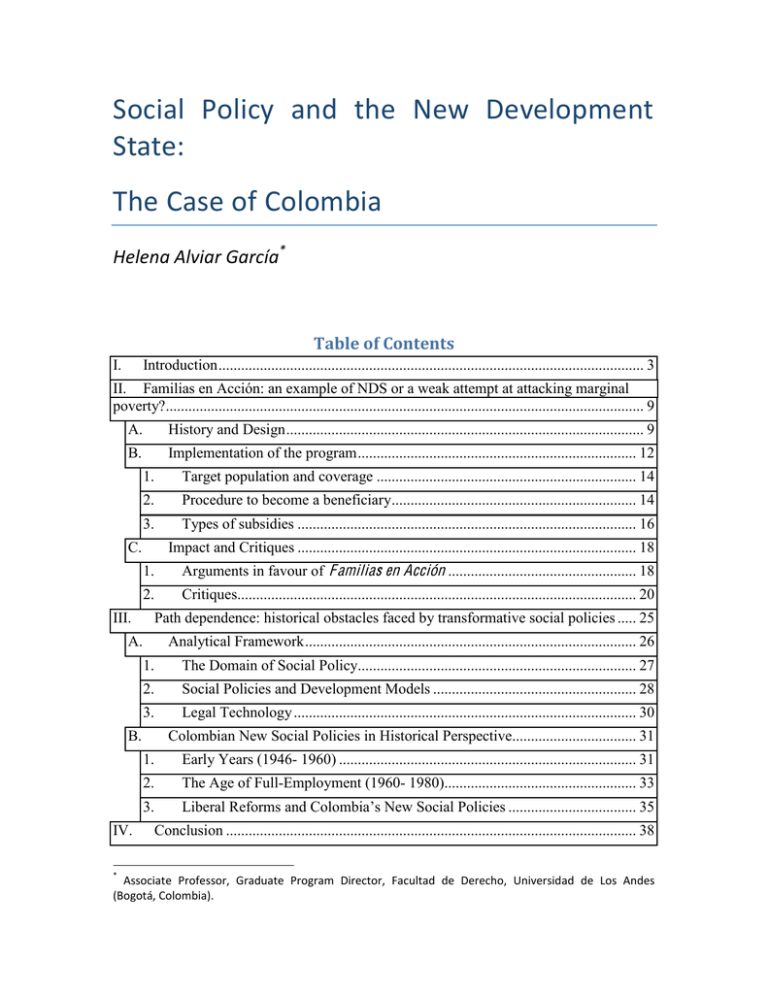

Social Policy and the New Development State

Anuncio