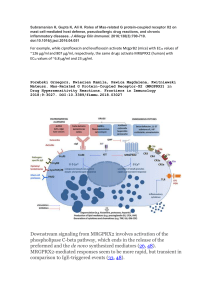

Personality and Individual Di erences 232 (2025) 112848 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Personality and Individual Differences journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/paid The role of parental overcontrol in psychological distress of vulnerable narcissists: The burden of shame Simon Ghinassi a , Giulia Fioravanti b, Silvia Casale b,* a b Department of Experimental and Clinical Medicine, University of Florence, Largo Brambilla, 3, 50134 Florence, Italy Department of Health Sciences, Psychology Unit, University of Florence, Via San Salvi, 12, Pad. 26, 50135 Florence, Italy A R T I C L E I N F O A B S T R A C T Keywords: Anxiety Depression Parental overcontrol Shame Stress Vulnerable narcissism Psychological distress can have a wide range of negative consequences, and the central role played by parental overcontrol in its occurrence has been widely demonstrated. It is also well-established that narcissistic vulner­ ability results from parental overcontrol and is characterized by intense shame experiences, which, in turn, fa­ vors psychological distress. However, no studies have examined these variables simultaneously, integrating them in a theoretical-based model. Therefore, this study aims to build on previous evidence by exploring whether parental overcontrol can lead to the onset of depression, anxiety and stress through the serial mediating role of narcissistic vulnerability and shame proneness. A convenience sample of 643 participants (68%F; Mage = 29.87 ± 13.00) was recruited. The assessed structural model produced adequate fit to the data. Results showed the significant role played by maternal – but not paternal – overcontrol in the onset of vulnerable narcissistic traits and that shame proneness, particularly bodily shame, fosters the three facets of psychological distress in such individuals. Clinicians dealing with individuals with high vulnerable traits could help them reduce their distress by working on the level of narratives relating to experiences of maternal overcontrol perceived during childhood and feelings of shame expressed, especially when connected to one’s own body. 1. Introduction in various theoretical perspectives (Baumrind, 1971; Parker et al., 1979). PO has been defined as a pattern of behaviors involving high parental vigilance, excessive regulation of child routines, an intrusion into the child’s decision-making process, and a general inhibition of the child’s motivation to solve problems independently to the point of limiting or threatening the child’s autonomy and independence (Parker et al., 1997). Numerous empirical evidence has shown that PO is a parenting style closely related to a wide range of negative outcomes including psychological distress (Miller et al., 2018; Sun et al., 2023). For example, longitudinal evidence shows that children with at least one overcontrolling parent were more likely to report symptoms of persis­ tent anxiety during the transition to early adolescence (Borelli et al., 2015), and numerous studies have highlighted that those who have experienced PO are more likely to report depressive symptoms (e.g., Shute et al., 2019). The relationship between PO and psychological distress can be un­ derstood in the light of the Self-Determination Theory (Ryan & Deci, 2017) since the intrusiveness and dominance – typical of PO – can lead to frustration or dissatisfaction of the child’s basic psychological needs for autonomy, competence, and relatedness (Casale et al., 2023; Van Psychological distress (i.e., anxiety, depression, and stress) consti­ tutes a high-incidence mental health problem and represents a serious public health issue. A meta-analysis conducted by Moreno-Agostino et al. (2021) showed that there is an increasing trend in the prevalence of experiencing depression over time. Similarly, there has been an overall growth in anxiety among adults, which rose from 5.12 % in 2008 to 6.68 % in 2018 (Goodwin et al., 2020). This trend is upsetting as psychological distress is associated with a series of negative conse­ quences, up to an increase in mortality from several major causes (Barry et al., 2020). Considering the impact of psychological distress on the well-being of both individuals and society, it is not surprising that the literature has focused on the study of possible risk factors of its onset. Among these, environmental factors, including parental behaviors, turn out to play a key role as the quality of the parent-child bond during childhood results to be a factor of central importance for the development (Bowlby, 1969; Hudson & Rapee, 2005). In particular, Parental Overcontrol (PO) is consistently discussed as an important dimension of parenting behavior * Corresponding author. E-mail addresses: [email protected] (G. Fioravanti), [email protected] (S. Casale). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2024.112848 Received 29 March 2024; Received in revised form 16 July 2024; Accepted 16 August 2024 Available online 27 August 2024 0191-8869/© 2024 Elsevier Ltd. All rights are reserved, including those for text and data mining, AI training, and similar technologies. S. Ghinassi et al. Personality and Individual Di erences 232 (2025) 112848 Petegem et al., 2020). Specifically, overcontrolling parents may convey to children the message that the world is not safe and they are not able to cope autonomously with the difficulties that will arise (Becker et al., 2010; Miller et al., 2018). Taken as a whole, these beliefs contribute to the possibility that a vicious circle is triggered in which the avoidance of certain situations strengthens the negative perception that an individual has of his/her competence and autonomy, which at first contributed to the onset of such avoidant behavior. From a psychodynamic perspective, it has been theorized that one of the important factors involved in the development of the narcissistic personality structure is the lack of “optimal frustration” experiences (Kohut, 1971). Such “optimal frustrations” are defined as specific, iso­ lated, and non-traumatic cases in which the child is left without guid­ ance from the parents, and he/she is forced to face challenges independently of them. Therefore, the inappropriate and intrusive involvement of overcontrolling parents does not allow children to experience such “optimal frustrations” as they do not experience what is called a “good enough” mother (Winnicott, 1945), i.e. a mother who allows to feel and experience the effects of such frustrations, which are a prerequisite for normal child development. This might lead the children to develop compensatory defensive behaviors (e.g., grandiose traits) but also to depend on external sources for their sense of identity and value, that is to develop traits of narcissistic vulnerability (Horton, 2011). Indeed, individuals with vulnerable traits are marked by fragile selfimage, hypersensitivity towards the opinions of others, an intense desire for approval and defensiveness (Dickinson & Pincus, 2003; Miller et al., 2011). For these reasons, many scholars have explored the link between vulnerable narcissism and psychological distress in both the general (e.g., Casale, 2022) and clinical (Kealy et al., 2023) population. In line with the psychodynamic perspective of the genesis of narcissistic vulnerability (Kohut, 1971), there is a growing empirical consensus that shame is a cornerstone feature to consider in this sce­ nario. Shame is an intense and negative affect that implies the percep­ tion of possessing personal attributes or engaging in behaviors that others will find unattractive, with the consequent desire to hide or disappear for the humiliation experienced (Gilbert, 2000). Indeed, shame is seen as a common experience among individuals with vulnerable traits so much that they have been described as “shameridden” considering their extreme sensitivity to the opinions of others (Ronningstam, 2009). This hypothesized association between vulner­ able narcissism and shame has also been supported by numerous empirical evidence (Boursier & Gioia, 2020; Casale, 2022; Ghinassi et al., 2023; Kealy et al., 2023). Moreover, the experience of shame is also implicated in various forms of psychological distress. For example, a meta-analysis revealed that shame showed a strong and significant as­ sociation with depressive symptoms (Kim et al., 2011). In the same vein, in their meta-analytic work, Cândea and Szentagotai-Tătar (2018) found that shame was significantly and positively associated with anxiety symptoms with an overall medium effect size. Overall, there is empirical evidence about the negative impacts of PO in terms of psychological distress, vulnerable narcissism, and shame proneness. Likewise, there is also evidence to suggest that having perceived one’s own parents as excessively controlling may have fostered the structuring of a narcissistic vulnerability, in which shame is a cornerstone feature. However, to the best of our knowledge, no study has so far conceptually linked such evidence together, exploring a possible pathway that links the experience of PO and psychological distress through the onset of narcissistic vulnerability and the resulting experiences of shame. Indeed, only one study has verified a path from childhood adversity to psychological distress through the mediating role of vulnerable narcissism and shame (Kealy et al., 2023). However, this study focused on the effect of parental emotional neglect in childhood, and less is known about the effect of other maladaptive parenting styles (i.e., parental overcontrol), which have been theoretically considered as key precursors of narcissistic vulnerability (Horton, 2011). Second, this study focused on the effect of the overall perception of parental Table 1 Sociodemographic characteristics of the sample. Gender Women Men Birthplace Italy Abroad Sentimental status Unmarried Married Legally separated Divorced Widowed Highest educational level Middle school High school University or postgraduate degree Employment Student Working student Housewife/househusband Employed Unemployed Retired n % 437 206 68 32 639 4 99.40 0.60 511 106 11 13 2 79.50 16.50 1.70 2.00 0.30 25 312 306 3.90 48.50 47.50 271 88 6 239 24 15 42.10 13.70 0.90 37.20 3.70 2.30 Note. N = 643. emotional neglect, and previous studies (e.g., Casale et al., 2023) highlight that the “source” of overprotection (i.e., the mother’s or the father’s) needs to be taken into account. Finally, that study did not distinguish between different shame experiences. Yet, some studies have shown that narcissistic vulnerability is related to behavioral, charac­ terological, and bodily shame, but the former does not explain the pathway to negative outcomes (Ghinassi et al., 2023; Jaksic et al., 2017). 1.1. The current study The above-described previous findings encourage us to propose and test an overarching model that brings together these variables, as such an effort might be of help in clarifying the pathways towards psycho­ logical distress among individuals with vulnerable narcissistic traits. The experience of overcontrolling parents can foster children to develop an excessive dependence on the validation of others for their sense of self (Dickinson & Pincus, 2003), as the experiences of “optimal frustrations” have been hindered (Kohut, 1971). The high feelings of shame for one’s own sense of incompetence and inadequacy (Kohut, 1971), in turn, may favor the onset of psychological distress. In detail, the present study tested a serial mediation model, whereby it was hypothesized that vulnerable narcissism and shame experiences were serial mediators of the relationship between both paternal and maternal overcontrol, on the one hand, and psychological distress, on the other hand. 2. Method 2.1. Procedure and participants All participants were recruited through advertisements on social networking sites (e.g., Instagram and Facebook), and data was collected via an online platform. Participation was voluntary, and before starting data collection, informed consent was obtained from all participants. The study was approved by the University Research Ethics Commission and performed in compliance with the Helsinki Declaration. The only criterion of inclusion was that both parents were alive during their first 16 years of life. A convenience sample of 679 participants was recruited, but 36 participants declared that their parents (one or both) were not alive during their childhood and thus were excluded from the analysis. Therefore, the final sample comprised 643 participants (68 % females; Mage = 29.87 ± 13.00 years). A posteriori statistical power analysis, 2 S. Ghinassi et al. Personality and Individual Di erences 232 (2025) 112848 Table 2 Descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations for all variables. Variables M DS Skewness Kurtosis 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 1. Age 2. MOPS-MO 3. MOPS-FO 4. HSNS 5. ESS-CS 6. ESS-BOS 7. ESS-BS 8. DASS-D 9. DASS-A 10. DASS-S 29.87 4.77 3.73 28.27 26.23 9.73 21.46 9.50 7.69 11.75 13.00 3.01 2.83 7.19 9.27 3.89 6.46 5.70 5.22 5.05 – 0.525 0.708 0.017 0.393 0.140 0.212 0.222 0.478 − 0.086 – − 0.484 − 0.061 − 0.330 − 0.814 − 1.251 − 0.822 − 0.877 − 0.616 − 0.722 – − 0.03 − 0.04 − 0.29* − 0.32* − 0.24* − 0.24* − 0.28* − 0.24* − 0.27* – 0.35* 0.23* 0.23* 0.13* 0.18* 0.25* 0.24* 0.24* – 0.16* 0.19* 0.11* 0.16* 0.23* 0.24* 0.23* – 0.52* 0.35* 0.48* 0.49* 0.38* 0.45* – 0.55* 0.75* 0.57* 0.43* 0.44* – 0.52* 0.44* 0.43* 0.45* – 0.49* 0.39* 0.43* – 0.71* 0.75* – 0.77* Note. MOPS = Measure Of Parental Style; MOPS-MO = MOPS mother’s overcontrol; MOPS-FO = MOPS father’s overcontrol; HSNS = Hypersensitive Narcissism Scale; ESS = Experience of Shame Scale; ESS-CS = ESS Characterological shame; ESS-BOS = ESS Bodily shame; ESS-BS = ESS Behavioral shame; DASS = Depression Anxiety Stress Scale; DASS-D = DASS Depression; DASS-A = DASS Anxiety; DASS-S = DASS Stress. * p < .001. imposing a sample size of N = 643 to detect misspecifications of a model (involving 324 degrees of freedom) corresponding to RMSEA = 0.05 on an alpha error of 0.01 determined an achieved power of 99 %. The sample characteristics are shown in Table 1. Table 3 Descriptive statistics and univariate analyses results by gender. Women (n = 437) 2.2. Measures MOPS-MO MOPS-FO HSNS ESS-CS ESS-BOS ESS-BS DASS-D DASS-A DASS-S Higher scores for each measure are indicative of higher levels of the evaluated dimension. The Italian version (Picardi et al., 2013) of the Measure of Parenting Style (MOPS; Parker et al., 1997) assesses three dysfunctional parental styles (indifference, abuse, and overcontrol) that the participants recall having received from their mother and father during their first 16 years of life. For the aims of the study, only the dimension of Overcontrol was considered (e.g., “sought to make me feel guilty”), which consists of 4 items rated on a 4-point Likert-type scale from 0 (not true at all) to 3 (extremely true). In the current sample, Cronbach’s alphas were 0.75 and 0.71, and McDonald’s Omegas were 0.72 and 0.64 for maternal and paternal overcontrol respectively. The Italian version (Fossati et al., 2009) of the Hypersensitive Narcissism Scale (HSNS; Hendin & Cheek, 1997) was used to assess the level of vulnerable narcissism. The HSNS is a 10-item one-dimensional self-report (e.g., “I often interpret the remarks of others in a personal way”) rated on a 5-point Likert-type scale from 1 (very uncharacteristic or untrue) to 5 (very characteristic or true). In the current sample, Cronbach’s alpha was 0.77 and McDonald’s Omega was 0.76. The Italian version (Casale & Fioravanti, 2017) of the Experience of Shame Scale (ESS; Andrews et al., 2002) was used to assess the tendency to feel ashamed. ESS is a 25-item self-report rated on a 4-point Likerttype, ranging from 1 (not at all) to 4 (very much), designed to mea­ sure three different forms of shame: Characterological (12 items) (e.g., “Have you worried about what other people think of the sort of person you are?”), Bodily (4 items) (e.g., “Have you wanted to hide or conceal your body or any part of it?”), and Behavioral (9 items) (e.g., “Have you worried about what other people think of you when you do something wrong?”). In the current sample, Cronbach’s alphas were 0.93, 0.90, and 0.90, and McDonald’s Omegas were 0.93, 0.90, and 0.90 for the Char­ acterological, Bodily, and Behavioral shame, respectively. Finally, the Italian version (Bottesi et al., 2015) of the Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale (DASS-21; Henry & Crawford, 2005) was used to assess the psychological distress. DASS-21 is a 21-item self-report rated on a 4-point Likert-type, ranging from 0 (it has never happened to me) to 3 (it has happened to me most of the time), resulting in three subscales of 7 items each: Depression (e.g., “I felt I wasn’t worth much as a person”), Anxiety (e.g., “I felt scared without any good reason”), and Stress (e.g., “I tended to over-react to situations”). In the current sample, Cronbach’s alphas were 0.91, 0.86, and 0.89, and McDonald’s Omegas were 0.91, 0.87, and 0.86 for Depression, Anxiety, and Stress, respectively. Men (n = 206) M SD M SD 4.87 3.58 27.90 26.67 10.45 21.98 9.75 8.17 12.25 3.25 2.86 7.24 9.41 3.87 6.52 5.76 5.32 5.02 4.55 4.03 29.04 25.31 8.21 20.35 8.97 6.67 10.67 2.71 2.76 7.03 8.91 3.48 6.18 5.54 4.85 4.96 F (1, 641) 1.54 3.48 3.54 3.05 49.79 9.06 2.64 11.69 13.93 p η2 0.216 0.062 0.061 0.081 <0.001 0.003 0.104 <0.001 <0.001 0.002 0.005 0.005 0.005 0.072 0.014 0.004 0.018 0.021 Note. MOPS = Measure Of Parental Style; MOPS-MO = MOPS mother’s over­ control; MOPS-FO = MOPS father’s overcontrol; HSNS = Hypersensitive Narcissism Scale; ESS = Experience of Shame Scale; ESS-CS = ESS Character­ ological shame; ESS-BOS = ESS Bodily shame; ESS-BS = ESS Behavioral shame; DASS = Depression Anxiety Stress Scale; DASS-D = DASS Depression; DASS-A = DASS Anxiety; DASS-S = DASS Stress; 2.3. Data analyses Descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations between all variables were calculated. Prior to conducting the ensuing analyses, the normal distribution of each variable was investigated using the accepted ranges of ±2 for skewness and kurtosis (George & Mallery, 2021). Moreover, gender differences were explored through a series of univariate analyses of variance (ANOVA). Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) was per­ formed to test the theoretical hypothesized model using the lavaan package (Rosseel, 2012) for the R statistical software (version 4.2.1) with the Maximum Likelihood (ML) estimation method. The itemparceling method was used to limit the number of parameters to be estimated using an empirically equivalent method (Landis et al., 2000). The goodness of fit of the tested model was evaluated using the χ 2 test, the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), the Compara­ tive Fit Index (CFI), and the Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) considering the following cutoff score: χ 2/df < 5, RMSEA < 0.08, CFI > 0.90, and SRMR < 0.08 (Hu & Bentler, 1999; Kline, 2005). Finally, the indirect effects were tested with bias-corrected bootstrapped confidence intervals (CIs) based on 10,000 bootstrap samples (MacKinnon et al., 2004), and CIs that did not include zero were indicative of statistically significant mediation effects (Shrout & Bolger, 2002). 3. Results Since all fields of the survey were mandatory, there were no missing data. Table 2 shows the descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations 3 S. Ghinassi et al. Personality and Individual Di erences 232 (2025) 112848 Fig. 1. Results of tested model and its standardized solution. Note. mo1, mo2, mo3, mo4 = Mother’s overcontrol items; fo1, fo2, fo3, fo4 = Father’s overcontrol items; vn1, vn2, vn3 = Vulnerable Narcissism parcels; cs1, cs2, cs3 = Characterological shame parcels; ess22, ess23, ess24, ess25 = Bodily shame items; bs1, bs2, bs3 = Behavioral shame parcels; de1, de2 = Depression parcels; an1, an2 = Anxiety parcels; st1, st2 = Stress parcels; * = p < .05; ** = p < .001. among the study variables. Significant low-to-moderate correlations in the expected direction were found. Gender differences on the study variables are shown in Table 3. Since age correlated significantly with all the study variables – except maternal and paternal overcontrol – and gender differences were found, the statistical model has been adjusted for both age and gender. Direct effects of age and gender are shown in Supplementary Table S1. The structural model produced adequate fit to the data [χ 2 = 1304.833, df = 324, p < .001; χ 2/df = 4.03; RMSEA = 0.069 (90 % C.I. = 0.065–0.073), CFI = 0.911, SRMR = 0.052]. The variables in the model accounted for 51.30 %, 39.20 %, and 45.80 % of the variance in depression, anxiety, and stress levels, respectively. The standardized estimates are shown in Fig. 1 and all indirect effects in Table 4. As shown, all factor loadings were above the acceptable threshold of .30 (Hair et al., 2009), except for an item of father’s overcontrol. However, retaining this item has been justified due to its theoretical significance and its contribution to the construct of overcontrol (Parker et al., 1997). Moreover, results revealed significant indirect associations between maternal overcontrol – but not paternal – and psychological distress through the mediation of vulnerable narcissism and shame (especially bodily). evidence, the present study hypothesized that the experience of over­ controlling parents could favor the onset of psychological distress and that narcissistic vulnerability and shame proneness are potential path­ ways which could explain this association. Although no single pathway can fully explain the development of depression, anxiety and stress, the present study provides evidence of a potential critical developmental pathway to it, with implications for clinical practice. Results concerning the positive link between PO and narcissism appear to be in line with the psychodynamic perspective, according to which narcissistic vulnerability traits originate from the lack of experi­ ences of “optimal frustration” in the early stages of development (Kohut, 1971). Yet, our results also point out that it is the subjective experience of having experienced overcontrolling mother (and not father) in childhood which may be relevant. In this regard, Cramer (2015) high­ lighted the fact that a maternal – but not paternal – parenting style characterized by excessive control and which does not respond to the legitimate needs of the child (i.e., authoritarian, see Baumrind, 1971) appears to be a positive predictor of vulnerable narcissism. The central role played by the maternal figure is not surprising as the mother is the parent most present in the early stages of the child’s life, during which the personality takes shape and is structured. Taken together, this evi­ dence suggests that the presence of an excessively controlling and intrusive mother may interfere with children’s ability to develop a sense of agency and self-esteem, as well as fostering an overreliance on others for their sense of self, all characteristics associated with narcissistic vulnerability (Dickinson & Pincus, 2003; Miller et al., 2011). The current study is also broadly in line with both theoretical spec­ ulation (Kohut, 1971; Ronningstam, 2009) and empirical evidence (Boursier & Gioia, 2020; Kealy et al., 2023) which identifies the pro­ pensity to shame as a cornerstone affect among individuals with high vulnerable narcissistic traits. Similarly, results showed that vulnerable narcissism significantly predicted shame which, in turn, predict depression, anxiety, and stress, in accordance with previous studies (Casale, 2022; Kealy et al., 2023). The present study builds upon 4. Discussion The present study is based on the premise that having perceived one’s parents as excessively controlling represents a significant risk factor for depression, anxiety and stress (Miller et al., 2018; Sun et al., 2023), as well as for a more widespread personality fragility, namely narcissistic vulnerability (Kohut, 1971). Moreover, there is a general consensus that those with high narcissistic vulnerability traits are more at risk of psychological distress (Kealy et al., 2023) and that shameproneness – a cornerstone feature of vulnerable narcissism (Kohut, 1971; Ronningstam, 2009) – is a key process in such relationship (Kealy et al., 2023). Starting from these theoretical premises and empirical 4 S. Ghinassi et al. Personality and Individual Di erences 232 (2025) 112848 Table 4 Indirect effects. Psychiatric Association, 2022). Arguably, this mediating role could be interpreted in the light of the fact that characterological shame is a stable and global disposition (Andrews et al., 2002), and experiencing it constantly can lead over time to the onset of a depressive symptom­ atology, as changing dispositional aspects could be perceived beyond one’s control. Despite the compelling nature of our findings, the present study is not without limitations. First, given the cross-sectional nature of the study, it is impossible to rule out that feelings of shame and psycho­ logical distress influence each other, resulting in a vicious circle. Therefore, future studies should investigate these links longitudinally. A second limitation concerns the convenience sample used, which is not well balanced by gender and consists mainly of young Italian adults. Some researchers suggested that parental overcontrol might have a different effect (e.g., be more or less damaging) depending on the cul­ ture, as the interpretation of parental behaviors might vary and cultural differences in parenting affect children’s development (e.g., Choe et al., 2023). Following this perspective, we cannot exclude that an effect of paternal overcontrol on vulnerable narcissism could be detected in cultures in which fathers’ responsibilities to take part in child-rearing have become more demanding. Moreover, other parental characteris­ tics (e.g., narcissistic traits) might influence their parenting styles (e.g., Hart et al., 2017) which, in turn, could have an impact on children’ psychological distress. Therefore, this study should be replicated by involving a more representative sample, preferably using probability sampling. Thirdly, in this study, we used self-report measures and, therefore other data collection methodologies should be used (e.g., interviews or implicit measures) to overcome defensive or self-representative biases. Re­ sponses could be affected by the participant’s emotional state at the time of assessment. One last limitation is that parental overcontrol was measured in terms of retrospective appraisal of parental attitudes and behaviors perceived by participants during the first 16 years of life, and this recall could be influenced/distorted by many factors (e.g., current relationship with parents or current psychological distress). Notwithstanding these limitations, the current study makes a contribution to the body of knowledge about the role played by parenting behaviors in the onset of psychological distress. Overall, the results of this study suggest that having experienced an overcontrolling mother favors in children the onset of a narcissistic vulnerability char­ acterized by an overreliance on others for their sense of self. Since the body is the part of oneself more difficult to hide (and has central importance for narcissists) and character is perceived as stable and difficulty to change, it is plausible that shame towards these aspects of the self leads to the onset of negative internal experiences. Clinicians dealing with individuals with high vulnerable narcissistic traits could help them reduce their psychological distress by targeting the underly­ ing narcissistic disturbance (Fjermestad-Noll et al., 2020; for different treatment approaches see Kealy et al., 2017) and working on the level of narratives relating to experiences of maternal overcontrol perceived during childhood and feelings of shame expressed, especially when connected to one’s own body. From a preventive perspective, in­ terventions could be aimed at promoting parenting that takes into consideration the need for autonomy of children, allowing the latter to experience “optimal frustrations” in order to prevent the structuring of traits of narcissistic vulnerability. Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi. org/10.1016/j.paid.2024.112848. β 95 % CI Lower Mother’s overcontrol → Vulnerable narcissism → Characterological shame → Depression Mother’s overcontrol → Vulnerable narcissism → Bodily shame → Depression Mother’s overcontrol → Vulnerable narcissism → Behavioral shame → Depression Mother’s overcontrol → Vulnerable narcissism → Depression Father’s overcontrol → Vulnerable narcissism → Characterological shame → Depression Father’s overcontrol → Vulnerable narcissism → Bodily shame → Depression Father’s overcontrol → Vulnerable narcissism → Behavioral shame → Depression Father’s overcontrol → Vulnerable narcissism → Depression Mother’s overcontrol → Vulnerable narcissism → Characterological shame → Anxiety Mother’s overcontrol → Vulnerable narcissism → Bodily shame → Anxiety Mother’s overcontrol → Vulnerable narcissism → Behavioral shame → Anxiety Mother’s overcontrol → Vulnerable narcissism → Anxiety Father’s overcontrol → Vulnerable narcissism → Characterological shame → Anxiety Father’s overcontrol → Vulnerable narcissism → Bodily shame → Anxiety Father’s overcontrol → Vulnerable narcissism → Behavioral shame → Anxiety Father’s overcontrol → Vulnerable narcissism → Anxiety Mother’s overcontrol → Vulnerable narcissism → Characterological shame → Stress Mother’s overcontrol → Vulnerable narcissism → Bodily shame → Stress Mother’s overcontrol → Vulnerable narcissism → Behavioral shame → Stress Mother’s overcontrol → Vulnerable narcissism → Stress Father’s overcontrol → Vulnerable narcissism → Characterological shame → Stress Father’s overcontrol → Vulnerable narcissism → Bodily shame → Stress Father’s overcontrol → Vulnerable narcissism → Behavioral shame → Stress Father’s overcontrol → Vulnerable narcissism → Stress Upper 0.053 0.026 0.151 0.012 0.001 0.040 − 0.018 − 0.089 0.017 0.089 0.048 0.246 0.025 − 0.001 0.090 0.006 − 0.001 0.022 − 0.008 − 0.047 0.010 0.042 − 0.001 0.132 0.020 − 0.019 0.078 0.025 0.011 0.060 − 0.005 − 0.056 0.037 0.070 0.026 0.185 0.009 − 0.009 0.043 0.012 − 0.001 0.034 − 0.003 − 0.028 0.022 0.033 − 0.001 0.102 − 0.016 − 0.087 0.022 0.023 0.011 0.061 0.019 − 0.022 0.086 0.099 0.054 0.248 − 0.008 − 0.044 0.011 0.011 − 0.001 0.034 0.009 − 0.010 0.050 0.047 − 0.001 0.143 previous findings by showing that some forms of shame are more central than others in explaining the development of specific facets of psycho­ logical distress. In particular, behavioral shame did not significantly mediate the link between vulnerable narcissism and depression, anxiety and stress, whereas shame towards one’s body appears to be of central importance. Individuals with narcissistic vulnerability rely on others’ judgement, and the body is the part least hidden from the gaze of others. Indeed, vulnerable narcissism was found to be consistently associated with body image-related concerns (e.g., Carrotte & Anderson, 2019), and social appearance anxiety (Boursier & Gioia, 2020). Covering up or concealing things one felt ashamed of having done (i.e., behavioral shame) may be less difficult than presenting one’s own body as perfect in any occasion, and this may explain why body shame (but not behavioral shame) was positively associated with depression, anxiety and stress. Our findings also showed that characterological shame plays a sig­ nificant role when it comes to depression. In line with this, a study conducted on adult psychiatric outpatients found that both character­ ological and bodily shame mediated the relationship between narcis­ sistic vulnerability and suicidal ideation (Jaksic et al., 2017), which is a diagnostic criterion for a major depressive disorder (American Funding This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors. 5 S. Ghinassi et al. Personality and Individual Di erences 232 (2025) 112848 CRediT authorship contribution statement of the hypersensitive narcissism scale. Personality and Mental Health, 3(4), 235–247. https://doi.org/10.1002/pmh.92 George, D., & Mallery, P. (2021). IBM SPSS statistics 27 step by step: A simple guide and reference. Routledge. Ghinassi, S., Fioravanti, G., & Casale, S. (2023). Is shame responsible for maladaptive daydreaming among grandiose and vulnerable narcissists? A general population study. Personality and Individual Differences, 206, Article 112122. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.paid.2023.112122 Gilbert, P. (2000). The relationship of shame, social anxiety and depression: The role of the evaluation of social rank. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy: An International Journal of Theory & Practice, 7(3), 174–189. https://doi.org/10.1002/1099-0879 (200007)7:3<174::AID CPP236>3.0.CO;2-U Goodwin, R. D., Weinberger, A. H., Kim, J. H., Wu, M., & Galea, S. (2020). Trends in anxiety among adults in the United States, 2008–2018: Rapid increases among young adults. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 130, 441–446. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2020.08.014 Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2009). Multivariate Data Analysis (7th ed). Prentice Hall. Hart, C. M., Bush-Evans, R. D., Hepper, E. G., & Hickman, H. M. (2017). The children of narcissus: Insights into narcissists’ parenting styles. Personality and Individual Differences, 117, 249–254. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2017.06.019 Hendin, H. M., & Cheek, J. M. (1997). Assessing hypersensitive narcissism: A reexamination of Murray’s narcissism scale. Journal of Research in Personality, 31(4), 588–599. https://doi.org/10.1006/jrpe.1997.2204 Henry, J. D., & Crawford, J. R. (2005). The short-form version of the depression anxiety stress scales (DASS-21): Construct validity and normative data in a large non-clinical sample. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 44(2), 227–239. https://doi.org/ 10.1348/014466505X29657 Horton, R. S. (2011). Parenting as a cause of narcissism. Empirical support for psychodynamic and social learning theories. In W. K. Campbell, & J. D. Miller (Eds.), The handbook of narcissism and narcissistic personality disorder (pp. 181–190). John Wiley & Sons. Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6(1), 1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118 Hudson, J., & Rapee, R. (2005). Psychopathology and the family. Elsevier. Jaksic, N., Marcinko, D., Skocic Hanzek, M., Rebernjak, B., & Ogrodniczuk, J. S. (2017). Experience of shame mediates the relationship between pathological narcissism and suicidal ideation in psychiatric outpatients. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 73(12), 1670–1681. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.22472 Kealy, D., Goodman, G., Rasmussen, B., Weideman, R., & Ogrodniczuk, J. S. (2017). Therapists’ perspectives on optimal treatment for pathological narcissism. Personality Disorders, Theory, Research, and Treatment, 8(1), 35. https://doi.org/ 10.1037/per0000164 Kealy, D., Laverdière, O., Cox, D. W., & Hewitt, P. L. (2023). Childhood emotional neglect and depressive and anxiety symptoms among mental health outpatients: The mediating roles of narcissistic vulnerability and shame. Journal of Mental Health, 32 (1), 24–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638237.2020.1836557 Kim, S., Thibodeau, R., & Jorgensen, R. S. (2011). Shame, guilt, and depressive symptoms: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 137(1), 68. https://doi. org/10.1037/a0021466 Kline, R. B. (2005). Principles and practices of structural equation modeling (2nd ed.). Guilford Press. Kohut, H. (1971). The analysis of the self. A systematic approach to the psychoanalytic treatment of narcissistic personality disorders: International University Press. Landis, R. S., Beal, D. J., & Tesluk, P. E. (2000). A comparison of approaches to forming composite measures in structural equation models. Organizational Research Methods, 3(2), 186–207. https://doi.org/10.1177/109442810032003 MacKinnon, D. P., Lockwood, C. M., & Williams, J. (2004). Confidence limits for the indirect effect: Distribution of the product and resampling methods. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 39(1), 99–128. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327906mbr3901_4 Miller, J. D., Hoffman, B. J., Gaughan, E. T., Gentile, B., Maples, J., & Keith Campbell, W. (2011). Grandiose and vulnerable narcissism: A nomological network analysis. Journal of Personality, 79(5), 1013–1042. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.14676494.2010.00711.x Miller, K. F., Borelli, J. L., & Margolin, G. (2018). Parent–child attunement moderates the prospective link between parental overcontrol and adolescent adjustment. Family Process, 57(3), 679–693. https://doi.org/10.1111/famp.12330 Moreno-Agostino, D., Wu, Y. T., Daskalopoulou, C., Hasan, M. T., Huisman, M., & Prina, M. (2021). Global trends in the prevalence and incidence of depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders, 281, 235–243. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2020.12.035 Parker, G., Roussos, J., Hadzi-Pavlovic, D., Mitchell, P., Wilhelm, K., & Austin, M. P. (1997). The development of a refined measure of dysfunctional parenting and assessment of its relevance in patients with affective disorders. Psychological Medicine, 27(5), 1193–1203. https://doi.org/10.1017/S003329179700545X Parker, G., Tupling, H., & Brown, L. B. (1979). A parental bonding instrument. British Journal of Medical Psychology, 52, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8341.1979. tb02487.x Picardi, A., Tarsitani, L., Toni, A., Maraone, A., Roselli, V., Fabi, E., … Biondi, M. (2013). Validity and reliability of the Italian version of the measure of parental style (MOPS). Journal of Psychopathology, 19, 54–59. Ronningstam, E. (2009). Narcissistic personality disorder: Facing DSM-V. Psychiatric Annals, 39(3), 111–121. https://doi.org/10.3928/00485713-20090301-09 Rosseel, Y. (2012). Lavaan: An R package for structural equation modeling. Journal of Statistical Software, 48(2), 1–36. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v048.i02 Simon Ghinassi: Writing – original draft, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Giulia Fioravanti: Writing – original draft, Supervision, Formal analysis. Silvia Casale: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Methodology, Formal analysis, Conceptualization. Declaration of competing interest None. Data availability Data will be made available on request. References American Psychiatric Association. (2022). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed., text revision). American Psychiatric Press. Andrews, B., Qian, M., & Valentine, J. D. (2002). Predicting depressive symptoms with a new measure of shame: The experience of shame scale. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 41(1), 29–42. https://doi.org/10.1348/014466502163778 Barry, V., Stout, M. E., Lynch, M. E., Mattis, S., Tran, D. Q., Antun, A., … Kempton, C. L. (2020). The effect of psychological distress on health outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. Journal of Health Psychology, 25(2), 227–239. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105319842931 Baumrind, D. (1971). Current patterns of parental authority. Developmental Psychology, 4 (1p2), 1. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0030372 Becker, K. D., Ginsburg, G. S., Domingues, J., & Tein, J. Y. (2010). Maternal control behavior and locus of control: Examining mechanisms in the relation between maternal anxiety disorders and anxiety symptomatology in children. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 38, 533–543. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-0109388-z Borelli, J. L., Margolin, G., & Rasmussen, H. F. (2015). Parental overcontrol as a mechanism explaining the longitudinal association between parent and child anxiety. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 24, 1559–1574. https://doi.org/ 10.1007/s10826-014-9960-1 Bottesi, G., Ghisi, M., Altoè, G., Conforti, E., Melli, G., & Sica, C. (2015). The Italian version of the depression anxiety stress scales-21: Factor structure and psychometric properties on community and clinical samples. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 60, 170–181. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2015.04.005 Boursier, V., & Gioia, F. (2020). Women’s pathological narcissism and its relationship with social appearance anxiety: The mediating role of body shame. Clinical Neuropsychiatry, 17(3), 164–174. https://doi.org/10.36131/ cnfioritieditore20200304 Bowlby, J. (1969). Attachment and Loss: Vol. I: Attachment. Basic Books. Cândea, D. M., & Szentagotai-Tătar, A. (2018). Shame-proneness, guilt-proneness and anxiety symptoms: A meta-analysis. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 58, 78–106. https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2018.07.005 Carrotte, E., & Anderson, J. (2019). Risk factor or protective feature? The roles of grandiose and hypersensitive narcissism in explaining the relationship between selfobjectification and body image concerns. Sex Roles, 80(7–8), 458–468. https://doi. org/10.1007/s11199-018-0948-y Casale, S. (2022). Psychological distress profiles of young adults with vulnerable narcissism traits. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 210(6), 426–431. https://doi.org/10.1097/NMD.0000000000001455 Casale, S., & Fioravanti, G. (2017). Shame experiences and problematic social networking sites use: An unexplored association. Clinical Neuropsychiatry, 14(1), 44–48. Casale, S., Fioravanti, G., & Ghinassi, S. (2023). Applying the self-determination theory to explain the link between perceived parental overprotection and perfectionism dimensions. Personality and Individual Differences, 204, Article 112044. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.paid.2022.112044 Choe, S. Y., Laursen, B., Cheah, C. S. L., Lengua, L. J., Schoppe-Sullivan, S. J., & Bagner, D. M. (2023). Intrusiveness and emotional manipulation as facets of parental psychological control. A culturally and developmentally sensitive reconceptualization. Human Development, 67(2), 69–87. https://doi.org/10.1159/ 000530493 Cramer, P. (2015). Adolescent parenting, identification, and maladaptive narcissism. Psychoanalytic Psychology, 32(4), 559–579. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0038966 Dickinson, K. A., & Pincus, A. L. (2003). Interpersonal analysis of grandiose and vulnerable narcissism. Journal of Personality Disorders, 17, 188–207. https://doi.org/ 10.1521/pedi.17.3.188.22146 Fjermestad-Noll, J., Ronningstam, E., Bach, B., Storebø, O. J., Rosenbaum, B., & Simonsen, E. (2020). Psychotherapeutic treatment of depressive symptoms in patients with narcissistic disturbances: A review. Journal of Contemporary Psychotherapy, 50, 21–28. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10879-019-09437-4 Fossati, A., Borroni, S., Grazioli, F., Dornetti, L., Marcassoli, I., Maffei, C., & Cheek, J. (2009). Tracking the hypersensitive dimension in narcissism: Reliability and validity 6 S. Ghinassi et al. Personality and Individual Di erences 232 (2025) 112848 competence and teacher-child conflict. Early Education and Development, 1-14. https://doi.org/10.1080/10409289.2022.2133495 Van Petegem, S., Antonietti, J. P., Eira Nunes, C., Kins, E., & Soenens, B. (2020). The relationship between maternal overprotection, adolescent internalizing and externalizing problems, and psychological need frustration: A multi-informant study using response surface analysis. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 49(1), 162–177. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-019-01126-8 Winnicott, D. W. (1945). Primitive emotional development. The International Journal of Psycho-Analysis, 26, 137–143. Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2017). Self-determination theory: Autonomy and basic psychological needs in human motivation, social development, and wellness. Guilford. Shrout, P. E., & Bolger, N. (2002). Mediation in experimental and nonexperimental studies: New procedures and recommendations. Psychological Methods, 7(4), 422–445. https://doi.org/10.1037/1082-989X.7.4.422 Shute, R., Maud, M., & McLachlan, A. (2019). The relationship of recalled adverse parenting styles with maladaptive schemas, trait anger, and symptoms of depression and anxiety. Journal of Affective Disorders, 259, 337–348. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. jad.2019.08.048 Sun, J., Liu, J., Cheah, C. S., Fang, Y., Weng, W., Xue, Z., … Li, Y. (2023). Maternal overcontrol and young children’s internalizing problems in China: The roles of social 7