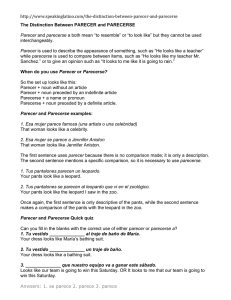

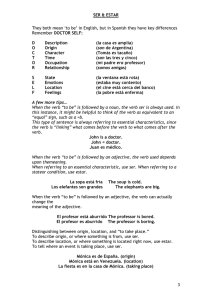

Constructions with the raising verb parecer in Spanish

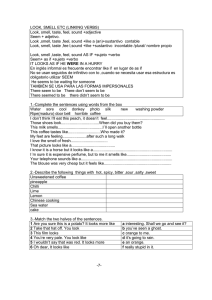

Anuncio