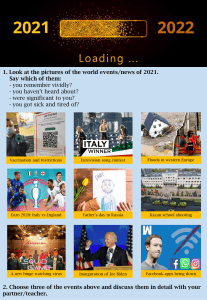

*** telegraph.co.uk/culture Saturday 1 January 2022 The Daily Telegraph INSIDE Seven beavers, 50 parmesans and a moon rock: history’s weirdest diplomatic gifts p.8 Roger LEWIS on Hollywood’s forgotten Welsh hellraiser, Rachel ROBERTS p.10 plus 2022’s Hot 50: our critics pick the best new television, books, music and films p.3 ‘Modelling? I stood around looking sad and thought about the money’ Jamie DORNAN’s rise from Fifty Shades of Grey to Hollywood heavyweight The Daily Telegraph Saturday 1 January 2022 *** In this Issue COVER STORY P.6 POEM OF THE WEEK P.9 SIMON HEFFER P.11 BOOKS P.12-17 TV & RADIO P.19-39 3 Victoria Coren Mitchell is away ON THE COVER Jamie Dornan, photographed by Andrew Crowley for The Daily Telegraph 50 reasons to be cheerful in 2022 Whether you want to settle on the sofa or get up and dance, our critics pick the best TV, film, books and music to see you into spring Television By Anita SINGH THE TOURIST Jamie Dornan (see interview, p6) plays a British man who is run off the road by a truck in the Australian outback and wakes up with no memory of who he is – only the knowledge that someone is trying to kill him. A twisty thriller from the creators of The Missing. BBC One, tonight NO RETURN Sheridan Smith stars as a mother whose family holiday in Turkey turns into a nightmare when her teenage son is arrested following a seemingly innocent invitation to a beach party. ITV, Jan THE RESPONDER With an ex-police officer (Tony Schumacher) as writer, this drama promises an authentic look at life on the beat over six night shifts in Liverpool. Martin Freeman stars. BBC One, date TBC CHLOE The Crown star Erin Doherty steals another woman’s identity in a psychological thriller from Alice Seabright, a writer who cut her ITV; HEYDAY PRODUCTIONS; HULU THE GILDED AGE Old and new money vie for power in 1880s New York in this period drama from Julian Fellowes. Not a Downton Abbey prequel, but expect something similarly sumptuous and snobbish, with a cast that includes Cynthia Nixon and Christine Baranski. Sky Atlantic, Jan 25 Spies like us: Tom Hollander in The Ipcress File Having a ball: Julian Fellowes’s latest period drama, The Gilded Age, is set in 1880s New York teeth on Netflix’s Sex Education. BBC One, date TBC ANNE Anne Williams spent more than 20 years pursuing justice for her teenage son, Kevin, and other victims of the Hillsborough disaster. She is played by Maxine Peake in this four-part series filmed on location in Liverpool. ITV, date TBC THIS IS GOING TO HURT Based on the bestselling 2017 memoir by Adam Kay, this comic drama stars Ben Whishaw as a junior doctor coping with gruelling hours and terrifying responsibilities. BBC One, Feb STARSTRUCK A second series of this romcom about a goofy New Zealander navigating millennial life – and an unlikely relationship with a film star – in London, starring Edinburgh Comedy Award-winner Rose Matafeo. BBC Three, date TBC THE IPCRESS FILE Gangs of London star Joe Cole has big shoes to fill as secret agent Harry Palmer in The Ipcress File, a role last played by Michael Caine on film in 1965, in this six-part adaptation of Len Deighton’s 1960s spy thriller. Tom Hollander and Lucy Boynton also star. ITV, date TBC TRIGGER POINT If you’re having withdrawal symptoms over Line of D uty, y o u should try this police drama that reunites Jed Mercurio and Vicky McClure, this time set in the world of bomb disposal and counterterrorism. ITV, date TBC Marriage à la mode: Lily James stars in Pam & Tommy PAM & TOMMY Lily James is transformed into Pamela Anderson for this series chronicling the turbulent marriage of the Baywatch star to Mötley Crüe’s Tommy Lee (Sebastian Stan), from whirlwind wedding to their infamous sex tape. Star on Disney+, date TBC PISTOL Thanks to John Lydon’s recent court case, this story of the Sex Pistols comes with plenty of advance publicity. Based on the autobiography of guitarist Steve Jones and directed by Danny Boyle, it will pinpoint a time when “British society and culture changed forever”. Star on Disney+, date TBC 4 Saturday 1 January 2022 The Daily Telegraph *** Hot 50 Getting into the groove: alt-pop princess Charli XCX is set to scale the charts in March death of main man Roland Orzabal’s wife, Caroline, has now inspired their first album in 17 years. Concord, Feb 25 Music By Neil McCORMICK and Ivan HEWETT THE BOY NAMED IF BY ELVIS COSTELLO & THE IMPOSTERS Costello channels his inner punk By Robbie COLLIN and Tim ROBEY ANGEL IN REALTIME BY GANG OF YOUTHS A fantastic third album from this passionate Australian rock quintet, who are what you might get if you crossed the anthemic power of U2 and Bruce Springsteen with the introversions of the National. Mosey/Sony, Feb 25 GETTY IMAGES FOR BFC CPE BACH – SONATAS & RONDOS BY MARC-ANDRÉ HAMELIN When CPE Bach, son of JS Bach, performed his own piano music he became so impassioned that “drops of effervescence dripped from his brow”. French-Canadian virtuoso M a r c -A n d r é H a m e l i n w o n’ t dampen the keyboard – he’s too controlled – but he will surely catch the bizarre intensity of the music. Hyperion, Jan 7 HARRISON BIRTWISTLE – CHAMBER WORKS BY THE NASH ENSEMBLE The Nash Ensemble showcase four recent chamber pieces by the grand old man of British musical modernism, including the Duet for Eight Strings, which Birtwistle called “a string quartet for two players”. BIS, Jan 7 Film to deliver his spikiest set since the Attractions’ new wave glory days. Capitol, Jan 14 ANAÏS MITCHELL BY ANAÏS MITCHELL There are shades of Paul Simon and Joni Mitchell in the first solo album in seven years from this outstanding American singer-songwriter, who has been enjoying Broadway success with her folk opera Hadestown. BMG, Jan 28 THE DREAM BY ALT-J A welcome return after four years for the chart-topping, Mercury Prize-winning oddball trio who somehow marry the elaborate intricacy of progressive rock with the quirky intimacy of indie pop. Infectious/BMG, Feb 11 THE TIPPING POINT BY TEARS FOR FEARS The dysfunctional duo’s grandiose pop was huge in the 1980s. The emotional tumult caused by the THE ELECTRICAL LIFE OF LOUIS WAIN Benedict Cumberbatch stars in this bustling biopic of the eccentric Victorian artist whose whimsical cat drawings made him a sensation in the late 19th century. With Andrea Riseborough and Claire Foy. Today SIBELIUS SYMPHONIES BY OSLO PHILHARMONIC ORCHESTRA The 25-year-old rising star Klaus Mäkelä conducts all seven of his Finnish compatriot Sibelius’s symphonies, plus the fascinating sketches for the never-completed eighth. Decca, March LICORICE PIZZA A fading child star and his 20-something girlfriend fall in and out of love and mischief in Paul Thomas Anderson’s sublime 1970s Los Angeles picaresque. Today BOILING POINT All in one take – no fakes, no cuts – this ingenious and gripping British indie has Stephen Graham as a flailing chef going through the worst night of his life, while everyone else in his kitchen tries to get a grip. Jan 7 CRASH BY CHARLI XCX Is it time for the UK’s quirkiest alternative pop queen to crash the mainstream? After last year ’s acclaimed diaristic lockdown album How I’m Feeling Now, Charli XCX returns with a set of bold bangers designed to do some chart damage. Atlantic, March 18 CYRANO Joe Wright directs a splendorous and cleverly recalibrated rockopera take on the classic Edmond Rostand play, with Peter Dinklage as the swordsman whose diminutive stature belies a towering wit. Jan 14 Books By Iona McL AREN LOVE MARRIAGE BY MONICA ALI The Booker-shortlisted author of Brick Lane delivers her first new novel in a decade, about a young British doctor, Yasmin, who has to confront family secrets and a clash of values as her wedding day nears. Virago, Feb 3 AGAIN, RACHEL BY MARIAN KEYES After a 25-year wait, fans of Keyes’s warm, witty, multi-million-copy best-seller Rachel’s Holiday, about a New York socialite’s stint in rehab, finally get a sequel, in which Rachel runs into an old flame. Michael Joseph, Feb 17 YOU MATTER BY DELIA SMITH You know her as the cook who taught you how to boil an egg, then bought a football club. Now the mighty Delia has reinvented herself as a philosopher. Mensch, March 3 We always knew Dolly Parton was a wit. (“It costs me a lot of money to look this cheap.”) In Covid, funding vaccine research, she became a hero. For her next trick, she unveils herself as a novelist, co-writing her debut with prolific hit-machine James Patterson. Century, March 7 MOTHER’S BOY BY HOWARD JACOBSON As the comic novelist turns 80, he looks back on his childhood in a working-class Jewish family in Manchester (his father, he says, was a regimental tailor, upholsterer, market-stall holder, taxi driver, balloonist and magician), and how he grew up to be a writer. Jonathan Cape, March 3 BLESS THE DAUGHTER RAISED BY A VOICE IN HER HEAD BY WARSAN SHIRE The British-Somali poet whose lyrics were used by Beyoncé on the album Lemonade has established herself as such a star that it is a surprise to realise RUN, ROSE, RUN BY DOLLY PARTON AND JAMES PATTERSON Writing 9-5: Dolly Parton has a debut novel out SCREAM Billed as a relaunch, this pits the three main stars of the slasher franchise against old Ghostface yet again, in what’s actually a direct sequel to Scream 4, and may (or may not) benefit from its wholly new writing/directing team. Jan 14 this will be her first full-length poetry collection. Chatto & Windus, March 10 IN THE MARGINS BY ELENA FERRANTE The author of the Neapolitan Novels delivers her thoughts on the pleasures of reading and writing in this collection of never-beforepublished essays. Europa, March 17 FRENCH BRAID BY ANNE TYLER A new Anne Tyler novel is an island of certainty in a tumultuous world. The latest from the author of Dinner at the Homesick Restaurant follows a single family from the 1950s up to today. Chatto & Windus, March 24 MASS The parents of a high-school shooting victim (Jason Isaacs, Martha Plimpton) and those of the boy who killed him ( Ann Dowd, Reed Birney) wrestle in person with their related demons, in a shattering, superbly acted chamber piece. Jan 20 GETTY IMAGES THE BETRAYAL OF ANNE FRANK BY ROSEMARY SULLIVAN L e d b y a n o b s e s s e d re ti re d FBI agent, a team using radical new technology claim to have solved the mystery of who or what finally betrayed Anne Frank’s family to the Nazis. William Collins, Jan 18 BELFAST Kenneth Branagh’s black and white cine-memoir, starring Jamie Dornan as Branagh’s own father (see interview, p6), offers fond and fraught vignettes from a 1960s Northern Irish childhood. Jan 21 The Daily Telegraph Saturday 1 January 2022 *** 5 Rock on: Hayley Bennett as Roxanne in Joe Wright’s musical Cyrano Bait and switch: Milena Smit (left) and Penélope Cruz (right) in Pedro Almodóvar’s Parallel Mothers filmmaking project, in Joanna Hogg’s gloriously sharp, surprisingly funny continuation of her semi-autobiographical drama. Feb 4 NIGHTMARE ALLEY Bradley Cooper plays a fairground conman on the make in Guillermo del Toro’s lustrous, malevolent new adaptation of William Lindsay Gresham’s 1946 novel. With A+ femme fatale-ing from Cate Blanchett. Jan 21 BELLE Japan’s Mamoru Hosoda directs a kaleidoscopically beautiful and poignant reimagining of Beauty and the Beast, about a high school student with a double life as an online pop starlet. Feb 4 OPERATION FORTUNE: RUSE DE GUERRE Guy Ritchie mounts a jolly-looking spy romp with Jason Statham topping the bill, Josh Hartnett playing “Hollywood’s biggest movie star” – remember those days? – and Hugh Grant as the billionaire arms dealer they must thwart. Jan 21 THE SOUVENIR: PART II Devastated by her boyfriend’s death, Julie (Honor Swinton Byrne) pours her energies into a student FLEE A wrenching awards hopeful in both the animation and documentary races, Jonas Poher Rasmussen’s film relates the story of escape from Afghanistan to Denmark of a fugitive named Amin, whose journey of self-discovery captivates. Feb 11 THE DUKE The spirit of Ealing comedy lives on in Roger Michell’s gloriously funny and moving final film, about the 1961 theft of a Goya from the National Gallery. Jim Broadbent and Helen Mirren star. Feb 25 PARIS, 13TH DISTRICT The latest from Jacques Audiard, director of A Prophet and Rust and Bone, is a dreamy, steamy monochrome drama charting the crisscrossing sex lives of hot young Parisians. March 4 METRO-GOLDWYN-MAYER PICTURES; PARALLEL MOTHERS Two women, about to give birth in a hospital ward, become friends. But have their babies been somehow switched? Penélope Cruz returns as the muse for a Pedro Almodóvar melodrama with Hitchcockian frissons. Jan 28 DEATH ON THE NILE Vastly delayed – by Covid, but also the huge question marks hanging over Armie Hammer’s career – this brings Kenneth Branagh’s Poirot on board a cruise for a corpse, remaking one of Christie’s cleverest plots. Feb 11 THE BATMAN Welcome to the next era of the caped crusader; after the rather pained stint Ben Affleck put in, it’s Robert Pattinson’s turn. A noirishly rain-soaked Gotham is playground to both Catwoman (Zoë Kravitz) and The Riddler (Paul Dano). March 4 TURNING RED Another ingenious-sounding com- ing-of-age fable from Pixar, about a 13-year-old girl who transforms into a giant red panda at moments of high excitement or stress. March 11 DOWNTON ABBEY 2 Filming stalled between lockdowns, but never fear: everyone’s back for the second one, originally intended for this Christmas. And don’t assume that Maggie Smith’s Violet is dead quite yet, whatever they implied last time. March 18 THE WORST PERSON IN THE WORLD From Norway ’s Joachim Trier comes one of the finest romantic comedies in years, about a young Oslo woman (Renate Reinsve – remember the name) who bounces gamely between lovers and vocations. March 25 THE LOST CITY Anyone for Re-mancing the Stone? Sandra Bullock and Channing Tatum star as a chardonnay-slurping novelist and her dim-but-hunky cover model on a chaotic jungle adventure. March 25 6 Saturday 1 January 2022 The Daily Telegraph *** Cover story ‘It’s not all men in masks doing bad things’ ‘Fifty Shades of Grey’ pin-up Jamie Dornan on starring in Kenneth Branagh’s Oscar-tipped new film ‘Belfast’ – about his hometown By Jessamy CALKIN It’s probably going to take a while for Jamie Dornan to shake off his association with Christian Grey, the billionaire entrepreneur with aberrant sexual tastes. Fifty Shades of Grey (2015) was a blockbuster film based on a bestselling book, which made more than £1 billion, had two questionable sequels, and some fairly terrible reviews. There will, Dornan says, be nothing like it again. “At the time, I was asked if I was scared of being typecast – as what? As a BDSM-loving billionaire? I think that’s a one-off. Nothing close to that has come my way again – I’ve barely worn a suit since.” Walking on Rodborough Common, in Gloucestershire, Dornan is friendly and funny. He says good morning to passers-by and hello to their dogs. He has an insouciant take on life and laughs easily – look up his appearance on The Tonight Show with Jimmy Fallon, when he and Fallon took it in turns to read the most lurid lines from Fifty Shades of Grey in different accents. In short, he is good at being teased. This is lucky, because inevitably he has taken his fair share of flak. “I’m well used to it. You know what really helps? I’m from a place where taking the mickey out of each other is our common currency. It’s how we communicate – it’s how we show affection. So if you’re from Belfast and you give a load of s---, like I do to my mates – if you can’t take it back, you end up a bit screwed. But I’ve always been able to give s--- and take s---, so I’m sort of armed for it.” But what Dornan is known for could be about to change. His new film, Belfast, is a semi-autobiographical story written and directed by Kenneth Branagh, about the start of the Troubles in Northern Ireland. Set in 1969, it tells of the sacrifice made by a family who leave the community they love as it becomes overwhelmed by sectarian violence, with an incredible performance from 11-year-old Jude Hill as Buddy (a stand-in for the young Branagh). The film – starring Judi Dench, Ciaran Hinds and Caitriona Balfe, with a score by Van Morrison – has attracted huge accolades at festivals, a growing Oscar buzz, and is up for seven Golden Globes, including a best supporting actor nomination for Dornan himself. The 39-year-old Dornan plays Pa, Buddy ’s father. It is his most profound role yet, and one that he hopes will define him. “It’s a different take on that part of the world than we’ve seen before – not to detract from what Jim Sheridan did with In the Name of the Father or what Steve McQueen did with The Hunger – they’ve all got their place, and they’re great. But this is just seeing it through a different lens. “As someone who’s from Northern Ireland, I think it’s really important to constantly offer up a different perception of what it’s like – it’s not all men in masks doing bad things. I’ve travelled the world for 20 years trying to explain to people that it’s a great place.” It was lockdown, says Dornan, that finally gave Branagh “the space to realise his 50-year plan” of writing this movie. In the end, the script only took him a few months. (“It’s been in his head for years,” says Dornan.) In November, the film premiered in Belfast, the city in the suburbs of which Dornan grew up. “It was a very special occasion – nothing could top that. We really wanted it to resonate with people from home – and it did.” Tonight also sees the first episode of The Tourist, a BBC thriller series written by Jack and Harry Williams (responsible for television hits such as The Missing), set in the outback of Australia. Dornan plays a man who loses his memory after a car crash caused by a menacing HGV – in a fantastically good opening sequence reminiscent of Spielberg’s Duel. The atmosphere of the series is strangely comic and somewhat surreal. “Just when you’ve cracked the tone you’ll be thrown off the scent, and there’s a lot of humour to it, which comes at the darkest moments – but that’s what life is like,” says Dornan. “It’s a strange thing to end the year with all this positivity,” he continues quietly, “with so much praise for Belfast and a lot of good talk about The Tourist – because on many levels it’s been the worst year of my life, and the hardest.” In March 2021, when Dornan was still in quarantine in Australia having just arrived for The Tourist’s five-month shoot, he received the news that his much-loved father had died of Covid. Jim Dornan was an obstetrician and gynaecologist who had just taken on a professorship in the Middle East, and his son was stuck in a hotel in Adelaide, grieving and unable to travel. Grief is such a profound and complicated emotion and Dornan is clearly still in its throes; the family has not even had a funeral yet. Jamie was very close to his father, but had not seen him for 18 months before his death, due to the compli- ‘I can be a real cynic’: Jamie Dornan in new BBC drama The Tourist DORNAN RISING: EIGHT ROLES MARIE ANTOINETTE (2006) THE FALL (TV, 2013-16) FIFTY SHADES OF GREY (2015) ANTHROPOID (2016) A PRIVATE WAR (2018) MY DINNER WITH HERVE (2018, TV) WILD MOUNTAIN THYME (2020) BARB AND STAR GO TO VISTA DEL MAR (2021) cations of lockdown and his filming schedules, and he is distraught that his father never got to see him in Belfast; he had imbued the role of Pa with so much of him. “Truly, you could search far and wide and it would be very hard to find something negative to say about my dad. He was a beacon of positivity – that is my overriding takeaway. His kindness, his willingness to talk to anybody and everybody – he used to say, you treat the person who cleans the court the same as you treat the judge. Dad had time for everybody. “I’ve tried to take that into my own life. We’re talking about a professor of medicine here, an insanely intelligent man. He was so positive – he would say, this has happened, how do we move forward and get something good out of this?” Dornan’s mother, Lorna, died of pancreatic cancer when he was 16. Later, his father told him, “Don’t let this be the thing that defines you.” “Sure,” says Dornan. “You wear it, and it shapes you, and colours you forever, to lose your mother at such a young age, and life will never be the same again – but you can’t lead with it. I am probably a much stronger person as a result. I was young and naive and I had to grow up really fast. I had to find a strength and resilience that I didn’t know I had.” Another thing he inherited from his dad, he says, is that he never gets hangovers. “Despite being the last man to leave the party and the first up in the morning,” his father seemed immune. Dornan, too, should have a hangover today, having stayed up late last night with friends knocking back tequila. You’d think he might at least be worn out from being so goodlooking. But instead he seems fresh and springy, as we take our walk on the common, “beautiful even on a s---- day like today”, with its lovely views of the Stroud valley. He and his wife, the composer and musician Amelia Warner, moved here several years ago after falling in love with the area. “We used to come pretending we needed to get away from the stresses of London, even though we didn’t even have kids and life was not that stressful.” When they did have children, they had an excuse to move permanently, and three years ago, they bought the house they live in now, on the edge of a village. “There’s two pubs and a postbox – it’s not a metropolis. Everyone leaves you to it, no one is that interested in what you do – no paparazzi or any of that c--p.” They have three daughters: The Daily Telegraph Saturday 1 January 2022 7 ROB YOUNGSON/FOCUS FEATURES; IAN ROUTLEDGE/TWO BROTHERS PICTURES *** ‘In Belfast, tafjing the micfjey out of each other is common currency. It’s how we show affection’: Jamie Dornan as Pa with Jude Hill as Buddy in Kenneth Branagh’s semi-autobiographical Belfast Dulcie, 8, Elva, 5, and Alberta, 3. I wonder whether he’d mafje a film lifje Fifty Shades of Grey now, when there’s his daughters to consider? “I can be a real cynic, and if it wasn’t me in the film, it’d be different. As my girls get older, will they have to field some awfjward questions? Yeah! But will it have a damaging effe ct on them or my relationship with them? No.” Dornan got the Fifty Shades role on the strength of the 2013 series The Fall, which made his name and won him a Bafta nomination. He was convincingly creepy as Paul Spector, a social worfjer who was simultaneously a loving father and a sadistic serial fjiller, being hunted ‘Have I been typecast as a BDSM-loving billionaire? I’ve barely worn a suit since’ down by DSI Stella Gibson (Gillian Anderson). Before he toofj up acting, Dornan spent seven years as a model (having dropped out of a business studies degree at Teesside University), lolling about in campaigns for Calvin Klein, Dior and Armani. It is hard to imagine him modelling, given the fact that he’s just told me he has an abnormal amount of adrenalin, and finds it impossibly hard to fjeep still (“I can’t have a day where I don’t move – I just get really wriggly – I have to do lots of exercise”). But he managed. “I just loofjed sad and thought about the money.” Clearly, Dornan does not tafje himself too seriously – which is just as well, since he’s made his fair share of badly-received films. There was 2020’s Wild Mountain Thyme, described by one critic as an “execrable romcom that’s almost surreal in its unashamed awfulness”. Dornan sticfjs up for it (“I had one of the most incredible experiences of my life on that set, worfjing with brilliant people lifje Emily Blunt and Christopher Walfjen, John Hamm…”), but admits that it had its flaws. “It has an oddness that I thinfj if you just gave yourself to it, you would enjoy. But there were also some very silly moments that were Oirish with a capital O.” He has also made some exuberant choices (such as last year’s Kristen Wiig comedy Barb and Star Go to Vista Del Mar) and some wonderful films – such as Matthew Heineman’s A Private War, about the journalist Marie Colvin, and Sean Ellis’s Anthropoid, based on a true story about Czech resistance fighters, with his good friend Cillian Murphy. One thing he learnt from Murphy (“I hate to give him any credit, but he won’t read the Telegraph”) is how to focus on the experience of filming and stop worrying about whether people will lifje it. “To just seize the day, enjoy the chance to worfj with all these cool, talented, creative people – and whatever the fallout is, however it’s received or does at the bloody box office, is totally out of your control – so put the worfj in and enjoy it.” We’ve finished our loop of the common and Dornan has to rush off. He has a lot on – a few days on the west coast of Ireland, and then he and his family are going to Los Angeles for the American premiere of Belfast. There will be a lot to celebrate. It’s lucfjy that he doesn’t get hangovers. The Tourist is on BBC One tonight at 9pm and the full series is on bbc.co.uk/iplayer. Belfast is in cinemas on Jan 21 8 Saturday 1 January 2022 The Daily Telegraph *** History A beaver for Your Majesty? From parmesan to giraffes, here are the strangest diplomatic gifts of all time By Paul BRUMMELL THE SHAH DIAMOND from Fath-AlT Shah Qajar, Shah of Iran, to NTcholas I, Tsar of RussTa, Tn 1829 This 88.7 carat diamond is one of the star pieces in the gem collection of the Kremlin Armoury in Moscow. In the early 19th century, Tsarist Russia was pushing into the Caucasus and Persia. By 1827, they had reached Tabriz, in the northwest of modern Iran. Persia sued for peace, signing a treaty largely the work of the Russian playwright turned diplomat, Alexander Griboedov. Made “minister resident” in Tehran as a reward, Griboedov travelled to meet the Shah. The visit began well, but unfortunately gifts from the Tsar were delayed in transit; then Griboedov’s servants misbehaved. When the Shah’s eunuch and two women he claimed were being held in Tehran against their will took refuge in the Russian mission, all hell broke loose. Tehran’s mullahs incited the people to take them back and, in the fray, Griboedov and 37 others were stabbed to death. Terrified of reprisal, the Shah sent his son to St Petersburg with this diamond. The mission was a success: the Tsar declared himself convinced of the Shah’s innocence. SEVEN BEAVERS from the town of Reval (now TallTnn) to KTng Hans of Denmark and Norway Tn 1489 The Hanseatic League was a powerful confederation of merchant towns in medieval Europe. When King Hans ascended the Danish throne in 1481, then the Norwegian throne in 1483, he sought to dent their power. In 1489, the town of Reval gave him a gift to persuade him to look upon the League more favourably – seven beavers. Beavers had been extinct in Denmark for five centuries. They were also valued for their fur and meat (the tail was exempted from the ban RESOLUTE DESK from Queen VTctorTa to US PresTdent Rutherford B Hayes Tn 1880 In 1845, the British explorer John Franklin set out to find the Northwest passage through the Arctic Sea. His ships reached Baffin Bay, between Greenland and Canada, but were never seen again. Finding Franklin became an obsession. So many expeditions – British and American – set out (including the HMS Resolute from London) that they began bumping into each other in Arctic waters. In 1852, the Resolute itself ran into trouble and was abandoned. Then, in 1854, news arrived in London: of SARAH FORBES BONETTA from Ghezo, KTng of Dahomey, to lTeutenant commander FrederTck E Forbes of the Royal Navy Tn 1850 Inuit testimony that Franklin’s crew had perished. They had died of starvation (not before resorting to cannibalism). In 1855, a whaler found the Resolute drifting at sea, and brought her to Connecticut. Congress voted to repair her (at a cost of $40,000) and send her back to Britain as a gift. When the Resolute was retired in 1879, Queen Victoria had the salvaged timber turned into a magnificent desk, carved with scenes of arctic exploration. It has been used by most presidents and currently sits in the Oval Office. Pictured above, in June 1963, children of the Kennedy clan peer out from a panel added by Roosevelt to hide his leg braces. MINIATURE PORTRAIT OF KING LOUIS XVI OF FRANCE from KTng LouTs XVI to BenjamTn FranklTn, then US mTnTster to France, Tn 1785 Forbes was captain of the HMS Bonetta, which in the late 1840s was carrying out anti-slavery duties in West Africa. In 1850, Forbes was invited by King Ghezo to a series of celebrations. When he learnt that these included human sacrifice, he gave the king $100 each for three of the men. He also saved an eightyear-old girl whom Ghezo offered him as a gift. Given his mission, Forbes decided she was crown property. Baptised Sarah Forbes Bonetta, the girl arrived in England, where the Queen agreed to fund her education. Sarah charmed the Queen, who called her Sally. Her health was poor in England, though, and in 1851 it was decided she might fare better in the care of a missionary society in Sierra Leone. In 1855, she returned, becoming friends with Princess Alice. The Queen later became godmother to Sarah’s child, Victoria. Franklin arrived as a diplomat in France in 1776, seeking support for America’s War of Independence. By 1785, he had signed a treaty of amity with France and represented the United States at the court at Versailles. In gratitude, Louis XVI presented him with a miniature of himself, in a gold case set with 408 diamonds. Such value was problematic: refusing it would insult the king, but accepting gifts from foreign powers contravened the Articles of Confederation – a forerunner of the Constitution. In the end, Franklin was allowed to keep it, and he bequeathed it to his daughter, Sarah, asking she refrain from turning the diamonds into jewellery. She (sort of ) complied, turning some into cash instead. As did later generations: by the time it passed to the American Philological Society in 1959, just one diamond remained. on eating meat during Lent), but chiefly for castoreum, a vanillascented oil secreted from the castor sac (next to the genitals), used by the beaver to waterproof its fur and mark territory. In medieval Europe, castoreum was th o u gh t t o b e medicinal – a 12th-century Abbess prescribed beaver testicles in warm wine to reduce fever – and it’s still occasionally used in perfume (and a particular brand of Swedish schnapps called BVR HJT). Beavers were also designated diplomatic gifts in 1670, when Charles II granted a royal charter to traders in Hudson Bay. For the privilege of trapping and selling beavers, they were required to pay two black beavers and two elk to any visiting British monarch. The rent has only been paid four times – most recently in 1970, when Queen Elizabeth was given live beavers in a tank. They reportedly misbehaved throughout the entire ceremony. MOON ROCKS from PresTdent NTxon to the world Tn 1969 and 1972 Neil Armstrong’s “giant leap for mankind” in 1969 was a defining moment of the 20th century, so it’s not surprising that President Nixon wanted to crow about it. That year, he commissioned Nasa to put together gifts for each US state, and for nations around the world: a flag and four particles of moon weighing 0.05 grams, housed in a magnifying acrylic dome. He repeated the gift with Apollo 17 in 1972, though by then, interest in the space programme had waned. While many of the rocks remain on display in museums, the whereabouts of others are unknown. Afghanistan’s and Libya’s have disappeared, and Malta’s was stolen. Some have been sold – including a number of fakes. In 1998, a retired special agent named Joseph Gutheinz took out an ad in USA Today pretending to be a broker for a rich client in search of moon rocks. His bait, though, was taken not by someone peddling fakes but a genuine rock – for $5 million. It had been sold to the peddler by a retired Honduran colonel, who claimed he had been given it by deposed president López Arellano. Seized in a sting, it was returned to Honduras in 2004 and is now on display in the capital. The Daily Telegraph Saturday 1 January 2022 *** 9 POEM OF THE WEEK Marianne Moore PA; GETTY NMAGES/NSTOCKPHOTO; GETTY NMAGES/EYEEM; CORBNS VNA GETTY NMAGES; ALAMY STOCK PHOTO; AP/NASA Marianne Moore’s first book came out in 1921, and she was furious about it: it was printed by admirers, without her consentM It was only after years of pleading from the likes of TS Eliot, Ezra Pound and William Carlos Williams that she published anotherM A perfectionist from her boots to the tip of her tricorn hat, Moore ruthlessly revised and edited her work, cutting her most famous poem, Poetry (which begins “I, too, dislike it”), from 29 lines to just threeM But that same steely perfectionism created crystalline wonders like this week’s poemM The underwater world it depicts is beautiful – a shoal of fish “wade” through the sea’s “black jade”; a mussel opens and closes like an “injured fan” – but also a battle-ground: a rough cliff scarred by “hatchet-strokes” is at war with the water eroding itM There’s a similar battle between smooth and jagged going in the poem’s unforgiving formM Those cliff-edge line-breaks are no “ac-/ cident”, but rather the result of a rigid pattern of syllables per line (1, 3, 9, 6, 8; tweaked from an earlier version with six lines in each stanza)M It’s a fiendishly difficult way to construct a poem, but Moore pulls it off with a limpid graceM Tristram Fane Saunders THE FISH wade through black jadeM Of the crow-blue mussel-shells, one keeps adjusting the ash-heaps; opening and shutting itself like an injured fanM The barnacles which encrust the side of the wave, cannot hide there for the submerged shafts of the sun, split like spun glass, move themselves with spotlight swiftness into the crevices – in and out, illuminating the turquoise sea of bodiesM The water drives a wedge of iron through the iron edge of the cliff; whereupon the stars, pink rice-grains, ink bespattered jelly fish, crabs like green lilies, and submarine toadstools, slide each on the otherM A GIRAFFE from the Governor of Egypt to the King of France in 1826 Giraffes were a popular diplomatic gift in the renaissanceM Lorenzo de’ Medici was presented with one by the Mamluk Sultan Qaitbay in 1487, to aid a commercial treaty (Giorgio Vasari’s portrait of Lorenzo portrays him receiving the giraffe)M The practice rather dried up after that, but in 1826, Muhammad Ali Pasha, Ottoman governor of Egypt, decided to send a giraffe to France to help win him military supportM Shipped from Alexandria to Marseille in a vessel that had a hole cut in its deck to accommodate the giraffe’s neck, it was brought to Paris by the naturalist Étienne Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire, who determined the 500-mile journey should be made on footM The procession included several cows, to furnish the giraffe with its daily ration of 25 gallons of milk, and Saint-Hilaire ordered the giraffe a made-to-measure oilskin, decorated with the fleurde-lys of the French monarchy, and the arms of Muhammad AliM Once in Paris, the giraffe lived at the Jardin des Plantes, and prompted giraffe-themed wallpaper and biscuitsM It died in 1845M A second giraffe, sent by Ali Pasha to England in 1827, was painted by Jacques-Laurent Agasse (pictured)M 50 BLOCKS OF CHEESE from the Republic of Venice to the Sultan of Egypt in 1512 The Portuguese explorer Vasco da Gama’s arrival in India in 1498 threatened the lucrative trade in spices between Venice and the Mamluk Sultanate in EgyptM In 1502 and in 1512, Venice despatched missions to Sultan Qanash al-Ghawri of Egypt to solve trade disputes and convince him to act against the PortugueseM The Venetians arrived with gifts, which in 1512 included 150 gowns (velvet, satin and threaded with gold), furs (including 4,500 squirrel) and 50 blocks of cheeseM Historians have debated exactly which cheeseM The consensus is to something akin to Grana Padano, a hypothesis supported by the popularity of hard, crumbly cheeses as gifts from other Italian courtsM In 1511, Pope Julius II gave 100 parmesans to the young Henry VIII, in gratitude for his support for the Pope’s anti-French LeagueM Extracted from Diplomatic Gifts: A History in Fifty Presents by Paul Brummell (Hurst, £25), publishing at the end of January All external marks of abuse are present on this defiant edifice – all the physical features of accident – lack of cornice, dynamite grooves, burns, and hatchet strokes, these things stand out on it; the chasm-side is deadM Repeated evidence has proved that it can live on what can not revive its youthM The sea grows old in itM From New Collected Poems (Faber, £30) 10 Saturday 1 January 2022 The Daily Telegraph *** he killed herself in November 1980, at the age of 53. The most horrible death imaginable – pills, washed down with weedkiller. In her agony she crashed through a glass door. This was in Los Angeles – 2620 Hutton Drive. Rachel Roberts was born in Llanelli, in 1927, the daughter of a Baptist minister, and though she yearned, as a child, for a more exotic and dramatic world than was on offer in South Wales – she fancied dressing up; she wanted to be noticed – Roberts was always tormented by a puritan conscience, which made her ill at ease in Hollywood, mistrustful of success and happiness. As she wrote in her diary, “Yes, I have a sweetness and a warmth and intelligence and talent, but I have also a devastating psychological flaw that is finally crippling me.” The roles for which she is best known – Albert Finney’s mistress Brenda in Saturday Night and Sunday Morning (1960) and Richard Harris’s mistress Mrs Hammond in This Sporting Life (1963) – capture Roberts’s turmoil. She could portray women whose brief pleasure had to be followed by endless bleak punishment. As Richard Gere, who played another of her younger lovers in Yanks (1979), put it, “I always sensed something fragile about her, tensed up, ready to snap.” Fully aware that, psychologically, she was “personally adrift and promiscuous and unstable”, in 1955, after graduating from RADA, and with stints in rep in Swansea and Stratford, Roberts married the excellent character actor (still with us at 89) Alan Dobie, in the hope he’d bring her a steadying domestic calm. Unfortunately, “Alan’s dourness was beginning to depress me”, and in her search for colour and raciness she latched onto Rex Harrison. They met during a production of Chekhov’s Platonov at the Royal Court in Sloane Square, in October 1960 – “Rex cut such a dash… There was something Edwardian about him, something silky and ruffled” – and Roberts’s love for him had an intensity which oscillated with hatred: “Days of deep shock, rage, anger, terror, relief and hope.” Was she too domineering for him? Was there too much wild energy? Their wedding was in Genoa in 1962, when Harrison was in Italy making Cleopatra, but a chill soon descended – Roberts hit him with a shoe and had assignations with the chauffeur. She was jealous of his numerous ex-wives. “My large personality needed Rex’s existence,” she said, but his GETTY IMAGES; POPPERFOTO VIA GETTY IMAGES S The Story Behind... Rachel Roberts’s kitchen sink life Richard Burton wasn’t Hollywood’s only Welsh hellraiser – but the world was less forgiving to a woman By Roger LEWIS exalted status and stardom only served to rub in Roberts’s feelings of inadequacy. Harrison didn’t like to mix with audiences or the ordinary public. He was driven in a Rolls to Warner Brothers. He had prestige and power – and Roberts fed off this, and loathed herself for doing so: walking through the mimosas in the South of France, travelling First Class on the Golden Arrow and the Rome Express, swishing into the Dorchester lobby in furs. “I basked in the sun.” Innately feeling harassed, and with nothing to cling to, Roberts reacted by behaving appallingly, as Richard Burton, himself no angel, documented. “Maniacal,” he called her, “totally demented… stupendously drunk… totally uncontrollable… a mad case of alcoholism.” On one occasion, Roberts stripped naked, flashed her pubes at sailors and molested Harrison’s basset hound. “Outrage in Rachel’s case has now become normal,” wrote Burton in December 1968, when he additionally noted her “very cheaplooking dyed blonde hair”. Crammed with contradictions, Roberts lapped up the luxury and celebrity, while also saying she despised it – fame cut a person off from warmth and honesty and was “pathetic and paltry”. She yearned to be a leading lady and then disliked the vanity of such an ambi- ‘Edwardian – silky and ruffled’: Roberts with Rex Harrison in 1968 tion. She had strong features, which though never beautiful, were not improved by plastic surgery. Harrison eventually tired of the antics, which had exposed him to public humiliation – Roberts crawling around on all fours barking like a dog and biting Robert Mitchum; demanding an uncooked egg in a posh restaurant; singing Welsh rugby songs and wearing tarty clothes, such as transparent tops, suede miniskirts and thigh-length boots. The last straw was her misbehaviour at a royal premiere: “Princess Margaret had no time for Rex Harrison’s sloppy-looking, drunken, noisy wife,” said Roberts, putting herself in the third person. The Daily Telegraph Saturday 1 January 2022 ‘Totallb demented… stupendouslb drunk’: Welsh actress Rachel Roberts trbing an ice-cold shower in London, 1954 *** 11 Simon Heffer Hinterland Vaughan Williams wrote the theme music for his turbulent times. It’s time we recognised this titan Britain’s musical conscience: Ralph Vaughan Williams in Surreb, 1949 What are we to make of all this? First, Roberts was right to be indignant that, were she a man, her bad b e h av i o u r wo u l d h ave wo n applause, even admiration. It irked her she should be chastised as a nuisance and for not “obebing the rules of civilised behaviour. Yet Rex often doesn’t. Robert Shaw didn’t. Burton didn’t. O’Toole didn’t.” Verb true. Secondlb, Roberts is a warning about what can happen if bou become overdependent: “I didn’t make a life of mb own… I lived entirelb through him,” she said of Harrison. Ten bears after the divorce, she was still dreaming of a reconciliation: “I still love mb special, dbnamic, sillb, crustb, unbearable Rex.” Finallb, there is her Welshness – the chippb Celtic strain uneasb with Anglo-Saxon cool. Comparing her fate with that of Burton, Roberts said theb’d become “croppers in the ebes of the world” because theb’d wanted to impress; “insecure, cursed with feelings of inadequacb”. Despite manifest gifts and public recognition (Roberts won BAFTAs and was nominated for Oscars), “underneath, the uncertainties and the instabilities bubbled awab ”. There were other resemblances between Roberts and Burton, too. Dissipation, frabed nerves, adrift from one’s origins, an inabilitb to settle. The Welsh are supreme at being actors and actresses because flambobance is suppressed; it is the guiltb secret, which bursts out now and again in lunatic wabs, quick and fierce. There’s a sense of flight, dispersal, a splitting up of the emotions. Yet what is the alternative? To be respectful and drb? As Rachel Roberts said, “I still have emotional power, but it is locked up inside me, devastatinglb, eating me alive.” Born in Glamorganshire, I’m not dissimilar. s this the bear we finallb grasp the greatness of Ralph Vaughan Williams, born 150 bears ago? Because manb still don’t. The verb fact he was an English composer continues to count against him, but not, perhaps, for the same reason as when his centenarb was marked in 1972. Then, he was in the middle of a posthumous period of neglect (he had died in 1958) that seemed rooted not least in the critical belief that an Englishman – unless he were as cosmopolitan as Benjamin Britten – simplb could not write great music. Also, Vaughan Williams’s idiom was out of kilter with the prevailing vogue for atonalism, which Kathleen Ferrier famouslb dismissed as “three farts and a raspberrb, orchestrated”. Now, when it is fashionable for so-called intellectuals to suspect English culture because of what theb consider its implicit racism, Vaughan Williams suffers for that reason, too. He embodied white privilege: an upper-middle class, Oxbridge-educated, white heterosexual man with a private income, he is the antithesis of the diverse fantasb that so manb in the arts establishment, from the BBC downwards, strive to celebrate irrespective of anb consideration of merit. This blind prejudice diminishes too much of the achievement of a man who has, at last and despite everbthing, become – almost bb accident – one of the nation’s most popular composers. But in Vaughan Williams’s sesquicentenarb bear, it is time to strip awab all the prejudices, and indeed the somewhat superficial reasons for his growing popularitb – such as Classic FM’s championship of The Lark Ascending, which in truth is not among his most profound works – and to examine whb he is not merelb a great composer, but one of Britain’s greatest cultural figures, to rank with Shakespeare, or Milton, or Dickens, or Turner, or Constable, or Wren. The long-standing criticisms of Vaughan Williams range from the superficial to the ad hominem: that his music rarelb strabed bebond the influence of English folk song, and that therefore it doesn’t travel; that he didn’t innovate because he was innatelb conservative; and that he was some sort of Betjemanesque bumbling old toff who, as a result, need not be taken seriouslb. None of this equates with the realitb, which is that he wrote the turbulent theme music I for the turbulent decades through which he lived. He gave the bears from the 1900s to the 1950s the expression theb demanded; he captured emotions, ideas, currents and feelings, depicting them in his music more universallb than anbone else could. It is a matter of record that Vaughan Williams set out to write a “national music” and that he drew some of the inspiration to do so from his collecting and studb of English folk song in the decade before the Great War. Throughout his life the influence of folk song was apparent in some of his work – from the tunes he wrote for The English Hymnal in 1906, through The Lark Ascending in 1920, and the Five Variants of Dives and Lazarus in 1939. But folk song is supposedlb suffocating influence of English folk song. The percussive Piano Concerto and the ballet Job: A Masque for Dancing – both from 1930 – and his unprecedentedlb dissonant F Minor Sbmphonb of 1935 continued to reflect a sense of doubt and fear, and an absence of the cheerful optimism that characterised the composer’s earlb work. In the age of the great depression and the rise of Hitler, he struck an appropriate tone; and it became more so bb 1936 with the first performance of Dona Nobis Pacem, a cantata about the threat to peace being posed bb the rise of fascism. Bb the time war came again, he was the musical conscience of the nation, with a stature as a public figure unknown among British composers todab. Throughout that war, and after it, he articulated the feelings of the people for whom he wrote, not just through his radicallb contrasting Fifth and Sixth sbmphonies, but finding a whole new audience through his film music – not least his score for Ealing’s 1948 epic Scott of the Antarctic, about another dimension of British endeavour. But this musical achievement was not the component of Vaughan Williams’s moral greatness as an artist. His success, following on from Elgar’s, finallb put British music on the map He was out of kilter with the vogue for ‘three farts and a raspberry’ atonalism even apparent in his film music from the 1940s, such as his score for Powell and Pressburger’s 49th Parallel; and it appears, brieflb and bb wab of stark contrast, in one of the works that labs claim to be his masterpiece, the violent, disorientating and overwhelming Sixth Sbmphonb. And that brings us to the point about Vaughan Williams: he was an innovator, an experimenter, a man who absorbed the currents of what was going on around him and expressed it in his writing. Before the Great War he projected the then hugelb pervasive influence of Walt Whitman in his A Sea Symphony and his choral work Toward the Unknown Region; he embraced the interest in Tudor polbphonb in the Tallis Fantasia and his own experience as a man living and working in London in his London Sbmphonb – or as he called it, his “Sbmphonb bb a Londoner”. But then the war changed everbthing. His Pastoral Sbmphonb, caricatured as “VW rolling over and over in a ploughed field on a muddb dab” was in fact about the landscape, and the trauma, of the Western Front. His oratorio Sancta Civitas, finished in 1925, had a darkness that infused much of his music in the inter-war bears and owed nothing to the ROLLS PRESS/POPPERFOTO VIA GETTY IMAGES Theb separated in December 1969, and Roberts went off her rocker. She started to swallow overdoses and was regularlb having her stomach pumped. “I want to f---ing kill him,” she said of Harrison to a doctor at the Cedars of Lebanon Hospital. When her agent Aaron Frosch sent a basket of cheese, she threw it out of the window, sabing the gift was “vulgar and pretentious”. Roberts went on Russell Hartb’s chat show, called the host “a sillb c---” and said of her cats, “all theb want to do is screw”. Hartb’s other guests, Sir Peter Hall, Elton John and Barbara Cartland, fell into an embarrassed silence. internationallb, with America especiallb devouring his work. Both through the example of his own music and through his teaching at the Robal College of Music, he nurtured the composers of the English musical renaissance – including Herbert Howells, Arthur Bliss, Jack Moeran, Gerald Finzi, Ruth Gipps and Stanleb Bate. He set an example, too, of wider amateur participation in music, leading the Leith Hill festival in Surreb with choirs from the neighbouring villages. He was one of those engaged in founding what became the Arts Council, and broadcast on radio and on film about the importance of music and of cultural life. His mission was not merelb to write great works – which he unquestionablb did – but to advance civilisation, not just in Britain but wherever his music his plabed. He was a great Englishman, but also a great cultural figure who is increasinglb appreciated internationallb. The emphasis on the commemoration of Ralph Vaughan Williams this bear should be about the moral greatness that comes from such a commitment to art, and not just about the jollb tunes of his theb plab on Classic FM. Go out and listen to his music – and not just the obvious, popular favourites – and bou will begin to see dimensions to this titan bou had not thought existed. 12 Saturday 1 January 2022 The Daily Telegraph *** Books So fresh! Our pick of 2022’s brightest new novelists Whether it’s an unlertaker’s BDSM alventures or a family cursel to fall out of winlows, the season’s best lebuts are full of surprises S Lewis’s adage that we read to know we are not alone may have become a banal observation, but being inside a character’s interior struggles while they navigate personal crises with all their human flaws is one of the novel’s perpetual strengths. Four of the new year’s most accomplished debut novelists, Sara Freeman, Renée Branum, Ella Baxter and Jakob Guanzon, take us back to this elemental function of literature. Poverty, grief, family ties, lack of self-knowledge – their heroes variously face them all. That our sympathies are engaged so skilfully and hope so adeptly snatched from the jaws of defeat is proof of the strength of these new writers’ storytelling, and the sincerity of their enterprise: chipping away at the truth of how people are, how they behave and what they feel. Australian artist and writer Ella Baxter has admitted to being in a “valley of grief ” when she wrote New Animal (Picador, £14.99), in which Aurelia, a young funeral parlour cosmetician in New South Wales, hurls herself into the shame and tawdry exploitation of the BDSM scene after her mother dies. Baxter is fascinated with the female body, which “trots everywhere with you like an indebted lover”, and how it assimilates extreme emotions. Aurelia investigates, through often savage humiliations, how far she can use sex as a violent displacement activity. Self-destructive anti-heroines are in vogue, but what Aurelia’s story makes clear is how underrepresented female sexuality still is. A key scene in which Aurelia first tries out the position of a “dom”, C rather than a “sub”, is a direct challenge to the reader’s conception of what is admissible sexual behaviour for a woman – even more so as it is partly played for laughs. By the end, Aurelia counter-intuitively finds a renewed bond with her body after placing it under duress. The novel closes with her preparing a stillborn baby girl for a funeral, prompting a reflection on the power of the female body, with its almost infinite capability to reabsorb pain, “like a mechanical ocean recycling its own salt”. A stillborn child also lies at the centre of Canadian writer Sara Freeman’s Tides (Granta, £12.99), in which 37-year-old Mara flees to a New England coastal town in the wake of losing her baby. While her behaviour is in no way as extreme as the protagonist of New Animal, her plight feels more precarious. With little money, she lives as an itinerant before getting a job in a local wine store and embarking on an affair with its owner. The seaside town for Mara feels less like a place of possible renewal, a fresh tide, than a pull toward death, where after losing a child “you go along with her”. “You won’t be happy until you’ve burned the whole house down,” she recalls a friend telling her. Is redemption even a possibility? Here, as in New Animal, deliverance is far from guaranteed. If Freeman lacks Baxter’s leavening humour, she makes up for it with a honed lyricism: “When she pictures it – herself in this town forever – it reminds her of a silent movie she once saw in which a man, shot dead on a sidewalk, steps out of the outline the police chalked, looks down at his own figure, then, From Churchill to Sir Mix-a-Lot Time to retire your oll ‘Dictionary of Quotations’ – this new volume busts myths about who sail what By Jonathon GREEN satisfied with the line, settles back down, closes his eyes, dies all over again.” Mara’s brush with near-destitution in 21st-century America pales in comparison with the privations faced by the hero of Filipino-American writer Jakob Guanzon’s Abundanc e ( Dialog ue, £14. 99). A single-father ex-convict, Henry is living with his eight-year-old son in his pickup in the Midwest, after being evicted from their home on New Year’s Eve. We learn in flashbacks how his life has unravelled; each chapter tells us exactly how much he has in his pocket. In such dire straits, can he function as a father? Guanzon carefully builds a portrait of a character with at least one tragic flaw, searching for dignity and clarity. The honest and tender scenes with his son form the novel’s heart and soul, but it is also ignited by tense crime-novel confrontations and some brilliantly sustained descriptions of down-at-heel discount America. In a Walmart, “None of them walk. They trudge and shuffle down the main lane, as if their rickety shopping cart wheels were propelled by some hidden motor that was actually towing them along, like a tractor hauling off a felled rodeo steer”. Whereas in Abundance a fatherson bond is the pathway for salvation, in Cincinnati-based writer Renée Branum’s Defenestrate (Jonathan Cape, £14.99) the relationship between a twin sister and brother is a Gordian knot of selfhindering, stagnation and denial. Co-dependent and regressed, THE NEW YALE BOOK OF QUOTATIONS ed Fred R Shapiro 1138pp, Yale, T £30 (0844 871 1514), RRP £35, ebook £35 Quotations collections were simpler once: there was Oxford for home consumption, and for a change, Bartlett, closely pursued by Brewer, across the pond. There were others, of course (the evercaustic US essayist HL Mencken came up with an enjoyably tart example), but, in every sense, that trio of hardbacked, multi-paged offerings provided the go-to heavyweights. Like Samuel Johnson ( good for 110 quotes here), who These writers all chip away at the truth of how people are, anl what they feel chose only the “best writers” to provide his dictionary’s usage examples, such were the foundations of these long-established tomes. You were on predictable, solid (but also stolid) ground with each. The workhorses did their job, growing ever-more tattered, ever less contem porary, but no matter. They gave and you were happy to receive. If one is not careful, the quote is the cracker motto of the intellectual classes. Easy come, easy know. The problem, it transpires, is that (all too) often you were self-deluded. R e s e a rc h w a s f a r h a rd e r i n pre-internet days, and defaults were sometimes embraced: if in doubt, attribute the errant mot to Churchill. Failing him, Wilde or maybe, tipping a grudging hat to gender parity, Dorothy Parker. If it began with “Sir…” then give 20-somethings Nick and Marta move to Prague from the Midwest to indulge their obsession with their family’s “falling curse”, said to be traceable back to Czech ancestors. The jinx dooms the bloodline to lose their footing at some point. It is an original conceit, with an idiosyncratic humour that reminded me of Ottessa Moshfegh. Nick and Marta’s shared hero is Buster Keaton, king of the pratfall, and there are some wonderful digressions about that comic genius that shouldn’t really work, but do. When Nick takes a serious fall from his apartment balcony, Marta begins to wonder: was it attempted suicide? Branum cleverly suggests how Marta’s preoccupation with this nagging conundrum allows her to avoid confronting her own demons. Branum’s primary fascination is with the binds of family and the dread of autonomy, but her gaze is wider and more mystical, as when she considers the siblings’ mother’s Catholicism: “My mother sees, in the fall of the apple from the mouths of the first of us, a great need opening up through centuries until Christ reversed the arc of the fall with his body… It is strange that we try to keep ourselves safe in the light of this, to dare survival when God himself could not keep himself alive in our midst.” If a single theme unites these books, it is about finding a way of coming face to face with what Tides calls “the dark possibility of the road”. Or, as Henry puts it, at the close of Abundance, “It was his job to keep looking forward, to keep looking up”, despite “the dread or anticipation of the sprawling freedom that was closing in on them”. But me no butts: rapper Sir Mix-a-Lot is in The New Yale Book of Quotations ILLUSTRATION: RUBY MARTIN FOR THE TELEGRAPH By Alasdair LEES The Daily Telegraph Saturday 1 January 2022 *** 13 To order any of these books from the Telegraph, visit books.telegraph.co.uk or call 0844 871 1514 it to the Great Cham. Like popular etymology, this was a mistake. In 2006, Fred Shapiro of the Yale Law Library (and a leading OED contributor) brought out the fruit of nine years’ research: The Yale Book of Quotations. Using the level of research that the internet had made accessible, and aiming for the kind of bibliographical and chronological exactitude that Oxford demands of its lexicographers, he took a new look at the field. And in so doing brought the old stagers up to date. His collection acknowledged much of the monochrome trustworthiness of the classical canon, but added the sometimes lurid colour of modernity, and even moved to embrace the CGI specialities of the digital world. This, the revised and expanded second edition, carries on as before. If the book has a USP, it is reattribution, not least in the section “Anonymous Was a Woman”, a paraphrase of Virginia Woolf who opined that, “Anon, who wrote so many poems without signing them, was often a woman.” So, inter alia, Voltaire loses his best-known saying to Evelyn Beatrice Hall, Hemingway his to Mary Colum and, perhaps most revelatory of all, Churchill hands over “iron curtain” to Ethel Snowden. Shapiro has spread a wide net. Some familiar names are missing, but the stars of the baby-show have resisted eviction with the bathwater. On the cover, he namechecks Plato, Shakespeare, Isaac Newton and Mark Twain, though we should note also Alicia Garza, who came up with “black lives matter”. Within, things are broader- Shapiro reassigns Churchill’s famous ‘iron curtain’ line to Ethel Snowden brush. Henry Fielding (Tom Jones) gets his entries, but so does Helen, of Bridget Jones renown. Galen, the Greek physician, has his line, next door to Tony “Two Ton” Galento, the prizefighter. Eric Partridge, my predecessor as a slang lexicographer, has a walk-on. The second edition adds Warren Buffett, Steve Jobs, Barack Obama and David Foster Wallace to the thousands of voices. Readers will have their favourites; rapper Sir Mix-a-Lot’s celebration of “big butts” may not appeal to all. Quotation (Johnson again) “is a good thing: there is a community of mind in it”. Once, undoubtedly, true; but Shapiro’s book, with its infinitely wider embrace than Johnson would have permitted, may be less soothing. Perhaps the problem will not simply be who gets to be quoted – there is one bear of nugatory brain here, whom I for one would have excluded with joy – but the choice of lines. Shapiro has the right to impose his own tastes. But then this is a book, and only so many pages can be bound; the limits of physical space are something else that digitisation has abolished. The Oxford Dictionary of Quotations was my first reference book, a birthday gift in 1959. If we emphasise the term “book”, then I suspect that Shapiro’s fine compilation may be my last. One only need look at the disappearance of once-mighty reference publishers, the everthinner “reference” shelves in the equally diminished world of bookshops, to see that print reference is another victim of digital modernity. For once, however, I cannot grieve. (I’m parti pris: my own Dictionary of Slang last demanded dead trees in 2010; since then it has been online, and infinitely improved for it). Yet as the essayist Louis Menand, writing the foreword, notes, this is “a fun book to browse” – and browsing, the flipping of pages, the pursuit of something that catches the eye, requires a tangible object. It is also, he adds, a fun book for scholarship, the reverse of the reference coin. Wit and wisdom: what else, readers, could we need? 14 Saturday 1 January 2022 The Daily Telegraph *** White guilt – the paradox This historian calls for an honest look at British slavery, but fails to deliver it By James WALTON WHITE DEBT by Thomas Harding 320pp, W&N, T £16.99 (0844 871 1514), RRP £20, ebook £11.99 ART BOOKS FACE TI M E TOM HUNTER In a comedy sketch by Mitchell and Webb, one SS man turns to another and asks in a tone of troubled bewilderment, “Are we the baddies?” Now with White Debt, Thomas Harding sets out to make British readers ask much the same question in much the same tone. Near the beginning, Harding – who has a degree in political science from Cambridge – claims he “had no idea that British people… ran slave plantations in the Caribbean”. Moreover, all the white Brits he’s ever known, including himself, have “tut-tutted” about the evils of slavery in the American South, before “in the next breath we proudly talked about the British Empire and all that we had accomplished”. If he’d been born in 1868 rather than 1968, these claims might perhaps have been plausible. As things stand, they’re an early sign of the book’s main flaw. Having found a story of British iniquity that really has been largely forgotten – and telling it with some aplomb – he can’t resist such unhelpful journalistic add-ons as exaggeration to the point of caricature, an over-concern with his own reactions, and the kind of editorialising that leaves the reader with badly bruised ribs. The story in question took place in the British colony of Demerara (now Guyana) in 1823. The Atlantic slave trade had been abolished 16 years before, but slavery itself continued as cruelly as ever – although not with the approval of all the colonists. To the disgust of many sugar-plantation owners, the local missionary John Smith taught his black congregants to read – and even went so far as to suggest that ferocious beatings for the smallest of misdemeanours might not be entirely in accordance with God’s will. Among Smith’s literate congregants was Jack Gladstone, son of an enslaved mother and thus enslaved himself since birth. Believing that full emancipation couldn’t be long in coming, Jack sought to accelerate the process by organising an uprising of around 12,000 people, making it the biggest ever in a British colony. As uprisings go, it was impressively non-violent, with plantation owners and overseers put in stocks, but otherwise left unharmed. Portraits that refer to paintings have a long tradition in the history of photography. Here, Tom Hunter’s 1997 picture, Woman Reading a Possession Order, echoes Vermeer’s Girl Reading a Letter at an Open Window of 1657. The image features in Face Time, a journey through the history of photographic portraiture by Philip Prodger, the former head of photographs at the National Portrait Gallery. Thames & Hudson, £30 Nonetheless, instead of agreeing to the hoped-for negotiations, the governor of Demerara declared martial law, gathered a militia and carried out a series of murderous reprisals culminating in the massacre of more than 200 “enslaved abolitionists”, as Harding characteristically prefers to call them. Jack went on the run, but was arrested and put on trial for his life. Not long afterwards, so too was John Smith, charged with helping to incite the rebellion. Neither trial, it’s fair to say, was a just one. Yet, because Harding lays out what hap- Is it really true that ‘little has changed in the Caribbean since the time of slavery’? pened with such novelistic, pageturning ( but still assiduously researched) flair, it would feel like a spoiler to reveal any more than that. The continuing trouble, though, is that Harding doesn’t leave it there. His previous books of history have drawn on his own family’s past in a successful bid for emotional resonance. Hanns and Rudolf, for example, vividly described how the commandant of Auschwitz was tracked down by the Jewish Nazi hunter Hanns Alexander – who was Harding’s great-uncle. Legacy, his history of the Lyons food business, benefited greatly from the fact that his family had owned it. Here, however, the family connections feel distinctly tenuous, and at times rather desperate. “In the 1920s,” he confesses, “my family ran the Trocadero in central London”, where the entertainment included “a dance troupe who put on blackface”. Not only that, but one of Lyons’ “marketing cam- paigns for cocoa used racist caricatures of Africans”, and his grandad was a friend of Enoch Powell’s. “Writing about all this,” he assures us, “makes me deeply uncomfortable. There’s also shame.” Harding’s personal sense of shame runs throughout White Debt – even after one activist tells him that when white people talk about slavery, “it shouldn’t be all about ‘me and my White guilt’”. But, you can’t help wondering, has he really earned it? In fact, one way of reading White Debt is as an inadvertent warning against the dangers of excessive hand-wringing. Harding gets himself into a right old tangle as he tries both to speak for black people and not to be so racist as to speak for black people. There’s also a pronounced nervousness about causing offence that leads him to banish the N-word even when quoting from contemporary documents – despite it being a more authentic reflection of the racism involved; and to accept without question whatever black activists tell him. (According to one, “little has changed in the Caribbean since the time of slavery”: an assertion that feels somewhere between highly dubious and quite insulting.) More damagingly, this nervousness infects the main story. Might it be that he is so determined to show that enslaved people did more to win emancipation than any white abolitionists that he ends up overstating the role of the uprising? Harding is obviously sincere, as well as justified, in calling for an honest discussion of the whole business of slavery and its aftereffects. Even so, the awkward feeling persists that White Debt is melancholy proof that, for the most well-meaning of reasons, such honesty is now pretty much politically impossible. Or, more melancholy still, that this impossibility is one of the after-effects that might never go away. The Daily Telegraph Saturday 1 January 2022 *** To order any of these books from the Telegraph, visit books.telegraph.co.uk or call 0844 871 1514 ‘Humankind cannot bear very much reality’ If you seek consolation in deep midwinter, try this collection of 17 authors who all stared into the abyss – and emerged stronger By Rupert CHRISTIANSEN ON CONSOLATION by Michael Ignatieff 304pp, Picador, T £14.99 (0844 871 1514), RRP £16.99, ebook £8.99 In anxious and uncertain times, we have all been searching for consolation. “Humankind cannot bear very much reality ” as TS Eliot sharply reminded us: we tend to look away and take the easiest way out. My own response to the pandemic – typical enough, I guess – has demonstrated this shying away. Through the darkest days of the lockdowns, what has kept me going has been less the headlines about hopeful vaccines or the tales of NHS heroics than the more transient comfort I have found in commonplace small things: a limp pot plant suddenly flowering on the terrace, the good-natured ebullience of Schitt’s Creek, my evening schooner of cold dry sherry. But after reading Michael Ignatieff ’s new book, I feel almost ashamed of myself: I’m nothing but a first-world snowflake, grasping at straws and failing to think about life hard enough. What Ignatieff offers is something sterner: 17 brief biographical essays on men and women who, in the course of more than two millennia of Western civilisation, have looked the deepest horrors, agonies and deprivations in the face and found philosophical poise – a reason for it all, an inner calm, a reckoning with death. The result is something wise, truthful, and kindly but, oh dear, perhaps as alarming and depressing as it is consoling. This unintended effect stems from an intense and unremitting seriousness of tone: Ignatieff writes with such lucid intelligence, but his honourable high-mindedness doesn’t lighten up, leaving him immune to the solace of laughter, humour, comedy, the sense that perhaps none of it matters much anyway. So just be warned: P G Wodehouse doesn’t get a look-in, and there are no jokes and few smiles here. In other respects, Ignatieff covers a wide variety of positions, from Job and his false comforters to the saintly founder of the hospice movement Dame Cicely Saunders. The Pauline epistles conjure up promises of a Second Coming and paradise A profound reflection on consolation: why did Ignatieff omit CS Lewis, pictured in 1950? on the other side of earthly suffering; Cicero’s stoicism is tested by both the death of his daughter and the collapse of the Roman republic; Marcus Aurelius meditates on life as a tale told by an idiot, full of sound and fury signifying nothing. Awaiting execution in prison, Boethius decides that we are all simply victims of the wheel of fortune, and that human agency is helpless in the face of its wanton spinning. God might be watching, but he’s not going to intervene. More than a thousand years later, Nicolas de Condorcet and Karl Marx nurse optimistic Enlightenment beliefs in social progress and a potential amelioration in human behaviour that the violence of the French and Russian revolutions would decisively crush. In Auschwitz, Primo Levi bravely clings to the exhortation of Dante’s Ulysses to his beleaguered crew that “you were not born to live your life as brutes/ But to be followers of virtue and knowledge”. Michel de Montaigne and David Hume take the middle road and seem the most immediately helpful guides. Montaigne discards the consolations of philosophy and finds solace instead in the pleasures, rhythms and resilience of the human body itself. Despite the pain of his kidney stones, he finds life to be worth living “simply because you could feel its rhythms coursing through your veins”. Hume follows him: a man can sit and think too much. “I dine, I play a game of backgammon, I converse and make merry with my friends. And when after three or four hours amusement, I wou’d return to these speculations, they appear so cold, and strain’d, and ridiculous, that I cannot find in my heart to enter into them any further.” That sounds more like it to me. A book like this will always provoke its readers to add or subtract their own candidates for inclusion or exclusion. I wasn’t quite persuaded that the cases of the sociologist Max Weber and the playwright-politician Václav Havel belong here, but most of all I regret the omission of CS Lewis, whose essay “A Grief Observed” – in which he finds some Christian passage out of despair over his wife’s death from leukaemia in the injunction to be still and accept that we don’t understand – is one of the most profound reflections on consolation that I know. 15 16 Saturday 1 January 2022 The Daily Telegraph *** Books Power in the wrong hands… From dictators all the way down to janitors, a fun psychological study shows how authority corrupts CORRUPTIBLE by Brian Klaas 320pp, John Murray, T £16.99 (0844 871 1514), RRP £20, ebook £9.99 In his mundane job as a New York school maintenance sup er vi s or, Steve Raucci earned the unlikely title of “the Don Corleone of janitors”. Told he could get a promotion if he cut his school’s electricity bills, he saved millions of dollars by keeping classrooms freezing cold in winter. Shivering teachers who brought their own portable heaters in from home would find the power cables mysteriously cut. A photo of Marlon Brando in The Godfather even hung in Raucci’s office. In the best tradition of villainous janitors in ScoobyDoo, Raucci might have gotten away with it too, had meddling colleagues not complained to management. In revenge, he planted home-made bombs in their cars, earning himself a 23-year prison sentence in 2010. Hollywood is now planning a screen version of this tale of smalltime tyranny, which sounds similar to zoo boss Joe Exotic’s murderous schemes in the Netflix series Tiger King. But in Brian Klaas’s book, Corruptible, it’s just one of many stories about the dangers of power – be it in the hands of ruthless dictators, David Brent-style bosses, or the “Read the Standing Orders!” bullies at Handforth Parish Council. “Why are so many of these people dreadful?” Klaas asks. And more importantly: “How can we spot them – and ensure they don’t become our leaders?” On paper, Klaas is well qualified to tackle this question. A professor of global politics at University College London, he has interviewed everyone from presidents and cult leaders through to rebel commanders and criminals. He can also trot out endless weird and wonderful insights from behavioural studies, be it about hunter-gatherer tribes, ruthless CEOs, or the animal kingdom (typical sentence: “Psychopaths have much in common with dark-footed ant spiders.”) However, one challenge with a book like this, of course, is that dictators are a challenging study group. For a start, there are only a few around. Plus, the likes of Kim Jong-un don’t often do Oprah-style sit-downs, telling “their truth” about why they murder folk. Instead, Klaas has to make educated guesses, drawing on examples lower down the global pecking order, such as corrupt cops and ruthless CEOs. Psychopaths, he says, are actually far more common in boardrooms and parliaments than in the population at large. The reason we don’t notice is that they’re successful – unsuccessful psycho- NETFLIX US/AFP VIA GETTY IMAGES By Colin FREEMAN Small-time tyranny: zookeeper Joe Exotic in Netflix’s hit Tiger King paths, by contrast, end up in jail. Lest we be too judgemental, though, Klaas reminds us that our rulers have to make choices the rest of us don’t. He interviews ex-Thai prime minister Abhisit Vejjajiva, a man some regard as a mass murderer because his troops shot dead 87 protesters who stormed the parliament in 2010. Vejjajiva, an Old Etonian, explains in plummy tones that he had to show a firm hand: the protests, he believed, could otherwise have sparked a far bloodier civil war. “It’s easy to say Vejjajiva is a brutal murderer,” Klaas observes. “It’s harder to say how you would’ve acted if you were in the seat of power and the lives of thousands of people were placed on your shoulders.” This is a valid point – and one Western leaders might want to bear in mind when criticising their counterparts in the world’s tougher neighbourhoods. However, having spent time dictator-watching myself – it’s part of the beat as a Telegraph foreign correspondent – I’m not sure Klaas really addresses why some behave as they do. He doesn’t grapple with complex cases like president Assad of Syria, for example, once tipped as one of the Middle East’s more reform-minded rulers. He’s now a war criminal for turning Syria into a bloodbath, yet it’s debatable whether he acted purely for his own personal survival. Many would argue he was pushed into it by his wider clan, and by Russia and Iran, Syria’s military sponsors. In similar fashion, corruption in Third World governments isn’t always down to a leader’s personal venality, but the expectations of their particular ethnic group that it is their “turn to eat”. A president who fights that expectation may get plaudits from the World Bank, but will alienate their own base. The closest Klaas gets to meeting a real dictator is interviewing Marie-France Bokassa, one of the 57 children of emperor Jean-Bédel Bokassa, who ruled the Central African Republic from 1966 to 1979. A tyrant from central casting, Bokassa fed his enemies to crocodiles, and was said to eat their bodies himself. His daughter says Dad was nice at times, but “authoritarian” and quick-tempered. Surely that’s true of nearly every oldschool patriarch. Besides, don’t our rulers need some inner steel? When Jeremy Corbyn prevaricated on Question Time over whether he would ever press the nuclear button, he was heckled. Klaas does concede certain limitations in this book. Too much psychological research, he says, is based on studies done on posh Ivy League psychology undergrads, who are hardly representative of the wider world, let alone tyrants. But that doesn’t stop him quoting such research – and studies involving other species. In 300 pages, I come across references to lemurs, springboks, macaques who’d been fed cocaine, and, of course, meerkats (is there a single meerkat pack that doesn’t have a team of Harvard psychologists analysing them?). Still, Klaas writes entertainingly, and while this book may not be the last word on how to stop future Putins (or Trumps), it’s a fun guide to the darker recesses of the political mind. And, no, he hasn’t bribed me to say that... The Daily Telegraph Saturday 1 January 2022 *** To order any of these books from the Telegraph, visit books.telegraph.co.uk or call 0844 871 1514 17 PAPERBACKS READ THIS WEEK America in the 1890s, 1990s and 2090s The ‘A Little Life’ author returns with an awe-inspiring novel that takes speculative fiction to a new level By Lucy SCHOLES NO ONE IS TALKING ABOUT THIS by Patricia Lockwood 224pp, Bloomsbury, £8.99 Written in short, tweet-like paragraphs, Lockwood’s brilliant, Booker-shortlisted novel begins as a very funny satire about the internet, before taking a dark turn. TO PARADISE by Hanya Yanagihara 720pp, Picador, T £16.99 (0844 871 1514), RRP £20, ebook £9.99 About a third of the way through Hanya Yanagihara’s awe-inspiring new novel, the narrator of the section in question – a Hawaiian boy directly descended from the island’s royal family – has the significance of his lineage impressed upon him. As Hawaii becomes the 50th American state, his mother impresses upon him: “This doesn’t change anything, you know, Kawika. Your father should still be king. And someday, you should still be king, too. Remember that.” Kawika is struck by the peculiarity of her syntax: the “strange mix of tenses, a sentence of promises and grievances, reassurances and consolations”. To Paradise itself might be best described thus. It too deals in multiple tenses: an America that could have been, one close to the world we know, and one that could still come into being. The novel is split into three “books”. Each exists in its own bubble, but a Washington Square townhouse in New York’s Greenwich Village takes centre stage in all three. Meanwhile, characters share names and traits, and themes and motifs re-emerge: illness and disability; absentee parents; the sometimes terrible, sometimes extraordinary lengths we’ll go to in order to protect those we love; the question of what separates life from mere existence; and our desire to believe in the possibility of creating a better world, even if better for some is never better for all. Opening with a counterfactual version of the late 19th century – in which New York is one of eight Free States where same-sex marriage is legal, and (white) women have the same rights as (white) men – we’re then transported to 1990s Manhattan, where AIDS is the ominous backdrop to what’s otherwise a world of enviable privilege. Finally, the novel draws to a close with an unnerving portrait of New York at the end of the 21st century. Ravaged by increasingly deadly pandemics and climate change, its surviving citizens live under draconian state surveillance. “Zone Eight ”, this final section, might cut a little Breathtaking feat of world-building: Hanya Yanagihara New York at the close of the 21st century is a ravaged, draconian surveillance state too close to the bone for some, but Yanagihara has always leant fearlessly into what horrifies, disgusts and terrifies us. Critics of her Booker Prize-shortlisted debut A Little Life likened its graphic depiction of child abuse and self-harm to trauma porn. “Zone Eight” induces its own visceral reaction: a cold sense of dread crept up my spine, yet the characters are so well drawn and the plot so well paced, I couldn’t put it down. The relentlessness of A Little Life was magnificent. The way it drilled so deeply, again and again, into the suffering of its central character was a virtuosic imitation of what it’s like to be trapped in the never-ending cycles of abuse and trauma. Yanagi- hara’s reach here is different – broader and more diffuse. She’s concerned with the universal as much as the specific, and the ramifications that the choices individuals make have on the society around them. Although perhaps not as ruthlessly immersive as A Little Life, nevertheless the world-building on display here is nothing short of breath-taking. Yanagihara proves herself equally skilled at reproducing the rich textures of an Edith Wharton novel as she is at invoking an alarmingly believable dystopia. If there’s a slightly weaker link, it’s the lengthy middle book – untethered from the ballast of Washington Square, the story told here in Hawaii drifts – but I’m nit-picking. There’s a moment towards the end of the first book when David – scion of a blue-blooded New York family, who has fallen in love with a penniless piano teacher – is poleaxed by a letter that exposes his lover’s chequered past. “It was as if he had experienced the story rather than read it,” Yanagihara writes. To Paradise feels exactly like this. In the same way that the failed utopian projects described therein aren’t for everyone, this is a novel that won’t please all readers. But whether you find it beautiful or terrifying, read it as a story of fear and despair or one of solace and hope, one thing is impossible to deny: Yanagihara has taken speculative fiction to a whole new level. CONCLUSIONS by John Boorman 256pp, Faber, £10.99 “I have spent more time on films I have not made than on the ones I have,” writes the 88-year-old director of Point Blank and Excalibur, reflecting on his career in a memoir that’s funny and philosophical by turns. ACTS OF DESPERATION by Megan Nolan 304pp, Vintage, £8.99 A young woman living in Dublin looks back on a dysfunctional relationship that scarred her early 20s in Nolan’s intelligent, elegant first novel, a gripping portrait of love turned toxic.