Ministerial Formation, issue 100, January 2003

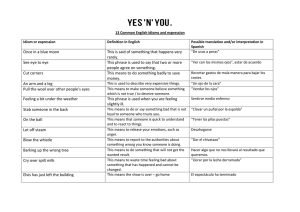

Anuncio