Evaluation of the Commission of the European Union`s co

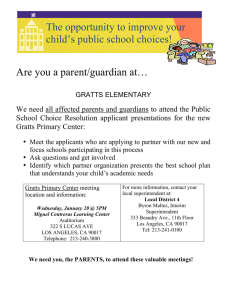

Anuncio