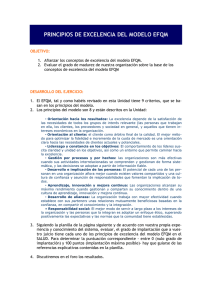

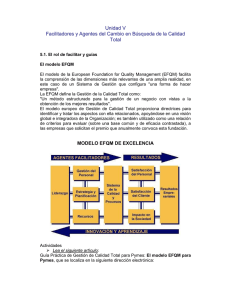

Performance appraisal and compensation in EFQM recognised

Anuncio