CHAPTER 4

TONALITY

4.0 Introduction: recapitulation

The phonological units of English Intonation can be represented on a hierarchical rank

scale in descending order as: Tone group

--->

foot

--->

syllable and phoneme. The tone

group is the highest ranked unit and it consists of one or more feet. A foot in tum

consists of one or more syllables and so on. Thus each tone group consists of one or of

more than one complete foot and so on throughout.

The foot has been described as the unit of rhythm in English which has a structure of

two elements. 'ictus' and 'remiss'. in that sequence. Each ictus begins a new foot.

The unit below the foot is the syllable, displaying the two primary classes 'salient' and

'weak': the salient syllable operates at 'ictus' and the weak syllable at 'remiss'. The

salient syllable or ictus is the obligatory unit while the remiss is the optional unit in a

foot. Every foot therefore contains the element 'ictus' which may however be silent

(have zero exponent) if the foot follows a pause or has initial position in the tonegroup. A foot with non-silent ictus is referred to as a 'complete foot'. Not every foot

contains the element 'remiss'. Thus each foot consists of one salient syllable, either

alone or followed by one or more weak syllables; in addition a foot that is tone-group

initial may consist of weak syllable(s) only (with a silent ictus).

The foot is characterized by phonological isochronicity: there is a tendency for salient

syllables to occur at roughly regular intervals of time whatever the number of weak

syllables in between.

4.1 The Tone Group (or Tone Unit)

It is thus the foot which operates in the structure of the tone group. Like the foot. the

tone group also comprises two elements of structure: these are "tonic" and "pretonic".

The element "tonic" is obligatory: it is present in every tone group; the element

'pretonic' is optional. it mayor may not be present. If the pretonic is present it always

precedes the tonic. A tone group contains a pretonic if. and only if. there is at least one

60

foot with ictus not zero (i.e. at least one salient syllable) before the beginning of the

tonic.

In other words. each simple tone group consists of a tonic or tonic segment. which

extends from the tonic syllable right up to the end of the tone group and this mayor

may not be preceded by a pretonic or pretonic segment. For example in II everybody I seems to have I gone away on I holiday II

The tonic begins on the first syllable and extends over the whole tone group; there is

no pretonic. On the other hand in II Jane may be I going on I holiday at the I end of the month II

The first two feet form a pretonic segment and the remainder forms the tonic segment.

The compound tone group has a double tonic that is. two tonic segments. one

following immediately after the other.

For example,

II Robert can I have it if I you don't I want it II

where the first tonic begins at Robert and the second at you. Compound tone groups

may have only one pretonic segment and it precedes both tonics. For example IIArthur and I Jane may be I late with I all this I rain we're having II

which has pretonic, Arthur and Jane may be, first tonic segment, late with all this and

second tonic segment, rain we're having. No pretonic segment can come in between

two tonic segments of a compound tone group. If they were merely sequences of two

(simple) tone groups. each would be able to have its own pretonic segment. Each

segment whether tonic or pretonic must consists of at least one complete foot. There

may be only one foot in any segment but there must be at least one foot with a salient

syllable in it.

For ego II

A

it's I Arthur II

61

There is no pretonic segment here even through the tonic begins at Arthur; there is no

salient syllable before the tonic. The syllable it's in this case could be regarded as a

foot with a silent beat (which stands for the 'ictus').

The structure of a Tone Unit:

Tone Unit

Structure ) [

+pretonic ~

IpretOniC

A

Tonic

I

-pretonic

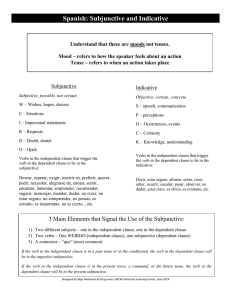

Halliday therefore points out, "in any utterance in English three distinct meaningful

choices or sets of choices, are made which can be, and usually are, subsumed under the

single heading of "intonation". These are: first, the distribution into tone groups - the

number and location of the tone group boundaries; second, the placing of the tonic

syllable (in "double tonic" tone groups, the two tonic syllables) - the location, in each

tone group. of 'the pretonic and tonic sections; third, the choice of primary and

secondary tone. I propose to call these three systems "tonality", "tonicity" and "tone".

The three selections are independent of one another." (1967: 18)

4.2 Internal Structure of a Tone Unit

David Crystal (1969) talks of the internal structure of the tone unit in terms of pre-

head, head. nucleus and tail. The pre head or pre-onset refers to any utterance which

precedes the onset syllable within the same tone-unit. It consists of an unspecified

number of unstressed syllables (at least one) but occasionally, under certain conditions,

syllables with some slight degree of stress (not equivalent to the stress of the onset

syllable and never with pitch prominence) may occur there.

The head of the unit refers to the stretch of utterance extending from the first stressed

and usually pitch-prominent syllable (or onset) up to but not including. the nuclear

tone. It consists of at least one stressed syllable and an unspecified number of

unstressed syllables. The nucleus is the obligatory element in the tone unit which

carries a glide of a particular kind. Halliday uses the term 'tonic' syllable instead. The

tailor nuclear tail may consist of an unspecified number of stressed or unstressed

62

syllables following the nuclear syllable usually continuing the pitch movement

unbrokenly until the end of the tone-unit. We may now make a characterization of a

tone-unit's maximal internal structure as being:

(Prehead) (Head) Nucleus (Tail)

the only obligatory element being the item in bold. The majority of tone-units tend

towards this maximal type.

Gimson (1962) uses the term intonational phrase to refer to a word group, which is

called a tone group by Halliday. According to Gimson, the boundaries between these

intonational phrases generally correspond with clause and major phrase boundaries and

are indicated by a combination of internal and external factors. The external factor

being a pause which can occur at the point where the boundaries are indicated by a[ IJ.

Often as an alternative to pause. speakers may lengthen the final syllable before the

boundary or increase the speed of the unaccented syllables following the boundary.

The external cues to boundaries are supported by internal factors like the completion of

a pitch pattern associated with a nuclear tone and a rapid change of pitch height of

unaccented syllables.

Therefore different linguists have used different terms to refer to the chunks of our

speech. Spoken English is not a continuous stretch of utterance but is made up of a

succession of tone groups. Each tone group is a unit of information according to

Halliday. The speaker decides how he wants to break up the message -unconsciously,

of course-into blocks or units of information and each of these is expressed as one tone

group. Tone group or tonality deals with the chunking of a message into larger or

smaller unit of information. In the Lexicogramatical stratum an information unit l is a

stretch of language structured in terms of given and new. In the phonological stratum,

the tone unit is more or less the same stretch of language structured in terms of

(Pretonic)

A

Tonic. Therefore the system of tonality deals with how a long stretch of

Lexicogrammar is 'chunked' by intonation.

I

In Halliday"s description "infonnation unit" <lnd 'tone group' are synonymou:-. terms.

63

According to Paul Tench, " ... tonality is the system by which a stretch of spoken text is

segmented into a series of discrete units of intonation which correspond to the

speaker's perception of pieces (or 'chunks') of information ... " (1996:8).

We chunk our utterances to give bits of information depending on grammar, meaning,

context, communication and the textual function of tonality.

4.3 Criteria for Marking Tone Group Boundary

Crystal (1969) identifies both phonetics cues and the internal structure of the tone unit

as criteria for boundary location. He says, " .. .internal information. along with the

phonetic information about boundary characteristics which is essential, is sufficient to

resolve any doubts over tone-unit identification in English" (1969:208).

He says that each tone-unit will have one peak of prominence in the form of a nuclear

pitch movement, then after this nuclear tone there will be tone-unit boundary which is

indicated by two phonetic factors. There will firstly be a perceivable pitch-change,

either stepping up or stepping down, depending on the direction of nuclear tone

movement- if falling than step-up; if rising, then step-down; if level. either depending

on its relative height, either a stepping up or down would signal the start of a new

intonation unit. This is due to the fact that the onset of each tone-unit in a speaker's

utterance is at more or less the same pitch-level. The second criterion is the presence

of junctural features at the end of every tone-unit. This usually takes the form of a

very slight pause but there are frequently accompanying segmental phonetic

modifications (variations in length, aspiration. etc) which reinforce this. Syllables at

the end of a unit tend to be relatively slower, but syllables at the beginning of a unit

have a tendency to speed up. Very often all three features; a change of pitch. a pause

and a change of pace or anyone feature may be present. The marking of the tone

group boundary has been most controversial in Halliday's description of tonality. He

says ... m any case it must be insisted that the location of the tone group

boundary is a theoretical decision: the best description is obtained if a

new tone group is considered to begin at the foot boundary immediately

64

preceding the first salient syllable of its tonic or pretonic, as the case

may be. But what matters is that the boundary between any two tone

groups can be shown to lie within certain limits, so that it is clear how

many tone groups there are in any stretch of utterance ...

Halliday (1967: 19 foot note)

The best decision would therefore be to mark a tone group at a foot boundary.

Cruttenden (1986) says that an intonation-group boundary should be based on 'external criteria'. i.e. on phonetic cues present at the actual

boundary. But in practice such phonetic cues (e.g. pause) may be either

ambiguous or not present at aIL Therefore 'internal criteria' must also

playa part: ...

he says that The assignment of intonation-group boundaries is therefore something

of a circular business; we establish some intonation-groups in cases

where all the external criteria conspire to make the assignment of a

boundary relatively certain ...

Cruttenden (1986: 36)

He also says And in some difficult cases. we take grammatical or semantic criteria

into account, i.e. when regular correspondences between intonation and

grammar/semantics have been established in cases where boundary

assignment is clear. ..

Cruttenden (1986: 36)

Cruttenden mentions 'pause' which is the usual criterion m the demarcation of

intonation-groups. The forms of pause fall into two categories. the unfilled pause (i.e.

silence) and the filled pause. In R.P. and in many other dialects of English. the filled

pause involves the use of a central vowel l;l J and a bilabial nasal I m J. either singly or

65

in combination and of varying lengths. The use of pause in general and the relationship

between unfilled and filled pauses in particular is subject to a large amount of

idiosyncratic variation.

He also mentions the fact that breaths are often taken at pauses and taking of breath is

the reason for pausing. He talks of three places where pauses occur in utterances. They

are:

(i)

at major constituent boundaries (principally between clauses and

between subject and predicate). There is a correlation between the type

of constituent boundary and the length of pause. i.e. the more major the

boundary, the longer the pause. Moreover, pauses tend to be longer

where constituent boundaries (usually, in this case sentence boundaries)

involve a new topic.

(ii)

Before words of high lexical content or. putting it

In

terms of

information theory, at points of low transitional probability. So words

preceded by a pause are often difficult to guess in advance. This sort of

pause typically occurs before a minor constituent boundary, generally

within a noun-phrase, verb-phrase. or adverbial-phrase, e.g. between a

determiner and following head noun;

(iii)

after the first word in an intonation-group. This is a typical position for

other 'errors of performance', e.g. corrections of false starts and

repetitions. (1986: 37)

Pause type (i) is generally to be taken as indicating an intonation-group boundary. e.g.

{boundaries are indicated by [/]}. Although this type of pause will be unfilled but

sometimes it may be filled and in such cases the filling seems to be used as a tumkeeping device, particularly in conversation. It is used to prevent another potential

speaker interrupting the current speaker.

Pause types (ii) and (iii) are generally to be taken as examples of hesitation

phenomena. Type (ii) indicates a word-finding difficulty. e.g. (hesitation pause

indicated by .... ).

66

e.g. The Minister talked at length about the ... redeployment of LABOUR.

The hesitation pause of type (ii) will occur before a word of low transitional

probability although it is unlikely before a word carrying the nucleus of the intonationgroup in which it occurs.

Pause type (iii) occurring after the first word of an intonation group. seems to serve a

planning function i.e. it is essentially a holding operation while the speaker plans the

remainder of the sentence, i.e.

e.g. Why don't you join an evening class? You'd ... be quite likely to meet

some interesting people

Pause types (ii) and (iii) are internal to an intonation group, and are not taken as

markers of intonation-group boundaries, because they do not result in utterance chunks

each of which has a pitch pattern within an intonation-group.

Cruttenden also says that a better system for measuring pause may be to relate it to the

length of syllables or rhythm groups in surrounding speech.

Whichever way of

measuring is used, boundary pauses tend to be longer than hesitation pauses. It is

therefore apparent that the criterion of pause as a marker of intonation-group

boundaries cannot be used on its own. Pause can only be used as a criterion if it is

considered together with other external and internal criteria. (1986: 38-39)

Apart from pause, Cruttenden talks about three other external criteria which may act as

markers of intonation-group boundaries. They are firstly, the presence of an anacrusis

which generally indicates the beginning of an intonation-group, e.g.

I saw John yesterday I and he was just off to London.

In this sentence. the most likely place for the first stress in the second intonation-group

is on

JUST:

and the unstressed syllables before "just' are pronounced very quickly than

other unstressed s yl\ables in the sentence. The sudden increase of speed beginning at

67

'and' indicates that these syllables are anacrustic and hence that it is the beginning of a

new intonation-group.

Secondly, and regardless of whether it is stressed or unstressed, the final syllable in an

intonation-group will often be lengthened, e.g.

On my way to the station / I met a man.

The second syllable station may be lengthened and this helps to indicate an intonationgroup boundary. The lengthening may be a by-product of two other things occurring at

an intonation-group boundary: it may be a sort of pause-substitute, as a sort of filled

pause. The final syllable of an intonation-group will often carry a final pitch

movement. The clearest function for final syllable lengthening is therefore as a

boundary marker, sometimes replacing pause and sometimes in addition to pause.

But he then says that the three criteria for intonation-group boundaries (pause,

anacrusis and final syllable lengthening) all are ambiguous between boundary marking

and hesitation phenomena.

The last external criterion concerns the pitch of unaccented syllables. Changes of pitch

level and pitch direction most frequently occur on accented syllables. A change in

pitch level among unaccented syllables is generally an indicator of an intonation-group

boundary.

(i)

After falling tones followed by low unaccented syllables, there will be a

slight step-up to the pitch level of the unaccented syllables at the

beginning of a new intonation-group. The change of pitch reflects the

fact that low unaccented syllables at the beginning of an intonationgroup are generally at a higher level than low unaccented syllables at

the end of an intonation group.

(ii)

Following rising tones there will be a step-down to the pitch level of

any unaccented syllables at the beginning of the following intonationgroup. So a change in the pitch of unaccented syllables is a fairly clear

boundary marker. (1986: 40-41 )

68

Cruttenden lays more importance on the presence or absence of a likely internal

structure for an intonation-group as he considers that the external criteria which he

mentions are ambiguous between boundary and hesitation marking. He talks about

two internal criteria which characterize an intonation-group (i)

that an intonation-group must contain at least one stressed syllable.

(ii)

there must be a pitch movement to or from at least one accented

syllable.

He finally summarizes that one or both of the following criteria will in most cases help

to mark intonation-group boundaries. They are (i)

change of pitch level or pitch direction of unaccented syllables

(ii)

pause. and / or anacrusis, and / or final syllable lengthening, plus the

presence of a pitch accent in each part - utterance thus created. (1986: 42)

Cruttenden also talks about three types of pitch sequence which present problems for

dividing utterances into intonation-groups in English.

He gives the example of a

sentence:

J.

He

went

away

unfortunately

•

•

.~

•

••• •

We have a falling tone starting on- way and a rising tone starting on- fort with an

anacrusis on- un- intervening between them. The problem here is. are we to

analyse this pattern as consisting of one or two intonation-groups. In terms of the

external criteria discussed above if there is a pause, or anacrusis on- un or

syllable lengthening of- way. it must be treated as two intonation-groups as there

is a pitch accent in each half. It must also be taken as two groups if the syllable

un- is on a slightly higher pitch than the end point of the tone on- way. But

frequently none of these patterns will be present and thus by phonetic criteria

alone we would have to consider the pattern as one group.

69

However, he suggests that in such cases, we can take syntactic or semantic factors into

account. He says In this type of pattern it seems reasonable to take account of the fact that

markers of a boundary frequently are present between final 'sentence'

adverbials and what precedes them and to regard the 'basic' intonation

as involving two groups.

present, can

The pattern above, where no markers are

accordingly be considered a special

instance of

INTONATIONAL SANDHI. (1986: 43)

Sandhi ('sandhi' was used by the ancient Indian Grammarians) means joining together

and indicates the merging of two basically independent intonation-groups.

2.

The second problematic case concerns vocatives and reporting clauses

In

sentence final position. For example -

Get a moye on. you stupid fool

• •

•

•• •

•

This kind of utterance has been analysed as having a low level tone within a separate

intonation-group, since a pause is often present before the vocative or reporting clause.

But Cruttenden says that... such sequences consist of one group only, whether pause is present or

not, on the grounds that there is no pitch accent in the vocative or

reporting clause (1986: 44).

3.

The third problematic case concerns instances where an adverbial on a low

pitch may belong semantically either with the words in the preceding

intonation-group or with the words in the following intonation-group.

example -

70

For

......

He went to the States of course he didn't stay very long

•

•

•

•

•

•

~

(In this example, punctuation marks have been deliberately avoided)

Here the low pitched of course could belong either with what precedes or what

follows. In this example, either the three syllables of course he are just above the

lowest pitch and hence characteristic of beginning pitch rather than end pitch, in which

case there is a boundary before of. or else the two syllables of course might be at the

lowest pitch with he occupying a slight step-up, in which case the boundary would be

between course and he.

Cruttenden considers that the three problematic cases discussed above show that the

concept of intonation-group is like many other units of linguistic analysis, essentially a

theoretical construct. (1986: 44)

Brown, Currie and Kenworthy (1980) analysed spontaneous speech and although they

found Crystal very explicit, they expressed their difficulty in identifying the tone group

boundaries.

They faced two types of problems (i)

Absence of pause in stretches of speech which have more than one nucleus

(ii)

Presence of pause where "the overall pitch contour appears to be carried on

through this pause".

Therefore, they prefer to work with pause-defined (1980: 43) units rather than toneunits.

Their problems could be resolved (i)

In case of absence of pause by - the association of the foot boundary with the

tone group boundary and the identification of the tonic syllables and the tones

operating in them which will help in locating the boundaries in most cases.

(ii)

In case of presence of pause by - the recognition of the role of silent ictus in

the foot and the presence of silent feet in speech.

71

Pike (1945) says that phonological units do have 'fuzzy edges', for instance, how do

we identify, the boundaries of consonants and vowels, especially in the light of

instrumental evidence of continual overlap. Some linguists have maintained that it is

not absolutely necessary to identify tone boundaries precisely. There is often also a

smooth transition from one tone unit to another without a pause.

Halliday has

incorporated this aspect into his work by talking of compound tones: a fall followed by

a rise etc. When cases of dispute are difficult to resolve, we have to take the help of

grammatical or semantic criteria.

4.4 Identification of Tone Group Boundaries in AE

The system of tonality performs the textual metafunction of language by dividing the

message into smaller chunks which are called information units by Halliday. The

other two metafunctions of construing experience and enacting interpersonal relations

depend on being able to build up sequence of discourse, organize the discursive flow,

create cohesion and continuing of the discourse.

The criteria for identifying Tone Group boundaries m this study were based on

auditory as well as instrumental evidence. The study revealed the following eight cues

for marking tone group boundaries: (refer to Appendix IV)

1. Tonic prominence

6. Change in pitch direction

2. Pause

7. Pitch jump up or jump down at

the onset of a new TG

3. Lengthening of last syllable

8. Anacrusis

4. Foot boundary coinciding with

tone group boundary

5. Silent ictus beginning a tone

group

However, the frequently occurring cues found were· tonic prominence, pause, pitch

jump up or jump down and change in pitch direction.

1.

Tonic Prominence

Tonic Prominence is the identification of the tonic syllable in the tone group and it is

one of the important cues for the identification of the TG boundary. It carries the main

burden of the pitch movement in the tone group.The tonic syllable is heard longer and

louder than the other salient syllables in the tone group. it plays the principal part in the

72

tone group. It covers the widest pitch range. A tone group will have one tonic syllable

which generally occurs as the New focus of information placed at the end of the tone

group. For example:

120Hz·400Hz

1/2 from I then II have Istopped /SlKGing II

Speaker

HD20LA (tonic prominence)

Clause(s)

from then I have stopped singing.

TGs

//2 from I then I I have I stopped I SINGing II

2.

Pause

In this study three types of pauses were identified i.e.

I.

11.

111.

significant pause

insignificant pause

filled pause

The pause may be due to several factors such as hesitation, difficulty in finding

appropriate words, placing of grammatical words and structures such as adjuncts,

adverbials. noun phrases etc. and the tempo of the speaker, which is a variable

idiosyncratic feature.

i.

Significant Pause

The duration of the pause is a significant indicator of tone group boundary. The

following example (speaker: DB I UA) shows significant pause indicating TG

boundaries between TGs.

73

90Hz-300Hz

//2 the/oxygen of the/water / body /recei;VING//

Speaker

DBIUA (significant pause)

Clause(s)

thus. the oxygen of the water body receiving

TG

/II THUSI/2 the! oxygen of the! water! body! recei ! VING 1/

There is significant pause after thus and before the beginning of the next TG.

Significant pause was used with grammatical categories as well as between two regular

clauses marking them separate TGs, it could also be observed in free speech, may be

due to the difficulty of the speakers in finding proper words to continue their speech

thus often breaking a regular clause into TGs.

; ACtiyiti

)

Speaker

DD I 3MA (significant pause)

Clause(s)

and I like to perform some social activities.

TG

1/ I AND 1/ 2 i! LIKE 1/ 2 to! perform! SOME 1/ I social!

Activities 1/

In the example above significant pause divides a clause into several TGs.

74

ii.

Insignificant Pause

The duration of the pause is not significant, yet it clearly marks a tone group boundary

perceived auditorily as well as from other internal cues like tonic prominence etc.

lJ-- ..- - - - - . - - - - - - - - - - - ... - - - -..

50Hz-280Hz

! II SPLEl>didll

/ /1 wbat a/beautiful/SIGHT II

Speaker

CG3UA (insignificant pause)

Clause(s)

Splendid what a beautiful sight.

TG

II I SPLENdid II I what a I beautiful I SIGHT II

No significant pause can be observed after Splendid. But the presence of tonic

prominence and pitch direction are cues suggesting a definite TG boundary.

50Hz-350Hz

/ /1 like ! In I DIAl I

I/R-F in / DEVeloping,l COll'triesj /

Speaker

NDI5LA (insignificant pause)

Clause (s)

in developing countries like India

TG

II R+F in I DEVeloping I COUN tries II I like I In I DIA II

The pause between the TGs is insignificant but the change in the direction of the pitch

and the tonics in the TGs identify the TGs.

75

iii.

Filled Pause

A filled pause is filled with sounds like -aa ... ; 1..1.. etc. It may be just a variable

idiosyncratic feature of the speakers. Some of the speakers tend to use filled pauses

more frequently than others due to their inability to find proper structures to continue

and to find time to relate their thoughts to their speech. It is noticed that a filled pause

marks the beginning of a new TG boundary.

50Hz-300Hz

112 aa~./my /FAmily / I

II 3 aa~

~/consist

of/four / mom / BER/ /

Speaker: DNIOMA (filled pause)

Clause(s): my family consist of four member.

TG: //2 aa .. I my I FAmily //3 aa .. consist of I four I mem I BER //

In the example above, the speaker uses filled pause at the beginning of both the TGs.

thus clearly marking the tone groups.

e.. she's is aa.

50Hz-350Hz

1(2 e.. I SHE'S/ /

aa ..

;' /2 going to / fi /

Speaker: RDI9LA (filled pause)

Clause(s): and she's going to finish

76

~lSH/ /

TGs: /I 2 e .. / SHE'S /I aa .. /I 2 going to / fi / NISH /I

The filled pause in the above example occur between two TGs.

3.

Lengthening of the Last Syllable

The length of the final syllable of a tone group was found to be comparatively longer

than the other syllables of that tone group. This lengthening of the final syllable in a

tone group was an indication of a tone group boundary in some cases, for example:

and my wife is a good house \\ife

60Hz·200Hz

/ /) and,l Illy / wife I IS/I

/ /2 a / good / house /

Speaker: HN9MA (lengthening of last syllable)

Sentence: and my wife is a good house wife

TGs: /II and my / wife / IS II 2 a / good / house / WIFE /I

In the above example the last syllable 'is' of the lSI TG is lengthened marking the end

of the TG and the beginning of a new TG.

70Hz·200Hz

/ iL and/HIS; /

/ I I major/sub I jeet is / .-\SSamese / /

Speaker: CG3UA (lengthening of last syllable)

Clause(s): and his major subject is Assamese

TGs: /I Land / HIS /I I major / sub / jeet is / ASSamese II

77

In this example the last syllable 'his' of the first TG is lengthened marking the end of

the TG and the beginning of the following TG.

4.

Foot Boundary Coinciding with TG Boundary

According to Halliday the best decision for marking tone group boundary would be at

a foot boundary. This criterion has been observed in this study also as is evident from

the following example.

/_

2 take

/ LIST

/ __

-.L_ _/_

_ _/_this

__

_ _/_

Speaker

~

____

~

/ /_2gotothe

__

_ _ _ _/_GROcery/

_ _ _ _I_ _

~·

/01

JNCIIMA (Foot boundary coinciding with TG boundary and

tonic prominence)

Clause(s)

take this list, go to the grocery

TGs

112 take I this I LIST 1/2 go to the I GROcery 1/

In the above example, the TG boundaries coincide with foot boundaries.

5.

Silent Ictus Beginning a Tone Group

A foot may begin with a silent beat which has no phonetic realization like a musical

bar beginning with a rest. In English a tone group may begin with a silent ictus with

weak syllables optionally following it in a foot. A silent ictus is clearly perceived

before a significant pause beginning a foot in a tone group.

78

•.

I",,",,"

l

,\

J

"

i, "

Thus

//FRffiUS//

Speaker

NNRI4LA (silent ictus beginning a tone group)

Sentence

Thus the oxygen of the water body

TGs

II FR THUS II F+R

A

the I oxy I GEN of the I waterl bo I DY II

In the above example, the silent ictus marks the beginning of a new foot in a tone

group,

6.

Change in Pitch Direction Marking a Tone Group

Change in the pitch direction of the tonic, for example from a nsmg to a falling

direction indicates the beginning of a new tone group,

Speaker

PH4UA (change in pitch direction and silent ictus in foot

marking a new tone group)

Clause(s)

It's pleasant today. is not it?

TGs

II 2 A It's I PLEAsant II I to I DAY //2

A

is I not I IT //

In the example above, the first tonic has a rising tone while the second tonic has a

falling tone showing opposite pitch directions, Similarly the third tonic has a rising

movement indicating a new tone group, All the three TGs project contrasting pitch

directions,

79

7.

Pitch Jump Up or Jump Down

A pitch jump up or a pitch jump down indicates a tone group boundary. For a falling

tone there would be a slight or significant jump up to make the fall, and for a rising

tone there would be a jump down in the pitch to make the rise in the tonic. These are

important factors in identifying tone groups.

70Hz-250Hz

J;2 GEORGE;!

1/2 willi yOU! get the; C\R OUl/ /

Speaker

HN9MA (Pitch jump down at the onset of a new tone group)

Clause(s)

Will you get the car out, George.

TGs

112 willI you I get the I CAR out II 2 GEORGE II

In the above example there is a clear jump down in the pitch direction after the first

tonic to enable a rise in the second tonic in the new tone group.

H-~~~

..-~.l-. .

---1--- .----'--

.....--1---IL_ ....- - - ..

I come / wilh I YDC I I

~~+--t:.:.._.

/ / I if / you I LIKE / /

Speaker

MS 18LA (Pitch jump up at the onset of a new tone group)

Clause(s)

I will come with you if you like

TGs

II I I willI come I with I YOU II I if I you I LIKE /I

In the above example there is a clear pitch jump up to make a falling movement in the

tonic in the second TG.

80

8.

Anacrusis

A tone group may begin with a foot with unstressed syllables uttered quickly; these

unstressed syllables are anacrustic and is an indication of the beginning of a tone

group. These syllables uttered with sudden increase of speed usually begin with a

silent ictus.

' - _ _ _ _ _ _ _1'-'1_2_,_,w_e_d_o_h_,,_e.:./=.good_.:./_e~--,-p_~_a,--I_TI_O_"'..:/..:./_ _ _ _ _ _ _...L.l . .'"'<)

Speaker

CG3UA (anacrusis)

Clause(s)

we do have good cooperation.

TG

1/ 2

1\

we do have I good I coopera I TION 1/

In the above example the first three syllables 'we do have' of the tone group are uttered

quickly in 0.4 I 3s. with an average of 0.137s. which is much quicker than the speed

with which the other syllables are uttered.

This study has also revealed that the speakers made separate tone groups for listing

items; vocatives. inteIjections, responses, conjunctions, interpolations, adverbials, a

long subject, comment adjuncts and conditionals.

Speaker

NB2UA (listing items indicating TGs)

Clause(s)

would you like to have tea. coffee or juice,

TGs

1/ 2 would you I like to I have I TEA 1/ 2 Coffee 1/ 2 1\ or I JUICE 1/

In the above example. the listing items tea, coffee. juice are said as separate tone

groups.

81

Speaker

RS8MA (V ocati ve said as a separate tone group)

Clause(s)

Its no good Mary. TGs: II R+F Its I NO I GOOD II 2 MAry II

In the above example. the Vocative Mary is uttered in a separate tone group.

- ...-

/;1_

Oh_

;YES/I

_________

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _'--i ."

Speaker

JNCII MA (Interjection)

Clause(s)

Oh. Yes I have.

TG

II I Oh I YES/I have II

In the above example the Interjection marks a separate tone group.

o

Speaker

DBIUA (responses marking new TG)

Response

Yes

TG

II I YES II

In the above example the response 'Yes' marks a tone group.

82

-------------~-------__1

And

Speaker

DDI3MA (conjunction as a separate tone group)

Conjunction:

And

TG

II I ANDII

In the above example a Conjunction is said as a separate tone group.

801Iz-::501Iz

"T--·---------,r--c:--c=;-~H~.:.

_...._ _ _ _ _I_I_'_'/_TR_l1'_·K_·/_/ _ _ _~od._ _ _ _ _ _ _-''--_ _ _---1--f '~i

' A - - - - ..- - - --.---~-

Speaker

PBI2MA (Interpolation and preposition marking tone groups)

Clause(s)

I think. about

TGs

II I I I THINK II 2 a I BOUT II

In this example Interpolation and preposition mark separate tone groups.

"",<on

_~

/1 bas.i

CALly/"

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _/ _

_I _

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _-h:(1 ·31

Speaker

NB2UA (Adverbial as a separate tone group)

Word

Basically

TG

II J Basi I CALly II

An adverbial fonns a tone group in the above example.

83

Speaker

PB 12MA: (long subject as separate tone group)

Clause(s)

the head of the family is Prabhakar Bannan

TGs

1/1 the I head of the fa I MI Iy 1/2 is I Prabhakar I BARman 1/

In the example a long subject 'the head ofthe family' makes a tone group.

70Hz-400Hz

J /2 unfo[" I tu/NA TEly / I

Speaker

RD19LA (Adjunct as a separate tone group)

Word

unfortunately

TG

1/2 unfor I tu I NATEly 1/

The above example shows a comment adjunct fonning a tone group.

I I I if YOu ; LIKE / /

" /2 '"U COl1le/\,,-ith

Speaker

DBIUA (Conditional Clause in a separate Tone Group)

Clause(s)

1"11 come with you if you like.

TGs

1/21"11 I come I with I YOU /I I if you I LIKE 1/

In the above example a conditional clause is used in a separate TG.

84

For more examples of each criteria discussed above refer to Appendix IV

4.4.1 Summary

In Assamese English it has been found that the tone group boundary is identified by

several indicators of which tonic prominence, pause, change in pitch direction and a

pitch jump up or pitch jump down in pitch height being the important indicators.

4.5 Unmarked and Marked Tonality

Halliday says that if a person wants to give a piece of information it is conveyed as a

single unit of intonation, but it has to be worded and this is where grammar comes in.

The clause is the most obvious unit of grammar to handle a piece of information.

Halliday has tried to establish a relationship between a tone group and a grammatical

unit. He says It has sometimes been suggested that the division of an utterance

into tone groups is congruent with its division into grammatical units.

There is no agreement, however, as to which of the grammatical units is

co-extensive with one tone group; and this is not surprising, since in

fact the tone group bears no fixed relation to any of the grammatical

units of spoken English. There is a tendency for the tone group to

correspond in extent with the clause; we may take advantage of this

tendency by regarding the selection of one complete tone group for one

complete clause as the neutral term in the first of the three systems.

That is to say, a clause which consists of one and only one complete

tone group will be regarded as 'neutral in tonality.'

Halliday (1967: 18-19)

Tench (1996) has mentioned thatthe concept of neutral tonality is a very useful starting-point. It

embraces a very important point: the functional equivalence of

intonation unit. clause and unit of information. linking up phonology

with grammar and semantics.

Tench (1996: 33)

85

The tenn 'neutral tonalitl' is considered synonymous with 'unmarked tonality' by

both Halliday and Tench. Marked tonality is any case that does not correspond to

neutral tonality. It occurs either when two or more clauses fit into a single intonation

unit or when two or more intonation units are needed to cover a single clause.

Examples of unmarked tonality are I. II A dog is a man's best friend /I

2. /I He spoke to me honestly /I

Examples of marked tonality are I. /I He did. I saw it /I

2. /I We need milk /I some bread /I and butter /I

Halliday (1967, 1970 and 1994) identifies two options for a speaker(i)

he may select a clause to fonn one tone group - unmarked tonality.

(ii)

he may select more than one clause as one tone group or less than one clause

as one tone group - (these are two marked possibilities).

These two selections of unmarked and marked tonality can be represented also as

follows:

(one tone group = one clause)

Unmarked

Tonality

one tone group is less than a clause

Marked

[

one tone group is more than a clause

(Bhooshan 1998: 15)

Halliday says, marked tonality. where the tone group is more than a clause arises in

two types of sentences (actually sequences of elements of sentence structure linked by

presupposition): (i) reporting clause followed by reported clause and (ii) conditioned

clause followed by conditioning clause.

: \Ve have u\ed these two terms: neulml and unmarked Tonality jnten:hange<lbl~ in our study.

86

/I:!:" but I I don't see I why they should lose I marks for I this /I

/I :!: " it's I all right if you're I photo I

~nic

/I I what I happens if

you're I not /I

(ii)

If a conditioning clause precedes the conditioned clause which it presupposes,

the two may still sometimes share a single tone group; sentences of this

structure have neutral tonality, with a tendency for all clauses except the last to

select tone 4.

/I 4 " and and Isince the Icredit mark is a I hundred /I I +" you I

couldn't very weill mark out of a I hundred /I

In the sequence of conditioned - conditioning clause, there may be neutral tonality:

/I I " per I haps it's I easier when you're /I I marking I language /I

Relative clauses do not take a separate tone group in general while a non-defining

relative clause (additioning clause) take a separate tone group and is consistent with

neutral tonality. This is because relative clauses are rank shifted and do not operate in

sentence structure, whereas additioning clauses are not rank shifted and so do enter

into the sentence structure.

/I I " in I fact you I end I up with a I pure I culture of I something you I

didn't! start with /I

compared with /I I " I'm I marking a I thousand .. .11 4 " of which I three are from I

home centres and ... // (Examples taken from Halliday 1967: 20-21)

In the case of marked tonality. where the tone group is less than a clause, it occurs

mainly with the break (into two tone groups) coming after the first element of clause

structure. that is. the first element that contains a lexical item. The break occurs after

the theme. Halliday mentions other possibilities where a break occurs (i)

break after unmarked theme /I :!: all the I dialect forms are /I I + marked I wrong II

87

(ii)

break after marked theme 111 1\ but I in A I merica they they /I I !l!yer I things /I

(iii) break other than after theme /I

1

1\

they can I change I overnight I then /I I

1\

into I something

comlpletelyl different /I

(please refer to chapter 6 for the symbols used for the tones in these examples)

He also mentions that a break other than after the theme is most commonly found

immediately before a clause - final adjunct, as in the above example.

To sum up, neutral tonality refers to the selection of one clause to from one tone group

and this clause may contain within it embedded clauses or rank -shifted clauses i.e. a

defining relative clause.

Trench (1996) discusses instances of marked tonality:

I.

Two clauses may fit into a single intonation unit as in

/I He did. I saw it /I

2.

A clause may be said in a single intonation unit as

/I He spoke to me honestly 1/- (neutral case)

or the clause may be broken into separate units;

/I He spoke to me /I honestlyl/- (marked case)

3.

He talks of lists. A list is a special kind of long clause and each item is

treated in a separate unit.

All the intonation units are marked instances as they are less than a

clause.

/I We want red /I white II and blue flags please /I

4.

Marked theme - This is an instance of deviation to the structure of a

clause where a clause element precedes the subject and that element

becomes the theme. instead of the subject.

If anything precedes the

subject, then that takes over the role of theme and such cases of marked

theme always have a separate intonation unit as they are cases where a

tone group is less than a clause.

/I Last night 1/ you came in too late /I

88

But a marked theme can also have a neutral tonality as in the following. e.g

II If you go out in the evening II I want you in by eleven II

Here each clause, the dependent clause and the main clause has its own intonation unit.

5.

Adjuncts - Addition of certain kinds of adjuncts either at the beginning or in

the middle of a clause can be instances of separate tone groups.

If these

adjuncts appear at the end of the clause, they may either have an intonation unit

of their own or be incorporated into the preceding clause. Adjuncts that affect

tonality are linking adjuncts like however, nevertheless. perhaps, of course,

unfortunately, etc.

II He ran the mile II however II in four minutesll

Vocatives also take separate intonation units likeII Miss Smith I can you come with me II

6.

Tags - Tags generally have their own intonation unit. but we can make a

distinction between checking tags and copy tags. Checking tags, i.e. those with

reverse polarity have a separate intonation unit as they are separate clauses and

are cases of neutral tonality.

II John's going out II isn't hell

Copy tags, i.e. those with identical polarity, do not necessarily require a

separate intonation unit if it forms a part of a falling tone. It will then be a case

of marked tonality as the intonation group will be more than a clause.

Checking tags can however be accompanied by either a falling or a rising tone

with a change of meaning. Copy tags accompanied by a rising tone will form

separate intonation units.

II John's going out II i!! he II - neutral tonality (Rising tone)

II John going out is he II

- marked tonality (Falling tone)

Tench (1996) has also observed that intonation units have an average of between two

and three feet each i.e. two or three word stresses. The usual maximum number of

stresses in an intonation unit is fIve and this corresponds to the maximum number of

89

elements in a single simple clause: subject, verb, direct object, indirect object and

adjunct, e.g.

/I The 'office 'sends the 'students their' grants in Oc'tober II

This sentence can be said as one unit of intonation or one unit of information but it

reaches the maximum of five feet, if a clause breaches that maximum number it is

automatically converted into two or even more intonation units.

4.6 Instances of Marked and Neutral Tonality in AE

Instances of Neutral and Marked Tonality have been found in the following selections

in this study I.

Out of 3124 TGs taken up from the data, 860 TGs conform to neutral tonality

and 2264 TGs conform to Marked Tonality. Of the marked form 2181 TGs

conform to cases where the tone group is less than a clause and 83 TGs conform

to cases where the tone group is more than a clause.

DATA

TYPE

Sentences

Dialogue

Passage

Free

Speech

G. Total

N

%

L

%

M

%

Total

%

258

379

56

167

30

44.07

6.51

19.42

331

387

821

642

15.18

17.74

37.64

29.43

17

20.48

24.09

12.05

43.37

606

786

887

845

19.40

25.16

28.39

27.04

860

2181

20

10

36

83

3124

Table 4.1 Composite Table showing the Neutral and Marked Tonality in AE 3

Note: N= Neutral: L= Less than a clause: M= More than a clause. where Land M represent

Marked Tonality

3

90

2.

Cases where one clause fOnTIS one tone group are instances of neutral tonality.

Example 1:

50Hz-250Hz

/ /2 could you/wait for I some! TTh1Ej J

/ /2 and/ let mel fInish my/ WORK/ /

Speaker

HN9MA (neutral tonality)

Clause(s)

Could you wait for some time and let me finish my work.

TGs

// 2 could you / wait for / some / TIME // 2 and / let me / finish

my/WORK//

Example 2:

70Hz·2ooHz

; .11. this is ajvery/serious/THREAT:, /

Speaker

CG3UA (neutral tonality)

Clause(s)

this is a very serious threat

TGs

//2 this is a / very / serious / THREAT //

91

Example 3:

70Hz-250Hz

! /2 my/family is a/total; Assamese/FAMily 1/

Speaker

CG3UA (neutral Tonality)

Clause(s)

my family is a total Assamese family

TG

112 my I family is a I total I Assamese I FAMily II

Example: 4

I used to sing aa ..

I IOHz-500Hz

/ ! I I / used 10

j S~G

aa .. / /

Speaker

HD20LA (Neutral Tonality)

Clause(s)

I used to sing aa ..

TG

II I I I used to I SING aa .. II

The above is an example where one clause forms one tone group and this clause may

contain within it embedded clauses is an instance of neutral tonality

92

Example: 5

Speaker

NB2UA (checking tag in separate TG- neutral tonality)

Clause(s)

It's pleasant today, isn't it?

TGs

III

A

it's I PLEAsant I today 1/1 isn't I IT 1/

(For more examples refer to Appendix IV)

3. Cases of Marked tonality where the tone group is more than a clause, can be found

in the following Examples: (i) when there is a coordinating conjunction between the

clauses (ii) when coordinating conjunction occurs within a clause (between words)

(iii) short clauses accruing in the same tone group.

Example: 1

Speaker

NB2UA (marked tonality: more than a clause)

Clause(s)

I like to play guitar and sing.

TGs

1/1 I/like to I play I gui I TAR and I sing 1/

It is an example of a coordinating conjunction between the clauses.

93

Example: 2

120Hz-lOOHz

1/2 father and/Illother and/I am the/only jDACGHler!

Speaker

HD20LA (Marked Tonality: more than a clause)

Clause(s)

Father and mother and I am the only daughter

TG

112 father and 1m other and I I am the I only I DAUGHter II

In the above example. coordinating conjunction occurs within a clause.

Example: 3

---------

d---~------~

~~----------+_~_t:.

1/1 actually/I/"fead toj'W'RITEj

Speaker

PB 12MA (Short Clauses accruing in the same TG)

Clause(s)

Actually I read. to write

TG

II actually I I I read to I WRITE II

The above is an example of Marked Tonality; Short Clauses accruing in the same TG

4.

Cases of marked tonality where the tone group is less than a clause (i)

One of the constituents of a clause may occur in a separate tone group like

the subject and predicate. verbal element and the complement or the

adjuncts.

(ii)

Presence of marked theme

(iii) Listing items

94

(iv)

Elliptical clauses, utterances used for emphasis and for description of an

item I word

(v)

Checking questions, vocatives, wh-relative pronouns, personal pronouns,

conjunctions,

conditionals,

adverbials,

responses,

inteIjections,

interpolations, prepositions, articles.

Examples of less than a clause:

Example 1

Speaker

PH4UA (marked Tonality: less than a clause)

TGs

1/ 2 our I CO rruptions 1/2 our I LE tbargy 1/ 2 our I Idleness 1/

I and our I think I ING 1/

Example: 2

Speaker

PB 12MA (marked Tonality: less than a clause)

Clause(s)

you just get the car out of the garage for me

TGs

1/2 you I JUST 1/ L get the ICAR 1/ L out of I THE 1/1 garage I

FOR me 1/

95

Example: 3

30Hz·250Hz

I III am/D,ing in/SARthebaril I

I II till I tol DAYI I

Speaker

PS 17LA (marked theme a separate TG)

Clause(s)

Till today, I am living in Sarthebari.

TGs

1/ I till / to / DA Y 1/ I I am / living in / SARthebari 1/

Example: 4

would you / like to /

Speaker

NB2UA (listing items indicating TGs)

Clause(s)

would you like to have tea, coffee or juice.

TGs

1/2 would you / like to / have / TEA 1/2 Coffee 1/ 2 A or /

JUICE 1/

96

Example: 5

...

__ 0....

!tt

Its no good :Mary

70Hz-250Hz

I IR+F Itsl NO I GOOD I I

II 2 MAry II

Speaker

RS8MA (Vocative said as a separate tone group)

Clause(s)

Its no good Mary.

TGs

II R+F Its I NO I GOOD II 2 MAry II

Example: 6

I think. about

80Hz-250Hz

I I I I;THlNKl I

12 a/BOFf I I

Speaker

PB l2MA (Interpolation and preposition marking tone groups)

Clause(s)

I think, about

TGs

1/1 II THINK II 2 a I BOUT II

97

Example: 7

70Hz-250Hz

I II basi I CALIyI I

Speaker

NB2UA (Adverbial as a separate tone group)

Word

Basically

TG

1/ I Basi / CALly II

Example: 8

70Hz-250Hz

IlL ACmalll' I!

II

R~F

1 have I plenty of I HOB

l

BlESI I

Speaker

NB2UA (Adjunct as a separate Tone Group)

Clause(s)

Actually I have plenty of hobbies

TGs

1/ L ACtually 1/ R+F I have / plenty of / HOB / BIES 1/

98

Example: 9

The C.aI won't start.Won't start

50Hz-350Hz

/!2 won't/STA

III thejcar/\\'on',/STARTj /

Speaker

YR 16LA (Elliptical Clause in separate Tone Group)

Clauses

The car won't start, Won't start,

TGs

III the / car I won't I START 112 won't I START II

Example: 10

40Hz-250Hz

112 early / in the 1 MORKingl/

Speaker

RS8MA: (marked Tonality: less than a clause)

Clause(s)

early in the morning

TG

112 early I in the I MORNing II

4.6.1 Summary

In cases of neutral tonality it is observed that a speaker generally makes a tone group

where it coincides with some grammatical item. The theory specifies that a speaker-s

99

perception of their organization of information is in the form of a single unit of

intonation, which is typically within a single clause. So where there is a congruence of

semantic, phonological and grammatical units, tonality is neutral where there is not,

tonality is said to be marked.

4.7 Role of Tonality in the Information Function of Intonation

Halliday (1967) refers to Information Distribution where one information unit in a TG

IS

tonality neutral;

/I I saw John yesterday II

breaking up a TG into two information units is tonality marked;

/I I saw John II yesterday II

The system of information distribution can be represented also as:

Inform~

distribution

-~

Unmarked

(conflated with a clause)

Marked

(conflated with anything else)

The distribution of information is unmarked if the information unit is conflated with a

clause. Information distribution is marked if it is conflated with any other grammatical

unit.

Tench (1996) also talks about tonality in relation to the informational function of

intonation. He relates tonality with grammatical structures to show that changes in

tonality brings about changes in the information distribution as is mentioned in the

following I.

Defining and non-defining items:

I.

1/ My brother who lives in Nairobi II ... and

II.

II My brother /1 who lives in Nairobi /I ...

100

In the first instance (i) the relative clause defines which brother is meant, it restricts the

reference to mean not the brother living anywhere else.

In the second instance (ii) the relative clause does not define the brother but only adds

extra information i.e. it does not restrict the reference. This type of adding clauses or

non-defining clauses are singled by the tone group boundary after the subject.

In another sentence like 1/ The man with the dog sitting near the bus stop II and

1/ The man with the dog /I sitting near the bus stop /I

The first sentence suggests that it is the dog that is doing the sitting, as the sitting

defines which dog is meant. The second sentence suggests that it is the man who is

sitting near the bus stop. It is additional, non-defining information. The tone group

boundary is performing a grammatical function and also affecting the meaning.

2.

Apposition: Apposition is the relationship between two or more items which

are either identical in reference or else the reference of one must be included in

the reference of the other.

In a sentence like Tom Jones, the singer, comes from South Wales.

There is identity of reference between the two appositional items Tom Jones

and the singer. The sentence can be said as /I Tom Jones the singer /I comes from South Wales /I

the tone group boundary after singer identifies which Tom Jones is meant,

since in South Wales there are hundreds of Tom Joneses. If the sentence is said

as /I Tom Jones /I the singer 1/ comes from South Wales /I

101

in this case the singer is added as extra information. The distinction between

defining and non-defining apposition is thus indicated by intonation in the

spoken mode.

Quirk et al. (1972: 626-7) cite three cases of potential ambiguity between

instances of apposition and the more complicated types of complementation.

The first example cited is II They sent Joan a waitress from the hotel II

As a single intonation unit, the sentence would be interpreted as a waitress

from the hotel being sent to Joan i.e. as a double transitive clause. Joan as an

indirect object, a waitress from the hotel as direct object.

If we put a tone group boundary after Joan,

II They sent Joan II a waitress from the hotel II

In this case, Joan is the waitress from the hotel. But if we add a second boundary after

waitress,

II They sent Joan II a waitress II from the hotel II

The meaning here would be, Joan is still a waitress, but now she is sent away from the

hotel. Tonality is doing both grammatical and informational work in this case.

Apposition may take the form of clauses as well as noun phrases and in many cases

clauses

In

apposition

become

relative

clauses.

Examples

et aI., (1972: 645-8)

I.

II They put it where it was light II Where everybody could see it II

2.

II He told them the news II that the troops would be leaving II

These are cases of non-defining apposition.

102

from

Quirk

Apposition may also take the fonn of other clause elements like

(i)

Predicates (Examples from Quirk et.a\., (1972:645-8).

/I They summoned help II called the police and fire brigade II

(ii)

Complements

II She is better II very much better II

(iii)

Adjuncts

II Thirdly II and lastly II they would not accept his promise /I

3.

About Syntactic Structure:

Different tone group boundaries affect the interpretation of syntactic structure. For e.g.

II He died a happy man II (subject complement)

II He died II a happy man II (apposition, implying 'he'd always been a

happy man')

4.

Verb Phrases:

A verb phrase can be simple: with a single lexical verb; or complex: with more than

one lexical verb.

For e.g. (you must) try to stop smoking. Some complex verbal

phrases look very similar to a series of verbs (i)

He began smoking

(ii)

He began to smoke

(iii) He stopped smoking

(iv)

II He stopped II to smoke II

The (iii) and (iv) verbal phrases look as if parallel to the verbal phrases (i) and (ii).

The pair (i) and (ii) have different structures but share broadly the same meaning. The

verbal phrase (iii) is the opposite of (i) and (ii).

The phrase in (iv) may look

superficially the parallel to (ii) but have a different structure and meaning. In (iv) there

are two simple verb phrases, the first belongs to a main clause and the second to the

following purpose clause which when read as in order to smoke. will make the

meaning clearer. As (iv) consists of two clauses. neutral tonality exists i.e. two clauses

and so two tone groups.

103

In another example -

(i)

/I He left me to get on with the job /I and

(ii)

/I He left me II to get on with the job /I

Sentence (i) has a single though complex, verbal phrase: one clause and one intonation

unit whereas (ii) is a series of two clause i.e. main clause followed by a purpose

clause, has two intonation units. The tone group divisions in each sentence have a

difference in meaning too.

5.

Negative domain: Tonality plays the crucial role of differentiating two syntactic

structures and meaning in case where the main clause has a negative and is

followed by because and a reason or by so (that) and a result. An utterance such

as 'I didn't come because he told me',

said as two intonation units with one

clause each (neutral tonality) would make the meaning quite clear: the person did

not come, and a reason for not coming is added:

/I I didn't come /I because he told me /I

If however the two clauses are uttered in a single intonation unit (marked tonality),

implies: the person did go, but not for the reason that is given- he went for some other

reason:

/I I didn't come because he told me /I

This seems to be the case that the domain of the negative extends to the next tonality

boundary; thus in first sentence it is come that is negativized but in the second sentence

it is because he told me that is negativized.

Thus in the case of Marked Tonality, the negative

IS

transferred to the following

clause.

6. Report clauses: In these clauses there is an initial verb of reporting and a clause

containing the context of what is

reported~

104

The two parts are usually linked by a

conjunction e.g. that, whether, if_but the that conjunction may be omitted. The

two parts can be regarded as a single clause consisting of the main verb of

reponing and a (rank shifted) clause as the direct object complementing the

reporting verb. Even if the reponing verb is at the end, a single tone group is

sufficient. e.g.

II I reported that they had taken a decision II

II They had taken a decision, I reported II

The difference between report clauses and direct speech can be brought out by

intonation. e.g.

II He said he would come II - report clause

II He said II I'll come II - direct speech

Report clause structures with know can be distinguished from linking adjuncts like you

know by tonality.

II You know its important II and

IIYou know II it's important II

you know is acting as a means of linking a previous utterance with the new one in the

following main clause.

7.

Clause Complements: Intonation helps in distinguishing between transitive and

intransitive verbs.

(i)

II She washed and brushed her hair II

(ii)

II She washed II and brushed her hair II

In sentence (i) her hair is the direct object complementing both the verbs washed and

brushed. thus washed (and brushed) is transitive. In sentence (ii) washed is intransitive,

as the tone group boundary separates that verb from the other elements and hair is the

direct object complementing brushed only. Here only brushed is transitive. The

105

meaning conveyed is 'she washed herself but not her hair'.

Therefore intonation

brings out a difference in meaning in these grammatical items.

In another e.g. 1/ They've left 1/ the others 1/

In this case, the others is the 'real', but displaced, subject, conveying the meaning, 'the

others have left (actually),. To leave is a verb which can be either intransitive or

transiti ve as in 1/ They've left the Qthers 1/

In this case the others is the direct object complementing left. Intonation, therefore,

brings out the grammatical difference.

Regarding the functional equivalence between a tone group and an information unit,

Halliday says that the tone group is a unit of information and the speaker decides how

to break up the message into units of information but these units of information may

not always contain much, in the way of information. Units may often contain

exclamations like wow' , My goodness me! , I mean, you see, etc. Tench (1996)

therefore feels that the term unit of information has to be defined relatively broadly: it

is the semantico-phonological unit for the development of discourse, which handles

not only information or propositional context but also markers of style, expressions of

attitudes and feelings, 'running repairs' or 'phatic communion' like Good morning and

How do you do? and politeness formulas like please, thank you and don't mention it.

(Tench 1996:51)

In this study the role of Information Structure is determined by certain grammatical

criteria cited through worked out examples4 following below:

L\

Please refer to Appendix II for the conte:x{ of the example~

106

Example: 1

60Hz-200Hz

/ /1 which is/ one ofthejmain/SOCRces of,!,1 1 pollution of / WAter/I

Speaker

YR 16LA (Non-defining Relative Clause uttered in more than

one Tone Group)

Clause

Which is one of the main sources of pollution of water

TG(s)

III which is lone of the I main I SOURces of II I pollution of I

WAter II

Example: 2

...

v.-!Uch uses oxygen for decomposition

;3)

Speaker

TG7UA (Defining Relative Clause in a TG)

Clause

which uses oxygen for decomposition

TG

III which I uses I oxygen I for I de I COMposition II

107

Example: 3

1/1 which; uses/oxy I GEN II

I de/COMposition/ /

Speaker

NNRI4LA (Defining Relative Clause in more than one TG)

Clause

which uses oxygen for decomposition

TGs

1/ I which I uses I oxy I GEN !II FOR 1/ I de I COMposition 1/

Example: 4.

looHz·3ooHz

/121"11 come/,,;th! YOUII

III if you I LIKE II

Speaker

DBIUA (Conditional Clause in a separate Tone Group)

Clause(s)

1"11 come with you if you like.

TGs

1/ 2 I'll I come I with I YOU 1/ I if you I LIKE 1/

108

Example: 5

30Hz-300Hz

i-U ICmlEl1

III "ithl YOt: II

III ifyoll/LIKEl1

Speaker

RS8MA (Conditional Clause uttered in several Tone Groups)

Clause(s)

I'll come with you if you like

TGs

112 i'll I come II I with I YOU II I if you I LIKE II

Example: 6

~·fen

always are.I suppose

100Hz-500Hz

L-_ _/~·/~L~n~le~n~/aJ_/~,,~·a)~.,~/ARE_~,~,_ _---'L-_ _ _ _ _--L_~/~II~s~up~!~·P~0~SE~/~/_Jfi5i

Speaker

HD20LA (Elliptical Clause in separate Tone Group)

Clauses

Men always are. I suppose.

TG

II L men I al I ways I ARE II I I sup I POSE II

109

Example: 7

70Hz-250Hz

I have been ! working I HERE / /

Speaker

//1 TEN/month, / ;

//1 !or;L\ST a..//

NB2UA (using present perfect continuous tense and Time ad

verbiaI in separate TGs)

Clause(s)

I have been working here for last a ten months

TGs

II L I have been I working I HERE II I for I LAST a.. II I TEN

I months II

Example: 8

50Hz-250Hz

/ / 2 India is a /diYer5e / country you /

Speaker

K.~OW

1/

DNIOMA (,You know' as an Adverb meaning 'Do you know'

in the same TG)

Clause(s)

India is a diverse country you know

TG

II 2 India is a I diverse !country you I KNOW II

110

Example: 9

130Hz-450Hz

112 ii mINKll

Speaker

HD20LA (Discourse fillers as a separate Tone Group)

Clause

I think

TGs

112 i I THINK II

Example: 10

70Hz-350Hz

112 i I LIKEII

Speaker

/ 12 tolperformlSOMEl1

DO l3MA (Verb phrases as Discontinuous information marked

off as a separate T G )

Clause(s)

I like to perform some

TGs

112 i I LIKE 112 to I perform I SOME II

111

Example: 11

45Hz-250Hz

1/2 I can/composejSOI\GSj!

Yes/ Assamese/SONGS/

Speaker : HN9MA (An utterance used for emphasizing the information given

earlier said as a Tone Group)

Clause(s)

I can compose songs, Yes Assamese songs

TG

112 I can I compose I SONGS II 2 yes I Assamese I SONGS 1/

Example: 12

1/2 and / my Isecond I

SO~/!

! /1 he is/in / dur/GApur/ /

Speaker

RDI9LA (consecutive use of subjects in separate TGs)

Clause(s)

And my second son. he is in Durgapur.

TGs

/12 and / my / second / SON II I he is I in I dur I GA pur /1

112

Example: 13

70Hz-230Hz

/ /1 She is a /coTIegej SITdentj /

Speaker

III She is/studying atjTihu / COllege!!

MS 18LA (Sentence as a separate Tone Group giving additional

infonnation instead of an Adjective Clause)

Clause(s)

She is a college student. She is studying at Tihu college.

TGs

II I she is a / college I STUdent II I she is I studying at I Tihu I

COL lege /1

Example: 14

30Hz-180Hz

my!fafherha~

;expired,l ON

Twenty jsecond/Xovember two I

Speaker

HN9MA (Time Adverbial as a separate Tone Group)

Clause(s)

My father has expired on 22 nd November 2005

TG

II L my I father has I expired I ON II 2 twenty I second I

November two I thousand and I FIVE I/Pretonic: neutral

113

Example: 15

110Hz-500Hz

1/ III used.o I SING ... ! /

Speaker

HD20LA (use of used to Structure in a Tone Group)

Clause(s)

I used to sing aa ..

TG

II I I I used to I SING aa .. II

Example: ]6

60Hz-250Hz

/;2 Yes / I / like.o / play / GAMES! /

Speaker

DB I VA (Non-finite: Infinitive in a TG)

Clause(s)

Yes I like to play games

TG

112 Yes I I I like to I play I GAMES II

114

Example: 17

80Hz·250Hz

/ / I I like / rea / DING and / I

Speaker

MJH5UA (Non-finite; Gerund in a Tone Group)

Clause(s)

I like reading and

TG

1/ I I like I rea I DING and 1/

Example: 18

Actually my hobby is reading

9OHz·250Hz

/ /] actually my I hobby I IS / /

Speaker

TG7UA (Non-finite clause; Gerund in separate Tone Group)

Clause(s)

Actually my hobby is reading

TG

1/ 2 actually my I hobby I IS 1/2 rea I DING 1/

4.7.1 Summary

The study of the textual function of tonality in AE, in the organization of information

structures and in distinguishing between grammatical structures, has revealed that

Assamese English speakers make separate TGs for certain grammatical structures like

conditional clauses. relative clauses, elliptica! clauses. non-finites. adverbials

115

(especially time adverbials), present perfect tense, used-to structures, verbals,

nominals, discourse fillers, marked themes, comment adjuncts etc. There are also

instances where speakers use these constructions within TGs. This erratic system of

AE intonation: System of Tonality does not bring about distinct differences in meaning

and grammar of these syntactic choices. This may lead to loss of information and

impair intelligibility to a great extent.

116