Arquitectura funcional de la cognición

Anuncio

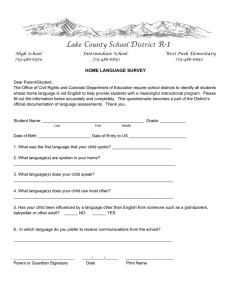

Arquitectura funcional de la cognición Joaquín Fuster (2003). Cortex and mind. Módulo V. Precursores del aprendizaje de la lengua escrita Dr. Miguel Ángel Villa Rodríguez Residencia en Neuropsicología Clínica Programa de Maestría y Doctorado en Psicología Facultad de Estudios Superiores Zaragoza, UNAM ì 2 Aproximaciones a la cognición Innato Aprendido Jerárquico Horizontal Paralelo En serie Módulos Redes Convergencia Divergencia 3 Representación Procesamiento Conocimiento 4 Memoria Percepción Atención Lenguaje Misma representación diferente procesamiento Funciones ejecuJvas (razonamiento, autorregulación, emociones, conducta social) 5 6 Pirámide de la percepción 7 8 9 Percepción ì La neurociencia considera a la percepción como un control de arriba hacia abajo (top-­‐down) de las entradas sensoriales. ì La percepción no sólo está bajo la influencia de la memoria, en sí misma es memoria. ì Es la actualización de la memoria. ì Percibimos lo que recordamos tanto como recordamos lo que percibimos. ì Cada percepto (experiencia percepJva) es un evento histórico. Una categorización de la experiencia sensorial presente. 10 Reconocimiento Nueva categorización (memoria) Percepto La percepción es un proceso acJvo ì 11 12 ¿Qué es la percepción? Proceso acJvo que consiste en integrar sensaciones en patrones significaJvos que representan hechos y fenómenos externos. 13 14 Paris, Francia, 1934-­‐2002 Jean-­‐Pierre Vasarely conocido profesionalmente como Yvaral, fue un arJsta francés que trabajó en los campos del pop-­‐art y el arte cinéJco desde 1945 en adelante. Era hijo de Victor Vasarely. Yvaral estudió arte gráfico y publicidad en la Ecole des Arts Appliques, entre 1950 y 1953. En 1960, Yvaral co-­‐fundó el Groupe de Recherche d'Art Visuel (GRAV) con Julio Le Parc, Francois Morellet, Francisco Sobrino, Horacio García Rossi y Joel Stein, buscando desarrollar un lenguaje visual abstracto coherente compuesto por elementos geométricos simples. 15 16 17 18 Constancias perceptuales ì Constancia de tamaño: tamaño percibido de un objeto que se manJene inalterado a pesar de los cambios en su imagen reJniana. ì Constancia de forma: forma percibida de un objeto que no se ve alterado por los cambios en la imagen reJniana. ì Constancia de brillantez: brillantez aparente (relaJva) de los objetos, no cambia mientras estén iluminados por la misma canJdad de luz. 19 Principios de la gestalt ì Cercanía ì Semejanza ì ConJnuidad ì Cierre ì ConJgüidad ì Región común 22 Mi mujer y mi suegra 23 25 29 Eleanor Jack Gibson El abismo visual PROSOPAGNOSIA ì Incapacidad para reconocer rostros pese al funcionamiento intelectual intacto e incluso al aparentemente intacto reconocimiento visual de la mayoría de los otros esdmulos. Bodamer 1947. Damasio y col (1982) plantean una lesión BILATERAL Y SIMETRICA de ambos hemisferios en la región occípito-­‐temporal compromeJendo los giros lingual y fusiforme. 38 Ciclo percepción-­‐acción ì La percepción puede llevar a otros actos cogniJvos como atención, memoria de trabajo, MLP u otras percepciones; o puede llevar a una acción. ì Depende de: ì Las condiciones internas del organismo (pulsiones y moJvaciones) ì Las asociaciones del percepto con conductas, cogniciones o emociones 39 Medio ambiente 40 Memoria ì 41 Conocimiento vs memoria ì El conocimiento es la memoria de hechos y de las relaciones entre ellos, que como toda memoria se adquiere por la experiencia. ì El conocimiento, a diferencia de la memoria autobiográfica, no está constreñido por el Jempo. ì Los eventos mnésicos (memoria) Jenen una fecha y cursan por un proceso temporal de consolidación antes de que se almacenen permanentemente o se vuelvan conocimiento. ì El conocimiento establecido es atemporal, aunque su adquisición y consolidación no lo sea. 42 Conocimiento vs memoria Memoria semánJca Conocimiento (no está sujeto al Jempo) Memoria episódica Memoria de eventos, autobiográfico (sujeta al Jempo) 43 Memoria ì No hay ningún recuerdo que sea estrictamente nuevo. ì Cualquier experiencia de memoria se forma siempre sobre un conocimiento preexistente. ì Toda percepción implica memoria, en tanto que es una interpretación del mundo de acuerdo a nuestro conocimiento previo. Las experiencias sensoriales se clasifican inmediatamente según el conocimiento previo. ì Así, un percepto nuevo lleva a una nueva memoria que se construye sobre memorias anteriores. 44 Percepción, conocimiento y memoria ì Desde el punto de vista de la neurobiología el conocimiento, la memoria y la percepción comparten el mismo sustrato neuronal. Un inmenso entramado de redes cor;cales (cognits) que con;enen en su tejido estructural el contenido informa;vo de los tres procesos (Fuster, p. 112). ì Las memorias almacenadas son redes corJcales. ì Se forman de la misma manera que todos los cognits. 45 Formación de la memoria ì La memoria es fundamentalmente una función asociaJva. ì El procesos biojsico subyacente es la modulación y transmisión de información a través de las sinapsis, que son los elementos neuronales que asocian anatómicamente a unas células con otras. (Hebb, 1949; Kandel, 1991). ì La atención, el ensayo, la repeJción y la prácJca son operaciones cognosciJvas que fortalecen las sinapsis que forman las redes de memoria en la corteza. 46 Modelo de la memoria humana propuesto por Atkinson y Shiffrin (1968) 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 Resumen ì Las memorias (los recuerdos) se forman en redes corJcales por principios y mecanismos asociaJvos. ì Las redes de memoria percepJva están organizadas jerárquicamente en la corteza asociaJva posterior. ì La recuperación de la memoria consiste en la reacJvación de la red asociaJva, estos es: el aumento de la excitabilidad y capacidad de disparo de sus neuronas. ì La conducta organizada es el producto la acJvación conjunta de las redes de memoria percepJvas y ejecuJvas. 56 Diagrama esquemáJco de la distribución corJcal de las representaciones cognosciJvas. La figura de arriba muestra el orden jerárquico de las memorias por su contenido. La figura de abajo muestra, en las áreas de Brodmann y con los mismos códigos de color de la figura de arriba, la distribución aproximada de los contenidos mnésicos en la superficie lateral del cerebro. RF= Fisura de Rolando 57 Atención ì 58 Funciones de la atención Selección Vigilancia Control 59 Atención Estructuras comprome`das Tallo cerebral Sistema re`cular Regiones Cerebrales anteriores Regiones Cerebrales posteriores 60 Modelos de la atención ì La atención es un sistema ampliamente distribuido en el cerebro: incluye el tallo cerebral el sistema reJcular acJvador y regiones corJcales anteriores y posteriores. ì Luria (1973) propuso la existencia de dos sistemas atencionales en el cerebro. ì ì Un sistema reflejo o que responde a esdmulos biológicamente significaJvos del ambiente que se caracteriza por la rápida habituación y por no requerir para su funcionamiento eficiente del procesamiento cognosciJvo de alto nivel. Es la atención involuntaria o refleja. Un sistema de atención voluntaria que implica la interpretación personal de los esdmulos ambientales. Está mediado por funciones cognosciJvas complejas. ì Ambos sistemas funcionan en paralelo, permiJendo la monitorización del ambiente para dar respuestas oportunas. ì No especifica el patrón de desarrollo, sólo que primero aparece el sistema más primiJvo. 61 Michael Posner (1978) ì Propone también un sistema dual. ì Un sistema predominantemente localizado en la corteza posterior (LP) y en partes del tálamo y del cerebro medio. Este sistema controla la atención selec`va y dirige los cambios en la atención espacial. ì Este sistema funciona desde muy temprano en el desarrollo humano. Desde los 4 meses según estudios con PET ì El segundo sistema es anterior, es un sistema de orden superior con ligas neurales importantes con el sistema posterior. Se asocia con el incremento de la intensidad dirigida a tareas parJculares Sistema de orientación Preparación para el input sensorial venidero Control ejecu`vo Vincula al sistema límbico y las áreas “racionales” Dirige los procesos neurológicos del aprendizaje Sistema de alerta Suprime los esbmulos de fondo, e inhibe las ac`vidades irrelevantes Devinsky & D’Esposito, 2004:104 63 64 65 66 Lenguaje ì 67 Evolución del lenguaje ì Es la úlJma fuente y producto de la civilización. ì Es poco probable que el lenguaje tenga una organización modular en el cerebro (áreas del lenguaje) ì Es claro que el lenguaje es el principal medio de comunicación de la especie, pero esto no quiere decir que sólo sea un medio de comunicación. 68 ì “ A u n q u e r e s p o n d e a predisposiciones biológicas, el lenguaje humano no aparece de repente, sino que emerge gradualmente durante el curso de un prolongado aprendizaje. Este aprendizaje implica 14 horas diarias de una inmersión en un flujo familiar o social de esdmulos lingüísJcos, que después de la edad de 5 años normalmente incluye una e d u c a c i ó n b a s a d a esencialmente en el lenguaje”. ì Aphasiology, p. 1 69 Evolución del lenguaje ì La invención del lenguaje y de la escritura significó un enorme paso evoluJvo en la complejidad del substrato neuronal de la comunicación animal. ì Es cuesJonable que el lenguaje tenga una organización corJcal diferente al de las otras funciones cognosciJvas. ì Las representaciones lingüísJcas son redes corJcales (cognits) y las operaciones como la sintaxis, la comprensión, la lectura o la escritura consisten en transacciones neuronales dentro de y entre las redes corJcales. Brain Research Reviews 25 Ž1997. 381–396 70 Full-length review Brain Research Reviews 25 Ž1997. 381–396 The evolutionary origin of the language areas in the human brain. A neuroanatomical perspective Full-length review ) 1 The evolutionary originAboitiz of the language areas in´ the brain. A Francisco , Ricardo Garcıa V. human perspective Programa de Morfologıa, Facultad de Medicina, UniÕersidad de Chile. Independencia 1027, Casilla 70079, Santiago ´ Instituto de Ciencias Biomedicas, ´neuroanatomical 07, Chile Francisco Aboitiz ) , Ricardo Garcıa ´ V. 1 Accepted 21 October 1997 Programa de Morfologıa, Facultad de Medicina, UniÕersidad de Chile. Independencia 1027, Casilla 70079, Santiago ´ Instituto de Ciencias Biomedicas, ´ 07, Chile Accepted 21 October 1997 Abstract Abstract The capacity to learn syntactic rules is a hallmark of the human species, but whether this has been acquired by the process of natural The capacity syntactic rulesFurthermore, is a hallmark ofthe the human species, but whether has been acquired by the process of natural selection has been the subjecttooflearn controversy. cortical localization ofthis linguistic capacities has prompted some authors to selection has been the subject of controversy. Furthermore, the cortical localization of linguistic capacities has prompted some authors to suggest a modular representation of language in the brain. In this paper, we rather propose that the neural device involved in language is suggest a modular representation of language in the brain. In this paper, we rather propose that the neural device involved in language is embedded into aembedded large-scale network comprising connections between the temporal, and frontal into a neurocognitive large-scale neurocognitive network comprisingwidespread widespread connections between the temporal, parietal and parietal frontal Žespecially prefrontal . cortices. network is involved in the temporal organization of behavior andsequences, motor sequences, Žespecially . cortices. prefrontalThis This network is involved in the temporal organization of behavior and motor and in workingand in working . memory, a sort of short-term that participates immediate cognitive processing. In human a preconditionafor Žactive. memory,Žactive a sort of short-term memorymemory that participates in inimmediate cognitive processing. Inevolution, human evolution, precondition for language was the establishment of strong cortico–cortical interactions in the postrolandic cortex that enabled the development of language was the establishment of strong cortico–cortical interactions in the postrolandic cortex that enabled the development of multimodal associations. Wernicke’s area originated as a converging place in which such associations Žconcepts. acquired a phonological multimodal associations. Wernicke’s a converging placeintoininferoparietal which suchareas, associations conceptsto. the acquired correlate. We postulate thatarea theseoriginated phonologicalas representations projected which were Žconnected incipienta phonological Broca’s area, forming a working memory circuit for processing and learning complex vocalizations. a resultwere of selective pressureto the incipient correlate. We postulate thatthus these phonological representations projected into inferoparietal areas,As which connected Žprecursors forforming learning capacity and memory storage, this device yielded a sophisticated systemcomplex able to generate complicated As utterances Broca’s area, thus a working memory circuit for processing and learning vocalizations. a result of selective pressure of syntax. as it became increasingly connected with other brain regions, especially in the prefrontal cortex. This view argues for a gradual for learning capacity storage, this device yielded a sophisticated system able to generate complicated utterances Žprecursors origin and of thememory neural substrate for language as required by natural selection. q 1997 Elsevier Science B.V. . of syntax as it became increasingly connected with other brain regions, especially in the prefrontal cortex. This view argues for a gradual Keywords: Brain evolution; Broca’s area; lobe; Prefrontal cortex; Temporal Syntax; Wernicke’s Working memory origin of the neural substrate for language as Language; requiredParietal by natural selection. q 1997lobe; Elsevier Sciencearea; B.V. Keywords: Brain evolution; Broca’s area; Language; Parietal lobe; Prefrontal cortex; Temporal lobe; Syntax; Wernicke’s area; Working memory Contents 1. Introduction . ..................................................................... 382 71 Origen evolutivo del lenguaje (Aboitiz & García, 1997) ì El sustrato neuronal necesario para el lenguaje está incorporado a una red cogni7va de gran escala. ì Esta red conecta las cortezas de los lóbulos temporales, parietales y frontales (principalmente pre frontal). ì Estas cortezas son responsables de: ì La organización temporal de la conducta ì La organización de secuencias motoras ì La memoria de trabajo, necesaria para el procesamiento cogniJvo inmediato 72 Origen evolutivo del lenguaje (Aboitiz & García, 1997) ì Precursores evoluJvos del lenguaje: ì Establecimiento de relaciones corJco-­‐corJcales en la corteza pre-­‐ rolándica (LP) estableciendo asociaciones mulJmodales. ì Área de Wernicke: punto de convergencia en el que estas asociaciones (conceptos) adquirieron un correlato fonológico. ì Estas representaciones fonológicas se proyectaron por la corteza parietal inferior hacia la incipiente área de Broca. ì Se consJtuyó un circuito de memoria de trabajo para procesar y aprender vocalizaciones complejas. 73 Origen evolutivo del lenguaje (Aboitiz & García, 1997) ì Como resultado de las presiones selecJvas de mejorar las capacidades de aprendizaje y almacenamiento en la memoria: ì Este disposiJvo llevó a la formación de un sistema sofisJcado capaz de general expresiones complejas (precursoras de la sintaxis) al conectarse progresivamente con otras regiones cerebrales, sobre todo de la corteza pre frontal. ì Esta teoría arguye a favor del origen gradual del sustrato neuronal del lenguaje requerido por la selección natural. EPIG EN ESIS74 O F MENTAL RETARDATION AND DEVELOPMENTAL DISABILITIES RESEARCH REVIEWS 3: 282–292 (1997) 1* an EPIG EN ESIS O Helen F LAN GJ.UNeville AG E 1 Brain 1Development Laboratory, 2 Helen J. Neville * and D ebra L. Mills 1Brain 2Center Univ Development Laboratory, University of O regon, Eugene, O regon 2Center for R esearch in Language, University of for R esearch in Language, University of California at San Diego, La Jolla, California St udies employing event -relat ed brain pot ent ials (ERPs) and f unct ional magnet ic resonance imaging (f M RI) w ere designed t o st udy t he eff ect s of diff erent t ypes of language experience on t he development and organizat ion of neural syst ems import ant in language processing. Comparisons of cerebral organizat ion in normally hearing, monolingual English speakers w it h t hat observed in hearing and deaf lat e learners of English suggest t hat w hile syst ems import ant in lexical/semant ic processing are relat ively invulnerable t o delays in exposure t o a language, t he development of syst ems import ant in grammat ical processing, including t he specializat ion of t he lef t hemisphere, is aff ect ed by early language experience. St udies of individuals w ho acquired American Sign Language (ASL) as a nat ive language suggest t hat similar syst ems w it hin t he lef t hemisphere are employed in processing all nat ural languages independent ly of t he st ruct ure and modalit y of t he language acquired. These st udies also reveal t hat addit ional areas w it hin t he right hemisphere can be recruit ed int o t he language syst em w hen t he language depends on t he percept ion of spat ial locat ion and mot ion. St udies of children acquiring t heir f irst language reveal t hat t here is increasing diff erent iat ion of t he neural syst emsimport ant in processing t he meaning of w ords and of t he areas import ant in lexical and grammat ical processing and t hat t hese increasesin specializat ion are linked t o language abilit ies rat her t han t o chronological age per se. Furt her st udies suggest t hat development al language impairment can result from alterations in one of several different systems important in language, and that some indices of these functional neural systems may be predictive of language impairment. ! 1997 Wiley-Liss, Inc. Along similar lines, the comprehension and pr spoken language requires the participation and int numerous different processes, including the perceptio changing acoustic spectra,(ERPs) of phonemes, St udies employing event -relat ed brain pot ent ials andthe perc speaker’s intentions and of context, social und f unct ional magnet ic resonance imaging processes (f M RI)of wshared ereattention, designed t o of g the processing lexical, and prosodic information,on and motor st udy t he eff ect s of diff erent t ypes of language experience t he plannin few. It is reasonable to hypothesize, both on t development and organizat ion of neural syst(in ems import infrom visu parsimony keeping with the ant evidence ment) and the available evidence, that each of the language processing. Comparisons of cerebral organizat ion in norimportant in language use is mediated by different ne that develop rates and that these mally hearing, monolingual English speakers w it hat different t hat observed in systems degree to which and the time period during whi hearing and deaf lat e learners of English suggest hile syst emsinput. dependent ont hat and arew modified by language In the research here we have em import ant in lexical/semant ic processing are relat ively summarized invulnerable techniques to characterize the location and tim t o delays in exposure t o a language, t heoperation development of active syst during emslanguag of the neural systems in populations who differ in ion language import ant in grammat ical processing, including t he specializat of experi event-related potential (ER P) technique permits hig t he lef t hemisphere, is aff ect ed by early language ond) temporal resolutionexperience. monitoring of the electric generatedSign when Language people are presented with specific St udies of individuals w ho acquired American (ASL) cognitive demands. ER Ps are recorded from meta as a nat ive language suggest t hat similarplaced syst w it hinER tPshe lef t onems the scalp. Since are volume-condu MRDD Research Reviews1997;3:282–292. spatiallanguages resolution is variable but can b hemisphere are employed in processing allscalp, nattheural indecentimeter. Functional magnetic resonance imagi pendent of t he st ruct ure; and t hethelanguage permits monitoring ofacquired. changes in blood o Key Words:ly language; neural development plast icit modalit y; crit ical pe- y of associated with neuronal activity. The timecourse of he riod; bilingualism; ASL; language impairment t hat addit ional These st udies also reveal areas w it hin t he right ics limits the temporal resolution of fMR I (seconds the spatial resolution is thought to be around hemisphere can be recruit ed int o t he language syst em w hen t he a millim arsing a visual scene requires the participation and language depends on t he percept ion of spat ial locatof ion and mot ion. Neurobiology Language in Monolingual integration of numerous processes, including the percepand Bilingual Adults t hat t here is St udies irst language reveal tionofof children form, texture,acquiring spatial layout,t heir color, fmotion, Currently, rather little is known of the neur orientation, and depth. Extensive research at many levels of increasing diff erent iat ion of t he neural systmany emsimport ant in processof the processes important in language. In ou analysis from psychological to synaptic has shown that these studied the development of the neural ing t heprocesses meaning of w ords and that of develop t he areas import ant in lexical andsystems im different rely on different neural systems at lexical semantic and grammatical processing. different rates and that these systems, while strongly biased to grammat ical processing and t hat t hese increasesin specializat ion are right-handed, monolingual adults, nouns and verbs (‘ develop in a particular fashion, differ markedly in the degree to that provide semantic linked t othelanguage abilit iestheir ratdevelopment her t hanis t owords) chronological age information per se. elicit which and time periods during which different pattern of brain activity (as measured by ER dependent on and modifiable by input from the environment Furt her st udies suggest t hat developmentfunction al language impairment words, including prepositions and conjunctio [Harwerth et al., 1986; Garraghty, 1993; Maurer, 1993; Neville, class’’ words) that provide grammatical information can result alterations in one ofabout several 1995; Nevillefrom and Bavelier, in press]. Little is known the different systems important P that give rise to these striking differences in in mechanisms language, and that some indices of these functional neural systems developmental specificity and plasticity, but ongoing research Grant sponsor: National Institutes of Health; Grant numbers: DC00481, DC021289; Grant sponsor: The Wiley-Liss, McDonnell-Pew Foundations. Inc. may be they predictive language impairment. suggests may be due of to several factors, including differences ! 1997 in ratesResearch of maturation and in degree of redundant connectivity MRDD Reviews1997;3:282–292. early in development. *Correspondence to: Helen J. Neville, Brain Development Lab, 1227 O regon, Eugene, O regon 97403-1227. E-mail: [email protected] ! 1997 Wiley-Liss, Inc. Key Words: language; neural development ; plast icit y; crit ical period; bilingualism; ASL; language impairment Fig.Fig. 3. 3.CortCort icalical areas show inging increases ininblood normal hearing hearingadult adults sread readEnglish Englishsent sent ences (t op), w hen areas show increases bloodoxygenat oxygenation ion on on ffM MRI RI w hen normal ences (t op), w hen congenit allyally deaf natnat iveive signers read English allydeaf deafnat native ivesigners signers viewsent sent ences t heir nat ive congenit deaf signers read Englishsent sentences ences(middle) (middle)and and w when hen congenit congenit ally view ences in in t heir nat ive arsing a visual signsign language (American Sign Language). language (American Sign Language). P scene requires the participation and integration of numerous processes, including the perception of form, texture, spatial layout, color, motion, This paper was presented at a colloquium entitled ‘‘Neuroimaging of Human Brain Function,’’ organized by Michael Posner and Marcus E. Raichle, held May 29–31, 1997, sponsored by the National Academy of Sciences at the Arnold and Mabel Beckman Center in Irvine, CA. Cerebral organization for language in deaf and hearing subjects: Biological constraints and effects of experience 924 HELEN J. NEVILLE*†, DAPHNE BAVELIER‡, DAVID CORINA§, JOSEF RAUSCHECKER‡, AVI KARNI¶, A NIL L ALWANI!**, AColloquium LLEN BRAUN!, VINCE CLARK!, PETER JEZZARD!, AND ROBERT TURNER†† Colloquium Paper: Neville et al. Paper: Neville et al. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95 (1998) *University of Oregon, Eugene, OR 97403-1227; ‡Georgetown University Medical Center, Washington, DC 20007; §University of Washington, Seattle, WA 98195; ¶Weizmann Institute of Science, Rehovot, 76100 Israel; !National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD 20892; ††Institute of Neurology, Queen Square, London WC1N3BG, United Kingdom; and **University of California, San Francisco, CA 94143 ABSTRACT Cerebral organization during sentence processing in English and in American Sign Language (ASL) was characterized by employing functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) at 4 T. Effects of deafness, age of language acquisition, and bilingualism were assessed by comparing results from (i) normally hearing, monolingual, native speakers of English, (ii) congenitally, genetically deaf, native signers of ASL who learned English late and through the visual modality, and (iii) normally hearing bilinguals who were native signers of ASL and speakers of English. All groups, hearing and deaf, processing their native language, English or ASL, displayed strong and repeated activation within classical language areas of the left hemisphere. Deaf subjects reading English did not display activation in these regions. These results suggest that the early acquisition of a natural language is important in the expression of the strong bias for these areas to mediate language, independently of the form of the language. In addition, native signers, hearing and deaf, displayed extensive activation of homologous areas within the right hemisphere, indicating that the specific processing requirements of the language also in part determine the organization of the language systems of the brain. The development and accessibility of neuroimaging techniques continue to permit detailed characterization of the neural systems active during perception and cognition in the intact human brain. Research along these lines reveals the adult human brain as a highly differentiated amalgam of systems and subsystems, each specialized to process specific and different kinds of information. A central issue is how these highly specialized systems arise in human development, the degree to which they are biologically constrained, and the extent to which they depend on and can be modified by input from the environment. Extensive research at many levels of analysis has documented that, within the domain of sensory processing, strong biases constrain development, but many aspects of sensory organization can adapt and reorganize after both proficiency in the language, whether an individual learned more than one language, and the degree of similarity between the languages learned (16–21). Behavioral studies suggest that early exposure to language is necessary for complete linguistic proficiency, and several different types of evidence raise the hypothesis that early exposure to a language may be necessary for the hallmark specialization of the left hemisphere for language (19, 22–24). Little is known about which aspect(s) of early language experience may be important in this development. It has been proposed that the demands of processing rapidly changing acoustic spectra is a key factor whereas other evidence suggests that the grammatical recoding of information may be central in the differentiation of the left hemisphere for language (25–27). The effects of language structure and modality on neural development can provide evidence on these proposals. Comparison of cerebral organization in native speakers who are and are not also native users of American Sign Language (ASL) and of native signers who are and are not also native users of English permits a unique perspective on these issues. Studies of the effects of brain damage in early learners of ASL suggest that sound-based processing of language may not be necessary for the specialization of the left hemisphere (28–30). Electrophysiological and lesion-based evidence provide limited and apparently contradictory evidence on the proposal that the right hemisphere may play a role in processing ASL (28–32). Different lines of evidence suggest that areas within the right hemisphere may be included in the language system when the perception and!or production of the language depend on spatial contrasts. Additionally, several studies suggest that bilingualism is associated with a different cerebral organization than monolingualism, but there is very little evidence on the effects of sign!spoken bilingualism on the development of the language systems of the brain. To address these issues we employed fMRI to compare cerebral organization in three groups of individuals with 75 Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA Vol. 95, pp. 922–929, February 1998 Colloquium Paper This paperProc. was a colloquiu Natl.presented Acad. Sci. USA at 95 (1998) 925 Posner and Marcus E. Raichle, held Ma and Mabel Beckman Center in Irvine, C Cerebral organization Biological constraints HELEN J. NEVILLE*†, DAPHNE BAVELI A LLEN BRAUN!, VINCE CLARK!, PETER *University of Oregon, Eugene, OR 97403-1227; ‡Ge ¶Weizmann Institute of Science, Rehovot, 76100 Israe WC1N3BG, United Kingdom; and **University of C ABSTRACT Cerebral organization du cessing in English and in American Sign L characterized by employing functional m imaging (fMRI) at 4 T. Effects of deafne acquisition, and bilingualism were asses results from (i) normally hearing, monolin ers of English, (ii) congenitally, genetically of ASL who learned English late and t modality, and (iii) normally hearing bi native signers of ASL and speakers of E hearing and deaf, processing their native la ASL, displayed strong and repeated activat language areas of the left hemisphere. De English did not display activation in th results suggest that the early acquisition of is important in the expression of the str areas to mediate language, independently language. In addition, native signers, hea played extensive activation of homologou right hemisphere, indicating that the s requirements of the language also in p organization of the language systems of t The development and accessibility of neuro continue to permit detailed characteriza systems active during perception and cog human brain. Research along these line 76 77 Lenguaje Atención espacial Reconocimiento de objetos y de caras Funciones ejecuJvas Memoria y emociones Fig. 3. Large-­‐scale networks for cogni`on and behaviour (Mesulam, 2000). (A) A ler hemisphere-­‐dominant language network with epicentres in Wernickeʼs and Brocaʼs areas (Catani and Mesulam, 2008). (B) A face-­‐object idenJficaJon network with epicentres in occipito-­‐temporal and temporopolar cortex (Fow et al., 2008). (C) An execuJve funcJon-­‐comportment network with epicentres in lateral prefrontal cortex, orbitofrontal cortex, and posterior parietal cortex (Zappala' et al., 2012). (D) A right hemisphere-­‐dominant spaJal awenJon network with epicentres in dorsal posterior parietal cortex, the frontal eye fields, and the cingulate gyrus (Doricchi et al., 2008). (E) A memory-­‐emoJon network with epicentres in the hippocampal-­‐entorhinal regions and the amygdaloid complex (Park et al., 2010). 78 Funciones ejecutivas ì 79 Definición de Muriel Lezak (2004) ì Las FE, son las conductas más complejas, su función esencial es responder de manera adaptaJva a situaciones nuevas; son también la base de muchas habilidades cognosciJvas, emocionales y sociales. 80 Componentes de las FE según Lezak ì Volición (conceptualización de necesidades y deseos, visualización de la manera de saJsfacerlos: conducta intencional) ì Planeación (IdenJficación y organización de los pasos y elementos necesarios para alcanzar las metas) ì Acción proposiJva (el paso de la intención y el plan a la realización: iniciación, detención, flexibilidad, cambio, etc i.e. la autorregulación) ì Ejecución efecJva (Monitoreo, autocorrección, regulación de la intensidad, el tempo, etc.) Iniciación y pulsión Inhibición de respuestas Mantenimiento Conciencia Pensamiento generativo Organización Modelo clínico de las FE (Sohlberg y Mateer, 2001) Procesos de atención MT Mem prospectiva Conciencia Procesos de memoria Interdependencia de los procesos de memoria,de atención y de las FE (Sohlberg y Mateer, 2001) Funciones Ejecutivas Atención selectiva Atención dividida Alternancia de la atención Persistencia de la tarea 83 Redes ejecutivas de la corteza prefrontal ì Como la corteza posterior, las áreas frontales también están organizadas jerárquicamente y en gradientes filogenéJco, ontogenéJco y conecJvo. ì En el nivel más bajo la corteza motora primaria; sobre ella la corteza premotora (6a 6b), incluyendo el área motora suplementaria y sobre éstas las áreas laterales de la corteza prefrontal 84 REDES EJECUTIVAS EN LA CORTEZA PREFRONTAL ì Pero, a diferencia de la corteza posterior; el flujo conecJvo parte de las áreas de asociación (el más alto nivel) hacia la corteza premotora y motora primaria. ì Se requiere además conexiones de retroalimentación recíproca entre los niveles sucesivos de integración. ì La retroalimentación es esencial en la formación de redes cogniJvas ejecuJvas. 85 REDES EJECUTIVAS EN LA CORTEZA PREFRONTAL ì La formación de los cognits ejecuJvos en la corteza frontal requiere la co-­‐ocurrencia asociaJva de inputs de los efectores del movimiento. ì Algunos de estos inputs provienen del tálamo, otros de los propioceptores de los músculos y arJculaciones. ì Otros inputs provienen del propio sistema motor en lo que se ha llamado copias eferentes o descargas corolarias. Organización jerárquica y heterárquica de las redes corJcales Sistema 1 Sistema 2 Sistema 3 Nivel III Nivel III Nivel III Nivel II Nivel II Nivel II Nivel I Nivel I Nivel I 86 87 Dominios de la acción frontal ì En cada dominio de la acción, los aspectos más específicos y concretos se representan en los niveles más bajos de la jerarquía frontal. ì El área 4 representa los movimientos musculares elementales. Se puede decir que las neuronas de esta área conservan la memoria motora de la especie (memoria filéJca) 88 DOMINIOS DE LA ACCIÓN FRONTAL ì En términos generales: los aspectos más complejos y globales de la acción conductual están representados en las áreas anterior y lateral del lóbulo frontal. ì LC: Ausencia o dificultad para llevar a cabo programas que se exJenden en el Jempo ì EEG: patrones de acJvidad neuronal en tareas conductuales que implican el span temporal ì Ac`v metabólica: incrementa en tareas de planeación conceptual de actos motores complejos. 89 DOMINIOS DE LA ACCIÓN FRONTAL ì Lo que parece que se representa en el LF son variantes relaJvamente nuevas de estructuras de acción en cualquier dominio. ì Lo que determina la novedad es la necesidad de adaptarse a los cambios ambientales, por ejemplo nuevas conJngencias de reforzamiento aunque los elementos de las respuestas sean los mismos (creaJvidad) ì Una estructura de acción es una gestalt temporal 90 DOMINIOS DE LA ACCIÓN FRONTAL ì Una estructura de acción es una gestalt temporal ì Está sujeta a reglas, como la ley de la proximidad; además también la meta. ì La representación central de una gestalt de acción es equivalente a lo que otros autores han llamado un esquema (Piaget): plan o programa de acción. No se representan todos los elementos o pasos. ì Es una representación abstracta, resumida. 91 DOMINIOS DE LA ACCIÓN FRONTAL: Emociones CORTEZA ORBITAL CORTEZA ORBITAL AMÍGDALA HIPOTÁLAMO SIST MONOAMINÉRGICO Inputs viscerales, pulsiones básicas, estado general del organismo, Significado moJvacional de los esdmulos 92 FUNCIONES EJECUTIVAS Atención ejecuJva Planeación Set preparatorio Set Memoria de trabajo Memoria prospecJva Control de interferencias Toma de decisiones 93