Reivindicar, amplificar, interferir y aumentar.

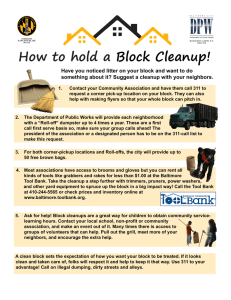

Anuncio