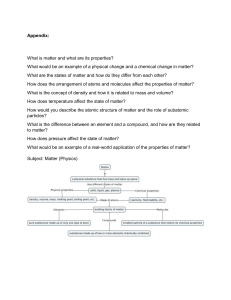

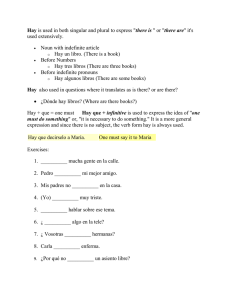

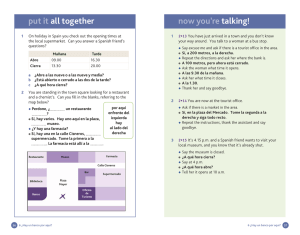

Moving Along the Proficiency Continuum Harnessing Creativity and Play to Move Proficiency Forward for Novice and Intermediate Students By Victoria Gilbert “Yo primero sombrero” (I first hat) says the novice student arriving in my classroom where (in our circus unit) the clown props are given out to first five in the door. How do we get our students to start speaking the target language from the start? Make them feel that they can use whatever language they have to enter the conversation, even if it is just responding to the teacher with a reciprocal, “Buenos días.” Many students study a language, though not all manage to become functionally proficient in it. In my experience, we need to create space for students (of all ages) to play with language, especially at Novice and Intermediate levels. Not playground or doodling play, but rather the type of play that allows for students to share their originality and wit, and to express their humanity for the sheer joy of it, using the target language as a vehicle for their expression. 44 The Language Educator n Jan/Feb 2015 According to Dutch cultural theorist Huizinga (1949), play must occur in limited time, in a circumscribed place and be done for its own sake. The first two factors are aspects of most classes, while the latter often is not. Students can take pieces of what they have memorized and learned and apply them in new ways to make it their own when nothing more is at stake. When students are faced with a task that is to be assessed (formally or informally), the stakes go up and their willingness to take a risk by inventing original expression decreases. If the teacher can provide for moments of real play with language, for its own sake, the affective filter (Krashen, 1982) is reduced and taking risks becomes more possible. To form original expressions, students must be willing to deconstruct and reconstruct new combinations based on existing vocabularies. If they become so engaged in accomplishing this that they disregard the form for function, stress levels will fall, and students will persist longer in maintaining communication. Students may do this through repetition of structures they have already mastered, varying the arrangement of known segments and connect- 1. ing them to newer ones that they are focused on assimilating. For example, in a primary classroom, students may quickly co-opt the expression, “Quiero ser la gallina” (I want to be the chicken) in a song role-play with puppets to “Quiero ser voluntario” (I want to be the volunteer for the next activity). The goal from their perspective is being able to participate in a game; the use of target language is the vehicle for their participation. For the Novice range and Intermediate Low to Mid levels, this is the key to moving proficiency along. Miller (2003) reminds us that as soon as one has learned how something is supposed to be, turning it upside down or distorting it in some way becomes a source of fun. One student in my class teased the class puppet by singing the “goodbye” song at the start of class instead of the “hello” song, once he learned the difference. These same pre-K students have taken to requesting more water (during Spanish snack time) by saying, “más agua, por favor,” only to reveal a full cup with a giggle. Or, after learning the words for “big” and “small” in discussing fruits and pumpkins, they point to me and say “big.” I point to Have students create a song using thematically related vocabulary to a known tune. Provide scaffolding for students with rhyming word lists and synonyms for key words. In these examples, all words are cited exactly as fourth grade students wrote them for a unit on birthdays. The Novice students were given a model and the chart below the song to use for inspiration. Their first efforts to the tune of “Row, row, row your boat” are below: Version 1: Hay . . . hay un tarta y muchos regalos / El gordo cachoro come los amigos. Version 2: Hay . . . hay una bicicleta muy pequeña / y muchos, muchos, muchos regalos para mis amigos. Words that rhyme -os Words that rhyme -a Other key words globos tarta feliz amigos familia Casita de árbol regalos fiesta Es cumpleaños caja Hay años pequeña grande cachorror(s) bicicleta enorme Vela(s) recibe them and say “small.” Teachers have to be ready to jump into the play and extend the new patterns that students invent. Children experiment with applying general patterns to new circumstances, and play provides an opportunity to experience situations from numerous points of view as often occurs during a role-play. So not only is play important for building proficiency, it can also help students to inhabit new cultural viewpoints. For language students of any age, acting more childlike can help students enter into those creative proficiency-building moments. Using props, masks, or clothing/costumes helps students enter a new world for a moment. These moments occur when students disregard exactly how they are supposed to say something and just try it to express it. Using language is the only way to make it your own. Teachers can adopt techniques to spark creativity in their classrooms in many ways. Some are suited to interpersonal tasks, others to interpretive or presentational communication. Even at the Novice level, students can be original and creative. Here are some ways to play with language or “turn things upside down”: or free time activity. Accept any premise, no matter how ridiculous or fanciful; the point is to have the characters relate to one another and have the students use the target language in improvisational and spontaneous ways. 3. Create a shape poem using newly acquired vocabulary or allow students to literally lay cut-out words in ways that make sense to them. This works particularly well in a thematic context where students can connect the words in related ways as they present their shape poems. 2. Have students adopt identities with visuals to represent them, (e.g., famous athlete, actress, cartoon character, another teacher or administrator from the school’s community) and then make up what the two will discuss when they meet. This can be related to any subject currently being studied in the classroom, from having them ask and answer about their birthdays to discussing their favorite food The Language Educator n Jan/Feb 2015 45 Moving Along the Proficiency Continuum Performance á la mode ALWAYS uses sentences! A sentence Lists and phrases Words How many scoops will you choose? INTERMEDIATE LOW NOVICE HIGH NOVICE MID NOVICE LOW “Busco mi nariz“ “It's not a bad day.“ Whether it is with interpersonal, interpretive, or presentational tasks, humans use language to express who they are and make a connection to others. Teachers can capitalize on this greatest of human needs by showing students a road map for how to use the target language in their search for a connection. Teachers can design learning environments that provide opportunities for students to exercise their creativity while completing a craft project or playing games on teams with each other or with partners. By continually raising the ante required to participate in the project or win games from word level to sentence to connected sentences, the craft project or game performance in and of itself become the moments to push proficiency forward. Moving language proficiency along also depends upon students having a sense of how the path ahead of them looks. Teachers need to provide opportunities for students to rephrase or paraphrase with controlled context or content until the responsibility can be released to the students. For example, if the unit goal is to have students be able to describe a birthday party setting, it is important to provide models of descriptions and opportunities to create with fragments, before finally removing the scaffolding to see what students can do independently. This task can be higher-order thinking by comparing birthdays across home and target cultures rather than simply describing. Novice students need to experience language just beyond their level with comprehensible support such as visuals or patterns of phrasing so that they can reach it eventually. Elementary students can even be given a metaphor for their developing language performance ability such as the “ice cream cone” used in the Shelby County Schools district (left). Teachers guide students in this construction by providing models, showing different formats, and connecting students to meaningful context worthy of building a road to reach the next destination. But we cannot forget that it is the students’ minds that must individually construct those roads. So how do teachers move students along on their proficiency? Let’s examine the aspects of classroom context where teacher choice has the greatest impact on student performance. In the interpersonal realm, students need exposure to playful turns-of-phrase such as those used in advertising, proverbs, and other examples of authentic text. The challenge of finding examples that are at the correct level for one’s students remains, but it is possible. In one such project, students were invited to adopt traditional sayings in authentic ways in class discussions. The degree of cooperation and playful exchanges among Intermediate speakers to set up an actual opportunity to use the proverbs was inspiring. The sense of accomplishment when they were able to say “Querer es poder” (Where there’s a will, there’s a way) or “Más vale tarde que nunca” (Better late than never) demonstrated their natural ability to negotiate the meaning of the culturally authentic saying and the tradition of using proverbs as a shorthand for longer commentary. Presentational tasks can offer students the opportunity to incorporate their understanding of the target culture and the assimilation of turns of phrase and expression typical in the target language. For example, in one class, students applied dictum of the Spanish language signs of the NYC Metropolitan Transit Authority (“If you see something, say something”) to the hazards of school life such as serving food that has been vetted for nuts or following the dress code. Another example of this is when a Novice student who used a past vocabulary word, “nariz” in an unexpected way with a new verb “buscar” to generate a comical sentence, “Busco mi nariz” (I search for my nose), which he then illustrated by crossing his eyes! In the Interpretive Mode, students enjoy seeing playful videos, comics, memes, reading jokes, or other “fun” varieties in the target language. If we provide a thematically based context and include authentic materials of this type that relate to the theme, teachers can accomplish several tasks at once. It is important to include visual images that represent the more abstract, linguistic notions. Students will use these visuals as a type of inter-language. It also helps them to “borrow” an understanding of the new target expression. Even abstract words can have a visual reference point as long as the teacher designates and maintains the same reference for the same word or expression each time. Some examples are an eye to represent “Hasta la vista” and distinguish it from “Hasta luego” which could be represented by a clock face with hands showing elapsed time. The standard red “prohibited” circle with a slash mark through it also makes it easy to designate what something is not (e.g., “It’s not a bad day.”) Language targets are important to set when planning for your classes, but how students arrive at those targets can be the result of 90% preparation and 10% inspiration, or the reverse. When students begin to use language in personal ways and for authentic purposes, we can no longer script their responses; we can only provide the building blocks for the road they will create along the journey to greater proficiency. Author ID to come References Huizinga, J. (1949) Homo ludens: A study of the play element in culture. Retrieved from http:// art.yale.edu/file_columns/0000/1474/homo_ ludens_johan_huizinga_routledge_1949_.pdf 46 Krashen, S. (1982) Principles and practice in second language acquisition. Retrieved from http:// www.sdkrashen.com/content/books/principles_ and_practice.pdf Miller, E. (2003) Verbal play and language acquisition. Retrieved from http://www. storytellingandvideoconferencing.com/17.html The Language Educator n Jan/Feb 2015