Veinte poemas de amor y una canción desesperada A PUPIL`S

Anuncio

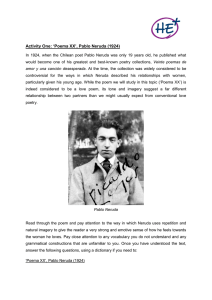

Veinte poemas de amor y una canción desesperada A PUPIL’S COMMENTARY ON POEM 5 In this poem, Neruda addresses the idea of creativity and the effects of the woman and his wavering emotions, often the result of interaction with the woman, on his creative spirit. Here, the idea of not being able to clearly express emotions is explored as the poet admits that he cannot verbalise his emotions. Yet, despite claiming that the woman detracts from his creativity, throughout the poem Neruda expresses a true yearning for her – as seen in the way that he commences the poem with “para que tu me oigas”, suggesting that he wants her to hear him and for them to connect, similarly to poem 15 where he laments the fact that they are separate in the line “mi voz no te toca”. Initially, the focus of the poem – his creativity and thus his “palabras” - is highlighted by the emphatic placement of “mis palabras” on its own in the opening stanza. Additionally, the reflexive use of “adelgazarse” introduces the notion that his words have a life of their own – a theme that is explored throughout the rest of the poem. The following couplet introduces the “collar” as a metaphor for his words which are strung together like a necklace. Furthermore, the placement of “cascabel ebrio” is emphatic as a drunken bell is nonsensical in contrast with a perfectly stringed together necklace – this contrast is introduced to show the contrast between how the poet perceives himself in the state of not being able to connect his thoughts, and what he aims to be. The use of the comma between the two images also creates a caesura for dramatic effect and helps make the distinction between the two states of creativity clear. Conversely to the usual subordination of the woman throughout the anthology, the following stanza sees the woman as empowered, having an effect on the author. This is clearly demonstrated by the contrast between the emphatic repetition of “mis...mias...mi”, which link together the stanza and place the focus on Neruda, and the claim that his words “mas que mias son tuyas”: here he admits to the effect that she has on him as she has a large degree of influence over his creativity. Finally, the use of “viejo dolor” sees the poet associate love with pain, reminiscent of his reference to “mi dolor infinito” in poem 1. Yet, the sexual connotations of “paredes humedas” remind us of the physical emphasis of the anthology and Neruda’s obsession with physical encounters. However, in contrast to the descriptions of the woman as “muneca” in poem 3 and “mariposa” in poem 15, here the words “eres tu la culpable” see Neruda blame the woman for his lack of creativity, again attributing a degree of importance to her. The association of love, which is meant to be simple and beautiful as the “anillo” metaphor of poem 15, with pain continues in this couplet as he refers to it as the “juego sangriento”. The use of “juego” further implies that she is in a way manipulative. Moreover, the placement of sangriento at the end of the line is emphatic as it disrupts the “as” ending of words at the end of the line and thus disrupts the rhyme scheme, drawing attention to it. 1 In the following couplet, the use of “huyendo” links with poem 1 where, through the statement “de mi huian los pajaros”, Neruda describes his isolation from nature. Whereas before nature fled from him, now his words flee from him. As a reflection of this, the use of “oscura” adds to the sense of Neruda’s dark and negative emotions. Next, the poet claims that his words used to fill the solitude which she now occupies, showing us that although he craves the woman, his solitude inspires his creativity. Again, the use of “tristeza” builds on the negative sense introduced by “oscura”. The change of tense of “ahora” is important in that it signifies a change of the author’s intention. However, the woman nonetheless remains at the centre of his thoughts. The awkward nature of the phrasing of this couplet reflects his inability to express his emotions due to the lack of creativity which he is describing, and which he says she has brought about. Indeed, by writing in such effortful fashion, he illustrates the expressive difficulty which is the subject matter of the poem. Yet, the anaphora of “quiero” reminds us of the self-centred nature of his poetry as the emphasis is on him. The gust of wind that follows is sudden and disorientating to reflect the unpredictability of his own wavering emotions. Neruda’s anguish and torment are shown to dramatically increase as “viento de la angustia” turns to “Huracanes” with the hyperbolic reference to hurricanes showing the extent to which he is frustrated by his lack of creativity. Once again, Neruda is equating his creative impulses with nature and arguing that creativity is natural and untameable. The use of “voz dolorida” once more links with the “viejo dolor” and the “dolor infinito” of poem 1, seeing Neruda associate the woman and relationships with pain. Similarly, the use of “llanto” further introduces an aspect of lament and sadness to the poem. Yet, although Neruda seems to blame the woman for his lack of creativity, he nonetheless says “amame, companera. No me abandones. Sigueme” showing that he wants to be with the woman and is in a torn and confused state as whilst he wants her gone for the sake of his creativity, he also dislikes solitude and craves company. This is emphasised by the use of the tricolon of imperatives which show the forcefulness of his desire as well as the punctuation which disrupts the rhythmical flow of the poem, drawing attention to the line and the commands expressed. Certainly, the disconnected statements created by the asyndeton of verbs embody the height of the storm. The anadiplosis of “sigueme” further emphasised his innate desire for company. The use of “companera” to refer to the woman is also more endearing than other ways she is described throughout the anthology, such as “hembra distante y mia” in poem 7, as it shows that he views her as a companion rather than just a female, with whose physical nature he is obsessed. Finally, the “ola de angustia” refers back to the “viento de la angustia” and again evokes the sense that Neruda associates his emotions with nature, as they are unpredictable and untameable. As such, Neruda highlights that feelings aren’t logical: when he is lonely, such as in poem 7, he craves company however, in this instance, when he has company he is nevertheless unhappy with it. Thus, his inner emotional turmoil is similar to tumultuous wind. Here, this being the longest stanza is particularly poignant in the build up of emotion. 2 Subsequently, the assertive “pero” symbolises where the poet regains control following the storm and equilibrium is restored. The “todo lo ocupas tu, todo lo ocupas” refers back to the idea of the woman filling up all of Neruda’s creativity as his words are tainted by his love. Yet, the use of “ocupas” instead of “llenas” is important as whilst earlier the woman’s presence overpowered him and he was left with no space for creativity, now a sense of harmonious accommodation is created as ocupas suggests that everything is occupying its proper place and he is no longer feeling stifled. As a result of the return to equilibrium, he returns to writing, with the emphatic form “voy haciendo” indicating an actively ongoing action. The “mis...tu” also sees a reversal in the order of repetition before, drawing attention to the role reversal in their relationship. Finally, the use of “blancas manos” is reminiscent of the “blancas colinas, muslos blancos” of poem 1 that characterise her physical nature. The return to rhyming couplets following the long tumultuous stanza further sees a return to calm. Indeed, overall, the absence of a regular alexandrine structure reflects the irregularity and unpredictability of his emotions, and thus his creative impulses. 3