- Ninguna Categoria

Exchange Rate Regimes: Balance of Payments & Foreign Exchange Market

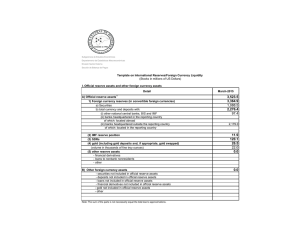

38 Exchange Rate Regimes (a) Exchange rate (b) Foreign currency price 2.20 17 15 1.80 13 11 1.40 9 1.00 7 0.60 5 1 9 17 25 33 41 49 57 65 73 81 89 97 1 9 17 25 33 41 49 57 65 73 81 89 97 (c) Quantity (d) Domestic currency revenue 90 900 850 800 80 750 700 70 650 60 1 9 17 25 33 41 49 57 65 73 81 89 97 600 1 9 17 25 33 41 49 57 65 73 81 89 97 Figure 2.8 The effect of changes in the exchange rate on domestic currency revenue (100 simulations) exchange rate, the foreign currency price, the quantity sold and the domestic currency revenue. Obviously, volatility in the domestic currency revenue is associated with exchange rate volatility. The balance of payments and the exchange rate One of the arguments for flexible exchange rates and against fixed rates pertains to the balance of payments adjustment mechanism under the two regimes. Therefore, it is worthwhile examining in detail the relationship between the balance of payments and the exchange rate. This relationship arises because the transactions involving trade and capital flows, which are recorded on the balance of payments, give rise to demand for and supply of currencies. Transactions in the market for goods and services, such as imports and exports, give rise to demand for and supply of foreign exchange respectively. Equivalently, these transactions lead to the supply of and demand for the domestic currency respectively. The Role of the Exchange Rate in the Economy 39 Transactions in financial markets, which are recorded on the capital account, also lead to demand for and supply of currencies. The sale of domestic securities and the purchase of foreign securities give rise to demand for foreign exchange (supply of domestic currency). Conversely, the purchase of domestic securities and the sale of foreign securities give rise to demand for the domestic currency (supply of foreign exchange). The relationship between the balance of payments and the foreign exchange market is, therefore, obvious. For each transaction on the foreign exchange market there is a corresponding entry on the balance of payments. For the purpose of illustrating this relationship further we will examine the foreign exchange market from the perspective of the foreign currency, such that the exchange rate, E, is measured as the domestic currency price of one unit of the foreign currency. Three possible cases are illustrated in Figure 2.9, which shows the demand for and supply of foreign exchange curves (D and S respectively). In Figure 2.9(a), the foreign exchange market is in equilibrium at the exchange rate E0, at which the supply of and demand for foreign exchange are equal. This is equivalent to saying that the balance of payments is in equilibrium. In Figure 2.9(b), there is excess demand for foreign exchange at the exchange rate E1, which is below the equilibrium exchange rate. This excess demand is equivalent to a deficit on the balance of payments. Finally, Figure 2.9(c) shows the case when there is excess supply of foreign exchange, which is equivalent to a surplus on the balance of payments. This occurs at the exchange rate E2. Let us for simplicity concentrate on the current account of the balance of payments by assuming that exports and imports are the sources of, supply of and demand for foreign exchange. Given this simplifying assumption about its structure, the relationship between the balance of payments and the foreign exchange market can be restated by examining the demand for and supply of imports and exports as represented in Figure 2.10. Since we are still examining the relationship from the * perspective of the foreign currency, the prices of imports and exports, Pm * and Px respectively, are expressed in foreign currency terms. Figure 2.10(a) shows the supply and demand curves for imports, Sm and Dm, both of which are drawn as linear functions relating the quantity of imports, Qm, to the foreign currency price of imports. The area of the rectangle defined by the axes and the point of intersection of the supply and demand curves represents the amount of foreign exchange spent on imports (that is, import expenditure). Recalling that the demand for imports leads to demand for foreign exchange, import expenditure should be equivalent to the demand for foreign exchange. Likewise, 40 (a) Balance of payments equilibrium E S E0 D Q (b) Balance of payments deficit E S E1 Excess demand D Q (c) Balance of payments surplus E S E2 Excess supply D Q Figure 2.9 The relationship between the balance of payments and the exchange rate The Role of the Exchange Rate in the Economy 41 Px∗ Pm∗ Sx Sm Dx Dm Qm (a) Import expenditure = demand for foreign exchange Qx (b) Export revenue = supply of foreign exchange Figure 2.10 Import expenditure and export revenue the rectangle in Figure 2.10(b) defines export revenue and hence the supply of foreign exchange. Bearing these points in mind, we can proceed to derive the demand for and supply of foreign exchange curves by considering what happens to import expenditure and export revenue as the exchange rate changes. Consider the demand side first. It is important to remember that imports are foreign goods consumed in the home country. Domestic consumers base their decision concerning the amount of imports they choose to consume on the domestic currency price of imports. For simplicity we assume that this price can be obtained by converting the foreign currency price at the current exchange rate, by using the equation Pm ¼ EPm ð2:8Þ * where Pm and Pm are the domestic currency and foreign currency prices of imports respectively. Let us now specify the demand for imports as a function of the domestic currency price. The import demand function may be written as Qm ¼ 0 1 P m ð2:9Þ where 0 and 1 are positive constant parameters and Qm is the quantity of imports demanded. By substituting equation (2.8) into equation (2.9), we obtain Qm ¼ 0 1 EPm ð2:10Þ 42 Exchange Rate Regimes Hence, the demand for foreign exchange function can be written as 2 1 EPm Qf ¼ 0 P m ð2:11Þ which gives @Qf 2 ¼ 1 Pm @E ð2:12Þ The effect of the exchange rate on the demand for foreign exchange is unambiguous because the rise in E reduces the quantity of imports demanded, Qm, without affecting the foreign currency price of imports, * * . Therefore, the product Pm Qm , which measures import expenditure Pm (and hence the demand for foreign exchange), must decline. Consider now the supply side, starting with the relationship Px ¼ Px E ð2:13Þ where Px and Px* are the domestic currency price and foreign currency price of exports respectively. Since exports are domestic goods that are consumed abroad, the demand for exports is specified as a function of the foreign currency price. Hence, the export demand function takes the form Qx ¼ 0 1 Px ð2:14Þ where 0 and 1 are positive constant parameters and Qx is the quantity of exports demanded. From equations (2.13) and (2.14), we can see that a rise in E reduces the foreign currency price, leading to an increase in the quantity of exports demanded. Because the price and quantity move in opposite directions, the net effect on export revenue, and hence on the supply of foreign exchange, is ambiguous. It could rise, fall or stay at the same level. The supply of foreign exchange function is then Qf ¼ 0 Px 1 Px2 ð2:15Þ By combining (2.15) and (2.13) we obtain Qf ¼ 0 Px 1 Px2 2 E E ð2:16Þ Hence, the slope of the supply curve is @Qf 0 Px 21 Px2 ¼ 2 þ @E E E3 ð2:17Þ The Role of the Exchange Rate in the Economy 43 which may be positive or negative, depending on the level of the exchange rate (positive at low exchange rates and vice versa). In fact the supply curve will be backward-bending, having a positive slope at low exchange rates. Figure 2.11 shows the downward-sloping demand curve and the backward-bending supply curve. Because the supply curve is backwardbending, the equilibrium exchange rate may not be unique. In Figure 2.11, it is shown that there are three equilibrium values for the exchange rate: E1, E2 and E3. Multiple equilibria create several problems, the first of which is that some equilibrium exchange rate values are unstable. It is typically the case that each unstable equilibrium is bounded by two stable equilibria. When the exchange rate is above E2, it tends to move to E3, and when it is below E2 it tends to move to E1. The second problem is that the equilibrium values of the exchange rate are ranked differently by the two countries involved in the bilateral exchange rates. For example, one country may prefer E1 while the other prefers E3. A situation like this could lead to conflict in the economic policies of the two countries. The third problem is that speculation as well as balance of payments disturbances may cause sharp fluctuations in the exchange rate, which lead to an unnecessary and wasteful reallocation of resources. For E S E3 E2 E1 D Q Figure 2.11 Multiple equilibria in the foreign exchange market 44 Exchange Rate Regimes example, if the exchange rate rises slightly above E1, speculators will start buying the foreign currency, thinking that it will rise further. The exchange rate will rise beyond the unstable level E2, all the way to the stable level E3. When it reaches E3, speculators sell the foreign currency, causing the exchange rate to fall all the way to E1. The effect of a balance of payments disturbance is illustrated in Figure 2.12. A fall in the demand for foreign exchange is represented by a shift in the demand curve, and the equilibrium exchange rate falls from E1 to E2. This big drop is caused by the backward-bending nature of the supply curve. Changes in the exchange rate would be less dramatic under a normal upward-sloping supply curve. The effect of the exchange rate on the current account of the balance of payments emanates from the effect of changes in the exchange rate on prices and, therefore, the demand for domestic and foreign goods (exports and imports). When the exchange rate rises (the domestic currency depreciates), prices of exports in foreign currency terms fall while prices of imports in domestic currency terms rise. If the elasticities of the demand for exports and imports are sufficiently high, then the demand for imports falls and the demand for exports rises, leading to improvement in the current account. This chain of reasoning is the basis of using devaluation to correct a balance of payments deficit. E S E1 E2 D Q Figure 2.12 The effect of a balance of payments disturbance when the supply curve is backward-bending The Role of the Exchange Rate in the Economy 45 Figure 2.13 illustrates the effect of devaluation of the domestic currency (a higher exchange rate) on the current account. In Figures 2.13(a) and 2.13(b), devaluation is ineffective because the elasticities of demand for imports and exports are low. In this case, devaluation results in a small reduction in import expenditure, as shown by Figure 2.13(a), and a fall, rather than a rise, in export revenue, as shown by Figure 2.13(b). The latter occurs because devaluation in this case reduces the foreign currency price of exports by more than the increase in the quantity of exports demanded. Hence, devaluation may lead to deterioration rather (a) Inelastic demand for imports ∗ Pm (b) Inelastic demand for exports ∗ Pm Sx Sm Dm Dx Qx Qm (c) Elastic demand for imports ∗ Pm (d) Elastic demand for exports ∗ Pm Sx Sm Dm Dx Qm Figure 2.13 The effect of devaluation when elasticities are high and low Qx 46 Exchange Rate Regimes than improvement in the current account. In Figure 2.13(c) and 2.13(d), on the other hand, demand is elastic. Hence, devaluation causes a significant reduction in import expenditure and a rise, not a fall, in export revenue. The result is improvement in the current account. This type of analysis is referred to as the elasticities approach to the balance of payments. The core of this approach is the Marshall–Lerner condition, which tells us that devaluation will have a favourable effect on the current account if the sum of the absolute values of the elasticities of demand for exports and imports is greater than unity. This approach has an important implication for the dynamic response of the current account to devaluation (or depreciation). The response is different in the short run (the period immediately following devaluation) than it would be in the long run (the period further out in the future). This is because the elasticity of demand is lower in the short run than in the long run. If the Marshall–Lerner condition is satisfied in the short run but not in the long run, there is a possibility that the current account may deteriorate even further in the short run before recovering in the long run. This behaviour is described in Figure 2.14. At time t1, the current account is in deficit, and a decision is taken to correct it by devaluation. In the period immediately following devaluation, the current account deteriorates, registering an even greater deficit. With the passage of time, elasticities increase and once the Marshall–Lerner condition is satisfied, the current account starts to improve. At t2, the + t1 t2 – Figure 2.14 The J-curve effect t3 Time The Role of the Exchange Rate in the Economy 47 deficit reaches its highest value, and from then onwards it starts to shrink. At t3, the deficit is eliminated, and this is followed by the achievement of a surplus. The time path of the current account position resembles the letter J, and this is why this process is called the ‘J-curve effect’. Another approach is the absorption approach associated with Alexander (1952). The starting point is the national income identity, which can be written as Y ¼ C þ I þ G þ ðX M Þ ð2:18Þ where Y is national output or income, C is consumption, I is investment (capital formation), G is government expenditure, X is exports and M is imports. Equation (2.18) can be written as XM ¼Y A ð2:19Þ where absorption, A, is given by A¼CþIþG ð2:20Þ Thus, if Y > A, the current account is in surplus, whereas if Y < A, it is in deficit. The absorption approach can be illustrated as follows. First, define consumption as the difference between income and saving, which gives C¼Y S ð2:21Þ where S is saving. By ignoring G and substituting equation (2.21) into equation (2.20) we obtain Y A¼SI ð2:22Þ Hence, the equilibrium condition may be written as SI ¼XM ð2:23Þ The difference between the elasticities and the absorption approaches is that while the former focuses on the X–M schedule (which makes it a partial approach), the latter combines this schedule with the S–I schedule to obtain an equilibrium condition. Figure 2.15 shows that the S–I schedule is upward-sloping because saving, S, is an increasing function of income, Y, whereas I can be assumed to be independent of Y. Thus, as Y rises, S–I rises. This schedule shows the excess of domestic saving over domestic investment (or otherwise) at any level of income. The X–M schedule, which shows the 48 Exchange Rate Regimes + S –I Y0 Y1 Y X–M – Figure 2.15 The absorption approach to the balance of payments current account position for each level of income, slopes downwards because M is an increasing function of Y while X is independent of it. Initially, the current account is in deficit at Y0. If the Marshall–Lerner condition is satisfied, devaluation (or depreciation) leads to a shift in the X–M schedule. If the level of income is unchanged at Y0, as implicitly assumed by the elasticities approach, the current account registers a surplus. However, an increase in net exports is bound to have an expansionary effect on the economy, leading to a rise in the level of income to Y1, at which the current account is still in deficit, albeit smaller than before. The explanation of this result is simple: the rise in income leads to a rise in imports, reducing the extent of the rise in net exports resulting from devaluation. Thus, the satisfaction of the Marshall– Lerner condition is not sufficient for devaluation to have a favourable effect on the current account. While the elasticities approach is based exclusively on the price adjustment mechanism, the absorption approach takes into account the income adjustment mechanism as well. Central bank intervention in the foreign exchange market The issue of central bank intervention in the foreign exchange market is crucial and highly relevant for the issue of exchange rate regime choice. Under a fixed exchange rate regime, the central bank maintains

Documentos relacionados

Añadir este documento a la recogida (s)

Puede agregar este documento a su colección de estudio (s)

Iniciar sesión Disponible sólo para usuarios autorizadosAñadir a este documento guardado

Puede agregar este documento a su lista guardada

Iniciar sesión Disponible sólo para usuarios autorizados