Conlents lists available at SciVerse SCienceDirect

Journal of Economic Psychology

journal homepage: www.elsevier.comllocateljoep

Influencing behaviour: The minds pace way

P. Dolan d. M. Hallsworth b, D. Halpern" D. King d, R. Metcalfe e, L Vlaev r.

"Dcpa;·tr.lo!lIt a/SoCial Pollt}', LOlldon ,');-:/;001 of E,(womic>, }bllgh~:;n Srreet LcndOl; W(2A 2AL UK

"!n,(Jrntc :i)r (()vemn1("nr, ) tar/ron GarCvns. Landon SIN! Y SAlt UK

'Hl'iwvlCllrai [;l3igilr Te(1m, [ahwe: Offict'. ?D ~'/t>;[?liilil, Lomi0'1 SWiA 2AS UK

n Imp!!rI<li (olkge Londo!!, S,. Mary's HCl-p:ral, Pad:lwg;oH. !..vJl&w ~{i.! INY. UK

C ;l,,1ert:m (0,'kge, Umvcrs~:y oj Ox(ortL Oxford eX! 4JD, 11K

'Cenm> }{}r ilea/1I1 P:':!iry, Im;Jena{ College' LUI:::h'n, Sr. Mmy \ fin,pHe;!, L::ndon W2 lNY, UK

---.-----------~

ARTICLE

INfO

ABSTRACT

I1r;1(1,' ili:'lary:

RC::;.>lved 7 Ocwner :WlO

Heteived 111 revm'r: (orm :3 October 2011

AcU'ptt?d 17 0, rober 20 I I

AV,11IdLIr cnlll;e 28 (klober 20},

Iii c/{lS\lficanan

DO'J

D50

l)80

HuO

;00

The ahility to mfluence behaviour ls cenerill to nldny ot the key policy challenges 111 areas

such JS health, financ(' dnd cJimare change. The I~sual route to llf'hcWIOUf change in eco­

nomIcs cmd psychology has been:o a:rempt to 'change nlll1ds' by ::lflu~ncmg the way pl!O­

pIe think through information and tnLl!ntivcs, Thele IS, however. lrlcrt:'Jsing t:vidence m

suggest that 'chi1:lg:ng C0n~exts' hy influeocir:g thl! environment'> wlthm which people

Jct (::1 largl!!Y au(O,ndtic ways) can IldVC important effects on hehavlour. We plcsenr it

mrv::r:,ollk MINDSPACE, which gathers up the nine most robust cfEeds that mflucnce

our brhaviour in mostly automatlc \.fa.lher fhan ueliberate} ways. Tl-:is Framework is being

Lls0d by polkym<1kers <1$ af'. accessible 5Umn'.1fy of [he dcacemic lt~er:.;ure. To motrvatc

furthcr rescJrch aod acadCliUC :;cflltiny, we provide ~onle eVldeoct: of the effects in <KtiOl!

and hrghlight 50me of the ~ign:j(anr gaps in our knowledge,

;£i 2011 F.!sevler B V. All ngh::s reserved.

rS1/c!.W·'(J dasstjiumo'1

1;00

2900

3800

lJ{lU

3312

3900

4030

Ke}'v,o!d"

BdldVlO12f d:,1I1ge

CCn!rxt ['ffects

Cholt'(· afchllectur0

DeCiSIOn nhlki1g

RatlUo.lllty

1'1I;~ht

poliCy

*- l'TTeSp()nd;'g dllIL;)] Tei,. ""44 ,:C)20-),';127159.

f-lI1ml cddrt'ss£s: p.ll do[;:n0'I,,, ;)C,,' k (r. DoI<lLl, ;r.I(ilad.f:tlJ:5WOI rh'c'~IJI5t]lu~('to]);uvel!lm'~r,r.or:; ::k :~1. HalbwDr:h), d,:v'd."Jlp<?r'l'''!(,)Jlr!Ct-ojjke ,,-,v,­

, •.gr:v l'k (0 HJlpfl'II;, d~''1'ink_ki:lg(!'Zf)lI:"lh'Pdl..lC 'lk (D :<1l1g;' rni-;c!'Lmc':,II!t'(:;"menon CX.dCttj( fit MCh>J!fe), LVL:,: .. "rp'1p<'<)JI..l( ti"; 'J Vlil'-'V}

0\67-4870,lS

sef from CAllC,

COl: !O. j ~'1;'!; :oep lUll lll,mN

2011 E:sevWf B V. A.t

q;ht~

rev,rvcd.

P. Doiml N al !Journol of f.csDomlC Psychology jJ (2012) ::!(A-j;77

265

1. Introduction

Over the last de(~lde or so, behaviomal economics, which seeks to apply evidence from psychology to economic models of

ded::,ion-making, has moved from a fringe activity to OnE' that i<; increasingly familiar and accepted (De!laVigna, 2009;

Kahnem<1!1, 2003,'), 2003b; Leiser & Azar. 2008; Poundstone, 2010; Thaler & Suostein. 2008), Moreover. there is increasing

agreement across the behavioer.11 sciences that our behaviour is significantly inf1uenced by facrars associatec with the context

or sit'.)ation we find ourselves in. The shl?ervolume of results emerging from :he behavioural l?conomicsli[ef ature, howeveccan

ilhlke it difficult to see which effects appear to have common chMJ.cteri"'tics aod hard to sort robust effects from one-off results.

This sometimes makes i: difficult to apply behavioural economics in practical policy settings, st!ch as when designing poli(·y to

discourage some things (vandalism, littering, excess debt And excess absenteeism) and encourage others (vobnteering, voti ng,

sdving for retirement, and increasing productivity). Against this background, this paper presents ':\'1r~DSPACE' as a helpful

mnemonic for thinking abocT the effects on our behaviour that res:J(t from conrextual (r.')ther than cognitive} influences,

In broac terms, there are two ways of :hinking about individual behaviour and how to influence it. The first is b<lSed on

inf1uencing what people consciously think about. We might call this the 'cognitive' model. The presumption is we will ana­

lyse the incentivE'S offered to Us, and act in ways that reflect our best interest~ : however so defined). We can therefore influ­

ence behavIOur by 'changing minds': that is, Through conscious reflection on the surrounding environm(>m. The contrasting

modeJ focuses on the more automdtic processes of judgement and influence - the w;;y we simply respond to the environ­

men:. ThiS shifts the fo::us of attention away from facts and information. and tmvards the conlext wi~hin Which people act.

\Ve might call tilts the 'context' model of behaviour. The context model recognises th;;t people are sometimes seemingly irra­

tional dnd tnconsi~tent in their choices, often bf'cause of the influence of surrounding facrors (see Thaler and Sunstein (2008)

and Aridy (2008;; for recent reviews;.

The:-,e two JPproaches are fouI1ded on two distinct 'systems' operating in the brain that have been identified by psychol~

agists and neuroscientists: '5ysl"em l' processes, winch are automa[ic, uncontrolled, effortless. associative, fast, unconscious

and J.ffective; and 'System 2' processes, which are reflective, controlled, effonful, rule-based, slow. conscious and rational

(Ch,nken & Trope, 1999; Evans, 2008). System 2, the 'reflective mind', has limited capacity, but offers more systematic

.lnd 'deeper' analysis; SY'item 1. the 'automatic mind'. processes many things separatf:'ly. simul:aneously, and often uncon­

sciously Evidence of separate brain structures for automatic processing of inforrn.ation has provided substantJaJ support to

.his dual process model (Rangel, Camerer, & Montague, 2008).

Partly owing to the dominance ofst~lndard economic models. and the rational choice paradigm in general (Elster. lY86),

most traditional interventions in public policy have rt'liec', on the reflective mind (Sys[em 2) a'i a route to behaviour change,

which utilises informadon (e.g. persuasion and education campaigns) .1nd incentives ofv.1cious kinds to change cognitive

assessments of the costs .md benefits of different decision<;. Unfortunately, this appro<lCh leaves d substantial proportion

of :he vctriance in behaviour to be explained (see Webb& Sheeran, 2006;. For example, Sheeran P002) report a mN.1-dIlalysis

of 422 studies, which implied that changing in;:entions would account for 28?;; of the Variance in behaviour change, and

meta-analyses of cOfrel,Hions between intentions and specific health behaviours h.1ve fo~nd similar effects in studies of con­

dom use (Sheeran, Abraham, & Orbel!, 1999] and exercbe behaviour (Hausenbla:" Caron, & Mack, 1997,. There may be many

cases where both systems work simultaneously for the same behaviour, anc understandiIl,1S the contextL:al cues that make

one sy<;[em. override the other 1S important when conSidering the lessons from behavioural economics,

This paper therefore focuses on the more automatic (System 1) and often context~based drivers of behaviour. because

they rely on ch<mging the environment within which the person acts without nece'isarily changing the underlying cogni­

tions. There are now hundreds of different claimed effects aod influeI1ces on hehdViolJr. Some of the d~lims in the literature

are based nn just one Of two studies or intervennons or may not translate well to ditferent target audience,,_ It is helpful for

acadelnic dis(OUl"S(", if we can bring together the robust effects on bebaviour <;0 trklt re<;earch (dn explore these erfect~ fur­

ther and, where appropriate, revise aod upcate our understanding of what these robust effects reatly look like and the con~

texts within which they are mos: pronouncec, Policy-makers too require a framework or s:rllcture Within which to think

about mterventlons c.esignee to 'nudge' people in particular directions.

10 the next section. we 'gather up' the most robust effects tha~ have been repeatedly Found to have strong lmpac::<; on behav­

jO'Jr operati ng largely, but cC'rtainly not exclusively, on the a:..ltoma:ic system. This article is an 'iotegrdtivE' revI(,w', not a 'sys­

tema:ic revie\'\", of the IirerJture. so our rese<lrch syn~hesis aims to bring together emergent themes from the literature in a

deliberately memorable form, using the mnemonic MINDSPACE. In so doing. :he effects can be tested and scrutimsed more di­

rectly by aC.1demics anc:. can addrionally be used a '7oolkit' or 'checklisr' by policy-makers ~Halpern, 2010: Halpern. B.1tes,

Beilles, & H("dthfieJd, 2004;.

In the third section_ we consider some of the polky issues. The MI~DSPACE framework is becoming widely used within

the policymaking commeoity, ane pdrticularly through its appiicdtion by the UK's Behavioural Insight Team based in the

Cabinet Office {see for eX.3mple. Cabinet Cabinet Office, 20 to, 201 !: i-1.llpertl, 2010). We explain how policy makers can

use Ml:'\lOSPACE;:o improve the effectiveness of existing and n(>w behdvlo:Jr change policies. The need for robust evaluations

of interventions is made dear. with a recommendation that poligtmakers work with acad€'mic'i to ensure the e!rectiveness

and cost etrectivene')s of imerventions ttMt apply these insights.

In the fin~ll section, we begin by discU'lsing the reldtionshlp between MINDS PACE ,md Nudge, the book rhat captured

policymakers' attention and introduced them to behavioural economics, Vve then provide concluding remarks <lnd dIrections

F Dolan

i'f

a! fjOWll!Ji oj C(f)I!OIl1!C flfjfC'!O!fl£!,

n

(}~112)

264-277

for fu~ure research. Whilst this framework 15 proving a useful checklist for policy-makers. it has been expmed to only limited

academic scru!:iny to date, and a major purpose of this paper is to fill this gap,

2. The MINDSPACf. frameworl{

'vVe discuss the nine most robust effects on behaviour according to the mnemonic MINDSPACE (Messenger, Incentives,

Norms. Defaults, Salience, Priming, Affect, Commitment and Ego), MII\OSPACE is derived from our judgement of how best

to categorise and group a large body of literarure and behavioural infbences, but there is no specJal significance ~o the order­

ing of the categories - and there is inevitably some overlap between the effects, Table 1 summarises the elements, and the

following subsections expJain each effect in turn.

2,1. Messenger

The welghr we give to informiHion depends greatly on the automatic reaction.:; we have to the perceived a~lthority of the

sourCE' of thdt infonnation - the 'messenger', There is much evidence ti1dt signals of authori ty can generate compliant behav­

iour, even when such behaviour is stressful or harmful. For examp1e. nurses might comply unthinkingly with doctors'

illstruccions, even if they are wrong or fooli""h (HoIling & et al., J 966): and indicators of prestige (e.g, d luxury car) have been

observed to produce grealer deferential behaviour than when the indicators are dbsent (Ooob & Grms, 1968).

There is also evlde!1ce thilt people are mOfe likely:o act on information when the messenger has similar characteristlCs to

themselves (Dur<lntini. Albarraclll, Mitchell, Ea.r!, & GilleHe, 20(6). The 'Hedirh Buddy' scheme involved older studerm receiv­

ing healthy living lessons from their schoolteac hers. The older stJdents then actec. as peer teachers to deliver thar lesson to

younger ·buddies'. Compared with control stt:d0nt:.. both older and yOl..:nger 'buddies' enrolled in this schpme showed an in­

CredSE' in healthy living knowledge and behaviour e.g. with some beneficial0ffects for BMl (Stock et ai., 2007). In the case of

microfindnce, there is Increasing evidence that people <He more J ikely to take credit from peop!ewho are more like them (Karlan

'" Appel, 2011),

Aathority may also be generated through more formal medns if experts deliver it. One study showed ~hat health interven­

tions delivered by research assis: . m

. ts and hedlth educ<1tors were more effective in changing behaviour compared with inter·,

ventio!ls delivered by either tramed facilitators Of teachprs - dnd hcal:heducaror~ were usually more pcrstlasivc th<1n re~earch

assistants (sec Webb & Sheefan. 2006). Thus, this automatic deference to formal sources of authority may be more extensive

and powerful th,1I1 a rational anrliysis would indicdte, and can promp: behaviollr that would :lot take place withoe! the author­

i[y cue.

We are also affected by the feelings we havt~ for the messenger. for eXJ:mple. we m<1y discard advice given by some­

one we dislike ~CialdinL 2007). Feelings of this kinr. may override traditional cueS of dJthority, so that someone who has

developed a dislike, or distrust. of government interventions may be leSS likely to listen to messages that rhey perceive to

come from 'the government'. Those from lower socio-economic groups drC' more sensitive to the characteristics of the

messengcr being similar to them e.g. age, gender, ethniciry, social class/status, culture, profe5~iolt. etc. (Durantini

et aL. 2006), We may also use more cognitive means to assess how convincing a mcssenger is, ror eX<1mple, we will con­

sider such issues as whether there is a consensus across society ('do tob of different people say the same thingT) aad the

consistency across occ"l,>ions {'does the comrnunicator say the same thing in different siruatiollsT} (;(ellp;!. 1g1l7: Lewis.

2007),

Thi<; me<;senger effect is different from a signalling effect: the former is based on credible individuals giving information

which becomes dtrended to, whereas the latter is based on placing more weIght on a pjece of information becau~e ir is Seen

to be true or signals quaHfY about the choice or mformation. The infonnd.tion given by dn effective messenger might not nec­

essarily signal quality but a credible mes<;enger will increa<;e the likelihood thar.1 piece of infOimatlon 'is sern to be true'. It

will also be more likely to be seen to be tr'-Ie when the inform~)tion is sd.tlent. and so signalling will effectively be covered by

different elements of MINOSPACE).

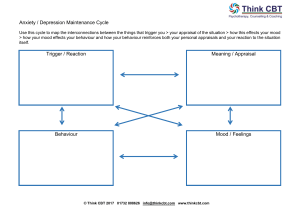

rable 1

fh(' ~1I:-'D::'PAC:, ;'r,,);l!:wt)rk 1'0; r:.er!;)vj,::;r ,h;mge.

MINDS?ACE me

B:;hav;our

Me'i$('ng(',

we ,lIt' h("wlly tft!luen(cG by who (omftL,m(Jtc~ mfmm,1tiofl :r: ",

Our fcsr:emr\~:) Ift~T·nlp.!cs ,.J;C shaped by r~edinab:t' men:a! sh(J;-tCl'f\ sUfh as ~trcn5;Y ilV'3Jdmx !c-\€ s

We ,1rt" \tfongly mfJucHt'ct by w~at others du

We 'So with thp !lew' of pli>S\?t oprjcns

Ow il.Itemic.l I;' dr"wfl to Wr,l; ;s nDw1 a::d ~ei'm_, ft'h;VdJll to (J;;

Om acts Me ;)ftt";: inLul'_'L:ed by SulN':C1l5(l0t15 cut'~

Our ('multOTI;::; ds~o.:iJ.tiOfiS C,;!l rowelf01!y "h,l;:tE em a:::(lnflS

Wf' ~evk to be CQ,1'i11tent wit~ Ol'f pvbltc pror.1sv"" ,1Ild rC'Clpw;:.ll€ Mh

W(' ill: 11 W2y\ (!-lat make uS [0el :'e[((:f abo'.:! DUf\2Iv('\

i:-n-e:lt,vcs

Norm..

D(,f;1Uits

$,dtt'rtfe

rr,mn:g

Com:n,tlT',enis

Ego

~--~

267

22. Incentives

Incentives are central to economics. whose students are taught very early on that "people respond to incentives·'. The eco­

nornic law of demand says that we are sensitive to price'> and co:.ts (Kreps, 1990; Pearce. 1986;. Thus, healthier lifestyles can

be promoted by offering incentives th.1t encourage people to eat healthier foods, take more exercise, drink less alcohol and

give up smoking (Marteau, Ashcroft. & Oliver, 20(9). The impact of incentives clearly depend:; on factors such i.lS the type.

magnitude and timing of the incentive. Behavioural economics suggests other factors can affect how individuals respond

to incentives, which can allow us to design more effectiVe schemes. The five main. related insights from behavioural econom­

ics are thdt:

22.1. Reference points matter

EconomIC theory assumes that "'IH~ care- only ahom final outcomes. EvidencE' suggests that the valut'- of something depends

on whf:'re we <;e-e it from - and how big or smdll the change dppears from :hat reference paint (see Ki.lhneman and Tvt:'rsky

(2000) for a review of the literature). If the utility of money is judged relative to very locally and narrowly determined ref­

erence pmnts, a small incentive cOuld havE' a gr!?at effect (Thornton, 20(8). As possible evirle nee of ttli'>, incentives were used

in Ma!awi to encourage people to pick l:p their HIV result (many do not otherwise): take~up w"s doubled by incemives just

worth one-tenth of a day's wage. This could also be consistent with standard models of diminishing marginal utility but real­

istkally only if determined from a reference point ~of zero in this case as nobody has ever been pJid to pick up a 1:es: result),

and not relative to total wealth (Kdhneman & Tversky. 1979;" Similar evidence of reference point effects i'i provided by Fehr

and Goette (2007) and Crawford and Meng (2011 j,

2.22. [osses loom larger than gains

'vVe dislike losses more rhdn we like gains of an equivalent amoun: (Kahneman & Tversky, 1979), which is due to the ref­

erence point effect outli ned above. lQ<is aversion matters because the decision making process originates from distinct neu­

ral system;;; in the brain (see Tom, Fox, Trepel, & Poldrack, 2007), For example. framing effects are triggered when people

decide to take risks for large gains or to accept a sure loss; and i: is associated with activity in [ile i.lmygClJla a brain area

jrnplic~1ted in processing fear and other aver~ive s:ates, which suggests rhar the emotional sy~tem mediarcs decision biases

(De Martino, K:.Hnaran, Seymollr. & Dolan. 2006), y!ost current incentive schemes offer rewards to participants. but a recent

review of trials of trea~ments for oht'sity involving the USE" of financial incentives found no significanr effect on long-term

weight loss or milintenance (Paul-Ebhohimhen & Aveneil, 2008). An alternative may be to frame incentives as a ch<lfge that

will be imposed if people fail to do something. One recent study on weighr loss asked participants to deposit money in::o an

accoun~. which was returned to them (with a sllpplement) if they met targers. After 7 months, this group showed significant

weight loss compared to their entry weight and the weight of participants in a control group did not change (Volpp, Troxel.

Fassbender. e'l aL. 2008). Thpre needs to he greater evidence on the impact of loss aversion on experienced versus inexpe­

rienced conscmers (see Lisr. 2004).

2.23. We overweight smal1 probaiJifitiE's

Economic theory dSSt;meS that we treat changes in probability in a linear way - the change from 5% to 10% probability is

treated the same as the change from 50% to 55%. [vioence suggests. however, that people place more weight on small prob~

abilities than theory suggests (Kahneman &. Tversky, 1979. 1984) we ovef\'\'eigbt change~ in prob<lbihty moving from cer­

t"inty to enceltainty more than intermediate change,S.ln particular, we are prone to overestimate the probability of enlikely

hut easy to imagine or recall events, such "s winning the lottery. This opens the door to encouraging gambling, but can also

be u<;ed for potentially more positive effect, such as lottery-b"sed savings products (Tufano, 2008). Similarly, people are

Hkely m over-emphJ:si')(' the small chance of. say, being audited, whlCh may lead to grea:er tax compliance than rational

choice models predict.

More rect:'nr attempts to model some aspects of probability weighting utilise the accessibility framework (!<dhneman,

2003.), 2003b). according to which probability j~dgements are based ali the i.lmount and intensity of the inform<ltion ac­

cessed. In the domain of risk, for ex.ample, cer,ain tns~lrdble ("Vent'> are encountered in evelyday life more frequen~ly from

per",onal experience, TV, newspapers, advertisements and convcfsations, which m'1Y jnduce mistaken feelings that some

sorts of ri<;k are more frequent {l'.g" LiChtenstein, Slovu:, fischhoff, laymdn. & Combs. 1978}. Kusev. VJl) Schaik, Ayton. Oem,

<H1d Chatel' (2009) demonstrate greJ~er risk-.wersl' behaviocf for more accessible fisks, which implie'i [har. when making

risky decJ'iions, human preferences afe affected by the accessibility of events {and their frequencies} in memOly even after

outcome values dnct probabilities are known. The fitted probability-weighting function tbat explajned the data exhibired

greater risk aversion, which was caused by over-weighting when the insurance decision scenario<; are related to more ')cces­

sible h,]lJrtlfhlS events In mernoly. Such effees of the can text of thl' (risky; event on percep:ions of probability have obviot: 5

implications for influencing behaviour in more natural serrings. For example, me~ja campaigns CJ.n incuce feelings that some

~orts of risl( are more ffequent by pre~enting examples of real cases of fatal outcome;. (e.g .. Cdncer deaths cJl:sed by smok­

ing). Such vivid. freqllemly encountered cases (not just general information) wilt affect perceptions of vulnerability, because

hutndn judgments are often constructed hy sampling exemplars from memoty or the environment (Stew,lft Chdter, &

Brown, 2006).

2,,8

P Dolan er al.!Jourfwl oj' fccrJlJ':1U PsyriwlDgy 3) (29[2) 264-277

2.2.4. We allocare money to discr{'te mental accounts

We thmk of money as silting in diffcrent 'mental budgets' - s?ilary, savings, cxpenses, elc. Spend.ing is constralDed by the

amount sitting in clfTerent accounts (Thaler, \999), and we aft' reluctan: to move IllOney between such accounts . .\tIental

accounting mC,1I1s that idemical incentlve~ vary in their impact according to the context: people arc willing to take a trip

to save £5 off a (I5 radio, but not:o save £5 off a refrigerator costing £210 (Thaler. 1985\ This means that policies may

encourage people to save or spend moncy by explicitly 'labelling' accounts for them, without rernoving their control over

exactly how the money is used. For example. there is evidence from the UK thCit the labelling of a partlcu!ar benefit as a

"Winter Fuel Payment" led to significamly more recipients ~pendjng the money on fuel than if it had been treated as cash

(Bedtty, Blow, Crossley, & O'Dea, 2(11).

2.2.5. We inconsistently live for roday or [he expt'nse of tomorrow

We usually prefer smaller, more immediate payoffs to larger. more distant ones. (10 today may he preferred to El2

romorrow, But El2 in 8 days may be preferred to £to in a week'!, time. This implies that we have a very high discount rate

for now compared to later. but a !O'./ver discount rate for later compared TO later still. Th.i'> 'hyperoolic discounting' {uibson,

1997) leads people to discount the future very heavily when sacrifice5 are reqt:ired in the present for example, to ensure

improved environmental o:Jtcomes in the future (Hardisty & Weber, 2009). McClure, Laibson, Loewenstein. & Cohen, 2004;

McClure. Ericson, Laibson, Loewenstein, 8; Cohen, 2007) report ne~lrobiological evidence that competing neural valuation

systems. one with a Jow discount rate and one with a high discount rate, determint? chOices between immediate SOlan mon­

etary payoffs and larger but delayed payoffs. In behaviour change, there is evidence that the imme<:!iacy of reward has an

impact on the succe')~ of schemes to treat substance misuse (lussier, Heil. Mongeon, Badger. & Higgins. 2006;.

'These five aspects of incentives are discussed and differentiated: from the standiirc economic modet in DellaVigna (2009~

It is dear that [here is a great deal of good fielc evidence for these five effect~. and these ;.mderpln the main texts in :h1s area

(see Aril"!y, 2008; I(;;hneman & Tversky, 2000, Thaler & Sunstein, 2008;.

2.1 Norms

Social and cultural norms are the behavioural expectations, or rules, within a 'lodery or group, or alternatively a standard,

customary, or ideal form of behavior to which individuals in a socia! group II)' to conform (Axelrod. 1986; Bt"rke & Payton­

Young. 2011). Social norms can influence behaviour because individuals tiike their clles from what others do and use their

perceptions of norms as a standard against which to compare their own behaviour.> (Clapp & McDonnell. 2000;. The oper·

arion of socia! norms is at least partly conscious: conformity may be a deliberate strategy. <;ince we may obtain pleasure from

choo"ing to behave ilke everyone el'ie - even though this choke may nor be maXimising overall utility

There drC'. however, at le£lst two argcITIent5 that the effect of social norm:. h.1S J powerful automatic component. first.

there is evidence that those engtlging in conformist behaviour demonstrate no awareness of having beel! influenced by

the beh£lviour of others (Chartrand & Bargh, 1999). Second. social nonn'i can lead to beh£lviour that is difficult to eXDl£lin

in :erms of 'rationality'. A well-known illustration of this is provided by Latane and Darley:" 1968; finding that the presence

of inactive people strongly reduced the probability th<1t a subject would act In an apparently dangeroJ.:s situation. What is

key for modelling the likelihood of social norms impacti ng on behaviour is that social norms induce a positive feedback loop

in behaVIours, where the more Widely :hat , 1 norm is followed by members of a social group, the more everyone wants to

adhere to it (Burke & Pay;:on-Young, 2011~. The exogenous impact of social norms has been used by economists tn areas such

as energy use (AHcotL 2011). ch.'lI"itable giving (Frey & Stephen Meier. 2004), votmg (Gerber & Rogers, 2009), retirement sav­

ings (Oliflo & Saez, 2(03) and employee effort (Bandiera, Iwan, $;; !mran. 2006).

We draw out fou: main lessons about norms. first. if the norm is de'<;irable, let people know about it. In seatbelt use, the

'Mo~t orus Wear Seathclts Carnpaigo' used a sod..1 norms approach to incred<;e the number of people using seatbelts, Initial

data collection 'ihowed thar individual:. underestimated the extent to which their fellow citizens used seathelts either as

drivers or passengers; although 85% of respondents to a :,urvey used a seathelt. ~heir perception was only 60% of other cit·

izen:; acults did, An imensive social norm'> media campaign was lacnched to inform residents of :he proportion of people

who used .;,eatbelb, and the self-reported use of seatbelt significantly increased :Unkenbach & Perkins. 2003).

Second. relate the Ilorm to the target audience as much as possible. In recycling, when a hotel room contained a sign that

asked people to recycle their rowels to save the environment, 35% did so, \t\then the sign used soria I norms and 'i,lid that most

guests (It the hotel recycled their towels at least once during their s:ay, 44% complied, And when the sign said that most pre··

vious occupants of the room had reused towels e1t some point (',urlng their stay, 49% of guests also recycled (Cia!dllli, 2003;.

In finance, it seems that the behaviom ofvisible work colleagues (Duno &. Saez, 20D3; Jnd neighbo'..lr'i :Karl<lll, 2007~ impact

financial deciSIOns.

Third. norms may need reinforcing, In energy conservation, a C'S energy comp<lnY, OPower, sent statements that provided

social comp..'lrison') between a household's energy use and that of its neighbours (as well as simple energy consumption

information). with smiley faces if consumers were below the average (which also includes affect). Thf' scheme was seen

to reduce energy c:ms~mption by 2% relative to Ihe baseline. Interestingly, the effects of the intervention dE'\ayec'. over

the months between letters <lnd increase<. again lipan receipt of the next letter (Alicott. 200fl),

fourth. descriptive norms can backfire when people hear that otheIs are behaving worse thJn them. for example. when

household<; were given information about average energy usage, thost"', Who consumed mort' than the average reduced their

consumption - but thost' who were con')ull1ing less than the average increased their consumption This 'boomerJng' effect

260

was eliminated if a happy or SJd face was added to rhe bill, thus conveying sodal approval or disapproval (see the role of

afTect below) (Schultz, ~olan, Cialdini. Goldstein, & Griskevicius. 2007).

In line with wider literature on the power of automatic channels of influence, there is considerable evidence that it is

'declarative' norms thilt do much of heavy Jjfring - in other words, we are influenced more by what we seE' or think others

arE doing rather than norms chat refer ro what we 'ought' to be doing rCialdini. Kallgren, & Reno, 1991). Such declaratIve

social norms may affect behaviour through various channels, For example, norms may provide a genuine signal about whdt

others have found to be the best option - a toerist might be wise to choose rhe busy restilurant oYer that no-one clse seems

to be in. Following tht: behaviour of others may aha give us diren pleasure tbe feeling of being a part of the latest f.1shion

or the <in-group' wirhout necessarily maXimising overail utility.

2.4. Dtjaults

'-lost decisions have a default option, which is rhe option [hat wUl come into force it no aerive choice is madot. Defaults

exert influence as indiViduals regularly accept whatever the Gefault setting is, even if it. has significant conseqL:ences. Many

public policy choices have a no-action defaclt imposed when an individca! fails to make a decision. Defaults 11ave been re­

lated to various factors such as hyperbolic discounting (O'Donoghue & Rabin. 1999), 10s5 aversion (Kahneman & Tver'1ky.

1991) and pres~lmed 'suggestions' that imply a recommended action (johmon & Goldstein. 20(3). The reason we disc!.!;;s this

principle as a separate category is because we aim to jllustrate hO\v defaults are used to influence behaviour rather than as a

claim about the underlying meChdni'ims (which may differ across contexts).

Structuring the default option to maximise benefits for citizens Cdn influence behaviour without restricting individual

choice. For example, in an attempt to increase pension uptake, a US corporation switched their default from active to allto~

millie enrolment. introducing automatic enrolmem into the scheme significantly incre,vied participation but. interestingly.

was also seE'n to eliminate most of the previo!.!5 differences in participation due to income, sex and race. The increase in up­

take was partIcularly large for low and medium income workers (Madrian & Shea, 2001). dnd has been found in further sttld~

ies {such as ChoL wihson, Madri,m. & Metrick, 2004: Cronqvi:;t & Thaler. 2004). Following suit, the 2008 Pensions Art has

changed the default in the UK: from 2012, employees will be automatically enrolled in a pension plan. hur still have the

opportunity to opt-out if they wish.

Such powerful effE'et of defaults on bellavio'.1r ha:; been ob~erved in a wide range of other settings likE> organ donation

decisions (Abadie & Gay, 2004; Johnson & Goldstell1, 2003). choiCE> of caT insurance plan ~Johnson, HE>1"'1hey, tvTesuros, &. I<un·

r<'~l!tht>r. 1993), car option purchases lPark. Jun. &. MacInnis, 2000), and health care (e.g.. an optMour policy of routine vacd~

nations and routine testing of pa:ient<; dnd health care worker,,; Halpern. Ubel. &. Asch, 2007),

The optima! default depends on the population being analysed, if people have highly heterogeneous choices, then defaults

mdY not be optimal. and mUltiplE' equilihrla could arise (CarrolL ehoi, l.aibson, MadridJ), & Mftrick, 2009). it is still undeilf to

what extent active decisions shadd be used instead of defaults, and what changes behaviour in a way fhat maximises their

lifetime :JtiiiIY. For policymakers. an attractive compromise Cdn be the use of a 'prompted' or 'required' choice - in effect

removing the common defat.:lt of making no choice at aiL For example. from mrd-2011. on-line applicants for UK driving

licences will need to answer a question on organ dondrion, and it is estimated th,lt this is likely to roughly double the number

of people joining the organ register through rhis route.

25. Salienre

Our beh,wiour is grearly influenced by what our a~ten~ion is drawn to (I<ilhnemJn & fhaler. 2006;. Atten!ion C.::in el::her be

voluntarily controlled. or, it can be captured by some external event (Pa'jhkc 1998). The latter type of attention is referred to

as exogenous, botiom··up. or s[in1Ulu<;~drive!1, and a separa.;-e neuropbysiological mechanism is. devoted to processing sdlient

events when an dtren~iondl switch or behavioural switch is elicited (Zink, P<1gnoni, Martin, Dharn<\Ja. & Bern:.:, 2003; Zmk.

Pagnoni. M.1rtin~Skurski. Chappelow, & Berns. 2004). In on everyday lives. we are bombarded with stimulL A.. a result,

we tend to ul1consClocsly filter out much information as d coping strategy. People are more likely to register stimuli th~'lt

are novel (messages in flashing lights), at.:('I;ssible ~jrents on sale next to checkoetsJ dnd simple (a snappy slogan) [e,g"

see Houser. Reiley, & Urbancic, 2(08). Simplicity b important here beGIU'>e 0\11" attention is much more likely to be drawn

to things that we can understand - to those things that we Cdn easily 'encode'. For example, we a.re mud1 more likely to be

able to encode things that are presented jn ways th<1t relate dIrectly to our persond! experiences (e g., frequencies) than to

things presented In a more general and abstract way {Clgcrenlcr & Hoffrdge, 1995).

Beh<wiour cliange studies have demonstrated that information is taken into ,1Ccount only if it j,> salient. For eX<'nnple,

Mann and \iV."He! (2007) reveal tha~ when attenrional or cognirive reso:Jrces are restricted, individuals can focus only on

the mO.')~ sdlienr hehavioural cues, which leads to actions that are under the motivational influence of rhose cues. [n partic­

uliu. the partidp<lH:S were more likely to respond to health-promoting messagE's and exhibit signifkartly more self-control

when sdlient. anc attenLlfm-grabbing, cues suggested restraint in the domains Df eating. smoking, and aggression.

MoGels of attention in psychology disC1S$ voiantal)' and involuntary attention (where the latter is largely unconscious)

whereas ewnomists have focussect largeiy on conscious attention where the alJorarion of attention is voluntary {see (hetty,

Looney, & Krofr, 2009). This is, however, beginning to change. For example, in a recent US experiment researchers chose 750

products SL:hjecl to a salt'S tax thin is normally only applied at the till. and put additional labeL" neXT to the product price,

showing rhe fL:1l <1mount indading the tax. Putting the tax on the label, rather Than adding it at the till. Jed to an 8% fall in

no

P. Dolan £'; a l Jiot'fIla'

:;J EnHu.])!( PSyctwlflgy ]] (lOU) ~'r>4-271

sales over the three-week experiment, In additIOn, iT has been shown tha~. over a 3D-year period, taxes rliat an?' included In

posted price') reduce alcohol consnmption signific2mtly more tban taxes added at the register (Chetty et a1" 2009),

When making ,1 decision, we often lrtck knowledge about a topic {for example, buying a DVD player}. Experiments show

that we look for an initial 'anchor' (Le. a price for a DVD player) on which to hase our decisions. For example, it has heen

shown thar the minirnum payment amount on credit card statements attracts our attention ano 'anchors' our decisions.

When a credit cird statement had a 2% minimum payment on it. people repaid £99 of a £435 bill on average: when there

was no minimum payment. the average repayment was £ 175. In other words. pre')enting a minimum payment drdgged

repayments down (Stewart, 2009). The power of anchors is such that they work even lf they are tatdlly arbitrary, If people

are dsked to write down the last t:\\'o digits of their social security number, this 'anchors' the amount they bid fot items and

theil' E'stimates of historical events - E'ven though dedf[y there is no logical connection between the two (Ariely. Loewen~

stein, & Prelec, 2(03).

The implication of such findings IS that interventions Cdn change behaviour by m.lking important dimension') salient. Thl~

is illuslrated by Dupas (2009) in a field intervention testing Whether inform,ltion on HIV risk can change sexual behaviowf

among teenilgers in Kenya. Providing information on the relativ~ risk of HIV infection by partner's age group led to a 28% de­

crease in teen pregnancy and 61% decrease in rhe incidencE' of pregnancies with older, riskier partners~ In con~rast, there Wd:"

na statistically signi Ikant decrease in teen pregnancy after the introclJCtion of the national HIV educatioi1 curriculum. which

provided only general information <lbout the risk of HIV and did nor fOCuS the message on the risk distribution in the popu­

1ation. By making the age of pdrtner saliel\(, the intervention reduced a complex multi-atnibute choice dilemma to a heuristic

decision base<! on one ')aiient attribute/cue, which enabled the teenagers to selecr beh,wioL.fs that improve their welfare.

2,6. Pn'millg

Priming (or activation of any sort) of knowledge in l11erl101Y makes it more accessible and theret{)fe more inO'Llcnlial in

processing new stimuli (Hichardson-Klavehn & Bjork. 1988). Depending on [he natme of the td<;k, [here could be percep­

tualjattention, motor/action, or semantic priming respectively (LaBf'fge.& Buchsbaum, 1990; Strack & Deutsch, 2004). Prim­

ing shows thdt peopJe's linet behavio;Jr may be altered if they are fir~t exposed to certain sight::;, words or :;ensdtions (Batgh,

2006; B.1rgh & Chartrand, 1999: Williams & B<lTgh, 2008). In othf:'r words. peopJe hehave differently if they have been

'pflmed' by certain cues beforehand. Priming seems to act outside of consciocs aW':.Heness.

Many Things C4n act as primes, First words. Exposing people to words relating to the elderly (e.g, 'wrinkles'1 meant the)'

subseqeently w<1Iked more slowly when leaving the room and hJd d poorer memory of the room, In other words. they had

been 'primed' \'\:,ith dn elderly StereOlype and behaved accordingly {Dijksterhuis & Bargh, 20(1), Asking pcll'ticipanr<; to make

a sentence out of SCf ambled words such as fit, lean, active, nth/etfe made them significantly more likely to ;Jse the stairs. in­

stead of lifts (Wryobeck & Chen, 2003). Priming words such as collaborare, trusf, s!wre and teamwork befOie a public good:;

g,1liiC significantly incre~1sed contribution'> to [he public good ~Drouve!is, :\1etcalfe, & Puwdthav!:'e, LOW). Priming can even

occur by simply asking people what they intent.! to do, because such question<> alter the ease of recaJling and mentdHy rep­

resenting the new behaviours, Levdv and Fitz.simons (2006) demonstrated thd:: asking the participants to indicate the like­

lihood of flossing thel r teeth in the coming week significantly increased the frequency of thi~ behaviour over that period.

Secane., sights. If d happy face is subliminally presented 10 someone drinking, it caU<ies them to drink more than those

exposed to a frowlling: face (\Vinkleman, Berridge, &. WilbaIger. 2005), The size of food container~ primes our subsequent

eating, Moviegoers arc 45% more popcorn when ir was given [0 thf'm in a 240 g container than a 120 g container: even when

the popcorn was stale, the larger contiliner made them eat 33.6~£ more popcorn (Wansink & KiI1l, 2006:·. Deliberately plaring

cet::'ain objects in one's environment can alrer hehaviour - 'situdtionaJ cues' like walking .,hoes and runner's magazines may

prime a '"heaLthy lifestyle" tn peDple (Wryobeck 8; Chen, 2003), while placing.1 poster of eyes above an honesty box where

people can geT coffee or ted makes them pay three times as much fot their c,nnks (Bateson, Netrle, & RoberLs, 2006) In this

WdY, priming can reinforce existing intentions to act in d certain way. Vahs, Medd, and Goode (2006) report reI-ned evidence

that partiCIpants primed with money ta st,lCk of \IlonoPQly money in ViSlI,11 periphery or scrcensavers showing money),

whkh prompt concepts related to rational economic f>xchdnge and self-sufficiency, are less willing to volunteer to help an­

other p('r~on. donate less, prefer to work alone and selecting more individt;ally focuset; leisure expenences.

Third, ~mells, Mere exposure to the scent of dn dll-purpose cleaner led significanrly more people to keep their cable cleJo

while eating in a canteen (Holland, Hendriks, & Aans, 2005). Bt'ing exposed to plea'>am, neutral or unpleasant smell!> below

the lew I of cOI1)(tom derection significantly influenced subjects' rilting of the likeability of faces they subsequently saw

(Li, MOdllem, Pd!!t:r, & Gottfried, 2(X)7;. Similar re'>e.1r(h on consumer behaviour suggests that odm:rs ionease gambling

in casinos (Hir'>ch, 1995) and Intentions to vlsit aston: (Sp.11Igenb":Ig, Crowley. S. Henderson, 1996;,

What IS Ies::. enders rood is which of the tho'Jsands of primE's that we encounter every day hdve a '>igmllcant effect on our

uehaviour, For insrance, it has been found thdt using;) credit card primes humans to spend mOtE dnd spend faster (Feinberg,

1986), and impaCTS on O'Jr willingness to pay for normal goods (Prelec & SimC'srcr, 2(01), A field experiment showed that

criminal activity can be made more likely hy factors in the environment that 'pt ime' an offender'S behaviour. The broken win­

dows tl/Cery suggest" thar if a few windows of a dereHct facwry were not repaired. rhe tendency was for Vandals ro break a

few more. In six cootlolled field experiments ir h<ls been defllOI1Srra~ed Thar graffiti or litrering can indeed encourage allot her

behaviour like stealing because 'when people observe then others violated d certain social norm or legitimate rule, they are

more likely to violare ether norms or ruk~s' (Kdzer. Lindenberg, & Steg. 2{J08;'

27:

When priming is linked to limited attention, it is conceivable that a great deal of the decisions in 0111" lives might be made

without u" consCIously knowing <lbout them (Wlison, 2002). The fOCllS of OUf attention cart in some be unconscious too - we

artpnd to things wirhout knowing it (Morewedge & [(Clhneman, 2010). So, seemingly ot:t of the blue, we might fancy a pizza.

not recognising that our desirE' has been triggered by the billboard of ri new menu available at a pizza ehai:! (KE'ssler, 2010),

2.7. AJJm

Affect (the act of experiencing ('motion; is d powerful force in decision-making. Emotional responses La words, IfTlages

and events can be rapid and automatic, so that people can experience a behavioural reaction, and also use emotional eval­

uations as the ba.,is of decisions, before they realise what they are reacting to and before cognitive evaliiation takes place

: Kahnemao. 2003a, 2003b; Slavic, Finucane, Peters, & McGregor, 2002).lr has been arg~led that aU perceptions con:<'Iin some

emotion. so that 'we do not just see a house: we seea hand!>ome hous/;", an ugly house. or a pretemiou<; house' (Z<'Ijonc, 1980),

This means that many people buy hoases not because of floor size or location, but oecause of the viscera! feeling they get

when walking through the front door ~ and mayor may not make a better deciSIOn as a comeGuence {Oijksterhuis, Bos,

Nordgren, & van Baaren. 2006;.

Emotional, rather than deliberative, responses can drive financial decisions, In one experiment, direct mail advertise­

ment<; for loan offers varied in the deal offered, but also in elements of the advert itself, It was found that the actual adver­

tising content h<'ld a ')ignificant effect on take up of loam, rather than just prices. Including a picture of an attractive female

increased demand for a 10,10 by the same amount as a 25% dccreasp in the interest rate (Bertrand, Kar:an. Mullainathan,

Sh?!fir, & Zinman, 20W). Similarly, Gibson (2008) show that conSlimer brand choice can be changed by repeated pairing

of positive or negative words and images wIth a brand.

Provoking emotion has been shown to challge health behaviours too, At~el1lpts to promote soap use In Chand were orig­

inally based around thl" benefits of soap - but only 3% of mothers washed hands with SOdP after toilet use. Researchers noted

that Ghandians used SOdP when they felt that their hdnds were dIrty (e.g., Jfter (Ookmg or ~ravelling), that hand-washmg Wd.\

provoked by feelings of disgust. A<:, J result, the intervention campaign focused on provoking disgust rather than promoting

soap use. Suapy hand w<lshing WdS shown only for 4 s in one 55-s television commerdal. but there was a clear message that

toilet use prompts worries of contamination .lOd disgu'>f. and reGuires soap. This led to a 13% increase in thE' I,.:se of soap dfter

the toilet amI 41 % increase in reported SO<lP use before eating (Curtis, Garbrah~Aidoo. & Scott. 2007;. Judah et aJ (2009) pre­

:o.ents evirlence that inrervention messages provol<ing disgust can improve hand-washmg in western society too. Further evi­

dence during visceral states, such as hunger, has sllOwn that they can change consumption decisions (Read & van Leeuwen,

1998), Lerner, Small, and Loewenstein (2004) found that di"gust ;md sadness (induced by.'\ prior, ilTelevant sit<Jationj re­

duces selling prices for norm.,1 goods, Moreover, emotions have also been shown to imp.1Ct on choice') over short and long

time horizons (Loewenstem, 1996) and decisions l;nder uncertainty (l.oewPl1stein. \Veber, Hsee. & Welch, 2001). These re-­

'i1.llts demonstrate that incidental emotions can influence decisions el/en when real money is at st<lke, So con:-exts can induce

dffen, which then impacts upon the price>; u'ied in the nlarket place. These prices might then anchor ihe prices for orher

goods <'Ind have profound effects on the economy (Anely et al.. 2003).

2.8. Commirment

We tend. to procras~inate "md delay taking decision" that ale likely to he in our long-term tnterE'sts (O'Donoghue &- Rabin,

199(3). Many people dre dware of their will-power weaknesses (such as <1 tendency to overspend, overe<lf or continue smok­

ing) and use commitment devices to achieve long-term goals (Becker & Mulligan. 1997). So pre-t:ommitrnent in itself might

be a rational reflective action, even if the subsequent effect'> of commitment deVices operate mainly on the automatic system

(e.g., aL:tomatjc fear of being excfude(; from the group <'IS a result offailure to snck to one's publicly made commitmenrs and

n:puration damage, Bicchien. 2(06). Fnr example, one major study designed a commi~ment savings pr<x:iuct for J Philippine

bank. which was intended for individuals who want to commit now to re$~riG access to their savings. It turned out That Phil­

ippine women (who are traditiollally responsible for hO;J.sehold tinanr:es Jnd in need of finding solutions to temptatinn prob··

lems) were significantly more likely to open the commitment savings account Ihan men (A<;hraf, Karlan. & Yin, 200B), On the

whole, the product significantly increased savings.

It has been s.hown that commitment:. usually betome more effectlw <15 the costs for failure increas!? fndeed, p!?ople may

often impo<:;e penalties Oll themselves for failing to act according to their long-term goals (Trope & Fishbadl. 20(0). Students.

for eXJmpli;, drC' willing to self-impose costly deildUnes to help them Overcome procrastinJtion (Adely & Wertenbroch,

2002). One common method for increasing such costs is to mJke commitments public, since breaking the commitment will

lead fa significJnt n?putationat damage. These principles have been applied to help smokers quit. Individuals were offered a

savings dC(ollnt in which they deposi ted funds for 6 month:>, af::er which they rook a rest for nimtine, If they passed the test

(no presence of nicotine) then the money was returned to them. othefiNise their money WdS forfeited (Gine, l(arI3n, &

ZlnnBIl, 200ii), Su~prise tests dt 12 months showed an effect on las~jng cessation: the savings account commitment in~

creased [he likelihood of smoking cessation by 30%.

~everthele<.;s, commitment devices do not depend on tangible penalties or rewards for their behavioural effects. EVen the

very Jct of writing a commitment call increase the likplihood of it being fulfilli?d, and commitment contacts have alreddy

been H~ed in some publk policy arCdS (CiJldim. 2007). To increase physical exerdse. commitment tc achieving a symbolic

272

goal (such as 10,000 steps a d.ay using a pedometer) appear" to significantly increase success. An experimental study com­

pared two group,>; one group signed a contract specifying the exerciSt:, goals to be dchieved whilst a control group were sirn­

ply given a walking pr:'}gramme bur did not enter any .agreement or sign a contrdct. All participants recorded daily walking

aCiiv1ry for 6 weeks and the contract group were significantly more likely to achieve their exercise goals ,:Wllliams, Bezner.

Che"bro. & Ledvi~t, 2(05). This needs further research, and e'ipeciaUy whether rhe outcome of ::be targets matter, such as

whether money b useC, and to whom the goes {see Burger & Lynham. 20 to).

A final .1'lpect of commitment is ~he importancE' of reciprocity. Vve have <1 very strong instinct for reciprocity. which is

linked ~o a deslr..: for fairness that em lead us to dC: irrdtionally For example, people will refuse an offer of money if they

feel it has been allocated throLgh an unfair process and when by refusing they can punish the person who allocated it un­

fairly (GGth, SchminbergeL & Schwarze. 1982), We can see ~hl? desire for reciprocity strongly in the attitude of ''I'll commit to

it if you do", ReciprOcity effects can mean thar. for (*xampll? accepting a gift acts as d poweftul commitment to return the

favouf at some point. which lS why free samples afe often effective marketing tool, (CLaldini, 2007),

We t€'nd to behave in a way that supports the impression of a positiVI? and consistent self-image, \Vhen things go well in

om lives, Wf' attrihute it to otlrselves: when they go bacly, it is the fault of other people, or the situation we were put in an

effect known as the 'fundamental attribution error' (Miller & Ross, 1975). Our desire for positive self-image lec.ds [Q an (often

automatk) tendency to compare ourseJves ag<linst others and 'self-evaluate' (Tes~er, 1986). \Vhen we make these compar­

isons, we are biased to hE'lieve that WE' perform bet;:er than the average person in various ways: 93% of Americdfi (allege

students rated themselves dS being "dhow dverage" in ddving ability (Suls, Lemos, & Stewart, 2002; Svenson, 1931).

Vole thmk the same way for groups that we identify with. Psycho!ogis~s have found this group identification to bt" .1 very

rohust effect, and ir can cbange how we see the world (Hev'/stnnt', Rubin, & Willis, 2002). The dassit: illns:riltion of this effect

is sports fans' nH'mories of their team's performance in a match. F.:ms sY'1tematic<1!!y misrememher, and misl1lterpret, the

behaviour of their own team compared v,fith the opponents. A match ill which both teams appear equally culpahle of com~

mitting fouls to an impartial observer will be seen by a parri.al fan as one chdracterised by far more fouls hy the opposing

team than their own (Hastorf & Cantril. 1954),

Adveltis(;'rs are wt>1I aware that we vit>w the world through a set of attributions that tend to m<1ke us feel better "hout

m:rselvE's (Tajfel &' Turner, 1979). Male responden~s conare more to charity when approached hy more attractive female

50lidtors for door~t(}·-doo( fund-raising, which sugge<;ts thdt giVing i.<, also the result of a desire to mAintain a positiVe

seif-imJge (in the eyes of the opposite sex in this case) {Landry, Lange, U,>t, Price, & Rupp. 2006), This suggests that, for exam­

pi..:, attempts to reduce smoking should conslcer if smoking is bound up with a deSire for self-esteem and positive

self-image, which mean'> self-esteem may he an effective route for change (pointillg out that smoking causes yellow teeth

And impo:ence) ~Gibbo!ts & Btilnton, 1998; Gihbons, Cerrard, Lane, Mahler, & Kulik, 2005). Of course, this is not a hlanket

prescription - for people with wry low self-esteem, a more effective route may be to build their sense of '>elf~efficacy,

'oNe <lIsa like to think ofourselws as self-consistent. 50 what happt'm when our behaviour dnd ollfself·-beliefs dre in conflict?

Intert>stingly, often it is our beliefs that get adjw.tec, rather ihan our behdvioar (Festinger, 19-57). The de~jre for consi;;;tency is

used in thefoot~inMthe,door technique in marketing, which asks people to comply with a small request (e.g. fillingin a short ques­

tionnaire for free). which then leads ro them complying with larger and more costly requesrs (e.g., buying a related product)

(Burger. 19(9). Once they have made the initial small change to their hehaviour, the powerful desire to act consistently takes

over the initial action dldnge<; their self -image and gIves them reasons ror agreeing to subsequent reque~ts C-I did th<lt. so 1

must have a preference for the:;e products'"}. In other words, small and easy changes to hehavio:'lf can lead to subsequent

changes in behaviou- ~h.1t may go largely unnoticed (Hem, 1967). This has <llready been shown forpolitica! preterences dnd vo~109 over tn1H;' (Muliainathan & Washington, 2009). This approach chilllenges the common belie! that \'I;e should first seek ~o

change Jttiludes in on:!er to change beh,lVio'JL Similarly. It has been shown that the greater the expectJtion placed on people,

the better they perform, known as the 'pygmalion eHect(RosenthaL 1974; Rosenthal &J..1cob<;on, F"i92).

People's ego could change the demand for certain goods basec on the other behavionral effects mentioned dbove. We

might change OHr energy consumption hecause of $ocial norms, but then the ego oJmpounds on this behavioural bias. Akerlof

(.:W02; suggests that these behavioural procC'sses dre important to macroeconomic variables such as S3.Vlflg and poverty.

3. Applying M!NDSPACE

The vas\: majority of public poltcy dims to change or shape our behaviour, anc. policy-makers have various means of doing

so, The iVll~DSPACE framework (an be used when..:ver behaviour change is being considered, including when considering

how beSet to enforce existing or new legislatIon. Speculatively. for example, incentivE'S, norms and salience could all be used

to help to make existing laws <lround not serving alcohol inappropriately work better - at the momen~. there IS flO incentive

to enforce tho: law, no norm behaviour and the law is surely far from bemg salient to many lanclords dnd bar stAff.

We have foc'Jssed most of our diSCUSSions on how to mAke less coerrive policies - softer nudges work better. Public

policy "disa<;[ers" h.we often been attributed to a failure to obtain or apply eVidence abo'..lt how indiv[dudl;; are hkely to be­

have in re"ponse to the initi,ltive (Lewis, 20tH; NJlioll<ll A!..ldit Office, 2006). Arcortiingly, the MINDSPACE frameworlL1!ms to

r. odo;; ('( dtrJ():,mal

or i:CO;Jor:1!C Psychology JJ (20t2; 284-27?

give policy makers a better unders~anding of how (for eXilffiple) people respond to incentives dnd \''t.'hich (ypes of information

are $djlent The logic here is that if government is alreadY <lttempting ro shape behavjOl~r, it should do so dS effectivelv as

possible. and MINDSPACE can help.

MINDSPAC£ also enables polky··makers to understand the ways in which governmenr ilctJODS may oe changing the

behcwlour of citizens unin~en~ionally. For example, it hds been remarked that some priming effez,ts operate in ways that

many people find surprising or difficult to explain (Bargh & Chilrtrand, 1999). Indeed, it is G.uire possible thatthe state is pro­

deICing unintended - and possihly unwanted - changes in behaVIOur. The insights from \1INDSPACE offer a rigorous way of

reassessing whether and hoV'.' government is shaping the behaviour of its citizens. Our hope is lh.at M!:-.IDSPACE will allow

policy ma.kers to consider the 'behaviourCiI dImenSIOn' of all govemment action in it more sophisticated and informed way.

The fr<1m~work can also be applied to improve the process of policy-·making itself. /'\s has previously been noted, those

who work in government bureaucracies are not immune to the effects set out above (jdnis. 1972; Suth~r!and, 1992} for

example, it is quite possihle th.at loss aversion .and menta.l accounting may contribute to the lack of innovJ.tive reallocations

of budgets, Notably, the main guidance for appraising policy options issued by the UK Government now l!1cludes d section

that aims to counter 'optimism bias' {Her Miljesty's Treasury. 2003). The MfNDSrACE fr.amework.attempts to increa'>e <1ware~

ness of the effE'cts of s!milar heuristics.

This paper does not seek to provide a detailed discussion of how to integrate the MINOSPACE framework into policy mak~

ing but we would like to emphasise two main poin~s. First. although we have proposed our framework as a 'checklht', it is

clear that to influence behaviour E'ffectively requires more than an acknowiedgement of the power of (for example) defaults.

The context ill which people behave shapes the options that are <waildble lo them .OInt'. ~,ffects their ahility to select these

options. Infr"str'Jcture, prices and spatldl factors are all likely :0 dffect behavio:Jr significantly, and need to be given due

consideration.

Second, there is the need to prod'.1ce .and analyse data on the effectiveness of atrempts to influence behaviour. Saine of the

f<Krors that influence behaviour.are fairly obvioWi .and edsy for government to influence; others are more difficult to establish,

Most importantly, i: can be unclear or uncertain how the various effects will inter<lc~ in specific cases, which means that ro~

bust evaludtion of interventions I'> cruciaL in pdrticuiar, m;.Jch more can be done with fieJd experiments, which have been un­

der-,Jsed in research into behaviour change bu;: have the potential to E'stabli;,h the undeflying causes of changes in bel1dviolJf

(Harrison & List, 2004). 'Whatever the pred"e details of the st0dies, we argue that there should be greater colldboration be­

tween policYMmakers and academics. There has been enormous progress through analysiS of secondary data and lab experi­

ments, and the time is ripe- to enhance the evidence base by t~lking control data in a real world environmenLlndeed, the same

rigo'Jr ChilL is used to eVdluatc the effectiveness .and cost-effectiveness of health technologies and. increasingly, public health

interventions must be applied to behdviour change interventions. The recent contributions from List :20J 1) and ludwig,

Kling. and Mullainathan (2011) :.ho0ld provide dcademics and policy official" with a greater understanding of implementing

such research In the field,

4. Discussion

We have setout what we consider to be the most robust effects on behaviour that operate largely, though not exdusively,

on the a:Jtomatic system. MINDSPACE - messenger, incentives, norms, defaults, salience, priming, affect. commitment and

ego j<;, helpful for gathering up many of the things that influence our behaviour. The MIN05PACE framework. or <IllY other

such 'gathering up' of contextual influences on beh.wiour, also raises some conceptual issues and prompts many rese£lrch

qUl.'stioos. of COtlfse.

Policies thdt change the context - the 'chQice architecture' - .and th~IS 'nudge' people in particular directions have cap­

tUr<'d the imdgination of academics and policymakers at the same time as the limitations of traditional approi1ches have be­

come apparent Popu!.arised in Thaler and SunscEin's (2008) book Nudge. the theory underpinning many of the policy

sugge')tions arc built on decades of research in the behaviollral sciences. and partiClllarly behaviourdl economics. SOIlle of

the elements in our MI~OSPACE framework overlafJ with dnd even explain Thalet .md Sunstein":; [2008, Pp. S 1-100"; six prin­

ciples, or l1udges. of good c!lOice architecture: incentives, understalJd mapping. defaults. &>1ve feedback, expect errOf, and structure

complex choices,

Clearly, 'incentives' and 'defaults' are directly represented in M!f-iDSPACE. We suggest that tile other effects from Nudge

can be interpreted as part of 'salience' because they all aim to trdnslate choic('-related information into a form.at that is man­

Jgeahle by a cogmt!VE' sysrelu with a limited capacity for information pmcessing and H'pre ..entation" To 'l1nderst.and map­

ping' requires translation in terms of.1 smg!e most salient (prominent, useful. important. memorable, etc} dimension, and

.serves the processing principles of judgment heuristics that operate with one attribute at a time (see Gigerenzer, Hoffrage, &

Goldstein, 2008). Simil.1rly, 'givH\g feedb<lck' requires thar the feec.back is t;alient.

'Expect error:-,' involves errors such as forgetting to tJke one's pills and Cdn be solved by making the task and its key attributes

more s~l!ient without changing the task per se, SL:ch errors can also be dvoided using other techniques such as 'defaults· (taki ng

placebo pills for the ddYs without d pill) or 'priming' (taking [he pill after some regular daily activity). Finally, 'structtlring

complex choices' simiLuly involves redesigning the choice environment when people make choi('€'s between multi-attribute

altern<ltives. This is done to make- chOICe env(ronments mandgeJble by ITIentdl heuristics, such as ordering alternative:; (e.g..

colours) hy similaflty (see Mt:::.sweileL 2003),

274

There of course many unresolved issues in applying nudge~hke. Mindspace-type interventions, In particular. how long do

the various effects last? On the face of it, the effects of. say. pliming appear fleeting, .md last for only a shon while after expo­

sure to the prime. This does not mean. however, that their impact is fJet.~tjng, since the behaviour and decision may have been

changed in that interval: the priming effect may have led to someone making d commitment that translate;; in::o longer-last­

ing change. Thus, effects such as priming may be thought of as ·~riggers'. Others may be seen as 'self-sustaining' effects: once

eTh1cted, their mode of operation support') continuity, for example. the use of defaults is based on the statL:s quo bIas. which

encourages stJbill::y dnd minimum effort over time,

There i<; also relatively little practical evidence abol!t how the effects might hahituate over time, Success will probably

depend on whether rhe individual is broadly happy with the result - in o~hcr words, the reinforcement thai: follows it.

The best interventions will certainly he those that seek to change minds alongside changing contexts, Smokers trying to quit

deliberately try to avoid some of the primes that encourage their smoking, such as the hJbit of having a cigarette with a

drink MINDSPACE effects that direct them away from smoking are likely to be welcomed ratber theif! consciously resisted.

The effect may then reinforced by the sense of feeling good.

Another importiHH question, especially a<; it relates to policy, is whether the etTecb of MINDSPACE differ across the pop­

ulation, and what impact this has on inequalitie5. Tf aditiona! interventions thdt aim to 'change minds' through ed~lcation

and information generally work best on the better educated and lnformed to begin wirh. As ,) resl!IL information about

!low to access smoking cessarion programmes, for exampie. has had the greatest effect on more affluent smokers, .md thus

\\ridened the g~)P between the most and least healthy (even if tbe ahsolu~e levels of health bave risen in both groups) (Schaap

et aI., 2008). In contrJst, interventions that 'change contexts' may affect us ail in broadly similar ways and may therefore not

widen any existing inequalities. They may even narrow some of the gdpS: chdnging the pensions default w auromatic enrol­

ment brought a particularly large incrC'ase in take-up amongst low and medium income workers. eliminating most of the

previous differences jn participation due to income, sex, job tenure and race p,:1adrian, 2001). Owrall, though, the evidence

on the distnbu:ronal consequences of MINDSPACE is stlll sparse.

Future r{'search challenges ,]/<;0 involve conceptually jOining up the effects, both within MiNDSPACE and across the dual

processing mode) of the brain, so ;:hat we have a clear understanding of the underlying mechanism~ d,ivlng these va.nOllS

effect'), Neuroscience now offers profound insights into how the human brain implements high l<-vel psychological functions.

including decision making. Such knowledge has been combined with insigh~s from orher cHsC!Dlincs [0 spawn new disci­

plines, a peltinent example being the field of neuroe(onomics (Glirncher. Camerer, Fehr, & PoldrJck, 2009). This new field

hJ~ already generated remarkdble findings into questions as c,iverse as how people learn III an optimal fashion, how Ill:man

preferences ale formed and the mechanisms that explain common deviations from rdtionaW:y in OJr choice behaviot:r, The

wider impacf of these findings is that they suggest d profound revision in how we construe the architecture of the human

mind.

A'l with all of the effects ,:wd the relationships between them, we need more research to c;;;tab!ish how robust they are in

real world settings. Lab expenments have taught us a tot but tbe most important: lessons .1bout what influences our behav­

iour - and when and how - wlll come from field experiments rha: take the control of.-he lab out lnto the real world (Harrison

& U;;;r. 2004). Thus, the next steps for behavioural economics dre large field studles in areas (hat will generate policy relevant

information (see DeliaVigna, 2009, for the gathering of field studies in the area).

We recogohe that there iIre inevitahle compromises in reducing a body of effecrs into a smaller grouping of over-arching

categories or effects. As al:thors we spent considerable time shtfting the literature, filtering out effects that lacked clear rep~

hcatJon and grouping together those that made appear robust into a limited number or categories, A key test of :he frame­

work among the academic communi~y will be whether there are major effects lhdt are not adequaTely captured within it,

Another, more subtie critiqL:e could be thdt the \11NDSPACE framework blurs the boundaries between extern.li levers (such

as defaults) and internal psychological mechanisms (such <15 .affect). To practitioners, this distinction may not be thdt impor­

tam sinn' their roell,'" is primarily on possible policy levers.

We have focussed on 'going with the grain' of human behaviour in ways that will bring about change:. ill behdviour th.H

individuals may appreciare. It is beyond the scope of the present paper to discuss what 'appreciate' will really look like, but

this shoule: result in measurable change;;; in utility, however this is defined. It i':i wortb noting that we are being nudged in

variOLI":i directions all of the time and we should, in the very iea,t, be alert to the source of !:ho~e nudges. We hope that

7v1INDSPACE will make U':i a O:-tle more alert to such effect'), so that we can begm considering furthet their appropnateness

in differen: individual, organisationdl and policy settmgs.

Acknowledgement.s

We would like to thank the CabinN Office (UK) for financial support in developing key palts of rhis pa;Jer. We <lrt' very

grateful to Daniel Read ror comments on an earlier draft of this paper, to two anonymous ft"'ferees, and also roJill Rutter. fhe

usual disddimer applies.

References

ADMli\", A., & (;2.y, 5, :'2004:" 111(' lffip,1(t of prl')ur:ed c·on5<:nt l('gJ~L:u:on 01: CJddverlC O'gdr.

593-G2C

Ck:;c<llwn: A ('~U55 GJ;:ntry "udy.j<i].';rwi IJ/l!('altll Ecufl(Jm1cl, 25

:n5

Ak(,rluL G. A :2002) !:Ic,:aYj(l~iI! 'ndCTOet onGmic~ a;-;c maCrrJl'lonom:, behavIOr. Amcncon EconvrnJc g(,v;1'w, 92, 411-4:n

Alko!:. H, \2009) Soc,!] no:ms ar.d er.('rgy cor;se:vatlon D;'ictlSqOn ritper. Cenrer for Ellerxy and !::nvir6nm"n~at PO!I,y Resear('1

A!!CO~L H. ~?Ol I}. Socli11 n,):"r,', .1:lti tHe!gy constfll<1[Jon.}o]1l1lai oj PUbliC EC:lrlOmlC~, 9';, 1082-109'5

Atw!y, J. (20G8; r~cd,nJb!y Irf,uionaL The hidden f()fc('\ th,ll shJPc our dfcl5lons. Harp('r-Co;il:-ts

Ar,cJy. 0. i.ocw('rls(em. G.. & ;;fe:e{;, D, (2D03), Cohcreru arbi;r;l!infs~. S~ai)!e d"r;:,lfld (Urvc;; Wl(':O\!; ~,aD:e p 'eicrenceo Quorra(r jOWild! oj E(OnOlllltS. 11K

7'1- !O5

A;ldy. OH & Wcrtenbroch, K. (.'002). Pronastma(ICn, Geadhnes, and perfOrm,1f:ce: ':le:f<omru; by p;;:(CmlnllmenL P3 y cinlogn-:;/ Snencr, 13. 21")-224,

A,hraf. N, Karlar, D & YIIl, W. (2006). ;ymg Odysseus ro the rna,;:: Evidence ircm.1 (On1r.I~mCnt S,WJJtg<; pnxllKl 1:1 ,!1\: Philippine" Q;Jorledy journal oj

E;,;ollort:ws. 121.635-67;

Axeirod" R. ~ 1936), An eVO;l1tionai~j apfllO,lC:-' to non" Amerlcar Po/iU(1) 5,:;(;;1(\' RvYlf'W, .;0. W95-1111

Handler,l. 0 .. h.<.'an. E. & lmnn. R. {2006; The CVO;U~i(1;l of (ooper,Hlve no:ms: :';Vlcer,«(' j'wm.'. ndwnl field expenment" AdvancE'.' "1 fennolll::: Anulym [7'

Poir:-y 6 {Arude 4:.

BMsh, J (2t:lOG; W~1i1, haw wr: he~'n pem!ng i:\lf ~hes(' YNh") Or, tl:e dev('!opmefH. rnr;:f:,mhl';~, 2nd emlngy nf noncollscioU'i ~ocli:1 hchaVIO( Eumpnil1

}0urna! oI S(}L,ol PsycholuS}. 31;, 147-168.

{{argh" J ' & Chal'trand, T" ( 19'19\ TLt' unt-earabj(, Juto:n,lt\City of bt'!ns. Ank'mal1 ."sy:lwliJ!{I5{, 54, ,,62-479.

B"ltt-son, \1., NerOe.IL & Rober~s,:::;, (L006:', Cue, of:lemg wrltt;wd enhd;tn: coope:rttmn In a real-world ~e:t.ng 8:oiogy Le~rrp,. 2. 4/L-41"L

BC;ltty, T.. ~ll()v,.:..... Cn.w,!ey, T. & CT1ed. ( (201 I! C.lSh r,y Arty ot::er :lAme? EVI(!,:once en labelLng L'f)nJ tne :;K wmter tUf'! payrnC'nt. Imlill,te for Fi~ul

Stud.es WOl'klng f'dper

BeckeL G,. /I, Mllli:gil:J. C. (19971. The cndogenm.:s cerermina~jon ot IClle preference. Q!la:teriy jou'TJal oj" Eco;101mf~. 112(3), 729- "ISS:.

BrlTl, 0 {I'167;. S\'lf·pt'fU:P::OI1' fVl dlternafW(' ;merprctdt.cn of c-ognillve d;sson,;nte rt:("10meEd J\ydwloglCul l?!:'VlI!w. 74. 181·200

Ber,:r:md. M .. Ka:-:,n. D. Muil<1ir:.ati~aJl, S.. ':!ha;1;, L & Zmman.J (2ClD}. \Vhat'" advert;,1Hg ::-onrerJwiJr'::h? Ev:df'f.ce Cern;; consu,'ner cred:t rnarket:ng: field

expennl('ilf. Qoo:1erly .I')wnoi:J EC(Hwrr;ic;. 125. 263- 305.

B:{X::ICJ'!, C i200G). riw grammar oj 'iQci£':y: 7'11£ na,we at;:; dynamic-l c! '>odall,nrrt<s. ~rw York. Call1Jtldge L!ntVeh:ty ?f('S<;

3urgc:, J ;! S99;. Thp fJc:-ID-the-door rcmpl!a~;:e pfl1CeCll~e: A ]l~lll~lple-proce~~ aoa!y'i:\ ;Hld revlCw. PCGonr;lny ad Sonai f',ydn:!ogy Pcv,,'>"-, J,103-]25,

3u~ger, ". & Lyn:--:an" 1. (2018). Bettmg on weight los, and 105iJlg' Per';):1.J1 ga,nbks as WJ1)Imtrcnl ))wd;.l!llsms App!u:d hO'lOmic; i-Cf{en. 17(12).

;IS!-~157

!1urK('. M..A.., & P:.ytoo-'{ouflg.!1 (lOll). Sonal norms, In A !lJSln.J Sfn:--:do,b. M j,'Kkmn (fe,,), Till' handbook oj 'i!l(lO! CCoJllOrIIK'. :?p. 111-318).

An'm('rd,!I;~ ~;mh-I-loi!a"d Press.

c,mmet Ofhee (201G) Cn'in;;;: C'f'Nf paper L·'}flCOn' 11:'\<1 GOWf!1me:u.

tabllltt Office ~2011 J, 4;;plyltl7, l,wlw.\<Iourolll1s1gilr to fwalfh. L:)ndOT tiM C:o\w~nn1ent,

Chaiken, S.. (I" TIOp,'. Y. {E(~~-". ,;i99g} DlIQ!,prOCfSS tb:>oucs;:1 salwl psychoiogy. New York: Gu';rord ?j'e\~.

l,lnoli, G.. Cho). J.. l.;jJ~on, D" ~1,)drr,Hl, B.. & M('r~l';k, A. ~20U91. Optlm,1t cd'auft; dnd aelve ctcc-Iswm QUQI ferly :oumc, oj FnplO'flld. 124. 16,{9-1674.

Ch.lliranc., T.. & Bargt;, ]. ( :999\ Tlw th.Jnwlcon efktL jOlJma, (1r PerSOft((llry ora So(lCi f'sycllol{l&'. 76{6:, 853-910

(ONlY, R., iJ)oney, A.. & ICof~, K (2()Og). Sa]j('nte and taxJ:tlcn~ Thenf,} ,:md ev!d<':tce Americal1 f-WIWlnK Rt'vn....." 99. ! 145-1 i77"

eh;)I,) lri)b~Ofl, D.. MadnJI1. B.. 8, \-1elnck, A. (2004). For bNh::';' or wr::n:c De(il~;1r cfktr; and 401(:(1 -"lVlngY. behaVIOr. In u,wi::! A Wise ~[d t Ferspcc:rl!les 011

[he <'(TlJ:OI,11t5 (1f flgI'lg (pp, 81-121). ChlCJ.gO and Lcndo:t: U'llVC'fs:ry ;)f Chicago Pre;!'.

(lAld,HI, R (2003! (r,1 F':mg ,It,wn.HiV!.' me,~age, to p:"{}tef't the C1WJfonmeflt. (Wl'c'nr Dlf("c/I(ll;, Ifl P::.ydwloglcQi Sn(:'r.c2, U. 105-IJ9

(!d1Cm•. R. (2007). infl,wllee, Ihe p::rythn!ogy 0/ pero,UOS1S:1 ~reviwJ ect,: Nevv Yor,,; lI'lrperBlI~:ne~,.

(laJdml, R, I<ai!gren. C, & Reno. R, : 1991;. A fenls tf;rory or nOfnHllve ondtlct. Adw!i!cCS In fxpf'nJwmaf Socw! [-";YCllOic)gy, .N. 2:Jl -234

(L1~;?,J, & McDonne!L A :2000;, The reiJt:onship of pCfC(:ptwns of dicollol plomo;l;::w. dnd peer d:-:nkng nmm" to .l!m:n! pfobr:m$ reporrC't: by coUege

s(qd('nt~ jO;II;wi oj'Co1!:gr Swdent Oevelr:.pment 4/,19-26.

lr,)wford, V , & M('~'!g.l (20 III New York C!\y cabc(;vers' la':lor supply r~v~sJ1120' Retefrncr-dt'pe:10ent prc!efrnC('S with l;;tloDdl-rxph;.rallOJH {,Hgrt'i Jo;

hour~ and :nC0IT\e Ap1t?llCQll E'cmWrIIK !kview, lGL /912,·1931.

(10t:qvb~. H" I\; Tilaic-r, R. H. (/OQ<;). Design chc.we\ 1'1 Pdvdtlzef' ,O(!Ji''i(,CJ[~[y ~y5t('nh' U'-Jlniflg [ron't l~l(' SW('dlSh l'Xf)(',ienc-e A'l1(;r:cerl FCO!1:::rJ'lh R<'vww.

94.4,:.:i ..428

(U;L'i. V ,G,ubr,11l-Al(/:;O, N ,& '::.co<r. B, (2007], M,,~t;:l\ of milfkcting: B,inging pnvJte Sfc'lOl sk:!h ';0 puiuc heJ:!tl1I,Mrtne'SJlp~. A'ilCriC(JfJ jf)l1rna! c{J'llbiv

HcuirlL 97. (i34-64I,

De \-lal'IJDO, B., Kdmar,ln.:J ,::,eyrf,ouL it. & DoltH1., R (2006;. Fr;l:Tw~, \)las(''i, and f,1:ion,,( tle«w:!fl-m,'kll~g 111 the hun~Ji1 or,J;n. ,)clt>nn\ 3D. 684-1.,87.

JeliaVq:pJ.. <;, (2{J09), Ps.ychology ,j,ntl ('wcomio. r.vidcn(~ from rht fie;c_ )ollmci oj EconO;'llC L'fc'rawrv, 47 11'j~ ;172.

uJjK"te,hL:13. :\.. :;. Sargh. i- A (2CUI), The peTe;:J(]Il'1-I)('h,WlOf i;'xprrs~w.-;y; I',;.:ro;n,lfi<: ('f:cct\ of ~()na; pt:fC:pllO:-: en socui bt:haviaL Advuncf'~ III

rxpt'rrrwllIo/ So·-wllJ\;,ct.ulogy, 33, 1-40.

f)i;k5~el'jLHS, A__ Bu'<.'-1 W., Nordgren. L, & 'Ian Haaren. R, (?DOG). 0;-; makmg: the fight dlOlce ThC' Cle;I!JNatiO;]-w;th(\u~,ar:c'lr!cn eHcr!' ')ne:w!, 31 L

l00'5·j{)(l7.

Dooh, ,4,,, & GrO~j, A. ': 1'168). SL'ilfth ()~ fn.slr,Hor ]\ ,111 l!1hl()JlOf of 11Om-ho;:k:ng r('~p(\me" jrurnal o/,,)cai J'Syd'Diogy. 7b, 213-218.

Dr,:t,·veE,. ~,'... \lNCJ;fc, R., 8, I'ow::it:-;avtc. ~. PC to) P:'immg COopl'f~.uon ir: ;;')(\,1! dl;emn:a g<lme" 1LA f)bcmsio;] I'ap"r ~o 4963

Dur.o, r:" ~ S2.('I, c, ;2U03} Tt-.r wlr of InfofH'.MIOO afU! 50(1;1 H:te(dCLIO"" in (l'tlfe:nelt plaft r'eUS!;)f1~' [vldt·nce [,Qm ,1 ra:;domifcd cxper.mc;-;t. QlHlrlt'riy

jO~!f"al OJ Emllnmin. 1 i8. H15-SQ

Dup<l~, p, (2Ot~9) Do 1l.'(':lilrWf$ ;e~pcnd [0 HlV fisk in:onnatkn'i FVld(>r:ce fmn a fi,dd eXpCln1enr In J(enYJ. National Burrau or ECC:W!l1K Rr"cafcr War-KWg

;'d;X'f Nn~ 1-!707

Ebler,j. fEd.) (:9%J- RfUlOlloi ZilOIZe'. Oxrord: !:las); BIJ:rkwelt.

DUl;1:1l1 ji, Y, , Alodfrann, ::>. f..·1Itcheli. P." EML A. & GII;et:c, 1. (200G). COI1(eJ)rualrzmg me mfluc1(' o~' soCIa! agents o{ hejJ,1vl(;: ('~lan.5e: A me[a a'<!ly';l~ of

the efkcnve:;e<,s 0;' dlV 'pft"Wnt;nn Int;:-rvcn(ionls:~ for dH(e),f-flf gr'Jups. !,;;:yrfw:c!Jlcai Bulk-wI, !J2, 2. 12-248

Evan5. J SI, 3. T. ': ':0(3). D'-hll~:)roc('~S!!:g ar-coo il~$ 0; )(:,1$Oilll1l" judgment, ;:;:rJ "O( :,11 (ognl[10.1, A:l'lIlol '\;"\111'1." of PI Fchu!ogy. S:;. 255 ~ 278

feln. L & Crwt({'. L (Jo\17). Do wcrkc" work ;nor;:, If w;,g,,-~ arc hrgh7 t:v,denre from a randOf11INd field o:pcnmc:l!. A.mi'l1('an FC()flO!JHC R::I!/f'W, <)7.

29FHI7.

rCIl\Il('lg, R.'; 19SG} Credn "lrd-, ;IS spend!::g 'ilClil\,Flr.g: ~:in'tm Journal cI t"wL>l,rr:er Rncan:!!. 13.3-48-1'56.

re.;ungef, L I: 957). A thl'fJry a( mgnitH'o: dlssonancf', SI,mford, CA: S(,m(ord lImwhJly rr('~5.

Frey, g" is Sf{'ph{'n .'-1eler, S, '2004). Svua! COllljXIfhO(1\ ,tIld pIC ,~on,ll hellavlc~; 1 t'''t!ng 'Cond;r.o:-vl COOpCfJJJ)fl' If: J tte!s ('xper:rnrr.L ilfll(,;'llan EC(;;,OIllH'

I?CPf'\V 94. 17 17·1::22

GerbeL A.. 8l Regel'S, T ,200t;:, ';tSU'IPUV(;' soua; ncrms an::, mdj\'anon ro VOlC: Evnybf)dy's v()(jng ,lflU sn ,h()~.Id yo",.j,wrr;o: orp;;in1d. 71. ,- 14