PHILIP II AND THE ORIGINS OF BAROQUE THEATRE1 This was

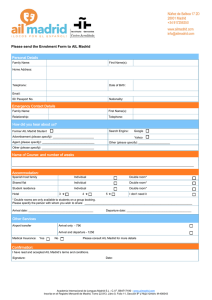

Anuncio