PARÁMETROS POBLACIONALES DE Empoasca kraemeri Ross

Anuncio

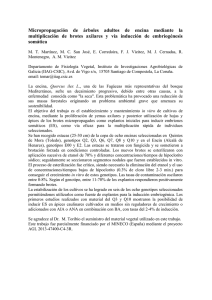

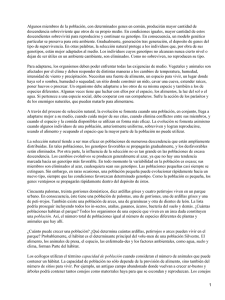

PARÁMETROS POBLACIONALES DE Empoasca kraemeri Ross & Moore (HOMOPTERA: CICADELLIDAE) EN GENOTIPOS DE FRIJOL Empoasca kraemeri Ross & Moore (HOMOPTERA: CICADELLIDAE) POPULATION PARAMETERS IN COMMON BEAN GENOTYPES Víctor Maya-Hernández1, Jorge Vera-Graziano2 y Ramón Garza-García3 1 Campo Experimental Huichihuayán. INIFAP. Apartado Postal Núm. 1. 79890, Huichihuayán, San Luis Potosí. 2Especialidad de Postgrado en Entomología. IFIT. Colegio de Postgraduados. 56230, Montecillo, Estado de México. ([email protected]). 3Campo Experimental Valle de México. INIFAP. Apartado Postal Núm. 10. 56230, Chapingo, Estado de México. RESUMEN ABSTRACT Empoasca kraemeri Ross & Moore es una plaga importante del frijol común (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) en la región oriental de San Luis Potosí. Se había determinado que los genotipos de frijol DOR207, EMP-40(J-H)98, BAT-1636 y BAT-58-2 son resistentes1 a esta plaga con base en una escala arbitraria de clasificación de daño y rendimiento por unidad de superficie, pero se desconocía el efecto de dichos genotipos en los parámetros poblacionales del insecto. Con base en la técnica demográfica de tablas de vida y fertilidad y usando la variedad Negro Jamapa como testigo susceptible, se concluyó que los tres primeros genotipos causaron menor esperanza media de vida y mayor mortalidad de ninfas, así como menores tasas de supervivencia y reproducción en el insecto; BAT-58-2 únicamente causó un efecto menor, pero significativo, en las tasas de reproducción de esta plaga. Empoasca kraemeri Ross & Moore is an important bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) pest in the eastern region of the State of San Luis Potosí, México. It had been determined that the bean genotypes DOR207, EMP-40(J-H)98, BAT-1636 and BAT-58-2 are resistant to this pest, based on an arbitrary scale of classification of damage and yield per unit area, but the effect of these genotypes on the population parameters of the insect was unknown. Applying the demographic technique of life and fertility tables, using the Negro Jamapa cultivar as a susceptible control, it was concluded that the first three genotypes caused a higher mortality of nymphs, a lower mean expectation of life, and lower survival and reproduction rates; BAT-58-2 caused only a minor but significant effect on the rate of reproduction of this pest. Key words: Empoasca kraemeri, Phaseolus vulgaris, fertility tables, life tables. Palabras clave: Empoasca kraemeri, Phaseolus vulgaris, tablas de fertilidad, tablas de vida. INTRODUCTION INTRODUCCIÓN I n the Huasteca Potosina, eastern region of the State of San Luis Potosí, México, about 1250 ha of bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) are sown each year (Rosales and de la Garza, 1992)4. The main pest in this region is Empoasca kraemeri Ross & Moore pest; uncontrolled it causes almost a complete yield loss. The pest disminished considerably the cultivated area, formerly covering up to 10000 ha per year (Rosales and de la Garza,1992)4. E. kraemeri is present during the entire life cycle of the bean. The main damage is caused by nymphs as well as by adults at sucking up the sap, therefore the leaves begin to “crinkle” because of chlorosis and necrosis ( King and Saunders, 1984). Consequently, plant growth is reduced, the flowers fall off, and there is no adequate grain formation (Carrillo and Rodríguez, 1982). When the attack is very intense, the plant dies (Andrews and Quezada, 1989). E n la Huasteca Potosina, región oriental del Edo. de San Luis Potosí, se siembran al año aproximadamente 1250 ha de frijol (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) (Rosales y de la Garza, 1992)4. En esta región la principal plaga es la denominada “chicharrita”, “salta hojas” o “lorito verde” Empoasca kraemeri Ross & Moore, ya que si no se controla puede ocasionar la pérdida casi total de la producción. Esta plaga ha ocasionado que la superficie cultivada haya disminuido considerablemente, ya que anteriormente se sembraban hasta 10 000 ha al año (Rosales y de la Garza, 1992)4. La chicharrita se presenta durante todo el ciclo de vida del frijol. El principal daño lo ocasionan tanto las ninfas Recibido: Julio, 1998. Aprobado: Julio, 2000. Publicado como ARTÍCULO en Agrociencia 34: 603-610. 2000. 4 Rosales A., F. y A. de la Garza N. 1992. Selección de líneas y variedades de frijol con resistencia al ataque de la chicharrita Empoasca sp., bajo condiciones de campo. Ciclos otoño-invierno, 1986-87; 87-88; 89-90; 90-91; 91-92. In: Informe de Avances de Investigación por Proyecto del Programa de Frijol del Campo Experimental Huichihuayán, S. L. P. CIFAP-Pánuco. INIFAP-SARH. Documento Interno. pp: 162-165. 603 604 AGROCIENCIA VOLUMEN 34, NÚMERO 5, SEPTIEMBRE-OCTUBRE 2000 como los adultos al succionar la savia lo que origina el “enchinamiento” de las hojas por clorosis y necrosis (King y Saunders, 1984). Con esto se reduce el crecimiento de las plantas, se caen las flores y no existe una adecuada formación del fruto (Carrillo y Rodríguez, 1982). Cuando el ataque es muy intenso la planta muere (Andrews y Quezada, 1989). El control más frecuente de este insecto es por medio de aplicaciones de insecticidas, que aunque a corto plazo representan la forma de control más práctica y efectiva, a mediano y largo plazo presentan grandes desventajas: intoxicación de trabajadores, aumento en costos de producción, muerte de insectos benéficos, contaminación del ambiente, etc. (Schoonhoven, 1985). Otras alternativas de control son el control biológico, el cultural y el genético mediante la utilización de variedades resistentes (Davison y Lyon, 1992). Con base en lo anterior y considerando que los productores de frijol de la Huasteca Potosina son de escasos recursos económicos, la utilización de variedades resistentes se considera como una opción con grandes perspectivas para el control de la chicharrita del frijol en la región. Los genotipos EMP-40(J-H)98, BAT-58-2, BAT1636 y DOR-207 han demostrado buena adaptación a las condiciones climáticas de la Huasteca Potosina y poco daño en presencia de la chicharrita en esa región, por lo cual se les considera como genotipos que presentan resistencia a esta plaga, según Rosales y de la Garza (1992)4. Estos autores seleccionaron esos genotipos con base en el rendimiento por unidad de superficie, la baja incidencia de la chicharrita (número de ninfas y adultos por planta), y la evaluación visual del daño en las plantas mediante escalas arbitrarias. Sin embargo, la evaluación visual de la resistencia no es confiable, ya que depende del criterio del investigador para ubicar cada genotipo en una u otra calificación, y no se sabe cómo afectan dichos genotipos a los estados biológicos del insecto y al potencial reproductivo de su población. Por lo anterior, en este estudio se evaluó los parámetros poblacionales de E. kraemeri en presencia de los cuatro genotipos de frijol ya indicados, contrastándolos con las respuestas ante un frijol susceptible a la plaga. MATERIALES Y MÉTODOS El estudio se llevó a cabo en el Campo Experimental Huichihuayán (CEHUICH) del Instituto Nacional de Investigaciones Forestales, Agrícolas y Pecuarias (INIFAP), en Huehuetlán, S.L.P, durante el ciclo otoño-invierno 1994-1995, con una temperatura media mensual de 24 oC y una humedad relativa de 65 a 90 %. El efecto de las lluvias se controló por medio de jaulas diseñadas para tal fin. Los parámetros poblacionales de E. kraemeri se estimaron mediante tablas de vida y fertilidad en los genotipos EMP-40(J-H)98, BAT-58-2, BAT-1636 y DOR-207; se utilizó la variedad Negro Jamapa At present, this insect is controlled by applying insecticide, which is the most practical and efficient shortterm way of control. These substances, however, have great disadvantages: intoxication of workers, increase of production costs, dying of beneficial insects, pollution of the environment, etc. (Schoonhoven,1985). There are other alternatives to control this pest, such as biological, cultural, and genetic control, using resistant cultivars (Davison and Lyon,1992). Considering the preceding and the fact that bean producers in the Huasteca Potosina are of limited economic resources, the use of resistant cultivars offers great perspectives for the E. kraemeri control in this region. The genotypes EMP-40(J-H)98, BAT-58-2, BAT1636 and DOR-207 are well adapted to the climatic conditions of the Huasteca Potosina and show little damage from the attack of the insect in this region. These genotypes are considered resistant to this pest, according to Rosales and de la Garza (1992)4. These authors selected the mentioned genotypes taking into account the yield per unit of area, the low incidence of the E. kraemeri (number of nymphs and adults per plant), and the visual evaluation of damage in plants by means of an arbitrary scale. Nevertheless, this method of visual evaluation of the resistance is not reliable, as it depends on the researcher’s criterion of grading each genotype, and it is ignored how these genotypes affect the biological stages of the insect and the reproductive potential of its population. For these reasons, the population parameters of E. kraemeri were evaluated in the mentioned genotypes in comparison with this pest parameters in a known susceptible bean genotype. MATERIALS AND METHODS This research was carried out in the Experimental Station of Huichihuayán (CEHUICH) of the Instituto Nacional de Investigaciones Forestales, Agrícolas y Pecuarias (INIFAP) in Huehuetlán, San Luis Potosí, during the autumn-winter period 1994-1995, at a monthly average temperature of 24 oC and a relative humidity of 65-90 %. The effect of rainfall was controlled by cages, designed for this purpose. The estimation of E. kraemeri population parameters was made through life and fertility tables in EMP-40(J-H)98, BAT-58-2, BAT1636 and DOR-207 genotypes; Negro Jamapa was used as susceptible control (Rosales and de la Garza, 1992)4. Some characteristics of the mentioned genotypes are: race Mesoamérica (Singh et al., 1992); growth habit Type II (Singh, 1982); black opaque seeds color and small size. The average weight of a 100 seeds is: DOR-207, 22.70 g; EMP-40(J-H)98, 27.97 g; BAT-1636, 24.73 g; BAT-58-2, 23.74 g, and Negro Jamapa, 23.30 g. In order to provide enough nymphs of the same age, necessary to carry out the study, an E. kraemeri colony was raised. For this purpose, adults were collected with a mouth sucking device on plants of the MAYA-HERNÁNDEZ ET AL.: PARÁMETROS POBLACIONALES DE Empoasca kraemeri como testigo susceptible (Rosales y de la Garza, 1992)4. Algunas características de los cinco genotipos son: raza Mesoamérica (Singh et al., 1991); hábito de crecimiento II (Singh, 1982); color y tamaño de semilla, negro opaco y pequeño. El peso promedio de 100 semillas es: DOR-207, 22.70 g; EMP-40(J-H)98, 27.97 g; BAT-1636, 24.73 g; BAT-58-2, 23.74 g y Negro Jamapa, 23.30 g. Para disponer de ninfas en la cantidad necesaria y de la misma edad, se procedió en un principio a mantener una cría de chicharritas, para lo cual se colectaron adultos con un aspirador de boca en plantas de frijol de la variedad Negro Jamapa, en una siembra previa realizada en campo. Los adultos colectados se colocaron en 150 plantas de frijol de 30 días de edad, aproximadamente, de la variedad Negro Jamapa, sembradas en macetas de plástico, las cuales tenían tres plantas por maceta. Las plantas se colocaron al aire libre en jaulas de 0.60 x 1.2 x 1.0 m de anchura, longitud y altura, respectivamente, con tela de mosquitero y techo de lámina para evitar la emigración de los adultos y proteger a los insectos de la lluvia. Para elaborar las tablas de vida se utilizó una cohorte de 100 ninfas de primer ínstar por genotipo. Las ninfas obtenidas de la cría se colocaron, con la ayuda de un pincel, sobre las hojas de 15 plantas de frijol de 30 días de edad, sembradas en macetas de plástico. Estas macetas se pusieron en jaulas (como las citadas) al aire libre. Dos ninfas de primer ínstar se colocaron en cada hoja, para que se alimentaran hasta alcanzar el estado adulto; las hojas utilizadas se escogieron de la parte media de la planta. Se numeraron las plantas en cada maceta, así como las hojas donde se colocaron las ninfas en cada planta, para facilitar el registro de la supervivencia y mortalidad de los especímenes en cada genotipo. Diariamente se registró el número de chicharritas sobrevivientes, hasta que los últimos adultos murieron. Las curvas de supervivencia se elaboraron con los datos de proporción de supervivencia (lx) de las tablas de vida de las chicharritas, mediante el programa de cómputo SUFERTI (Colunga y Vera, 1991). Para determinar las diferencias significativas entre las curvas de supervivencia de los genotipos se aplicó la Prueba de Z (Vera et al., 1997), mediante el citado programa SUFERTI. Los porcentajes de mortalidad se compararon con la prueba de Z aplicada a una distribución binomial (Infante y Zárate, 1997). Las tablas de fertilidad se elaboraron con las chicharritas que lograron llegar al estado adulto en cada genotipo. En cuanto las chicharritas realizaron la última muda para convertirse en adultos, éstos se colectaron con un aspirador de boca y se separaron las hembras y los machos en cada genotipo, con la ayuda de un microscopio de disección. Posteriormente se aislaron hembras y machos, en parejas, en pequeñas jaulas diseñadas para este propósito. Las jaulas se colocaron en el envés de las hojas para que los insectos se alimentaran y ovipositaran en ellas. Para elaborar las tablas de fertilidad, las hojas en las que ovipositaban las chicharritas se cortaban diariamente y se llevaban al laboratorio para efectuar el conteo de los huevecillos con la ayuda de un microscopio de disección. Cada jaula se cambiaba el mismo día a otra hoja con el objeto de que los adultos se alimentaran y las hembras continuaran la oviposición hasta su muerte. Durante la etapa de cría de E. kraemeri se observó que la relación sexual fue de 1:1 aproximadamente; por lo tanto, para calcular 605 Negro Jamapa cultivar, previously sown under field conditions. The collected adults were put on 150 approximately thirty-day-old bean plants of Negro Jamapa, which had been sown in plastic flowerpots, three plants in each. The plants were placed at open air in cages of 0.60x1.2x1.0 m (width, length and height, respectively), covered with mosquito net and laminar roofs to avoid the insects to migrate and protect them from the rain. In order to develope the life tables, a cohort of 100 first instar nymphs per genotype was used. The nymphs obtained from the colony were placed with a fine brush on the leaves of 15 thirty-day-old bean plants, sown in plastic flowerpots. These pots were put in cages outdoors (as described above). Two nymphs of the first instar were put on each leave to feed until reaching the stage of adult; the leaves were chosen from the middle part of the plant. The plants in each pot were numbered, as well as the leaves of each plant, on which the nymphs had been placed, in order to facilitate the survival and mortality registration of the specimens in each genotype. Every day, the surviving insects were counted until the last adults died. The survivorship curves were drawn, based on the data of survival proportion (lx) on the E. kraemeri life tables, using the SUFERTI computer program (Colunga and Vera, 1991). To find out if there were significant differences between the survivorship curves of the genotypes, the statistics analysis technique, named Z-test (Vera et al., 1997), was applied. This test was performed using the above mentioned SUFERTI program. The percentages of mortality were compared with the Z-test, applied to a binomial distribution (Infante and Zárate, 1997). The fertility tables were worked out with insects that reached the adult stage in each genotype. When the insects had their last molt to become adults, they were collected with a mouth sucking device in order to separate female and male in each genotype using a dissection microscope. Later on, female and male insects were isolated in pairs in small cages, designed for this purpose. The cages were placed on the underside of the leaves, allowing the insects to feed and oviposit on them. In order to elaborate the fertility tables, the leaves with eggs were cut daily, and the eggs were counted in the laboratory under a dissection microscope. The same day, each cage was changed to another leaf, so that the adults could feed on it and females could continue the oviposition until their death. In the colony of E. kraemeri it was observed that the distribution of sexes was approximately 1:1; so, in order to calculate survival rate l′x of the females and their fertility rate (mx), it was supposed af that 50 % of the nymphs from the initial cohorts would give rise to females, according to equations recommended by Vera et al. (1997). With the data, the following parameters were estimated: net reproductive rate (R0) also called rate of reproduction per generation; mean length of a generation (G) and innate capacity of increase (rm), also known as intrinsical rate of natural increase, rate of increase per capita or malthusian parameter (Krebs, 1985), using the SUFERTI program. The Test of Overlapping Intervals (Vera and Sotres, 1991) was applied to compare the innate capacity of increase of each cohort. This test simulates the theoretical growth of two or more populations 606 AGROCIENCIA VOLUMEN 34, NÚMERO 5, SEPTIEMBRE-OCTUBRE 2000 af la proporción de supervivencia de las hembras l′x y su fertilidad (mx), se supuso que 50 % de las ninfas de las cohortes iniciales darían origen a hembras, de acuerdo con las ecuaciones recomendadas por Vera et al. (1997). Así se estimaron los parámetros: tasa neta de reproducción (R0) llamada también tasa de reproducción por generación, tiempo medio de generación (G) y capacidad innata de incremento (rm) conocida también como tasa intrínseca de incremento natural, tasa de incremento per cápita o parámetro maltusiano (Krebs, 1985), utilizando el programa SUFERTI. Con la finalidad de comparar las capacidades innatas de incremento de cada cohorte, se aplicó la Prueba de Traslapo de Intervalos (Vera y Sotres, 1991), que simula el crecimiento teórico de dos o más poblaciones sometidas a dos o más tratamientos (genotipos), bajo el modelo estocástico E(nt)= n0 exp (rmt), y sus respectivos intervalos de confianza para cualquier momento “t”. En este caso se consideró que si los intervalos se traslapaban después de 90 días (t=90), entonces las rm’s a comparar eran estadísticamente iguales. Este criterio se tomó con base en que el periodo crítico del frijol al ataque de la chicharrita es cuando las plantas tienen hasta 90 días de edad. Para esta prueba también se utilizó el programa SUFERTI. RESULTADOS Y DISCUSIÓN Parámetros de supervivencia Respecto a la proporción de supervivencia y longevidad total de E. kraemeri en los cinco genotipos (Figura 1), la prueba de Z detectó diferencias significativas (p≤0.05) entre los 5 y 30 días de edad en las cohortes de chicharritas desarrolladas en Negro Jamapa versus exposed to two or more treatments (genotypes) under the stochastic model E(nt)=n0 exp (rmt), and its respective intervals of reliability for any “t” momentum. In this case, it was considered that rm’s to be compared were statistically equal, if the intervals overlapped after 90 days (t=90). This criterion was based on the fact that bean plants are susceptible to E. kraemeri attack until they reach 90 days old. The SUFERTI program was used for this test, too. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION Survival parameters The survival rate and the total longevity of E. kraemeri in the five genotypes can be observed in Figure 1. The Ztest detected significant differences (p=0.05) between 5 and 30 days of age in the insect cohorts, developed in Negro Jamapa, in contrast to BAT-1636, EMP-40(J-H)98, and DOR-207, as well as between this last one and the others; there were no differences between BAT-1636 and EMP-40(J-H)98. Table 1 shows that the mean expectation of life of this Cicadellid was less in the first eight days of life in all genotypes, as compared to Negro Jamapa. That is, during almost all the lifetime of the nymphs. The difference was greater in DOR-207 and minor in BAT-58-2. From the ninth day onward, there was no clear difference between the values of this parameter. This is not unusual, Camargo et al. (1997), Sánchez et al. (1997), and Vera and Domínguez (1997) observed the same phenomenon in immature stages of beanweevils (Acanthoscelides 1 0.9 DOR-207 a 0.8 EMP-40(J-H)98 b Supervivencia (1x ) BAT-1636 b 0.7 BAT-58-2 c 0.6 N. Jamapa c 0.5 0.4 0.3 0.2 0.1 0 0 10 20 30 40 50 Edad en días Figura 1. Curvas de supervivencia de Empoasca kraemeri Ross & Moore en cinco genotipos de frijol Phaseolus vulgaris L. Genotipos con letras iguales no presentan diferencias significativas (Z, 0.05). Figure 1. Curves of survival of Empoasca kraemeri Ross & Moore in five genotypes of Phaseolus vulgaris L. Genotype with the same letter are not significantly different (Z, 0.05). MAYA-HERNÁNDEZ ET AL.: PARÁMETROS POBLACIONALES DE Empoasca kraemeri BAT-1636, EMP-40 (J-H)98 y DOR-207, así como entre esta última y todas las demás; no hubo diferencias entre BAT-1636 y EMP-40(J-H)98. En el Cuadro 1 se observa que en comparación con el testigo, la esperanza media de vida del cicadélido fue menor en los primeros ocho días de su vida en todos los genotipos, es decir, durante casi todo el lapso de existencia de las ninfas, la diferencia fue mayor en DOR-207 y menor en BAT-58-2; desde el día nueve en adelante no hubo diferencias claras en los valores de este parámetro. Esto no es extraño, pues Camargo et al. (1997), Sánchez et al. (1997) y Vera y Domínguez (1997) observaron el mismo fenómeno en estados inmaduros de gorgojos (Acanthoscelides obtectus y Zabrotes subfasciatus) desarrollados en variedades o líneas de frijol resistentes a estos brúquidos. En el Cuadro 2 se observa que la mortalidad acumulada del estado ninfal del insecto fue mayor (p< 0.01) en DOR-207 y menor en BAT-58-2 y Negro Jamapa, lo cual indica que existen mecanismos de defensa en los genotipos DOR-207, EMP-40(J-H)98 y BAT-1636 que inciden en el desarrollo ninfal de la chicharrita. Norris y Kogan (1991) indican que hay defensas de tipo morfológico en las hojas de las plantas debido a la presencia de tricomas que impiden la alimentación adecuada de los insectos o que producen heridas en el cuerpo de las ninfas que ocasionan mortalidad. Probablemente las defensas de esos tres genotipos se deban a este tipo de resistencia morfológica, pero esto se tendría que confirmar con estudios diseñados específicamente para tal fin. En el Cuadro 3, donde se presenta el tiempo que vivieron los insectos en estados de ninfa y adulto, así como el inicio de la oviposición, se observa una diferencia de tres días en el desarrollo ninfal y de adultos entre Negro Jamapa y DOR-207, así como de un día entre el testigo en relación con EMP-40(J-H)98 y BAT-1636. Como el lapso total de vida fue de 44 a 50 días sería difícil afirmar que esta diferencia se deba al efecto de los genotipos en Cuadro 1. Esperanza media de vida (ex) de Empoasca kraemeri Ross & Moore en cinco genotipos de frijol. Table 1. The mean expectation of life (ex) of Empoasca kraemeri Ross & Moore in five bean genotypes. Genotipos X (días) DOR-207 0 5 8 10 15 20 25 30 12.93 15.20 15.60 19.04 18.50 15.46 11.63 7.90 EMP-40 (J-H)98 BAT-1636 18.71 19.90 20.99 21.29 18.23 15.43 13.13 9.44 20.90 20.23 21.12 22.29 18.78 16.05 13.48 10.07 BAT-58-2 24.83 21.75 22.05 21.17 19.07 14.60 10.89 7.61 Negro Jamapa 27.04 23.33 22.59 22.20 19.10 15.32 11.78 7.83 607 obtectus and Zabrotes subfasciatus), growing on resistant bean cultivars or lines. Table 2 presents the accumulated mortality of the nymphal stage of the insect, being statistically greater (p< 0.01) in DOR-207 and minor in BAT-58-2 and Negro Jamapa. This nymph mortality indicates that there are defense mechanisms in genotypes DOR-207, EMP-40(JH)98, and BAT-1636, which definitely affect the development of E. kraemeri nymphs. Norris and Kogan (1991) pointed out that morphological type defenses exist in the leaves of the plant, due to the presence of trichomes, that hinder adequate feeding, or produce injuries in the nymph’s body, causing mortality. The defenses of the three genotypes mentioned could be due to this type of morphological resistance, but this should be proved by specifically designed studies. Table 3 presents the time the insects lived as nymphs and adults, as well as the beginning of the oviposition. There is a difference of three days for the development of nymphs and adults between Negro Jamapa and DOR206, and of one day, between this control and EMP-40(JH)98 and BAT-1636. Taking into account the total span of life (44-50 days), it would be difficult to affirm that this difference is due to the effect of the genotypes during the time of development of both insect stages. Nevertheless, as will be seen ahead, the age of E. kraemeri at the beginning of the oviposition (with differences up to five days) had an impact on fertility parameters. Fertility parameters Based on the data of Table 4, and to emphasize the importance of the relation between R0 and G, it might be said that an E. kraemeri population may increase 5.08 times in 29.27 days in DOR-207, and 20.27 times in 24:84 days in Negro Jamapa. This means, the increment of the insect in this control will be about four times greater, in less time (approximately five days) than in the first genotype. This example shows how the age of E. kraemeri Cuadro 2. Porcentaje de mortalidad de ninfas de chicharrita Empoasca kraemeri Ross & Moore en cinco genotipos de frijol. Table 2. Percentage of mortality of Emposca kraemeri Ross & Moore nymphs on five bean genotypes. Genotipo DOR-207 EMP-40(J-H)98 BAT-1636 BAT-58-2 Negro Jamapa Mortalidad de ninfas (%) 70 a 47 b 40 b 21 c 14 c Genotipos con la misma letra no son estadísticamente diferentes (p<0.01). 608 AGROCIENCIA VOLUMEN 34, NÚMERO 5, SEPTIEMBRE-OCTUBRE 2000 Cuadro 3. Lapso de vida de ninfas, adultos e inicio de oviposición de Empoasca kraemeri Ross & Moore en cinco genotipos de frijol. Table 3. Span of life of nymphs and adults, and beginning of oviposition of Empoasca kraemeri Ross & Moore in five bean genotypes. Tiempo (días) Inicio de oviposición Genotipo DOR-207 EMP-40(J-H)98 BAT-1636 BAT-58-2 Negro Jamapa Ninfa Adulto Total 11.0† 9.0† 9.0† 8.0† 8.0† 39.0 39.0 38.0 36.0 36.0 50 48 47 44 44 21 18 18 16 16 † Significa que a partir de ese momento al menos 50 % los insectos pasaban de ninfas al estado adulto. el tiempo de desarrollo de ambos estados del insecto. Sin embargo, como se consigna más adelante, la edad que tenían las chicharritas cuando se inició la oviposición (con diferencias de hasta cinco días), tuvo repercusiones en los parámetros de fertilidad. Parámetros de fertilidad Con base en la información del Cuadro 4 y para enfatizar la importancia de la relación entre R0 y G, la población de E. kraemeri se incrementaría 5.08 veces en 29.27 días en DOR-207, y 20.27 veces en 24.84 días en Negro Jamapa; es decir, el incremento del insecto en el genotipo susceptible será aproximadamente cuatro veces mayor en un tiempo menor (aproximadamente cinco días) que en el genotipo resistente. Con este ejemplo se aprecia cómo la edad que tenían las chicharritas cuando iniciaron la oviposición, afectó directamente a estos dos parámetros; en otras palabras, las hembras se reprodujeron primero en Negro Jamapa (y obviamente pusieron mayor número de huevecillos durante su vida) que en DOR207, como se señala en el Cuadro 3, lo cual se reflejó en el tiempo medio de generación, que a su vez repercute en la capacidad innata de incremento, cuya ecuación general es rm = ln (R0) / G. Cabe mencionar que la comparación estadística de las tasas netas de reproducción no se puede hacer directamente porque dependen del tiempo de generación, y éste no fue igual para todas las cohortes. Las tasas que se pueden comparar son las rm’s (que se derivan de R0) debido a que están en las mismas unidades (individuos/día). Al respecto, la prueba de Traslapo de Intervalos detectó diferencias significativas (p<0.15) entre las rm’s de E. kraemeri procedentes de todos los genotipos con la rm en el testigo. Asimismo, la prueba detectó diferencias entre las rm’s del insecto en DOR-207 versus EMP-40(J-H)98, BAT-1636 y BAT-582. No hubo diferencias entre EMP-40(J-H)98 y initiating oviposition, directly affected these two parameters. In other words, the females reproduced first on Negro Jamapa (obviously laying a larger number of eggs during their lives) than in DOR-207, as Table 3 indicates. This is expressed in the mean length of a generation, which influences the innate capacity of increase, whose general equation is rm = ln (R0) / G. The statistical comparison of the net reproduction rates cannot be made directly because they depend on the time of generation, and this was not the same for all the cohorts; the rates which can be compared are the rm’s (derived from R0) as they are in the same units (insect/day). The Test of Overlapping Intervals detected significant differences (p<0.15) between the rm’s of E. kraemeri coming from all genotypes, and the rm in the control. Likewise, the test detected differences between the rm’s of the insect on DOR-207 versus EMP-40(J-H)98, BAT1636 and BAT-58-2. There were no differences between EMP-40(J-H)98 and BAT-1636 (Table 4). Marking these differences: theoretically, the E. kraemeri population will increase 5.55 % in DOR-207 in one day, and 12:11 % on the susceptible control. According to these results, the DOR-207 genotype caused the greatest damage in the E. kraemeri population, mainly in the nymph mortality, mean expectation of life, and survival and reproduction rates. Likewise, the genotypes EMP-40(J-H)98 and BAT-1636 affected the same population parameters of this Cicadellid, but less than DOR-207. The genotype BAT-58-2 affected the E. kraemeri population mainly in its reproduction rate (rm). However, the difference with respect to the control, although statistically minor, is minimum (Table 4); therefore, it might not be recommended as resistant. Based on these results, the damage visual evaluation method used by Rosales and de la Garza (1992)4 is good as a first step for the selection of resistant genotypes to E. kraemeri. On the other hand, the demographic technique Cuadro 4. Tasa neta de reproducción (R0), capacidad innata de incremento (rm) y tiempo medio de generación (G) de Empoasca kraemeri Ross & Moore en cinco genotipos de frijol. Table 4. Net reproductive rate (R0), innate capacity of increase (rm) and mean length of a generation (G) of Empoasca kraemeri Ross & Moore on five bean genotypes. Genotipo DOR-207 EMP-40(J-H)98 BAT-1636 BAT-58-2 Negro Jamapa R0 5.08 9.73 11.24 15.00 20.27 rm 0.0555 0.0843 0.0903 0.1087 0.1211 G a b b c d 29.27 26.99 26.80 24.92 24.84 Genotipos con la misma letra no son estadísticamente diferentes (p<0.15). MAYA-HERNÁNDEZ ET AL.: PARÁMETROS POBLACIONALES DE Empoasca kraemeri BAT-1636 (Cuadro 4). Así, ejemplificando para remarcar estas diferencias, teóricamente la población de la chicharrita se incrementaría 5.55 % en DOR-207 en el transcurso de un día y 12.11 % en el testigo susceptible. En resumen, el genotipo DOR-207 fue el que más detrimento causó en la población de E. kraemeri, principalmente en la mortalidad de ninfas, esperanza media de vida y tasas de supervivencia y reproducción. Asimismo, los genotipos EMP-40(J-H)98 y BAT-1636 afectaron los mismos parámetros poblacionales del cicadélido, pero en menor grado que DOR-207. El genotipo BAT-58-2 afectó principalmente la población de E. kraemeri en su tasa de reproducción rm; sin embargo, la diferencia con el testigo, aunque estadísticamente menor, fue mínima (Cuadro 4), por lo que se sugiere tomar las reservas del caso para recomendarla como resistente. A la luz de estos resultados, se reconoce que el método de evaluación visual de daño aplicado por Rosales y de la Garza (1992)4 es bueno como un primer tamiz para seleccionar genotipos resistentes a E. kraemeri. Por otro lado, la técnica demográfica utilizada en este trabajo permite identificar a los genotipos que mayor detrimento causan a la población de la chicharrita, con lo cual puede predecir los que pueden tener mayor posibilidad de comportarse como resistentes por mayor tiempo en condiciones de campo. Por lo anterior, se considera que ambos métodos son complementarios. Además, con los valores de las rm’s se pueden formular modelos matemáticos que pronostiquen el crecimiento poblacional de E. kraemeri en cada genotipo para planificar medidas de control que eviten que la población del insecto sobrepase algún umbral preestablecido. CONCLUSIONES Se detectaron diferencias estadísticas en el efecto de los genotipos DOR-207, EMP-40 (J-H) 98, BAT-1636 y BAT- 58-2, clasificados como resistentes a E. kraemeri en condiciones de campo, para algunos parámetros poblacionales del insecto. Se determinó que los tres primeros genotipos causaron menor esperanza media de vida de las ninfas y mayor mortalidad de éstas, así como menores tasas de supervivencia y reproducción; mientras que el genotipo BAT-58-2 causó un efecto menor, pero significativo, principalmente en las tasas de reproducción. LITERATURA CITADA Andrews, K. L. y J. R. Quezada. 1989. Manejo Integrado de Plagas Insectiles en la Agricultura: Estado Actual y Futuro. Escuela Agrícola Panamericana. El Zamorano, Honduras. 623 p. Camargo L., M. F., J. Vera G. y B. Domínguez R. 1997. Preferencia, mortalidad y fertilidad de Acanthoscelides obtectus (Say) en seis líneas de frijol y la variedad Jamapa. Agrociencia 31: 253-247. 609 used in this research allows to identify those genotypes which cause a major damage to the Cicadellid population, and at the same time predicts which genotypes have more possibilities to behave as resistant for a longer period of time under field conditions. For the above reasons both procedures can be considered as complementary methods. In addition, based on the values of the rm’s, mathematical models can be formulated to predict the increase of E. kraemeri population in each genotype, in order to plan measures of control to avoid that the insect population surpasses a preestablished threshold. CONCLUSIONS It was possible to differentiate statistically the effects of the initially classified as resistant genotypes under field conditions DOR-207, EMP-40(J-H)98, BAT-1636, BAT-58-2 on certain population parameters of E. kraemeri. It was determined, that these first three genotypes caused a lower mean expectation of life and a greater nymphal mortality, as well as minor rates of survival and reproduction, while genotype BAT-58-2 mainly caused a minor but significant effect on the reproduction rates. —End of the English version— pppvPPP Carrillo R., H. y A. Rodríguez. 1982. Combate de las plagas del frijol en suelos mecanizables de Quintana Roo. Folleto para Productores No. 7. SARH. INIA. Campo Experimental Chetumal. México. 9 p. Colunga G., M. y J. Vera G. 1991. SUFERTI: Programa de computación para estimar y comparar algunas estadísticas demográficas en insectos. Resúmenes XXVI Congreso Nacional de Entomología. Sociedad Mexicana de Entomología. Oaxaca, Oax., México. pp: 137-138. Davison, R. H. y W. F. Lyon. 1992. Plagas de Insectos Agrícolas y del Jardín. Limusa. México, D. F. pp: 340-341. Infante G., S. y G. Zárate de L. 1997. Métodos Estadísticos. Un Enfoque Interdisciplinario. 4a reimpresión. Trillas. pp: 304-307. King, A. B. S. y J. L. Saunders. 1984. Plagas invertebradas de cultivos anuales alimenticios en América Central. Tropical Development and Research Institute. Overseas Development Administration, London, England. Centro Agronómico de Investigación y Enseñanza. Turrialba, Costa Rica. pp: 120-121. Krebs, C. J. 1985. Ecology. The Experimental Analysis of Distribution and Abundance. 3rd ed. Harper Int. New York, San Francisco, London. 754 p. Norris, D. M. y M. Kogan. 1991. Bases bioquímicas y morfológicas de la resistencia. In: Mejoramiento de Plantas Resistentes a Insectos. Maxwell, F. G. y P. R. Jennings (eds.). Limusa. México. pp: 48-82. Sánchez R., A., B. Domínguez R. y J. Vera G. 1997. Resistencia de tres líneas de frijol al ataque de Zabrotes subfasciatus (Boheman). Agrociencia 31: 209-215. Schoonhoven, A. Van. 1985. Frijol. Investigación y Producción del Programa de las Naciones Unidas para el Desarrollo (PNUD). CIAT. Cali, Colombia. 236 p. 610 AGROCIENCIA VOLUMEN 34, NÚMERO 5, SEPTIEMBRE-OCTUBRE 2000 Singh, S. P., P. Gepts, and D. Debouck. 1991. Races of common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris, Fabaceae). Econ. Bot. 45: 379-396. Singh, S. P. 1982. A key for identification of different growth habits of Phaseolus vulgaris L. Annu. Rep. Bean Improv. Coop. 25: 92-94. Vera G., J. y D. Sotres R. 1991. Prueba de Traslapo de Intervalos para comparar tasas instantáneas de desarrollo poblacional. Agrociencia. Serie de Protección Vegetal 2(2): 7-13. Vera G., J., V. M. Pinto y J. López C. 1997. Ecología de Poblaciones de Insectos. Universidad Autónoma Chapingo. 135 p. Vera G., J. y B. Domínguez R. 1997. Resistencia de variedades de frijol al ataque del gorgojo pinto Zabrotes subfasciatus (Boheman) y del gorgojo común Acanthoscelides obtectus (Say) (Coleoptera : Bruchidae). Agrociencia 31: 353-357.