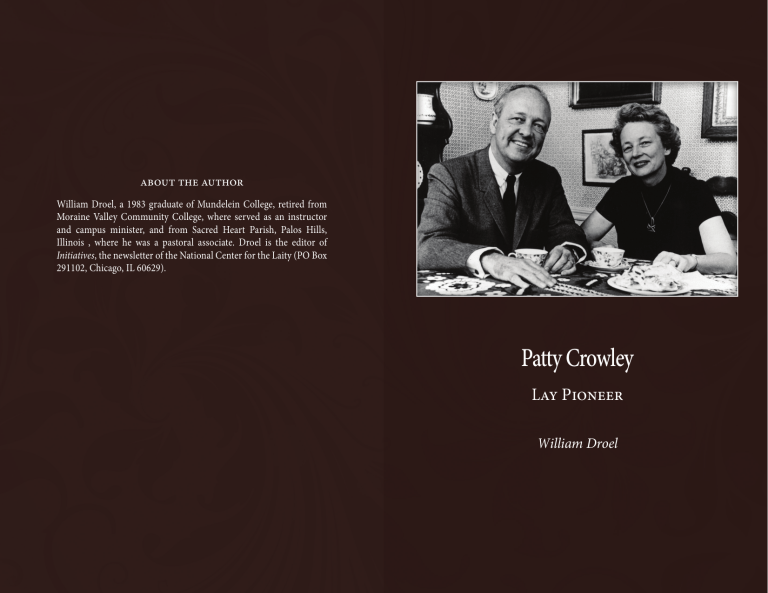

Patty Crowley: Lay Pioneer Biography by William Droel

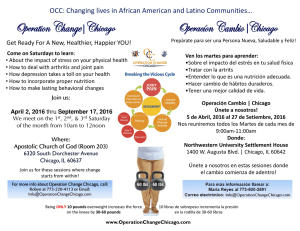

Anuncio