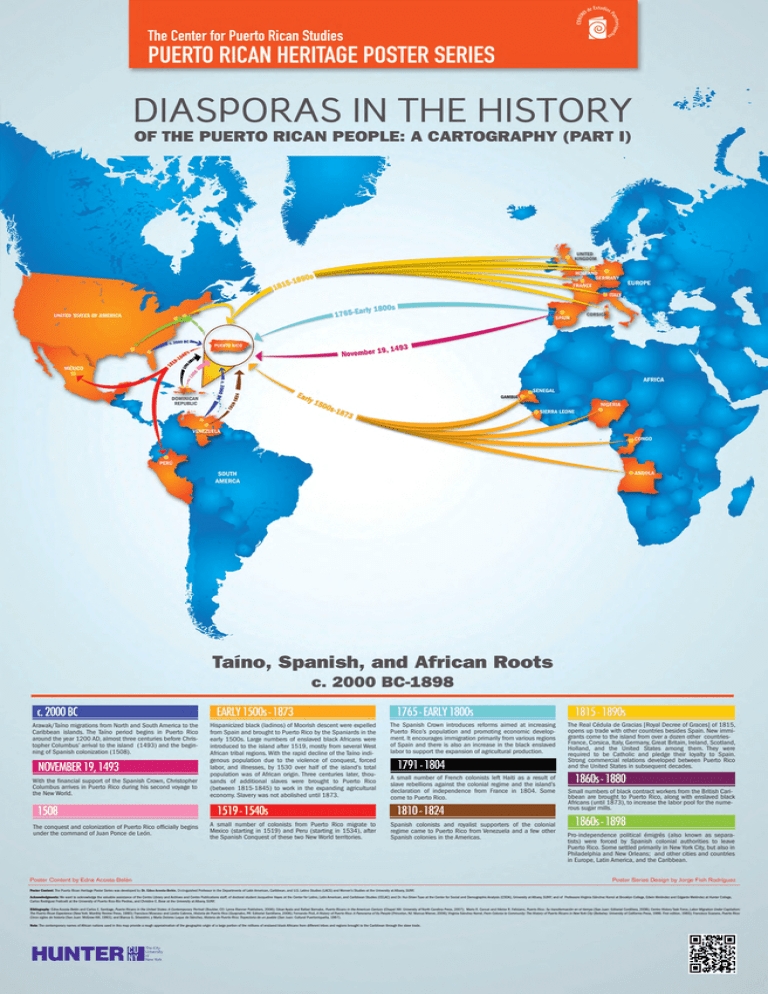

Iaino, Spanish, and African Roots c. 2000 BC

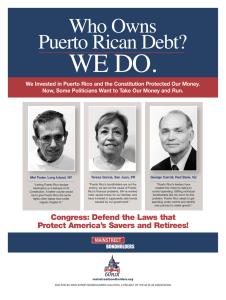

Anuncio

OF THE PUERTO RICAN PEOPLE: A CARTOGRAPHY (PART I) • I e._~e ..r\y 1800s 116.,..._.. ; November 19,, 1493 I "" DOMINICAN REPUBLIC N ·~ .. Iaino, Spanish, and African Roots c. 2000 BC-1898 EARLY 1500s -1873 c. 2000 BC Arawak/Tafno migrations from North and South America to the Caribbean islands. The Tafno period begins in Puerto Rico around the year 1200 AD, almost three centuries before Christopher Columbus' arrival to the island (1493) and the beginning of Spanish colonization ( 1508). NOVEMBER 19 1493 With the financial support of the Spanish Crown, Christopher Columbus arrives in Puerto Rico during his second voyage to the New World. Hispanicized black (ladinos) of Moorish descent were expelled from Spain and brought to Puerto Rico by the Spaniards in the early 1500s. Large numbers of enslaved black Africans were introduced to the island after 1519, mostly from several West African tribal regions. With the rapid decline of the Tafno indigenous population due to the violence of conquest, forced labor, and illnesses, by 1530 over half of the island's total population was of African origin. Three centuries later, thousands of additional slaves were brought to Puerto Rico (between 1815-1845) to work in the expanding agricultural economy. Slavery was not abolished until 1873. 1519-1540s The conquest and colonization of Puerto Rico officially begins under the command of Juan Ponce de Leon. A small number of colonists from Puerto Rico migrate to Mexico (starting in 1519) and Peru (starting in 1534), after the Spanish Conquest of these two New World territories. 1765- EARLY 1800s The Spanish Crown introduces reforms aimed at increasing Puerto Rico's population and promoting economic development. It encourages immigration primarily from various regions of Spain and there is also an increase in the black enslaved labor to support the expansion of agricultural production. 1791-1804 A small number of French colonists left Haiti as a result of slave rebellions against the colonial regime and the island's declaration of independence from France in 1804. Some come to Puerto Rico. 1810-1824 Spanish colonists and royalist supporters of the colonial regime came to Puerto Rico from Venezuela and a few other Spanish colonies in the Americas. Poster Content by Edna Acosta-Belen The Real Cedula de Gracias [Royal Decree of Graces] of 1815, opens up trade with other countries besides Spain. New immigrants come to the island from over a dozen other countriesFrance, Corsica, Italy, Germany, Great Britain, Ireland, Scotland, Holland, and the United States among them. They were required to be Catholic and pledge their loyalty to Spain. Strong commercial relations developed between Puerto Rico and the United States in subsequent decades. 1860s- 1880 Small numbers of black contract workers from the British Caribbean are brought to Puerto Rico, along with enslaved black Africans (until 1873), to increase the labor pool forthe numerous sugar mills. Pro-independence political emigres (also known as separatists) were forced by Spanish colonial authorities to leave Puerto Rico. Some settled primarily in New York City, but also in Philadelphia and New Orleans; and other cities and countries in Europe, Latin America, and the Caribbean. Poster Series Design by Jorge Fish Rodriguez Poster Content: Th e Puerto Rican Heritage Poste r Series was deve loped by Dr. Edna Acosta-Belen , Distinguished Professor in the Depa rtm ents of Lati n American, Caribbean, and U.S. Latino Studies (LACS) and Women's Studies at the University at Albany, SUNY. Acknowledgments: We want to acknowledge the valuable assistance of the Centro Li brary and Archives and Centro Publications staff; of doctora l student Jacqueline Hayes at the Center for Liltino, Liltin American, and Caribbean Studies (CELAC) and Dr. Hui-Sh ien Tsao at the Center for Social and Demographic Analysis (CSDA), University at Albany, SUNY; and of Professors Vi rginia sanchez Korrol at Brooklyn Col lege, Edwin Meliindez and Edgardo Melendez at Hunter Col lege, Carlos Rodriguez Fraticel li at the University of Puerto Rico-Rio Pied ras, and Christi ne E. Bose at the University at Albany, SU NY. Bibliography: Edna Acosta -Belen and Carlos E. Santiago, Puerto Ricans in the United States: A Contemporary Portrait (Bou lder, CO: Lynne Rienner Pub lishers, 2006); cesar Ayala and Rafael Bernabe, Puerto Ricans in the American Century (Chapel Hi ll: University of North Carolina Press, 2007); Mario R. Cancel and Hector R. Feliciano, Puerto Rico: Su transformaci6n en e/ tiempo (San Juan: Editorial Cordillera, 2008); Centro History Task Force, Labor Migration Under Capitalism: The Puerto Rican Experience (New York: Monthly Review Press, 1980); Francisco Moscoso and Uzette Cabrera, His tori a de Puerto Rico (Guaynabo, PR : Editoria l Santil lana, 2008); Fernando Pic6, A History of Puerto Rico: A Panorama of Its People (Princeton, NJ: Marcus Wiener, 2006); Virginia sanchez Korrol, From Colonia to Community: The History of Puerto Ricans in New York City (Berkeley: University of Ca lifornia Press, 1986. First edition, 1983); Francisco Scarano, Puerto Rico: Cinco siglos de historia (San Juan: McGraw- Hill, 1993 ); and Blanca G. Silvestri ni, y Maria Do lores Luque de sanchez, Historia de Puerto Rico: Trayectoria de un pueblo (San Juan: Cultura l Puertorriquefia, 198 7) . Note: lhe contemporary names of African nations used in th is map provide a rough approximation of the geograph ic origin of a large portion of the millions of enslaved black Africans from different tribes and regions brought to the Caribbean through the slave trade.