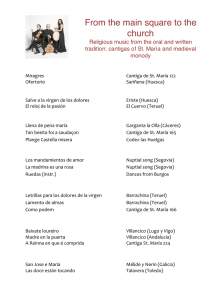

PDF - Andrew Cashner

Anuncio