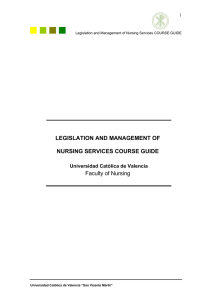

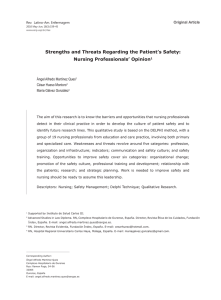

ARTICLE IN PRESS International Journal of Nursing Studies 44 (2007) 1221–1230 www.elsevier.com/locate/ijnurstu Registered nurses’ experiences of daily work, a balance between strain and stimulation: A qualitative study Karin Hallina,, Ella Danielsonb a Department of Health Sciences, Mid Sweden University, Östersund, SE-831 25, Sweden b Institute of Nursing, The Sahlgrenska Academy at Göteborg University, Sweden Received 12 December 2005; received in revised form 3 May 2006; accepted 21 May 2006 Abstract Background: The challenges in the health care have given rise to a highly stressful work situation and a more complicated role for registered nurses (RNs). Qualitative studies about daily work as a whole is limited. It is therefore vital for future development of nursing knowledge and nursing education to recurrently investigate RNs’ experiences of their ability to grasp and manage their daily work situation and to promote a high quality of care. Aim: The aim of this study was to describe RNs’ experiences of their daily work. Methods and participants: This follow up study was carried out involving 15 Swedish RNs 6 years after their graduation. Interviews, conducted with conversational strategy, were chosen for the data collection and content analysis was used to handle the interview texts. Results: The analysis resulted in a main theme ‘to balance strain and stimulation’, two themes and seven sub-themes. The first theme ‘a stressful work situation’ consisted of the sub-themes: ‘to meet all demands’, ‘to be insufficient’, ‘to be unsure of oneself’, and ‘too little contact with patient’. The second theme ‘a stimulating work situation’ consisted of the sub-themes: ‘to encounter patients and health care staff is enriching’, ‘to have the situation under control’, and ‘to have the skills necessary to be independent’. A pattern emerged throughout the themes, which showed that due to the increasing number of patients RNs’ capacity for management, prioritising and planning out of team work, and performing exacting documentation diminished. Conclusion: The RNs’ daily work has been illustrated as a scale of balance that oscillated between strain and stimulation; an oscillation towards strain could lead to a vicious circle. The RNs need support from the start through nursing education and continuously in profession. This is a crucial issue for nursing education and health care sector. r 2006 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. Keywords: Content analysis; Daily work; Experience; Registered nurses; Stimulation; Strain What is already known about the topic? Over the last decades nursing education and health care sector have gone through great challenges. Increasing number of seriously ill patients per nurse is associated with the risks of patients receiving a poorer quality of care and the nurses feeling constant dissatisfaction. Qualitative studies concerning solely skilled RNs’ experiences of their daily work as a whole are limited. What this paper adds Corresponding author. Tel.: +46 63 165652; fax: +46 63 165626. E-mail addresses: [email protected] (K. Hallin), [email protected] (E. Danielson). RNs 0020-7489/$ - see front matter r 2006 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. doi:10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2006.05.011 with six years experience oscillated between strain and stimulation. ARTICLE IN PRESS 1222 K. Hallin, E. Danielson / International Journal of Nursing Studies 44 (2007) 1221–1230 The unbalance diminished the RNs ability for management, and performing exacting documentation. The unbalance was like a vicious circle in which the RNs attempted to acquire control and accomplish quality of care but were unsuccessful in their methods of working. 1. Introduction This study has focus on RNs’ experiences of daily work. Daily work means situations and activities that RNs are involved in every day and in various care contexts as a part of their normal work life in health care. The role of graduated nurses has become more complicated due to the fact that the health care is rapidly developing with high care technology, shortened lengths of stay in hospitals, cost effectiveness and downsizing of staff. These challenges have given rise to a highly stressful work situation for nurses (Aiken et al., 2001) and subsequently undesirable consequences for people in need of care (Aiken et al., 2002a). Several studies all over the world show how nurses experience frustration in their work and how many of them leave the health care (Aiken et al., 2002a; Buerhaus et al., 2005; Sheward et al., 2005) or experience stress and burnout (Severinsson, 2003; Billeter-Koponen and Freden, 2005). Qualitative studies concerning solely skilled RNs’ experiences of their daily work are however limited. Also nursing education has undergone several changes; from being a process of primarily practical and vocational training to having become an university education (Kapborg and Fischbein, 1998; Wheeler et al., 2000). It will be vital for the future development of nursing and nurse competence to recurrently investigate nurses’ experiences of daily work (SOSFS, 2005). Follow up studies, in Sweden as well as in other countries, have focused on graduated nurses’ experiences, primarily on transition during their first years in the profession (Kapborg and Fischbein, 1998; Maben and Clark, 1998; Ramritu and Barnard, 2001) or heterogeneous nursegroups for delimited issues such as work satisfaction (McNeese-Smith, 1999; Makinen et al., 2003; Sheward et al., 2005), identity (Fagermoen, 1997; Fagerberg and Kihlgren, 2001), autonomy (Atencio et al., 2003; Rafferty et al., 2001; Mrayyan, 2004), quality of care (Aiken et al., 2002a, b; Furåker et al., 2004), documentation (Bjorvell et al., 2003; Florin et al., 2005a, b) and reflection (Gustafsson and Fagerberg, 2004) and clinical supervision (Begat et al., 2005). Few studies in Scandinavia have focused on RNs with bachelor degrees and more than 2 years of professional experience (Fagerberg, 2004; Hedberg and Larsson, 2004). In 1993, a new programme for nursing education was introduced in Sweden. This programme involves a 3year study plan, 120 points, and ought to be scientifically based at a bachelor’s degree, in order to provide opportunities for continued studies in specialist education, master’s and doctoral studies. As in many other countries, Swedish RNs are required to be autonomous and to have a high command of the nursing profession. In accordance with scientific knowledge, current laws and ordinances they have to perform and develop their profession. Demands are made on RNs to obtain a holistic view and good quality of care for each patient (SFS, 1982:763). With self-awareness, empathy and an ethical approach the RNs have to meet and teach patients, relatives and team workers (SOSFS, 2005). RNs’ work includes documentation of quality assurance concerning the nursing process (SFS, 1985:562; SOSFS, 1993:20). Acquiring professional nursing skills is a long process, which is not completed at graduation. A lot of research has focused on graduated nurses in specific areas and work conditions, but research about daily work as whole is limited. Therefore, it will be particularly interesting to investigate how one of the first groups in the new 3 years Swedish programme for RNs, experience their daily work 6 years after graduation. 2. Aim The aim of the study was to describe registered nurses’ experiences of their daily work. 3. Method 3.1. Study design A descriptive qualitative research design was used to describe experienced RNs with 6 years post-qualification experiences of daily work. Sandelowski (2000) means that qualitative descriptions are a suitable design of research for description of a phenomenon or a situation; these researchers also keep closer to the data than researchers conducting other qualitative methods with further interpretation. To be able to grasp the whole context of a phenomenon it is essential to understand how the various contexts are experienced by people in a specific environment (Polit and Beck, 2004). Conducting interviews was the method chosen for the data collection and content analysis was used to analyse the texts. The interviews were based on the idea of providing a framework for the questions, in order to enable participants to become actively involved as soon as possible and express their experiences in their own words (Patton, 2004). Content analysis does not require ARTICLE IN PRESS K. Hallin, E. Danielson / International Journal of Nursing Studies 44 (2007) 1221–1230 an underlying theory (Sandelowski, 2000). It is, however, possible to carry out a certain amount of interpretation and theoretically discuss the results. 3.2. Participants In 1996, 20 student nurses were randomized from two classes, a total of 77 students, at two university colleges in the central Sweden. These student nurses were one of the first groups in Sweden studying the new 3-year bachelor programme in nursing education. Twenty of them participated in an earlier interview study before graduation. Fifteen RNs from the same group, 13 women and two men, agreed in 2003 to participate in this study. Five RNs were excluded because two refused participation, one became registered later, another did not work as a RN and one had died. Six of the fifteen RNs had specialist education in areas of medical/surgical care, anesthesia, operation, midwifery and primary health care. Twelve had post-qualification work experiences from Sweden and six had experiences from other countries as Norway, Denmark and England. Eight of the RNs had experiences from more than two (3–6) workplaces. At the time of the interviews 12 participants lived in different parts of Sweden and three lived in Norway. Six worked in the area of medical/surgical care, five in emergency care, two in home or long-term care and two in private care. Their age ranged from 26 to 55 years (median 32 years, mean 34 years). 3.3. Data collection 3.3.1. Interviews The interviews were carried out using one broad open question: ‘‘What are your experiences of the daily work?’’ In order to conduct the interview more on a conversational line several other follow up questions were asked, such as ‘‘What do you mean?’’ or ‘‘Can you develop on that, please?’’ Furthermore additional questions, such as ‘‘Please tell me more about the environment’’ or ‘‘How did you experience the demands?’’ were asked in order to explicate the answers. Both the open question and the additional questions were written down in an interview guide, and the researcher remained free to establish a conversational style. 3.3.2. Procedure The first researcher tested the mode of interview before data collection. After some technical adjustments of the tape-recorder the researcher continued and performed all data collection in a setting suitable for the participants. Nine interviews took place face to face at the participants’ workplace or in their home. In the case of participants living more than 300 km from the 1223 researcher six interviews were conducted by telephone. Each interview lasted 60–90 min and was conducted in a conversational manner in a tranquil environment (Polit and Beck, 2004). The tape-recorded interviews were transcribed verbatim for analysis. Interviews by telephone could be a possible weakness of this study because postures, gestures and eye contact were missing, so consequently some underlying meaning may have been missed (Patton, 2004). Weighing against this is the fact that the participants were not disturbed or distracted by the tape-recorder and the researcher could be a good listener without influencing postures (Polit and Beck, 2004). Compared with in-person interviews, telephone interviews is a reliable method of obtaining detailed exposure information (Cook et al., 2003). Cook et al. showed an excellent level of agreement when they used the same questionnaire and memory aids in comparing a telephone interview with an in-person interview four weeks later. 3.3.3. Data analysis Content analysis was principally made by the first author. This type of analysis can focus on communication with relevance for research in several fields as education and nursing. According to Baxter (1991), Krippendorff (2004) and Patton (2004) content analysis is appropriate to analyse texts from interviews. In this study content analysis, describing experiences of work-aday life, contains interpretation of the underlying meaning of the text that advocates searching inductively for recurrent codes and themes (Baxter, 1991; Patton, 2004). The interviews were read through several times in order to get an overall pictures of the contexts and subjects and the essential features that could be comprehended (Sandelowski, 1995). The actual text was condensed thereafter into meaning units. From these units various codes were labelled and organised in similar areas from which seven sub-themes emerged, as well as two other themes. The two authors discussed in an open and critical diallog all themes and all steps in the analysis process until consensus was achieved (Lincoln and Guba, 1985; Sandelowski, 2000). However, the analysis was not completed because the content of the two themes contained something more; that interlaced into a main theme. 3.3.4. Ethical considerations The study is approved by the Ethic Committee at the university. All information was given both in written and verbally forms before the RNs gave their informed consent. Confidentiality was guaranteed and secured by coding all data. Names and codes were kept separated. There was no relationship of dependency between the interviewer and the participants. ARTICLE IN PRESS 1224 K. Hallin, E. Danielson / International Journal of Nursing Studies 44 (2007) 1221–1230 when newly qualified nurses had to take responsibility meant for experienced RNs, for example: 4. Results The results are presented with the main theme ‘to balance strain and stimulation’ and the two themes; ‘a stressful work situation’ and ‘a stimulating work situation’. According to Fig. 1 the first theme shows with the four sub-themes; to meet all demands; to be insufficient; to be unsure of oneself; too little contact with patients. The second theme shows with the three sub-themes; to encounter patients and qualified health care staff is enriching; to have the situation under control; to have the skills to be independent. 4.1. To balance strain and stimulation ‘To balance strain and stimulation’ means that descriptions of their experiences of their daily oscillated between strain and stimulation. The work was, however, described as containing stressful than stimulating work situations. RNs’ work daily more 4.1.1. A stressful work situation 4.1.1.1. To meet all demands. ‘To meet all demands’ means the RNs’ experience of the work day makes demands on them personally, from patients and colleagues to perform safe quality of care in prerequisites. The RNs described an ever increasing number of patients; staff and skills were not always sufficient or adequate to manage the care of the seriously ill, which consequently led to feelings of frustration: There are currently so many seriously ill patients on hospital wards but you don’t have the resources to increase the number of staff (No. 6). Daily work, which entailed management of a substantial flow of patients, many of whom were transferred between different units in the health care, was described by the RNs as a process leading to arduous paper work and time-costly reports. Situations could become chaotic That you don’t correctly understand what kind of work situation you adjudge RNs today inasmuch we in fact have to strain from being enrolled nurse to being doctor (No. 11). The RNs had high demands on themselves, e.g. they endeavored to complete as many medical and nursing tasks as possible in the time allotted, allow time space for acute situations and tried to avoid having to leave uncompleted tasks for the relieving RN. They stated that it was especially frustrating to be continually interrupted, which forced them to deal with other priorities. One RN who tried to take things easy was unsuccessful in achieving this: As well trying to be more efficient and work more effectively I also tried to take thing a little easier. But it didn’t work. If I try to take things easy and do just one task at time, then tasks will just pile up during the day. You are constantly aware of the fact that something unplanned can happen at any time during the day (No. 15). Demands of adaptability, high working capacity, the strength and patience to handle all sorts of RNs’ assignments, was repeatedly mentioned in the narratives. Organisational changes, an accelerating work pace and sometimes insufficient leadership influenced the daily work situation. The RNs’ frustration and anger was directed towards politicians and decision-makers. The RNs experienced responsibility for documentation as being exacting and the more care the patients needed the more the demands on documentation increased. It appeared that documentation was made when RNs had the amount of time available which was often during brakes or after working shifts with what they had in mind: You must carry out so much documentation nowadays and even if I don’t really think this is wrong I do TO BALANCE STRAIN AND STIMULATION A stressful work situation To meet all demands To be insufficient To be unsure of oneself Too little contact with patients A stimulating work To encounter patients and qualified health care staff is enriching To have the situation under control To have the skills to be independent Fig. 1. RNs’ experience of daily work oscillated between strain and stimulation. ARTICLE IN PRESS K. Hallin, E. Danielson / International Journal of Nursing Studies 44 (2007) 1221–1230 think that it takes too much time from the patients (No. 4). The quality and content of the documentation appeared to vary among the RNs so consequently and seemingly unnecessarily shortcomings in this field caused extra work. 4.1.1.2. To be insufficient. ‘To be insufficient’ means feeling anxious about being inadequate; having missed something at the end of the working day. There was a feeling of coercion in fulfilling the tasks of both the RNs and enrolled nurses (ENs). Some of the RNs received scant understanding for their work situation from the ENs: I almost have to prioritise not carrying out the work of a RN, in order to catch up on basic nursing care, which is surely wrong (No.15). Difficulties in delegating tasks to ENs were something that currently appeared to cause prevailing conflicts, due unwillingness to help or lack of knowledge since their education no longer aims to assist RNs. The RNs explained if they constantly had interruptions and met with delays, caused by and a heavy workload, they took ‘‘shortcuts’’. This led to the nurses did not pay active attention to what the patients were trying to tell them or they avoided answering the patients’ questions. Consequences of this could be especially troublesome in situations in which RNs lacked experience and did not have the time to acquire the relevant knowledge: Have no time to think things through clearly. Problems can arise that you have no idea how to resolve and you just do not have the time to look for the relevant information or try to find out (No. 13). Despite delays the RN managed to complete assignments by taking no pauses, having a cup of coffee instead of eating lunch or staying on after the relieving staff came on duty. Another solution was to start the shift earlier in order to get the work done in time. The charges carried out on spare time were mainly completing the documentation or the doctors0 prescriptions and being prepared to help out in urgent situations. The RNs described feelings of having time only for the most important tasks. 4.1.1.3. To be unsure of oneself. ‘To be unsure of one self’ means wanting to be able to influence development work but the ability to achieve changes varied. The descriptions show that earlier fruitless discussions, lack of time and resistance from colleagues and managements inhibited creativity and rendered the RNs passive, which meant that they adopted a wait-and-see policy. 1225 Obligation to take part in research and development work was revealed as a desire either to participate in it or dissociate from it. None of the RNs was involved in any research or development project of their own. They could, however engage in reports related to evaluations and changes of organizations, as well as become updated in certain fields of nursing, e.g. caring for wounds, documentation and drug store issues. The RNs elucidated that they fell short in one respect, i.e. when they compared their ambitions in development and research with those of the doctors: You see, I feel that our County Council has low priority on nursing research (No. 5). It is more difficult because we have no tradition in nursing research yI haven’t noticed anything else than answering questionnaires sent from colleagues who are doing this as part of their education (No. 7). Supervision of nurse-students was as well as research and development described as important but arduous and time-expensive despite the degree of interest. 4.1.1.4. Too little contact with patients. ‘Too little contact with patients’ means impossibility to create sufficient chances for achieving a general picture and confirmation that the patients are receiving optimal care and have a feeling of security. When the contact was unsatisfactory RNs experienced a poorer quality of care. Reasons for the lack of time the RN has to spend with each patient were a continuous substantial flow of patients and demands for documentation: Everything must be written down—it must all be documented yThen I wonder so to say, how much time will be left over to see to the patient? (No.13). Time together with patient was described by the RNs as a reward. The RNs on anesthetic wards and in the operating theatre wanted to establish shared commitments with a medical or surgery ward, because they missed the contact with patients and were not satisfied with this. 4.1.2. A stimulating work situation 4.1.2.1. To encounter patients and qualified health care staff is enriching. ‘To encounter patients and qualified health care staff is enriching’ means good relationship. It was the encounters with patients that enriched the RNs’ working day most of all. A sense of wellbeing as well as professional and personal growth emerged when there was time to talk to and support the patient. The support was described as a close relationship in both joy and deep sorrow. Exacting relationships with patients were also experienced as enlightening if they provided an opportunity for follow-up talks. Some of the RNs participated sporadically in professional clinical super- ARTICLE IN PRESS 1226 K. Hallin, E. Danielson / International Journal of Nursing Studies 44 (2007) 1221–1230 vision while others were of the opinion that such supervision was unnecessary because there were a sufficient number of staffs in the working team that could supply back up: Some patients are troublesome and I think you should be allowed to say this. Because I mean you are no superman. If you can talk about this then at least you have a chance to do something about it. And I think that we nursing staff on the whole are too bad at telling what we really feely The more trouble and complaints you experience the more you need to talk about it (No. 6). At workplaces with sufficient qualified staff and staffmembers standing up for each, the RNs felt pleasure and experienced security; their daily work situation was enriched. In such environments the RNs took their time to supervise and instruct ENs and when ENs worked more autonomously the RNs obtained load-relieving. 4.1.2.2. To have the situation under control. ‘To have the situation under control’ means it is like receiving a ‘‘vitamin injection’’, when everything is going well and it is possible to manage a chaotic situation. If RNs experienced lack of control they were regarded as vulnerable and unable to go on with any further workload. In order to carry out various work situations adequately the RNs related that it was necessary to acquire routines as soon as possible, not to undertake too many assignments and to think about teamwork. The RNs, who planned together with ENs and took time to train them and delegate tasks to them, explained that in the long run they found that they obtained both relief in their workload and an increased ability to control their daily work. The RNs’ descriptions show that planning with an additional timetable contributed to a more tolerable work situation. Those who managed to keep the timetable, to finish their duties and to facilitate the hand-over to the relieving colleague, described a feeling of accomplishment; this way proved RNs’ capacity as ‘‘highly skilled’’ and subsequently received feedback on performed efforts. RNs, who had few interruptions and were responsible for few patients, with ample time for care, described this as a privilege. The time that other RNs spent on admissions and discharges could in their case be spent on ‘‘their’’ patients. They were afraid that this would deteriorate if hospital managers became aware of their pleasant work environment: But you don’t talk out loud about this, because you are sure that the hospital managers will put a stop to this way of working. It is as if you mustn’t have things too good (No. 10). 4.1.2.3. To have the skills necessary to be independent. ‘To have the skills necessary to be independent’ was expressed to not standing nonplussed without knowing what to do, to be capable of making prompt decisions and to be able to act from a general picture of any given situation. Confirmation of having done the right thing provided satisfaction: Sometimes it takes a long time before you can get hold of a doctor. I do not just stand around nonplussed—I am really capable and ready to act. Yes, it’s good to know you can handle the situation (No. 11). The number of workmates and RNs’ ability for instruction and organisation influenced the sensation of autonomy. Challenges, assignments of various contents, elements of acute situations in moderate quantities were all considered as being an added stimulation in the working day. When acute circumstances arise and the patient survives you really feel that you are doing something worthwhile (No. 14). At the time one’s head feels ready to explode, but these are short intervals and perhaps this is what makes nursing a terrifically exciting profession (No. 3). RNs sometimes choose to work nights or change their place of work in order to acquire stimulation in the form of new challenges, more independent work and to feel more in control of their work situation. 5. Discussion 5.1. Result discussion This qualitative study has provided insight in regarding the daily work of RNs’ with more than 6 years experience of the profession. The main result shows a scale of balance that oscillated between strain and stimulation; an oscillation between two poles, an ideal day full of stimulation or a day filled with strain. On the whole oscillation seemed to be related to the various experiences RNs had of their work; i.e. of the time that available for each patient, their ability to promote the quality of care and their independence. However, a pattern also emerged throughout the results, which showed that due to the increasing number of patients and the skills of the staffs, RNs’ ability for management, prioritising and planning out of team work diminished. The RNs seemed to be unstructured for their work regarding documentation. The patient contact appeared to be RNs’ greatest source of rewards and personal development, but if they met with delays, they took unsafe ‘‘shortcuts’’. ARTICLE IN PRESS K. Hallin, E. Danielson / International Journal of Nursing Studies 44 (2007) 1221–1230 RNs, who experienced a stimulating work situation, possessed the skills necessary for working independently and for making prompt decisions from a general concept of a limited number of patients. Experiences of autonomy and team work with doctors and qualified health care staff were important and strong predictors of stimulation. RNs in these cases compared chaotic situations to a ‘vitamin injection’. If they also had managed to complete their duties at the end of the day, they praised themselves as being ‘highly skilled’. Nurses feel satisfied when they are able to provide good care and complete the given work tasks (McNeeseSmith, 1999) without too many interruptions (Hedberg and Larsson, 2004). However, since the different parts of the result in our study, in reality were woven into circumstances of different situations, the balance of RNs’ scales tipped more towards strain than stimulation. The price of such negative balance can lead to serious consequences for the patients and the RNs themselves (Aiken et al., 2002a, b). Nurses are more than other staff members ‘‘at hand’’ for all kind of interactions and task-solutions that can lead to fragmentary work. Interpersonal and technological interruptions can be features which could jeopardize the decision-making outcome (Hedberg and Larsson, 2004). As it will be discussed further, when RNs’ were frequently interrupted and when assignments were too large compared to available time, the risk for miscalculating and taking perilous short cuts increased. RNs, who experienced a stressful work situation, expressed all variations of strain in accordance with RNs in transition (Gerrish, 2000; Wheeler et al., 2000; Ramritu and Barnard, 2001). The RNs were conscious of the need to meet with all the demands in order to provide care that was both holistic and of good quality for each patient but they felt powerless to set limits for their workload. That is worth considering when an increasing number of seriously ill patients per nurse is clearly associated with the risks of patients receiving a poorer quality of care and the nurses feeling constant dissatisfaction (Aiken et al., 2001, 2002a; Sheward et al., 2005). Feelings of insufficiency were described by RNs’ as being worried and anxious about being inadequate and having missed something at the end of the working day. Delays could lead to serious consequences when RNs chose to take ‘‘shortcuts’’ and avoided answering questions or avoided supervising patients and students. Such behavior became especially troublesome and unsafe for patients in situations in which RNs lacked experience and did not take the time to acquire the relevant knowledge. Such circumstances are directly contrary to laws and ordinances that apply to professional nursing (SFS, 1982:763; SOSFS, 2005). The leading question is what kind of support is available for a RN, when increasing demands lead to serious situation where something goes drastically wrong (Ahern and McDonald, 2002). According to Stacciarini 1227 and Troccoli (2004) critical thinking is significantly related to occupational stress and physical and psychological ill-health. No doubt, high care complexity induces attention for the patient, but the knowledge is limited here about how much RNs ought to fulfill in their daily duties. Some of the RNs had difficulties to delegate tasks to ENs and tried to accomplish the tasks for both, which resulted in work duplication. Reasons given why RNs did not delegate tasks to their team colleagues were that this was due to ENs’ unwillingness and inadequate knowledge. In such situations these RNs need further encouragement to take on a leading position with the power to solve conflicts, to delegate, and to pinpoint and prioritise timesaving strategies. Even Adams and Bond (2000) confirm this with their results that show how workload and work organisation influence both nurses’ and patients’ wellbeing. Furthermore, unsuccessful planning and failure to set priorities can lead to both confusion, disorganization and poor care for patients (Fagerberg, 2004) but unfortunately little empirical research has been carried out of regarding nurses’ skills in prioritising (Hendry and Walker, 2004). RNs in our study, who had trained ENs and also took time to plan the work together with them, stated that in the long run they achieved both relief a lightening of their workload and an increased ability to control their daily work. To be unsure of oneself dealt with the RNs’ ability to influence development and changes in their workplaces. These RNs strove to provide nursing care independently and with personal responsibility but adopted a wait-and see policy regarded participating development work. They were aware of the need of a research-based practice, but in spite of this felt unsure about the time available to conduct research. In line with earlier findings nursing research was seldom prioritised (Kajermo et al., 2001; Kuuppelomaki and Tuomi, 2005). The RNs experienced that they had too little contact with patients, which resulted in two described effects: lack of rewards and impossibility for achieving a general picture of each patient. These results are similar with the study by Fagerberg (2004), who found that RNs, 5 years after graduation, worked hard at bonding with their patients and tried to organize the daily work situation according to patients’ needs and safety. It is interesting and in accordance with results by Sheward et al. (2005) that the patient contact appeared to be RNs’ greatest source of rewards and personal development. The RNs seemed to be unstructured for their work regarding documentation. This circumstance was like a vicious circle; RNs, in their attempt to acquire control and accomplish a high quality of care, were unsuccessful in their methods of working. Documentation was repeatedly mentioned as being troublesome, time-costly and was experienced as stealing time from the patients. The documentation was often carried out during breaks with ARTICLE IN PRESS 1228 K. Hallin, E. Danielson / International Journal of Nursing Studies 44 (2007) 1221–1230 a considerable amount of unreliable notes; texts that were linguistically unclear, which were created from memory. They experienced that defective documents led to more work. Why do RNs not document bedside and continuously while they observe and talk with patients? Such procedures would provide RNs with more time with the patient, more reliable documentation and would automatically involve the patients with the plans and priorities for their health care. RNs are autonomously responsible for documenting the nursing process by a legally enforced quality assurance of RNs’ work (Ehnfors and ThorellEkstrand, 1992; SFS, 1985:562), but evaluations indicate that nurses with different experiences rarely document nursing diagnosis, nursing goals and nursing outcomes (Tornvall et al., 2004). In the initial phase, 48 h, RNs have considerable difficulty in identifying the needs of their patients, particularly problems with nutrition, sleep, pain, and emotions/spirituality (Florin et al., 2005a). To obtain better congruence between nurses’ and patients’ descriptions structured recording following chronological order can be used (Ehrenberg and Ehnfors, 2001). Furthermore, education followed by constant discussions and facilitating forms for recording seem to be necessary (Bjorvell et al., 2003; Florin et al., 2005b; Tornvall et al., 2004). RNs appeared to balance their experience of stressful and stimulating work as a modest and reserved position on the scale. Various frustrations from the daily work situation were reported but no one talked about solutions. The RNs chose to consult colleagues for support but their descriptions of receiving back-up depicted more a tête-à-tête than conversation using reflection as a tool (Gustafsson and Fagerberg, 2004). This can undoubtedly have helped for the moment, but in the long run personal development and work changes should be promoted by structured professional discussions. Reflections with colleagues, in combination with sessions of clinical supervisions, can eliminate the risk of proceeding with routines based on tradition. Significant positive correlations are presented between clinical supervision, work demands, collaboration and good communication (Begat et al., 2005). Unfortunately, most of the RNs in our study declined structured clinical supervision, but due to this, such supervision could then prove to be an excellent tool for helping nurses to handle work demands and achieve control of the daily work situation (Begat et al., 2005). It would also be a good help for handling factors that diminished nurses’ autonomy; like autocratic management, increased workload and poor collaboration with doctors (Mrayyan, 2004; Rafferty et al., 2001). 5.2. Methodological considerations The trustworthiness has been assured through using Lincoln and Guba’s (1985) criteria for dependability, credibility and transferability. As factors of instability are changeable over time the trustworthiness of this study has been valued on the grounds that the participants narrated experiences from their actual daily work situation with the same questions (Sandelowski, 1993). One strength of the study was the fact that sampled participants with similar education and various experiences increase the chances to shed light on the research from a variety of aspects (Patton, 2004). Another strength was that the researchers, both RN and educator, were familiar with both concepts and contexts (Sandelowski, 2000). In contrast, there is a slight risk that the researchers may have missed certain information both in the interviews and the analysis, due to their comprehension of nursing education and the conditions of the nursing profession (Patton, 2004). Our study’s results have a rich content that ought to be transferred both to nursing education and health care organisation. 6. Conclusion This study has described RNs’ with six years experiences of their daily work situation. The strength of this study has been to show this work situation as a whole. Other studies have reported parts of this work with heterogeneous participants. The main results regarding this work situation has been illustrated as a scale of balance that oscillated between strain and stimulation; an oscillation between two poles, an ideal day full of stimulation or a day filled with strain. The oscillation seemed to be related to the various experiences RNs had of their work; i.e. of the time that available for each patient, their ability to promote the quality of care, skills for team work and to be independent. A clearly pattern emerged throughout the results, which showed that due to the increasing number of patients and the skills of the staffs, RNs’ capacity for management, prioritising and planning out of team work, diminished. The RNs seemed to be unstructured for their work regarding documentation. These circumstances were like a vicious circle; RNs, in their attempt to acquire control and accomplish quality of care, were unsuccessful in their methods of working. As experienced RNs can have difficult to hold the balance between strain and stimulation, how difficult is it for newly qualified? Our study shows that is a need for RNs to find a more successful and personal way to perform their daily work in an ever increasing downsizings and reorganization of the health care sector; it is necessary to receive support from the start through the nursing education and continuously in the profession. This is a crucial issue for nursing education on different levels and health care sector. Furthermore our study points to the need for further research regarding skilled RNs’ experiences, in order to focus on the trends and difficulties that are found in daily works situations. ARTICLE IN PRESS K. Hallin, E. Danielson / International Journal of Nursing Studies 44 (2007) 1221–1230 Acknowledgements We would like to acknowledge the contribution of the nurses involved in this study and would like to thank them for allowing us to share their unique experiences. References Adams, A., Bond, S., 2000. Hospital nurses’ job satisfaction, individual and organizational characteristics. Journal of Advanced Nursing 32 (3), 536–543. Ahern, K., McDonald, S., 2002. The beliefs of nurses who were involved in a whistleblowing event. Journal of Advanced Nursing 38 (3), 303–309. Aiken, L.H., Clarke, S.P., Sloane, D.M., Sochalski, J.A., Busse, R., Clarke, H., Giovannetti, P., Hunt, J., Rafferty, A.M., Shamian, J., 2001. Nurses’ reports on hospital care in five countries. Health Affairs 20 (3), 43–53. Aiken, L.H., Clarke, S.P., Sloane, D.M., 2002a. Hospital staffing, organization, and quality of care: cross-national findings. International Journal for Quality in Health Care 14 (1), 5–13. Aiken, L.H., Clarke, S.P., Sloane, D.M., Sochalski, J., Silber, J.H., 2002b. Hospital nurse staffing and patient mortality, nurse burnout, and job dissatisfaction. JAMA 288 (16), 1987–1993. Atencio, B.L., Cohen, J., Gorenberg, B., 2003. Nurse retention: is it worth it? Nursing Economics 21 (6), 262–268. Baxter, L.A., 1991. Content analysis. In: Montgomery, B.M., Duck, S. (Eds.), Studying Interpersonal Interaction. Guilford press, New York, pp. 239–254. Begat, I., Ellefsen, B., Severinsson, E., 2005. Nurses’ satisfaction with their work environment and the outcomes of clinical nursing supervision on nurses’ experiences of wellbeing—a Norwegian study. Journal of Nursing Management 13 (3), 221–230. Billeter-Koponen, S., Freden, L., 2005. Long-term stress, burnout and patient-nurse relations: qualitative interview study about nurses’ experiences. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences 19 (1), 20–27. Bjorvell, C., Wredling, R., Thorell-Ekstrand, I., 2003. Prerequisites and consequences of nursing documentation in patient records as perceived by a group of Registered Nurses. Journal of Clinical Nursing 12 (2), 206–214. Buerhaus, P., Donelan, K., Ulrich, B., Norman, L., Dittus, R., 2005. Is the shortage of hospital registered nurses getting better or worse? Findings from two recent national surveys of RNs. Nursing Economics 23 (2), 61–71,96. Cook, L.S., White, J.L., Stuart, G.C., Magliocco, A.M., 2003. The reliability of telephone interviews compared with inperson interviews using memory aids. Annals of Epidemiology 13 (7), 495–501. Ehnfors, M., Thorell-Ekstrand, I., 1992. Omvårdnad i patientjournalen (Nursing in the Patient Record). In: Vårdförbundets forsknings- och utvecklingsrapport nr 38. Svenska hälso- och sjukvårdens tjänstemannaförbund, Stockholm, pp. 125 (In Swedish). Ehrenberg, A., Ehnfors, M., 2001. The accuracy of patient records in Swedish nursing homes: congruence of record 1229 content and nurses’ and patients’ descriptions. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences 15 (4), 303–310. Fagerberg, I., 2004. Registered nurses’ work experiences: personal accounts integrated with professional identity. Journal of Advanced Nursing 46 (3), 284–291. Fagerberg, I., Kihlgren, M., 2001. Experiencing a nurse identity: the meaning of identity to Swedish registered nurses 2 years. Journal of Advanced Nursing 34 (1), 137–145. Fagermoen, M.S., 1997. Professional identity: values embedded in meaningful nursing practice. Journal of Advanced Nursing 25 (3), 434–441. Florin, J., Ehrenberg, A., Ehnfors, M., 2005a. Patients’ and nurses’ perceptions of nursing problems in an acute care setting. Journal of Advanced Nursing 51 (2), 140–149. Florin, J., Ehrenberg, A., Ehnfors, M., 2005b. Quality of nursing diagnoses: evaluation of an educational intervention. International Journal of Terminologies and Classifications 16 (2), 33–43. Furåker, C., Hellstrom-Muhli, U., Walldal, E., 2004. Quality of care in relation to a critical pathway from the staff’s perspective. Journal of Nursing Management 12 (5), 309–316. Gerrish, K., 2000. Still fumbling along? A comparative study of the newly qualified nurse’s perception of the transition from student to qualified nurse. Journal of Advanced Nursing 32 (2), 473–480. Gustafsson, C., Fagerberg, I., 2004. Reflection, the way to professional development? Journal of Clinical Nursing 13 (3), 271–280. Hedberg, B., Larsson, U.S., 2004. Environmental elements affecting the decision-making process in nursing practice. Journal of Clinical Nursing 13 (3), 316–324. Hendry, C., Walker, A., 2004. Priority setting in clinical nursing practice: literature review. Journal of Advance Nursing 47 (4), 427–436. Kajermo, K.N., Nordstrom, G., Krusebrant, A., Lutzen, K., 2001. Nurses’ experiences of research utilization within the framework of an educational programme. Journal of Clinical Nursing 10 (5), 671–681. Kapborg, I.D., Fischbein, S., 1998. Nurse education and professional work: transition problems? Nurse Education Today 18 (2), 165–171. Krippendorff, K., 2004. Content Analysis: An Introduction to its Methodology, second ed. Sage, Thousand Oaks, CA. Kuuppelomaki, M., Tuomi, J., 2005. Finnish nurses’ attitudes towards nursing research and related factors. International Journal of Nursing Studies 42 (2), 187–196. Lincoln, Y.S., Guba, E.G., 1985. Naturalistic Inquiry. Sage, Beverly Hills, CA. Maben, J., Clark, J.M., 1998. Project 2000 diplomates’ perceptions of their experiences of transition from student to staff nurse. Journal of Clinical Nursing 7 (2), 145–153. Makinen, A., Kivimaki, M., Elovainio, M., Virtanen, M., Bond, S., 2003. Organization of nursing care as a determinant of job satisfaction among hospital nurses. Journal of Nursing Management 11 (5), 299–306. McNeese-Smith, D.K., 1999. A content analysis of staff nurse descriptions of job satisfaction and dissatisfaction. Journal of Advanced Nursing 29 (6), 1332–1341. ARTICLE IN PRESS 1230 K. Hallin, E. Danielson / International Journal of Nursing Studies 44 (2007) 1221–1230 Mrayyan, M.T., 2004. Nurses’ autonomy: influence of nurse managers’ actions. Journal of Advanced Nursing 45 (3), 326–336. Patton, M.Q., 2004. Qualitative Research & Evaluation Methods, third ed. SAGE, London. Polit, D.F., Beck, C.T., 2004. Nursing Research: Principles and Methods. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia. Rafferty, A.M., Ball, J., Aiken, L.H., 2001. Are teamwork and professional autonomy compatible, and do they result in improved hospital care? Quality in Health Care 10 (Suppl 2), ii32–ii37. Ramritu, P.L., Barnard, A., 2001. New nurse graduates’ understanding of competence. International Council of Nurses, International Nursing Review 48 (1), 47–57. Sandelowski, M., 1993. Rigor or rigor mortis: the problem of rigor in qualitative research revisited. ANS, Advances in Nursing Science 16 (2), 1–8. Sandelowski, M., 1995. Qualitative analysis: what it is and how to begin. Research in Nursing & Health 18 (4), 371–375. Sandelowski, M., 2000. Whatever happened to qualitative description? Research in Nursing and Health 23 (4), 334–340. Severinsson, E., 2003. Moral stress and burnout: qualitative content analysis. Nursing and Health Sciences 5 (1), 59–66. SFS, 1982:763. Hälso-och sjukvårdslagen (Health and Medical Act). In: Swedish Statue Book 2005. Liber AB. Stockholm, (in Swedish) SFS, 1985:562. Patientjournallagen (The patient Record Act). In: Swedish Statue Book 2005. Liber AB, Stockholm, (in Swedish). Sheward, L., Hunt, J., Hagen, S., Macleod, M., Ball, J., 2005. The relationship between UK hospital nurse staffing and emotional exhaustion and job dissatisfaction. Journal of Nursing Management 13 (1), 51–60. SOSFS, 1993:20. Socialstyrelsens föreskrifter och allmänna råd om patientjournallagen (Advisory instructions on the patient record act). In: Swedish Statue Book 2005. Socialstyrelsen (The national Board of Health and Welfare), Stockholm, (in Swedish). SOSFS, 2005. Socialstyrelsens allmänna råd om kompetenskrav för legitimerad sjuksköterska (Advisory instructions on demands of competence for registered nurse). Socialstyrelsen (The National Board of Health and Welfare), Stockholm (in Swedish). Stacciarini, J.M., Troccoli, B.T., 2004. Occupational stress and constructive thinking: health and job satisfaction. Journal of Advanced Nursing 46 (5), 480–487. Tornvall, E., Wilhelmsson, S., Wahren, L.K., 2004. Electronic nursing documentation in primary health care. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences 18 (3), 310–317. Wheeler, H.H., Cross, V., Anthony, D., 2000. Limitations, frustrations and opportunities: a follow-up study of nursing graduates from the University of Birmingham, England. Journal of Advanced Nursing 32 (4), 842–856.