Fundamental Rights Report 2016 - European Union Agency for

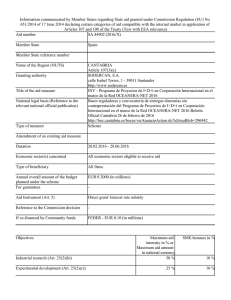

Anuncio