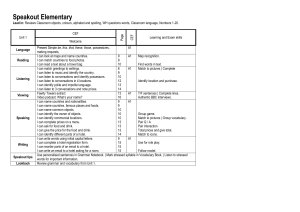

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/254307494 Keeping It “REAL” with Authentic Assessment Article in NHSA Dialog A Research-to-Practice Journal for the Early Intervention Field · January 2010 DOI: 10.1080/15240750903458105 CITATIONS READS 33 1,257 2 authors: Marisa Macy Stephen Bagnato University of Nebraska at Kearney University of Pittsburgh 58 PUBLICATIONS 508 CITATIONS 108 PUBLICATIONS 1,910 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects: Infant Mental Health--Early Regulatory Disorders Assessment View project Innovative Disabilities Interventions for Rural & Urban Contexts View project All content following this page was uploaded by Stephen Bagnato on 12 August 2014. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. SEE PROFILE This article was downloaded by: [Macy, Marisa] On: 15 January 2010 Access details: Access Details: [subscription number 918633748] Publisher Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 3741 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK NHSA Dialog Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.informaworld.com/smpp/title~content=t775653686 Keeping It “R-E-A-L” with Authentic Assessment Marisa Macy a; Stephen J. Bagnato b a Department of Education, Lycoming College, b Departments of Pediatrics and Psychology-inEducation, University of Pittsburgh Medical Center (UPMC), Online publication date: 15 January 2010 To cite this Article Macy, Marisa and Bagnato, Stephen J.(2010) 'Keeping It “R-E-A-L” with Authentic Assessment', NHSA Dialog, 13: 1, 1 — 20 To link to this Article: DOI: 10.1080/15240750903458105 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/15240750903458105 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.informaworld.com/terms-and-conditions-of-access.pdf This article may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae and drug doses should be independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material. NHSA DIALOG, 13(1), 1–20 C 2010, National Head Start Association Copyright ISSN: 1524-0754 print / 1930-9325 online DOI: 10.1080/15240750903458105 RESEARCH ARTICLES Keeping It “R-E-A-L” with Authentic Assessment Marisa Macy Downloaded By: [Macy, Marisa] At: 23:06 15 January 2010 Lycoming College, Department of Education Stephen J. Bagnato University of Pittsburgh Medical Center (UPMC), Departments of Pediatrics and Psychology-in-Education The inclusion of young children with disabilities has remained a function of the Head Start program since its inception in the 1960s when the United States Congress mandated that children with disabilities comprise 10% of the Head Start enrollment (Zigler & Styfco, 2000). Standardized, normreferenced tests used to identify children with delays are problematic because (a) they have low treatment validity, (b) they are not universally designed or adaptable, (c) it is difficult to capture the real life behaviors/skills of young children, (d) they do little to facilitate collaboration with parents, (e) they lack sensitivity to changes in the child’s development and learning, and (f) children with disabilities are often excluded from group data. This study examined the use of an alternative approach that uses early childhood authentic assessment to determine a young child’s eligibility for special services. Results of this study have implications for adopting authentic assessment practices. Keywords: developmental delay, systems integration The inclusion of young children with disabilities has remained a function of the Head Start program since its inception in the 1960s. The United States Congress mandated that children with disabilities comprise 10% of the Head Start enrollment (Zigler & Styfco, 2000). Informal and formal types of assessment practices are used to determine children who are eligible for specialized services (Bagnato, 2007; McLean, Bailey, & Wolery, 2004; National Association of School Psychologists, 2005; National Research Council, 2008). Informally, Head Start professionals observe children on an ongoing basis as children participate in their early childhood programs. Professionals note when children’s behavior and skills deviate from developmental expectations. Parents and caregivers also contribute to understanding a young child’s development. Home visits and other opportunities for collaboration allow Head Start programs to gather a holistic picture of children. Correspondence should be addressed to Marisa Macy, Lycoming College, Department of Education, 700 College Place, Williamsport, PA 17701. E-mail: [email protected] Downloaded By: [Macy, Marisa] At: 23:06 15 January 2010 2 MACY AND BAGNATO Formally, professionals may incorporate the use of tools to screen children for delays in development and learning. An individual assessment may occur if a child’s academic or developmental performance is suspicious to a professional and parent, or a group of children may be screened. The Individuals with Disabilities Education Improvement Act of 2004 (IDEA) requires the implementation of child-find efforts in order to locate young children who are eligible for services due to delay or risk conditions. Screening tools offer a snapshot and are not comprehensive enough to determine eligibility for IDEA services. Eligibility assessments are used when enough data are collected to warrant an in-depth look at a child’s development. Standardized, norm-referenced tests are the most widely used tools to determine whether a child is eligible for IDEA services. This practice is a result of the fact that standardized, norm-referenced tests often contain standard scores that are required under many state guidelines (Danaher, 2005; Shakelford, 2006). Standard deviation and percentage delay are frequently used in order to identify the eligible population of young children; however, several states make use of informed clinical opinion, which promotes more flexibility for children, their families, and professionals (Bagnato, McKeating-Esterle, Fevola, Bartalomasi, & Neisworth, 2008; Bagnato, Smith-Jones, Matesa, & McKeating-Esterle, 2006; Dunst & Hamby, 2004; Shakelford, 2002). Informed clinical opinion, or clinical judgment, is often used by professionals to understand a child’s special needs without having to administer formal tests to a child (Bagnato et al., 2006). It is not unreasonable to assume that standardized, norm-referenced tests have been proven to be reliable and valid. These tests have been in existence for several years and have widespread use among professionals who believe them to have strong psychometric properties. A recent research synthesis examined the use of standardized, norm-referenced tests and established that few if any of these tests are effective in determining eligibility for IDEA special services for young children with disabilities (Bagnato, Macy, Salaway, & Lehman, 2007). In addition to weak evidence supporting use of standardized, norm-referenced tests to identify eligible young children with delays, the study (Bagnato et al., 2007) also pointed out several flaws with using these tests for eligibility determination. First, most of the standardized, normreferenced tests examined in Bagnato et al.’s (2007) study did not include children with disabilities in the standardization process. In addition, all of the standardized, norm-referenced tests lacked item density and procedural flexibility, which are salient elements to assessing young children with delays. The standardized, norm-referenced tests were also deficient in offering graduated scoring options. Another concern with using standardized, norm-referenced tests for eligibility determination is that they do not inform treatment efforts or instruction. These tests can show the extent a child’s behavior or skill is different from the norm, but they do not lay a foundation for the next steps in helping the child reach his or her potential or supports she or he will need to be fully included in a Head Start classroom. Differentiating children’s performances on a test is the main focus of standardized, norm-referenced tests, not necessarily what will occur after the test is over. One of the basic tenets of IDEA is that assessment practices must be fair and nonbiased. Court cases have challenged the use of inappropriate assessments. Professional organizations like the Division for Early Childhood (DEC) and the National Association for the Education of Young Children (NAEYC) propose using multiple methods for collecting information about children. A promising alternative to standardized, norm-referenced testing is the use of authentic assessment, which promotes a natural context to best understand what a child can do. It is a form of assessment that favors events, materials, and individuals who are familiar to the child. AUTHENTIC ASSESSMENT 3 Downloaded By: [Macy, Marisa] At: 23:06 15 January 2010 Real life conditions become the backdrop for children to apply what they know to a given situation. Head Start programs would benefit by having authentic eligibility assessments that link to curriculum and instruction because children will enter their programs with meaningful information (Bagnato et al., 2007; Grisham-Brown, Hallam, & Pretti-Frontczak, 2008). Results from the authentic assessment can be used to directly inform program planning, curriculum, instruction, and lesson plans. To implement authentic assessment, practitioners should pay close attention to the R-E-A-L framework: roles, equipment, assessment tools, and location. Role of data collector. Authentic assessment relies upon a team of people that consists of informed caregivers such as parents, grandparents, and other family members as well as teachers, speech therapists, and other professionals who are familiar with and have knowledge of the child’s skills and abilities (Bagnato & Neisworth, 1999; Guralnick, 2006). Effective teams have mutual respect for one another’s roles and expertise, ability to communicate with others, and openness to share assessment role responsibilities. Assessment responsibilities are shared when (a) parents are considered central members of the team with valuable observations and information to contribute (Meisels, Xue, Bickel, Nicholson, & Atkins-Burnett, 2001); (b) teachers and practitioners provide input (Dunst, 2002; Keilty, LaRocco, & Casell, 2009); and (c) the team relies upon the observations and evaluations of trained professionals such as occupational and speech therapists, depending on the child’s need (Meisels, Bickel, Nicholson, Xue, & Atkins-Burnett, 2001). Equipment and materials. Familiar equipment and materials are used to assess children using an authentic assessment framework. Common toys or household items are examples of materials that children will recognize from their natural environments. When assessment includes the actual or authentic activity with companion materials, the child is operating under more usual conditions and has experience performing similar tasks. For example, assessing a child’s adaptive skills during snack with all the familiar accompanying utensils, food items, and furniture can help to obtain an accurate assessment of the child’s true ability. Assessment tools. Select authentic assessment tools that bring together interdisciplinary and interagency teams (Losardo & Notari-Syverson, 2001; Slentz & Hyatt, 2008). Curriculum-based tools connect assessment to programming and intervention planning (Macy & Bricker, 2006). Curriculum-based assessments allow teams to gather information from various sources, including parents and teachers. Another benefit is that they can be used to monitor individual and group progress. Bagnato, Neisworth, and Pretti-Frontczak (in press) recommend eight quality standards for selecting assessment tools to include (a) acceptability—the social aspects of using a tool; (b) authenticity—contextual factors (e.g., everyday situations); (c) collaboration—the tool can be easily incorporated into interdisciplinary teamwork; (d) evidence—the tool has been found through research and practice to be valid, reliable, and useful; (e) multiple factors— used to gather information about a child (e.g., various methods, individuals, situations, and time points); (f) sensitivity—the tool is sensitive to child performance; (g) universality— children with special needs can be accommodated; and (h) utility—the extent the tool is useful to parents and professionals. These eight standards are illustrated in Figure 1. Approximately 100 different authentic and standard, norm-referenced assessments were rated using the eight standards by over 1,000 assessment users in an online study. Results from the online survey indicated that users identified authentic assessment as meeting more of the eight standards than the standardized, norm-referenced tests. Downloaded By: [Macy, Marisa] At: 23:06 15 January 2010 4 MACY AND BAGNATO FIGURE 1 Standards for judging assessment tools (from Bagnato et al., in press). Location. Authentic assessment approaches reflect the ongoing experiences children may encounter in their home, school, community, and other places where young children spend time. Authentic assessment takes place during the real life conditions under which the target behaviors/skills are needed for the child to function. Young children are often more comfortable and relaxed in familiar locations, and this will result in a more accurate assessment (Neisworth & Bagnato, 2004). The R-E-A-L framework can be used by Head Start professionals to facilitate implementation of an authentic assessment approach. The foundation for assessment should be to measure skills that reflect what a child is capable of doing in genuine situations. Authentic assessment is used to understand what children can do in naturalistic settings by using typical early childhood experiences to assess children. This is different from standardized, norm-referenced tests that are often administered in a clinical setting, with structured and adult-directed procedures, by people who are unfamiliar to the child, and test discrete isolated tasks that are unrelated to the child’s daily life. Given the questionable practice of using standardized, norm-referenced tests to determine a child is eligible for IDEA special services, further research and analysis on assessment AUTHENTIC ASSESSMENT 5 alternatives is necessary. The purpose of this study was to examine the technical adequacy of authentic assessment measures. METHOD Downloaded By: [Macy, Marisa] At: 23:06 15 January 2010 Nine authentic measures were chosen through a review of literature and surveys of practitioners investigating the most commonly used measures in preschool and early intervention settings (Bagnato, Neisworth, & Munson, 1997; Bagnato et al., in press; Pretti-Frontczak, Kowalski, & Brown, 2002). To be included in our review, the authentic measure needed to have published research available. Other authentic measures were considered for inclusion (like the Developmental Continuum from Teaching Strategies); however, we did not find published research on these measures. The following nine authentic measures are included in the study: r r r r r r r r r Adaptive Behavior Assessment System (ABAS), Assessment Evaluation and Programming System (AEPS), Carolina Curriculum for Preschoolers with Special Needs (Carolina), Child Observation Record (COR), Developmental Observation Checklist System (DOCS), Hawaii Early Learning Profile (HELP), Pediatric Evaluation of Disability Inventory (PEDI), Transdisciplinary Play-Based Assessment (TPBA), and Work Sampling System (WSS)/Ounce Some measures had multiple editions (i.e., AEPS, Carolina, ABAS, COR, and TPBA). Table 1 offers information about these measures. Research studies on the identified authentic assessments (i.e., ABAS, AEPS, Carolina, COR, DOCS, HELP, PEDI, TPBA, and WSS/Ounce) were reviewed in this synthesis. Research characteristics fell into two categories: accuracy (reliability) and effectiveness (validity, utility). Accuracy refers to the extent to which a tool identifies young children with disabilities. This includes reliability of the measure (e.g., consistency across test items and the use of cutoff scores in order for the tool to precisely or accurately measure a skill or behavior). Examples of accuracy include test-retest reliability, interrater reliability, intrarater reliability, and interitem consistency. Effectiveness refers to the extent to which a tool successfully identifies young children with disabilities. This includes the validity of the measure (i.e., including to what extent does the tool measure what it was designed to measure) and how it relates significantly to similar measures. Examples of effectiveness include predictive validity, concurrent validity, construct validity, test floors, and item gradients. The next section describes our strategy for searching the literature base for research studies on the accuracy and effectiveness of authentic assessment measures. Search Strategy Search Terms. Relevant published research studies were identified using the following search terms: authentic assessment, testing, early intervention, preschool, early childhood, eligibility, pediatrics, disabilities, handicap identification, and referral. More general terms of special schools, state programs resource, centers, and evaluations were also used. 6 Birth to 89 years 5 rating forms Birth to 6 Birth to preschool ABAS AEPS Carolina Age Range Parent/Primary Caregiver form is designed to be completed by parents or other primary caregivers. Two forms are available: Ages birth to 5 and Ages 5–21. 4-point rating scale: 3 = Always when needed 2 = Sometimes when needed 1 = Never when needed 0 = Is not able Includes a box to check if rater guessed. Includes section for rater to make comments regarding a specific item. 3-point rating scale: 2 = Consistently meets criterion 1 = Inconsistently meets criterion 0 = Does not meet criterion Six qualifying notes 3-point rating scale: (+) Mastery (+/−) Inconsistent/emerging skill (−) Unable to perform skill Qualifying notes Parent Form (B-5): 241 Teacher Form (2–5): 216 B-3: 249 3–6: 217 B-2: 359 2–5: 400 Communication, Community Use, Functional Pre-Academics, School/Home Living, Health and Safety, Leisure, Self-Care, Self-Direction, Social, Motor (10) Adaptive, Cognitive, Fine Motor, Gross Motor, Social-Communication, & Social (6) Cognition, Cognition/Communication, Communication, Personal-Social, Fine Motor, Gross Motor (6) Families encouraged to be involved throughout the assessment and instruction process. Family Report allows parents to be involved in collecting information and list/prioritize areas of interest. Family Involvement Scoring Features # of Items Domains TABLE 1 Nine Authentic Measures and Their Characteristics Downloaded By: [Macy, Marisa] At: 23:06 15 January 2010 n/a Provides cutoff scores by age intervals. Provides normreferenced scores based on age. Eligibility Features 7 21/2 to 6 Birth to 6 COR DOCS Developmental Checklist (DC): Language, Social, Motor, Cognition (4) Adjustment Behavior Checklist (ABC) Parental Stress and Support Checklist (PSSC) Initiative, Social Relations, Creative Representation, Music and Movement, Language and Literacy, Mathematics and Science (6) Provides normreferenced scores based on age. Parents are viewed as primary informant on the DC questionnaire. PSSC assesses parental stress, parental support, child adaptability, parent-child interaction, and environmental impact. DC: Raters check Yes or No (Yes = 1; No =0) ABC: 4-point rating scale: Very much like, Somewhat like, Not much like, Not at all like PSSC: 4-point rating scale: Highly agree, Somewhat agree, Sometimes agree, Do not agree DC: 475 ABC: 25 PSSC: 40 (Continued on next page) n/a Family Report is available to create reports for parents about their child that can be discussed at parent conferences or home visits. Parents are able to record notes about the child based on the parents’ observations of the child’s behavior at home on the report. Parent Guide available to explain the COR and for parents to record anecdotes based on the COR. 5-point rating scale: Five descriptive statements that represent a range of functioning from very poor to very superior 30 items, each with 5 levels Downloaded By: [Macy, Marisa] At: 23:06 15 January 2010 8 Birth to 6 6 months to 71/2 years HELP PEDI Age Range Self-Care Mobility Social Function (3) Cognition, Fine Motor, Gross Motor, Language, Social Emotional, Self Help (6) Domains Functional Skills: 197 Caregiver Assistance: 20 Modifications: 20 685 # of Items Materials available to increase parent participation in the assessment process; guidelines for inclusion of parent input are spread throughout. Options for administration include parent interview. Functional Skills: 0 = Unable, or limited in capability to perform item in most situations; 1 = Capable of performing item in most situations Caregiver Assistance: Independent, Supervise/Prompt/Monitor, Minimal assistance, Moderate assistance, Maximal assistance, Total assistance Modifications: No modifications, Child-oriented, Rehabilitation, Extensive modifications Family Involvement 4-point rating scale: (+) Skill or behavior is present (−) Skill is not present (+/−) Skill appears to be emerging (A) Skill or behavior is atypical or dysfunctional Qualifying notes Scoring Features TABLE 1 Nine Authentic Measures and Their Characteristics (Continued) Downloaded By: [Macy, Marisa] At: 23:06 15 January 2010 Provides normreferenced scores. Provides age ranges for skills. Eligibility Features WSS: PreGrade 5 WSS/Ounce WSS: Personal and Social Development, Language and Literacy, Mathematical Thinking, Scientific Thinking, Social Studies, The Arts, Physical Development & Health (7) Ounce: Personal Connections, Feelings About Self, Relationships with Other Children, Understanding and Communication, Exploration and Problem Solving, Movement and Coordination (6) Cognitive, Social-Emotional, Communication and Language, Sensorimotor Development n/a A list of developmental skills observed during play 3 types of ratings: Not Yet In Process Proficient Scoring system: (+) Skill at age level and his/her skills are qualitatively strong (−) Skill is below age level and team has qualitative concerns √ ( ) Need for further observation and/or testing (NO) No opportunity (NA) Not applicable due to age or disability Downloaded By: [Macy, Marisa] At: 23:06 15 January 2010 Ounce: Contains a Family Album element that is used by families to collect observations, photos, and mementos of their child’s growth and development. Includes play with parent in the assessment sequence. n/a n/a Note. ABAS = Adaptive Behavior Assessment System; AEPS = Assessment Evaluation & Programming System; Carolina = Carolina Curriculum for Infants/ Toddlers/Preschoolers with Special Needs; COR = Child Observation Record; DOCS = Developmental Observation Checklist System; HELP = Hawaii Early Learning Profile; PEDI = Pediatric Evaluation of Disability Inventory; TPBA = Transdisciplinary Play-Based Assessment; WSS/Ounce = Work Sampling System. Ounce: Birth to 31/2 Birth to 6 TPBA 9 10 MACY AND BAGNATO The nine authentic assessments (i.e., ABAS, AEPS, Carolina, COR, DOCS, HELP, PEDI, TPBA, and WSS/Ounce) were also included within the search. The search was done broadly in the fields of psychology, developmental disabilities, special education, allied health fields (speech and language therapy, physical therapy, occupational therapy), and as early intervention. Downloaded By: [Macy, Marisa] At: 23:06 15 January 2010 Sources. The primary databases included the following sources: CINAHL, Cochrane Library, Digital Dissertations, Ebsco Host, Education Resource Information Center (ERIC), Google Scholar, Health Source, Illumina, Medline, Ovid/Mental Measurements Yearbook Buros, Psychological Abstracts (PsycINFO), and Social Sciences Citation Index. Additionally, we conducted selective searches of unpublished masters’ theses and doctoral dissertations. Hand searches of select journals and ancestral searches were also conducted. Selection Criteria. The study had to meet the following criteria for inclusion: (a) researched one or more of the selected authentic assessment measures; (b) involved the evaluation of young children with disabilities or at risk for developing a disability due to environmental or biological risk conditions; (c) examined the accuracy or effectiveness of the measure at testing infants, toddlers, and preschool children with disabilities; and (d) disseminated in a scientific and scholarly publication, which included dissertation and thesis studies. This research synthesis was conducted as part of literature reviews and syntheses conducted at the Tracking, Referral and Assessment Center for Excellence (Dunst, Trivette, & Cutspe, 2002). RESULTS A total of 27 studies on authentic assessment were identified from the fields of child development, early intervention, psychology, special education, physical therapy, pediatrics, and behavioral development. The most studies were conducted on the AEPS. The following information is presented in Table 2: total number of studies that met the inclusion criteria, years articles were published, age range included in the studies, and the total number of participants in study samples. Participants There were over 10,000 young children who participated in these research studies on authentic assessment. Children’s ages ranged from birth to 224 months. Children were identified with various disabilities, and there were several studies that included children without disabilities and children who were at risk for developing a disability. Table 3 shows child characteristics that include total sample size, mean age in months, age range in months, and child ability characteristics. Types of Studies Each study reported in this synthesis examined some aspect of accuracy and/or effectiveness related to one or more of the authentic measures. We found the following types of studies: AUTHENTIC ASSESSMENT 11 TABLE 2 Research Studies on the Nine Measures Downloaded By: [Macy, Marisa] At: 23:06 15 January 2010 Tool # of Studies Publication Years ABAS AEPS Carolina 2 9 1 2006–2007 1986–2008 2006 COR DOCS HELP PEDI TPBA WSS/Ounce 3 5 2 2 4 1 1993–2005 1997–2005 1995–1996 1993–1998 1994–2003 2008 Children’s Age Range (in Months) 33 to 216 0 to 72 Mean age for the treatment group was 4.5 months 48 to 68 1 to 72 22 to 34 36 to 224 6 to 46 45 to 60 Sample Size (Children) 151 2,897 47 4,902 2,000+ 29 50 74 112 Note. ABAS = Adaptive Behavior Assessment System; AEPS = Assessment Evaluation & Programming System; Carolina = Carolina Curriculum for Infants/Toddlers/Preschoolers with Special Needs; COR = Child Observation Record; DOCS = Developmental Observation Checklist System; HELP = Hawaii Early Learning Profile; PEDI = Pediatric Evaluation of Disability Inventory; TPBA = Transdisciplinary Play-Based Assessment; WSS/Ounce = Work Sampling System. 13 interitem/interrater reliability, 5 test–retest reliability, 5 sensitivity/specificity, 15 concurrent validity, 3 predictive validity, and 6 construct/criterion validity. Accuracy (reliability) and effectiveness (validity) of the research studies are identified in Table 4. Reported Results A total of 16 studies examined the accuracy of authentic measures. There were 20 studies that examined the effectiveness of authentic measures. The number of studies exceeds 27 because some studies examined accuracy and effectiveness. Table 5 incorporates results on the accuracy and effectiveness of authentic assessment measures. DISCUSSION Using authentic assessment to determine children eligible for IDEA services has the potential to improve Head Start services for children (Bagnato, 2007; Grisham-Brown et al., 2008; Gulikers, Bastiaens, & Kirschner, 2004; Layton & Lock, 2007; Neisworth & Bagnato, 2004). In order to establish whether or not a child was eligible for early intervention services, many of the studies in our review had standardized, norm-referenced tests as a comparison from which to judge the merit of the authentic measures. This was the case for the majority of concurrent and constructs validity studies reviewed in this synthesis. McLean et al. (2004) suggest that one way to examine construct validity is to establish convergent validity by examining high positive correlations with other tests that measure the same constructs. Authentic assessments do not measure constructs in the same way as standardized, norm-referenced tests. Instead of comparing authentic measures 12 MACY AND BAGNATO TABLE 3 Research Studies with Participant Demographic Information Author(s) and Year (N = 27) Downloaded By: [Macy, Marisa] At: 23:06 15 January 2010 Anthony (2003) Bailey & Bricker (1986) Baird, Campbell, Ingram, & Gomez (2001) Bricker, Bailey, & Slentz (1990) Bricker, Yovanoff, Capt, & Allen (2003) Bricker et al. (2008) Calhoon (1997) Cody (1995) Sample Size Age Range in Months 10 32 13 6 to 46 n/a 11 to 47 Developmental delay Children with and without developmental delay Cri-du-Chat syndrome 335 2 to 72 861 1 to 72 1,381 4 25 1 to 72 22 to 35 22 to 34 Children with (mild, moderate, and severe) and without developmental delay, and at risk Children eligible and not eligible for early intervention/early childhood special education Same as above Language delay Previously identified as delayed in the areas of behavior, cognition, and language Down syndrome DelGiudice, Brogna, 47 n/a Romano, Paludetto, & Toscano (2006) Di Pinto (2006) 60 60 to 216 Fantuzzo, Grim, & Montes 733/1,427 n/a (2002) Friedli (1994) 20 n/a Gilbert (1997) 100 1 to 72 Hsia (1993) 82 36 to 72 Knox & Usen (1998) 10 45 to 224 Macy, Bricker, & Squires 68 6 to 36 (2005) McKeating-Esterle, Bagnato, 91 33 to 71 Fevola, & Hawthorne (2007) Meisels, Xue, & Shamblott 112 45.24 to 59.76 (2008) Morgan (2005) 32 4 to 60 Myers, McBride, & Peterson 40 7 to 36 (1996) Noh (2005) 65 36 to 64 Sayers, Cowden, Newton, Warren, & Eason (1996) Schweinhart, McNair, Barnes, & Larner (1993) Sekina & Fantuzzo (2005) Sher (2000) Slentz (1986) Wright & Boschen (1993) Child Characteristics ADHD (ADHD/PI; ADHD/C) Urban and low income Children with and without developmental delay Children with and without developmental delay Children with and without developmental delay Cerebral palsy Children eligible and not eligible for early intervention/early childhood special education Developmental delay, autism, hearing impairment/deafness, Down syndrome, MR, CP/muscular dystrophy, speech/language impairment, visual impairment/blindness, other health impairment, multiple disabilities At risk; children with special needs whose IEPs indicated that they were in the mild to moderate range (speech or physical impairment) Reactive attachment disorder Developmental delay 4 n/a Children eligible and not eligible for early intervention/early childhood special education Down syndrome 2,500 n/a Low income 242 20 55 to 68 36 to 67 53 40 36 to 72 36 to 84 Urban Children eligible and not eligible for early intervention/early childhood special education Children with and without developmental delay Cerebral palsy Note. ABAS = Adaptive Behavior Assessment System; ADHD = Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder; AEPS = Assessment Evaluation & Programming System; Carolina = Carolina Curriculum for Infants/Toddlers/Preschoolers with Special Needs; COR = Child Observation Record; CP = Cerebral Palsy; DOCS = Developmental Observation Checklist System; HELP = Hawaii Early Learning Profile; IEP = Individualized Education Plan; MR = Mental Retardation; PEDI = Pediatric Evaluation of Disability Inventory; TPBA = Transdisciplinary Play-Based Assessment; WSS/Ounce = Work Sampling System. 13 AUTHENTIC ASSESSMENT TABLE 4 Research Study Characteristics Accuracy (Reliability) Downloaded By: [Macy, Marisa] At: 23:06 15 January 2010 Author(s) and Year (N = 27) Test Anthony (2003) Bailey & Bricker (1986) Baird, Campbell, Ingram, & Gomez (2001) Bricker, Bailey, & Slentz (1990) Bricker, Yovanoff, Capt, & Allen (2003) TPBA AEPS DOCS Bricker et al. (2008) AEPS Calhoon (1997) Cody (1995) DelGiudice, Brogna, Romano, Paludetto, & Toscano (2006) Di Pinto (2006) Fantuzzo, Grim, & Montes (2002) Friedli (1994) Gilbert (1997) Hsia (1993) TPBA AEPS AEPS ABAS COR TPBA DOCS AEPS Knox & Usen (1998) Macy, Bricker, & Squires (2005) PEDI AEPS Meisels, Xue, & Shamblott, (2008) McKeating-Esterle, Bagnato, Fevola, & Hawthorne (2007) Morgan (2005) Myers, McBride, & Peterson (1996) Noh (2005) WSS ABAS AEPS AEPS DOCS TPBA AEPS Effectiveness (Validity) Interitema Sensitivitya Constructa Interraterb Test-Retest Specificityb Concurrent Criterionb Predictive xb x x x xa xb x x xa xb xa xb x x x x xa xb xb xa xb x x x xa xa xa xb xb x x x x x xa xa xb Sayers, Cowden, Newton, Warren, & Eason (1996) Schweinhart, McNair, Barnes, & Larner (1993) Sekina, & Fantuzzo (2005) Sher (2000) Slentz (1986) COR xb COR AEPS AEPS xb Wright & Boschen (1993) PEDI x AEPS x xa xb xa xb x x x x xa xa xa Note. ABAS = Adaptive Behavior Assessment System; AEPS = Assessment Evaluation & Programming System; Carolina = Carolina Curriculum for Infants/Toddlers/Preschoolers with Special Needs; COR = Child Observation Record; DOCS = Developmental Observation Checklist System; HELP = Hawaii Early Learning Profile; PEDI = Pediatric Evaluation of Disability Inventory; TPBA = Transdisciplinary Play-Based Assessment; WSSS/Ounce = Work Sampling System. 14 MACY AND BAGNATO TABLE 5 Reported Research Results Author(s) and Year (N = 27) Anthony (2003) Bailey & Bricker (1986) Downloaded By: [Macy, Marisa] At: 23:06 15 January 2010 Baird, Campbell, Ingram, & Gomez (2001) Bricker, Bailey, & Slentz (1990) Bricker, Yovanoff, Capt, & Allen (2003) Bricker et al. (2008) Calhoon (1997) Cody (1995) DelGiudice, Brogna, Romano, Paludetto, & Toscano (2006) Di Pinto (2006) Fantuzzo, Grim, & Montes (2002) Friedli (1994) Gilbert (1997) Hsia (1993) Knox & Usen (1998) Macy, Bricker, & Squires (2005) Meisels, Xue, & Shamblott (2008) Reported Results TPBA visual development guidelines were used by raters at Denver’s PLAY clinic and had positive interrater agreement results. AEPS correlation with the Gesell Developmental Schedule (Knobloch et al., 1980) was strong for the whole test but not individual areas. AEPS could be successfully administered in a reasonable amount of time. DOCS may lack sensitivity in detecting variations in development. AEPS correlation across areas was r = .88 (p < .001). AEPS newly established cutoff scores in the 2nd edition identified eligible children accurately most of the time. AEPS cutoff scores performed similarly to the Bricker et al. (2003) study. The measure accurately identified the majority of children correctly. Children performed better (i.e., higher scores) on the TPBA than the conventional test, and the play-based assessment provided a richer description of children’s emerging skills. In the HELP study, the play age obtained from the authentic assessment was highly correlated with the Developmental Age Equivalent of the conventional assessment (i.e., BSID). After 1 year, children in the Carolina condition made progress and had higher DQ than children in the comparison condition who made slight progress but improvements were not statistically significant. ABAS accurately documents poor social adaptive outcomes for children with ADHD. The study supports the use of the COR assessment method for low-income urban preschool children; however, a three-factor model should replace the proposed six-factor model. TPBA had favorable test retest results, interrater agreement, and concurrent validity. Significant difference among raters was found: mothers rated the child’s skills highest, the fathers next, and the teachers last. Differences among raters on the DOCS may influence eligibility decisions. The AEPS has strong interrater agreement at both domain (ranging from .87 social to .94 adaptive) and total test (.90) levels. Strong relationship between individual domain scores (.64 to .96) and total test (.98) when internal consistency was examined. Findings also showed that the AEPS was sensitive to performance differences of children with delays. The PEDI is a useful tool for describing the area of functional delay in children with cerebral palsy. It also appears to be sensitive to changes that were observed clinically. The AEPS accurately classified all eligible children and over 94% (n = 64/68) of the noneligible children. The overall sensitivity was 100%; specificity was 89%. The AEPS used to determine eligibility was positively and significantly correlated with conventional eligibility measures. Finally, the observers who scored the AEPS had strong agreement on observations made about child performance. Study found evidence for validity and reliability of WSS, suggesting that WSHS accurately assesses language development, literacy, and mathematics skills in young children. (Continued on next page) AUTHENTIC ASSESSMENT 15 TABLE 5 Reported Research Results (Continued) Author(s) and Year (N = 27) McKeating-Esterle, Bagnato, Fevola, & Hawthorne (2007) Morgan (2005) Myers, McBride, & Peterson (1996) Downloaded By: [Macy, Marisa] At: 23:06 15 January 2010 Noh (2005) Sayers, Cowden, Newton, Warren, & Eason (1996) Schweinhart, McNair, Barnes, & Larner (1993) Sekina, & Fantuzzo (2005) Sher (2000) Slentz (1986) Wright & Boschen (1993) Reported Results ABAS-II is correlated with ratings of informed opinion when assessing children for early intervention. Evidence supports the predictive validity of the DOCS-II in detecting RAD in a randomized sample. The overall mean number of days to complete the eligibility assessment process took the group using the TPBA 22 days less than it took the group using a conventional test. The AEPS has satisfactory interrater reliability agreement in the cognitive and social domains. Strong relationship between individual domain scores and items in the domains. When children’s scores increased on the gross motor domain of the HELP, they did the same for the PSI. The COR was found to be a psychometrically promising tool for the assessment of children’s development in developmentally appropriate early childhood programs. Also, the COR helped staff to understand early childhood development and curriculum and to prepare individualized education programs for their children. Univariate and multivariate results provide support for convergent and divergent validity of the COR dimensions. Fifteen of the 18 variables differentiated the three COR dimensions, particularly the COR Cognitive and Social Engagement dimensions. Professionals using the AEPS were able to identify eligible children. Moderate interrater reliability for the communication domain and high reliability for other domains. Positive results of this study support the technical properties of the AEPS. Interrater agreement was very high at .94 for the entire test and ranged from .84 to .94 for the six domains. Results for two administrations of the AEPS (N = 18) revealed strong level of stability across time for the total test (.91), domain scores varied between high (fine motor .86, cognitive .91, social communication .77) to moderate (social .50) to low stability (gross motor .07 and self-care .13). Internal consistency was strong for all domains except self-care. Concurrent validity was examined by comparing the AEPS with the McCarthy (1972) and the Uniform Performance Assessment System (Haring, White, Edgar, Affleck, & Hayden, 1980) with mixed results ranging from very weak to strong relationships between domains and scales. Satisfactory information is provided to confirm the PEDI’s usefulness for clinical and research purposes with children with cerebral palsy. Note. ABAS = Adaptive Behavior Assessment System; AEPS = Assessment Evaluation & Programming System; Carolina = Carolina Curriculum for Infants/Toddlers/Preschoolers with Special Needs; COR = Child Observation Record; DOCS = Developmental Observation Checklist System; HELP = Hawaii Early Learning Profile; PEDI = Pediatric Evaluation of Disability Inventory; TPBA = Transdisciplinary Play-Based Assessment; WSS/Ounce = Work Sampling System. with other good examples of authentic and linked eligibility assessment, many of the studies in our review made comparisons with nonlinked eligibility tests. For example, in the Macy, Bricker, and Squires (2005) study, the AEPS (curriculum linked measure) was compared with the Battelle Developmental Inventory (not linked to curriculum). 16 MACY AND BAGNATO Future research should continue not only to examine the accuracy and effectiveness of authentic measures but also to make comparisons using an external standard. Some examples of external standards are (a) correct identification rates based on expert consensus, (b) the need for services—service-based eligibility, and (c) probability of succeeding/progressing in Head Start or typical setting with typical peers without support services. Another area of research should study the effects of the initial eligibility assessment using authentic measures on child outcomes using a longitudinal design. Cost–benefit studies need to be conducted on the use of authentic assessment practices used to determine children eligible for IDEA services. This type of evidence could be helpful to policymakers when reauthorizing policies and updating eligibility assessment guidelines. Downloaded By: [Macy, Marisa] At: 23:06 15 January 2010 Limitations A number of authentic assessment measures are commercially available; however, we chose to examine only these nine measures because they appeared most often in the professional literature and by accounts from practitioners. Other authentic measures, like the Developmental Continuum from Teaching Strategies, were not included in this review because they did not meet our inclusion criteria. For example, tools like the Developmental Continuum have conducted research studies; however, we were unable to locate these in journals and/or the databases we searched. Sometimes publishers maintain the results from studies for proprietary reasons and they are not available to the public. The body of literature contained other publications related to authentic assessment and we included only research studies that involved young children who were at risk or had a disability in the sample. Authentic assessment can be used for designing a program for a child, creating interventions, and to evaluate the efficacy of a child’s individualized program. Not only does authentic assessment have potential to accurately identify children in need of services, it also has important implications beyond eligibility determination (Neisworth & Bagnato, 2004). Findings of this study will help professionals to critically identify characteristics of authentic assessment research findings that influence the accurate and representative documentation of a young child’s early intervention eligibility assessment experience. Head Start programs would benefit from an assessment approach that provides useful information linked to curriculum and instruction in order to serve children more efficiently. Additionally, an approach is needed that can monitor ongoing child performance (Downs & Strand, 2006; Grisham-Brown, Hallam, & Brookshire, 2006; Grisham-Brown et al., 2008; Hebbeler, Barton, & Mallik, 2008; Meisels, Liaw, Dorfman, & Nelson, 1995). Authentic assessment is a viable alternative to eligibility assessments that use standardized, norm-referenced tests (Bagnato, 2005, 2007; Bagnato & Neisworth, 1992; Macy & Hoyt-Gonzales, 2007; McLean, 2005; Neisworth & Bagnato, 2004). An authentic assessment approach has growing support from early childhood professional organizations (i.e., DEC and NAEYC) and from the literature base (Bagnato & Neisworth, 2005). The authentic assessment studies reported here in this research study are the first phase of research supporting the use of an authentic assessment approach for eligibility determination. Although this foundation is a good start, more research is needed to continue to explore authentic measures and approaches. AUTHENTIC ASSESSMENT 17 Downloaded By: [Macy, Marisa] At: 23:06 15 January 2010 REFERENCES *Indicates studies used in the synthesis. **Indicates measures used in the synthesis. *Anthony, T. L. (2003). The inclusion of vision-development guidelines in the Transdisciplinary Play-Based Assessment: A study of reliability and validity. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Denver, Denver, CO. Bagnato, S. J. (2005). The authentic alternative for assessment in early intervention: An emerging evidence-based practice. Journal of Early Intervention, 28, 17–22. Bagnato, S. J. (2007). Authentic assessment for early childhood intervention best practices: The Guilford school practitioner series. New York: Guilford. Bagnato, S. J., Macy, M., Salaway, J., & Lehman, C. (2007). Research foundations for conventional tests and testing to ensure accurate and representative early intervention eligibility. Pittsburgh, PA: TRACE Center for Excellence in Early Childhood Assessment, Early Childhood Partnerships, Children’s Hospital/University of Pittsburgh, U.S. Department of Education Office of Special Education Programs, and Orelena Hawks Puckett Institute. Bagnato, S. J., McKeating-Esterle, E., Fevola, A. F., Bartalomasi, M., & Neisworth, J. T. (2008). Valid use of clinical judgment (informed opinion) for early intervention eligibility: Evidence-base and practice characteristics. Infants and Young Children, 21, 334–348. Bagnato, S. J., & Neisworth, J. T. (1992). The case against intelligence testing in early intervention. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education, 12, 1–20. Bagnato, S. J., & Neisworth, J. T. (1999). Collaboration and teamwork in assessment for early intervention. Comprehensive Psychiatric Assessment of Young Children, 8, 347–363. Bagnato, S. J., & Neisworth J. T. (2005). DEC recommended practices: Assessment. In S. Sandall, M. L. Hemmeter, B. J. Smith, & M. McLean (Eds.), DEC recommended practices (pp. 45–50). Longmont, CO: Sopris West. Bagnato, S. J., Neisworth, J. T., & Munson, S. (1997). LINKing assessment and early intervention. Baltimore, MD: Brookes. Bagnato, S. J., Neisworth, J. T., & Pretti-Frontczak, K. L. (in press). LINKing assessment and early intervention (4th ed.). Baltimore, MD: Brookes. Bagnato, S. J., Smith-Jones, J., Matesa, M., & McKeating-Esterle, E. (2006). Research foundations for using clinical judgment (informed opinion) for early intervention eligibility determination. Cornerstones, 2(3), 1–14. *Bailey, E., & Bricker, D. (1986). A psychometric study of a criterion-referenced assessment designed for infants and young children. Journal of the Division of Early Childhood, 10, 124–134. *Baird, S. M., Campbell, D., Ingram, R., & Gomez, C. (2001). Young children with Cri-du-Chat: Genetic, developmental, and behavioral profiles. Infant-Toddler Intervention, 11, 1–14. **Bricker, D. (Ed.). (1993). Assessment, evaluation, and programming system for infants and children (1st ed.). Baltimore, MD: Brookes. **Bricker, D. (Ed.). (2002). Assessment, evaluation, and programming system for infants and children (2nd ed.). Baltimore, MD: Brookes. *Bricker, D., Bailey, E., & Slentz, K. (1990). Reliability, validity, and utility of the Evaluation and Programming System: For infants and young children (EPS-I). Journal of Early Intervention, 14, 147–160. *Bricker, D., Clifford, J., Yovanoff, P., Pretti-Frontczak, K., Waddell, M., Allen, D., et al. (2008). Eligibility determination using a curriculum-based assessment: A further examination. Journal of Early Intervention, 31, 3–21. *Bricker, D., Yovanoff, P., Capt, B., & Allen, D. (2003). Use of a curriculum-based measure to corroborate eligibility decisions. Journal of Early Intervention, 26, 20–30. *Calhoon, J. M. (1997). Comparison of assessment results between a formal standardized measure and a play-based format. Infant-Toddler Intervention: The Transdisciplinary Journal, 7, 201–214. *Cody, D. A. (1995). Play assessment as a measure of cognitive ability in developmentally delayed preschoolers. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, George Mason University, Fairfax, VA. Danaher, J. (2005). Eligibility policies and practices for young children under Part B of IDEA (NECTAC Notes No.15). Chapel Hill, NC: The University of North Carolina, FPG Child Development Institute, National Early Childhood Technical Assistance Center. *DelGiudice, E., Brogna, G., Romano, A., Paludetto, R., & Toscano, E. (2006). Early intervention for children with Down syndrome in southern Italy: The role of parent-implemented developmental training. Infants & Young Children, 19, 50–58. Downloaded By: [Macy, Marisa] At: 23:06 15 January 2010 18 MACY AND BAGNATO *Di Pinto, M. (2006). The ecological validity of the Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Functioning (BRIEF) in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: Predicting academic achievement and social adaptive behavior in the subtypes of ADHD. Dissertation Abstracts International, 67(03), 1696B. (UMI No. 3209793) Downs, A., & Strand, P. S. (2006). Using assessment to improve the effectiveness of early childhood education. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 15, 671–680. Dunst, C. J. (2002). Family-centered practices: Birth through high school. Journal of Special Education, 36(3), 139–147. Dunst, C. J., Trivette, C. M., & Cutspe, P. A. (2002). An evidence-based approach to documenting the characteristics and consequences of early intervention practices. Centerscope, 1(2), 1–6. Retrieved July 11, 2009, from http://www. evidencebasepractices.org/centerscope/centerscopevol1no2.pdf Dunst, C. J., & Hamby, D. W. (2004). States’ Part C eligibility definitions account for differences in the percentage of children participating in early intervention programs. Snapshots, 1(4). Retrieved July 12, 2009, from http://www.tracecenter.info/products.php *Fantuzzo, D., Grim, S., & Montes, G. (2002). Generalization of the Child Observation Record: A validity study for diverse samples of urban, low-income preschool children. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 17, 106–125. *Friedli, C. (1994). Transdisciplinary play-based assessment: A study of reliability and validity. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Colorado, Denver, CO. *Gilbert, S. L. (1997). Parent and teacher congruency on variations of a screening assessment: An examination (Report No. H023B50009). Auburn, AL: Auburn University. (ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. ED413726) Grisham-Brown, J., Hallam, R., & Brookshire, R. (2006). Using authentic assessment to evidence children’s progress toward early learning standards. Early Childhood Education Journal, 34, 45–51. Grisham-Brown, J., Hallam, R., & Pretti-Frontczak, K. L. (2008). Preparing Head Start personnel to use a curriculumbased assessment: An innovative practice in the “age of accountability.” Journal of Early Intervention, 30, 271–281. Gulikers, T. M., Bastiaens, T. J., & Kirschner, P. A. (2004). A five-dimensional framework for authentic assessment. Educational Technology Research and Development, 52(3), 67–86. Guralnick, M. J. (2006). Family influences on early development: Integrating the science of normative development, risk and disability, and intervention. In K. McCartney & D. Phillips (Eds.), Blackwell handbook of early childhood development (pp. 44–61). Malden, MA: Blackwell. **Haley, S. M., Coster, W. J., Ludlow, L. H., Haltiwanger, J. T., & Andrellos, P. J. (1992). Pediatric Evaluation of Disability Inventory (PEDI). Boston: New England Medical Center Hospitals, Inc. **Harrison, P. L., & Oakland, T. (2003). Adaptive Behavior Assessment System-Second Edition. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation. Hebbeler, K., Barton, L. R., & Mallik, S. (2008). Assessment and accountability for programs serving young children with disabilities. Exceptionality, 16, 48–63. **High/Scope Educational Research Foundation. (2003). Preschool Child Observation Record–Second Edition. Ypsilanti, MI: High/Scope Press. **Hresko, W. P., Miguel, S. A., Sherbenou, R. J., & Burton, S. D. (1994). Developmental Observation Checklist System. Austin, TX: PRO-ED. *Hsia, T. (1993). Evaluating the psychometric properties of the Assessment, Evaluation, and Programming System for Three to Six Years: AEPS Test. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Oregon, Eugene, OR. Individuals with Disabilities Education Improvement Act, Pub. L. No. 108-446, 20 U.S.C. (2004). **Johnson-Martin, N. M., Attermeier, S. M., & Hacker, B. J. (2004). The Carolina curriculum for infants and toddlers with special needs (3rd ed.). Baltimore, MD: Brookes. **Johnson-Martin, N. M., Hacker, B. J., & Attermeier, S. M. (2004). The Carolina curriculum for preschoolers with special needs (2nd ed.). Baltimore, MD: Brookes. Keilty, B., LaRocco, D. J., & Casell, F. B. (2009). Early interventionists’ reports of authentic assessment methods through focus group research. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education, 28, 244–256. *Knox, V., & Usen, Y. (1998). Clinical review of the Pediatric Evaluation of Disability Inventory. The British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 63, 29–32. Layton, C. A., & Lock, R. H. (2007). Use authentic assessment techniques to fulfill the promise of No Child Left Behind. Intervention in School & Clinic, 42, 169–173. **Linder, T. W. (1993). Transdisciplinary play-based assessment: A functional approach to working with young children. Baltimore, MD: Brookes. Losardo, A., & Notari-Syverson, A. (2001). Alternative approaches to assessing young children. Baltimore, MD: Brookes. Downloaded By: [Macy, Marisa] At: 23:06 15 January 2010 AUTHENTIC ASSESSMENT 19 Macy, M., & Bricker, D. (2006). Practical applications for using curriculum-based assessment to create embedded learning opportunities for young children. Young Exceptional Children, 9(4), 12–21. *Macy, M. G., Bricker, D. D., & Squires, J. K. (2005). Validity and reliability of a curriculum-based assessment approach to determine eligibility for part C services. Journal of Early Intervention, 28, 1–16. Macy, M., & Hoyt-Gonzales, K. (2007). A linked system approach to early childhood special education eligibility assessment. TEACHING Exceptional Children, 39(3), 40–44. *McKeating-Esterle, E., Bagnato, S. J., Fevola, A., & Hawthorne, C. (2007). A comparison of clinical judgment (informed opinion) with performance-based assessment to document early intervention status. Unpublished master’s thesis, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA. McLean, M. (2005). Using curriculum-based assessment to determine eligibility: Time for a paradigm shift? Journal of Early Intervention, 28, 23–27. McLean, M., Bailey, D. B., & Wolery, M. (2004). Assessing infants and preschoolers with special needs (3rd ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson. Meisels, S. J., Bickel, D. D., Nicholson, J., Xue, Y., & Atkins-Burnett, S. (2001). Trusting teachers’ judgments: A validity study of a curriculum-embedded performance assessment in kindergarten to grade 3. American Educational Research Journal, 38, 73–95. **Meisels, S. J., Dombro, A. L., Marsden, D. B., Weston, D., & Jewkes, A. (2003). The Ounce Scale: An observational assessment for infants, toddlers, and families. New York: Pearson Early Learning. **Meisels, S. J., Jablon, J. R., Marsden, D. B., Dichtelmiller, M. L., & Dorfman, A. B. (2001). The Work Sampling System (4th ed.). New York: Pearson Early Learning. Meisels, S. J., Liaw, F., Dorfman, A., & Nelson, R. F. (1995). The Work Sampling System: Reliability and validity of a performance assessment for young children. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 10, 277–296. Meisels, S. J., Xue, Y., Bickel, D. D., Nicholson, J., & Atkins-Burnett, S. (2001). Parental reactions to authentic performance assessment. Educational Assessment, 7, 61–85. *Meisels, S. J., Xue, Y., & Shamblott, M. (2008). Assessing language, literacy, and mathematics skills with Work Sampling Head Start. Early Education and Development, 19, 963–981. Morgan, F. T. (2005). Development of a measure to screen for reactive attachment disorder in children 0–5 years. Dissertation Abstracts International, 66(04), 2312B (UMI No. 3173576). *Myers, C. L., McBride, S. L., & Peterson, C. A. (1996). Transdisciplinary, play-based assessment in early childhood special education: An examination of social validity. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education, 16, 102–126. National Association of School Psychologists. (2005). NASP position statement on early childhood assessment. Bethesda, MD: Author. National Research Council. (2008). Early childhood assessment: Why, what, and how. Washington, DC: National Academies Press. Neisworth, J. T., & Bagnato, S. J. (2004). The mismeasure of young children: The authentic assessment alternative. Infants & Young Children, 17, 198–212. *Noh, J. (2005). Examining the psychometric properties of the second edition of the Assessment, Evaluation, and Programming System for three to six years: AEPS Test–Second Edition (3–6). Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Oregon, Eugene, OR. **Parks, S., Furono, S., O’Reilly, K., Inatsuka, T., Hoska, C. M., & Zeisloft-Falbey, B. (1994). Hawaii early learning profile (HELP). Palo Alto, CA: Vort. Pretti-Frontczak, K., Kowalski, K., & Brown, R. D. (2002). Preschool teachers’ use of assessments and curricula: A statewide examination. Exceptional Children, 69, 109–123. *Sayers, L. K., Cowden, J. E., Newton, M., Warren, B., & Eason, B. (1996). Qualitative analysis of a pediatric strength intervention on the developmental stepping movements of infants with Down syndrome. Adapted Physical Activity Quarterly, 13, 247–268. *Schweinhart, L. J., McNair, S., Barnes, H., & Larner, M. (1993). Observing young children in action to assess their development: The High/Scope Child Observation Record study. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 53, 445–454. *Sekina, Y., & Fantuzzo, J. (2005). Validity of the Child Observation Record: An investigation of the relationship between COR dimensions and social-emotional and cognitive outcomes for Head Start children. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment, 23, 242–261. 20 MACY AND BAGNATO Downloaded By: [Macy, Marisa] At: 23:06 15 January 2010 Shakelford, J. (2002). Informed clinical opinion (NECTAC Note No. 10). Chapel Hill, NC: The University of North Carolina, Frank Porter Graham Child Development Institute, National Early Childhood Technical Assistance Center. Shakelford, J. (2006). State and jurisdictional eligibility definitions for infants and toddlers with disabilities under IDEA (NECTAC Note No. 21). Chapel Hill, NC: The University of North Carolina, Frank Porter Graham Child Development Institute, National Early Childhood Technical Assistance Center. *Sher, N. (2000). Activity-based assessment: Facilitating curriculum linkage between eligibility evaluation and intervention. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Oregon, Eugene, OR. *Slentz, K. (1986). Evaluating the instructional needs of young children with handicaps: Psychometric adequacy of the Evaluation and Programming System-Assessment Level II. Dissertation Abstracts International, 47 (11), 4072A. Slentz, K. L., & Hyatt, K. J. (2008). Best practices in applying curriculum-based assessment in early childhood. In A. Thomas & J. Grimes (Eds.), Best practices in school psychology V (Vol. 2, pp. 519–534). Bethesda, MD: National Association of School Psychologists. *Wright, F. V., & Boschen, K. (1993). The Pediatric Evaluation of Disability Inventory (PEDI) validation of a new functional assessment outcome instrument. Canadian Journal of Rehabilitation, 7, 41–42. Zigler, E., & Styfco, S. J. (2000). Pioneering steps (and fumbles) in developing a federal preschool intervention. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education, 20, 67–70. View publication stats