente vertical, siempre que Þ 0. du du Si dyydu y dxydu simultáneamente son 0, no se puede extraer ninguna conclusión respecto a las rectas tangentes. EJEMPLO 5 Hallar las rectas tangentes horizontales y verticales Hallar las rectas tangentes horizontales y verticales a r 5 sen sin u, 0 ≤ u ≤ p. Solución Para empezar se expresa la ecuación en forma paramétrica. π 2 x 5 r cos u 5 sen sin u cos u ( 1, π2 ) y y 5 r sen sin u 5 sen sin u sen sin u 5 sen sin 2 u ( 22 , 34π ) ( 22 , π4 ) π (0, 0) 1 2 0 3π 2 Rectas tangentes horizontales y verticales a r 5 sen u Figura 10.46 Después, se derivan x y y con respecto de u y se iguala a 0 cada una de las derivadas. dx 5 cos 2 u 2 sen sin 2 u 5 cos 2u 5 0 du dy 5 2 sen sin u cos u 5 sen sin 2u 5 0 du u5 u 5 0, p 3p , 4 4 p 2 Por tanto, la gráfica tiene rectas tangentes verticales en s!2y2, py4d y s!2y2, 3py4d, y tiene rectas tangentes horizontales en s0, 0d y s1, py2d, como se muestra en la figura 10.46. 10-4.qxd 4/1/10 736 13:11 Page 736 CAPÍTULO 10 Cónicas, ecuaciones paramétricas y coordenadas polares EJEMPLO 6 Hallar las rectas tangentes horizontales y verticales Hallar las rectas tangentes horizontales y verticales a la gráfica de r 5 2s1 2 cos ud. π 2 Solución Se usa y 5 r sin sen u, se deriva y dyydu se iguala a 0. ( ) 3, 2π 3 y 5 r sen sin u 5 2s1 2 cos ud sen sin u ( 1, π3 ) (4, π ) π 0 ( 1, 53π ) dy sen udg sen ussin 5 2 fs1 2 cos udscos ud 1 sin du 5 22s2 cos u 1 1dscos u 2 1d 5 0 ( 3, 43π ) Por tanto, cos u 5 2 12 y cos u 5 1, y se concluye que dyydu 5 0 cuando u 5 2py3, 4py3,y 0. De manera semejante, al emplear x 5 r cos u, se tiene 3π 2 x 5 r cos u 5 2 cos u 2 2 cos 2 u dx senu 5 2 sin sen u 1 4 cos u sin sen us2 cos u 2 1d 5 0. 5 22 sin du Rectas tangentes horizontales y verticales de r 5 2s1 2 cos ud Por tanto, sen q = 0 o cos u 5 2 2 , y se concluye que dyydu 5 0 cuando q = 0, p, p/3 y 5p/3. A partir de estos resultados y de la gráfica que se presenta en la figura 10.47, se concluye que la gráfica tiene tangentes horizontales en (3, 2p/3) y (3, 4p/3), y tangentes verticales en (1, p/3), (1, 5p/3) y (4, p). A esta gráfica se le llama cardioide. Obsérvese que cuando q = 0 ambas derivadas (dyydu y dxydu) son cero (es decir, se anulan). Sin embargo, esta única información no permite saber si la gráfica tiene una recta tangente horizontal o vertical en el polo. Pero a partir de la figura 10.47 se puede observar que la gráfica tiene una cúspide (o punto anguloso o cuspidal) en el polo. Figura 10.47 1 El teorema 10.11 tiene una consecuencia importante. Supóngase que la gráfica de r 5 f sud pasa por el polo cuando u 5 a y f9sad Þ 0. Entonces la fórmula para dyydx se simplifica como sigue. dy f9sad sen sin a 1 f sad cos a f9sad sen sin a 1 0 sin a sen 5 5 5 5 tan a dx f9sad cos a 2 f sad sen sin a f9sad cos a 2 0 cos a Por tanto, la recta u 5 a es tangente a la gráfica en el polo, s0, ad. f(θ ) = 2 cos 3θ π 2 TEOREMA 10.12 RECTAS TANGENTES EN EL POLO Si f sad 5 0 y f9sad Þ 0, entonces la recta u 5 a es tangente a la gráfica de r 5 f sud. en el polo. π 0 2 3π 2 Esta curva rosa tiene, en el polo, tres rectas tangentes su 5 p y6, u 5 p y 2, y u 5 5p y6d Figura 10.48 El teorema 10.12 es útil porque establece que los ceros de r 5 f sud pueden usarse para encontrar las rectas tangentes en el polo. Obsérvese que, puesto que una curva polar puede cruzar el polo más de una vez, en el polo puede haber más de una recta tangente. Por ejemplo, la curva rosa f sud 5 2 cos 3u tiene tres rectas tangentes en el polo, como se ilustra en la figura 10.48. En esta curva, f sud 5 2 cos 3u es 0 cuando u es py6, py2, y 5py6. La derivada ƒ9(u) 5 26 sen u no es 0 en estos valores de u. 10-4.qxd 3/12/09 16:56 Page 737 SECCIÓN 10.4 737 Coordenadas polares y gráficas polares Gráficas polares especiales Varios tipos importantes de gráficas tienen ecuaciones que son más simples en forma polar que en forma rectangular. Por ejemplo, la ecuación polar de un círculo de radio a y centro en el origen es simplemente r 5 a. Más adelante se verán las ventajas que esto tiene. Por ahora, se muestran abajo algunos tipos de gráficas cuyas ecuaciones son más simples en forma polar. (Las cónicas se abordan en la sección 10.6.) Caracoles π 2 r 5 a ± b cos u r 5 a ± b sen sin u sa > 0, b > 0d π 2 π 0 π 3π 2 2n pétalos si n es par sn ≥ 2d π 2 π 0 π 3π 2 1 < π 2 0 3π 2 a < 2 b Caracol con hoyuelo a 51 b Cardioide (forma de corazón) π 2 n pétalos si n es impar 0 3π 2 a < 1 b Caracol con lazo interior Curvas rosa Rose Curves π 2 a ≥ 2 b Caracol convexo π 2 π 2 n=4 n=3 π a 0 π 0 π 0 a r 5 a cos nu Curva rosa Círculos y lemniscatas π r 5 a sen sin nu Curva rosa π 2 a 0 3π 2 r 5 a sen sin nu Curva rosa π 2 π n=2 3π 2 r 5 a cos nu Curva rosa π 2 0 n=5 3π a 2 3π 2 a π 0 π 2 a π 0 π 0 a a 3π 2 r 5 a cos u Círculo 3π 2 sin u r 5 a sen Círculo 3π 2 sin 2u r 2 5 a 2 sen Lemniscata 3π 2 r 2 5 a2 cos 2u Lemniscata TECNOLOGÍA Las curvas rosa descritas arriba son de la forma r 5 a cos nu o r 5 a sen sin nu, donde n es un entero positivo mayor o igual a 2. Usar una herramienta de graficación para trazar las gráficas de r 5 a cos nu o r 5 a sen sin nu con valores no enteros de n. ¿Son estas gráficas también curvas rosa? Por ejemplo, trazar la gráfica de r 5 cos 23u, 0 ≤ u ≤ 6p. Gráfica generada con Maple PARA MAYOR INFORMACIÓN Para más información sobre curvas rosa y otras curvas relacionadas con ellas, ver el artículo “A Rose is a Rose...” de Peter M. Maurer en The American Mathematical Monthly. La gráfica generada por computadora que se observa al lado izquierdo, es resultado de un algoritmo que Maurer llama “La rosa”. 1059997_1004.qxp 9/2/08 9/2/08 3:51 3:51 PM PM Page Page 738 738 1059997_1004.qxp 1059997_1004.qxp 9/2/08 3:51 PM Page 738 10-4.qxd 3/12/09 9/2/08 16:56 3:51 Page PM 738 Page 1059997_1004.qxp 9/2/08 3:51 PM Page 738 738 1059997_1004.qxp 1059997_1004.qxp 9/2/08 3:51 PM Page 738 1059997_1004.qxp 9/2/08 3:51 PM Page 738 738 738 738 738 738 738 738 CAPÍTULO Cónicas, ecuaciones paramétricas coordenadas polares Chapter 10 10 Conics, Parametric Equations, and yPolar Coordinates Chapter 10 Conics, Parametric Equations, and Polar Coordinates Chapter 10 10 Conics, Conics, Parametric Parametric Equations, Equations, and and Polar Polar Coordinates Coordinates Chapter Chapter 10 Conics, Parametric Equations, and Polar Coordinates Chapter 10 Conics, Parametric Equations, and Polar Coordinates Exercises Seewww.CalcChat.com www.CalcChat.comfor forworked-out worked-outsolutions solutionstotoodd-numbered odd-numberedexercises. exercises. 10.4 Exercises Ejercicios See 10.4 See 10.4 www.CalcChat.com for worked-out solutions to odd-numbered exercises. See www.CalcChat.com www.CalcChat.com for for worked-out worked-out solutions solutions to to odd-numbered odd-numbered exercises. exercises. 10.4 Exercises See See www.CalcChat.com for worked-out solutions to odd-numbered exercises. 10.4 Exercises See www.CalcChat.com for worked-out solutionsc)to odd-numberedπ exercises. En los ejercicios 1 a 6, representar gráficamente el punto dado In Exercises 1– 6, plot the point in polar coordinates and find In Exercises 1– 6, plot the point in polar coordinates and find In Exercises 1–6, 6, plot the pointcoordinates in polar polar coordinates and find find en coordenadas polares y hallar las coordenadas In 1– plot the point in coordinates and In Exercises 1– 6, plot the point in polar coordinates and find theExercises corresponding rectangular for therectangulares point. the corresponding rectangular coordinates for the point. the corresponding rectangular coordinates for the the point. point. correspondientes. In corresponding Exercises 1– 6, rectangular plot the point in polar coordinates and find the coordinates for the corresponding rectangular coordinates for the point. 1. corresponding 2. s22, s8,8,ppy2 y2d 22, 5pp y3the d point. the rectangular coordinates for 1. 2. y3 1. 2. 8, p y2 22, p y3 1. sssss8, 2. sssss22, 8, p py2 y2ddddd 22, 55555p py3 y3ddddd 1. 2. 1. 2. 8, p y2 22, p y3 3. s24, 23py4d 4. s0, 27py6d 27 p y6 3. 4. p y4 1. ssss24, 2. ss0, s24, 8, p23 y2 22, y3ddddd s0, 24, 23dp py4 y4dddd 0, 275p ppy6 y6 3. 4. 27 3. 4. 24, 23 p y4 27 p y6 3. 4. !2,23 5. 6. sss0, 2.36 23, 21.57 d s23, s d ! 5. 6. 2, 2.36 21.57 s d s24, 23ddp s23, 0, 27 py6dddddd 3. ss! 4. ssss23, 5. 6. 2, 2.36 21.57 ! 5. 6. 2, 2.36 2.36 23, 21.57 ! 5. 6. 2, 21.57 5. 6. 2, 2.36 23, 21.57 s! d y4d (c) (c) (c) (c) (c) (c) d) (d) (d) (d) (d) (d) (d) 2 ππ 2π ππ2ππ2 2222π 2 0 1 3 0 In5.Exercises Exercises 7–10, use the anglela feature of21.57 a graphing graphing utility to 6. 2, 2.367–10, d de una s23, s!ejercicios d 7 ause ángulo herraEn los 10,the emplear función In use the angle feature of utility to In Exercises 7–10, angle feature of graphing utility to In Exercises 7–10, use use coordinates the angle angle feature feature of aaapoint a graphing graphing utility to In Exercises 7–10, the of utility to In Exercises 7–10, use the angle feature of a graphing utility to find the rectangular for the given in polar mienta derectangular graficación para encontrar lasthe coordenadas rectangulafind the coordinates for point given in polar find the rectangular rectangular coordinates for the theofpoint point given in in polar In del Exercises 7–10, use the angle feature a graphing utility to find the coordinates for given polar find the rectangular coordinates for the point given in polar coordinates. Plot the point. res punto dadothe en coordenadas polares. Representar gráficacoordinates. Plot point. coordinates. Plot the the point. point. find the rectangular coordinates for the point given in polar coordinates. Plot coordinates. Plot the point. 5 22 sin sin 5 44 cos cos 22uu 23. 24. sen uu mente el punto. 23. rrr5 24. rrr5 5 5 23. 24. sin cos 7. ss7,7,55ppy4 8. ss22, y4ddPlot the point. 22,11 11ppy6 y6dd coordinates. 23. 24. rrr 5 5 2222 sin sin uuuu cos ud rrr 5 5 4444 cos cos 22uu 7. 8. 23. 24. 5 sin 5 cos 23. 24. r 2 u r 4 23. 24. 5 sin 5 cos 7. 8. s 7, 5 p y4 d 22, 11 p y6 d s r 5 3 s 1 1 r 5 2 sec222uuuuu 25. 26. 7. 8. s 7, 5 p y4 d 22, 11 p y6 d s 7. 8. s 7, 5 p y4 d 22, 11 p y6 d s 25. 26. r 5 3 s 1 1 cos u d r 5 2 sec 7. 8. s 7, 5 p y4 d 22, 11 p y6 d s 9. s24.5, 3.5d 10. s9.25, 1.2d 25. 26. 5 1 cos 5 sec 23. rrrrr5 24. rrrrr5 533332ssss1111sin 522224sec cosuuuu2u 25. 26. 5 1ucos cos uuuudddd 5 sec 9. 10. 3.5 1.2 25. 26. 1 25. 26. 7. ssss24.5, 8. ssss9.25, 5 1 cos 5 sec s24.5, 7, 5py4 ddddd 22, 1.2 11 s9.25, 9. 10. 24.5, 3.5 9.25, 1.2pddddy6d 9. 10. 3.5 9. 10. 24.5, 3.5 9.25, 1.2 In the 26. rectangular to polara 25.Exercises r 5ejercicios 3s1 127–36, cos27udaconvert u rectangular r5 2 secequation En los 36, transformar la ecuación In9.Exercises the rectangular 10. coordinates s24.5, 3.511–16, d s9.25, 1.2d of a point are In Exercises 27–36, convert the rectangular equation to polar In Exercises 27–36, convert the rectangular rectangular equation equation to to polar polar In Exercises 11–16, the rectangular coordinates of aa point point are In Exercises 27–36, convert the In Exercises 27–36, convert the rectangular equation to polar form and sketch its graph. En los ejercicios 11 a 16, se dan las coordenadas rectangulares de 1059997_1004.qxp 9/2/08 3:51 PM Page 738 In Exercises 11–16, the rectangular coordinates of point are la forma polar y trazar su gráfica. In Exercises 11–16, the rectangular coordinates of a are In Exercises 11–16, the rectangular coordinates of a point are given. Plot the point and find two sets of polar coordinates for form and sketch its graph. form and sketch its graph. In Exercises 27–36, convert the rectangular equation to polar given. Plot the point and find two sets of polar coordinates for form and sketch its graph. form and sketch its graph. un punto. Localizar gráficamente el punto y hallar dos conjungiven. Plotfor the011–16, point and find two two sets setscoordinates of polar polar coordinates coordinates for In Exercises the of a point for are given. Plot the point find of given. Plot the point and find two sets of polar coordinates for the point prectangular 2 5 9 # uu <<and 27. 28. x2222 2 y2222 5 9 x2222and 1 y222sketch the point for 00 # 222p p ... del punto con 0 ≤ u < 2p. # form its graph. the point for 0 u < 2 . tos de coordenadas polares the point for u < p 2 2 2 2 27. 28. x 1 y 5 9 x 2 y 5 9 #point given. Plot the point for 00 ## uu << and 22p the point forthe p.. find two sets of polar coordinates for 27. xxx22221 28. xxx22222 1 yyy22225 5 999 22 2 yyy22225 5 999 27. 28. 27. 28. 1 5 2 1 yy2225 5 aa22 1 yy222 5 2 2ax 2ax 5 50 11. 12. s0, 26d s2, 2d for 0 # u < 2p. 29. xx22221 30. xx2222 1 the spoint 2 2 2 2 29. 30. 27. 28. x 1 y 5 9 x 2 y 5 2ax 9 5 11. 12. 2, 2 d 0, 26 d s x x 1 y 5 a 1 y 2 2ax 5 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 29. xxx 1 30. xxx 1 1 yyy 5 5 aaa 1 yyy 2 2 2ax 5 00000 26) 11. s(2, 12. s(0, 2, 22) 0, 26 26ddd 29. 30. 29. 30. 1 5 1 2 2ax 5 11. 12. 11. 12. ss2, 2, 22ddd 4d 0, 26 ss0, y 25 x 5 12 13. 14. s 23, s 4, 22 d 8 32. 10 31. 2 2 2 1 2 13. 14. 22 5 5 12 31. 32. 29. yyyyx5 30. xxxxx5 11. sss23, 12. sssss4, s23, 2, 2d444ddddd 0,22 26dddddd s4, 518888 y 5 a 5 12 12y 2 2ax 5 0 31. 32. 13. 14. 4, 22 13. 14. 23, 4, 22 31. 32. 5 5 12 31. 32. 13. 14. 13. 14. 23, 4, 22 3x 2 y 1 2 5 0 xy 5 4 34. !3 d !3d 15. ss23, 16. 21,442 3, 2 s s 33. 3x 2 1 5 xy 5 4 !3 d !d3d 33. 34. y5 x5 31. 3x 32. xy 15. 16. 2 2 2 1 5 xy 5 ! ! 13. sss21, 14. sss3, s21, 23,2 4d! s3, 4,2 22 3x 28yyyyy 1 1 22222 5 5 00000 xy 5 12 33. 34. !33 !33 15. 16. 21, 2 3dd 3, 2 3dd 5 4444 33. 34. 3x 2 1 5 xy 5 33. 34. ! ! ! 15. 16. 22 15. 16. 21, 2 3, 2 yxy 35. 3x 2 5 9x 4 34. 2 2 2 y 5 9x 35. 29x y1250 33. y3x 34. xy 5 4 In Exercises 17–20, use angle 16. feature of!a3graphing utility 22 5 15. 3d 738 Chapter 10 theConics, Parametric andtoPolar Coordinates s21, 2 ! s3, 2 dEquations, 9x 35. 35. 5 35. In Exercises 17–20, the angle feature of graphing utility to ánguloutility de una En los ejercicios 17use a the 20, angle emplear la función 19x y222dd222 2 2 99ssxx222 2 2 yy222dd 5 5 00 36. ysysyxx22225 In Exercises 17–20, use the angle feature of aaaagiven graphing utility to 5 9x 35. In Exercises 17–20, feature of graphing to In Exercises 17–20, use the angle feature of graphing utility to 1 y find one set of polaruse coordinates for the point in rectangular 2 2 2 2 2 36. y 5 9x 35. s x 1 y d 2 9 s x 2 y d 5 0 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 1 yyy ddd 2 2 999sssxxx 2 2 yyy ddd 5 5 000 36. sssxxx 21 find one set of polar coordinates for the point given in rectangular 36. 1 2 2 5 36. herramienta graficación para un deutility coordefind one set set of ofde polar coordinates forhallar the point point in rectangular rectangular In Exercises 17–20, use the angle feature of conjunto agiven graphing to find one polar coordinates for the given in find one set of polar coordinates for the point given in rectangular coordinates. 36. sx 2 1 y 22d 22 2 9sx 22 2 y 22d 5 0 coordinates. In Exercises 37– 46, convert s x 1 y d 2 9 s x 2 y d 5the 0 polar equation to rectangular 36. nadas polares del punto dado en coordenadas rectangulares. coordinates. coordinates. find one set of polar coordinates for the point given in rectangular coordinates. coordinates. In Exercises 37– 46, convert the polar equation to rectangular In Exercises 37–46, 46, convert the the polar polar equation equation to to rectangular rectangular In Exercises 37– convert In Exercises 37– 46, convert the polar equation to rectangular form andsketch sketch itsgraph. graph. ! ! 17. 18. s 3, 22 d 3 2, 3 2 See www.CalcChat.com for worked-out solutions to odd-numbered exercises. d s form and its coordinates. ! ! 17. 18. ss3, 22 dd 3 2, 3 2 s d ! ! form and sketch its graph. 17. 18. 3, 22 3 2, 3 2 form and sketch its graph. ! ! En los ejercicios 37 a 46, pasar la ecuación polar a forma recIn Exercises 37–its 46,graph. convert the polar equation to larectangular !2, !22 form and 17. sss3, 18. sss333! 3, 22 2, 333! 2ddd form and sketch sketch its graph. 7 22 5 ddd ! ! 17. 18. 17. 18. 3, 22 2, 19. ss7774,,5552dd 20. ss0,0,25 25dd r 5 4 r 5 25 37. 38. 19. 20. tangular y trazar su gráfica. form and sketch its graph. 19. 20. 17. sss7s44743, 18. ssss0, 3! 2,dddd3!2 d s0,0, ,, 5225d22d 25 5 5 25 37. 38. 19. 20. 0, 25 19. 20. 25 5 4444 5 25 25π 37. rrrr 5 38. rrrr 5 19. 20. 25 37. 38. 37. 38. 4,, 222dd (c) r 5 (d)r 5 In 4Exercises 1– 6, plot the point in polar coordinates and find 7 5 5 33sin sinuu 5 525 5cos cosuu 39. 40. r 5 r 5 39. 40. 19. 20. , 0, 25 d s s d 21. Represente Plot if the point is given in (a) rectangular s 4, 3.5 d gráficamente el punto (4, 3.5) si el punto está dado r 5 4 38. r 5 21. 37. 2 uu 25 4 2 the point r 5 3 sin u r 5 5 cos 39. 40. r 5 3 sin u r 5 525 cos 39. 40. s 4, 3.5 d r 5 3 sin u r 5 5 cos 39. 40. the corresponding rectangular coordinates for the point. r 5 3 sin u r 5 5 cos 39. 40. 21. Plot the point if the point is given in (a) rectangular s 4, 3.5 d 21. Plot Plot the point if the the point isen given in (a) (a) rectangular rectangular 4,(b) 3.5 5p uu 21. point point given in sss4, 3.5 ddd ifif 21. Plot the point the point is given in (a) rectangular 4, 3.5 coordinates and polar coordinates. a) enthe coordenadas rectangulares y b)is coordenadas polares. sen 39. 40. sin u r 5 5 cos u 5 p r 5 u u 41. 42. coordinates and (b) polar coordinates. 3 sin u 5p p and (b) polar coordinates. 5 5 41. 42. coordinates ands(b) (b)3.5 polar coordinates. 21. coordinates Plot the point given ind (a) rectangular 4, d ifcoordinates. 6 and polar coordinates and (b) polar coordinates. 5 5 41. 42. 5 5566p 5 uuuuu 41. rrrrr 5 42. uuuuu 5 2. sis22, s8, pthe y2dpoint 5py3 41. 42. 22.1.coordinates Graphical Reasoning 5 5 41. 42. 22. Razonamiento gráfico 56p 22. Graphical Reasoning coordinates and (b) polar coordinates. 22.3.Graphical Graphical Reasoning 52266csc 41. 42. 5 33usec secuu 5 csc u 43. rr 5 44. rru5 22. Reasoning 22. Graphical Reasoning s24, 23 y4d py6d to rectangular 4. s0, 27 43. 44. (a) Setuna thep window format of aa graphing graphing utility a) En herramienta de graficación, seleccionar formato de 6csc uuu r 5 3 sec u r 5 2 csc 43. 44. (a) Set the window format of utility to rectangular r 5 3 sec u r 5 2 43. 44. r 5 3 sec u r 5 2 csc 43. 44. r 5 3 sec u r 5 2 csc ucsc u 43. 44. 22. (a) Graphical Reasoning (a) Set the window format of a graphing utility to rectangular (a) Set the window format of a graphing utility to rectangular 5 sec secuutan tanuu 5 cot cotuuucsc 45. r 5 46. r 5 Set the format aapolares graphing Set the dwindow window format of graphing utility toelrectangular rectangular coordinates locateof the cursor any position off the ventana para and coordenadas yat utility colocar cursor en 5.(a)s! 6. s23, 2, 2.36 21.57 dto 5sec 3 sec u uu 5cot 2 csc u uuu 43. rrrr5 44. rrrr5 45. 46. u tan u csc coordinates and locate the cursor at any position off the 5 sec u tan 5 cot u csc 45. 46. coordinates and locate the cursor at any position off the r 5 sec u tan u r 5 cot u csc uu 45. 46. r 5 sec u tan u r 5 cot u csc 45. 46. (a)cualquier Set the window format of a graphing utility to rectangular coordinates and locate the cursor any position off the coordinates and locate thelos cursor at any position off the axes. Move the cursor and vertically. posición fuerahorizontally de ejes. at Mover el cursorDescribe en senaxes. Move the cursor horizontally and vertically. Describe In Exercises 47–56, use a graphing utility to graph r 5 sec u tan u r 5 cot u csc u the polar 45. 46. axes. Move the cursor horizontally and vertically. Describe coordinates and locate the cursor at any position off the axes. Move the cursor horizontally and vertically. Describe In Exercises 7–10, use the angle feature of a graphing utility to axes. Move the cursor horizontally and vertically. Describe anyhorizontal changes iny the coordinates of thetodo points. tido en displayed sentido vertical. Describir cambio In Exercises 47–56, use graphing utility to graph the polar In Exercises 47–56, use aaaa graphing graphing utility to graph the polar any changes in the displayed coordinates of the points. In Exercises 47–56, use polar In Exercises 47–56, use graphing utility to graph the polar equation. Find an interval foruu overutility whichto thegraph graphthe is traced any changes in the the displayed coordinates of the the points. axes. Move in the cursor horizontally andpoint vertically. Describe any changes displayed coordinates of points. find(b)the rectangular coordinates for the given in polar any changes in the displayed coordinates of the points. en las coordenadas de los puntos. equation. Find an interval for over which the graph is traced Set the window format of a graphing utility to polar u u equation. Find an interval for over which the graph is traced In Exercises 47–56, use a graphing utility to graph the u equation. Find an interval for over which the is traced u equation. Find an interval for over which the graph is traced only once. (b) Set the window format of a graphing utility to polar En los ejercicios 47 a 56, emplear una herramienta de polar grafiany the changes in theformat displayed of the points. coordinates. Plot the (b)En Set the window format ofcursor graphing utility tooff polar only once. (b) Set window of acoordinates to polar (b) Set window format of aa graphing graphing utility to polar coordinates andpoint. locate the at any utility position the b) unathe herramienta de graficación, seleccionar el formato de only once. only once. u over polar. equation. Find an intervallafor which Hallar the graph traced only once. only once. coordinates and locate the cursor at any position off the cación para representar ecuación un is intervalo coordinates and locate the cursor at any position off the (b)ventana Set the window format of a graphing utility to polar coordinates and locate the cursor at any position off the 23. 24. r 5 2 sin u r 5 4 cos 2 u coordinates and locate the cursor at any position off the axes. Move the cursor horizontally vertically. Describe coordenadas polares yand colocar en 5 22 2 2 55cos cosuu 5 33ss11 2 2 4cos cos ud 47. 48. rr 5 onlyrrr5 once. 7. s7,axes. 8. s22, 5py4Move d parathe 11vertically. py6d el cursor 5 cursor horizontally and Describe u en el 55que lauu gráfica se trace sólo una vez. para 47. 48. 2 cos 5 2 cos axes. Move the cursor horizontally and vertically. Describe 5 2 cos 55 2 44444ucos cos uuuuuddddd 47. 48. coordinates and locate theloscursor at any offsenthe axes. Move the horizontally vertically. Describe axes. Move the cursor horizontally and vertically. Describe rrrr5 222222 55sin cos uu ud rrrrr5 33334ssss211111sec 2 47. 48. 5 2 cos 5 2 cos 47. 48. any changes incursor the displayed coordinates of the points. cualquier posición fuera de ejes. and Mover elposition cursor en 25. 26. r 5 3 s 1 1 cos r 5 1 u 5 3 cos u 49. 50. any changes in the displayed coordinates of the points. 9. s24.5, 10. 3.5 d the s9.25, 1.2 d the any changes in the displayed coordinates of the points. 5 1 sin 5 33 cos cos 49. 50. any changes inythe the displayed coordinates of thetodo points. axes. Move cursor horizontally and vertically. Describe any changes coordinates of points. 522222221 2sin cos 5444443(1 31 s1 12 cos 47. rrrrrrr5 48. rrrrrrr5 any changes in the displayed coordinates of the points. 5 1 sin uuuu uu 5 1 32 uuuu uu)d 49. 50. horizontal endisplayed sentido Describir cambio 5 1 sin 5 1 cos 49. 50. 47. 5 2 55 cos 48. 5 44 sen u 3 cos u 49. 50. 5 1 sin 5 1 3 cos 49. 50. (c)tido Why are thein results in partsvertical. (a) and (b) different? 2 27–36, convert the rectangular22equation to polar (c) Why are the results in parts (a) and (b) different? any in thedein displayed of the points. In rExercises (c) Why are the results results inlos parts (a)coordinates and (b) different? different? en las changes coordenadas puntos. 5 5 51. 52. Why are the parts (a) and (b) 122222sen sin u 1 23 cos cos u 49. 50. rr5 (c) Why are the results in parts (a) and (b) different? In(c) Exercises 11–16, the rectangular coordinates of a point are 49. 50. 5 212 1 sin 5 44 1 rrr5 5 51. 52. 1 cosuuu its graph. 2 322233sin sinuuu r 5 51. 52. 5 5 4442 51. 52. rrrrr 5 form and sketch 1 1 cos 2 r 5 51. 52. r 5 5 51. 52. Ingiven. Exercises 23–26, match the graph with its polar equation. (c)¿Por Why are the results in parts (a) and (b) different? 1 1 cos u 3 sin c) qué difieren los resultados obtenidos en los incisos a) y Plot the point and find two setswith of polar coordinates for 1 cos cos 2 33322sin sin uuuu 111 1 444 2 In Exercises 23–26, match the graph its polar equation. 1 cos 2 22 3uuuu In Exercises 23–26, match the graph with its polar polar equation. equation. 5sin 5 5 51. rr 5 52. rr 5 In Exercises 23–26, match the graph with its In Exercises 23–26, match the graph with its polar equation. [The graphs are labeled (a), (b), (c), and (d).] 51. 52. b)? 3 u 5 uuu9 u the point for 0 u < 2 p . 2 2 2 2 # 211cos cos 344sin sin 53. 54. 1 cos 2 sin 333uuuu9uu usin [The graphs are labeled (a), (b), (c), and (d).] 27.rr 5 28.rr 5 x5 21 y cos 5 x5 2 y 5 1 2 335555usen u 3 [The graphs are are labeled (a), (b), (b), (c), andwith (d).]its polar equation. 3 In Exercises 23–26, match the (c), graph 53. 54. [The graphs labeled (a), and (d).] 2 [The graphs are labeled (a), (b), (c), and (d).] r 5 2 cos r 5 3 sin 5 222 cos cos 2 5 333 sin sin 22u 53. rrr 5 54. rrr 5 53. 54. 5 cos 5 sin 53. 54. π π 2 2 2 2 2 2 (a) (b) 322uua 2 522uu2ax 5 0 π gráfica con su x 29. 30. x 1 y 5 1 y 2 [The labeled (a), (b), (c), and 11. 12. sgraphs 2, 2πππ2d are23 26d πla s0, (d).] 3 5 En los ejercicios a 26, hacer que corresponda (a) (b) 5 22 cos cos 5 3311sen sin 53. rr 25 54. rr 25 π2ππ2 π2π (a) (b) sin 53. 54. (a) (b) (a) (b) 5 sin 222u 5 55. 56. 22 ecuación etiquetadas 54448sin 51111u12 22 31.rrr222222y5 32.rrr222222x5 2polar. 2222π b), c) y d).] 2π 4d [Las gráficas están(b) 13. s23, 14. s4, 22d a), 2 u 55. 56. 5 sin 2 u 5 55. 56. (a) 55. 56. 5 44 sin sin 22uu 5 uuu1 55. rr 5 56. rr 5 2 2 uu14 2 2 5 3x 1 22uequation 50 33.rConvert 34.r xy π 2 !3 d 57. the 55. 56. 2 524 ysin 2 5 a)15. s21, b)16. s3, 2 !3πd r 5 4 sin 2 u r 5u sen 55. 56. 57. Convert the equation 2 2 57. Convert the equation u 2 57. the 57. Convert the equation equation y 5 9x 35.Convert cos uequation 1 kksin sinuudd rConvert 5 22sshhcos 0 to 0 angle feature of a graphing utility In Exercises 17–20, use the 57. the u 1 r 5 0 ecuación 57. 2 2u 2 u ssshhhla 1 sin 5 h cos cos 19kkskkxsin sin 5 4 00000 4 2 s5 x 22222s1 ycos d uuu21 2uuuddydd 2d 5 0 36.rrrrPasar 5 cos 1 sin 0000 4 coordinates 2 polar find one set of for the point given in rectangular 444 to rectangular form and verify that it is the equation of a circle. 4 4444 2222 4 s h cos u 1 k sin r 5 2 0 0 sen r5 2sh cos u form 1 k sin uuverify ddverify that to rectangular and that is the equation of circle. coordinates. to rectangular form and that itcoordinates is equation the equation equation of center circle. rectangular and ititit is the of aaaa circle. to rectangular form and verify is the equation of circle. Find the radius andconvert the verify rectangular oftothe of 4 4 2 Into Exercises 37–form 46, thethat polar rectangular 0 0 Find the radius and the rectangular coordinates of the center of Find the radius and the rectangular coordinates of the center of to rectangular form and verify that it is the equation of a Find the radius and the rectangular coordinates of the center Find the radius and the rectangular coordinates of the center of the circle. form and sketch its graph. a lacircle. forma rectangular y verificar que sea la ecuación circle. deof un 4 4 17. s3, 22d2 18. s3!2, 3!2 d the the circle. the circle. Find theHallar radius el andradio the rectangular coordinates of the center the circle. the circle. círculo. y las coordenadas rectangulares de of su 19. s74, 52 d 20. s0, 25d r 5circle. 4 37. the 38. r 5 25 centro. 39. r 5 3 sin u 40. r 5 5 cos u 21. Plot the point s4, 3.5d if the point is given in (a) rectangular 5p coordinates and (b) polar coordinates. 41. r 5 u 42. u 5 6 22. Graphical Reasoning 1 2 10.4 Exercises 111 1 (a) Set the window format of a graphing utility to rectangular coordinates and locate the cursor at any position off the axes. Move the cursor horizontally and vertically. Describe 222 2 111 1 222 2 43. r 5 3 sec u 44. r 5 2 csc u 45. r 5 sec u tan u 46. r 5 cot u csc u In Exercises 47–56, use a graphing utility to graph the polar 1059997_1004.qxp 9/2/08 3:51 PM 739 Page 739 10-4.qxd 3/12/09 16:57 Page 1059997_1004.qxp 9/2/08 3:51 PM Page 739 SECCIÓN 10.4 Coordenadas polares y gráficas polares 10.4 Polar Coordinates and Polar Graphs 10.4 Polar Coordinates and Polar Graphs 58. Fórmula para la distancia 58. Distance Formula Verificar que la fórmula para la distancia entre dos puntos 58. a) Distance Formula (a)sr Verify Distance Formula for polares the distance en coordenadas es between , u1d y that sr2, uthe d dados 1 (a) Verify that the2 Distance Formula distance between r2, 2 for r1, 1 and the two points in the polar coordinates is 2 2r , r , the and in polar coordinates is !rpoints d 5two 1 r 2 2r r cos s u 2 u d . 1 1 2 2 1 2 2 2 1 2 1 2 r2 2r1 r2 cos 1 d r1 2 . b) Describir en relación uno con r22 2r1 r2de coslos 1puntos, d r12las posiciones 2 . (b)otro, Describe of the points relative to each other si u1 5theu2positions la fórmula de la distancia para . Simplificar (b) este Describe the positions of the points relative to each otherIs . forcaso. Simplify the Distance Formula for thisExplicar case. ¿Es la simplificación lo que se esperaba? 1 2 for theyou Distance Formula for this case. Is the what expected? Explain. 1simplification 2. Simplify por qué. the simplification what you expected? Explain. 90908. . Is¿Es Simplify the Distance for si1u1 22u2 5 the c)(c)Simplificar la fórmula de Formula la distancia 90qué. . Is the (c) laSimplify the Distance Formula for Explain. simplification what you expected? 1 2 por simplificación lo que se esperaba? Explicar simplification what you expected? Explain. Choose points polar coordinate systempolares and find d)(d)Elegir dostwo puntos enonelthe sistema de coordenadas y (d) encontrar Choose two points on the polar coordinate system and find the distance between them. Then choose different polar la distancia entre ellos. Luego elegir representathe distance them. polar representations of the same twochoose points different and the ciones polaresbetween diferentes paraThen los mismos dos apply puntos y representations of the same two points and apply Distance Formula again. Discuss the result.el resultado.the aplicar la fórmula para la distancia. Analizar Distance Formula again. Discuss the result. En ejercicios 62,the usar el resultado del58 ejercicio 58 para In los Exercises 59–59 62,ause result of Exercise to approximate Inthe Exercises 62, usethe thetwo result of Exercise 58 to approximate aproximar la59– distancia entre los dos puntos descritos en coordedistance between points in polar coordinates. the distance between the two points in polar coordinates. nadas polares. 5 7 59. 1,5 60. 8,7 , 4, , 5, 6 3 60. 8, 4 , 5, , 4, 59. 1, 6 3 4 61. 2, 0.5 , 7, 1.2 62. 4, 2.5 , 12, 1 61. s2, 0.5d, s7, 1.2d 62. s4, 2.5d, s12, 1d In Exercises 63 and 64, find dy/dx and the slopes of the tangent En los shown ejercicios 63 y64, 64,find hallar las pendientes las rec/dx Inlines Exercises 63 andy the slopes of thedetangent onand the graph ofdy/dx thedypolar equation. tas tangentes muestran las gráficas lines shown onque these graph of theen polar equation.de las ecuaciones 63. r 2 3 sin 64. r 2 1 sin polares. 63. r 2 3 sin 64. r 2 1 sin π u π sin sin ud 63. r 5 2 1 3 sen 64. r 5 2s1 2 πsen )() 2))) π 2 5,π π2 5, 2 2 5,2π π2 π2 2 )( ) )) ) 3π −1, 3π2 −1, −1, 3π 2 2 (2, π ) (2, π ) (2, π ) 2 2 2 3 0 0 3 3 )( ) )) ) 7π 3, 7π 3, 7π6 3, 6 6 0 (2, 0) (2, 0) 0 (2, 1 2 0)3 0 1 1 2 2 3 3 0 )) 4,33ππ32π) ) 4, ( 4, 22 ) In Exercises 65– 68, use a graphing utility to (a) graph the polar Inequation, Exercises 65– 68, graphing utility (a) graph the (b) draw the line at thetogiven of polar , and En los ejercicios 65 ause 68,atangent usar una herramienta devalue graficación y equation, (b)gráfica draw the tangent lineof at .the value , and (c) find dy/dx at the value Hint: Let the increment a) trazar la degiven la ecuación polar, b)given dibujar la of recta tan(c) find at the given of Hint: Letelthe increment between values of gente endy/dx elthe valor dado de equal valor dado de uvalue , y c) hallar / 24. . dy / dx en between the values of equal 24. / de u iguales a p / 24.c u. xSugerencia: Tomar incrementos 65. r 3 1 cos , 66. r 3 2 cos , 0 p 65. r 5 3s1 2 cos ud, u 5 2 66. r 5 3 2 2 cos u, u 5 0 2 67. r 3 sin , 68. r 4, p3 p sin u, u 5 67. r 5 3 sen 68. r 5 4, u 5 4 3 4 In Exercises 69 and 70, find the points of horizontal andhorizonvertical En los ejercicios 69 y 70, hallar los puntos de tangencia Intangency Exercises(if69 andto70, find thecurve. points of horizontal and vertical any) the polar tal y vertical (si los hay) a la curva polar. tangency (if any) to the polar curve. 69.r r5 112 sin 70.r r5 aasin sinu sinu sen sen 69. 70. 69. r 1 sin 70. r a sin Inlos Exercises 7171 and 72,hallar find the En ejercicios y 72, los points puntosof dehorizontal tangencia tangency horizonIn(ifExercises 71apolar and 72, find the points of horizontal tangency any) the curve. tal (si los to hay) la curva polar. (if any) to the polar curve. 71.r r5 22csc 72.r r5 aasin cscu 1 33 sinu cos cos2 u2 71. 72. sen 71. r 2 csc 72. r a sin cos 2 3 Inlos Exercises a graphing utility to graph the polar En ejercicios7373–76, a 76,use usar una herramienta de graficación para Inequation Exercises –76,alluse a graphing utility to puntos graph de thetangenpolar and find points horizontal representar la73 ecuación polar yofhallar todos tangency. los equation and find all points of horizontal tangency. cia horizontal. 73. r 4 sin cos 2 74. r 3 cos 2 sec 2 73. rr 5 44 sin 74. rr 5 33 cos sen u cos 73. 74. sin cos 2 u cos 22u sec sec u 739 739 739 75. 76. 75. rr 5 22 csc 76. rr 5 22 cos csc u 1 55 coss33u 2 22d 75. los r ejercicios 2 csc 775 a 84, dibujar76. 2 cos 2 En la rgráfica de3la ecuación polar Exercises 77–84, sketch a graph of the polar equation and yInhallar las tangentes en el polo. Infind Exercises 77–84, a graph of the polar equation and the tangents at sketch the pole. find tangents 77.the 78. r 5 5 cos u r5 3 sen sin u at the pole. 77. r 5 sin 78. r 5 cos r 5 2 s 1 2 sin u d s1 2 cos ud 79. 80. sen 77. r 5 sin 78. rr 553cos 79. r 2 1 sin 80. r 3 1 cos u u 81. rr 5221cos 3sin 82. rr 532sin 79. 80. 1sen 5cos 81. r 4 cos 3 82. r sin 5 r 5 3 sin 2 u r 5 3 cos 2 83. 84. sen3 81. r 4 cos 82. r sin 5 u 83. r 3 sin 2 84. r 3 cos 2 83. los r ejercicios 3 sin 2 85 a 96, trazar 84. r 3 cos En la gráfica de la2 ecuación polar. In Exercises 85–96, sketch a graph of the polar equation. r 5 8 85–96, sketch a graph 86.of rthe 5 1polar equation. In85. Exercises 85. 86. r 8 r sin u 87. r 5 4s1 1 cos ud 88. r 5 11 1 sen 85. r 8 86. r 1 87. 88. rr 5 51 2 4sin r 4 1 cos sin 89. r 5 3 2 2 cos u 90. sen u 87. r 4 1 cos 88. r 1 sin 89. r 3 2 cos 90. r 5 4 sin 6 89. 90. 91. rr 533 csc2 ucos 92. rr 55 4 sin6 2 sin u 2 3 cos u sen 91. r 3 csc 92. r 6 3 cos 91. r 3 csc 92. r 12 sin 3 cos 93. r 5 2u 94. r 521sin 93. r 2 94. r 1u 93. 94. 95. rr 2 52 4 cos 2u 96. rr 2 5 4 sin sen u 95. r 2 4 cos 2 96. r 2 4 sin 2 En unarherramienta de graficación 95. los r 2 ejercicios 4 cos 2 97 a 100, usar 96. 4 sin para representar la ecuación y mostrarutility que latorecta dada una In Exercises 97–100, use a graphing graph the es equaIn Exercises usegiven a graphing utility to graph the graph. equaasíntota la97–100, gráfica. tion andde show that the line is an asymptote of the tion and show that the given line is an asymptote of the graph. Nombre la gráfica Polar Ecuación polar Asíntota Name ofde Graph Equation Asymptote Name of Graph Polar Equation Asymptote r 5 2 2 sec u 97. Concoide 97. Conchoid r 2 sec x x 5 21 1 97. Conchoid r 2 sec x 1 1 csc u 98. 98. Concoide Conchoid r r 25 2 csc y y 51 1 98. Conchoidhiperbólica r r2 5 2y cscu y y 15 2 99. 99. Espiral Hyperbolic spiral r 2 y 2 99. Hyperbolic spiral r 2 2 cos u sec u y x x 25 22 100. 100. Estrofoide Strophoid r r 25cos 2 2sec 2 100. Strophoid r 2 cos 2 sec x 2 Desarrollo de WRITING ABO U Tconceptos CONCEPTS W101. R I T Describe I N G A Bthe O Udifferences T C O N C between E P T S the rectangular coordinate 101. Describir las diferencias entre el sistema de coordenadas 101. Describe the differences between the rectangular coordinate system and the polar coordinate system. rectangulares y el sistema de coordenadas polares. system and the polar coordinate system. 102. Dar Givelastheecuaciones equations para for the coordinate conversion from 102. pasar de coordenadas rectangu102. Give the equations for the coordinate conversion from rectangular to polar coordinates and vice versa. lares a coordenadas polares y viceversa. rectangular to polar coordinates and vice versa. 103. ¿Cómo How are slopes oflastangent linesdedetermined in polar 103. se the determinan pendientes rectas tangentes en 103. How are the slopes tangent lines determined polar coordinates? What of are¿Qué tangent at thetangentes pole in and how coordenadas polares? son lines las rectas en el coordinates? What are tangent lines at the pole and how are they determined? polo y cómo se determinan? are they determined? Para C A P S Tdiscusión ONE C104. A P S Describe T O N E las lasfollowing siguientespolar ecuaciones polares. 104. Describir the gráficas graphs ofdethe equations. 104. Describe the graphs of the following polar equations. a) r 7 b) r2 7 a) r 7 b) r2 7 7 7 c) r d) r 7 7 cos sen c) r d) r 7 cos 7 sen e) r cos f ) r sen e) r 7 cos f ) r 7 sen sin u en el intervalo dado. 105. Trazar la gráfica de r 5 4 sen 105. Sketch the graph of r 4 sin over each interval. 105. Sketch the graph p of r p4 sin over each interval. p p ≤ u ≤ p a) 0 ≤ u ≤ b) c) 2 ≤ u ≤ (a) 0 (b)2 (c) 2 2 2 2 2 2 (a) 0 (b) 2 (c) 2 herramienta graficadora 2 para repre2 106. Para pensar 2 Utilizar una 106. Think About It Use a graphing utility to graph the polar sentar About la ecuación polar r 5 6 futility 1 1 cossu 2 fdgthepara a) 106. Think a graphing polar4, equation r It6 1Usecos for (a) to graph 0, (b) f 5 0, f 5 p y4, f 5 p y2. b) y c) Usar las gráficas para equation cos the graphsforto(a) (b)effect of 4, and (c) r 6 12. Use describe0,the the describir efecto del ángulo la ecuación como funf. Escribir and (c) . el the graphs describe of the angle Write2.theUse equation as a to function of the sin effect for part (c). ción de. sen el inciso as u para c).a function of sin for part (c). angle Write the equation 740 16:57 Page 740 9/2/08 3:51 PM CAPÍTULO 10 740 Chapter 10 Page 740 Cónicas, ecuaciones paramétricas y coordenadas polares Conics, Parametric Equations, and Polar Coordinates 107. Verificar que si la curva correspondiente a la ecuación polar r 5 f sud gira un ángulo f, alrededor del polo, entonces la 107. Verify de thatla ifcurva the curve is r 5 f sud is ecuación girada whose es r 5 polar f su 2equation fd. rotated about the pole through an angle f, then an equation for 108. Lathe forma polar de una sen ud. rotated curve is r ecuación 5 f su 2 de fd.una curva es r 5 f ssin Comprobar que la forma se convierte en 108. The polar form of an equation of a curve is r 5 f ssin ud. Show a) r 5 f s2cos ud si la curva gira py2 radianes alrededor del that the form becomes polo en sentido contrario a las manecillas del reloj. s2cos (a) f sen the gira curve is rotatedalrededor counterclockwise b) r 5r f5 del polo s2sin ud siudla ifcurva p radianes p y2 radians about the pole. en sentido contrario a las manecillas del reloj. f s2sin the curve rotated counterclockwise c) (b) gira 3is radianes alrededor delp r 5rf5 scos ud si ulad ifcurva py2 radians about the pole. polo en sentido contrario a las manecillas del reloj. (c) r 5 f scos ud if the curve is rotated counterclockwise 3py2 En los ejercicios a 112, usar los resultados de los ejercicios radians109 about the pole. 107 y 108. In Dar Exercises 109–112, use the rresults Exercises 107 u después la ecuación del caracol deand girar108. la 5 2 2ofsen sin 109. cantidad indicada. Utilizar una herramienta de graficación para 109. Write an equation for the limaçon r 5 2 2 sin u after it has representar el giro del caracol. been rotated by the given amount. Use a graphing utility to p p 3p limaçon. a) graph the b) rotated c) p d) 4 2 2 p 3p p p rosa (b) para la (c)curva (d) r 5 2 sen 110. Dar(a)una ecuación sin 2u después de 4 2 2 girar la cantidad dada. Verificar los resultados usando una herrau after 5 2desin 110. Writedeangraficación equation for rose curve it has mienta parathe representar el rgiro la 2curva rosa. been rotated by the given amount. Verify the results by using p p 2p to graph the rose curve. a) a graphing b) utility c) d)rotated p 6 2 3 p p 2 p 111. Dibujar (a) la gráfica (b) de cada (c)ecuación. (d) p 6 2 3 p a) b) r 5 1 2 sin u r 5 1 2 sen sin u 2 sen 111. Sketch the graph of each equation. 4 p 2 la sintangente u 5 1 2csin (a) r 5 1que (b) 112. Demostrar delr ángulo 5 u0 2 # c4 # py2) entre la recta radial y la recta tangente en el punto sr, ud en la gráfica 112. Prove that the tangent of the angle c s0 # c # py2d between de r 5 fsud (ver la figura) está dada por tan c 5 urysdrydudu. the radial line and the tangent line at the point sr, ud on the πgraph of r 5 f sud (see figure) is given by tan c 5 rysdrydud . 1 1 2 2 | 2 π Curva polar: r 2= f (θ ) Polar curve r = f (θ ) Recta tangente ψ Tangent line Recta radial ψ P = (r, θ ) Radial line P = (r, θ ) θ O O | θ 0 A Eje polar A 0 Polar axis En los ejercicios 113 a 118, usar los resultados del ejercicio 112 para hallar el ángulo entre rectas y tangente a la c use In Exercises 113–118, thelasresult of radial Exercise 112 to find the gráfica en el valor indicado de Usar una herramienta de grafiu . angle c between the radial and tangent lines to the graph for cación para representar polar, de la rectatoradial y la the indicated value oflauecuación utility graph the . Use a graphing recta tangente en elthe valor indicado ángulo u. Identificar . polar equation, radial line, de and the tangentel line for cthe indicated value of u. Identify the angle c. Ecuación polar Valor de u Polar Equation Value of u 113. r 5 2s1 2 cos ud u5p 113. r 5 2s1 2 cos ud u5p u 5 3py4 114. r 5 3s1 2 cos ud 114. r 5 3s1 2 cos ud u 5 3py4 u 5 py4 115. r 5 2 cos 3u u 5 py4 115. r 5 2 cos 3u sin 2u u 5 py6 116. r 5 4 sen u 5 py6 116. r 5 4 sin 2u 6 u 5 2py3 117. r 5 1 2 cos6 u u 5 2py3 117. r 5 1 2 cos u u 5 py6 118. r 5 5 u 5 py6 118. r 5 5 ¿Verdadero o falso? En los ejercicios 119 a 122, determinar si la afirmación es verdadera o falsa. Si es falsa, explicar por qué o True or False? In Exercises 119–122, determine whether the dar un ejemplo que muestre que es falsa. statement is true or false. If it is false, explain why or give an 119. Si sr1,that representan el mismo punto en el sistema u1d yshows sr2, u2itd is example false. de coordenadas polares, entonces r1 5 r2 . 119.SiIfsr,sru1, duy1d sr, and the same the polar 2, u2d represent 120. el mismo puntopoint en elon sistema de u2dsrrepresentan 1 r 5 r . coordinate system, then 1 2 coordenadas polares, entonces u1 5 u2 1 2p n para algún en120.tero If sn.r, u1d and sr, u2d represent the same point on the polar u1 5sx,u2yd1en 2peln sistema n. system,elthen for somede integer 121. Sicoordinate punto coordex > 0, entonces | | | | | | | | rectangulares cartesianas) puede representarse me0, then the (o sx, yd on the 121.nadas If x > point rectangular coordinate diante el sistema de polares, donde ud en r, ud on the polar systemsr,can be represented by scoordenadas coordinate 2 d. u 5 arctans yyxd. !x 2 1 r5 y 2 yru55! arctan x 2 1s yyyx system, where and 122. ecuaciones r 5 sen u y2ur, 5 r2sen 2u tienen la r 5 2sin 5 2sin 2u, and 122.Las The polar polares equations misma gráfica. s22ud all have the same graph. r 5 sin PROYECTO S E C T I ODE N TRABAJO PROJECT Anamorphic Art Arte anamórfico the art se is viewed art appears distorted, but when ElAnamorphic arte anamórfico parece distorsionado, pero cuando ve desdefrom un a particular point or is viewed with a device such as a mirror, particular punto de vista o con un dispositivo como un espejo pareceit appears to be normal. Use the anamorphic transformations que está normal. Usar las siguientes transformaciones anamórficas 3 p p 3p p 3 p 3 p r 5y y111616 y and u 5u25 2 r5 x, 8 x,2 2 ≤4 u #≤ u # 4 8 4 4 to sketch transformed polar image of rectangular graph. para dibujar the la imagen polar transformada de the la gráfica rectangular. When the reflection (in a cylindrical mirror centered at the pole) Cuando se observa la reflexión (en un espejo cilíndrico centrado enof image is viewed axis,elthe viewer will eleach polo)polar de una imagen polar from desdethe el polar eje polar, espectador ve see la the original rectangular image. imagen rectangular original. 2 1xs2y1 2 5 y5 5 x(d) 5d52 25 52 3 3 b) (b) x 5x 25 2c) (c) y 5yx5 1x51 d) 2s 5y d2 a)(a)y 5 Tomado Millington-Barnard Collection Scientific Apparatus, ca From thedeMillington-Barnard Collection of of Scientific Apparatus, ca 1855 1855 The University of Mississippi Museum, Oxford, Mississippi. The University of Mississippi Museum, Oxford, Mississippi 10-4.qxd 3/12/09 1059997_1004.qxp Este ejemplo deof arteanamorphic anamórficoart es isdefrom la Colección MillingtonThis example the Millington-Barnard Barnard en laatUniversidad de Mississippi. Cuando observa el reflejo Collection the University of Mississippi. Whensethe reflection of dethe la “pintura polar”transformada espejo, veviewer el arte transformed “polar painting”en is el viewed in eltheespectador mirror, the distorsionado en susart proporciones sees the distorted in its properadecuadas. proportions. ■ FOR FURTHER INFORMATION For more information on PARA MAYOR INFORMACIÓN Para más información sobre anamorphic art, see the article “Anamorphisms” by Philip Hickin in arte anamórfico, consultar al artículo “Anamorphisms” de Philip the Mathematical Gazette. Hickin en Mathematical Gazette. 10-5.qxd 3/12/09 16:58 Page 741 SECCIÓN 10.5 SECCIÓN 10.5 Área y longitud de arco en coordenadas polares Área y longitud de arco en coordenadas polares 741 741 10.5 Área y longitud de arco en coordenadas polares n n n n Hallar el área de una región limitada por una gráfica polar. Hallar los puntos de intersección de dos gráficas polares. Hallar la longitud de arco de una gráfica polar. Hallar el área de una superficie de revolución (forma polar). Área de una región polar θ r El área de un sector circular es A 5 12u r 2. Figura 10.49 El desarrollo de una fórmula para el área de una región polar se asemeja al del área de una región en el sistema de coordenadas rectangulares (o cartesianas), pero en lugar de rectángulos se usan sectores circulares como elementos básicos del área. En la figura 10.49, 1 obsérvese que el área de un sector circular de radio r es 2u r 2, siempre que u esté dado en radianes. Considérese la función dada por r 5 f sud, donde f es continua y no negativa en el intervalo a ≤ u ≤ b. La región limitada por la gráfica de f y las rectas radiales u 5 a y u 5 b se muestra en la figura 10.50a. Para encontrar el área de esta región, se hace una partición del intervalo fa, bg en n subintervalos iguales a 5 u0 < u1 < u2 < . . . < un21 < un 5 b. A continuación, se aproxima el área de la región por medio de la suma de las áreas de los n sectores, como se muestra en la figura 10.50b. π 2 β RadioRadius del i-ésimo of ith sector 5 f suid b2a ÁnguloCentral central angle del i-ésimo of ith sector 5 5 Du n n 1 A< Du f f sui dg 2 2 i51 r = f(θ ) o1 2 Tomando el límite cuando n → ` se obtiene 1 n f f sui dg 2 Du n→ ` 2 i51 o A 5 lím lim α 0 5 1 2 E b a f f sudg 2 du lo cual conduce al teorema siguiente. a) π 2 β θn − 1 TEOREMA 10.13 ÁREA EN COORDENADAS POLARES r = f(θ ) Si f es continua y no negativa en el intervalo fa, bg, 0 < b 2 a ≤ 2p, entonces el área de la región limitada (o acotada) por la gráfica de r 5 f sud entre las rectas radiales u 5 a y u 5 b está dada por θ2 θ1 A5 1 2 5 1 2 α 0 E E b a b a f f sudg 2 du r 2 du. 0 < b 2 a ≤ 2p. b) Figura 10.50 NOTA La misma fórmula se puede usar para hallar el área de una región limitada por la gráfica de una función continua no positiva. Sin embargo, la fórmula no es necesariamente válida si f toma valores tanto positivos como negativos en el intervalo fa, bg. n 10-5.qxd 3/12/09 742 16:58 Page 742 CAPÍTULO 10 Cónicas, ecuaciones paramétricas y coordenadas polares Encontrar el área de una región polar EJEMPLO 1 r = 3 cos 3θ π 2 Encontrar el área de un pétalo de la curva rosa dada por r 5 3 cos 3u. Solución En la figura 10.51 se puede ver que el pétalo al lado derecho se recorre a medida que u aumenta de 2 py6 a py6. Por tanto, el área es A5 0 3 1 2 E b a r 2 du 5 1 2 5 9 2 E E py6 2py6 py6 1 1 cos 6u du 2 2py6 9 sin 6u sen u1 4 6 9 p p 5 1 4 6 6 3p 5 . 4 3 1 5 El área de un pétalo de la curva rosa que se encuentra entre las rectas radiales u 5 2 p y6 y u 5 p y6 es 3p y4. Figura 10.51 Fórmula para el área en coordenadas polares. s3 cos 3ud2 du Identidad trigonométrica. py6 4 2py6 2 NOTA Para hallar el área de la región comprendida dentro de los tres pétalos de la curva rosa del ejemplo 1, no se puede simplemente integrar entre 0 y 2p. Si se hace así, se obtiene 9py2, que es el doble del área de los tres pétalos. Esta duplicación ocurre debido a que la curva rosa es trazada dos veces cuando u aumenta de 0 a 2p. n Hallar el área limitada por una sola curva EJEMPLO 2 Hallar el área de la región comprendida entre los lazos interior y exterior del caracol r 5 1 2 2 sen sin u. Solución En la figura 10.52, obsérvese que el lazo interior es trazado a medida que u aumenta de py6 a 5py6. Por tanto, el área comprendida por el lazo interior es p 2 A1 5 u =p 6 u = 5p 6 2 3 1 2 E b a r 2 du 5 1 2 5 1 2 5 1 2 5 1 2 0 r = 1 − 2 sen u El área entre los lazos interior y exterior es aproximadamente 8.34 Figura 10.52 E E E E 5py6 py6 5py6 py6 5py6 py6 5py6 py6 sen u 1 4 sen s1 2 4 sin sin22 ud du 1 2 cos 2u sin u 1 4 1 31 2 4 sen 24 du 2 s3 2 4 sen sin u 2 2 cos 2ud du 3 1 3u 1 4 cos u 2 sen sin 2u 2 1 5 s2p 2 3!3 d 2 3!3 5p2 . 2 5 Fórmula para el área en coordenadas polares. s1 2 2 sen sin ud2 du Identidad trigonométrica. Simplificación. 5py6 4 py6 De manera similar, se puede integrar de 5py6 a 13py6 para hallar que el área de la región comprendida por el lazo exterior es A2 5 2p 1 s3!3y2d. El área de la región comprendida entre los dos lazos es la diferencia entre A2 y A1. 1 A 5 A2 2 A1 5 2p 1 2 1 2 3!3 3!3 2 p2 5 p 1 3!3 < 8.34 2 2 10-5.qxd 3/12/09 16:58 Page 743 SECCIÓN 10.5 Área y longitud de arco en coordenadas polares 743 Puntos de intersección de gráficas polares Debido a que un punto en coordenadas polares se puede representar de diferentes maneras, hay que tener cuidado al determinar los puntos de intersección de dos gráficas. Por ejemplo, considérense los puntos de intersección de las gráficas de r 5 1 2 2 cos u y r51 mostradas en la figura 10.53. Si, como se hace con ecuaciones rectangulares, se trata de hallar los puntos de intersección resolviendo las dos ecuaciones en forma simultánea, se obtiene r 5 1 2 2 cos u 1 5 1 2 2 cos u cos u 5 0 p 3p . u5 , 2 2 PARA MAYOR INFORMACIÓN Para más información sobre el uso de la tecnología para encontrar puntos de intersección, consultar el artículo “Finding Points of Intersection of Polar-Coordinate Graphs” de Warren W. Esty en Mathematics Teacher. Primera ecuación. Sustitución de r 5 1 de la segunda ecuación en la primera ecuación. Simplificación. Despejar u. Los puntos de intersección correspondientes son s1, py2d y s1, 3py2d. Sin embargo, en la figura 10.53 se ve que hay un tercer punto de intersección que no apareció al resolver simultáneamente las dos ecuaciones polares. (Ésta es una de las razones por las que es necesario trazar una gráfica cuando se busca el área de una región polar.) La razón por la que el tercer punto no se encontró es que no aparece con las mismas coordenadas en ambas gráficas. En la gráfica de r 5 1, el punto se encuentra en las coordenadas s1, pd, mientras que en la gráfica de r 5 1 2 2 cos u, el punto se encuentra en las coordenadas s21, 0d. El problema de hallar los puntos de intersección de dos gráficas polares se puede comparar con el problema de encontrar puntos de colisión de dos satélites cuyas órbitas alrededor de la Tierra se cortan, como se ilustra en la figura 10.54. Los satélites no colisionan mientras lleguen a los puntos de intersección en momentos diferentes (valores de u). Las colisiones sólo ocurren en los puntos de intersección que sean “puntos simultáneos”, puntos a los que llegan al mismo tiempo (valor de u). Puesto que el polo puede representarse mediante s0, ud, donde u es cualquier ángulo, el polo debe verificarse por separado cuando se buscan puntos de intersección. n NOTA p 2 Caracol: r 5 1 2 2 cos u Círculo: r51 0 1 Tres puntos de intersección: s1, p y 2d, s2 1, 0d, s1, 3p y 2d Las trayectorias de los satélites pueden cruzarse sin causar colisiones Figura 10.53 Figura 10.54 10-5.qxd 3/12/09 744 16:58 Page 744 CAPÍTULO 10 Cónicas, ecuaciones paramétricas y coordenadas polares Hallar el área de la región entre dos curvas EJEMPLO 3 Hallar el área de la región común a las dos regiones limitadas por las curvas siguientes. Circunferencia. r 5 2 2 2 cos u Cardioide. Solución Debido a que ambas curvas son simétricas respecto al eje x, se puede trabajar con la mitad superior del plano (o semiplano superior), como se ilustra en la figura 10.55. La región sombreada en gris se encuentra entre la circunferencia y la recta radial u 5 2py3. Puesto que la circunferencia tiene coordenadas s0, py2d en el polo, se puede integrar entre py2 y 2py3 para obtener el área de esta región. La región sombreada en rojo está limitada por las rectas radiales u 5 2py3 y u 5 p y la cardioide. Por tanto, el área de esta segunda región se puede encontrar por integración entre 2py3 y p. La suma de estas dos integrales da el área de la región común que se encuentra sobre la recta radial u 5 p. lo Círcu p 2 Car dio i de 2p 3 r 5 26 cos u 0 Región entre la cardioide y las rectas radiales u 5 2py3 y u 5 p Región entre la circunferencia y la recta radial u 5 2py3 A 1 5 2 2 4p 3 Círculo: r = −6 cos u Cardioide: r = 2 − 2 cos u E E E 2py3 py2 2py3 5 18 Figura 10.55 59 s26 cos ud2 du 1 py2 2py3 py2 cos2 u du 1 1 2 E 1 2 p 2py3 p 2py3 s1 1 cos 2ud du 1 2py3 E s2 2 2 cos ud2 du s4 2 8 cos u 1 4 cos2 ud du E p 2py3 s3 2 4 cos u 1 cos 2ud du p sin 2u sin 2u sen sen 1 3u 2 4 sen sin u 1 2 py2 2 2py3 !3 2p !3 p 59 2 2 1 3p 2 2p 1 2!3 1 3 4 2 4 5p 5 2 < 7.85 3 59 u1 1 4 3 4 2 1 2 Por último, multiplicando por 2 se concluye que el área total es 5p. NOTA Para verificar que el resultado obtenido en el ejemplo 3 es razonable, adviértase que el área de la región circular es p r 2 5 9p. Por tanto, parece razonable que el área de la región que se encuentra dentro de la circunferencia y dentro de la cardioide sea 5p. n Para apreciar la ventaja de las coordenadas polares al encontrar el área del ejemplo 3, considérese la integral siguiente, que da el área en coordenadas rectangulares (o cartesianas). A 5 2 E 23y2 24 !2!1 2 2x 2 x2 2 2x 1 2 dx 1 E 0 23y2 !2x 2 2 6x dx Emplear las funciones de integración de una herramienta de graficación para comprobar que se obtiene la misma área encontrada en el ejemplo 3. 10-5.qxd 3/12/09 16:58 Page 745 SECCIÓN 10.5 Área y longitud de arco en coordenadas polares 745 Longitud de arco en forma polar NOTA Cuando se aplica la fórmula de la longitud de arco a una curva polar, es necesario asegurarse de que la curva esté trazada (se recorra) sólo una vez en el intervalo de integración. Por ejemplo, la rosa dada por r 5 cos 3u está trazada (se recorre) una sola vez en el intervalo 0 ≤ u ≤ p, pero está trazada (se recorre) dos veces en el intervalo 0 ≤ u ≤ 2p. n La fórmula para la longitud de un arco en coordenadas polares se obtiene a partir de la fórmula para la longitud de arco de una curva descrita mediante ecuaciones paramétricas. (Ver el ejercicio 89.) TEOREMA 10.14 LONGITUD DE ARCO DE UNA CURVA POLAR Sea f una función cuya derivada es continua en un intervalo a ≤ u ≤ b. La longitud de la gráfica de r 5 f sud, desde u 5 a hasta u 5 b es s5 E b a E! b a r2 1 1ddru2 2 du. Encontrar la longitud de una curva polar EJEMPLO 4 r = 2 − 2 cos θ !f f sudg2 1 f f9sudg 2 du 5 Encontrar la longitud del arco que va de u 5 0 a u 5 2p en la cardioide π 2 r 5 f sud 5 2 2 2 cos u que se muestra en la figura 10.56. 0 1 Solución Como f9sud 5 2 sen sin u, se puede encontrar la longitud de arco de la siguiente manera. s5 Figura 10.56 5 E E b a !f f sudg 2 1 f f9 sudg 2 du 2p Fórmula para la longitud de arco de una curva polar. !s2 2 2 cos ud2 1 s2 sin sen ud2 du 0 5 2!2 E E! 2p !1 2 cos u du Simplificación. 0 5 2!2 E 2p u 2 sen sin22 du 2 0 Identidad trigonométrica. 2p u sin du sen 2 2p u 5 8 2cos 2 0 5 8s1 1 1d 5 16 54 sin sen 0 3 u ≥ 0 para 0 ≤ u ≤ 2p. 2 4 En el quinto paso de la solución, es legítimo escribir !2 sen sin22suy2d 5 !2 usen sinsu(y2 uYd2)u en lugar de | | !2 sen sin2suy2d 5 !2 sen sins(u(uuy2 d YY2) usen 2)u porque sen sinsuy2d ≥ 0 para 0 ≤ u ≤ 2p. NOTA Empleando la figura 10.56 se puede ver que esta respuesta es razonable mediante comparación con la circunferencia de un círculo. Por ejemplo, un círculo con radio 52 tiene una circunferencia de 5p < 15.7. n 10-5.qxd 3/12/09 746 16:58 Page 746 CAPÍTULO 10 Cónicas, ecuaciones paramétricas y coordenadas polares Área de una superficie de revolución La versión, en coordenadas polares, de las fórmulas para el área de una superficie de revolución se puede obtener a partir de las versiones paramétricas dadas en el teorema 10.9, usando las ecuaciones x 5 r cos u y y 5 r sen sin u. TEOREMA 10.15 ÁREA DE UNA SUPERFICIE DE REVOLUCIÓN Sea f una función cuya derivada es continua en un intervalo a ≤ u ≤ b . El área de la superficie generada por revolución de la gráfica de r = f(u), desde u 5 a hasta u = b , alrededor de la recta indicada es la siguiente. NOTA Al aplicar el teorema 10.15, hay que verificar que la gráfica de r 5 f sud se recorra una sola vez en el intervalo a ≤ u ≤ b. Por ejemplo, la circunferencia dada por r 5 cos u se recorre sólo una vez en el intervalo 0 ≤ u ≤ p. n E E b 1. S 5 2p a b 2. S 5 2p a f sud sen sin u!f f sudg2 1 f f9sudg2 du Alrededor del eje polar. f sud cos u!f f sudg 2 1 f f9sudg 2 du Alrededor de la recta u 5 p . 2 Hallar el área de una superficie de revolución EJEMPLO 5 Hallar el área de la superficie obtenida por revolución de la circunferencia r 5 ƒ(u) 5 cos u alrededor de la recta u 5 py2, como se ilustra en la figura 10.57. p 2 π 2 r = cos θ 0 1 0 Toro a) b) Figura 10.57 Solución Se puede usar la segunda fórmula dada en el teorema 10.15 con f9(u ) 5 2sen u. Puesto que la circunferencia se recorre sólo una vez cuando u aumenta de 0 a p, se tiene E E E E b S 5 2p a p 5 2p f sud cos u!f f sudg 2 1 f f9sudg 2 du Fórmula para el área de una superficie de revolución. cos u scos ud!cos2 u 1 sen sin2 u du 0 p 5 2p cos2 u du Identidad trigonométrica. 0 5p p s1 1 cos 2ud du 0 3 5p u1 sin sen 2u 2 p 4 0 5 p 2. Identidad trigonométrica. 10-5.qxd 3/12/09 16:58 Page 747 SECCIÓN 10.5 747 Área y longitud de arco en coordenadas polares 10.5 Ejercicios En los ejercicios 1 a 4, dar una integral que represente el área de la región sombreada que se muestra en la figura. No evaluar la integral. 1. r 2. r 5 cos 2u 4 sen π 2 π 2 En los ejercicios 25 a 34, hallar los puntos de intersección de las gráficas de las ecuaciones. 25. r 5 1 1 cos u 26. r 5 3s1 1 sen sin ud r 5 1 2 cos u r 5 3s1 2 sen sin ud π 2 π 2 0 0 0 1 1 3 5 0 1 3. r 3 2 3 4. r 5 1 2 cos 2u 2 sen π 2 27. r 5 1 1 cos u π 2 28. r 5 2 2 3 cos u r 5 1 2 sen sin u r 5 cos u π 2 π 2 0 1 2 3 4 0 1 2 0 0 1 1 En los ejercicios 5 a 16, hallar el área de la región. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. 11. 12. 13. 14. 15. 16. Interior de r 5 6 sen u Interior de r 5 3 cos u Un pétalo de r 5 2 cos 3u Un pétalo de r 5 4 sen 3u Un pétalo de r 5 sen 2u Un pétalo de r 5 cos 5u Interior de r 5 1 2 sen u Interior de r 5 1 2 sen u (arriba del eje polar) Interior de r 5 5 1 2 sen u Interior de r 5 4 2 4 cos u Interior de r2 5 4 cos 2u Interior de r2 5 6 sen 2u En los ejercicios 17 a 24, emplear una herramienta de graficación para representar la ecuación polar y encontrar el área de la región indicada. 17. 18. 19. 20. 21. 22. 23. 24. Lazo interior de r 5 1 1 2 cos u Lazo interior de r 5 2 2 4 cos u Lazo interior de r 5 1 1 2 sen u Lazo interior de r 5 4 2 6 sen u Entre los lazos de r 5 1 1 2 cos u Entre los lazos de r 5 2 (1 1 2 sen u) Entre los lazos de r 5 3 2 6 sen u 1 Entre los lazos de r 2 cos 29. r 5 4 2 5 sen sin u 30. r 5 1 1 cos u r 5 3 sen sin u r 5 3 cos u 31. r 5 u 2 r52 33. r 5 4 sen sin 2u r51 32. u 5 p 4 r52 34. r 5 3 1 sin sen u r 5 2 csc u En los ejercicios 35 y 36, emplear una herramienta de graficación para aproximar los puntos de intersección de las gráficas de las ecuaciones polares. Confirmar los resultados en forma analítica. 35. r 5 2 1 3 cos u r5 sec u 2 36. r 5 3s1 2 cos ud r5 6 1 2 cos u Redacción En los ejercicios 37 y 38, usar una herramienta de graficación para hallar los puntos de intersección de las gráficas de las ecuaciones polares. En la ventana, observar cómo se van trazando las gráficas. Explicar por qué el polo no es un punto de intersección que se obtenga al resolver las ecuaciones en forma simultánea. 37. r 5 cos u r 5 2 2 3 sen sin u 38. r 5 4 sen sin u r 5 2s1 1 sen sin ud 10-5.qxd 3/12/09 748 16:58 Page 748 CAPÍTULO 10 Cónicas, ecuaciones paramétricas y coordenadas polares En los ejercicios 39 a 46, emplear una herramienta de graficación para representar las ecuaciones polares y hallar el área de la región dada. 39. Interior común a r 5 4 sen sin 2u y r 5 2 40. Interior común a r 5 3s1 1 cos sin ud y r 5 23s1 2 cos sin ud sen u 41. Interior común a r 5 3 2 2 sen sin u y r 5 23 1 2 sin sen u y r 5 5 2 3 cos u 42. Interior común a r 5 5 2 3 sin 43. Interior común a r 5 4 sin sen u y r 5 2 44. Interior común de r 5 2 cos u y r 5 2 sen u 45. Interior r 5 2 cos u y exterior r 5 1 46. Interior r 5 3 sen u y exterior r 5 1 1 sen u En los ejercicios 47 a 50, hallar el área de la región. 47. En el interior de r 5 as1 1 cos ud y en el exterior de r 5 a cos u 48. En el interior de r 5 2a cos u y en el exterior de r 5 a 49. Interior común a r 5 as1 1 cos ud y r 5 a sen sin u 50. Interior común a r 5 a cos u y a r 5 a sen u donde a > 0 51. Radiación de una antena La radiación proveniente de una antena de transmisión no es uniforme en todas direcciones. La intensidad de la transmisión proveniente de una determinada antena se describe por medio del modelo r 5 a cos2 u. a) Transformar la ecuación polar a la forma rectangular. b) Utilizar una herramienta de graficación para trazar el modelo con a 5 4 y a 5 6. c) Hallar el área de la región geográfica que se encuentra entre las dos curvas del inciso b). 52. Área El área en el interior de una o más de las tres circunferencias entrelazadas r 5 2a cos u, r 5 2a sen sin u, y r 5 a está dividida en siete regiones. Hallar el área de cada región. En los ejercicios 61 a 66, utilizar una herramienta de graficación para representar la ecuación polar sobre el intervalo dado. Emplear las funciones de integración de una herramienta de graficación para estimar la longitud de la curva con una precisión de dos decimales. 61. r 5 2u, 0 ≤ u ≤ 1 63. r 5 , u p 2 62. r 5 sec u, p ≤ u ≤ 2p sins3 cos ud, 65. r 5 sen sins2 cos ud, 66. r 5 2 sen 64. r 5 eu, 0 ≤ u ≤ p 3 0 ≤ u ≤ p 0 ≤ u ≤ p 0 ≤ u ≤ p En los ejercicios 67 a 70, encontrar el área de la superficie generada por revolución de la curva en torno a la recta dada. Ecuación polar Intervalo Eje de revolución 67. r 5 6 cos u p 0 ≤ u ≤ 2 Eje polar 68. r 5 a cos u 0 ≤ u ≤ p 2 u5 p 2 69. r 5 eau 0 ≤ u ≤ p 2 u5 p 2 70. r 5 as1 1 cos ud 0 ≤ u ≤ p Eje polar En los ejercicios 71 y 72, usar las funciones de integración de una herramienta de graficación para estimar, con una precisión de dos cifras decimales, el área de la superficie generada por revolución de la curva alrededor del eje polar. 71. r 5 4 cos 2u, 0 ≤ u ≤ p 4 72. r 5 u, 0 ≤ u ≤ p 53. Conjetura Hallar el área de la región limitada por r 5 a cossnud Desarrollo de conceptos para n 5 1, 2, 3, . . . Con base en los resultados formular una conjetura acerca del área limitada por la función cuando n es par y cuando n es impar. 73. Explicar por qué para encontrar puntos de intersección de gráficas polares es necesario efectuar un análisis además de resolver dos ecuaciones en forma simultánea. 54. Área Dibujar la estrofoide p p r 5 sec u 2 2 cos u, 2 < u < . 2 2 Transformar estas ecuaciones a coordenadas rectangulares (o cartesianas). Encontrar el área comprendida en el lazo. En los ejercicios 55 a 60, hallar la longitud de la curva sobre el intervalo indicado. Ecuación polar 74. ¿Cuál de las integrales da la longitud de arco de r 5 3(1 – cos 2u )? Decir por qué las otras integrales son incorrectas. E E E E 2p a) 3 py4 b) 12 0#u#2p 56. r 5 a 0#u#2p 57. r 5 4 sen u 0#u#2p p p ≤ u ≤ 2 2 58. r 5 2a cos u 2 sin u 59. r 5 1 1 sen 0 ≤ u ≤ 2p 60. r 5 8s1 1 cos ud 0 ≤ u ≤ 2p !s1 2 cos 2ud2 1 4 sen sin 2 2u du 0 Intervalo 55. r 5 8 !s1 2 cos 2ud2 1 4 sen sin 2 2u du 0 p c) 3 !s1 2 cos 2ud2 1 4 sin sen2 2u du 0 py2 d) 6 !s1 2 cos 2ud2 1 4 sen sin 2 2u du 0 75. Dar las fórmulas de las integrales para el área de una superficie de revolución generada por la gráfica de r 5 f sud alrededor a) del eje x y b) del eje y. 1059997_1005.qxp 9/2/0816:58 3:51 Page PM Page 10-5.qxd 3/12/09 749 749 1059997_1005.qxp 9/2/08 3:51 PM Page 749 SECCIÓN 10.5 10.5 CPara A P S T discusión ONE equation, theel 76. Para cada ecuación polar,sketch dibujaritssugraph, gráfica,determine determinar C76. A PFor S T Oeach N E polar interval that traces the graph only and find the area of intervalo la gráfica sólo once, unagraph, vez y encontrar área 76. For each que polartraza equation, sketch its determineel the the region bounded by por the la graph usingutilizando a geometric formula de la región acotada gráfica una fórmula interval that traces the graph only once, and find the area of and integration. geométrica e integración. the region bounded by the graph using a geometric formula (a) (b) r b) 5 5r 5 sin5usen u 5 10 10 cos cos uu a) rrintegration. 5 and (a) r 5 10 cos u (b) r 5 5 sin u 77. Área de la superficie de un toro Hallar el área de la superfi77. Surface Areagenerado of a Torus Find the surface area of the torus cie del toro por revolución de la circunferencia r52 generated by revolving the circle given by r 5 2 about the line alrededor de la recta r 5 5 sec u . 77. Surface Area of a Torus Find the surface area of the torus r 5 5 sec u. bysuperficie revolving de theun circle by rel5área line 2 about 78. generated Área de la torogiven Hallar de lathe superfi78. rSurface Area of a Torus Find the surface area of the torus 5 del 5 sec u. generado cie toro por revolución de la circunferencia r5a generated circle given 0by<r a5 <a about the line en tornoArea aby la revolving recta 5 the b sec u, donde 78. Surface of a rTorus Find the surface areab.of the torus r 5 b sec u, where 0 < a < b. by revolving the circle given bylar circunferencia 5 a about the rline 79. generated Aproximación de un área Considerar 58 79. rApproximating Area 0 < Consider 5 bu.sec u, where a < b. the circle r 5 8 cos u. cos (a) Find the of circle. the circle r 5 8 cos u. 79. Approximating Area Consider a) Hallar el area área delthe círculo. (b) (a) b) (b) Área y longitud de arco en coordenadas polares Area and Arc Length in Polar Coordinates 749 10.5 Area and Arc Length in Polar Coordinates a) Use Emplear una herramienta graficación trazarula gráfir 5 upara , where (a) a graphing utility tode graph $ 0. ca dehappens con la gráfica r 5 u, donde u ≥ 0.of¿Qué u as a increases? r 5 aocurre What to the graph Whatde (a) Use utility to graph r 5 u, where u $ 0. aifmedida r 5 au graphing u # 0?que a aumenta? ¿Qué pasa si u ≤ 0? happens 5 au ras5a aincreases? What happens to the graph of respiral What b) Determine Determinarthe lospoints puntos r 5 au sua sa> >0, 0, u u$ ≥0d,0d, (b) ondethelaspiral 0? cruza happens if ula#curva en los que el eje polar. where the curve crosses the polar axis. r5 au sa > 00,≤u u$≤0d2,p. (b) Determine the points on theu sobre spiral el c) Hallar la longitud intervalo rde5 ru5 (c) where Find the overpolar the interval thelength curveof crosses the axis. 0 # u # 2p. d) Find Hallar áreaunder bajo lathecurva r r55u upara .. (d) theellength area for 00 0≤##uu u≤##22pp 2p . (c) Find the of r 5 ucurve over the interval 84.Logarithmic Espiral logarítmica La curve curva represented descrita porby la the ecuación r 5 84. Spiral The equation udenomina (d) Find the area under the curve r 5 for 0 # uespiral # 2p.logarítbu, donde ae a y b son constantes, se bu r 5 ae , where a and b are constants, is called a logarithmic 84. Logarithmic Spiral siguiente The curve represented by thedeequation mica. La figura gráfica r5 eu,y6, euy6 spiral. figure showsmuestra the la graph of r 5 bu The r 22 5 ae b are constants, is called a logarithmic Hallar el área de la zona sombreada. p ≤, where u ≤ 2pa. and 22p # u # 2p. Find the area of the shaded region. spiral. Theπ figure shows the graph of r 5 euy6, 22p # u #π 22p. Find the area of the shaded region. 2 π 2 0 1 Complete the table giving the áreas areas AA de of the the Find the area the dando circle. las Completar la of tabla los sectors sectoresofcircu5 0 u u circle between and the values of in the table. lares entre the valores de u dados en sectors la tabla.of the u 5table 0 y los A of the Complete giving the areas circle between u 5 0 and the values of u in the table. 0.2 0.4 0.6 0.8 1.0 1.2 1.4 u uA 0.2 0.4 0.6 0.8 1.0 1.2 1.4 A c) Emplear la tabla del inciso b) para aproximar los valores (c) Use the table in part (b) to approximate the values of u forde 1 11 1 para los circular contiene área uwhich , y 3434 del the cuales sector el of sector the circle composes of the 4 , 24 , 2and (c) Use the table in part (b) to approximate the values of u for total la of circunferencia. total de area the circle. 1 1 3 which the sector of the circle composes 4, 2, and 4 of the d) total Usar una herramienta de graficación para aproximar, con una (d) Use area a graphing utility to approximate, to two decimal of the circle. precisión dos cifras ángulos los u para u fordecimales, places, thede angles which thelossector of the circle (d) Use a graphing utility to approximate, 1 1 3 to two decimal 1 1 3 cuales el sector circular contiene y del área total de la , , , , composes and of the total area of the circle. 4 2 4 u for which 4the2 sector places, the4 angles of the circle circunferencia. 1 1 3 (e) composes Do the results of part (d) depend on the radius of the circle? 4 , 2 , and 4 of the total area of the circle. e) ¿Dependen Explain. los resultados del inciso d) del radio del círcu-lo? (e) Do the results of part (d) depend on the radius of the circle? Explicar laArea respuesta. 80. Approximate Consider the circle r 5 3 sin u. Explain. 80. (a) Área aproximada Dado el círculo r 5 3 sen sin u. Find the area circle. 80. Approximate Areaof the Consider the circle r 5 3 sin u. a) Hallar el área de la circunferencia correspondiente. (b) Find Complete theof table (a) the area the giving circle. the areas A of the sectors of the b) Completar la tabla las values áreas Aofdeu in losthe sectores u 5 dando 0 and the circle between table. circu(b) Complete the table giving the areas A of the sectors of the lares comprendidos entre u 5 0 y los valores de u dados en circle between u 5 0 and the values of u in the table. la utabla.0.2 0.4 0.6 0.8 1.0 1.2 1.4 uA 0.2 0.4 0.6 0.8 1.0 1.2 1.4 A (c) Use the table in part (b) to approximate the values of u for 1 1 1 which the sector of the circle composes 8, 4, and 2 of the (c) Use the la table in del partinciso (b) tob)approximate the values of u for c) Utilizar tabla para aproximar los valores de u total area of the circle. 1 11 1 para losthe cuales el of sector representa , y 12 12del which sector the circular circle composes ofárea the 8 , 84,, 4and (d) total Use de a graphing utility to approximate, to two decimal la of circunferencia. area the circle. places, the angles u de forgraficación which thepara sector of the con circle d ) Usar una herramienta aproximar, una (d) Use a graphing utility to approximate, to two decimal 1 1 1 composesde the total area of the circle. 8 , dos 4 , and 2 ofdecimales, precisión cifras los ángulos para los que u places, the angles u for which the sector of the circle 1 1 1 1 1 does 1 the following 81. What conic equation el sectorsection circular representa delofárea total represent? del círculo. 8 , 4 , yarea 2polar composes the circle. 8 , 4 , and 2 of the total 81. ¿Qué sección cónica representa la siguiente ecuación polar? 81. What r 5 a conic sin u section 1 b cosdoes u the following polar equation represent? r5 5aasin sinuu1 1bbcos cos u sen 82. rArea Find the areau of the circle given by r 5 sin u 1 cos u. your result theporpolar equation 82. Check Área Hallar el áreabydelconverting círculo dado r 5 sen sin u 1 costou. 82. Area Find the area of the circle given by r 5 sin u 1 cos u. rectangular then using the formula for area ofpolar a circle. Comprobarform, el resultado transformando la the ecuación a la Check your result by converting the polar equation to forma rectangular y usando después la fórmula para el área del 83. rectangular Spiral of Archimedes The the curve represented form, then using formula for the by areathe ofequation a circle. rcírculo. 5 au, where a is a constant, is called the spiral of 83. Spiral of Archimedes The curve represented by the equation 83. Archimedes. Espiral de Arquímedes La curva representada por la ecuación r 5 au, where a is a constant, is called the spiral of r 5 au, donde a es una constante, se llama espiral de Arquímedes. Archimedes. 749 749 2 3 0 1 2 3 1 2 3 0 85. La mayor de las circunferencias mostradas en la figura si85. The largerescircle in thedefigure the graph of r 5 1. Findpara the la guiente la gráfica la ecuación polar r 5 1.isHallar polar equation ofmenor the smaller circleque suchlasthat the sombreadas shaded regions circunferencia de manera áreas sean 85. The larger circle in the figure is the graph of r 5 1. Find the are equal. iguales. polar equation of the smaller circle such that the shaded regions are equal. π π 22 π 2 00 0 86. Folium Hoja (ooffolio) de Descartes curva llamadaofhoja (o folio) 86. Descartes A curve Una called the folium Descartes de be Descartes puede medio de las ecuaciones can represented by representarse the parametricpor equations 86. Folium of Descartes A curve called the folium of Descartes paramétricas can be 3t represented by the parametric 3t 2 equations x5 and y 5 3t 2 3. 3t 3 t 12 t . y x 51 1 y 5 1 3t 3t 3 3 y 5 1 1 t 3. x 5 1 13t and 1 1 t the parametric equations 1 1 t to polar form. (a) Convert a) Convertir las ecuaciones paramétricas a la forma polar. (b) Convert Sketch the graph of theequations polar equation from part (a). (a) parametric polar b) Dibujar the la gráfica de la ecuación to polar delform. inciso a). (c) Use a graphing utility to approximate the area enclosed by (b) theuna graph of the polar from part (a). c) Sketch Emplear herramienta de equation graficación para aproximar el the loop of the curve. áreaacomprendida en eltolazo de la curva. (c) Use graphing utility approximate the area enclosed by loop of curve. 87 and 88, determine whether the True or the False? Inthe Exercises ¿Verdadero o falso? En los ejercicios 87 y 88, determinar si la statement is true or false. If it is false, explain why or give an True or False? In Exercises 87 and determine whether the o afirmación es verdadera o falsa. Si 88, es falsa, explicar por qué example that shows it is false. statement is true que or false. If it isque false, explain why or give an dar un ejemplo demuestre es falsa. example false. 87. If f suthat for allituisand d > 0shows gsud < 0 for all u, then the graphs of 87. Si f sud > 0 para todo u y gsud < 0 para todo u, entonces las r 5 f sud and r 5 gsud do not intersect. f sud > 0defor sudgs<ud 0nofor u, then the graphs of 87. Ifgráficas y r g5 se all cortan. r 5allf suudand gsurd 5 0, not py2, 88. rIf5f sfusdu5 forgsuud5do and 3py2, then the graphs of and intersect. d 88. Si f sud 5 gsud para u 5 0, py2,y 3py2, entonces las gráficas de r 5 f sud and r 5 gsud have at least four points of intersection. sudf s5 0, py2, 3py2, cuatro 88. Ifr f5 andmenos then the graphs of tienen cuando puntos de interud gysur d5for gsud 5 r 5 f s u d s u d and r 5 g have at least four points of intersection. sección. 89. Use the formula for the arc length of a curve in parametric form 89. toUsar la fórmula parafor la longitud de arco una curva derive the formula the arc length of de a polar curve.en forma 89. Use the formula forobtener the arc length of a curve parametric formde paramétrica para la fórmula de la in longitud de arco touna derive the formula for the arc length of a polar curve. curva polar. 10-6.qxd 3/12/09 750 16:59 Page 750 CAPÍTULO 10 Cónicas, ecuaciones paramétricas y coordenadas polares 10.6 Ecuaciones polares de las cónicas y leyes de Kepler n n Analizar y dar las ecuaciones polares de las cónicas. Entender y emplear las leyes del movimiento planetario de Kepler. Ecuaciones polares de las cónicas EXPLORACIÓN Representación gráfica de cónicas En una herramienta de graficación elegir el modo polar e introducir ecuaciones polares de la forma r5 a 1 ± b cos u r5 a . 1 ± b sen sin u o En este capítulo se ha visto que las ecuaciones rectangulares de elipses e hipérbolas adquieren formas simples cuando sus centros se encuentran en el origen. Sin embargo, existen muchas aplicaciones importantes de las cónicas en las cuales resulta más conveniente usar uno de los focos como punto de referencia (el origen) del sistema de coordenadas. Por ejemplo, el Sol se encuentra en uno de los focos de la órbita de la Tierra; la fuente de luz en un reflector parabólico se encuentra en su foco. En esta sección se verá que las ecuaciones polares de las cónicas adoptan formas simples si uno de los focos se encuentra en el polo. El teorema siguiente usa el concepto de excentricidad, definido en la sección 10.1, para clasificar los tres tipos básicos de cónicas. En el apéndice A se da una demostración de este teorema. Si a Þ 0, la gráfica será una cónica. Describir los valores de a y b que generan parábolas. ¿Qué valores generan elipses? ¿Qué valores generan hipérbolas? TEOREMA 10.16 CLASIFICACIÓN DE LAS CÓNICAS DE ACUERDO CON LA EXCENTRICIDAD Sean F un punto fijo (foco) y D una recta fija (directriz) en el plano. Sean P otro punto en el plano y e (excentricidad) el cociente obtenido al dividir la distancia de P a F entre la distancia de P a D. El conjunto de todos los puntos P con una determinada excentricidad es una cónica. 1. La cónica es una elipse si 0 < e < 1. 2. La cónica es una parábola si e 5 1. 3. La cónica es una hipérbola si e > 1. Directriz Q π π 2 Directriz Directriz 2 P Q F = (0, 0) 0 P π 2 Q P F = (0, 0) 0 0 F = (0, 0) P′ Q′ Elipse: 0 < e < 1 PF < 1 PQ Parábola: e 5 1 PF 5 PQ Hipérbola: e > 1 PF P9 F 5 > 1 PQ P9 Q9 Figura 10.58 En la figura 10.58, obsérvese que en todos los tipos de cónicas el polo coincide con el punto fijo (foco) que se da en la definición. La ventaja de esta ubicación se aprecia en la demostración del teorema siguiente. 10-6.qxd 3/12/09 16:59 Page 751 SECCIÓN 10.6 Ecuaciones polares de las cónicas y leyes de Kepler 751 TEOREMA 10.17 ECUACIONES POLARES DE LAS CÓNICAS La gráfica de una ecuación polar de la forma r5 ed 1 ± e cos u o r5 ed 1 ± e sen sin u || es una cónica, donde e > 0 es la excentricidad y d es la distancia entre el foco, en el polo, y la directriz correspondiente. DEMOSTRACIÓN La siguiente es una demostración de r 5 edys1 1 e cos ud con d > 0. En la figura 10.59, considérese una directriz vertical que se encuentra d unidades a la derecha del foco F 5 (0, 0). Si P 5 (r, u) es un punto en la gráfica de r 5 edy(1 1 e cos u), se puede demostrar que la distancia entre P y la directriz es d P = (r, θ ) | Q θ | r F = (0, 0) | | | PQ 5 d 2 x 5 d 2 r cos u 5 0 | || r s1 1 e cos u d r 2 r cos u 5 . e e || Como la distancia entre P y el polo es simplemente PF 5 r , el radio PF entre PQ es PFyPQ 5 r y rye 5 e 5 e y, de acuerdo con el teorema 10.16, la gráfica de la ecuación debe ser una cónica. Las demostraciones de los otros casos son similares. ||| | || Directriz Figura 10.59 Los cuatro tipos de ecuaciones que se indican en el teorema 10.17 se pueden clasificar como sigue, siendo d > 0. ed 1 1 e sin u ed b) Directriz horizontal abajo del polo: r5 1 2 e sin u ed c) Directriz vertical a la derecha del polo: r 5 1 1 e cos u ed d) Directriz vertical a la izquierda del polo: r 5 1 2 e cos u a) Directriz horizontal arriba del polo: r5 La figura 10.60 ilustra estas cuatro posibilidades en el caso de una parábola. y Directriz y y y=d Directriz x=d x x Directriz r= ed 1 + e sen θ a) r= Directriz x = −d x x y=−d ed 1 − e sen θ b) Los cuatro tipos de ecuaciones polares para una parábola Figura 10.60 y r= c) ed 1 + e cos θ r= d) ed 1 − e cos θ 10-6.qxd 3/12/09 752 16:59 Page 752 CAPÍTULO 10 Cónicas, ecuaciones paramétricas y coordenadas polares EJEMPLO 1 π 2 Dibujar la gráfica de la cónica descrita por r 5 15 3 − 2 cos θ x=− 15 2 r= Determinar una cónica a partir de su ecuación 15 . 3 2 2 cos u Solución Para determinar el tipo de cónica, reescribir la ecuación como sigue (3, π ) (15, 0) 0 10 Directriz 5 15 3 2 2 cos u 5 5 . 1 2 s2y3d cos u r5 Escribir la ecuación original. Dividir el numerador y el denominador entre 3. Por tanto, la gráfica es una elipse con e 5 23. Se traza la mitad superior de la elipse localizando gráficamente los puntos desde u 5 0 hasta u 5 p, como se muestra en la figura 10.61. Luego, empleando la simetría respecto al eje polar se traza la mitad inferior de la elipse. La gráfica de la cónica es una elipse con e 5 23. Figura 10.61 En la elipse en la figura 10.61, el eje mayor es horizontal y los vértices se encuentran en (15, 0) y s3, pd. Por tanto, la longitud del eje mayor es 2a 5 18. Para encontrar la longitud del eje menor, se usan las ecuaciones e 5 cya y b 2 5 a 2 2 c 2 para concluir que b 2 5 a 2 2 c 2 5 a 2 2 sead 2 5 a 2s1 2 e 2d. Elipse. Como e 5 23, se tiene b 2 5 9 2 f1 2 s23 d g 5 45 2 lo cual implica que b 5 !45 5 3!5. Por tanto, la longitud del eje menor es 2b 5 6!5. Un análisis similar para la hipérbola da b 2 5 c 2 2 a 2 5 sead 2 2 a 2 5 a 2 se 2 2 1d. EJEMPLO 2 ( π −16, 32 ) π 2 Hipérbola. Trazar una cónica a partir de su ecuación polar Trazar la gráfica de la ecuación polar r 5 32 . sen u 3 1 5 sin Solución Se divide el numerador y el denominador entre 3 y se obtiene Directriz 32 y= 5 r5 a=6 b=8 0 ( π 4, 2 4 ) r= 8 32 3 + 5 sen θ La gráfica de la cónica es una hipérbola con e 5 53. Figura 10.62 32y3 . 1 1 s5y3d sen sin u Como e 5 53 > 1, la gráfica es una hipérbola. Como d 5 32 5 , la directriz es la recta El eje transversal de la hipérbola se encuentra en la recta y 5 32 . u 5 py2, y los vértices 5 se encuentran en 1 p2 2 sr, ud 5 4, 1 sr, ud 5 216, y 3p . 2 2 Dado que la longitud del eje transversal es 12, puede verse que a 5 6. Para encontrar b, se escribe 31532 b 2 5 a 2se 2 2 1d 5 6 2 2 4 2 1 5 64. Por tanto, b 5 8. Por último, se usan a y b para determinar las asíntotas de la hipérbola y obtener la gráfica que se muestra en la figura 10.62. 10-6.qxd 3/12/09 16:59 Page 753 SECCIÓN 10.6 Ecuaciones polares de las cónicas y leyes de Kepler 753 Leyes de Kepler Las leyes de Kepler, las cuales deben su nombre al astrónomo alemán Johannes Kepler, se emplean para describir las órbitas de los planetas alrededor del Sol. Mary Evans Picture Library 1. Todo planeta se mueve en una órbita elíptica alrededor del Sol. 2. Un rayo que va del Sol al planeta barre áreas iguales de la elipse en tiempos iguales. 3. El cuadrado del periodo es proporcional al cubo de la distancia media entre el planeta y el Sol.* Aun cuando Kepler dedujo estas leyes de manera empírica, más tarde fueron confirmadas por Newton. De hecho, Newton demostró que todas las leyes pueden deducirse de un conjunto de leyes universales del movimiento y la gravitación que gobiernan los movimientos de todos los cuerpos celestes, incluyendo cometas y satélites. Esto se muestra en el ejemplo siguiente con el cometa que debe su nombre al matemático inglés Edmund Halley (1656-1742). JOHANNES KEPLER (1571-1630) Kepler formuló sus tres leyes a partir de la extensa recopilación de datos del astrónomo danés Tycho Brahe, así como de la observación directa de la órbita de Marte. EJEMPLO 3 π 2 Sol π 0 Tierra Cometa Halley El cometa Halley tiene una órbita elíptica, con el Sol en uno de sus focos y una excentricidad e < 0.967. La longitud del eje mayor de la órbita es aproximadamente 35.88 unidades astronómicas (UA). (Una unidad astronómica se define como la distancia media entre la Tierra y el Sol, 93 millones de millas.) Hallar una ecuación polar de la órbita. ¿Qué tan cerca llega a pasar el cometa Halley del Sol? Solución Utilizando un eje vertical, se puede elegir una ecuación de la forma Cometa Halley r5 ed . s1 1 e sen sin u d Como los vértices de la elipse se encuentran en u 5 py2 y u 5 3py2, la longitud del eje mayor es la suma de los valores r en los vértices, como se observa en la figura 10.63. Es decir, 0.967d 0.967d 1 1 1 0.967 1 2 0.967 35.88 < 27.79d. 2a 5 2a < 35.88 Por tanto, d < 1.204 y ed < s0.967ds1.204d < 1.164. Usando este valor en la ecuación se obtiene r5 3π 2 Figura 10.63 1.164 1 1 0.967 sen sin u donde r se mide en unidades astronómicas. Para hallar el punto más cercano al Sol (el foco), se escribe c 5 ea < s0.967ds17.94d < 17.35. Puesto que c es la distancia entre el foco y el centro, el punto más cercano es a 2 c < 17.94 2 17.35 < 0.59 AU UA < 55,000,000 millas. * Si se usa como referencia la Tierra, cuyo periodo es 1 año y cuya distancia media es 1 unidad astronómica, la constante de proporcionalidad es 1. Por ejemplo, como la distancia media de Marte al Sol es D 5 1.524 UA, su periodo P está dado por D3 5 P 2. Por tanto, el periodo de Marte es P 5 1.88. 10-6.qxd 25/2/10 754 13:13 Página 754 CAPÍTULO 10 Cónicas, ecuaciones paramétricas y coordenadas polares La segunda ley de Kepler establece que cuando un planeta se mueve alrededor del Sol, un rayo que va del Sol hacia el planeta barre áreas iguales en tiempos iguales. Esta ley también puede aplicarse a cometas y asteroides con órbitas elípticas. Por ejemplo, la figura 10.64 muestra la órbita del asteroide Apolo alrededor del Sol. Aplicando la segunda ley de Kepler a este asteroide, se sabe que cuanto más cerca está del Sol mayor es su velocidad, ya que un rayo corto debe moverse más rápido para barrer la misma área que barre un rayo largo. Sol Sol Sol Un rayo que va del Sol al asteroide barre áreas iguales en tiempos iguales Figura 10.64 El asteroide Apolo EJEMPLO 4 El periodo del asteroide Apolo es de 661 días terrestres, y su órbita queda descrita aproximadamente por la elipse π 2 r θ=π 2 9 1 1 共5兾9兲 cos 9 5 cos donde r se mide en unidades astronómicas. ¿Cuánto tiempo necesita Apolo para moverse de la posición dada por 兾2 a 兾2, como se ilustra en la figura 10.65? Sol 0 1 Tierra Apolo Figura 10.65 θ =−π 2 Solución Para empezar se encuentra el área barrida cuando aumenta de 兾2 a 兾2. A 1 2 1 2 冕 冕 r 2 d 兾2 兾2 Fórmula para el área de una gráfica polar. 冢9 59cos 冣 d 2 Usando la sustitución u tan共兾2兲, analizada en la sección 8.6, se obtiene 冤 冪56 tan共兾2兲 81 5 sen sin 18 A arctan 112 9 5 cos 冪56 14 冥 兾2 ⬇ 0.90429. 兾2 Como el eje mayor de la elipse tiene longitud 2a 81兾28 y la excentricidad es e 5兾9, se encuentra que b a冪1 e2 9兾冪56. Por tanto, el área de la elipse es Área de la elipse ab 9 ⬇ 5.46507. 冢81 56 冣冢 冪56 冣 Como el tiempo requerido para recorrer la órbita es 661 días, se puede aplicar la segunda ley de Kepler para concluir que el tiempo t requerido para moverse de la posición 兾2 a la posición 兾2 está dado por t área del segmento elíptico 0.90429 ⬇ 661 área de la elipse 5.46507 lo cual implica que t ⬇ 109 días. 10-6.qxd 3/12/09 16:59 Page 755 1059997_1006.qxp 9/2/08 3:52 PM Page 755 1059997_1006.qxp 9/2/08 3:52 PM Page 755 SECCIÓN 10.6 755 Ecuaciones polares de las cónicas y leyes de Kepler Kepler’s Laws 755 10.6 Polar Equations of Conics and Kepler’s Laws 10.6 Ejercicios See www.CalcChat.com worked-out to odd-numberedπexercises. 10.6 Exercises π Razonamiento gráfico En los ejercicios 1 a 4, usar for una herra-solutions e) f) 2 2 mienta de graficación para representar la ecuación polar cuan10.6 Exercises See www.CalcChat.com for worked-out solutions to odd-numbered exercises. 755 do a) e 5 1, b) e 5 0.5, y c) e 5 1.5. Identificar la cónica. 2e 2e Reasoning In Exercises r5 1.Graphical 2. r 5 1– 4, use a graphing 1 1 e cos u 1 2 utility to graph the polar equation when (a) ee cos1,u (b) e 0.5, 2e and (c) e 2e1.5. Identify the conic. 3. r 5 4. r 5 sen u 1 2 e sin 1 1 e sen sin u 2e 2e 1. 2. r r Considerar la ecuación polar1 e cos 5. Redacción 1 e cos 4 . 2e 2e r5 3. r 4. r 1 1 e sin sen u 1 e sin 1 e sin a) Usar una herramienta de graficación 5. Writing Consider the polar equation para representar la ecuación con e 5 0.1, e 5 0.25, e 5 0.5, e 5 0.75, y e 5 0.9. 4 r Identificar la .cónica y analizar la variación en su forma cuan1 e do e →sin 12 y e → 0 1 . b) Usar herramienta graficación para representar la (a) Use auna graphing utility de to graph the equation for e 0.1, ecuación Identificar cónica. and e la 0.9. Identify the conic e 0.25,cuando e 0.5,e e5 1.0.75, c) Usar una herramienta dein graficación para representar and discuss the change its shape as e→ 1 and e la→ecua0 . y e 5the y e 5 1.1, e 5 to 1.5,graph 2. Identificar (b) ción Use cuando a graphing utility equation la forcónica e 1. analizar en su forma a medida que e → 1 1 Identify la thevariación conic. y e → `. (c) Use a graphing utility to graph the equation for e 1.1, 6. Considerar la ecuación and e polar e 1.5, 2. Identify the conic and discuss the change4in its shape as e → 1 and e → . . r5 1 2 0.4 cos u 6. Consider the polar equation a) Identificar sin elaborar la gráfica de la ecuación. 4 la cónica . r 1 elaborar 0.4 cosla gráfica de las ecuaciones polares siguientes, b) Sin describir la diferencia de cada una con la ecuación polar de (a) arriba. Identify the conic without graphing the equation. (b) Without graphing the following4 polar equations, describe 4 rhow 5 each differs from , r the 5 polar equation above. 1 1 0.4 cos u 1 2 0.4 sen sin u 4 4 c) Verificar en forma gráfica r , r los resultados del inciso b). 1 0.4 cos 1 0.4 sin En los ejercicios 7 a 12 hacer corresponder la ecuación polar con (c) Verify the results of part (b) graphically. su gráfica. [Las gráficas están etiquetadas a), b), c), d), e) y f).] In Exercises 7–12, match the polar equation with the correct π (e), and (f).] a)graph. [Theπgraphs are labeled (a), b) (b), (c), (d), 2 2 π 2 (a) π π 2 (b) 0 3 π 0 3 4 6 0 π 4 6 3π 2 3π π 2 2 π 2 c) (c) π 2 4 6 π 2 4 6 3π 2 3π 2 π 2 d) (d) 3 4 π 1 3π 2 3π 2 3 4 3π 2 1 3 3 6 1 2 cos u 3π 32 9. r 5 1 2 62 sen sin u 7. r 1 6cos 11. r 5 2 2 sen sin 3 u 9. r 1 2 sin (f) π 0 0 π 2 3π 2 π 1 1 8. r 5 2 2 2 cos u 10. r 5 22 1 1 2sen sin u 2 2 0 0 3π 8. r 2 2 cos 12. r 5 2 1 23 cos u 10. r 1 sin 6 2y la distancia del En excentricidad 11. los r ejercicios 13 a 26, hallar la12. r sin 3 cos polo a la2 directriz de la cónica. Después 2trazar e identificar la gráfica. Usar una herramienta de graficación para confirmar los In Exercises 13–26, find the eccentricity and the distance from resultados. the pole to the directrix of the conic. Then sketch and identify the graph. Use 1 a graphing utility to confirm your 1 results. 13. r 14. r 1 1cos 1 1sen 13. r 14. r 4 1 4sen 1 cos 15. r 16. r 1 sen 1 4cos 4 15. r 16. r 6 1 cos 1 sen 17. r 2 6cos 17. r 2 10 cos 18. r 5 10 4 sen 18. r 19. r 2 5 sen4 sen 4 20. 19. r 23 2 cos sen 46 2 cos5 6 1 52 cos 20. r 3 21. r 21. r 22. r 22. r 23. r 24. r 25. r 26. r π 2 1 0 7. r 5 25. r 26. r 3π 2 π 0 0 π 2 1 π 23. r 24. r π 3π 2 (e) π 3 62 cos 7 6sen 3 2 73 sen 63 sen 2 1 68 sen 48 cos 1 4300 cos 12 3006 sen 12 180 6 sen 15 3.75 180 cos 1 15 3.75 cos En los ejercicios 27 ause 30,ausar una herramienta de graficación In Exercises 27– 30, graphing utility to graph the polar para representar la ecuación polar. Identificar la gráfica. equation. Identify the graph and find its eccentricity. 0 0 27. r 29. r 4 1 3 2 sen 10 cos 28. r 30. r 2 15 8 sen 6 6 7 cos 10-6.qxd 3/12/09 16:59 Page 756 1059997_1006.qxp 9/8/08 3:40 PM Page 756 1059997_1006.qxp 9/8/08 3:40 PM Page 756 756 CAPÍTULO 10 Cónicas, ecuaciones paramétricas y coordenadas polares En los ejercicios 31 a 34, usar una graficadora para representar Desarrollo de conceptos la cónica. Describir en qué difiere la gráfica de la del ejercicio 756 Chapter 10 Conics, Parametric Equations, and Polar Coordinates indicado. 756 Chapter 10 Conics, Parametric Equations, and Polar Coordinates 51. Clasificar las cónicas de acuerdo con su excentricidad. 52. Identificar cada cónica. 214 31. r 5 (Ver ejercicio 15.) In Exercises sen 12 sinsu 2 31– py434, d use a graphing utility to graph the conic. R I T I N G5 A B O U T Cb)O Nr C5E P T S5 In Exercises 31–how 34, the use graph a graphing utility to graph the conic. rN5 a)T W W R I I G 1A2B O2 U T CONCEPTS Describe differs from the graph in the indicated cos 2 sin sen u 64 graph differs from the graph in the indicated 51. Classify theuconics by their 10 eccentricities. Describe how the 32. (Ver ejercicio 16.) r 5exercise. 51. Classify the conics by their eccentricities. 5 5 exercise.1 1 cossu 2 py3d r 5 Identify each conic. d) r 5 c) 52. 52. Identify3each 2 3conic. cos u 1 2 3 sen sinsu 2 py4d 4 6 5 5 (See Exercise 15.) 4 33. r 531. r (Ver ejercicio 17.) (a)qué (b) rla 5directriz y el cenr pasa 4 (See Exercise 15.) 5 con la distancia entre 31. r 2 1 cos1su 1sin py6d 53. Describir 1 2 cos 10 sin (a) r (b) r 1 sin 4 1 elipse 2 cossi los focos permanecen 10 fijos sin y e se aprotro de una 4 26 5 5 (See Exercise 16.) 4 34. r 532. r (Ver ejercicio 22.) xima a (c) 0. r 5 (d) r 1 su 1 cos2py3d 3(See Exercise 16.) 5 32. r 3 1 7 sen sin 3 3 cos (d) r 1 3 sin 4 (c) r 1 cos 3 3 3 cos 1 3 sin 4 6 53. Describe what happens to the distance between the directrix 33. (See Exercise 17.) r 6 la elipse que se obtiene al girar py6 radianes 35. Dar la ecuación 2 decos 6(See Exercise 17.) 53. Describe what theellipse distance the directrix 33. r and the happens center oftoan if between the foci remain fixed and e 2 cos 6 en sentido de las manecillas del reloj la elipse and theapproaches center of an ellipse if the foci remain fixed and e 6 0. 34. r 5 (See Exercise 22.) approaches 0. 8 3 67 sin Para discusión 3 Exercise 22.) 34. rr5 . 2 3 2 (See 3 7 sin 85 1 53 cos u en qué difiere la gráfica de cada cónica de la grá35. Write the equation for the ellipse rotated 6 radian clockwise 54. Explicar CAPSTONE 35. Dar Write the equation the ellipse 36. la ecuación lafor parábola que rotated se obtiene 6alradian girar pclockwise y4 radia4 CAPSTONE from thede ellipse r 5 how the. graph of each conic differs from the graph fica54. de Explain from ellipse nes en the sentido contrario a las manecillas del reloj la parábola 1 1 sin sen 54. Explain how the graph 4 u of each conic differs from the graph 8 of r 44 . r92 8 . 4 of 8 . 5. cos rr5 a) rr 5 1 sin1 . sin b) r 5 5 cos 181 sen sin u 1 2 cos u 1 2 sen sin u 4 4 36. Write the equation for the parabola rotated 4 radian (a) r 44 (b) r 4 4 36. Write counterclockwise the equation forfrom the the parabola rotated radian 4 1 cos 1 sin (a) r (b) r c) r 5 d) r 5 parabola cosu 1 sen 111 cos 12 sinsin su 2 py4d En los ejercicios 37 a 48, una ecuación polar de la cónica counterclockwise fromhallar the parabola 4 4 (c) r 4 (d) r 9 conveniencia, la ecuación de la directriz con foco en el polo. (Por 4 1 cos 1 sin 4 r9 . (c) r (d) r está dada en forma 1 . rectangular.) sin 1 cos 1 sin 4 r 1 sin x2 y2 55. Demostrar que la ecuación polar de 2 1 2 5 1 es Cónica Excentricidad Directriz a b In Exercises 37– 48, find a polar equation for the conic with its x2 y2 In Exercises 37– 48,pole. find (For a polar equation for conic with its direc2 fory2 focus at the convenience, thethe equation for the 1 is 55. Show that the polar equation x 2 2 37. Parábola e convenience, 51 x 5 21 for the direcb a b focus at the pole. (For the equation 1 is2 55. rShow for 2 5 that the polar. equation 2 trix is given in rectangular form.) Elipse. a2 b 2 2 1 2 e cos u 2 trixParábola is given in rectangular 38. e 5 1form.) y51 b . Directrix Conic Eccentricity Ellipse r 2 b2 1 2 e2.cos2 Ellipse x2 y2 Conic r2 39. Elipse eEccentricity 5 12 yDirectrix 51 2 56. Demostrar 1 eque cosla ecuación polar de 2 2 2 5 1 es 37. Parabola e 1 x 3 a b 37. Elipse Parabola e 31 40. yx5 223y 4 x2 y2 38. Parabola e 5 4 e 1 2 fory2 56. Show that the polar equation 1 is x 2 2 38. Parabola e 1 y 4 a 1bis2 56. rShow that2b the polar. equation for 2 2 41. Hipérbola e52 e 1 x51 y 1 2 5 Hipérbola. 39. Ellipse a b 2 1 2 e 2 cos 2 u 2 e 12 y 1 39. Ellipse b 42. Hipérbola e 5 323 e 34 x 5 21y 2 2 40. Ellipse . 2 r Hyperbola b e 4 y 2 40. Ellipse 1 e 2.cos 2 Hyperbola r2 2 cos 2 e 2 x 1 41. Hyperbola 1 e En los ejercicios 57 a 60, usar los resultados de los ejercicios 55 e 2 x 1 41. Hyperbola 3 e vértices x 1 42. Hyperbola Vértice Cónica y 56 para dar la forma polaruse de the la ecuación deExercises la cónica.55 and 56 to 2 3 o In Exercises 57–60, results of e 2 x 1 42. Hyperbola In Exercises 57–60, use the results of Exercises 55 and 56 to writefoco the polar of the en equation of the p 57. Elipse: en (4,ofform 0); vértices (5, 0), sconic. 5, p d conic. 43. ParábolaConic 1, 2 Vertex or Vertices write the polar form the equation of the Conic Vertex2 or Vertices 57. Ellipse: 0); vertices (5,s4, 0),pd5, 58. Hipérbola: foco focus en (5,at0);(4,vértices en (4,at0), 1, 43. Parabola 57. Ellipse: focus at (4, 0); vertices at (5, 0), 5, 44. Parábola s 5, p d 2 2 2 1, 43. Parabola x 58. yHyperbola: focus at (5, 0); vertices at (4, 0), 4, 2 59. 2 5 focus 1 58. Hyperbola: at (5, 0); vertices at (4, 0), 4, 44. Parabola s2, 0d, s8,5,pd 9 16 45. Elipse x2 2 y2 2 5, 44. Parabola 1 x 2 59. y 9 116 2, 0 , 8, 45. Ellipse 59. x 2 p0 , 8, 3p 51 60. 9 1 y16 2, 45. Ellipse 46. Elipse 2, , 4, 4 x2 3 2 y2 1 2, 23 , 4, 46. Ellipse x 2 60. 2 2 y4 1 60. 2, , 4,2 46. Ellipse 4 ejercicios 61 a 64, usar las funciones de integración de una 32p 32p En los 47. Hipérbola 1, , 9,3 3 In Exercises 61–64, usepara the integration of a graphing 23 1, 23 , 9, 47. Hyperbola herramienta de graficación estimar concapabilities una precisión de 2 2 In Exercises 61–64, use the integration capabilities of a the graphing 1, , 9, 47. Hyperbola utility to approximate decimal places area of the dos cifras decimales el área detola two región limitada por la gráfica 2 2 48. Hipérbola utility region to approximate to two decimal places the area of the 2, 00d, 10, 0 48. Hyperbola s2, 0d, s10, bounded de la ecuación polar. by the graph of the polar equation. 2, 0 , 10, 0 48. Hyperbola region bounded by the graph of the polar equation. 49. Encontrar la aecuación para lafor elipse con foco 0), excentrici9 3 0, 0 , eccentricity 49. Find polar equation the ellipse with(0, focus 61. r 3 62. r 9 1 0, 0 , eccentricity 49. dad Finddea polar equation for the ellipse with focus 4 cos 2 cos and a directrix directriz en r at 5 r4 sec4 usec . . 61. r 62. r 2, y 1 2 cos 4 cos 4 sec . 2 , and a directrix at r 3 2 50. Find a polar equation for the hyperbola with focus 0, 0 , eccen63. r 2 64. r 3 50. la ecuación para una hipérbolawith confocus foco (0, 0), excen50. Encontrar Find a polar the hyperbola 8 csc . 0, 0 , eccentricityequation 2, and afor directrix at r 3 2 sen 6 5 sen 63. r 64. r tricidad 2 yadirectriz cscu. . tricity 2,deand directrixenat rr 5 288csc 3 2 sen 6 5 sen 1 2 1 2 1 1 2 1 2 2 10-6.qxd 3/12/09 16:59 Page 757 SECCIÓN 10.6 Ecuaciones polares de las cónicas y leyes de Kepler 757 65. Explorer 18 El 27 de noviembre de 1963, Estados Unidos CAS 71. Movimiento planetario En el ejercicio 69 se encontró la ecualanzó el Explorer 18. Sus puntos bajo y alto sobre la superficie ción polar para la órbita elíptica de Neptuno. Usar la ecuación y de la Tierra fueron aproximadamente 119 millas y 123 000 un sistema algebraico por computadora. millas, respectivamente (ver la figura). El centro de la Tierra es a) Aproximar el área que barre un rayo que va del Sol al planeel foco de la órbita. Hallar la ecuación polar de la órbita y hallar ta cuando u aumenta de 0 a p/9. Emplear este resultado para la distancia entre la superficie de la Tierra y el satélite cuando determinar cuántos años necesita Neptuno para recorrer este u 5 608. (Tomar como radio de la Tierra 4 000 millas.) arco, si el periodo de una revolución alrededor del Sol es de 165 años. 90° Explorer 18 r 60° 0 Tierra a b) Por ensayo y error, aproximar el ángulo a tal que el área barrida por un rayo que va del Sol al planeta cuando u aumenta de p a a sea igual al área encontrada en el inciso a) (ver la figura). ¿Barre el rayo un ángulo mayor o menor que el del inciso a), para generar la misma área? ¿A qué se debe? π 2 No está dibujado a escala θ =π 9 66. Movimiento planetario Los planetas giran en órbitas elípticas con el Sol como uno de sus focos, como se muestra en la figura. 0 α −π π 2 Planeta r θ 0 Sol a No está dibujado a escala a) Mostrar que la ecuación polar de la órbita está dada por s1 2 e2d a r5 1 2 e cos u donde e es la excentricidad. b) Mostrar que la distancia mínima (perihelio) entre el Sol y el planeta es r 5 as1 2 ed y que la distancia máxima (afelio) es r 5 as1 1 ed. En los ejercicios 67 a 70, usar el ejercicio 66 para hallar la ecuación polar de la órbita elíptica del planeta, así como las distancias en el perihelio y en el afelio. 67. Tierra a 5 1.496 3 108 kilómetros e 5 0.0167 68. Saturno a 5 1.427 3 10 9 kilómetros e 5 0.0542 69. Neptuno a 5 4.498 3 109 kilómetros 70. Mercurio a 5 5.791 3 107 kilómetros e 5 0.0086 e 5 0.2056 c) Aproximar las distancias que recorrió el planeta en los incisos a) y b). Usar estas distancias para aproximar la cantidad promedio de kilómetros al año que recorrió el planeta en los dos casos. 72. Cometa Hale-Bopp El cometa Hale-Bopp tiene una órbita elíptica con el Sol en uno de sus focos y una excentricidad de e < 0.995. La longitud del eje mayor de la órbita es aproximadamente 500 unidades astronómicas. a) Hallar la longitud del eje menor. b) Hallar la ecuación polar de la órbita. c) Hallar distancias en el perihelio y en el afelio. En los ejercicios 73 y 74, sea r0 la distancia del foco al vértice más cercano, y r1 la distancia del foco al vértice más lejano. 73. Mostrar que la excentricidad de una elipse puede expresarse como e5 r r1 2 r0 11e . Después mostrar que 1 5 . r1 1 r0 r0 1 2 e 74. Mostrar que la excentricidad de una hipérbola puede expresarse como e5 r1 1 r0 r e11 . Después, mostrar que 1 5 . r1 2 r0 r0 e 2 1 En los ejercicios 75 y 76, mostrar que las gráficas de las ecuaciones dadas se cortan en ángulo recto. 75. r 5 ed 1 1 sen sin u y r5 76. r 5 c 1 1 cos u y r5 ed 1 2 sen sin u d 1 2 cos u 10-7.qxd 3/12/09 758 17:01 Page 758 CAPÍTULO 10 Cónicas, ecuaciones paramétricas y coordenadas polares Ejercicios de repaso 10 En los ejercicios 1 a 6, hacer corresponder la ecuación con su gráfica. [Las gráficas están etiquetadas a), b), c), d), e) y f).] y a) 17. Vértice: (67, 0); foco: (69, 0) 18. Foco: s0, ± 8d; asíntotas: y 5 ± 4x y b) En los ejercicios 17 y 18, hallar la ecuación de la hipérbola. 4 4 2 x x −2 2 −12 4 −8 En los ejercicios 19 y 20, usar una herramienta graficadora para aproximar al perímetro de la elipse. −4 −2 19. −4 x2 y2 1 51 9 4 20. x2 y2 1 51 4 25 −4 y c) 21. Una recta es tangente a la parábola y 5 x 2 2 2x 1 2 y perpendicular a la recta y 5 x 2 2. Hallar la ecuación de la recta. y d) 4 22. Una recta es tangente a la parábola 3x 2 1 y 5 x 2 6 y perpendicular a la recta 2x 1 y 5 5. Hallar la ecuación de la recta. 4 2 x −4 2 −2 x 4 −4 2 −2 −4 4 y5 −4 y e) b) Hallar el área de la superficie de la antena. 4 x −4 2 −2 2 4 x −2 −4 2 4 −2 1. 4 x 2 1 y 2 5 4 3. y2 5 24 x 5. x2 1 4y 2 54 2. 4 x 2 2 y 2 5 4 4. y 2 2 4 x 2 5 4 a) Hallar el volumen del tanque. 6. x2 5 4y 7. 16x 2 1 16y 2 2 16x 1 24y 2 3 5 0 9. 3x 2 2 2y 2 1 24x 1 12y 1 24 5 0 11. 3x 2 12. 12x 20x 2y 2 2 12y 19 12x 2 12x 0 12y 24y 29 0 45 b) Hallar la fuerza ejercida sobre el fondo del tanque cuando está lleno de agua. (La densidad del agua es 62.4 libras por pie cuadrado.) c) Hallar la profundidad del agua en el tanque si está lleno a Er de su capacidad (en volumen) y el camión se encuentra sobre un terreno nivelado. d) Aproximar el área en la superficie del tanque. 8. y 2 2 12y 2 8x 1 20 5 0 y2 24. Camión de bomberos Considerar un camión de bomberos con un tanque de agua que mide 16 pies de longitud, cuyas secciones transversales verticales son elipses que se describen por la ecuación x2 y2 1 5 1. 16 9 En los ejercicios 7 a 12, analizar la ecuación y trazar su gráfica. Emplear una herramienta de graficación para confirmar los resultados. 10. 5x 2 2100 ≤ x ≤ 100. a) Hallar las coordenadas del foco. 6 4 x2 , 200 El equipo de recepción y transmisión se coloca en el foco. y f) 23. Antena satelital La sección transversal de una gran antena parabólica se modela por medio de la gráfica de 0 En los ejercicios 25 a 32, trazar la curva representada por las ecuaciones paramétricas (indicar la orientación de la curva) y dar las ecuaciones rectangulares correspondientes mediante la eliminación del parámetro. 25. x 1 En los ejercicios 13 y 14, hallar una ecuación de la parábola. 26. x t 13. Vértice: s0, 2d; directriz: x 5 23 27. x et 8t, y 6, y 4t 3 4t t2 1, y e3t 28. x e , y 29. x 6 cos , y En los ejercicios 15 y 16, hallar la ecuación de la elipse. 30. x 2 15. Vértices: (25, 0) s7, 0d; focos: (23, 0) (5, 0) 31. x 5 2 1 sec u, y 5 3 1 tan u 14. Vértice: (2, 6); foco: (2, 4) 16. Centro: s0, 0d; puntos solución: (1, 2), (2, 0) t 4 6 sen 5 cos t, y 3 sin 3 u, y 5 5 cos3 u 32. x 5 5 sen 2 sen t 10-7.qxd 3/12/09 1059997_100R.qxp 1059997_100R.qxp 1059997_100R.qxp 1059997_100R.qxp 17:01 Page 759 9/2/08 9/2/08 3:52 3:52 PM PM Page Page 759 759 9/2/08 3:52 PM Page 7599/2/08 9/2/08 1059997_100R.qxp 3:52 PM Page 759 3:52 PM Page 759 Ejercicios de repaso 759 Review 759 Review Exercises Exercises 759 Review Exercises 759 En los ejercicios 33 a 36, hallar una representación paramétrica herramienta de graficación En los ejercicios 53 y 54, a) usar una Review Exercises 759 Review Exercises de la recta o cónica. para trazar la curva representada por las ecuaciones paramétricas, b) usar una herramienta de graficación para hallar dx/dqq , In 33–36, find representation In In Exercises Exercises 33–36, find6aad parametric parametric representation of of the the line line In Exercises Exercises 53 53 and and 54, 54, (a) (a) use use aa graphing graphing utility utility to to graph graph the the 33. Recta: pasa por s22, y s3, 2d In conic. Exercises 33–36, find a parametric representation ofathe line In Exercises and 54, (a) graphing utility to graph the q yrepresented dy/dq dy/dx53 para y In c)ausar unaequations, herramienta deuse grafiuby 5p 6,use or curve the parametric (b) aaa graphing utility to g / In Exercises 33–36, find parametric representation of the line Exercises 53 and 54, (a) use or conic. curve represented by the parametric equations, (b) use In Exercises 33–36, find a parametric representation of the line In Exercises 53 and 54, (a) use a graphing utility to graph the or conic. curve represented by the parametric equations, (b) use 34. Circunferencia: centro en (24, 25); radio 3 cación para trazar la recta tangente arepresented la dy/dx curvafor cuando u/6, 5 parametric p /a6. dx/d , dy/d , graphing utility to find and and or conic. curve by the equations, (b , dy/d , and dy/dx graphing utility to find for or conic. curve represented by dx/d the parametric equations, (b) /6, useand a 2, 66 and 3, 33. Line: through dx/d , dy/d , and dy/dx /6, graphing utility to find for and 2,longitud 3, 22eje mayor horizontal 8 y 33. Elipse: Line: passes passes through and del (c) use a graphing utility to graph the tangent line to the curve dx/d , dy/d , dy/dx graphing utility to find and for 35. centro en s 23, 4 d ; (c) use a graphing utility to graph the tangent line to the curve dx/d , dy/d , and graphing utility and 2, 633.and 3, 2 33. Line: passes through 53. 54.the x 5a cot u to find x tangent 5 dy/dx 2u 2 for sin sen uto the/6, 2, 6 and 3,when 2 use Line: (c) graphing utility to graph line curve 4, 34. Circle: center at 333, 2passes through 33. Line: through and /6. (c) use atangent graphing utility tocurve graph the tangent line to t del eje 4, 6 52, 5 ;;6radius 34. longitud Circle:passes center atmenor radius /6. when (c) use a graphing utility to graph the line to the 4, 5 ; 34. 34. Circle: center at radius 3 wheny 5 sen sin 2/6. u 2 cos u 4, 5 ; radius 3 when Circle: when y 5 2 /6. 3, 35. Ellipse: center at ;d;radius 34. Hipérbola: Circle: center at 3 major 36. vértice foco en s0,44±5;;4horizontal s0,center ± 5axis d atof /6. 3, 35. Ellipse: center at en4, horizontal major axis of length length 88 and and x cot xx 22 sin 53. 54. 35. minor Ellipse:axis center at 63, 4 ; horizontal major axis of length 8 and x cot sin 53. 54. of length 3, 4 8; horizontal 35. Ellipse: center major x axis cotof length 8 and sin 53. 54.x x cot2 minor axis of length 6 4 ; horizontal 35. Ellipse: center at 3, major axis at of length and sin 53. Longitud de arco En los ejercicios 55 y 56, hallar minor axis of length 6 y sin 2 y 2 cos cot 2 sin la longitud de54. x 2 53. yx sin 54. yx 22 cos minor axis of length 6 37. Motor rotatorio El motor rotatorio fue inventado por Felix 0, 4 ; 5 0, 36. Hyperbola: vertices at ± foci at ± minor axis of length 6 y sin 2 y 2 cos 36. Hyperbola: vertices at 0, ± 4 ; foci at 0, ± 5 arco de la curva en el intervalo que se indica. y sin 2 y 2 cos 36. Wankel Hyperbola: verticesdeatlos0,cincuenta. ± 4 ; foci at 0, ± 5 un rotor que es un en la década Contiene 0,yLength Hyperbola: ± 5 sin 2 In Exercises 55 and 56,yfind2 the cos Arc arc length 4 ; foci 36. Hyperbola: vertices at 0, ±36. at 0, ± 5vertices at 0, ± 4 ; foci at Arc Length In Exercises and56. 56,xfind arc length of of the the triángulo equiláteroThe modificado. El rotorwas se mueve en una cámara 37. Rotary Engine rotary engine developed by Felix sen ud 55 55. x 5 rthe scosgiven u1 uinterval. sin 5 6the cos uExercises Arc Length In Exercises 55 and 56, find the arc length 55 of the 37. Rotary Engine The rotary engine was developed by Felix curve on Arc Length In and 56, find the arc leng curve on the given interval. Arc Length In Exercises 55 and 56, find the arc length of the 37. que, Rotary Engine The rotary engine was developed by Felix en dos dimensiones, esfeatures un37. epitrocoide. Usar una herramienta in It aa rotor, which is aa modified Rotary Engine rotary engine curve wasy developed byuinterval. Felix onrthe given Wankel Engine in the the 1950s. 1950s. It features rotor, which isThe modified sen 5 s sin u 2 cos u d y 5 6 sin u sen 37. Wankel Rotary The rotary engine was developed by Felix curve on the given interval. curve onr the interval. Wankel in thepara 1950s. It lafeatures aque rotor, which is aecuaciones modified de graficación trazar cámara describen las cos sin equilateral The moves in two 55. 56. Wankel the 1950s. Itin isgiven a modified cos sin equilateral triangle. The rotor moves in aainchamber chamber that, infeatures two a rotor, 55. xx0which 56. xx0 ≤ 66u cos Wankel in triangle. the 1950s. It rotor features a rotor, which is that, a modified ≤ rru cos ≤ p ≤ p x cos 6 cos sin equilateral triangle. The rotor moves in a chamber that, in two 55. 56.x x r cos paramétricas. dimensions, is an epitrochoid. Use a graphing utility to graph sin equilateral triangle. The rotor moves 55. in ayxchamber that, incos two 55.56. 56. x 6 cos r sin y 6 sin dimensions, is an epitrochoid. Use a in graphing utility to ingraph cos x sin equilateral triangle. The rotor moves a chamber that, two y r sin y 6 cos sin cos dimensions, is an epitrochoid. Use a graphing utility to graph y r utility sin to graph y r sin 6 sin cos chamber modeled by equations dimensions, is utility an epitrochoid. Use a graphing the chamber modeled by the the parametric parametric equations y cos dimensions, is an epitrochoid. Use a graphing to graph xthe 5 cos 3 u 1 5 cos u 00y 657 Área00y de una r sinsuperficie siny 58, hallar el área y 6 sin cos En los ejercicios the chamber modeled by the parametric equations the chamber modeled by the parametric equations 0 0 modeled by the parametric equations xxthe chamber cos 3 5 cos 0 0 de la0 superficie generada por revolución de la curva en torno 0 3 5 cos yx cos cos 3 5 cos Surface In Exercises 57 x cos 3 5 cos a) al eje Area xArea y b) al y. Surface Ineje Exercises 57 and and 58, 58, find find the the area area of of the the xand cos 3 5 cos Surface generated Area In by Exercises 57 andcurve 58, find the(a) area of the surface revolving the about the xx-axis Surface Area In Exercises 57 sen yand 5 sin 3 u 1 5 sin u . sen surface generated by revolving the curve about (a) the -axis Surface Area In Exercises 57 and 58, find the area of the and 58, find the are and surface generated by0revolving the curve about by (a) revolving the x-axis and 57. x 5 t, y 5 3t, ≤ t ≤ 2 and (b) the -axis. y surface generated and (b) the y-axis. by revolving the curve about (a) the x-axisthe curve about (a) t surface generated yyand sin 55 sin sin 33 sin .. and (b) the y-axis. 38. Curva las ecuaciones paramétricas and (b) thepy-axis. y sinserpentina 3 5 sin Considerar . and (b) the yy-axis. y sin 3 5 sin . sen 57. x t, tt u, 22 0 ≤ u ≤ x 5 2 cos 58. y sin 3 5 sin . sen y x 5 2 cot u y 5 4 sin u cos u , 0 < u < p . 57. x t, y u, 3t, 3t,y 500 2 sin 38. 38. Serpentine Serpentine Curve Curve Consider Consider the the parametric parametric equations equations 57. x t, y 3t, 0 t 257. x t, 2 y 3t, 0 t 2 38. xSerpentine Curve Consider the parametric equations 57.parametric x t, y equations 3t, 0 t 2 22 cot yy 44 Consider sin cos ,, the < .Curve 00 < 38. Consider the58. una and herramienta la equations curva. and x Usar cot sinde graficación cos Serpentine < para < trazar . 38. a) Serpentine Curve parametric xx En 22 cos ,, yy 22 59 sin x 2 cot and y 4 sin cos x, 0 2< cot< and . y 4 sin cos , 0 58. cos sin ,, 00hallar el 2área de la región. Área los ejercicios < < . 58. x 2 cos , y 2 siny 60, , 0 x 2 cos 2 , y 2 sin , 0 (a) Use aa graphing to graph andparámetro x Eliminar 2 cot y utility 4 sinpara , 0the < curve. b) el mostrar que< la .ecuación rectan(a) Use graphing utility tocos graph the curve. 2 58. x 2 cos , y 2 sin , 58. 0 (a) Use a graphing utility to graph the curve. 2 2ad ygraphing 22 cos u (a) Use utility to graph the curve. gular de la curva serpentina es s 4 1 x 5 8x. 59. 60. x 5 3 sin u x 5 sen (b) Eliminate the parameter to show that the rectangular (a) Use a graphing to graph the curve. Area In Exercises 59 and 60, find the area (b) Eliminate the utility parameter to show that the rectangular Area In Exercises 59 and 60, find the area of of the the region. region. (b) equation Eliminateof the parameter to show that 2 the rectangular AreathatIn the Exercises 59 and 60, find the area of the 59 region. yy rectangular 8x. the is Eliminate the parameter to show sen cos rectangular u yIn5 sin of u the Exercises and 60, find the area of the regi 8x. ofthe the serpentine serpentine curve is 44 thatxx 22the (b) equation Eliminate parameter curve to(b)show Areaxy 5In322Exercises 59 and 60, Area find the region. y serpentine 8x.tangen- curve 59. xof equation 39 of the serpentine curve isy 4los puntos 60. sin xx area 22 cos y 8x. 4 x equation is En los ejercicios a 48, a) hallar dy dx 2 the de 59. 60. x 3 sin cos / equation of the serpentine curve is 4 x y 8x. p p 59. x 3 sin 60.x x 3 sin 2 cos In (a) points 59.60. 60. x 2 cos //dx u ≤ ≤ p cia horizontal,39– b)48, eliminar parámetro sea posible y dx and In Exercises Exercises 39– 48, (a) find findeldy and all allcuando points of of horizontal horizontal dy yyx0 ≤ sin 59. yxy2 2 232≤cos sin 2u cos cos 2 sin dxExercises In Exercises 39– 48, (a) find and allwhere points of(a)horizontal dy / tangency, (b) eliminate the parameter possible, and dx In 39–48, find and all points of horizontal dy y 2 cos y sin / c)In trazar la (b) curva representada por las tangency, eliminate the dy parameter possible, and Exercises 48, (a) find andecuaciones allwhere points paramétricas. of horizontal y y 2 cos y sin /dx y 2 cos sin tangency, (b)39– eliminate the parameter where possible, and (c) sketch curve represented by equations. tangency, (b) eliminate the and parameter where possible, and 00 (c) sketch the the curve represented by the the parametric parametric equations. tangency, (b) eliminate the parameter where possible, y y 22 22 (c) sketch the curve represented by the parametric equations. by the parametric 0 (c)by sketch the curve represented equations. 0 (c) sketch the curve represented the parametric equations. 2 2 2 02 39. 40. 32yy 4 yy 2 39. xx 22 5t, 40. xx tt 6, 6, yy tt 22 5t, yy 11 4t 4t 2 39. x 2 5t, y 1 4t 39.40.x x 2 t 5t,6, y y 1t 2 4t 2 y y 40. x t 6, y 3 ty y y2 y 39. x 121 5t, y 1 4t 40. x 1t1 6, y2 t 33 44 41. 42. 41. xx 1t ,, yy 2t 42. xx 1 1t ,, yy tt 22 2t 33 1 3 4 41. x 1t , y 2t 3 42.x x , 1t ,y y 2t t 2 3 3 4 23 41.42. 42. x , y t 2 343 2 t , y 2t 3 41. x x t t, y t t 2 31 x t 11 t 2 3 2 3 43. 44. 11 −3 −2 − 1 1 2 3 43. xx 2t 1 1 44. xx 2t 2t x 1 −1 43. x 2t 1 1 44.x x 2t 1 xx 11 43. 44. x 2t 1 −3 −2 −1 1 1 2 3 43. x 2t 1 44. x 2t 2t 1 1 x −−33 −−22 −−11− 2 11 22 33 −1 11 2t 11 1 xx 1 x 1 − 3 − 2 − 1−−11 1 2 3 y yy 1 1 −3 −2 −1 1 x 2 y t122 2t −−133 −2 −1 1 2 3 − 1 − 3 −2 − 3 − 2 − 1 1 2 3 t 2t 2 x −2 −1 1 2 3 −1 y t 1 2t −−21 x − 3 −2 −1−−11 1 2 3 y y yy 2 tt 2 1 2t 2t 2 y t 22 2t − 3 −2 −1 − 22 1 2 3 −1 t t 2t 2t 2 − 3 −2 −1 1 2 3 −2 − 1−−32 cos 45. t 2t 2t −−212 cos 45. xx 55t 3 45. x 5 cos −3 −2 x 5 cos 45. −3 − 2 En los ejercicios 61 a 64, representar gráficamente el punto y 3 4 sen 45. xy 53 cos −3 −2 4 sen y 3 4 sen en coordenadas polares y hallar las coordenadas rectangulaIn Exercises 61–64, plot the point in polar coordinates and find y 3 4 sen 46. In Exercises 61–64, plot the point in polar coordinates and find 3 cos 4 sen 10 cos 46. xxy 10 In 61–64, plot point in polar coordinates and find resExercises correspondientes althe punto. 46. x 10 cos the corresponding coordinates of In Exercises 61–64, plot and the point the corresponding rectangular coordinates of the the point. point. x 10 cos 46. In 61–64,rectangular plot the point in polar coordinates find in polar coordinates y 10 sen 46. xy 10 cos theExercises corresponding rectangular coordinates of the point. sen corresponding coordinates of the poin y 10 sen the corresponding rectangularthe coordinates of the rectangular point. 3 y 10 sen 33 47. cos 3 47. xxy 10 cossen 61. 5, 3 3 61. 5, 2 47. x cos3 3 3 47. x cos3 61. 5, 32 sen 47. yxy 44cos 61. 5, sen 3 2 5, 61. 2 y 4t sen 33 277 y 4 sen 3 48. 62. 6, 48. xxy ee4tt sen 7 62. 6, 7 48. x e 62. 6, 766 48. x et 6, 62. 48. yxy eet ttt 6, 6 62. 6 63. 3, 1.56 y e t 6 63. 3, 1.56 y e t y e 63. 3, 1.56 3, 1.56 63. In Exercises 49– 52, find all points (if any) of horizontal and 64. 2, 2.45 3, 1.56 63. In los Exercises 49–49 52,a find all points any) of horizontal 64. 2, 2.45 En ejercicios 52, hallar todos(if puntos (si los hay)and de In Exercises 49– 52, find all points (iflosany) of horizontal and 2, horizontal 2.45 vertical tangency to the curve. Use aa graphing utility to confirm In Exercises 49– 52, find all and points (if 64. any) of and 2, 2.45 64. vertical tangency to the curve. Use graphing utility to confirm In Exercises 49– 52, find all points (if any) of horizontal 2, 2.45 64. tangencia horizontal y vertical a la acurva. Usarutility una herramienvertical tangency to the curve. Use graphing to confirm In Exercises 65–68, the your results. vertical tangency to the curve. Use a graphing utility to confirm In Exercises 65–68, the rectangular rectangular coordinates coordinates of of aa point point are are your results. vertical tangency to the curve. Use a graphing utility to confirm ta de graficación para confirmar los resultados. In Exercises 65–68, the rectangular coordinates ofthe a point are your results. given. Plot the point and find two sets of polar coordinates of En los ejercicios 65 a 68, se dan las coordenadas rectangulares de coordinates of a In Exercises 65–68, rectangular your results. given. Plot the point and find two sets of polar coordinates of the the In Exercises 65–68, the rectangular coordinates of a point are yourx results. 2 y 2t 49. 5 t, 2 given. Plot the point and find two sets Plot of polar coordinates ofpares the sets of polar coordina 49. x 5 t, y 2t 2 point for 0 < 2 . un punto. Representar gráficamente el punto y hallar dos given. the point and find two point for 0 < 2 . given. Plot the point and find two sets of polar coordinates of the 49. x 5 t, y 2t 3 2 49. x 5 t, y 2t 2 point for 0 <2 . 50. 49. t, yy t2t de coordenadas polares para point for 0 <2 . t3 2t 2, 2t 50. xx t5t 2, point for 40 < 2 . del punto 65. 66. 4, 0, 77 50. x t 2, y t33 2t 50. x t 2, y t3 2t 65. 66. 4, 4 0, x 2 2 sen , y 1 cos 51. y , t y 2t1 cos 50. x t2 2, 65. 4, 4 66.4, 0, 4 7 2 sen 51. 65.68. 66. 0, 7 67. 33 cos x 2 2 sen , y 1 cos 51. x 2 2 sen , y 1 51. 65. 66. 7 67. 4, 1, 68. 0, 3, 1, 334 3, x 2 2 cos , y 2 sen 2 52. sen 1 cos 51. 67. 68. 1, 3 3, 1, 3 3 52. x 2 2 cos , y 2 sen 2 67. 68. 3, 3 52. x 2 2 cos , y 2 sen 67. 68. 1, 3 3, 3 52.22 x 2 2 cos , y 2 sen 2 52. x 2 2 cos , y 2 sen 10-7.qxd 3/12/09 760 17:01 Page 760 CAPÍTULO 10 Cónicas, ecuaciones paramétricas y coordenadas polares En los ejercicios 69 a 76, pasar la ecuación polar a la forma rectangular. 107. Encontrar los puntos de intersección de las gráficas de r 5 1 2 cos u y r 5 1 1 sen u. 69. r 5 3 cos u 70. r 5 10 108. Encontrar los puntos de intersección de las gráficas de r 5 1 1 sen u y r 5 3 sen u. 71. r 5 22s1 1 cos u d 72. r 5 73. r2 1 2 2 cos u p 74. r 5 4 sec u 2 3 1 5 cos 2u 75. r 5 4 cos 2u sec u 76. u 5 En los ejercicios 109 a 112, usar una herramienta de graficación para representar la ecuación polar. Dar una integral para encontrar el área de la región dada y usar las funciones de integración de una herramienta de graficación para aproximar el valor de la integral con una precisión de dos cifras decimales. 2 3p 4 En los ejercicios 77 a 80, transformar la ecuación rectangular a la forma polar. 77. sx 2 1 y 2d 2 5 ax 2 y 79. x2 1 y2 5 a2 1 y arctan x 78. x 2 1 y 2 2 4 x 5 0 2 2 80. s x2 1 1 25 y d arctan x y2 109. Interior de r 5 sen sin u cos 2 u sin 3u 110. Interior de r 5 4 sen 111. Interior común de r 5 3 y r 2 5 18 sen sin 2u 112. Región limitada por el eje polar r 5 eu para 0 ≤ u ≤ p 2 a2 En los ejercicios 113 y 114, hallar la longitud de la curva sobre el intervalo dado. En los ejercicios 81 a 92, trazar la gráfica de la ecuación polar. p 12 81. r 5 6 82. u 5 83. r 5 2sec u 84. r 5 3 csc u 85. r 5 22s1 1 cos u d 86. r 5 3 2 4 cos u 87. r 5 4 2 3 cos u 88. r 5 4u 89. r 5 23 cos 2u 90. r 5 cos 5u sin22 2u 91. r 2 5 4 sen 92. r 2 5 cos 2u En los ejercicios 93 a 96, usar una herramienta de graficación para representar la ecuación polar. 93. r 5 3 cossu 2 py4d 95. r 5 4 cos 2u sec u Ecuación polar 113. r 5 as1 2 cos ud 0 ≤ u ≤ p 114. r 5 a cos 2u 2 En los ejercicios 97 y 98, a) hallar las tangentes en el polo, b) hallar todos los puntos de tangencia horizontal y vertical, y c) usar una herramienta de graficación para representar la ecuación polar y dibujar una recta tangente a la gráfica en u 5 p/6. p p ≤ u ≤ 2 2 En los ejercicios 115 y 116, dar una integral que represente el área de la superficie generada por revolución de la curva en torno a una recta dada. Usar una herramienta de graficación para aproximar la integral. Ecuación polar Intervalo Eje de revolución 115. r 5 1 1 4 cos u p 0 ≤ u ≤ 2 Eje polar sin u 116. r 5 2 sen 0 ≤ u ≤ 94. r 5 2 sin sen u cos 2 u 96. r 5 4 ssec u 2 cos ud Intervalo p 2 u5 p 2 En los ejercicios 117 a 122, trazar e identificar la gráfica. Usar una herramienta de graficación para confirmar los resultados. 117. r 5 2 1 2 sen sin u 118. r 5 2 1 1 cos u 119. r 5 6 3 1 2 cos u 120. r 5 4 5 2 3 sin sen u En los ejercicios 99 y 100, mostrar que las gráficas de las ecuaciones polares son ortogonales en el punto de intersección. Usar una herramienta de graficación para confirmar los resultados. 121. r 5 4 2 2 3 sen sin u 122. r 5 8 2 2 5 cos u 99. r 5 1 1 cos u En los ejercicios 123 a 128, hallar la ecuación polar de la recta o cónica con su foco en el polo. 97. r 5 1 2 2 cos u r 5 1 2 cos u 98. r 2 5 4 sen sin 2u 100. r 5 a sin sen u r 5 a cos u 123. Círculo 124. Recta En los ejercicios 101 a 106, hallar el área de la región. Centro: s5, py2d Punto solución: (0, 0) 101. Un pétalo de r 5 3 cos 5u Punto solución: (0, 0d Pendiente: !3 102. Un pétalo de r 5 2 sen 6u 103. Interior de r 5 2 1 cos u sin u d 104. Interior de r 5 5s1 2 sen sin 2u 105. Interior de r 2 5 4 sen 106. Interior común a r 5 4 cos u y r 5 2 125. Parábola Vértice: s2, pd 127. Elipse Vértices: s5, 0d, s1, pd 126. Parábola Vértice: s2, py2d 128. Hipérbola Vértices: s1, 0d, s7, 0d 10-7.qxd 3/12/09 17:01 1059997_100R.qxp 9/2/08 3:52Page PM 761 Page 761 P.S. Solución de problemas Problem Solving 761 761 SP Solución de problemas P.S. P R O B L E M S O LV I N G 3 4yand 1. la parabola parábola xx22554y y lathe cuerda 1. Considerar Consider the focalfocal chordyy554 34xx111.1. a) la cuerda focal. (a)Dibujar Sketch la thegráfica graph de of la theparábola parabolay and the focal chord. b) que the las tangent rectas tangentes a laparabola parábolaatenthe losendpoints extremos (b)Mostrar Show that lines to the deoflathe cuerda focal se cortan en ángulo recto. focal chord intersect at right angles. c) que the las tangent rectas tangentes a laparabola parábolaatenthe losendpoints extremos (c)Mostrar Show that lines to the deoflathe cuerda focal se cortan en la directriz de la parábola. focal chord intersect on the directrix of the parabola. 5 4py 4py and 2. la parabola parábola xx22 5 y una deofsus focales. 2. Considerar Consider the one itscuerdas focal chords. a) Mostrar que las rectas tangentes a la parábola en los extremos (a) Show that the tangent lines to the parabola at the endpoints deoflathe cuerda focal se cortan en ángulos rectos. focal chord intersect at right angles. b) que the las tangent rectas tangentes a laparabola parábolaatenthe losendpoints extremos (b)Mostrar Show that lines to the deoflathe cuerda focal se cortan en la directriz de la parábola. focal chord intersect on the directrix of the parabola. 3. el teorema 10.2, la Property propiedad reflexiónasde una 3. Demostrar Prove Theorem 10.2, Reflective of de a Parabola, shown parábola, como se ilustra en la figura. in the figure. yy PP xx 4. Consider the hyperbola 4. Considerar la hipérbola x2 y2 2 5 1 xa22 yb22 2 5 1 a2 b2 with foci F1 and F2, as shown in the figure. Let T be the tangent linefocos at a point the se hyperbola. thatSea incoming raystanof F1 y FM2, on T la recta con como ilustra enShow la figura. light en aimed at one are reflected by aque hyperbolic gente un punto de la hipérbola. Mostrar los rayosmirror de luz M focus toward theenother focus.son reflejados por un espejo hiperbólico incidente un foco hacia el otroy foco. y y B y A M b T aM F2 F1 b T a F2 a) Mostrar quethe el area área of dethe la región (a) Show that regiones is pab. b) Mostrar quethe el solid volumen delspheroid) sólido (esferoide genera(b) Show that (oblate generatedoblato) by revolving do revolución deminor la región torno al ejehas menor de la thepor region about the axis en of the ellipse a volume 2 by3 y el área de la superficie es 2 by3 elipse 4pand of V 5es4Vp 5 a surface area of S 5 2pa2 1 p 1be 2 ln111 12 ee2. 2 (c) Show that the solid (prolate spheroid) generated by c) Comprobar que el volumen del sólido (esferoide prolato) revolving the region about the major axis of the ellipse has a generado por revolución de la región alrededor del eje mayor volume of V 5 4pab2y3 and a surface area of de la elipse es V 5 4pab2y3 y el área de la superficie es ab S 5 2pb2 1 2p ab arcsin e. 2 e. S 5 2pb 1 2p e arcsen arcsin e. e 7. The curve given by the parametric equations 7. La curva descrita por las ecuaciones2 paramétricas 1 2 t2 ts1 2 t d xstd 5 ystd 5 and 2 2 11 1 2 tt 2 ts1 121t 2td y xstd 5 y s t d 5 t2 1 1 t2 is called1 a1strophoid. 11 22 (a) Find a rectangular equation of the strophoid. se denomina estrofoide. (b) Find a polar equation of the strophoid. a) Hallar una ecuación rectangular de la estrofoide. FF F1 2ya 2yb 2 21 2 25 1yy2yb 51,1, 6. Consider Considerar regiónbounded limitadabypor elipsexx2ya thelaregion thelaellipse con excentricidad e 5cya. cya. with eccentricity e 5 O x O P (c) Sketchuna a graph of the strophoid. b) Hallar ecuación polar de la estrofoide. (d) Find the equations of the two tangent lines at the origin. c) Trazar una gráfica de la estrofoide. (e) Find the points ondethelasgraph at which the tangent lines are d) Hallar la ecuación dos rectas tangentes en el origen. horizontal. e) Hallar los puntos de la gráfica en los que las rectas tangentes 8. Findson a rectangular equation of the portion of the cycloid given by horizontales. the parametric equations x 5 asu 2 sin ud and y 5 as1 2 cos ud, 8. Hallar una ecuación rectangular para la porción de la cicloide 0 # u # p, as shown in the figure. dada por las ecuaciones paramétricas x 5 a(u 2 sen u) y y 5 a y (1 2cos u), 0 ≤ u ≤ p, como se muestra en la figura. y 2a B Aθ P a c θ a c 2a x O aπ O aπ x x 9. Consider the cornu spiral given by Figure for 4 Figure for 5 y-axis 5. Figura Consider a circle of radius a tangent to thepara para 4 Figura 5 and the line x 5 2a, as shown in the figure. Let A be the point where the segment OBunintersects the circle. cissoidalofeje Diocles y y a consists círculo con radio aThe tangente la recta 5. Considerar OPla5 AB. Sea A el punto en el cual el points such thaten comoPse ilustra figura. xof5all2a, segmento corta el círculo. Lacissoid. cisoide de Diocles consiste de (a) Find aOB polar equation of the todos los puntos P tales que OP 5 AB. (b) Find a set of parametric equations for the cissoid that does a) Hallar una ecuación polar de la cisoide. not contain trigonometric functions. b) conjunto de ecuaciones paramétricas (c)Hallar Find aunrectangular equation of the cissoid. para la cisoide que no contengan funciones trigonométricas. c) Hallar la ecuación rectangular de la cisoide. E E t E t p u2 pu 2 xstd 5 cos du and ystd 5 sin du. 9. Considerar la espiral de Cornu dada por 2 2 0 0 1 2 E 1 2 t (a) Use at graphing p u2 utility to graph the spiral pu 2 over the interval sen y xstd 2 5p #cos du y s t d 5 sin du. t # 2p. 2 0 1 2 0 1 2 (b) Show that the cornu spiral is symmetric with respect to the a) Usar una herramienta de graficación para representar la espiorigin. ral en el intervalo p cornu ≤ t ≤ p. (c) Find the length of 2 the spiral from t 5 0 to t 5 a. What b) Mostrar que laofespiral cornu es tsimétrica 5 2 p torespecto is the length the spiral from t 5 p ? al origen. c) Hallar la longitud de la espiral cornu desde t 5 0 hasta t 5 a. ¿Cuál es la longitud de la espiral desde t 5 2 p hasta t 5 p ? 10-7.qxd 3/12/09 762 17:01 Page 762 CAPÍTULO 10 Cónicas, ecuaciones paramétricas y coordenadas polares 10. Una partícula se mueve a lo largo de la trayectoria descrita por las ecuaciones paramétricas x 5 1yt y y 5 sen sin tyt, con 1 ≤ t < `, como se muestra en la figura. Hallar la longitud de esta trayectoria. y 15. Un controlador de tráfico aéreo ubica a la misma altitud dos aviones que vuelan uno hacia el otro (ver la figura). Sus trayectorias de vuelo son 20° y 315°. Un avión está a 150 millas del punto P con una velocidad de 375 millas por hora. El otro se encuentra a 190 millas del punto P con una velocidad de 450 millas por hora. 1 y x 1 −1 20° 11. Sean a y b constantes positivas. Hallar el área de la región del primer cuadrante limitada por la gráfica de la ecuación polar ab r5 , sa sen sin u 1 b cos ud p 0 ≤ u ≤ . 2 a) Mostrar que el área del triángulo es Asad 5 E a 1 2 E a sec2 u du. 0 x a) Hallar ecuaciones paramétricas para la trayectoria de cada avión donde t es tiempo en horas, y t 5 0 corresponde al instante en que el controlador de tráfico aéreo localiza a los aviones. b) Emplear el resultado del inciso a) para expresar la distancia entre los aviones como función de t. sec2 u du. 0 c) Usar el inciso b) para deducir la fórmula para la derivada de la función tangente. y 1 (−1, 0) (1, 0) x α 150 millas 45° P 12. Considerar el triángulo rectángulo de la figura. b) Mostrar que tan a 5 190 millas 1 −1 1 −1 c) Usar una herramienta de graficación para representar la función del inciso b). ¿Cuándo será mínima la distancia entre los aviones? Si los aviones deben conservar una distancia entre ellos de por lo menos tres millas, ¿se satisface este requerimiento? 16. Usar una herramienta de graficación para trazar la curva que se muestra abajo. La curva está dada por r 5 e cos u 2 2 cos 4u 1 sen sin55 u . 12 ¿Sobre qué intervalo debe variar u para generar la curva? Figura para 12 Figura para 13 13. Determinar la ecuación polar del conjunto de todos los puntos sr, ud, el producto de cuyas distancias desde los puntos s1, 0d y s21, 0d es igual a 1, como se observa en la figura. 14. Cuatro perros se encuentran en las esquinas de un cuadrado con lados de longitud d. Todos los perros se mueven en sentido contrario al de las manecillas del reloj a la misma velocidad y en dirección al siguiente perro, como se muestra en la figura. Hallar la ecuación polar de la trayectoria de un perro a medida que se acerca en espiral hacia el centro del cuadrado. d PARA MAYOR INFORMACIÓN Para más información sobre esta curva, consultar el artículo “A Study in Step Size” de Temple H. Fay en Mathematics Magazine. d d d 17. Usar una herramienta de graficación para representar la ecuación polar r 5 cos 5u 1 n cos u, para 0 ≤ u < p y para los enteros desde n 5 25 hasta n 5 5. ¿Qué valores de n producen la porción de la curva en forma de “corazón”? ¿Qué valores de n producen la porción de la curva en forma de “campana”? (Esta curva, creada por Michael W. Chamberlin, fue publicada en The College Mathematics Journal.) Larson-11-01.qxd 3/12/09 17:04 Page 763 1053714_cop11.qxd 10/27/08 10:37 AM Page 763 11 11 11 Vectors and the Vectores y la geometría Vectors and the Geometry of Space del espacio Geometry of Space En capítulo se introducen Thiseste chapter introduces vectors los andvecthe tores y el sistema de coordenadas tridithree-dimensional coordinate system. mensional. vectores se usan para This chapter introduces vectors and the Vectors are Los used to represent lines and representar rectas y planos, y también three-dimensional coordinate system. planes, and are also used to represent para representar cantidades como fuerza Vectors aresuch usedasto represent lines and quantities force and velocity. The ythree-dimensional velocidad. Elalso sistema de coordenadas planes, and are used to represent coordinate system is used tridimensional se force utiliza para representar quantities such as and The to represent surfaces such asvelocity. ellipsoids and superficies como elipsoides y conos three-dimensional coordinate system is used elliptical cones. Much of the materialelípticos. parte delsuch material enonlos to surfaces as ellipsoids and in represent the Gran remaining chapters relies ancapítulos restantes se fundamenta en el elliptical cones. Much of the material understanding of this system. entendimiento este sistema. in the remainingdechapters relies on an In this chapter, you should learn the understanding of this system. En este capítulo, se aprenderá: following. In chapter, youvectores, should learn theopen this Cómo escribir realizar ■ How to write vectors, perform basic following. raciones vectoriales básicas y repre■ vector represent sentar operations, vectores de and manera gráfica. ■ How to write vectors, perform basic vectors graphically. ( 11.1 ) (11.1) operations, and represent ■ vector ■ How to plot points in a three-dimensional graphically. ( 11.1 ) n vectors Cómo determinar en unvectors sistecoordinate system puntos and analyze ma de coordenadas tridimensional y ■ How to plot points in a three-dimensional in space. (11.2) analizar vectores espacio.vectors (11.2) coordinate system en andelanalyze ■ How to find the dot product of two space. (11.2) el producto escalar n in Cómo encontrar vectors (in the plane or in space). (11.3) de dos vectores (en product el planoofy two en el ■ How to find the dot ■ How to find the cross product of two espacio). ( 11.3 ) vectors (in the plane or in space). (11.3) vectors (in space). (11.4) n How Cómo el producto vectorial ■ toencontrar find the cross product of two de ■ How to find equations of lines and planes dos vectores (en el (espacio). vectors (in space). 11.4) (11.4) in space, and how to sketch their graphs. n How las ecuaciones ■ find equations of lines anddeplanes (Cómo 11.5to ) encontrar y planos espacio, y cómo inrectas space, and howentoelsketch their graphs. ■ How to recognize and write equations (dibujar 11.5) sus gráficas. (11.5) of cylindrical and quadric surfaces and n How Cómo y escribir ecuaciones ■ to reconocer recognize and write equations of surfaces of revolution. (11.6 ) decylindrical superficiesand cilíndricas y cuadráticas of quadric surfaces and ■ How to use cylindrical and spherical y surfaces las superficies de revolución. of of revolution. (11.6) (11.6) coordinates to represent surfaces in n How Cómo cilíndricas ■ to(utilizar use cylindrical and spherical space. 11.7 ) coordenadas y esféricas para representar superficies coordinates to represent surfaces in en el espacio. ( 11.7 ) space. (11.7) Mark Hunt/Hunt Stock Dos remolcadores están empujando un barco trasatlántico, comoboat se muestra en la Two tugboats are pushing an ocean liner, as shown above. Each is exerting Mark Hunt/Hunt Stock foto. Cada barco ejerceWhat una fuerza de 400 libras. ¿Cuál la fuerza en el ■a force of 400 pounds. is the resultant force on the es ocean liner?resultante (See Two tugboats pushing an sección ocean liner, shown above. Each boat is exerting barco trasatlántico? (Ver 11.1,asejemplo 7.) Section 11.1,are Example 7.)la ■ a force of 400 pounds. What is the resultant force on the ocean liner? (See Section 11.1, Example 7.) v v u u u u v v u u v u+v u+v v Vectors indicate quantities that involve both magnitude and direction. In Chapter 11, you will study operations of vectors in the plane and in space. You will also learn how to represent vector operations geometrically. For example, the graphs Los vectores indican cantidades que implican tanto magnitud como dirección. capítulo 11 se estudiarán operaVectors indicate quantities thataddition involve both and direction. In Chapter En 11,elyou will study operations of vectors shown above represent vector in themagnitude plane. ciones de vectores el plano y enalso el espacio. También se aprenderá cómo representar operaciones de vectores de in the plane and in en space. You will learn how to represent vector operations geometrically. For example, the graphs manera geométrica. Porvector ejemplo, las gráficas que se muestran arriba representan adición de vectores en el plano. shown above represent addition in the plane. 763 763 763 Larson-11-01.qxd 764 3/12/09 17:04 CAPÍTULO 11 Page 764 Vectores y la geometría del espacio 11.1 Vectores en el plano n n n n Expresar un vector mediante sus componentes. Realizar operaciones vectoriales e interpretar los resultados geométricamente. Expresar un vector como combinación lineal de vectores unitarios estándar o canónicos. Usar vectores para resolver problemas de fuerza o velocidad. Las componentes de un vector Q Muchas cantidades en geometría y física, como el área, el volumen, la temperatura, la masa y el tiempo, se pueden caracterizar por medio de un solo número real en unidades de medición apropiadas. Estas cantidades se llaman escalares, y al número real se le llama escalar. Otras cantidades, como la fuerza, la velocidad y la aceleración, tienen magnitud y dirección y no pueden caracterizarse completamente por medio de un solo número real. Para representar estas cantidades se usa un segmento de recta dirigido, como se muestra en la figura 11.1. El segmento de recta dirigido PQ tiene como punto inicial P y como punto final Q y su longitud (o magnitud) se denota por i PQ i. Segmentos de recta dirigidos que tienen la misma longitud y dirección son equivalentes, como se muestra en la figura 11.2. El conjunto de todos los segmentos de recta dirigidos que son equivalentes a un segmento de recta dirigido dado PQ es un vector en el plano y se denota por v 5 PQ . En los libros, los vectores se denotan normalmente con letras minúsculas, en negrita, como u, v y w. Cuando se escriben a mano, se suelen denotar por medio de letras con una flecha sobre ellas, como → u,→ v y→ w. Es importante notar que un vector en el plano se puede representar por medio de muchos segmentos de recta dirigidos diferentes, todos apuntando en la misma dirección y todos de la misma longitud. Punto final PQ P Punto inicial Un segmento de recta dirigido \ Figura 11.1 \ \ Segmentos de recta dirigidos equivalentes Figura 11.2 EJEMPLO 1 \ Representación de vectores por medio de segmentos de recta dirigidos Sea v el vector representado por el segmento dirigido que va de (0, 0) a (3, 2), y sea u el vector representado por el segmento dirigido que va de (1, 2) a (4, 4). Mostrar que v y u son equivalentes. Solución Sean P(0, 0) y Q(3, 2) los puntos inicial y final de v, y sean R(l, 2) y S(4, 4) los puntos inicial y final de u, como se muestra en la figura 11.3. Para mostrar que PQ y RS tienen la misma longitud se usa la fórmula de la distancia. \ y i PQ i 5 !s3 2 0d 2 1 s2 2 0d 2 5 !13 Longitud de PQ . i RS i 5 !s4 2 1d 2 1 s4 2 2d 2 5 !13 Longitud de RS . \ \ (4, 4) 4 S (3, 2) (1, 2) R 1 \ Pendiente de PQ 5 Q v x 2 3 4 Pendiente de RS 5 \ Los vectores u y v son iguales Figura 11.3 \ 220 2 5 320 3 y \ P (0, 0) 1 \ Los dos segmentos tienen la misma dirección, porque ambos están dirigidos hacia la derecha y hacia arriba sobre rectas que tienen la misma pendiente. u 3 2 \ 422 2 5 421 3 \ Como PQ y RS tienen la misma longitud y la misma dirección, se concluye que los dos vectores son equivalentes. Es decir, v y u son equivalentes. Larson-11-01.qxd 3/12/09 17:04 Page 765 SECCIÓN 11.1 y 765 El segmento de recta dirigido cuyo punto inicial es el origen a menudo se considera el representante más adecuado de un conjunto de segmentos de recta dirigidos equivalentes como los que se muestran en la figura 11.3. Se dice que esta representación de v está en la posición canónica o estándar. Un segmento de recta dirigido cuyo punto inicial es el origen puede representarse de manera única por medio de las coordenadas de su punto final Qsv1, v2 d, como se muestra en la figura 11.4. 4 3 (v1, v2) 2 Vectores en el plano Q DEFINICIÓN DE UN VECTOR EN EL PLANO MEDIANTE SUS COMPONENTES v 1 v = ⟨v1, v2⟩ (0, 0) P x 1 2 3 4 Posición estándar de un vector Si v es un vector en el plano cuyo punto inicial es el origen y cuyo punto final es sv1, v2 d, entonces el vector v queda dado mediante sus componentes de la siguiente manera v 5 kv1, v2l. Figura 11.4 Las coordenadas v1 y v2 son las componentes de v. Si el punto inicial y el punto final están en el origen, entonces v es el vector cero (o vector nulo) y se denota por 0 5 k0, 0l. Esta definición implica que dos vectores u 5 ku1, u 2 l y v 5 kv1, v2 l son iguales si y sólo si u1 5 v1 y u 2 5 v2. Los procedimientos siguientes pueden usarse para convertir un vector dado mediante un segmento de recta dirigido en un vector dado mediante sus componentes o viceversa. 1. Si P s p1, p2 d y Q sq1, q2 d son los puntos inicial y final de un segmento de recta dirigido, el vector v representado por PQ , dado mediante sus componentes, es kv1, v2l 5 kq1 2 p1, q2 2 p2 l. Además, de la fórmula de la distancia es posible ver que la longitud (o magnitud) de v es \ i v i 5 !sq1 2 p1 d 2 1 sq2 2 p2 d 2 5 !v12 1 v22 . Longitud de un vector. 2. Si v 5 kv1, v2l, v puede representarse por el segmento de recta dirigido, en la posición canónica o estándar, que va de Ps0, 0d a Q sv1, v2 d. A la longitud de v también se le llama la norma de v. Si i v i 5 1, v es un vector unitario. Y i v i 5 0 si y sólo si v es el vector cero 0. y EJEMPLO 2 Hallar las componentes y la longitud de un vector Q (−2, 5) 6 Hallar las componentes y la longitud del vector v que tiene el punto inicial (3, 27) y el punto final (22, 5). 4 x −6 −4 −2 2 −2 4 6 v v1 5 q1 2 p1 5 22 2 3 5 25 −4 v2 5 q2 2 p2 5 5 2 s27d 5 12. −6 P (3, −7) −8 Vector v dado por medio de sus componentes: v 5 k25, 12l Figura 11.5 Solución Sean Ps3, 27d 5 s p1, p2 d y Qs22, 5d 5 sq1, q2 d. Entonces las componentes de v 5 kv1, v2 l son Así, como se muestra en la figura 11.5, v 5 k25, 12l, y la longitud de v es i v i 5 !s25d 2 1 122 5 !169 5 13. Larson-11-01.qxd 766 3/12/09 17:04 CAPÍTULO 11 Page 766 Vectores y la geometría del espacio Operaciones con vectores DEFINICIÓN DE LA SUMA DE VECTORES Y DE LA MULTIPLICACIÓN POR UN ESCALAR Sean u 5 ku1, u2 l y v 5 kv1, v2 l vectores y sea c un escalar. v 1 v 2 2v 3 − v −v 2 1. La suma vectorial de u y v es el vector u 1 v 5 ku1 1 v1, u2 1 v2l. 2. El múltiplo escalar de c y u es el vector cu 5 kcu1, cu 2l. 3. El negativo de v es el vector 2v 5 s21dv 5 k2v1, 2v2 l. 4. La diferencia de u y v es u 2 v 5 u 1 s2vd 5 ku1 2 v1, u2 2 v2l. La multiplicación escalar por un vector v Figura 11.6 Geométricamente, el múltiplo escalar de un vector v y un escalar c es el vector que tiene c veces la longitud de v, como se muestra en la figura 11.6. Si c es positivo, cv tiene la misma dirección que v. Si c es negativo, cv tiene dirección opuesta. La suma de dos vectores puede representarse geométricamente colocando los vectores (sin cambiar sus magnitudes o sus direcciones) de manera que el punto inicial de uno coincida con el punto final del otro, como se muestra en la figura 11.7. El vector u 1 v, llamado el vector resultante, es la diagonal de un paralelogramo que tiene u y v como lados adyacentes. || v u+v u u u+v u The Granger Collection v v Para hallar u 1 v, 1) hacer coincidir el punto inicial de v con el punto final de u, o bien Figura 11.7 2) hacer coincidir el punto inicial de u con el punto final de v WILLIAM ROWAN HAMILTON (1805-1865) Algunos de los primeros trabajos con vectores fueron realizados por el matemático irlandés William Rowan Hamilton. Hamilton dedicó muchos años a desarrollar un sistema de cantidades semejantes a vectores llamados cuaterniones. Aunque Hamilton estaba convencido de las ventajas de los cuaterniones, las operaciones que definió no resultaron ser buenos modelos para los fenómenos físicos. No fue sino hasta la segunda mitad del siglo XIX cuando el físico escocés James Maxwell (1831-1879) reestructuró la teoría de los cuaterniones de Hamilton dándole una forma útil para la representación de cantidades como fuerza, velocidad y aceleración. La figura 11.8 muestra la equivalencia de las definiciones geométricas y algebraicas de la suma de vectores y la multiplicación por un escalar y presenta (en el extremo derecho) una interpretación geométrica de u 2 v. (ku1, ku2) (u1 + v1, u2 + v2) (u1, u2) ku u+v ku2 u u2 v2 v1 Suma vectorial Figura 11.8 u1 u + (−v) u1 u−v u u2 u (v1, v2) v −v (u1, u2) v ku1 Multiplicación escalar Sustracción de vectores Larson-11-01.qxd 3/12/09 17:04 Page 767 SECCIÓN 11.1 EJEMPLO 3 Vectores en el plano 767 Operaciones con vectores Dados v 5 k22, 5l y w 5 k3, 4l, encontrar cada uno de los vectores. 1 b) w 2 v a) 2 v c) v 1 2w Solución a) 12v 5 k 12s22d, 12s5dl 5 k 21, 52l b) w 2 v 5 kw1 2 v1, w2 2 v2 l 5 k3 2 s22d, 4 2 5l 5 k5, 21l c) Usando 2w 5 k6, 8l, se tiene v 1 2w 5 k22, 5l 1 k6, 8l 5 k22 1 6, 5 1 8l 5 k4, 13l. La suma de vectores y la multiplicación por un escalar comparten muchas propiedades con la aritmética ordinaria, como se muestra en el teorema siguiente. TEOREMA 11.1 PROPIEDADES DE LAS OPERACIONES CON VECTORES Sean u, v y w los vectores en el plano, y sean c y d escalares. 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. u1v5v1u su 1 vd 1 w 5 u 1 sv 1 wd u105u u 1 s2ud 5 0 csdud 5 scd du sc 1 d du 5 cu 1 du csu 1 vd 5 cu 1 cv 1sud 5 u, 0sud 5 0 Propiedad conmutativa. Propiedad asociativa. Propiedad de la identidad aditiva. Propiedad del inverso aditivo. Propiedad distributiva. Propiedad distributiva. DEMOSTRACIÓN La demostración de la propiedad asociativa de la suma de vectores utiliza la propiedad asociativa de la suma de números reales. su 1 vd 1 w 5 fku1, u2l 1 kv1, v2lg 1 kw1, w2l 5 ku1 1 v1, u2 1 v2 l 1 kw1, w2 l 5 ksu1 1 v1d 1 w1, su2 1 v2 d 1 w2l 5 ku1 1 sv1 1 w1d, u2 1 sv2 1 w2 dl 5 ku1, u2 l 1 kv1 1 w1, v2 1 w2 l 5 u 1 sv 1 wd Asimismo, la demostración de la propiedad distributiva de la multiplicación escalar depende de la propiedad distributiva para los números reales. sc 1 ddu 5 sc 1 ddku1, u2l 5 ksc 1 dd u1, sc 1 dd u2 l 5 kcu1 1 du1, cu 2 1 du 2 l 5 kcu1, cu 2l 1 kdu1, du 2 l 5 cu 1 du Las otras propiedades pueden demostrarse de manera similar. Larson-11-01.qxd 768 3/12/09 17:04 CAPÍTULO 11 Page 768 Vectores y la geometría del espacio The Granger Collection Cualquier conjunto de vectores (junto con un conjunto de escalares) que satisfaga las ocho propiedades dadas en el teorema 11.1 es un espacio vectorial.* Las ocho propiedades son los axiomas del espacio vectorial. Por tanto, este teorema establece que el conjunto de vectores en el plano (con el conjunto de los números reales) forma un espacio vectorial. TEOREMA 11.2 LONGITUD DE UN MÚLTIPLO ESCALAR Sea v un vector y sea c un escalar. Entonces || i c v i 5 c i v i. EMMY NOETHER (1882-1935) La matemática alemana Emmy Noether contribuyó a nuestro conocimiento de los sistemas axiomáticos. Noether generalmente se reconoce como la principal matemática de la historia reciente. DEMOSTRACIÓN |c| es el valor absoluto de c. Como cv 5 kcv1, cv2l, se tiene que i cv i 5 ikcv1, cv2 li 5 !scv1d 2 1 scv2 d 2 5 !c 2 v12 1 c 2 v22 5 !c 2sv12 1 v22d || || 5 c !v12 1 v22 5 c ivi. PARA MAYOR INFORMACIÓN Para más información acerca de Emmy Noether, ver el artículo “Emmy Noether, Greatest Woman Mathematician” de Clark Kimberling en The Mathematics Teacher. En muchas aplicaciones de los vectores, es útil encontrar un vector unitario que tenga la misma dirección que un vector dado. El teorema siguiente da un procedimiento para hacer esto. TEOREMA 11.3 VECTOR UNITARIO EN LA DIRECCIÓN DE v Si v es un vector distinto de cero en el plano, entonces el vector u5 v 1 5 v ivi ivi tiene longitud 1 y la misma dirección que v. Como 1yi v i es positivo y u 5 s1yi v id v, se puede concluir que u tiene la misma dirección que v. Para ver que i u i 5 1, se observa que DEMOSTRACIÓN iui 5 i 1 i 1v i 2 v i | | 1 ivi ivi 1 5 ivi ivi 5 1. 5 Por tanto, u tiene longitud 1 y la misma dirección que v. Al vector u del teorema 11.3 se le llama un vector unitario en la dirección de v. El proceso de multiplicar v por 1yi v i para obtener un vector unitario se llama normalización de v. * Para más información sobre espacios vectoriales, ver Elementary Linear Algebra, 6a. ed., por Larson, Edwards y Falvo (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 2009). Larson-11-01.qxd 3/12/09 17:04 Page 769 SECCIÓN 11.1 EJEMPLO 4 Vectores en el plano 769 Hallar un vector unitario Hallar un vector unitario en la dirección de v 5 k22, 5l y verificar que tiene longitud 1. Solución Por el teorema 11.3, el vector unitario en la dirección de v es 7 8 v k22, 5l 1 22 5 5 5 k22, 5l 5 , . i v i !s22d2 1 s5d2 !29 !29 !29 Este vector tiene longitud 1, porque y !1 22292 1 1 5292 5 !294 1 2925 5 !2929 5 1. v 2 ! u 2 ! Generalmente, la longitud de la suma de dos vectores no es igual a la suma de sus longitudes. Para ver esto, basta tomar los vectores u y v de la figura 11.9. Considerando a u y v como dos de los lados de un triángulo, se puede ver que la longitud del tercer lado es iu 1 v i, y se tiene u+v x i u 1 v i ≤ i u i 1 i v i. La igualdad sólo se da si los vectores u y v tienen la misma dirección. A este resultado se le llama la desigualdad del triángulo para vectores. (En el ejercicio 91, sección 11.3, se pide demostrar esto.) Desigualdad del triángulo Figura 11.9 Vectores unitarios canónicos o estándar A los vectores unitarios k1, 0l y k0, 1l se les llama vectores unitarios canónicos o estándar en el plano y se denotan por i 5 k1, 0l y j 5 k0, 1l Vectores unitarios canónicos o estándar. como se muestra en la figura 11.10. Estos vectores pueden usarse para representar cualquier vector de manera única, como sigue. y v 5 kv1, v2l 5 kv1, 0l 1 k0, v2 l 5 v1 k1, 0l 1 v2k0, 1l 5 v1i 1 v2 j 2 Al vector v 5 v1 i 1 v2 j se le llama una combinación lineal de i y j. A los escalares v1 y v2 se les llama las componentes horizontal y vertical de v. 1 j = ⟨0, 1⟩ EJEMPLO 5 i = ⟨1, 0⟩ x 1 2 Vectores unitarios canónicos o estándar i y j Figura 11.10 Expresar un vector como combinación lineal de vectores unitarios Sea u el vector con punto inicial s2, 25d y punto final s21, 3d, y sea v 5 2i 2 j. Expresar cada vector como combinación lineal de i y j. a) u b) w 5 2u 2 3v Solución a) u 5 kq1 2 p1, q2 2 p2 l 5 k21 2 2, 3 2 s25dl 5 k23, 8l 5 23i 1 8j b) w 5 2u 2 3v 5 2s23i 1 8jd 2 3s2i 2 jd 5 26i 1 16j 2 6i 1 3j 5 212i 1 19j Larson-11-01.qxd 770 3/12/09 17:04 CAPÍTULO 11 Page 770 Vectores y la geometría del espacio y Si u es un vector unitario y u es el ángulo (medido en sentido contrario a las manecillas del reloj) desde el eje x positivo hasta u, el punto final de u está en el círculo unitario, y se tiene (cos θ , senθ ) 1 u sen u l 5 cos u i 1 sen u 5 kcos u, sin sin u j senθ θ x −1 cos θ 1 Vector unitario. como se muestra en la figura 11.11. Además, cualquier vector distinto de cero v que forma un ángulo u con el eje x positivo tiene la misma dirección que u y se puede escribir v 5 i v ikcos u, sen sin u l 5 i v i cos u i 1 i v i sen sin u j. −1 EJEMPLO 6 Ángulo u desde el eje x positivo hasta el vector u Escribir un vector de magnitud y dirección dadas El vector v tiene una magnitud de 3 y forma un ángulo de 308 5 py6 con el eje x positivo. Expresar v como combinación lineal de los vectores unitarios i y j. Figura 11.11 Solución Como el ángulo entre v y el eje x positivo es u 5 py6, se puede escribir lo siguiente. v 5 i v i cos u i 1 i v i sen sin u j 5 3 cos 5 p p i 1 3 sen sin j 6 6 3!3 3 i1 j 2 2 Aplicaciones de los vectores Los vectores tienen muchas aplicaciones en física e ingeniería. Un ejemplo es la fuerza. Un vector puede usarse para representar fuerza porque la fuerza tiene magnitud y dirección. Si dos o más fuerzas están actuando sobre un objeto, entonces la fuerza resultante sobre el objeto es la suma vectorial de los vectores que representan las fuerzas. EJEMPLO 7 Hallar la fuerza resultante Dos botes remolcadores están empujando un barco, como se muestra en la figura 11.12. Cada bote remolcador está ejerciendo una fuerza de 400 libras. ¿Cuál es la fuerza resultante sobre el barco? Solución Usando la figura 11.12, se pueden representar las fuerzas ejercidas por el primer y segundo botes remolcadores como F1 5 400kcos 208, sen sin 208l 5 400 coss208d i 1 400 sen sins208d j y F2 5 400kcoss2208d, sen sins2208dl 400 cos(−20°) F2 −20° 400 5 400 coss208d i 2 400 sen sins208d j. 400 sen(−20°) La fuerza resultante sobre el barco es x F1 400 20° 400 sen(20°) 400 cos(20°) Fuerza resultante sobre el barco ejercida por los dos remolcadores Figura 11.12 F 5 F1 1 F 2 5 f400 coss208d i 1 400 sen sins208d jg 1 f400 coss208d i 2 400 sen sins208d jg 5 800 coss208d i < 752i. Por tanto, la fuerza resultante sobre el barco es aproximadamente 752 libras en la dirección del eje x positivo. Larson-11-01.qxd 26/2/10 14:05 Página 771 SECCIÓN 11.1 771 Vectores en el plano En levantamientos topográficos y en la navegación, un rumbo es una dirección que mide el ángulo agudo que una trayectoria o línea de mira forma con una recta fija nortesur. En la navegación aérea, los rumbos se miden en el sentido de las manecillas del reloj en grados desde el norte. y N W E EJEMPLO 8 Hallar una velocidad S Un avión viaja a una altitud fija con un factor de viento despreciable, y mantiene una velocidad de 500 millas por hora con un rumbo de 330°, como se muestra en la figura 11.13a. Cuando alcanza cierto punto, el avión encuentra un viento con una velocidad de 70 millas por hora en dirección 45° NE (45° este del norte), como se muestra en la figura 11.13b. ¿Cuáles son la velocidad y la dirección resultantes del avión? v1 120° x Solución Usando la figura 11.13a, representar la velocidad del avión (solo) como a) Dirección sin viento v1 500 cos120 i 500 sen sin120 j. y La velocidad del viento se representa por el vector v2 v2 70 cos45 i 70 sen sin45 j. N W E La velocidad resultante del avión (en el viento) es S v v1 v2 500 cos120 i 500 sen sin120 j 70 cos45 i 70 sen sin45 j 200.5i 482.5j. v v1 Viento Para encontrar la velocidad y la dirección resultantes, escribir v v cos i sen sin j. Como v 200.52 482.52 522.5, se puede escribir θ x v 522.5 b) Dirección con viento 482.5 i j 522.5, cos112.6 i sen sin112.6 j . 200.5 522.5 522.5 La nueva velocidad del avión, alterada por el viento, es aproximadamente 522.5 millas por hora en una trayectoria que forma un ángulo de 112.6° con el eje x positivo. Figura 11.13 11.1 Ejercicios En los ejercicios 1 a 4, a) dar el vector v mediante sus componentes y b) dibujar el vector con su punto inicial en el origen. 1. 2. y (5, 4) 4 3 v 2 (1, 2) y 5. u: 3, 2 , 5, 6 (3, 4) 4 3 2 1 v x −1 −2 −1 1 2 3. 3 4 5 2 (3, −2) 2 4 2 v (−4, − 3) −6 (2, −3) v: 3, 10 , 9, 5 1 , 7, 7 4, 1 , 11, 4 v: 10, 13 , 25, 10 4 x − 4 −2 v: 2, 8. u: 2 En los ejercicios 9 a 16, se dan los puntos inicial y final de un vector v. a) Dibujar el segmento de recta dirigido dado, b) expresar el vector mediante sus componentes, c) expresar el vector como la combinación lineal de los vectores unitarios estándar i y j y d) dibujar el vector con el punto inicial en el origen. y (−1, 3) 4, 0 , 1, 8 4 5 6 1 2 4. y 6. u: v: 1, 4 , 3, 8 7. u: 0, 3 , 6, 1 x En los ejercicios 5 a 8, hallar los vectores u y v cuyos puntos inicial y final se dan. Mostrar que u y v son equivalentes. Punto inicial v (2, 1) Punto final Punto inicial Punto final 1 x −2 −1 1 2 9. 2, 0 11. 8, 3 5, 5 6, 1 10. 4, 6 3, 6 12. 0, 4 5, 1 Larson-11-01.qxd 772 26/2/10 CAPÍTULO 11 Punto inicial 13. 6, 2 15. 14:05 3 4 2, 3 Página 772 Vectores y la geometría del espacio Punto final Punto inicial 6, 6 14. 7, 1 3, 1 16. 0.12, 0.60 0.84, 1.25 1 2, 3 Punto final En los ejercicios 17 y 18, dibujar cada uno de los múltiplos escalares de v. En los ejercicios 41 a 44, hallar lo siguiente. a) b) u u u d) 3, 5 a) 2v b) 3v c) 7 2v d) v 1, 2 a) 4v b) 1 2v c) 0v d) v 3, 3 1 2 44. u 2, 4 v 5, 5 En los ejercicios 45 y 46, representar gráficamente u, v y u + v. Después demostrar la desigualdad del triángulo usando los vectores u y v. 2, 3 18. v 42. u 0, 1 v 2, 3 2 3v uv uv f) 41. u 1, 1 43. u 1, 17. v v v e) uv c) v 6v En los ejercicios 19 a 22, usar la figura para representar gráficamente el vector. 45. u 2, 1 , v 5, 4 46. u 3, 2 , v 1, 2 En los ejercicios 47 a 50, hallar el vector v de la magnitud dada y en la misma dirección que u. y Magnitud v u x 19. u 20. 2u 21. u v 22. u 2v 24. u 3, 8 v 2, 5 47. v 6 u 0, 3 48. v 4 u 1, 1 49. v 5 u 1, 2 50. v 2 u 3, 3 En los ejercicios 51 a 54, hallar las componentes de v dadas su magnitud y el ángulo que forma con el eje x positivo. En los ejercicios 23 y 24, hallar a) 23 u, b) v ⴚ uu,y c) 2u ⴙ 5v. 23. u 4, 9 Dirección v 8, 25 En los ejercicios 25 a 28, hallar el vector v donde u ⴝ 2, ⴚ1 y w ⴝ 1, 2 . Ilustrar geométricamente las operaciones vectoriales. 51. v 3, 0 52. v 5, 120 53. v 2, 150 54. v 4, 3.5 En los ejercicios 55 a 58, hallar las componentes de u + v dadas las longitudes de u y v y los ángulos que u y v forman con el eje x positivo. 55. u 1, u 0 56. u 4, u 0 v 3, v 45 25. v 32 u 26. v u w 27. v u 2w 28. v 5u 3w 57. u 2, u 4 v 2, v 60 58. u 5, u 0.5 v 1, v 2 En los ejercicios 29 y 30 se dan el vector v y su punto inicial. Hallar el punto final. 29. v 1, 3 ; punto inicial: (4, 2) v 5, v 0.5 Desarrollo de conceptos 30. v 4, 9 ; punto inicial: (5, 3) 59. Explicar, con sus propias palabras, la diferencia entre un escalar y un vector. Dar ejemplos de cada uno. En los ejercicios 31 a 36, encontrar la magnitud de v. 60. Describir geométricamente las operaciones de suma de vectores y de multiplicación de un vector por un escalar. 31. v 61. Identificar la cantidad como escalar o como vector. Explicar el razonamiento. 33. v 35. v 7i 4, 3 6i 5j 32. v 3i 34. v 12, 36. v 5 10i 3j En los ejercicios 37 a 40, hallar el vector unitario en la dirección de v y verificar que tiene longitud 1. 37. v 3, 12 38. v 5, 15 39. v 3 5 2, 2 40. v 6.2, 3.4 a) La velocidad en la boca de cañón de un arma de fuego. b) El precio de las acciones de una empresa. 62. Identificar la cantidad como escalar o como vector. Explicar el razonamiento. a) La temperatura del aire en un cuarto. b) El peso de un automóvil. Larson-11-01.qxd 26/2/10 14:05 Página 773 SECCIÓN 11.1 En los ejercicios 63 a 68, hallar a y b tales que v ⴝ au ⴙ bw, donde u ⴝ 1, 2 y w ⴝ 1, ⴚ1 . 63. v 2, 1 64. v 0, 3 65. v 3, 0 66. v 3, 3 67. v 1, 1 68. v 1, 7 En los ejercicios 69 a 74, hallar un vector unitario a) paralelo y b) normal a la gráfica de f en el punto dado. Después representar gráficamente los vectores y la función. Función Punto 69. f x x2 3, 9 1, 4 1, 1 2, 8 3, 4 70. f x x2 5 71. f x x3 72. f x x3 73. f x 25 x 2 76. u 4, 30 2 , 90 u v 6 , 120 77. Programación Se dan las magnitudes de u y v y los ángulos que u y v forman con el eje x positivo. Escribir un programa para una herramienta de graficación que calcule lo siguiente. a) u v y F2 110° 2 2.5 3 F1 4 33° 200° x −125° F3 3 b) u v c) El ángulo que u v forma con el eje x positivo d) Utilizar el programa para encontrar la magnitud y la dirección de la resultante de los vectores indicados. y 140° x 2 −10° F1 F2 81. Fuerza resultante Fuerzas con magnitudes de 500 libras y 200 libras actúan sobre una pieza de la máquina a ángulos de 30° y 45°, respectivamente, con el eje x (ver la figura). Hallar la dirección y la magnitud de la fuerza resultante. y 500 libras 180 N 30° x θ −45° En los ejercicios 75 y 76, expresar v mediante sus componentes, dadas las magnitudes de u y de u + v y los ángulos que u y u + v forman con el eje x positivo. 75. u 1, 45 80. y F3 4 , 1 74. f x tan x uv 79. 773 Vectores en el plano 275 N x 200 libras Figura para 81 Figura para 82 82. Análisis numérico y gráfico Fuerzas con magnitudes de 180 newtons y 275 newtons actúan sobre un gancho (ver la figura). El ángulo entre las dos fuerzas es de grados. a) Si 30, hallar la dirección y la magnitud de la fuerza resultante. b) Expresar la magnitud M y la dirección de la fuerza resultante en funciones de , donde 0 180. c) Usar una herramienta de graficación para completar la tabla. 0 30 60 90 120 150 180 M 45 u 20° −50° ␣ x 32 v d) Usar una herramienta de graficación para representar las dos funciones M y . e) Explicar por qué una de las funciones disminuye cuando aumenta mientras que la otra no. Para discusión 78. Los puntos inicial y final del vector v son (3, –4) y (9, 1), respectivamente. a) Escribir v en forma de componentes. b) Escribir v como la combinación lineal de los vectores unitarios estándar i y j. c) Dibujar v con su punto inicial en el origen. d) Encontrar la magnitud de v. En los ejercicios 79 y 80, usar una herramienta de graficación para encontrar la magnitud y la dirección de la resultante de los vectores. 83. Fuerza resultante Tres fuerzas de magnitudes de 75 libras, 100 libras y 125 libras actúan sobre un objeto a ángulos de 30°, 45° y 120°, respectivamente, con el eje x positivo. Hallar la dirección y la magnitud de la fuerza resultante. 84. Fuerza resultante Tres fuerzas de magnitudes de 400 newtons, 280 newtons y 350 newtons, actúan sobre un objeto a ángulos de 30°, 45° y 135°, respectivamente, con el eje x positivo. Hallar la dirección y la magnitud de la fuerza resultante. 85. Para pensar Considerar dos fuerzas de la misma magnitud que actúan sobre un punto. a) Si la magnitud de la resultante es la suma de las magnitudes de las dos fuerzas, hacer una conjetura acerca del ángulo entre las fuerzas. 1053714_1101.qxp Larson-11-01.qxd 774 774 10/27/08 10:37 AM Page 774 3/12/09 17:04 Page 774 CAPÍTULO Vectores la Geometry geometría del espacio Chapter 11 11 Vectors and ythe of Space b) resultante conjeturaabout acer0, hacer (b)SiIflathe resultantdeoflas thefuerzas forces es is 0, make una a conjecture cathe delangle ángulo entre las between thefuerzas. forces. 20° 20° NN 30° WO c) sermagnitude la magnitud resultante la suma de (c)¿Puede Can the of de thelaresultant bemayor greaterque than the sum las de las Explicar la respuesta. ofmagnitudes the magnitudes ofdos the fuerzas? two forces? Explain. SS 86. gráfico Consider Considerar dosforces fuerzas k20, 0 0l F1 F1 520, 86. Razonamiento Graphical Reasoning two andy F2 10 cos , sen . a) (a)Hallar Find iFF11 1 FF22 i.. c) gráfica inciso determinar rangoofdethe la (c)Usar Uselathe grapheninel part (b)b)topara determine the elrange función. ¿Cuál y con obtiene? u seof function. Whatesissuitsmáximo maximum andqué forvalor whatde value does ¿Cuál es suWhat mínimo con qué valor se obtiene? it occur? is itsy minimum and de foruwhat value of does it occur? d) Explicar por qué la magnitud de la resultante nunca es 0. (d) Explain why the de magnitude of the resultant is never 87. Tres de los vértices un paralelogramo son (1, 2), (3,0. 1) y 4). Hallar lasoftres posibilidades para 1, cuarto 2 , 3, vértice 1 , and (ver 8, 4la. 87. (8, Three vertices a parallelogram are el figura). Find the three possible fourth vertices (see figure). yy 66 55 44 33 22 11 (8, (8,4) 4) (1, (1,2) 2) (3, (3,1) 1) xx −4 −2 −1 − 4−3 − 3−2 −1 11 22 33 44 55 66 77 88 99 10 10 88. vectorestopara puntos deoftrisección del seg88. Usar Use vectors find encontrar the pointslos of trisection the line segment mento de recta con (1, 2) y (7, 5). 1, 2puntos 7, 5 . with endpoints and terminales Tensión de un cable En los ejercicios 90, usar la figura Cable Tension In Exercises 89 and 89 90,y use the figure to para determinar la tensión en cable cada supporting cable que sostiene la load. carga determine the tension in each the given dada. 89. 90. 89. 90. 2 in. 1 in. A A 50° 50° C C 3000 lb 3 000 libras 30° 30° 100 km/hr 100 km/h 100libras lb 100 b) de of la the resultante función de (b)Determinar Determine la themagnitud magnitude resultantcomo as a function of u. Usar de graficación para the representar la funUseuna a herramienta graphing utility to graph function for ción 0 para<0 2≤ .u < 2p. B B A 10 pulg 20 pulg A B B 24 in. 24 pulg C C 5000 lb 5 000 libras 91. Projectile Motion A gun with a muzzle velocity of 1200 feet 91. Movimiento un proyectil con the unahorizontal. velocidad en la per second isdefired at an angleUn of 6arma above Find boca de cañón 1 200 piescomponents por segundo a un ánguthe vertical anddehorizontal ofse thedispara velocity. de 6° Load sobre laTohorizontal. Encontrarcylindrical las componentes 92. lo Shared carry a 100-pound weight,horitwo zontal y vertical de la velocidad. workers lift on the ends of short ropes tied to an eyelet on the 92. Carga compartida Para llevar una pesa cilíndrica de 100 litop center of the cylinder. One rope makes a 20 angle away bras, los extremos de unas corfromdos the trabajadores vertical and sostienen the other makes a 30 angle (seesogas figure). tas a un rope’s aro en tension el centroif de parte superior cilindro. (a) atadas Find each thelaresultant force isdel vertical. Una soga forma un ángulo de 20° con la vertical y la otra forma (b) Find the vertical component of each worker’s force. un ángulo de 30° (ver la figura). a) Hallar la tensión de cada soga si la fuerza resultante es vertical. b) Hallar la componente vertical de la fuerza de cada trabajador. EE 900 km/hr 900 km/h 32° 32° Figura for para Figure 9292 45°45° Figura for para Figure 9393 Navegación AUnplane aviónisvuela dirección 302°. of Su 302 velocidad 93. Navigation flyingen with a bearing . Its con respecto al airetoesthe de 900 por hora. viento speed with respect air iskilómetros 900 kilometers per El hour. Thea la altitud del avión viene del suroeste hora wind at the plane’s altitude is froma 100 the kilómetros southwest por at 100 (ver la figura). es lafigure). verdadera dirección deldirection avión y cuál kilometers per ¿Cuál hour (see What is the true of es su velocidad respecto suelo? the plane, and what is its al speed with respect to the ground? 94. Navigation Navegación A Unplane aviónflies vuela velocidad constanteofde400 400 at aa una constant groundspeed millas per por hour hora hacia el este, al suelo, y se encuentra miles due east and respecto encounters a 50-mile-per-hour con unfrom viento 50 millas por del compass noroeste. wind thedenorthwest. Findhora the proveniente airspeed and Encontrarthat la velocidad al aire y el rumbo permitirán direction will allowrelativa the plane to maintain itsque groundspeed al avión mantener su velocidad respecto al suelo y su dirección and eastward direction. hacia el este. True or False? In Exercises 95 –100, determine whether the ¿Verdaderoisotrue falso? En los a 100, why determinar statement or false. If ejercicios it is false,95explain or give sianla afirmación esshows verdadera o falsa. Si es falsa, explicar por qué o example that it is false. dar un ejemplo que demuestre que es falsa. 95. If u and v have the same magnitude and direction, then u and 95. Si u y v tienen la misma magnitud y dirección, entonces u y v v are equivalent. son equivalentes. 96. If u is a unit vector in the direction of v, then v v u. 96. Si u es un vector unitario en la dirección de v, entonces v 5 i v i u. 2 2 97. If is a unit vector, then u ai bj b 1. a 2 97. Si u 5 ai 1 bj es un vector unitario, entonces a 1 b 2 5 1. 98. a b. 2b. 98. If Si vv 5 ai entonces ai 1 bj bj 5 0, 0, then a5 a i i abj 2a.!2 a. 99. If Si aa 5 b, entonces b, then i 1 bj i 5 v have lathemisma 100. If same magnitud magnitudepero but direcciones opposite directions, Si uu and y v tienen opuestas, u uv 1 v0.5 0. then entonces 101. Demostrar que u 5 (cos q )i 2 (sen q )j y v 5 (sen q )i 1 (cos q )j cos i sen j and v sen i cos j 101. Prove that u son vectores unitarios para todo ángulo q . are unit vectors for any angle . 102. Geometría Usando vectores, demostrar que el segmento de 102. Geometry Using vectors,medios prove that the lados line segment joining recta que une los puntos de dos de un triángulo the midpoints of two sides of a triangle is parallel to, and es paralelo y mide la mitad de longitud, del tercer lado. onehalf the length of, the third side. 103. Geometría Usando vectores, demostrar que las diagonales de 103. Geometry Usingsevectors, that the diagonals of a un paralelogramo cortan aprove la mitad. parallelogram bisect each other. 104. Demostrar que el vector w 5 i u i v 1 i v i u corta a la mitad u v v u bisects the angle 104. Prove thatentre the uvector el ángulo y v. w between and u v. 105. Considerar el vector u 5 kx, yl. Describir el conjunto de todos 105. Consider the set of all points . Describe los puntosthe sx,vector yd talesu que ix,uyi 5 5. 5. x, y such that u PPreparación U T N A M E X A Mdel CHA LLENGE examen Putman 106. A coast artillery gun can fire at any angle of elevation 106. Un arma 0de and artillería disparada cualquier between fixed puede verticalserplane. If air aresistance 90 indea costa ángulo de elevación entre 0° y 90° en un plano vertical is neglected and the muzzle velocity is constant vfijo. 0 , Si se desprecia la resistencia del aire y la velocidad en la boca determine the set H of points in the plane and above the de cañón eswhich constante s5hit. v0d, determinar el conjunto H de horizontal can be puntos en el plano y sobre la horizontal que puede ser golThis problem was composed by the Committee on the Putnam Prize Competition. peado. © The Mathematical Association of America. All rights reserved. Este problema fue preparado por el Committee on the Putnam Prize Competition. © The Mathematical Association of America. Todos los derechos reservados. Larson-11-02.qxd 3/12/09 17:05 Page 775 SECCIÓN 11.2 Coordenadas y vectores en el espacio 11.2 Coordenadas y vectores en el espacio n n n Entender el sistema de coordenadas rectangulares tridimensional. Analizar vectores en el espacio. Utilizar vectores tridimensionales para resolver problemas de la vida real. Coordenadas en el espacio z Hasta este punto del texto ha interesado principalmente el sistema de coordenadas bidimensional. En buena parte de lo que resta del estudio del cálculo se emplea el sistema de coordenadas tridimensional. Antes de extender el concepto de vector a tres dimensiones, se debe poder identificar puntos en el sistema de coordenadas tridimensional. Se puede construir este sistema trazando en el origen un eje z perpendicular al eje x y al eje y. La figura 11.14 muestra la porción positiva de cada eje de coordenadas. Tomados por pares, los ejes determinan tres planos coordenados: el plano xy, el plano xz y el plano yz. Estos tres planos coordenados dividen el espacio tridimensional en ocho octantes. El primer octante es en el que todas las coordenadas son positivas. En este sistema tridimensional, un punto P en el espacio está determinado por una terna ordenada (x, y, z) donde x, y y z son: Plano yz Plano xz y Plano xy x Sistema de coordenadas tridimensional Figura 11.14 x 5 distancia dirigida que va del plano yz a P y 5 distancia dirigida que va del plano xz a P z 5 distancia dirigida que va del plano xy a P En la figura 11.15 se muestran varios puntos. z 6 5 4 (2, −5, 3) 3 (−2, 5, 4) −6 −5 −4 −3 2 −8 1 −4 −2 3 4 (1, 6, 0) 8 y 5 6 (3, 3, −2) x Los puntos en el sistema de coordenadas tridimensional se representan por medio de ternas ordenadas z z Figura 11.15 y x x y Sistema dextrógiro Sistema levógiro Figura 11.16 Un sistema de coordenadas tridimensional puede tener orientación levógira o dextrógira. Para determinar la orientación de un sistema, se puede imaginar de pie en el origen, con los brazos apuntando en dirección de los ejes x y y positivo y el eje z apuntando hacia arriba, como se muestra en la figura 11.16. El sistema es dextrógiro o levógiro dependiendo de qué mano queda apuntando a lo largo del eje x. En este texto, se trabaja exclusivamente con el sistema dextrógiro. 775 Larson-11-02.qxd 776 3/12/09 17:05 CAPÍTULO 11 Page 776 Vectores y la geometría del espacio z (x2, y2, z2) Q d z2 − z1 P x y (x1, y1, z1) (x2, y2, z1) (x2 − x1)2 + (y2 − y1)2 Muchas de las fórmulas establecidas para el sistema de coordenadas bidimensional pueden extenderse a tres dimensiones. Por ejemplo, para encontrar la distancia entre dos puntos en el espacio, se usa dos veces el teorema pitagórico, como se muestra en la figura 11.17. Haciendo esto, se obtiene la fórmula de la distancia entre los puntos sx1, y1, z1d y sx2, y2, z 2 d. d 5 !sx2 2 x1d2 1 s y2 2 y1d2 1 sz2 2 z1d2 Fórmula de la distancia. Distancia entre dos puntos en el espacio EJEMPLO 1 Distancia entre dos puntos en el espacio La distancia entre los puntos s2, 21, 3d y s1, 0, 22d es Figura 11.17 d 5 !s1 2 2d2 1 s0 1 1d2 1 s22 2 3d2 Fórmula de la distancia. 5 !1 1 1 1 25 5 !27 5 3!3. Una esfera con centro en sx0 , y0 , z0d y radio r está definida como el conjunto de todos los puntos sx, y, zd tales que la distancia entre sx, y, zd y sx0 , y0 , z0d es r. Se puede usar la fórmula de la distancia para encontrar la ecuación canónica o estándar de una esfera de radio r, con centro en sx0 , y0 , z0d. Si sx, y, zd es un punto arbitrario en la esfera, la ecuación de la esfera es z (x, y, z) r sx 2 x0d2 1 s y 2 y0d2 1 sz 2 z 0 d2 5 r 2 (x0, y0, z0) y Ecuación de la esfera. como se muestra en la figura 11.18. El punto medio del segmento de recta que une a los puntos sx1, y1, z1d y sx2, y2, z2d tiene coordenadas x Figura 11.18 1 x1 1 x2 y1 1 y2 z1 1 z2 , , . 2 2 2 2 Regla del punto medio. Ecuación de una esfera EJEMPLO 2 Hallar la ecuación canónica o estándar de la esfera que tiene los puntos (5, –2, 3) y (0, 4, –3) como extremos de un diámetro. Solución Según la regla del punto medio, el centro de la esfera es 15 12 0, 2221 4, 3 22 32 5 152, 1, 02. Regla del punto medio. Según la fórmula de la distancia, el radio es r5 !10 2 252 2 1 s4 2 1d2 1 s23 2 0d2 5 !974 5 !97 2 . Por consiguiente, la ecuación canónica o estándar de la esfera es 1 x2 5 2 2 2 1 s y 2 1d2 1 z2 5 97 . 4 Ecuación de la esfera. Larson-11-02.qxd 3/12/09 17:05 Page 777 SECCIÓN 11.2 Coordenadas y vectores en el espacio 777 Vectores en el espacio En el espacio los vectores se denotan mediante ternas ordenadas v 5 kv1, v2, v3l. El vector cero se denota por 0 5 k0, 0, 0l. Usando los vectores unitarios i 5 k1, 0, 0l, j 5 k0, 1, 0l,y k 5 k0, 0, 1l en la dirección del eje positivo z, la notación empleando los vectores unitarios canónicos o estándar para v es z ⟨v1, v2, v3⟩ v ⟨0, 0, 1⟩ v 5 v1i 1 v2 j 1 v3k k j ⟨0, 1, 0⟩ i y ⟨1, 0, 0⟩ x como se muestra en la figura 11.19. Si v se representa por el segmento de recta dirigido de Ps p1, p2, p3d a Qsq1, q2, q3d, como se muestra en la figura 11.20, las componentes de v se obtienen restando las coordenadas del punto inicial de las coordenadas del punto final, como sigue v 5 kv1, v2, v3 l 5 kq1 2 p1, q2 2 p2, q3 2 p3 l Los vectores unitarios canónicos o estándar en el espacio Figura 11.19 VECTORES EN EL ESPACIO Sean u 5 ku1, u2, u3 l y v 5 kv1, v2, v3 l vectores en el espacio y sea c un escalar. z Q(q1, q2, q3) P( p1, p2, p3) 1. Igualdad de vectores: u 5 v si y sólo si u1 5 v1, u2 5 v2,y u3 5 v3. 2. Expresión mediante las componentes: Si v se representa por el segmento de recta dirigido de Ps p1, p2, p3d a Qsq1, q2, q3d, entonces v v 5 kv1, v2, v3 l 5 kq1 2 p1, q2 2 p2, q3 2 p3 l. y 3. Longitud: ivi 5 !v12 1 v22 1 v32 x v = ⟨q1 − p1, q2 − p2, q3 − p3⟩ 1 2 v 1 5 kv1, v2, v3l, v Þ 0 ivi ivi 5. Suma de vectores: v 1 u 5 kv1 1 u1, v2 1 u2, v3 1 u3 l 6. Multiplicación por un escalar: cv 5 kcv1, cv2, cv3 l 4. Vector unitario en la dirección de v: Figura 11.20 NOTA Las propiedades de la suma de vectores y de la multiplicación por un escalar dadas en el teorema 11.1 son también válidas para vectores en el espacio. n EJEMPLO 3 Hallar las componentes de un vector en el espacio Hallar las componentes y la longitud del vector v que tiene punto inicial s22, 3, 1d y punto final s0, 24, 4d. Después, hallar un vector unitario en la dirección de v. Solución El vector v dado mediante sus componentes es v 5 kq1 2 p1, q2 2 p2, q3 2 p3l 5 k0 2 s22d, 24 2 3, 4 2 1l 5 k2, 27, 3l lo cual implica que su longitud es ivi 5 !22 1 s27d2 1 32 5 !62. El vector unitario en la dirección de v es u 冬 冭 v 1 2 7 3 具2, 7, 3典 , , . 储v储 冪62 冪62 冪62 冪62 Larson-11-02.qxd 778 3/12/09 17:05 CAPÍTULO 11 Page 778 Vectores y la geometría del espacio y Recordar que en la definición de la multiplicación por un escalar se vio que múltiplos escalares positivos de un vector v distinto de cero tienen la misma dirección que v, mientras que múltiplos negativos tienen dirección opuesta a la de v. En general, dos vectores distintos de cero u y v son paralelos si existe algún escalar c tal que u 5 cv. u = 2v w = −v u DEFINICIÓN DE VECTORES PARALELOS Dos vectores distintos de cero u y v son paralelos si hay algún escalar c tal que u 5 cv. v x w Por ejemplo, en la figura 11.21, los vectores u, v y w son paralelos porque u 5 2v y w 5 2v. Vectores paralelos Figura 11.21 EJEMPLO 4 Vectores paralelos El vector w tiene punto inicial s2, 21, 3d y punto final s24, 7, 5d. ¿Cuál de los vectores siguientes es paralelo a w? a) u 5 k3, 24, 21l b) v 5 k12, 216, 4l Solución Empezar expresando w mediante sus componentes. w 5 k24 2 2, 7 2 s21d, 5 2 3l 5 k26, 8, 2l a) Como u 5 k3, 24, 21l 5 2 12 k26, 8, 2l 5 2 12 w, se puede concluir que u es paralelo a w. b) En este caso, se quiere encontrar un escalar c tal que k12, 216, 4l 5 ck26, 8, 2l. 12 5 26c → c 5 22 216 5 8c → c 5 22 45 2 2c → c 5 Como no hay un c para el cual la ecuación tenga solución, los vectores no son paralelos. z (1, − 2, 3) EJEMPLO 5 P 4 2 Determinar si los puntos Ps1, 22, 3d, Qs2, 1, 0d,y Rs4, 7, 26d son colineales. (2, 1, 0) Q 2 \ 4 8 8 \ Solución Los componentes de PQ y PR son 6 6 x Uso de vectores para determinar puntos colineales y PQ 5 k2 2 1, 1 2 s22d, 0 2 3l 5 k1, 3, 23l \ y PR 5 k4 2 1, 7 2 s22d, 26 2 3l 5 k3, 9, 29l. \ (4, 7, − 6) R Los puntos P, Q y R están en la misma recta Figura 11.22 Estos dos vectores tienen un punto inicial común. Por tanto, P, Q y R están en la misma recta si y sólo si PQ y PR son paralelos. PQ y PR son paralelos ya que PR 5 3 PQ , como se muestra en la figura 11.22. \ \ \ \ \ \ Larson-11-02.qxd 3/12/09 17:05 Page 779 SECCIÓN 11.2 EJEMPLO 6 Coordenadas y vectores en el espacio 779 Notación empleando los vectores unitarios canónicos a) Expresar el vector v 5 4i 2 5k por medio de sus componentes. b) Hallar el punto final del vector v 5 7i 2 j 1 3k, dado que el punto inicial es Ps22, 3, 5d. Solución a) Como falta j, su componente es 0 y v 5 4i 2 5k 5 k4, 0, 25l. b) Se necesita encontrar Qsq1, q2, q3d tal que v 5 PQ 5 7i 2 j 1 3k. Esto implica que q1 2 s22d 5 7, q2 2 3 5 21,y q3 2 5 5 3. La solución de estas tres ecuaciones es q1 5 5, q2 5 2, y q3 5 8. Por tanto, Q es (5, 2, 8). \ Aplicación EJEMPLO 7 z Una cámara de televisión de 120 libras está colocada en un trípode, como se muestra en la figura 11.23. Representar la fuerza ejercida en cada pata del trípode como un vector. P (0, 0, 4) ( Q3 − 3 , 1 , 0 2 2 Q1 (0, −1, 0) ) Solución Sean los vectores F1, F2,y F3 las fuerzas ejercidas en las tres patas. A partir de la figura 11.23, se puede determinar que las direcciones de F1, F2,y F3 son las siguientes. \ y Q2 ( 23 , 12 , 0) PQ 1 5 k0 2 0, 21 2 0, 0 2 4l 5 k0, 21, 24l \ PQ 2 5 x Figura 11.23 Magnitud de una fuerza \ 7!23 2 0, 12 2 0, 0 2 48 5 7!23, 12, 248 7 PQ 3 5 2 !3 2 2 0, 8 7 8 !3 1 1 2 0, 0 2 4 5 2 , , 24 2 2 2 Como cada pata tiene la misma longitud, y la fuerza total se distribuye igualmente entre las tres patas, se sabe que iF1 i 5 iF2 i 5 iF3 i. Por tanto, existe una constante c tal que 7!23, 12, 248, F1 5 ck0, 21, 24l, F2 5 c y 7 F3 5 c 2 !3 1 2 8 , , 24 . 2 Sea la fuerza total ejercida por el objeto la dada por F 具0, 0, 120典. Entonces, usando el hecho que F 5 F1 1 F2 1 F3 se puede concluir que F1, F2,y F3 tienen todas una componente vertical de 240. Esto implica que cs24d 5 240 y c 5 10. Por tanto, las fuerzas ejercidas sobre las patas pueden representarse por F1 5 k0, 210, 240l F2 5 k 5!3, 5, 240l F3 5 k 25!3, 5, 240l. Larson-11-02.qxd 3/12/09 17:05 Page 780 1053714_1102.qxp 10/27/08 10/27/08 10:38 10:38 AM AM Page Page 780 780 1053714_1102.qxp 1053714_1102.qxp 10/27/08 10/27/08 10:38 10:38 AM AM Page Page 780 780 1053714_1102.qxp 780 CAPÍTULO 11 780 780 780 Chapter 11 11 Chapter Chapter 11 Vectores y la geometría del espacio Vectors and and the the Geometry Geometry of of Space Space Vectors Vectors and the Geometry of Space Ejercicios 11.2 11.2 Exercises 11.2 Exercises See www.CalcChat.com www.CalcChat.com for for worked-out worked-out solutions solutions to to odd-numbered odd-numbered exercises. exercises. See See www.CalcChat.com www.CalcChat.com for for worked-out worked-out solutions solutions to to odd-numbered odd-numbered exercises. exercises. See En los ejercicios 1 y 2, aproximar las coordenadas de los puntos. In Exercises Exercises 11 and and 2, 2, approximate approximate the the coordinates coordinates of of the the points. points. In z of the points. In1.Exercises 1 zand 2, approximate2.the coordinates B zz 1. 2. 1. 2. B 5 B 5 zz 1. 2. B B 3 4 −2 2 3 x A 4 y B 4 55 54 5 −4 3 4 −3 − 4 4 2 4 33−2 − 3− 4 344 332 − 2−−− 2 −−2−33 −2 22 −−22 −2 −2 1 2 y −2 A −2 11 22 yy x A 11 22 yy A xx A A xx En ejercicios a 6, the representar en el mismo sisIn los Exercises 3– 6, 6,3 plot plot points on on los the puntos same three-dimensional three-dimensional In Exercises 3– the points the same tema de coordenadas tridimensional. In Exercises system. 3– 6, plot the points on the same three-dimensional coordinate coordinate system. coordinate system. 3.3. a)(a)s2,共2,1,1,3d3兲 2,2, 1d b)(b)s21, 1, 3. (a) 共2, 1, 3兲 (b) 共共1, 2, 11兲兲 3. a) (a) s共3,2,22, (b) s共321, 1, 3兲5d 2, 1d 兲 3 , 4, 22 4. b) 3, 2, 2, 55兲兲 4, 2 2 4. (a) (a) 共共3, (b) 共共32,, 4, 4. (b) 兲兲 332 共 3, 2, 5 兲 , 4, 2 4. (a) (b) 2 d s 5, 22, 22 d 兲 5.5. a)(a)s5,共5,22, b) 共 兲 2 2 2, 22兲兲 5, 2, 2, 2 2 (b) 共共5, 兲 5. (a) 共5, 2, (b) 2d兲 5,0,2, 2兲 共 5. a) (a) s共0,5,4,2, (b) s4, 25 5 d 6. b) 共 0, 4, 5 兲 共 4, 0, 5 兲 6. (a) (b) 6. (a) 共0, 4, 5兲 (b) 共4, 0, 5兲 6. (a) 共0, 4, 5兲 (b) 共4, 0, 5兲 En ejercicios 7 afind 10, hallar las coordenadas del punto. In los Exercises 7–10, the coordinates coordinates of the the point. point. In Exercises 7–10, find the of In Exercises 7–10, find the coordinates of the point. punto detrás 7.7. ElThe yz-plano pointseis islocaliza located tres threeunidades units behind behind thedel plane, yz, fourcuatro units yz7. The point located three units the plane, four units aislaof derecha del units plano xz y units cinco unidades arriba del yz7. unidades The point located three behind the above plane, four units xzxyto the right the plane, and five the plane. to the right of the xz-plane, and five units above the xy-plane. plano to the xy. right of the xz-plane, and five units above the xy-plane. yz-plane, 8. The The point point is is located located seven seven units units in in front front of of the the yzplane, two two 8. 8. punto seisleft localiza siete unidades delante del yzplano yz,plane. dos 8. El The point located unitsand in one front of below the plane, two xz-plane, xyunits to the the of the theseven plane, unit the xzxyunits to left of and one unit below the plane. unidades la izquierda del plano xz yunit unabelow unidad del plane. xy-plane. units to thea left of the xz-plane, and one thedebajo x-axis, 9. The The point point is is located located on on the the xaxis, 12 12 units units in in front front of of the the 9. xy. is located x9. plano The point on the axis, 12 units in front of the point is located the front of the yzplane. yz-plane. 9. El plane.se localiza en el eje x, 12 unidades delante del plano yz. yz-punto plane. yz-plane, 10. The The point point is is located located in in the the yzplane, three three units units to to the the right right of of 10. 10. El punto seis en plano yz, tres unidades derecha 10. The The point islocaliza located inel the plane, three unitsato tolathe the right del of yzpoint located in the plane, three units right of xzxythe plane, and two units above the plane. the xz-plane, and two units above the xy-plane. plano y dosand unidades arriba delthe plano xy. xy-plane. the xz-xz plane, and two units units above the plane. the plane, two above z11. Think About It What is the coordinate of any any point point in in the the 11. Think About It What is the z-coordinate of 11. pensar es is coordenada z de puntoin el 11. Para Think About It It¿Cuál What islathe the coordinate oftodo any point point inenthe the z-coordinate Think About What of any xyplane? xy-plane? plano xy? xy-plane? plane? x-coordinate 12. Think Think About About It It What What is is the the xcoordinate of of any any point point in in the the 12. 12. pensar es is coordenada x de puntoin el 12. Para Think About It It¿Cuál What islathe the coordinate oftodo any point point inenthe the x-coordinate Think About What of any yz-plane? plane? yzplano yz? plane? yz-plane? x, y, y, zz冈冈 In Exercises Exercises 13–24, 13–24, determine determine the the location location of of aa point point 冇冇x, In In Exercises 13–24, determine the location location of aa point point 冇 x,punto y, z冈 In Exercises 13–24, determine the of En los ejercicios 13 a 24, determinar la localización de un that satisfies the condition(s). that satisfies the condition(s). thaty,satisfies satisfies the condition(s). condition(s). that the (x, z) que satisfaga la(s) condición(es). 66 22 13. zz 14. yy 13. 14. 13. z 6 14. y 2 55 13. 14. z 2 x 3 15. 16. 15. x 3 16. z 5 15. x 3 16. z 5222 15. 16. < 0 0 > 0 0 17. yy < 18. xx > 17. 18. 17. y < 0 18. x > 0 17. 18. > 4 4 19. yy 20. xx > 33 19. 20. y 3 19. 20. x > 4 19. 20. xy < 44 xy > > 0, 0, zz 3 3 < 0, 0, zz 21. xy 22. xy 21. 22. 21. xy > 0, z 3 22. xy < 0, z 4 21. 22. xyz < 0 > 0 xyz 23. 24. 23. xyz < 0 24. xyz > 0 23. xyz < 0 24. xyz > 0 23. 24. In Exercises Exercises 25–28, 25–28, find find the the distance distance between between the the points. points. In In Exercises Exercises 25–28, find the distance between the los points. In 25–28, distance between the points. En los ejercicios 25 afind 28, the hallar la distancia entre puntos. 0, 0, 0, 00兲兲,, 共共4, 4, 2, 2, 77兲兲 25. 共共0, 25. 25. 共0, 0, 0兲, 共4, 2, 7兲 25. 2, 3, 3, 22兲兲,, 共共2, 2, 5, 5, 2 2兲兲 26. 共共2, 26. 26. 共2, 3, 2兲, 共2, 5, 2兲 26. 1, 2, 2, 44兲兲,, 共共6, 6, 2, 2, 2 2兲兲 27. 共共1, 27. 27. 共1, 2, 4兲, 共6, 2, 2兲 27. 共 2, 2, 3 兲 , 4, 5, 6 兲 共 28. 28. 共2, 2, 3兲, 共4, 5, 6兲 28. 共2, 2, 3兲, 共4, 5, 6兲 28. ⱍⱍ ⱍ ⱍⱍ ⱍ ⱍⱍ ⱍ ⱍⱍ ⱍ En los ejercicios 29 a 32, hallar las longitudes de los lados del In Exercises Exercises 29–32, find que the lengths lengths of the the sides of of the thesi triangle triangle In find the of sides triángulo con29–32, los vértices se indican, y determinar el triánIn Exercises 29–32,vertices, find the the and lengths of the the sides sides of the the triangle In Exercises 29–32, find lengths of of triangle with the indicated determine whether the triangle with es theunindicated and determine whether the otriangle gulo triángulovertices, rectángulo, un triángulo isósceles, ninguwith the indicated indicated vertices, and triangle, determine whether the triangle triangle with the vertices, and determine is aaderight right triangle, an isosceles isosceles orwhether neither. the is triangle, triangle, or neither. na ambas cosas.an is aa right right triangle, triangle, an an isosceles isosceles triangle, triangle, or or neither. neither. is 0, 0, 0, 44兲兲,, 共共2, 2, 6, 6, 77兲兲,, 共共6, 6, 4, 4, 8 8兲兲 29. 共共0, 29. 29. 共0, 0, 4兲, 共2, 6, 7兲, 共6, 4, 8兲 29. 3, 4, 4, 11兲兲,, 共共0, 0, 6, 6, 22兲兲,, 共共3, 3, 5, 5, 66兲兲 30. 共共3, 30. 30. 共3, 4, 1兲, 共0, 6, 2兲, 共3, 5, 6兲 30. 1, 0, 2 兲 , 共 1, 5, 3, 1, 1, 11兲兲 共 31. 31. 共1, 0, 2兲, 共1, 5, 22兲兲,, 共共3, 31. 共1, 0, 2兲, 共1, 5, 2兲, 共3, 1, 1兲 31. 4, 1, 1, 1 1兲兲,, 共共2, 2, 0, 0, 4 4兲兲,, 共共3, 3, 5, 5, 1 1兲兲 32. 共共4, 32. 32. 共4, 1, 1兲, 共2, 0, 4兲, 共3, 5, 1兲 32. 33. El triángulo del ejercicio 29 se cinco 33. Para Thinkpensar About It It The triangle triangle in Exercise Exercise 29 traslada is translated translated 33. Think About The in 29 is 33. Think Think About Itarriba Thea triangle triangle inDetermine Exercise 29 coordinates is translated translated 33. About It The in Exercise 29 is unidades hacia lo largo del eje z. Determinar las coorzfive units upward along the axis. the of five units upward along the z- axis. Determine the coordinates of five units upward alongtrasladado. the z- axis. axis. Determine Determine the the coordinates coordinates of of five upward along the denadas del triángulo the units translated triangle. the translated triangle. the translated translated triangle. triangle. the 34. El triángulo del in ejercicio 30 30 se is tres 34. Para Thinkpensar About It It The triangle triangle in Exercise 30 istraslada translated 34. Think About The Exercise translated 34. Think About It right Theaalong triangle in Exercise 30 is is the translated 34. Think About It The triangle in Exercise 30 translated unidades a la derecha lo largo del eje y. Determinar las coorythree units to the the axis. Determine coordithree units to the right along the y- axis. Determine the coordithree units totriángulo the right righttrasladado. along the y- axis. axis. Determine Determine the the coordicoordithree to the along the denadas natesunits of del the translated triangle. nates of the translated triangle. nates of of the the translated translated triangle. triangle. nates En los ejercicios 35 y 36, 36, find hallar coordenadas medio In Exercises Exercises 35 and and thelascoordinates coordinates of del the punto midpoint of In 35 36, find the of the midpoint of del segmento deand recta une los puntos. of In Exercises 35 and 36,que find the coordinates of the the midpoint midpoint of of In Exercises 35 36, find the coordinates the line segment joining the points. the line segment joining the points. the line line segment segment joining joining the the points. points. the 35. 36. 5, 29, 9, 777d兲兲,,, s共共22, 2, 3, 3, 333d兲兲 4, 0, 0, 26 6d兲兲,,, s共共8, 8, 8, 8, 20 20d兲兲 35. s共共5, 36. s共共4, 5, 9, 2, 3, 4, 0, 6 8, 8, 20 35. 36. 35. 共5, 9, 7兲, 共2, 3, 3兲 36. 共4, 0, 6兲, 共8, 8, 20兲 35. 36. En los ejercicios 40, hallar la ecuación estándar desphere. la esfera. In Exercises Exercises 37–37 40,afind find the standard standard equation of the the In 37– 40, the equation of sphere. In Exercises Exercises 37– 37– 40, 40, find find the the standard standard equation equation of of the the sphere. sphere. In 37. 38. 0, 2, 2, 555d兲兲 4, 21, 1, 111d兲兲 37. Centro: Center: s共共0, 38. Centro: Center: s共共4, 0, 2, 4, 1, 37. Center: 38. Center: 37. Center: Center: 38. Center: Center: 共4, 1, 1兲 共0, 2, 5兲 37. 38. Radio: Radio: Radius:2 22 Radius:5 55 Radius: Radius: Radius: Radius: Radius: 22 Radius: 55 39. Puntos terminales de un diámetro: (2, 0, 0), 2, 0, 0, 00兲兲,, 共共0, 0, 6, 6, 00兲兲 (0, 6, 0) 39. Endpoints Endpoints of of aa diameter: diameter: 共共2, 39. 39. Endpoints of aa diameter: diameter: 共2, to 0, 兲, 共yz0, yz 6, 0兲 39. Endpoints of 40. tangente al 0the plano 3,2,2, 2,4), 40. Centro: Center: (23, tangent to plane 共共3, 44兲兲,, tangent 40. Center: the yzplane 40. Center: Center: 共3, 2, 4兲, tangent tangent to to the the yz- plane plane 40. En los ejercicios 41 a 44, completar el cuadrado para dar la In Exercises Exercises 41– 41– 44, 44, complete complete the the square square to to write write the the equation equation of of In ecuación de 41– la esfera en forma canónica o estándar. Hallarofel In Exercises 44, complete complete the square to write write theradius. equation In Exercises 41– 44, square to the equation of the sphere in in standard form.the Find the center center and the sphere standard form. Find the and radius. centro y el in radio. the sphere standard form. form. Find Find the the center center and and radius. radius. the sphere in standard 2 y 2 z 2 2x 6y 8z 1 0 x 41. 2 2 41. x22 y22 z222 2x 6y 8z 1 0 41. x 2 y 2 z 2 2x 6y 8z 1 0 41. yy2 zz2 9x 9x 2y 2y 10z 10z 19 19 00 42. xx2 42. 42. x22 y22 2z22 9x 2y 10z 19 0 42. 2 2 9x 9y 9z 6x 18y 1 43. 2 2 2 43. 9x 9y 9z 6x 18y 1 00 43. 9x222 9y222 9z222 6x 18y 1 0 43. 4y 4y 2 4z 4z 2 24x 24x 4y 4y 8z 8z 23 23 00 4x 2 44. 4x 44. 44. 4x 22 4y 22 4z 22 24x 4y 8z 23 0 44. In Exercises Exercises 45–48, 45–48, describe describe the the solid solid satisfying satisfying the the condition. condition. In En los ejercicios 45 adescribe 48, describir el sólido que satisface la conIn Exercises 45–48, the solid solid satisfying the condition. condition. In Exercises 45–48, describe the satisfying the 2 2 2 2 2 2 dición. x x y z 36 y z > 4 45. 46. 2 2 2 2 2 2 45. x y z 36 46. x y z > 4 45. x2222 y2222 z2222 36 46. x222 y222 z222 > 4 45. 46. yy 2 1 zz 2 ≤< < 36 4x 6y 6y 8z 8z46. 13 13 47. xx 2 1 45. x 1y 1z > 4 4x 47. 47. x 222 y 222 z 222 < 4x 6y 8z 13 47. z > 4x 6y 8z 13 48. 2 1 2 2 x y 1 < 4x 2 6y 1 8z 2 13 47. 48. x y z > 4x 6y 8z 13 48. x222 y222 z222 > 4x 6y 8z 13 48. 48. x 1 y 1 z > 24x 1 6y 2 8z 2 13 In Exercises Exercises 49–52, 49–52, (a) (a) find find the the component component form form of of the the vector vector v, v, In In Exercises 49–52, (a) find the component component formnotation, of the the vector v,v, In Exercises 49–52, (a) find the form of vector v, (b) write the vector using standard unit vector and (c) a) encontrar las componentes del vector En los ejercicios 49 a 52, (b) write the vector using standard unit vector notation, and (c) (b) writethe thevector vectorwith using standard unitatvector vector notation, and (c) (b) write the vector using unit notation, and (c) sketch itsstandard initial point thevector origin. b) escribir vector utilizando la notación unitario estánsketch theelvector with its initial point atdel the origin. sketch the vector with its initial point at the origin. sketch the vector with its initial point at the origin. dar y c) dibujar el vector con su punto inicial en el origen. 49. 50. 49. 50. 49. 50. 49. 50. z z 49. 50. 6 6 4 4 2 (4, 2, 1) 6 x (4, 0, 3) 2 (2, 4, 3) v 6 y v (0, 5, 1) 2 4 6 x 4 6 y Larson-11-02.qxd 26/2/10 14:09 Página 781 SECCIÓN 11.2 z 51. 6 2 4 4 4 y 6 2 4 (3, 3, 0) a) 具7, 6, 2典 v 4 (2, 3, 0) 6 b) 具14, 16, ⫺6典 y 6 x b) 4j ⫹ 2k 72. z tiene el punto inicial 共5, 4, 1兲 y el punto final 共⫺2, ⫺4, 4兲. (2, 3, 4) 2 v 2 6 a) ⫺6i ⫹ 8j ⫹ 4k 6 (0, 3, 3) 4 781 71. z tiene el punto inicial 共1, ⫺1, 3兲 y el punto final 共⫺2, 3, 5兲. z 52. Coordenadas y vectores en el espacio En los ejercicios 73 a 76, usar vectores para determinar si los puntos son colineales. x En los ejercicios 53 a 56, hallar las componentes y la magnitud del vector v, dados sus puntos inicial y final. Después hallar un vector unitario en la dirección de v. Punto inicial 53. 共3, 2, 0兲 54. 共4, ⫺5, 2兲 55. 共⫺4, 3, 1兲 56. 共1, ⫺2, 4兲 共4, 1, 6兲 共⫺1, 7, ⫺3兲 共⫺5, 3, 0兲 共2, 4, ⫺2兲 77. 共2, 9, 1兲, 共3, 11, 4兲, 共0, 10, 2兲, 共1, 12, 5兲 78. 共1, 1, 3兲, 共9, ⫺1, ⫺2兲, 共11, 2, ⫺9兲, 共3, 4, ⫺4兲 57. Punto inicial: 共⫺1, 2, 3兲 58. Punto inicial: 共2, ⫺1, ⫺2兲 Punto final: 共3, 3, 4兲 Punto final: 共⫺4, 3, 7兲 En los ejercicios 59 y 60, se dan el vector v y su punto inicial. Encontrar el punto final. 60. v ⫽ 具 1, 典 Punto inicial: 共0, 2, 52 兲 ⫺ 23, 12 En los ejercicios 61 y 62, hallar cada uno de los múltiplos escalares de v y representar su gráfica. b) ⫺v a) ⫺v b) 2v 3 c) 2v d) 0v 1 c) 2v 5 d) 2v En los ejercicios 63 a 68, encontrar el vector z, dado que u ⴝ 冬1, 2, 3冭, v ⴝ 冬2, 2, ⴚ1冭 y w ⴝ 具4, 0, ⴚ4典. 63. z ⫽ u ⫺ v 64. z ⫽ u ⫺ v ⫹ 2w 65. z ⫽ 2u ⫹ 4v ⫺ w 1 66. z ⫽ 5u ⫺ 3v ⫺ 2w 67. 2z ⫺ 3u ⫽ w 68. 2u ⫹ v ⫺ w ⫹ 3z ⫽ 0 En los ejercicios 69 a 72, determinar cuáles de los vectores son paralelos a z. Usar una herramienta de graficación para confirmar sus resultados. a) 具⫺6, ⫺4, 10典 4 10 b) 具 2, 3, ⫺ 3 典 En los ejercicios 79 a 84, hallar la longitud de v. 79. v ⫽ 具0, 0, 0典 80. v ⫽ 具1, 0, 3典 81. v ⫽ 3j ⫺ 5k 82. v ⫽ 2i ⫹ 5j ⫺ k 83. v ⫽ i ⫺ 2j ⫺ 3k 84. v ⫽ ⫺4i ⫹ 3j ⫹ 7k En los ejercicios 85 a 88, hallar un vector unitario a) en la dirección de v y b) en la dirección opuesta a u. 85. v ⫽ 具2, ⫺1, 2典 86. v ⫽ 具6, 0, 8典 87. v ⫽ 具3, 2, ⫺5典 88. v ⫽ 具8, 0, 0典 89. Programación Se dan las componentes de los vectores u y v. Escribir un programa para una herramienta de graficación donde el resultado es a) las componentes de u ⫹ v, b) 储 u ⫹ v 储, c) 储 u 储, y d) 储 v 储. e) Ejecutar el programa para los vectores u ⫽ 具⫺1, 3, 4典 y v ⫽ 具5, 4.5, ⫺6典. 62. v ⫽ 具2, ⫺2, 1典 a) 2v 69. z ⫽ 具3, 2, ⫺5典 75. 共1, 2, 4兲, 共2, 5, 0兲, 共0, 1, 5兲 En los ejercicios 77 y 78, usar vectores para demostrar que los puntos son vértices de un paralelogramo. En los ejercicios 57 y 58 se indican los puntos inicial y final de un vector v. a) Dibujar el segmento de recta dirigido, b) encontrar las componentes del vector, c) escribir el vector usando la notación del vector unitario estándar y d) dibujar el vector con su punto inicial en el origen. 61. v ⫽ 具1, 2, 2典 74. 共4, ⫺2, 7兲, 共⫺2, 0, 3兲, 共7, ⫺3, 9兲 76. 共0, 0, 0兲, 共1, 3, ⫺2兲, 共2, ⫺6, 4兲 Punto final 59. v ⫽ 具3, ⫺5, 6典 Punto inicial: 共0, 6, 2兲 73. 共0, ⫺2, ⫺5兲, 共3, 4, 4兲, 共2, 2, 1兲 Para discusión 90. Considerar dos vectores distintos de cero u y v, y sean s y t números reales. Describir la figura geométrica generada por los puntos finales de los tres vectores tv, u + tv y su + tv. En los ejercicios 91 y 92, determinar los valores de c que satisfacen la ecuación. Sea u ⴝ i ⴙ 2 j ⴙ 3k y v ⴝ 2i ⴙ 2 j ⴚ k. 91. 储 cv 储 ⫽ 7 En los ejercicios 93 a 96, encontrar el vector v con la magnitud dada y en dirección de u. 1 2 3 70. z ⫽ 2i ⫺ 3j ⫹ 4k a) 6i ⫺ 4j ⫹ 9k 4 3 b) ⫺i ⫹ 3j ⫺ 2k c) 具6, 4, 10典 c) 12i ⫹ 9k d) 具1, ⫺4, 2典 3 9 d) 4i ⫺ j ⫹ 8k 92. 储 cu 储 ⫽ 4 Magnitud Dirección 93. 10 u ⫽ 具0, 3, 3典 94. 3 u ⫽ 具1, 1, 1典 3 2 u ⫽ 具2, ⫺2, 1典 96. 7 u ⫽ 具⫺4, 6, 2典 95. Larson-11-02.qxd 782 26/2/10 14:10 CAPÍTULO 11 Página 782 Vectores y la geometría del espacio En los ejercicios 97 y 98, dibujar el vector v y dar sus componentes. 101. Sean u ⫽ i ⫹ j, v ⫽ j ⫹ k, y w ⫽ au ⫹ bv. a) Dibujar u y v. b) Si w ⫽ 0, demostrar que tanto a como b deben ser cero. c) Hallar a y b tales que w ⫽ i ⫹ 2j ⫹ k. d) Probar que ninguna elección de a y b da w ⫽ i ⫹ 2j ⫹ 3k. 105. Dar la ecuación canónica o estándar de una esfera de radio r, centrada en 共x0, y0, z0兲. 106. Dar la definición de vectores paralelos. 107. Sean A, B y C los vértices de un triángulo. Encontrar AB ⫹ BC ⫹ CA . \ \ \ 108. Sean r ⫽ 具x, y, z典 y r0 ⫽ 具1, 1, 1典. Describir el conjunto de todos los puntos 共x, y, z兲 tales que 储r ⫺ r0 储 ⫽ 2. 109. Análisis numérico, gráfico y analítico Los focos en un auditorio son discos de 24 libras y 18 pulgadas de radio. Cada disco está sostenido por tres cables igualmente espaciados de L pulgadas de longitud (ver la figura). 45 50 110. Para pensar Suponer que cada cable en el ejercicio 109 tiene una longitud fija L ⫽ a, y que el radio de cada disco es r0 pulgadas. Hacer una conjetura acerca del límite lím lim T y jusr0 →a⫺ tificar la respuesta. 111. Diagonal de un cubo Hallar las componentes del vector unitario v en la dirección de la diagonal del cubo que se muestra en la figura. z z 100 v Desarrollo de conceptos 104. Dar la fórmula para la distancia entre los puntos 共x1, y1, z1兲 y 共x2, y2, z2兲. 40 e) Calcular la longitud mínima que debe tener cada cable, si un cable está diseñado para llevar una carga máxima de 10 libras. 102. Redacción Los puntos inicial y final del vector v son 共x1, y1, z1兲 y 共x, y, z兲. Describir el conjunto de todos los puntos 共x, y, z兲 tales que 储v储 ⫽ 4. 103. Un punto en el sistema de coordenadas tridimensional tiene las coordenadas 共x0, y0, z0兲. Describir qué mide cada una de las coordenadas. 35 d) Comprobar analíticamente las asíntotas obtenidas en el inciso c). En los ejercicios 99 y 100, usar vectores para encontrar el punto que se encuentra a dos tercios del camino de P a Q. Q共6, 8, 2兲 30 c) Representar en la herramienta de graficación el modelo del inciso a) y determinar las asíntotas de su gráfica. 98. v está en el plano xz, tiene magnitud 5 y forma un ángulo de 45° con el eje z positivo. 100. P共1, 2, 5兲, 25 T 97. v está en el plano yz, tiene magnitud 2 y forma un ángulo de 30° con el eje y positivo. 99. P共4, 3, 0兲, Q共1, ⫺3, 3兲 20 L −50 y x y ⏐⏐v⏐⏐ = 1 x Figura para 111 75 Figura para 112 112. Cable de sujeción El cable de sujeción de una torre de 100 pies tiene una tensión de 550 libras. Usar las distancias mostradas en la figura, y dar las componentes del vector F que represente la tensión del cable. 113. Soportes de cargas Hallar la tensión en cada uno de los cables de soporte mostrados en la figura si el peso de la caja es de 500 newtons. z 45 cm D C 70 cm B 65 cm C 60 cm y x 18 pies 115 cm A D A B 6 pies 8 pies 10 pies L Figura para 113 18 pulg a) Expresar la tensión T de cada cable en función de L. Determinar el dominio de la función. b) Usar una herramienta de graficación y la función del inciso a) para completar la tabla. Figura para 114 114. Construcción de edificios Un muro de hormigón es sostenido temporalmente en posición vertical por medio de cuerdas (ver la figura). Hallar la fuerza total ejercida sobre la clavija en posición A. Las tensiones en AB y AC son 420 libras y 650 libras. 115. Escribir una ecuación cuya gráfica conste del conjunto de puntos P共x, y, z兲 que distan el doble de A共0, ⫺1, 1兲 que de B共1, 2, 0兲. Larson-11-03.qxd 3/12/09 17:08 Page 783 SECCIÓN 11.3 El producto escalar de dos vectores 783 11.3 El producto escalar de dos vectores n n n n n Usar las propiedades del producto escalar de dos vectores. Hallar el ángulo entre dos vectores usando el producto escalar. Hallar los cosenos directores de un vector en el espacio. Hallar la proyección de un vector sobre otro vector. Usar los vectores para calcular el trabajo realizado por una fuerza constante. El producto escalar EXPLORACIÓN Interpretación de un producto escalar En la figura se muestran varios vectores en el círculo unidad. Hallar los productos escalares de varios pares de vectores. Después encontrar el ángulo entre cada par usado. Hacer una conjetura sobre la relación entre el producto escalar de dos vectores y el ángulo entre los vectores. 90° 120° Hasta ahora se han estudiado dos operaciones con vectores —la suma de vectores y el producto de un vector por un escalar— cada una de las cuales da como resultado otro vector. En esta sección se presenta una tercera operación con vectores, llamada el producto escalar. Este producto da como resultado un escalar, y no un vector. DEFINICIÓN DE PRODUCTO ESCALAR El producto escalar de u 5 ku 1, u 2 l y v 5 kv1, v2 l es u ? v 5 u 1v1 1 u 2v2. El producto escalar de u 5 ku 1, u 2, u 3 l y v 5 kv1, v2, v3 l es u ? v 5 u 1v1 1 u 2v2 1 u 3v3. 60° 30° 150° 180° 0° NOTA El producto escalar de dos vectores recibe este nombre debido a que da como resultado un escalar; también se le llama producto interno de los dos vectores. n TEOREMA 11.4 PROPIEDADES DEL PRODUCTO ESCALAR 210° 330° 240° Sean u, v y w vectores en el plano o en el espacio y sea c un escalar. 270° 300° 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. u?v5v?u u ? sv 1 wd 5 u ? v 1 u ? w csu ? vd 5 cu ? v 5 u ? cv 0?v50 v ? v 5 i vi 2 DEMOSTRACIÓN Propiedad conmutativa. Propiedad distributiva. Para demostrar la primera propiedad, sea u 5 ku 1, u 2, u 3 l y v 5 7v1, v2, v38. Entonces u ? v 5 u 1v1 1 u 2v2 1 u 3v3 5 v1u 1 1 v2u 2 1 v3u 3 5 v ? u. Para la quinta propiedad, sea v 5 kv1, v2, v3 l. Entonces v ? v 5 v12 1 v22 1 v32 5 s!v12 1 v22 1 v32 d 2 5 i vi2. Se dejan las demostraciones de las otras propiedades al lector. Larson-11-03.qxd 3/12/09 17:08 Page 784 1053714_1103.qxp 10/27/08 10:38 AM Page 784 784 CAPÍTULO 11 784 Chapter 11 Vectores y la geometría del espacio Vectors and the Geometry of Space EJEMPLO 1 Cálculo de productos escalares EXAMPLE 1 Finding Dot Products Dados u 5 k2, 22l, v 5 k5, 8l, y w 5 k24, 3l, encontrar Given a) b) suv 5vdk5, u uv 5 k2, 22l, w 8l, and w 5 k24, 3l, find each of the following. ? ? a. u v b. su ? 2vdw c) u ?? s2vd d) iwi c. u ? s2vd d. iwi 2 Solución Solution a) u ? vv 5 5 k2, k2, 22l 22l ? k5, k5, 8l 8l 5 5 22ss55dd 1 1 ss22 22ds ds88dd 5 5 26 26 a. u b) b. c) c. d) d. ? ? u ?? vvddw w5 5 26k24, 26k24, 3l 3l 5 5 k24, k24, 218l 218l ssu u ?? ss2v 2vdd 5 5 22ssu u ?? vvdd 5 5 22ss26 26dd 5 5 212 212 u iwi 5 w ? w 5 k24, 3l ? k24, 3l 5 s24ds24d 1 s3ds3d 5 25 iwi22 Teorema Theorem 11.4. 11.4 Teorema Theorem 11.4. 11.4 Sustituir por k24, . Substitutewk24, 3l for3lw. Definition of productescalar. Definición deldot producto Simplify. Simplificar. Notice that theelresult of part is a b) vector quantity, whereas the mientras results ofque thelos other Observar que resultado del(b) inciso es una cantidad vectorial, resultathreedeparts are scalar quantities. ■ dos los otros tres incisos son cantidades escalares. Angle Between Two Vectors Ángulo entre dos vectores The angle between two nonzero vectors is the angle u, 0 # u # p, between their El ángulo standard entre dosposition vectores distintos de ceroinesFigure el ángulo 0 ≤ next u ≤ theorem p, entre sus respective vectors, as shown 11.24.u, The respectivos vectores en posición canónica o estándar, como se muestra en la figura 11.24. shows how to find this angle using the dot product. (Note that the angle between the El siguiente teorema muestra cómo encontrar este ángulo usando el producto escalar. zero vector and another vector is not defined here.) (Observar que el ángulo entre el vector cero y otro vector no está definido aquí.) v−u v−u u u v θ θ Origin Origen The angle between two vectors El ángulo Figure 11.24entre dos vectores Figura 11.24 v THEOREM 11.5 ANGLE BETWEEN TWO VECTORS TEOREMA 11.5 ÁNGULO ENTRE DOS VECTORES If u is the angle between two nonzero vectors u and v, then Si u es el ángulo u entre ? v . dos vectores distintos de cero u y v, entonces cos u 5 iuui? ivi v cos u 5 . iui ivi PROOF Consider the triangle determined by vectors u, v, and v 2 u, as shown in Figure 11.24. By the Law of Cosines, you can write DEMOSTRACIÓN Considerar el triángulo determinado por los vectores u, v y v 2 u, como 2 iv 2 ui 5 figura i ui2 111.24. i vi2 Por 2 2iui ivi . se muestra en la la ley decos losucosenos, se puede escribir Using properties product, thecos leftu.side can be rewritten as 2 5 i ui2of1the 2 2 ivthe 2 ui i vidot 2iui ivi iv 2 ui2 5 sv 2 ud sv 2 ud Usando las propiedades del? producto escalar, el lado izquierdo puede reescribirse como 5 sv 2 ud ? v 2 sv 2 ud ? u iv 2 ui2 5 sv 2 ud ? sv 2 ud 5v?v2u?v2v?u1u?u 5 v2 ud2u sv iui 2 u2 d ? u ? v? 2v 1 2 2 5 sivi 5v?v2u?v2v?u1u?u and substitution back into the Law of Cosines yields 5 ivi2 2 2u ? v 1 iui 2 ivi2 2 2u ? v 1 i ui2 5 i ui2 1 i vi2 2 2i ui ivi cos u y sustituyendo en la ley dev los cosenosi vi se cos obtiene 22u u ? 5 22iui ivi2 2 2u ? v 1 i ui2 5 i ui u ?2 v1 i vi2 2 2i ui ivi cos u cos u 5 . ■ i ui iv ii vi cos u 22u ? v 5 22iui cos u 5 u?v . iui iv i Larson-11-03.qxd 3/12/09 17:08 Page 785 SECCIÓN 11.3 785 El producto escalar de dos vectores Si el ángulo entre dos vectores es conocido, reescribiendo el teorema 11.5 en la forma u ? v 5 i u i iv i cos u Forma alternativa del producto escalar. se obtiene una manera alternativa de calcular el producto escalar. De esta forma, se puede ver que como iu i y iv i siempre son positivos, u ? v y cos u siempre tendrán el mismo signo. La figura 11.25 muestra las orientaciones posibles de los dos vectores. u v<0 Dirección opuesta θ u u u v=0 u θ v v py 2 < u < p 2 1 < cos u < 0 u5p cos u 5 2 1 u v>0 u θ θ v u 5 py 2 cos u 5 0 Misma dirección u v 0 < u < py 2 0 < cos u < 1 v u50 cos u 5 1 Figura 11.25 De acuerdo con el teorema 11.5, se puede ver que dos vectores distintos de cero forman un ángulo recto si y sólo si su producto escalar es cero; entonces se dice que los dos vectores son ortogonales. DEFINICIÓN DE VECTORES ORTOGONALES Los vectores u y v son ortogonales si u ? v 5 0. NOTA Los términos “perpendicular”, “ortogonal” y “normal” significan esencialmente lo mismo: formar ángulos rectos. Sin embargo, es común decir que dos vectores son ortogonales, dos rectas o planos son perpendiculares y que un vector es normal a una recta o plano dado. n De esta definición se sigue que el vector cero es ortogonal a todo vector u, ya que 0 ? u 5 0. Si 0 ≤ u ≤ p, entonces se sabe que cos u 5 0 si y sólo si u 5 py2. Por tanto, se puede usar el teorema 11.5 para concluir que dos vectores distintos de cero son ortogonales si y sólo si el ángulo entre ellos es py2. EJEMPLO 2 Hallar el ángulo entre dos vectores Si u 5 k3, 21, 2l, v 5 k24, 0, 2l, w 5 k1, 21, 22l,y z 5 k2, 0, 21l, hallar el ángulo entre cada uno de los siguientes pares de vectores. a) u y v b) u y w c) v y z Solución u?v 212 1 0 1 4 28 24 5 5 5 iui ivi !14!20 ! ! ! 2 14 5 70 24 Como u ? v < 0, u 5 arccos < 2.069 radianes. !70 a) cos u 5 u?w 31124 0 5 5 50 iui iwi !14!6 !84 Como u ? w 5 0, u y w son ortogonales. Así, u 5 py2. b) cos u 5 v?z 28 1 0 2 2 210 5 5 5 21 ivi i zi !20!5 !100 Por consiguiente, u 5 p. Observar que v y z son paralelos, con v 5 22z. c) cos u 5 Larson-11-03.qxd 786 3/12/09 17:08 CAPÍTULO 11 Page 786 Vectores y la geometría del espacio Cosenos directores En el caso de un vector en el plano, se ha visto que es conveniente medir su dirección en términos del ángulo, medido en sentido contrario a las manecillas del reloj, desde el eje x positivo hasta el vector. En el espacio es más conveniente medir la dirección en términos de los ángulos entre el vector v distinto de cero y los tres vectores unitarios i, j y k, como se muestra en la figura 11.26. Los ángulos a, b y g son los ángulos de dirección de v, y cos a , cos b y cos g son los cosenos directores de v. Como z k γ v β j α y v ? i 5 iv i i i i cos a 5 i v i cos a v ? i 5 kv1, v2, v3l ? k1, 0, 0l 5 v1 y i x se sigue que cos a 5 v1yiv i. Mediante un razonamiento similar con los vectores unitarios j y k, se tiene Ángulos de dirección Figura 11.26 cos a 5 v1 iv i a es el ángulo entre v e i. cos b 5 v2 iv i b es el ángulo entre v y j. cos g 5 v3 . iv i g es el ángulo entre v y k. Por consiguiente, cualquier vector v distinto de cero en el espacio tiene la forma normalizada v v v v 5 1 i 1 2 j 1 3 k 5 cos a i 1 cos b j 1 cos g k ivi iv i iv i iv i y como vyiv i es un vector unitario, se sigue que cos 2 a 1 cos 2 b 1 cos 2 g 5 1. EJEMPLO 3 Cálculo de los ángulos de dirección Hallar los cosenos y los ángulos directores del vector v 5 2i 1 3j 1 4k, y mostrar que cos 2 a 1 cos 2 b 1 cos 2 g 5 1. Solución α = ángulo entre v e i β = ángulo entre v y j γ = ángulo entre v y k 4 3 γ v = 2i+ 3j + 4k 1 β α 3 4 1 cos 2 a 1 cos 2 b 1 cos 2 g 5 2 x 3 4 y 5 Ángulo entre v e i. b < 56.18 Ángulo entre v y j. g < 42.08 Ángulo entre v y k. 4 9 16 1 1 29 29 29 29 29 5 1. Ángulos de dirección de v Figura 11.27 a < 68.28 Además, la suma de los cuadrados de los cosenos directores es 1 2 v1 2 5 iv i !29 v 3 cos b 5 2 5 iv i !29 v 4 cos g 5 3 5 iv i !29 cos a 5 z 2 Como iv i 5 !22 1 32 1 42 5 !29, se puede escribir lo siguiente. Ver figura 11.27. Larson-11-03.qxd 3/12/09 17:08 Page 787 1053714_1103.qxp 10/27/08 10:38 AM Page 787 787 1053714_1103.qxp 10/27/08 10:38 AM Page 1053714_1103.qxp 10/27/08 10:38 AMPage Page 787 1053714_1103.qxp 10/27/08 10:38 AM 787 SECCIÓN 11.3 El producto escalar de dos vectores 787 11.3 The DotProduct TwoVectors Vectors 787 11.3 The Dot ofof Two 11.3 DotDot Product ofProduct Two Vectors 787 11.3 The The Product of Two Vectors 787 787 Proyecciones y componentes vectoriales w1 ww 11 w1 w1 w2 F ww w w 2gravedad 22 La fuerza debida a la empuja la FF2 F F lancha contra la rampa y hacia abajo por The force dueto togravity gravity pulls theboat boat The force pulls the The force due to due gravity pulls boat rampa Thela force due to gravity pulls the the boat against the ramp and down the ramp. against the ramp and down the ramp. against the ramp and down the ramp. against the ramp and down the ramp. Figura 11.28 Figure 11.28 Figure Figure 11.28 11.28 Figure 11.28 Ya se hanProjections visto aplicaciones en las que se suman dos vectores para obtener un vector resulProjections and Vector Components and Vector Components Projections and Components Projections andVector Vector Components tante. Muchas aplicaciones en la física o en la ingeniería plantean el problema inverso: You have already seen applications intwo which twoare vectors are added You have already seen incomponentes which two vectors are totoproduce aa have already seen applications in which two vectors are added to produce a YouYou have already seen applications in de which vectors added toadded produce aproduce descomponer un vector dado en laapplications suma dos vectoriales. El ejemplo físiresultant vector. Many applications in physics and engineering pose the reverse resultant vector. Many applications in physics and engineering pose the reverse resultant vector. Many applications in physics and engineering pose the reverse resultant vector. Many applications in physics and engineering pose the reverse co siguiente permitirá comprender la utilidad de este procedimiento. problem—decomposing given vector into the sum two vector components. The problem—decomposing aagiven vector into the sum two vector problem—decomposing a given vector into sum of two vector components. The The problem—decomposing a given vector into thethe sum of two vector components. The Considerar una lancha sobre una rampa inclinada, como seofof muestra en lacomponents. figura 11.28. following physical example enables you to see the usefulness of this procedure. following physical example enables you to see the usefulness of this procedure. following physical example enables you to see the usefulness of this procedure. following physical example enables you to see the usefulness of this procedure. La fuerza F debida a la gravedad empuja la lancha hacia abajo de la rampa y contra la Consider boat onan aninclined inclined ramp, shown Figure 11.28. The due Consider boat on asas inin Figure 11.28. The force Consider afuerzas, boat inclined ramp, as shown in Figure 11.28. The force Fforce dueFFdue Consider a boat onaaon an inclined ramp, asramp, shown inshown Figure 11.28. The force F due rampa. Estas dos wan 1 y w2, son ortogonales; se les llama las componentes vectoto gravity pulls the boat down the ramp and against the ramp. These two forces, w1 1 to gravity pulls the boat down the ramp and against the ramp. These two forces, w to gravity pulls the boat down the ramp and against the ramp. These two forces, w to gravity pulls the boat down the ramp and against the ramp. These two forces, w riales de F. 1 1 and w , are orthogonal—they are called the vector components of F. and w , are orthogonal—they are called the vector components of F. , are orthogonal—they are called the vector components of F. 2 andand w2,ware orthogonal—they are called the vector components of F. 2 2 Componentes vectoriales de F. F 5 w1 1 w 2 F1 ww w ww2Vector Vectorcomponents components F Vector F w1 w w components of Fof F ofofFF F components 2 Vector 2 121 Las fuerzas w1 y w2 ayudan a analizar el efecto de la gravedad sobre la lancha. Por ejemThe forces ww1and andyou w2you help you analyze the effect gravity on thehacia boat. Forexample, example, The w you analyze the effect ofofon gravity on the boat. For forces w1 and analyze the effect of gravity on boat. For example, 2help TheThe forces wforces analyze the effect ofque gravity the boat. For example, plo, lawwfuerza necesaria para impedir la lancha sethe deslice abajo por w 2 help 1 and 21help 1 representa w indicates the force necessary to keep the boat from rolling down the ramp, whereas w indicates the force necessary to keep the boat from rolling down the ramp, w indicates the force necessary to keep the boat from rolling down the ramp, whereas 1 w indicates the force necessary to keep the boat from rolling down the ramp, whereas 1 la 1rampa, mientras que w2 representa la fuerza que deben soportar los neumáticos. whereas 1 w indicates the force that the tires must withstand. w indicates the force that the tires must withstand. indicates the force that the tires must withstand. 2 w 2w indicates the force that the tires must withstand. 2 2 2 DEFINICIÓN DE PROYECCIÓN Y DE LASAND COMPONENTES VECTORIALES DEFINITIONS OFPROJECTION PROJECTION ANDVECTOR VECTOR COMPONENTS DEFINITIONS OF AND COMPONENTS DEFINITIONS PROJECTION VECTOR COMPONENTS DEFINITIONS OFOF PROJECTION AND VECTOR COMPONENTS uMoreover, 5 1w w , udonde w visy Sean yu vLet vectores de cero. Sea Moreover, es a1 1is Let andnonzero benonzero nonzero vectors. let2w where vbe ww wwhere w2w ,where uvuand vdistintos u ,2paralelo vectors. let 1w and be vectors. Moreover, let u w is ww LetLet uu and v be nonzero vectors. Moreover, let w u1 21, where 1 1 w2, 1 1 is1 wparallel v, es ortogonal a como se muestra en la figura 11.29. parallel and orthogonal shown Figure 11.29. w2 2isisorthogonal v,v,asas parallel toto totoshown inin Figure 2 parallel v, and is w orthogonal to as v, shown as in Figure 11.29.11.29. to vto, and wv2v,w is,and to v, inshown Figure 11.29. 2 orthogonal 2 uofof vonto 1.1.A1. laprojection proyección o la vectorial lo 1.le iscalled called theprojection projection orthe the vector component along w1llama uvonto w uor vvcomponente 1. the orvector vector component ofuofuaualong w is called the u onto or the component udealong 1is ww is1se called the projection of uofde onto ven the vector component of uofalong 11 largo de v, y se denota por w 5 proy u. and is denoted by v, w proj u. w proj u. and is denoted by v, and is denoted 1 proj 1 vu. v v v v, and is denoted by by w1 w 1 proj 1 vu. 5 uw 2 w 2.2.A2. se le llama la componente vectorial u uortogonal 2. w is called the vector component uorthogonal orthogonal u w u w 2. is called the vector component ofof 2 1 u w ww2 w is called the vector component of of u orthogonal to to v. av.v.totov.v. u w is called the vector component udeorthogonal 22 1 1 11 2 2 1 θ es agudo acute. isisacute. is acute. is acute. w2 w2 w2 ww 22 u u u uu θ v θ θv v θθ vv w1 ww w1 w1 11 θ es obtuso obtuse isisobtuse is obtuse is obtuse u u u uu w2 w2 w2 θ θ θ w1 w 1 w1 ww 11 ww 22 θθ v v v vv w1 5 proyvu 5 la proyección de u en v 5 componente vectorial de u en dirección de v w1 1 proj proj projection projection vectorcomponent component alongv v vector of v vcomponent ofvofuuvalong w w proj projection u onto component u along w12 of vofuvuonto vector of uofalong vuvu componente vectorial deuof uonto ortogonal aonto vvector w 51 proj vu projection vu w vector component of u orthogonal to v w vector component of u orthogonal to v w vector component of u orthogonal to v 2 w vector component of u orthogonal to v 2 Figura 2 2 11.29 Figure 11.29 Figure Figure 11.29 11.29 Figure 11.29 y y 10 10 8 8 yy 1010 EJEMPLO 4 4Hallar vectorial uofortogonal vtovv EXAMPLE 4 componente Vector Component Orthogonal EXAMPLE 4la Finding aaComponent Vector Component of uuOrthogonal EXAMPLE aFinding Vector of of u de Orthogonal to to v va to EXAMPLE 4Finding Finding a Vector Component u Orthogonal EXAMPLE 4 Finding a Vector Component of u Orthogonal to v (5,10) 10) (5, 10) (5, (5, 10) 88 (8, 6) (8, 6) Encontrar lavector componente delofvector de queisis esorthogonal ortogonal ato4, dado Find the vector component of5, u that 5, that orthogonal v 4, 3, giventhat that Find the vector component of u10 5, 10 to v3, 4, 3, given Find thethe vector component u 5, is10 orthogonal to vto 4, given that Find component of u 10 that isthat orthogonal v 3, given that que w 5 proy u 5 k8, 6l y w proj u 8, 6 and w proj u 8, 6 and w proj u 8, 6 and w proj u v8, v 6 and 1 (8,6)6) (8, 1 11 v1 v v u 5, 10 ww w .ww2.2. u 5, u 10 10 w u 5, 5, 10 w 1 1 w2. 121 uu (−3,4)4) u u (−3,(−3, 4) 4)(−3, 44 4 4 (4,3)3) (4, 3) (4, (4, 3) v2 2 2v2 w2 w22 2 ww − 4 − 4− 2 −−2−4 4 −22 2 4 −2 − −2 2 −2 −2 ww12 1ww2 2 w u uu w 51 wu11uw 1 2 w 2 Figure 11.30 Figure Figure 11.30 Figure 11.30 11.30 Figura 11.30 v wv1 w1 42 26 Solución Como es que es w lathat compouBecause 5 v,v, wthat Solution w1where where w1 1isisato parallel follows that w isisthe the Solution uu1w ww2w ,21,where parallel v,v, ititthat follows Solution Because uww w w w paralelo is w parallel toseitv,sigue ittotofollows is w the 1 11 2,2w 2w Solution Because uBecause w ,donde follows 21, where 1 is1 parallel 2 is2 the 2 2 nente vectorial de uofortogonal v.orthogonal Por vector component tose v.tiene So, youhave have vector component ofofuauorthogonal toyou v.you So, you vector component u orthogonal totanto, v. So, have vector component uoforthogonal to v. So, have ww 11 64 48 86 6 x 88 w2 w2 uw w uw2 2 wuuww1 1 1 1 5, 10 8, 8,66 5, 10 10 8, 6 5, 5, 10 8, 6 3, 3,4. 4. 3, 4. 3, 4. w2 2isisorthogonal Check tosee that orthogonal shown Figure 11.30. tothat totoshown v,v,asas inin Figure Check toCheck see that wsee orthogonal to v, shown inshown Figure 11.30. Check to see wisthat is w orthogonal to as v, as in Figure 11.30.11.30. 2 2 Verificar que w 2 es ortogonal a v, como se muestra en la figura 11.30. ■ ■ ■■ Larson-11-03.qxd 788 3/12/09 17:08 CAPÍTULO 11 Page 788 Vectores y la geometría del espacio Del ejemplo 4, se puede ver que es fácil encontrar la componente vectorial w2 una vez que se ha hallado la proyección w1 de u en v. Para encontrar esta proyección, se usa el producto escalar como establece el teorema siguiente, el cual se demuestra en el ejercicio 92. NOTA Ver la diferencia entre los términos “componente” y “componente vectorial”. Por ejemplo, usando los vectores unitarios canónicos o estándar con u 5 u1i 1 u 2 j, u1 es la componente de u en la dirección de i y u1i es la componente vectorial de u en la dirección i. n TEOREMA 11.6 PROYECCIÓN UTILIZANDO EL PRODUCTO ESCALAR Si u y v son vectores distintos de cero, entonces la proyección de u en v está dada por proy projv u 5 1uiv?iv2 v. 2 La proyección de u en v puede expresarse como un múltiplo escalar de un vector unitario en dirección de v. Es decir, 1uiv?iv2 v 5 1uiv? iv2 ivv i 5 skd ivv i k5 2 Al escalar k se le llama la componente de u en la dirección de v. z 4 w2 u EJEMPLO 5 2 w1 u = 3i − 5j + 2k v = 7i + j − 2k −2 6 −4 8 x u?v 5 iu i cos u. iv i v 2 y Descomposición de un vector en componentes vectoriales Hallar la proyección de u en v y la componente vectorial de u ortogonal a v de los vectores u 5 3i 2 5j 1 2k y v 5 7i 1 j 2 2k mostrados en la figura 11.31. Solución w1 5 La proyección de u en v es 14 2 4 s7i 1 j 2 2kd 5 i 1 j 2 k. 1uiv?iv2 v 5 112 54 2 9 9 9 2 La componente vectorial de u ortogonal a v es el vector u 5 w1 1 w2 Figura 11.31 w2 5 u 2 w1 5 s3i 2 5j 1 2kd 2 EJEMPLO 6 1149 i 1 92 j 2 94 k2 5 139 i 2 479 j 1 229 k. Cálculo de una fuerza Una lancha de 600 libras se encuentra sobre una rampa inclinada 30°, como se muestra en la figura 11.32. ¿Qué fuerza se requiere para impedir que la lancha resbale cuesta abajo por la rampa? Solución Como la fuerza debida a la gravedad es vertical y hacia abajo, se puede representar la fuerza de la gravedad mediante el vector F 5 2600j. Para encontrar la fuerza requerida para impedir que la lancha resbale por la rampa, se proyecta F en un vector unitario v en la dirección de la rampa, como sigue. v 5 cos 308 i 1 sen sin 308j 5 v w1 1 i1 j 2 2 Vector unitario en la dirección de la rampa. Por tanto, la proyección de F en v está dada por 30° F w1 = proyv(F) Figura 11.32 !3 w1 5 proy projvvFF 5 1Fiv?i v2 v 5 sF ? vdv 5 s2600d1122 v 5 23001 23 i 1 21 j2. ! 2 La magnitud de esta fuerza es 300, y por consiguiente se requiere una fuerza de 300 libras para impedir que la lancha resbale por la rampa. 1053714_1103.qxp 10/27/08 10:38 AM Page 789 Larson-11-03.qxd 3/12/09 17:08 Page 789 SECCIÓN 11.3 11.3 El producto escalar dosVectors vectores The Dot Product ofde Two 789 789 Trabajo Work F F El trabajo WW realizado una fuerza constante que actúa a lo largo deoflaanrecta de The work done bypor the constant force F actingFalong the line of motion object movimiento de un objeto está dado por is given by P P Q Q Trabajo = =F F PQ Work PQ 5(magnitud smagnitude force dsdistance d 5 iF F i i PQ i WW5W deof fuerza)(distancia) magnitude of force distance PQ \ \ como muestra en la figura 11.33a. Siconstant la fuerzaforce constante F nodirected está dirigida lo largo de as se shown in Figure 11.33(a). If the alongathe line of F is not la recta de movimiento, se puede ver 11.33(b) en la figura queWeldone trabajo W por la motion, you can see from Figure that11.33b the work by realizado the force is fuerza es W projPQ F PQ cos F PQ F PQ . W5 5 iproy iprojPQ F i i PQ i 5 scos udiF i i PQ i 5 F ? PQ . W This notion of work is summarized in the following definition. Esta noción de trabajo se resume en la definición siguiente. (a)La Force acts along thelargo line de of motion. a) fuerza actúa a lo la recta de movimiento \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ F F θ θ proj proy PQ FF PQ Q Q P P Work = projF PQ FPQ PQ Trabajo = proy PQ DEFINITION OF WORK DEFINICIÓN DE TRABAJO The work W done by a constant force F as its point of application moves El trabajo porisuna fuerza medida que su punto de aplicación along W therealizado vector PQ given by constante either of F thea following. se mueve a lo largo del vector PQ está dado por las siguientes expresiones. 1. W projPQ F PQ Projection form 1. WW55iproy En forma de proyección. iprojPQ F i iPQ i 2. W F PQ Dot product form 2. W 5 F ? PQ En forma de producto escalar. \ \ (b) Force acts at angle with the line of motion. b) La fuerza actúa formando un ángulo q con Figure 11.33 la recta de movimiento Figura 11.33 \ \ \ \ \ \ EJEMPLO 7 Cálculo de trabajo EXAMPLE 7 Finding Work closeuna a sliding a person on a tira ropedewith constant 50 pounds at ParaTocerrar puertadoor, corrediza, unapulls persona unaacuerda conforce una of fuerza constante a constant of 60constante , as showndein60°, Figure 11.34. Find theenwork done11.34. in moving theel de 50 libras y angle un ángulo como se muestra la figura Hallar doorrealizado 12 feet toalits closed trabajo mover la position. puerta 12 pies hacia la posición en que queda cerrada. ft 1212 pies projPQFF proy PQ PP QQ 60° 60° SolutionUsando Usinguna a projection, you calculate theelwork as follows. Solución proyección, secan puede calcular trabajo como sigue. W proj F PQ Projection form for work Forma de proyección para el trabajo. W5 5iproy iprojPQ FPQi iPQ i W cos 60 F PQ 5 coss608d iF i i PQ i 1 1 5012 5 s50ds12d 2 2 300 foot-pounds libras-pie 5 300 foot-pounds \ \ FF \ \ \ \ ft 1212 pies Figure 11.34 11.34 Figura 11.3 Exercises Ejercicios 11.3 See www.CalcChat.com for worked-out solutions to odd-numbered exercises. || || 2, (d) En los ejercicios a 8, c) uu 2v, v, d) In Exercises 1– 8, 1find (a)hallar u v, a) (b)uu?v,u, b) (c)u u? u, (u · v)v u x 2v c . ? and (e) yu e) 2v . 1. u 3, 4, v 1, 5 2. u 4, 10, v 2, 3 3. u 6, 4, v 3, 2 4. u 4, 8, v 7, 5 5. u 2, 3, 4, v 0, 6, 5 6. u i, v i 7. u 2i j k vik u v.u In Exercises 9 and En los ejercicios 9 y10, 10,find calcular 9. 9. 10. 10. ■ 8. u 2i j 2k v i 3j 2k 5 3i 3i 1 j,j, vv 5 2i 22i 1 4j 4j 13. uu 13. p sen sin1 2jj 16p6 2ii 1 sin 66 33p 33p sen 5 cos cos1 2ii 1 sin sin1 2jj vv 44 44 5 cos cos 14. uu 14. 5 1, k1, 1, 1, 1 1l 15. uu 15. 5 2, k2, 1, 1, 1 21l vv In Exercises 11–18, find the angle between the vectors. En los ejercicios 11 a 18, calcular el ángulo u entre los vectores. 11. u 1, 1, v 2, 2 12. u 3, 1, v 2, 1 11. u 5 k1, 1l, v 5 k2, 22l 12. u 5 k3, 1l, v 5 k2, 21l 5 2i 2i 2 3j 3j vv 5 3i 3i 1 4j 4j 17. uu 17. 5 2i 2i 2 3j 3j 1 kk 18. uu 18. 5 2j 22j 1 3k 3k vv ? v. 8, 8, ivvi 5 5, 5, yand the angle between iuui 5 py3.v is 3. el ángulo entre uyvu esand 40, 40, ivvi 5 25, 25, yand v is 56. the angle between iuui 5 5py6. el ángulo entre uyvu esand 5 3i 3i 1 2j 2j 1 kk 16. uu 16. 5 ii 2 2j 2j 1 kk vv In 19–26, whether siu and EnExercises los ejercicios 19determine a 26, determinar u y vv are son orthogonal, ortogonales, parallel, or neither. paralelos o ninguna de las dos cosas. 19. 19. 20. 20. uu 5 4, k4, 0, 0l, uu 2, 18, 5 k2, 18l, vv 5 1, k1, 1 1l 3 1 3, 61 vv 2 5 k ,2 l 2 6 Larson-11-03.qxd 26/2/10 14:13 790 CAPÍTULO 11 21. u 4, 3 2 3 23. u j 6k v i 2j 25. u 2, v Vectores y la geometría del espacio 1 3 22. u 1 2, v Página 790 v 24. u k v 26. u 3, 1 1, 1, 1 v i 2i En los ejercicios 43 a 50, a) encontrar la proyección de u sobre v y b) encontrar la componente del vector de u ortogonal a v. 2j 4j 2i 2i 3j j k cos , sen , sen , 43. u k 44. u v 9, 7 , v 1, 4 1, 3 1 45. u 2i 3j, v 5i cos , 0 46. u 2i 3j, v 3i En los ejercicios 27 a 30, se dan los vértices de un triángulo. Determinar si el triángulo es un triángulo agudo, un triángulo obtuso o un triángulo recto. Explicar el razonamiento. 27. 1, 2, 0 , 0, 0, 0 , 6, 7 , 2, 1, 0 0, 3, 3 , v 47. u 48. u 2i j 50. u i 4k, 2k, v 2j 1, 1, 1 8, 2, 0 , v 49. u j 2, 1, v 3j 3i 2k 1 4k 3, 0, 0 , 0, 0, 0 , 1, 2, 3 28. 29. 2, 0, 1 , 0, 1, 2), 30. 2, 7, 3 , Desarrollo de conceptos 0.5, 1.5, 0 1, 5, 8 , 4, 6, 1 51. Definir el producto escalar de los vectores u y v. En los ejercicios 31 a 34, encontrar los cosenos directores de u y demostrar que la suma de los cuadrados de los cosenos directores es 1. 31. u ⫽ i ⫹ 2j ⫹ 2k 32. u ⫽ 5i ⫹ 3j ⫺ k 53. Determinar cuál de las siguientes expresiones están definidas para vectores distintos de cero u, v y w. Explicar el razonamiento. a) u ⭈ 共v ⫹ w兲 33. u ⫽ 具0, 6, ⫺4典 c) u ⭈ v ⫹ w 34. u ⫽ 具a, b, c典 En los ejercicios 35 a 38, encontrar los ángulos de dirección del vector. 35. u ⫽ 3i ⫹ 2j ⫺ 2k 36. u ⫽ ⫺4i ⫹ 3j ⫹ 5k 37. u ⫽ 具⫺1, 5, 2典 38. u ⫽ 具⫺2, 6, 1典 En los ejercicios 39 y 40, usar una herramienta de graficación para encontrar la magnitud y los ángulos de dirección de la resultante de las fuerzas F1 y F2 con puntos iniciales en el origen. Se dan la magnitud y el punto final de cada vector. Vector 52. Dar la definición de vectores ortogonales. Si los vectores no son paralelos ni ortogonales, ¿cómo se encuentra el ángulo entre ellos? Explicar. b) 共u ⭈ v兲w d) 储u储 ⭈ 共v ⫹ w兲 54. Describir los cosenos directores y los ángulos de dirección de un vector v. 55. Dar una descripción geométrica de la proyección de u en v. 56. ¿Qué puede decirse sobre los vectores u y v si a) la proyección de u en v es igual a u y b) la proyección de u en v es igual a 0? 57. ¿Si la proyección de u en v tiene la misma magnitud que la proyección de v en u, ¿se puede concluir que 储 u储 ⫽ 储 v 储? Explicar. Magnitud Punto final Para discusión 39. F1 50 lb F2 80 lb 共10, 5, 3兲 共12, 7, ⫺5兲 共⫺20, ⫺10, 5兲 共5, 15, 0兲 58. ¿Qué se sabe acerca de , el ángulo entre dos vectores distintos de cero u y v, si 40. F1 300 N F2 100 N 41. Cables que soportan una carga Una carga es soportada por tres cables, como se muestra en la figura. Calcular los ángulos de dirección del cable de soporte OA. z (−4, −6, 10) B (4, −6, 10) C (0, 10, 10) A O 300 libras y x 42. Cables que soportan una carga La tensión en el cable OA del ejercicio 41 es 200 newtons. Determinar el peso de la carga. a) u ⭈ v ⫽ 0? b) u ⭈ v > 0? c) u ⭈ v < 0? 59. Ingresos El vector u ⫽ 具3 240, 1 450, 2 235典 da el número de hamburguesas, bocadillos de pollo y hamburguesas con queso, respectivamente, vendidos en una semana en un restaurante de comida rápida. El vector v ⫽ 具1.35, 2.65, 1.85典 da los precios (en dólares) por unidad de los tres artículos alimenticios. Encontrar el producto escalar u · v y explicar qué información proporciona. 60. Ingresos Repita el ejercicio 59 después de incrementar los precios 4%. Identificar la operación vectorial usada para incrementar los precios 4%. 61. Programación Dados los vectores u y v mediante sus componentes, escribir un programa para una herramienta de graficación que calcule a) 储 u 储, b) 储 v 储, y c) ángulo entre u y v. 62. Programación Con el programa escrito en el ejercicio 61 encontrar el ángulo entre los vectores u ⫽ 具8, ⫺4, 2典 y v ⫽ 具2, 5, 2典. 1053714_1103.qxp 10/27/08 10:38 AM Page 791 1053714_1103.qxp Larson-11-03.qxd 3/12/09 17:08 Page 791 1053714_1103.qxp 10/27/08 10:38 AM Page 791 1053714_1103.qxp 10/27/08 10:38 AM Page 791 3714_1103.qxp 10/27/08 10:38 AM Page 791 08 10:38 AM Page 791 10/27/08 10:38 AM Page 791 791 The Dot Product of Two Vectors El producto escalar dosVectors vectores 791 791 The Dot Product of de Two 11.3 The Dot Produc 791 11.3 The Dot Product of Two Vectors Product of Two Vectors 791 791 11.311.3The The Dot Dot Product of Two Vectors 791 11.3 The Dot Product of Two Vectors 74. Work A toy wagon is pulled by exerting a force of 25 pounds 63. Programming Given vectors u and v in component form, 74. Work uinyvwhich v in Programación Dados los vectores mediante sus compoTrabajo coche decomponent juguete seexerting jala ejerciendo 74. A toy wagon pulled a the force 25fuerza pounds 63. Programming Given vectors component form, u and 74.ofuna Work Ade toy wagon is pulled by e 63.output Programming Given vectors inis form, uUnand vmakes on a handle that a 20 byangle with horizontal (see write a program for a graphing utility the is the nentes, escribir un programa para graficación 25 libras sobre una manivela que forma de 20° con on atoy handle that makes athe angle with the (seela that makes a 20 an 20 a program for athe utility which thedeform, output is theWork 74. Work A isbypulled by exerting aángulo force of 25 pounds 63.write Programming vectors and component form, v inv.form, on awagon handle write a74. program forA atoy graphing utility inpulled which output the 74. Work A iswagon exerting aisdone force of 25horizontal pounds 63. Programming Given vectors inherramienta component u and vucomponent wagon istoy pulled by exerting awork force of un 25in pounds 63. Programming Given vectors and ugraphing v in figure inwagon left column). Find the pulling the component form ofGiven projection of onto uin 74. Work Aoutput toydewagon byon exerting a force ofmakes 25 g Given vectors uwrite and avcomponent incalcule component form, que las componentes de proyección horizontal (ver la figura). Calcular elhorizontal trabajo realizado jalar el column). Find the wo uisen v.is pulled figure left column). the done in the pulling thealwagon form of the projection of onto u in v. on a in handle awith angle with horizontal 20work write forutility a graphing utility which the output is the figure in(see left component ofa the projection of upounds v. angle handle that amakes with the horizontal (see 20Find program for a graphing utility inla which the the onform a handle that makes athat angle the (see 20onto write a 64. program fora aprogram graphing in which the output the 50 feet. Programming Use the program you wrote inisthat Exercise 63a to on a handle makes angle with the horizontal (see 20 am for a graphing utility in which the output is the coche 50 pies. 50 feet. figure in left column). Find the work done in pulling the wagon component form of the projection of onto u v. 64. Programación Usar el programa escrito en el ejercicio 63 50 feet. figure in left column). Find the work done in pulling the wagon component ofprojection the Use projection u onto v. in left column). Find the work done in pulling wagon component formform of the ofprogram onto uuof v.you 64. Programming the Exercise 63and tofigure Use 64. the you wrote inusing Exercise 63 to 75. Work A car towed a force ofthe 1600 newtons. The find the projection of onto for v wrote uincolumn). 5,Programming 6, 2 Find figure invleft the work done inprogram pulling theis wagon orm of the projection of u onto 50 feet. para v.Use encontrar la program proyección de en y50 uyou 5 k5, 2l 5075. feet. feet. 75. Work Trabajo Un carro secar remolca una fuerza deWork 1 600 The newA car is towed using ausando force of 1600 newtons. the1, Use projection of onto for andto uyou vExercise usi63 5,63find 6, 26,the 64.find the wrote inu to Exercise 63 75. A car is towed using a f projection of onto for and u v u 5, 6, 2 64. Programming the wrote in Exercise to 64. Programming the youprogram wrote in chain used to pull the makes a angle with the horizontal. 25 vProgramming 3, 4program . Use 50 feet. g Use the programfind you wrote inthe 5projection k21, 3,of tons. La que secar usa para jalar elnewtons. forma un ángulo deto pull the car makes a 2 chain used tocar pull aaof25 angle with the horizontal. vvfind 1,Exercise 3, 44l..uof63 75.car Work Atowed isthe towed using force ofnewtons. 1600 newtons. The projection of and uv onto 6, 2 75.1, chain used 3, . A 75.4 Work A car iscadena using amakes force 1600 The for uto onto 2 5,vand Work is towed using ain force ofthe 1600 The find the the projection onto v for u uv5,for 6, 5, 2 u6, and Find the work done towing car 2 carro kilometers. 75. Work A car is towed using a force of 1600 newtons. The ojection of u onto for and v u 5, 6, 2 25° con la horizontal. Encontrar el trabajo que se realiza al done in towing the Find the work done in towing the car 2 kilometers. chain used to pull the car makes a angle with the horizontal. 25 v 1, 3, 4 . Think About It In Exercises 65 and 66, use the figure to Find the work chain used to pull the car makes a angle with the horizontal. 25 with the horizontal. 1, to pull the car makes a 25byangle v v Para 1, 3, pensar 4 3, . 4 . En los ejercicios 65 y 66, usar la figura para deter-chain used Work A sled is 66, pulled exerting a force of 100 newtons on chain used todan pull the car makes angle with the horizontal. 2576. 4. Think About It Inthe 65 of and 66, use thecoordinates figure toFind Think About It aFind In Exercises 65 and use the figure to remolcar el carro 2 kilómetros. Find the work done in towing the car 2 kilometers. determine mentally projection (The uuonto the work done in towing the car 2 kilometers. minar mentalmente laExercises proyección de en vv.(se las coordethe work done in towing the car 2 kilometers. 76. Work A sled is pulled by exerting force of 100 newtons onsled is pulled by exertin 76. Work A rope that makes a 25v. (The angle with thea horizontal. Find the work Find done in towing the car 2 akilometers. determine mentally the projection of onto (The coordinates u v.work Think Itpoints In and 66, use the figure determine mentally the of coordinates u onto Think About ItAbout Inpuntos Exercises 65 66, use the to Think About It de In Exercises 65Exercises and 66, use thethe figure to of the terminal of the vectors in standard position areto nadas los finales deand los65 vectores en lafigure posición estánadone rope that makes apulled angle with the horizontal. Find the 25 76.projection Work sled isby by exerting a force of 100 onmakes a 25 angle with 76. Trabajo tirathe de un trineo unanewtons fuerza de 100work newanewtons rope that 76. Work A sled isASe pulled exerting aejerciendo force of 100 on 76. Work A sled is pulled by exerting a force of 100 newtons on in pulling sled 40 meters. In Exercisesdetermine 65 and 66, use the figure to the terminal points the vectors standard areexerting determine theof of onto (The coordinates u (The v.sled ofisposition the terminal pointsa force ofdone in standard position mentally the projection of onto u 76. v.in determine of mentally thementally projection ofprojection onto coordinates u v. (The Work Acoordinates pulled by of 100 on given.) Verify your results analytically. dar). Verificar los resultados analíticamente. invectors pulling 40 meters. athe rope that makes asled angle theare horizontal. theinwork 25with tons en una cuerda que hace unwith ángulo de Find 25° con ladone horizontal. pulling the sled 40 meters a rope that makes anewtons angle the horizontal. theFind work 25 the a rope that makes a angle with the horizontal. Find the work 25 ally the projection of onto (The coordinates u v. Verify results of the terminal points ofanalytically. the vectors inposition standard are given.) your analytically. of terminal the given.) terminal points of the vectors in standard position of the points ofyour the vectors in standard areposition a rope that makes aare angle with results the horizontal. Find work 25Verify done pulling the sled 4077meters. el sled trabajo efectuado al jalar trineo 40whether metros. the or False? Inthe Exercises and 78, el determine inEncontrar pulling the 40 meters. donedone inTrue pulling theinsled 40 meters. y position are points of the vectors in standard 65. 66. done iny pulling the sled 40 meters. given.) Verify your results analytically. given.) Verify results analytically. given.) Verify youryour results analytically. True or False? In Exercises 77isand 78, explain determine whether the True False? y y statement is true or false. If it false, why ororgive an In Exercises 77 and y y 65. 66. 65. 66. ur results analytically. (4, 6) 6 ¿Verdadero o falso? En los ejercicios 77 y 78, determinar si la or false. If it is fal 6 v statement is true or false. If it is false, explain why or give an True or False? In Exercises 77 and 78, determine whether the statement is true True or False? In Exercises 77 and 78, determine whether the True or False? In Exercises 77 and 78, determine whether the y v (4, 6) example that shows it is false. (4, 6) y y 65. 66.y or False? (4, 6) 6 77 and 78, 66. yTrue 6 y 65. 65. 66. 6 6 v In Exercises determine whether the declaración es verdadera o falsa. Si es falsa, explicar por qué o v y v (4, 6) example isitfalse, false. v (4,is statement is shows true Ifexplain it isexplain false, why 4 thatan shows it is false. statement is true or false. Ifisfalse. is false, why or example give an give 66. orthat false. If itorit whyexplain or give an or 46 6)true (4, 6) statement (4, 6)or 6 (4, 6) 6 statement 6 is true false. If it is false, explain why or give an v dar un ejemplo que demuestre que es falsa. 6 4 v 6 77. If and then u v u w u 0, v w. v 4 v 4 example that shows it is false. example that shows it is false. 4 example that shows it is false. (4, 6) 6 v (4,v26) (4, 6) v (4, 6) 77. If u v u w and u 0, then v w. v (4, 6) 77. If u v u w and u 0, then example shows it is false. 2that 4 24 4 2 4 4 78. IfSiuuand to entonces is orthogonal to w. v5are w, then uv 5vw. 4 x 77. vvw uu ?orthogonal w u then Þ 0, yand ? 2 2 77. If then u w u 0, v w. 77. If and u v u u 0, v w. 42− 4 u 2 77. If and then u v u w u 0, v w. 78. If u and v are orthogonal to w, then u v is orthogonal to w. 2 4 6 78. If u and v are orthogonal to w, the 2 u w and u x 0, then v 78.w.Si u y v son ortogonales a w, entonces u 1 v es 2 77.2 If−2u 2v w. −4 u 2 4 6 2u and 6v 4 − 46 u78. If 78. Ifvorthogonal and orthogonal to u orthogonal toaw. uare v areto w, v isto 78. If4 u79. and orthogonal to w,athen v isuorthogonal Find the angle between diagonal and one of w. its edges. are orthogonal w,tothen ucube’s v isthen w.ortogonal 2(− 2, −3) 4 −2)6 78. If−2u−2 and v are to w, then79. orthogonal to w. a cube’s u Find v isthe 6 −2between 4 (3, angle diagonal and one of its edges. u orthogonal 79. Find the angle u4 u (− −4 − 2 − 44 2 u6 4 6 2 4 6 79. Find Encontrar el ángulo entre la diagonal un cubo y una de sus between a cube’s d 2, −3) 80. the angle between diagonal of de a cube and the diagonal (− 2, −3) 4 6 −2 (3, −2) diagonal uthe −2−2 46 u 6 (3,4− 2) 6 79. Find −2 −2 4 79. Find the angle between a cube’s and one of its edges. 79. Find the angle between a cube’s diagonal and one of its edges. the angle between a cube’s diagonal and one of its edges. 80. Find the angle between the diagonal of a cube and the diagonal aristas. 80. Find the angle between the diagon 2, −3) 4 67 of one one of itsofsides. 6 a 70, encontrar (−−2 2, (− 2, −3) −2 (3,direcciones −2) athat 79. Find the angle between cube’s diagonal and its edges. −2 u (3, −u2) En−3) los(−ejercicios dos en uvectores (3, − 2) In Exercises 67–70, find two −2 vectors in opposite directions of one ofbetween its sides. 80. Find the angle between the diagonal ofde a un cube andythe diagonal oflaone of its sides. 80. Find the angle the diagonal of a cube and the diagonal −2 (3, − 2) 80. Find the angle between the diagonal of a cube and the diagonal u 80. Encontrar el ángulo entre la diagonal cubo diagonal In Exercises 67–70, find two vectors in opposite directions that opuestas que sean ortogonales vector u.the (Las respuestas no In Exercises 67–70, find two vectors indiagonal opposite directions that are orthogonal to the vector u.al(The answers are not unique.) 80. Find angle between theson diagonal of Exercises aof cube and the of one of its sides. In 81– 84, (a) find all points of intersection of the of one its sides. of one of its sides. de uno de sus lados. are not unique.) are orthogonal to the vector (The answers not unique.)thatto theInvector In67–70, Exercises 67–70, find two vectors in opposite directions únicas.) are orthogonal answers u. (The In Exercises 67–70, find two vectors in opposite directions that In Exercises find two vectors in u. opposite directions that of one of are its sides. Exercises 81– 84, (a) find(b) allfind points of intersection of the In Exercises 1directions 3 graphs of the two equations, the unit tangent vectors to81– 84, (a) find all po 70, find two vectors in opposite that 67. 68.areuanswers 4j not unique.) i vector j (The areuto orthogonal (The u. are orthogonal to14vector the (The answers are9iunique.) not are unique.) u.vector are orthogonal the answers not 32tou.the 1 Exercises 3 Exercises graphs of the two equations, (b) find the unit tangent vectors to In Exercises 81– 84, (a) find all points of intersection of the En los ejercicios 81 a 84, a) encontrar todos los puntos de intergraphs of the two equations, (b) find In 81– 84, (a) find all points of intersection of the In 81– 84, (a) find all points of intersection of the at68. their of 67. u are4 not 68. u 9i 4j 67. u i unique.) u points 4j intersection, and (c) find the angles j eachofcurve o the vector u. (The answers 2j 4 i all2 points In intersection of9i(b) the 69. 70.Exercises 23 u 4, 81– 3, 684, (a) find 1 13 33, 1, each curve at their points of intersection, and (c) find the angles 1 67.u graphs of the two equations, (b) find the unit tangent vectors to sección de las gráficas de las dos ecuaciones; b) encontrar los each curve at their points of intersec graphs of the two equations, find the unit tangent vectors to graphs of the two equations, (b) find the unit tangent vectors to between the curves at their points of intersection. 0 90 68. 9i 3,4j69. 67. u 69. 68. u9igraphs 9i4j 4jthe 67. u i u4ui j 23,j 1, 4i 70. 22 j 68. u 4, uu of 3 u 3, (b) 1, find 2 the u points 4, to 6intersection, two6equations, unit tangent vectors between the3,of curves their of intersection. 0each 9070. 68. u4 9i2 4j at their and (c) the vectores unitarios tangentes a and cadaat curva en puntos deangles inter0find 90 between the curves at curve atcurve their points of intersection, and (c) points find the angles eacheach curve at their points of intersection, (c) find thelos angles 2j 69. 70. u1, 1, 2 A 48,000-pound u6 3,is 6parked 4, their 3, on 6points 2, find 3 69. u3,71. 70. u4, 4, Load truck a 10 slope 69. u 70. Un 1, 3,Braking 2 23,de u 3,de each curve at intersection, (c) angles 81. ythethe x1los y90 between curves their oflas intersection. 0 and qof 71. sección yxbetween Fuerza frenado camión 48 000 libras estáof estac) 90 hallar ángulos (0° £at £intersection. 90°) entre curvas en the curves at their points ofpoints intersection. 0 between curves atthe their points 0 Load 90 70. u71. 2 4, figure). 3, 6Load Braking A 48,000-pound truck is 90 parked on athat slope 10 71. Braking A 48,000-pound truck 81. x11 33is parked on a 10 slope ypoints x23, ofyintersection. (see Assume the only force to overcome is due to 81. y x2, y x1 3 between the curves at their 0 cionado sobre una pendiente de 10° (ver la figura). Si se supone sus puntos de intersección. 82. y x y x , 2 1 3y 13overcome 3 (see figure). Assume the only force toon overcome that toy81.Assume 71. Braking Load truck is parked a 10due slope (see figure). is that due to 1 3x 71. Braking Load A 48,000-pound truck is parked on aslope slope 10 71. Braking Load A 48,000-pound truck isrequired parked akeep 10 81. gravity. Find (a) A the48,000-pound force to theison truck from yx2,82. xy2the ,y y yxonly 81. y2 xto1x1y3 x 32, x, force 82. y x3, y x1 3 que la única a force vencer es lay de to la2, keep gravedad, 1 3hallar a) la 2 d A 48,000-pound(see truckfigure). is parked on a fuerza slope 10 81. y x x y 5 x , y 5 x 81. 83. y 1 x , 1 y x gravity. Find (a) the required the truck from (see figure). Assume the only force to overcome is that due to gravity. Find (a) the force required to keep the truck from Assume the only force to overcome is that due to (see figure). Assume the only force to overcome is that due to 3, 1 3 1 3 2 rolling down the hill and (b) the force perpendicular to the hill. 3 3 1 3 2 82. y x y x 82. fuerza requerida paraand el camión ruede cuesta abajo y yx ,83.xy ,y yx 1 3 x2 x , y 1y3 x 3 1 82. Assume the only force to overcome that due toevitar 83. y 1 x2, y x2 1 3truck 1 from 3rolling rolling down the(a) hill (b)toque the to the hill. gravity. Find the force required the truck from down the hill gravity. Find (a)is the force required toforce the gravity. Find (a) the force required keep theperpendicular from ytruck xB ykeep xto , keep yy 5(b) x1the , 2 yforce 52 x perpendicular 82.2and 84. y x2 1 to the hill. 2x, 2, 1 y (5, − 5, 20) b)keep la fuerza perpendicular a la82. pendiente. 2 3 (a) the force required to the truck from 83. y x , 1 y x 83. y 1 x 1 x 83. y 1 x , 1 y x 84. y x y 1 x, 1 z rolling thethe hill andforce (b) the force 84. y 1 2 x, y x3 1 rolling thedown hill (b) and (b)force the perpendicular the rolling downdown the hill and perpendicular (− −xto 5, the 20)1hill. 2,tohill. 2 2 2 1B B −1perpendicular 5,to 20) 83. y (5, C xthe y 5,hill. y2 5 1 22 x32, (5,y3 −55, x20) 83. the hill and (b) the force perpendicular to the hill. 3z (−15, − 5, 20) 2 B 5, − 5, 20) (5, C−5, 20) z (− 84. y x y 1 x, 84. 1 that the diagonals of a rhombus are 84. y y185. 1Use yx, 2 yx tox1Cprove x, vectors B −5, 20) (5, − 5, 20) BCz−15,B2 20)zx,z (−5, (5, − 5, 20) 84. y 5, −x5,3 20)1 y (5, s y 1vectors 1d 5 x, y 5 x3that 2 1the diagonals of a85.rhombus 84. Use 85. to prove are to prove that the d (− Use vectors (− 5,20) − 5, 20) B (5, − 5, 20) 5, −5, perpendicular. C C z (− C A z (− 5, −5, 20) C perpendicular. 85. Use vectors to that prove theofdiagonals of are a rhombus are perpendicular. A 85. Use vectors to prove thethat diagonals ofrhombus a rhombus are 85. Use vectors to prove that the diagonals a A Usarof vectores para are demostrar que las diagonales de unifrombo 85. Use 86. vectors to prove that a parallelogram is a rectangle and A 85. Use vectors to prove that the perpendicular. diagonals a rhombus perpendicular. A perpendicular. 86. Use vectors to prove that a parallelogram is a rectangle if and A A 86. Use vectors to prove that a paralle son perpendiculares. only if its diagonals are equal in length. perpendicular. A 10° only if its diagonals are equal in length. 86. Use vectors to prove that a parallelogram is a rectangle if and only if its diagonals are equal in le 86. Use vectors to prove that a parallelogram is a rectangle if and 86. Use vectors to prove that a parallelogram is a rectangle if and (10, 5, 20) O 86. Bond Usar para demostrar que un paralelogramo un recAngle Consider a regular tetrahedron with esvertices 10° 10° 87. 86. Use vectors to isdiagonals avectores rectangle if and (10, (10, 5, 20) only ifAngle its diagonals are equal in length. O prove that a parallelogram only ifdiagonals its are equal inO length. only if its are equal in length. x 5, 20) 10° 87. Bond Consider a regular tetrahedron with vertices 87. Bond Angle Consider a regula is a positive 0, 0, 0 , sik,y k,sólo 0 , sik,sus 0, diagonales k , and 0, son k, k iguales , whereen k longitud. (10, 5, 10° 10° 10° only if5,20) its diagonals are equal in length. tángulo O x 1000 (10, (10, x Consider 20)5, 20) Weight = 48,000 (10, lb 5, O 20) kg O O and where is a positive 0, 0, 0 , k, k, 0 , k, 0, k , 0, k, k , k 10° 87. Bond Angle a regular tetrahedron with vertices 0, 0, 0 , k, k, 0 , k, 0, k , and 0 87. Bond Angle Consider a regular tetrahedron with vertices 87. Bond Angle Consider a regular tetrahedron with vertices real number. x 1000 kg (10, 5, 20) O 87. Ángulo de enlace Considerar un tetraedro regular con los véry Weight = 48,000 lb x =0,48,000 lb 1000 kg0, k0,, k, x Angle Consider 87. Bond aWeight regular tetrahedron with vertices x real number. and where is a positive 0, 0, 0 , k, k, 0 , k, 0, k, k , k real number. and where is a positive 0, 0 , k, k, 0 , k, 0, k , k , k and where is a positive 0, 0, 0 , k, k, 0 , k, 0, k , 0, k, k , k 1 000 kg y Peso = 48 000 libras x s0, k0,isthe 0da, sgraph k, k, 0of d, (k, k)y y s0, k, kd, donde k es un número Sketch the0,tetrahedron. kg72 Weight =Weight 48,000 where positive 0,kg 0, 1000 0 ,fork, k, 0 , y k, 0, k , and real 0, k,number. k (a) ,tices Figure for 71 Weight = 48,000 lb =lb48,000 lb 10001000 kg Figure real number. real number. (a) Sketch the graphfor of the tetrahedron. (a) Sketch the graph of the tetrahe y ht = 48,000 lb 1000 kg for 71 y 72 y real positivo. Figure Figure for Figure for 71 Figure 72 real number. (b) Find the length of each edge. y (a) Sketch the graph of the tetrahedron. 72. Load-Supporting Cables Find the magnitude of the projection (a) Sketch the graph of the tetrahedron. Figura para 71 Figura para 72 (a) Sketch the graph of tetrahedron. (b) Find thelalength of del eachtetraedro. edge. Figure Figure 72 (b) Find the length of each edge. Figure for 71 for 71 Figure for 72 for a) Find Dibujar gráfica Figure for Load-Supporting 71 Figure for 72 (a) Sketch the graph theastetrahedron. (c) between anyprojection two edges. 72. Cables FindOA the magnitude of72. theLoad-Supporting projection Cables Findthe theangle magnitude of the 1 Figure of for the 72 load-supporting cable onto the positive axis z-of (b) Find the length ofdeeach edge. (b) Find the length of each edge. (b) Find the length of each edge. Cables que soportan una carga Calcular la magnitud de la 72. (c) Find the angle between any two edges. b) Hallar la longitud cada arista. (c) Find the angle between any tw the Cables load-supporting onto the positive axis asedge. OAthe 72.of Load-Supporting of the projection ofzthe load-supporting onto between the positive as z-axis 72. Load-Supporting Cables Find the Find magnitude of the projection 72. Load-Supporting FindCables thecable magnitude ofmagnitude the projection (b) Find the length of each (d)cable Find OA the angle the line segments from the centroid shown in the figure. proyección del cable OA en el eje z positivo como se muestra en rting Cables Find the magnitude of the projection (c) Find the angle between any two edges. (c) Find the angle between any two edges. (c) Find the angle between any two edges. c) Hallar el angle ángulobetween entre cada dos aristas. Find the the line segments from the the cable figure. of theinload-supporting cable onto the positive as figure. (d) (d)centroid Find the angle between the lin shown in the of load-supporting the shown load-supporting cable ontoOA the positive axis asz-axis OA zof the onto axis as (c) Find angle between 73. Work An object isOA pulled 10the feetpositive across az-the floor, using a forceany two edges. k 2, k 2, k 2 to two vertices. This is the bond angle for a la figura. supporting cable OAshown onto axis as z-figure. to two vertices. This isde the bond angle ak 2, k 2 to two vertices kFind 2, kthe 2, k the 2 as (d) angle between the line segments from the centroid shown in the kof 2, (d) isFind the angle between the line segments from the centroid inthe thepositive figure. d) Hallar el ángulo entre los segmentos recta desde elfor cen(d) Find the angle between line segments from the centroid shown 73. in the figure. molecule such or where the structure the PbCl CH , Work An object is pulled 10 feet across a floor, using a force 73. Work An object pulled 10 feet across a floor, using a force 4 of 85 pounds. The direction of (d) the Find forcetheis angle thethe line segments from the centroid 4 60 above between figure. 73. Trabajo Un objeto es jalado 10 pies por el suelo, usando una molecule such as or where the structure of the PbCl CH , to two vertices. This is the bond angle for k 2, k 2, k 2 molecule to two vertices. This is the bond angle for a 2, 2, 2stwo de los vértices. Éste ky2, ky2, ky2isThis d 4a60dos isabove the angle for a es el ánguloa such as CH 4 or PbC k 2, kkdirection 2, kktroide 2 ktoof 4bond molecule isvertices. aforce tetrahedron. 85object pounds. The direction the forceusing above the 60 73.of Work is10 pulled 10aoffeet a is floor, using a force of pounds. the the 73. Work An isobject pulled feet across a across floor, 73. Work An object is An pulled 10 feet across floor, using force horizontal (see figure). Find the work done. to85 two vertices.The This is the bond angle foror aPbCl k 2, kaes2, ka force 2sobre fuerza de 85 libras. La dirección de la fuerza 60° la homolecule is a tetrahedron. bject is pulled 10 feet across a floor, using a force molecule such as or where the structure of the is a tetrahedron. PbCl CH , molecule such as where the structure of the molecule CH , de enlace en una molécula como o estrucCH PbCl molecule such as or where the structure of the PbCl CH , 44 (seedirection figure). Find the force work 4 vectors of 85 The ofis the is the above the figure). 60 the Find the work 4 of pounds. 85 horizontal pounds. The of force the is force above 60 4 done. of 85 Thepounds. direction of direction the above 60done. Consider the and 0 u 4 cos , sen 4,, cuya molecule suchhorizontal as CH 4 or(see where the structure of the 4 PbCl 488. , molecule rizontal (ver la figura). Calcular el trabajo realizado. s. The direction ofhorizontal the force is above the 60 molecule is a tetrahedron. is a tetrahedron. tura es un tetraedro. molecule is a tetrahedron. 88. Consider the vectors and 0 u cos , sen , horizontal (see figure). the work done. 88. Consider vectors u (see figure). theFind work done. horizontal (see figure). FindFind the work done. where Find the dot product of the the v cos , sen , 0 , . > molecule is a tetrahedron. ee figure). Find the work done. product the , use sen , 0result , where . Find >cos 88.vvectors Consider the and, sen , 0 , where > , 0 of cos 88. Consider the ,identity sen 0, sen ucos 88. Considerar losvectors vectores y vand 88. Consider thecos and 0the, dot uvectors ,u sen , cos andvectors the to prove the 88. Consider the vectors u cos sen ,0use thea,and result to prove identity Find theof dot the use the result to prove v , ,sen ,0sen 0 b. , where . product dot product ofvectors the , where . Find donde elthe producto escalar de losofand vecFind the>dot theproduct v vcos cos ,vectors sen , cos 0and , ,where .>Calcular > 85 lb where Find the dot product oftothe v cos , sen , 0 , . > cos cos cos sen sen .la identidad vectors and use the result to the identity vectors and use the el result prove theprove identity 85 lb tores y usar resultado para demostrar andcos use the result to prove the identity 85 lb vectors cos cos sen sen . cos cos cos sen 85 libras vectors and use the result to prove the identity 2 85 lb 85 lb85 lb u cos v sen u 2 sen v. 2 sen2u. v. 20° coscosthat cos cos sen cos sen cos cos89. Prove cos sen . that u 20°v 2 u 2 v 2 2u v. 89. Prove that u v 2 20° u 2 v 60° cos cos cos sen 89. sen Prove . 90. Prove the Cauchy-Schwarz Inequality v ? v. u v . 2 5 i 2 1 2i v i 2u2 2u 2 iu 2 vi ui 89. Demostrar que 20° 2 2 60° 2 2 2 60° 89. Prove that u v u v 2u v. 20° 89. Prove that u v u v 2u v. 20° 89. Prove that u v v 2u v. 20° 90. Prove the Cauchy-Schwarz Inequality u v u v . 90. Prove the Cauchy-Schwarz Inequ 10 ft 60° 89. Prove that u v 2 u 2 v 291. 2u v.the triangle 20° Prove inequality u v u v . 90. Demostrar la desigualdad de Cauchy-Schwarz 60° 60° 1060° ft ft Prove 90.Cauchy-Schwarz Prove thetriangle Cauchy-Schwarz Inequality u vthe . triangle inequality u 90. the Cauchy-Schwarz Inequality 90.10Prove the Inequality u vuv v uuu vuv.91. 91. Prove the inequality vv ..Prove Not drawn to scale 10 pies 90. Prove the Cauchy-Schwarz Inequality u v u v . 92. Prove Theorem 11.6. 10Not ft drawn to scale 10 ft 10 ft Not drawn to scale 91.triangle Prove the triangle v . 91. Prove the triangle inequality uv v uu uv v . vu. 91. Prove the inequality uinequality 92. Prove Theorem 11.6. Figure for 73 Figure for 74 11.6. No está dibujado a escala i ≤ Prove i u i 1Theorem i v i. 91. Provefor the74triangle inequality u v91. Demostrar u v la . desigualdad del triángulo i u 1 v 92. drawn to scale Not73 drawn scale Not for drawn to scaletoNot Figure Figure Figure for 73 Figure for 74 92. Prove Theorem 11.6. 92. Prove Theorem 11.6. 92. Prove Theorem 11.6. ot drawn to scale 92. Demostrar el teorema 11.6. 73 Figura 74 11.6. Prove Theorem Figure for 73 Figure for 74 Figure for 73 para Figure for 74 para Figure for Figura 73 Figure for92. 74 Figure for 74 11.3 SECCIÓN 11.3 11.3 Larson-11-04.qxd 792 3/12/09 17:20 CAPÍTULO 11 Page 792 Vectores y la geometría del espacio 11.4 El producto vectorial de dos vectores en el espacio n n Hallar el producto vectorial de dos vectores en el espacio. Usar el producto escalar triple de tres vectores en el espacio. El producto vectorial EXPLORACIÓN Propiedad geométrica del producto vectorial Se muestran abajo tres pares de vectores. Usar la definición para encontrar el producto vectorial de cada par. Dibujar los tres vectores en un sistema tridimensional. Describir toda relación entre los tres vectores. Usar la descripción para escribir una conjetura acerca de u, v y u 3 v. a) u 5 k3, 0, 3l, v 5 k3, 0, 23l z 3 2 −2 u 1 −3 1 1 3 x 2 b) u 5 k0, 3, 3l, v 5 k0, 23, 3l z 2 −3 −2 Sean u 5 u 1i 1 u 2 j 1 u3 k y v 5 v 1i 1 v 2 j 1 v 3k vectores en el espacio. El producto cruz de u y v es el vector u 3 v 5 su 2v3 2 u 3v2 di 2 su 1v3 2 u 3v1 dj 1 su 1v2 2 u 2v1 dk. Una manera adecuada para calcular u 3 v es usar determinantes con expansión de cofactores. (Esta forma empleando determinantes 3 3 3 se usa sólo para ayudar a recordar la fórmula del producto vectorial, pero técnicamente no es un determinante porque las entradas de la matriz correspondiente no son todas números reales.) y 3 −3 3 DEFINICIÓN DE PRODUCTO VECTORIAL DE DOS VECTORES EN EL ESPACIO NOTA Asegurarse de ver que esta definición sólo aplica a vectores tridimensionales. El producto vectorial no está definido para vectores bidimensionales. n −3 v v En muchas aplicaciones en física, ingeniería y geometría hay que encontrar un vector en el espacio ortogonal a dos vectores dados. En esta sección se estudia un producto que da como resultado ese vector. Se llama producto vectorial y se define y calcula de manera más adecuada utilizando los vectores unitarios canónicos o estándar. El producto vectorial debe su nombre a que da como resultado un vector. Al producto vectorial también se le suele llamar producto cruz. 1 1 k u3 v3 i 5 u1 v1 j u2 v2 k u3 i 2 v3 −3 u 3 2 −2 x 5 −3 −3 v −2 −2 1 u x −3 −3 2 i u1 v1 j u2 v2 | | u3 j1 v3 k u3 j 1 v3 u1 v1 | i u1 v1 u2 k v2 ⱍ ⱍ a c 1 2 | | u3 u i2 1 v3 v1 || Put “v”“v” in en Row 3. 3. Poner la fila j u2 v2 | k u3 k v3 Notar el signo menos delante de la componente j. Cada uno de los tres determinantes 2 3 2 se pueden evaluar usando el modelo diagonal siguiente. y g z 2 u2 v2 Poner la fila Put “u“u” ” in en Row 2. 2. 5 su 2v 3 2 u 3v 2d i 2 su 1v 3 2 u 3v 1d j 1 su1v2 2 u 2v 1d k c) u 5 k3, 3, 0l, v 5 k3, 23, 0l 3 | y 3 | || j u2 v2 −2 2 | | i u 3 v 5 u1 v1 3 y b ⫽ ad ⫺ bc d Aquí están un par de ejemplos. | | | | 2 3 4 26 4 5 s2ds21d 2 s4ds3d 5 22 2 12 5 214 21 0 5 s4ds3d 2 s0ds26d 5 12 3 Larson-11-04.qxd 3/12/09 17:20 Page 793 SECCIÓN 11.4 NOTACIÓN PARA LOS PRODUCTOS ESCALAR Y VECTORIAL La notación para el producto escalar y para el producto vectorial la introdujo el físico estadounidense Josiah Willard Gibbs (18391903). A comienzos de la década de 1880, Gibbs construyó un sistema para representar cantidades físicas llamado “análisis vectorial”. El sistema fue una variante de la teoría de los cuaterniones de Hamilton. EJEMPLO 1 El producto vectorial de dos vectores en el espacio 793 Hallar el producto vectorial Dados u 5 i 2 2j 1 k y v 5 3i 1 j 2 2k, hallar cada uno de los siguientes productos vectoriales. a) u 3 v Solución b) v 3 c) v u | || | || i a) u 3 v 5 1 3 j 22 1 k 22 1 5 1 22 3 v | | | | | 1 1 i2 22 3 1 1 j1 22 3 22 k 1 5 s4 2 1d i 2 s22 2 3d j 1 s1 1 6d k 5 3i 1 5j 1 7k b) v 3 i u5 3 1 j 1 22 k 1 22 5 22 1 | | | | | 22 3 i2 1 1 22 3 j1 1 1 1 k 22 5 s1 2 4di 2 s3 1 2dj 1 s26 2 1dk 5 23i 2 5j 2 7k | | Notar que este resultado es el negativo del obtenido en el inciso a). c) v 3 i v5 3 3 j 1 1 k 22 5 0 22 Los resultados obtenidos en el ejemplo 1 sugieren algunas propiedades algebraicas interesantes del producto vectorial. Por ejemplo, u 3 v 5 2 sv 3 ud,y v 3 v 5 0. Estas propiedades, y algunas otras, se presentan en forma resumida en el teorema siguiente. TEOREMA 11.7 PROPIEDADES ALGEBRAICAS DEL PRODUCTO VECTORIAL Sean u, v y w vectores en el espacio, y sea c un escalar. 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. u 3 v 5 2 sv 3 ud u 3 sv 1 wd 5 su 3 vd 1 su 3 wd csu 3 vd 5 scud 3 v 5 u 3 scvd u30503u50 u3u50 u ? sv 3 wd 5 su 3 vd ? w DEMOSTRACIÓN Para demostrar la propiedad 1, sean u 5 u 1i 1 u 2 j 1 u 3k y v = v1i + v2 j + v3k. Entonces, u 3 v 5 su 2v 3 2 u 3v 2di 2 su 1v 3 2 u 3v 1dj 1 su 1v 2 2 u 2v 1dk y v 3 u 5 sv 2u 3 2 v3u 2di 2 sv 1u 3 2 v3u 1dj 1 sv1u 2 2 v2u 1dk la cual implica que u 3 v 5 2 sv 3 ud. Las demostraciones de las propiedades 2, 3, 5 y 6 se dejan como ejercicios (ver ejercicios 59 a 62). Larson-11-04.qxd 794 3/12/09 17:20 CAPÍTULO 11 Page 794 Vectores y la geometría del espacio Observar que la propiedad 1 del teorema 11.7 indica que el producto vectorial no es conmutativo. En particular, esta propiedad indica que los vectores u 3 v y v 3 u tienen longitudes iguales pero direcciones opuestas. El teorema siguiente da una lista de algunas otras de las propiedades geométricas del producto vectorial de dos vectores. NOTA De las propiedades 1 y 2 presentadas en el teorema 11.8 se desprende que si n es un vector unitario ortogonal a u y a v, entonces u 3 v 5 ± s iui i v i sen sin u dn. n TEOREMA 11.8 PROPIEDADES GEOMÉTRICAS DEL PRODUCTO VECTORIAL Sean u y v vectores distintos de cero en el espacio, y sea u el ángulo entre u y v. u 3 v es ortogonal tanto a u como a v. iu 3 v i 5 iui iv i sen sin u u 3 v 5 0 si y sólo si u y v son múltiplos escalares uno de otro. iu 3 v i 5 área del paralelogramo que tiene u y v como lados adyacentes. 1. 2. 3. 4. DEMOSTRACIÓN sigue que Para la propiedad 2, observar que como cos u 5 su ? vdys iui i vi d, se iui ivi sen sin u 5 iui ivi!1 2 cos 2 u su ? vd 2 5 iui ivi 12 iui 2 ivi 2 5 ! iui 2 ivi 2 2 su ? vd 2 5 !su12 1 u22 1 u32dsv12 1 v22 1 v32d 2 su 1v1 1 u 2v2 1 u 3v3d 2 5 !su 2v3 2 u 3v2) 2 1 su 1v3 2 u 3v1d 2 1 su 1v2 2 u 2v1d2 ! v v sen θ θ u Los vectores u y v son los lados adyacentes de un paralelogramo Figura 11.35 5 iu 3 v i. Para demostrar la propiedad 4, ir a la figura 11.35 que es un paralelogramo que tiene v y u como lados adyacentes. Como la altura del paralelogramo es ivi sen sin u, el área es Área = (base)(altura) = u v sen θ = u×v . Las demostraciones de las propiedades 1 y 3 se dejan como ejercicios (ver ejercicios 63 y 64). Tanto u 3 v como v 3 u son perpendiculares al plano determinado por u y v. Una manera de recordar las orientaciones de los vectores u, v, y u 3 v es compararlos con los vectores unitarios i, j y k 5 i 3 j, como se muestra en la figura 11.36. Los tres vectores u, v y u 3 v forman un sistema dextrógiro, mientras que los tres vectores u, v y v 3 u forman un sistema levógiro. k=i×j u×v j i Plano xy Sistemas dextrógiros Figura 11.36 v u Plano determinado por u y v Larson-11-04.qxd 3/12/09 17:20 Page 795 SECCIÓN 11.4 Hallar un vector unitario que es ortogonal tanto a (−3, 2, 11) u 5 i 2 4j 1 k como a v 5 2i 1 3j. 12 Solución El producto vectorial u 3 v, como se muestra en la figura 11.37, es ortogonal tanto a u como a v. 10 | | 8 i u3v5 1 2 6 u×v 4 (1, −4, 1) j 24 3 k 1 0 Producto vectorial. 5 23i 1 2j 1 11k −4 Como 2 u iu 3 vi 5 !s23d 2 1 2 2 1 11 2 5 !134 2 2 y 4 v un vector unitario ortogonal tanto a u como a v es (2, 3, 0) 4 u3v 3 2 11 52 i1 j1 k. iu 3 vi !134 !134 !134 x El vector u como a v 795 Utilización del producto vectorial EJEMPLO 2 z El producto vectorial de dos vectores en el espacio 3 v es ortogonal tanto a u NOTA En el ejemplo 2, notar que se podría haber usado el producto vectorial v 3 u para formar un vector unitario ortogonal tanto a u como a v. Con esa opción, se habría obtenido el negativo del vector unitario encontrado en el ejemplo. n Figura 11.37 Aplicación geométrica del producto vectorial EJEMPLO 3 Mostrar que el cuadrilátero con vértices en los puntos siguientes es un paralelogramo y calcular su área. A 5 s5, 2, 0d B 5 s2, 6, 1d C 5 s2, 4, 7d D 5 s5, 0, 6d Solución En la figura 11.38 se puede ver que los lados del cuadrilátero corresponden a los siguientes cuatro vectores. z \ AB 5 23i 1 4j 1 k 8 6 \ AD 5 0i 2 2j 1 6k \ C = (2, 4, 7) \ \ CD 5 3i 2 4j 2 k 5 2AB \ \ CB 5 0i 1 2j 2 6k 5 2AD \ \ \ D = (5, 0, 6) \ 4 6 B = (2, 6, 1) 6 | i AB 3 AD 5 23 0 2 2 \ Por tanto, AB es paralelo a CD y AD es paralelo a CB , y se puede concluir que el cuadrilátero es un paralelogramo con AB y AD como lados adyacentes. Como \ y j 4 22 | k 1 6 \ Producto vectorial. 5 26i 1 18j 1 6k el área del paralelogramo es A = (5, 2, 0) \ x El área del paralelogramo es aproximadamente 32.19 Figura 11.38 i AB \ 3 AD i 5 !1036 < 32.19. ¿Es el paralelogramo un rectángulo? Para decidir si lo es o no, se calcula el ángulo entre los vectores AB y AD . \ \ Larson-11-04.qxd 796 3/12/09 17:20 CAPÍTULO 11 Page 796 Vectores y la geometría del espacio En física, el producto vectorial puede usarse para medir el momento M de una fuerza F respecto a un punto P, como se muestra en la figura 11.39. Si el punto de aplicación de la fuerza es Q, el momento de F respecto a P está dado por M \ M 5 PQ 3 F. Momento de F respecto a P. \ P La magnitud del momento M mide la tendencia del vector PQ al girar en sentido contrario al de las manecillas del reloj (usando la regla de la mano derecha) respecto a un eje en dirección del vector M. PQ Q F Una aplicación del producto vectorial EJEMPLO 4 El momento de F respecto a P Figura 11.39 Se aplica una fuerza vertical de 50 libras al extremo de una palanca de un pie de longitud unida a un eje en el punto P, como se muestra en la figura 11.40. Calcular el momento de esta fuerza respecto al punto P cuando u 5 608. z Q Solución Si se representa la fuerza de 50 libras como F 5 250k y la palanca como F !3 1 PQ 5 coss608d j 1 sen sins608dk 5 j 1 k 2 2 \ 60° P | | el momento de F respecto a P está dado por y i x \ Una fuerza vertical de 50 libras se aplica en el punto Q Figura 11.40 M 5 PQ 3 F5 0 0 j k 1 2 0 !3 2 250 5 225i. Momento de F respecto a P. La magnitud de este momento es 25 libras-pie. NOTA En el ejemplo 4, notar que el momento (la tendencia de la palanca a girar sobre su eje) depende del ángulo u. Cuando u 5 py2, el momento es 0. El momento es máximo cuando u 5 0. n El triple producto escalar (o producto mixto) Dados vectores u, v y w en el espacio, al producto escalar de u y v u ? sv 3 3 w wd se le llama triple producto escalar, como se define en el teorema 11.9. La demostración de este teorema se deja como ejercicio (ver ejercicio 67). PARA MAYOR INFORMACIÓN Para ver cómo el producto vectorial se usa para modelar el momento de un brazo de robot de un transbordador espacial, ver el artículo “The Long Arm of Calculus” de Ethan Berkove y Rich Marchand en The College Mathematics Journal. TEOREMA 11.9 EL TRIPLE PRODUCTO ESCALAR Para u 5 u1i 1 u2 j 1 u3 k, v 5 v1 i 1 v2 j 1 v3 k, y w 5 w1i 1 w2 j 1 w3k, el triple producto escalar está dado por u ? sv 3 | u1 wd 5 v1 w1 u2 v2 w2 | u3 v3 . w3 NOTA El valor de un determinante se multiplica por 21 si se intercambian dos de sus filas. Después de estos dos intercambios, el valor del determinante queda inalterado. Por tanto, los triples productos escalares siguientes son equivalentes. u ? sv 3 wd 5 v ? sw 3 ud 5 w ? su 3 vd n Larson-11-04.qxd 3/12/09 17:20 Page 797 1053714_1104.qxp 053714_1104.qxp 10/27/08 11:46 AM SECCIÓN 11.4 v×w 11:46 AM Page 797 El producto vectorial de dos vectores en el espacio 797 Si los vectores 11.4 u, v yThe w no están en elofmismo plano,in el triple producto Cross Product Two Vectors Space 797 escalar u ? sv 3 w) puede usarse para determinar el volumen del paralelepípedo (un poliedro, en el que todas sus caras son paralelogramos) con u,vv×yww como aristas adyacentes, como seIf the vectors u, v, u v w) can be used muestra en la u, figura 11.41. Esto en elplane, teorema If the vectors notselieestablece in the same the siguiente. triple scalar product v, and w do all of whose faces are pa u v w) can be used to determine the volume of the parallelepiped (a polyhedron, Figure 11.41. This is est all of whose faces are parallelograms) with u, v, and w as adjacent edges, as shown in TEOREMA INTERPRETACIÓN GEOMÉTRICA DEL TRIPLE PRODUCTO ESCALAR Figure 11.41. This11.10 is established in the following theorem. u v×w u El volumen V de un paralelepípedo con vectores u, v y w como aristas adyacentes está dado por GEOMETRIC PROPERTY OF THE TRIPLE SCALAR PRODUCT THEOREM 11.10 V 5V uof? asvparallelepiped 3 wd . The volume with vectors u, v, and w as adjacent edges u w 10/27/08 Page 797 | v proyv×w u | w is given by 5 iv 3 wi Áreawde la base v Volumen de paralelepípedo | ? sv 3 w d| Figura v11.41 Area of base w u v Volume of parallelepiped THEOREM 11.10 GE The volume V of a pa is given by v u V v w V u v En w la. figura 11.41 se observa proj v × wu DEMOSTRACIÓN que u u projv × w5 w PROOF y v Figure 11.41 and Area of base v w Volume of parallelepiped iv 3 wi 5 área de la base In Figure 11.41, note that u v w PROOF Figure 11.41 v w area of base iprojv 3 wui 5 altura de paralelepípedo. iproy | w area of b and projv Por consiguiente, el volumen es projv wu height of parallelepiped. V5(altura)(área 5 sheightdsarea of based 5 iproj ui iv 3 wi V Therefore, the volume is de la base) 5 iproyv 3 w u ? sv 3 wd V height area of base projv5wu v w iv 3 wi iv 3 wi u v w v w v 5 wu ? sv 3 wd . u v w . EJEMPLO 5 Cálculo de un volumen por medio | In Figure 11.41 wu heig Therefore, the volume is | V height area o | del triple producto escalar EXAMPLE 5 Volume by the Triple Scalar Product EXAMPLE 5 Volum z Find the volume of u 3i 5j k, v Find the volume of the parallelepiped having Calcular el volumen del paralelepípedo que tiene z (3, − 5, 1) (3, 1, 1) 2 u 3i 5j k, v 2j 2k yand k as adjacent edges. ww 5 3i 3i 1 j 1j k como aristas adyacentes. 1 Solution By Theorem u (3, −5, 1) (3, 1, 1) 2 1 u Solution By Theorem 11.10, you have w 1 V u v w Solución Por el teorema 11.10, se tiene y v 3 w V u v w Triple scalar product 3 5 1 6 y x v w3 V 5 u ? sv 3 wd Triple producto escalar. y 3 (0, 2, −2) v 3 5 1 6 0 2 2 x x 6 (0, 2, −2) 0 32 252 1 3 1 1 The parallelepiped has a volume of 36. (0, 2, −2) Figure 11.42 35 01 21 22 The parallelepiped has a volume of 36. 2 2 3 El paralelepípedo tiene un volumen de 36 Figure 11.42 10 2 3 2 1 2 0 2 1 1 Figura 11.42 3 5 1 1 21 22 3 01 22 3 01 2 34 56 53 2 s25d 1 s1d 1 3 1 3 4 15 6 1 1 6 3 36. 36.5 3s4d 1 5s6d 1 1s26d (3, − 5, 1) in shown mostrado en u z | 1, 1) 11.42 Figure la(3,figura 2 11.42 | | | | | | | | | 5 36. A natural consequen is 0 if and only if the thre A natural consequence of Theorem 11.10 is that the volume of the parallelepiped v v1, v2, v3 , and w is 0 if and only if the three vectors are coplanar. That is, if the vectors u u1, u2, u3 , consecuencia natural del teorema 11.10 es quethey el lie volumen del paraleleplane if and only if v v1, vUna , v , and , w , w have the same initial point, in the same w w 2 3 es 0 ifsi y sólo 1 si 2los 3tres vectores son coplanares. Es decir, si los vectores planepípedo if and only u1 u 5 ku1, u2, u3 l, v 5 kv1, v2, v3l,y w 5 kw1, w2, w3 l tienen el mismo punto inicial, se u 2 plano u 3 si y sólo si u v w v1 encuentran en elumismo 1 u v w v1 v2 v3 0. w1 u u u3 w1 w1 2 w2 3 u ? sv 3 wd 5 v1 v2 v3 5 0. w1 w2 w3 | | Larson-11-04.qxd 3/12/09 17:20 Page 798 1053714_1104.qxp 10/27/08 11:46 AM Page 798 1053714_1104.qxp 10/27/08 10/27/08 11:46 11:46 AM AM Page Page 798 798 1053714_1104.qxp 1053714_1104.qxp 10/27/08 11:46 AM Page 798 1053714_1104.qxp 10/27/08 11:4611:46 AM Page 1053714_1104.qxp 10/27/08 AM 798 Page 798 1053714_1104.qxp 10/27/08 798 CAPÍTULO 11 11:46 AM Page 798 Vectores y la geometría del espacio 798 Chapter 11 Vectors and the Geometry Space 798 Chapter 11 11 Vectors Vectors and and the the Geometry Geometry of of Space Space 798 Chapter 798 Chapter 11 Vectors and the Geometry ofofSpace 798 798 ChapterChapter 11 Vectors and the Geometry of Space 11 Vectors and the Geometry of Space 798 Chapter 11 Vectors and the Geometry of Space Ejercicios See 11.4 Exercises See www.CalcChat.com for worked-out solutions to odd-numbered exercises. 11.4 Exercises See www.CalcChat.com www.CalcChat.com for for worked-out worked-out solutions solutions to to odd-numbered odd-numbered exercises. exercises. Exercises 11.4 See www.CalcChat.com for worked-out solutions to odd-numbered exercises. 11.4 Exercises See www.CalcChat.com for worked-out solutionssolutions to odd-numbered exercises.exercises. 11.4 Exercises See www.CalcChat.com for worked-out to odd-numbered 11.4 En los ejercicios 1 find a 6, the calcular el producto vectorial de los and vecÁrea In EnExercises los ejercicios 27 find a 30,the calcular elthe área del paraleloIn Exercises 1– 6, cross product of the unit vectors Area 27–30, area of parallelogram In Exercises Exercises 1– 1–6, 6, find find the the cross cross product product of of11.4 the unit unit vectors vectors and Area SeeIn In Exercises 27–30, 27–30, find the the areatoof of the parallelogram parallelogram Exercises www.CalcChat.com for worked-out solutions odd-numbered exercises. In the and Area Exercises find area the tores unitarios y dibujar su resultado. gramo que tiene los vectores dados como lados adyacentes. Usar In Exercises 1– 6, find the cross product of the unit vectors and Area In Exercises 27–30, find the area of the parallelogram sketch your result. that has the given vectors as adjacent sides. Use computer sketch your your result. result. that has has the the given given vectors vectors as as adjacent adjacent sides. sides. Use Use aaa computer computer sketch that In Exercises 1– 6, find cross of the of unit and and Area Inthe Exercises 27–30, the area of the parallelogram un has sistema algebraico por27–30, computadora oarea una herramienta de In Exercises 1– 6,the find the product cross product thevectors unit vectors Area In or Exercises find the of the parallelogram sketch your result. that given vectors asfind adjacent sides. Use aresult. computer algebra system a graphing utility to verify your algebra system or a graphing utility to verify your result. jj 3your ii ii 3 jj 1. 2. algebra system oraverificar agraphing graphing utility to verify your result. sketch result. that has the given vectors adjacent sides. Use a Use computer graficación para elasutility resultado. 1. 2. j i i j 1. 2. sketch your result. that has the given vectors as adjacent sides. a computer In Exercises 1– 6, find the cross product of the unit vectors and Area In Exercises 27–30, find the area of algebra system or to verify your result. 1.j j i i 2.i i j j 1.3. 2.4. jj 3 kk kk 3 sketch jj algebra system or a graphing utility to your uu algebra jj uu verify ii to verify jhas kthe 27. 28. j k kresult. 27. u 28. utility system or a graphing your result. your result. that given vectors as adjacent side 3. 4. j k k j 3. 4. j u i j 27. 28. ik j i jj i j 1. 2. 27.u u 5j j 28.u u 5i i 1j j 1k k 3.j j k1. 4.kik j2. 27. 28. 3.5. 4.6. algebra system or a graphing utility to verify i 3k k 3i v j k v j k v j k v j k 27. uvv2.27. 28. uvv 28. 5. 6. kk 5. jiii 3. 6. kkk 4.jiii1.k j j i j kk j k 3. 4. 5jijj u1k 5j ijj u1kjkk i k j k 5. 6. j k v v 5. i k 6. k i 29. 30. uu j 3, 3, 2, 1 uu j 2, 2, 1, 29. vu 30. vu 3, 2, 2, 1, 0j0 28. u i k 21l k 1, 29. 30. v2,2, j1 11 k v u21, j 3i(c) ku yvv c) v. j2, 3.kand i ejercicios k i 7–10, ib) 5. Exercises 6.u vk3 29.u u4.5k3, 30.u u 527. k3, k 7 afind 5. 6. 29. 30. 2,k2, 1, j0 00l k En los 10, (a) calcular v, v 3 v. a) v In (b) u v, u, u v, v u, v. In Exercises 7–10, find (a) (b) and (c) In Exercises 7–10, find (a) (b) and (c) u v, v u, v v. v 1, 2, 3 v 1, 2, 0 v 1, 2, 3 v 1, 2, 0 v j k v j 29. uvv6.29. 30. uvv 30. 3, 1 2, 1 2,u 1, 1, 00l 1, 0 In Exercises 7–10, find (a) u v, (b) v u, 5. andi (c)kv v. 1,u2,2, i2,3 33l3, 2,02, v 5k1,k1, v 5 k21, 1, 2,2, u (a) v, u(b) vv, u,3i v (c) v. v v. In7. Exercises 7–10, find (a)find andu, (c)and u u 2i 4j 5k 8. u 2i 4j u 3i 5k 7. 8. v In Exercises 7–10, (b) 29.v 1, 30. u uthe 3, 1 the 2, v In 1,Exercises 2, 3 1, 2, 331 v that 2, points 0points 3i 5k 5k vExercises 1, 2, 2, 0are Area and 32, verify the Area In 31 and and 32, verify that are the 2i2i 4j4j 7.7.uu 8.8.uu 3i Área En los ejercicios 31v.y32, 32, verify verificar que lospoints puntos sonthe los Area In Exercises 31 that the are v, (b) vExercises u, and vand In Exercises 7–10, find (a) uArea (c) 3i 2j 5k 2i 3j 2k 3iu2i 2j 2j4j2i 5k 5k 4j 2i 3j 2k In 31 32, verify that the points are the 3i 5k 7. uvvv 7.3i 8. uvvv 8. v 1, 2, 3 v vertices of parallelogram, and find its area. 2k vertices of parallelogram, and find its its area. area. 5k vérticesInof deaaaun paralelogramo, y find calcular su área. vertices parallelogram, and v 3i 2j 5k v 2i2iu 3j3j3i 2k Area 31 and31 32, verify that the are theare the Area In Exercises and 32, verify thatpoints the points vertices ofu aExercises parallelogram, and find its area. uu 3i7, 7, 3, 22 5k uu 2i 3, 2, 22i 9. 10. 7, 3,2j 3, 2, 22k 9. vu 10. vu u 3j 4j2k 3i 5k 7.3, 8. 9. 10. 3, 2 2, 2 v 3i 2j 5k v 2i 3j vertices of a22parallelogram, and find its area. 31. A 0, 3, , B 1, 5, 5 , C 6, 9, 5 , D 5, 7, 2 7, 3, 2 3, 2, 2 9. u 10. u 31. A 0, 3, , B 1, 5, 5 , C 6, 9, 5 , D 5, 7, 2 vertices of a parallelogram, and find its area. Area In Exercises 31 and 32, verify that 31.AA0,0,3,v3,2 2, 2i , B1,1,5, ,2k C6,6,9,9,5 5, D , D5,5,7,7,2 2 1, 1, 55 1, 11 3i2 2j 5k 1, 1, 5,2, v5, 3j5,5 5, C 31. B 3, 1, 21,7, 9. uvvv 9. 7, 10. uvvv 10. 3, 1, 5 1, 5, 1 u 3, 2 u 3, 2, 2 vertices of a parallelogram, and find its area 32. AA 0, 2, 3, BB 6, 6, 5, C 7, 2, D 3, 6, v 1, 1, 5 v 1, 5, 1 32. A 2, 3,A3, 6, C 7, 2,D9, D 3, 6, 2444 31. 23,0, ,111B3, 5, 55,1, , C5, 9, 5 6, ,2, 7, 2 5, 7, 32. 2, ,,, 1, B 111,6,C ,5,, C 7, 222,5, ,5,, D 3, 6, 31. 22, ,5,B5, ,7,C ,3,D u 7, 3, 2 u 3, 2 9. 10. 32. A 2, 3, 1 , B 6, 1 2, 2 D 6, 4 v 1, 1, 5 v 1, 5, 1 v 1, 1, 5 v 1, 5, 1 vv and In Exercises 11–16, find and show that itit is orthogonal to In Exercises Exercises 11–16, and ushow show that is orthogonal orthogonal to En los ejercicios 11 find afind 16,uucalcular 3 vthat y probar que es orto11–16, to 31. A6,triangle 0, 3, triángulo 2 ,4Bwith 1, 5,the 5 , C 6, 9, 5 , D 5, 7, 2 32. 2,In 1ejercicios , B 6,33 5, 1 a5, ,find C 2, , D2,of 3,2área 4del A3, ,B 6, , C2area 7, ,D 3, 6, Area Exercises –36, the the ÁreaA 32. En los2, 33 36,7,1the calcular el con InIn Exercises find uu v vand show that itvitisisorthogonal Area In Exercises 33 –36, find the area of the triangle with the 1, 1, 5 to v Exercises 1, 5,3,1133 uutanto v. both and v.u como both and 11–16, Area In –36, find area of the triangle with the 1 area gonal a a v. u v. both and 11 Area In Exercises 33 –36, find the of the triangle with the u v In Exercises 11–16, find and show that it is orthogonal to 32. A 2, 3, 1 , B 6, 5, 1 , C 7, 2, 2 , D 3, u los vértices dados. (Sugerencia: u 3 v es el área del triánguv In Exercises 11–16, find and show that it is orthogonal to both u and v. 1 u given vertices. Hint: is area of the triangle having given vertices. vertices. Hint: isthe thearea areaofof ofthe thetriangle trianglewith having 2the 1 222–36, given Hint: is the area the triangle having uu 33 vvv–36, Area In Exercises 33 find the Area InHint: Exercises find theofarea of the triangle with the uboth v. and both and12, u 3, 0 u 1, 1, 2 11. 12. given vertices. is the area the triangle having u v u 12, 3, 0 u 1, 1, 2 11. 12. u v. lo que tiene u y v como lados adyacentes.) u v In Exercises 11–16, find and show that it is orthogonal to 2 1 and as adjacent sides. uu and 12, 3,3,0 0 1,2 2 11.uu 12, 12.uu andvertices. as adjacent adjacent sides. given Hint:sides. ofarea the of triangle having u v12 uis the vvvasas 1,1,1, 11. 12. Area In Exercises 33having –36, find the area of th vertices. is the the triangle v area 2Hint: u1, v. andAAvgiven adjacent sides. uu 2, 5, 000 vv both 0, 1, 00and 2, 5, 0, 1, 33. 0, 0, 0 , B 1, 0, 3 , C 3, 2, 3, u 1, 2 11. uvvv 11. 12, 12. 33. 0, 0, 0 , B 1, 0, 3 , C 3, 3, 2, 2, 000 1 2, 5, 0 v 0, 1, 0 u 12, 3, 0 u 1, 1, 2 12. 33. A 0, 0, 0 , B 1, 0, 3 , C and as adjacent sides. u v given vertices. Hint: v 2, 5, 0 v 0, 1, 0 2 u v is the area of t 33. A 0,u0,and 0 , vBas1,adjacent 0, 3 , C sides. 3, 2, 0 uu 2, 3, uu 11. 10, 0, 66 13. 14. 2, 3,01112, 5, 0 0, 13. vu 14. vu 34. AA 0, 2, 3, 44B,,,1,1, BB1,0, 0, 1, 22C,,, C C 1, 2, 00 u10,00, 12, 3, 0 u0, 3, 21, 2, 5, 0,v 10, 1, 34. 12. 2, 3, 0, 1, C 1, 2, 2, 3, 6 13. 14. 33. A 0 , 3 , 3, 2, 0 v 0, 1, 0 34. 2, 4 B 2 1, 2, 0 and as adjacent sides. u v 2, 3, 1 10, 0, 6 13. u 14. u 34. A 2,33. 3,A 40,, 0,B 00,, 1,B 21,, 0,C 3 , 1,C2, 03, 2, 0 1, 2, 5, 3, 1, 2,2, 5, 3,0,000610, 35. AA 2, 2, 7, BB00, 1, 5, C 4, 6, v 3, 2, 0, 5, 60 3, 111 3, 1 10, 13. uvvv 13. 2, 14. uvvv 14. 5, 35. A 2,v 3, 7, 4330,,,,1,B C 1, 4, 2, 6, 0 11 33. A 0, 0, 0 , B 1, 0, 3 , C 3, 2, 0 1, 2, 34. 25,0, ,88C,,, C u u 35. ,1,5,B5, v 1, 2, 1 v 5, 3, 0 35. A 2,34. 7,A7,32,3, B3, 41,1, 8 8, 1, C 24,,4,6,C6, 11,1 2, 0 15. 16. u i j k u i 6j 15. 16. u i j k u i 6j 36. A 1, 2, 0 , B 2, 1, 0 , C 0, 0, 0 u 2, 3, 1 u 10, 0, 6 13. 14. 1k 2, 1 0 3, 0 36. AA 35. 1, 2,7,0 ,3, B 1,5,0 8, C 0,4, 0,6,0 1 34. A 2, 3, 4 , B 0, 1, 2 , C 1, 2, 0 15.uvu i i1,vj j 2,k1, 16.uvu i i5,v6j6j3, 5, 35. 2, ,B B 32,1, ,CC 36. 0, 15. 16. 36. A 1,1,2,2,0A0, 2, B 7,2,2, 1,,1,0B0, ,C1, 0,5, 0,80,0,0C 4, 6, 1 2i kk vv i 2i 2i jj 1, k kk 2, 1 2iu j jjji kk 2i v v 5, 3, 0 15. uvvv 15.i2i 16. u 6j j v 35.bicycle A 2, by 7, applying 3una , Bfuerza 1, 36. 1, 2,A0 1, ,AB 1, 0frena , C 0, 6j 36. 0 2, ,niño B 2, 1,the 0 brakes ,0, C0 0, 0, Momento Un en una bicicleta aplicando 37. A v 2i j k j k v 16. 2iu ji k 37. Torque child applies on aa 5, 8 , C 4, 6, 1 Torque A2,child child applies the brakes on0aaa bicycle bicycle by applying applying 37. Torque A applies the brakes on by a 15. 16. u i j k u i 6j v About 2iv It jIt2i In k jExercises 2i vectors j 2i k juu and 37. Torque child applies a36. bicycle by Ael1,when 2, 0applying ,the B crank 2,a1,la0 , C 0, 0, 0 k vthe k vv dirigida Ahacia 20brakes libras sobre pedal cuando Think 17–20, use the downward force of 20 pounds on the pedal Think About In Exercises 17–20,v use use the vectors and downward forceabajo of 20 20dethe pounds onon the pedal when the crank u and Think About Exercises 17–20, vectors downward force of pounds on the the crank 37.downward Torque A childA applies the brakes on pedal apedal bicycle by the applying a Para pensar En losExercises ejercicios 17 a 20, los vectores uk the ythe 37.v Torque child applies the brakes on awhen bicycle by a v vv Think About ItIt InIn 17–20, useusar the force of 20 on the when crank vvectors 2i uj and 2iangle j with k pounds manivela forma un ángulo de 40° con la horizontal (vercrank la applying figushown in the figure to sketch a vector in the direction of makes a the horizontal (see figure). The is 40 shown in the figure to sketch a vector in the direction of makes a angle with the horizontal (see figure). The crank is 40 shownin inthe the figure topara sketch avector vector insistema the direction ofthe the makesadownward a4040angle anglewith with the horizontal (see figure). The crank is uofand v and v makes Think About It In to Exercises 17–20, use the vectors downward force of 20the pounds on the pedal when the crank u Think About It In Exercises 17–20, use the vectors mostrados en la figura dibujar en un dextrógiro un force of 20 pounds on the pedal when the crank 37. Torque A child applies the brakes on a bi shown figure sketch a in the direction horizontal (see figure). The crank is ra). La in manivela tienethe 6 torque pulgadas de longitud. Calcular el indicated cross product in right-handed system. inches length. Find at P. indicated cross cross product product in in aaa right-handed right-handed system. system. inches in length. length. Find Find the torque at at P. P. indicated 666inches inches in the torque shown incross the figure todel a vector in the direction ain40 angle with the horizontal The force crank iscrank shown in the figure to sketch a vector in the direction of the 17–20, vector en la dirección vectorial indicado. makes a vectors angle with the horizontal (see figure). Theof is 40Find u v at Think About It ofInthe Exercises use the and downward 20 pounds on the ped indicated product insketch aproducto right-handed system. 6makes length. torque P.(see figure). momento respecto a P.the z indicated in a right-handed system. inches in the length. Find the at P. atmakes indicated cross product in a right-handed system. 6 in inches in length. Find the torque P. shown in the figure to sketch a 6vector direction oftorque the a 40 angle with the horizontal (see zzcross product zz indicated cross product in a right-handed system. 6 inches in length. Find the torque at P. 66 z z || z y yy yy y 6 y 2 1 v 40° P F = 20 libras 60° 60° 2000 lb 2000 lb 60° 2000 lb 000 libras 60° 2 2000 60° lb 60° 2000 60° lb2000 lb 16 66 4 6 66 u 6 6 pulg 0. 6 5 4 3 2 1 v 00. 0. .1016.060. 16 1.f61p1i6 ft t6fetfftt 0. 16 ft 6 66555 vv 556444 445333 vvv 6 5 2 33422 v4 223111 3 11112 2 22 1 1 u 1 33 2 1 u1u uu 44 32 2 1 1 43 3 2 u 44 3 2 3 x4 4 || u y 6 17. 18. uu vv uu4 3 17. u 18. vvv u 17. 18. 17. 18. 17. 18. uu 3vvv vv 3uu Figure for 37 Figure for Figure for for 37 37 Figure for for 38 38 19. 20. vvv uu uu uu uu vv 19. u 17. 20. vu Figure Figure 17. 18. 19. 20. Figura Figura para 38 Figure forpara 37 37 Figure for 3838 19. 20. s2v su v3vvvdu 19. 20. v vd 3uuuu v uu 318. u Figure for Figure for 38 for 38. Torque Both the magnitude and the direction of the force on 38. 18. Torque Both the magnitude magnitude and and the direction direction of the the force force on on 17. uv uv to v 37uBoth 19. 20.algebra v u21–24, u 20. uusystem Figure for 37the Figure 38 19. v u use 38. Torque the of CAS In Exercises computer find uu vvv In Exercises Exercises 21–24, use aaa computer computer algebra system tovfind find u CAS In 38. Torque BothLa themagnitud magnitude and the direction of the the force on un CAS 21–24, use algebra system to Momento y la dirección de la fuerza sobre 38. a crankshaft change as the crankshaft rotates. Find torque a crankshaft change as the crankshaft rotates. Find the torque CAS In Figure for 37 Figure for Exercises 21–24, use a computer algebra system to find u v En los ejercicios 21 a 24, usar un sistema algebraico por compua crankshaft change as the crankshaft rotates. Find the torque 19. 20. v u u u v and a unit vector orthogonal to and u v. and aa unit unit vector vector orthogonal orthogonal to to uu and and v. v. 38.a Torque Both the magnitude and theCalcular direction the force on 38. Torque Both and theshown direction of the force on crankshaft change asthe the crankshaft rotates. Find the torque and cigüeñal cambian cuando éste gira. elof momento sobre CAS and In Exercises 21–24, useua3 computer algebra systemsystem to findto u find on the crankshaft using the position and data in the figure. on the crankshaft crankshaft using themagnitude position and data shown in the figure. CAS In Exercises 21–24, use a unit vector orthogonal and v. algebra tadora para encontrar vtoyaucomputer un vector unitario ortogonal a vu u v on the using the position and data shown in the figure. a crankshaft change as the crankshaft rotates. Find the torque a crankshaft change as theyand crankshaft rotates. Find thefitorque 38. shown Torque Both magnitude and the direc onelthe crankshaft using the position data in the figure. cigüeñal usando posición datos mostrados en the la au unit orthogonal to u22. and v. and 21. u 4, 3.5, 77 uuu 8, 6, 21. 22. 4, 3.5,vector 8, 6, 6, 444 21–24, use a computer and4, avector unit orthogonal to v. CAS In Exercises algebra system tolafind u56 v los 39. Optimization A force of pounds acts on the pipe wrench yand a v.u 39. on Optimization Ausing force ofposition 56the pounds acts ondata the shown pipe wrench 21. 22. 3.5, the crankshaft the and acts data shown in thewrench figure. 39. Optimization A force of 56 pounds on the pipe on the crankshaft using position and in the figure. a crankshaft change as the crankshaft rota gura. 21. 22. u 4, 3.5, 77 uu and8,8, 6, 4 A force pounds and v.in ushown the figure on the next page. 2.5, 9, 33 7 10, 12, 22 orthogonal39.to Optimization shown in the the figure figure onof the56 next page.acts on the pipe wrench 2.5, 9,4, 10, 12, 21. uvvv 21. 4, 22. uvvv 22. 10, 3.5, 8,a unit 6, 8, 4vector shown in on the next page. 2.5, 9, 3 12, 2 on the crankshaft using the position and data 39. Optimization A force of 56 pounds acts the pipe wrench u 3.5, 7 u 6, 4 39. Optimization A force of 56 pounds acts on the pipe wrench shown in the figure on the next page. 39. Optimización Una fuerza de 56 libras actúa sobre la llave inglev 2.5, 9, 3 v 10, 12, 2 (a) Find the magnitude of the moment about by evaluating O 23. 24. uu 3i 2j 5k uu 21. 0.7k (a) Find Find the8,magnitude magnitude ofon thethe moment about O by evaluating evaluating O by 23. vu 24. vu 3i 9, 32j 2j 9,5k 5k 0.7k shown in the the figure the next page. 22. 3.5, 72 u 6,figura 4on 2.5, 10, (a) of the moment about shown inlathe figure next page. 23. 24. 0.7k 39. A force of 56 pounds acts sa Find mostrada en que semoment encuentra enOptimization laOpágina siguiente. v u 12, 10,4, 212, (a) the F magnitude the about bythe evaluating 23. 24. u 3iv3i 2j2.5, 5k3 u 0.7k OA Use aa of graphing utility to graph resulting .. Use OA Use graphing utility to graph the resulting F v 0.4i 0.8j 0.2k v 1.5i 6.2k OA a graphing utility to graph the resulting F . 0.4i 0.8j 0.2k v 1.5i 6.2k shown in the figure on the next page. (a) Find the magnitude of the moment about by evaluating O v 2.5, 9, 3 v 10, 12, 2 23. uvv 23.0.4i 24. 3i 2j 5k 0.7k u (a) Find the magnitude of the moment about by evaluating O 0.8j 0.2k v 1.5i 6.2k a) Calcular la magnitud del momento respecto a O evaluando OA a graphing utility to graph the resulting F .of 2j 5k 0.7k function function ofUse v 0.4iu 0.8j3i 0.2k v 24. 1.5iu 6.2k ... F .auna function of OA Use graphing utility to graph the resulting F . Use a graphing utility to graph the resulting OA Usar herramienta de graficación para reprei OA 3 F i. (a) Find the magnitude of the moment abo . function of 23. 24. u 3i 2j 5k u 0.7k vu and1.5i vProgramming 0.4i 0.8j Given 0.2kthe0.2k 6.2k 6.2kform, v 0.4i 0.8j 1.5i 25. vectors in component (b) Use the result of part (a) to determine the magnitude of the u and 25. Programming Programming Given the vectors vectors u and vvv in in component component form, (b) function Use the the result of part (a) to to determine determine the the magnitude magnitude of of the the of . of 25. Given the form, (b) Use result part (a) function of . sentar la función de q que se obtiene. Use a graphing utility to OA F . u and vin 25. Programming Given vectors utility form,is (b) Use the1.5i result of part 45 (a) ..to determine the magnitude of the vcomponent 0.4i 0.8j vmoment 6.2k write program for graphing which the output moment when write aaa program program for aaathe graphing utility ininwhich which the output output is0.2k 45 when write for graphing utility in the is 45 . moment when Programación Dadas las componentes de los vectores u y v, 25. function of . u v 25.write Programming Given the vectors and in component form, (b) Use the result of part (a) to determine the magnitude of the b) Usar el resultado del inciso a) para determinar la magnitud u v 25. Programming Given the vectors and in component form, (b) Use the result of part (a) to determine the magnitude of the program 45 . moment when and uu vvav and uu for vv ... a graphing utility in which the output is and u (c) Use the result of part (a) to determine the angle when the (c) del Usemomento the result of part (a) to45 determine the angle angle when when the the u unuprograma de graficación que write awrite program apara graphing utility25. in which the output is 45(a) . to moment when (c) Use the result of part determine the cuando a program forherramienta a graphing utility in which thecaloutput is vectors when . u and vmoment Programming Given the in component (b) Use the result uescribir v and v v.for (c) Use the result of part (a)form, to determine the angle when theof part (a) to determine t 26. Programming Use the program you wrote in Exercise 25 to magnitude of the moment is maximum. Is the answer what 26. Programming Use the program you wrote in Exercise 25 to magnitude of the moment is maximum. Is the answer what cule y u 3 v iu 3 vi. and u v u v . 26.Programming Programming Use youwrote wrote inExercise Exercise 25 for to a graphing magnitude ofthe the moment maximum. the answer what u v andUse u the vprogram .programyou c) utility Usar el resultado del inciso a) para determinar elangle ángulo write a program inUse which the output moment when 45 . (c) Use result of part (a) to determine the angle when the (c)the result of part (a) the when the 26. magnitude ofthe moment isismaximum. IsIsthe answer what find and for and uu vvv and uu the vv for uu 2, 6, 10 vv 3, 8, 55 ... you expected? Why or why not? find u and u for u and 2, 6, 6, 10 10 in 3,25 8, to you expected? Why or why not?to determine find and v 2, v 3, 8, 5 you expected? Why or why not? 26. Programación Usar el programa escrito en el ejercicio 25 para cuando la magnitud del momento es máxima. ¿Es la respuesand u v u v . 26.find Programming Use the program you wrote in Exercise 25 to magnitude of the moment is maximum. Is the answer what 26. Programming Use the program you wrote in Exercise 25 to magnitude of the moment is maximum. Is the answer what (c) Use the result of part (a) to determine t u v and u v for u 2, 6, 10 and v 3, 8, 5 . you expected? Why or why not? encontrar yvv and vi u 5u 2, k22, 6,2,Programming 10l 5 k3, 5l. lo expected? que seexpected? ¿Por qué sí onot? por quémagnitude no? find u find forpara and vu and vu uv for 6,26. 10 3,v 8,8,5Use . 8,the you Why orWhy whyto not? and3 u3 v yvuiu 6, 10 3, 5 .program ta you or why you wrote inesperaba? Exercise 25 of the moment is maximum find u v and u v for u 2, 6, 10 and v 3, 8, 5 . you expected? Why or why not? \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ 1053714_1104.qxp 1053714_1104.qxp 10/27/08 10/27/08 11:46 11:46 AM AM Page Page 799 799 Larson-11-04.qxd 3/12/09 17:20 Page 799 1053714_1104.qxp 10/27/08 11:46 AM Page 799 1053714_1104.qxp 10/27/08 11:46 AM Page 799 SECCIÓN 11.411.4 vectorial deofof dos vectores enin el espacio The Product Two Vectors 11.4El producto TheCross Cross Product Two Vectors inSpace Space 799 799 The Cross Product of Two Vectors in Space 799 11.4 The Cross Product of Two Vectors in Space 799 Volume 47 ofof the Volume In In Exercises 47 and andy 48, 48, find find the the volume volume the Volumen EnExercises los ejercicios 47 encontrar el volumen del 180 lb 180 lb 180 libras F FF parallelepiped the vertices. parallelepipedwith withtiene thegiven given vertices. paralelepípedo que vértices dados (ver las figuras). Volume In Exercises 47 and 48, find the volume of the B BB θ θθ 180 lb F Volume In Exercises 47 and 48, find the volume of the 180 lb AAA F parallelepiped 47. 0,0,00,the 5,5,11, ,vertices. 2,2,0,0,55 47. 0,0,0,0,00, , 3,3,with , 0,0,given θ parallelepiped with the given vertices. 18 in. 18 in. B 18 pulg θ B A 47. 3, 0,3,5, 0,5,101,, , 5, 3,5,0, 0,0,505,, , 2, 0,2,5, 5,5,616,, , 5, 2,5,5, 0,5,656 12 12in. in.A θθθ FFF 12 pulg 47. 0, 0, 0 , 3, 0, 0 , 0, 5, 1 , 2, 0, 5 18 in. 48. 48. 0, 3,0, 18 in. 3,0,0, 5,0,010,,, 0, 5,0,4, 0,4,050,,, 2, 3, 5, 60,0, 0,5,, 5,1,61,1,1,55 θ F 3, 5, 1 , 5, 0, 5 , 2, 5, 6 , 5, 5, 6 12 in. 30° 30° 30° θ F 3, 4, 0 , 1, 5, 5 , , , 1,4, 3, 4, 0 , 1, 5, 5 , 12 in. 48. 0, 0, 0 , 0, 4, 0 , 3, 0,4,04,1, ,1,551, 54,5,5,55 48. 0, 0, 0 , 0, 4, 0 , 3, 0, 0 , 1, 1, 5 A A A 15 in. 15 in. 15 pulg OOO 30° 5, 5vv, 0,0, 4, 1,what 5what , can 4, 5, 5concluir IfIfu3, about 49. Si yuu you conclude about u 4,vv0 , 00 y1, 49. puede 30° 3, 4, 0 ,¿qué 1,se5,can 5 ,you 4,conclude 1, 5 , acerca 4, 5,de5uu O A 15 in. v? and v? and y v? Figure for 39 Figure for 40 Figure for 39 Figure for 40 O 15 in. 49. If uA v Figura para 39 Figura para 40 0 y u v 0, what can you conclude about u 49. If u that whatreasoning. can you conclude about u vthatare 0 yequal. u vExplain 0, your 50. Identify the dot products 50. Identificar Identify the dot products are equal. your reasoning. 50. los productos vectoriales que Explain son iguales. Explicar el and v? 40. Optimization AA force ofof 180 pounds bracket 40.Optimización Optimization force 180Figure pounds acts on the the bracket Figure for 39 foracts 40 on and v? nonzero Una fuerza el soporte 40. u, v, w (Assume and are vectors.) u, v, w (Assume and are nonzero vectors.) Figure for 39de 180 libras actúa sobre Figure for 40 razonamiento. (Suponer que u, v y w son vectores distintos de shown in the figure. shown in the figure. 50. Identify the dot products that are equal. Explain your reasoning. en la figura. Identify the dot products 40. mostrado Optimization A force of 180 pounds acts on the bracket ww50. vv ww that uu are equal. Explain your reasoning. b)b) vectors.) a) uu vvu, v, cero.) (Assume and w are nonzero 40. Optimization Atheforce ofFFrepresenting 180 pounds the acts on the a) bracket AB (a) Determine the vector and the vector AB (a) Determine the vector and vector representing the (Assume u, v, and w are nonzero vectors.) a)shown Determinar el vector AB y el vector F que representa la in the figure. ww c) d) c) uuu vvv w d) uvu w ww u vv shown in the figure. force. (F will terms ofofde .).) force.(F (Festará willbe be terms a) b) eninin términos u.) vector F representing the a) u v w b) v w u AB and (a)fuerza. Determine the vector the u w v e) f u w v e) f)) ww ABAAand (a) Determine the vector the vector F representing Find ofofthe about evaluating (b) Findthe the magnitude the moment about by evaluating c) uthe v w d) u vv wuu v b)(b) Calcular magnitud del momento aby A evaluando force. (Flamagnitude will be in terms ofmoment .) respecto c) u v w d) u w v force. (F will be in terms of .) g) h) AB FF . . AB F i. e)g) u uuw vvv ww fh) ) www vuu uvv (b)i AB Find3 the magnitude of the moment about A by evaluating e) f ) u w v w v u (b)part Find the magnitude of magnitude the momentofofabout Use result (b) totob) determine the the (c) Use the result part (b) determine the magnitude the A by evaluating c)(c) Usar resultado inciso para determinar la magnitud g) h) ABelthe F . ofofdel u vABBOOw w u v W R I T I N G A U T C O N C E P T S W R I T I N G U T C O N C E P T S g) h) w u v AB F . u v w 30 moment when 305. . 308. moment when momento cuando (c)delUse the result of partu (b) to determine the magnitude of the 51. Define the cross product of vectors and u v. 51. Define the cross product of vectors and u v. (c) Use the result of part (b) to determine the magnitude of the WRITING ABOUT CONCEPTS Use result part (b) determine the (d) Useelthe the resultofofdel part (b) determine theangle angleel when whenthe the d)(d) Usar resultado inciso para determinar ángulo u 30 . totob) moment when W Rconceptos I Tproperties I N G A B of OofUthe T cross C O Nproduct. CEPTS Desarrollo de 30At . that moment 52. 52. State Statethe the geometric properties the magnitude ofofthe iswhen angle, what magnitude themoment moment ismaximum. maximum. At that angle, what 51. Define thegeometric cross product of vectors and v.product. u cross cuando la magnitud del momento es máxima. A ese ángulo, (d) Use the result of part (b) to determine the angle when the 51. Define the cross product of vectors u and v. ??Is isisthe between the and AB the relationship between thevectors vectors and itwhat what (d) entre Use the result of part to determine the when 53. If magnitudes two are doubled, 53.Definir Ifthe thethe magnitudes twovectors vectors are doubled, how willthe the ¿cuál esrelationship la relación losis vectores F yFF(b) ¿Es loIsitque se angle 51. AB ?AB u yhow v. will el geometric productoofof vectorial deoflos vectores 52. State properties the cross product. magnitude of the moment maximum. At that angle, what you Why oror why not? 52.cross State the geometric properties ofExplain. the cross product. youexpected? expected? Why why not? magnitude of the moment is maximum. At that angle,magnitude what of the product of the vectors change? magnitude of the cross product of the vectors change? Explain. esperaba? ¿Por qué sí o por qué no? is the relationship between the vectors F and AB ? Is it what 52. Dar lasmagnitudes propiedadesofgeométricas the two vectorsdel areproducto doubled, vectorial. how will the F and AB ?53. is the relationship between the vectors Is itIfwhat Use aa herramienta graphing utility totonot? graph the function for the 53. If the magnitudes of two vectors are doubled, how will the (e) Useuna graphing utility graphpara therepresentar function forfunthe e)(e) Usar de graficación la you expected? Why or why magnitude of the cross product of the vectors change? Explain. 53. Si las magnitudes de dos vectores se duplican, se change? Explain. you expected? not? AAWhy magnitude ofofthe about for magnitude of the cross product of¿cómo the vectors 180£. .Find magnitude themoment moment aboutrespecto for00orawhy Find magnitud del momento A para180 0° £ (e)ción Usede ala graphing utility to graph the function for qthe modificará la magnitud del producto vectorial de los vecthe function iningraphing the domain. the thezero zeroofofelthe the function thegiven given domain. Interpret the functionCCAfor TTOONNEE APPSSthe (e) Use toInterpret graphInterthe 180°. Hallar de la afunción enfor elutility 0dominio dado. 180 . Find magnitude of cero the moment about A tores? Explicar. meaning of the zero in the context of the problem. meaning of the zero in the context of the problem. A 0 180 . magnitude of the moment about for Find pretar el significado del cero contexto del problema. 54. 54. The triangleininspace spaceare are xx1,1,yy1,1,zz11, , xx2,2,yy2,2,zz22, , the zero of the function in en theelgiven domain. Interpret the C A PThe Sthe T vertices Overtices N E ofofaatriangle the zero of the function in the given domain. Interpret P S T Ohow Nhow E totofind and xx3,3,yy3,3,zz33C. .A Explain and Explain findaavector vectorperpendicular perpendicular meaning of the zero in the context of the problem. In u vv wof w. the . zero in the context of the problem.54. The vertices of a triangle in space are x1, y1, z1 , x2, y2, z2 , InExercises Exercises41– 41–44, 44,find findumeaning Para discusión to the triangle. to the triangle. 54. The vertices of a triangle in space are x1, y1, z1 , x2, y2, z2 , En los ejercicios 41 a 44, calcular u ? xv 3 wc. and x3, y3, z3 . Explain how to find a vector perpendicular w In and x Explain how to find vector perpendicular , y , z . uu i i 41– 44, find u v 42. 41. 41.Exercises 42.. uu 1,1,1,1,11 3 3 en 3 el espacio son sx , y a 54. Los vértices de un triángulo to the triangle. u 1, 1l v w. In Exercises 41– 1 1, z1d, 41. u 5 i 42.44,u find 5 k1, to the triangle. sx2, y2, z2d,y sx3, y3, z3d. Explicar cómo encontrar un vector 1,2,1,1, 1,1,0l010 41. vvuv5 j jij 42. vvuv5 k2,2, 1, 1, 1 41. u i 42. u True or True perpendicular or False? False? In In Exercises 55–58, 55–58, determine determine whether whether the the al Exercises triángulo. w k w 0, 0, 1 w k w 0, 0, 1 2,0, 1,1l 0 wv 5 kj wv 5 k0, statement statementisistrue trueor orfalse. false.IfIfititisisfalse, false,explain explainwhy whyor orgive givean an v j v 2, 1, 0 43. 44. 43. uwu k2,2,0,0,11 44. uwu 2,0, 2,0,0, 0,010 True or False? In Exercises 55–58, determine whether the example that shows it is false. example that shows it is false. True or False? In Exercises 55–58, determine whether the 43. u 5 k2, 0, 1l 44. u 5 k2, 0, 0l falso? En losIf ejercicios a 58, determinar la w k w 0, 0, 1 ¿Verdadero statement iso true or false. it is false,55 explain why or givesian statement is true or false. If it is false, explain why or give an 43. vvuv5 k0,0, 44. vvuv5 k1,1, 2,0,3,3, 0,3,0l010 2,1,1,1, 0,1,1l101 declaración esshows verdadera othe falsa. Siproduct es falsa,ofof explicar por qué example is false. 55. possible totoitfind the cross two inin aoa 43. u 44. u 2, 0, 1 2, 0, 0 55. ItIt isis that possible find cross product two vectors vectors w 0, 0, 1 w 0, 2, 2 example that shows it is false. w 0, 0, 1 w 0, 2, 2 dar un ejemplo que demuestre que es falsa. 0,0, 3,1l 0 v 1, 1, 1 two-dimensional two-dimensionalcoordinate coordinatesystem. system. wv 5 k0, v 0, 3, 0 w 5 k0, 2, 2l v 1, 1, 1 55. It is possible to find the cross product of two vectors in a 55. Es posible encontrar el producto vectorial de dos vectores en of un two vectors in a w 0, 0, 1 w 0, 2, 2 55. It is possible toare find the cross product ininspace that nonzero and nonparallel, Volume 56. If Ifuuand andvvare arevectors vectors space that are nonzero and nonparallel, Volume In InExercises Exercisesw45 45and and 46,1use usethe thetriple triplescalar scalarproduct product 0, 46, 0, w 0,toto 2, 2 56. two-dimensional coordinate system. sistema de coordenadas bidimensional. two-dimensional coordinate system. u v v u. then find the volume of the parallelepiped having adjacent edges u, u v v u. then find the volume of the parallelepiped having adjacent edges u, Volumen En los ejercicios 45 y 46, usar el triple producto 56. If u and v are vectors in space that are nonzero and nonparallel, Volume In Exercises 45 and 46, use the triple scalar product to v,v,and andw. w. encontrar escalar para el volumen del paralelepípedo tiene scalar56. 56. vIfv u en andelvespacio arethen vectors that are Volume In Exercises 45 and 46, use que the triple product vectores son distintos de nonzero cero y and nonparallel, vque w. 57. If and w, v in w.space 57. Si Ifuuu yutov00son then vanduu v u. uu w, then find the volume of the parallelepiped having adjacent edges u, como aristas adyacentes u, volume v y w. of the parallelepiped having adjacent edges then u v v u. find the u, no paralelos, entonces uu u vv vuu w, 58. u vvv uuw. w, w,then w. 58. If and thenvv w. and v,45. 45. 46. uu w.i i jj 46. uu 1,1,3,3,11 00,and uw,and w,uthen 57. IfIfuuu 0, v, and w. 0 u v u w, v w. 57. If and then 57. Si y entonces u Þ 0 u 3 v 5 u 3 w, v 5 w. 45. uvv5 i j1 46. uvv5 k1,0,0,3,6,6,1l66 j k u v prove u w,the u v ofof uthe v w. 58. If u 0,59 and thenproduct. 45. u ij k 46. u j 1, 3, 1 In property cross InExercises Exercises 59–66, –66, prove the property thew, cross product. u 0, u v u w, u v u w, then v w. 58. If and 58. Si y entonces u Þ 0, u v 5 u w, u 3 v 5 u 3 v 5 w. ? ? 45. 46. u i j u 1, 3, 1 vww 5j1k vww 5 k0, 6,4,4, 6l v ji i kkk v 0, 6, 60,0, 44 In the property of the crossdel product. uu ejercicios vv 59 ww–66, u uu ww propiedad 59. v j k 0, 6, 6 u66,vvdemostrar 59.Exercises En los 59 aprove producto w 5 i 1 zkz w 5 zk24, 0, 24l v In Exercises 59 –66, la prove the property of the cross product. w i k w z 4, 0, 4 vectorial. c u v cu v u cv 60. w i k w 4, 0, 4 c u v cu v u cv 60. v w u v u w 59. u z z v w u v u w 59. u z z 66 61. 0 d cu 61. uucu3 vv 22 z z 59. 5 su 3v vd 1 3 wd u suvuv1 0w u su cv 60. c u v cu v u cv 60. 644 v 2 vvvd 5 w 62. u v v5 v uww 62. cuuu 6 su 3u 3 scvd 60. 0w scud u3 61. v 2 6 2 61. u u 0 4 2 vv v 63. u v is orthogonal 2 uu 4 63. uuu3 uvv5is w both andv.v. ww 0orthogonal 61. u to vtoboth w uuand 62. 4 v u v w 62. u v w y y u 2 4 4 v 6 6 u v 0 u 64. if and only if and are u v 0 u 64. if and only if and arescalar scalarmultiples multiplesofofeach each 88 2 w u yy d 5 su 3 to vd both w u andvvv. 62. 63. uu ? sv 3 is w orthogonal ? v 1w 1 uu u y w w 22 w u v u v. 63. is orthogonal to both and 4 other. 6 other. 8 y 22 y 6 8 tantoifauu and como a v. scalar multiples of each 63. 0 if and only v are 64. uu y3 vv es ortogonal 1 x4 u w 2 y 4 6 65. uorthogonal. ififuand only if orthogonal. and v are scalar multiples of each 865. Prove u vvare uand Provethat that uu 64.vv u uvu v0v if and are wy 2 1 2xx 1 u w 64. uother. si u y v son múltiplos escalares uno del otro. 3 v 5 0 si y sóloother. 2 2 x 2 vvv wwu vuuif w vv uu vorthogonal. 66. v w. w. 66. Prove Provethat thatuu u iu uwand 65. Prove that x 65. Demostrar que siv u vy are vusonvortogonales. vi 5that iui uivi 65. 3 Prove if u and v are orthogonal. x v11.9. w v wd v u2 svu w. 66. Prove that u 66. que66. u11.9. 3Prove svw 3 that wd u5 s u 67. Prove ? ? 67. Demostrar ProveTheorem Theorem v w u vdww.v u v w. u 11.4 \\ \ \ \ \\ \ \ \ \\ \ \ \ 67. el teorema 67. Demostrar Prove Theorem 11.9. 11.9. 67. Prove Theorem 11.9. Larson-11-05.qxd 800 3/12/09 17:27 CAPÍTULO 11 Page 800 Vectores y la geometría del espacio 11.5 Rectas y planos en el espacio n n n n Dar un conjunto de ecuaciones paramétricas para una recta en el espacio. Dar una ecuación lineal para representar un plano en el espacio. Dibujar el plano dado por una ecuación lineal. Hallar las distancias entre puntos, planos y rectas en el espacio. Rectas en el espacio En el plano se usa la pendiente para determinar una ecuación de una recta. En el espacio es más conveniente usar vectores para determinar la ecuación de una recta. En la figura 11.43 se considera la recta L a través del punto Psx1, y1, z1d y paralela al vector v 5 ka, b, cl. El vector v es un vector de dirección o director de la recta L, y a, b y c son los números de dirección (o directores). Una manera de describir la recta L es decir que consta de todos los puntos Qsx, y, zd para los que el vector PQ es paralelo a v. Esto significa que PQ es un múltiplo escalar de v, y se puede escribir a PQ 5 t v, donde t es un escalar (un número real). z Q(x, y, z) L P(x1, y1, z1) \ v = ⟨a, b, c⟩ \ y \ \ PQ 5 kx 2 x1, y 2 y1, z 2 z1 l 5 kat, bt, ctl 5 t v PQ = tv Igualando los componentes correspondientes, se obtienen las ecuaciones paramétricas de una recta en el espacio. x La recta L y su vector de dirección v TEOREMA 11.11 ECUACIONES PARAMÉTRICAS DE UNA RECTA EN EL ESPACIO Figura 11.43 Una recta L paralela al vector v 5 ka, b, cl y que pasa por el punto Psx1, y1, z1d se representa por medio de las ecuaciones paramétricas x 5 x1 1 at, z 5 z1 1 ct. Si todos los números directores a, b y c son distintos de cero, se puede eliminar el parámetro t para obtener las ecuaciones simétricas (o cartesianas) de la recta. z (1, −2, 4) x 2 x1 y 2 y1 z 2 z1 5 5 a b c 4 −4 2 −4 y 5 y1 1 bt, y Ecuaciones simétricas. −2 EJEMPLO 1 2 2 4 x 4 L y Hallar las ecuaciones paramétricas y simétricas Hallar las ecuaciones paramétricas y simétricas de la recta L que pasa por el punto s1, 22, 4d y es paralela a v 5 k2, 4, 24l. Solución Para hallar un conjunto de ecuaciones paramétricas de la recta, se usan las coordenadas x1 5 1, y1 5 22,y z1 5 4, y los números de dirección a 5 2, b 5 4 y c 5 24 (ver figura 11.44). v = ⟨2, 4, −4⟩ x 5 1 1 2t, y 5 22 1 4t, z 5 4 2 4t Ecuaciones paramétricas. Como a, b y c son todos diferentes de cero, un conjunto de ecuaciones simétricas es El vector v es paralelo a la recta L Figura 11.44 x21 y12 z24 5 5 . 2 4 24 Ecuaciones simétricas. Larson-11-05.qxd 3/12/09 17:27 Page 801 SECCIÓN 11.5 Rectas y planos en el espacio 801 Ni las ecuaciones paramétricas ni las ecuaciones simétricas de una recta dada son únicas. Así, en el ejemplo 1, tomando t = 1 en las ecuaciones paramétricas se obtiene el punto (3, 2, 0). Usando este punto con los números de dirección a 5 2, b 5 4 y c 5 24 se obtiene un conjunto diferente de ecuaciones paramétricas x 5 3 1 2t, y 5 2 1 4t, y z 5 24t. Ecuaciones paramétricas de una recta que pasa por dos puntos EJEMPLO 2 Hallar un conjunto de ecuaciones paramétricas de la recta que pasa por los puntos s22, 1, 0d y s1, 3, 5d. Solución Se empieza por usar los puntos Ps22, 1, 0d y Qs1, 3, 5d para hallar un vector de dirección de la recta que pasa por P y Q, dado por v 5 PQ 5 k1 2 s22d, 3 2 1, 5 2 0l 5 k3, 2, 5l 5 ka, b, cl. \ Usando los números de dirección a 5 3, b 5 2 y c 5 5 junto con el punto Ps22, 1, 0d, se obtienen las ecuaciones paramétricas z x 5 22 1 3t, n Q Planos en el espacio y n · PQ = 0 x El vector normal n es ortogonal a todo vector PQ en el plano Figura 11.45 z 5 5t. NOTA Como t varía sobre todos los números reales, las ecuaciones paramétricas del ejemplo 2 determinan los puntos (x, y, z) sobre la recta. En particular, hay que observar que t 5 0 y t 5 1 dan los puntos originales s22, 1, 0d ys1, 3, 5d. n P \ y 5 1 1 2t, y Se ha visto cómo se puede obtener una ecuación de una recta en el espacio a partir de un punto sobre la recta y un vector paralelo a ella. Ahora se verá que una ecuación de un plano en el espacio se puede obtener a partir de un punto en el plano y de un vector normal (perpendicular) al plano. Considerar el plano que contiene el punto Psx1, y1, z1d y que tiene un vector normal distinto de cero n 5 ka, b, cl, como se muestra en la figura 11.45. Este plano consta de todos los puntos Qsx, y, zd para los cuales el vector PQ es ortogonal a n. Usando el producto vectorial, se puede escribir \ n ? PQ 5 0 kx 2 x1, y 2 y1, z 2 z1l 5 0 \ ka, b, cl ? asx 2 x1d 1 bs y 2 y1d 1 csz 2 z1d 5 0 La tercera ecuación del plano se dice que está en forma canónica o estándar. TEOREMA 11.12 ECUACIÓN CANÓNICA O ESTÁNDAR DE UN PLANO EN EL ESPACIO El plano que contiene el punto sx1, y1, z1d y tiene un vector normal n 5 ka, b, cl puede representarse en forma canónica o estándar, por medio de la ecuación asx 2 x1d 1 bs y 2 y1d 1 csz 2 z1d 5 0. Reagrupando términos, se obtiene la forma general de la ecuación de un plano en el espacio. ax 1 by 1 cz 1 d 5 0 Forma general de la ecuación de un plano en el espacio. Larson-11-05.qxd 802 3/12/09 17:27 CAPÍTULO 11 Page 802 Vectores y la geometría del espacio Dada la forma general de la ecuación de un plano, es fácil hallar un vector normal al plano. Simplemente se usan los coeficientes de x, y y z para escribir n 5 ka, b, cl. EJEMPLO 3 Hallar una ecuación de un plano en el espacio tridimensional Hallar la ecuación general del plano que contiene a los puntos s2, 1, 1d, (0, 4, 1) y s22, 1, 4d. z (−2, 1, 4) Solución Para aplicar el teorema 11.12 se necesita un punto en el plano y un vector que sea normal al plano. Hay tres opciones para el punto, pero no se da ningún vector normal. Para obtener un vector normal, se usa el producto vectorial de los vectores u y v que van del punto (2, 1, 1) a los puntos (0, 4, 1) y (22, 1, 4), como se muestra en la figura 11.46. Los vectores u y v dados mediante sus componentes son 5 4 v 3 −3 2 −2 u 5 k0 2 2, 4 2 1, 1 2 1l 5 k22, 3, 0l 1 (2, 1, 1) 3 x v 5 k22 2 2, 1 2 1, 4 2 1l 5 k24, 0, 3l (0, 4, 1) u 2 2 4 así que 5 Un plano determinado por u y v y | n5u3v i 5 22 24 Figura 11.46 j 3 0 | k 0 3 5 9i 1 6j 1 12k 5 ka, b, cl es normal al plano dado. Usando los números de dirección para n y el punto sx1, y1, z1d 5 s2, 1, 1d, se puede determinar que una ecuación del plano es asx 2 x1d 1 bs y 2 y1d 1 csz 2 z1d 5 0 9sx 2 2d 1 6s y 2 1d 1 12sz 2 1d 5 0 9x 1 6y 1 12z 2 36 5 0 3x 1 2y 1 4z 2 12 5 0. Forma canónica o estándar. Forma general. Forma general simplificada. NOTA En el ejemplo 3, verificar que cada uno de los tres puntos originales satisfacen la ecuación n 3x 1 2y 1 4z 2 12 5 0. n1 θ Dos planos distintos en el espacio tridimensional o son paralelos o se cortan en una recta. Si se cortan, se puede determinar el ángulo s0 ≤ u ≤ py2d entre ellos a partir del ángulo entre sus vectores normales, como se muestra en la figura 11.47. Específicamente, si los vectores n1 y n2 son normales a dos planos que se cortan, el ángulo q entre los vectores normales es igual al ángulo entre los dos planos y está dado por n2 cos u 5 θ | | n1 ? n2 . in1 i i n2 i Ángulo entre dos planos. Por consiguiente, dos planos con vectores normales n1 y n2 son ? n2 5 0. Ángulo q entre dos planos 1. perpendiculares si n1 Figura 11.47 2. paralelos si n1 es un múltiplo escalar de n2. Larson-11-05.qxd 3/12/09 17:27 Page 803 SECCIÓN 11.5 Hallar el ángulo entre los dos planos dados por Plano 1 x 2 2y 1 z 5 0 Ecuación de plano 1. 2x 1 3y 2 2z 5 0 Ecuación de plano 2. Plano 2 θ 803 Hallar la recta de intersección de dos planos EJEMPLO 4 z Recta de intersección Rectas y planos en el espacio y y hallar las ecuaciones paramétricas de su recta de intersección (ver figura 11.48). x Solución Los vectores normales a los planos son n1 5 k1, 22, 1l y n2 5 k2, 3, 22l. Por consiguiente, el ángulo entre los dos planos está determinado como sigue. cos u 5 5 Figura 11.48 5 |n1 ? n2| Coseno del ángulo entre n1 y n2. in1 i i n2 i |26| !6 !17 6 !102 < 0.59409 Esto implica que el ángulo entre los dos planos es u < 53.558. La recta de intersección de los dos planos se puede hallar resolviendo simultáneamente las dos ecuaciones lineales que representan a los planos. Una manera de hacer esto es multiplicar la primera ecuación por 22 y sumar el resultado a la segunda ecuación. x 2 2y 1 z 5 0 22x 1 4y 2 2z 5 0 2x 1 3y 2 2z 5 0 2x 1 3y 2 2z 5 0 7y 2 4z 5 0 y5 4z 7 Sustituyendo y 5 4zy7 en una de las ecuaciones originales, se determina que x 5 zy7. Finalmente, haciendo t 5 zy7, se obtienen las ecuaciones paramétricas x 5 t, y 5 4t, y z 5 7t Recta de intersección. lo cual indica que 1, 4 y 7 son los números de dirección de la recta de intersección. Hay que observar que los números de dirección del ejemplo 4 se pueden obtener a partir del producto vectorial de los dos vectores normales como sigue. n1 3 | | i n2 5 1 2 5 | 22 3 j 22 3 k 1 22 | | | | | 1 1 i2 22 2 1 1 j1 22 2 22 k 3 5 i 1 4j 1 7k Esto significa que la recta de intersección de los dos planos es paralela al producto vectorial de sus vectores normales. Larson-11-05.qxd 804 3/12/09 17:27 CAPÍTULO 11 Page 804 Vectores y la geometría del espacio Trazado de planos en el espacio Si un plano en el espacio corta uno de los planos coordenados, a la recta de intersección se le llama la traza del plano dado en el plano coordenado. Para dibujar un plano en el espacio, es útil hallar sus puntos de intersección con los ejes coordenados y sus trazas en los planos coordenados. Por ejemplo, considerar el plano dado por 3x 1 2y 1 4z 5 12. Ecuación del plano. Se puede hallar la traza xy, haciendo z 5 0 y dibujando la recta 3x 1 2y 5 12 Traza xy- en el plano xy. Esta recta corta el eje x en (4, 0, 0) y el eje y en (0, 6, 0). En la figura 11.49 se continúa con este proceso encontrando la traza yz y la traza xz, y sombreando la región triangular que se encuentra en el primer octante. z z z (0, 0, 3) (0, 0, 3) (0, 6, 0) (0, 6, 0) (0, 6, 0) y y y (4, 0, 0) (4, 0, 0) (4, 0, 0) x x x traza xy sz 5 0d: traza yz sx 5 0d: 3x 1 2y 5 12 2y 1 4z 5 12 Trazas del plano 3x 1 2y 1 4z 5 12 traza xz s y 5 0d: 3x 1 4z 5 12 Figura 11.49 z Plano: 2x + z = 1 Si en una ecuación de un plano está ausente una variable, como en la ecuación 2x 1 z 5 1, el plano debe ser paralelo al eje correspondiente a la variable ausente, como se muestra en la figura 11.50. Si en la ecuación de un plano faltan dos variables, éste es paralelo al plano coordenado correspondiente a las variables ausentes, como se muestra en la figura 11.51. (0, 0, 1) ( 12, 0, 0) y x z z z El plano 2x 1 z 5 1 es paralelo al eje y Figura 11.50 (0, 0, − dc ) (0, − bd , 0) y x ( ) − ad , 0, 0 El plano ax 1 d 5 0 es paralelo al plano yz Figura 11.51 y x El plano by 1 d 5 0 es paralelo al plano xz y x El plano cz 1 d 5 0 es paralelo al plano xy Larson-11-05.qxd 3/12/09 17:27 Page 805 SECCIÓN 11.5 Rectas y planos en el espacio 805 Distancias entre puntos, planos y rectas Esta sección concluye con el análisis de dos tipos básicos de problemas sobre distancias en el espacio. Q n 1. Calcular la distancia de un punto a un plano. D proyn PQ P D = proyn PQ La distancia de un punto a un plano 2. Calcular la distancia de un punto a una recta. Las soluciones de estos problemas ilustran la versatilidad y utilidad de los vectores en la geometría analítica: el primer problema usa el producto escalar de dos vectores, y el segundo problema usa el producto vectorial. La distancia D de un punto Q a un plano es la longitud del segmento de recta más corto que une a Q con el plano, como se muestra en la figura 11.52. Si P es un punto cualquiera del plano, esta distancia se puede hallar proyectando el vector PQ .sobre el vector normal n. La longitud de esta proyección es la distancia buscada. \ Figura 11.52 TEOREMA 11.13 DISTANCIA DE UN PUNTO A UN PLANO La distancia de un punto a un plano Q (no en el plano) es |PQ ? n| \ \ D D5 5 iproy iprojnPQ i 5 in i donde P es un punto en el plano y n es normal al plano. Para encontrar un punto en el plano dado por ax 1 by 1 cz 1 d 5 0 sa Þ 0d, se hace y 5 0 y z 5 0. Entonces, de la ecuación ax 1 d 5 0, se puede concluir que el punto s2dya, 0, 0d está en el plano. Calcular la distancia de un punto a un plano EJEMPLO 5 Calcular la distancia del punto Qs1, 5, 24d al plano dado por 3x 2 y 1 2z 5 6. Solución Se sabe que n 5 k3, 21, 2l es normal al plano dado. Para hallar un punto en el plano, se hace y 5 0 y z 5 0, y se obtiene el punto Ps2, 0, 0d. El vector que va de P a Q está dado por \ PQ 5 k1 2 2, 5 2 0, 24 2 0l 5 k21, 5, 24l. Usando la fórmula para la distancia dada en el teorema 11.13 se tiene |PQ ? n| 5 |k21, 5, 24l ? k3, 21, 2l| \ D5 in i !9 1 1 1 4 5 5 Distancia de un punto a un plano. |23 2 5 2 8| !14 16 !14 . NOTA El punto P que se eligió en el ejemplo 5 es arbitrario. Seleccionar un punto diferente en el plano para verificar que se obtiene la misma distancia. n Larson-11-05.qxd 806 3/12/09 17:27 CAPÍTULO 11 Page 806 Vectores y la geometría del espacio Del teorema 11.13 se puede determinar que la distancia del punto Qsx0, y0, z0d al plano dado por ax 1 by 1 cz 1 d 5 0 es D5 |asx0 2 x1d 1 bs y0 2 y1d 1 csz0 2 z1d| !a2 1 b2 1 c2 o D5 |ax0 1 by0 1 cz0 1 d| Distancia de un punto a un plano. !a2 1 b2 1 c2 donde Psx1, y1, z1d es un punto en el plano y d 5 2 sax1 1 by1 1 cz1d. Encontrar la distancia entre dos planos paralelos EJEMPLO 6 z 3x − y + 2z − 6 = 0 Encontrar la distancia entre los dos planos paralelos dados por 3 3x 2 y 1 2z 2 6 5 0 y 6x 2 2y 1 4z 1 4 5 0. −6 (2, 0, 0) 2 x D y Solución Los dos planos se muestran en la figura 11.53. Para hallar la distancia entre los planos, elegir un punto en el primer plano, digamos (x0, y0, z0) = (2, 0, 0). Después, del segundo plano, se puede determinar que a 5 6, b 5 22, c 5 4 y d 5 4, y concluir que la distancia es D5 6x − 2y + 4z + 4 = 0 La distancia entre los planos paralelos es aproximadamente 2.14 Figura 11.53 5 5 |ax0 1 by0 1 cz0 1 d| Distancia de un punto a un plano. !a2 1 b2 1 c2 |6s2d 1 s22ds0d 1 s4ds0d 1 4| !62 1 s22d2 1 42 16 !56 5 8 !14 < 2.14. La fórmula para la distancia de un punto a una recta en el espacio se parece a la de la distancia de un punto a un plano, excepto que se reemplaza el producto vectorial por la magnitud del producto vectorial y el vector normal n por un vector de dirección para la recta. TEOREMA 11.14 DISTANCIA DE UN PUNTO A UNA RECTA EN EL ESPACIO La distancia de un punto Q a una recta en el espacio está dada por \ D5 iPQ 3 u i iu i donde u es un vector de dirección para la recta y P es un punto sobre la recta. Punto Q DEMOSTRACIÓN En la figura 11.54, sea D la distancia del punto Q a la recta dada. Entonces D 5 iPQ i sin sen u, donde u es el ángulo entre u y PQ . Por el teorema 11.8, se tiene \ D = PQ sen θ P θ u Recta \ \ iu i i PQ i sen sin u 5 i u \ 3 Por consiguiente, \ Distancia de un punto a una recta Figura 11.54 i PQ 3 u i D 5 i PQ i sen sin u 5 . iu i \ \ PQ i 5 iPQ 3 u i. 1053714_1105.qxp 10/27/08 10:39 AM Page Page 807 807 1053714_1105.qxp 10/27/08 AM Page 807 Larson-11-05.qxd 3/12/0910:39 17:27 SECCIÓN 11.5 11.5 11.5 Rectas y planos en el espacio Lines and and Planes Planes in in Space Space Lines 807 807 807 Hallar la distancia de un punto a una recta Finding the the Distance Distance Between Between aa Point Point and and aa Line Line EXAMPLE 7 Finding Hallar la the distancia delbetween punto Qsthe la recta 3, 21, Find distance point4dQa 3, 1, 4dada and por the line given by EJEMPLO 7 Find the distance between the point Q 3, 1, 4 and the line given by y zand x 5x22 123t, 3t, y 5 22t, 2t, 5 1 z1 4t.1 4t. x 2 3t, yy 2t, and z 1 4t. SolutionUsando Usinglosthe the direction numbers 3,3,222, 2, and 4, you you know that de direction Solución números de dirección y 4, se 4, sabe queknow un vector dirección Solution Using direction numbers and that aa direction vector for the line line isis de lavector recta for es the 3, 4l. 2, 44 .. Direction vectordefor for line Vector de dirección laline recta. u 5uuk3, 22, 3, 2, Direction vector To find aa point point on the line, line, let and obtain obtain ParaTo determinar unon punto en la let recta, hace t 5 0 y se obtiene find the tt se 00 and 2,10, P 5PPs22, 0,2, d0, . 11 .. So, Así,So, z zz 6 66 5 55 D D D Q = (3, −1, 4) Q == (3, (3, −−1, 1, 4) 4) Q 4 x 44 xx Point onlathe the line Punto sobre recta. Point on line \ \ 0, 5, 3l1, 1, 33 PQ PQ PQ 5 k3 233s22d, 21 2441l 5 22 ,, 2110, 40, 11 k5, 21, 5, and youformar can form form the cross crossvectorial product y seand puede el producto you can the product \ 3 33 2 22 −2 −2 −−22 −−22 1 2 3 2 11 1 2 −1 1 33 −1 1 2 −1 22 3 33 4 44 5 55 \ \ \ \ \ PQ 3 u i uu Di PQ PQ D 5D iu i uu 174 !174174 5 29 !29 29 2.45. 5 !6 <662.45. 2.45. y yy La punto the Q apoint la recta es the Thedistancia distancedel between and QQand The distance between the point the 2.45. line is 6 2.45. ! 6< 6 line is 2.45. Figura Figure 11.55 11.55 Figure 11.55 Ejercicios 11-5 Exercises 11.5 Exercises | | i ii j jj k kk PQ u 5 2i11j 11j 11j 7kk2, 211, 2, 11, 11, 77 .. PQ PQ 3 u 5u 5 5 21 2 7k 5 27l. 11 3 5 33 2i 22i 7k 2, 3 3 322 22 4 44 Finally, using Theorem Theorem 11.14, yousecan can find the theque distance to be be es Por Finally, último, using usando el teorema 11.14, encuentra la distancia 11.14, you find distance to \ Seewww.CalcChat.com www.CalcChat.comfor forworked-out worked-outsolutions solutionstotoodd-numbered odd-numberedexercises. exercises. See In Exercises Exercises and 2, the figuremuestra shows the the graph ofde line given given En los ejercicios 1 y2, 2,the la figura lagraph gráficaof una recta In 11 and figure shows aa line by the parametric equations. (a) Draw an arrow on the line to dada por las ecuaciones paramétricas. a) Dibujar una flecha by the parametric equations. (a) Draw an arrow on the line to indicate its orientation. To print an enlarged copy of the graph, sobre la recta para indicar su dirección. b) Hallar las coordeindicate its orientation. To print an enlarged copy of the graph, goto to the the website www.mathgraphs.com. (b) Find Findthe theelcoordinates coordinates nadas de dos puntos, P y Q, en la recta. Determinar vector PQ . go website www.mathgraphs.com. (b) of two twoespoints, points, and on the line. Determine Determine the vector vector PQ.. Q, on ¿Cuál la relación entre lasthe componentes del vector y los coefiof line. the PQ PP and Q, What is the relationship between the components of the vector cientes de t en las ecuaciones paramétricas? ¿Cuál es la razón de What is the relationship between the components of the vector and the coefficients of in the parametric equations? Why is this t esta relación? c) Determinar las coordenadas de todos los puntos and the coefficients of t in the parametric equations? Why is this true? (c)Determine Determine theplanos coordinates ofany any points points ofintersection intersection de intersección con los coordenados. Si la of recta no corta true? (c) the coordinates of with thelos coordinate planes. If If the the line line por doesqué. not intersect intersect aa awith uno the de planos coordenados, explicar coordinate planes. does not coordinate plane, plane, explain explain why. why. coordinate x 5 1 1 3t 1. 2. x 5 2 2 3t 1.yxx5 2112 t3t 2. yxx5 222 3t 3t 3t 1. 2. \ \ \ zyy5 2221 5ttt 5tz zz 22 5t zyy5 1222 t zz 11 tt z zz zz x y xx yy See Figure Figure 11.55. Ver figura 11.55.11.55. See x y yy In Exercises Exercises and determine whether each point liessobre on the the En los ejercicios 3 4, y4,4, determinar si cada punto yace la In 33 and determine whether each point lies on line. recta. line. 3. xx 3t, zz 44 tt 3. 22 t,t, yy 3t, a) b) 2, 0, 6, 6 2, 3, 3, 55 a) 0, 6, 6 b) x 3 y 7 4. x 3 y 7 zz 22 4. 22 88 a) 7, 7, 23, 23, 00 a) b) 1, 1, 1, 1, 3) 3) b) In Exercises Exercises 5–10, find sets of ofconjuntos (a) parametric parametric equationsparaand En los ejercicios 5 afind 10, hallar de a) ecuaciones In 5–10, sets (a) equations and (b) symmetric equations of the line through the point parallel to métricas y b) ecuaciones simétricas de la recta por el punto (b) symmetric equations of the line through the point parallel pato the given given vectoroor orrecta line (if (if possible). possible). (For each each line,cada writerecta, the ralela al vector dado (si es posible). (Para the vector line (For line, write the directionlos numbers asde integers.) escribir números dirección como enteros.) direction numbers as integers.) 5. 5. 6. 6. 7. 7. 8. 8. 9. 9. Point Punto Point 0, 0, 0 s0, 0, 0 d 0, 0, 0 s0, 0, 0 d 2, 0, 0, 33 2, s22, d 3, 0, 2 3, 0, 2 d s23, 1, 0, 1 s1, 0, 1 d 10. 3, 5, 5, 44 10. 3, s23, d Parallel to to Paralela a Parallel v 3, 1, v 3, 1, 55 2, 5552,, 11 vv 5 k 22, 2, 22 l 2i 4j 4j 2k vv 5 2i 1 2 2k 6j 3k 3k vv 5 6j 1 x 3 3t, y 5 2t, zz xx 5 33 1 3t, 77 1 ttt 3t, yy 5 55 2 2t, 2t, z 5 27 xxx 2 111 yyy 1 111 z 3 z 3 333 5 22 22 5 z 2 3 1053714_1105.qxp 10/27/08 10:39 AM Page 808 Larson-11-05.qxd 3/12/09 17:27 Page 808 1053714_1105.qxp 10/27/08 10:39 AM Page 808 1053714_1105.qxp 1053714_1105.qxp 10/27/08 10/27/08 10:39 10:39 AM AM Page Page 808 808 808 808 808 Chapter and Geometry of Space CAPÍTULO Vectores la geometría Chapter 11 1111 Vectors Vectors andythe the Geometrydel of espacio Space 808 808 808 Chapter 11 Vectors and the Geometry of Space Chapter Chapter11 11 Vectors Vectorsand andthe theGeometry GeometryofofSpace Space xx 33 yy 22 zz 22 In In Exercises Exercises 11–14, 11–14, find find sets sets of of (a) (a) parametric parametric equations equations and and (b) (b) 30. En los ejercicios 11 a 14, hallar conjuntos de a) ecuaciones 30. LL11:: 2 symmetric 11 22 symmetric equations equations of of the the line line through through the the two two points points (if (if pospos2 paramétricas y b) line, ecuaciones simétricas denumbers la recta que pasa por x x 3 1 y y 2 1 z z 23 Insible). Exercises 11–14, findwrite sets of (a) parametric equations and (b) (For each the direction as integers.) sible). (For each line, write the direction numbers as integers.) x 3 y 2 z In Exercises 11–14, find sets of (a) parametric equations and (b) 30. LL : xx 31 yy 21 zz 223 In Exercises 11–14, find setsline of (a) parametric equations and (b) los dos puntos (si es posible). (Para cada recta, escribir los 30. symmetric equations through the two points (if pos12 24 30. LL11L:122::: 224 22of 22 the symmetric equations of the line through the two points (if pos112 224 symmetric equations the line through the points 24 números de3, dirección enteros.) 22 line, ,, 33write 4, 33 ,,two1, 55 (if pos11. 12. ,como 5, 3,each 0,numbers 4, 1, 2,integers.) 11. 5, 12. 0, ,of 1 the 33,, 1 sible). (For direction as2, x x 12 y y 11 z z 33 sible). (For each line, write the direction numbers asasintegers.) sible). (For each line, write the direction numbers integers.) LL2: : xxx 112 yyy 111 zzz 333 13. 14. 7, 2, 2, 66 ,, 3, 3, 0, 0, 66 0, 0, 0, 25 25 ,, 10, 10, 10, 10, 00 13. 7, 14. 0, LL2L:233:: 4 20.5 41 11. 5, 3, 2 , 223,2 223,2 1 12. 0, 4, 3 , 1, 2, 5 4411 20.5 441 2 5, 3, 2 , 0, 4, 3 , 1, 2, 5 11. 12. , , 1 11. 5, 3, 2 , 3 3,3 3, 1 12. 0, 4, 3 , 1, 2, 5 x 2 y 1 z 3 In Exercises 15–22, find a set of parametric equations of the 13. 7, 2, 6 , 15–22, 3, 0, 6find a set 14. 0, 0, 25 , 10, 10, 0 of the In Exercises of parametric equations x 3 y 1 z x 2 y 1 z L : 23 yy 11 zz 3322 7,7, 2,2,66, , 3,3,0,0,66 13. 14. 3: : xx 25, , 10, 10,10, 10,00 13. 14. 0,0,0,0,25 L L 1 0.5 1 : L 4 line. : L 3 line. 34 44 1122 0.5 11 11 0.5 In Exercises 15–22, a set un of parametric the En los ejercicios 15 a find 22, hallar conjunto de equations ecuacionesof parax 3 y 1 z 2 In Exercises 15–22, find a set of parametric equations of the In Exercises 15–22, find a set of parametric equations of the yy 11 zz 22 15. line passes through the point 2, 3, 4 and is parallel to the L4: xx 3331–34, 15. The Thede line line. métricas la passes recta. through the point 2, 3, 4 and is parallel to the In and L 2 31–34, 1 whether In Exercises Exercises the lines intersect, intersect, and if L4:4:ejercicios line. En los 31444determine adetermine 34, determinar si the las lines rectas se cortan, y if si line.xz 22 11 whether xz-plane yz-plane. -plane and and the the yz -plane. so, find the point of intersection and the cosine of the angle of so, find the point of intersection and the cosine of the angle of es así, hallar el punto de intersección y el coseno del ángulo de 3, 4paralela The line passes the and to the 15. La recta pasa porthrough el punto (2,point 3, 4) 2, y es alparallel plano xz y al 22 is 16. The line passes through the point and is to 445, 15. the point and is totothe 4, 5, 16.The Theline linepasses passesthrough through the point2,2,3,3,4, and is parallel parallel to Inintersection. Exercises 31–34, determine whether the lines intersect, and if 15. line passes through the point and isparallel parallel the intersection. In Exercises 31–34, determine whether the lines and ifif intersección. xzThe yz -plane and the -plane. plano yz. In Exercises 31–34, whether linesintersect, intersect, andof xy yz the and the xzxz -plane and -plane. xy-plane yz-plane. the -plane andyzyz the -plane. so, find the point of determine intersection and thethe cosine of the angle -plane andthe the -plane. so, find the point ofyofintersection and the cosine ofofthe angle ofof so, find the point intersection and the cosine the angle x 4t 2, 3, z t 1 31. 4, 5, 2 The line passes through the point and is parallel to 16. La recta pasa por el punto (24, 5, 2) y es paralela al plano xy y x 4t 2, y 3, z t 1 31. 31. x 5 4t 1 2, y 5 3, z 5 2t 1 1 intersection. 3, 45, 17. The line passes through the point is perpendicular 16. the and 2,4, 3,5, 4 2and 17.The Theline linepasses passesthrough point 2, is is perpendicular 4, 2and 16. The line passes through thepoint and isparallel paralleltoto intersection. intersection. xy yz3x the -plane the -plane. al plano yz. and xx 2s 3, 2y z 6. to the plane given by 2s 2, 2, yy 2s 2s 3, 3, zzz5 sss1 111 xy yz the -plane and the -plane. 3x 2y z 6. to the plane given by the xy-plane and the yz-plane. z t 1 31. xx 54t2s 12,2, yy 53,2s 1 2, 3, 4 17. The line passes through the point and is perpendicular x 4t 2, y 3, z t t 2t 31. La recta pasa por el punto (2, 3, 4)2,y4, al plano 1, 4t 1, 32. 4t 3t 2, 1, 31. 5, 22and 18. The line passes through point and perpendicular 3t1 1,yyyy5 3, 4t1z 1, 1,zzz5 2t11 44 32. xxx5 23t 3,es 44perpendicular 17. through isisisis perpendicular 4t 32. 4, 5, 18.The Theline linepasses through the the point and perpendicular 2, 3, 17. The line passes the point and perpendicular x 2s 2, y 2s 3, z 2ts 1 41 3x 2y z 6. totothe plane given by dado por 3x 1 2y 2 z 5 6. xxx 2s2s 2s2s 4, 3,3,zz zz ssss 1111 2y the plane given by toto 3s 1, 2y zzzz 6.6.5. 5. tothe theplane planegiven givenby 3xxx 2y 2y the plane given by3x 3s 2,2, 1, yyyy 2s 2s 4, 2t 1 41 32. xx 5 3s3t1 1,1,yy5 2s4t1 4,1,zz5 2s 4, 5, 2 The line passes through the point and is perpendicular 18. La recta pasa por el punto (24, 5, 2) y es perpendicular al plano x 3t 1, y 4t 1, zz11 2t2t 44 32. 44 is 19. The line passes through the point and is 4, 23,2 and 18. passes through the point perpendicular zz 33 3t 222 1, y 4t xxx1, 32. xxxx yyy2 5,4,5,5,3, 19.The Theline line passes through the point 5, and is parallel parallel to to 18. The line passes through the point and is perpendicular 33. 1, tov thepor plane by dado 2xgiven 13 2y 1 z x5 5.2y zz 5. 1, 5 y zzz1 2s1, z24 1 5s yyy112225 z 133 33.xx3 53s 1, 4, 33. 2, toto given vthe 2, 1, 1, 3 .. by 1 3s 1, y 2s 4, z s 1 2y z 5.5. theplane plane given by xx 2y 3 1 4 s 1 3x 3s21 1, y 2s 4, 4z 233 3,4,24) 43 and The line passes point parallel toto 19. La recta pasa through por el the punto (5, 5, 23, yand esis paralela a xx y2 2y 2 x 1x 3 z 3z 2 1, 20. The line passes through the point is parallel 5, 3, 4 19. The line passes through the point and is parallel to 1, 4, 3 20. The line passes through the point and is parallel to x 1 x y 2 z 19. The line passes 33. xxx2 2y2 y2y2 z22 1,z x3,4 x1x2 yy33 22y 5z 33z3z1 22 2, 1,j.3l. 3 . through the point 5, 3, 4 and is parallel to vvv5 k2, 21, 34. 33. 34.33 3 511 6 zz 51,z1, z2 3,3, 33. 5i 34. 5i j.33. . vv 2, 2, 1,1, 44 222 y 5 y2y1 555 33 444 3233 1 66 1, 4, 3 The line passes through the point and is parallel to 20. La recta pasa por el punto (21, 4, 23) y es paralela a x 2 y 2 x 3 z 2 2, 1, 2 21. The line passes through the point and is parallel to the 1, 4, 3 20. The line passes through the point and is parallel to 21. The Theline linepasses passesthrough throughthe thepoint point 2,1,1,4,2 and is parallel to the 3 and 20. is parallel to xx 22 yy 22 z 3, xx 33 y 5 zz 22 34. vvline 5 5i 2 j. CAS In Exercises 35 and 36, use graph 34. z36, 3,3,aa computer yalgebra 55 system En los ejercicios 35 y usar un sistema algebraico compu3 6 2 4 porto CAS In Exercises 35 and 36, use computer algebra system x t, y 1 t, z 2 t. 34. z y 5i j. x t, y 1 t, z 2 t. line v 5i j. 33 66 22 44 to graph the pair of intersecting lines and find the point of intersection. tadora para representar gráficamente el par de rectas que se cor2, 1, 2 21. The line passes through the point and is parallel to the the pair of intersecting lines and find the point of intersection. La recta pasa porthrough el punto (2, 1, 2) y2 es a latorecta 88paralela 22. The line passes the point and is to 21. the point and is 6,20, 0, 22.The Theline linepasses passesthrough through the point2,2,1,1,6, and is parallel parallel toCAS In Exercises 35 and 36, use a computer algebra system to graph 21. The line passes through the point and isparallel parallel tothe the tan y hallar el punto de intersección. x t, y 1 t, z 2 t. xline 5 2t, y 5 1 1 t, z 5 22 1 t. CAS Exercises 35 and use a zcomputer algebra system totograph the line CAS In In 353, 36, use2, graph 2t,t.zt. z 0. 0. thexline line 35. xx of2t yy 36, 5t tt the 11algebra x xx t,t,y5y5 12t, 12t, yyt,t,zz 44 222t, line 35.Exercises 2tintersecting 3,and 5tlines 2,aand zcomputer the pair find point ofsystem intersection. the pair of intersecting lines and find the point of intersection. 8 paralela Therecta line passes through the (26, point0, 8)6, y0,es and is parallel to 22. La pasa por el punto a la recta the pair of intersecting lines and find the point of intersection. z5 35. xxx5 2t 1 6, 0,0,88 and 22. The line through the point toto 2s ss 2, 8, zz 2t2s 22. Theline linepasses passes through the point andisPisparallel parallel 2s 3, y7, 7,5yy 5t 2 8, 2s1 111 In 23–26, find on the line 2t, y1the 2t, z 6,of 0. aa point xthe 5line 5 2xx 2t, y55 5 24 2t,coordinates z44 5 0. In Exercises Exercises 23–26, find coordinates 35. x 2t 3, y 5t 2, z t 1 2t, yy the 2t, zz of 0.0. point P on the line the 35. x 2t 3, y 5t 2, z t x 5 22s 1 7, y 5 s 1 8, z 5 2s x 5 2t, 4 2t, the line 36. 1, 35. z10, zz t tt2111 and 36. xx 2t 2t 3, 1,yy 5t 4t 4t 2, 10, and aa vector vector vv parallel parallel to to the the line. line. x 2s 7, y s 8, z 2s 1 P In Exercises 23–26, find the coordinates of a point on the line y5y yy24t ss 3s zz11, 2s 2 18,8, 10, z5 36. xxxx5 2t2s2s 5s 12, zz2st 112s En losx ejercicios 23 afind 26,1the hallar las coordenadas dePPun P 5s 1,7,y7, 12, 3s 11, 2s 44 In Exercises coordinates ofofaapoint on the In coordinates point onpunto theline line 33 23–26, t,t,parallel yy find 2t, 23. 2t, 23.Exercises 36. x 2t 1, y 4t 10, z t v23–26, and axla vector to1the the line.zz a la22recta. sobre recta y un vector v paralelo 36. x 2t 1, y 4t 10, z t x 5 25s 2 12, y 5 3s 1 11, z 5 22s 24 v and a vector parallel to the line. 36. x 2t 1, y 4t 10, z t and a vector vy parallel to the line. 24. Cross In 37 38, find 4t, y 55 t,t, zz 44 3t 3t 24. xx 4t, x Product 5s 12, yExercises 3s 11, zand 2s(a) 4 the Cross Product In Exercises 37 and 38, (a) the coordinates coordinates xx 5s5s 12, 3s3s 11, 2s2s 4find t, y 21 1 2t, z 2 23. xx 5 33 2 t, 12,yQ, y and 11,zzthe plane, 4 determine the 2t, 23. of points R 2x2x 33 yy zz 33 23. of three three vectorial points P, in the 37 plane, and determine the P, En Q, and R in 66 111 2t, Producto los ejercicios y 38,and a) hallar las coor2t, zzz5 22 23. xxxx 3377 t,t,yy yyy5 zz zz 5 22 44 1 3t 25. 26. 4t, yy 5255 2 t, 24. 25.xxx 544t, 26. 5 Cross Product In Exercises 37RPQ and 38, (a).. find the coordinates t, 3t 24. vectors and (b) Find What is the relationPQ PR . PR denadas de tres puntos P, Q y en el plano, y determinar los vec8 6 vectors and (b) Find What is the relationPQ PR . PR PQ 4t, y 5 t, z 4 3t 24. Cross Product In 37 and 38, coordinates 5 8 6 24. x 4 4t, y 2 5 t, z 4 3t Cross Product InExercises Exercises 37 38,(a) (a)find findthe the coordinates of three points andPQ in and the plane, determine P, Q, R3 ship between components of the cross and the x x 31 3 y y z z 32 3 tores ypoints b) esand laproduct relación entre las PQ PR . the . ¿Cuál ship between the components of the cross product andthe the xxxx2 7777 yyyy1 6666 z 2 of three points and the plane, and determine the P,P,Hallar Q, RR ininPR x 3 y z 3 of three and the plane, and determine the Q, 25. 26. x 3 y z 3 5 5 z 1 2 25. 26. 5 5 vectors and (b) Find What is the relationPQ PR . PR . PQ In Exercises 27–30, determine if any of the lines are parallel or z 2 25. 26. coefficients of the equation of the plane? Why is this true? componentes del producto vectorial y. What los coeficientes de la 8 are 6 6 In Exercises 27–30, determine if any parallel or coefficients of the equation of the plane? Why is this true? z 2 25. 26. of55the5 lines 4444 2222 8 vectors and (b) Find is the relationPQ PR . PR PQ 88 66 vectors is the and relationPQ and . (b) Find PQ . What 5 ship between thePR components thePR cross product the identical. ecuación del plano? ¿Cuál es la of razón? identical. ship between the components of the cross product and ship between the components of the cross product and the the 37. 38. 4x 3y 6z 6 2x 3y 4z 4 37. 38. 4x 3y 6z 6 2x 3y 4z 4 In Exercises 27–30, determine if any of the lines are parallel or coefficients of the equation of the plane? Why is this true? In Exercises determine ofzalgunas the lines4t are or coefficients equation ofofthe plane? Why is this En 30, de lasparallel rectas son In Exercises any parallel or coefficients the equation the38. plane? Why this true? 27. LL1ejercicios 627–30, yy determinar 22ififany 2t, :1: xx 27–30, zz 5 zzis4z 37. 4x 2 3yofof 2the 6z 6 2x 1 3y 1 5true? 4 27.los 6 273t, 3t,a determine 2t, siof z the55 lines 4t are identical. identical. paralelas o idénticas. identical. 37. 4x 3y 6z 38. 2x 3y z 4z 4 6 z LL2:: xx 6t, 37. 38. 6t, yy 22 4t, 4t, zz 13 13 8t 8t 37. 4x 38. 2x 4x 3y 3y 6z 6z 66 2x 3y 3y 4z4z 44 27. L1: 2 x 6 3t, y 2 2t, z 5 4t z z z 27. L : x 6 3t, y 2 2t, 5 4t z zz xx 610 27. LL 2t, zzz 775 8t 4t 1L13::: x z 10 3t,6t, 6t, y yy 332 4t, 4t, 8t L2:3 x 6t, y 2 4t, z 13 8t LL2L:24::xxx 6t, 22 yy4t, 13 6t,44yy 6t, 4t,33zz 4t, 13 zz 8t8t55 6t yy 6t, 4t, 6t yy L3:4 x 10 6t, y 3 4t, z 7 8t xx L : x 10 6t, y 3 4t, 7 8t z y 28. 33 2t, 6t, yyy 36t, xx 28. L3L311:: xx 10 2t, 6t, 4t,zz z11 72t 2t 8t y L4: x 4 6t, y 3 4t, z 5 6t x y y LL4L:42::xxx 1144 2t, 6t, 53t yy t,t, zzzz 3t 6t, yyyy 3311 4t, 4t, 5 6t6t x yy 2t, x 2 28. L1: x 3 2t, y 6t, z 1 2t xx x 28. z L : x 3 2t, y 6t, 1 2t x xx 3 11 2t,2t, 33 z10t, 28. LL 1L13::: x x 2t,y yy 6t, 10t, 1 zz 2t11 4t 4t L :3 x 1 2t, y 1 t, z 3t LL22L:24::xxx 1155 2t, y 1 t, 3t z In Exercises 39 and 40, determine whether 1 t, z 8 3t In Exercises 39 and 40, determine whether the the plane plane passes passes 2t, y 1 t, z 3t 2t, y 1 t, z 8 3t L3:4 x 1 2t, y 3 10t, z 1 4t through each point. through each point. z LL3:3: xxx 8811 yy2t, y 3 10t, 1 4t 2t, 5 y z 3 9 10t, z 1 4t In Exercises 39 and the pasa plane passes 29. L: : x 5 2t, y 5 1 z t,9 z 8 3t 29.L En los ejercicios 39 y40, 40,determine determinarwhether si el plano cada In Exercises 39 and 40, determine whether the planepor passes LL44L:411::xx 4455 2t, In 39 39. xx each 2y 4z 2t, 2y2y 11 33t,t, zz 88 3t3t 39.Exercises 2y point. 4z and11 40,00 determine whether the plane passes through punto. through each point. x x 87 y y 54 z z 96 through each point. a) 7, b) 29. LL : xxx 887 yyy 554 zzz 996 a) 7, 2, 2, 1) 1) b) 5, 5, 2, 2, 22 29. 21 35 29. LL11L:122::: 442 39. x 2y 4z 1 0 2 3 39. x 2y 4z 1 0 2 1 5 4 2 3 40. 3z 39. 40. x2x 2x 2yyy 4z 3z 166 00 x 7 y 4 z 6 a) 7, 2, 1) b) 5, 2, 2 LL2: : xxxx 7744 yyyy 4411 zzzz 6618 a) 7, 2, b)b) 18 3, 6, a) 7, 2, 2, 25, 11 a) 3, 6, 221)1) b) 5,5,2,1, 1,25, LL2L:233:: 2 1 5 40. 2x y 3z 6 0 2288 1144 55 66 40. 2x y 3z 6 0 40. 2x y 3z 6 0 x 4 y 1 z 18 a) 3, 6, 2 b) 1, 5, 1 44 L : x x 42 y y 13 z z 18 a)a) 3,3,6,6, 22 b)b) 1,1,5,5, 11 LLL33L:344::: xx 8 42 yy4 13 zz 6 18 1.5 8822 4411 66 1.5 x 2 y 3 z 4 L: x 2 y 3 z 4 LL44:4: x 2 2 y 1 3 z1.5 4 22 11 1.5 1.5 \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ 1053714_1105.qxp 10/27/08 AM Page 809 1053714_1105.qxp 10/27/08 10:40 AM Page Page 809 809 Larson-11-05.qxd 3/12/0910:40 17:27 1053714_1105.qxp 10/27/08 10:40 AM Page 809 1053714_1105.qxp 10/27/08 10:40 AM Page 809 1053714_1105.qxp 10/27/08 10:40 AM Page 809 SECCIÓN 11.5 11.5 11.5 11.5 11.5 11.5 En los ejercicios 41 a 46, hallar una ecuación del plano que pasa In 41– 46, ofof the plane In Exercises 41– 46, find an equation the plane passing In Exercises Exercises 41– 46, find find an an equation equation ofrecta the dado. plane passing passing In Exercises 46, find an equation the plane passing por el punto y 41– es perpendicular al vector oof In Exercises 41– 46, find an equation of the plane passing through the point perpendicular to the given vector or line. through the point perpendicular to the given vector or line. throughthe thepoint pointperpendicular perpendicularto tothe thegiven givenvector vectoror orline. line. through through the point perpendicular to the given vector or line. Punto Perpendicular ato Point Perpendicular Point Perpendicular Point Perpendicularto to Point Perpendicular to Point Perpendicular to 1, 3, 7 n j 41. 1, 3, 7 n j 41. 41. 1,1,3,3, 77 nn jj 41. j 41. 0,1, 3,1, 47 nnn 42. n 42. 0, 1,1, 1,444 n kkk k 42. 0,0, 42. n 2ik 3j k 42. 3,0,2, 21, 4 n 43. 3, 2, 2 n 2i 3j 43. 3j kk k 43. 3,3,2,2,22 nn 2i2i 3j 43. n 2i3i 3j2k k 43. 0,3,0,2,02 n 44. 0, 0, 0 n 3i 2k 44. 2k 44. 0,0,0,0,00 nn 3i3i 2k 44. 2k 44. 0,1,0,4,0 0 xxn 11113i 2t, 45. xx 2t, 2t 45. 1,4,4, 4,000 2t,yyyy 5555 t,t,t, t,zzzz 3333 2t 2t 45. 1,1, 2t, 2t 45. 1, 4, 0 x 1 2t, y z 5 3 t, z 3 2t 45. xxxx 1111 z 3 z 3 z 3 46. 46. 3,2, 2,2222 46. 3, x 44 1 yyyy 2222 z 333 3,3, 2,2, 46. y 2 46. 3, 2, 2 44 33 4 3 In In Exercises 47– 58, find an equation of the plane. InExercises Exercises47– 47–58, 58,find findan anequation equationof ofthe theplane. plane. In Exercises 47– 58, find an equation of the plane. En ejercicios 58, hallar una ecuación del plano. In los Exercises 47–47 58,a find an equation of the plane. 0, 0, 0 , 2, 0, 3 , 47. The plane passes through 0, 0, 0 , 2, 0, 3 47. The plane passes through and 0, 0, 0 , 2, 0, 3 3, 1, 1,5555.... 47. The Theplane planepasses passesthrough through 0, 0, 0 , 2, 0, 3 ,,,and and 3, 3,3, 1,1, 47. and 47. plano quepasses pasa por (0, 0, 0, 0),0,(2, 3)0,y 3(23, –1, 5). 02 ,0, 2, ,, and 3, 2,1, 52 .. 47. El The plane through 3, 1, , 2, 1, 5 1, 48. The plane passes through and 3, 1, 2 , 2, 1, 5 , 1, 2, 48. The plane passes through and 48. The Theplane planepasses passesthrough through 3,3, 1,1,22 ,, 2,2,1,1,55 ,,and and 1,1, 2,2, 222 ... 48. 48. ElThe plano que pasa through por (3, –1, 2),1,(2,2 1, 5)1,y 5(1,22, –2). 3, , 2, , 1, 2, 2. 48. plane passes and 49. 1, 2, 3, 2, 1, 49. The plane passes through and 1,2, 2,3333,,,, 3, 3,2, 2,1111,,,,and 1, 2, 2,2222.... 49. The Theplane planepasses passesthrough through 1, and 1, 1, 2, 3, 2, 2,2, 49. The plane passes through and 49. ElThe plano quepasses pasa por (1, 2, 1, 3),2,(3, 2,3, 1)2,y 1(21, 22, 1, 2). 3 , , 1, 2, 2 . 49. plane through and 50. 2, 50. The plane passes through the point and parallel 1,2, 2,3333 and 50. The Theplane planepasses passesthrough throughthe thepoint point 1, andis isparallel parallelto to 1,1, 2, 50. The plane passes through the point and isis parallel toto 50. El plano que pasa por el punto (1, 2, 3) y es paralelo al plano yz. 50. the The plane passes through the point 1, 2, 3 and is parallel to plane. yzthe plane. yztheyzplane. yzthe plane. CAS CAS CAS CAS yzthe plane. 51. El plano que pasa por el punto (1, 2, 3)1,1, y2,es paralelo al plano xy. 3 51. The plane passes through the point and is parallel to CAS 2, 3 51. The plane passes through the point and is parallel to 1, 2, 3 51. The plane passes through the point and is parallel to 1, 2, 3 51. The plane passes through the point and is parallel to 1, 2, 3deand 51. El The plane passeselthrough the point parallel 52. plano contiene eje y y forma un ángulo el ejeto x py6iscon xythe plane. xythe plane. xythe plane. xythe plane. xythe plane. positivo. 52. 52. The plane contains the axis and makes an angle of with y-axis 52. The Theplane planecontains containsthe theyaxisand andmakes makesan anangle angleof of 6666with with y-y52. The plane contains the axis and makes an angle of with y-axis 52. El The plane contains the andpor makes an angle of 6 with 53. plano contiene las rectas dadas xthe positive axis. xthe positive axis. xthe positive axis. xthe positive axis. x-axis. lines given by the plane positive 53. 53. The plane contains the lines given by 2 1plane x 2given 2 by y21 z22 53. xThe The planecontains containsthe thelines lines given by 53. The contains the 5y2 4 5 z they lines given 5 by 5 . 53. The plane contains 23 xxxx221111 xxxx 2222 4yyyy 1111 21 zzzz 2222 and x 2 y 1 z 2.... and x 221 yyyy 4444 zzzz and and 4444 1111 .dada por 33 y contiene y por 4 elzpunto and(2, 2,331) 54. El plano la recta 22 pasa 2 3 4 1 54. 54. xThe Theplane plane passesthrough throughthe thepoint point 2, andcontains containsthe the yplane 2 4 passes 2,2, 2,1111 and 54. The plane passes through the point and contains the 2,2, 2,2, 54. The passes through the point and contains the 5 given 5 z. through the point 2, 2, 1 and contains the 54. line The planeby passes line given by line given by 2line 21 by given line given by xxxx yyyy 4444 55. El plano pasa z. por z. los puntos (2, 2, 1) y (21, 1, 21) y es perz.z. 22x22 y 11114al plano z. 2x 2 3y 1 z 5 3. pendicular 2 1 56. plano pasa por through los puntos (3, 2, 1) y2, 25) 2, 1, 1, 55. The plane passes the points 11 and 55. The plane passes through the points and 2,(3, 2,111, 1,perpen1, 1111 55. El The plane passes through the points and y es 2,2, 2,2, 1,1, 1,1, 55. The plane passes through the points and 2, 2, 1 1, 1, 1 55. dicular The plane passes through the points and al plano 6x 1 7y 1 2z 5 10. 2x 3y z 3. and is perpendicular to the plane 2x 3y z 3. and is perpendicular to the plane 2x 3y 3y zz 3.3. andisisperpendicular perpendiculartotothe theplane plane2x and 2x 3y z 3. and is perpendicular to the plane 57. plano pasa por los puntosthe (1, points 22, 21)3, (2,11115,and 6) y 3, es parale56. The plane passes through 3, 1, 56. The plane passes through the points and 3,y2, 2, 3,1, 1, 5555 56. El The plane passes through the points and 3,3, 2,2, 3, 1, 56. The plane passes through the points and 3, 2, 1 3, 1, 5 56. lo The plane passes through the points and al eje x. 6x 7y 2z 10. and is perpendicular to the plane 6x 7y 2z 10. and is perpendicular to the plane 6x 7y 7y 2z 2z 10. 10. andisisperpendicular perpendiculartotothe theplane plane6x and 6x 7y 2z 10. and is perpendicular to the plane 58. plano pasa por through los puntos (4, 2, 1) y1, yand es paralelo 2, 2, 57. The plane passes the points 11 and 57. El The plane passes through the points and 1,(23, 2,5, 117) 2,5, 5,6666 57. The plane passes through the points and 1,1, 2,2, 2,2, 5,5, 57. The plane passes through the points 57. al The plane passes through ejeis z.parallel xand to and parallel the axis. x-axis. and is parallel tothe the axis.the points 1, 2, 1 and 2, 5, 6 x-xand isis parallel toto the axis. and plane is parallel to the x-axis.the points 4, 2, 1 and 58. 58. The plane passes through the points and 4,2,2, 2,111 and 3,5, 5,7777 58. The The plane plane passes passes through through the the points points 4,4, and 3, 3,3, 5,5, 58. The passes through 4, 2, 1 and 3,y5,ha7 58. The plane passes through the points zand is parallel to the axis. zand is parallel to the axis. En los ejercicios 59 y 60, representar gráficamente la recta zand is parallel to the axis. and is parallel to the z-axis. zand is parallel to the axis. llar los puntos de intersección (si los hay) de la recta con los planos In InExercises Exercises 59and and60, 60,sketch sketchaaaagraph graphof ofthe theline lineand andfind findthe the xy, xz y yz. 59 In Exercises 59 and 60, sketch graph of the line and find the In Exercises 59 and 60, sketch graph of the line and find the In Exercises andthe 60, sketch a graph ofxy the line and find the yz points (if where intersects the -,-,-, -,-,-, xy xz yz points (if any) where the line intersects the and -planes. xy xz yz-planes. points (ifany) any)59 where theline line intersects the -,xz -,and and -planes. xy xz yz points (if any) where the line intersects the and -planes. points intersects the1xyt-, xz-, and yz-planes. 59. x 5(if1 any) 2 2t,where y 5the 22line 1 3t, z 5 24 2222 3t, 4444 tttt 59. 2t, 3t, 59. 2t, yyyy z 2 3t, zzzz 59. xxxxx2 21111 2t, 2t, 3t, 59. 3 4 t 59. xx 215 y2t, 1 1y5 zz 2 33 3t, z 60. x 2 xx 3 22 yy 11 zz 2 33 60. 60. 60. x 2 yy 11 z 22 3 60. y 1 60. 3333 22 3 2 En los ejercicios61– 61 a64, 64,find hallaranuna ecuaciónofdel plano que conIn In Exercises equation the plane that In Exercises Exercises 61– 61–64, 64, find find an an equation equation of of the the plane plane that that In Exercises 61– 64, find an equation of the plane that tiene todos los puntos equidistantes de los puntos dados In Exercises 61– 64, find an equation of the plane that contains all the points that are equidistant from the given points. contains all the points that are equidistant from the given points. containsall allthe thepoints pointsthat thatare areequidistant equidistantfrom fromthe thegiven givenpoints. points. contains contains all the points that are equidistant from the given points. 61. 62. 1) 61. 2, 62. 1, 2,2, 2,0000,,,, 0, 0,2, 2,2222 1,0, 0,2222,,,, 2, 2,0, 0,1) 1) 61. 62. 2,2, 2,2, 0,0, 2,2, 1,1, 0,0, 2,2, 0,0, 1) 61. 62. 61. 2,3,2,1,0 2, , 0,6,2, 22, 4 62. 1,5,0,1,2 , 3 ,2, 0,2,1) 1, 6 63. 64. 3, 1, 2 , 6, 2, 4 5, 1, 3 , 2, 63. 64. 1,666 63. 3,3,1,1,22 ,, 6,6, 2,2,44 64. 5,5,1,1, 33 ,, 2,2, 1,1, 63. 64. 3, 1, 2 , 6, 2, 4 5, 1, 3 , 2, 1, 6 63. 64. Rectas y planos en el espacio Lines Lines and Planes in Space Linesand andPlanes Planesin inSpace Space Lines and Planes in Space Lines and Planes in Space 809 809 809 809 809 809 En los ejercicios 65 a 70, determinar si los planos son paralelos, In –70, whether the planes are parallel, In Exercises –70, determine whether the planes are parallel, InExercises Exercises65 65ninguna –70,determine determine whether theno planes are parallel, In Exercises 65 –70, determine whether planes parallel, ortogonales, o65 de las dos cosas. the Si son niare paralelos ni In Exercises 65 –70, determine whether the planes are parallel, orthogonal, or neither. If they are neither parallel orthogonal, or neither. If they are neither parallel nor orthogonal, hallar or neither. neither. they are neither neither parallel parallel nor nor orthogonal, or IfIf de they are nor ortogonales, el ángulo intersección. orthogonal, or the neither. Ifintersection. they are neither parallel nor orthogonal, angle orthogonal,find find the angleof of intersection. orthogonal, find the angle of intersection. orthogonal, find the angle of intersection. orthogonal, find the angle of intersection. 65. 5x 2 3y 1 z 5 4 66. 3x 1 y 2 4z 5 3 65. 66. 5x 3y 3x 4z 65. 66. 5x 3y 3y zzzz 4444 3x yyyy 4z 4z 3333 65. 5x 66. 3x 5x 3y 3x 65. 66. 4y 7zz 5 14 29x 2 3y4z 1 12z3 5 4 3y17z 3x y 4z 65. xx5x14y 66. 9x xx 4y 4y 7z 9x 3y 12z 4y 7z 7z 1111 9x 3y 3y 12z 12z 4444 x 9x 3y 12z 67. x 2 3y 68. 3x 9x 6z 1 2y 3y 2z5 7 4y 16z 7z 5441 12z 4 x 3y 3x 2y z 67. 68. x 3y 6z 4 3x 2y z 67. 68. 3y 6z 6z 4 3x 2y 2y zz 7777 67. xx 3y 68. 3x 67. 68. 5x y 2 z6z5 444 x3x2 4y 1 2zz 5 07 x 13y 2y 67. 5x 68. xxx 4y 5x 4y 2z 5x yyyy zzzz 4444 4y 2z 2z 000 4y 69. 5x 70. x2x x5x2 5y z 5 2z 12z 00 y 2zz 5114 x 24y x 5y 2x z 1 69. 70. x 5y z 1 2x z 1 69. 70. 5y zz 11 2x zz 11 69. xx 5y 70. 2x 69. 70. 5x 25y 2 5z15 23 4x 10 x 25y z 5z 2x 1 yyz 1 8z 18z 5 10 69. 5x 70. 4x 25y 3 5x 25y 5z 3 4x 8z 10 5x 25y 5z 3 4x yyy 8z 8z 10 10 5x 25y 5z 3 4x 5x 25y 5z 3 4x y 8z 10 En los ejercicios 71 sketch asketch 78, marcar toda intersección y label dibujar la In 71–78, aaaagraph of InExercises Exercises 71–78, sketch graph ofthe theplane planeand and labelany any In Exercises 71–78, graph of the plane and label any In Exercises 71–78, sketch graph of the plane and label any In Exercises 71–78, sketch a graph of the plane and label any gráfica del plano. intercepts. intercepts. intercepts. intercepts. intercepts. 71. 72. 3x 4x 2y 6z 12 6y 2z 71. 72. 4x 2y 2y 6z 6z 12 12 3x 6y 6y 2z 2z 6666 71. 4x 72. 3x 4x 2y 6z 12 3x 6y 2z 71. 72. 4x y2y 3z6z 4 12 3x y6y z 2z 4 6 71. 2x 72. 2x 73. 74. 2x 2x y 3z 4 y z 73. 74. 2x yy 3z 3z 44 2x yy zz 444 73. 2x 74. 2x 73. 74. 2x y 3z 4 2x y z 4 73. 74. 75. 76. 2x 75. 76. 2x yyyy 8888 75. xxxx zzzz 6666 76. 2x 2x 75. 76. x z 6 2x y 8 75. 76. 77. 78. 77. 78. 77. xxxx 5555 78. zzzz 8888 77. 78. 77. x 5 78. z 8 In 79 aaaacomputer algebra system graph the In Exercises 79 –82, computer algebra system to graph the InExercises Exercises 79–82, –82, use computer algebra systemto topor graph the En los ejercicios 79 use ause 82, usar un sistema algebraico compuIn Exercises 79 –82, use computer algebra system to graph the In Exercises 79 –82, use a computer algebra system to graph the plane. plane. plane. para representar gráficamente el plano. tadora plane. plane. 79. 80. 2x 1 yyyyy 2 zzzzz 5 66666 3z 53333 79. 2x 80. xxxx 23z 2x 3z 79. 80. 79. 80. 2x 2x 3z 79. 80. x 3z4.7y3 z 79. 2x5x y 4y z 6z6 80. 2.1x 8 3333 81. 82. 5x 4y 6z 8 2.1x 4.7y 81. 82. 5x 1 4y 4y 2 6z 6z 5 28 2.1x 2 4.7y 4.7y 2 zzzz 5 23 81. 25x 82. 2.1x 81. 82. 4y 6z 2.1x 4.7y 5x 88 81. 82. 8 3 81. 5x 4y 6z 82. 2.1x 4.7y z In Exercises 83 – 86, determine if any of the planes are parallel In Exercises 83 – 86, determine if any of the planes are parallel In Exercises Exercises 83 83 – 86, determine determine ifif any any of of the the planes planes are are parallel parallel In En los ejercicios– 86, 83 a 86, determinar si algunos de los planos son In Exercises or or identical. oridentical. identical. 83 – 86, determine if any of the planes are parallel or identical. paralelos o idénticos. or identical. 83. 2x 3z 15x 6y 24z 17 83. 84. P11:11::: 2x 2x yyyy 3z 3z 8888 P1:1::: 15x 15x 6y 6y 24z 24z 17 17 84. 83. PPP 84. PPP 2x 3z 15x 6y 24z 17 83. 84. 2x 6y 24z 17 P : y 3z 8 83. PP11:1: 15x 84. 1 PPP 3x 5y 2z 5x 2y 8z P22:22::: 3x 3x 5y 5y 2z 2z 6666 P2222::: 5x 5x 2y 2y 8z 8z 6666 3x 5y 2z PP 5x 2y 8z 3x P : 5x 2y 8z 6 P : 5y 2z 6 2 6x 2 8x PPP PPP 4y 12z 4y 4z P33:33::: 8x 8x 4y 4y 12z 12z 5555 P33:33::: 6x 6x 4y 4y 4z 4z 9999 8x 4y 12z 6x 4y 4z 4y 2z 4z 49 12z 511 3: 6x 3: 8x4x 4y PPP PPP P 2y 6z 11 P 3x 2y 2z P44:44::: 4x 4x 2y 2y 6z 6z 11 11 P44:44::: 3x 3x 2y 2y 2z 2z 444 4x 2y 6z 3x 2y P : 3x 2y 2z 4 P : 4x 2y 6z 11 4: 3x 4 : P 2y 5z 10 85. P 3x 2y 5z 10 85. 3x 2y 2y 5z 5z 10 10 85. PP1111:: 3x 85. 85. PP1: : 3x6x 2y4y 5z10z 10 5 6x 4y 10z P2222::: 6x 6x 4y 4y 10z 10z 555 PP 6x 2y 4y 5z 10z 8 5 2:: PPP 3x : P 3x 2y 5z P3333:: 3x 3x 2y 2y 5z 5z 888 P : 3x 2y 5z 8 3 PPP 75x 50y 125z 250 P44:44::: 75x 75x 50y 50y 125z 125z 250 250 75x 50y 125z 250 75x P : 50y 125z 250 4: P 60x 90y 30z 27 : 86. P 60x 90y 30z 27 86. 60x 90y 90y 30z 30z 27 27 86. PP1111:: 60x 86. 30z 27 86. PP1: : 6x 60x9y 90y 3z 2 P 6x 9y 3z 2 : 2 6x 9y 9y 3z 3z 22 PP222:: 6x 3z 2 2: 6x20x9y 30y PPP P 30y 10z P33:33::: 20x 20x 30y 30y 10z 10z 9999 20x 10z P : 20x 30y 10z 9 3 PPP 12x 18y 6z P4:4::: 12x 12x 18y 18y 6z 6z 5555 12x 18y 6z P444: 12x 18y 6z 5 In In Exercises 87– 90, describe the family of planes represented by InExercises Exercises87– 87–90, 90,describe describethe thefamily familyof ofplanes planesrepresented representedby by In Exercises 87– 90, describe the family of planes represented by In Exercises 87– 90, describe the family of planesde represented by c the equation, where is any real number. c the equation, where is any real number. En los ejercicios 87 a 90, describir a la familia planos reprec the equation, where is any real number. the equation, where c is any real number. c is any the equation, realc number. sentada por lawhere ecuación, donde es cualquier número real. 87. 88. 87. 88. 87. xxxx yyyy zzzz cccc 88. xxxx yyyy cccc 87. 88. x y z c x yy 5 cc0 87. 88. 87. 88. xcy1 yzz1 z005 c 89. 90. cz 000 89. cy 90. xxxxx 1cz cy zz 00 cz 89. 90. cy cz 89. 90. cy 1 zz 5 00 cz 5 00 89. cy 90. xx 1 cz 89. 90. In In Exercises Exercises 91 91 and and 92, 92, (a) (a) find find the the angle angle between between the the two two In Exercises 91 and 92, (a) find the angle between the two In Exercises 91 and 92, (a) find the angle between the two In Exercises 91 and 92,ofof (a) find the equations angle between the two planes, and (b) find aaaaset parametric for the line of planes, and (b) find set parametric equations for the line of planes, and (b) find set of parametric equations for the line of planes, and (b) find set of parametric equations for the line of En los ejercicios 91 y 92, a) encontrar el ángulo entre los dos planes, and (b) find a set of parametric equations for the line of intersection of the planes. intersection of the planes. intersection ofthe theun planes. intersection of planes. planos y b) hallar conjunto de ecuaciones paramétricas de la intersection of the planes. recta 91. 2y 92. 91. 3x 3xde intersección 2y zzzz 7777 de los planos. 92. 6x 6x 3y 3y zzzz 5555 91. 3x 2y 92. 6x 3y 91. 3x 2y 92. 6x 3y 91. x3x 4y2y 2zz 07 92. 6xx 3y z 5 yyyy 15z x 4y 2z 0 x 91. x3x 92. 6xxx2 3y 2y 22z z 5 070 z5z x 14y 4y 2z 5z5 55555 5z x 4y 2z 0 x y 5z 5 x 2 4y 1 2z 5 0 2x 1 y 1 5z 5 5 1053714_1105.qxp10/27/08 10/27/08 10:40 AMPage Page 1053714_1105.qxp 810810 3/12/09 10:40 17:27AM Page 810 10/27/08Larson-11-05.qxd 10:40 AM Page 810 810 Chapter 11 Vectors and the Geometry of Space 810 CAPÍTULO 11 Vectors Vectores y la geometría del Chapter Geometry of espacio Space 810810 Chapter 11 11 Vectors andand thethe Geometry of Space Vectors and the Geometry of Space In Exercises 93 – 96, find the point(s) of intersection (if any) of WRITING ABOUT CONCEPTS (continued) the plane and the line. Also determine whether the line lies in 115. Describe a method for determining when two planes En los ejercicios 93 a 96, hallar el o los de intersección Exercises – 96, find the point(s) of intersection any) of In Exercises 93 –93 96, find the point(s) of puntos intersection (if (if any) of(si theIn plane. I NA G BAOBUde OTUCTconceptos W Desarrollo RWI TRIINT G OCNOCNECPETPST (Sc(continuación) o(nctoi nn ut iendu)e d ) es 93 – 96, find the point(s) of intersection (if any) of los hay) del plano y la recta. Investigar además si la recta se halla plane line. Also determine d1 0 and Wwhether R I T Ithe N Gthe A line Blies O Ulies Tin CinO N C E P 115. T Sa1(xDescribe c o n tbi1nyu e dc) 1z thethe plane andand thethe line. Also determine whether line a method for determining when planes 115. a method for determining when twotwo planes and the line. Also determine whether the line lies 1in y enthe el plane. plano. 3 2 z 1 115.Describe uncplanes método the a2Describir x when b2 ytwo z d2 para0 determinar cuándo dos planos 115. Describe a method for determining 93.plane. 2x 2y z 12, x 2 0 and 21 y 1 1s3y2d z 21 1 a1xa1x b1yb1y c1z c1z d1 d1 0 and a1x(a) 1 bparallel 1 d1(b) 5 0perpendicular. c2z 1 d2your 50 y a x 1 b2 y 1Explain 93. 2x 2 2y 1 z 5 12, x 21 15y y 3 23 2 5 az1x z 1b11y c1z d1 0 and are 1y 1 c1zand a x b y c z d 0 2 2x 2y z 12, x 93. 2 21 2 areasoning. 2x 2 x 2 b2 y 2 c2z 2 d2 2 0 193. y2x 32y 2 z z5,12,1x x 1 2 y2 z 13 1 2 94. 3y 2 a2 x b2 y c2z d2 0 2y z 12, x a) paralelos yand b) Explicar el razoson are (a) parallel (b) perpendicular. Explain your z 62 3 are (a) parallel and (b)perpendiculares. perpendicular. Explain your 2 1 2 x 42 1 2y Let lines that do not intersect. Is L1 and LExplain 94. 2x 1 3y 5 25, x x 1 15y y5z z 3 3 are (a) parallel and (b) 116. 2 be nonparallel namiento. perpendicular. your reasoning. 2x 3y 5, 94. 4 2 6 reasoning. x 1 y 1 94. 2x 3y 5, x 1 95. y 2x z 33y 10, it possible to find a nonzero vector such that is v v 4 2 6 z 3 4 2 6 reasoning. 3y 5, 116. Sean yL Lbe no paralelas que no cortan. ¿Es Is posi116. Let be nonparallel lines do not intersect. Is LL1 1and L2rectas 2 1 2 x 32 1 y 1 116. Let nonparallel lines thatthat do se not intersect. L1 and 4 2 6 perpendicular both and L Explain your reasoning. L ? 2 to 1 2 2 3 Let L1 and L2 be nonparallel linesble 95. 2x 1 3y 5 10, x x 1 15y y 1 15 z116. hallar un intersect. vector vnonzero distinto de cero talsuch que vthat seathat perpenthat do not Isnonzero it possible to find a vector such is v v it possible to find a vector is v v 2x 3y 10, z 3 95. 3 22 x 4 y 1 z 2 10, z 3 x 1 95. y96. 2x 15x 3y 117. Find an vequation of yvthe plane withelxrazonamiento. -intercept a, 0, 0 , dicular a such ambos it possible to find a nonzero vector that 3 3 2 2 perpendicular toLboth and LExplain your reasoning. L?1 Explicar 1 L Lis 2 3y 10, z 3y 3 17, perpendicular to both and L your reasoning. ? 2? Explain 2 3 5 1 2 x24 y11 z12 0, b, 0 , and z-intercept 0, 0, c . (Assume a, 3 2 to both L1 and117. L2?y-intercept Explain your reasoning. 2 96. 5x 1 3y 5 17, x x 4 45y y 1 15z z 2 perpendicular Hallar una ecuación delthe plano con intersección ena,x 0, (a, 0,, 00),, 117. Find equation plane with x-intercept a,00, 117. Find anc an equation of of the plane with x-intercept 5x 3y 17, 96. b, and are nonzero.) 2 23 5 5x 3y 17, 96. x 4 In y Exercises 1 z 97–100, 2 2 3 5 intersección en y (0, b, 0) e intersección en z (0, 0, 117. Find an equation of the plane with x -intercept a, 0, 0 , find the distance between the point and the 2 3 5 y-intercept 0,0b,, 0and , and z-intercept 0,c0,. c(Assume . (Assume a, 3y 17, y-intercept 0, b, z-intercept 0, 0, a, c). 2 5 (Suponer que a, b y c son distintos de cero.) y-intercept b, 0 , and z-intercept 0, 0, c . (Assume a, plane. En3los ejercicios 97 a 100, hallar la distancia del punto al0,plano. b, and c are nonzero.) b, and c are nonzero.) In Exercises 97–100, distance between point and In Exercises 97–100, findfind thethe distance between the point andnonzero.) thethe b, the and c are CAPSTONE es 97–100, find the distance the point and the 98. 0, 0, 0 97. 0,between 0, 0 plane. plane. Para discusión 118. Match the equation or set of equations with the description 2x 3y z 12 5x y z 9 0,00, 0 0,00, 0 C ACPASitPTS OTNOEN E 97.97.0, 0, 98.98.0, 0, represents. 99.98.2, 8, 100. 1, C3,A P1S T O N E 0 0, 40, 0 118. Encontrar laequation correspondencia entre la ecuación o conjunto 118. Match the or set of equations with the description 118. Match theof equation or set of equations 2x 2x 3y 3y z z 12 12 5x 5x y y z z 9 9 (a) Set parametric equations ofdescripción a with line the description de ecuaciones que cumple con la indicada. with the description 3x 118. 2x 5x y y z z 5 9 4y Match 5z the6 equation or set of equations 3y z 12 it represents. it represents. 2,48, 4 1, 3,1 1 99.99.2, 8, 100.100.1, 3, (b) Set of symmetric equations of a line de una recta it represents. a) (a) Conjunto ecuaciones paramétricas 4 100. 1, 3, 1 of de parametric equations a line (a) SetSet of parametric equations of aofline z 5 a5 verify 3x 4y planos 5z 6parallel, 6 paraIn that theque planes 2x 2x y y101–104, z 101 3xtwo 5z are EnExercises los ejercicios 104, verificar los4y dos son (c) Standard equation of a plane in space (a) Set of parametric equations of a line b) Conjunto de ecuaciones simétricas de una recta y z 5 3x 4y 5z 6 (b) Set of symmetric equations of a line (b) Set of symmetric equations of a line and find the distance between theellos. planes. lelos, y hallar la distancia entre General form of an equation ofena el plane in space (b) are Setare of symmetric of aEcuación line Exercises 101–104, verify planes parallel, equations (d) In In Exercises 101–104, verify thatthat thethe twotwo planes parallel, c) estándar de un plano espacio Standard equation a plane in space (c) (c) Standard equation of aofplane in space es 101–104, verify and that the two planes parallel, 101. 102. xxfind 3y 4z4z 5are 10 4x and the planes. 2 3y 1distance 10between 4x 24y 4y (c) 19z9z 577 equation of a planed) 101. 102. find the distance between thethe planes. i)inForma x 6general 2 y 1 3 z 1 Standard space dean la equation ecuación deaof un espacio General form of an equation aplano plane in el space (d) (d) General form of of plane in en space he distance between the planes. xx 23y 4x 3y3y14z4z4z56610 4x4x24y 4y4y(d) 19z9z 518 187 form of an equationii)of a2xplane7yin space 5z 10 0 General x 9z 101. 102. 101. x 3y 4z 10 102. 4x 4y 9z 7 i) i)x x 6 62 2 y y 1 1 3 3 z 1z 1 103. 104. 3x 102.23x 3y 4z 10 4x 16y 4y 9z 6y 17z 7z 5171 2x 24z4z 544 x 6182 103. 104. 2x y 1 3 iii)z 1x 4 7t, y 3 t, z 3 3t x x 3y 3y 4z 4z 6 6 4x 4x 4y 4yi)9z 9z 18 ii) ii)2x 2x 7y 7y 5z 5z 10 10 0 0 6x 12y 2x 3y 4z 6 4y 214z 9z 525 18 6x4x2 12y 14z 25 2x2x24z4z4zii) 510 10 iv) 2(x 1) ( y 3) 4(z 5) 0 2x 7y 5z 10 0 3x 6y 7z 1 4 103. 104. 103. 3x 6y 7z 1 104. 2x 4z 4 y y 3 3 t, z t, z 3 3 3t 3t iii) iii)x x 4 4 7t, 7t, 104. 2x 4z 4 6y 7z 1 iii) x 4 7t, y 3 t, z 3 3t 12y 14z14zfind 10point and In Exercises the distance between the 6x 6x 12y105–108, 25 25 2x 2x 4z 4z 10 iv) 2(x 1) iv) 2(x 1) ( y ( y 3) 3) 4(z 4(z 5) 5) 0 0 En los ejercicios 105 a 108, hallar la distancia del punto a la recta 12y 14z 25 10set the line 2x given 4z by the of parametric equations. iv) 2(x 1) ( y 3) 4(z 5) 0 por medio del conjunto de ecuaciones paramétricas. In Exercises 105–108, distance between point 119. Describe and find an equation for the surface generated by all Indada Exercises 105–108, findfind thethe distance between thethe point andand Describir unafour ecuación para la 119.points es 105–108, find thethe distance between the point and 105. 1, 5, 2 ; x 4t 2, y 3, z t 1 the line given by set of parametric equations. x, y,yz hallar that are units from thesuperficie point 3, generada 2, 5 . por line given by the set of parametric equations. 105. s1, 5, 22d; x 5 4t 2 2, y 5 3, z 5 2t 1 1 119. Describe and find any, equation for the surface generated all todos los puntos (x, z) que están a cuatro unidades del punto ven by the set of parametric equations. 119. Describe and find an equation for the surface generated by by all 106. 1, 2, 4 ; x 2t, y t 3, z 2t 2 120.for Describe and generated find an equation for the surface generated by the surface by all 1,22, 5,2 4; d2; ;x x x54t2t,4t 2,y 2, y 3,3,3,z119. z Describe 105.1,s1,5, 5y t 2 z5 2tt 1t 12 1and find an equation 106. x, y, z 3, 2, 5 . points that are four units from the point s 3, 22, 5 d . 105. pointspoints x, y, z x,that four units from the point 3, 2, 5 . y,3,zarethat 2t x, y, z that are four unitsall 2 ; x 4t 2, 107. y 3, 2,z1, 3 ; t x 1 1 t, y 2 t, z points from the point 2, 5 .are four units from the plane 1,2,1,42,3; d4; ;x x x52t,1 2t, t 3,2 3, 2t 22t 106.1,s22, 2y t, y ty 5 1z t, z 2tz 5 107. 120. Describe find an equation for the surface generated by 120. hallar ecuación superficie generada 106. 2 2 120. Describe find anuna equation forpara thela surface generated bypor 4xDescribir 3y andyzand 10. z 1 t 2, 4 ; x 2t, y 108. t 3,4, z 1, 52t; x2 3, y 1 3t, 120. for thepoints surface byare x,generated y,sx,zthat all four units from the plane todos los puntos que están aunits cuatro unidades del plano y,that zd are 2,31,5; d3; ;x x x51 3,1 t,y t,5 2 t, zt,z5Describe z1 12tt 2t and find an equation 107.s4, all points four from the plane x, y, z 108. 107. 2, 21, 1, y 1y1 2 3t, Modeling Data Per all points x, y, z that 121. are 4x four units the capita plane consumptions (in gallons) of 4x 2 3y 1 10. 4x 3y zz 5 10. 1, 3 ; x 1 t, y 2 t, z 2t 3y z from 10.milk 3,yverify y 1 that 1 3t, 3t, z 1 1are t In 108. Exercises 109 110, the parallel, and different types of in the United States from 1999 through 108. 4, 4,1, 51, ; 5 ;and x x 3, z lines t 4x 3y z 10. 121. Modeling Data Per capita consumptions (in gallons) 1, 5 ; x 3, y find 1En los 3t, ejercicios z 1 between t y 110, 121. Modelado matemático Los consumos perof cápita (en galones) 109 verificar que las rectas son paralelas 121. Modeling Data capita consumptions (in gallons) of of the distance them. 2005 are shown inPer the table. Consumptions flavored milk, Modeling Dataandand Per capita consumptions (in gallons) of In Exercises 110, verify the lines parallel, different types of milk in the United States from 1999 through de diferentes de leche en Unidos desde 1999 hallar la distancia entre ellas. Iny Exercises 109109 andand 110, verify thatthat the121. lines areare parallel, different types oftipos milk in the United States from 1999 through plain reduced-fat milk, and plain lightEstados and skim milks are reprees 109 and 110, verify that lines parallel, and States from 1999 109. :the L1the x distance 2 are t, between y them. 3 them. 2t, z 4 tdifferent types of milk in the United find 2005 are shown in through the Consumptions of flavored milk, hasta 2005 se muestran en la tabla. El ofconsumo de leche find the distance between 2005 areby shown in the table. Consumptions flavored milk, sented the variables x,table. y, and z, respectively. (Source: 2 2yt, y1 5 36t,1 2t, t stance between them.109. LL:1: xx 53t, are shown in the table. Consumptions ofyflavored plain reduced-fat and plain light skim milks are repredescremada semidescremada, leche reducida enare grasas y la plain reduced-fat milk, andmilk, plain light andand skim milks reprez 4z 5 43t12005 Department of milk, Agriculture) 2 t, t,y y 3 3 2t, 2t,z z 4 4 t plain t reduced-fat milk, and plain U.S. 109.109. L1L2: L:x1:x x52 3t, light and skim milks are reprex,por y,las z, respectively. sented by the variables and (Source: y 5 1 2 6t, z 5 4 2 3t leche entera se representa variables x, y y z, respectivasented by the variables x, y, and z, respectively. (Source: 2 2 9t, z 1 12t 2 t, y 3 110. 2t, zL1: x4 3t 6t, y respectively. z,Department L : x 3t, y 1 6t, z 4 4 3t 3tsented by the variables x, y, and U.S. Department of(Source: Agriculture) mente. Department Agriculture) Agriculture) z 5 18t2 12t 110.L2L: :x2 x 53t,3 1y 6t, 1 y 56t,22z1 9t, 1999(Fuente: 2000ofU.S. 2001 2002 of 2003 2004 2005 AñoU.S. 3t, y 1 6t, z110.L42:1 x 3t 1 4t, y 3 6t, z U.S. Department of Agriculture) 3 6t, 6t,y y 2 2 9t, 9t,z z 1 1 12t12t 110. L1L: L:x1:x x53 21 1 4t, y 5 3 1 6t, z 5 28t 2 3 6t, y 2 9t, z 1 12t 1.4 1.4 1.4 1.6 1.6 1.7 1.7 x Año 1999 1999 2000 2000 2001 2001 2002 2002 2003 2003 2004 2004 2005 2005 Año y 3 3 6t, 6t,z z 8t 8t 1B O1U 4t,T 4t,Cy O N W RLI2T: LIx2N: Gx A8t C E P T S Año 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 1 4t, y 3 6t, z 7.31.4 1.4 7.11.4 1.4 7.01.4 1.6 7.01.6 1.6 6.91.6 1.7 6.91.7 1.7 6.91.7 1.4 xy x 111. Give the parametric equations and the symmetric equations I NA G BAOBUde OTUCTconceptos PST S x 1.4 1.4 1.4 1.6 1.6 1.7 1.7 WDesarrollo RWI TRofIINTaG OCNOCNECPETwhat line in space. Describe is required to find these N G A B O U T C O N C E P 111. T S Give the parametric equations and the symmetric equations 6.27.3 7.1 6.17.1 7.0 5.97.0 7.0 5.87.0 6.9 5.66.9 6.9 5.56.9 6.9 5.66.9 7.3 yz y 111. and the symmetric equations 111.Give Darthe lasparametric ecuacionesequations paramétricas y ylas ecuaciones simétriequations. 7.3 7.1 7.0 7.0 6.9 6.9 6.9 e the parametric equations and the equations asymmetric line inrecta space. what is required tosefind these of aofline space. Describe what isDescribir required to find these cas de una enDescribe el espacio. qué requiere 5.9 5.8 5.6 5.5 5.6 6.26.2 6.16.1 z z A model Give thein standard equation of a plane in space. Describe a line in space. Describe112. what is required to find these data 5.9 is 5.6 given 5.8 by 0.92x5.6 1.03y5.5 z 5.6 0.02. equations. equations. 6.2 6.1 5.9 5.8 5.6for the5.5 z para ishallar estastoecuaciones. what required find this equation. ations. (a) Complete a fourth rowestá in dado the table using the model to 112. Give standard equation ofplane a plane inelspace. Describe para losdata datos por 1.03y 112. Give the standard equation of aun Describe 112. Dar la the ecuación estándar de enspace. espacio. Des0.92x 1.03y z z 0.02. 0.02. A modelo model the is given by AUn model for for the data is given byvalues 0.92x Describe aspace. method of finding theplano lineinof intersection of e the standard equation113. of awhat plane in Describe approximate z for the given of x and y. Compare the what is required to find this equation. is required to find this equation. A model for the data is given by 0.92x 1.03y z 0.02. cribir qué se requiere para hallar esta ecuación. two planes. Complete a fourth row in the table using model (a) (a) Complete a fourth row inactual the table using thethe model to to at is required to find this equation. approximations with the values of z. 113. Describe a método method of hallar finding the line ofComplete intersection of row in thea)table Hacer un cuarto renglón de la tabla usando el Compare modelo para 113. Describe aeach method of de finding the line of intersection ofa,fourth (a) aentre using the to 113. Describir un la recta de intersección zmodel x and y. approximate for the given values of the approximate z for the given values of x and y. Compare the 114. Describe surface given by the equations x scribe a method of finding two the line of intersection of (b) According tozCompare this model, any increases in consumption oflas two planes. aproximar con los valores dados de x y y. Comparar planes. approximate z for the given values of x and y. the dos planos. z. approximations with the actual values of approximations with the actual values of z. y b, and z c. planes. two types will los havevalores what effect aproximaciones realesondethe z. consumption approximations values of z.of milk con 114. Describe each surface given by the equations a,with the actual(b) 114. Describe each surface given thelas equations x xx 5 a, a, 114. Describir toda superficie dadabypor ecuaciones According to this model, increases in consumption (b) According totype? this model, anyany increases in consumption of of of the third scribe each surface given ybyy y5the equations x a, b, b) Según este modelo, cualquier incremento elconsumption consumo de b,band z5 zc.c. c. (b) According to this model, any increases in consumption ofhave y zand two types of milk will what effect onen the two types of milk will have what effect on the consumption b, and z c. dos deconsumption leche two types of milk will have whatofeffect on third the of tipos the type?tendrá ¿qué efecto en el consumo del terthe third type? cer tipo? of the third type? Chapter 11 Larson-11-05.qxd 1053714_1105.qxp 3/12/09 10/27/08 17:27 Page 811 10:40 AM Page 811 SECCIÓN 11.5 122. Diseño industrial Un colector en la parte superior de un montacargas de grano canaliza el grano a un contenedor. Hallar ángulo entreDesign dos ladosThe adyacentes. 122.elMechanical figure shows a chute at the top of a grain elevator of a combine that funnels the grain into a bin. 8 pulg 8 pulgthe angle between two adjacent sides. Find 11.5 Lines and Planes in Space 811 124. Hallar la ecuación estándar de la esfera con el centro en (23, 2, 4) que es tangente al plano dado por 2x 1 4y 2 3z 5 8. 2 center y 1 4z共⫺3, 5 7 2,con 125. el punto de intersección 4兲 124. Hallar Find the standard equation of del the plano sphere3x with lathat recta que pasa (5, 4, given 23) yby que 2xes⫹perpendicular 4y ⫺ 3z ⫽ 8.a este is tangent to por the plane 125. plano. Find the point of intersection of the plane 3x ⫺ y ⫹ 4z ⫽ 7 126. Mostrar plano 共2x es paralelo a latorecta y 2兲 3z 5, 2 4, ⫺3 and the que lineelthrough that5is4 perpendicular this xplane. 5 22 1 2t, y 5 21 1 4t, z 5 4, y hallar la distancia entre 126. ambos. Show that the plane 2x ⫺ y ⫺ 3z ⫽ 4 is parallel to the line 8 in. 8 in. 811 Rectas y planos en el espacio 8 pulg 8 in. 6 pulg 6 pulg 6 in. a lo largo de rectas dife123. Distancia Dos insectos se arrastran 6 in. rentes en el espacio. En el instante t (en minutos), el primer está Two en elinsects punto are (x, crawling y, z) sobre la recta x 5lines 6 1 t,in 123.insecto Distance along different También, en el instante t, el segundo y three-space. 5 8 2 t, zAt 5 time 3 1 t.t (in minutes), the first insect is at the insecto el punto sobre la 8recta point 共está the line(x,x y, x, y, en z兲 on ⫽ z) 6⫹ t, y ⫽ ⫺ t, xz5 ⫽131 ⫹t,t. y Also, 521 5the 2t. second insect is at the point 共x, y, z兲 on the at t,timez t, Suponer last,distancias en pulgadas. line x ⫽que 1⫹ y ⫽ 2 ⫹ t,sez dan ⫽ 2t. a)Assume Hallar that la distancia los dos insectos en el instante distancesentre are given in inches. 0. the distance between the two insects at time t ⫽ 0. (a)t 5 Find b)(b)Usar herramienta de graficación para representar la disUseuna a graphing utility to graph the distance between the tancia entre los tinsectos ⫽ 0 to tdesde ⫽ 10.t 5 0 hasta t 5 10. insects from c)(c)Usando gráfica delfrom inciso b), (b), ¿quéwhat se puede acerUsinglathe graph part can concluir you conclude ca about de la distancia entre los insectos? the distance between the insects? 127. Hallar intersección por x ⫽ ⫺2el ⫹punto 2t, y de ⫽ ⫺1 ⫹ 4t, z ⫽de4, laandrecta findque the pasa distance (1, 23, 1)them. y (3, 24, 2), y el plano dado por x 2 y 1 z 5 2. between 128. un conjunto de ecuaciones de la共1, recta ⫺3,que 1兲 127. Hallar Find the point of intersection of paramétricas the line through pasa el punto 2) ygiven es paralela plano 3, ⫺4, 2兲, and(1, z ⫽ dado 2. por and 共por the0,plane by x ⫺aly ⫹ la the recta 1 y a1setz of 5 parametric 5, y perpendicular x5 t, y 5through 1 1 t, 128. xFind equationsa for line passing zthe 5 1point 1 t. 共1, 0, 2兲 that is parallel to the plane given by x ⫹ y ⫹ z ⫽ 5, and perpendicular to the line x ⫽ t, ¿Verdadero y ⫽ 1 o⫹falso? t, z ⫽ 1En ⫹los t. ejercicios 129 a 134, determinar si la declaración es verdadera o falsa. Si es falsa, explicar por qué o dar unorejemplo que129–134, es falsa. determine whether the True False? que In pruebe Exercises statement false. If it is false, explain why or give an 129. Si v 5isa1true i 1 bor 1j 1 c1k es cualquier vector en el plano dado por example a x 1that b yshows 1 c z it 1isd false. 5 0, entonces a a 1 b b 1 c c 5 0. 2 2 2 2 1 2 1 2 1 2 i ⫹rectas b1j ⫹encel 129. Todo If v ⫽ is any ovector in the plane given by 130. para1de se cortan o son paralelas. 1k espacio a x ⫹ b y ⫹ c z ⫹ d ⫽ 0, a a ⫹ b b ⫹ c c then 2 2 2 2 1 2 1 2 1 2 131. Dos planos en el espacio o se cortan o son paralelos. ⫽ 0. 132. dos rectas son paralelas un plano P, or entonces L1 yinL2space 130. Si Every two lines are eithera intersecting parallel.L1 y paralelas. 2 sonplanes 131. LTwo in space are either intersecting or parallel. 133. planos a un tercer en then el espacio L1 and L2 are parallel L1 andson 132.Dos If two linesperpendiculares to a plano plane P, L2 paralelos. are parallel. 134. plano y una recta en el to espacio intersecan sonparallel. parale133.Un Two planes perpendicular a thirdse plane in spaceo are los. 134. A plane and a line in space are either intersecting or parallel. d)(d)¿Qué setoacercan los insectos? Howtanto close each other do the insects get? PROYECTO S E C T I ODE N TRABAJO PROJECT Distances en in Space Distancias el espacio En estahave sección se hantwo vistodistance dos fórmulas para distancia, la distancia You learned formulas in this section—the dedistance un puntobetween a un plano, y la distancia de un punto una recta. En estea a point and a plane, and the adistance between proyecto se estudiará tercer problema distancias, distancia de point and a line. Inunthis project you de will study a lathird distance dos rectas que se cruzan. Dos rectas en el espacio son oblicuas si no problem—the distance between two skew lines. Two lines in space son ni seare cortan (verparallel la figura). areparalelas skew if they neither nor intersecting (see figure). a)(a)Considerar las siguientes dos enspace. el espacio. Consider the following two rectas lines in L1L:1x: x5⫽4 41⫹5t,5t,y y5⫽5 51⫹5t,5t,z z5⫽1 12⫺4t4t L2L:2x: x5⫽4 41⫹s,s,y y5⫽26 ⫺61⫹8s, 8s,z z5⫽7 72⫺3s3s i)(i)Mostrar que these estas lines rectasare nonot sonparallel. paralelas. Show that ii) Mostrar que estas rectas no se cortan, y por consi(ii) Show that these lines do not intersect, and therefore are guiente las rectas se cruzan. skew lines. iii) Mostrar que las dos rectas están en planos paralelos. (iii) Showlathat the twoentre lineslos lie planos in parallel planes.del inciso iv) Hallar distancia paralelos (iv)iii). Find thees distance between thelas parallel part Ésta la distancia entre rectasplanes que sefrom cruzan (iii). This is the distance between the original skew originales. b) Usar ellines. procedimiento del inciso a) para encontrar la distan(b)ciaUse thelasprocedure entre rectas. in part (a) to find the distance between Lthe : x lines. 5 2t, y 5 4t, z 5 6t 1 4t,4 z1⫽s,6tz 5 21 1 s L2L:1x: x5⫽1 2t, 2 s,y ⫽ y5 L2: x ⫽ 1 ⫺ s, y ⫽ 4 ⫹ s, z ⫽ ⫺1 ⫹ s c)(c)Usar procedimiento parathe encontrar distanUseelthe procedure in del partinciso (a) toa)find distancelabetween cia las rectas. theentre lines. LL11::xx 5 ⫽ 3t, 3t, yy 5 ⫽ 22 2 ⫺ t,t, zz 5 ⫽ 21 ⫺11 ⫹tt LL22::xx 5 ⫽ 11 1 ⫹ 4s, 4s, yy 5 ⫽ 22 ⫺2 1 ⫹ s,s, zz 5 ⫽ 23 ⫺3 2 ⫺ 3s 3s d) fórmula encontrar la distancia de the las (d)Desarrollar Develop auna formula for para finding the distance between rectas skewoblicuas. lines. LL11::xx 5 ⫽ xx11 1 ⫹ aa11t,t, yy 5 ⫽ yy11 1 ⫹ bb11t,t, zz 5 ⫽ zz11 1 ⫹ cc11tt LL22::xx 5 ⫽ xx22 1 ⫹ aa22s,s, yy 5 ⫽ yy22 1 ⫹ bb22s,s, zz 5 ⫽ zz22 1 ⫹ cc22ss L1 L2 Larson-11-06.qxd 812 3/12/09 17:31 CAPÍTULO 11 Page 812 Vectores y la geometría del espacio 11.6 Superficies en el espacio n n n Reconocer y dar las ecuaciones de superficies cilíndricas. Reconocer y dar las ecuaciones de superficies cuádricas. Reconocer y dar las ecuaciones de superficies de revolución. Superficies cilíndricas z Las primeras cinco secciones de este capítulo contienen la parte vectorial de los conocimientos preliminares necesarios para el estudio del cálculo vectorial y del cálculo en el espacio. En ésta y en la próxima sección, se estudian superficies en el espacio y sistemas alternativos de coordenadas para el espacio. Ya se han estudiado dos tipos especiales de superficies. y x 1. Esferas: sx 2 x0d2 1 s y 2 y0d2 1 sz 2 z0d2 5 r 2 2. Planos: ax 1 by 1 cz 1 d 5 0 Sección 11.2. Sección 11.5. Un tercer tipo de superficie en el espacio son las llamadas superficies cilíndricas, o simplemente cilindros. Para definir un cilindro, considerar el familiar cilindro circular recto mostrado en la figura 11.56. Se puede imaginar que este cilindro es generado por una recta vertical que se mueve alrededor del círculo x2 1 y 2 5 a2 que se encuentra en el plano xy. A este círculo se le llama curva directriz (o curva generadora). Cilindro circular recto: x2 + y2 = a2 Las rectas generatrices son paralelas al eje z Figura 11.56 DEFINICIÓN DE UN CILINDRO Sea C una curva en un plano y sea L una recta no paralela a ese plano. Al conjunto de todas las rectas paralelas a L que cortan a C se le llama un cilindro. A C se le llama la curva generadora (o la directriz) del cilindro y a las rectas paralelas se les llama rectas generatrices. Recta generatriz que corta a C z Curva directriz C NOTA Sin pérdida de generalidad, se puede suponer que C se encuentra en uno de los tres planos coordenados. En este texto se restringe la discusión a cilindros rectos, es decir, a cilindros cuyas (rectas) generatrices son perpendiculares al plano coordenado que contiene a C, como se muestra en la figura 11.57. n La ecuación de la (curva) directriz del cilindro circular recto mostrado en la figura 11.56 es x y Cilindro: las rectas generatrices cortan a C y son paralelas a la recta dada Figura 11.57 x2 1 y 2 5 a2. Ecuación de la curva directriz en el plano xy. Para encontrar una ecuación del cilindro, hay que observar que se puede generar cualquiera de las (rectas) generatrices fijando los valores de x y y y dejando que z tome todos los valores reales. En este caso, el valor de z es arbitrario y, por consiguiente, no está incluido en la ecuación. En otras palabras, la ecuación de este cilindro simplemente es la ecuación de su curva generadora o directriz. x2 1 y 2 5 a2 Ecuación de un cilindro en el espacio. ECUACIÓN DE UN CILINDRO La ecuación de un cilindro cuyas rectas generatrices son paralelas a uno de los ejes coordenados contiene sólo las variables correspondientes a los otros dos ejes. Larson-11-06.qxd 3/12/09 17:31 Page 813 SECCIÓN 11.6 EJEMPLO 1 813 Superficies en el espacio Trazado de cilindros Trazar la superficie representada por cada una de las ecuaciones. a) z 5 y 2 b) z 5 sen x, 0 ≤ x ≤ 2p Solución a) La gráfica es un cilindro cuya directriz, z 5 y 2, es una parábola en el plano yz. Las generatrices del cilindro son paralelas al eje x, como se muestra en la figura 11.58a. b) La gráfica es un cilindro generado por la curva del seno en el plano xz. Las generatrices son paralelas al eje y, como se muestra en la figura 11.58b. La directriz C está en el plano yz La directriz C está en el plano xz z z 1 y π y x x Cilindro: z = y2 a) Las generatrices son paralelas al eje x Cilindro: z = sen x b) Las generatrices son paralelas al eje y Figura 11.58 Superficies cuádricas AYUDA DE ESTUDIO En la tabla de las páginas 814 y 815 se muestra sólo una de las varias orientaciones posibles de cada superficie cuádrica. Si la superficie está orientada a lo largo de un eje diferente, su ecuación estándar cambiará consecuentemente, como se ilustra en los ejemplos 2 y 3. El hecho de que los dos tipos de paraboloides tengan una variable elevada a la primera potencia puede ser útil al clasificar las superficies cuádricas. Los otros cuatro tipos de superficies cuádricas básicas tienen ecuaciones que son de segundo grado en las tres variables. El cuarto tipo básico de superficies en el espacio son las superficies cuádricas. Éstas son los análogos tridimensionales de las secciones cónicas. SUPERFICIES CUÁDRICAS La ecuación de una superficie cuádrica en el espacio es una ecuación de segundo grado en tres variables. La forma general de la ecuación es Ax2 1 By2 1 Cz2 1 Dxy 1 Exz 1 Fyz 1 Gx 1 Hy 1 Iz 1 J 5 0. Hay seis tipos básicos de superficies cuádricas: elipsoide, hiperboloide de una hoja, hiperboloide de dos hojas, cono elíptico, paraboloide elíptico y paraboloide hiperbólico. A la intersección de una superficie con un plano se le llama la traza de la superficie en el plano. Para visualizar una superficie en el espacio, es útil determinar sus trazas en algunos planos elegidos inteligentemente. Las trazas de las superficies cuádricas son cónicas. Estas trazas, junto con la forma canónica o estándar de la ecuación de cada superficie cuádrica, se muestran en la tabla de las páginas 814 y 815. Larson-11-06.qxd 814 3/12/09 17:31 CAPÍTULO 11 Page 814 Vectores y la geometría del espacio Elipsoide z z Traza y x Traza yz Traza xz x2 y2 z2 1 21 251 2 a b c Plano Elipse Paralelo al plano xy Elipse Paralelo al plano xz Elipse Paralelo al plano yz La superficie es una esfera si a 5 b 5 c Þ 0. y x Traza xy Hiperboloide de una hoja z z x2 y2 z2 1 22 251 2 a b c Traza Plano Elipse Hipérbola Hipérbola Paralelo al plano xy Paralelo al plano xz Paralelo al plano yz El eje del hiperboloide corresponde a la variable cuyo coeficiente es negativo. y x Traza xy y x Traza yz Traza xz Hiperboloide de dos hojas z x Traza yz z2 x2 y2 2 22 251 2 c a b y Traza Plano Elipse Hipérbola Hipérbola Paralelo al plano xy Paralelo al plano xz Paralelo al plano yz El eje del hiperboloide corresponde a la variable cuyo coeficiente es positivo. No hay traza en el plano coordenado perpendicular a este eje. x Paralela al plano xy z Traza xz No hay traza xy y Larson-11-06.qxd 26/2/10 14:15 Página 815 SECCIÓN 11.6 Cono elíptico z 2 2 z Traza xz 2 x y z ⫹ ⫺ ⫽0 a2 b2 c2 y x Traza Plano Elipse Hipérbola Hipérbola Paralelo al plano xy Paralelo al plano xz Paralelo al plano yz El eje del cono corresponde a la variable cuyo coeficiente es negativo. Las trazas en los planos coordenados paralelos a este eje son rectas que se cortan. 815 Superficies en el espacio Traza xy (un punto) y x Paralelo al plano xy Traza yz Paraboloide elíptico z z⫽ x2 y2 2 ⫹ 2 a b Traza Plano Elipse Parábola Parábola Paralelo al plano xy Paralelo al plano xz Paralelo al plano yz El eje del paraboloide corresponde a la variable elevada a la primera potencia. z Paralelo al plano xy y x Traza xz Traza yz Traza xy (un punto) x y Paraboloide hiperbólica z z⫽ y x y2 x2 ⫺ 2 2 b a Traza Plano Hipérbola Parábola Parábola Paralelo al plano xy Paralelo al plano xz Paralelo al plano yz z Traza yz y x El eje del paraboloide corresponde a la variable elevada a la primera potencia. Paralelo al plano xy Traza xz Larson-11-06.qxd 816 3/12/09 17:31 CAPÍTULO 11 Page 816 Vectores y la geometría del espacio Para clasificar una superficie cuádrica, se empieza por escribir la superficie en la forma canónica o estándar. Después, se determinan varias trazas en los planos coordenados o en planos paralelos a los planos coordenados. EJEMPLO 2 Trazado de una superficie cuádrica Clasificar y dibujar la superficie dada por 4x 2 2 3y 2 1 12z2 1 12 5 0. Solución Se empieza por escribir la ecuación en forma canónica o estándar. 4x 2 2 3y 2 1 12z 2 1 12 5 0 x2 23 y2 z2 − =1 4 1 1 y2 4 Escribir la ecuación original. 2 z2 2 1 5 0 Dividir entre 212. y 2 x 2 z2 2 2 51 4 3 1 z y2 x2 − =1 4 3 3 Forma canónica o estándar. De la tabla en las páginas 814 y 815 se puede concluir que la superficie es un hiperboloide de dos hojas con el eje y como su eje. Para esbozar la gráfica de esta superficie, conviene hallar las trazas en los planos coordenados. 2 1 4 x 3 2 1 2 y Traza xy sz 5 0d: y2 x2 2 51 4 3 Hipérbola. Traza xz s y 5 0d: x2 z2 1 5 21 3 1 No hay traza. Traza yx sx 5 0d: y2 z2 2 51 4 1 Hipérbola. Hiperboloide de dos hojas: y2 x2 − − z2 = 1 4 3 Figura 11.59 La gráfica se muestra en la figura 11.59. EJEMPLO 3 Trazado de una superficie cuádrica Clasificar y dibujar la superficie dada por x 2 y 2 2 4z 2 5 0. Paraboloide elíptico: x = y2 + 4z2 z Solución Como x está elevada sólo a la primera potencia, la superficie es un paraboloide. El eje del paraboloide es el eje x. En la forma canónica o estándar, la ecuación es 2 −4 x = y2 2 4 y x 5 y2 1 4z2. Forma canónica o estándar. Algunas trazas útiles son las siguientes. y2 + z2 = 1 4 1 10 x x = 4z2 Figura 11.60 Traza xy s z 5 0d: x 5 y2 Parábola. Traza xz s y 5 0d: x5 Parábola. Paralelo al plano yz sx 5 4d: y2 4 4z2 1 z2 1 51 Elipse. La superficie es un paraboloide elíptico, como se muestra en la figura 11.60. Algunas ecuaciones de segundo grado en x, y y z no representan ninguno de los tipos básicos de superficies cuádricas. He aquí dos ejemplos. x2 1 y2 1 z2 5 0 x2 1 y2 5 1 Un único punto. Cilindro recto circular. Larson-11-06.qxd 3/12/09 17:31 Page 817 SECCIÓN 11.6 817 Superficies en el espacio En el caso de una superficie cuádrica no centrada en el origen, se puede formar la ecuación estándar completando cuadrados, como se muestra en el ejemplo 4. (x − 2)2 (y + 1)2 (z − 1)2 + + =1 4 2 4 EJEMPLO 4 Una superficie cuádrica no centrada en el origen z Clasificar y dibujar la superficie dada por 3 x 2 1 2y 2 1 z2 2 4x 1 4y 2 2z 1 3 5 0. Solución (2, −1, 1) 1 Al completar el cuadrado de cada variable se obtiene: sx2 2 4x 1 d 1 2s y 2 1 2y 1 d 1 sz2 2 2z 1 d 5 23 sx2 2 4x 1 4d 1 2s y 2 1 2y 1 1d 1 sz2 2 2z 1 1d 5 23 1 4 1 2 1 1 sx 2 2d2 1 2s y 1 1d2 1 sz 2 1d2 5 4 sx 2 2d2 s y 1 1d2 sz 2 1d2 1 1 51 4 2 4 y −1 5 x Un elipsoide centrado en s2, 2 1, 1d Figura 11.61 En esta ecuación se puede ver que la superficie cuádrica es un elipsoide centrado en el punto (2, 21, 1). Su gráfica se muestra en la figura 11.61. Un sistema algebraico por computadora puede ayudar a visualizar una superficie en el espacio.* La mayoría de estos sistemas algebraicos por computadora crean ilusiones tridimensionales dibujando varias trazas de la superficie y aplicando una rutina de “línea oculta” que borra las porciones de la superficie situadas detrás de otras. Abajo se muestran dos ejemplos de figuras que se generaron con Mathematica. TECNOLOGÍA z z y y x x Creado con Mathematica Paraboloide elíptico y2 z2 x5 1 2 2 Creado con Mathematica Paraboloide hiperbólico y2 x2 z5 2 16 16 Usar una herramienta de graficación para representar una superficie en el espacio requiere práctica. En primer lugar, se debe saber lo suficiente sobre la superficie en cuestión para poder especificar que dé una vista representativa de la superficie. También, a menudo se puede mejorar la vista de una superficie girando los ejes. Por ejemplo, se observa que el paraboloide elíptico de la figura se ve desde un punto más “alto” que el utilizado para ver el paraboloide hiperbólico. * Algunas graficadoras 3-D requieren que se den las superficies mediante ecuaciones paramétricas. Para un análisis de esta técnica, ver la sección 15.5. Larson-11-06.qxd 818 3/12/09 17:31 CAPÍTULO 11 Page 818 Vectores y la geometría del espacio Superficies de revolución Sección circular z El quinto tipo especial de superficie que se estudiará se llama superficie de revolución. En la sección 7.4 se estudió un método para encontrar el área de tales superficies. Ahora se verá un procedimiento para hallar su ecuación. Considerar la gráfica de la función radio Curva generadora o directriz y = r(z) (0, 0, z) (0, r(z), z) (x, y, z) y 5 r szd Curva generadora o directriz. r (z) y en el plano yz. Si esta gráfica se gira sobre el eje z, forma una superficie de revolución, como se muestra en la figura 11.62. La traza de la superficie en el plano z 5 z 0 es un círculo cuyo radio es r sz0d y cuya ecuación es x 2 1 y 2 5 fr sz 0dg 2. Traza circular en el plano: z 5 z 0. x Sustituyendo z 0 por z se obtiene una ecuación que es válida para todos los valores de z. De manera similar, se pueden obtener ecuaciones de superficies de revolución para los otros dos ejes, y los resultados se resumen como sigue. Figura 11.62 SUPERFICIE DE REVOLUCIÓN Si la gráfica de una función radio r se gira sobre uno de los ejes coordenados, la ecuación de la superficie de revolución resultante tiene una de las formas siguientes. 1. Girada sobre el eje x: y 2 1 z2 5 frsxdg 2 2. Girada sobre el eje y: x 2 1 z2 5 frs ydg 2 3. Girada sobre el eje z: x 2 1 y 2 5 fr szdg 2 EJEMPLO 5 Hallar una ecuación para una superficie de revolución a) Una ecuación para la superficie de revolución generada al girar la gráfica de y5 1 z Función radio. en torno al eje z es x2 1 y2 5 fr szdg 2 z Superficie: x2 + z2 = 1 y3 9 x2 1 y2 5 11z 2 . Girada en torno al eje z. 2 Sustituir r(z) para 1/z. b) Para encontrar una ecuación para la superficie generada al girar la gráfica de 9x2 5 y3 en torno al eje y, se despeja x en términos de y. Así se obtiene y x x 5 13 y 3y2 5 r s yd. Función radio. Por tanto, la ecuación para esta superficie es Curva generadora o directriz 9x2 = y3 Figura 11.63 x2 1 z2 5 fr s ydg 2 Girada en torno al eje y. x2 1 z2 5 s Sustituir 13 y 3y2 para r syd. d 1 3y2 2 3y x2 1 z2 5 19 y 3. Ecuación de la superficie. La gráfica se muestra en la figura 11.63. Larson-11-06.qxd 3/12/09 17:31 Page 819 SECCIÓN 11.6 819 Superficies en el espacio La curva generadora o directriz de una superficie de revolución no es única. Por ejemplo, la superficie x2 1 z2 5 e22y puede generarse al girar la gráfica de x 5 e2y en torno al eje y o la gráfica de z 5 e2y sobre el eje y, como se muestra en la figura 11.64. z z Superficie: x2 + z2 = e−2y Curva generadora o directriz en el plano yz z = e−y y x y x Curva generadora o directriz en el plano xy x = e−y Figura 11.64 EJEMPLO 6 Hallar una directriz para una superficie de revolución Hallar una directriz y el eje de revolución de la superficie dada por x2 1 3y2 1 z2 5 9. Directriz en el plano xy x= 9 − 3y2 z Directriz en el plano yz z= Solución 9 − 3y2 Se sabe ahora que la ecuación tiene una de las formas siguientes. x2 1 y2 5 fr szdg 2 y2 1 z2 5 fr sxdg 2 x2 1 z2 5 fr s ydg 2 Girada en torno al eje z. Girada en torno al eje x. Girada en torno al eje y. Como los coeficientes de x2 y z2 son iguales, se debe elegir la tercera forma y escribir x2 1 z2 5 9 2 3y 2. y El eje y es el eje de revolución. Se puede elegir una directriz de las trazas siguientes. x x2 5 9 2 3y2 z2 5 9 2 3y 2 Traza en el plano xy. Traza en el plano yz. Por ejemplo, usando la primer traza, la directriz es la semielipse dada por Superficie: x2 + 3y2 + z2 = 9 Figura 11.65 x 5 !9 2 3y2. Directriz. La gráfica de esta superficie se muestra en la figura 11.65. Larson-11-06.qxd 820 3/12/09 17:31 CAPÍTULO 11 Page 820 Vectores y la geometría del espacio 11.6 Ejercicios c) En los ejercicios 1 a 6, asociar la ecuación con su gráfica. [Las gráficas están marcadas a), b), c), d), e) y f).] a) b) z z y 6 3 2 4 x 2 3 x 56 4 y y 4 x −3 x Figuras para 17 CAS z c) z d) −5 4 b) s0, 10, 0d 2 c) s10, 10, 10d 2 4 5 x y z e) 1. 3 2 21. 16x 2 y 4 5 −3 4 4 5. 4x 2 2 4y 1 z 2 5 0 11. x2 13. 4x 2 15. z y 0 12. y2 y2 4 14. y 2 sen y 0 16. z 2 z2 z 25 ey z b) z2 25 18y2 26. z 27. x 2 y2 z 0 28. 3z 32. 9x CAS y2 x2 y 2 16z 2 9z 2 32x 54x 36y 4y 54z 35. z 2 0 2z 2 0 4 0 En los ejercicios 33 a 42, usar un sistema algebraico por computadora para representar gráficamente la superficie. (Sugerencia: Puede ser necesario despejar z y considerar dos ecuaciones al representar gráficamente la superficie.) 33. z 16 1 x2 2y 2 36 2 4y 2 y2 30. x 2 9 9y 2 2 x2 1 18z2 y2 4 x2 6 z2 17. Para pensar Las cuatro figuras son gráficas de la superficie cuádrica z 5 x 2 1 y 2. Asociar cada una de las cuatro gráficas con el punto en el espacio desde el cual se ve el paraboloide. Los cuatro puntos son (0, 0, 20), (0, 20, 0), (20, 0, 0) y (10, 10, 20). a) 24. z 2 1 0 31. 16x 2 10. x 2 9 z2 y2 25 8x2 22. z2 4. y 2 5 4x 2 1 9z 2 8. z z2 y2 4 x2 16 y 29. z 2 6. 4x 2 2 y 2 1 4z 5 0 5 16z 2 20. 25. x 2 2. 15x 2 2 4y 2 1 15z 2 5 24 En los ejercicios 7 a 16, describir y dibujar la superficie. 9. y 2 1 y x 3. 4x 2 2 y 2 1 4z 2 5 4 z2 y2 23. 4x2 x2 y2 z2 1 1 51 9 16 9 7. y y2 4 19. x 2 z f) 2 x En los ejercicios 19 a 32, identificar y dibujar la superficie cuádrica. Usar un sistema algebraico por computadora para confirmar su dibujo. y 6 x 3 2 1 4 18. Usar un sistema algebraico por computadora para representar gráficamente el cilindro y 2 1 z 2 5 4 desde cada punto. a) s10, 0, 0d 4 3 z d) 37. x 2 39. z 41. 6x2 2 cos x x2 y2 10 4y2 34. z 7.5y 2 2 z x2 0.5y 2 x2 36. 3.25y z2 2 38. x 2 40. z xy 6z2 36 42. 9x 2 y2 8 e x x2 4y 2 z y2 8z 2 72 z En los ejercicios 43 a 46, dibujar la región limitada por las gráficas de las ecuaciones. 43. z 5 2!x 2 1 y 2, z 5 2 44. z 5 !4 2 x 2, y 5 !4 2 x 2, x 5 0, y 5 0, z 5 0 y x y 45. x 2 1 y 2 5 1, x 1 z 5 2, z 5 0 46. z 5 !4 2 x 2 2 y 2, y 5 2z, z 5 0 Larson-11-06.qxd 3/12/09 17:31 Page 821 SECCIÓN 11.6 En los ejercicios 47 a 52, hallar una ecuación para la superficie de revolución generada al girar la curva en el plano coordenado indicado sobre el eje dado. Ecuación de la curva Plano coordenado Eje de revolución 47. z 2 5 4y Plano yz Eje y 48. z 5 3y Plano yz Eje y 49. z 5 2y Plano yz Eje z 50. 2z 5 !4 2 x 2 Plano xz Eje x 51. xy 5 2 Plano xy Eje x 52. z 5 ln y Plano yz Eje z Superficies en el espacio 821 64. El conjunto de todos los puntos equidistantes del punto (0, 0, 4) y del plano xy. 65. Geografía Debido a las fuerzas causadas por su rotación, la Tierra es un elipsoide oblongo y no una esfera. El radio ecuatorial es de 3 963 millas y el radio polar es de 3 950 millas. Hallar una ecuación del elipsoide. (Suponer que el centro de la Tierra está en el origen y que la traza formada por el plano z 5 0 corresponde al ecuador.) 66. Diseño de máquinas La parte superior de un buje de caucho, diseñado para absorber las vibraciones en un automóvil, es la superficie de revolución generada al girar la curva z 5 12 y2 1 1 s0 ≤ y ≤ 2d en el plano yz en torno al eje z. a) Hallar una ecuación de la superficie de revolución. En los ejercicios 53 y 54, hallar una ecuación de una directriz dada la ecuación de su superficie de revolución. 53. x 2 1 y 2 2 2z 5 0 54. x 2 1 z 2 5 cos2 y Desarrollo de conceptos 55. Dar la definición de un cilindro. 56. ¿Qué es la traza de una superficie? ¿Cómo encuentra una traza? 57. Identificar las seis superficies cuádricas y dar la forma estándar de cada una. Para discusión 58. ¿Qué representa la ecuación z 5 x 2 en el plano xz? ¿Qué representa en el espacio? b) Todas las medidas están en centímetros y el buje es fijo en el plano xy. Usar el método de capas para encontrar su volumen. c) El buje tiene un orificio de 1 centímetro de diámetro que pasa por su centro y en paralelo al eje de revolución. Hallar el volumen del buje de caucho. 67. Determinar la intersección del paraboloide hiperbólico z = y2yb2 – x2ya2 con el plano bx 1 ay 2 z 5 0. (Suponer a, b > 0.) 68. Explicar por qué la curva de intersección de las superficies x 2 1 3y 2 2 2z 2 1 2y 5 4 y 2x 2 1 6y 2 2 4z 2 2 3x 5 2 se encuentra en un plano. ¿Verdadero o falso? En los ejercicios 69 a 72, determinar si la declaración es verdadera o falsa. Si es falsa, explicar por qué o dar un ejemplo que pruebe su falsedad. 69. Una esfera es un elipsoide. En los ejercicios 59 y 60, usar el método de las capas para encontrar el volumen del sólido que se encuentra debajo de la superficie de revolución y sobre el plano xy. 59. La curva z 5 4x 2 x 2 en el plano xz se gira en torno al eje z. 60. La curva z 5 sen sin y s0 ≤ y ≤ pd en el plano yz se gira en torno al eje z. En los ejercicios 61 y 62, analizar la traza cuando la superficie 70. La directriz de una superficie de revolución es única. 71. Todas las trazas de un elipsoide son elipses. 72. Todas las trazas de un hiperboloide de una hoja son hiperboloides. 73. Para pensar Abajo se muestran tres tipos de superficies “topológicas” clásicas. La esfera y el toro tienen “interior” y “exterior”. ¿Tiene la botella de Klein interior y exterior? Explicar. z 5 12 x 2 1 14 y 2 se corta con los planos indicados. 61. Hallar las longitudes de los ejes mayor y menor y las coordenadas del foco de la elipse generada cuando la superficie es cortada por los planos dados por a) z 5 2 y b) z 5 8. Esfera Toro 62. Hallar las coordenadas del foco de la parábola formada cuando la superficie se corta con los planos dados por a) y 5 4 y b) x 5 2. En los ejercicios 63 y 64, hallar una ecuación de la superficie que satisface las condiciones e identificar la superficie. 63. El conjunto de todos los puntos equidistantes del punto (0, 2, 0) y del plano y 5 22. Botella de Klein Botella de Klein Larson-11-07.qxd 822 3/12/09 17:44 CAPÍTULO 11 Page 822 Vectores y la geometría del espacio 11.7 Coordenadas cilíndricas y esféricas n n Usar coordenadas cilíndricas para representar superficies en el espacio. Usar coordenadas esféricas para representar superficies en el espacio. Coordenadas cilíndricas Coordenadas cilíndricas: r2 = x2 + y2 y tan θ = x z=z z Coordenadas rectangulares: x = r cos θ y = r sen θ z=z x y x EL SISTEMA DE COORDENADAS CILÍNDRICAS En un sistema de coordenadas cilíndricas, un punto P en el espacio se representa por medio de una terna ordenada sr, u, zd. (x, y, z) P (r, θ , z) r θ Ya se ha visto que algunas gráficas bidimensionales son más fáciles de representar en coordenadas polares que en coordenadas rectangulares. Algo semejante ocurre con las superficies en el espacio. En esta sección se estudiarán dos sistemas alternativos de coordenadas espaciales. El primero, el sistema de coordenadas cilíndricas, es una extensión de las coordenadas polares del plano al espacio tridimensional. 1. sr, ud es una representación polar de la proyección de P en el plano xy. 2. z es la distancia dirigida de sr, ud a P. Para convertir coordenadas rectangulares en coordenadas cilíndricas (o viceversa), hay que usar las siguientes fórmulas, basadas en las coordenadas polares, como se ilustra en la figura 11.66. y Figura 11.66 Cilíndricas a rectangulares: x 5 r cos u, y 5 r sen sin u, z5z Rectangulares a cilíndricas: r 2 5 x 2 1 y 2, y tan u 5 , x z5z Al punto (0, 0, 0) se le llama el polo. Como la representación de un punto en el sistema de coordenadas polares no es única, la representación en el sistema de las coordenadas cilíndricas tampoco es única. (x, y, z) = (−2 3, 2, 3) EJEMPLO 1 P z z 4 1 Convertir el punto sr, u, zd 5 4, −4 3 −3 2 r 1 θ x ( (r, θ , z) = 4, 1 2 5π ,3 6 Figura 11.67 ) 2 3 4 y 1 2 !3 5p 5 22!3 54 2 6 2 5p 1 sen y 5 4 sin 54 52 6 2 z 5 3. x 5 4 cos −1 −1 5p , 3 a coordenadas rectangulares. 6 Solución Usando las ecuaciones de conversión de cilíndricas a rectangulares se obtiene −2 1 Conversión de coordenadas cilíndricas a coordenadas rectangulares 12 Por tanto, en coordenadas rectangulares, el punto es sx, y, zd 5 s22!3, 2, 3d, como se muestra en la figura 11.67. Larson-11-07.qxd 3/12/09 17:44 Page 823 SECCIÓN 11.7 z Conversión de coordenadas rectangulares a coordenadas cilíndricas EJEMPLO 2 (x, y, z) = (1, 823 Coordenadas cilíndricas y esféricas 3, 2) 3 Convertir el punto sx, y, zd 5 s1, !3, 2d a coordenadas cilíndricas. r=2 2 Solución 1 r 5 ± !1 1 3 5 ± 2 z=2 1 2 θ= π 3 2 y 3 u 5 arctan s!3 d 1 np 5 tan u 5 !3 3 x Usar las ecuaciones de conversión de rectangulares a cilíndricas. p 1 np 3 z52 (r, θ , z) = 2, π , 2 o −2, 4π , 2 3 3 ( Figura 11.68 ) ( ) Hay dos posibilidades para r y una cantidad infinita de posibilidades para u. Como se muestra en la figura 11.68, dos representaciones adecuadas del punto son 12, p3 , 22 122, 43p , 22. r > 0 y u en el cuadrante I. r < 0 y u en el cuadrante III. Las coordenadas cilíndricas son especialmente adecuadas para representar superficies cilíndricas y superficies de revolución en las que el eje z sea el eje de simetría, como se muestra en la figura 11.69. x2 + y2 = 9 r=3 x 2 + y 2 = 4z r=2 z x 2 + y2 = z 2 r=z x2 + y2 − z2 = 1 r2 = z2 + 1 z z z z y y x x Cilindro y Paraboloide y x x Cono Hiperboloide Figura 11.69 Los planos verticales que contienen el eje z y los planos horizontales también tienen ecuaciones simples de coordenadas cilíndricas, como se muestra en la figura 11.70. z z Plano vertical: θ =c θ =c y y x x Figura 11.70 Plano horizontal: z=c Larson-11-07.qxd 824 3/12/09 17:44 CAPÍTULO 11 Page 824 Vectores y la geometría del espacio Conversión de coordenadas rectangulares a coordenadas cilíndricas EJEMPLO 3 Rectangular: x2 + y2 = 4z2 Cilíndrica: r2 = 4z2 z Hallar una ecuación en coordenadas cilíndricas para la superficie representada por cada ecuación rectangular. 3 a) x 2 1 y 2 5 4z 2 x b) y 2 5 x 4 6 4 6 y Solución a) Según la sección anterior, se sabe que la gráfica de x 2 1 y 2 5 4z 2 es un cono “de dos hojas” con su eje a lo largo del eje z, como se muestra en la figura 11.71. Si se sustituye x 2 1 y 2 por r 2, la ecuación en coordenadas cilíndricas es Figura 11.71 x 2 1 y 2 5 4z 2 Ecuación rectangular. r 2 5 4z 2. Ecuación cilíndrica. b) La gráfica de la superficie y 2 5 x es un cilindro parabólico con rectas generatrices paralelas al eje z, como se muestra en la figura 11.72. Sustituyendo y2 por r2 sen2 q y x por r cos q, se obtiene la ecuación siguiente en coordenadas cilíndricas. Rectangular: y2 = x Cilíndrica: r = csc θ cot θ y2 5 x r2 z rs r sen sin22 u 2 r sin2 sen 4 u 5 r cos u 2 cos ud 5 0 sin sen22 u r 5 csc u cot u 2 y Figura 11.72 Dividir cada lado entre r. cos u sen sin22 u r5 Sustituir y por r sen q y x por r cos q. Agrupar términos y factorizar. 2 cos u 5 0 1 x Ecuación rectangular. Despejar r. Ecuación cilíndrica. Hay que observar que esta ecuación comprende un punto en el que r 5 0, por lo cual nada se pierde al dividir cada lado entre el factor r. La conversión de coordenadas rectangulares a coordenadas cilíndricas es más sencilla que la conversión de coordenadas cilíndricas a coordenadas rectangulares, como se muestra en el ejemplo 4. Conversión de coordenadas cilíndricas a coordenadas rectangulares EJEMPLO 4 Cilíndrica: r2 cos 2θ + z2 + 1 = 0 Hallar una ecuación en coordenadas rectangulares de la superficie representada por la ecuación cilíndrica z 3 r 2 cos 2u 1 z 2 1 1 5 0. Solución 3 r 2 cos 2u 1 z 2 1 1 5 0 2 x −1 −2 −3 Rectangular: y2 − x2 − z2 = 1 Figura 11.73 2 3 y s r2 cos 2 u 2 sen sin2 r 2 cos 2 u2 ud 1 z2 r 2 sen sin22 u x2 2 y2 y2 2 x2 1150 Ecuación cilíndrica. Identidad trigonométrica. 1 z2 5 21 1 z2 5 21 Sustituya r cos q por x y r sen q por y. 2 z2 51 Ecuación rectangular. Es un hiperboloide de dos hojas cuyo eje se encuentra a lo largo del eje y, como se muestra en la figura 11.73. Larson-11-07.qxd 3/12/09 17:44 Page 825 SECCIÓN 11.7 Coordenadas cilíndricas y esféricas 825 Coordenadas esféricas En el sistema de coordenadas esféricas, cada punto se representa por una terna ordenada: la primera coordenada es una distancia, la segunda y la tercera coordenadas son ángulos. Este sistema es similar al sistema de latitud-longitud que se usa para identificar puntos en la superficie de la Tierra. Por ejemplo, en la figura 11.74 se muestra el punto en la superficie de la Tierra cuya latitud es 40° Norte (respecto al ecuador) y cuya longitud es 80° Oeste (respecto al meridiano cero). Si se supone que la Tierra es esférica y tiene un radio de 4 000 millas, este punto sería Meridiano cero z y 80° O 40° N (4 000, 280°, 50°). x Radio Ecuador 80° en el sentido de las manecillas del reloj, desde el meridiano cero 50° hacia abajo del Polo Norte Figura 11.74 EL SISTEMA DE COORDENADAS ESFÉRICAS En un sistema de coordenadas esféricas, un punto P en el espacio se representa por medio de una terna ordenada sr, u, fd. 1. r es la distancia entre P y el origen, r ≥ 0. 2. u es el mismo ángulo utilizado en coordenadas cilíndricas para r ≥ 0. 3. f es el ángulo entre el eje z positivo y el segmento de recta OP , 0 ≤ f ≤ p. \ Hay que observar que la primera y tercera coordenadas, r y f, son no negativas. r es la letra minúscula ro, y f es la letra griega minúscula fi. La relación entre coordenadas rectangulares y esféricas se ilustra en la figura 11.75. Para convertir de un sistema al otro, usar lo siguiente. z r = ρ sen φ = x2 + y2 Esféricas a rectangulares: x 5 r sen sin f cos u, z P φ O ρ θ r (ρ, θ , φ ) (x, y, z) y 5 r sen sin f sen sin u, z 5 r cos f Rectangulares a esféricas: y x x f 5 arccos 1 !x 2 2 z 1 y2 1 z2 y Coordenadas esféricas Figura 11.75 y tan u 5 , x r 2 5 x 2 1 y 2 1 z 2, Para cambiar entre los sistemas de coordenadas cilíndricas y esféricas, usar lo siguiente. Esféricas a cilíndricas sr ≥ 0d: r 2 5 r 2 sen sin22 f, u 5 u, z 5 r cos f Cilíndricas a esféricas xr ≥ 0c: r 5 !r 2 1 z 2, u 5 u, f 5 arccos 1 z 2 !r 2 1 z 2 Larson-11-07.qxd 826 3/12/09 17:44 CAPÍTULO 11 Page 826 Vectores y la geometría del espacio El sistema de coordenadas esféricas es útil principalmente para superficies en el espacio que tiene un punto o centro de simetría. Por ejemplo, la figura 11.76 muestra tres superficies con ecuaciones esféricas sencillas. z z z φ=c c y x x Esfera: ρ=c θ=c y y x Semiplano vertical: θ=c Semicono: φ=c (0 < c < π2 ) Figura 11.76 EJEMPLO 5 Conversión de coordenadas rectangulares a coordenadas esféricas Hallar una ecuación en coordenadas esféricas para la superficie representada por cada una de las ecuaciones rectangulares. a) Cono: x 2 1 y 2 5 z 2 b) Esfera: x 2 1 y 2 1 z 2 2 4z 5 0 Solución a) Haciendo las sustituciones apropiadas de x, y y z en la ecuación dada se obtiene lo siguiente. Rectangular: x2 + y2 + z2 − 4z = 0 Esférica: ρ = 4 cos φ z 4 x2 1 y2 5 z2 r 2 sen sin2 f cos 2 u 1 r 2 sen sin2 f sen sin2 u 5 r 2 cos 2 f r 2 sen sin22 f scos 2 u 1 sen sin2 ud 5 r 2 cos 2 f 2 r sen sin2 f 5 r 2 cos 2 f sen sin2 f 51 cos 2 f tan2 f 5 1 ≥ 0. r ≥ o f 5 3py4. f 5 py4 or La ecuación f 5 py4 representa el semicono superior, y la ecuación f 5 3py4 representa el semicono inferior. b) Como r 2 5 x 2 1 y 2 1 z 2 y z 5 r cos f, la ecuación dada tiene la forma esférica siguiente. rs r 2 4 cos fd 5 0 r 2 2 4r cos f 5 0 Descartando por el momento la posibilidad de que r 5 0, se obtiene la ecuación esférica −2 1 2 x Figura 11.77 1 r 2 4 cos f 5 0 2 y o r 5 4 cos f. Hay que observar que el conjunto solución de esta ecuación comprende un punto en el cual r 5 0, de manera que no se pierde nada al eliminar el factor r. La esfera representada por la ecuación r 5 4 cos f se muestra en la figura 11.77. 1053714_1107.qxp 10/27/08 10:41 AM Page 827 1053714_1107.qxp 10/27/08 Page 827 1053714_1107.qxp 10/27/08 10:41 AM Page Page827 827 Larson-11-07.qxd 3/12/09 10:41 17:44AM 1053714_1107.qxp 10/27/08 1053714_1107.qxp 10:41 AM 1053714_1107.qxp 10/27/08 10:41 10:41 AM AM Page Page 827 827 1053714_1107.qxp 10/27/08 10/27/08 10:41 AM Page 827 1053714_1107.qxp 10/27/08 10:41 AM Page 827 1053714_1107.qxp 10/27/08 10:41 AM Page 827 1053714_1107.qxp 10/27/08 10:41 AM Page 827 SECCIÓN Coordenadas cilíndricas y esféricas 11.7 11.7 Cylindrical and Spherical Coordinates 11.7 Cylindrical and Spherical Coordinates 11.7 Cylindrical Cylindricaland andSpherical SphericalCoordinates Coordinates 11.7 11.7 Cylindrical and Spherical Coordinates 11.7 Cylindrical and Spherical Coordinates 11.7 11.7 Cylindrical and Spherical Coordinates 11.7 Cylindrical Cylindrical and and Spherical Spherical Coordinates Coordinates 827 827 827 827 827 827 827 827 827 827 Exercises www.CalcChat.com for worked-out solutions to odd-numbered exercises. 11.7 Ejercicios SeeSeeSee 11.7 Exercises www.CalcChat.com for odd-numbered 11.7 Exercises See www.CalcChat.com for worked-out worked-out solutions solutions to to odd-numbered exercises. exercises. www.CalcChat.com for odd-numbered Exercises See www.CalcChat.com worked-out solutions to exercises. Exercises See www.CalcChat.com forworked-out worked-outsolutions solutionsto odd-numberedexercises. exercises. 11.7 11.7 See www.CalcChat.com for for worked-out solutions totoodd-numbered odd-numbered exercises. Exercises See www.CalcChat.com for worked-out solutions to odd-numbered exercises. 11.7 See www.CalcChat.com for worked-out solutions to odd-numbered exercises. Exercises See www.CalcChat.com for worked-out solutions to exercises. find an equation in rectangular coordinates In11.7 Exercises 1–6,1 convert the point cylindrical coordinates Inodd-numbered Exercises 49–56, En los ejercicios 49 a 56, encontrar una ecuación en coordenadas En los ejercicios a 6, convertir las from coordenadas cilíndricas del In Exercises 1–6, convert the point from cylindrical coordinates In Exercises 49–56, find an equation inrectangular rectangular coordinates In Exercises 1–6, convert the point fromcylindrical cylindrical coordinates In Exercises 49–56, find an equation rectangular coordinates In Exercises 1–6, convert the point from coordinates In Exercises 49–56, find an equation coordinates to rectangular coordinates. for the equation in spherical coordinates, and sketch itsy rectangulares de given la ecuación dada in en coordenadas esféricas punto en coordenadas rectangulares. In Exercises 1–6, convert the point from cylindrical coordinates In Exercises 49–56, find an equation in rectangular coordinates In Exercises 1–6, convert the point from cylindrical coordinates In Exercises 49–56, find an equation inin rectangular coordinates In Exercises 1–6, convert the point from cylindrical coordinates In Exercises 49–56, find an equation in rectangular coordinates to rectangular coordinates. for the equation given in spherical coordinates, and sketch its to rectangular coordinates. for the equation given in spherical coordinates, and sketchits its to rectangular coordinates. for the equation given in spherical coordinates, and sketch In Exercises 1–6, convert the point from cylindrical coordinates In Exercises 49–56, find an equation in rectangular coordinates graph. In Exercises 1–6, convert the point from cylindrical coordinates In Exercises 49–56, find an equation in rectangular coordinates dibujar su gráfica. to rectangular coordinates. for the equation given in spherical coordinates, and sketch its to rectangular coordinates. for the equation given in spherical coordinates, and sketch its In Exercises 1–6, convert the point from cylindrical coordinates In Exercises 49–56, find an equation in rectangular coordinates to rectangular coordinates. for the equation given in spherical coordinates, and sketch its graph. 7, 0, 5 2, , 4 1. 2. 1. rectangular 7, 0, 5 coordinates. 2. 2, , 4 graph. graph. to for the equation given in spherical coordinates, and sketch its to rectangular coordinates. for the equation given in spherical coordinates, and sketch its 0,5 55 coordinates. 2, graph. graph. to rectangular for the equation given in spherical coordinates, and sketch its 7, 2, , , ,, 44444 1. 2. 2, graph. 7,7,7, 0, 1.1.1. 2.2.2. 3 0, 0,0, 2, 4, 6, ,,4, 4, graph. 3, 3,7, 15551 6,2, 242 3.1. 4.2. 7, 4, 0, 2, 1.3. 2.4. graph. 33 5 49. 50. graph. 3, 4, 1 6, 4, 2 3. 4. 3 7, 5515 1 2, 4244 2 1. 2. 6, ,,,4, 3. 3,3,3, 4. 6, 49. 50. 7, 0, 0, 2, 1. 2. 4, 3. 4. 3334 49. 50. 55555 2, 1. 2. 49. 50. 4, 1131 3 2223, 4,4, 6, 4,4, 3. 4. 6, 0.5, 5.4,3, 6. 6, 7 7,7 0, 6, 0.5, 4 44, 3, 88 5.3. 6.4. 49. 50. 3,4, 4, 6, 4, 49. 50. 3. 4. 33344444 5 49. 50. 4, 7 6, 3 0.5, 4 3, 8 5. 6. 3, 4, 1 6, 4, 2 3. 4. 4, 7 6, 3 0.5, 4 3, 8 5. 6. 3, 4, 1 6, 4, 2 3. 4. 6, 5. 6. 555 49. 50. 4 49. 50. 3, 23, 3. 4. 4, 6, 0.5, 5. 6. 4,7777 4, 6,13333 0.5,44444, 3, 3,8888 5. 4, 6. 6,0.5, 51. 52. 49. 50. 4, 6, 0.5, 3, 5. 6. 4442 In Exercises 7–12, convert the point from0.5, rectangular coordinates 51. 52. 6 4, 7 6, 3 4 3, 8 5. 6. 4, 7 6, 3 0.5, 4 3, 8 5. 6. 51. 52. 51. 52. En los aconvert 12, convertir las coordenadas In Exercises 7–12, the point from rectangular coordinates 4,ejercicios 7 6, 3 7convert 0.5, 4 3, rectangulares 8coordinates 5.Exercises 6. 51. 52. 51. 52. In Exercises 7–12, convert the point from rectangular coordinates In 7–12, the point from rectangular 66666 22222 51. 52. to cylindrical coordinates. In Exercises convert the point from rectangular coordinates In Exercises 7–12, convert the point from rectangular coordinates 53. 54. In Exercises 7–12, convert the point from rectangular coordinates 51. 52. 644 cos 22 sec del punto en 7–12, coordenadas cilíndricas. to cylindrical coordinates. 51. 52. to cylindrical coordinates. to cylindrical coordinates. cos sec 53. 54. 51. 52. In 7–12, convert the point from rectangular coordinates In Exercises 7–12, convert the point from rectangular coordinates cos sec 53. 54. 4464664cos 22222222sec 53. 54. to cylindrical coordinates. toExercises cylindrical coordinates. In Exercises 7–12, convert the point from rectangular coordinates to cylindrical coordinates. cos 53. 54. cos sec 53. 54. csc 4sec csc sec 55. 56. 0, 5, 1 2 2, 2 2, 4 7. 8. 4 cos 2 sec 53. 54. to cylindrical coordinates. 7. 0, 5, 1 8. 2 2, 2 2, 4 to cylindrical coordinates. csc 4 csc sec 55. 56. 0, 5, 1 2 2, 2 2, 4 7. 8. 4 cos 2 sec 53. 54. csc 4 csc sec sec 55. 56. to cylindrical 44csc cos sec 53. 54. 0, 7. csc 44224csc 55. 56. 7. 8. 0, 5,5,5, 1111 coordinates. 2 2 2,2,2, 44 cos sec 53. 54. csc csc sec 55. 56. csc sec 55. 56. 0, 2, 7. 8. 0, 2,2, 7. 8.8. 22223,2 2, 2,5, 4 3,77222 2, 9. 2, 10. csc 4cylindrical csc sec 55. 56. 0, 5,2, 12, 2, 2, 444 7. 8. 9. 10. 4 3, 3, In Exercises 57–64, convert the point from coordinates 2, 2, 4 3, 3, 7 9. 10. csc 444cylindrical csc 55. 56. 0, 1112, 4 4 2223,2, 7. 8. csc csc sec 55. 56. 2,5, 10. 0, 5, 2, 2, 7. 8. 9. 10. 3, 7772272 2, En los ejercicios 57 a 64, the convertir las coordenadas cilíndricas In Exercises 57–64, convert the point from coordinates csc57–64, csc sec seccoordinates 55. 56.from 0, 5,2, 2, 2,444 7. 8. 3, 2, 2, 3, 3, 9. 10. 2, 2,3, 4444 3, 3,3, 9.9. 2, 10. In Exercises 57–64, convert the point from cylindrical coordinates 1, 2 2, 6 11. 12. In Exercises convert point cylindrical 2, 2, 3, 3, 7 9. 10. to spherical coordinates. 1, 3,3,4 44 23,2 3,3, 2,2,6 6 11. 12. In Exercises 57–64, convert the In Exercises 57–64, convertesféricas. thepoint pointfrom fromcylindrical cylindricalcoordinates coordinates 1, 3, 11. 12. In Exercises 57–64, convert the point from cylindrical coordinates 2, 2, 7 9. 10. del punto en coordenadas to spherical coordinates. 1, 3, 2 3, 2, 6 11. 12. 2, 2, 4 3, 3, 7 9. 10. 11. 12. 1, 3, 4 2 3, 2, 6 to spherical coordinates. to spherical coordinates. 2, 2, 9. 1, 10. 11. 12. 1, 3, 3,444 4 2 3, 3,3, 72, 2,666 11. 12. 223, In convert from In Exercises 57–64, convert the point from cylindrical cylindrical coordinates coordinates to spherical coordinates. toExercises spherical57–64, coordinates. 1, 3, 3, 2, 11. 12. In Exercises 57–64, convertthe thepoint point to spherical coordinates. InEExercises –20, equation cylindrical 4, 4,coordinates. 0 3, cylindrical 4, 0 coordinates 57. 58.from 1, 4441313 3, 12. 1, 3, 3, 2, 11. 12. to spherical I11. i 3, 20 fifind d an i i222in li d2, i666 l coordinates di to spherical coordinates. In Exercises 13 –20, find an equation in cylindrical coordinates 1, 3, 3, 2, 11. 12. 4, 4, 0 3, 4, 0 57. 58. to57. spherical InExercises Exercises 13 –20, find anequation equation incylindrical cylindrical coordinates 4,0coordinates. 0 58. 3,3,3, In 13 –20, find coordinates En los 13 afind 20, hallar una in ecuación en coordenadas 4,4,4, 4, 4,4,4,0000 57. 58. for theejercicios equation given inan rectangular coordinates. In Exercises 13 –20, find an equation in cylindrical coordinates In Exercises 13 –20, an equation in cylindrical coordinates 4, 57. 58. 4, 57. 58. 2,0004 2 4, 3, 0 2 59. 4, 60. 3, In Exercises 13 –20, find an equation in cylindrical coordinates 4,4, 4, 3,2, 4, 57. 58. for the equation given in rectangular coordinates. for theequation equation given in rectangular coordinates. for the given in rectangular coordinates. 4, 2, 44 2, 22 3,4, 3, 59. 60. cilíndricas de13 la–20, ecuación dada en coordenadas rectangulares. In Exercises find an equation in cylindrical coordinates 4, 0 3, 57. 58. In Exercises 13 –20, find an equation in cylindrical coordinates 4, 2, 2, 3,00022222 59. 60. 4, 4, 0 3, 4, 57. 58. 4, 2, 4 2, 2 59. 60. for the equation given in rectangular coordinates. for the equation given in rectangular coordinates. In Exercises 13 –20, find an equation in cylindrical coordinates 4, 4, 0 3, 57. 58. for the equation given in rectangular coordinates. 4, 2, 4 2, 2 3, 59. 60. 2, 4 2, 2 3, 59. 60. 3, 42 61. 4,4, 2, 46, 6 62. 2, 24, 3,4, z equation 4 x 9 13.the 14. coordinates. 59. 60. for given in rectangular for the equation given in rectangular coordinates. 4, 6, 6 4, 3, 61. 62. z 4 x 9 13. 14. 4, 2, 4 2, 2 3, 59. 60. 4, 2, 6,6666 4, 3, 3,42244 61. 4, 62. 2, for given in rectangular 4, 46, 24, 59. 60. z2 equation x 99992 13.zthe 14.xxxcoordinates. 6, 4, 3, 61. 62. 13. 14. 4444 2 2 2 4, 2, 4 2, 2 3, 59. 60. 6, 4, 3, 61. 62. 3, 61. 62. z 13. 14. z 13. 14. 12, , 5 4, 2, 34442 63. 64. x y z 17 z x y 11 15. 16. 4, 6, 6 4, 3, 61. 62. z x 9 13. 14. 22 4 22 22 22 22 12, 55 66 4,4, 2,2, 63. 64. 17 11 15. 16. 4, 3,3,33444 61. 62. 13. 14. 12, ,,,55,,56, 63. 12, 64. 4, 4, 6, 61. 62. 17 11 15.xzz2xx 44y 2yy z 2zz 17 16.zxx zz x992xx y 2yy 11 63. 64. 13. 14. 15. 16. 4, 6 4, 2, 61. 62. 13. 14. 12, 4, 333 63. 64. 12, 4,4,4, 2,2,33, 63. 64. 15. 16. 17 11 15. 16. 17. xxzxy222 4yxyy22222 zzz222 17 18. zzxzx 22 xxx9222y 22 yyy2228x 11 12, , 5 6,65–72, 4, 2, 63. 64. 17 15. 16. 22 222 22 222y 2 22 8x 11 In Exercises convert the point from spherical coordinates 2 y x x 17. 18. 2 2 12, , 5 4, 2, 3 63. 64. x z z x y 11 15. 16. 12, , 5 4, 2, 33 63. 64. y x x y 8x 17. 18. x y z 17 z x y 11 15. 16. 22 xy 2 22 17 2 2 y x y 8x 17. 18. 2 2 2 2 2 2 In Exercises 65–72, the point from coordinates 12,ejercicios , 565–72, 4, 2,spherical 63. 64.las 15. 16. 17. 18. 8x 17. 18. InExercises Exercises 65–72, convert thepoint point from spherical coordinates z 22 113z 0 19. yyxyy 2 xxx2y10 zz 2 17 20. xxzxx2 22 xyyyy2 22 y8x In the from spherical coordinates En los 65convert aconvert 72, convertir coordenadas esféricas del 8x 17. 18. to cylindrical coordinates. In Exercises 65–72, convert the point from spherical coordinates In Exercises 65–72, convert the point from spherical coordinates 2 2 2 2 10 zz2 3z 19. 20. 2zz 2 Into Exercises 65–72, convert the point from spherical coordinates 17. 18. cylindrical coordinates. 3z 00000 19.yyyy222yy2 2 xxx10 20.xxxx2222xx2 2 yyyy2222yy2 2 z8x 8x 17. 18. 210 z222 3z 19. 20. 2 2 to cylindrical coordinates. to cylindrical coordinates. punto en coordenadas cilíndricas. 8x 17. 18. 2 2 10 z z 3z 19. 20. 10 z z 3z 19. 20. In Exercises 65–72, convert In Exercises 65–72, convert the the point point from from spherical spherical coordinates coordinates to coordinates. to cylindrical cylindrical coordinates. y22 10 21–28, z y z 3z 0 19. 20. xin In Exercises to cylindrical coordinates. In Exercises find an equation rectangular coordinates 10, 6,65–72, 2 convert the point 4, spherical 18, 2 coordinates 65. 66. from xxx22in yExercises zzz222 yyy222 zzz222 3z 000 19. 20. yy2 10 10 3z 19. 20. 2 rectangular to cylindrical coordinates. to cylindrical coordinates. In 21–28, find an equation coordinates 10 3z 19. 20. 10, 6, 2 4, 18, 2 65. 66. to cylindrical coordinates. In Exercises 21–28, find an equation in rectangular coordinates 10, 6, 2 4, 18, 2 65. 66. In Exercises 21–28, find an equation rectangular coordinates 10, 6,6, 222 4,4, 18, 2 65. 66. for theejercicios equation given in cylindrical coordinates, sketch its In Exercises 21–28, find an equation in rectangular coordinates In Exercises 21–28, find an equation in rectangular coordinates 18, 65. 66. 10, 18, 65. 66. En los 21 a 28, hallar unain ecuación en and coordenadas 36, ,6, 3, 2223 2 67. 10, 68. 4, In Exercises 21–28, find an equation in rectangular coordinates 10, 6, 4,18, 18, 65. 66. for the equation given in cylindrical coordinates, and sketch its for theequation equation given in cylindrical coordinates, and sketchits its for the given in cylindrical coordinates, and sketch 36, ,, 2 22222 18, 3, 67. 68. In Exercises 21–28, find an equation in rectangular coordinates 10, 6, 4, 18, 23 65. 66. graph. In Exercises 21–28, find an equation in rectangular coordinates 36, 18, 3, 67. 68. 10, 6, 4, 18, 65. 66. 36, , 18, 3, 67. 68. for the equation given in cylindrical coordinates, and sketch its for the equation given in cylindrical coordinates, and sketch its rectangulares de la ecuación dada en coordenadas cilíndricas y In Exercises 21–28, find equationcoordinates, in rectangular 10, 4, 65. 66. for the equation given in an cylindrical andcoordinates sketch its 3, 67. 68. 36, 18, 3, 6,3332233 67. 68. graph. 6, ,,, 6,6,222 2 3 5, 518, 69. 36, 70. 18, 36, 18, 3, 67. 68. graph. graph. for the equation given in cylindrical coordinates, and sketch its for the equation given coordinates, and 6, 5, 69. 70. graph. graph. dibujar su gráfica. 36, 18, 222 3 33 67. 68. 6, ,, 6,6,6, 6, 5, 5 553, 6,33 69. 6, 70. 5, for given in in cylindrical cylindrical and sketch sketch its its 36, 18, 3,6,6,6, 67. 68. 69. 70. graph. r equation 3 z 2 21. the 22. coordinates, 36, 18, 67. 68. 3363 69. 70. 6, 5, 69. 70. 8, 7 , 6, 7, 5554,3,6, 3 34 71. 6, 72. 5, graph. 6, 6, 5, 6, 69. 70. graph. r 3 z 2 21. 22. graph. 8, 7 6, 6 7, 4, 3 71. 72. r 3 z 2 21. 22. r 3 z 21 21. 22. 6, 6, 5, 55 4,36, 69. 70. 6, 6663336 3 44444 71. 8, 72. 7, 6, 6, 5, 69. 70. 71. 72. 21. 22. 21. 22. 23. rrr 333 6 24. zzzr 222211z 6, 6, 5, 6, 69. 70. 8, 6, 7, 4, 71. 72. 8,8,77777 6, 6, 7,7, 54, 4,3336, 71. 72. 21. 22. 8, 6, 6 7, 4, 4 71. 72. 1 r 6 z 23. 24. 21. 22. CAS 71. In Exercises 736–88, use a computer algebra graphing 23.rr 33 6 6 24.rzz r 2121z2 z 21. 22. 23. 24. 8, 7, 3system 444 or 72. 8, 6, 6–88, 7, 4, 3system 71. 72. 21. 22. 23. 24. 23. 24. 25. rr 22 3 z 26626 5 26. rrzrz 21212122zzrz222 cos22 CAS In Exercises use acomputer computer algebra or graphing 8,777 6, 6,7373 6–88, 7, 4, 4,system 3system 71. 72.algebra 23. 24. CAS In Exercises 73 use a computer algebra or graphing CAS In Exercises –88, use a or graphing utility to convert the point from one system to another among 2 2 2 cos 2 z r r z 5 25. 26. 2 2 2 2 CAS CAS In Exercises 73 –88, use a computer algebra system or graphing In Exercises 73 –88, use a computer algebra system or graphing 1 r 6 z 23. 24. En los ejercicios 73 a 88, usar un sistema algebraico por compuz r r z 5 cos 25. 26. r 6 z 23. 24. zzrz r2r2r22z2cos rrr222 zzz222 6 555 25. 26. 2 2 CAS In Exercises 73 –88, use a computer algebra system or graphing utility to convert the point from one system to another among 23. 24. cos 2 25. 26. cos 25. 26. utility to convert the point from one system to another among cos 27. rr z2 sen 5 28. zr r22 cos utility to convert the point from one system to another among 25. 26. CAS In Exercises 73 –88, use a computer algebra system or graphing the rectangular, cylindrical, and spherical coordinate systems. CAS In Exercises 73 –88, use a computer algebra system or graphing utility to convert the point from one system to another among utility to convert the point from one system to another among 22r 2 2 2 tadora o una herramienta de graficación para convertir las coor2 2 2 2 sen r 2 cos 27. 28. CAS In Exercises 73 –88, use a computer algebra system or graphing utility to convert the point from one system to another among z r z 5 cos 25. 26. the rectangular, cylindrical, and spherical coordinate systems. r 2 sen r 2 cos 27. 28. z r r z 5 cos 25. 26. 2 2 2 2 r 2 sen r 2 cos 27. 28. the rectangular, cylindrical, and spherical coordinate systems. the rectangular, cylindrical, and spherical coordinate systems. z r r z 5 cos 25. 26. r 2 sen 2 cos r 27. 28. 2 sen r 2 cos 27. 28. utility to convert the point from one system to another among utility to convert the point from one system to another among the cylindrical, and coordinate systems. the rectangular, rectangular, cylindrical, andspherical spherical coordinate systems. r 2 sen r 2 cos 27. 28. denadas del punto de un sistema a otro, entre los sistemas de utility to convert the point from one system to another among the rectangular, cylindrical, and spherical coordinate systems. In Exercises 29–34, convert the point from coordinates Rectangulares Cilíndricas Esféricas rrr 222sen rrr 22rectangular cos 27. 28. sen cos 27. 28. the rectangular, cylindrical, and spherical coordinate systems. the rectangular, cylindrical, and spherical coordinate systems. In Exercises 29–34, convert the point from coordinates sen 2rectangular cos 27. 28.from Rectangulares Cilíndricas Esféricas coordenadas rectangulares, cilíndricas y esféricas. the rectangular, cylindrical, and spherical coordinate systems. In Exercises 29–34, convert the point from rectangular coordinates Rectangulares Cilíndricas Esféricas In Exercises 29–34, convert the point rectangular coordinates Rectangulares Cilíndricas Esféricas toExercises spherical29–34, coordinates. In convert In Exercises 29–34, convertthe thepoint pointfrom fromrectangular rectangularcoordinates coordinates Rectangulares Cilíndricas Esféricas Rectangulares Cilíndricas Esféricas In 29–34, convert the point from rectangular coordinates Rectangulares Cilíndricas Esféricas toExercises spherical coordinates. 4, 6, 3 73. Rectangulares En los ejercicios 29 convert a 34, convertir las coordenadas rectangulares spherical coordinates. to coordinates. In Exercises 29–34, the point from rectangular coordinates Cilíndricas Esféricas In Exercises 29–34, convert the point from rectangular coordinates Rectangulares Cilíndricas Esféricas 4, 6, 33 73. to spherical coordinates. totospherical spherical coordinates. 4, 6, 73. In Exercises 29–34, convert the point from rectangular coordinates Rectangulares Cilíndricas Esféricas 4, 6, 3 73. to spherical coordinates. del punto coordenadas esféricas. 4, 0,en 0 coordinates. 4, 0, 0 29. 30. 73. 4, 6,3332, 3 73. 6,6, 74. 4, to spherical 4, 6, 73. to spherical 4, 0, 4, 0, 30. to29. spherical coordinates. 6, 3 74. 4, 0, 4, 0, 29. 30. 4, 4, 0, 00000 coordinates. 0, 00000 29. 30. 4, 6, 3332, 73. 6, 74. 4, 6, 73. 6, 74. 4, 0, 4, 0, 29. 30. 4, 0, 4, 0, 29. 30. 31. 4, 0,2,02 3, 4 32. 2,4,2,0,40 2 4, 73. 2, 74. 6, 6,2, 2,2, 33333 74. 29. 30. 5, 9, 8 75. 6, 6, 2, 74. 2, 2 3, 4 2, 2, 4 2 31. 32. 4, 0, 0 4, 0, 0 29. 30. 5, 9, 75. 2, 2, 31. 4, 2, 32. 2,2,2, 0, 4, 29. 30. 20 2 3,3,3, 4444 2, 40,44002222 31. 32. 2, 333 74. 5, 9, 9, 75. 6, 6, 2, 74. 5, 88888 75. 0, 4, 29. 30. 2, 31. 32. 2, 2, 31. 32. 3,22201, 23, 3 1,440, 2, 12 33. 4,2, 34. 2, 6, 2, 74. 5, 9, 75. 5, 9,0.75, 75. 2, 3, 4 2, 2, 31. 32. 76. 5,10, 9, 8 6 75. 3, 1, 22 34433 1, 2, 121 33. 34. 2, 2 3, 2, 2, 4 2 31. 32. 10, 0.75, 76. 3, 1, 1, 2, 33. 34. 2, 2 3, 2, 2, 4 31. 32. 3, 1, 2 1, 2, 1 33. 34. 5, 9, 888 6 66 75. 10, 9, 0.75, 76. 5, 75. 10, 0.75, 76. 2, 21,2223,3343 2,2, 4 111 2 31. 32. 33. 34. 3,1, 1, 2, 33. 3, 34. 2,1, 5, 9, 75. 10, 0.75, 76. 10, 0.75, 76. 3, 1, 1, 2, 33. 34. 20, 2 3, 4 77. 10, 0.75, 666 76. In Exercises 35– convert the point from spherical coordinates 3, 333 40, 1, 111 33. 34. 20, 3, 4 77. 3, 1, 1, 2, 33. 34. 10, 0.75, 666 76. 20, 77. 10, 0.75, 76. 20, 2 22 3, 77. In Exercises 35– 40, convert the point from coordinates 3,1, 1,22235– 1,2, 2,spherical 33. 34. from 10, 0.75, 76. In Exercises 35– 40, convert the point from spherical coordinates In Exercises 40, convert the point spherical coordinates 20, 3, 77. 20, 3,3,1 44444 77. 7.5,2220.25, 78. toExercises rectangular 20, 3, 77. In 35– 40, In Exercises 35–coordinates. 40,convert convertthe thepoint pointfrom fromspherical sphericalcoordinates coordinates In Exercises 35– 40, convert the point from spherical coordinates 7.5, 0.25, 1 78. to rectangular coordinates. 20, 2 3, 77. 7.5, 0.25, 78. 20, 20.25, 3, 77. rectangular coordinates. 7.5, 78. to coordinates. En los ejercicios 35 aconvert 40, convertir lasfrom coordenadas esféricas del In Exercises 35– 40, spherical coordinates 20, 20.25, 3,11111 444 77. In Exercises 35– 40, the point from spherical coordinates 7.5, 78. 7.5, 0.25, 78. to rectangular coordinates. totorectangular rectangular coordinates. 79. 3, 2, 2 In Exercises 35– 40, convert convertthe thepoint point from spherical coordinates 7.5, 0.25, 78. to rectangular coordinates. 4, 6, 4 12, 3 4, 9 35. 36. 79. 7.5, 78. punto en coordenadas rectangulares. to rectangular coordinates. 3, 2,2,2, 2, 79. 3,3,3, 7.5, 0.25, 78. 22222 79. to rectangular 44 12, 36. 7.5,0.25, 0.25,111 78. to35. rectangular coordinates. 79. 79. 4, 6,6,6, 6, 4coordinates. 12, 4, 99999 35. 36. 12, 4,4,4, 3 33 4,4,4, 35. 36. 3 80. 3, 3,33 2, 2, 233 2, 79. 35. 36. 12, 35. 36. 12, 6, 4,4440 9, 333 4,4, 37. 4, 38. 12, 2, 3 2, 80. 4, 6, 12, 4, 9 35. 36. 2, 79. 2, 80. 3, 2, 79. 3223 2,2,2, 3333 33, 80. 12, 4, 9, 37. 38. 79. 4, 440 00 12, 35. 36. 80. 353 2, 80. 12, 6, 4, 9,33 4,4,4, 4,4, 37. 12, 38. 9, 4, 6, 4, 12, 4, 35. 36. 37. 38. 2,2,2,433323,2, 81. 333, 2, 33322 80. 4, 12, 4,2 999 35. 36. 37. 38. 12, 9, 37. 38. 5, 6, 4, 4, 34,40004 6, 3,4, 39. 12, 40. 9, 552,2, 2, 81. 12, 4, 9, 4, 37. 38. 334433,3, 2, 3 80. 2, 3, 81. 2, 3 3323 2 3 2, 80. 5 4 81. 5, 4, 3 4 6, , 2 39. 40. 3 2, 80. 12, 4, 0 9, 4, 37. 38. 5 2, 4 3, 81. 5 2, 4 3, 81. 5, 4, 3 4 6, , 2 39. 40. 12, 4, 0 9, 4, 37. 38. 39. 40. 82. 50,2, 45,3,4 2,333 2232 81. 12, 9, 37. 38. 5, 4, 6, 39. 40. 5, 4, 4,33334, 40444 6, ,,,, 4, 2222 39. 5, 40. 6, 0, 5, 4 82. 5, 4, 6, 39. 40. 5550,2, 4445, 3,3,4 333 222 81. 82. 0, 81. 82. In Exercises 41– find an equation in,, spherical coordinates 2,5, 81. 5, 444 48, 222 39. 40. 5, 82. 0, 2, 5,4443, 4 82. 5, 4, 6, 39. 40. 5, 3 4, 5 83. 0, 0, 5, 82. In Exercises 41– 48, find an equation in coordinates 5, 4, 4,33341– 6, , spherical 39. 40. 6, InExercises Exercises 41– 48,find find anequation equation inspherical spherical coordinates In 48, in coordinates 5, 4, 55 83. 0, 5, 4 82. for the equation given inan rectangular coordinates. 5, 83. 0, 5, 44 82. 5, 3 33 4, 83. In Exercises 41– 48, find an equation in spherical coordinates In Exercises 41– 48, find an equation in spherical coordinates 0, 5, 82. In Exercises 41– 48, find an equation in spherical coordinates 5, 4, 555 3 83. 5, 4,4, 56, 83. for the equation given in rectangular coordinates. 11 84. 5, 3332, 4, 83. for theequation equation given inrectangular rectangular coordinates. for the given in coordinates. In Exercises 41– 48, find an equation in spherical coordinates In Exercises 41– 48, find an equation in spherical coordinates 2, 11 6,3 33 84. for the equation given in rectangular coordinates. for the equation given in rectangular coordinates. 5, 3 4, 5 83. En los ejercicios 41 a 48, hallar una ecuación en coordenadas 2, 11 84. In Exercises 41– 48, find an equation in spherical coordinates 5, 3 4, 83. 2, 11 6, 84. for the equation given in rectangular coordinates. y equation 2 z 6 41.the 42. coordinates. 5,2, 33.5, 56333 83. 11 84. 2, 114, 6,56, 84. 2.5,6, 85. for given in rectangular 2, 11 6, 84. for the equation given in rectangular coordinates. y 2 z 6 41. 42. esféricas de la ecuación dada en coordenadas rectangulares. for given in rectangular 3.5, 2.5, 85. y equation z 66 41.ythe 42.z coordinates. 22 41. 42. 2, 11 6, 84. 3.5, 2.5, 85. 2, 11 6, 84. 3.5, 2.5, 66663633 85. 41. 42. 41. 42. 43. yyyx 22 222 y 22 z 22 49 44. zzzx 22 666 y 22 3z 22 0 2, 11 6, 84. 3.5, 2.5, 85. 3.5, 2.5, 85. 41. 42. 8.25, 1.3, 6 4 86. 3.5, 2.5, 85. 49 3z 43. 44. 2 2 41. 42. 8.25, 1.3, 86. 49 43.xyy2xx 2 22y 2yy 2 z 222zz2 2 49 44.xzz2xx 2 66yy222yy2 2 3z 41. 42. 00000 43. 44. 2 3.5, 2.5, 85. 8.25, 1.3,66644444 86. 3.5, 2.5, 85. 8.25, 1.3, 86. 41. 42. 22 49 3z 43. 44. 49 3z3z 43. 44. 45. xxyxx22222 2yyyy22222 zzz16 46. xxzxx222 6y13 3.5, 2.5, 85. 8.25, 1.3, 86. 8.25, 1.3, 86. 49 y 3z 0 43. 44. 3, 3 4, 3 87. 8.25, 1.3, 4 86. 22 22 2216 22 22 22 2 2 x y x 13 45. 46. 2 2 x x y z 49 y 3z 0 43. 44. 3, 4, 3 33 87. 16 49 45.x x2 y y2 16 46.x x2 13 zz16 yy13 3z22 00 43. 44. 2 2 45. 46. 8.25, 1.3, 444 86. 3, 87. 8.25, 1.3, 86. 3, 33333 4, 87. 43. 44. 45. 46. 13 45. 46. 2z22 49 y 22 3z z 2 9z 0 47. xxxx22 22 yyyy22 22 16 48. xxxx 22 13 8.25, 1.3, 86. 3, 87. 3, 4,4, 87. 16 13 45. 46. 6, 333 88. 3,8, 3 4, 4, 87. 22 2 132y 2 xx2 2 yy2222yy2 2 2z 2z 9z 0 47. 48. 2 2 2 2x 2zz 2 16 45. 46. 8, 6, 3 88. x 2z y 9z 0 47. 48. x 16 x 13 45. 46. x x y z 9z 0 47. 48. 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 3, 3 4, 87. 8, 88. 3, 3 4, 87. 8, 6, 88. x y 16 x 13 45. 46. x 2 2 22 2 2 2 x y 2z y z 9z 0 47. 48. 2z y z 9z 0 47. 48. 3, 87. 8, 6, 88. 8, 3 4, 6,6, 33 88. 47. x22 y22 2z22 48. x22 y22 z22 9z 0 8, 6, 88. x x y 2z y z 9z 0 47. 48. 47. 48. 8, 6, 88. 8, 6, 88. 2z2 9z 00 47. xx 2 yy 2 2z 48. xx 2 yy 2 zz 2 9z 8, 6, 88. 1053714_1107.qxp Larson-11-07.qxd 828 828 828 10/27/08 10:41 AM Page 828 3/12/09 17:44 Page 828 Chapter 11 1111 Vectors Vectors and ythe the Geometrydel of espacio Space CAPÍTULO Vectores la geometría Chapter and Geometry of Space In los Exercises 89–94, match the la equation (written in términos terms of of In Exercises 89–94, match the equation (written in terms En ejercicios 89 a 94, asociar ecuación (dada en cylindrical or spherical coordinates) with its graph. [The graphs cylindrical or spherical coordinates) with [The graphs de coordenadas cilíndricas o esféricas) conitssugraph. gráfica. [Los gráare labeled labeled (a),a), (b),b),(c), (c), (d), (e),y and and (f ).] ).] are (a), (b), (e), ficos se marcan c),(d), d), e) f).] (f zz (a) (a) a) − 33 − 2 − −2 yy 11 22 33 −3 −2 3 22 y 23 1 2 3 xx 3 x zz (c) (c) c) 5 5 zz (b) (b) b) π π π 44 3 3 3 4 z 2 55 y 5 yy 22 44 4 yy y zz 5 55 103. 103. 105. 105. 44 4 x x x (d) (d) d) z 55 99. 99. 101. 101. z −4 −4 −4 5 z 55 55 yy 55 y 5 x x (e) (e) e) 2 − 22 − −2 1 z 22 zz 22 2x x x π π π 44 4 2 22 y z 33 yy 5 55 89. rr 5 89. 89. r 5 5 5 55 91. rr 5 91. 91. r 5 5 5 zz 93. rr 22 5 93. 93. r 2 5 z −2 −2 −2 22 2xx x 11 1 22 2 yy y p 5pp 90. uu 5 90. 90. u 5 44 4 p f5 5pp 92. f 92. 92. f 5 44 4 5 44 sec sec f f 94. rr 5 94. 94. r 5 4 sec f WR R II TT II N NG G A AB BO OU U TT C CO ON NC C EE P P TT S S W 95. Give Give the the equations equations for for the the coordinate coordinate conversion conversion from from 95. Desarrollo conceptos rectangular de to cylindrical cylindrical coordinates and and vice vice versa. versa. rectangular to coordinates 5rec96.Dar Explain why in in spherical spherical coordinates the graph of of uu 5 is 95. las ecuaciones para lacoordinates conversión the de coordenadas cc is 96. Explain why graph a half-plane and not an entire plane. tangulares a coordenadas cilíndricas a half-plane and not an entire plane.y viceversa. 97. Give the equations for the coordinate conversion from 96. Explicar por qué en las coordenadas esféricas la gráfica de 97. Give the equations for the coordinate conversion from rectangular to spherical spherical coordinates and vice vice versa. versa. q rectangular = c es un semiplano y nocoordinates un plano entero. to and 97. Dar las ecuaciones para la conversión de coordenadas rectangulares a coordenadas esféricas y viceversa. CA AP PS S TT O ON N EE C 98. (a) (a) For For constants constants a, and c, describe the the graphs graphs of of the the a, b, b, and c, describe 98. and zz 5 in cylindrical cylindrical 5 b, b, and 5 cc in uu 5 coordinates. coordinates. 98. a) Dadas las constantes a, b y c, describir las gráficas de las ecua(b) For For constants a, and c, describe the the graphs graphs of of the the a, b, and (b) ciones rconstants y z 5 cc,endescribe coordenadas cilíndricas. 5 a, u 5 b,b, equations rr 5 and f in spherical spherical 5 a, a, uu 5 5 b, b, and f5 5 cc in equations b) Dadas las constantes a, b y c, describir las gráficas de las coordinates. coordinates. ecuaciones r 5 a, u 5 b, y f 5 c en coordenadas esféricas. equations rr 5 5 a, a, Para discusión equations 2 1 y2 2 5 4y xx2 1 y 5 4y 2 2 yy 22 5 5 99 xx 2 2 107. 107. 108. 108. # uu 00 # 2p py2 y2 2 109. 109. 110. 110. 00 00 # # # # 100. 100. 102. 102. 104. 104. 106. 106. 2 1 y2 2 5 z2 2 y dd 5 z 44ssxx2 1 2 2 1 yy 2 5 5 zz xx 2 1 2 1 y2 2 5 36 xx2 1 y 5 36 yy 5 5 44 uu uu py2, y2, 00 # 2, 00 # #p # rr # # 2, # zz # # 44 # py2, y2, 00 # 3, 00 # cos uu # uu # #p # rr # # 3, # zz # # rr cos # 2 p , 0 r a, r z a # # # # # # 2p, 0 # r # a, r # z # a p,, 22 # 4, zz 22 # 2r 22 1 1 6r 6r 2 2 88 # 22p # rr # # 4, # 2r # En ejercicios 111 a 114, dibujar sólidothat que tiene In los Exercises 111–114, sketch theel solid solid that has la thedescripgiven In Exercises 111–114, sketch the has the given description incoordenadas spherical coordinates. coordinates. ción dada enin esféricas. description spherical # # # # # # 0 114. # 114. 0 # 3 11 2 1 y2 2 1 z2 2 5 25 xx2 1 y 1 z 5 25 2 2 xx 2 1 1 yy 2 1 1 zz 22 2 2 2z 2z 5 5 00 En ejercicios 107 a 110, dibujar sólido that que tiene In los Exercises 107–110, sketch theel solid solid that has la thedescripgiven In Exercises 107–110, sketch the has the given ción dada en coordenadas cilíndricas. description in cylindrical coordinates. description in cylindrical coordinates. 111. 111. 112. 112. 113. 113. zz (f )) (f f) In Exercises Exercises 99–106, convert the rectangular rectangular equation to an ana In 99–106, the equation to En los ejercicios 99 a convert 106, convertir la ecuación rectangular equation in (a) cylindrical coordinates and (b) spherical equation in a) (a)encylindrical spherical coordenadascoordinates cilíndricas yand b) en(b) coordenadas una ecuación coordinates. coordinates. esféricas. 00 00 00 uu uu uu # # # # # # u # u # p,, 00 # f # py6, y6, 00 # sec f f #f #p # rr # # aa sec 22p 2 p , p y4 f p y2, 0 r 1 #f # # py2, 0 # #r # #1 2p, py4 # 0 p y2, 0 f p y2, r # # # # py2, 0 # f # py2, 0 # r # 22 p,, 00 # f# py2, y2, 11 # #f #p # rr # # 33 p Think About En It los Inejercicios Exercises115 115–120, find inequalities inequalities that Para pensar a 120, hallar las desigualdades Think About It In Exercises 115–120, find that describe the solid, and state the coordinate system used. que describen sólido, sistema desystem coordenadas describe the al solid, andy especificar state the el coordinate used. Position the the solid on on the coordinate coordinate system such that that en the utilizado. Posicionar al sólido en el sistema de coordenadas el Position solid the system such the inequalities are as simple as possible. que las desigualdades sean tan sencillas como sea posible. inequalities are as simple as possible. 115. Un A cube cube with each edge 10 centimeters longde largo. 115. cubowith con each cada edge arista10 decentimeters 10 centímetros 115. A long 116. Una A cylindrical cylindrical shell 88demeters meters longde with an inside inside diameter of 116. capa cilíndrica 8 metros longitud, 0.75diameter metros of de 116. A shell long with an 0.75 meter meter and an any outside outside diameter of 1.25 1.25 meters diámetro interior un diámetro exterior de 1.25 metros. 0.75 and diameter of meters 117. Una A spherical spherical shell with with inside and outside radii of ofde inches and 117. capa esférica con inside radios and interior y exterior 4 pulgadas 117. A shell outside radii 44 inches and inches, respectively y66 6inches, pulgadas, respectivamente. respectively 118. El The solid que that queda remains after aa de hole inch in in diameter is drilled drilled 118. sólido después perforar undiameter orificio de 1 pul118. The solid that remains after hole 11 inch is through the center of a sphere 6 inches in diameter gada de diámetro a través del centro de una esfera de 6 pulthrough the center of a sphere 6 inches in diameter de diámetro. 1 yy22 1 1 zz22 5 5 99 and 119. gadas The solid solid inside both both xx22 1 and 119. The inside 2 2 2 2 119. El sólido dentro tanto de x 1 y 1 z 5 9 como de 2 332 dd2 1 1 yy 22 5 5 994 ssxx 2 32 2 94 2 x 2 2 solid 5 4. d 1 y between 1 yy22 1 1 zz22 5 5 44 and 120. sThe The the spheres spheres xx22 1 and 120. solid between the 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 1 y 2 1 z 2 5 9, and inside 2 2 2 z x 5 x 1 y the cone 2 1cone x sólido 1y 1 z 5 and inside 120. El entre las9, esferas x2 1 ythe z2 = z4 y5x2x11 y2y1 z2 = 9, y dentro del cono z 2 5 x 2 1 y 2. True or or False? False? In In Exercises Exercises 121–124, 121–124, determine determine whether whether the the True statement is true or false. If it is false, explain why or give an ¿Verdadero En losIfejercicios 121explain a 124, determinar la statement iso falso? true or false. it is false, why or givesian example that shows it is false. declaración es verdadera o falsa. Si es falsa, explicar por qué o example that shows it is false. dar un ejemplo que pruebe que es falsa. 5 zz is 121. In In cylindrical cylindrical coordinates, coordinates, the the equation equation rr 5 is aa cylinder. cylinder. 121. 2 2 2 121. cilindro.the 5 22 and 1 yy 2 1 1 zzr 2=5 5z es 122. En Thecoordenadas equations rrcilíndricas, and laxx 2ecuación represent the 5 1 44 un 122. The equations represent sameecuaciones surface. r 5 2 y x 2 1 y 2 1 z 2 5 4 representan la 122. Las same surface. superficie. x, y, y, zzdd are 123. misma The cylindrical cylindrical coordinates of of aa point point ssx, are unique. unique. 123. The coordinates 123. Las coordenadas cilíndricas de un punto (x, y, z) son únicas. s x, y, z d 124. The spherical coordinates of a point are unique. 124. The spherical coordinates of a point sx, y, zd are unique. 124. Las coordenadas esféricas de un punto (x, y, z) son únicas. 125. Identify Identify the the curve curve of intersection of of the the surfaces surfaces (in (in cylindrical cylindrical 125. 125. Identificar la curvaofdeintersection intersección de las superficies (en coor5 sin sin uu and 5 1. 1. coordinates) zz 5 and rr 5 coordinates) denadas cilíndricas) z 5 sen q y r 5 1. 126. Identify Identify the curve of of intersection of of the surfaces surfaces (in (in spherical spherical 126. 126. Identificarthela curve curva deintersection intersección dethe las superficies (en coorr 5 2 sec f r 5 4. coordinates) and r 5 2rsec coordinates) andfr y5r 4. denadas esféricas) 5 2f sec 5 4. Larson-11-08-R.qxd 3/12/09 18:06 Page 829 Ejercicios de repaso Ejercicios de repaso 11 \ \ En los ejercicios 1 y 2, sean u 5 PQ y v 5 PR , a) escribir u y v en la forma de componentes, b) escribir u como combinación lineal de vectores i y j unitarios estándar, c) encontrar la magnitud de v y d) encontrar 2u + v. 1. P 5 s1, 2d, Q 5 s4, 1d, R 5 s5, 4d 2. P 5 s22, 21d, Q 5 s5, 21d, R 5 s2, 4d 8, 60 4. v 1 2, 225 5. Hallar las coordenadas del punto en el plano xy cuatro unidades a la derecha del plano xz y cinco unidades detrás del plano yz. 6. Hallar las coordenadas del punto localizado en el eje y y siete unidades a la izquierda del plano xz. En los ejercicios 7 y 8, determinar la localización de un punto (x, y, z) que satisface la condición. 7. yz > 0 En los ejercicios 21 y 22, determinar si u y v son ortogonales, paralelos, o ninguna de las dos cosas. 21. u 5 k7, 22, 3l 22. u 5 k24, 3, 26l v 5 k21, 4, 5l v 5 k16, 212, 24l En los ejercicios 23 a 26, hallar el ángulo u entre los vectores. En los ejercicios 3 y 4, encontrar las componentes del vector v dada su magnitud y el ángulo que forma con el eje x positivo. 3. v 829 8. xy < 0 En los ejercicios 9 y 10, hallar la ecuación estándar de la esfera. 9. Centro: s3, 22, 6d; diámetro: 15 10. Puntos terminales de un diámetro: (0, 0, 4), (4, 6, 0) 23. u 5 cos 3 4i v 2 cos 2 3i sen 2 6i 3k, v 24. u 25. u 10, 26. u 1, 0, 2j 5, 15 , sen 3 4j 3j 5j i 2, 1, v 3, v 2, 3 2, 1 27. Hallar dos vectores en direcciones opuestas que sean ortogonales al vector u 5 k5, 6, 23l. 28. Trabajo Un objeto es arrastrado 8 pies por el suelo aplicando una fuerza de 75 libras. La dirección de la fuerza es de 30° sobre la horizontal. Encontrar el trabajo realizado. < > < > En los ejercicios 29 a 38, sea u 5 3, 22, 1 , v 5 2, 24, 23 ,y w 5 21, 2, 2 . < > 29. Probar que u ? u 5 i u i2. 30. Hallar el ángulo entre u y v. En los ejercicios 11 y 12, completar el cuadrado para dar la ecuación de la esfera en forma canónica o estándar. Hallar el centro y el radio. 11. x2 12. x2 1 y2 1 y2 1 z2 2 4x 2 6y 1 4 5 0 1 z2 2 10x 1 6y 2 4z 1 34 5 0 31. Determinar la proyección de w sobre u. 32. Calcular el trabajo realizado al mover un objeto a lo largo del vector u si la fuerza aplicada es w. 33. Determinar un vector unitario perpendicular al plano que contiene a v y a w. En los ejercicios 13 y 14 se dan los puntos inicial y final de un vector, a) dibujar el segmento de recta dirigido, b) encontrar la forma componente del vector, c) escribir el vector usando notación vectorial unitaria estándar y d) dibujar el vector con su punto inicial en el origen. 34. Mostrar que u 3 v 5 2 sv 3 ud. 13. Punto inicial: s2, 21, 3d 38. Calcular el área del triángulo con lados adyacentes v y w. 14. Punto inicial: s6, 2, 0d Punto terminal: s4, 4, 27d 35. Calcular el volumen del sólido cuyas aristas son u, v y w. 36. Mostrar que u 3 sv 1 wd 5 su 3 vd 1 su 3 wd. 37. Calcular el área del paralelogramo con lados adyacentes u y v. Punto terminal: s3, 23, 8d En los ejercicios 15 y 16, utilizar vectores para determinar si los puntos son colineales. 15. s3, 4, 21d, s21, 6, 9d, s5, 3, 26d 39. Momento Las especificaciones para un tractor establecen que el momento en un perno con tamaño de cabeza de 78 de pulgada no puede exceder 200 pies-libras. Determinar la fuerza máxima i F i que puede aplicarse a la llave de la figura. 16. s5, 24, 7d, s8, 25, 5d, s11, 6, 3d 17. Hallar un vector unitario en la dirección de u 5 k2, 3, 5l. 2 pies 18. Hallar el vector v de magnitud 8 en la dirección k6, 23, 2l. \ \ En los ejercicios 19 y 20, sean u 5 PQ y v 5 PR ., Hallar a) las componentes de u y de v, b) u · v y c) v ? v. 19. P 5 s5, 0, 0d, Q 5 s4, 4, 0d, R 5 s2, 0, 6d 20. P 5 s2, 21, 3d, Q 5 s0, 5, 1d, R 5 s5, 5, 0d 50° 7 8 pulg 70° F Larson-11-08-R.qxd 830 3/12/09 18:06 CAPÍTULO 11 Page 830 Vectores y la geometría del espacio 40. Volumen Usar el producto escalar triple para encontrar el volumen del paralelepípedo que tiene aristas adyacentes u 5 2i 1 j, v 5 2j 1 k,y w 5 2j 1 2k. En los ejercicios 41 y 42, hallar el conjunto de a) ecuaciones paramétricas y b) ecuaciones simétricas de la recta a través de los dos puntos. (Para cada recta, dar los números directores como enteros.) 41. s3, 0, 2d, s9, 11, 6d 42. s21, 4, 3d, s8, 10, 5d En los ejercicios 43 a 46, a) hallar un conjunto de ecuaciones paramétricas para la recta, b) encontrar un conjunto de ecuaciones simétricas para la recta y c) dibujar una gráfica de la recta. 43. La recta pasa por el punto (1, 2, 3) y es perpendicular al plano xz. 44. La recta pasa por el punto (1, 2, 3) y es paralela a la recta dada por x 5 y 5 z. 45. La intersección de los planos 3x 2 3y 2 7z 5 24 y x 2 y 1 2z 5 3 46. La recta pasa por el punto (0, 1, 4) y es perpendicular a u 5 k2, 25, 1l y v 5 k23, 1, 4l. En los ejercicios 47 a 50, encontrar una ecuación del plano. 59. x2 y2 1 1 z2 5 1 16 9 60. 16x 2 1 16y 2 2 9z 2 5 0 61. y2 x2 2 1 z 2 5 21 16 9 62. x2 y2 z2 1 2 51 25 4 100 63. x 2 1 z 2 5 4 64. y 2 1 z 2 5 16 65. Hallar una ecuación de una directriz de la superficie de revolución y 2 1 z 2 2 4x 5 0. 66. Encontrar una ecuación de la curva generadora de la superficie de revolución x2 1 2y2 1 z2 5 3y. 67. Determinar una ecuación para la superficie de revolución generada al rotar la curva z 2 5 2y en el plano yz alrededor del eje y. 68. Encontrar una ecuación para la superficie de revolución generada al rotar la curva 2x 1 3z 5 1 en el plano xz alrededor del eje x. En los ejercicios 69 y 70, convertir las coordenadas rectangulares del punto a a) coordenadas cilíndricas y b) coordenadas esféricas. 47. El plano pasa por (23, 24, 2), (23, 4, 1) y (1, 1, 22). 48. El plano pasa por el punto s22, 3, 1d y es perpendicular a n 5 3i 2 j 1 k. 49. El plano contiene las rectas dadas por 69. s22!2, 2!2, 2d 70. 1 43, 34, 3 2 32 ! ! En los ejercicios 71 y 72, convertir las coordenadas cilíndricas del punto en coordenadas esféricas. 1100, 2 p6 , 502 181, 2 56p, 27!32 x21 5y5z11 22 71. y En los ejercicios 73 y 74, convertir las coordenadas esféricas del punto en coordenadas cilíndricas. x11 5 y 2 1 5 z 2 2. 22 50. El plano pasa por los puntos (5, 1, 3) y (2, 22, 1) y es perpendicular al plano 2x 1 y 2 z 5 4. 51. Hallar la distancia del punto (1, 0, 2) al plano 2x 2 3y 1 6z 5 6. 52. Hallar la distancia del punto (3, 22, 4) al plano 2x 2 5y 1 z 5 10. 53. Hallar la distancia de los planos 5x 2 3y 1 z 5 2 y 5x 2 3y 1 z 5 23. 54. Hallar la distancia del punto s25, 1, 3d a la recta dada por x 5 1 1 t, y 5 3 2 2t, y z 5 5 2 t. En los ejercicios 55 a 64, describir y dibujar la superficie. 55. x 1 2y 1 3z 5 6 56. y 5 z 2 1 57. y 5 2z 58. y 5 cos z 72. 125, 2 p4 , 34p2 p 2p 74. 112, 2 , 2 2 3 73. En los ejercicios 75 y 76, convertir la ecuación rectangular a una ecuación en a) coordenadas cilíndricas y b) coordenadas esféricas. 75. x 2 2 y 2 5 2z 76. x 2 1 y 2 1 z 2 5 16 En los ejercicios 77 y 78, expresar en coordenadas rectangulares la ecuación dada en coordenadas cilíndricas y dibujar su gráfica. 77. r 5 5 cos u 78. z 5 4 En los ejercicios 79 y 80, expresar en coordenadas rectangulares la ecuación dada en coordenadas esféricas y dibujar su gráfica. 79. u 5 p 4 80. r 5 3 cos f Larson-11-08-R.qxd 3/12/09 18:06 Page 831 Solución de problemas 831 Solución de problemas SP 1. Utilizando vectores, demostrar la ley de los senos: Si a, b y c son los tres lados del triángulo de la figura, entonces sen A a sen B b 7. a) Hallar el volumen del sólido limitado abajo por el paraboloide z 5 x 2 1 y 2 y arriba por el plano z 5 1. b) Hallar el volumen del sólido limitado abajo por el parabo- sen C . c loide elíptico z 5 x2 y2 1 y arriba por el plano z 5 k, a2 b2 donde k > 0. B c) Mostrar que el volumen del sólido del inciso b) es igual a la mitad del producto del área de la base por la altura (ver la figura). a c A z C Base b E x 2. Considerar la función f sxd 5 !t 4 1 1 dt. Altura 0 a) Usar una herramienta de graficación para representar la función en el intervalo 2 x 2. b) Hallar un vector unitario paralelo a la gráfica de f en el punto (0, 0). c) Hallar un vector unitario perpendicular a la gráfica de f en el punto (0, 0). d) Hallar las ecuaciones paramétricas de la recta tangente a la gráfica de f en el punto (0, 0). 3. Utilizando vectores, demostrar que los segmentos de recta que unen los puntos medios de los lados de un paralelogramo forman un paralelogramo (ver la figura). y x 8. a) Usar el método de los discos para encontrar el volumen de la esfera x 2 1 y 2 1 z 2 5 r 2. b) Hallar el volumen del elipsoide y2 z2 x2 1 2 1 2 5 1. 2 a b c 9. Dibujar la gráfica de cada ecuación dada en coordenadas esféricas. a) r 5 2 sen f b) r 5 2 cos f 10. Dibujar la gráfica de cada ecuación dada en coordenadas cilíndricas. a) r 5 2 cos u b) z 5 r 2 cos 2u 11. Demostrar la propiedad siguiente del producto vectorial. 4. Utilizando vectores, demostrar que las diagonales de un rombo son perpendiculares (ver la figura). su 3 vd 3 sw 3 zd 5 su 3 v ? zdw 2 su 3 v ? wdz 12. Considerar la recta dada por las ecuaciones paramétricas x 5 2t 1 3, y 5 12t 1 1, z 5 2t 2 1 y el punto s4, 3, sd para todo número real s. a) Dar la distancia entre el punto y la recta como una función de s. 5. a) Hallar la distancia más corta entre el punto Qs2, 0, 0d y la recta determinada por los puntos P1s0, 0, 1d y P2s0, 1, 2d. b) Hallar la distancia más corta entre el punto Qs2, 0, 0d y el segmento de recta que une los puntos P1s0, 0, 1d y P2s0, 1, 2d. 6. Sea P0 un punto en el plano con vector normal n. Describir el conjunto de puntos P en el plano para los que sn 1 PP0d es el ortogonal a sn 2 PP0d. \ \ b) Usar una herramienta de graficación para representar la función del inciso a). Usar la gráfica para encontrar un valor de s tal que la distancia entre el punto y la recta sea mínima. c) Usar el zoom de una herramienta de graficación para amplificar varias veces la gráfica del inciso b). ¿Parece que la gráfica tenga asíntotas oblicuas? Explicar. Si parece tener asíntotas oblicuas, encontrarlas. Larson-11-08-R.qxd 3/12/0910:41 18:06 1053714_110R.qxp 10/27/08 AM Page Page 832 832 1053714_110R.qxp 10/27/08 10:41 AM Page 832 832 CAPÍTULO 11 Vectores y la geometría del espacio Chapter 11 Vectors and the Geometry of Space Chapter 11 Vectors and the Geometry of Space 832 832 13. Una pelota que pesa 1 libra sujetada por una cuerda a un poste 13. Aestetherball weighing 1 opuesta pound isalpulled from the pole lanzada en dirección poste outward por una fuerza horizonu until by horizontal force the rope makes an angle con of el tal au que hace que la cuerda forme un ángulo de q grados u figure). degrees with pole (see poste (ver la the figura). (a) Determine the resultingresultante tension inenthe andy the magnia) Determinar la tensión la rope cuerda la magnitud u when 30 . tude de u 5 308. u of cuando u 30 . (b) Write tension in cuerda the rope and the magnitude of ufunas b) Dar la the tensión T deTTla y la magnitud de u como u . functions of Determine the domains of the functions. ciones de q. Determinar los dominios de las funciones. . (c) Use auna graphing utility de to graficación complete thepara table. c) Usar herramienta completar la tabla. 0 0 10 10 20 20 30 30 40 40 50 50 16. Los Ángeles se localiza a 34.05° de latitud Norte y 118.24° de 16. Los Angeles is located at 34.05 North latitude and 118.24 longitud Oeste, y Río de Janeiro, Brasil, se localiza a 22.90° 34.05 Brazil 118.24 West longitude, Rio de Janeiro, is located de latitud Sur and y 43.23° de longitud Oeste (ver at la 22.90 figura). 22.90 South latitude and longitude (seeunfigure). Assume 43.23 esWest Suponer que la Tierra esférica y tiene radio de 4 000 South latitude and 43.23 Westa radius longitude (see figure). that Earth is spherical and has of 4000 miles. Assume millas. that Earth is spherical and has a radius of 4000 miles. zz z rMeridiano m rm meridian cero meridian yy y Los LosAngeles Ángeles Los Angeles 60 60 T T u u xx x (d) Use una a graphing utility to graph the functionslasfor d) Usar herramienta de graficación paratwo representar dos 0 60 . 0 60 . funciones para 0 60 . u as increases. (e) Compare TTand e) Comparar T y i u iua medida que u se aumenta. lím Tlím u . u .Are (f) Find (if possible) y lím the los reT y lím f ) Hallar (si es posible) ¿Son →lím 2 → T 2→lím2 → u2 . → 2 → 2 results yousexpected? e esperaba? Explain. sultadoswhat lo que Explicar. θθ θ θθ θ uu u lb 11libra 1 lb θθ θ Figure 13 13 Figurafor para Figure para for 1414 Figura 14. loaded barge is being towed by two andremolcadoras, the magniUna barcaza cargada es remolcada por tugboats, dos lanchas 14. A tude the resultant 6000 pounds alongdirigidas the axis aoflo y la of magnitud de la is resultante es de directed 6 000 libras the (see defigure). Each (ver towline makes Cada an angle of de largobarge del eje la barcaza la figura). cuerda degrees with the un axisángulo of thede barge. remolque forma q grados con el eje de la barcaza. 20 . si u 5 208. (a) Find the if remolque a) Hallar la tension tensión in dethe las towlines cuerdas del 20 . T (b) Write the tension of each line as a function of . Deterb) Dar la tensión T en cada cuerda como una función de q. T . mine the domain of thede function. Determinar el dominio la función. (c) Use auna graphing utility de to graficación complete thepara table. c) Usar herramienta completar la tabla. 10 10 20 20 30 30 40 40 50 50 60 60 T T (d) Use auna graphing utility de to graficación graph the tension function. la fund) Usar herramienta para representar ción tensión. (e) Explain why the tension increases as increases. e) Explicar the por qué la tensión medida q aumenta. , 0 queand u aumenta cos a, sen v 15. Consider vectors ,0 u . Find costhe, sen v cos , sen los , 0 vectores , where u 5 > kcos v 5 kcosofb,the 15. Considerar sen a, sen sin across , 0l y product cos , sen , 0 , > . vectors and use to el prove the identity a >thebresult . Hallar b, 0l, donde producto vectorial de los vectores y usar el resultado para demostrar la identidad cos sen . sen sen cos sen sen sen sinsa 2 bd 5sen sin acos cos b 2cos cos asen sin b. . sen Equator Ecuador Equator Rio Ríode deJaneiro Janeiro Rio de Janeiro a) Find Hallar coordenadas esféricas paralocation la ubicación cada (a) thelas spherical coordinates for the of eachdecity. (a) ciudad. Find the spherical coordinates for the location of each city. (b) Find the rectangular coordinates for the location of each (b) Find the coordinates for the of eachde b) city. Hallar lasrectangular coordenadas rectangulares paralocation la ubicación city. cada the ciudad. (c) Find angle (in radians) between the vectors from the (c) Find angleto(in between vectors thede c) center Hallarthe el Earth ángulo (en radianes) entre losthe vectores delfrom centro of theradians) two cities. center of Earth to the two cities. la Tierra cada ciudad. distance s between the cities. (d) Find thea great-circle s between (d) Find the distancemáximo theciudades. cities. d) Hallar s del círculo entre las Hint: sla distancia rgreat-circle s r Hint: (Sugerencia: 5 ru.)for the cities of Boston, located at (e) Repeat parts s(a)–(d) (e) Repeat North parts (a)–(d) the71.06 cities of Boston, located e) 42.36 Repetir los incisos a) afor d) con las ciudades de Boston, localilatitude and West longitude, andat 42.36 71.06 North latitude and West longitude, and zada a 42.36° latitudatNorte y HonoHonolulu, located North longitud latitude Oeste, and 157.86 21.31y 71.06° 21.31 157.86 Honolulu, located at North latitude and lulu, longitude. localizada a 21.31° latitud Norte y 157.86° longitud West West longitude. Oeste. 17. Consider the plane that passes through the points P, R, and S. R, Mostrar 17. Consider passes through the and S. 17.Show Considerar planothat que pasa por los puntos P, RP, y S. that the theelplane distance from a point thispoints plane is Q to Q Show that the distance from a point to this plane is que la distancia de un punto Q a este plano es u v w Distance u u vsv 3 w wd u? Distance Distancia Distance 5 u v iu 3 vi where u PR , v PS , and w PQ . w u PR , v where u 5 PR 5 PS PS,,yand w between 5 PQPQ . . the parallel planes donde that 18. Show the, v distance 18. Show the 18.ax Mostrar que entre los by planoscz paralelos by that cz lathedistancia d1 distance 0 and 0 is planes axbetween dparallel 2 ax 2 00 y axax1 byby1 czcz1 d2d5 esis ax 1 by by 1 cz cz 1 dd11 5 00and d 1 d2 Distance d 2 d2d 2 . 2 1d 2 Distance Distancia Distance 5 aa2 2 1bb2 2 2cc 2 .2 . !a 1 b 1 c 19. Show that the curve of intersection of the plane z 2y and the 19. Show that the theplano planezz5 2y the 2yyand 2 2curva 19.cylinder Mostrarxque la deintersection intersección el cilinan ellipse. ofdel ycurve 1ofis 2 2 x cylinder is an ellipse. y 1 2 2 dro xthe1article es unaTables: elipse. Solution of a Dental Problem y 5 1“Tooth 20. Read 20. Read theartículo article “Tooth Tables: Solution Dental Problemby 20.by Leer el “Tooth Tables: Solution ofofa aDental Problem Vector Algebra” by Gary Hosler Meisters in Mathematics by Vector Algebra” by Gary Hosler Meisters in Mathematics Vector Algebra” de Gary Magazine. (To view this Hosler article,Meisters go to entheMathematics website Magazine. this write article,a paragraph go to theexplaining website Magazine. (To view Then www.matharticles.com.) www.matharticles.com.) Then write a paragraph explaining how vectors and vector algebra can be used in the construction how vectors and vector algebra can be used in the construction of dental inlays. of dental inlays. | | \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ | \ | 1053714_cop12.qxd 10/27/08 11:47 AM 12-1.qxd 3/12/09 18:08 Page 833 12 12 Page 833 Funciones vectoriales Vector-Valued Functions En capítulo se introduce el concepto Thiseste chapter introduces the concept of de funciones vectoriales. También vector-valued functions. Vector-valued pueden emplearse para to estudiar functions can be used study curvas curves en in el plano y en el espacio. Esas funciones the plane and in space. These functions también parathe estudiar can also pueden be usedusarse to study motionelof movimiento de un objeto a lo largo de an object along a curve. una curva. In this chapter, you should learn the En este capítulo, se aprenderá: following. n Cómotoanalizar bosquejar curva ■ How analyzeyand sketchuna a space en el espacio representada por una curve represented by a vector-valued función vectorial. Cómothe aplicar los of function. How to apply concepts conceptos de límites y continuidad a limits and continuity to vector-valued 12.1 ) las funciones vectoriales. ( functions. (12.1) ■ n ■ n n ■ ■ n Cómotoderivar e integrar How differentiate andfunciones integrate vectoriales. (12.2 ) vector-valued functions. (12.2) How describelathe velocity yand Cómotodescribir velocidad acceleration associated with vectoraceleración asociada con unaafunción ■ valued function use a vectorial y cómoand usarhow unatofunción vector-valued to movimiento analyze vectorial para function analizar el projectile motion. (12.3 de proyectiles. (12.3 ) ) How to find tangent vectors and normal Cómo encontrar vectores tangentes y vectors. (12.4) vectores normales. (12.4) How to find the arc length and curvature Cómo encontrar of a curve. (12.5)la longitud de arco y la curvatura de una curva. (12.5) Jerry Driendl/Getty Images A Ferris wheel constructed using the usando basic principles of a básicos bicycle wheel. can Una rueda de laisfortuna está construida los principios de una You bicicleta. ■ use a vector-valued function to analyze the motion of a Ferris wheel, including its Se puede usar una función vectorial para analizar el movimiento de una rueda de la position and velocity. (See P.S. Problem Solving, Exercise fortuna, incluidas su posición y velocidad. (Ver solución de 14.) problemas, ejercicio 14.) v(1) v(2) v(1) v(2) v(1) v(1) v(0) v(0) v(0) v(0) v(1) v(2) v(2) v(1) v(0) v(0) v(0) v(0) v(3) v(3) a(2) a(2) a(1) a(1) a(0) a(0) a(0) a(0) a(1) a(1) a(0) a(0) a(2) a(2) a(3) a(3) a(1) a(1) a(0) a(0) A vector-valued function mapsnúmeros real numbers use usar a vector-valued to para represent the motion Una función vectorial mapea realestoa vectors. vectores.You Secan puede una funciónfunction vectorial representar el of a particle along a curve. In Section 12.3, you will use the first and second derivatives of a position vector to movimiento de una partícula a lo largo de una curva. En la sección 12.3 se usarán la primera y segunda derivadas find particle’s velocity and de unavector de posición paraacceleration. encontrar la velocidad y aceleración de una partícula. 833 833 12-1.qxd 3/12/09 1053714_1201.qxp 18:08 10/27/08 834 Page 834 11:48 AM CAPÍTULO 12 834 Chapter 12 Page 834 Funciones vectoriales Vector-Valued Functions 12.1 Funciones vectoriales 12.1 Vector-Valued Functions Analizar y dibujar una curva en el espacio dada por una función vectorial. n n Extender los conceptos de límite y continuidad a funciones vectoriales. Analyze and sketch a space curve given by a vector-valued function. Extend the concepts of limits and continuity to vector-valued functions. Curvas en el espacio y funciones vectoriales Space Curves and Vector-Valued Functions En la sección 10.2 se definió una curva plana como un conjunto de pares ordenados 10.2,con a plane curve was defined as the set of ordered pairs f t , g t sIn f stdSection , g stdd junto sus ecuaciones paramétricas together with their defining parametric equations x 5 f std y y 5 gstd x f t y gt and donde f y g son funciones continuas de t en un intervalo I. Esta definición puede extenwheredef manera and g are continuous functions of t on an interval Thiscurva definition be C derse natural al espacio tridimensional como sigue.I. Una en el can espacio extended naturally to three-dimensional space as space the set es un conjunto de todas las ternas ordenadas s f sfollows. td, gstd, hAstdd juntocurve con C susis ecuaciones of all ordered triples f t , g t , h t together with their defining parametric equations paramétricas xx 5 ffsttd,, yy 5 ggsttd,, yand z 5z hstdh t f, gg,yand h are where ƒ, continuous functions on intervalo an interval h son funciones continuas de tofent un I. I. donde Beforedelooking at examples of en space curves, se a introduce new type un of nuevo function, a Antes ver ejemplos de curvas el espacio, tipocalled de función, vector-valued introduced. This type of function real numbers llamada funciónfunction, vectorial.isEste tipo de función asigna vectoresmaps a números reales. to vectors. DEFINICIÓN DEOF FUNCIÓN VECTORIAL FUNCTION DEFINITION VECTOR-VALUED Una función of de the la forma A function form rsrtdt 5 f sftdti 1 i gsgtdtj j o or y r(t2) Espacio. rsrtdt 5 f sftdti 1 i gsgtdtj j1 hshtdtk k Space esisuna función vectorial, donde las funciones componentes ƒ, f,g g, y hand sonhfunciones a vector-valued function, where the component functions are del parámetro t. Algunas veces, las funciones vectoriales se denotan como real-valued functions of the parameter t. Vector-valued functions are sometimes rsdenoted td 5 k f sas td, rgsttdl o rfstdt 5 , grsttd, hstdl.f t , g t , h t . , g ktf stdor y r(t C 2) r(t1) r(t0) C r(t1) r(t0) Plano. Plane x Curve in a plane x Curva en un plano Técnicamente, una curva en el plano o en el espacio consiste en una colección de punTechnically, a curve in the plane or in space consists of a collection of points and tos y ecuaciones paramétricas que la definen. Dos curvas diferentes pueden tener la misma the defining parametric equations. Two different curves can have the same graph. For gráfica. Por ejemplo, cada una de las curvas dadas por instance, each of the curves given by z Curve in space r(t2) rt z r(t1) r(t0) Curva en el espacio r(t2)C r(t1) r(t0) Cy y x x C is traced out by the terminal point Curve of position vector r t . La curva Figure 12.1C es trazada por el punto final del vector posición r(t) Figura 12.1 sen t i cos t j y rt sen t 2 i cos t 2 j has the unit circle as its graph, but these equations do not represent the same curve— tiene como gráfica el círculo unidad o unitario, pero estas ecuaciones no representan la because the circle is traced out in different ways on the graphs. misma curva porque el círculo está trazado de diferentes maneras. Be sure you see the distinction between the vector-valued function r and the Es importante asegurarse de ver la diferencia entre la función vectorial r y las funreal-valued functions f, g, and h. All are functions of the real variable t, but r t is a ciones reales ƒ, g y h. Todas son funciones de la variable real t, pero r(t) es un vector, mienvector, whereas f t , g t , and h t are real numbers for each specific value of t . tras que ƒ(t), g(t) y h(t) son números reales (para cada valor específico de t). Vector-valued functions serve dual roles in the representation of curves. By Las funciones vectoriales juegan un doble papel en la representación de curvas. letting the parameter t represent time, you can use a vector-valued function to Tomando como parámetro t, que representa el tiempo, se puede usar una función vectorepresent motion along a curve. Or, in the more general case, you can use a vectorrial para representar el movimiento a lo largo de una curva. O, en el caso más general, se valued function to trace the graph of a curve. In either case, the terminal point of the puede usar una función vectorial para trazar la gráfica de una curva. En ambos casos, el position vector r t coincides with the point x, y or x, y, z on the curve given by the punto final del vector posición r(t) coincide con el punto (x, y) o (x, y, z) de la curva dada parametric equations, as shown in Figure 12.1. The arrowhead on the curve indicates por las ecuaciones paramétricas, como se muestra en la figura 12.1. La punta de flecha the curve’s orientation by pointing in the direction of increasing values of t. en la curva indica la orientación de la curva apuntando en la dirección de valores crecientes de t. 12-1.qxd 3/12/09 18:08 Page 835 SECCIÓN 12.1 Funciones vectoriales 835 A menos que se especifique otra cosa, se considera que el dominio de una función vectorial r es la intersección de los dominios de las funciones componentes ƒ, g y h. Por ejemplo, el dominio de rstd 5 sln td i 1 !1 2 t j 1 tk es el intervalo s0, 1g. y 2 EJEMPLO 1 Trazado de una curva plana 1 x −3 −1 1 Dibujar la curva plana representada por la función vectorial 3 rstd 5 2 cos ti 2 3 sen sin t j, 0 ≤ t ≤ 2p. Función vectorial. Solución A partir del vector de posición r(t), se pueden dar las ecuaciones paramétricas x 5 2 cos t y y 5 23 sen t. Despejando cos t y sen t y utilizando la identidad cos2 t 1 sen2 t 5 1 se obtiene la ecuación rectangular r(t) = 2 cos ti − 3 sen tj La elipse es trazada en el sentido de las manecillas del reloj a medida que t aumenta de 0 a 2p Figura 12.2 z x2 y 2 1 2 5 1. 22 3 Ecuación rectangular. La gráfica de esta ecuación rectangular es la elipse mostrada en la figura 12.2. La curva está orientada en el sentido de las manecillas del reloj. Es decir, cuando t aumenta de 0 a 2p, el vector de posición r(t) se mueve en el sentido de las manecillas del reloj, y sus puntos finales describen la elipse. Cilindro: x2 + y2 = 16 (4, 0, 4π) 4π EJEMPLO 2 Trazado de una curva en el espacio Dibujar la curva en el espacio representada por la función vectorial rstd 5 4 cos ti 1 4 sen sin t j 1 tk, 0 ≤ t ≤ 4p. Función vectorial. Solución De las dos primeras ecuaciones paramétricas x 5 4 cos t y y 5 4 sen t, se obtiene (4, 0, 0) x 4 y r(t) = 4 cos ti + 4 sen tj + tk A medida que t crece de 0 a 4p , se describen dos espirales sobre la hélice Figura 12.3 x 2 1 y 2 5 16. Ecuación rectangular. Esto significa que la curva se encuentra en un cilindro circular recto de radio 4, centrado en el eje z. Para localizar en este cilindro la curva, se usa la tercera ecuación paramétrica z 5 t. En la figura 12.3, nótese que a medida que t crece de 0 a 4p, el punto sx, y, zd sube en espiral por el cilindro describiendo una hélice. Un ejemplo de una hélice de la vida real se muestra en el dibujo inferior de la izquierda. En los ejemplos 1 y 2 se dio una función vectorial y se pidió dibujar la curva correspondiente. Los dos ejemplos siguientes se refieren a la situación inversa: hallar una función vectorial para representar una gráfica dada. Claro está que si la gráfica se da en forma paramétrica, su representación por medio de una función vectorial es inmediata. Por ejemplo, para representar en el espacio la recta dada por x 5 2 1 t, y 5 3t y z542t se usa simplemente la función vectorial dada por rstd 5 s2 1 td i 1 3tj 1 s4 2 td k. En 1953 Francis Crick y James D. Watson descubrieron la estructura de doble hélice del ADN. Si no se da un conjunto de ecuaciones paramétricas para la gráfica, el problema de representar la gráfica mediante una función vectorial se reduce a hallar un conjunto de ecuaciones paramétricas. 12-1.qxd 3/12/09 18:08 Page 836 1053714_1201.qxp 10/27/08 11:48 AM Page 836 1053714_1201.qxp 10/27/08 11:48 1053714_1201.qxp 10/27/08 11:48 AM 836 Page 1053714_1201.qxp 10/27/08 11:48AM AM Page Page 836 836 836 CAPÍTULO 12 Funciones vectoriales 836 Chapter 12 Vector-Valued Functions EJEMPLO 836 1212 Vector-Valued Functions Chapter 12 Vector-Valued Functions3 836 836Chapter Chapter Vector-Valued Functions Representar la parábola y 5 x 2 1 1 mediante una función vectorial. y t = −2 t = −2 t =t−2 = −2 t = −2 5 t = −14 3 y5 y y 4 5 5 3 4 4 2 3 3 Representación de una gráfica mediante una función vectorial EXAMPLE 3 3 Representing Representing a Graph by a Vector-Valued Function EXAMPLE a aGraph Function EXAMPLE 3 Representing a by Graph by a Vector-Valued Function EXAMPLE 3 Representing Graph bya aVector-Valued Vector-Valued Function t=2 y 5 t=2 t =t2= 2 t = 2 4 t=1 3 y = x2 + 1 t=1 2t =t1= 1 t = 1 x −2 −1 y 1=2 x 2 +2 1 2 t=0 t =t0= 0 t = y0 =y x= x+21y+ =1 x + 1 Hay muchas maneras de parametrizar esta t = −1 t 2= 0 t =t−1 2 = −1 t 2= −1 Solución Aunque hay given muchas el parámetro function. t, una opción natural es Represent the parabola by maneras y 52 x22 1de12elegir by a vector-valued Represent thethe given y 15 xsexy1 1 xby a vector-valued function. 2given Represent the parabola by 5 1 by a vector-valued function. Represent parabola by y y5 1 1 by a1 vector-valued function. tomar Entonces tiene x5 t. parabola ygiven 5 tby 1 Solution Although there are many ways to choose the parameter t, a natural choice Solution Although are2there many toways choose thethe parameter t,Función at, natural choice Solution areways many to choose the parameter t,vectorial. a natural Solution Although are many ways to choose parameter a natural choicechoice td 5 t i t.1Then sAlthough t 2 there 1ythere 15d2j. is torslet x5 t2 1 12 and you have is is to to letlet 5 t. Then 5 t t1 1 and have isx to let 5 t.y Then y5 t1 and 1you 1you and you have x5 t.x Then y5 1 have Nótese de parámetro. d 5latfigura i 1 2st2212.4 1 12la d j.orientación obtenida con esta elección particular Vector-valued function r sten r strhubiera dst5 trist1 st stti111 1como dst1j.d j.1parámetro Vector-valued function tidelegido 5 1d j. Vector-valued function d5 1 Vector-valued function Si se orientada en direcx 5 2t, la curva hubiera estado Noteopuesta. in Figure 12.4 the orientation produced by this particular choice of parameter. ción Note inNote Figure thethe orientation produced byby this particular choice of parameter. in 12.4 Figure 12.4 the orientation produced by this particular choice of parameter. Note in Figure 12.4 orientation produced this particular choice of parameter. Had you chosen x 5 2t as the parameter, the curve would have been oriented in the Had you chosen x5 2t2t the parameter, thethe curve have been oriented in in thethein the Had you chosen xas5as 2t asparameter, the parameter, thewould curve would have been oriented Had you chosen x5 the curve would have been oriented opposite direction. opposite direction. opposite direction. opposite direction. EJEMPLO 4 Representación de una gráfica mediante una función vectorial x − 2 −Una 1 de ellas1es tomar 2 x x x5 t x gráfica. EXAMPLE 4 4 Representing Representing a Graph by a Vector-Valued Function −2 − 2 −1 −−2 − 1 1 1 2 21 2 1 EXAMPLE apor by Function EXAMPLE 4 Representing Graph by adelVector-Valued Function EXAMPLE 4 CRepresenting aGraph Graph bya aVector-Valued Vector-Valued Function Figura 12.4 Dibujar la gráfica representada la aintersección semielipsoide There are many ways to parametrize this There areare many ways to to parametrize thisthis this Sketch the space curve C represented by the intersection of the semiellipsoid There are many ways to parametrize There many ways parametrize graph. One way is to let x 5 t. 2 2 thecurve 2 Sketch space Ccurve represented byby thethe intersection of of thethe semiellipsoid Sketch C represented byintersection the intersection ofsemiellipsoid the semiellipsoid xthe yspace zspace Sketch the curve C represented xis5 t.lett.x 5 t. graph. One wayway is to letlet graph. One xto5 graph. is way to FigureOne 12.4 z ≥ 0 21 21 25 1, x y 24z22 x 212 y 2x24 z yz 5 z1,2 z $ 0 x2 1 y22 1 1 1 24 111 451 1, 1, z5$ 12 5 z1,$0 0z $ 0 12 24 424 4 y 5 x 2. Después, hallar una función vectorial que represente la y el cilindro 12 12 24parabólico 4 and the parabolic cylinder y 52 x22. Then, find a vector-valued function to represent the gráfica. y5 x .xyThen, and thethe parabolic cylinder a vector-valued function to to represent thethe the x 2.find and the parabolic cylinder Then, a vector-valued function to represent and parabolic cylinder y5 .5 Then, find afind vector-valued function represent graph. graph. graph.graph. Solución En la figura 12.5 se muestra la intersección de las dos superficies. Como en el Solution The intersection of the two surfaces is shown in Figure 12.5. As in Solution The of ofthe two is es inCon 12.5. Solution The intersection two surfaces is t.shown in Figure 12.5. ejemplo 3, unaintersection opción natural para elthesurfaces parámetro esta opción, seinusa x5 Solution The intersection theof two surfaces isshown shown inFigure Figure 12.5.As As inAslain Example 3, a natural choice of parameter is x 5 t. For this choice, you can use the 2 2 x 5 t. Example 3, a natural choice of parameter is For this choice, you can use thethe 5 t.this Example choice of Forchoice, this choice, youuse can use the ecuación dada para obtener y3,5a xnatural y 5parameter t . Entonces Example 3, a natural choice of parameter is x 5is t.x For you can 2 2 given equation y 52 x2 to obtain it follows that y 52 t2 . Then, y5 x xto 5 t .tyThen, given equation obtain follows that y5 x2 toyobtain t 2.itThen, given equation it follows given equation y5 to obtain y5 .5 Then, it follows that that z2 x 2 2 y222 t2 t4 24 2t22 24 t424 s46 12 t22ds4 2 t2d 2 2 42 2 z 2 z 2 5 z12 2 x 2x 2 2 y xy 5y12 2t 2 t 2 2t 4t t24 5 24t24 2t24 2 t2tt 2 s6ts1 t ds 2 22 st64ds1 tt22dsdt42d 2 5 . td 2 2t 61 42 12 525 12 525 5 24 5 5 5 24 . . 5 12 1222 24 5 12 1222 24 . 45 5 12 12 44 2424 24 4 1212 2412 24 24 1212 2412 24 24 2424 24 NOTE Curves in space can be specified Because the curve lies above the xy-plane, you should choose the positive square root NOTE Curves inCurves space can be espacio specified xy-xyBecause curve above plane, should choose the positive square root NOTE in can bepuespecified xy-you Because the curve liesthe above plane, you should positive square root NOTE Curves in can be specified Because the curve lies above the plane, you should choose the positive square rootposiComo lathecurva selies encuentra sobre elthe plano xy, hay que elegirchoose para z the la raíz cuadrada NOTA Las curvas enspace el in various ways. Forspace instance, the curve for z and obtain the following parametric equations. in in various ways. For instance, themaneras. curve inespecificarse various ways. For instance, the curve z for and obtain the following parametric equations. various ways. For instance, the curve z for and obtain the following parametric equations. for z and obtain the following parametric equations. tiva. Así se obtienen las ecuaciones paramétricas siguientes. den de varias in Example 4 is described as the in in Example 4 is4 described as the Example 4curva is described as the Example described as the s6 12 t22ds4 2 t2d Porinejemplo, la del ejemplo intersection ofistwo surfaces in space. 4 se t ds 2 st64ds1 tt22dsdt42d 2 t2d x 5 t, y 52 t222, 2 and z 5 s6 s1 61 42 intersection of two surfaces in space. intersection of two surfaces in space. intersection of two surfaces in space. x x5 t, t,t,xy5 t t,ty,, 5 and z5 describe como la intersección de dos t,5 t y,and and 6 x5 5 y5 z5 z5 y5 66 6 superficies en el espacio. n The resulting vector-valued function is The resulting vector-valued function is is is The resulting vector-valued The resulting vector-valued function La función vectorial resultante es function 2ds4 2 t2d s 6 1 t t2ds 2 st624ds1 tt22dsdt42d 2 r std 5 t i 12 t22 j 1 2 s6 s1 k,t2d22 # t # 2. Vector-valued function 61 42 r strdst5 trist1 t jt i1 k, k, 22 function #t #2. tid 1 5 k,# #t22 2. Vector-valued function 6 d5 j11t j 1 22 Vector-valued function # 2.t #Vector-valued Función vectorial. 66 6 sNote that the k-component of rstd implies 22 # t # 2.d From the points s22, 4, 0d spoints sNote that thethe k-component of of rsk trdsde 22 points 22, 4, 022, d 0d4,4,0)0d #t 2. s4, sNote that thecomponente k-component of rstd implica implies 2.dthe From the s22, sNote that kel -component timplies d implies 22# t22 d#From the points #d2.tFrom (Obsérvese que r(t) De los puntos (22, and s2, 4, 0d shown in Figure 12.5, you can see #that #the curve is traced as t increases s2,s4, 4,0) 0dsque t increases and shown in Figure 12.5, you can seesee that the curve traced and 4,se0dmuestran shown inen Figure 12.5, you can see that theiscurve isas traced as t increases 2, 4, 02, d shown in Figure 12.5, you can that the is as yand (2, la figura 12.5, se ve que lacurve curva estraced trazada at increases medida que t from 22 to 2. 22 from to22 2.22 from from 22 to 2. crece de a 2.to 2. Figure 12.4 Figure Figure 12.4 12.4 !! !! !! !! z z Parabolic cylinder z zz Cilindro parabólico Parabolic cylinder Parabolic cylinder (0, 0, 2) Parabolic cylinder 2)2)(0, 0, 2) (0,(0, 0,0,2) (0, 0, 2 2 22 2 Ellipsoid Elipsoide Ellipsoid Ellipsoid Ellipsoid 4 4 44 Curve in Curve in en Curva in Curve in space Curve space el espacio space space (− 2, 4, 0) (−(−2, 2, (− (−4, 2,4,0) 4,0) 0)2, 4, 0) 4 x C: x = t xx=t=tC: C:C: x= C: y 2=t2tt22 x = t 2 y =yy= t= t y = t (6 2+ t22 )(4 2− 2t22 ) z = (6 (6 + t+)t(4 −(4+ t−2 t)t )t)2(4) − t 2 ) (6 t )(6 6(4 z =zz== z =1 6 66 6 (2, 4, 0) (2,(2, 4, 4, 0) (2, 4,0) 0)(2, 4,50)555 y y 5yy y The curveC Cesislathe intersection ofsemielipsoide the semiellipsoid and theparabólico parabolic cylinder. La curva delthe y eland cilindro The curve C isCcurve the intersección intersection of semiellipsoid the parabolic cylinder. cylinder. The C is the intersection of the semiellipsoid and the parabolic The curve Figure 12.5is the intersection of the semiellipsoid and the parabolic cylinder. Figura 12.5 Figure 12.5 Figure Figure 12.5 12.5 ■ ■■ ■ 12-1.qxd 3/12/09 18:08 Page 837 SECCIÓN 12.1 Funciones vectoriales 837 Límites y continuidad Muchas de las técnicas y definiciones utilizadas en el cálculo de funciones reales se pueden aplicar a funciones vectoriales. Por ejemplo, las funciones vectoriales se pueden sumar y restar, multiplicar por un escalar, tomar su límite, derivarlas, y así sucesivamente. La estrategia básica consiste en aprovechar la linealidad de las operaciones vectoriales y extender las definiciones en una base, componente por componente. Por ejemplo, para sumar o restar dos funciones vectoriales (en el plano), se tiene r1std 1 r2std 5 f f1std i 1 g1std jg 1 f f2std i 1 g2std jg Suma. 5 f f1std 1 f2stdg i 1 f g1std 1 g2stdg j r1std 2 r2std 5 f f1std i 1 g1std jg 2 f f2std i 1 g2std jg Resta. 5 f f1std 2 f2stdg i 1 f g1std 2 g2stdg j. De manera similar, para multiplicar y dividir una función vectorial por un escalar se tiene crstd 5 cf f1std i 1 g1std jg Multiplicación escalar. 5 cf1std i 1 cg1std j rstd f f1std i 1 g1stdj g 5 , cÞ0 c c 5 División escalar. f1std g std i 1 1 j. c c Esta extensión, componente por componente, de las operaciones con funciones reales a funciones vectoriales se ilustra más ampliamente en la definición siguiente del límite de una función vectorial. DEFINICIÓN DEL LÍMITE DE UNA FUNCIÓN VECTORIAL 1. Si r es una función vectorial tal que rstd 5 f std i 1 gstd j, entonces −L L t→a 3 t→a 4 3 4 Plano. siempre que existan los límites de f y g cuando t → a. 2. Si r es una función vectorial tal que rstd 5 f std i 1 gstd j 1 hstd k, entonces O r (t) 3 lim lim f std i 1 lím lim g std j lím rstd 5 lím t→a r(t) 4 3 t→a 4 3 4 lim lím hstd k lím f std i 1 lim lím rstd 5 lim lím g std j 1 lim siempre que existan los límites de f, g y h cuando t → a. t→a L O r(t) A medida que t tiende a a, r(t) tiende al límite L. Para que el límite L exista, no es necesario que r(a) esté definida o que r(a) sea igual a L Figura 12.6 t→a t→a Espacio. Si rstd tiende al vector L cuando t → a, la longitud del vector rstd 2 L tiende a 0. Es decir, i rstd 2 L i → 0 cuando t → a. Esto se ilustra de manera gráfica en la figura 12.6. Con esta definición del límite de una función vectorial, se pueden desarrollar versiones vectoriales de la mayor parte de los teoremas del límite dados en el capítulo 1. Por ejemplo, el límite de la suma de dos funciones vectoriales es la suma de sus límites individuales. También, se puede usar la orientación de la curva r(t) para definir límites unilaterales de funciones vectoriales. La definición siguiente extiende la noción de continuidad a funciones vectoriales. 12-1.qxd 3/12/09 1053714_1201.qxp 18:08 10/27/08 838 Page 838 11:48 AM CAPÍTULO 12 838 Chapter 12 Page 838 Funciones vectoriales Vector-Valued Functions DEFINICIÓN DE CONTINUIDAD DE UNA FUNCIÓN VECTORIAL Una función vectorial r es continua en un punto dado por t 5 a si el límite de rstd cuando t → a existe y DEFINITION OF CONTINUITY OF A VECTOR-VALUED FUNCTION lim rstd 5 rsad. lím t→a A vector-valued function r is continuous at the point given by t ⫽ a if the limit of r t exists as tr→ a and Una función vectorial es continua en un intervalo I si es continua en todos los puntos del intervalo. lim rt ⫽ ra. t→a A vector-valued function r is continuous on an interval I if it is continuous atDe every pointcon in the acuerdo estainterval. definición, una función vectorial es continua en t 5 a si y sólo si cada una de sus funciones componentes es continua en t 5 a. From this definition, it follows that a vector-valued function is continuous at Continuidad de funciones vectoriales tEJEMPLO ⫽ a if and5only if each of its component functions is continuous at t ⫽ a. Analizar la continuidad de la función vectorial EXAMPLE 5 Continuity of Vector-Valued Functions rstd 5 t i 1 aj 1 sa 2 2 t 2dk a es una constante. Discuss the continuity of the vector-valued function given by cuando 5t0. r tt⫽ i ⫹ aj ⫹ a 2 ⫺ t 2k a is a constant. at t ⫽ 0. Solución Cuando t tiende a 0, el límite es Solution As t approaches 0, the limit is lím a j 1 lím lim rstd 5 lim lim sa 2 2 t 2d k lím lím t i 1 lim t→0 t→0 t→0 t→0 lim rt ⫽ lim t i ⫹ lim a j ⫹ lim a 2 ⫺ t 2 k t→0 t→0 t→0 t→0 5 0i 1 aj 1 a 2 k ⫽ 0i ⫹ aj2 ⫹ a 2 k 5 aj 1 a k. ⫽ aj ⫹ a 2k. Como Because 3 z z 16 16 a = −a 4= −4 14 12 a = 4a = 4 14 10 10 −4 −4 8 6 6 4 4 2 2 2 2 4 4 x x 4 r0 ⫽ 0 i ⫹ a j ⫹ a 2k ⫽ aj ⫹ a 2 k For each value of a, the curve represented by the vector-valued function in Para 5, cada a, la curva representada por la función vectorial del ejemplo 5, Example 5 ti ⫹ 1 aj ⫹ 1 sa 2 ⫺ 2 t 2dk rrstd ⫽ 4 y 4 y a = 0a = 0 a = −2 a = −2 a = 2a = 2 For Para each value oflaa,curva the curve represented todo a, representada by the function porvector-valued la función vectorial 2 ⫺ 2t 2k 2 rt) r⫽stdti5⫹t iaj1⫹a ja1 sa 2 tis dakparabola. Figure 12.7 es una parábola Figura 12.7 4 3 you can conclude that r is continuous at t ⫽ 0. un Byrazonamiento similar reasoning, can continua en t 5 0. Mediante similar,you se concluye se concluye que r es conclude that the vector-valued function r is continuous at all real-number values que la función vectorial r es continua en todo valor real de t. of t. ■ 12 8 4 3 esauna constante. aa is constant. is parabola. YouUno canse think of imaginar each parabola of the vertical plane esauna parábola. puede cada as unathe deintersection estas parábolas como la intersección ydel ⫽plano a andvertical the hyperbolic paraboloid y 5 a con el paraboloide hiperbólico 2 yy22 ⫺ 2 xx 2 ⫽ 5 zz as shown in Figure 12.7. como se muestra en la figura 12.7. TECHNOLOGY Almost any type of three-dimensional sketch is difficult to do by TECNOLOGÍA cualquier de dibujo tridimensional es difícil hacerlo a hand, but sketchingCasi curves in spacetipo is especially difficult. The problem is in trying mano, perothe trazar curvas el espacio es especialmente problema consiste to create illusion ofenthree dimensions. Graphing difícil. utilitiesEluse a variety of en crear la impresión de tres dimensiones. Las herramientas decurves: graficación usanisdiversas techniques to add “three-dimensionality” to graphs of space one way to técnicas daronlaa“impresión dimensiones” en gráficas de curvas en el espacio: show thepara curve surface, as de in tres Figure 12.7. una manera es mostrar la curva en una superficie, como en la figura 12.7. 1053714_1201.qxp 10/27/08 10/27/08 11:48 AM AM Page 839 1053714_1201.qxp 12-1.qxd 3/12/09 18:08 11:48 Page 839 Page 839 839 839 839 SECCIÓN FuncionesFunctions vectoriales 12.112.1 Vector-Valued 12.1 Vector-Valued Functions Ejercicios 12.1 Exercises 12.1 Exercises 12.1 Seewww.CalcChat.com www.CalcChat.comforforworked-out worked-outsolutions solutionstotoodd-numbered odd-numberedexercises. exercises. See InExercises Exercises 1–8, thedomain domain thevector-valued vector-valued function. In 1–8, ofofthe function. En los ejercicios 1find afind 8, the hallar el dominio de la función vectorial. 11 tt 3tk ii j j 3tk 1 1 22 2 2 2.2.rsrtdt 5 !442 t 2t i i1 t 2tj j2 6t6tkk t 3.3.rsrtdt 5 lnlnt it i2 e et j j2 t kt k 1.1. rrt t InExercises Exercises 21–24, match theequation equation withits its graph. [The In 21–24, the with graph. [The En los ejercicios 21 amatch 24, asociar cada ecuación con su gráfica. graphs arelabeled labeled (a),(b), (b),(c), (c),a), and (d).] graphs are and [Las gráficas están(a), marcadas b),(d).] c) y d).] zz a)a) tt sint it i1 44cos cost jt j1 t kt k sin 4.4.rsrtdt 5 sen r t F t G t where 5. 5. rstd 5 Fstd 1 Gstd where donde cost it i2 sen sint jt j1 !t k, t k, GGstdt 5 cos cost it i1 sen sint jt j FFstdt 5 cos sin sin r t F t G t where 6. 6. rstd 5 Fstd 2 Gstd where donde 2 2 FFstdt 5 lnlnt it i1 5t5tj j2 3t3t2 k,k, GGstdt 5 i i1 4t4tj j2 3t3t2kk −2 −2 zz b)b) 44 44 22 22 22 yy −2 −2 x x 22 44 xx zz c)c) where 7.7.rsrtdt 5 FFstdt 3 GGstdt where donde sint it i1 cos cost j,t j, GGstdt 5 sen sint jt j1 cos cost kt k FFstdt 5 sen sin sin r t F t G t where 8. where 8. rstd 5 Fstd 3 Gstd donde 11 j 3 3 3t ti i1 t k, GGstdt 5 ! FFstdt 5 t 3t i i2 t jt j1 t k, j 1 st t1 22d kk t t1 11 zz d)d) 11 44 22 11 11 xx En ejercicios 9 a 12, evaluar(if (sipossible) es posible) la función vectoIn los Exercises 9–12, evaluate (if possible) the vector-valued In Exercises 9–12, evaluate the vector-valued t. rial en cada valor dado de functionatateach eachgiven givenvalue valueofoft.t. function 1 12 1 9. 9.9.rrsrttdt 5 22t2t 2t i2i i2 stt t2 111d jj j rsr0rd00 c)(c) rssrr1 a) (a)rrsr11d1 b)(b) (b) (c) s s1d 11 (a) 22 xx yy 44 yy 2tjjj 1 tt2t22k, k, 22 21. rrrstttd 5 ttitii 1 2t 22 ≤ ttt ≤ 222 21. 21. 2t k, cossptttdiii 1 sin sinsptttdjjj 1 tt2t22k, k, 21 22. rrrstttd 5 cos 11 ≤ ttt ≤ 111 22. cos sin k, 22. sen 2 0.75t 2t2 j 0.75t e k, r t t i 2 t 23. 0.75t 2 ≤ tt ≤ 222 23. k, 22 23. rrsttd 5 ttii 1 tt jj 1 ee k, 2t2t lnttjtjj 1 2tk, k, 0.1 0.1 t t 55 24. rrrstttd 5 ttitii 1 ln 24. ln 24. 333 k, 0.1 ≤ t ≤ 5 d) 2 Dtdt t2 rrs2r2d2 (d)rrs2r21 (d) sin 10. costt iit i1 222sen sintt jjt j 10.rrsrttdt 5 cos cos sin 10. r s 0 d r s p y4 rsurr2 pd a) b) (a) rr00 (b) (b) rr d44 c)(c) (c) (a) d) r y661 6 Dtdt t2 rrsp r y66d6 (d)rrsp (d) Para Las The cuatro figuras siguientes son graphs gráficas dethe la 25. 25. Think Thinkpensar About ItIt four figures below are are 25. About The four figures below t graphs ofof the función vectorial Asociar cada r s t d 5 4 cos t i 1 4 sin t j 1 k. sen cost it i 444sin sint jt j t t 44k.k. vector-valued function function rrt t 44cos vector-valued Match each thecon four graphsen with thepoint point space from una de each las gráficas elgraphs punto el espacio desde el cualfrom se ve Match ofofthe four with the ininspace 0, 0, 20,0), which the helix is viewed. The four points are 0, 0, 20 which the helix is viewed. The four points are la hélice. Los cuatro puntos son s0, 0, 20d, s20, 0, 0d, (220, 0, 20, 0, 0 , 20, 0, 0 , 10, 20, 10 . and 20, 0, 0 , 20, 0, 0 , 10, 20, 10 . and y s10, 20, 10d. zz zz (a) (b) (a) (b) z z a) b) 111 11. 11.rrsrttdt 5 ln lnlntt iit i1 t jj j1 3t 3t3tkkk 11. tt rsr23 rstr2 a) r d33 c)(c) rt t4d 44 (a)rrsr22d2 b)(b) (b) (c) (a) r s 1 1 Dt d 2 r s 1 d d) (d) rr11 t t rr11 (d) 3y2 2ty4 12. 12.rrsrttdt 5 !tt tii i1 tt 3t 32 2jj j1 eee t t4 4kkk 12. rsr4rd44 c)(c) rscrr1 a) (a)rrsr00d0 b)(b) (b) (c) cc2d 22 (a) d) 9 Dtdt t2 rrs9r9d9 (d)rrs9r91 (d) xx x || || InExercises Exercises 13and andy14, 14, find rrt t r. x.tc . In 13 En los ejercicios 13 14,find hallar y 13.rsrtdt 5 !t it i1 3t3tj j2 4t4tkk 13. 14. sin3t3ti i1 cos cos3t3tj j1 t kt k 14.rsrtdt 5 sen 14. 13. sin PtotoQQdesde InExercises Exercises 15–18, represent theline lineel segment from byaa In 15–18, the segment from by En los ejercicios 15 arepresent 18, representar segmento de Precta vector-valued function and by a set of parametric equations. vector-valued function andfunción by a setvectorial of parametric equations. P hasta Q mediante una y mediante un conjunto de ecuaciones paramétricas. 15. PP0,0,0,0,00, ,QQ3,3,1,1,22 16. PP0,0,2,2, 11, ,QQ4,4,7,7,22 15. 16. 15. P (0, 0, 0), Q (3, 1, 2) 16. P (0, 2, 21), Q (4, 7, 2) P 2, 5, 3 , Q( 1, 4, 9 17. 17. P 2, 5, 3 , Q( 1, 4, 9 17. 5, 23), (21, 6,8), 8),QQQ 3, 3, 2,4, 2,559) 18.P PP(22, 1,1, 6, 18. 18. P (1, 26, 8), Q (23, 22, 5) ThinkAbout AboutItIt In InExercises Exercises19 19and and20, 20,find findrrt t uut t. .IsIsthe the Think result vector-valued function? Explain. result aavector-valued function? Explain. Para pensar En los ejercicios 19 y 20, hallar rxtc ? uxtc. ¿Es el 1 resultado función vectorial? 4k,Explicar. 19. rrt t una , uut t t 2t 2i i 8j8j t 3t 3kk 3t3t 11i i 14 4t 3t 3j j 4k 19. 1 3 2sin t, cos1t,dt,i221 sin cos 20.rsrtdt 5 s3t 19. 2 i2 t 3t,kt,t 2t 2 33cos sin 22,,, uututstd 544tsin t, 8j661 cos 20. 4 tt,t,jt t1 4k 20. rstd 5 k3 cos t, 2 sin sen t, t 2 2l, yy 22 ustd 5 k4 sen sin t, 26 cos t, t l 2 yy y GeneratedbybyMathematica Mathematica Generated Generada con Mathematica GeneratedbybyMathematica Mathematica Generated Generada con Mathematica (c) (c) c) zz z (d) (d) d) yy y xx GeneratedbyxbyMathematica Mathematica Generated Generada con Mathematica GeneratedbybyMathematica Mathematica Generated Generada con Mathematica yy y 26. Sketch Sketch the the three three graphs graphs ofof the the vector-valued vector-valued function function 26. r t t i t j 2k as viewed from each point. r t t i t j 2k as viewed from each point. 26. Dibujar tres gráficas de la función vectorial rstd 5 t i 1 t j 1 2k (a) 0,0,desde 20los (b) (b) 10, 10,0,0,00 (a) 0,0,20 vistas puntos. a) s0, 0, 20d b) s10, 0, 0d (c) 5,5,5,5,55 (c) c) s5, 5, 5d 1053714_1201.qxp 10/27/08 11:48 AM 12-1.qxd 3/12/09 18:09 Page 840 1053714_1201.qxp 10/27/08 11:48 AM Page 840 Page 840 840 Chapter 12 840 840 Chapter CAPÍTULO Funciones Functions vectoriales Chapter12 1212 Vector-Valued Vector-Valued Functions Vector-Valued Functions In ExercisesChapter 27– 42, 12 sketchVector-Valued the curve represented by the vector840 Functions valued function and give the orientation of the curve. In 27– the by InExercises Exercises 27–42, 42,sketch thecurve curve represented bythe thevectorvectorEn los ejercicios 27 asketch 42, dibujar la represented curva representada por la valued and give valuedfunction function and give theorientation orientation thecurve. curve. función vectorial y dar lathe orientación de of laofthe curva. t 27. 28. r t rt i t 1j 5 ti tj In Exercises 4t 27– 42, sketch the curve represented by the vectort valued function and give the orientation of the curve. 27. 28. 5 ti tj 27.rrrtt t t43 ii i t 2t jt 11j j 28.rrrtt t 29. 30. t 25 t ti i t 2 t j t j 4 3 2 2 2 t 29. 30. rstd 5 t 3 ii3i 1 itt 2tjj2 3 sin rstd 5 st 2521 ttttidiii 12ssin t 2 2 tdj 31. 32. 29. 30. 27. 28. 29.rrt t tcos 30.rrt t 2t cos t i t j 1j j t i t t 2t jt jt tj j t 4 u i 1 3 sin sen tt jj sen 31. 32. r s u d 5 cos u j r s t d 5 2 cos t i 1 2 3cos 33. sec i ii 332sin tan j jj 31. 32. t i 22sin sin 31.r r 32. rrt t 22cos cos sin sin 3i 2j 2cos tt ii 2 tj 29. 30. r t t t r t t 3 rsud 5233cos sec3 ut ii 1 22 sin tan3 utjjj sin3 tjt j 33. 34. rstd 5 2 cos t i 1 2 tsen 34. 33. 3sec 33.r rt sec i 2tan tan j 31. rrstd 5 s2t 32.s2tr 1 cos1 i 3 sin j 2d j 1 t 2 cos t i 2 sin t j s4t 4t31 35. tcos3 3t11it diii 122sin 2t 33dkk 35. 34. sin3tjtj2 j 34.r rt t 22cos 33. rrstd 5 t i31secs2t i2 52d jtan 1 3t 3tj2k j 36. 36. 1 i i5 j 4t 35. 4t3 k 2 j 2t2t 33kk 35.r rt t t i t t 2t 3 t1 r t 2 cos i 2 sin tj t k 34. rsttd 5 22t icos cos tt2t i 1 225sin sin tjj3t1 37. sen r i t 37. j k 36. ti 2t 5 j 3t kt k 36. r t t 1i 4t 2 j 2t 3 k 35. r t r t ti 3 cos 38. tk 37. cost it i tj22sin sin3t jtsen j tk tk 37. r t 22cos ti 2t 5 j 3t k t 36. r t 39. 2t k 3t 3icos 38. cos2tjtjcos 3tt3jjsen senetktk 38.r rt t 2titisin 39. sen cost it i1 223cos sin t j1 et kt k 37. rrstdt 5 222sin 3 r t t i 2tj tk 40. it i 1 222cos 39. cost jt j ee tkk 39. r t 222sin i sin 1t32tj 40. tj23 3tk 3 sen tk 38. rrstdt 5 t ti 2 cos 2 3 2 t2tj 41. 40. t i2tit 2,, 3232tj 40.r rt t t t, t 3l 2 2tktk 41. e tk 39. rrstdt 5 k2t, sin 2t i2 3 2 cos t j 2 r t cos t t, sin tt 2 tt cos 42. 2 t,2t,t tt, ,313t ttt3sin 41. 41. rrstdt 5 kcos 3t, sen sin sin cos t,t, ttl 42. sen t i 2tj 2 tk 40. r t rrt t cos sin t,t,t t 42. cost246, t 2 t3use tsin sinat,t,computer sint t t tcos cos 42. CAS In Exercises 43– algebra system to graph the r tejercicios t, t ,43 41. CAS En 3 t a 46, usar un sistema algebraico por compulos vector-valued function and identify the common curve. CAS In 43– algebra totovectorial graph de función e r t a fin cos t46, t use sinat, singráficamente t t cos t, t lasystem 42. CAS tadora InExercises Exercises 43–representar 46,use acomputer computer algebra system graphthe the vector-valued function and identify the common curve. identificar la1curva común. vector-valued function and identify the common curve. 3 2 rt t2i tj t k CAS 43. In Exercises algebra system to graph the 2143– 46, use a computer 23 3 1 22 22 vector-valued function and identify ! 3 1 kk the common curve. 43. 43. rrrsttdt 5 2 2 tt 2t ii i31 tt jjt j2 12 tt 2t k 43. 2t22 k t i 22 t2j 44. r t 1 22 2 3 t i33 t j 11 t 2 k 43. r t kk 44. 2 !3 tt 22t 2jj3j1 1 2tt 22t 2k 44. rrrsttdt 5 tt iit i2 44. 1 1 3 2 222t sin t i 22 cos t j cos t k 45. r t 3 22 1 2 2 2 2 11 333 ti t j333 t k 111 44. r t ! ! 1 sin cos cos kk 45. 2 t i cos 2 tt t2t j tt t jj j21sin t k sintt 2iit i1 costt t1 2 k 45.rrrsttdt 5 sin cos 45. sen sin 2cos cos 46. 222 222 222 22 3 1 1 3 2i2sin sin cos sin k 46. t47tt jjtand j 222sin k 45. sin 2cos cos j1t ! sinttak tcos k t 46. rrrsttAbout !t2 sen dt 5 2sin tt iit i21 22cos 46. sen CAS Think It In Exercises use 2 48, 2 computer 2 algebra rcomputer t . For each ut, systemAbout to graph In theExercises vector-valued function CAS 47 algebra rpensar tAboutItIt sinejercicios t i 2 cos t and jyand 2 use sin tak 46. CAS Think Think In Exercises 47 48, use asistema computer algebra CAS Para En2los 48,48, usar un algebraico make atoconjecture about the47transformation (if any) of uthe r t . system graph the vector-valued function For each r t . Forlaeach ut t, , system to graph the vector-valued function por computadora fin de representar gráficamente función r t .ItUseInaaExercises of computer algebra system to any) verifyalgebra your CAS graph Think About 47 and 48, use a computer make a conjecture about the transformation (if of the make a conjecture (if any) of the vectorial cada the conjeturar sobre la transrxtc. Para about uxtc,transformation conjecture. r t .toto ut, system torrgraph the vector-valued function For eachyour t t. .Use graph aacomputer algebra verify graphofof computer algebra verify your formación (si laUse hay) de la gráfica de system un sistema rsystem x tc. Usar make a conjecture about the1 tk transformation (if any) of the conjecture. conjecture. r t 2 cos t i 2 sin tj 47. algebraico por computadora para verificar la conjetura. 2 graph of r t . Use a computer1 algebra1 system to verify your 1tk t j u t 2 cos t 1 i 2 sin (a) r t 2 cos t i 2 sin tj 47. 2t k 2 cos t i 2 sin tj 12 2 tk 47. r t conjecture. 47. rstd 5 2 cos t i 1 2 sin sen tj 1 2 tk 1 u t 2 cos t i 2 sin t j 2t k (b) (a) 2cos cost t 11i i 221sin sint jt j 12 12t k tk (a) u t 2 cos t i t 22 sin tj 47. a)r tustd 5 2 s cos 1 d i 1 2 sin sen 2 tkt j 1 2 t1 k u t 2 cos t i 2 sin t j (c) u t 2 cos t i 2 sin t j 2t k (b) 2 2 cos t i 2 sin t j 2t k 1 t k (b) u t cost i t1 21sen i t j21sin2ttkj 121t k b)(a)uusuttdt5 21t2cos sin 2sin costttk (d) t ti it j 22sin j j 2 2 t tkk (c) cos2 sin (c) u t 222icos u t 2 cos t i 2 sin tsj2t1d 2t k 1s2td k (b) 1cos sen c) u s t d 5 2 s 2t d i 1 2 sin jtkk1 1 u t 6 cos t i 6 sin t j t (e) t i 2 sin t j 2 cos u t (d) 2 (d) u t 2 2t i 2 sin t j 2 cos t k 2 1 (c) u t 1 22 cos 1 3t i 2 sin 1 1t j 2 t k d)(e) sin 1 j1 t uusutdttt5 i 26tt16icos 48. r(e) cos2t it2sen it kt6j6sin sin2t jtcos j 2tt2kk tk 213sin t j 21 cos tk (d) u t 22t i 1 2 31 e) u s t d 5 6 cos 6 sin t j 1 t k sen u t t i 2 j t k (a) 2j t ti 1 3 j t k r t t i t 48. 2 2 ti t 48. r t 22 t k 1 (e) u t 16 3sin t 1j 2t k 26 cos t i 3k (a) 48. (b) r(a) std u5ut t i 1t iti2i2j 1t j2t1212t 33k22t2jkj 2 12t 3t k t i 2t j 2 2 t k11133 48. r t (c) 3 k 1 43 k i2 i t t2jjt j 22ttt k (b) (b)uuusuttdt t5 tttiit1 1 a)(a) ut t i st22t 22 21d1223j1 3j1 2 t2 tk3 k u t t i t j t k (d) 2 3 1 t 4 (c) 2 3 8 j t 4kk u t t i t (c) 2 1 b)(b)usutd t5 t ti21 i t 2jt 1 j 21t21223tk3 k 1 j t 3k u t t i t (e) 2 3 1 u t t i t j t k (d) 2 i 2 t j s 8 t813t 1 k (d)usutd t5 t i t1 c)(c) j 2 22t 3 41d41k k 3 ut t i t tj21 t ti 2i 2 1 t13t 3j2j 2 2 t t k3k (e) (e)uusutdt t5 49– In Exercises d)(d) t tj represent 1 u t t it1 i 56, j 8t8tk k the plane curve by a vectorvalued function. (There are many 1 1 correct 3k answers.) In curve e) 2t it56, 1 srepresent 2td2tj21 kplane j 2sthe i represent (e)usutd t5 s49– In Exercises Exercises 49–d56, thed3tplane curve by by aa vectorvector22t valued function. (There are many correct valued (There are many answers.) y function. x 5 2x answers.) 3y 5 0 49. 50.correct In los Exercises 49– represent the plane curve by por a vectorEn ejercicios 4956, a 56, representar la curva plana medio 2 y y function. y2x 4 3y 51. 52. xxx 525 2vectorial. 00 49. 50. 2xrespuestas 3yx 55 correctas.) 49.una 50. valued (There are many correct answers.) de función (Hay muchas 2 xx2 2 51. 52. 51. yy xx 22 2 52. yy 2443y 1 49. 50. 2x 3y 555 00 49. yy5 xx1 55 50. 2x 51. 52. 51. yy5 sxx2 22d22 52. yy5 442 xx22 1 2 1 2 53. x 2 x 222 y2 yy222 25 54. x x2 2 2 2y 2222 y2 4 y 222 53. 54. 53. x 1 y 525 54. sxx 2 2d 11y 544 125 55. 56. 16 4 22 22 x9x2 2 16 x y yy2 2 55. 56. 53. xx2 2 yy2 5125 54. x 2 2 1y12 4 1 55. 56. 16 99 16 16 162 44257 and 58, find vector-valued In Exercises functions forming the x2 x y y2 1 region in the figure. 1 55. 56. State the interval boundaries of the for the In 58, vector-valued forming 16 ejercicios 4 57 9 functions 16vectoriales InExercises Exercises 57and and 58, findhallar vector-valued functions forming the En los 57 y find 58, funciones que the desparameter of each function. boundaries ofofthe ininthe State for boundaries theregion region thefigure. figure. Statethe theinterval interval forthe the criban los límites de la región en la figura. Dar el intervalo coIn Exercises andfunction. 58, find vector-valued parameter ofof57 each y functions forming the y parameter each function. 57. 58. función. rrespondiente al parámetro de cada boundaries of the interval for the y =the x 2 region in the figure. State 57. 58. 57. 5 yyy 58. 12 yyy parameter of each function. 57. 58. 2 2 10 x + y = 100 yyy===xxx222 4 1212 55 5 y y 57. 3 58. 10812 xxx222+++yyy222===100 10 44 100 610 100 y = x2 88 2 45 12 4 8 33 66 2 2 1 34 210 6 45° x + y = 100 22 484 2 x x 4 131 1 2 3 4 5 262 2 45° 445° 6 8 10 12 1 2 45° 2 xx xx 4 x x 2 2 4 4 6 6 8 8 10101212 111 222 333 444 555 1 2 represented 4 6 8 10 12 by the 2 In Exercises 59– 66, sketch the space curve 45° x x intersection of the surfaces. Then represent the curve by a In the 2 represented 4 6 8 10 12 by 1 259– 3 66, 4 sketch 5 InExercises Exercises 59– 66, sketch thespace spacecurve curve represented bythe the vector-valued function the given curva parameter. En los ejercicios 59surfaces. a using 66, dibujar en the el repreintersection ofof the Then curve intersection the surfaces. Thenlarepresent represent theespacio curve by by aa sentada por la intersección de las superficies. Después represenIn Exercises 59– 66, sketch the space curve represented by the vector-valued vector-valued functionusing usingthe thegiven givenparameter. parameter. Surfaces function Parameter tar la curva por medio de una función vectorial usando intersection of the surfaces. Then represent the curve by ael zSurfaces x 2 dado. xParameter t y 2function , x yusing 0 the given parameter. 59. Surfaces Parameter parámetro vector-valued 22 22 x x 2t tcos t 60. 59. 59.z z x x 2 y y,2, zxx 4yy 00 Superficies Parámetro Surfaces Parameter 2 2 2 2 2 x x 22sin 61. cos 60. costt t 60.xzz xyx22 yy4,2,2, zz 4x4 59. z2 25 x 2 12 y , 2 x 1 y2 5 0 x5t 2 4x z t 4y z 16, x z 62. 2 2 2 xx 22sin 61. sint t 61. xx yy 4,4, zz xx 60. z2 25 x 22 12 y 22, 2 z 5 4 x 5 2 cos t 22 x x 1 x z 2 63. 2 y 4y 2z z 24, 16, 4x z t x z 62. z t sin t 4y z 16, x z 62. 4x 61. x222 1 y222 5 4, z 5 x2 x 5 2 sin sen t 22 x x y z 10, x y 4 64. 2 2 2 63. x 211 sin sint t 63. x 2 y 2 z 2 4,4, xx zz 222 1 4y 1 z 5 16, x 5 z z 5 t 62. 4x 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 x x t22firstsin octant 65. tt zz 2 y 10, 64. sin 10, z xx 4yy 44 64.x x 2 zyy 2 4, 63. x222 1 y222 1 z2 2 524, x2 1 z 5 2 sen t x 5 1 1 sin y z 16, xy 4 x x t first octant 66. 2 2 2 2 65. x t first octant 65. x zz 4,4, yy zz 44 64. x22 1 y22 1 z22 5 10, x 1 y 5 4 x 5 2 1 sen sin t 2 2 2 y z 16, xy 4 x x 66. y2 thez vector-valued 16, xy 4 x 2 that x t t first firstoctant octant 66.Show 2 2 67. function octante) sfirst octant d 65. x 1 z 5 4, y 1 z 5 4 x 5 t (primer 2 2 5 sfirst octant d 66. octante) ytthat z 2vector-valued 16, 4function xShow x 5 t (primer 67. t 1 that i 1the 2t cos tj xy 2t 5 sinfunction tk 67.rShow the vector-valued lacos función vectorial 67. rMostrar 2 tj y2t 22tsin 2 it ique 2t2t tk.tkSketch the curve. rt t on tthe cos sin zfunction 4x tj cone 67. lies Show that the vector-valued r s t d 5 t i 1 2t cos tj 1 2t sin sen 2 2 68. Show that function zz2tk .2.Sketch 4x lies the cone 4xtj2 yy2t2 sin on cone Sketchthe thecurve. curve. rlies t on tthe i the 2tvector-valued cos tk 2 2 2 t cos 5 se el cono 68. that the t encuentra ethat tvector-valued ivector-valued e t sin4xtj function ey t1 k z . Dibujar la curva. 68.rShow Show theen function lies on the cone 4x 2 y 2 z 2. Sketch the curve. 68. rMostrar que la ifunción t t vectorial ee t kt k the curve. rt t on ethe e tcos costvector-valued tzi 2 eex 2tsin sintjytj2function . Sketch cone 68. lies Show that the 2t 2t rstdon 5 e t cone cos t iz 21 e x t2 sen sin tj e2tt k the curve. yy2.21 lies x 2sin .Sketch z 2 ethe cone Sketch the curve. rlies t onthe ethe cos t ifind tj e it kexists). In Exercises 69–74, limit (if se encuentra en el2 cono2z 2 52x 2 1 y 2. Dibujar la curva. In 69–74, zfind xthelimit y . (if lies tion the cone Sketch the curve. InExercises Exercises 69–74, limit (ifititexists). exists). cos tj find senthe tk lím 69. t→ En los 74, evaluar titi cos sen tk lím 69. 1tk limit el(iflímite. cos2tj69 tj afind senthe límejercicios 69.Exercises In 69–74, it exists). t→ t→ 3ti j k 70. lím t→2 t2 2 1 t 1 1k lím ti3ti cos tj2 j jsen tk 69. 70. lím 3ti 70. lím t→ t t→2 t2 2 1 1 cos tt k t→2 2 t i 3tt j 1 k 71. lím 2 1 t→0 tcos 1 j kt t 70. lím 3ti 1 cos 22 2 71. t→2 t k j t1 lím t t i i 3tt3tjln 71. lím t→0 t 1 k t→0 ti j t k 72. lím 2 t→1 t 11 cos t 1t 1 j lnt t 71. lím t 2 i 3t ln 1k k lím t i j 72. t→0 t lím t i sen 72. t→1 t 2t 2t 11 j t t t 11 k t→1 t ei j e k 73. lím ln t 1 t→0 t t j t k 72. lím t t t i sen 2 tj 1 e t k eei i sen 73. t→1 t t 1 k lím j e 73. lím t t→0 t1t t→0 e ti j k 74. lím 2 sen t t→ 1t 1 j t et tt1k 73. lím e t it t e i j 74. lím t→0 t 74. t→lím e i t j t 2 2 1 kk t→ t t 1 1 t j k 74. lím e t i t→ t t2 1 1053714_1201.qxp 10/27/08 11:48 AM Page 841 12-1.qxd 3/12/09 18:09 Page 841 1053714_1201.qxp 10/27/08 11:48 AM Page 841 SECCIÓN FuncionesFunctions vectoriales 12.1 12.1Vector-Valued In los Exercises 75– determine the elinterval(s) on which the En ejercicios 7580, a 80, determinar (los) intervalo(s) en que function is continuous. lavector-valued función vectorial es continua. 11 80, determine the interval(s) on which the In Exercises 75– 75. rrstdt 5 t ti i1 jj 76. rrstdt 5 !t ti i1 !t t2 11jj 75. 76. vector-valued function is continuous. tt 77. rrstdt 5 t ti i1 arcsen arcsinttjtjj1 st t2 11d kk 77. 1arcsin 75. r t t i t 2t 78. rrstdt 5 2e 2e i ti1j ee2t jt j1 lnlnst t2 11d k76. k rt 78. 79. rrstdt 5 t i 79. 77. tantlt kee2t,t,t t2,2,tan 78. r t arcsin t j 2e t i e tj t ln t ti 80. rrstdt 5 1 k 80. k t 1j l 33t t 8,8,!t,t,! 1 k WRITING ABOUT CONCEPTS 79.Desarrollo 80. rt e t, t 2, de tan tconceptos rt 8, t, 3 t 81. Consider the vector-valued function 81. Considerar la función vectorial 2 BOUT CONCEPTS W R I rT It N G t A i t 3 j tk. rstd 5 t 2 ithe 1 svector-valued t 2 3dj 1 tk.function 81. Consider Write a vector-valued function s t that is the specified transformation r.j tk. sstd que sea la transformación t of3vectorial rDar t una t 2 i función especificada de r. (a) A vertical translation three units upward Write a vector-valued function s t that is the specified a) traslacióntranslation vertical tres unidades arriba of the (b)Una A horizontal two units inhacia the direction transformation of r. b) Una traslación negative x-axishorizontal dos unidades en dirección del (a) A vertical translation three units upward negativo translation five units in the direction of the (c)eje A xhorizontal (b) A horizontal translation two units in the direction of the c) Una traslación positive y-axishorizontal cinco unidades en dirección del negative x-axis eje y positivo 82. State the definition of continuity of a vector-valued (c) A horizontal translation five units in the direction of the 82. Dar la definición continuidad para una función vectorial. function. Give andeexample of a vector-valued function that positive y-axis Dar un ejemplo decontinuous una función is defined but not at tvectorial 2. que esté definida 82. State continuity of a vector-valued pero nothe seadefinition continua enoft 5 2. function. Give an example of a vector-valued function that is defined but not continuous at t 2. CAS 83. The outer edge of a playground slide is in the shape of a helix of CAS 83. El borde1.5 exterior deThe unaslide resbaladilla tiene of forma de unaand hélice de radius meters. has a height 2 meters makes 1.5 de radio. La resbaladilla una altura de a2 vectormetros onemetros complete revolution from toptiene to bottom. Find CAS 83. The outer edgerevolución offor a playground slidea is in thearriba shape of asystem helix ofto yvalued hace una completa desde hacia abajo. function the helix. Use computer algebra radius 1.5 meters. The slide has a height of 2 meters and makes Encontrar una función vectorial para la hélice. Usar un sistema graph your function. (There are many correct answers.) one complete frompara topgraficar to bottom. Find a (Existen vectoralgebraico por revolution computadora la función. the helix. Use a computer algebra system to muchas C valued A P S T function Orespuestas N E for correctas.) graph your function. (There are many correct answers.) 84. Which of the following vector-valued functions represent Para thediscusión same graph? CAPSTONE a) r tde las siguientes 3 cos t 1)i 5 sen t 2 j representa 4k 84. Which ¿Cuál vectoriales 84. of the following funciones vector-valued functions representla misma gráfica? b) same r t graph? 4i 3 cos t 1)j 5 sen t 2)k the a)c) rrt t b)d) rrt t 33cos i sent t 2 2j j 4k4k cost t 11)i 55sen 2t t 2 j2)k 4k 4i 3 cos32t cos t 1 i 1)j 5 sen 5 sen c) r t 3 cos t 1i 5 sen t 2j 4k 3 cos 2t 1 i 5 sen 2t 2 j 4k d) r t 85. Let r t and u t be vector-valued functions whose limits exist as t → c. Prove that lim rvectoriales t limfunctions u cuyos t . límites limr rrtsttdand 85. Sean y uuu cuanstdtt funciones Let be vector-valued whoseexisten limits exist t→c t→c t→c do Demostrar → c. c. Prove as tt → that que 86. Let r t and u t be vector-valued functions whose limits exist lim std c. 3 Prove ustdg 5 lim ustd. lím lím rstd 3 lím as tfr→ thatlim t→c t→c t→c t→c t→c t→c lim r vectoriales t lim ufunctions tcuyos . limr rrtsttdand y uuu límites cuansttdt funciones 86. Sean Let be vector-valued whoseexisten limits exist t→c t→c t→c do Demostrar → c. c. Prove as tt → that que 87. Prove that if r is a vector-valued function that is continuous at fr st d ?ru sist dgcontinuous 5 lim lím lím r st dat? c. lím c, then lim u st d. lim t→c t→c t→c t→c t→c t→c 88. Demostrar Verify that the si converse Exercisevectorial 87 is not true by en finding a 87. es unaoffunción c, enProve that ifque function thatcontinua is continuous at r is arvector-valued vector-valued function such that is continuous at but r r c r tonces continua enatc.c. then i r i es is continuous c, is not continuous at c. 88. Verify Verificar que el recíprocoofde lo que se en elbyejercicio that the converse Exercise 87 afirma is not true finding 87 a no es verdad encontrando una función vectorial r tal que i sea vector-valued function r such that r is continuous at ci rbut r continua en c peroatrc.no sea continua en c. is not continuous 841 841 841las Vector-Valued Functions In Exercises 89 and two particles travel along the space En los ejercicios 8912.1 y 90, dos partículas viajan a lo largo de curves de and ur(t) collision will occur at en theel point r tespacio t . yAu(t). curvas Una colisión ocurrirá punto of de intersection PP ifsiboth particles are at thePsame time. tiempo. Do the P at en intersección ambas partículas están al mismo In Exercises 89 partículas? and particles travel the space particles collide? Do 90, theirtwo paths intersect? ¿Colisionan las ¿Se intersecan sus along trayectorias? curves r t and u t . A collision will occur at the point of 2k 89. r t) t2Pi if both 9t particles 20)j tare intersection at P at the same time. Do the 2 paths intersect? particles collide? Do their u t) 3t 4 i t j 5t 4 k 2 3k 90. rr(t 89. t) t2tii t9tj t20)j t2k 2 uut)t) 3t 2t 4 i 3 i t j 8tj 5t 12t 4k 2k 90. r(t About ti t2j In t3Exercises k Think 91 yand 92, partículas two particles travel Para pensar It En los ejercicios 91 92, dos viajan a lo u t) 2t 3 i 12t 2k along the space curves r8tj t andr(t) u ty. u(t). largo de las curvas de espacio y u(t) intersecan, ¿colisionarán las partículas? 91. 91. Si If About will particles collide? rr(t) t) and Think Itu tse Inintersect, Exercises 91theand 92, two particles travel 92. lasspace partículas colisionan, ¿se sus u trayectorias r(t) y along curves andtheir r t do u t intersecan . 92. Si Ifthe the particles collide, paths r t) and t intersect? u(t)? 91. If rort) False? and u t intersect, will the particles collide? whether the True In Exercises 93–96, determine ¿Verdadero o falso? En los ejercicios 93 a 96,udeterminar si la 92. If the particles t) and t intersect? statement is true collide, or false.doIftheir it ispaths false,r explain why or give an declaración es verdadera o falsa. Si es falsa, explicar por qué o example that shows it is false. dar un que93–96, es falsa. True or ejemplo False? que In pruebe Exercises determine whether the 93. If and are first-degree polynomial functions, then an the f, g, h statement is true or false. If it is false, explain why or give 93. Si ƒ, g y h son funciones polinomiales de primer grado, entonces curve given by xit isffalse. t , y g t , and z h t is a line. example that shows la curva dada por x 5 f std, y 5 g(t) y z 5 hstd es una recta. 94. If the curve given by x f t , y g t , and z h t is a line, 93. and hdada are por first-degree the 94. IfSif,lag,curva y 5 g(t) y zfunctions, una recta, x 5 f std, polynomial 5 hstd es then then f, g, and h are first-degree polynomial functions of t. curve given is a line. t , y g polinomiales t , and z hde t primer entonces ƒ, gbyy xh sonf funciones grado de t. 95. Two particles travel along the space curves r t) and u t). The 94. thepartículas curve given by xa través f t ,dey las gcurvas t , anddez espacio h t is 95. IfDos viajan r(t)a yline, u(t). intersection of their paths depends only on the curves traced out then polynomial functions f, g, and h are La intersección defirst-degree sus trayectorias depende sólo deoflast. curvas by r t and u t), while collision depends on the parameterizations. trazadas por r(t) y u(t) en tanto la colisión depende de ulat). parame95. Two particles travel along the space curves The r t) and 96. trización. The vector-valued function r t t2 i t sin t j t cos t k intersection of their paths depends only on the curves traced out lies on the paraboloid x y2 2 z2. and u t),vectorial while collision sen 96. by Lar tfunción rstd 5depends t i 1 t on sinthe t j parameterizations. 1 t cos t k se encuentra en el paraboloide x 5 ry 2t 1 zt22. i t sin t j t cos t k 96. The vector-valued function Slies E on C TtheI O N P RxO J yE2 C zT2. paraboloid PROYECTO DE TRABAJO Witch of Agnesi SECTION PROJECT In Sectionde 3.5, you studied a famous curve called the Witch of Bruja Agnesi Agnesi. In project you will take a closer look at this function. Witch ofthis Agnesi En la sección 3.5 se estudió una curva famosa llamada bruja de Consider a circle of radius a centered on the y-axis at 0, a . Let En3.5, esteyou proyecto se profundiza sobre esta función. InAgnesi. studied a famous Witch and of be a point on the horizontal line y curve the origin, A Section 2a, letcalled O be the Considérese un círculo de radio acloser centrado enatelthis punto (0, a) del Agnesi. In this project you will take a look function. let B be the point where the segment OA intersects the circle. A eje y. Sea A un puntoofenradius la recta horizontal origen yB 5 2a, circle on ythe axisO atel 0, a centered a . Let pointConsider Witch of Agnesi if P lies ony-the horizontal line P is onathe el punto donde el segmento OA corta el círculo. Un punto P está be a point on on thethe horizontal let. O be the origin, anden Athrough 2a, A vertical line line ythrough B and la bruja si P se the encuentra en OA la recta horizontal travésAde let theAgnesi point where segment intersects the acircle. B be de (a)y Show that the point Através is traced out by the vector-valued function B en vertical de A. point is recta on the Witchaof Agnesi if P lies on the horizontal line P la through oncot vertical linedescrito A. la función vectorial 0 through rA B and 2a i A2aj, < <por a) Mostrar que elthe punto está (a) Show that the point is traced out by the function A is the that OA0 makes the positive xaxis. rwhere sud 5 2a cot angle u i 1 2aj, < u < with p vector-valued A 0 < out<by the vector-valued function 2a the cot point i B2aj, (b) rShow that is traced A u es el ángulo formado por OA con el eje x positivo. donde where isa the makes with positive rB < < vectorial . x- axis. sin 2punto i that 1OAdescrito cos 2 j, b) Mostrar que el angle Ba está por 0lathe función B is traced (b) that the point out byand the vector-valued function (c) Show Combine parts find rBsud 5 a the sin 2results u i 1 aof s1 2 cos(a) 2ud j, 0(b)< to u < p. the vectorsen function rvalued < < Use. a graphing a sin 2 ir a for 1 the cosWitch 2 j, of 0Agnesi. B c) Combinar los resultados losaincisos 1. a) y b) para hallar la funutility to graph this curvedefor (c) Combine the r( results of parts (a) and (b) Usar to find the vectorvectorial u) para de Agnesi. limla rbrujaand (d) ción Describe the limits lim r . una herramienta r valued function for the Witch of Agnesi. →0 → de graficación para representar esta curva para Use a 5 a1.graphing (e) utility Eliminate the this parameter to graph curve for a and1. determine the rectangular lím lim2 rsud. d) Describir límites lim rsud y Use lím equation los of the Witch of1Agnesi. p a graphing utility to graph u →0 r andu →lim r . (d) Describe the limits lim → la ecuación this function for a→0u 1y determinar and compare your graph with that e) Eliminar el parámetro rectangular de (e) Eliminate determine the rectangular inthe partparameter (c). Usar unaand laobtained bruja de Agnesi. herramienta de graficación para equation of the Witch of Agnesi. Use a graphing utility to graph representar esta función para a 5 1 y comparar la gráfica con la this function for a 1 and compare your graph with that obtenida en el inciso c). obtained in part (c). 12-2.qxd 3/12/09 842 18:10 Page 842 CAPÍTULO 12 Funciones vectoriales 12.2 Derivación e integración de funciones vectoriales n n Derivar una función vectorial. Integrar una función vectorial. Derivación de funciones vectoriales En las secciones 12.3 a 12.5 se estudian varias aplicaciones importantes que emplean cálculo de funciones vectoriales. Como preparación para ese estudio, esta sección está dedicada a las mecánicas de derivación e integración de funciones vectoriales. La definición de la derivada de una función vectorial es paralela a la dada para funciones reales. DEFINICIÓN DE LA DERIVADA DE UNA FUNCIÓN VECTORIAL La derivada de una función vectorial r se define como rst 1 Dtd 2 rstd Dt→0 Dt r9 std 5 lím lim para todo t para el cual existe el límite. Si r9(t) existe, entonces r es derivable en t. Si r9(t) existe para toda t en un intervalo abierto I, entonces r es derivable en el intervalo I. La derivabilidad de funciones vectoriales puede extenderse a intervalos cerrados considerando límites unilaterales. NOTA Además de la notación r9 std, otras notaciones para la derivada de una función vectorial son Dt frstdg, d frstdg, y dt dr . dt n La diferenciación de funciones vectoriales puede hacerse componente por componente. Para ver esto, considérese la función dada por r std 5 f stdi 1 gstd j. Aplicando la definición de derivada se obtiene lo siguiente. r9std 5 lim lím Dt→0 5 lím lim f st 1 Dtd i 1 gst 1 Dtd j 2 f stdi 2 g std j Dt 5 lim lím 53 f st 1 DtDtd 2 f std4i 1 3 gst 1 DtDtd 2 gstd4 j6 Dt→0 z r(t + ∆t) − r(t) Dt→0 r′(t) r(t + ∆t) 5 r(t) y x Figura 12.8 r st 1 Dtd 2 r std Dt f st 1 Dtd 2 f std gst 1 Dtd 2 gstd lim 3 lím 3 46i 1 5 lim 46 j 5 lím Dt Dt Dt→0 Dt→0 5 f9 std i 1 g9std j Este importante resultado se enuncia en el teorema de la página siguiente. Nótese que la derivada de la función vectorial r es también una función vectorial. En la figura 12.8 se ve que r9 std es un vector tangente a la curva dada por rstd y que apunta en la dirección de los valores crecientes de t. 12-2.qxd 3/12/09 18:10 Page 843 SECCIÓN 12.2 Derivación e integración de funciones vectoriales 843 TEOREMA 12.1 DERIVACIÓN DE FUNCIONES VECTORIALES 1. Si rstd 5 f std i 1 gstd j, donde ƒ y g son funciones derivables de t, entonces r9 std 5 f9std i 1 g9 std j. Plano. 2. Si rstd 5 f std i 1 gstd j 1 h stdk, donde ƒ, g y h son funciones derivables de t, entonces r9 std 5 f9std i 1 g9 std j 1 h9 stdk. y Espacio. r(t) = ti + (t 2 + 2)j EJEMPLO 1 6 Para la función vectorial dada por r(t) 1 ti 1 (t2 1 2)j, encontrar r9(t). Entonces bosquejar la curva plana representada por r(t) y las gráficas de r(1) y r9(1). 5 r′(1) 4 (1, 3) 3 Derivación de funciones vectoriales Solución Derivar cada una de las componentes base para obtener r(1) r9(t) 5 i 1 2tj Derivada. 1 x −3 −2 −1 Figura 12.9 1 2 3 Del vector de posición r(t), se pueden escribir las ecuaciones paramétricas x 5 t y y 5 t2 1 2. La ecuación rectangular correspondiente es y 5 x2 1 2. Cuando t 5 1, r(1) 5 i 1 3j y r9(1) 5 i 1 2j. En la figura 12.9, r(1) se dibuja iniciando en el origen, y r9(1) se dibuja en el punto final de r(1). Derivadas de orden superior de funciones vectoriales se obtienen por derivación sucesiva de cada una de las funciones componentes. EJEMPLO 2 Derivadas de orden superior Para la función vectorial dada por rstd 5 cos ti 1 sen sin tj 1 2tk, hallar a) r9 std c) r9 std ? r0 std b) r0 std d) r9 std 3 r0 std Solución a) r9 std 5 2sin sen ti 1 cos tj 1 2k b) r0 std 5 2cos ti 2 sen sin tj 1 0k 5 2cos ti 2 sen sin tj || Primera derivada. Segunda derivada. || c) r9std ? r0 std 5 sen sin t cos t 2 sen sin t cos t 5 0 i j k d) r9 std 3 r0 std 5 2sin sen t cos t 2 2cos t 2sin sen t 0 cos t 2 2sin sen t 5 i2 2sin 0 2cos t sen t 5 2 sen sin ti 2 2 cos tj 1 k | Producto escalar. Producto vectorial. | | | sen t 2 2sin cos t j1 k 0 2cos t 2sin sen t En el inciso c) nótese que el producto escalar es una función real, no una función vectorial. 12-2.qxd 25/2/10 844 13:52 Página 844 CAPÍTULO 12 Funciones vectoriales La parametrización de la curva representada por la función vectorial r共t兲 ⫽ f 共t兲 i ⫹ g共t兲j ⫹ h 共t兲k es suave en un intervalo abierto I si f⬘, g⬘ ,y h⬘ son continuas en I y r⬘ 共t兲 ⫽ 0 para todo valor de t en el intervalo I. EJEMPLO 3 Intervalos en los que una curva es suave Hallar los intervalos en los que la epicicloide C dada por r共t兲 ⫽ 共5 cos t ⫺ cos 5t兲i ⫹ 共5 sen sin t ⫺ sen sin 5t兲j, 0 ≤ t ≤ 2 y 6 4 es suave. t=π 2 Solución La derivada de r es 2 t=0 t=π −6 −4 x −2 2 −2 −4 4 t = 2π 6 t = 3π 2 −6 r(t) = (5 cos t − cos 5t)i + (5 sen t − sen 5t)j La epicicloide no es suave en los puntos en los que corta los ejes Figura 12.10 sin t ⫹ 5 sen sin 5t兲i ⫹ 共5 cos t ⫺ 5 cos 5t兲j. r⬘ 共t兲 ⫽ 共⫺5 sen En el intervalo 关0, 2兴, los únicos valores de t para los cuales r⬘ 共t兲 ⫽ 0i ⫹ 0j son t ⫽ 0, 兾2, , 3兾2, y 2. Por consiguiente, se concluye que C es suave en los intervalos 冢0, 2 冣, 冢2 , 冣, 冢, 32冣, y 冢32, 2冣 como se muestra en la figura 12.10. NOTA En la figura 12.10, nótese que la curva no es suave en los puntos en los que tiene cambios abruptos de dirección. Tales puntos se llaman cúspides o nodos. I La mayoría de las reglas de derivación del capítulo 2 tienen sus análogas para funciones vectoriales, y varias de ellas se dan en el teorema siguiente. Nótese que el teorema contiene tres versiones de “reglas del producto”. La propiedad 3 da la derivada del producto de una función real w y por una función vectorial r, la propiedad 4 da la derivada del producto escalar de dos funciones vectoriales y la propiedad 5 da la derivada del producto vectorial de dos funciones vectoriales (en el espacio). Nótese que la propiedad 5 sólo se aplica a funciones vectoriales tridimensionales, porque el producto vectorial no está definido para vectores bidimensionales. TEOREMA 12.2 PROPIEDADES DE LA DERIVADA Sean r y u funciones vectoriales derivables de t, w una función real derivable de t y c un escalar. 1. Dt cr t cr t 2. Dt r t ± u t r t ±u t 3. Dt w t r t wtr t w trt 4. 5. 6. 7. Dt Dt Dt Si r r r r t ut rt u t r t ut t ut r t) u t r t ut w t r w t w t t rt c, entonces r t r t 0. 12-2.qxd 3/12/09 18:10 Page 845 SECCIÓN 12.2 DEMOSTRACIÓN Derivación e integración de funciones vectoriales 845 Para demostrar la propiedad 4, sea rstd 5 f1stdi 1 g1stdj y ustd 5 f2stdi 1 g2stdj donde f1, f2, g1, y g2 son funciones derivables de t. Entonces, rstd ? ustd 5 f1std f2std 1 g1stdg2std EXPLORACIÓN Sea r(t) 5 cos ti 1 sen tj. Dibujar la gráfica de r std. Explicar por qué la gráfica es un círculo de radio 1 centrado en el origen. Calcular rspy4d y r9 spy4d. Colocar el vector r9 spy4d de manera que su punto inicial esté en el punto final de rspy4d. ¿Qué se observa? Mostrar que r std ? r std es constante y que rstd ? r9std 5 0 para todo t. ¿Qué relación tiene este ejemplo con la propiedad 7 del teorema 12.2? y se sigue que Dt frstd ? ustdg 5 f1std f29 std 1 f19 std f2std 1 g1std g29 std 1 g19 std g2std 5 f f1st)f29 std 1 g1std g29 stdg 1 f f19 std f2std 1 g19 std g2stdg 5 rstd ? u9 std 1 r9 std ? ustd. Las demostraciones de las otras propiedades se dejan como ejercicios (ver ejercicios 77 a 81 y ejercicio 84). EJEMPLO 4 Aplicación de las propiedades de la derivada Para las funciones vectoriales rstd 5 1 i 2 j 1 ln tk y ustd 5 t 2 i 2 2tj 1 k t hallar a) Dt frstd ? ustdg y b) Dt fustd 3 u9 stdg. Solución 1 1 a) Como r9 std 5 2 2 i 1 k y u9 std 5 2ti 2 2j, se tiene t t Dt frstd ? ustdg 5 rstd ? u9 std 1 r9 std ? ustd 1 5 i 2 j 1 ln tk ? s2ti 2 2jd t 1 1 1 2 2 i 1 k ? st 2 i 2 2t j 1 kd t t 1 5 2 1 2 1 s21d 1 t 1 531 . t 1 1 2 2 b) Como u9 std 5 2ti 2 2 j y u0 std 5 2i, se tiene || | || Dt fustd 3 u9 stdg 5 fustd 3 u0 stdg 1 fu9 std 3 u9 stdg i j k 5 t 2 22t 1 10 2 0 0 22t 1 t2 1 t 2 22t 5 i2 j1 k 0 0 2 0 2 0 5 0i 2 s22dj 1 4tk | | | 5 2j 1 4tk. NOTA Hacer de nuevo los incisos a) y b) del ejemplo 4 pero formando primero los productos escalar y vectorial y derivando después para comprobar que se obtienen los mismos resultados. n 12-2.qxd 3/12/09 846 18:10 Page 846 CAPÍTULO 12 Funciones vectoriales Integración de funciones vectoriales La siguiente definición es una consecuencia lógica de la definición de la derivada de una función vectorial. DEFINICIÓN DE LA INTEGRAL DE UNA FUNCIÓN VECTORIAL 1. Si rstd 5 f stdi 1 gstdj, donde f y g son continuas en fa, bg, entonces la integral indefinida (o antiderivada) de r es E rstd dt 5 3Ef std dt4i 1 3Egstd dt4 j Plano. y su integral definida en el intervalo a ≤ t ≤ b es E b 3E 4 3E gstd dt4 j. b rstd dt 5 a b f std dt i 1 a a 2. Si rstd 5 f stdi 1 gstdj 1 hstdk, donde f, g y h son continuas en fa, bg, entonces la integral indefinida (o antiderivada) de r es E rstd dt 5 3Ef std dt4i 1 3Egstd dt4 j 1 3Eh std dt4k Espacio. y su integral definida en el intervalo a ≤ t ≤ b es E b 3E b rstd dt 5 a a 3E b 4 f std dt i 1 a 4 g std dt j 1 3E b 4 h std dt k. a La antiderivada de una función vectorial es una familia de funciones vectoriales que difieren entre sí en un vector constante C. Por ejemplo, si rstd es una función vectorial tridimensional, entonces al hallar la integral indefinida erstd dt, se obtienen tres constantes de integración E f std dt 5 Fstd 1 C1, E g std dt 5 G std 1 C2, E h std dt 5 H std 1 C3 donde F9 std 5 f std, G9 std 5 g std, y H9 std 5 h std. Estas tres constantes escalares forman un vector como constante de integración, E rstd dt 5 fFstd 1 C1gi 1 fG std 1 C2g j 1 fH std 1 C3gk 5 fFstdi 1 G std j 1 H stdkg 1 fC1i 1 C2 j 1 C3kg 5 Rstd 1 C donde R9 std 5 rstd. EJEMPLO 5 Integración de una función vectorial Hallar la integral indefinida E st i 1 3jd dt. Solución Integrando componente por componente se obtiene E st i 1 3jd dt 5 t2 i 1 3tj 1 C. 2 12-2.qxd 25/2/10 13:55 Página 847 SECCIÓN 12.2 Derivación e integración de funciones vectoriales 847 El ejemplo 6 muestra cómo evaluar la integral definida de una función vectorial. Integral definida de una función vectorial EJEMPLO 6 Evaluar la integral 冕 1 冕冢 1 r共t兲 dt ⫽ 0 3 ti ⫹ 冪 0 冣 1 j ⫹ e⫺t k dt. t⫹1 Solución 冕 1 冢冕 冣 冢冕 1 r 共t兲 dt ⫽ 0 0 ⫽ 冣 冢冕 e dt冣k 1 1 dt j ⫹ t⫹1 t1兾3 dt i ⫹ 0 冤 冢34冣 t 冥 1 4兾3 0 冤 ⱍ ⫺t 0 ⱍ冥 0 j ⫹ 冤 ⫺e⫺t冥 0 k 1 i ⫹ ln t ⫹ 1 冢 1 1 冣 3 1 ⫽ i ⫹ 共ln 2兲 j ⫹ 1 ⫺ k 4 e Como ocurre con las funciones reales, se puede reducir la familia de primitivas de una función vectorial r⬘ a una sola primitiva imponiendo una condición inicial a la función vectorial r., como muestra el ejemplo siguiente. La primitiva de una función vectorial EJEMPLO 7 Hallar la primitiva de r⬘ 共t兲 ⫽ cos 2ti ⫺ 2 sen sin tj ⫹ 1 k 1 ⫹ t2 3i ⫺ 2j ⫹ k. que satisface la condición inicial r共0兲 ⫽ 3i Solución r共t兲 ⫽ ⫽ ⫽ 冕 冢冕 r⬘ 共t兲 dt 1 sin t dt冣 j ⫹ 冢冕 dt k 冣 冢冕 ⫺2 sen 1⫹t 冣 cos 2t dt i ⫹ 2 sin 2t ⫹ C 冣i ⫹ 共2 cos t ⫹ C 兲j ⫹ 共arctan t ⫹ C 兲k 冢12 sen 1 2 3 Haciendo t ⫽ 0 usando el hecho que r共0兲 ⫽ 3i ⫺ 2j ⫹ k, se tiene r共0兲 ⫽ 共0 ⫹ C1兲i ⫹ 共2 ⫹ C2兲j ⫹ 共0 ⫹ C3兲k ⫽ 3i ⫹ 共⫺2兲j ⫹ k. Igualando los componentes correspondientes se obtiene C1 ⫽ 3, 2 ⫹ C2 ⫽ ⫺2, y C3 ⫽ 1. Por tanto, la primitiva que satisface la condición inicial dada es r共t兲 ⫽ sin 2t ⫹ 3冣i ⫹ 共2 cos t ⫺ 4兲j ⫹ 共arctan t ⫹ 1兲k. 冢12 sen 1053714_1202.qxp 10/27/08 11:48 AM Page 848 1053714_1202.qxp 10/27/08 11:48 AM Page 848 12-2.qxd 3/12/09 18:10 11:48 Page 848AM 1053714_1202.qxp 10/27/08 11:48 Page 1053714_1202.qxp 10/27/08 AM Page 848848 1053714_1202.qxp 10/27/08 11:48 AM Page 848 848 848 848 848 848848 848 Chapter CAPÍTULO FuncionesFunctions vectoriales Chapter1212 12Vector-Valued Vector-Valued Functions Chapter 12 Vector-Valued Functions Chapter 12 Vector-Valued Functions Chapter 12 Vector-Valued Functions Chapter 12 Vector-Valued Functions Exercises forfor worked-out solutions to to odd-numbered exercises. 12.2 Exercises www.CalcChat.com worked-out solutions odd-numbered exercises. 12.2 Ejercicios SeeSeeSeeSeewww.CalcChat.com 12.2 Exercises www.CalcChat.com for worked-out solutions to odd-numbered exercises. 12.2Exercises Exercises www.CalcChat.com for worked-out solutions to odd-numbered 12.2 See www.CalcChat.com for worked-out solutions to odd-numbered exercises. 12.2 See www.CalcChat.com for worked-out solutions to odd-numbered exercises. exercises. InInExercises 1–8, sketch the curve represented bybythe Exercises 1–8, theplane plane curve represented the En los ejercicios 1 asketch 8, dibujar la curva plana representada por vector-valued function, and sketch the vectors and for r t r tby In Exercises 1–8, sketch the plane curve represented the In Exercises 1–8, sketch the plane curve represented the 0by In la Exercises 1–8, sketch the plane represented the vector-valued function, and sketch the vectors r t In Exercises 1–8, sketch the plane curve by the función vectorial y dibujar los curve vectores para el rrepresented xt0rc0 ty0 rand 9 xtby c 0 for 0 the given value of Position the vectors such that the initial t . vector-valued function, and sketch the vectors and for r t r t vector-valued function, and sketch the vectors and for r t r t 0 vector-valued function, and sketch the vectors and for r t r t 0 0 0 inithe given of t0. Position such vector-valued and thedevectors and t00that r0 tinitial 0r que valor dado value de tfunction, los sketch vectores manera el the punto 0. Colocar 0 for of isof the and the initial point ofthat isisatinitial the r rt0value rthat thegiven given value ofPosition Position the vectors such the initial t.0.origin the of Position vectors such ttel0origin thepoint given the vectors such that initial ten point isatat and the initial point at rxtt00ctthe the given of Position the vectors such that the initial 0.the cial deof y el punto inicial deof enthe el rvalue xt0value ct0esté r9the 0esté 0. origen terminal point What isisthe relationship between t0 torigin . origin rat tthe point of isof atrthe the and the initial point oftbetween isthe at ris t0atis ris t0atis point of is at the origin and the initial point of is at r t r t 0the point of the origin and the initial point of r t r 0 0 terminal point of What the relationship r . r t0 point of at and the initial point of r t r t 0 0 punto final0de r xt0c. ¿Qué relación hay entre r9 xt0c y la0 curva?the 0 and the curve? terminal point What therelationship relationship between terminal point isisthe between terminal point of rof is the relationship between t0rrr. ttWhat r tr0 r tt00t0 0t0.. .What and the curve? terminal point ofof 0 What is the relationship between r and the curve? the curve? andand the curve? 2 and curve? 1.1.r the rt t t ti2 i tj,tj, t0 t0 2 2 2 1. r t i 2tj, tj, 1.trrrt tt t ititt 22t 2ii tj, 1. 2.r1. t t0t02 22 2. r t ti t tj, t2 0 1t10j, j, t20 t0 1 1 2 2 2 2. r2. 2.2.t rrrtt tti ti titit 1tt2t1 j,111j, j,tj,0 tt0t01 111 3.3.r rt t t 2ti2 i 1j, j, t0 t 2 02 1 t 1 11t j, t0 2 22 3. r3. 3.3.t rrrtt tt i tt 2t ii it j, t tj, j,t0 tt0 02 222 4.4.r rt t 1 1 t itt i t 3tj,30j, t0 t 1 1 0 3 3 3j, t t 4. r4. 4.4.t rrrtt t 1 111t i tt tii ti j, tt 3tj, j,t0 t00 01 111 5.5.r rt t cos costi ti sen sentj,tj, t0 t0 2 5. r t cos ti sentj, r t cos ti sen 5. r5. t0 tt00t0 22 t cos ti sen tj, 5. r t cos ti sen tj,tj, 2 22 6.6.r rt) t) 3 3sen senti ti 4 4cos costj,tj, t0 t0 2 costj, 333sen 444cos 6. r6. t tt0t0 2 tisenti tj, 6.6.t)rrrt) t)t)3 sen sen titi4 cos cos tj,tj, 7.7.r rt t et,ete,2te2t, , t0 t 0 0 0 0 2 222 0 2t 7.t rrt t et, ee2tttet,t,e, 2t et 2tt, , t t0 00 7. 8.r7. 7. 8.rrrt tt eee,, ete, e,t,0, tt000t00 000 t tt t t t 8. r8. 8.8.t rrrtt t e ,eeee t,,,,eete t,,0, tt00t00 000 InInExercises 9 9and 10, (a)(a)sketch the curve represented byby and thespace En Exercises los ejercicios 9 y10, 10, a)sketch dibujar laspace curvacurve en elrepresented espacio reprevector-valued function, and (b) sketch the vectors and r t In Exercises 9 and 10, (a) sketch the space curve represented In Exercises 9 and 10, (a) sketch the space curve represented by 0 Inthe Exercises 9 and 10, (a) sketch the space curve represented by theExercises vector-valued function, and the (b) sketch thelosvectors r t0r xtand In 9 and 10, (a) sketch curve represented sentada por la función vectorial, y b)space dibujar vectores y cby 0by for the given value ofand t0 t vector-valued t0.tand the vector-valued function, and (b)sketch sketch thevectors vectors and rand t0 and the vector-valued function, and (b) sketch the vectors and r t therrthe function, (b) sketch the vectors r t 0 for the given value of r9vector-valued . function, (b) the r t 0 xt00c para el valor dado de t00. 0 forthe thegiven given value oft t..0. value tt0t0 for the given value of tof r trr0 r for 0. t0 0 for the given value of 0 33 3p 9.9.r rt t 2 2cos ti 2 sin tj costiti1 22sen sintjtj1tk, tk, t0t0t035 233 9. r std 5 2 cos sin tk, 9. t r t 2 cos ti 2 sin tj tk, 9. t r t 2 cos ti 2 sin tj tk, 9. r9.t r t 2 cos t t0 0 322 ti 2 ti 2 sin tj tj tk, tk, 2 cos 32 sin 10. t0 t 2 2 0 0 2 222 33 10.rrrtstdt 5tititi1t ttj22jj12k, k, k, t 5 2 10. 223 00 2 2 23 3 k, t t 10. 10. r10.t rrrtt tti ti 2 t0 t0 02 2 10. titit j tt 2tjj 2j k, 322k, k, 22 0 InInExercises 11–22, find r t Exercises 11–22, find r .t . En los ejercicios 11 afind 22, Exercises 11–22, find In 11–22, In Exercises 11–22, find r trrhallar .r tt t.. . r9 xtc. 3i 11–22, InInExercises Exercises find 11. 12. t it i 1 1 t3 t3j j r t t 3tj 3 11. r t 12.r rt t t i 3tj 3 3 3 3 i t,3tj 3tj 11. 12. 3tj t tii i1t, 1121t3sen 11.13. 12.14. r12.t rrt t t it cos r11.t rrt tt i t3ti 3tj jtt33t tjj j 11. 12. 13.rrrt tt 2t 2icos 14.rrrt tt cos t,5 5sen sent t tt cos t, 2 sen t 3k t,j552 5sen 13. 22cos cos t,2sen sen t3t 14. 14. tt tcos 22sen sen 13.15. r13.trrrtrtt t 26ti cos t,cos 5 t, tsen r14.t rrrtt t t cos t,cost, 2t, sen tsentt t 7t t 13. 14. 2 t cos t, 2 15. r t 6ti 7t j t k 3k 6ti7t 2j7t 6ti 7t7t22jj2tj3 kttt233tk 15. 15. r15. t rrrtt t6ti16ti 2 15. 1i 16tj tkk 16. r t 2 16. r t 1 t 11 i 16tjt 2 2t 2t 2k i 16tj 16tj kt2 k 16. kk 16. 16. r16.t rrrtt t i 1ttii 16tj t a ttcos 3 t316tj 2 2223 tj 17. r t i 17. r t a cos t i a asen sen3 tj k k 3 tj 2 33 3 cos 3 sen 17. aacos at ajsen tj k kk 17.18. r17.t rrt ta cos tj 33 tj t titi 3i tt iittai2tsen 2a 17. sen 18.rrrt tt 4a4cos t j ln lnt tk2kk 2 2 2 2 2 lnt 2tkk j tln 18. tt tjjtln 18.19. r18.t rrt t4 4t4ti t ti ti2 tt 2tt j 5te k 18. 19.rrrt tt e4e ittii 4j4j 5tekt kln t k ti tk t t t t 3 19. r t e 4j 5te 19. 4j 5te 3t 5te k 19.20. r t r t e ei t ii 4j3t,4j k tk 19. 20.rrrt tt te ,t3cos , cos 3t,sen sen5te 3t 3 3 t3 r t t 20. , cos 3t, sen 3t 20. r t , cos 3t, sen 3t 3 r t t 20.21. , cos 3t, sen 3t t, t,t3t, cos t, t,t3tt 20. cos sen 21.rrrt tt t tsen t ,sen t cos tcos 21. tt tsen sen t,t,t,ttarccos cos t,t,ttt,t 0 21.22. r21.trrrtrtt t t sen t,sen t cos t,cos t t, arcsen 21. t, arcsen t, arccos t, 0 22. r t arcsen arccos arcsen t,t,arccos arccos t,t,000 r22.t rrrtt t arcsen t, arccos t, 0 t, 22. 22. arcsen t, 22. InInExercises Exercises23–30, 23–30,find find(a)(a)r rt ,t (b) , (b)r r t ,t and , and(c)(c)r rt t r r t .t . In Exercises 23–30, find (a) (b) r t , r t r. 0(t). In Exercises 23–30, find (a) (b) and r t , r t , tt t.. . In Exercises 23–30, find (a) (b) and (c) r t , r t , rt ?trrr0 1 23 3 23–30, 2 afind In Exercises and (c) r t a) , (b) r b) t , ,r0 0and r99(t), (t) (c) yr(c) c)trrrr99tt(t) En los ejercicios 30, (a) hallar 23. 23.r rt t t ti 3i 2t1121tj2 j 3 2 23. 23.24. r23.t rrt tt 3i t233ti 1i t 2 j1t 22tj j 2 23. 24.rrrt tt tt ti22 t 22itt2 ij t t 2 t jt j 2 2 24. t 22t 2t j t tj j r24.t rrt t t 2 tt 2t t ititt tii it42 sen 24.25. 24. 25.rrrt tt 4 4cos cos ti 4tsentjtjt j sentjtj 25. 44cos 44sen 25.26. r25.t rrt t4 cos ticostiti4 sen tj 25. cos sen cost itit i 343sen 26.rrrt tt 848cos sentjtjtj 1 828cos sentjtj 26. 313sen r26.t rrt t8 cos i tttjiit 3i sen 26.27. 1 it2cos 13tj 26. i tj 36t1sen tk3ktj 27.rrrt tt 2 81t21tcos 1 2 1 2t 2 i 1 3 1613t 3k r t tj 27. 27. r t r t t i t 2 i tj tj t k t 3k 27.28. 27. 28.rrrt tt 2 ti22ti2t i 2t2ttj 6 3 3j66t6j k 3t3t 5 5k k 2t3 j 333t, 5k k j j3t 3t 28. r28.t rrt tti ti 2tt 2t 28.29. 28. titicos 3tt3t5t kt55cos t2t t sen t senj t,sen sen t kcost, t,t t 29.rrrt tt cos t 2 r t cos t t sen t, sen t t cos 29. tt sen t, tt cos 29. r t r t coscos t t t sen t tt t cos t, t t, 29.30. tt,tsen 29. sen t, sen sen cos t,t,tt t 30.rrrt tt ecos e , tt,t t, 2tan , tan t 2 t 2 ,tt 2t,, ,tan 30. 30. r30.t rrrtt t e t,eete2t,,, tan ttantt t 30. tan InInExercises 3131and 32, a avector-valued function and itsitsgraph and graph EnExercises los ejercicios 3132, y 32vector-valued se dan una function función and vectorial y su are given. The graph also shows the unit vectors rgraph t0 t r t In Exercises 31 and 32, a vector-valued function and In Exercises 31 and 32, a vector-valued function and its In Exercises 31The and 32, 32, atambién vector-valued andand its are given.La graph also shows thefunction unit rgraph r 0graph t0/its In Exercises 31 and a vector-valued function its graph gráfica. gráfica muestra losvectors vectores unitarios / 0 and Find these two unit vectors and t0 t graph . graph t / rThe arergiven. given. also shows the unit vectors rthem are the unit vectors rr0 unitatt0t0 are graph shows the unit vectors ridentify trr0 r/ tt00rt0// t/them and these unit vectors and identify rThe are also shows the unit vectors estos dos vectores rgiven. 9 xt0given. cr/ 0 tThe r09 x/tThe r.0Find xalso t0c/also r0 xshows t0ctwo . Hallar 0ygraph 0 0c on and Find these two unit vectors and identify them t0/ /trr .t0tFind and these vectors identify them ttgraph. and these twotwo unitunit vectors andand identify them rthe trr0ergraph. 0 . .Find 0r on the /identificarlos and these two unit vectors and identify them rios en la gráfica. 0 / r0 t0 . Find onthe thegraph. graph. on the graph. on on the graph. 1 2 31. 2 4 1 31.r rt t cos cos t it i sen sen t jt j t tk, k, t0 t0 2 1 1141 3 cos 122t k, 2t ti sen t t j t tj tj 2 k, 31. t r t cos i sen k, 31. t r t sen t 31.32. t r t cos t i 3 1 0 ti ti t ttj2ij esen 31. 32.rrrt tt 2 cos e kt ,k ,t tj0 t t4 k,0 t00 4 44 4 3 3323 ti2 z 2t 2j t e t t k , t01 1141 z 32. r t 32. ti t j tt 2zjj e eek ,t k k t,,0 tt0 04 4 4 32. 32. r t rr tt 2 ti 2 2ti z || || || 2 1 1 0 zz z z 1 || 1 11 1 1 1 1 1 x Figure 1 for 31 1 1 1 1 1 y y y yy y 4 z zz z 2 2 2 2 2 2 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 2 1 12 1 1 2 2 2 2 x 2 2 y 2 2y 2 2 y y yy 1 Figure Figure for 31 Figurefor for3232 Figura para Figura para Figure for31 3131 Figure for32 3232 Figure for 31 Figure for 32 Figure for for 31 Figure for for 32 Figure Figure InInExercises 33–42, find the open interval(s) on which the Exercises 33–42, the openelinterval(s) on which thecurve curve En los ejercicios 33 find afind 42,the hallar (los) intervalo(s) abierto(s) en byby the vector-valued function is smooth. InExercises Exercises 33–42, find the open interval(s) onwhich which thecurve curve In Exercises 33–42, open interval(s) on which the curve Ingiven Exercises 33–42, findfind thethe open interval(s) on which thethe curve given the vector-valued function is smooth. In 33–42, open interval(s) on que la curva dada por la función vectorial es suave. given by the vector-valued function is smooth. given by the vector-valued function is smooth. given by by thethe vector-valued function is smooth. given vector-valued function is smooth. 11 2 3 33. 34. 33.r rt st d 5t ti2 i 1t tj3j 34.r rt st d 51t 11 i i 13tj3tj 2 3 1i 1 i 3tj t2 i 3tj 3tj 34. 33. 33. r33.t rrrtt tt 2 i tt 22t ii ti3j3 tt 33tjj j r34.t rrrtt t 3 j34. 34. 33. 35. r 2 cos 33 i i 3 3sinsin 3 t tt 1t 111i 3tj 35. cos3 3u i 1 33sen sin333ujj 35. rr sud 5 22 3cos cos 35. 222cos 333sin jj j 35.36. r35.rrrr 2 cos i3 ii 3i i sin j3 cos sin 1sin j 35. cos sin 36. sen sin udii 1 s11 2 cos cos udjj 36. rr sud 5 su 1 sin 36. r sin i 1 cos 36. r sin i 1 cos 36.37. r rr sin2sin i i i 1 11coscos sin 2 jcosjj j j j 36. 37. sen udii 1 s11 2 22 cos sin cos udj 37. rr sud 5 su 2 22 sin 2 sin cos 222sin 222cos 37. 37. r37. rrr 2 sin i 2tii i122 1112 cos j jj j 1 2t2t 37. sin cos 2t 38. r rt t t t 1 1i i 1j j t 2tk2k rt 2t3 i i 2 2t232 j j 39. 38. 39. 2t 2t 8 t t i 1 j 38. rr sttd 582t8 2t 2t 2 3 3 1 t 11 1 tt 33ii i 2t 882t 1 tt 33jj j39. 39. 38. 39. k2k 38. 38. r39.t rrrtt t t tt 1t i 111ii i j 1ttjj tj2k tt 22tk r38.t rrrtt t t 882t 3 i t3 3 j t3 t 8 t t 8 tt tk 8 3 3 8 t t tan 8 t 40. 41. r t e r t ti 3tj i e j 3tk t t 8 t 8 t 40. r t 41. r t e i e j 1 3tk 2 tit 3tj2t tan tk t j3tk 2 t 1k i 23tj e tan j1 3tk 39. 40. 3tj tan j 3tk 40. 41. tieti3tj tan tktk jt 3tk 40.42. 41. r40. t rrrst ttdet5 r41.t rrrrstttdtti5 ti tk i estteti ei2 t 1ej editt21 1 41. 40. 3tj tan tk 42.rrrt t t e ti it i e t jt 2 t13tk 1j j 4tk tk 41 1 2 1 2 2 t 2t1 j 11j j tk 1 tk 42. tk r t t i r t t i 42. 42. r t t i t 4 41. rr sttd 5 ti t2i 3tj t1 tan 42. 1 tk j 4 44tk InInExercises 4343and 44, use the properties of the derivative to 1 properties of the derivative to Exercises and use the 2 44, ! r s t d 5 t i 1 s t 2 1 d j 1 42. 4 tk the following. In Exercises 43 and 44, use the properties thederivative derivative In Exercises 43 and 44, use the of Infind Exercises 43 and 44, use the properties of the derivative to to find the following. In Exercises 43 and 44, use the properties properties ofofthe the derivative toto find the following. the following. findfind the following. Enr los usar las propiedades derivada find the ejercicios following. 43(b)y 44, (a) (c)(c)DtD[r[rt tdeula (a) (b)r rt t rtencontrar t ut ]t ] t para lo siguiente. (a) (b) (c) r t r t D [ r t u t] ] (a) (b) (c) r t r t D [ r t u t (a)(d) (c) (c) r t t t r t D [rt [ttt[rtr ttu],t u] tt > u ut ]t(b) (a) (b) (d)DrtD[3r (e)DrtD[rt [trt t u ut ]t ] (f) (f)tDD ] (e) Dt [ r t ], t] >0 0 tt[c3r t a) b) c) r 9 x r 0 x t c D [ r(t c u x t c] (d) (e) DD[r[rt t u]utt t]](f) [3rtt tu t u ] (f) D ]] ] (e) (d) (d) D [3r D(f)[ D rDt [t [r]r,t t?]t,],> t 0t>>00 t [[tt3r 2Dt [rDttt[tr t u t u (d) DtD u]utt t(e) tr t 3r ti 43. 3tj t(e) k,2 u t 4ti t 2(f) j 2t Dttt3[tk3r t ], t > 0 43. d) Drt [t3rxtc ti2 ux3tj tc] e)t2 2k,Dt [ruxtct 3 u4ti x tc] t2f)2j Dt [t3 3krxt) ] , t > 0 3tjt 2k,t 2tk,k, t4ti 4ti 4tit 2j t 2tj tj3k t 3tkk 43. uutttk, 43.44. r43.t rrt tti titi3tj 3tj u tu 43. 44.rrrt tt tititi 23tj 2sinsintjtjt 2k,2 2cos cos tk, 4ti t 2j t 3k 43. ti 1 23tj 1tjtjt2 k, ucos stdtk, 5 4ti 1 t j 1 t k tk, 222cos 44. 44. r44.t rrrrsttttdti51ti tjsin tk, 44. ti1ti2 sin 22sin sin tj cos cos tk, sin cos tk, 44.u urt std15t 1tii1 i1 222sin sen sintjtjtj1 222cos costk tk 1t costk 222sin 222cos u tu tjsintj tk uutt t t i t1tii 2i sin sin tjtj2 cos cos tktk uExercises std 5 t i 14545 2 sen sin tj 146, 246, cosfind tk InIn Exercises and t t u ut ]t ] and t [r[r and find (a) (a) DD and t t in two different ways. r t u t D [ ] [ In Exercises 45 and 46, find (a) and D [ ]] ] and In Exercises 45 and 46, find (a) D r t [ In(b) Exercises 45 and 46, find (a) D r t t t (b) DExercises ways.(a) t Dt [rrttut t u u t 45 ] in two In anddifferent 46, find and u]utt tand t [r t a)ways. D [rxtc ? uxtc] y b) Dt[rxtc 3 uxtc] En los ejercicios 45 ytwo 46,different hallar (b) in two different ways. r t u t D [ ] (b) in two different ways. r t u t D [ ] t (b)(i) in two different ways. r t u t D [ ] t t Find the product first, then differentiate. (b) in r t u t D [ ] t t (i) Find the product first, then differentiate. en dos diferentes formas. (i)Apply Find theproduct product first, then differentiate. Find first, then differentiate. (i)(ii)(i) Find thethe product first, then differentiate. the properties ofofTheorem 12.2. (i) Find the product first, then differentiate. (ii) Apply the properties Theorem 12.2. i) Hallar primero el producto y luego derivar. (ii) Apply the properties of Theorem 12.2. Apply the properties of Theorem 12.2. (ii) (ii) Apply the properties of Theorem 12.2. 2 3 4 12.2. (ii) Apply the properties of Theorem 45. r t ti 2t j t k, k u t t 2 3 4 ii) Aplicar las propiedades del teorema 45. r t ti 2t j t k, u t t k 12.2. 4 2 2 j3 3t 3k, 2 2t 4 t4 45. r t ti 2t u t 45. r t ti j t u t 22sin 33k,u t tk, 4t4kk 45.46. r t ti 2t j t k, k t r t cos t i t j u t 45. r t ti 2t j t k, u t t 45. rrsttd 5 cos ti 1t i2t j sin 1 tt jk, t uk,std 5 46. u tt kkj j tktk i 1 sin sin tk, k, j 1 tk tk 46. 46. r46.t rrrrsttttdcos tcos i tttiitisin tsen j tttjjtjtj k, u tu 46. 5 cos cos sin 1 tttk, tk 46. cos sin k, uuusttttdj 5 jjjtk tk InInExercises Exercises4747and and48, 48,find findthe theangle angle between betweenr rt tand andr rt tasas function of Use a graphing utility to graph t. .trand In Exercises 47 and 48, find the angle between r t rasthe In Exercises 47 and 48, find the angle between and as r t tt tfunEn los ejercicios 47 y hallar el ángulo entre y u r x t c InaExercises 47 and 48, find the angle between and r t r9Use tcrren a function Use48, a find graphing utilitybetween to graph the .xtUse In Exercisesof 47t.and the angle asas r t and to find any extrema of the function. Find any values of t t afunction function of Use a graphing utility to graph Use the t. t . aagraph of Use a graphing utility to graph Use the t. t . ción de t. Usar una herramienta de graficación para representar a graph function of Use a graphing utility to graph Use the t. t . to find extrema of theutility function. Find anyt values of function of t.any Use a graphing to graph . Use the atgraph which the are find any extrema the function. Find any values graph toto find any extrema ofofthe the function. Find any values ofoftt t lavectors gráfica para hallar todos losFind extremos devalues la función. ugraph xtwhich cto. Usar graph find any extrema oforthogonal. the function. anyany values of tof at the vectors areorthogonal. to find any extrema of function. Find atwhich which thevectors vectors arede orthogonal. at the orthogonal. Hallar todos los valores t en que los vectores son ortogonales. at which the vectors areare orthogonal. 2 at which the vectors are orthogonal. 47. costjtj 48. 47.r rt t 3 3sinsinti ti 4 4cos 48.r rt t t it 2i tjtj 2 2 2 2 sinti ii 1tj 3333sin 4444cos 47. 48. cos sen t rrrrtt sttd i5tt 2tiit tj r47.t rrrrsttttd35 sin tisin cos tjcostj 47. 47. r48. sin tititi41 cos tjtjtj 48. 48. tjtjtj 47. 48. || || 1053714_1202.qxp 10/27/08 11:48 AM Page 849 12-2.qxd 3/12/09 18:10 Page 849 1053714_1202.qxp 10/27/08 11:48 AM Page 849 SECCIÓN 12.2 Derivación e integración de funcionesFunctions vectoriales 12.2 Differentiation and Integration of Vector-Valued 849 849 12.2 849 Differentiation and Integration of Vector-Valued Functions In Exercises 49–49 52,ause of the to para find En los ejercicios 52, the usardefinition la definición dederivative la derivada r9 xtc. r9 xtc. hallar In Exercises 49– 52, use the definition of the derivative to find 5 ss3t 3t 1 1 22ddii 1 1 ss11 2 2 tt22ddjj 50. r std 5 !t i 1 3 j 2 2tk r49. 9 xtcr.rssttdd 5 49. t 3 49. 5 kts! 3t 1 2di 1 2 t 2dj 52. rstd 5 k0, sin 2,t0, i1 j 2s12tk 50. rrssttdd 5 2tl t, 4tl 51. sen t 3 i 12tl j 2 2tk 50. kt2t, 0, 51. r std 5 ! 52. rstd 5 k0, sin t, 4tl En los ejercicios 53ta 60, hallar la integral indefinida. E EEE1 EEE311 EEE 33 EEE1 E1 E1 E EEE E E E EE E E EE 1 EE 1 E1 rstd 5 kt253– , 0, 2tl 5 k0, sin t, 4tl 51. 52. rstdintegral. In Exercises 60, find the indefinite s2ti 1 j 1 kd dt 53. 54. s4t 3 i 1 6tj 2 4!t kd dt In Exercises 53– 60, find the indefinite integral. s12ti 1 j 1 kd dt 53. 54. s4t 3 i 1 6tj 1 2 4!t kd dt i 1 j 2 t 3y2 k dt ln ti 1 j 1 k dt 55. 56. t 1 j 1 kd dt t s2ti 53. 54. s4t 3 i 1 6tj 1 2 4!t kd dt 1 ln ti 1 j 1 k dt i 1 j 2 t 3y2 k dt 55. 56. t t 2 1di 1 4t 3j 1 3!t k dt s12t 57. 1 ln ti 1 j 1 k dt i 1 j 2 t 3y2 k3 dt 55. 56. t st2t 2 1di 1 4t j 1 3!t k dt 57. set i 1 sen sin tj 1 cos tkd dt 58. s2t 2 1di 1 4t 3j 1 3!t k dt 57. set i 1 sin tj 11 cos tkd dt 58. sec2 ti 1 j dt se2t sen sin ti 1 e2t cos tjd dt 59. 60. 1tj11t 2cos tkd dt set i 1 sin 58. 1 sec2 ti 1 j dt se2t sin ti 1 e2t cos tjd dt 59. 60. 1 1 t2 En los ejercicios 61 1a 66, evaluar la integral definida. sec2 ti 1 j dt se2t sin ti 1 e2t cos tjd dt 59. 60. 1 1 t2 In Exercises 61– 166,1evaluate the definite integral. s8ti 1 tj 2 kd dt 61. 62. sti 1 t 3j 1 !3 t kd dt 1 01 21 In Exercises 61– 66, evaluate the definite integral. 61. py2s8ti 1 tj 2 kd dt 62. sti 1 t 3j 1 !3 t kd dt 1 sin td j 1 kg dt21 63. 01 fsa cos td i 1 sa sen s8ti 1 tj 2 kd dt 61. 0 py2 62. sti 1 t 3j 1 !3 t kd dt 63. 0 fsa cos td i 1 sa sin td j 1 kg dt21 64. 63. 64. py4 0py2 py4 0 0 02py4 65. 64. 65. 2 00 02 2 2 2 2 2 2 4 4 4 2 2 2 E E E E E E fsfssec t tan di 1 tanttddjj 1 1 ks2g dt sin t cos tdkg dt sen a cos td i t1 sa ssin fssec t tan tdi 1 stan tdj 1 s2 sin t cos tdkg dt EE E 3 sti fs1sec et jt tan 2 tetdtik1 d dtstan tdj 166.s2 sin i 1 ttd2kji dt 3 it t cos g dt sti 1 et j 2 te t kd dt 66. 0 it i 1 t 2 ji dt 03 xtc paraitlas En 67 te a t72, dadas. sti 1 et j 2 kd dthallar r66. i 1condiciones t 2 ji dt 65. los ejercicios In Exercises 67– 72, find rxtc for the given conditions. 0 0 2t i 1 3et j, rr99ssttdd 5 67. 2t i 1 3et j, rrss00dd 5 5 4e 4e67– 5 2i 2i given conditions. 67.Exercises In 72, find rxtc for the 22 ! r 9 s t d 5 3t j 1 6 t k, r s 0 d 5 68. 1 2j 2j 68. r9 std 5 3t j 1 6!t k, r s0d 5 ii 1 67. r9 std 5 4e2t i 1 3et j, rs0d 5 2i ! ! r 9 s 0 d 5 600 3i 1 600j, rrss00dd 5 69. 5 232j, 232j, r 9 s 0 d 5 600 3i 1 600j, 5 00 69. rr00ssttdd 5 68. r9 std 5 3t 2 j 1 6!t k, r s0d 5 i 1 2j 24cos costjtj 2 2 3sen sintk, tk, rr99ss00dd 5 5 3k, 3k, rrss00dd 5 5 4j 70. r0 std 5 24 sin 70. rs0d 5 0 4 j 5 232j, r9 s0d3 5 600!3i 1 600j, 69. rr00ssttdd 5 1 2t22 2t 1 r r 9 s t d 5 te i 2 e j 1 k, s 0 d 5 i 2 j 1 k 71. 2t icos 2 tj e2t2j 31sin k, tk,r s0rd95 j1k 71. r s0d 5 4 j 5 te24 s0d22i523k, 70. rr90ssttdd 5 12 1 1 1 2t 2t e 12j j11k, i2 71. 1d 25 2i j 1 k 1 k,r s0rds5 72. r9 std 5 te 1 i 22i 1 72. r9 std 5 1 1 t2 i 1 t2 j 1 t k, rs1d 5 2i 1 11 t t1 t1 i 1 2 j 1 k, rs1d 5 2i 72. r9 std 5 2 W R I T I N G1 1A Bt O U Tt C O NtC E P T S 73. State the definition of the derivative of a vector-valued WRITING ABO U Tconceptos CONCEPTS Desarrollo de function. Describe how to find the derivative of a vector- 73. State definition of the derivative interpretation. of a vector-valued valuedthe function anddegive geometric 73. Definir la derivada una its función vectorial. Describir cómo function. Describe how to find the derivative of a vectorla you derivada de integral una función vectorial y dar su inter74. hallar How do find the of a vector-valued function? valued function and give its geometric interpretation. pretación geométrica. 75. The three components of the derivative of the vector-valued 74. How do you find the integral of a vector-valued function? 74. ¿Cómo la integral una función vectorial? . Describe functionseuencuentra are positive at t 5 t0de the behavior of u 75. The three components of the derivative of the vector-valued at t 5 75. Las trest0.componentes de la derivada de la función vectofunction u are positive at t 5 t0. Describe the behavior of u positivas of en the t 5 derivative t0. Describir 76. rial Theu z-son component of elthecomportamiento vector-valued at t 5 t0. de u en t 5 t0. 0 for t in the domain of the function. What function u is 76. The zcomponent of the derivative of the of vector-valued does this information about graph u? 76. La componente z de laimply derivada de the la función vectorial u es function u is 0 for t in the domain of the function. What 0 para t en el dominio de la función. ¿Qué implica esta infordoes this information imply about the graph of u? mación acerca de la gráfica de u? In 77–84, the property. In each case, assume En Exercises los ejercicios 77 aprove 84, demostrar la propiedad. En todos los r, u, and v are differentiable vector-valued functions derivables of t in space, casos, suponer que r, u y v son funciones vectoriales de In 77–84, prove property. each case, assume w isExercises a differentiable real-valued function andcces is un a scalar. t, que w es una función real the derivable de of t,In yt,que escalar. r, u, and v are differentiable vector-valued functions of t in space, fcrstdg 5 cr9 stdreal-valued function of t, and c is a scalar. 77.is D w a tdifferentiable 78. D frstd ± ustdg 5 r9 std ± u9 std 77. Dttfcrstdg 5 cr9 std 79. D fw stdrstdg 5 w stdr9 std 1 w9stdrstd 78. Dttfrstd ± ustdg 5 r9 std ± u9 std 80. D fr std 3 ustdg 5 r std 3 u9 std 1 r9 std 3 ustd 79. Dttfw stdrstdg 5 w stdr9 std 1 w9stdrstd 81. D frsw stddg 5 r9 sw stddw9std 80. Dttfr std 3 ustdg 5 r std 3 u9 std 1 r9 std 3 ustd 82. D fr std 3 r9 stdg 5 r std 3 r0 std 81. Dttfrsw stddg 5 r9 sw stddw9std 83. D Hr std ? fustd 3 vstdgJ 5 r9 std ? fustd 3 v stdg 1 r9 stdg 5 r std 3 r0 std 82. Dttfr std 3 r std fu9 std 3 v stdg 1 r std fustd 3 v9 stdg 83. Dt Hr?std ? fustd 3 vstdgJ 5 r9?std ? fustd 3 v stdg 1 r std r std is a constant, 0. 84. If then r std ? r9 strdst5 constante, rSistdr stdf?u?9 rstsdtd3esv suna tdg 1 r std fusentonces td 3 v9 stdg d ? r9 std 5 0. ? ? 85. If Movimiento partícula se mueve r std ? rMotion std isdea una d ? in r9partícula sthe td 5xy0.-plane r stUna 84. constant, thenmoves 85. Particle A particle alongen theel plano xy represented a lo largo de laby curvathe representada por la función veccurve vector-valued function st 2 sin t1di 2 1 cos s1 moves 2 dj.the xy-plane along the 85. Particle A sparticle rtorial std 5rssttdMotion 25sin tdi sen 1 tdj.cos tin curve represented by the vector-valued functionr. a) Usar herramienta graficación paratherepresentar r. Describe (a) Use auna graphing utility todegraph curve. rstdDescribir 5 st 2 sin t d i 1 s 1 2 cos t d j. la curva. (b) Find the minimum and maximum values of ir9 i and ir0 i. r. Describe (a) Use a graphing utility to graph curve. b) Hallar los valores mínimo y máximo de ir9 ithe y ir 0 i. 86. Particle Motion A particle moves in the yz-plane along the ir 9 i 0 i. (b) Find the minimum and maximum values of and iren 86. curve Movimiento de una partícula partícula se mueve represented by theUnavector-valued functionel plano yz a lo largo de la curva representada por la función vecyz 86. rParticle Motion A particle moves in the -plane along the std 5 s2 cos tdj 1 s3 sin tdk. sen torial rstdrepresented 5 s2 cos tdj 1bys3 sin tdk. vector-valued function curve the (a) Describe the curve. 5 s2 cos la tdjcurva. 1 s3 sin tdk. ra)stdDescribir (b) Find the minimum and maximum values of ir9 i and ir0 i. (a) Describe the curve. b) Hallar los valores mínimo y máximo de ir9 i y ir0 i. 87. Consider the vector-valued function (b) Find the minimum and maximum values of ir9 i and ir0 i. 87. Considerar la función vectorial rstd 5 set sin tdi 1 set cos tdj. 87. Consider t the vector-valued function rstd 5 se sen sin tdi 1 set cos tdj. t t rstdtdand d aretdj. always perpendicular to each other. rShow std 5 that se sin i 1 rse0stcos Mostrar que rstd y r0std son siempre perpendiculares a cada uno. that C AShow PSTO N Erstd and r0std are always perpendicular to each other. Para discusiónConsider the vector-valued function C88. A PInvestigation STONE 2 r std 5 ti 1 s4 2 t dj. 88. Investigation Investigación Considerar vectorial r(t) 5 ti 1 88. Consider la thefunción vector-valued function 2)j. the graph (a) Sketch of rstd. Use a graphing utility to verify r(4std25t ti 1 s4 2 t 2dj. your graph. a) Trazar Usara una herramienta grafistd. Use (a) Sketch la thegráfica graph de of rr(t). graphing utility todeverify (b) cación Sketchpara the vectors 1d,gráfica. r s1.25d, and r s1.25d 2 r s1d on verificarr ssu your graph. the graph in part (a). b) Trazar r(1.25) 2 dr(1) (b) Sketchlos thevectores vectors r(1), r s1d, r(1.25) r s1.25d,yand r s1.25 2 rsobre s1d onla r9 (1d with the vector (c) gráfica Compare vectora). en the el inciso the graph in part (a). 1d . r9(1) con el vector r s1.25d 2elr svector c) Comparar (c) Compare the vector r9 (1d with the vector 1.25 2 1 r s1.25d 2 r s1d . 1.25 2 1 True or False? In Exercises 89–92, determine whether the statement or false. If ejercicios it is false, 89 explain why or givesianla ¿Verdaderoisotrue falso? En los a 92, determinar True or False? In itExercises 89–92, whether theo example thatesshows is false. declaración verdadera o falsa. Si es determine falsa, explicar por qué statement is trueque or muestre false. If que it is es false, explain why or give an dar un ejemplo falsa. 89. If a particle moves example that shows it isalong false.a sphere centered at the origin, then 89. its Si una partícula se mueve a lo tangent largo detouna centrada en el derivative vector is always theesfera sphere. 89. If a particle movessualong a sphere centered at thetangente origin, then origen, entonces vector derivada es siempre a la 90. The definite integral of a vector-valued function is a real number. its derivative vector is always tangent to the sphere. esfera. d 90. definite integral vector-valued functionesisun a real number. stdig 5definida ir9stdi of 91. 90. The Lafir integral deauna función vectorial número real. dt dd ssttddiiggu5 ir ssttddii 91. 92. If ffrir vector-valued functions of t, then 91. dt irand 5are ir99differentiable dt frstd ustdg 5 r9std u9std. D ? ? t 92. are differentiable vector-valued functions t, then Si rrand y uu son funciones vectoriales derivables de t,ofentonces 92. If D Dttffrrssttdd ?? uussttdg dg 5 5 rr99ssttdd ?? uu99ssttdd.. 3/12/09 850 18:11 Page 850 CAPÍTULO 12 Funciones vectoriales 12.3 Velocidad y aceleración n n Describir la velocidad y la aceleración relacionadas con una función vectorial. Usar una función vectorial para analizar el movimiento de un proyectil. Velocidad y aceleración EXPLORACIÓN Exploración de velocidad Considérese el círculo dado por rstd 5 scos vtdi 1 ssin sen vtdj. Usar una herramienta de graficación en modo paramétrico para representar este círculo para varios valores de w . ¿Cómo afecta w a la velocidad del punto final cuando se traza la curva? Para un valor dado de w , ¿parece ser constante la velocidad? ¿Parece ser constante la aceleración? Explicar el razonamiento. 2 Ahora se combina el estudio de ecuaciones paramétricas, curvas, vectores y funciones vectoriales a fin de formular un modelo para el movimiento a lo largo de una curva. Se empezará por ver el movimiento de un objeto en el plano. (El movimiento de un objeto en el espacio puede desarrollarse de manera similar.) Conforme un objeto se mueve a lo largo de una curva en el plano, la coordenada x y la coordenada y de su centro de masa es cada una función del tiempo t. En lugar de utilizar ƒ y g para representar estas dos funciones, es conveniente escribir x 5 xstd y y 5 ystd. Por tanto, el vector de posición rstd toma la forma rstd 5 xstdi 1 ystdj. Vector de posición. Lo mejor de este modelo vectorial para representar movimiento es que se pueden usar la primera y la segunda derivadas de la función vectorial r para hallar la velocidad y la aceleración del objeto. (Hay que recordar del capítulo anterior que la velocidad y la aceleración son cantidades vectoriales que tienen magnitud y dirección.) Para hallar los vectores velocidad y aceleración en un instante dado t, considérese un punto Qsxst 1 Dtd, yst 1 Dtdd que se aproxima al punto Psxstd, ystdd a lo largo de la curva C dada por rstd 5 xstdi 1 ystdj, como se muestra en la figura 12.11. A medida que Dt → 0, la dirección del vector PQ (denotado por Dr) se aproxima a la dirección del movimiento en el instante t. \ −3 3 Dr 5 rst 1 Dtd 2 rstd Dr rst 1 Dtd 2 rstd 5 Dt Dt Dr rst 1 Dtd 2 rstd lim 5 lim lím lím Dt→0 Dt Dt→0 Dt −2 Si este límite existe, se define como el vector velocidad o el vector tangente a la curva en el punto de P. Nótese que éste es el mismo límite usado en la definición de r9 std. Por tanto, la dirección de r9 std da la dirección del movimiento en el instante t. La magnitud del vector r9 std ir9 stdi 5 ix9stdi 1 y9stdji 5 !fx9stdg 2 1 f y9stdg 2 da la rapidez del objeto en el instante t. De manera similar, se puede usar r0 std para hallar la aceleración, como se indica en las definiciones siguientes. y y Vector velocidad en el instante t P C ∆r Vector velocidad en el instante t ∆t → 0 12-3.qxd Q r(t) r(t + ∆t) x Conforme Dt → 0, Figura 12.11 Dr se aproxima al vector velocidad Dt x 12-3.qxd 3/12/09 18:11 Page 851 SECCIÓN 12.3 Velocidad y aceleración 851 DEFINICIONES DE VELOCIDAD Y ACELERACIÓN Si x y y son funciones de t que tienen primera y segunda derivadas y r es una función vectorial dada por rstd 5 xstdi 1 ystdj, entonces el vector velocidad, el vector aceleración y la rapidez en el instante t se definen como sigue. Velocidad Velocity 5 vstd 5 r9std 5 x9stdi 1 y9stdj Aceleración 5 astd 5 r0 std 5 x0 stdi 1 y0 stdj Acceleration Rapidez Speed 5 ivstdi 5 ir9stdi 5 !fx9stdg 2 1 f y9stdg 2 Para el movimiento a lo largo de una curva en el espacio, las definiciones son similares. Es decir, si rstd 5 xstdi 1 ystdj 1 zstdk, entonces Velocity 5 vstd 5 r9 std 5 x9stdi 1 y9stdj 1 z9stdk Velocidad Acceleration Aceleración 5 astd 5 r0 std 5 x0 stdi 1 y0 stdj 1 z0stdk Speed 5 ivstdi 5 ir9 stdi 5 !fx9stdg 2 1 f y9stdg 2 1 fz9stdg 2. Rapidez EJEMPLO 1 NOTA En el ejemplo 1, nótese que los vectores velocidad y aceleración son ortogonales en todo punto y en cualquier instante. Esto es característico del movimiento con rapidez constante. (Ver ejercicio 57.) n Hallar la velocidad y la aceleración a lo largo de una curva plana Hallar el vector velocidad, la rapidez y el vector aceleración de una partícula que se mueve a lo largo de la curva plana C descrita por t t rstd 5 2 sen sin i 1 2 cos j. 2 2 Vector posición. Solución El vector velocidad es t t vstd 5 r9std 5 cos i 2 sen sin j. 2 2 Vector velocidad. La rapidez (en cualquier instante) es ir9std i 5 t sin 5 1. !cos 2t 1sen 2 2 2 Rapidez. El vector aceleración es Círculo: x2 + y2 = 4 y 1 t 1 t astd 5 r0 std 5 2 sen sin i 2 cos j. 2 2 2 2 Vector aceleración. 2 Las ecuaciones paramétricas de la curva del ejemplo 1 son v(t) a(t) 1 x 5 2 sen sin −2 x −1 1 2 −1 −2 t t r(t) = 2 sen i + 2 cos j 2 2 La partícula se mueve alrededor del círculo con rapidez constante Figura 12.12 t 2 y t y 5 2 cos . 2 Eliminando el parámetro t, se obtiene la ecuación rectangular x 2 1 y 2 5 4. Ecuación rectangular. Por tanto, la curva es un círculo de radio 2 centrado en el origen, como se muestra en la figura 12.12. Como el vector velocidad t t vstd 5 cos i 2sen sin j 2 2 tiene una magnitud constante pero cambia de dirección a medida que t aumenta, la partícula se mueve alrededor del círculo con una rapidez constante. 12-3.qxd 3/12/09 852 18:11 Page 852 CAPÍTULO 12 Funciones vectoriales EJEMPLO 2 r(t) = (t 2 − 4)i + tj y Dibujar la trayectoria de un objeto que se mueve a lo largo de la curva plana dada por 4 v(2) 3 rstd 5 st 2 2 4di 1 t j a(2) v(0) −3 −2 −1 −1 Solución Utilizando las ecuaciones paramétricas x 5 t 2 2 4 y y 5 t, se puede determinar que la curva es una parábola dada por x 5 y 2 2 4, como se muestra en la figura 12.13. El vector velocidad (en cualquier instante) es x 1 2 3 4 vstd 5 r9std 5 2t i 1 j −3 −4 Vector posición. y hallar los vectores velocidad y aceleración cuando t 5 0 y t 5 2. 1 a(0) Dibujo de los vectores velocidad y aceleración en el plano x = y2 − 4 Vector velocidad. y el vector aceleración (en cualquier instante) es En todo punto en la curva, el vector aceleración apunta a la derecha astd 5 r0 std 5 2i. Figura 12.13 Vector aceleración. Cuando t 5 0, los vectores velocidad y aceleración están dados por v(0) 5 2(0)i 1 j 5 j y y a(0) 5 2i. Cuando t 5 2, los vectores velocidad y aceleración están dados por v(2) 5 2(2)i 1 j 5 4i 1 j y Sol a(2) 5 2i. Si el objeto se mueve por la trayectoria mostrada en la figura 12.13, nótese que el vector aceleración es constante (tiene una magnitud de 2 y apunta hacia la derecha). Esto implica que la rapidez del objeto va decreciendo conforme el objeto se mueve hacia el vértice de la parábola, y la rapidez va creciendo conforme el objeto se aleja del vértice de la parábola. Este tipo de movimiento no es el característico de cometas que describen trayectorias parabólicas en nuestro sistema solar. En estos cometas, el vector aceleración apunta siempre hacia el origen (el Sol), lo que implica que la rapidez del cometa aumenta a medida que se aproxima al vértice de su trayectoria y disminuye cuando se aleja del vértice. (Ver figura 12.14.) x a En todo punto de la órbita del cometa, el vector aceleración apunta hacia el Sol Figura 12.14 EJEMPLO 3 Dibujo de los vectores velocidad y aceleración en el espacio Dibujar la trayectoria de un objeto que se mueve a lo largo de la curva en el espacio C dada por rstd 5 t i 1 t 3j 1 3tk, t ≥ 0 Curva: r(t) = ti + t3j + 3tk, t ≥ 0 y hallar los vectores velocidad y aceleración cuando t 5 1. Solución Utilizando las ecuaciones paramétricas x 5 t y y 5 t 3, se puede determinar que la trayectoria del objeto se encuentra en el cilindro cúbico dado por y 5 x3. Como z 5 3t, el objeto parte de s0, 0, 0d y se mueve hacia arriba a medida que t aumenta, como se muestra en la figura 12.15. Como rstd 5 t i 1 t 3j 1 3tk, se tiene C z v(1) 6 (1, 1, 3) a(1) 4 y 2 10 2 4 x Figura 12.15 Vector posición. vstd 5 r9std 5 i 1 3t 2j 1 3k Vector velocidad. astd 5 r0 std 5 6tj. Vector aceleración. y Cuando t 5 1, los vectores velocidad y aceleración están dados por v(1) 5 r9(1) 5 i 1 3j 1 3k y a(1) 5 r0(1) 5 6j . 12-3.qxd 3/12/09 18:11 Page 853 SECCIÓN 12.3 Velocidad y aceleración 853 Hasta aquí se ha tratado de hallar la velocidad y la aceleración derivando la función de posición. En muchas aplicaciones prácticas se tiene el problema inverso, hallar la función de posición dadas una velocidad o una aceleración. Esto se demuestra en el ejemplo siguiente. Hallar una función posición por integración EJEMPLO 4 Un objeto parte del reposo del punto P(1, 2, 0) y se mueve con una aceleración astd 5 j 1 2k Vector aceleración. donde iastdi se mide en pies por segundo al cuadrado. Hallar la posición del objeto después de t 5 2 segundos. Solución A partir de la descripción del movimiento del objeto, se pueden deducir las condiciones iniciales siguientes. Como el objeto parte del reposo, se tiene vs0d 5 0. Como el objeto parte del punto sx, y, zd 5 s1, 2, 0d, se tiene rs0d 5 xs0di 1 ys0dj 1 zs0dk 5 1i 1 2j 1 0k 5 i 1 2j. Para hallar la función de posición, hay que integrar dos veces, usando cada vez una de las condiciones iniciales para hallar la constante de integración. El vector velocidad es vstd 5 E astd dt 5 E s j 1 2kd dt 5 tj 1 2tk 1 C donde C 5 C1i 1 C2 j 1 C3k. Haciendo t 5 0 y aplicando la condición inicial vs0d 5 0, se obtiene vs0d 5 C1i 1 C2 j 1 C3k 5 0 Por tanto, la velocidad en cualquier instante t es Curva: r(t) = i + ( 2 + 2) j + t k t2 vstd 5 t j 1 2tk. 2 rstd 5 C 6 E vstd dt 5 4 r(2) 2 2 (1, 2, 0) t=0 5 (1, 4, 4) t=2 6 y 6 El objeto tarda 2 segundos en moverse del punto (1, 2, 0) al punto (1, 4, 4) a lo largo de C E stj 1 2t kd dt t2 j 1 t2k 1 C 2 donde C 5 C4i 1 C5 j 1 C6k. Haciendo t 5 0 y aplicando la condición inicial r(0) 5 i 1 2j, se tiene rs0d 5 C4i 1 C5 j 1 C6k 5 i 1 2j C4 5 1, C5 5 2, C6 5 0. Por tanto, el vector posición es x Figura 12.16 Vector velocidad. Integrando una vez más se obtiene z 4 C1 5 C2 5 C3 5 0. rstd 5 i 1 1t2 1 22 j 1 t k. 2 2 Vector posición. La posición del objeto después de t 5 2 segundos está dada por rs2d 5 i 1 4j 1 4k, como se muestra en la figura 12.16. 12-3.qxd 3/12/09 854 18:11 Page 854 CAPÍTULO 12 Funciones vectoriales Movimiento de proyectiles Ahora ya se dispone de lo necesario para deducir las ecuaciones paramétricas de la trayectoria de un proyectil. Supóngase que la gravedad es la única fuerza que actúa sobre un proyectil después de su lanzamiento. Por tanto, el movimiento ocurre en un plano vertical que puede representarse por el sistema de coordenadas xy con el origen correspondiente a un punto sobre la superficie de la Tierra (figura 12.17). Para un proyectil de masa m, la fuerza gravitatoria es y v = velocidad inicial 0 v(t1) v0 = v(0) a a v(t2) F 5 2mgj a Altura inicial x Figura 12.17 Fuerza gravitatoria. donde la constante gravitatoria es g 5 32 pies por segundo al cuadrado, o 9.81 metros por segundo al cuadrado. Por la segunda ley del movimiento de Newton, esta misma fuerza produce una aceleración a 5 astd, y satisface la ecuación F 5 ma. Por consiguiente, la aceleración del proyectil está dada por ma 5 2mgj, lo que implica que a 5 2gj. EJEMPLO 5 Aceleración del proyectil. Obtención de la función de posición de un proyectil Un proyectil de masa m se lanza desde una posición inicial r0 con una velocidad inicial v0. Hallar su vector posición en función del tiempo. Solución Se parte del vector aceleración astd 5 2gj y se integra dos veces. vstd 5 rstd 5 E E astd dt 5 vstd dt 5 E E 2g j dt 5 2gt j 1 C1 1 s2gtj 1 C1d dt 5 2 gt 2j 1 C1t 1 C2 2 Se puede usar el hecho de que vs0d 5 v0 y rs0d 5 r0 para hallar los vectores constantes C1 y C2. Haciendo esto se obtiene C1 5 v0 y C2 5 r0. Por consiguiente, el vector posición es 1 rstd 5 2 gt 2j 1 t v0 1 r0. 2 Vector posición. En muchos problemas sobre proyectiles, los vectores constantes r0 y v0 no se dan explícitamente. A menudo se dan la altura inicial h, la rapidez inicial v0 y el ángulo u con que el proyectil es lanzado, como se muestra en la figura 12.18. De la altura dada, se puede deducir que r0 5 hj. Como la rapidez da la magnitud de la velocidad inicial, se sigue que v0 5 iv0i y se puede escribir v0 = v0 = rapidez inicial r0 = h = altura inicial v0 5 x i 1 y j y 5 siv0i cos udi 1 siv0i sen sin udj 5 v0 cos u i 1 v0 sin sen uj. v0 Por tanto, el vector posición puede expresarse en la forma yj θ 1 rstd 5 2 gt 2j 1 t v0 1 r0 2 xi h Vector posición. r0 x x = v0 cos θ y = v0 sen θ Figura 12.18 1 5 2 gt 2j 1 tv0 cos u i 1 tv0 sen sin u j 1 hj 2 1 5 sv0 cos udti 1 h 1 sv0 sen sin udt 2 gt 2 j. 2 3 4 12-3.qxd 3/12/09 18:11 Page 855 SECCIÓN 12.3 Velocidad y aceleración 855 TEOREMA 12.3 FUNCIÓN DE POSICIÓN DE UN PROYECTIL Despreciando la resistencia del aire, la trayectoria de un proyectil lanzado de una altura inicial h con rapidez inicial v0 y ángulo de elevación u se describe por medio de la función vectorial 3 rstd 5 sv0 cos udti 1 h 1 sv0 sin sen udt 2 4 1 2 gt j 2 donde g es la constante de la gravedad. EJEMPLO 6 10 pies 45° 300 pies 3 pies Figura 12.19 La trayectoria de una pelota de béisbol Una pelota de béisbol es golpeada 3 pies sobre el nivel del suelo a 100 pies por segundo y con un ángulo de 45° respecto al suelo, como se muestra en la figura 12.19. Hallar la altura máxima que alcanza la pelota de béisbol. ¿Pasará por encima de una valla de 10 pies de altura localizada a 300 pies del plato de lanzamiento? Solución Se tienen dados h 5 3, v0 5 100, y u 5 458. Así, tomando g 5 32 pies por segundo al cuadrado se obtiene 1 rstd 5 100 cos p p t i 1 3 1 100 sen sin t 2 16t 2 j 4 4 2 3 1 2 4 5 s50!2 tdi 1 s3 1 50!2 t 2 16t 2dj vstd 5 r9std 5 50!2 i 1 s50!2 2 32tdj. La altura máxima se alcanza cuando y9std 5 50!2 2 32t 5 0 lo cual implica que t5 25!2 16 < 2.21 segundos. Por tanto, la altura máxima que alcanza la pelota es y 5 3 1 50!2 5 1 2 1 25!2 25!2 2 16 16 16 2 2 649 8 < 81 pies. feet. Altura máxima cuando t < 2.21 segundos. La pelota está a 300 pies de donde fue golpeada cuando 300 5 xstd 5 50!2 t. Despejando t de esta ecuación se obtiene t 5 3!2 < 4.24 segundos. En este instante, la altura de la pelota es y 5 3 1 50!2 s3!2 d 2 16s3!2 d 2 5 303 2 288 5 15 pies. feet. Altura cuando t < 4.24 segundos. Por consiguiente, la pelota pasará sobre la valla de 10 pies. n to find n at time odel for projectile an initial above the th of the ctile fired elocity of orizontal. bat at an above the tial speed eet to the eet above ur and at does the n for the uation is 12-3.qxd 3/12/09 856 856 18:11 Chapter 12 Vector-Valued Functions CAPÍTULO 12 Funciones vectoriales 12.3 Exercises 12.3 Ejercicios See www.CalcChat.com for worked-out solutions to odd-numbered exercises. r r describe la trayectoEn los ejercicios 1 a 10, el vector posición ria de un objeto que sexymueve en el plano xy. Dibujar una gráfica de la trayectoria y dibujar los vectores velocidad y aceleración en elFunction punto dado. Position Point Función rt 3tposición i t 1j Punto 3, 0 1. rrstdt 5 3t6i 1 tsti 2 1tdjj s3,3,03d s3,4,32d s4,1,23d 1,1,31 1,3,12 3, 22, 2 s!3,2,0 !2 d s3, ,02d sp1,, 21d i tdti j1 t j 2. rrstdt 5 st62 2 3. rrstdt 5 tt2ii 1 t j t2 4. rrt t t ti2 i t 3tj2 5. rrt t t2 14i t3 t 3 1j i 6. rrt t 4 j 4 j tj 1 24 t3cos t1i i 2 tj sin t j costtii1 22sin sinttjj 7. rrstdt 5 23cos sen i 1t, 21 sin tj t 8. rrstdt 5 3 tcos tsin sen cos sin t, 1 2 cos tl 9. rrstdt 5 kte2 sen t, et 10. rstd 5 ke2t, et l En los ejercicios 23 a 28, usar la función aceleración dada para determinar los vectores velocidad y posición. Después hallar la tposición 2. en el instante t 5 2. 23. astd 5 i 1 j 1 k vs0 d 5 0, rs0d 5 0 24. astd 5 2i 1 3k vs0 d 5 4j, rs0 d 5 0 25. astd 5 t j 1 t k vs1 d 5 5j, rs1 d 5 0 26. a t v0 32 k 3i 27. a t v0 s1, 1d 2j k, cos t i j k, 28. a(t) et i 8k v0 2i 3j r0 5j 2k sen t j r0 i k, r 0 0 En los ejercicios 11 a 20, el vector posición r describe la trayectoria de un objeto que se mueve en el espacio. Hallar velocidad, rapit t i 5tj 3t k rt 4t i 4t j 2t k dez yraceleración del objeto. Movimiento de proyectiles En los ejercicios 29 a 44, usar el modelo para el movimiento de un proyectil, suponiendo que no hay resistencia del aire. 1 2 t2 12. rr tt 4t 3t kk 3tii 4t t jj 2t t kk 4 2 2 t 1 13. rr tt ttii tt2j 3t i t j t2k 9k t 2 k 14. r t 2 4 2 3 2 rt t i t j 2t k2 15. r t ti tj 9 t k rt 4t, 3 cos t, 3 3sen t 2 t i t j 2t 2 k 16. r t r(t 2 cos t, 2 sen t, t2 4t, 3 cos t, 3 sen t 17. r t rt et cos t, et sen t, et 2 cos t, 2 sen t, t2 18. r(t 1 t 19. rr tt eln cos t, t,, te4t sen t, et t 1 ln t, , t 4 20. r t t r tlos ejercicios 21 y 22 se dan la gráfica Aproximación lineal En t t 0 de la función vectorial rxtc y un vector tangente a la gráfica en 29. Hallar la función vectorial de la trayectoria de un proyectil lanzado desde una altura de 10 pies sobre el suelo con 30 una velocidad inicial de 88 pies por segundo y con un ángulo de 30° sobre la horizontal. Usar una herramienta de graficación para representar la trayectoria del proyectil. 30. Determinar la altura máxima y el alcance de un proyectil disparado desde una altura de 3 pies sobre 45 el nivel del suelo con velocidad inicial de 900 pies por segundo y con un ángulo de 45° sobre la horizontal. 45 31. Una pelota de béisbol es golpeada 3 pies sobre el nivel del suelo, se aleja del bate con un ángulo de 45° y es cachada por un jardinero a 3 pies sobre el nivel del suelo y a 300 pies del plato de lanzamiento. ¿Cuál es la rapidez inicial de la pelota y qué altura alcanza? 32. Un jugador de béisbol en segunda base lanza una pelota al jugador de primera base a 90 pies. La pelota es lanzada desde 5 pies sobre el nivel del suelo con una velocidad inicial de 50 millas por hora y con un ángulo de 15° con la horizontal. ¿A qué altura cacha la pelota el jugador de primera base? 33. Eliminar el parámetro t de la función de posición para el movimiento de un proyectil y mostrar que la ecuación rectangular es 11. rr tt ttii 5tj t 2j t 5 t0. t t0 . de ecuaciones paramétricas para la recta a) Hallar un conjunto tangente a la gráfica en t 5 t0. r t0 1 0.1 . b) Utilizar las t0 la 1recta para aproximar r xt0 1 0.1c. rt t, ecuaciones t 2, 14 t3 , de 2, 1 t3 t, 2, t 25 t2 , 21. rrstdt 5 k t,t,2t 25 4 l 0 5 1 22. rstd 5 k t, !25 2 t 2, !25 z 2 t2 l, z 2 )1, −1, ) 1 4 2 1 x2 4 (1, −1, ) x Figura para 21 t0 3 t0 5 3 z (3, 4, 4) 5z (3, 4, 4) 5 2 n ion. Then which it Page 856 y 5 x 2 0.005x 2. −2 −2 1 1 y y y 16 sec2 u 2 x 1 stan udx 1 h. v02 34. La trayectoria de una pelota la da la ecuación rectangular y52 2 2 6 2 4 2 6 4 6 y 6 x x Figura para 22 Usar el resultado del ejercicio 33 para hallar la función de posición. Después hallar la velocidad y la dirección de la pelota en el punto en que ha recorrido 60 pies horizontalmente. 12-3.qxd 25/2/10 14:02 Página 857 SECCIÓN 12.3 35. Modelo matemático La trayectoria de una pelota lanzada por un jugador de béisbol es videograbada y después se analiza la grabación con una cuadrícula que cubre la pantalla. La cinta se detiene tres veces y se miden las posiciones de la pelota. Las coordenadas son aproximadamente (0, 6.0), (15, 10.6) y (30, 13.4). (La coordenada x mide la distancia horizontal al jugador en pies y la coordenada y mide la altura en pies.) a) Usar una herramienta de graficación para hallar un modelo cuadrático para los datos. b) Usar una herramienta de graficación para representar los datos y la gráfica del modelo. c) Determinar la altura máxima de la pelota. d) Hallar la velocidad inicial de la pelota y el ángulo al que fue lanzada. 36. Una pelota de béisbol es golpeada desde una altura de 2.5 pies sobre el nivel del suelo con una velocidad inicial de 140 pies por segundo y con un ángulo de 22° sobre la horizontal. Usar una herramienta de graficación para representar la trayectoria de la pelota y determinar si pasará sobre una valla de 10 pies de altura localizada a 375 pies del plato de lanzamiento. 37. El Rogers Centre en Toronto, Ontario, tiene una cerca en su campo central que tiene 10 pies de altura y está a 400 pies del plato de lanzamiento. Una pelota es golpeada a 3 pies sobre el nivel del suelo y se da el batazo a una velocidad de 100 millas por hora. a) La pelota se aleja del bate formando un ángulo de ⫽ 0 con la horizontal. Dar la función vectorial para la trayectoria de la pelota. b) Usar una herramienta de graficación para representar la función vectorial para 0 ⫽ 10⬚, 0 ⫽ 15⬚, 0 ⫽ 20⬚, y 0 ⫽ 25⬚. Usar las gráficas para aproximar el ángulo mínimo requerido para que el golpe sea un home run. c) Determinar analíticamente el ángulo mínimo requerido para que el golpe sea un home run. 38. El mariscal de campo de un equipo de fútbol americano lanza un pase a una altura de 7 pies sobre el campo de juego, y el balón de fútbol lo captura un receptor a 30 yardas a una altura de 4 pies. El pase se lanza con un ángulo de 35° con la horizontal. a) Hallar la rapidez del balón de fútbol al ser lanzado. b) Hallar la altura máxima del balón de fútbol. c) Hallar el tiempo que el receptor tiene para alcanzar la posición apropiada después de que el mariscal de campo lanza el balón de fútbol. 39. Un expulsor de pacas consiste en dos bandas de velocidad variable al final del expulsor. Su función es lanzar las pacas a un camión. Al cargar la parte trasera del camión, una paca debe lanzarse a una posición 8 pies hacia arriba y 16 pies detrás del expulsor. a) Hallar la velocidad inicial mínima de la paca y el ángulo correspondiente al que debe ser lanzada de la expulsora. b) La expulsora tiene un ángulo fijo de 45°. Hallar la velocidad inicial requerida. 40. Un bombardero vuela a una altitud de 30 000 pies a una velocidad de 540 millas por hora (ver la figura). ¿Cuándo debe lanzar la bomba para que pegue en el blanco? (Dar la respuesta en términos del ángulo de depresión del avión con relación al blanco.) ¿Cuál es la velocidad de la bomba en el momento del impacto? Velocidad y aceleración 857 540 mph 30 000 pies Figura para 40 41. Un disparo de un arma con una velocidad de 1 200 pies por segundo se lanza hacia un blanco a 3 000 pies de distancia. Determinar el ángulo mínimo de elevación del arma. 42. Un proyectil se lanza desde el suelo con un ángulo de 12° con la horizontal. El proyectil debe tener un alcance de 200 pies. Hallar la velocidad inicial mínima requerida. 43. Usar una herramienta de graficación para representar la trayectoria de un proyectil para los valores dados de y v0. En cada caso, usar la gráfica para aproximar la altura máxima y el alcance del proyectil. (Suponer que el proyectil se lanza desde el nivel del suelo.) a) ⫽ 10⬚, v0 ⫽ 66 ft兾sec pies/s b) ⫽ 10⬚, v0 ⫽ 146 pies/s ft兾sec c) ⫽ 45⬚, pies/s v0 ⫽ 66 ft兾sec d) ⫽ 45⬚, v0 ⫽ 146 ft兾sec pies/s e) ⫽ 60⬚, v0 ⫽ 66 ft兾sec pies/s ƒ) ⫽ 60⬚, v0 ⫽ 146 ft兾sec pies/s 44. Hallar el ángulo con el que un objeto debe lanzarse para tener a) el alcance máximo y b) la altura máxima. Movimiento de un proyectil En los ejercicios 45 y 46, usar el modelo para el movimiento de un proyectil, suponiendo que no hay resistencia. [a冇t冈 ⴝ ⴚ9.8 metros por segundo al cuadrado.] 45. Determinar la altura y el alcance máximos de un proyectil disparado desde una altura de 1.5 metros sobre el nivel del suelo con una velocidad inicial de 100 metros por segundo y con un ángulo de 30° sobre la horizontal. 46. Un proyectil se dispara desde el nivel del suelo con un ángulo de 8° con la horizontal. El proyectil debe tener un alcance de 50 metros. Hallar la velocidad mínima necesaria. Movimiento cicloidal En los ejercicios 47 y 48, considerar el movimiento de un punto (o partícula) en la circunferencia de un círculo que rueda. A medida que el círculo rueda genera la cicloide r冇t冈 ⴝ b冇 t ⴚ sen sin t冈i ⴙ b冇1 ⴚ cos t冈j, donde es la velocidad angular constante del círculo y b es el radio del círculo. 47. Hallar los vectores velocidad y aceleración de la partícula. Usar los resultados para determinar los instantes en que la rapidez de la partícula será a) cero y b) máxima. 48. Hallar la velocidad máxima de un punto de un neumático de automóvil de radio 1 pie cuando el automóvil viaja a 60 millas por hora. Comparar esta velocidad con la velocidad del automóvil. Movimiento circular En los ejercicios 49 a 52, considerar una partícula que se mueve a lo largo de una trayectoria circular de radio b descrita por r(t) ⴝ b cos ti ⴙ b sen tj donde ⴝ du兾兾dt es la velocidad angular constante. 49. Hallar el vector velocidad y mostrar que es ortogonal a r共t兲. 7/08 er 12 1053714_1203.qxp 10/27/08 11:49 AM 12-3.qxd 3/12/09 18:11 Page 858 11:49 AM Page 858 10/27/08 11:49 AM Page 858 1053714_1203.qxp 858 Page 858 CAPÍTULO 858 12 Vector-Valued Functions 858 Chapter 12 Funciones Chapter 12vectoriales Vector-Valued Functions Vector-Valued Functions . particle is b . 50. a) Mostrar que50. la rapidez de la partícula es bofvthe 59. Investigación 59. UnInvestigation objeto sigue una trayectoria dada A particle moveselíptica on an elliptical path given by (a) Show that the speed por lathe función vectorial rsmoves td 5 6on cosan t i elliptical 1 3 sen sinr tpath j. 6given cos tby i 3 sin t j. the function Investigation particle moves elliptical path given by vector-valued t the speed of the particle . una b)b Usar graficación paramétrico Investigation A particle 50. is (a) Show thatherramienta the speed ofde the particle isutility ben .modo (b) Use a59. graphing inAparametric modeon59. toangraph r t . Does 6 cos tgraphing i vector-valued 3 sin tvj.std, ivfunction 5vector-valued círculo Probar distintos valores i a3 sin a) Hallar st(a) d i, yFind astrd.vt t , 6vcos t ,tand t . t j. circleinpara for different values of the the bbthe 6.6.Try aphing utility in parametric mode graph elthe (b) para Use representar a tographing utility parametric mode to function graph the de ¿Dibuja la herramienta de graficación más rápido los v . draw circle greater of (a) ? b) Find tfaster , v the tfor,graphing a t values . (a)theFind and theb graphing b 6. Try different values of circle . Doesfor t , herramienta v t ,(b) ade t a.graficación andUse different values of v. Does 6. Try utility Usarvuna para completar la the tabla. graphing utility to complete table. círculos para loscircle valores de v?values w the circle faster for greater values ? 51. utilityof draw the faster for(b) greater ofand?utility Find themayores acceleration showtothat its direction is Use avector graphing complete the table. (b) Use a graphing utility to complete the table. p p 2p 51. Hallar el aceleración y mostrar que su of dirección es siemalways toward center thedirection circle. eleration vector and 51. show thatthe itsvector direction is vector p t 0 Find acceleration and the show that its is 2 4t 2 30 pre hacia el centro del círculo. 2 d the center of the circle. always toward the center of the circle. 4 2 2 52. Show that the magnitude of the acceleration vector is b . 3 2 0 t t Rapidez 0 2 52. Show Mostrar magnitud delthe vector aceleración es bisv2b4. 2. 2 . magnitude of the acceleration vector islabmagnitude 3 4 2 52. thatque the of acceleration vector 3 Speed Circular Motion In Exercises 53 and 54, use the results of Speed c) Representar gráficamente la trayectoria elíptica y los vecMovimiento circular En los ejercicios 53 y 54, usar los resultaSpeed Exercises 49– 52. In Exercises 53 and 54, use the results of Circular Motion In Exercises 53 and 54, use the results of tores velocidad y aceleración los valores de t the dados en la and acceleration dos de los ejercicios 49 a 52. Exercises 49– 52. (c) Graph thepara elliptical path and velocity 53. A stone weighing 1 pound is attached to a two-foot stringtabla and del inciso b). t vectors at the values of given in the table in part (b). (c) Graph the elliptical path and the velocity and acceleration (c) under Graph the elliptical path and the velocity and acceleration 53. to Una piedra que pesa 1 libra ata a un de dos pies de will break ispound whirled horizontally (see figure). The string hing 1 pound is attached astone two-foot string 53. A weighing 1and is se attached to acordel two-foot string and d) Usar los resultados de los incisos b) y c) para describir la t vectors at the values of given in the table in part (b). t vectors at the values of given in the table in part (b). (d) Use the results of parts (b) and (c) to describe the geometric largo ywill se hace girar (ver laFind figura). El cordel ahorizontalmente force of 10 pounds. thebreak maximum can izontally (see figure). Theis string break under whirled horizontally (see figure). The string will undersespeed the stonerelación geométrica entre los vectores velocidad y acelerelationship between the velocity and acceleration vectors (d) Use the results of parts (b) and (c) to describe the geometric romperá con una fuerza de 10 libras. Hallar la velocidad máxi(d) Use the results of parts (b) and (c) to describe the geometric attain without breaking the string. Use where F ma, pounds. Find the maximum speed the stone can a force of 10 pounds. Find the maximum speed the stone can ración cuando la rapidez de speed la partícula aumenta cuando 1 the of the particle isyvectors increasing, and when it is between the velocity and acceleration ma la ma, piedra puede alcanzar sinrelationship que se Frompa el where cordel. relationship vectors betweenwhen the velocity and acceleration m 32 .the string. ut breaking the string. attain Useque where Fwithout breaking Use ma, disminuye. 1F 5 ma, donde m 5 1 .d decreasing. when the speed of the particle is increasing, (Usar32 whenand the when speed itofisthe particle is increasing, and when it is m . 32 decreasing. decreasing. 1 lb 1 lb 30 mph 2 ft 1 libra 1 lb 22pies ft CAPSTONE 2 ft Para discusión CAPSTONE 30 mphC60. A P SConsiderar T O N E una60. partícula queaseparticle mueve moving sobre una Consider ontrayectoria an elliptical path described elíptica donde r t onaan d dt is the by coselliptical t i bpath sen described t j, where 60. Consider 30 a particle moving on an elliptical path adescrita described mph 60. Consider particlepor moving es la velocidad constante. constant angular velocity. by r t is the a cos t i b sen t j, whereby r t d dt a cos t i b sen t j, where d dt is the constant angular velocity. constant angular a) Encontrar el velocity. vector velocidad. ¿Cuálvector. es la What rapidez de speed la (a) Find the velocity is the of the particle? partícula? (a) Find the velocity vector. What is the speed of the (a) Find theparticle? velocity(b) vector. is the speed ofvector the particle? FindWhat the acceleration and show that its direction 300 pies b)that Encontrar el vector is aceleración yshow demostrar que suthe direcalwaysand toward the center of ellipse. (b) Find the acceleration vector and show itsthe direction (b) Find acceleration vector that its direction 300ispies está toward siemprethe hacia el centro la elipse. always toward the center of the ellipse. isción always center of the de ellipse. Figure for 53 Figure for 54 Figura para Figura para 54 Figure Figure for 54 for 53 5354. A 3400-pound Figure for 54 automobile is negotiating a circular interchange WRITING ABOUT CONCEPTS deT conceptos Un automóvil de 3 400 libras está una 54. A of radius 300 feet miles hour Assuming d automobile is negotiating a3400-pound circular interchange W tomando R I T at I N30 A Bcurva O Uper Tcircular C O N(see CdeE Pfigure). T S WDesarrollo 54. automobile is negotiating aGcircular interchange R I T I N G A B O U61. CInO Nyour C E Pown T S words, explain the difference between the 300 pies de 30 hora (ver la figura). Supuesto roadway is level, find the force between the tires and the feet at 30 miles per hour of (see figure). Assuming radius 300radio feet aatthe 30millas miles por per hour (see figure). Assuming 61. Con las propias palabras, explicar la diferencia entre velocity of an object and itsbetween speed.la veloexplain the difference the explain the 61. In your own words, difference the 61. In yourbetween own words, queroadway la the carretera estároad nivelada, la fuerza necesaria entre los path that car stays ontires the and circular and does not de un objeto y su rapidez. is level, find the force between tires the the is and level, findsuch the hallar forcethe between the the cidad velocity of an object and its speed. velocity of an object and its speed. 62. What is known about the speed of an object if the angle neumáticos y el pavimento para que el automóvil mantenga la skid. (Use ma, where 32.) Find the angle at t the car stays on the circular notstays road path such and that does the car onFthe circular pathmand 3400 does not 62. ¿Qué se conoce acerca de la rapidez de un objeto si el ángubetween the velocity and acceleration vectors is (a) acute 62. What is known about the speed of an object if the angle 62. What is known about the speed of an object if the angle trayectoria circular sin derrapar. (Usar F 5 ma, donde m 5 the be banked at ma, where m 3400 skid. 32.) Find (Use the where ) Find the angle at so that no lateral F angle ma,which m roadway 3400 32.should lo entre los vectores velocidad y aceleración es a) agudo y and (b) obtuse? between the velocity and acceleration vectors is (a) acute between the velocity and acceleration vectors is (a) acute 3 400/32.) Hallar el ángulo de peralte necesario para que ningufrictional is exerted the no tireslateral of the automobile. oadway should be banked so that no lateral which the roadway should force be banked so onthat b) obtuso? and (b) obtuse? and (b) obtuse? 63. Consider a particle that is moving on the path na de fricción lateral seatires ejercida los neumáticos e is exerted on the tires offrictional thefuerza automobile. force is exerted on the of thesobre automobile. del automóvil. 55. Shot-Put Throw 63. Consider Redacción una x tpartícula y t que j se zon tmueve k.the sobre The pathaof particle a shot thrown angle ison the 63. Consider that atisan moving path r1 t that 63. a Considerar particle isi moving path la trayectoria r s t d 5 x s t d i 1 y s t d j 1 z s t d k. tde unx objeto t ian angle ylanzado t j iszcon t k. ow The path of a shot at anThrow angle is path r t x t i y t j z t k. 55.thrown Lanzamiento de peso La trayectoria 1 55. Shot-Put The of a shotr1thrown at (a) Discuss any changes in the position, velocity, or acceler1 1 2 rt v0 cos (a) t i Discuss h v0 sin t in gt j un ángulo u es a) Analizar todo cambio en la posición, velocidad o aceleation of the particle if its position is given by the vectorany changes the position, velocity, or acceler(a) Discuss any changes in the position, velocity, or acceler1 2 1 2 ti h v0 sin t r t gt2 vj0 cos t i ración de laparticle partícula si su posición está dada por la funh v sin t gt j valued function r t r 2t . ation of the particle if its position is given by the vectoration of the if its position is given by the vector1 0 2 1 2 gt2 j rs2td 5 sv0 cos udt i 1 h 1v svis0 the sin dt 2valued sen uinitial ción vectorial srt2d t5 r1sr2t d. where h is the initial r2 t height, r1 2t .t is the time valued functionr2(b) 0 2speed,function Generalize 1 2t . the results for the position function in seconds, and is the acceleration due to gravity. Verify that g e initial speed, h is the initial height, is the time t where v0 is the initial speed, h is the(b) initial height, t isthe the results time b) Generalize Generalizar los arla posición r3 t for t . position Generalize for the (b) position function the resultados results the function 1 función donde v0 es la rapidez inicial, es la altura inicial, es el tiemthe willh remain air fortVerify a. total of nd g is the acceleration due gravity.and Verify in to seconds, theshot acceleration duerin3totthe gravity. that g isthat r s t d 5 r s v t d . r t r t r t . 3 1 1 po en segundos y g es la aceleración debida a la gravedad. 3 1 emain in the air for a totalthe of shot will remain in the air for a total2 of 2 v0 sin v0 elsin 2gh Verificar que el objeto permanecerá en aire t 2 seconds 64. When t 0, an object is at the point 0, 1 and has a velocity 2 v02 sin2 2gh g v00 sin sen sin sin2 u 1 2gh 2gh sen u 1 !v002 sin seconds t seconds vector 0 i.0, 1It and moves a with an acceleration of 5 seconds segundos t 0, 0, 1 and 64. When an object is at the point has aanvelocity t 0, 64. When object is está at vthe g g 64. Cuando t 5 0, un objeto enpoint el punto (0, 1) yhas tiene velocity un vector and will travel vector a horizontal aoftIt moves sin t i with cos t j.anShow that the path of of the object is a circle. v 0 distance i. of It moves with vector an acceleration v 0 i. acceleration velocidad v(0) 5 2i. Se mueve con aceleración a(t) 5 sen ti 2 l a horizontal distance of and y recorrerá unaa distancia horizontal tde sin t i cos t j. Show that the pathaoft the sin will travel horizontal object circle.Show that the path of the object is a circle. t i is acos v02 cos distancea of 2gh cos t j. Mostrar quet j.la delExercises objeto es un círculo. True ortrayectoria False? In 65–68, determine whether the feet. sin sin2 2 2 2 2gh v00 cos u v g 22 True 2gh 0 2 statement is true or false. If it is false, explain or False? In Exercises 65–68, determine whether the sen sen feet. sin True or False? In Exercises 65–68, determine whether the why or give an pies. sin u 1 sin u 1 feet. v02 v0022 g ¿Verdadero otrue falso? En 65 68,why determinar si la example is afalse. statement true or false. If it is false, why or or give an los statement is false. Ifthat itejercicios isshows false,itexplain or give an 56. Shot-Put Throw A is shot is thrown from a height of explain h 6 feet declaración es verdadera o falsa. Si es falsa, explicar por qué o example that shows it is false. 56. Lanzamiento de peso Un peso es lanzado desde una altura de example that shows it is false. v0 45 with second and at an angle ow A shot is thrown56. fromShot-Put a height Throw of h 6 A feet shotan is initial thrownspeed fromof a height of feet h per 6 feet 65.pruebe The acceleration of an object is the derivative of the speed. dar un ejemplo que que es falsa. pies con rapidez inicial pies por segundo y con h 5 6 v 5 45 ofof v0 42.5 the horizontal. Find the total time of travel 0 with speed of v0 45 feet perwith second and at speed an angle an initial peracceleration second and of at an an object angle 45 feet The derivative of the speed. The acceleration of The an object is the derivative thederivative speed. of the position. 66. velocity of an object isofthe un ángulo de with contotal la65. horizontal. el tiempo total is the 65. uof5travel 42.58 andhorizontal. the horizontal distance traveled. with the horizontal. Find of the total42.5 time the Find theHallar total time of travel 65. La aceleración de un objeto es la derivada de la rapidez. 66. The velocity of an object is the derivative of the position. de recorrido y la distancia horizontal recorrida. 66. The velocity of 67. an object is the derivative of the The velocity vector points inposition. the direction of motion. horizontal distance traveled. and the total horizontal distance 57. Prove that iftraveled. an object is traveling at a constant speed, its 66. The Laofvelocidad de unpoints objetoinesthe la derivada de la posición. 67. The velocity vector points in the direction motion. 57. Demostrar que si un objeto se mueve con rapidez constante, sus 67. velocity vector direction of motion. 68. If a particle moves along a straight line, then the velocity and velocity and acceleration vectors speed, are orthogonal. an object is traveling a constant its is traveling 57.atProve that ifspeed, an object at a constant its 67. El apunta en lavectors dirección de movimiento. vectores and velocidad y aceleración son ortogonales. acceleration orthogonal. Ifobject aorthogonal. particle moves a straight line, then the velocidad velocity acceleration vectors are orthogonal. 68. a vector particle moves and along a straight line,are then the velocity and velocity acceleration 58. Provevectors that68. anare moving in aalong straight line at a Ifconstant acceleration vectors are orthogonal. 68. Si una partícula se mueve a lo largo de una línea recta, entonces 58. Demostrar que un objeto que se mueve en línea recta a velociacceleration vectors are orthogonal. speed has an acceleration of 0. n object moving in a 58. straight line at a constant Prove that an object moving in a straight line at a constant los vectores velocidad y aceleración son ortogonales. dad constante tiene aceleración acceleration of 0. speed has an acceleration of 0. nula. 300 pies 3 1 ! 4 2 12-4.qxd 3/12/09 18:21 Page 859 SECCIÓN 12.4 Vectores tangentes y vectores normales 859 12.4 Vectores tangentes y vectores normales n n Hallar un vector unitario tangente en un punto a una curva en el espacio. Hallar las componentes tangencial y normal de la aceleración. Vectores tangentes y vectores normales En la sección precedente se vio que el vector velocidad apunta en la dirección del movimiento. Esta observación lleva a la definición siguiente, que es válida para cualquier curva suave, no sólo para aquellas en las que el parámetro es el tiempo. DEFINICIÓN DEL VECTOR UNITARIO TANGENTE Sea C una curva suave en un intervalo abierto I, representada por r. El vector unitario tangente Tstd en t se define como Tstd 5 r9std , r9std Þ 0. ir9std i Como se recordará, una curva es suave en un intervalo si r9 es continua y distinta de cero en el intervalo. Por tanto, la “suavidad” es suficiente para garantizar que una curva tenga vector unitario tangente. EJEMPLO 1 Hallar el vector unitario tangente Hallar el vector unitario tangente a la curva dada por rstd 5 ti 1 t 2j cuando t 5 1. y Solución La derivada de rstd es 4 r9std 5 i 1 2t j. 3 Derivada de rstd. Por tanto, el vector unitario tangente es 2 1 −2 −1 x 1 2 r(t) = ti + t 2 j La dirección del vector unitario tangente depende de la orientación de la curva Figura 12.20 r9std ir9std i 1 5 si 1 2tjd. !1 1 4t 2 Tstd 5 T(1) Definición de Tstd. Sustituir r9std. Cuando t 5 1, el vector unitario tangente es Ts1d 5 1 si 1 2jd !5 como se muestra en la figura 12.20. NOTA En el ejemplo 1, hay que observar que la dirección del vector unitario tangente depende de la orientación de la curva. Por ejemplo, si la parábola de la figura 12.20 estuviera dada por rstd 5 2 st 2 2di 1 st 2 2d 2j, aunque Ts1d también representaría el vector unitario tangente en el punto s1, 1d, apuntaría en dirección opuesta. Tratar de verificar esto. n 12-4.qxd 3/12/09 860 18:21 Page 860 CAPÍTULO 12 Funciones vectoriales La recta tangente a una curva en un punto es la recta que pasa por el punto y es paralela al vector unitario tangente. En el ejemplo 2 se usa el vector unitario tangente para hallar la recta tangente a una hélice en un punto. Hallar la recta tangente a una curva en un punto EJEMPLO 2 Hallar Tstd y hallar después un conjunto de ecuaciones paramétricas para la recta tangente a la hélice dada por rstd 5 2 cos t i 1 2 sen sin t j 1 tk 1 en el punto !2, !2, Tstd 5 z 5 6 C T Recta tangente −3 ( 2, 2, π 4 3 ) La recta tangente a una curva en un punto está determinada por el vector unitario tangente en el punto Figura 12.21 r9std ir9std i 1 !5 s22 sen sin t i 1 2 cos tj 1 kd. Vector unitario tangente. En el punto s!2,!2, py4d, t 5 py4 y el vector unitario tangente es 5 x 2 sin t i 1 2 cos t j 1 k, lo que implica que Solución La derivada de rstd es r9std 5 22 sen ir9std i 5 !4 sen sin22 t 1 4 cos2 t 1 1 5 !5. Por consiguiente, el vector unitario tangente es Curva: r(t) = 2 cos ti + 2 sen tj + tk 3 p . 4 y 1p4 2 5 !15 122 22 i 1 2 22 j 1 k2 ! 5 1 !5 ! s2 !2 i 1 !2 j 1 kd. Usando los números directores a 5 2 !2, b 5 !2, y c 5 1, y el punto (x1, y1, z1) 5 s!2, !2, py4d, se obtienen las ecuaciones paramétricas siguientes (dadas con el parámetro s). x 5 x1 1 as 5 !2 2 !2s y 5 y1 1 bs 5 !2 1 !2s z 5 z1 1 cs 5 p 1s 4 Esta recta tangente se muestra en la figura 12.21. En el ejemplo 2 hay una cantidad infinita de vectores que son ortogonales al vector tangente Tstd. Uno de estos vectores es el vector T9std. Esto se desprende de la propiedad 7 del teorema 12.2. Es decir, Tstd ? Tstd 5 i Tstd i 2 5 1 Tstd ? T9std 5 0. Normalizando el vector T9std, se obtiene un vector especial llamado el vector unitario normal principal, como se indica en la definición siguiente. DEFINICIÓN DE VECTOR UNITARIO NORMAL PRINCIPAL Sea C una curva suave en un intervalo abierto I representada por r. Si T9std Þ 0, entonces el vector unitario normal principal en t se define como Nstd 5 T9std . iT9std i 12-4.qxd 3/12/09 18:21 Page 861 SECCIÓN 12.4 EJEMPLO 3 Vectores tangentes y vectores normales 861 Hallar el vector unitario normal principal Hallar Nstd y Ns1d para la curva representada por rstd 5 3t i 1 2t 2j. Solución Derivando, se obtiene r9std 5 3i 1 4tj y ir9std i 5 !9 1 16t2 lo que implica que el vector unitario tangente es Tstd 5 5 r9std ir9std i 1 !9 1 16t2 s3i 1 4tjd. Vector unitario tangente. Usando el teorema 12.2, se deriva Tstd con respecto a t para obtener y 3 Curva: r(t) = 3ti + 2t2j T9std 5 C 5 N(1) = 15 (−4i + 3j) 1 !9 1 16t2 16t s3i 1 4tjd s9 1 16t 2d3y2 12 s24ti 1 3jd s9 1 16t 2d3y2 ! iT9std i 5 12 2 s4jd 2 9 1 16t 2 12 5 . s9 1 16t 2d 3 9 1 16t 2 Por tanto, el vector unitario normal principal es 1 T(1) = 15 (3i + 4j) Nstd 5 x 1 2 3 El vector unitario normal principal apunta hacia el lado cóncavo de la curva Figura 12.22 5 T9std iT9std i 1 !9 1 16t 2 s24ti 1 3jd. Vector unitario normal principal. Cuando t 5 1, el vector unitario normal principal es 1 Ns1d 5 s24i 1 3jd 5 como se muestra en la figura 12.22. z El vector unitario normal principal puede ser difícil de evaluar algebraicamente. En curvas planas, se puede simplificar el álgebra hallando C Tstd 5 xstdi 1 ystdj T x N y observando que Nstd debe ser y En todo punto de una curva, un vector unitario normal es ortogonal al vector unitario tangente. El vector unitario normal principal apunta hacia la dirección en que gira la curva Figura 12.23 Vector unitario tangente. N1std 5 ystdi 2 xstdj o N2std 5 2ystdi 1 xstdj. Como !fxstdg2 1 f ystdg2 5 1, se sigue que tanto N1std como N 2std son vectores unitarios normales. El vector unitario normal principal N es el que apunta hacia el lado cóncavo de la curva, como se muestra en la figura 12.22 (véase ejercicio 94). Esto también es válido para curvas en el espacio. Es decir, si un objeto se mueve a lo largo de la curva C en el espacio, el vector Tstd apunta hacia la dirección en la que se mueve el objeto, mientras que el vector Nstd es ortogonal a Tstd y apunta hacia la dirección en que gira el objeto, como se muestra en la figura 12.23. 12-4.qxd 3/12/09 862 18:21 Page 862 CAPÍTULO 12 Funciones vectoriales Hallar el vector unitario normal principal EJEMPLO 4 Hélice: r(t) = 2 cos ti + 2 sen tj + tk Hallar el vector unitario normal principal para la hélice dada por rstd 5 2 cos t i 1 2 sin sen t j 1 tk. z Solución De acuerdo con el ejemplo 2, se sabe que el vector unitario tangente es 2π Tstd 5 3π 2 T9std 5 −2 −1 1 1 2 y N std es horizontal y apunta hacia el eje z Figura 12.24 1 !5 s22 cos t i 2 2 sen sin t jd. T9std iT9std i 1 5 s22 cos t i 2 2 sen sin t jd 2 5 2cos t i 2 sen sin t j. Nstd 5 −1 x Vector unitario tangente. Como iT9std i 5 2y!5, se sigue que el vector unitario normal principal es π 2 2 s22 sin sen t i 1 2 cos tj 1 kd. Así, T9std está dado por π −2 1 !5 Vector unitario normal principal. Nótese que este vector es horizontal y apunta hacia el eje z, como se muestra en la figura 12.24. Componentes tangencial y normal de la aceleración Ahora se vuelve al problema de describir el movimiento de un objeto a lo largo de una curva. En la sección anterior, se vio que si un objeto se mueve con rapidez constante, los vectores velocidad y aceleración son perpendiculares. Esto parece razonable, porque la rapidez no sería constante si alguna aceleración actuara en dirección del movimiento. Esta afirmación se puede verificar observando que r0 std ? r9std 5 0 si ir9std i es una constante. (Ver la propiedad 7 del teorema 12.2.) Sin embargo, si un objeto viaja con rapidez variable, los vectores velocidad y aceleración no necesariamente son perpendiculares. Por ejemplo, se vio que en un proyectil el vector aceleración siempre apunta hacia abajo, sin importar la dirección del movimiento. En general, parte de la aceleración (la componente tangencial) actúa en la línea del movimiento y otra parte (la componente normal) actúa perpendicular a la línea del movimiento. Para determinar estas dos componentes, se pueden usar los vectores unitarios Tstd y Nstd, que juegan un papel análogo a i y j cuando se representan los vectores en el plano. El teorema siguiente establece que el vector aceleración se encuentra en el plano determinado por Tstd y Nstd. TEOREMA 12.4 VECTOR ACELERACIÓN Si rstd es el vector posición de una curva suave C y Nstd existe, entonces el vector aceleración astd se encuentra en el plano determinado por Tstd y Nstd. 12-4.qxd 3/12/09 18:21 Page 863 SECCIÓN 12.4 Vectores tangentes y vectores normales 863 Demostración Para simplificar la notación, se escribe T en lugar de Tstd, T9 en lugar de T9std, y así sucesivamente. Como T 5 r9yir9 i 5 vyivi, se sigue que v 5 iviT. Por derivación, se obtiene a 5 v9 5 Dt fivigT 1 iviT9 5 Dt fivigT 1 iviT9 Regla del producto. 1iTiT99 ii2 5 Dt fivig T 1 ivi i T9 i N. N 5 T9yi T9 i Como a se expresa mediante una combinación lineal de T y N, se sigue que a está en el plano determinado por T y N. A los coeficientes de T y de N en la demostración del teorema 12.4 se les conoce como componentes tangencial y normal de la aceleración y se denotan por aT 5 Dt fivig y aN 5 i vi iT9 i. Por tanto, se puede escribir astd 5 aTTstd 1 aNNstd. El teorema siguiente da algunas fórmulas útiles para aN y a T. TEOREMA 12.5 COMPONENTES TANGENCIAL Y NORMAL DE LA ACELERACIÓN Si rstd es el vector posición de una curva suave C [para la cual Nstd existe], entonces las componentes tangencial y normal de la aceleración son las siguientes. v?a ivi iv 3 ai aN 5 i vi iT9 i 5 a ? N 5 5 !iai2 2 a T2 ivi aT 5 Dt fivig 5 a ? T 5 Nótese que aN ≥ 0. A la componente normal de la aceleración también se le llama componente centrípeta de la aceleración. a a•T>0 T N a•N T a•N N a a•T<0 DEMOSTRACIÓN Nótese que a se encuentra en el plano de T y N. Por tanto, se puede usar la figura 12.25 para concluir que, en cualquier instante t, las componentes de la proyección del vector aceleración sobre T y sobre N están dadas por aT 5 a ? T, y aN 5 a ? N., respectivamente. Además, como a 5 v9 y T 5 vyivi, se tiene aT 5 a ? T 5T?a v 5 ?a ivi v?a 5 . ivi En los ejercicios 96 y 97 se pide demostrar las otras partes del teorema. Las componentes tangencial y normal de la aceleración se obtienen proyectando a sobre T y N. Figura 12.25 NOTA Las fórmulas del teorema 12.5, junto con algunas otras fórmulas de este capítulo, se resumen en la página 877. n 12-4.qxd 3/12/09 864 18:21 Page 864 CAPÍTULO 12 Funciones vectoriales EJEMPLO 5 Componentes tangencial y normal de la aceleración Hallar las componentes tangencial y normal de la aceleración para el vector posición dado por rstd 5 3t i 2 tj 1 t 2 k. Solución Para empezar se halla la velocidad, la rapidez y la aceleración. vstd 5 r9std 5 3i 2 j 1 2tk ivstd i 5 !9 1 1 1 4t 2 5 !10 1 4t 2 astd 5 r0 std 5 2k De acuerdo con el teorema 12.5, la componente tangencial de la aceleración es aT 5 v?a 4t 5 ivi !10 1 4t 2 | | y como v 3 Componente tangencial de la aceleración. i a5 3 0 j 21 0 k 2t 5 22i 2 6j 2 la componente normal de la aceleración es aN 5 NOTA !4 1 36 iv 3 ai 2!10 5 5 . 2 ivi !10 1 4t !10 1 4t 2 Componente normal de la aceleración. En el ejemplo 5 se podría haber usado la fórmula alternativa siguiente para a N. a N 5 !i a i 2 2 a T2 5 EJEMPLO 6 !s2d 2 2 16t 2 2!10 5 10 1 4t 2 !10 1 4t 2 n Hallar a T y a N para una hélice circular Hallar las componentes tangencial y normal de la aceleración para la hélice dada por rstd 5 b cos t i 1 b sen sin t j 1 ctk, b > 0. Solución vstd 5 r9std 5 2b sen sin t i 1 b cos t j 1 ck aN = b z ivstd i 5 !b 2 sen sin22 t 1 b 2 cos2 t 1 c2 5 !b 2 1 c 2 astd 5 r0 std 5 2b cos t i 2 b sen sin t j b De acuerdo con el teorema 12.5, la componente tangencial de la aceleración es aT 5 y x La componente normal de la aceleración es igual al radio del cilindro alrededor del cual la hélice gira en espiral Figura 12.26 v ? a b2 sen sin t cos t 2 b 2 sen sin t cos t 1 0 5 5 0. ivi !b 2 1 c 2 Componente tangencial de la aceleración. Como iai 5 !b2 cos2 t 1 b2 sen sin22 t 5 b, se puede usar la fórmula alternativa para la componente normal de la aceleración para obtener aN 5 !iai 2 2 aT2 5 !b2 2 02 5 b. Componente normal de la aceleración. Nótese que la componente normal de la aceleración es igual a la magnitud de la aceleración. En otras palabras, puesto que la rapidez es constante, la aceleración es perpendicular a la velocidad. Ver la figura 12.26. 12-4.qxd 3/12/09 18:21 Page 865 SECCIÓN 12.4 r(t) = (50 2t)i + (50 865 Movimiento de un proyectil EJEMPLO 7 2t − 16t 2)j Vectores tangentes y vectores normales y El vector posición para el proyectil mostrado en la figura 12.27 está dado por rstd 5 s50!2 tdi 1 s50!2 t 2 16t2dj. 100 75 50 t= t=1 Hallar la componente tangencial de la aceleración cuando t 5 0, 1 y 25!2y16. 25 2 16 25 t=0 Vector posición. Solución vstd 5 50!2 i 1 s50!2 2 32td j ivstd i 5 2!50 2 2 16s50d!2t 1 16 2t 2 astd 5 232j x 25 50 75 100 125 150 La trayectoria de un proyectil Figura 12.27 Vector velocidad. Velocidad. Vector aceleración. La componente tangencial de la aceleración es vstd ? astd 232s50!2 2 32td 5 . ivstd i 2!502 2 16s50d!2t 1 162t 2 En los instantes especificados, se tiene Componente tangencial de la aceleración. aTstd 5 232s50!2 d 5 216!2 < 222.6 100 232s50!2 2 32d a T s1d 5 < 215.4 2!50 2 2 16s50d!2 1 16 2 a T s0d 5 aT 12516 22 5 232s50502 22 50 ! ! !2 ! d 5 0. En la figura 12.27 se puede ver que, a la altura máxima, cuando t 5 25!2y16, la componente tangencial es 0. Esto es razonable porque en ese punto la dirección del movimiento es horizontal y la componente tangencial de la aceleración es igual a la componente horizontal de la aceleración. 12.4 Ejercicios En los ejercicios 1 a 4, dibujar el vector unitario tangente y los vectores normales a los puntos dados. y 1. 2. En los ejercicios 5 a 10, hallar el vector unitario tangente a la curva en el valor especificado del parámetro. 5. rstd 5 t 2 i 1 2tj, t 5 1 y 6. rstd 5 t3 i 1 2t 2j, t51 p 7. rstd 5 4 cos ti 1 4 sen sin tj, t 5 4 8. rstd 5 6 cos ti 1 2 sen sin tj, t5 p 3 9. rstd 5 3t i 2 ln t j, t 5 e x x 3. y 4. 10. rstd 5 et cos ti 1 etj, t 5 0 En los ejercicios 11 a 16, hallar el vector unitario tangente Tstd y hallar un conjunto de ecuaciones paramétricas para la recta tangente a la curva en el espacio en el punto P. y 11. rstd 5 t i 1 t 2j 1 tk, Ps0, 0, 0d x x 4 4 12. rstd 5 t 2 i 1 tj 1 3 k, Ps1, 1, 3 d sin tj 1 t k, Ps3, 0, 0d 13. rstd 5 3 cos t i 1 3 sen 14. rstd 5 k t, t, !4 2 t2 l, Ps1, 1, !3 d sin t, 4l, Ps!2, !2, 4d 15. rstd 5 k2 cos t, 2 sen sin t, 2 cos t, 4 sen sin2 tl, Ps1, !3, 1d 16. rstd 5 k2 sen 12-4.qxd 3/12/09 1053714_1204.qxp 866 18:21 Page 866 10/27/08 11:49 AM CAPÍTULO 12 Page 866 Funciones vectoriales 866 Chapter 12 Vector-Valued Functions En los ejercicios 17 y 18, usar un sistema algebraico por computadora para representar la gráfica de la curva en el espacio. conjunto de ecuaciones de CAS Después hallar Txtc y un use a computer algebra paramétricas system to graph latherecta a la find curva el find espacio punto P. spacetangente curve. Then a setenofelparametric T tenand Representar la the gráfica la rectatotangente. equations for linede tangent the space curve at point P. Graph thekt,tangent line. Ps3, 9, 18d 17. rstd 5 t2, 2t3y3l, CAS senPt j3,19,12 18 18. cos i1 t k, Ps0, 4, py4d 3 34 ,sin 17. rrstdt 5 3 t, t2,t2t 1 18. r t 3 cos t i 4 sin t j 2 t k, P 0, 4, 4 Aproximación lineal En los ejercicios 19 y 20, hallar un conjunto de ecuaciones paramétricas para la Linear Approximation In Exercises 19recta and tangente 20, find aa lasetgráof fica en y utilizar las ecuaciones de la recta para t 5 t 0 parametric equations for the tangent line to the graph at taprot0 ximar rxtthe 0.1c. 0 1equations and use for the line to approximate r t 1 0.1 . 19. rstd 5 k t, ln t, !t l, t0 5 1 19. r t t, ln t, t , t0 1 sen tl, t0 5 0 20. rstd 5 ke2t, 2 cos t, 2 sin 20. r t e t, 2 cos t, 2 sin t , t0 0 0 En los ejercicios 21 y 22, verificar que las curvas en el espacio se In Exercises 21 and 22, verify that the space curves intersect at cortan en los valores dados de los parámetros. Hallar el ángulo the given values of the parameters. Find the angle between the entre los vectores tangentes a las curvas en el punto de intersectangent vectors to the curves at the point of intersection. ción. 21. rrstdt 5 k t t2 2,2,t2t2, ,1212tlt , , t t5 44 21. 1 33 ss , , ss5 88 2s,! uusssd 5 k 144s,s,2s, l 22. r t t, cos t, sin t , t t5 00 sen 22. rstd 5 kt, cos t, sin tl, k 1 sin22ss2 sen sins,s,112 1212sen sin22ss2 uusssd 5 2 122sen sin sin sin 11 11 sinsscos cosss1 22ss , , ss5 00 sin 22sen sins,s, sen sin l In Exercises 23 –30, principalelunit normal vectornormal to the En los ejercicios 23 find a 30,the encontrar vector unitario curve at the specified value of the parameter. principal a la curva en el valor especificado del parámetro. 1 23. 23. rrstdt 5 titi1 212t 2t 2j,j, t t5 22 66 24. 24. rrstdt 5 titi1 t j,j, t t5 33 t r s t d 5 ln t i 1 25. 25. r t ln t i st t1 11d j,j, t t5 22 26. 26. rr tt cos costtii sen sen tj, tj, tt 39. rstd 5 et i 1 e22t j, t 5 0 rstd 5 rt rstd 5 rt rstd 5 rrsttd 5 et i 1 e2t j 1 t k, t 5 0 et i e t j t k, t 0 p et cos t i 1 et sen sin t j, t 5 2 et cos t i et sin t j, t 2 0 a cos vt i 1 b sen sin vt j, t 5 akcos cosvt t1 i vtbsin sinvt,t j, t t 20 vt cos vtl, t 5 t sin sen v sen 0 r t cos t t sin t, sin t , t t0 43. sin vt, 1 2 cos vtl,t t 5t cos t0 44. rstd 5 kvt 2 sen t sin t, 1 cos t , t t 0 44. r t 40. 40. 41. 41. 42. 42. 43. Movimiento circular En los ejercicios 45 a 48, considerar un Circular Motion In Exercises 45– 48, consider an object objeto que se mueve según la función de posición moving according to the position function rxtc 5 a cos vt i 1 a sen sin vt j. rt a cos t i 1 a sin t j. 45. Hallar Tstd, Nstd, a T , y a N. 45. Find T t , N t , a T , and a N. 46. Determinar las direcciones de T y N en relación con la función 46. Determine the directions of T and N relative to the position de posición r. function r. 47. Determinar la rapidez del objeto en cualquier instante t y 47. Determine the speed of the object at any time t and explain its explicar su valor en relación con el valor de a T . value relative to the value of a T . 48. Si la velocidad angular v se reduce a la mitad, ¿en qué factor 48. If the angular velocity is halved, by what factor is a N cambia a N? changed? En los ejercicios 49 sketch a 54, dibujar la gráfica de la curve curva given plana In Exercises 49–54, the graph of the plane dada por la función vectorial, y, en el punto sobre la curva deterby the vector-valued function, and, at the point on the curve minada por by los vectores T y N. Observar que N rxt0rc, tdibujar determined 0 , sketch the vectors T and N. Note that N apunta hacia el lado cóncavo deoflathe curva. points toward the concave side curve. Función Function Instante Time 11 49. 49. rrsttd 5 tt ii 1 t jj t tt0 5 22 0 3 50. tj 50. rrsttd 5 tt3 ii 1 tj 66 27. 27. rrstdt 5 t ti i1 t2t2jj1 lnlnt tk,k, t t5 11 t k, t 5 0 28. 28. rrstdt 5 !2t 2ti i1 eet jt j1 ee2t k, t 0 3p 3 29. sen 29. rrstdt 5 66cos cost ti i1 66sin sentjtj1 k,k, t t5 4 4 30. cos 30. rr tt cos 3t 3tii 22 sen sen 3t 3tjj k, k, tt In Exercises 31–34, find v t , a t , T t , and N t (if it exists) for En los ejercicios 31 a 34, hallar vxtc, axtc, Txtc y Nxtc (si existe) an object moving along the path given by the vector-valued para un objeto que se mueve a lo largo de la trayectoria dada por function r t . Use the results to determine the form of the path. la función vectorial rxtc. Usar los resultados para determinar la Is the speed of the object constant or changing? forma de la trayectoria. ¿Es constante la rapidez del objeto o cambiante? 31. r t 32. r t 4t i 4t i 2t j 31. 32. 33. rrstdt 5 4t4ti2 i 34. rrstdt 5 4tt 2ij 2 2t kj 33. rstd 5 4t 2 i 34. rstd 5 t 2 j 1 k In Exercises 35 – 44, find T t , N t , a T , and a N at the given time plane curve t for En losthe ejercicios 35 a r44,t .hallar Txtc, Nxtc, a T , y a N para la curva plana t en el instante rxtc. 1 35. r t 36. r t t2 i 2t j, t 1 ti j, t 1 1t 35. rstd 5 t i 1 j, t 5 1 36. rstd 5 t2 i 1 2tj, t 5 1 t tt3 i 2t2j, t 1 37. r t 2 2 t 5 1 3 t3d4t r s t d 5 s t i1 37. t2 i 2t j, t 1 j, t 0 38. r t 3 2 38. 39. rrstdt 5 stet i2 4tedi 2t1j, st t 2 10dj, t 5 0 51. r(t) r(t) 51. 4ti 4ti 4t22jj 4t t) 52. rr t) 52. 2t 2t 1)i 1)i tt0 5 11 0 11 tt00 4 4 2 tt2jj 22 p t00 5 4 t00 5 p tt00 sin tj 53. rstd 5 2 cos t i 1 2 sen sin t j 54. rstd 5 3 cos t i 1 2 sen t ,NT t x, tac,TN , and In Exercises 55– 62, time xtc, aaTNyataNthe engiven el instante En los ejercicios 55 afind 62, Thallar t for the t . [Hint: a t , T t , aHallar space curve respacial dado rxtcFind . [ Sugerencia: t para la curva T(t) y T, and axNt.c,Solve aT T 1 aaxNtcN.5] a T 1 a N. ] N in the equation a t afor N. Resolver para N en la ecuación T N Function Función 55. rstd 5 t i 1 2t j 2 3t k 56. rstd 5 4t i 2 4t j 1 2t k 57. r t) 58. r t) 59. r t cos ti 3ti ti sen tj Time Instante t51 t52 t 2tk 3 tj t2k t t 2j t2 k 2 t 1 t 2 t 0 t 0 1i t2j 60. r t) 2t 61. r t t e sen t i e t cos t j 62. r t) et i tk 2tj e 4tk et k 1 1053714_1204.qxp 10/27/08 11:50 AM Page 867 1053714_1204.qxp 10/27/08 12-4.qxd 3/12/09 18:21 11:50 Page AM 867 Page 867 1053714_1204.qxp 10/27/08 11:50 AM Page 867 1053714_1204.qxp 10/27/08 11:50 AM Page 867 SECCIÓN 12.4 12.4 12.4 12.4 CAS ejercicios 66, ausar un sistema algebraico porgraph compuCAS En In los Exercises 63 –63 66,y use computer algebra system to the CAS CAS CAS In Exercises 63 – 66, use a computer algebra system to graph the tadora y representar gráficamente curva Entonces space curve. Then find at the to given time t. T t , N t , a Tla , and a espacial. In Exercises 63 – 66, use graph space curve. Then find and aNNsystem at the given timethe t. Tatcomputer , N t , a T ,algebra hallar y en el instante dado Dibujar y Nxtt.c Tcurve. xTtc,tNand xThen tc, aN a t. T xtctime Sketch on the space curve. t space find and at the given T t , N t , a , a N T N Sketch T t and NT t on the space curve. In Exercises 63el– 66, computer algebra system to graph the en la curva espacio. Sketch and onathe space curve. T t en N t use Function Timegiven time t. space curve. Then find T t , N t , a T , and aN atTime the Function Función Instante Function Time Sketch T t and N t on the space curve. 63. r t 4t i 3 cos t j 3 sen t k t 63. r t 4t i 3 cos t j 3 sen t k t 2 Time 63. Function rt 4t i 3 cos t j 3 sen t k t 2 2 t 64. r t 2 cos t i 1 sen t j t k t 64. t i t j 1 3 sen sent kt j 3k t 63. r t 4t2 i cos 3 cos t 64. r t 2 cos t i 1 sen t j 3 k t 2 2 3 2t 2 t t i 3t2 j t 2 65. r t k t 2 65. r t t 2i 3t 64. cosj t i t2k1 sen t j k t 2 t i2 3t 2 j 2 k t 2 65. r t 3 66. r t t i j 2tk t 1 t2 i j 2tkt 22 66. r t t 1 2 2 i j 2tk 66. r t t t t i 3t j t 21 65. r t k 2 CONCEPTS W R I T I N G A B O U T WRITING ABOUT CONCEPTS 66. rRtIDefine t 1unit normal W T I Nt2Gi the A jBde O U2tk Tconceptos C O N Cvector, E P T Sthe principal Desarrollo 67. unit tangent 67. Define the unit tangent vector, the principal unit normal vector, the andunit thetangent tangential andthenormal components of 67. Definir Define vector, principal unit normal tangential components of 67. el vector unitario normal W R Ivector, Tacceleration. I N G eland Avector B Othe U Tunitario C O N Ctangente, E Pand T S normal vector, and the tangential and normal components of acceleration. principal, y las componentes tangencial y normal de la ace67. the principal unit normalof acceleration. 68. Define How isthe theunit unit tangent tangent vector, vector related to the orientation 68. leración. How is the unit tangent vectorand related to the orientation of of vector, and the tangential normal components a curve? Explain. 68. ¿Cuál isesthe tangent vector relatedunitario to the orientation aHow curve? Explain. 68. la unit relación entre el vector tangente y of la acceleration. a(a) curve? Explain. 69.orientación Describe the motion ofExplicar. a particle if the normal component dethe una curva? 69. (a) Describe motion of a particle if the normal component 68. How of is acceleration the unit tangent to the orientation of is 0.vector related 69. a) (a)Describir Describe themovimiento motion the normal of acceleration is 0. of a particle 69. el de una ifpartícula si component la compoa curve? Explain. of acceleration is 0. (b)nente Describe the motion of a particle if the tangential normal de la aceleración es 0. Describe the themotion motion a particle if the component tangential 69. (b) (a) Describe of aof particle componentthe of motion acceleration isparticle 0.if the normal (b) component Describe of a if the tangential acceleration 0. partícula si la compob) Describir el of movimiento deisuna of acceleration is 0. component of acceleration is 0. es 0. nente tangencial de la aceleración (b) Describe the motion of a particle if the tangential of acceleration is 0. C A P S Tcomponent ONE CAPSTONE C70. A PAn S Tobject O N E moves along the path given by 70. An discusión object moves along the path given by Para 70. An object moves along the path given by r t O N3ti 4tj. C70. A PUn E se 4tj. rSt Tobjeto 3ti mueve a lo largo de la trayectoria dada por r t object 3ti 4tj. along the path given by 70. An Find v t , moves a t , T t , and N t (if it exists). What is the form Find t , a1t 4tj. , T t , and N t (if it exists). What is the form r(t) 5v 3ti of the path? Is, T the speed of tthe object constant or changing? Find v t , a t4tj. , andof N it exists). What the form r tthe path? 3ti Is of the tspeed the(if object constant or is changing? of the path? Is the the (si object constant Encontrar v(t), a(t)speed T(t) yofN(t) existe). ¿Cuáloreschanging? la forma Find t , a t , T t ¿Es , andconstante N t (if ito exists). is the form de la vtrayectoria? variableWhat la velocidad del of the path? Is the speed the object or changing? objeto? 71. Cycloidal Motion The of figure showsconstant the path of a particle 71. Cycloidal Motion The figure shows the path of a particle modeled by the vector-valued function 71. modeled Cycloidal The figure shows the path of a particle byMotion the vector-valued function modeled by the vector-valued function t sen The t, 1 cos shows t . the path of a particle rt tMotion sen t, 1Lafigure cos tmuestra . rCycloidal t 71. Movimiento cicloidal figura la trayectoria de una t sen t, 1 cos t r t modeled by the vector-valued function partícula representada funciónv. vectorial The figure also showspor thelavectors t v t and a t a t at The figure also shows the vectors v t v t and a t a t at the indicated values t. vectors The figuret also shows t indicated sen t,of1t.the cos t v. t v t and a t a t at rthe values of the indicated values of t. y y figura std iayt astdayit astatd i La también los vectores The figuremuestra also shows the vectors and v t vvsttdyiv y en valoresvalues indicados thelos indicated of t.de t. y y t=1 t = 12 2 t = 1 t = 12 t = 1 t=1 t= 1t 2 = 1 t2 = 1t = 1 t=3 t = 3232 t= 2 3 t = 32t = 2 x x x x x 1 1, and t 3. 1 2, t 1, and t 323.2 21, t t 1,ofand 2. the2,speed the tparticle (a) Find a and a at t (a) Find aTTand aNNat t (a) a T andwhether a N at t (b) Find Determine is increasing or (b) Determine whether the speed of the particle is increasing or decreasing whether at each of indicated values ofist. increasing Give reasons 1 the 3particle (b) Determine the speed of the or 1 3 decreasing at each of the indicated values of Give reasons t. a) y aNaNenatt t5 2,2,t t5 11,y and t 5 t2. 2. (a) Hallar Find aaTTand for your answers. decreasing at each of the indicated values of Give reasons t. forcada your answers. b) de los the valores de t, determinar (b) En Determine whether speedindicados of the particle is increasingsiorla for youruno answers. rapidez de la partícula o values disminuye. Dar reasons razones decreasing at each of theaumenta indicated of t. Give para las respuestas. for your answers. 867 867 867 867 VectoresVectors tangentes y vectores Tangent and Normal normales Vectors Tangent Vectors and Normal Vectors Tangent Vectors and Normal Vectors 12.4 Along Tangent Vectors and 867 72. a loanlargo de una un La fi72. Movimiento Motion Involute ofinvoluta aNormal CircledeVectors Thecírculo figure shows 72. Motion Along an Involute of a Circle The figure shows gura muestra una partícula que sigue la trayectoria dada por a particle moving along a pathThe modeled by 72. aMotion Along an Involute of a Circle figure shows particle moving along a path modeled by cos t t sen t, sen ta path t cos t . The figure rt by sen t t cos t modeled . The figure ra t particle cos t moving t sen t,along 72. Motion Along Involute of vectores also shows the an vectors and for t tdThe v t t,los aa t Circle 1 and tpara2.shows sen rLa t figura cos t sen asttfigure 51y muestra también also shows thet vectors v t and a t tfor t vtscos 1 yand td. The 2. tfigure aalso along afor tpath1 and modeled y shows the moving vectors and v t a t t 2. by t 5 particle 2. y t cos t . The figure rt cos t y t sen t, sen t y also shows the vectors v t and a t for t 1 and t 2. y t=1 t=1 tt = = 11 x x x x t=1 t=2 t=2 tt = = 22 x (a) Find a and a at t 1 and t 2. (a) Find a TTand aNt N=at2 t 1 and t 2. (a) Find and a at t the 2. particle is increasing or aaTTand (b)Hallar Determine of the a) y awhether 11yspeed t 5t 2. N Nen t 5 (b) Determine whether the speed of the particle is increasing or decreasing at each of the indicated values ofist.increasing Giveoreasons (b) Determine whether the speed of the particle or b) Determinar la rapidez de tla partícula aumenta dismidecreasing atsiaeach of the indicated t. Give reasons (a) Find a T and 1 and 2.values of N at t for your answers. decreasing at each of the indicated values of Give reasons t. nuye en cada uno de los valores indicados de t. Dar razones for your answers. (b) para Determine whether the speed of the particle is increasing or for your answers. las respuestas. In Exercises 73–78, find the vectors Tvalues and of N,t. and the unit decreasing at each thevectors indicated Givethe reasons In Exercises 73–78, findofthe T and N, and unit binormal vector for the vector-valued function B T N, rt for your answers. In Exercises 73–78, find the vectors T and N, and the unit En los ejercicios 73 a 78, T y N, yfunction el vectorrunibinormal vector B thevectores vector-valued T hallar N, forlos t at thebinormal given value of t.T binormal the vector-valued rt tario la función vectorial rxfunction BB 5 tc en el valor at the givenvector value of T t. 3 N,N,defor In Exercises 73–78, find the vectors T and N, and the unit at the given dado de t. value of t. t3 t vector-valued function binormal 73. r t vector t i 2t 2 j t33r kt 2 cos B ti T 2 senN,t jfort the k 74. r t 73. 74. j r t t i t r t 2 cos t i 2 sen t j k t3k t2 at 73.ther given t 2value cos t iof t.2 sen t j 2 k 74. rstd 5 t i 1 t 2j 1 3 k 2 3 t t 1 t3 t 73. rt 0 t0 p22 cos t i 2 sen t j k 74. rt0 0t 1 t i t 2 j k 2 3 t0 5 2 t0 5 1 z 2z t0 z z 4 42 43z 3 3 4 t0 −1 −1 −11 − 1 1 1 1z 1 1 1 1 1 2 3 3 x3 x 33 x z z 3 3 3 y y y 2 2 x x 1 x 2 2 2 2 2 y y y y Figure for 73 Figure for 74 3 y 3 Figure for 73 Figure for 74 x x − 1 7373 Figure for Figure for Figura para Figura para7474 75. r t i sen t j cos t k, t0 75. r t for i73 sen t j cos t k, t0 Figure 4 Figure for 74 75. r t i sen t j cos t k, t0 4 76. r t 2et t i et t cos t j et t sen t k,4 t0 0 76. r t 2e ti e tcos t j e tsen t k, t0 0 75. t0 t k, t0 0 i2e isen et jcos cos 76. rr tt t j t k,e sen 77. r t 4 sen t i 4 cos t j 2t k, 4 t0 77. r t 4 sen t i 4 cos t j 2t k, t0 3 76. 2e i t ei t cos4 tcos j t jet sen 77. rr tt 4 tsen 2t tk,k, t0t0 30 3 78. r t 3 cos 2t i 3 sen 2t j t k, t0 78. r t cos 2t sent j2t j 2t k, t k, t t0 4 77. 43 sen t i i 43cos 78. r t 3 cos 2t i 3 sen 2t j t k, 0 t0 34 4 79. Projectile Motion Find the tangential and normal compo79. Find normal compo78. rProjectile t 3 cosMotion 2tdei un3 proyectil sen 2tthe j tangential tHallar k, t0 las and Movimiento componentes tangen79. nents of acceleration for a the projectile fired 4at an normal angle with the 79. nents Projectile Motion Find tangential compoof acceleration for a projectile fired atand an angle with theun cial y normal de la aceleración de un proyectil disparado con horizontal at an initial speed of v0. fired Whatatare the components nents of acceleration for a projectile an angle with the horizontal at an initial speed of vrapidez are thev components 0. Whatinicial ángulo u con la horizontal ymaximum con ¿Cuáles son 79. Projectile Motion Find the tangential and compowhen the projectile is atspeed its height? horizontal at an initial of v0. What are normal the0.components when the projectile is at its maximum height? las componentes cuando el proyectil está en su altura máxima? nents of acceleration for a projectile fired at an angle with the the projectile at its maximum height? 80. when Projectile Motion isUse your results from Exercise 79 to find 80. Projectile Motion Usespeed your of results from Exercise 79 find horizontal at de an and initial v0. What are the components 80. Movimiento un proyectil Utilizar losof resultados delto ejercithe tangential normal components acceleration for a 80. the Projectile Motion Use your results from Exercise 79 tofor find tangential and normal components of acceleration ala when thepara projectile atcomponentes its maximum height? cio 79 hallar las y normal for de an projectile fired at is an angle of 45 tangencial with theacceleration horizontal at the tangential and normal components of a projectile fired at proyectil an angle disparado of 45 with horizontal at an aceleración deofun conthe un ángulo de to 45° con 80. Projectile Motion Use results from Exercise 79 initial speed 150an feetyour per of second. What are the components projectile at 45 What with the horizontal atfind an initial speedfired of con 150 feetangle per second. arepies the components la horizontal rapidez inicial de 150 por segundo. the tangential and normal of are acceleration for a when the projectile is at per itscomponents maximum height? initial speed of 150 feet second. What the components when the projectile is at its maximum height? ¿Cuáles cuando elthe proyectil está atenansu projectile firedlasatcomponentes anis angle of 45 with horizontal when theson projectile at its maximum height? altura speed máxima? initial of 150 feet per second. What are the components when the projectile is at its maximum height? 12-4.qxd 3/12/09 868 18:21 Page 868 CAPÍTULO 12 Funciones vectoriales 81. Movimiento de un proyectil Un proyectil se lanza con velocidad inicial de 120 pies por segundo desde 5 pies de altura y con un ángulo de 30° con la horizontal. a) Determinar la función vectorial de la trayectoria del proyectil. b) Usar una herramienta de graficación para representar la trayectoria y aproximar la altura máxima y el alcance del proyectil. c) Hallar vstd, i vstd i, y astd. d) Usar una herramienta de graficación para completar la tabla. t 0.5 1.0 1.5 2.0 2.5 3.0 Velocidad e) Usar una herramienta de graficación para representar las funciones escalares a T y aN. ¿Cómo cambia la velocidad del proyectil cuando a T y aN tienen signos opuestos? 82. Movimiento de un proyectil Un proyectil se lanza con velocidad inicial de 220 pies por segundo desde una altura de 4 pies y con un ángulo de 45° con la horizontal. a) Determinar la función vectorial de la trayectoria del proyectil. b) Usar una herramienta de graficación para representar la trayectoria y aproximar la altura máxima y el alcance del proyectil. c) Hallar vstd, i vstd i, y astd. d) Usar una herramienta de graficación para completar la tabla. t 0.5 1.0 1.5 2.0 2.5 3.0 Velocidad 83. Control del tráfico aéreo Debido a una tormenta, los controladores aéreos en tierra indican a un piloto que vuela a una altitud de 4 millas que efectúe un giro de 90° y ascienda a una altitud de 4.2 millas. El modelo de la trayectoria del avión durante esta maniobra es rstd 5 k10 cos 10p t, 10 sen sin 10p t, 4 1 4tl, 0 ≤ t ≤ 1 20 donde t es el tiempo en horas y r es la distancia en millas. a) Determinar la rapidez del avión. CAS b) Usar un sistema algebraico por computadora y calcular a T y a N. ¿Por qué una de éstas es igual a 0? 84. Movimiento de un proyectil Un avión volando a una altitud de 36 000 pies con rapidez de 600 millas por hora deja caer una bomba. Hallar las componentes tangencial y normal de la aceleración que actúan sobre la bomba. 85. Aceleración centrípeta Un objeto, atado al extremo de una cuerda, gira con rapidez constante, de acuerdo con la función de posición dada en los ejercicios 45 a 48. a) Si la velocidad angular v se duplica, ¿cómo se modifica la componente centrípeta de la aceleración? b) Si la velocidad angular no se modifica pero la longitud de la cuerda se reduce a la mitad, ¿cómo cambia la componente centrípeta de la aceleración? 86. Fuerza centrípeta Un objeto de masa m se mueve con rapidez constante v siguiendo una trayectoria circular de radio r. La fuerza requerida para producir la componente centrípeta de la aceleración se llama fuerza centrípeta y está dada por F 5 mv 2yr. La ley de Newton de la gravitación universal establece que F 5 GMmyd 2, donde d es la distancia entre los centros de los dos cuerpos de masas M y m, y G es una constante gravitatoria. Usar esta ley para mostrar que la rapidez requerida para el movimiento circular es v 5 !GMyr. Velocidad orbital En los ejercicios 87 a 90, usar el resultado del ejercicio 86 para hallar la rapidez necesaria para la órbita circular dada alrededor de la Tierra. Tomar GM 5 9.56 3 104 millas cúbicas por segundo al cuadrado, y suponer que el radio de la Tierra es 4 000 millas. 87. La órbita de un transbordador espacial que viaja a 115 millas sobre la superficie de la Tierra. 88. La órbita de un transbordador espacial que viaja a 245 millas sobre la superficie de la Tierra. 89. La órbita de un satélite de detección térmica que viaja a 385 millas sobre la superficie de la Tierra. 90. La órbita de un satélite de comunicación que está en órbita geosíncrona a r millas sobre la superficie de la Tierra. [El satélite realiza una órbita por día sideral (aproximadamente 23 horas, 56 minutos) y, por consiguiente, parece permanecer estacionario sobre un punto en la Tierra.] ¿Verdadero o falso? En los ejercicios 91 y 92, determinar si la declaración es verdadera o falsa. Si es falsa, explicar por qué o dar un ejemplo que muestre que es falsa. 91. Si el indicador de velocidad de un automóvil es constante, entonces el automóvil no puede estar acelerando. 92. Si aN 5 0 en un objeto en movimiento, entonces el objeto se mueve en una línea recta. 93. Una partícula sigue una trayectoria dada por r(t) 5 cosh(bt)i 1 senh(bt)j donde b es una constante positiva. a) Mostrar que la trayectoria de la partícula es una hipérbola. b) Mostrar que astd 5 b2 rstd. 94. Mostrar que el vector unitario normal principal N apunta hacia el lado cóncavo de una curva plana. 95. Mostrar que en un objeto que se mueve en línea recta el vector T9std es 0. iv 3 ai 96. Mostrar que aN 5 . ivi 97. Mostrar que aN 5 !iai2 2 aT2. Preparación del examen Putnam 98. Una partícula de masa unitaria se mueve en línea recta bajo la acción de una fuerza que es función f svd de la velocidad v de la partícula, pero no se conoce la forma de esta función. Se observa el movimiento y se encuentra que la distancia x recorrida en el tiempo t está relacionada con t por medio de la fórmula x 5 at 1 bt2 1 ct3, donde a, b y c tienen valores numéricos determinados por la observación del movimiento. Hallar la función f svd para el rango de v cubierto en el experimento. Este problema fue preparado por el Committee on the Putnam Prize Competition. © The Mathematical Association of America. Todos los derechos reservados. 12-5.qxd 3/12/09 18:22 Page 869 SECCIÓN 12.5 Longitud de arco y curvatura 869 12.5 Longitud de arco y curvatura n n n n Calcular la longitud de arco de una curva en el espacio. Utilizar el parámetro de longitud de arco para describir una curva plana o curva en el espacio. Calcular la curvatura de una curva en un punto en la curva. Utilizar una función vectorial para calcular la fuerza de rozamiento. Longitud de arco En la sección 10.3 se vio que la longitud de arco de una curva plana suave C dada por las ecuaciones paramétricas x 5 xstd y y 5 ystd, a ≤ t ≤ b, es EXPLORACIÓN Fórmula para la longitud de arco La fórmula para la longitud de arco de una curva en el espacio está dada en términos de las ecuaciones paramétricas que se usan para representar la curva. ¿Significa esto que la longitud de arco de la curva depende del parámetro que se use? ¿Sería deseable que fuera así? Explicar el razonamiento. Ésta es una representación paramétrica diferente de la curva del ejemplo 1. rstd 5 t 2 i 1 E b s5 !fx9stdg 2 1 f y9stdg 2 dt. a En forma vectorial, donde C está dada por rstd 5 xstdi 1 ystdj, se puede expresar esta ecuación de la longitud de arco como E b s5 ir9std i dt. a La fórmula para la longitud de arco de una curva plana tiene una extensión natural a una curva suave en el espacio, como se establece en el teorema siguiente. TEOREMA 12.6 LONGITUD DE ARCO DE UNA CURVA EN EL ESPACIO Si C es una curva suave dada por rstd 5 xstdi 1 ystdj 1 zstdk, en un intervalo fa, bg, entonces la longitud de arco de C en el intervalo es 4 3 1 t j 1 t4 k 3 2 E b Hallar la longitud de arco desde t 5 0 hasta t 5 !2 y comparar el resultado con el encontrado en el ejemplo 1. s5 a EJEMPLO 1 z Hallar la longitud de arco de una curva en el espacio Hallar la longitud de arco de la curva dada por r(t) = ti + 43t 3/2 j + 12t 2 k 2 C Solución Utilizando xstd 5 t, ystd 5 43 t 3y2, y zstd 5 12 t 2, se obtiene x9std 5 1, y¢(t) = 2t1/2 y z9std 5 t. Por tanto, la longitud de arco desde t 5 0 hasta t 5 2 está dada por t=2 1 2 −1 3 4 A medida que t crece de 0 a 2, el vector rst d traza una curva Figura 12.28 4 3y2 1 t j 1 t2k 3 2 desde t 5 0 hasta t 5 2, como se muestra en la figura 12.28. 1 x ir9std i dt. a rstd 5 t i 1 t=0 E b !fx9stdg 2 1 f y9stdg 2 1 fz9stdg 2 dt 5 y E E E 2 s5 !fx9stdg 2 1 f y9stdg 2 1 fz9stdg 2 dt Fórmula para longitud de arco. 0 2 5 !1 1 4 t 1 t 2 dt 0 2 5 !st 1 2d2 2 3 dt Tablas de integración (apéndice B), fórmula 26. 0 3 t 12 2 !st 1 2d |4 0 3 ln st 1 2d 1 !st 1 2d2 2 3 2 3 3 5 2!13 2 lns4 1 !13 d 2 1 1 ln 3 < 4.816. 2 2 5 2 232 | 2 12-5.qxd 3/12/09 870 18:22 Page 870 CAPÍTULO 12 Funciones vectoriales EJEMPLO 2 Curva: r(t) = b cos ti + b sen tj + Hallar la longitud de arco de una hélice 1 − b2 tk Hallar la longitud de un giro de la hélice dada por z rstd 5 b cos ti 1 b sen sin t j 1 !1 2 b 2 t k t = 2π como se muestra en la figura 12.29. Solución Se comienza hallando la derivada. sen ti 1 b cos tj 1 !1 2 b 2 k r9std 5 2b sin C Derivada. Ahora, usando la fórmula para la longitud de arco, se puede encontrar la longitud de un giro de la hélice integrando ir9stdi desde 0 hasta 2p. s5 5 t=0 b b y 5 E E E 2p 0 2p ir9std i dt Fórmula para la longitud de arco. !b 2ssin sen22 t 1 cos2 td 1 s1 2 b 2d dt 0 2p dt 0 x 4 5t Un giro de la hélice Figura 12.29 2p 0 5 2p. Por tanto, la longitud es 2p unidades. Parámetro longitud de arco s(t) = ∫ t [x′(u)]2 + [y′(u)]2 + [z′(u)]2 du a z t=b C t Se ha visto que las curvas pueden representarse por medio de funciones vectoriales de maneras diferentes, dependiendo del parámetro que se elija. Para el movimiento a lo largo de una curva, el parámetro adecuado es el tiempo t. Sin embargo, cuando se desean estudiar las propiedades geométricas de una curva, el parámetro adecuado es a menudo la longitud de arco s. DEFINICIÓN DE LA FUNCIÓN LONGITUD DE ARCO Sea C una curva suave dada por rstd definida en el intervalo cerrado fa, bg. Para a ≤ t ≤ b, la función longitud de arco está dada por t=a y E t sstd 5 a x E t ir9sud i du 5 !fx9sudg 2 1 f y9sudg 2 1 fz9sudg 2 du. a A la longitud de arco s se le llama parámetro longitud de arco. (Ver la figura 12.30.) Figura 12.30 NOTA La función de longitud de arco s es no negativa. Mide la distancia sobre C desde el punto inicial sxsad, ysad, zsadd hasta el punto sxstd, ystd, zstdd. n Usando la definición de la función longitud de arco y el segundo teorema fundamental de cálculo, se concluye que ds 5 ir9std i. dt En la forma diferencial, se escribe ds 5 ir9std i dt. Derivada de la función longitud de arco. 12-5.qxd 3/12/09 18:22 Page 871 SECCIÓN 12.5 Longitud de arco y curvatura 871 Hallar la función longitud de arco para una recta EJEMPLO 3 Hallar la función longitud de arco sstd para el segmento de recta dado por y rstd 5 s3 2 3tdi 1 4t j, 0 ≤ t ≤ 1 r(t) = (3 − 3t)i + 4tj 4 y expresar r como función del parámetro s. (Ver la figura 12.31.) 0≤t≤1 3 Solución Como r9std 5 23i 1 4j y 2 ir9stdi 5 !s23d2 1 42 5 5 se tiene 1 E E t x 1 2 3 El segmento de recta desde (3, 0) hasta (0, 4) puede parametrizarse usando el parámetro longitud de arco s. Figura 12.31 sstd 5 ir9sudi du 0 t 5 5 du 0 5 5t. Usando s 5 5t (o t 5 sy5), se puede reescribir r utilizando el parámetro longitud de arco como sigue. rssd 5 s3 2 35sdi 1 45s j, 0 ≤ s ≤ 5. Una de las ventajas de escribir una función vectorial en términos del parámetro longitud de arco es que ir9ssdi 5 1. De este modo, en el ejemplo 3, se tiene ir9ssdi 5 !12 532 1 1452 2 2 5 1. Así, dada una curva suave C representada por r(sd, donde s es el parámetro longitud de arco, la longitud de arco entre a y b es E E b Lengthdeofarco arc 5 Longitud ir9ssdi ds a b 5 ds a 5b2a 5 longitud length ofdel interval. intervalo. Además, si t es cualquier parámetro tal que ir9stdi 5 1, entonces t debe ser el parámetro longitud de arco. Estos resultados se resumen en el teorema siguiente que se presenta sin demostración. TEOREMA 12.7 PARÁMETRO LONGITUD DE ARCO Si C es una curva suave dada por rssd 5 xssdi 1 yssdj o rssd 5 xssdi 1 yssdj 1 zssdk donde s es el parámetro longitud de arco, entonces ir9ssdi 5 1. Si t es cualquier parámetro para la función vectorial r tal que ir9stdi 5 1, entonces t debe ser el parámetro longitud de arco. 12-5.qxd 3/12/09 872 18:22 Page 872 CAPÍTULO 12 Funciones vectoriales Curvatura y Q C P x La curvatura en P es mayor que en Q. Un uso importante del parámetro longitud de arco es hallar la curvatura, la medida de cuán agudamente se dobla una curva. Por ejemplo, en la figura 12.32 la curva se dobla más agudamente en P que en Q, y se dice que la curvatura es mayor en P que en Q. Se puede hallar la curvatura calculando la magnitud de la tasa o ritmo de cambio del vector unitario tangente T con respecto a la longitud de arco s, como se muestra en la figura 12.33. DEFINICIÓN DE CURVATURA Figura 12.32 Sea C una curva suave (en el plano o en el espacio) dada por rssd, donde s es el parámetro longitud de arco. La curvatura K en s está dada por y T2 Q T3 C K5 T1 i ddsT i 5 iT9ssdi. P x La magnitud de la tasa o del ritmo de cambio de T respecto a la longitud de arco es la curvatura de una curva Un círculo tiene la misma curvatura en todos sus puntos. La curvatura y el radio del círculo están relacionados inversamente. Es decir, un círculo con un radio grande tiene una curvatura pequeña, y un círculo con un radio pequeño tiene una curvatura grande. Esta relación inversa se explica en el ejemplo siguiente. EJEMPLO 4 Figura 12.33 y Mostrar que la curvatura de un círculo de radio r es K 5 1yr. K = 1r T Solución Sin pérdida de generalidad, se puede considerar que el círculo está centrado en el origen. Sea sx, yd cualquier punto en el círculo y sea s la longitud de arco desde sr, 0d hasta sx, yd, como se muestra en la figura 12.34. Denotando por u el ángulo central del círculo, puede representarse el círculo por (x, y) r θ s (r, 0) Hallar la curvatura de un círculo x rsud 5 r cos u i 1 r sen sin u j. u es el parámetro. Usando la fórmula para la longitud de un arco circular s 5 ru, se puede reescribir rsud en términos del parámetro longitud de arco como sigue. La curvatura de un círculo es constante Figura 12.34 s s rssd 5 r cos i 1 r sen sin j r r La longitud de arco s es el parámetro. s s sen i 1 cos j, de donde se sigue que ir9ssdi 5 1, lo que implica que el Así, r9ssd 5 2sin r r vector unitario tangente es Tssd 5 r9ssd s s 5 2sin sen i 1 cos j ir9ssd i r r y la curvatura está dada por K 5 iT9ssd i 5 s 1 sin j i 5 i 2 1r cos sr i 2 1r sen r r en todo punto del círculo. NOTA Puesto que una recta no se curva, se esperaría que su curvatura fuera 0. Tratar de comprobar esto hallando la curvatura de la recta dada por 1 rssd 5 3 2 2 3 4 s i 1 sj. 5 5 n 12-5.qxd 3/12/09 18:22 Page 873 SECCIÓN 12.5 T(t) Longitud de arco y curvatura 873 En el ejemplo 4, la curvatura se encontró aplicando directamente la definición. Esto requiere que la curva se exprese en términos del parámetro longitud de arco s. El teorema siguiente da otras dos fórmulas para encontrar la curvatura de una curva expresada en términos de un parámetro arbitrario t. La demostración de este teorema se deja como ejercicio [ver ejercicio 100, incisos a) y b)]. ∆T T(t + ∆t) T(t) ∆s C TEOREMA 12.8 FÓRMULAS PARA LA CURVATURA Si C es una curva suave dada por rstd, entonces la curvatura K de C en t está dada por K5 iT9stdi ir9std 3 r0 std i 5 . ir9std i ir9std i3 T(t) ∆s C T(t) ∆T T(t + ∆t) Como ir9std i 5 dsydt, la primera fórmula implica que la curvatura es el cociente de la tasa o ritmo de cambio del vector tangente T entre la tasa o ritmo de cambio de la longitud de arco. Para ver que esto es razonable, sea Dt un número “pequeño”. Entonces, T9std fTst 1 Dtd 2 TstdgyDt Tst 1 Dtd 2 Tstd DT < 5 5 . dsydt fsst 1 Dtd 2 sstdgyDt sst 1 Dtd 2 sstd Ds En otras palabras, para un Ds dado, cuanto mayor sea la longitud de DT, la curva se dobla más en t, como se muestra en la figura 12.35. Figura 12.35 EJEMPLO 5 Hallar la curvatura de una curva en el espacio 1 Hallar la curvatura de la curva definida por rstd 5 2t i 1 t 2j 2 3 t 3k. Solución No se sabe a simple vista si este parámetro representa la longitud de arco, así es que hay que usar la fórmula K 5 iT9std iyir9std i. r9std 5 2i 1 2t j 2 t 2k ir9std i 5 !4 1 4t 2 1 t 4 5 t 2 1 2 Tstd 5 T9std 5 5 iT9std i 5 5 5 Longitud de r9std. r9std 2i 1 2t j 2 t 2k 5 ir9std i t2 1 2 st 2 1 2ds2j 2 2tkd 2 s2tds2i 1 2t j 2 t 2 kd st 2 1 2d2 24t i 1 s4 2 2t 2dj 2 4tk st 2 1 2d2 !16t 2 1 16 2 16t 2 1 4t 4 1 16t 2 st 2 1 2d2 2st 2 1 2d st 2 1 2d2 t2 2 12 Longitud de T9std. Por tanto, K5 iT9std i 2 5 2 . ir9std i st 1 2d2 Curvatura. 12-5.qxd 3/12/09 874 18:22 Page 874 CAPÍTULO 12 Funciones vectoriales El teorema siguiente presenta una fórmula para calcular la curvatura de una curva plana dada por y 5 f sxd. TEOREMA 12.9 CURVATURA EN COORDENADAS RECTANGULARES Si C es la gráfica de una función dos veces derivable y 5 f sxd, entonces la curvatura K en el punto sx, yd está dada por K5 |y0 | . f1 1 s y9 d2g 3y2 Si se representa la curva C por rsxd 5 xi 1 f sxdj 1 0k (donde x es el parámetro), se obtiene r9sxd 5 i 1 f9sxdj, DEMOSTRACIÓN ir9sxd i 5 !1 1 f f9sxdg 2 y r0 sxd 5 f 0 sxdj. Como r9sxd 3 r0 sxd 5 f 0 sxdk, se sigue que la curvatura es ir9sxd 3 r0 sxd i ir9sxd i3 f 0 sxd 5 H1 1 f f9sxdg 2J 3y2 y0 5 . f1 1 s y9 d2g 3y2 K5 | y r = radio de curvatura | | K = 1r P r x Centro de curvatura C El círculo de curvatura Figura 12.36 Sea C una curva con curvatura K en el punto P. El círculo que pasa por el punto P de radio r 5 1yK se denomina el círculo de curvatura si su centro se encuentra en el lado cóncavo de la curva y tiene en común con la curva una recta tangente en el punto P. Al radio se le llama el radio de curvatura en P, y al centro se le llama el centro de curvatura. El círculo de curvatura permite estimar gráficamente la curvatura K en un punto P de una curva. Usando un compás, se puede trazar un círculo contra el lado cóncavo de la curva en el punto P, como se muestra en la figura 12.36. Si el círculo tiene radio r, se puede estimar que la curvatura es K 5 1yr. EJEMPLO 6 y=x Solución La curvatura en x 5 2 se calcula como sigue: P(2, 1) 1 Q(4, 0) x 1 −1 2 (2, −1) y9 5 1 2 3 y0 5 2 −2 K5 −3 −4 r= 1 =2 K El círculo de curvatura Figura 12.37 Hallar la curvatura en coordenadas rectangulares Hallar la curvatura de la parábola dada por y 5 x 2 14x 2 en x 5 2. Dibujar el círculo de curvatura en s2, 1d. − 14 x 2 y −1 | 1 2 x 2 |y0 | f1 1 s y9 d2g 3y2 y9 5 0 y0 5 2 K5 1 2 1 2 Como la curvatura en Ps2, 1d es 12, el radio del círculo de curvatura en ese punto es 2. Por tanto, el centro de curvatura es s2, 21d, como se muestra en la figura 12.37. [En la figura, obsérvese que la curva tiene la mayor curvatura en P. Trate de mostrar que la curvatura en Qs4, 0d es 1y25y2 < 0.177.] 12-5.qxd 3/12/09 18:22 Page 875 SECCIÓN 12.5 La fuerza del empuje lateral que perciben los pasajeros en un automóvil que toma una curva depende de dos factores: la rapidez del automóvil y lo brusco de la curva Figura 12.38 Longitud de arco y curvatura 875 La longitud de arco y la curvatura están estrechamente relacionadas con las componentes tangencial y normal de la aceleración. La componente tangencial de la aceleración es la tasa o ritmo de cambio de la rapidez, que a su vez es la tasa o ritmo de cambio de la longitud de arco. Esta componente es negativa cuando un objeto en movimiento reduce su velocidad y positiva cuando la aumenta, independientemente de si el objeto gira o viaja en una recta. En consecuencia, la componente tangencial es solamente función de la longitud de arco y es independiente de la curvatura. Por otro lado, la componente normal de la aceleración es función tanto de la rapidez como de la curvatura. Esta componente mide la aceleración que actúa perpendicular a la dirección del movimiento. Para ver por qué afectan la rapidez y la curvatura a la componente normal, imaginarse conduciendo un automóvil por una curva, como se muestra en la figura 12.38. Si la velocidad es alta y la curva muy cerrada, se sentirá empujado contra la puerta del automóvil. Al bajar la velocidad o tomar una curva más suave, se disminuye este efecto de empuje lateral. El teorema siguiente establece explícitamente la relación entre rapidez, curvatura y componentes de la aceleración. TEOREMA 12.10 ACELERACIÓN, RAPIDEZ Y CURVATURA Si rstd es el vector posición de una curva suave C, entonces el vector aceleración está dado por NOTA El teorema 12.10 da fórmulas adicionales para aT y aN. n astd 5 1 2 d 2s ds 2 T 1 K dt dt 2 N donde K es la curvatura de C y dsydt es la rapidez. Para el vector posición rstd, se tiene DEMOSTRACIÓN astd 5 aTT 1 aNN 5 Dt fivigT 1 ivi iT9 iN d 2s ds 5 2 T 1 siviKdN dt dt d 2s ds 2 5 2T1K N. dt dt 1 2 EJEMPLO 7 Componentes tangencial y normal de la aceleración Hallar aT y aN de la curva dada por rstd 5 2t i 1 t 2j 2 13 t 3k. Solución Por el ejemplo 5, se sabe que ds 5 ir9std i 5 t 2 1 2 y dt K5 2 . st 2 1 2d2 Por tanto, aT 5 d 2s 5 2t dt 2 Componente tangencial. y aN 5 K 1dsdt2 2 5 2 st 2 1 2d2 5 2. st 2 1 2d2 Componente normal. 12-5.qxd 3/12/09 876 18:22 Page 876 CAPÍTULO 12 Funciones vectoriales Aplicación Hay muchas aplicaciones prácticas en física e ingeniería dinámica en las que se emplean las relaciones entre rapidez, longitud de arco, curvatura y aceleración. Una de estas aplicaciones se refiere a la fuerza de fricción o de rozamiento. Un objeto de masa m en movimiento está en contacto con un objeto estacionario. La fuerza requerida para producir una aceleración a a lo largo de una trayectoria dada es F 5 ma 5 m 1ddt s2T 1 mK1dsdt2 N 2 2 2 5 maTT 1 maNN. La porción de esta fuerza que es proporcionada por el objeto estacionario se llama fuerza de fricción o de rozamiento. Por ejemplo, si un automóvil se mueve con rapidez constante tomando una curva, la carretera ejerce una fuerza de fricción o rozamiento que impide que el automóvil salga de la carretera. Si el automóvil no se desliza, la fuerza de fricción es perpendicular a la dirección del movimiento y su magnitud es igual a la componente normal de la aceleración, como se muestra en la figura 12.39. La fuerza de rozamiento (o de fricción) potencial de una carretera en una curva puede incrementarse peraltando la carretera. Fuerza de fricción La fuerza de fricción es perpendicular a la dirección del movimiento Figura 12.39 EJEMPLO 8 60 km/h Fuerza de fricción Un coche de carreras (kart) de 360 kilogramos viaja a una velocidad de 60 kilómetros por hora por una pista circular de 12 metros de radio, como se muestra en la figura 12.40. ¿Qué fuerza de fricción (o rozamiento) debe ejercer la superficie en los neumáticos para impedir que el coche salga de su curso? Solución La fuerza de fricción o rozamiento debe ser igual a la masa por la componente normal de aceleración. En el caso de esta pista circular, se sabe que la curvatura es 12 m K5 1 . 12 Curvatura de la pista circular. Por consiguiente, la fuerza de fricción es maN 5 mK 1dsdt2 2 5 s360 kgd Figura 12.40 m 1121m2160,000 3 600sec s 2 3600 < 88333 333 s(kg kgds)(m md)ysec ys2. 2. 2 12-5.qxd 3/12/09 18:22 Page 877 SECCIÓN 12.5 Longitud de arco y curvatura 877 Resumen sobre velocidad, aceleración y curvatura Sea C una curva (en el plano o en el espacio) dada por la función de posición rstd 5 xstdi 1 ystdj rstd 5 xstdi 1 ystdj 1 zstdk. Curva en el plano. Curva en el espacio. vstd 5 r9std ds ivstd i 5 5 ir9std i dt astd 5 r0 std 5 a TTstd 1 aNNstd Vector velocidad, rapidez y vector aceleración: r9std ir9std i Vector unitario tangente y vector unitario normal principal: Tstd 5 Componentes de la aceleración: aT 5 a ? T 5 y Nstd 5 Vector velocidad. Rapidez. Vector aceleración. T9std iT9std i v ? a d 2s 5 2 ivi dt iv 3 ai ds aN 5 a ? N 5 5 !iai2 2 aT2 5 K ivi dt 1 2 |y0 | f1 1 s y9 d2g 3y2 x9y0 2 y9x0 | K5 | 2 fsx9 d 1 s y9 d2g 3y2 Fórmulas para la curvatura en el plano: K5 Fórmulas para la curvatura en el plano o en el espacio: 2 C dada por y 5 f sxd. C dada por x 5 xstd, y 5 ystd. K 5 iT9ssd i 5 ir0ssd i iT9std i ir9std 3 r0 std i K5 5 ir9std i ir9std i3 astd ? Nstd K5 ivstd i 2 s es el parámetro longitud de arco. t es el parámetro general. Las fórmulas con productos vectoriales aplican sólo a curvas en el espacio. 12.5 Ejercicios En los ejercicios 1 a 6, dibujar la curva plana y hallar su longitud en el intervalo dado. 1. r t ti 3t j, 0, 4 2. r t ti t 2j, 0, 4 3. r t t3 i t2 j, 0, 2 4. r t t 1i t2 j, cos3 5. r t a 6. r t a cos t i ti a sen 3 t j, a sen t j, 8. Movimiento de un proyectil Un objeto se lanza desde el nivel del suelo. Determinar el ángulo del lanzamiento para obtener a) la altura máxima, b) el alcance máximo y c) la longitud máxima de la trayectoria. En el inciso c), tomar v0 5 96 pies por segundo. 0, 6 0, 2 0, 2 En los ejercicios 9 a 14, dibujar la curva en el espacio y hallar su longitud sobre el intervalo dado. Función Intervalo 7. Movimiento de un proyectil Una pelota de béisbol es golpeada desde 3 pies sobre el nivel del suelo a 100 pies por segundo y con un ángulo de 45° con respecto al nivel del suelo. 10. r t a) Hallar la función vectorial de la trayectoria de la pelota de béisbol. 11. r t 4t, b) Hallar la altura máxima. 12. r t 2 sen t, 5t, 2 cos t c) Hallar el alcance. 13. r t a cos t i a sen t j 14. r t cos t t sen t, sen t d) Hallar la longitud de arco de la trayectoria. 9. r t ti 4t j t2j i 3t k 0, 1 t3 k 0, 2 cos t, sen t 0, 3 2 0, bt k t cos t, t 2 0, 2 0, 2 12-5.qxd 3/12/09 878 18:22 Page 878 CAPÍTULO 12 Funciones vectoriales En los ejercicios 15 y 16, usar las funciones de integración de una herramienta de graficación para aproximar la longitud de la curva en el espacio sobre el intervalo dado. Función 27. r t ti 1 j, t 28. r t ti 1 3 t j, 9 Intervalo 15. rstd 5 t 2 i 1 t j 1 ln t k 1 ≤ t ≤ 3 sin p t i 1 cos p t j 1 t k 16. rstd 5 sen t 1 t 2 29. r t t, sen t , 30. r t 5 cos t, 4 sen t , t 2 0 ≤ t ≤ 2 3 17. Investigación Considerar la gráfica de la función vectorial rstd 5 t i 1 s4 2 t 2dj 1 t3 k en el intervalo f0, 2g. t 3 En los ejercicios 31 a 40, hallar la curvatura K de la curva. a) Aproximar la longitud de la curva hallando la longitud del segmento de recta que une sus extremos. 31. rstd 5 4 cos 2p t i 1 4 sen sin 2p t j b) Aproximar la longitud de la curva sumando las longitudes de los segmentos de recta que unen los extremos de los vectores rs0d, rs0.5d, rs1d, rs1.5d, y rs2d. sen v t j 33. rstd 5 a cos v t i 1 a sin c) Describir cómo obtener una estimación más exacta mediante los procesos de los incisos a) y b). d) Usar las funciones de integración de una herramienta de graficación para aproximar la longitud de la curva. Comparar este resultado con las respuestas de los incisos a) y b). 18. Investigación Repetir el ejercicio 17 con la función vectorial rstd 5 6 cossp ty4d i 1 2 sen sinsp ty4d j 1 t k. 19. Investigación Considerar la hélice representada por la función vectorial rstd 5 k2 cos t, 2 sin sen t, tl. a) Expresar la longitud de arco s de la hélice como función de t evaluando la integral E t s5 0 !fx9sudg2 1 f y9sudg2 1 fz9sudg 2 du. b) Despejar t en la relación deducida en el inciso a), y sustituir el resultado en el conjunto de ecuaciones paramétricas original. Esto da una parametrización de la curva en términos del parámetro longitud de arco s. c) Hallar las coordenadas del punto en la hélice con longitud de arco s 5 !5 y s 5 4. d) Verificar que ir9ssdi 5 1. sen t 2 t cos td, 4scos t 1 t sen rstd 5 k 4ssin sin td, 32 t2l. En los ejercicios 21 a 24, hallar la curvatura K de la curva donde s es el parámetro longitud de arco. 1 !2 2 2 1 s i1 12 sen v t j 34. rstd 5 a cos v t i 1 b sin sen vtd, as1 2 cos vtdl 35. rstd 5 kasvt 2 sin sen vt 2 vt cos vtl sin vt, sin 36. rstd 5 kcos vt 1 vt sen 37. rstd 5 t i 1 t 2 j 1 !2 2 2 s j 22. rssd 5 s3 1 sdi 1 j sin t, tl 23. La hélice del ejercicio 19: rstd 5 k2 cos t, 2 sen t2 k 2 1 38. rstd 5 2t 2 i 1 tj 1 t 2 k 2 sen t k 39. rstd 5 4t i 1 3 cos t j 1 3 sin e2t i 40. r t e2t cos t j e2t sen tk En los ejercicios 41 a 44, encontrar la curvatura K de la curva en el punto P. 41. r t 3ti 2t2j, 42. r t et i 4tj, P 1, 0 43. r t ti 44. r t et cos ti P 3, 2 t3 k, 4 t2j P 2, 4, 2 et sen tj 45. y 5 3x 2 2, x5a 49. y cos 2x, x a2 51. y 53. y x 5 21 2 x 2, x 3 x, x 0 2 En los ejercicios 25 a 30, hallar la curvatura K de la curva plana en el valor dado del parámetro. 25. rstd 5 4t i 2 2t j, t 5 1 t 2i j, t 2 26. r t P 1, 0, 1 46. y 5 mx 1 b, x 5 a 4 48. y 5 2x 1 , x 5 1 x 50. y e3x, x 0 3 4 52. y x 2, 16 n 54. y x, x 1, x n 0 2 Redacción En los ejercicios 55 y 56, se dan dos círculos de curvatura de la gráfica de la función. a) Hallar la ecuación del círculo menor, y b) escribir un párrafo corto que explique por qué los círculos tienen radios diferentes. 55. f sxd 5 sen sin x 56. f sxd 5 4x 2ysx 2 1 3d y y 24. La curva del ejercicio 20: rstd 5 k 4ssen sin t 2 t cos td, 4scos t 1 t sen sin td, 32 t 2l et k, En los ejercicios 45 a 54, hallar la curvatura y el radio de curvatura de la curva plana en el valor dado de x. 47. y 5 2x 2 1 3, 20. Investigación Repetir el ejercicio 19 con la curva representada por la función vectorial 21. rssd 5 1 1 32. rstd 5 2 cos p t i 1 sin sen p t j 3 2 6 (π2 , 1) π −2 −3 ( −π3 , − 23 ) 4 (3, 3) x x (0, 0) −4 −6 2 4 6 8 12-5.qxd 3/12/09 18:22 Page 879 SECCIÓN 12.5 En los ejercicios 57 a 60, usar una herramienta de graficación para representar la función. En la misma pantalla, representar el círculo de curvatura de la gráfica en el valor dado de x. 1 57. y 5 x 1 , x 59. y 5 e x, x51 x50 58. y 5 ln x, 60. y 5 x3, 77. Dada una función dos veces derivable y 5 f sxd, determinar su curvatura en un extremo relativo. ¿Puede la curvatura tener valores mayores que los que alcanza en un extremo relativo? ¿Por qué sí o por qué no? x51 Evoluta Un evoluta es la curva formada por el conjunto de centros de curvatura de una curva. En los ejercicios 61 y 62 se dan una curva y su evoluta. Usar un compás para trazar los círculos de curvatura con centros en los puntos A y B. x 5 t 2 sen sin t 61. Cicloide: Para discusión 78. Una partícula se mueve a lo largo de la curva plana C descrita por r(t) 5 ti 1 t2j. a) Encontrar la longitud de C en el intervalo 0 # t # 2. y y 5 1 2 cos t b) Encontrar la curvatura K de la curva plana en t 5 0, t 5 1 y t 5 2. π x 5 sen sin t 1 t Evoluta: y 5 cos t 2 1 π c) Describir la curvatura de C cuando t varía desde t 5 0 hasta t 5 2. x B 79. En la elipse dada por x 2 1 4y 2 5 4., mostrar que la curvatura es mayor en los puntos terminales del eje mayor, y es menor en los puntos terminales del eje menor. A −π x 5 3 cos t 62. Elipse: y y 5 2 sen sin t 80. Investigación Hallar todos los a y b tales que las dos curvas dadas por x y1 5 axsb 2 xd y y2 5 x12 π x 5 53 cos3 t Evoluta: B sen33 t y 5 52 sin −π A π x −π se corten en un solo punto y tengan una recta tangente común y curvatura igual en ese punto. Trazar una gráfica para cada conjunto de valores de a y b. CAS 81. Investigación Considerar la función f sxd 5 x 4 2 x 2. a) Usar un sistema computacional para álgebra y encontrar la curvatura K de la curva como función de x. En los ejercicios 63 a 70 a) hallar el punto de la curva en el que la curvatura K es máxima y b) hallar el límite de K cuando x → `. 63. y 5 sx 2 1d2 1 3 64. y 5 x3 65. y 5 x 2y3 66. y 5 67. y 5 ln x 68. y 5 e 69. y 70. y senh x 71. y 5 1 2 73. y 5 cos x b) Usar el resultado del inciso a) para hallar los círculos de curvatura de la gráfica de f en x 5 0 y x 5 1. Usar un sistema algebraico por computadora y representar gráficamente la función y los dos círculos de curvatura. 1 x c) Representar gráficamente la función Ksxd y compararla con la gráfica de f sxd. Por ejemplo, ¿se presentan los extremos de f y K en los mismos números críticos? Explicar el razonamiento. x cosh x En los ejercicios 71 a 74, hallar todos los puntos de la gráfica de una función en los que la curvatura es cero. x3 879 Desarrollo de conceptos (continuación) x51 1 3 Longitud de arco y curvatura 82. Investigación La superficie de una copa se forma por revolución de la gráfica de la función y 5 14 x 8y5, 72. y 5 sx 2 1d 1 3 sin x 74. y 5 sen 0 ≤ x ≤ 5 en torno al eje y. Las medidas se dan en centímetros. 3 CAS a) Usar un sistema algebraico por computadora y representar gráficamente la superficie. b) Hallar el volumen de la copa. Desarrollo de conceptos c) Hallar la curvatura K de la curva generatriz como función de x. Usar una herramienta de graficación para representar K. 75. a) Dada la fórmula para la longitud de arco de una curva suave en el espacio. d) Si un objeto esférico se deja caer en la copa, ¿es posible que toque el fondo? Explicar la respuesta. b) Dada las fórmulas para la curvatura en el plano y en el espacio. 83. Una esfera de radio 4 se deja caer en el paraboloide dado por z 5 x 2 1 y 2. 76. Describir la gráfica de una función vectorial para la que la curvatura sea 0 en todos los valores t de su dominio. a) ¿Qué tanto se acercará la esfera al vértice del paraboloide? b) ¿Cuál es el radio de la esfera mayor que toca el vértice? 12-5.qxd 3/12/09 880 18:22 Page 880 CAPÍTULO 12 Funciones vectoriales 84. Rapidez Cuanto menor es la curvatura en una curva de una carretera, mayor es la velocidad a la que pueden ir los automóviles. Suponer que la velocidad máxima en una curva es inversamente proporcional a la raíz cuadrada de la curvatura. Un automóvil que recorre la trayectoria y 5 13 x3 (x y y medidos en millas) puede ir con seguridad a 30 millas por hora en s1, 13 d. ¿Qué tan rápido puede ir en s32, 98 d? 85. Sea C una curva dada por y 5 f sxd. Sea K la curvatura sK Þ 0d en el punto Psx0, y0d y sea z5 1 1 f9sx0d2 . f 0 sx0d Mostrar que las coordenadas sa, bd del centro de curvatura en P son sa, bd 5 sx0 2 f9sx0dz, y0 1 zd. 86. Usar el resultado del ejercicio 85 para hallar el centro de curvatura de la curva en el punto dado. a) y 5 e x, s0, 1d b) y 5 x2 , 2 11, 122 c) y 5 x2, s0, 0d 87. Se da una curva C por medio de la ecuación polar r 5 f sud. Mostrar que la curvatura K en el punto sr, ud es K5 f2sr9 d2 2 rr0 1 r2g . fsr9 d2 1 r2g3y2 fSugerencia: Representar la curva por r1u2 5 r cos u i 1 r sen u j.] 88. Usar el resultado del ejercicio 87 para hallar la curvatura de cada una de las curvas polares. a) r 5 1 1 sen sin u b) r 5 u sen u c) r 5 a sin d) r 5 eu 89. Dada la curva polar r 5 eau, a > 0, hallar la curvatura K y determinar el límite de K cuando a) u → ` y b) a → `. 90. Mostrar que la fórmula para la curvatura de una curva polar r 5 f sud dada en el ejercicio 87 se reduce a K 5 2y r9 para la curvatura en el polo. | | En los ejercicios 91 y 92, usar el resultado del ejercicio 90 para hallar la curvatura de la curva rosa en el polo. 91. r 5 4 sen sin 2u 92. r 5 6 cos 3u 93. Para la curva suave dada por las ecuaciones paramétricas x 5 f std y y 5 gstd, demostrar que la curvatura está dada por K5 | f9stdg0 std 2 g9stdf 0 std| . Hf f9stdg 2 1 f g9 stdg 2J3y2 97. Fuerza de rozamiento o de fricción Un vehículo de 5 500 libras va a una velocidad de 30 millas por hora por una glorieta de 100 pies de radio. ¿Cuál es la fuerza de fricción o de rozamiento que debe ejercer la superficie de la carretera en los neumáticos para impedir que el vehículo salga de curso? 98. Fuerza de rozamiento o de fricción Un vehículo de 6 400 libras viaja a 35 millas por hora en una glorieta de 250 pies de radio. ¿Cuál es la fuerza de fricción o de rozamiento que debe ejercer la superficie de la carretera en los neumáticos para impedir que el vehículo salga de curso? 99. Verificar que la curvatura en cualquier punto sx, yd de la gráfica de y 5 cosh x es 1yy2. 100. Usar la definición de curvatura en el espacio K 5 iT9(s)i 5 ir0(s)i, para verificar cada una de las fórmulas siguientes. iT9std i a) K 5 ir9std i ir9std 3 r0 std i b) K 5 ir9std i3 c) K 5 astd ? Nstd ivstd i2 ¿Verdadero o falso? En los ejercicios 101 a 104, determinar si la declaración es verdadera o falsa. Si es falsa, explicar por qué o dar un ejemplo que demuestre que es falsa. 101. La longitud de arco de una curva en el espacio depende de la parametrización. 102. La curvatura de un círculo es igual a su radio. 103. La curvatura de una recta es 0. 104. La componente normal de la aceleración es función tanto de la velocidad como de la curvatura. Leyes de Kepler En los ejercicios 105 a 112, se pide verificar las leyes de Kepler del movimiento planetario. En estos ejercicios, suponer que todo planeta se mueve en una órbita dada por la función vectorial r. Sean r 5 r , G la constante gravitatoria universal, M la masa del Sol y m la masa del planeta. || || dr . dt 106. Usando la segunda ley del movimiento de Newton, F 5 ma, y la segunda ley de la gravitación de Newton, F 5 21GmMYr32r, mostrar que a y r son paralelos, y que rstd 3 r9std 5 L es un vector constante. Por tanto, rstd se mueve en un plano fijo, ortogonal a L. 105. Demostrar que r ? r9 5 r 34 d r 1 5 3 Hfr 3 r9 g 3 rJ. dt r r r9 r 108. Mostrar que 3 L 2 5 e es un vector constante. GM r 109. Demostrar la primera ley de Kepler: todo planeta describe una órbita elíptica con el Sol como uno de sus focos. 94. Usar el resultado del ejercicio 93 para encontrar la curvatura K de la curva representada por ecuaciones paramétricas xstd 5 t3 y ystd 5 12t 2. Usar una herramienta de graficación para representar K y determinar toda asíntota horizontal. Interpretar las asíntotas en el contexto del problema. 107. Demostrar que 95. Usar el resultado del ejercicio 93 para encontrar la curvatura K de la cicloide representada por las ecuaciones paramétricas 110. Suponer que la órbita elíptica r 5 edys1 1 e cos ud está en el plano xy, con L a lo largo del eje z. Demostrar que i L i 5 r 2 duydt. xsud 5 asu 2 sen sin ud y ysud 5 as1 2 cos ud. ¿Cuáles son los valores mínimo y máximo de K? 96. Usar el teorema 12.10 para encontrar aT y aN de cada una de las curvas dadas por las funciones vectoriales. a) rstd 5 3t 2 i 1 s3t 2 t 3dj b) rstd 5 t i 1 t 2 j 1 12 t 2 k 111. Demostrar la segunda ley de Kepler: todo rayo del Sol a un planeta barre áreas iguales de la elipse en tiempos iguales. 112. Demostrar la tercera ley de Kepler: el cuadrado del periodo de la órbita de un planeta es proporcional al cubo de la distancia media entre el planeta y el Sol. 12-6.qxd 3/12/09 18:24 Page 881 881 Ejercicios de repaso Ejercicios de repaso 12 En los ejercicios 1 a 4, a) hallar el dominio de r y b) determinar los valores de t (si los hay) en los que la función es continua. 1 1. r(t) 5 tan t i 1 j 1 t k 2. rstd 5 !t i 1 j1k t24 3. rstd 5 ln t i 1 t j 1 t k 4. rstd 5 s2t 1 1d i 1 t 2 j 1 t k En los ejercicios 5 y 6, evaluar (si es posible) la función vectorial en cada uno de los valores dados de t. 5. r t 2t t2 j 1i t 1p2 2 c) rss 2 pd d) rsp 1 Dtd 2 rspd CAS cos t, sen t 8. r t 2, t2 t 1 En los ejercicios 9 a 14, usar un sistema algebraico por computadora a fin de representar gráficamente la curva en el espacio representada por la función vectorial. 9. rstd 5 i 1 t j 1 t 2 k t2 i 10. r t 11. rstd 5 k1, sen sin t, 1l t3 k 3t j 12. rstd 5 k2 cos t, t, 2 sen sin tl 1 13. rstd 5 k t, ln t, 2t 2l 14. rstd 5 En los ejercicios 15 y 16, hallar las funciones vectoriales que describen la frontera de la región de la figura. y 15. b) r0 xtc d) Dt [uxtc 2 2rxtc] e) Dt [ rxtc ] , t > 0 || || 5 4 4 3 3 2 2 1 3 4 5 1 k t En los ejercicios 27 a 30, hallar la integral indefinida. 27. 30. E E E scos t i 1 t cos t jd dt 28. E sln t i 1 t ln t j 1 kd dt icos t i 1 sen sin t j 1 t ki dt st j 1 t 2 kd 3 si 1 t j 1 t kd dt E E 33. s3t i 1 2t 2 j 2 t 3 kd dt 32. 1 2 3 4 5 17. Una partícula se mueve en una trayectoria recta que pasa por los puntos s22, 23, 8d y s5, 1, 22d. Hallar una función vectorial para esta trayectoria. (Hay muchas respuestas correctas.) 18. El borde exterior de una escalera de caracol tiene forma de una hélice de 2 metros de radio. La altura de la escalera es 2 metros y gira tres cuartos de una revolución completa de abajo a arriba. Hallar una función vectorial para la hélice. (Hay muchas respuestas correctas.) d !t j 1 t sen sin tk dt 0 1 se ty2 i 2 3t 2 j 2 kd dt 34. 21 0 x Es E 1 22 2 1 2 1 26. Redacción La componente x de la derivada de la función vectorial u es 0 para t en el dominio de la función. ¿Qué implica esta información acerca de la gráfica de u? 31. x 1 f) Dt [rxtc 3 uxtc] 2 3 3t k 25. Redacción Las componentes x y y de la derivada de la función vectorial u son positivas en t 5 t0, y la componente z es negativa. Describir el comportamiento de u en t 5 t0. 2 5 t2 j En los ejercicios 31 a 34, evaluar la integral definida. y 16. c) Dt [rxtc ? uxtc] a) r9xtc 29. k 12t, !t, 14t 3l 2 En los ejercicios 23 y 24, hallar lo siguiente. sin t i 1 cos t j 1 t k, ustd 5 sen sin t i 1 cos t j 1 24. rstd 5 sen En los ejercicios 7 y 8, trazar la curva plana representada por la función vectorial y dar la orientación de la curva. 7. r t 1 23. rstd 5 3t i 1 st 2 1d j, ustd 5 t i 1 2k a) rs0d b) rs22d c) rsc 2 1d d) rs1 1 Dtd 2 rs1d 6. rstd 5 3 cos t i 1 s1 2 sen sin td j 2 t k a) rs0d b) r En los ejercicios 21 y 22, evaluar el límite. sen sin 2t lím 21. lím t i 22. lim i 1 e2t j 1 et k 4 tj k t→0 t→4 t st 3 i 1 arcsen arcsin tj 2 t 2 kd dt En los ejercicios 35 y 36, hallar rxtc para las condiciones dadas. 35. r9std 5 2t i 1 et j 1 e2t k, rs0d 5 i 1 3j 2 5k 36. r9std 5 sec t i 1 tan t j 1 t 2 k, rs0d 5 3k En los ejercicios 37 a 40, el vector posición r describe la trayectoria de un objeto que se mueve en el espacio. Hallar la velocidad, la rapidez y la aceleración del objeto. 37. r t 4ti t3j tk sen33 t, 3tl 39. rstd 5 kcos3 t, sin 38. r t ti 5tj 2t2k 40. rstd 5 kt, 2tan t, et l En los ejercicios 19 y 20, dibujar la curva en el espacio representada por la intersección de las superficies. Usar el parámetro x 5 t para hallar una función vectorial para la curva en el espacio. Aproximación lineal En los ejercicios 41 y 42, hallar un conjunto de ecuaciones paramétricas para la recta tangente a la gráfica de la función vectorial en t 5 t0. Usar las ecuaciones de la recta para aproximar rxt0 1 0.1c. 19. z 5 x 2 1 y 2, x1y50 41. rstd 5 lnst 2 3d i 1 t 2 j 1 12t k, 20. x 2 1 z 2 5 4, x2y50 t0 5 4 42. rstd 5 3 cosh t i 1 senh sinh t j 2 2t k, t0 5 0 12-6.qxd 3/12/09 882 18:24 Page 882 CAPÍTULO 12 Funciones vectoriales Movimiento de un proyectil En los ejercicios 43 a 46, usar el modelo para el movimiento de un proyectil, suponiendo que no hay resistencia del aire. [axtc 5 232 pies por segundo al cuadrado o astd 5 29.8 metros por segundo al cuadrado.] En los ejercicios 59 a 62, dibujar la curva plana y hallar su longitud en el intervalo dado. 43. Un proyectil se dispara desde el nivel del suelo a una velocidad inicial de 84 pies por segundo con un ángulo de 30° con la horizontal. Hallar el alcance del proyectil. 60. rstd 5 t 2 i 1 2tk 44. El centro de la caja de un camión está a 6 pies hacia abajo y a 4 pies horizontalmente del extremo de una cinta transportadora horizontal que descarga grava (ver la figura). Determinar la velocidad dsydt a que la cinta transportadora debe moverse para que la grava caiga en el centro de la caja del camión. v0 Función Intervalo 59. rstd 5 2ti 2 3tj f0, 5g f0, 3g f0, 2pg f0, 2pg sin3 t j 61. rstd 5 10 cos3 t i 1 10 sen sin t j 62. rstd 5 10 cos t i 1 10 sen En los ejercicios 63 a 66, dibujar la curva en el espacio y hallar su longitud en el intervalo dado. Función Intervalo f0, 3g f0, 2g f0, py2g f0, py2g 63. rstd 5 23t i 1 2tj 1 4tk 4 pies 64. rstd 5 ti 1 t 2 j 1 2tk sin t, tl 65. rstd 5 k8 cos t, 8 sen 6 pies sin t 2 t cos td, 2scos t 1 t sen sin td, tl 66. rstd 5 k2ssen En los ejercicios 67 a 70, hallar la curvatura K de la curva. 67. rstd 5 3ti 1 2tj 45. Un proyectil se dispara desde el nivel del suelo con un ángulo de 20° con la horizontal. El proyectil tiene un alcance de 95 metros. Hallar la velocidad inicial mínima. 46. Usar una herramienta de graficación para representar las trayectorias de un proyectil si v0 5 20 metros por segundo, h 5 0 y a) u 5 308, b) u 5 45° y c) u 5 608. Usar las gráficas para aproximar en cada caso la altura máxima y el alcance máximo del proyectil. En los ejercicios 47 a 54, hallar la velocidad, la rapidez y la aceleración en el instante t. A continuación hallar a ? T y a ? N en el instante t. 47. rstd 5 s2 2 td i 1 3tj 48. rstd 5 s1 1 4td i 1 s2 2 3td j 49. rstd 5 t i 1 !t j 50. rstd 5 2st 1 1d i 1 2 j t11 51. rstd 5 et i 1 e2t j sin t j 52. rstd 5 t cos t i 1 t sen 69. rstd 5 2ti 1 1 2 2t j 68. rstd 5 2!t i 1 3tj 1 t2k sin tk 70. rstd 5 2ti 1 5 cos tj 1 5 sen En los ejercicios 71 y 72, encontrar la curvatura K de la curva en el punto P. 71. rstd 5 1 2 1 t i 1 tj 1 t3k, 2 3 P 112, 1, 132 sin tj 1 tk, Ps24, 0, pd 72. rstd 5 4 cos ti 1 3 sen En los ejercicios 73 a 76, hallar la curvatura y el radio de curvatura de la curva plana en el valor dado de x. 73. y 5 12 x 2 1 2, x54 74. y 5 e2xy2, x50 p 4 77. Redacción Un ingeniero civil diseña una autopista como se muestra en la figura. BC es un arco del círculo. AB y CD son rectas tangentes al arco circular. Criticar el diseño. 75. y 5 ln x, 1 2 t k 2 1 54. rstd 5 st 2 1d i 1 t j 1 k t 53. rstd 5 t i 1 t 2 j 1 x51 B 76. y 5 tan x, x 5 y C 2 (1, 1) 1 x En los ejercicios 55 y 56, hallar un conjunto de ecuaciones paramétricas para la recta tangente a la curva en el espacio en el punto dado. p sin t j 1 t k, t 5 55. rstd 5 2 cos t i 1 2 sen 3 2 56. rstd 5 t i 1 t 2 j 1 3t3 k, t 5 2 57. Órbita de un satélite Hallar la velocidad necesaria para que un satélite mantenga una órbita circular 550 millas sobre la superficie de la Tierra. 58. Fuerza centrípeta Un automóvil circula por una glorieta al doble de la velocidad permitida. ¿En un factor de cuánto aumenta la fuerza centrípeta sobre la que se tendría a la velocidad permitida? A D −2 1 2 3 (− 1, −1) Figura para 77 Figura para 78 78. Un segmento de recta se extiende horizontalmente a la izquierda desde el punto s21, 21d. Otro segmento de recta se extiende horizontalmente a la derecha del punto s1, 1d, como se muestra en la figura. Hallar una curva de la forma y 5 ax 5 1 bx 3 1 cx que una los puntos s21, 21d y s1, 1d de manera que la pendiente y curvatura de la curva sean cero en los puntos terminales. 12-6.qxd 3/12/09 18:24 Page 883 Solución de problemas Solución de problemas SP 1. La espiral de Cornu está dada por E t xstd 5 883 cos 0 E t pu2 1 2 2 du y ystd 5 0 pu2 1 2 2 du. sin sen 4. Repetir el ejercicio 3 si el bombardero está orientado en dirección opuesta a la del lanzamiento, como se muestra en la figura. y 4 000 La espiral mostrada en la figura fue trazada sobre el intervalo 2 p ≤ t ≤ p. 3 200 Bomba 1 600 Proyectil θ Cañón x 5 000 5. Considerar un arco de la cicloide rsud 5 su 2 sen sin udi 1 s1 2 cos udj, 0 # u # 2p Generada con Mathematica a) Hallar la longitud de arco de esta curva desde t 5 0 hasta t 5 a. b) Hallar la curvatura de la gráfica cuando t 5 a. c) La espiral de Cornu la descubrió James Bernoulli. Bernoulli encontró que la espiral tiene una relación interesante entre curvatura y longitud del arco. ¿Cuál es esta relación? que se muestra en la figura. Sea s(u) la longitud de arco desde el punto más alto del arco hasta el punto (x(u), y(u)), y sea r(u) 5 1 el radio de curvatura en el punto (x(u), y(u)). K Mostrar que s y r están relacionados por la ecuación s2 1 r2 5 16. (Esta ecuación se llama ecuación natural de la curva.) y 2. Sea T la recta tangente en el punto Psx, yd a la gráfica de la curva x 2y3 1 y2y3 5 a 2y3, a > 0, como se observa en la figura. Mostrar que el radio de curvatura en P es el triple de la distancia del origen a la recta tangente T. (x(θ ), y(θ )) y a x P(x, y) π x a −a T −a 3. Un bombardero vuela horizontalmente a una altitud de 3 200 pies con una velocidad de 400 pies por segundo cuando suelta una bomba. Un proyectil se lanza 5 segundos después desde un cañón orientado hacia el bombardero y abajo a 5 000 pies del punto original del bombardero, como se muestra en la figura. El proyectil va a interceptar la bomba a una altitud de 1 600 pies. Determinar la velocidad inicial y el ángulo de inclinación del proyectil. (Despreciar la resistencia del aire.) y 2π 6. Considere la cardioide r 5 1 2 cos u, 0 ≤ u ≤ 2p, que se muestra en la figura. Sea ssud la longitud de arco desde el punto 1 s2, pd de la cardioide hasta el punto sr, ud, y sea rsud 5 el K radio de curvatura en el punto sr, ud. Mostrar que s y r están relacionados por la ecuación s 2 1 9r2 5 16. (Esta ecuación se llama ecuación natural de la curva.) π 2 (r, θ ) (2, π ) 0 1 4 000 3 200 Bomba 1 600 7. Si rstd es una función no nula y derivable en t, demostrar que Proyectil θ x Cañón 5 000 d 1 sirstdid 5 r std ? r9std. dt irstdi 12-6.qxd 3/12/09 884 18:24 Page 884 CAPÍTULO 12 Funciones vectoriales 8. Un satélite de comunicaciones se mueve en una órbita circular alrededor de la Tierra a una distancia de 42 000 kilómetros del centro de la Tierra. La velocidad angular du p radianes por hora 5v5 dt 12 a) Utilizar coordenadas polares para mostrar que el vector aceleración está dado por d 2r d 2r du 5 2r 2 dt dt 2 dt 1 2 4u 1 3r ddtu 1 2 drdt ddtu4u 3 a) Usar una herramienta de graficación para representar la función. b) Hallar la longitud de arco en el inciso a). es constante. a5 13. Considerar la función vectorial rstd 5 kt cos p t, t sen sin p tl, 0 # t # 2. 2 2 r 2 u donde ur 5 cos u i 1 sen sin u j es el vector unitario en la dirección radial y uu 5 2sin sen u i 1 cos uj. b) Hallar las componentes radial y angular de la aceleración para el satélite. En los ejercicios 9 a 11, usar el vector binormal definido por la ecuación B 5 T 3 N. 9. Hallar los vectores unitario tangente, unitario normal y binorp sin tj 1 3tk en t 5 . mal a la hélice rstd 5 4 cos ti 1 4 sen 2 Dibujar la hélice junto con estos tres vectores unitarios mutuamente ortogonales. 10. Hallar los vectores unitario tangente, unitario normal y binorp mal a la curva rstd 5 cos ti 1 sen sin tj 2 k en t 5 . Dibujar la 4 hélice junto con estos tres vectores unitarios mutuamente ortogonales. c) Hallar la curvatura K como función de t. Hallar las curvaturas cuando t es 0, 1 y 2. d) Usar una herramienta de graficación para representar la función K. e) Hallar (si es posible) el lím lim K. t→ ` f) Con el resultado del inciso e), hacer conjeturas acerca de la gráfica de r cuando t → `. 14. Se quiere lanzar un objeto a un amigo que está en una rueda de la fortuna (ver la figura). Las ecuaciones paramétricas siguientes dan la trayectoria del amigo r1std y la trayectoria del objeto r2std. La distancia está dada en metros y el tiempo en segundos. 1 r1std 5 15 sen sin pt pt i 1 16 2 15 cos j 10 10 2 1 2 r2std 5 f22 2 8.03st 2 t0dg i 1 f1 1 11.47st 2 t0d 2 4.9st 2 t0d2g j 11. a) Demostrar que existe un escalar t, llamado torsión, tal que dByds 5 2 t N. b) Demostrar que dN 5 2K T 1 t B. ds (Las tres ecuaciones dTyds 5 K N, dNyds 5 2K T 1 t B, y dByds 5 2 t N son llamadas las fórmulas de Frenet-Serret.) 12. Una autopista tiene una rampa de salida que empieza en el ori1 5y2 gen de un sistema coordenado y sigue la curva y 5 32 x hasta el punto (4, 1) (ver la figura). Después sigue una trayectoria circular cuya curvatura es la dada por la curva en s4, 1d. ¿Cuál es el radio del arco circular? Explicar por qué la curva y el arco circular deben tener en (4, 1) la misma curvatura. Arco circular y a) Localizar la posición del amigo en la rueda en el instante t 5 0. b) Determinar el número de revoluciones por minuto de la rueda. 4 y= 1 5/2 x 32 c) ¿Cuál es la rapidez y el ángulo de inclinación (en grados) al que el objeto es lanzado en el instante t 5 t0? 2 (4, 1) x 2 4 6 d) Usar una herramienta de graficación para representar las funciones vectoriales usando un valor de t0 que permite al amigo alcanzar el objeto. (Hacer esto por ensayo y error.) Explicar la importancia de t0. e) Hallar el instante aproximado en el que el amigo deberá poder atrapar el objeto. Aproximar las velocidades del amigo y del objeto en ese instante. 1053714_cop13.qxd Larson-13-01.qxd 10/27/08 12:04 PM 3/12/09 18:39 PagePage 885 885 Functions of de Several Funciones varias Functions of Several Variables Variables variables 13 13 13 In this chapter, you will study functions of In Inthis thischapter, chapter,you youwill willstudy studyfunctions functionsof of En este capítulo se estudiarán funciones more than one independent variable. Many more more than than one one independent independent variable. variable. Many Many In this chapter, you will study functions of de másconcepts de una variable independiente. of the concepts presented are extensions of of ofthe the concepts presented presented are are extensions extensions of of more than one independent variable. Many Muchos de los conceptos presentados familiar ideas from earlier chapters. familiar familiar ideas ideas from from earlier earlier chapters. chapters. of the concepts presented are extensions of son extensiones de ideas familiares de familiar ideas from earlier chapters. In this chapter, you should learn the In In this this chapter, chapter, you you should should learn learn the the capítulos recientes. following. following. following. In this should learn the En estechapter, capítulo,you se aprenderá: following. ■ How to sketch graph, level curves, ■n ■ How How to totrazar sketch sketchuna aaagraph, graph, level level curves, curves, Cómo gráfica, curvas de and level surfaces. ( 13.1 ) and level level surfaces. surfaces. ( ( 13.1 13.1 ) ) ■ and nivel y superficies de nivel. ( 13.1 ) How to sketch a graph, level curves, ■ How to find a limit and determine ■ ■ and level surfaces. 13.1 ) y determiHow totoencontrar find find aalimit limit and determine determine n How Cómo un(and límite continuity. 13.2 continuity. (((13.2 13.2 ))) and ■ continuity. nar latocontinuidad. (13.2 ) How find a limit determine ■ How to find and use a partial derivative. ■ ■ How continuity. ( 13.2 ) n How to to find find and and use use a a partial partial derivative. derivative. Cómo encontrar y usar una derivada ( 13.3 ) ( ( 13.3 13.3 ) ) parcial. (13.3 ) use a partial derivative. ■ How to find and ■ n Cómo y usar unadifferential diferenHow to find and use total differential ■ ■ How (How 13.3to )toencontrar find findand anduse use aaatotal total differential cial total y determinar diferenciabili13.4 and determine differentiability. and and determine determine differentiability. differentiability. (((13.4 13.4))) ■ How to find and use a total differential dad. ( 13.4 ) ■ How to use the Chain Rules and find ■■ How and 13.4 Howdetermine to touse usethe thedifferentiability. Chain ChainRules Rulesand and(find find)aaa n partial Cómoderivative usar la regla de la cadena derivative implicitly. ( 13.5 ) partial derivative implicitly. implicitly. ( ( 13.5 13.5 ) )y a ■ partial How to use the Chain Rules and find encontrar una derivada parcial implí■ How to find and use directional ■ ■ How partial implicitly. (13.5) Howto toderivative find findand anduse use aaadirectional directional ■ ■ ■ cita. (13.5 ) a gradient. (13.6) derivative and derivative and and aagradient. gradient. ((13.6 13.6)) ■ derivative How to find and use a directional n Cómo encontrar y usar una derivada ■ ■ How to find an equation of aatangent tangent ■ ■ How derivative and aequation gradient. ) How to tofind find an equation of of(a13.6 tangent direccional yanun gradiente. (13.6) plane and an equation of a normal line plane plane and and an an equation equation of of a a normal normal line line ■ toencontrar find an equation of a tangent n How Cómo unatoecuación de un to a surface, and how find the angle to to a a surface, surface, and and how how to to find find the the angle angle plane and an equation of a normal line plano tangente y una ecuación de una of inclination of plane. ((13.7 13.7 of ofinclination of ofaaahow plane. plane. 13.7 ))) angle to ainclination surface, to (find the recta normaland a una superficie, y cómo ■ How to find absolute and ■ ■ How of inclination of a plane. (relative 13.7) How to tofind findelabsolute absolute and andinclinación relative relative encontrar ángulo de de extrema. ( 13.8 ) extrema. extrema. ( ( 13.8 13.8 ) ) ■ How to find(13.7 absolute un plano. ) and relative ■ How to solve an optimization problem, ■ ■ How extrema. (13.8 ) optimization How to tosolve solve an an optimization problem, problem, n Cómo encontrar los extremos absoluincluding constrained optimization using including constrained constrained optimization optimization using using ■ including tos y relativos. ( 13.8 ) How to solve an optimization problem, a Lagrange multiplier, and how to use the a a Lagrange Lagrange multiplier, multiplier, and and how how to to use use the the constrained optimization using n including Cómo resolver un problema de optimethod of least squares. ( 13.9, 13.10 ) method method of of least least squares. squares. ( ( 13.9, 13.9, 13.10 13.10 ) ) amización, Lagrangeincluida multiplier, and how to use optimización res-the method least squares. (13.9, 13.10 tringidaofusando un multiplicador de) Lagrange, y cómo usar el método de mínimos cuadrados. (13.9, 13.10) NOAA NOAA NOAA Meteorologists use maps that show curves of equal atmospheric pressure, called NOAA Meteorologists Meteorologistsuse usemaps mapsthat thatshow showcurves curvesof ofequal equalatmospheric atmosphericpressure, pressure,called called isobars , to predict weather patterns. How can you use pressure gradients to isobars isobars , , to to predict predict weather weather patterns. patterns. How How can can you you use use pressure pressure gradients gradients to to Los meteorólogos usan mapas que muestran curvas de presión atmosférica igual, ■ ■ ■ Meteorologists use maps that show curves of equal atmospheric pressure, called determine the area of the country that has the greatest wind speed? (See Section determine determine the the area areaof of the thepredecir country country that that has hascan the thegreatest greatest wind wind speed? speed? (See Section Section llamadas para losHow patrones del use clima. ¿Cómo se(See pueden isobars, toisobaras, predict weather patterns. you pressure gradients to usar los ■ 13.6, Exercise 68.) 13.6, 13.6, Exercise Exercise 68.) 68.) gradientes de presión paracountry determinar el área del paíswind que tiene las(See mayores determine the area of the that has the greatest speed? Section velocidades de 68.) viento? (Ver la sección 13.6, ejercicio 68.) 13.6, Exercise zzz zzz zzz yyy z z z y xxx yyy yyy yyy y y y xxx x xxx xxx x x x Many real-life quantities are functions of two or more variables. In Section 13.1, you will learn how to graph function Muchas cantidades de laare vida real son devariables. dos o más En la sección 13.1 se to aprenderá cómo Many Manyreal-life real-life quantities quantities are functions functions of offunciones two twoor ormore more variables. In Invariables. Section Section13.1, 13.1, you you will will learn learn how how tograph graphaaafunction function of two variables, like the one shown above. The first three graphs show cut-away views of the surface at various graficar una función de dos variables, tal como la que se muestra arriba. Las primeras tres gráficas muestran visof of two two variables, variables, like like the the one one shown shown above. above. The The first first three three graphs graphs show show cut-away cut-away views views of of the the surface surface at at various various Many real-life quantities are functions of two or more variables. In Section 13.1, you will learn how to graph a function traces. Another way to visualize this surface is to project the traces onto the xy -plane, as shown in the fourth graph. tas cortadas de la superficie en varios trazos. Otra forma de visualizar estas superficies es proyectar los trazos traces. traces. Another Another way way to to visualize visualize this this surface surface is is to to project project the the traces traces onto onto the the xy xy -plane, -plane, as as shown shown in in the the fourth fourth graph. graph. of two variables, like the one shown above. The first three graphs show cut-away views of the surface at various hacia plano xy, taltocomo se muestra en laiscuarta gráfica. traces.elAnother way visualize this surface to project the traces onto the xy-plane, as shown in the fourth graph. 885 885 885885 885 885885 Larson-13-01.qxd 886 3/12/09 18:39 CAPÍTULO 13 Page 886 Funciones de varias variables 13.1 Introducción a las funciones de varias variables n n n n n Entender la notación para una función de varias variables. Dibujar la gráfica de una función de dos variables. Dibujar las curvas de nivel de una función de dos variables. Dibujar las superficies de nivel de una función de tres variables. Utilizar gráficos por computadora para representar una función de dos variables. Funciones de varias variables EXPLORACIÓN Comparación de dimensiones Sin usar una herramienta de graficación, describir la gráfica de cada función de dos variables. Hasta ahora en este texto, sólo se han visto funciones de una sola variable (independiente). Sin embargo, muchos problemas comunes son funciones de dos o más variables. Por ejemplo, el trabajo realizado por una fuerza sW 5 FDd y el volumen de un cilindro circular recto sV 5 p r 2hd son funciones de dos variables. El volumen de un sólido rectangular sV 5 lwhd es una función de tres variables. La notación para una función de dos o más variables es similar a la utilizada para una función de una sola variable. Aquí se presentan dos ejemplos. a) z 5 x 2 1 y 2 z 5 f sx, yd 5 x2 1 xy b) z 5 x 1 y c) z 5 x 2 1 y d) z 5 !x 2 1 y 2 e) z 5 !1 2 x 2 1 y 2 Función de 2 variables. 2 variables y w 5 f sx, y, zd 5 x 1 2y 2 3z Función de 3 variables. 3 variables DEFINICIÓN DE UNA FUNCIÓN DE DOS VARIABLES Archive Photos Sea D un conjunto de pares ordenados de números reales. Si a cada par ordenado (x, y) de D le corresponde un único número real f(x, y), entonces se dice que f es una función de x y y. El conjunto D es el dominio de f, y el correspondiente conjunto de valores f(x, y) es el rango de f. MARY FAIRFAX SOMERVILLE (1780-1872) Somerville se interesó por el problema de crear modelos geométricos de funciones de varias variables. Su libro más conocido, The Mechanics of the Heavens, se publicó en 1831. En la función dada por z 5 f sx, yd, x y y son las variables independientes y z es la variable dependiente. Pueden darse definiciones similares para las funciones de tres, cuatro o n variables donde los dominios consisten en tríadas (x1, x2, x3), tétradas (x1, x2, x3, x4) y n-adas (x1, x2, . . ., xn). En todos los casos, rango es un conjunto de números reales. En este capítulo, sólo se estudian funciones de dos o tres variables. Como ocurre con las funciones de una variable, la manera más común para describir una función de varias variables es por medio de una ecuación, y a menos que se diga explícitamente lo contrario, se puede suponer que el dominio es el conjunto de todos los puntos para los que la ecuación está definida. Por ejemplo, el dominio de la función dada por f sx, yd 5 x 2 1 y 2 se supone que es todo el plano xy. Similarmente, el dominio de f sx, yd 5 ln xy es el conjunto de todos los puntos sx, yd en el plano para los que xy > 0. Esto consiste en todos los puntos del primer y tercer cuadrantes. Larson-13-01.qxd 3/12/09 18:39 Page 887 SECCIÓN 13.1 EJEMPLO 1 Introducción a las funciones de varias variables 887 Dominios de funciones de varias variables y Hallar el dominio de cada función. 4 a) f sx, yd 5 2 1 −2 −1 −1 1 2 −2 −4 Dominio de x2 + y2 − 9 f(x, y) = x Figura 13.1 x b) g sx, y, zd 5 x !9 2 x 2 2 y 2 2 z 2 Solución x −4 !x 2 1 y 2 2 9 4 a) La función f está definida para todos los puntos sx, yd tales que x Þ 0 y x 2 1 y 2 ≥ 9. Por tanto, el dominio es el conjunto de todos los puntos que están en el círculo x 2 1 y 2 5 9, o en su exterior, con excepción de los puntos en el eje y, como se muestra en la figura 13.1. b) La función g está definida para todos los puntos sx, y, zd tales que x 2 1 y 2 1 z 2 < 9. Por consiguiente, el dominio es el conjunto de todos los puntos sx, y, zd que se encuentran en el interior de la esfera de radio 3 centrada en el origen. Las funciones de varias variables pueden combinarse de la misma manera que las funciones de una sola variable. Por ejemplo, se puede formar la suma, la diferencia, el producto y el cociente de funciones de dos variables como sigue. s f ± gdsx, yd 5 f sx, yd ± gsx, yd s f gd sx, yd 5 f sx, ydgsx, yd f f sx, yd sx, yd 5 g sx, yd Þ 0 g g sx, yd Suma o diferencia. Producto. Cociente. No se puede formar la composición de dos funciones de varias variables. Sin embargo, si h es una función de varias variables y g es una función de una sola variable, puede formarse la función compuesta s g 8 hdsx, yd como sigue. s g 8 hdsx, yd 5 g sh sx, ydd Composición. El dominio de esta función compuesta consta de todo sx, yd en el dominio de h tal que h sx, yd está en el dominio de g. Por ejemplo, la función dada por f sx, yd 5 !16 2 4x 2 2 y 2 puede verse como la composición de la función de dos variables dadas por h sx, yd 5 16 2 4x 2 2 y 2 y la función de una sola variable dada por gsud 5 !u. El dominio de esta función es el conjunto de todos los puntos que se encuentran en la elipse dada por 4x2 1 y2 5 16 o en su interior. Una función que puede expresarse como suma de funciones de la forma cx m y n (donde c es un número real y m y n son enteros no negativos) se llama una función polinomial de dos variables. Por ejemplo, las funciones dadas por f sx, yd 5 x 2 1 y 2 2 2xy 1 x 1 2 y g sx, yd 5 3xy 2 1 x 2 2 son funciones polinomiales de dos variables. Una función racional es el cociente de dos funciones polinomiales. Terminología similar se utiliza para las funciones de más de dos variables. Larson-13-01.qxd 888 3/12/09 18:39 CAPÍTULO 13 Page 888 Funciones de varias variables Gráfica de una función de dos variables Como en el caso de las funciones de una sola variable, se puede saber mucho acerca del comportamiento de una función de dos variables dibujando su gráfica. La gráfica de una función f de dos variables es el conjunto de todos los puntos sx, y, zd para los que z 5 f sx, yd y sx, yd está en el dominio de f. Esta gráfica puede interpretarse geométricamente como una superficie en el espacio, como se explicó en las secciones 11.5 y 11.6. En la figura 13.2 hay que observar que la gráfica de z 5 f sx, yd es una superficie cuya proyección sobre el plano xy es D, el dominio de f. A cada punto (x, y) en D corresponde un punto (x, y, z) de la superficie y, viceversa, a cada punto (x, y, z) de la superficie le corresponde un punto (x, y) en D. Figura 13.2 EJEMPLO 2 Descripción de la gráfica de una función de dos variables ¿Cuál es el rango de f sx, yd 5 !16 2 4x 2 2 y 2 ? Describir la gráfica de f. Solución El dominio D dado por la ecuación de f es el conjunto de todos los puntos (x, y) tales que 16 2 4x 2 2 y 2 ≥ 0. Por tanto, D es el conjunto de todos los puntos que pertenecen o son interiores a la elipse dada por x2 y2 1 5 1. 4 16 Elipse en el plano xy. El rango de f está formado por todos los valores z 5 f sx, yd tales que 0 ≤ z ≤ !16 o sea 0 ≤ z ≤ 4. Rango de f. Un punto (x, y, z) está en la gráfica de f si y sólo si z 5 !16 2 4x 2 2 y 2 La gráfica de f sx, yd 5 ! 16 2 4x 2 2 y 2 es la mitad superior de un elipsoide Figura 13.3 z 2 5 16 2 4x 2 2 y 2 4x 2 1 y 2 1 z 2 5 16 x2 y2 z2 1 1 5 1, 4 16 16 z= 16 − 4x 2 − y 2 0 ≤ z ≤ 4. De acuerdo con la sección 11.6, se sabe que la gráfica de f es la mitad superior de un elipsoide, como se muestra en la figura 13.3. z Para dibujar a mano una superficie en el espacio, es útil usar trazas en planos paralelos a los planos coordenados, como se muestra en la figura 13.3. Por ejemplo, para hallar la traza de la superficie en el plano z 5 2, se sustituye z 5 2 en la ecuación z 5 !16 2 4x 2 2 y 2 y se obtiene 2 5 !16 2 4x 2 2 y 2 x Figura 13.4 y x2 y2 1 5 1. 3 12 Por tanto, la traza es una elipse centrada en el punto (0, 0, 2) con ejes mayor y menor de longitudes 4!3 y 2!3. Las trazas también se usan en la mayor parte de las herramientas de graficación tridimensionales. Por ejemplo, la figura 13.4 muestra una versión generada por computadora de la superficie dada en el ejemplo 2. En esta gráfica la herramienta de graficación tomó 25 trazas paralelas al plano xy y 12 trazas en planos verticales. Si se dispone de una herramienta de graficación tridimensional, utilícese para representar varias superficies. Larson-13-01.qxd 3/12/09 18:39 Page 889 SECCIÓN 13.1 889 Introducción a las funciones de varias variables Curvas de nivel 20 30 1008 40 30 30 30 20 100 4 100 8 1 10 01 16 2 20 1004 40 101 2 100 8 100 4 100 0 1008 100 4 101 2 Una segunda manera de visualizar una función de dos variables es usar un campo escalar en el que el escalar z 5 f sx, yd se asigna al punto sx, yd. Un campo escalar puede caracterizarse por sus curvas de nivel (o líneas de contorno) a lo largo de las cuales el valor de f sx, yd es constante. Por ejemplo, el mapa climático en la figura 13.5 muestra las curvas de nivel de igual presión, llamadas isobaras. Las curvas de nivel que representan puntos de igual temperatura en mapas climáticos, se llaman isotermas, como se muestra en la figura 13.6. Otro uso común de curvas de nivel es la representación de campos de potencial eléctrico. En este tipo de mapa, las curvas de nivel se llaman líneas equipotenciales. 50 1008 4 0 10 08 10 80 00 10 80 00 10 70 60 1008 90 Las curvas de nivel muestran las líneas de igual presión (isobaras) medidas en milibares Las curvas de nivel muestran líneas de igual temperatura (isotermas) medidas en grados Fahrenheit Figura 13.5 Figura 13.6 Alfred B. Thomas/Earth Scenes Los mapas de contorno suelen usarse para representar regiones de la superficie de la Tierra, donde las curvas de nivel representan la altura sobre el nivel del mar. Este tipo de mapas se llama mapa topográfico. Por ejemplo, la montaña mostrada en la figura 13.7 se representa por el mapa topográfico de la figura 13.8. Un mapa de contorno representa la variación de z respecto a x y y mediante espacio entre las curvas de nivel. Una separación grande entre las curvas de nivel indica que z cambia lentamente, mientras que un espacio pequeño indica un cambio rápido en z. Además, en un mapa de contorno, es importante elegir valores de c uniformemente espaciados, para dar una mejor ilusión tridimensional. USGS Figura 13.7 Figura 13.8 Larson-13-01.qxd 890 3/12/09 18:39 CAPÍTULO 13 Page 890 Funciones de varias variables Dibujo de un mapa de contorno EJEMPLO 3 El hemisferio dado por f sx, yd 5 !64 2 x 2 2 y 2 se muestra en la figura 13.9. Dibujar un mapa de contorno de esta superficie utilizando curvas de nivel que correspondan a c 5 0, 1, 2, . . . , 8. Solución Para cada c, la ecuación dada por f sx, yd 5 c es un círculo (o un punto) en el plano xy. Por ejemplo, para c1 5 0, la curva de nivel es x 2 1 y 2 5 64 Círculo de radio 8. la cual es un círculo de radio 8. La figura 13.10 muestra las nueve curvas de nivel del hemisferio. f(x, y) = 64 − x2 − y2 z z y c1 = 0 c2 = 1 c3 = 2 c4 = 3 Superficie: c5 = 4 c6 = 5 c7 = 6 c8 = 7 8 4 8 c9 = 8 12 x −8 10 −4 4 8 8 −4 6 4 8 x 2 4 4 x y −8 Hemisferio Mapa de contorno Figura 13.9 Figura 13.10 EJEMPLO 4 Superficie: z = y2 − x2 Figura 13.11 c= 0 c = −2 c = −4 c = −6 c = −8 c = −10 c = −12 y 4 x 4 −4 Curvas de nivel hiperbólicas (con incrementos de 2) Figura 13.12 El paraboloide hiperbólico dado por se muestra en la figura 13.11. Dibujar un mapa de contorno de esta superficie. c = 12 −4 Dibujo de un mapa de contorno z 5 y2 2 x2 Paraboloide hiperbólico c=2 y 8 Solución Para cada valor de c, sea f sx, yd 5 c y dibújese la curva de nivel resultante en el plano xy. Para esta función, cada una de las curvas de nivel sc Þ 0d es una hipérbola cuyas asíntotas son las rectas y 5 ± x. Si c < 0, el eje transversal es horizontal. Por ejemplo, la curva de nivel para c 5 24 está dada por x2 y2 2 5 1. 22 22 Hipérbola con eje transversal horizontal. Si c > 0, el eje transversal es vertical. Por ejemplo, la curva de nivel para c 5 4 está dada por y2 x2 2 2 5 1. 2 2 2 Hipérbola con eje transversal vertical. Si c 5 0, la curva de nivel es la cónica degenerada representada por las asíntotas que se cortan, como se muestra en la figura 13.12. Larson-13-01.qxd 1053714_1301.qxp 3/12/09 10/27/08 18:39 12:05 PM Page 891 Page 891 SECCIÓN 13.1 13.1 891 Introducción a las funciones de varias variables Introduction to Functions of Several Variables 891 Un ejemplo de función de dos variables utilizada en economía es la función de producción de Cobb-Douglas. Esta función se utiliza como un modelo para representar el Onedeexample a functionalof two las variables useddeintrabajo economics is the número unidadesofproducidas variar cantidades y capital. Si Cobbx mide las Douglas production function. This function is used as a model to represent the unidades de trabajo y y mide las unidades de capital, el número de unidades producidas numbers of units produced by varying amounts of labor and capital. If x measures the está dado por units of labor and y measures the units of capital, the number of units produced is f sx, yd 5 Cx a y 12a given by donde C y a son constantes, con 0 < a < 1. f x, y Cx a y 1 a EJEMPLO 5 a La de producción where C and are función constants with 0 < a < 1. de Cobb-Douglas z = 100x0.6y0.4 y y 2 000 0.6 y 0.4 80 000 c = 160 000 zc==100x c = 80,000 c = 160,000 2000 1 500 (2 000, 1 000) 1500 1 000 1000 (2000, 1000) 500 500 x 500 1 000 1 500 2 000 x (1 000, 500) 500 1000 1500 2000 (1000, 500) Curvas de nivel (con incrementos de 10 000) Figura Level curves13.13 (at increments of 10,000) Figure 13.13 f(x, y, z) = c3 f (x, y, z) = c3 f(x, y, z) = c2 f(x, y, z) = c2 z z f (x, y, z) = c1 f (x, y, z) = c1 Un fabricante de juguetes estima que su función de producción es f sx, yd 5 100x 0.6 y 0.4, EXAMPLE 5 The de Cobb-Douglas Production donde x es el número unidades de trabajo y y esFunction el número de unidades de capital. Comparar el nivel de producción cuando x 5 1 000 y y 5 500 con el nivel de producción A toy manufacturer 100x 0.6 y 0.4, where cuando x 5 2 000 y yestimates 5 1 000.a production function to be f x, y x is the number of units of labor and y is the number of units of capital. Compare the production Cuando level when 500dewith the production level when Solución x 5 1x000 1000 y y 5 and 500, yel nivel producción es x 2000 and y 1000. ƒ(1 000, 500) 5 100(1 0000.6)(5000.4) ø 75 786. Solution When x 1000 and y 500, the production level is Cuando x 5 2 000 y y 5 1 000, el nivel de producción es f 1000, 500 100 1000 0.6 500 0.4 75,786. ƒ(2 000, 1 000) 5 100(2 0000.6)(1 0000.4) 5 151 572. When x 2000 and y 1000, the production level is Las curvas de nivel de z 5 f sx, yd se muestran en la figura 13.13. Nótese que al doblar 0.6 producción ambas x y y, se duplica100 el nivel ejercicio 79). f 2000, 1000 2000de 1000 0.4 (ver 151,572. The level curves of z f x, y are shown in Figure 13.13. Note that by doubling both Superficies de nivel the production level (see Exercise 79). x and y, you double El concepto de curva de nivel puede extenderse una dimensión para definir una superficie Level de nivel. Surfaces Si f es una función de tres variables y c es una constante, la gráfica de la ecuación es auna superficie de be nivel de la función como se to muestra la figura fThe sx, y,concept zd 5 c of level curve can extended by one f,dimension defineena level 13.14. surface. If f is a function of three variables and c is a constant, the graph of the Ingenieros han desarrollado mediante formas de ver equation f x, y,yz científicos c is a level surface of the functioncomputadoras f, as shown inotras Figure 13.14. funciones de tres variables. Por ejemplo, la figura 13.15 muestra una simulación compuWith computers, engineers and scientists have developed other ways to view tacional paraFor representar distribución de temperaturas del fluido que functionsque of usa threecolores variables. instance, la Figure 13.15 shows a computer simulation entra en el tubo. that uses color to represent the temperature distribution of fluid inside a pipe fitting. y x y Superficies de nivel de f Level surfaces of f Figura 13.14 Figure 13.14 Imagen cortesía de CADFEM GmbH x TM y ANSYS Una forma común de One-way coupling of ANSYS CFX CFX™ and ANSYS Mechanical™ TM para análisis de esfuerzos térmicos. Mechanical for thermal stress analysis Figura Figure 13.15 Larson-13-01.qxd 892 3/12/09 18:39 CAPÍTULO 13 Page 892 Funciones de varias variables EJEMPLO 6 Superficies de nivel Describir las superficies de nivel de la función f sx, y, zd 5 4x 2 1 y 2 1 z 2. Solución Cada superficie de nivel tiene una ecuación de la forma 4x 2 1 y 2 1 z 2 5 c. z Superficies de nivel: 4x2 + y2 + z2 = c c=4 c=0 y x c = 16 Ecuación de una superficie de nivel. Por tanto, las superficies de nivel son elipsoides (cuyas secciones transversales paralelas al plano yz son círculos). A medida que c aumenta, los radios de las secciones transversales circulares aumentan según la raíz cuadrada de c. Por ejemplo, las superficies de nivel correspondientes a los valores c 5 0, c 5 4 y c 5 16 son como sigue. 4x 2 1 y 2 1 z 2 5 0 x2 y2 z2 1 1 51 1 4 4 2 2 x y z2 1 1 51 4 16 16 Superficie de nivel para c 5 0 (un solo punto). Superficie de nivel para c 5 4 (elipsoide). Superficie de nivel para c 5 16 (elipsoide). Estas superficies de nivel se muestran en la figura 13.16. Figura 13.16 NOTA Si la función del ejemplo 6 representara la temperatura en el punto (x, y, z), las superficies de nivel mostradas en la figura 13.16 se llamarían superficies isotermas. n Gráficas por computadora El problema de dibujar la gráfica de una superficie en el espacio puede simplificarse usando una computadora. Aunque hay varios tipos de herramientas de graficación tridimensionales, la mayoría utiliza alguna forma de análisis de trazas para dar la impresión de tres dimensiones. Para usar tales herramientas de graficación, por lo general se necesita dar la ecuación de la superficie, la región del plano xy sobre la cual la superficie ha de visualizarse y el número de trazas a considerar. Por ejemplo, para representar gráficamente la superficie dada por f sx, yd 5 sx 2 1 y 2de 12x 2 2y 2 se podrían elegir los límites siguientes para x, y y z. f(x, y) = (x 2 + y 2)e1 − x 2 − y2 23 ≤ x ≤ 3 23 ≤ y ≤ 3 0 ≤ z ≤ 3 z x Figura 13.17 y Límites para x. Límites para y. Límites para z. La figura 13.17 muestra una gráfica de esta superficie generada por computadora utilizando 26 trazas paralelas al plano yz. Para realizar el efecto tridimensional, el programa utiliza una rutina de “línea oculta”. Es decir, comienza dibujando las trazas en primer plano (las correspondientes a los valores mayores de x), y después, a medida que se dibuja una nueva traza, el programa determina si mostrará toda o sólo parte de la traza siguiente. Las gráficas en la página siguiente muestran una variedad de superficies que fueron dibujadas por una computadora. Si se dispone de un programa de computadora para dibujo, podrán reproducirse estas superficies. Larson-13-01.qxd 3/12/09 18:39 Page 893 SECCIÓN 13.1 z 893 Introducción a las funciones de varias variables z z x x y x y y Tres vistas diferentes de la gráfica de f sx, yd 5 s2 2 y2 1 x2d e12 x 2 s y y4d 2 z 2 y z x y x y x Trazas dobles Trazas simples Curvas de nivel Trazas y curvas de nivel de la gráfica de f sx, yd 5 2 4x x 1 y2 1 1 2 z z z y x y y x x f(x, y) = sen x sen y f (x, y) = − 1 + y2 x2 f (x, y) = 1− x 2 − y 2 1− x 2 − y 2 1053714_1301.qxp 10/27/08 12:05 PM Page 894 Larson-13-01.qxd 10/27/08 3/12/09 18:40 PagePage 894 894 1053714_1301.qxp 12:05 PM 1053714_1301.qxp 894 894 10/27/08 12:05 PM Page 894 Chapter 13 13 Functions Functions of of Several Several Variables Variables Chapter CAPÍTULO Funciones de variasVariables variables Chapter 13 13 Functions of Several Chapter 13 Functions of Several Variables 894 894 894 Seeofwww.CalcChat.com www.CalcChat.com for worked-out worked-out solutions solutions to to odd-numbered odd-numbered exercises. exercises. Exercises See for 13 Functions Several Variables Exercises See www.CalcChat.com for worked-out solutions to odd-numbered exercises. 13.1 113.1 3.1 Chapter Ejercicios 13.1 Exercises See www.CalcChat.com for worked-out solutions to odd-numbered exercises. In Exercises Exercises and 2, use use the graph to to determine whether is aa En los ejercicios 1 y2, usarthe la gráfica para determinar si z eszz is una x, yy sen yy 13. ff x, In 11 and graph determine whether xx sen 13. In13.1 Exercises use the graph to determine whether z is a f x, y x sen y function ofxxxExercises and Explain. y.2,Explain. función de y1and y.and Explicar. function of y. See www.CalcChat.com for worked-out solutions 13. to odd-numbered exercises. 2, 44 b) a) 2, b) a) In Exercises andy.2,Explain. use the graph to determine whether z is a function of x1and x sen y 13. f x, y 894 zz 1. 1. function of x and y. Explain. z 1. In Exercises 1 and 2, use the graph to determine whether z is a 1. 22 z function of x and y. Explain. 2 2z 1. 2 44 4 x x 4 x 2. 2. 2. 2. x 33 3 3 zz z 3 4 x 44 4 yy y 4 y 4 y 33 z 3 3 2. z 55 xx 5 x 5 x 3 55 5 5 5 x yy y y y. In Exercises Exercises 33––6, 6, determine determine whether whether zz is is aa function function of of xx and and y. In In Exercises 3 – 6, determine 5 whether z is a function of x and y. 2 de x y y. y En los determinar si esis22una función 3y223 – 6,3xxydetermine ya 6, 10 10 2x 3.Exercises 4.zxz xx22zzejercicios 3y 2x yy yy2of 4. zxz x 44and y. In3. whether a function 2 2 2 xz x y 10 2x y y 4 3. x222z 3y 4. 22 y x y 2 22 x 2xyyy 8yz y 2 400 3. 4. z x y 11 10 z 2 xx ln ln 8yz 5. xx22z y3y 6. zxz 2 z 5. 6. In5.Exercises whether of x and 2 determine 44 99 3 –z6, 1 ln y 8yz 0 y. 6. zz is ax function x42 y92 2 8yz zxz 2 x ln 5. x 2z 3y2 z x y 1 10 6. 2xyy values. y 2 40 4.the 4 9 7–18, In3.Exercises Exercises 7–18, find find and and simplify simplify the function values. In function 2 2 In Exercises find and simplify the function values. y 7–18, x 1 and simplify6.the z function x ln y values. 8yz 0 5. x, yy 7–18, xyz 2 find 7.Exercises f4f x, xy In7. 9 f ejercicios x, y xy 7 a 18, hallar y simplificar los valores de la funEn7.los 3, 2 1, 4 30, 5 a) b) c) 1, 4 c) 30, 5 a) 3, 2 b) f x, y3, 2 xyb) 7. a) 1, 4 c) 30, the 5 function values. ción. In Exercises 5, yy 7–18, x, 22 and simplify 5, tt d) 5, e) find x, d) e) ff )) 5, a) 5, 2y b) 2 422 fc)) 30, 5, t 5 d) 3, e) 22x, 1, x,x,yyy 44xy xx 4y 8. fff x, 4y 8. 7. f x, y5, y 4 e) x 2x, 24y 2 f ) 5, t 8. d) 0, 020 b) 0, 1, 2, 30, a) 0, b) 0, c) c) 2, 11 4 c) 33 5 a) 3, 8. fa)x, y0, 0 4 b) x 2 0, 14y 2 c) 2, 3 e) f ) 1, y x, 0 t, 1 t d) e) f ) 1, y x, 0 t, 1 d) 5, 2 f ) 5, 0, a) e) f ) 2, 1, 0y b) x, 01 2 c) t, 31 d) 0, y y 2 x, yy 9. ff x, xe 9. 4xe x 4y 8. x, 0 f ) t, 1 y f x, y1, y xee) 9. d) 5, 0 3, 2 2, 3 11 a) b) c) 2, 5, 0 3, 2 a) 0, b) 0, 1 c) y 9. fa)x, y5, 0 xeb) 3, 2 c) 2, 1 5, yy e) x, 202 ff )) t,t, tt1 d) 5, e) x, d) 1, a) 5, 0y b) x, 22 c) t, t 1 d) 5, e) 3, f ) 2, y g x, y ln x 10. g x, y ln x yy 10. xe 9. f f ) t, t g x, y5, y lne)x x,y 2 10. d) 1, 00 b) 0, 2 11 c) c) 0, ee1 a) 1, b) 0, c) 2,0, a) 5, 3, y 1 c) 0, e 10. ga)x, y1, 0 lnb)x 0, 1, 1 e, e 2 d) e) f ) 1, 1 e, e 2 2, d) 5, y e) x, 2 f )f ) t, t2, e55 a) 1, 01 b) e, e 12 fc)) 0, 2, 5 d) 1, e) 0, xy ln xy x y 10. g x, y 1,zz1 e) e, e 2 2, 5 h x, x, y, y, 11. hd) f ) 11. xy h x, y, 11. a) 1, z0 b)zz 0, 1 c) 0, e xy z ha)x, y, 11. a) 2, 3, 0, 11 f ) c) 2, 3, 3, 44 d) 5, 4, 4, 66 b) e, 1, c) 2, 5 2, d) 5, 2, 1, z3, 1 99 e) b) e1, 20, d) 2, 3, 4 d) 5, 4, 6 a) 2, 3, 9 z b) 1, 0, 1 c) x, y, y, zz 12. ff x, xx yy zz 12. 2, z3, 9 xyb) 2, 3, 4 d) 5, 4, 6 x y1, 0, z1 c) 12. a) hf x, y, 11. 0, 5, 5, 44 z b) 6, 8, 8, 33 a) 0, b) 6, a) 12. fa)x, y,0,z5, 4 xb) y6, 8,z 3 4, 6, 6, 292 d) 10,0, 14, 4, c)33 c) 4, d) 10, c) 2, 3, 1, 2, 3, 4 d) 5, 4, 6 a) b) a) 4, 5, 6, 42 b) 10,8, 4,3 3 c) 0, d) 6, x y z 12. f x, y, z c) 4, 6, 2 d) 10, 4, 3 a) 0, 5, 4 b) 6, 8, 3 c) 4, 6, 2 d) 10, 4, 3 3, 11 c) 3, 33 d) 4, 22 c) d) 4, 3, 3, 3, 3 d) 4, 2 a) 2, 4 22 b) 3, 1 c) V r, h r h V r, h r h 3, 3 d) 4, 2 a) V r, h2, 4 r 2hb) 3, 1 c) 3, 10 10x sen 5, 22 c) 4, 88 d) 6, 44 b) c) 4, d) 6, a) b) fa)x, y3, 2hy 5, V r, h r a) 3, 10 yy b) 5, 2 c) 4, 8 d) 6, 4 2, 4 b) 3, 1 c) 3, 3 d) 4, 2 a) 3, g x, x, yy 10 y b) 2t 5,332dt dt c) 4, 8 d) 6, 4 15. ga) 2t 15. g x, 15. V xxyr 22t r, hy h 3 dt 14. 3 ga)x, y4, 2t 4, 15. a) 4, 010 0 xb) 4,5,3112dtc) 4,4,3232 8 d) b)b) c)c) 4, d)d) 3223,,6,00 4 3, a) 3 4, 1 4, a) 4, 0 xyb) c) d) y 2 2, 0 y 1 1 3 3 y 4, 0 4, 1 4, ,0 a) b) c) d) g x, y dt 16. g x, y dt 16. 2 2 1 2tt 3 dt 15. g x, y 16. g x, y xxxy t dt 1 t 1 ga)x, y4, 16. a) 4, 101 xb) 6, 313 c) 2, 535 d) b) dt c) 2, d) 31221,,, 077 6, d) 4, 4, a) b) c) t 4, 2 6, 3 2, 5 a) 4, 1 xb) c) d) 22, 7 22 2 x, yy 2xy 1 yy2 x, yy1 3x 2y 17. ff x, 18. ff x, 3x 2x 2y 17. 18. c) 2, 518. d) 2 3 f x, y2, 7 3x2 2y 17. a) gf x, y4, 1 2xb) ydt6, 16. x,tyy x, yy x, yy x, yy ff xx x, ff x, ff xx x, ff x, fa)x, yf x 3x2x, y 2y f x, y fa)x, yf x 2xx x, yy2 f x, y 17. a) 18. a) 1 xx a) f4,x1 b)x, yxx6, 3 f x,c)y 2, 5 a) d) f2,x7 x, yx f x, y x a) a) x, yy2x yyy2 ff x, x, yy x, yy3x2 yy 2y ff x, x, yy fb)x, yff x, fb)x, yff x, 17. b) 18. b) f x, y yyxy f x, y f x, y yxyy f x, y b) f x b) f x x, yyy ff x, x, yy x, yyy ff x, x, yy a) f x, y a) f x, y b) b) x x y deof In Exercises 19–30, describe the eldomain domain and range of the In 19–30, the range En Exercises los ejercicios 19y a describe 30, describir dominioand y rango la the funIn Exercises 19–30, describe the domain and range ofx,the function. f x, y y f x, y f x, y y f y function. ción.b) b) In Exercises 19–30, describe the domain and range of the function. y y 2 2 xy x, yy x, yy 19. ff x, 20. ff x, eexy xx2 yy2 19. 20. function. x2 y2 e xy 19. f x, y 20. f x, y In Exercises 19–30, describe the domain andxy yy range of the ey xx2 yy y 2 19. 20. x, yy x, yy 21. gfg x, 22. gfg x, 21. 22. function. xx x y 21. g x, y 22. g x, y yx g x, y x y g x, y 21. 22. x y xy 2 2 xy x y xy y 19. 20. 23. zfz x, yx yx 24. zfz x, y xy e x 23. 24. xy xy 23. z 24. z xx yy y xy xy yx y 22 2 g x, x, yyyx xy y 44 xx22 4y 21. 22. 2 23. 24. x, yy 4y22 x, 25. fzf x, 26. fzgf x, 44 xx yy 25. 26. x xy 2 2 4 x y 25. f x, y 26. f x, yx y 4 x 2 4y 2 x, yyx yarccos arccos xx2 yy 2 x, yy xy arcsen arcsen yy2 xx 27. ff x, 28. ff x, 27. 28. 4 xx yy 4 xy x 4y 2 25. 26. x, yy arccos x, yy arcsen 27. fzf x, 28. fzf x, 23. 24. x, yy xy ln ln 44 xx yy x, yyx yln ln xy xy 66 29. ff x, 30. ff x, 29. 30. arccos arcsen 27. 28. x, yy ln 4 xx2 yy 2 x, yy ln xy y26x 29. ff x, 30. ff x, x, y 4 x y 4y 2 f x, y 4 x 25. ff x, 26. y About ln 4 It y b), xy and 29. 30. f x,a), 31. Think Think About It xThe Theygraphs graphs labeled labeled a), b),lnc), c), and6 (d) (d) are are 31. fThink x, y About x They graphs x,a), y xx22b),arcsen 27. 28. f 4x 31. graphs are 22 and yc), 1y ..x(d) f x, x, yy labeled 4x graphs ofarccos theItfunction function Match y 1 f of the Match 31. Think Para pensar Las gráficas marcadas a), b), y2d) and son gráficas 2 c) c), 31. About It The graphs labeled a), b), (d) are y 1 . f x, y 4x x of the function Match thex,four four graphs with the points in space from which the surface fgraphs y ln 4 x y f x, y ln xy 6 29. the 30. graphsf swith pointssxin2 1 space from which the surface 21 de la función gráfix, yd the 5 24xy y4x d. Asociar 2 1cada .10, f x, yare x1225 graphs of the Match the four graphs with points in space from the surface 20, 15, 25which 15, 10, 20 ,, is viewed. viewed. Thefunction fourthepoints points are 20, 15, ,,ysuperficie 15, 20 is The four ca con el punto en el espacio desde el que la es vifour graphs the0points in space from the 10, surface 20,a), 15, 25which , c), and 15, is20, The four are 31. the Think Itwith The graphs labeled b), (d) 20 are, 20,viewed. 20,About 0 ,, and 20, 0, 0points . and 20, 0 20, 0, . sualizada. Los cuatro puntos son (20, 15, 25), (215, 10, 20), 20 , is Thefunction four0, points 20,viewed. 20,of 0 ,the 20, 0 f. x, yare 20, and 1 .10, 4x15,x 225 , yzz2 15, graphs Match zz (20, a) b) a) b) (20, 20, 00), yand 0, 0, 0) 0 . 20, 20, 20, z z the four graphs with the points in space from which the surface a) b) z a) viewed.z zThe four points b) b) 20,xx15, 25 , z 15, 10, 20 , is are a) x x 20, 20, 0 , and 20, 0, 0 . x 14. 14. 14. 13. 14. z a) y yy y x y y Generated by by Maple Mapley Generated Generated by Maple Generada con Maple zz Generated by Maple c) c) c) c) c) z z Generated by Maple z c) xx x x z x yy y y y Generated by by Maple Maple Generated Generated by Maple Generada con Maple y Generated by Maple z b) yy y y d) d) d) d) d) y d) xx x x Generated by by Maple Maple Generated Generated by Maple Generada con Maple zz Generated by Maple z z z Generated by Maple x x z y yy y y y Generated by by Maple Maple Generated Generated by Maple Generada con Maple Generated by Maple x Generated by Maple Generated by Maple CAS Larson-13-01.qxd 3/12/09 18:40 Page 895 895 1053714_1301.qxp 10/27/08 12:05 PM Page 1053714_1301.qxp 10/27/08 12:05 PM Page 895 01.qxp 10/27/08 12:05 PM Page 895 1301.qxp 10/27/08 12:05 PM Page 895 1053714_1301.qxp 10/27/08 _1301.qxp 10/27/08 12:05 PM Page12:05 895 PM Page 895 13.1 to of Variables 895 13.1 Introduction to Functions Functions of Several Several Variables 895 SECCIÓN 13.1 Introduction Introducción a las funciones de varias variables 895 13.1 Introduction to Functions of Several Variables 895 13.1 Introduction to Functions of Several Variables 895 13.1 Introduction to Functions of Several Variables 895 2 2 32. 2 xxx2 2 12y 13.131. Variables 895 32. Think Think About About It It Use Use the the function function given given in in Exercise Exercise 31. Introduction to Functions of Several 2y 2y 2 ff fx, xx2x2 2 ff fx, 47. 48. x, lnlnyyof x, cos 47. 48. 32. Think ParaFind pensar Usar laand función dada enfunction. elinejercicio 31. 47.to 48.Several sIntroduction x,yyyd 5ln y 2Several sx,yyyd895 5cos cosx 2 442y 2 895 13.1 to Functions of Variables 32. About It Use the function given Exercise 31. 13.1 Introduction Functions Variables (a) the domain range of the FindAbout the domain and of the function. 32. (a) Think It Use therange function given in Exercise 31. lnz y x 2 2 f x, 2y cos x 2 4 2y 2 47. f x, y 48. 32. Think About It Use function given in Exercise 31. a) the Hallar el domain dominio y rango de la función. f x, y zz zcos 47.2 f x, y x 248. 2y zln 4 (a) Find the and range of the function. xy(b) Identify the points in the plane at which the function z y f x,xy xy(b) Identify the points in the plane at which the function 4 f x, y ln y x cos 47. 48. (a) the Findfunction the domain and range of the function. 32.(a)Think It b) Use given inenExercise 31. x 24 2y 2 z z Identificar los puntos el plano xy donde el valor de la funFind About the domain and range of the function. 5 value is 0. 2 55 z 48. f x, y value is the 0. points in the xy-plane at which the47.function (b) Identify 44 z f x, y ln y x cos Identify the points the xy-plane the31. function z 32. Think About Itthe Use the given Exercise 32.(a) Think It (b) Use the given in function Exercise 31. atinwhich x 2 2y 2 z x 2 4 2y 2 4 ción esisfunction 0. FindAbout the and range of function. xy(b) Identify thedomain points in the plane atpass which the function 0.surface (c) Does the through all f x, y ln y47. xf 2 x, y 5 5 ln y48. xf 2x, y cos 48. f x, y 4 cos 47.rectan(c) value Does the surface pass through all the the octants octants of of the the rectanvalue is 0. z z 4 4 4 Find the domain and range ofreasons the function. c)(a)¿Pasa la superficie por todos los octantes del sistema de coor(a) Find thethe domain and range ofplane thesystem? function. xy(b) Identify points in the the at through which the function value is 0. gular coordinate Give for answer. −−66 4 gular coordinate system? Give reasons for your your answer. (c) Does surface pass all the octants of the rectan- 5 −6 z z z z (c) Does the surface pass through all the octants of the rectandenadas rectangular? Dar las razones de la respuesta. value 0. the points xy(b) Identify points the plane atforwhich the function 5 xy-plane Identify incoordinate the the atinwhich the function 4 yy (c) (b) Does theissurface pass through all the octants of the rectangular system? Give reasons your answer. −6 gular coordinate system? Give reasons forthe your answer. y −6 In Exercises 33 – 40, sketch the surface given by function. 5− 6 value is 0. 3 22 value is 0. In Exercises 33 – 40, sketch the surface given by the function. 4 (c)gular Does the En surface pass through octants the rectancoordinate Give for your answer. 4 lossystem? ejercicios 33reasons aall 40,the dibujar la of superficie dada por la función. 5 55 444 33 2 y 10 5 y 1010 2 xx Insurface Exercises 33through –Give 40, sketch the surface given by the function. system? reasons for your − 6 444 55 6 Does the surface pass through all octants of the rectan(c)gular Doescoordinate the pass all the octants rectany x5 4 3 3 2 −2 33. 34.ofanswer. ff (c) x, 4433 ff the x, yythe 6by 2x 3y In Exercises – 40, sketch the surface 5 66 yy y xx x, yythe x,given 6 the 2xfunction. 3y 2 −2 −2 10 In Exercisesgular 33 – coordinate 40,33. sketch surface given by for the 34. function. 5 4 x6 4 3 gular coordinate system? Give reasons for your answer. x −10 system? Give reasons your answer. − 6 1 y 4 5 6 2 1 5 y 4 x 33. 34. f x, y 4 f x, y 6 2x 3y 2 −2 fff x, ggf x, 36. 5 6 x x,x,yyy theyy4surface given by the x, 35. 36. In Exercises 33 –35. 40, y 33.sketch 34.function. x,yyy 226yy 2x 3y −2 10 4 5 3 2 x x 4 y y of the function. 5 y 6 In 49–56, 33. f x, y 4 6 2x 3y 11 x 221 by 2 22f x, y −2 22 In4Exercises Exercises 49–56, describe the the level level curves curves of the function. x 10 describe x, y xx22the y34. gzfunction. 37. 38. In 33 – 40, sketch surface the function. In Exercises 3335. –37. 40,fzExercises surface giventhe by36. the 2yy x 3 2 zfsketch zgx,x,ygiven 38. 22y x 2 y1 yyy 3 2 5 x, y y 35. 36. 4 4 1 EnExercises ejercicios a 56, las curvas de nivelfunction. de la funy level 5los 2 6 the c-values. Sketch curves for the given 34. f x, y y6 2x 3y f x, 5 −2 1 Sketch the level curves fordescribir thethe given In 49–56, level curves of the x 49 y y y 2 4 37. 35.33.f x, 10 c-values. 10 4describe 2 z x, yy x