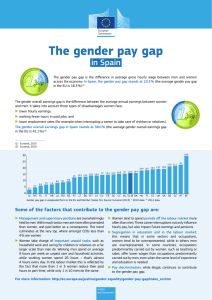

Women, Men and Working Conditions in Europe

Anuncio