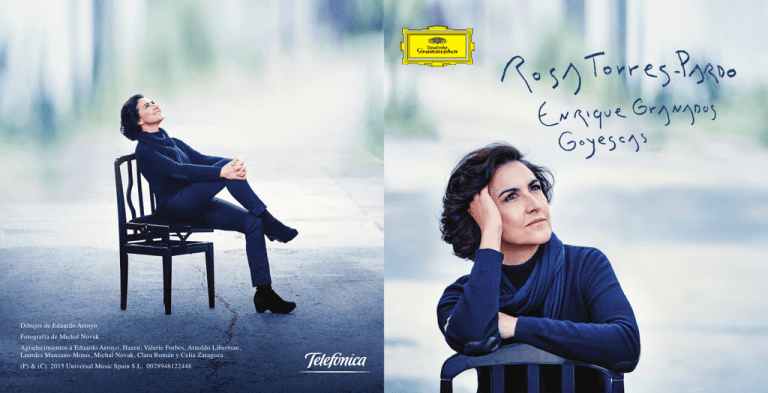

Dibujos de Eduardo Arroyo Fotografía de Michal Novak

Anuncio

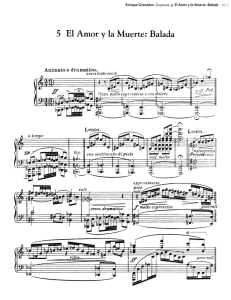

Dibujos de Eduardo Arroyo Fotografía de Michal Novak Agradecimientos a Eduardo Arroyo, Hazen, Valerie Forbes, Arnoldo Liberman, Lourdes Manzano-Monís, Michal Novak, Clara Román y Celia Zaragoza. (P) & (C) 2015 Universal Music Spain S.L. 0028948122448 HIGH-SPIRITED VARIATIONS IN PIANO MAJOR VARIACIONES LÚDICAS EN PIANO MAYOR “Goyescas is a timeless work. Of that I am convinced.” “Goyescas es una obra para siempre. En este punto estoy convencido.” (Enrique Granados) (Enrique Granados) It is true that Goyescas is not a familiar concert-hall favorite, and even music lovers are seldom acquainted with its staves. Perhaps this is the result of a superficial, rash judgment, or a bland, preconceived notion, that has managed to surround this remarkable work with a simplistic and negative silence, or what may be even worse, a complete unawareness of how this exceptional music, our very own, should be played and heard. Because, of course, the motives in Goyescas are entwined, but many times it is precisely such interweaving that seems more authentic, as opposed to a linear, “one-way” scheme. Moreover, here we are presented with a successful attempt to reflect those complex paths in all their dynamic bounty and labyrinthine sinuosity, with all their inclemencies and expressive difficulties. Rosa Torres-Pardo draws this musical picture with a clarity and brilliance that enables her to extract maximum conceptual richness and lyrical depth from every bar. Goyescas is endowed with a virtuosic artistry that evokes inner emotional turmoil, unrestrained authenticity and folk-music tradition. Como es bien sabido, Goyescas no es invitada habitual de los conciertos ni pentagrama transitado en la audición de los melómanos. Quizá una mirada superficial, un apresuramiento en el juicio, algún tópico enquistado, ha hecho de esta notable obra un largo silencio simplista o negador, o, lo que es peor aún, una cabal ignorancia sobre la manera en que una música excepcional y nuestra debe ser interpretada y oída. Claro que en Goyescas los caminos son enredados, pero justamente muchas veces los caminos enredados son los auténticos, porque se trata de una complejísima maraña -no de un one-way esquemático-, y más aún, de un intento logrado de reflejar esa complejísima maraña en su riqueza dinámica, en sus laberintos fecundos, en sus dificultades siempre inclementes y expresivas. Rosa Torres-Pardo dibuja en esta historia la experiencia de la luz, la rigurosa lucidez que le permite arrancar (el verbo me parece justo) a cada pentagrama el máximo posible de riqueza conceptual y lirismo profundo. Porque Goyescas es, siempre en el sendero de una musicalidad sorprendente, esa excepcional mezcla de interiorizada turbación emocional y prueba virtuosística ejemplar, de conmoción íntima, veracidad comunicativa y énfasis popular. In 1915, Granados wrote: “Some sixteen years ago, I drafted a project which turned out to be unsuccessful. At the time, its failure, though doubtless understandable, affected me deeply. In its entirety, there were obvious defects, but I was convinced that certain passages were worth preserving. In 1909, I made another try, giving it the form of a suite for piano. My idea was that the inspiration for the music should lie in Spain itself, in the abstract sense, and as a projection of certain elements of my country’s character and way of life. At the same time, I had very much in mind the representative figures and scenes portrayed by Goya”. It is clear that the composer had a distinct idea of his goals, but perhaps we might add that Spain and Goya as generators of this music are an accurate choice – it is to be moved, that is to say, to Escribe el autor en 1915: “Hace unos diecisiete años esbocé sin éxito un proyecto. Entonces, indudablemente, mereció el fracaso; sin embargo, me afectó muchísimo lo ocurrido. En una total estimación había defectos evidentes, pero estaba convencido del valor de ciertos momentos, que conservé cuidadosamente. En 1909 volví sobre ello de nuevo, dándoles la forma de una suite para piano. La idea que tuve presente como generadora de esta música era España, en el sentido abstracto e ideación de determinados elementos del carácter y la vida de mi país. Coincidiendo con ello, tenía muy en cuenta los tipos y las escenas tratados por Goya”. Es evidente que el compositor tenía clara consciencia de sus objetivos, pero quizá podríamos agregar que España y Goya como generadores de esta música es un diagnóstico certero, es move with the strength and nostalgia of a people who always knew how to sing, it is to place the source of inspiration in a country with a profuse phantasmal imagery and a huge romantic beating which found the painter from Saragossa one of its most lucid interpreters. The polyphonic texture in Goyescas is one of the highest musical expressions from an artist who felt extraordinarily free and creative. He possessed an acutely dramatic sense and subtle impressionistic style which holds sway over the dictates of his inner psyche. Granados –who liked to be called an artist, as Wagner did- developed in this timeless work all that his skill and memory were capable of depicting. From local and regional dance tunes, and the popular songs of Madrid, to the impressive sequence in El amor y la muerte (Love and Death), where the metaphysical is transmitted through a trembling pathos and becomes, in the final movement – Serenata del espectro (The ghost’s serenata) – a Spanish guitar. From the magnificent tree of love in La maja y el ruiseñor (The maiden and the nightingale) to the particularly vivid expression of a “transcendental flirtation”. From this unquestionable embodiment of an outstanding and demanding pianist, expert in what an eloquent execution can do (he was the first to perform in Madrid Chopin’s Piano Concert in F Minor), to the numerous and splendidly subtle shadings that grace this work with an exquisite stylistic refinement. This is Granados at his best; his most remarkable, most dramatic, most discerning and most enlightened best. And he is the passionate and ductile witness of what Pedro Elías calls “the elegant Madrid of the Goyesque characters”. This is not an appropriate moment to compare this culminating point in the work of Granados with Albeniz’s Iberia, both expressions of the most elevated Spanish musical art for the piano. But it is important to note that both helped introduce to the world of culture the native richness and expressive greatness of their country’s indigenous musical heritage. Both represent a challenge for those who put to the test the real ability and exalted imagery of unique artists who have embraced, in an exceptional way, Leon Tolstoy’s maxim: “If you want to become universal, speak of your village”. conmoverse, es decir, moverse con la fuerza y la nostalgia de un pueblo que siempre supo cantar, es instalar la fuente de inspiración en un país poblado de una fantasmática profusa y de un latido romántico inmenso, que tuvo en el pintor aragonés uno de sus más lúcidos intérpretes. El piano polifónico de Goyescas es una de las expresiones musicales más altas de un artista que se sentía extraordinariamente libre y creativo, que poseía la capacidad dramática y la sutil singularidad de una inteligencia impresionista, que dominaba un visceral evangelio: el de la conmoción auténtica. Granados -que gustaba se le llamara artista, como Wagner- desarrolló en esta obra imperecedera todo lo que su maestría era capaz de dibujar y su memoria capaz de elaborar. Desde las tonadillas madrileñas, las escenas costumbristas, las canciones populares, hasta esa sobrecogedora secuencia de El amor y la muerte (donde el latido metafísico tiene un sonido de musicalidad patética y estremecida, que se transforma en la escena final –Serenata del espectro- en una guitarra española); desde ese magnífico árbol del amor de La maja y el ruiseñor hasta las pinceladas drásticamente pictóricas de un “requiebro trascendente”; desde su indudable perfil de pianista notable y exigente, conocedor de las posibilidades de un teclado elocuente (fue él quién estrenó en Madrid el Concierto para piano y orquesta en Fa menor de F. Chopin) hasta las instancias esplendorosas que matizan frecuentes momentos de esta obra, de un notable refinamiento estilístico; todo es el mejor Granados, el más notable, el más dramaturgo, el más perspicaz, el más iluminado. Y el apasionado y dúctil testigo de lo que Pedro Elías llama “el Madrid elegante de la majería Goyesca”. No es el momento de establecer prescindibles comparaciones entre este momento y ese otro que lleva el nombre de Iberia de Albéniz –ambos expresión de la alta literatura pianística española– pero es necesario señalar que entre uno y otro logran instalar en el mundo de la cultura un ceremonial pleno de riqueza autóctona y de grandeza expresiva. Ambos, a la vez, desafío de aquellos que ponen a prueba la capacidad real y la imaginería exaltada de artistas inigualables. Ambos, por fin, haciendo suyos de manera excepcional aquel lúcido pensamiento del viejo L. Tolstoy: “Si quieres ser universal, habla de tu aldea”. El esplendor, el drama y la majestad de Goyescas nacieron de esta lucidez última. The splendor, drama and majesty of Goyescas arise from just such an understanding. Granados captures in these bars the nature of both our intimate and group history; the solitary and the gregarious. It is an expressive microcosm of an identity (as I am sure the essayist Celia Amorós would have put it), where the composer’s explorations are connectedly put together through passages such as El fandango de candil (Fandango under the oil-lamp) which blends the local color and rhythmical suggestions ranging from the baroque to the Hispanic ballad. And through the opening bars of Los requiebros (Flirtations), of complex execution, immediately followed by El coloquio de la reja (Conversation by the window), where a three-note sequence suggests intense emotional pain, giving way to an unexpectedly radiant arpeggio. And so on, until the Epilogue, where the evocation of a Spanish guitar returns to provide the finishing flourish to a musical mural whose purest essence flows from the heart. Enrique Granados draws the lines of a creative and unique work which captivates us as if we were prisoners in a dream become a reality that we need to live, here and now, in its high-spirited presence. Let us be carried away by this enchantment, by this metaphysical fever, by these paths of sensual sonority. Arnoldo Liberman Beauty? Music? Silence? ... the piano always comes from somewhere else, from another garden, from another time that lives in the memory of a fountain. Luis García Montero Porque Granados capta en estos pentagramas nuestra íntima historia y nuestra historia grupal, la soledosa y la gregaria. Microcosmos expresivo de una identidad (así lo hubiera llamado, seguramente, la ensayista Celia Amorós), el autor desarrolla sus búsquedas desde una tensión siempre vertebral; desde escenas que, como en El Fandango de candil, incluyen en su estructura desde la pincelada costumbrista hasta la sugestión rítmica; desde el barroquismo original hasta la fuerza arrebatada y la elegancia preciosista de una balada hispánica; desde Los requiebros (acta inicial de complicada ejecución: “¡Anda, chiquilla! Dale con gracia, que me robas el alma”) hasta El coloquio en la reja, inmediata contigüidad de la más pura cepa schumaniana, donde el requiebro –célula de tres notas en el registro medio agudo- se hace recitativo dolido y sentido y arpegio inesperadamente refulgente; y así, sucesivamente, hasta el Epílogo, donde la guitarra española regresa por sus fueros rubricando una pintura mural de musicalidad excelsa, todo ello, pentagramas de la más pura esencia y demasía del corazón. Estamos, pues, ante una grabación en la que Enrique Granados traza las líneas de un pentagrama inédito, en un mensaje último que, como toda obra tercamente creadora, más nos atrapa cuanto más tratamos de atraparla, quizás prisioneros de un sueño hecho realidad que necesitamos vivir, hoy y aquí, en su más jubilosa presencia. Abandonemos por un momento la sensatez ingrávida y dejémonos llevar por este encantamiento, por esta temperatura metafísica itinerario de una ilusión, de una emoción única. Arnoldo Liberman Dibujos: ¿La belleza? ¿La música? ¿El silencio? … el piano siempre llega de otro lugar, de otro jardín, de un tiempo que vive en la memoria de una fuente. Luis García Montero