Adapting the Sheltered Instruction Observation Protocol

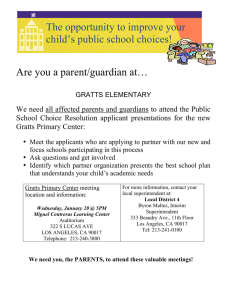

Anuncio