- Ninguna Categoria

Safe Oxytocin Administration: Best Practices & Guidelines

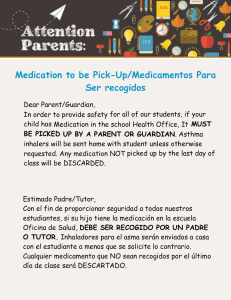

Anuncio