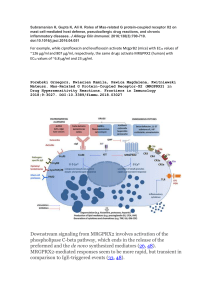

Journal of Counseling Psychology 2013, Vol. 60, No. 4, 557–568 © 2013 American Psychological Association 0022-0167/13/$12.00 DOI: 10.1037/a0033446 This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers. This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly. Social Cognitive Model of Career Self-Management: Toward a Unifying View of Adaptive Career Behavior Across the Life Span Robert W. Lent Steven D. Brown University of Maryland Loyola University Chicago Social cognitive career theory (SCCT) currently consists of 4 overlapping, segmental models aimed at understanding educational and occupational interest development, choice-making, performance and persistence, and satisfaction/well-being. To this point, the theory has emphasized content aspects of career behavior, for instance, prediction of the types of activities, school subjects, or career fields that form the basis for people’s educational/vocational interests and choice paths. However, SCCT may also lend itself to study of many process aspects of career behavior, including such issues as how people manage normative tasks and cope with the myriad challenges involved in career preparation, entry, adjustment, and change, regardless of the specific educational and occupational fields they inhabit. Such a process focus can augment and considerably expand the range of the dependent variables for which SCCT was initially designed. Building on SCCT’s existing models, we present a social cognitive model of career self-management and offer examples of the adaptive, process behaviors to which it can be applied (e.g., career decision making/exploration, job searching, career advancement, negotiation of work transitions and multiple roles). Keywords: social cognitive career theory, self-efficacy, outcome expectations, goals, adaptive behavior racially diverse students (Byars-Winston, Estrada, Howard, Davis, & Zalapa, 2010), gay and lesbian workers (Morrow, Gore, & Campbell, 1996), and persons with disabilities (Fabian, 2000); and to consider the theory’s implications for practice (e.g., Brown & Lent, 1996; Lent, 2013b; Lent & Fouad, 2011). A fourth SCCT model, aimed at satisfaction/well-being in educational and vocational contexts, has also been introduced (Lent & Brown, 2006, 2008). To this point, the three original models have attracted a good deal of research attention (see, e.g., Betz, 2008; Brown et al., 2008; Lent, 2013b; Lent & Sheu, 2010; Sheu et al., 2010). The newer model of well-being has also begun to stimulate inquiry, both in the United States and abroad (e.g., Lent, Taveira, & Lobo, 2012; Ojeda, Flores, & Navarro, 2011). Despite this healthy level of inquiry and application, we see several areas that are ripe for theory extension. In particular, as it is currently constituted, SCCT is primarily designed to address a focused but important set of content questions, such as predicting the types of educational and vocational activity domains toward which people will gravitate and in which they will find satisfaction and relative success. Like most other theories of career development, the focus has, metaphorically speaking, been more on the destination than on the journey, that is, on where people end up, occupationwise, rather than on how they get there or how they manage new challenges once they arrive. One way to extend SCCT’s comprehensiveness, then, would be to add more of an explicit focus on the myriad process aspects of career development, addressing the dynamic ways in which people adapt to both routine career tasks and unusual career challenges, both within and across educational/vocational fields. This process dimension is primarily concerned with such questions as how, under varying environmental conditions, people make career-related decisions, negotiate the transition from school to work, find jobs, pursue When it was initially presented nearly 20 years ago, social cognitive career theory (SCCT; Lent, Brown, & Hackett, 1994) consisted of three segmental, or interconnected, models aimed at explaining interest development, choice-making, and performance and persistence in educational and vocational contexts. Derived largely from Bandura’s (1986, 1997) general social cognitive framework, SCCT was conceived as an effort to complement and build linkages among existing theoretical approaches to career development. For example, it was intended to broaden Holland’s (1997) theory by focusing on the antecedents of interests and on noninterest predictors of vocational choice, such as self-efficacy beliefs. Following the lead of early work on career self-efficacy (Hackett & Betz, 1981), SCCT was also designed to help extend the range of prior theories by explicitly considering gender, culture, and other aspects of human diversity within the context of career development. Since their introduction, SCCT’s original models have been the focus of numerous extensions and applications. For example, efforts have been made to clarify the nature and functions of contextual influences within the theory (Lent, Brown, & Hackett, 2000); to extend SCCT to particular developmental challenges (e.g., Lent, Hackett, & Brown, 1999) and client groups, such as This article was published Online First July 1, 2013. Robert W. Lent, Department of Counseling, Higher Education, and Special Education, University of Maryland; Steven D. Brown, School of Education, Loyola University. Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Robert W. Lent, Department of Counseling, Higher Education, and Special Education, University of Maryland, 3214 Benjamin Building, College Park, MD 20742. E-mail: [email protected] 557 This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers. This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly. 558 LENT AND BROWN personal goals, maintain vitality, manage multiple roles, and respond to career setbacks. It can be argued that the traditional emphasis of career theories on the “big four” outcomes of interests, choice, performance, and satisfaction is as important and relevant as ever. But it can also be argued that the vast changes occurring in the context of work (e.g., economic uncertainties, global competition, technological advances, decreased job security) require new models and methods for assisting workers to manage their occupational lives (Blustein, 2006; Griffin & Hesketh, 2005; King, 2004; Lent, 2013a). Consistent with the recent thrust of the literature on career adaptability and resilience (e.g., Creed, Fallon, & Hood, 2009; Rottinghaus, Day, & Borgen, 2005; Savickas, 2013), our goal in this article is to develop a model of career self-management that focuses on relatively micro-level processes, in particular, how people negotiate both normative developmental tasks (e.g., making career decisions) and less predictable events and crises (e.g., job loss). Although existing research often treats career adaptability as a set of individual-difference attributes (e.g., Rottinghaus et al., 2005), we offer a complementary focus on adaptive behaviors and on the factors (both environment and person-based) that promote (or deter) their use. This distinction reflects the “doing versus having” sides of personality and functioning (Cantor & Sanderson, 1999). The purpose of the present article, then, is to propose an SCCT model aimed at the processes by which people help to direct their own career and educational behavior in diverse contexts. It is intended to complement, rather than replace, the four existing SCCT models by focusing on a wider array of career adaptation phenomena across the life span. In addition to responding to certain contemporary challenges of career development, the selfmanagement model is designed to link together, within a larger conceptual framework, several streams of research in the vocational and organizational psychology literatures that, at present, are often approached as if they are largely unique and unrelated to one another. Such an integrative framework may lend greater coherence to the existing literature and point to new directions for research and application. Although many studies that have examined social cognitive aspects of career behavior are directly tied to SCCT (e.g., studies relating self-efficacy to choice of science and engineering majors), many others appear to represent largely distinct applications of social cognitive theory. They may be seen as somewhat distant cousins of SCCT because they deal with career behavior at a global rather than domain-specific level or are directed at explaining dependent variables that are not compatible with the original focus of SCCT (cf. Lent & Brown, 2006). In other cases, they clearly deal with important social cognitive phenomena (e.g., study of self-efficacy relative to career decision making, job search, or multiple role management), but their process nature makes it difficult to integrate their findings within an overarching SCCT framework at present. An effort to encompass such phenomena might, then, produce a more comprehensive and useful theory and a better integrated knowledge base. Career Development and Agency in a Social Context Before we proceed further, some conceptual housekeeping is in order. First, we use the term career in a generic sense to encompass work or occupational behavior, regardless of the prestige level of a given form of work, the socioeconomic status of the worker, or the educational level required for the work he or she performs (Lent & Brown, 2013). We appreciate arguments that career implies a privileged view of work behavior, yet the term is firmly engrained in the professional discourse in vocational and organizational psychology and, as a technical term, can be used to connote one’s sequence or totality of work positions. In this sense, housepainters and physicians both have careers. But mindful of the controversies surrounding “career,” we use terms like work and occupation as synonymous with career. Second, the model we present is based on the assumption that people are typically able to assert some measure of personal control, or agency, in at least some aspects of their own career development. We, thus, focus on specific mechanisms through which people are partly able to direct their own career actions to accomplish personal (and collective) ends. Bandura (2001, 2006b) has noted that agency is made possible by humans’ capacities to engage in forethought, intentional action, self-reflection, and selfreaction. These capacities, we believe, enable people to participate more or less actively in their own career choice and development. They also provide a necessary foundation for the provision of career services (e.g., career exploration and planning activities presuppose clients’ capacities for anticipating future possibilities, reflecting on self in relation to environment, and framing, enacting, and revising personal goals). Yet allowing for agentic capacity in no way implies that people fully control their career lives. As Bandura (2006b) has argued, “People do not operate as autonomous agents. Nor is their behavior wholly determined by situational influences. Rather, human functioning is a product of a reciprocal interplay of intrapersonal, behavioral, and environmental determinants. . .” (p. 165). We use the term career self-management because the proposed model focuses on factors that influence the individual’s purposive behavior—not because we assume that individuals act alone in envisioning or achieving their aims. To the contrary, like all modern career theories, SCCT views people as living within a social world, with ever-present opportunities to be influenced by, as well as to influence, others— hence, the S in SCCT. Agency and Adaptive Career Behaviors As we noted earlier, SCCT’s existing models, particularly the interest and choice models, are chiefly concerned with the content or types of fields toward which people gravitate and the activities they perform at school and work. The model of career selfmanagement presented in this article is intended to complement this content level of analysis by focusing on the relatively pervasive processes and mechanisms that direct career behavior within and across the specific fields and jobs people enter. For example, whereas the SCCT choice model is concerned with the self, experiential, and contextual factors that promote pursuit of particular occupational paths (e.g., computer programming, home repair), the self-management model emphasizes the factors that lead people to enact behaviors that aid their own educational and occupational progress (e.g., planning, information-gathering, deciding, goalsetting, job-finding, self-asserting, preparing for change, negotiating transitions) beyond field or job selection alone. The original content focus of SCCT has encouraged inquiry on factors that foster or hinder people’s interest and entry into certain This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers. This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly. CAREER SELF-MANAGEMENT fields (e.g., science, technology, engineering, mathematics careers and majors). However, it has offered less clear guidance for investigators seeking to understand how people negotiate life transitions (e.g., shift from school to work) or engage in common career development tasks (e.g., career exploration and decision making) across fields. The primary reason for this differential utility is that the original SCCT models were explicitly designed to address field or content-specific issues, with less attention given to how they might apply to career process questions. The career self-management model presented here is intended to address this gap, and to complement the earlier models, principally by focusing on the behaviors that people use to try to achieve their own career objectives. These behaviors, which we generally refer to as adaptive career behaviors, are conceptually related to such constructs as career process skills, competencies, meta-competencies, selfregulation, coping skills, and adaptive performance (e.g., Betz & Hackett, 1987; Griffin & Hesketh, 2005). Adaptive career behavior is related to Savickas’s (1997, 2013) notion of career adaptability in that both concepts are concerned with positive functioning and resilience in the context of change, and both entail assumptions that individuals rely on self-regulatory processes, social resources, and dispositional tendencies in adapting to change. The two approaches differ, however, in their view of the specific variables and processes that are responsible for self-direction. Adaptive career behaviors are also relevant to discussions of specific strategies that workers use to manage their career behavior or cope with specific challenges (e.g., proactive, reactive, and tolerant behavior; Griffin & Hesketh, 2005; positioning behavior, influence behavior, boundary management; King, 2004). In this article, we are, however, less concerned with choice of specific strategies for directing career behavior than we are with the antecedent cognitive, affective, behavioral, and socialcontextual processes that more generally enable (or deter) selfdirection in career pursuits. Inquiry on Adaptive Career Behaviors Hackett, Betz, and their colleagues performed foundational work on adaptive career behaviors, which they referred to as “career competencies” or “process skills.” For example, Betz and Hackett identified a number of competencies that were seen as key to the career development of college students (Betz & Hackett, 1987) and professional women (Hackett, Betz, & Doty, 1985). Examples of these competencies included self-assertion, general planning, career advancement, and cognitive coping skills. Betz and Hackett found that self-efficacy for such process skills was moderately to strongly associated with observer-rated use of these skills among female and male college students in the United States. That is, students reporting higher self-efficacy demonstrated greater behavioral competence. In a partial replication and extension of this study, Sadri (1996) found that self-efficacy was moderately related to career competencies across samples of British and U.S. college students. There are several other good examples of social cognitive inquiry on process dimensions of career behavior. For instance, a sizable body of research has examined self-efficacy in relation to career decision-making skills. A recent meta-analysis indicated that career decision self-efficacy is (a) inversely (and strongly) related to career indecision, (b) positively (and moderately to 559 strongly) related to peer support and vocational outcome expectations, and (c) negatively (and weakly) related to career barriers (Choi et al., 2012). A number of studies have also examined self-efficacy in relation to job search capabilities. Kanfer, Wanberg, and Kantrowitz’s (2001) meta-analysis indicated that job search self-efficacy produced small to moderate, positive relations with job search behavior and number of job offers received. (We consider inquiry on career decision making and the job search process in more depth in a later section.) Other examples of social cognitive inquiry on process aspects of career behavior include self-efficacy in relation to college-going intentions (Ali, McWhirter, & Chronister, 2005), organizational citizenship behavior (Todd & Kent, 2006), work–family conflict (Cinamon, 2006), and training motivation (Colquitt, LePine, & Noe, 2000). We see several good reasons to try to bridge inquiry on such topics with SCCT. In particular, it is not always clear whether studies involving social cognitive process variables, such as career decision self-efficacy (CDSE), actually test SCCT’s hypotheses in a formal sense. For example, Choi et al. (2012) sought to “obtain a clearer understanding of CDSE’s roles within the framework of social cognitive career theory” (p. 443). We have generally taken the position that studies, say, linking CDSE to career indecision are conceptually related to SCCT but do not formally test it because the theory was not explicitly designed either to incorporate CDSE or to predict career indecision as a general state—it is rather designed to predict choice of domain-specific options, such as type of academic major or occupation (cf. Lent & Brown, 2006). An effort to bridge SCCT with such process-focused inquiry may both broaden the theory’s range of applicability and clarify which SCCT hypotheses, if any, are being tested in a given study. Definition and Classification of Adaptive Career Behaviors Across the Life Span Before outlining our model of career self-management, it would be useful to define more formally what we mean by adaptive career behaviors. We see these as behaviors that people employ to help direct their own career (and educational) development, both under ordinary circumstances and when beset by stressful conditions. They include behaviors that are used both proactively and reactively (i.e., either when a given developmental task or contextual challenge is anticipated or after it is encountered). Career and educational development encompasses periods of work preparation, entry, adjustment, and change. As noted earlier, synonyms for adaptive career behaviors include career process skills, agentic competencies, instrumental behaviors, coping skills, and selfregulatory behaviors. As mechanisms of agency, such behaviors “enable people to play a part in their self-development, adaptation, and self-renewal” (Bandura, 2001, p. 2). Table 1 offers a selected list of adaptive career behaviors, organized by career-life period, and life role. The developmental framework for the table is adapted from Super’s life span, life space theory (Super, Savickas, & Super, 1996). In using Super’s framework, we selected or modified particular developmental tasks that could be readily framed as acquirable skills. In listing adaptive behaviors, we borrowed from Turner and Lapan’s (2013) integrative contextual model of career development, Hackett et al.’s (1985) taxonomy of career competencies, and Lent’s (2013a) discussion of career preparedness tasks. We were also guided by LENT AND BROWN 560 Table 1 Adaptive Career Behaviors, Organized by Career-Life Period and Major Life Role Developmental period, primary life role This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers. This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly. Growth Child, student Exploration Adolescent, student Establishment Worker Maintenance Worker Disengagement/Reengagement Retiree, leisurite Partial list of adaptive behaviors 䡲 Developing basic self-regulation (e.g., goal-setting, study, time management) skills 䡲 Developing positive work habits and attitudes 䡲 Developing social skills 䡲 Developing problem-solving skills 䡲 Developing decision-making skills 䡲 Developing subject-specific academic skills 䡲 Developing extracurricular (RIASEC) skills 䡲 Developing preliminary work-relevant interests and values 䡲 Forming provisional vocational aspirations and self-concept (e.g., sense of P-E matching possibilities), typically without a specific plan—I could be a . . . someday 䡲 Continuation and elaboration of Growth period tasks 䡲 Developing work readiness and employability skills 䡲 Exploring possible career paths (e.g., through reading, observing, undertaking informal or formal self-assessments of interests, abilities, values) 䡲 Acquiring career-relevant experiences and skills (e.g., through school, part-time work, volunteering) 䡲 Making career-relevant decisions (e.g., regarding leisure activities, elective courses) 䡲 Implementing decisions (e.g., applying for jobs, training, college admission) 䡲 Managing transitions (e.g., school-to-school, school-to-work, school-to-college) 䡲 Forming more specific vocational goals and plans—I want to be a . . . and here is how I plan to get there . . . 䡲 Continuation and elaboration of (and possibly recycling through) Exploration period tasks 䡲 Searching for and obtaining employment 䡲 Becoming socialized within one’s work environment 䡲 Adjusting to work requirements 䡲 Managing work stresses and dissatisfactions 䡲 Managing work–family–life conflicts 䡲 Coping with negative events, such as job layoff or harassment 䡲 Developing new interests and skills (e.g., leadership) 䡲 Refining interpersonal, political, and networking skills 䡲 Engaging in self-advocacy/assertion (e.g., seeking raises, promotions, new tasks and titles) 䡲 Engaging in organizational citizenship behaviors, such as mentoring others 䡲 Managing aspects of one’s personal identity at work (e.g., identity as a sexual, racial, or religious minority member or person with a disability) 䡲 Preparing for career-related changes or “emergencies” 䡲 Revising or stabilizing vocational goals and plans—I am a . . . and want to be a . . . and here is how I plan to get (or stay) there . . . 䡲 Continuation and elaboration of Exploration and Establishment period tasks 䡲 Recycling through Exploration and Establishment period tasks, especially if one has voluntarily or involuntarily changed job/career paths 䡲 Building job niches (e.g., forging a leadership or specialist role) 䡲 Developing career self-renewal plans 䡲 Preparing for retirement, leisure, bridge employment, or an encore career 䡲 Revising or stabilizing vocational goals and plans—I am a . . . and want to be a . . . and here is how I plan to get (or stay) there . . . 䡲 Recycling through Exploration and Establishment period tasks, especially as one plans to take on different job responsibilities or leisure, family, or volunteer roles 䡲 Managing transition from work to leisure, community service, bridge employment, or an encore career 䡲 Coping with stresses and conflicts related to one’s new role and responsibilities 䡲 Revising vocational goals and plans—I have been a . . . and want to be a . . . and here is how I plan to get (or stay) there . . . Note. General developmental framework adapted from Super et al. (1996). Certain growth and exploration tasks (e.g., work readiness and employability skills) were adapted from Turner and Lapan (2013). Certain establishment and maintenance tasks were adapted from Hackett, Betz, and Doty (1985) and Lent (2013a). RIASEC ⫽ Realistic, Investigative, Artistic, Social, Enterprising, and Conventional; P-E ⫽ person-environment. recent observations about the pace and nature of changes in the workplace (e.g., Griffin & Hesketh, 2005). Behaviors needed to cope with contextual challenges, such as job loss, are also included within this framework because career development involves managing events that are sometimes unexpected as well as tasks that are seen as relatively normative, predictable, or developmental in nature. In addition, we include adaptive behaviors that are of general relevance as well as those that serve the needs of particular groups of workers (e.g., management of work–family roles or sexual identity at work). This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers. This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly. CAREER SELF-MANAGEMENT 561 In keeping with developmental and constructionist (e.g., Savickas, 2013; Super et al., 1996) views, we assume that individuals will negotiate developmental tasks at different paces, some will necessarily recycle to tasks associated with earlier periods, and the tasks associated with some periods can overlap considerably. Where recycling occurs, it does not necessarily signify developmental failure or floundering; it may well be mandated by circumstances (e.g., job loss) or personal intentions (e.g., voluntary career renewal, the desire to locate better fitting or more meaningful work). Changes in the context of work have rendered many people’s careers less linear, hierarchical, stable, or organizationcentric than in times past. Thus, for example, an individual wishing to change career paths (or forced to do so by circumstance) may well need to move from the Maintenance period back to tasks associated with the Establishment and even Exploration periods. Likewise, many persons presumably in the Disengagement period will, either by economic necessity or choice, engage in Exploration and Establishment period tasks in order to pursue bridge employment or “encore career” options. We, therefore, refer to Disengagement/Reengagement to capture the contemporary dynamic nature of “retirement”. performance of these behaviors may be facilitated by certain traits as well as by environmental supports (e.g., friends, bosses, family members) and social cognitive factors (e.g., self-efficacy). We also prefer to view adaptive career behaviors as instrumental or intermediate to other, more distal outcomes, rather than as representing ultimate outcomes in themselves. That is, they may lead to or potentiate more ultimate outcomes, such as career decidedness or employment status. They do not, however, guarantee favorable career outcomes. For instance, searching actively for jobs often leads, in turn, to interviews and employment offers (e.g., Saks, 2006), but search behaviors do not ensure a quick or successful route to employment. Given the multiple, systemic (e.g., economic) factors at play that exceed personal control, it should not be surprising that adaptive behaviors often correlate only modestly with the outcomes they are designed to effect (e.g., Côté, Saks, & Zikic, 2006). Still, they often represent the most viable means for individuals to pursue their career goals. It is, therefore, valuable to study the antecedents of adaptive behaviors, along with the contextual and personal factors that facilitate and impede their use. Performing Developmental Tasks and Coping With Challenges We present the career self-management model in two parts. We first focus on relatively proximal person and contextual influences on adaptive career behaviors and the outcomes of these behaviors. We then discuss the more distal antecedents and experiential sources of adaptive career behaviors. Adaptive career behaviors include a fairly heterogeneous set of behaviors that form at least two larger conceptual clusters. The first cluster involves engaging in relatively normative and proactive developmental tasks that, in the Growth period, are associated with age-related cognitive development (e.g., acquisition of selfregulation skills) and nurtured by social learning experiences (e.g., modeling, performance feedback). These skills form a scaffolding for further career development. Included within the developmental task cluster are career-relevant tasks that are socially prescribed for most individuals. These include, for example, Exploration period activities such as making career-related decisions (e.g., choosing elective academic courses, pursuing career-relevant hobbies and provisional employment) and Establishment period tasks, such as seeking work entry after the completion of formal education. The second cluster involves what may be termed coping skills and processes. These are typically reactive behaviors that are initiated (a) to negotiate life-role transitions (e.g., school-to-work, work-to-parent, return to work) and (b) to adjust to challenging, and often unforeseen, work and work–life situations, such as role conflicts, work stress, and job loss. Whether involving the management of transitions or coping with difficult events or work conditions, the focus is on ways in which people attempt to steer themselves around hurdles and to achieve a reasonable level of career adaptation. The effective use of coping skills is part of the network of factors that foster resilience in career development and that aid people to anticipate and try to forestall negative career events (Lent, 2013a). The Link Between Adaptive Behavior and Career Outcomes We find it helpful to conceptualize career adaptability in terms of a collection of behaviors that can be learned, rather than only as traits that people possess. However, as we discuss below, the A Model of Career Self-Management Proximal Antecedents of Adaptive Career Behaviors Because it represents an extension of SCCT’s choice-content model, the model of career self-management relies on many of the same core variables, only defined and contextualized in somewhat novel ways. In particular, as shown in Figure 1, the exercise of adaptive career behaviors, such as engaging in career exploration or job-finding activities, is assumed to be affected by self-efficacy, outcome expectations, goals, and environmental supports and barriers. In keeping with the prior SCCT models, each of these proximal antecedents of adaptive behavior is conceived in domain-, state-, context-, and temporally specific terms. That is, rather than constituting global adaptability traits, they are seen as personal or environmental attributes that are relatively malleable and responsive to particular developmental or situational challenges. However, as we note later in this section, certain traits are also assumed to influence the exercise of adaptive career behaviors or their outcomes. Cognitive-person factors. Self-efficacy refers to personal beliefs about one’s ability to perform particular behaviors or courses of action. Self-efficacy can be assessed in several ways (see Lent & Brown, 2006). In research on SCCT, it has been most common to assess content- or task-specific self-efficacy (e.g., beliefs about one’s ability to complete the requirements of a particular academic major) and/or coping efficacy (beliefs about one’s ability to negotiate specific obstacles). Another form of self-efficacy, particularly relevant to the career self-management model, is process efficacy, which refers to perceived ability to manage specific tasks necessary for career preparation, entry, adjustment, or change across diverse occupational paths. Examples include self-efficacy at mak- LENT AND BROWN 562 Personality & Contextual Influences Proximal to Adaptive Behavior 19 Person Inputs p - Predispositions - Abilities - Gender - Race/ethnicity - Disability/ Di bilit / Health status 11 8 9 12 7 Self-efficacy Expectations 17 1 10 13 3 Learning Experiences (sources of efficacy information) 14 Goals 16 Actions 5 15 6 Outcomes/ Attainments 4 This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers. This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly. Background Contextual Background Affordances 18 Outcome Expectations 2 20 Figure 1. Model of career self-management. The numbered paths are discussed in the article text below. Adapted from “Toward a unifying social cognitive theory of career and academic interest, choice, and performance,” by R.W. Lent, S. D. Brown, & G. Hackett, 1994, Journal of Vocational Behavioral, 45, p. 93. Copyright 1993 by R. W. Lent, S. D. Brown, & G. Hackett. Reprinted with permission. ing career decisions (Betz, Klein, & Taylor, 1996), using job search strategies (Solberg et al., 1994), and managing multiple work/life roles or conflicts (Cinamon, 2006). Both process and coping efficacy are the central forms of self-efficacy in our selfmanagement model and are also conceptually related to Bandura’s (2006a) notion of self-regulatory efficacy, referring to perceived ability to guide and motivate oneself to perform self-enhancing behaviors, such as studying, despite deterring conditions. Outcome expectations are beliefs about the consequences of performing particular behaviors or courses of action (e.g., expectations that valued, neutral, or unpleasant outcomes will occur). Bandura (1986) has highlighted three types of anticipated consequences: social (e.g., benefits to one’s family), material (e.g., financial gain), and self-evaluative (e.g., self-approval) outcomes. The essential difference between self-efficacy and outcome expectations is captured, respectively, in the questions, “Can I do it?” and “What will happen if I try?” Social cognitive theory assumes that people are more likely to attempt and sustain behaviors when they believe both that they have the necessary capabilities to perform them and that the effort will produce desired consequences. Where they doubt their competencies or anticipate neutral or negative outcomes, people may avoid or procrastinate at performing particular behaviors, put less effort into them, or give up relatively quickly when obstacles are encountered. For example, as we elaborate later, sustained involvement in career decisionmaking activities may be facilitated both by career decisionmaking self-efficacy beliefs and by expectations that engaging in such activities will result in valued outcomes. Self-efficacy and outcome expectations are seen as promoting adaptive career behaviors both directly (Paths 1 and 2, respectively) and indirectly (Paths 3 and 4, respectively), through the mediating effects of personal goals (Path 5). Several theories propose that actions are partly motivated by goals, or intentions to perform the actions (Ajzen, 1988; Bandura, 1986). These theories also suggest that certain types or qualities of goals are especially facilitative of action. For example, people are more likely to transform their goals into actions when the goals are clear, specific, stated publicly, congruent with personal values, and proximal to actions. As shown in the right half of Figure 1, particular adaptive behaviors are most likely to be enacted and sustained when people possess favorable self-efficacy, outcome expectations, and goals in relation to these behaviors. Goal-directed actions (e.g., engaging in career exploratory or job search behaviors) make it more likely that people will attain the outcomes they seek (e.g., to identify satisfying career options or obtain a job) (Path 6). Self-efficacy is also seen as having a direct link to outcomes, or attainments (Path 7), because of its roles in helping people to organize their actions and to persist in the face of challenges. It should be noted that the cognitive-person variables in the model are seen as operating in concert with environmental influences (e.g., the support of one’s coworkers and supervisor; local economic conditions) that have the capacity to enable or limit agency and to codetermine the outcomes of adaptive behaviors. They also operate jointly with other person inputs, such as personality factors. We turn next to the roles of these additional factors in the model. Contextual and personality factors. People are more likely to set and implement goals to engage in adaptive career behaviors when they are buoyed by environmental (e.g., social, financial) supports and relatively free of barriers that can constrain their exercise of agency. Theoretically, contextual supports and barriers operate through several pathways; they may promote goals and actions directly (Paths 8 and 9, respectively) as well as moderate (i.e., strengthen or weaken) the relation of goals to actions (Lent et al., 2000; Path 10). Research has suggested that supports and barriers may also relate indirectly to goals, via their linkages to self-efficacy (Path 11) and outcome expectations (this path is not shown in Figure 1) (Sheu et al., 2010). That is, the presence of supports (and the absence of barriers) may strengthen self-efficacy and outcome expectations. Contextual influences (e.g., reactions of important others, having access to environmental resources) can also directly affect the outcomes that follow adaptive behaviors (Path 12) and moderate action– outcome relations (Path 13). Certain personality variables, in particular, conscientiousness, one of the Big Five factors, may also facilitate the use of adaptive behaviors that require planning and persistence (e.g., career exploration, job searching). Other personality factors may be relevant to adaptive behaviors, such as networking or interviewing, that in- This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers. This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly. CAREER SELF-MANAGEMENT volve social interaction (e.g., extraversion) or coping with adverse events (e.g., extraversion or positive affect, neuroticism or negative affect). Openness to experience may facilitate adaptive behaviors where the task entails imagining or entertaining various choice or problem-solving options. (see Brown & Hirschi, 2013, for a summary of research linking Big Five traits to career development outcomes). The specific personality dimension and its relevant pathways may, thus, depend on the adaptive behavior of interest, its context, and performance requirements. As a rule, personality factors may influence career adaptation by facilitating (or deterring) behavioral performance or by engaging emotional coping tendencies. For instance, conscientiousness is characterized by a set of behavioral tendencies (e.g., organization, goal setting, perseverance) that is likely to promote effective performances in most contexts. Extraversion is associated with tendencies to experience positive affect and to engage in social interactions, both of which are advantageous in advancing one’s career development, especially when faced with setbacks. However, given their global nature, traits might ordinarily be expected to yield modest relations to domainor task-specific social cognitive measures and adaptability outcomes (see, e.g., Lent & Brown’s, 2006, discussion of predictorcriterion compatibility). The role of interests and abilities. It should be noted that, while educational or vocational interest (e.g., one’s pattern of activity likes and dislikes) plays a key role in SCCT’s choicecontent model, helping to draw people toward particular academic and occupational fields, it is omitted from the self-management model because most of the adaptive behaviors we have in mind seem more likely to be driven by developmental presses (e.g., the need to make a career decision), personal goals (e.g., career advancement intentions), or environmental considerations (e.g., coping with adverse work events) than by activity interest per se. The choice-content and process perspectives can be seen as complementary, and there may be instances in which researchers will wish to use them in parallel fashion. For example, in applications involving job or career change (including efforts at career renewal and choice of organizational citizenship roles), the selfmanagement model would focus on the person and contextual variables that enable people to engage in career change (e.g., beliefs about one’s ability to negotiate change—a process question), whereas the interest and choice models may be used to predict the specific types of activities individuals will find attractive (a content question). Abilities (e.g., cognitive and interpersonal talents) are also likely to play important roles in the performance of adaptive career behaviors, helping to determine how well people enact certain behaviors and the likelihood that their efforts will be successful. For example, some people master job interviewing skills better than others do. Thus, quality of performance is likely to depend on ability as well as self-efficacy (which helps people to deploy their abilities; Bandura, 1986) and the other proximal variables in the self-management model. Research on career self-management could include a focus on abilities, particularly where quality of performance is of special interest (i.e., how well people perform particular adaptive career behaviors rather than simply which behaviors they attempt). 563 Distal Antecedents and Experiential Sources of Adaptive Career Behaviors The left-hand side of Figure 1 displays the distal antecedents of career adaptation along with the experiential sources of selfefficacy and outcome expectations. Consistent with SCCT’s general model of choice behavior (Lent et al., 1994), the distal variables include a variety of person inputs (e.g., gender, culture, personality, ability, health/disability status) and contextual affordances (e.g., educational quality, socioeconomic resources) that, together, comprise the individual’s initial “social address.” (Distal person and contextual variables covary in the sense that educational and career-relevant resources are often differentially conveyed to children and adolescents on the basis of how key social agents respond to their gender, race/ethnicity, and other person characteristics.) Although it represents a starting point, developmentally speaking, this address provides an important social learning context for acquiring self-efficacy and outcome expectations regarding adaptive career behaviors. An important point to highlight is that person inputs, such as gender, ethnicity, social class, and sexual orientation, are seen as affecting the exercise of career agentic behaviors largely indirectly, for example, via cultural socialization experiences that convey information about self-efficacy (e.g., one’s capabilities to perform particular behaviors) and outcome expectations (e.g., which values are important to pursue, what can be expected if one chooses to pursue them). More specifically, such socialization or learning experiences convey four types of information relevant to self-efficacy (Path 14) and outcome expectations (Path 15): personal performance accomplishments, observational learning (or modeling), social encouragement and persuasion, and physiological and affective states and reactions. In addition to these four types of experience, self-efficacy is seen as affecting outcome expectations (Path 16) because people often expect more positive outcomes when they view themselves as capable performers. A more thorough discussion of these sources can be found in Bandura (1997) and Lent et al. (1994). The four learning experiences largely mediate the effect of person inputs (Path 17) and background contextual affordances (Path 18) on the social cognitive variables that enable career agency. However, social address variables may also influence goal-setting and actions to the extent that they convey continuous, proximal information about which goals are deemed socially or culturally normative and which actions are likely to be supported or discouraged by the environment (Path 19). Finally, the outcomes that follow enactment of adaptive behaviors (e.g., perceived successes or failures) form a feedback loop to learning experiences (Path 20). That is, one’s attainments or disappointments help to stabilize or revise self-efficacy and outcome expectations because they offer ongoing commentary about one’s capabilities and the likely outcomes of one’s actions. Two Relevant Applications: Research on Career Exploration and Job Search Behavior A few examples may help to clarify the proximal causal relations displayed in Figure 1. Career exploration and planning. In the first example, the self-management model suggests that the decision to engage in LENT AND BROWN This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers. This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly. 564 career exploratory and decision-making behaviors—which are typically seen as developmental tasks in the Exploration period—is made more likely when people (a) possess favorable beliefs regarding their exploratory and decision-making skills, (b) expect positive outcomes to result from such efforts (e.g., exploring career options will help lead to a satisfying choice), (c) set clear, specific goals to engage in these behaviors, (d) have adequate environmental supports (e.g., parents, friends, a career education course) and minimal barriers (e.g., critical peers), and (e) possess favorable levels of certain personality tendencies (e.g., high conscientiousness, extraversion, and openness; low neuroticism; Brown & Hirschi, 2013). Rather than operating as separate influences, the model points to the ways in which these factors interrelate and jointly determine the use and persistence of adaptive exploratory and decision-making behaviors. These pathways are shown in Figure 2. Although a number of studies have linked CDSE to level of career indecision (Choi et al., 2012), relatively few have examined additional social cognitive variables that are hypothesized to operate in tandem with CDSE (e.g., outcome expectations, goals, supports) or related these variables to exploratory behavior, which is typically assumed to promote career decidedness or reduce indecision. In one relevant study, Betz and Voyten (1997) found that CDSE was significantly related to career outcome expectations, but it did not explain unique variance beyond outcome expectations in predicting college students’ career exploratory intentions (a goal variable). By contrast, Huang and Hsieh (2011) found that CDSE and outcome expectations both yielded significant direct paths to exploratory intentions in a sample of Taiwanese college students. However, neither study included a measure of exploratory behavior. Including a more complete set of social cognitive variables as well as two indicators of adaptive behavior (planning and exploration), Rogers, Creed, and Glendon (2008) reported that CDSE, goals, and two aspects of personality (conscientiousness and openness) each accounted for unique variance in the prediction of Australian high school students’ career planning behavior. In addition, the presence of social support strengthened the relation Figure 2. between goals and planning behavior. However, only goals and social support were uniquely predictive of career exploration behavior. Rogers and Creed (2011) also examined social cognitive and personality predictors of career planning and exploration in three grades of Australian high school students. Including all predictors in the regression analyses, CDSE and goals were each found to explain unique variance in career planning, both crosssectionally and over a 6-month period. CDSE also accounted for unique variance in exploration across grades and time periods. The predictive utility of outcome expectations, supports, and personality variables (e.g., neuroticism, extraversion) varied over grades and time periods. Other researchers have also found CDSE (Gushue, Clarke, Pantzer, & Scanlan, 2006) and career search self-efficacy (Solberg, Good, Fischer, Brown, & Nord, 1995) to be related to students’ engagement in exploratory activities. Choi et al.’s (2012) meta-analysis indicated that CDSE yields moderate to large bivariate correlations with certain other social cognitive variables (outcome expectations, peer support) and with career indecision. In one longitudinal study, however, CDSE was not significantly associated with change in career indecision over a 2-year period in high school students (Creed, Patton, & Prideau, 2006). It is not clear whether these nonsignificant longitudinal findings were based on methodological (e.g., age of the participants, length of the interval between assessments, statistical power) or theoretical considerations. Collectively, the findings we have reviewed suggest the need for additional inquiry linking a fuller set of social cognitive variables to career exploratory behaviors and decisional outcomes (e.g., indecision, anxiety). Job search. The job search process offers another good example of adaptive career behavior. Job search can occur in at least two contexts. First, in the developmental context (e.g., during the Establishment period), people typically search for initial jobs that are, under favorable conditions, consistent with their work personalities (e.g., interests, abilities, values) and that may represent an effort to implement their choice-content goals (e.g., to become an architect or a carpenter). (Person-job fit may, however, be a less salient consideration under less favorable conditions, e.g., where there is need for immediate income or access to health benefits.) Model of career self-management as applied to career exploration and decision-making behavior. This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers. This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly. CAREER SELF-MANAGEMENT This process may be repeated on any number of later occasions if and when people decide voluntarily to seek other jobs or to switch career directions. Second, in the coping context, the job search process can be occasioned by involuntary job loss, which may have been sudden, unexpected, and off-time developmentally (e.g., due to organizational merger or factory closure). In the developmental context, the amount of time and effort that people devote to the job search, and their degree of persistence when faced with disappointing results, may partly depend on (a) self-efficacy regarding their job search and self-presentation skills, (b) outcome expectations regarding the job search process (e.g., low expectations of finding a desirable position because of the current economic context), (c) goals (e.g., intentions to perform specific search behaviors), (d) the availability of social network supports and exposure to barriers (e.g., problems with transportation or childcare), and (e) tendencies toward conscientiousness and extraversion/positive affect (Brown & Hirschi, 2013) (see Figure 3). These same factors may influence the job search process in the context of coping with unexpected job loss— but the emotional toll of such loss may also call upon additional coping/problem-solving skills and environmental supports to help restore emotional wellbeing (cf. Lent, 2004). Studies of the job search process in recent years have often included a focus on social cognitive and personality variables (Jome & Phillips, 2013). For example, work by Saks and his colleagues has linked job search behavior and its outcomes (e.g., job offers, employment status) to job search self-efficacy beliefs (Côté et al., 2006; Saks, 2006; Saks & Ashforth, 1999; Zikic & Saks, 2009), job search intentions and clarity (two goal variables; Zikic & Saks, 2009), and positive affectivity and conscientiousness (Côté et al., 2006). Kanfer et al. (2001) offered meta-analytic evidence of bivariate correlations between job search behavior and a number of the variables in our career self-management model (e.g., job search self-efficacy, goals, social support, extraversion, conscientiousness). What the model may add to this inquiry is a conception of how a fuller set of social cognitive variables (e.g., including outcome expectations and contextual barriers) function together, rather than individually, relative to other predictors (and outcomes) of job search behavior. Figure 3. 565 Although research on career exploration/decision making and job search behavior provide good examples of existing inquiry relevant to the self-management model, the same set of social cognitive predictors may be adapted to help explain the ways in which people navigate a variety of additional developmental tasks, transitions, and coping challenges, both large and small (e.g., managing dual-career and multiple life-role conflicts, dealing with career advancement hurdles, asking for a raise or promotion, engaging in organizational citizenship behaviors). Specific applications would call for alterations in how the cognitive-person variables are operationalized, what aspects of the environment are deemed most relevant, and which specific personality variables, if any, may help to determine use of particular adaptive behaviors. Thus, the proposed theory is intended to offer a broad, flexible template for the study of career adaptation. Implications for Future Research and Practice It is our hope that the social cognitive model of adaptive career behavior will help to organize existing inquiry and stimulate new research on topics that have yet to receive much sustained research attention as well as on ones that have received a fair degree of inquiry but with inclusion of only a limited set of social cognitive predictors. For example, existing social cognitive research on process aspects of career development (e.g., decision making) often focuses on self-efficacy, while overlooking other theorybased predictors of career behavior. Inclusion of outcome expectations, goals, environmental supports and barriers, and personality variables may clarify the processes underlying adaptive career behavior. By focusing on process aspects of career development, the new model may also encourage greater study of a broader range of topics—such as multiple-role management, work transitions, sexual identity management at work, and self-directed career renewal—from a social cognitive perspective (e.g., Cinamon, 2006; Lidderdale, Croteau, Anderson, Tovar-Murray, & Davis, 2007). We are suggesting that the self-management model may be used as a framework for studying engagement in these and other types of adaptive career behavior. For example, the degree to which people Model of career self-management as applied to job search behavior. This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers. This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly. 566 LENT AND BROWN engage in retirement planning may be a function of their beliefs about their ability to plan for and negotiate retirement adjustment (i.e., self-efficacy; Carter & Cook, 1995), the outcomes they see associated with, and the goals they set for, retirement planning, their characteristic levels of conscientiousness, and their available supports and barriers (e.g., retirement savings, supportive family members, access to preretirement workshops). The development of strong retirement planning self-efficacy beliefs and outcome expectations are facilitated by learning experiences (e.g., relevant mastery experiences with career-life planning and the availability of successful models). Such a process perspective might complement a content focus on what specific postretirement activities people wish to pursue (e.g., caring for grandchildren, volunteer tutoring, playing golf, seeking a bridge or encore career). These complementary process/content views on retirement adjustment would call for different methods of operationalizing the social cognitive variables (e.g., self-efficacy relative to decisional and planning behaviors vs. caring/leisure/alternative occupational activities). The ways in which the social cognitive variables are assessed in a particular application of the self-management model will depend on the phenomenon of interest. For example, in the retirement planning context, process or self-regulatory efficacy beliefs may be most salient. By contrast, in the context of coping with job loss, it may be useful to study both coping and process efficacy (e.g., perceived capabilities to negotiate the emotional and social consequences of job loss and to seek new work opportunities). In addition to self-efficacy, the other social cognitive variables would need to be conceptualized and measured in ways that are domainand task specific. This may sometimes call for multidimensional measures of particular constructs (e.g., measures that capture multiple aspects of self-efficacy or outcome expectations). The new model may also help to extend SCCT-based inquiry developmentally. At present, the majority of SCCT inquiry has involved career development in late adolescence and early adulthood (Lent, 2013b). By highlighting growth and exploration period tasks associated with childhood and early adolescence (e.g., exploring potential career paths, making academic decisions, managing educational transitions) as well as establishment, maintenance, and later life tasks (e.g., managing stresses, coping with negative events, developing new work skills) in adulthood, the model may promote study of social cognitive processes and variables across the life span. The model may also offer a useful platform for designing and testing interventions aimed at particular developmental tasks or contextual challenges. We hope that our taxonomy of developmental tasks and coping behaviors, organized by life periods and roles, and inspired by Super’s life span, life space theory (Super et al., 1996), will prove heuristic in such efforts. Another direction for research could lie in efforts to compare and, possibly, integrate different conceptions of career adaptability. For example, Savickas (2013) has suggested that career adaptability is partly fostered by global dispositional tendencies toward career concern, control, curiosity, and confidence. The SCCT approach likewise includes dispositional resources to help account for the process of career adaptation, though these are largely framed in terms of Big Five personality factors. SCCT is also distinctive in its focus on other adaptive mechanisms, such as self-efficacy, and in its predictions about how the various sources of adaptive career behavior interrelate. Despite their differences, the two models have certain potential points of convergence. For example, career confidence may represent a trait-oriented variant of self-efficacy, career concern and control may both reflect aspects of conscientiousness (a Big Five variable), and career curiosity may represent openness (another Big Five variable). Future research might examine the relations among these constructs and explore their joint and differential contribution to various behaviors and outcomes associated with career adaptation. Although the new SCCT model is focused on individuals’ self-regulatory behaviors, it might be noted that it could also be adapted to the context of collective (or group-managed) career pursuits. For example, how work groups or other collectives (e.g., labor unions) adapt to or seek to impact organizational change (e.g., in terms of shaping working conditions, rewards, or work outputs) may depend, in part, on how they appraise their joint efficacy to deal with the change, along with their shared perceptions of anticipated outcomes, group goal-setting, and coordination of goal-directed actions. This focus on the collective level of career adaptation could build on Bandura’s (1997) general extension of social cognitive theory to group functioning. Pending research tests of the career self-management model, we think the model’s main practical value may lie in informing developmental and preventive interventions, such as career education in secondary schools, and workshops and coaching in work organizations, which can help students and workers to anticipate and prepare for predictable career developmental tasks by developing necessary skills and corresponding self-efficacy beliefs; promoting positive outcome expectations; setting goals; and overcoming barriers to, and building supports for, the adaptive behaviors associated with these tasks. The model can also be used to raise consciousness about certain events that, although less predictable, may nevertheless have a good chance of occurring at some point during the course of many people’s work lives (e.g., job loss, work dissatisfaction, job plateauing, work– family conflict; Lent, 2013a). Because many of these tasks and events tend to be associated with particular life periods, there may be value in addressing them in cohort-based, group psychoeducational interventions offered either live or online. The taxonomy of adaptive behaviors in Table 1 may provide a starting point for such interventions. Although we see developmental and preventive interventions as particularly well tied to the self-management model, we also believe that the model has useful implications for remedial counseling. For example, counselors can use the model to identify self-management tasks (e.g., networking, self-advocacy) that clients are having particular difficulty mastering or that seem to be limiting their career advancement. The four experiential sources of efficacy information can be used to derive intervention elements, and other model variables can also be highlighted as potential intervention targets, depending on the role the counselor judges them to be playing in the client’s difficulties. For example, the counselor may offer goal-setting or support-building interventions, if these issues seem to be circumscribing the client’s progress. Where particular personality variables seem to be impeding career progress, these can be approached from either behavioral or cognitive-emotional angles. For example, the counselor might consider what behavioral aspects of conscientiousness would be helpful for the client to develop, or which emotional regulation strategies (e.g., self-awareness, reframing) might be used to help the client negotiate problems with negative affect or neuroticism. CAREER SELF-MANAGEMENT This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers. This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly. Conclusions In sum, we have described an extension of SCCT to the developmental tasks and coping challenges of career self-management. Whereas the earlier SCCT models were aimed primarily at contentoriented issues (e.g., field choice), the self-management model focuses on processes underlying adaptive career behavior (e.g., career exploration, job seeking, career advancement) that occur across occupational paths. We envision the new model as a broad framework that can be adapted to the study of a wide range of adaptive career behaviors. For example, research on the process of career decision making could focus on the operation of self-efficacy, outcome expectations, goals, supports and barriers, and relevant traits (e.g., conscientiousness); on the behaviors (e.g., self and environmental exploration) to which they are presumed to lead; and, possibly, on the more ultimate decisional outcomes that result (e.g., decidedness, choice commitment, decisional anxiety). Although designed to be consistent with existing findings that have examined some of its elements (especially in the domains of career decision making and the job search process), the model’s explanatory utility—and the joint operation of its component variables—needs to be assessed in future research. References Ajzen, I. (1988). Attitudes, personality, and behavior. Stony Stratford, UK: Open University Press. Ali, S. R., McWhirter, E. H., & Chronister, K. M. (2005). Self-efficacy and vocational outcome expectations for adolescents of lower socioeconomic status: A pilot study. Journal of Career Assessment, 13, 40 –58. doi:10.1177/1069072704270273 Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall. Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. New York, NY: Freeman. Bandura, A. (2001). Social cognitive theory: An agentic perspective. Annual Review of Psychology, 52, 1–26. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.52 .1.1 Bandura, A. (2006a). Guide for constructing self-efficacy scales. In F. Pajares & T. Urdan (Eds.), Self-efficacy beliefs of adolescents (pp. 307–337). Greenwich, CT: Information Age. Bandura, A. (2006b). Toward a psychology of human agency. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 1, 164 –180. doi:10.1111/j.1745-6916.2006 .00011.x Betz, N. E. (2008). Advances in vocational theories. In S. D. Brown & R. W. Lent (Eds.), Handbook of counseling psychology (4th ed., pp. 357–374). New York, NY: Wiley. Betz, N. E., & Hackett, G. (1987). Concept of agency in educational and career development. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 34, 299 –308. doi:10.1037/0022-0167.34.3.299 Betz, N. E., Klein, K., & Taylor, K. (1996). Evaluation of a short form of the Career Decision-Making Self-Efficacy scale. Journal of Career Assessment, 4, 47–57. doi:10.1177/106907279600400103 Betz, N. E., & Voyten, K. K. (1997). Efficacy and outcome expectations influence career exploration and decidedness. Career Development Quarterly, 46, 179 –189. doi:10.1002/j.2161-0045.1997.tb01004.x Blustein, D. L. (2006). The psychology of working: A new perspective for career development, counseling, and public policy. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum. Brown, S. D., & Hirschi, A. (2013). Personality, career development, and occupational attainment. In S. D. Brown & R. W. Lent (Eds.), Career development and counseling: Putting theory and research to work (2nd ed., pp. 299 –328). New York, NY: Wiley. 567 Brown, S. D., & Lent, R. W. (1996). A social cognitive framework for career choice counseling. Career Development Quarterly, 44, 354 –366. doi:10.1002/j.2161-0045.1996.tb00451.x Brown, S. D., Tramayne, S., Hoxha, D., Telander, K., Fan, X., & Lent, R. W. (2008). Social cognitive predictors of college students’ academic performance and persistence: A meta-analytic path analysis. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 72, 298 –308. doi:10.1016/j.jvb.2007.09.003 Byars-Winston, A., Estrada, Y., Howard, C., Davis, D., & Zalapa, J. (2010). Influence of social cognitive and ethnic variables on academic goals of underrepresented students in science and engineering: A multiple-groups analysis. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 57, 205– 218. doi:10.1037/a0018608 Cantor, N., & Sanderson, C. A. (1999). Life task participation and wellbeing: The importance of taking part in daily life. In D. Kahneman, E. Diener, & N. Schwarz (Eds.), Well-being: The foundations of hedonic psychology (pp. 230 –243). New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation. Carter, M. A. T., & Cook, K. (1995). Adaptation to retirement: Role changes and psychological resources. Career Development Quarterly, 44, 67– 82. doi:10.1002/j.2161-0045.1995.tb00530.x Choi, B. Y., Park, H., Yang, E., Lee, S. K., Lee, Y., & Lee, S. M. (2012). Understanding career decision self-efficacy: A meta-analytic approach. Journal of Career Development, 39, 443– 460. doi:10.1177/ 0894845311398042 Cinamon, R. G. (2006). Anticipated work-family conflict: Effects of gender, self-efficacy, and family background. The Career Development Quarterly, 54, 202–215. doi:10.1002/j.2161-0045.2006.tb00152.x Colquitt, J. A., LePine, J. A., & Noe, R. A. (2000). Toward an integrative theory of training motivation: A meta-analytic path analysis of 20 years of research. Journal of Applied Psychology, 85, 678 –707. doi:10.1037/ 0021-9010.85.5.678 Côté, S., Saks, A. M., & Zikic, J. (2006). Trait affect and job search outcomes. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 68, 233–252. doi:10.1016/j .jvb.2005.08.001 Creed, P. A., Fallon, T., & Hood, M. (2009). The relationship between career adaptability, person and situation variables, and career concerns in young adults. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 74, 219 –229. doi:10.1016/j.jvb.2008.12.004 Creed, P., Patton, W., & Prideau, L. (2006). Causal relationship between career indecision and career decision-making self-efficacy: A longitudinal cross-lagged analysis. Journal of Career Development, 33, 47– 65. doi:10.1177/0894845306289535 Fabian, E. S. (2000). Social cognitive theory of careers and individuals with serious mental health disorders: Implications for psychiatric rehabilitation programs. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 23, 262–269. doi:10.1037/h0095159 Griffin, B., & Hesketh, B. (2005). Counseling for work adjustment. In S. D. Brown & R. W. Lent (Eds.), Career development and counseling: Putting theory and research to work (pp. 483–505). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley. Gushue, G. V., Clarke, C. P., Pantzer, K. M., & Scanlan, K. R. L. (2006). Self-efficacy, perceptions of barriers, vocational identity, and the career exploration behavior of Latino/a high school students. Career Development Quarterly, 54, 307–317. doi:10.1002/j.2161-0045.2006.tb00196.x Hackett, G., & Betz, N. E. (1981). A self-efficacy approach to the career development of women. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 18, 326 –339. doi:10.1016/0001-8791(81)90019-1 Hackett, G., Betz, N. E., & Doty, M. S. (1985). The development of a taxonomy of career competencies for professional women. Sex Roles, 12, 393– 409. doi:10.1007/BF00287604 Holland, J. L. (1997). Making vocational choices: A theory of vocational personalities and work environments (3rd ed.). Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources. Huang, J.-T., & Hsieh, H.-H. (2011). Linking socioeconomic status to social cognitive career theory factors: A partial least squares path mod- This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers. This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly. 568 LENT AND BROWN eling analysis. Journal of Career Assessment, 19, 452– 461. doi:10.1177/ 1069072711409723 Jome, L. M., & Phillips, S. D. (2013). Interventions to aid job finding and choice implementation. In S. D. Brown and R. W. Lent (Eds.), Career development and counseling: Putting theory and research to work (2nd ed., pp. 595– 620). New York, NY: Wiley. Kanfer, R., Wanberg, C. R., & Kantrowitz, T. M. (2001). Job search and employment: A personality-motivational analysis and meta-analytic review. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86, 837– 855. doi:10.1037/00219010.86.5.837 King, Z. (2004). Career self-management: Its nature, causes and consequences. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 65, 112–133. doi:10.1016/ S0001-8791(03)00052-6 Lent, R. W. (2004). Toward a unifying theoretical and practical perspective on well-being and psychological adjustment. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 51, 482–509. doi:10.1037/0022-0167.51.4.482 Lent, R. W. (2013a). Career-life preparedness: Revisiting career planning and adjustment in the new workplace. Career Development Quarterly, 61, 2–14. doi:10.1002/j.2161-0045.2013.00031.x Lent, R. W. (2013b). Social cognitive career theory. In S. D. Brown & R. W. Lent (Eds.), Career development and counseling: Putting theory and research to work (2nd ed., pp. 115–146). New York, NY: Wiley. Lent, R. W., & Brown, S. D. (2006). Integrating person and situation perspectives on work satisfaction: A social-cognitive view. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 69, 236 –247. doi:10.1016/j.jvb.2006.02.006 Lent, R. W., & Brown, S. D. (2008). Social cognitive career theory and subjective well-being in the context of work. Journal of Career Assessment, 16, 6 –21. doi:10.1177/1069072707305769 Lent, R. W., & Brown, S. D. (2013). Understanding and facilitating career development in the 21st century. In S. D. Brown & R. W. Lent (Eds.), Career development and counseling: Putting theory and research to work (2nd ed., pp. 1–26). New York, NY: Wiley. Lent, R. W., Brown, S. D., & Hackett, G. (1994). Toward a unifying social cognitive theory of career and academic interest, choice, and performance [Monograph]. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 45, 79 –122. doi: 10.1006/jvbe.1994.1027 Lent, R. W., Brown, S. D., & Hackett, G. (2000). Contextual supports and barriers to career choice: A social cognitive analysis. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 47, 36 – 49. doi:10.1037/0022-0167.47.1.36 Lent, R. W., & Fouad, N. A. (2011). The self as agent in social cognitive career theory. In P. J. Hartung & L. M. Subich (Eds.), Developing self in work and career: Concepts, cases, and contexts (pp. 71– 87). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. Lent, R. W., Hackett, G., & Brown, S. D. (1999). A social cognitive view of school-to-work transition. The Career Development Quarterly, 47, 297–311. doi:10.1002/j.2161-0045.1999.tb00739.x Lent, R. W., & Sheu, H. (2010). Applying social cognitive career theory across cultures: Empirical status. In J. G. Ponterotto, J. M. Casas, L. A. Suzuki, & C. M. Alexander, (Eds.), Handbook of multicultural counseling (3rd ed., pp. 691–701). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Lent, R. W., Taveira, M., & Lobo, C. (2012). Two tests of the social cognitive model of well-being in Portuguese college students. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 80, 362–371. doi:10.1016/j.jvb.2011.08.009 Lidderdale, M. A., Croteau, J. M., Anderson, M. Z., Tovar-Murray, D., & Davis, J. M. (2007). Building lesbian, gay, and bisexual vocational psychology: A theoretical model of workplace sexual identity management. In K. J. Bieschke, R. M. Perez, & K. A. DeBord (Eds.), Handbook of counseling and psychotherapy with lesbian, gay, and bisexual clients (pp. 245–270). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. doi:10.1037/11482-010 Morrow, S. L., Gore, P. A., & Campbell, B. W. (1996). The application of a sociocognitive framework to the career development of lesbian women and gay men. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 48, 136 –148. doi:10.1006/jvbe.1996.0014 Ojeda, L., Flores, L. Y., & Navarro, R. L. (2011). Social cognitive predictors of Mexican American college students’ academic and life satisfaction. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 58, 61–71. doi:10.1037/a0021687 Rogers, M. E., & Creed, P. A. (2011). A longitudinal examination of adolescent career planning and exploration using a social cognitive career theory framework. Journal of Adolescence, 34, 163–172. doi:10.1016/j.adolescence.2009.12.010 Rogers, M. E., Creed, P. A., & Glendon, A. I. (2008). The role of personality in adolescent career planning and exploration: A social cognitive perspective. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 73, 132–142. doi:10.1016/j.jvb.2008.02.002 Rottinghaus, P. J., Day, S. X., & Borgen, F. H. (2005). The Career Futures Inventory: A measure of career-related adaptability and optimism. Journal of Career Assessment, 13, 3–24. doi:10.1177/1069072704270271 Sadri, G. (1996). A study of agentic self-efficacy and agentic competence across Britain and the USA. Journal of Management Development, 15, 51– 61. doi:10.1108/02621719610107818 Saks, A. M. (2006). Multiple predictors and criteria of job search success. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 68, 400–415. doi:10.1016/j.jvb.2005.10.001 Saks, A. M., & Ashforth, B. E. (1999). Effects of individual differences and job search behaviors on the employment status of recent university graduates. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 54, 335–349. doi:10.1006/ jvbe.1998.1665 Savickas, M. L. (1997). Career adaptability: An integrative construct for life-span, life-space theory. The Career Development Quarterly, 45, 247–259. doi:10.1002/j.2161-0045.1997.tb00469.x Savickas, M. L. (2013). Career construction theory and practice. In S. D. Brown & R. W. Lent (Eds.), Career development and counseling: Putting theory and research to work (2nd ed., pp. 147–183). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley. Sheu, H., Lent, R. W., Brown, S. D., Miller, M. J., Hennessy, K. D., & Duffy, R. D. (2010). Testing the choice model of social cognitive career theory across Holland themes: A meta-analytic path analysis. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 76, 252–264. doi:10.1016/j.jvb.2009.10.015 Solberg, V. S., Good, G. E., Fischer, A. R., Brown, S. D., & Nord, D. (1995). Career decision-making and career search activities: Relative effects of career search self-efficacy and human agency. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 42, 448 – 455. doi:10.1037/0022-0167.42.4.448 Solberg, V. S., Good, G. E., Nord, D., Holm, C., Hohner, R., Zima, N., . . . Malen, A. (1994). Assessing career search expectations: Development and validation of the Career Search Efficacy Scale. Journal of Career Assessment, 2, 111–123. doi:10.1177/106907279400200202 Super, D. E., Savickas, M. L., & Super, C. M. (1996). The life-span, life-space approach to careers. In D. Brown, L. Brooks, & Associate (Eds.), Career choice and development: Applying contemporary theories to practice (3rd ed., pp. 121–178). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. Todd, S. Y., & Kent, A. (2006). Direct and indirect effects of task characteristics on organizational citizenship behavior. North American Journal of Psychology, 8, 253–268. Turner, S. L., & Lapan, R. T. (2013). Promotion of career awareness, development, and school success in children and adolescents. In S. D. Brown & R. W. Lent (Eds.), Career development and counseling: Putting theory and research to work (2nd ed., pp. 539–564). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley. Zikic, J., & Saks, A. M. (2009). Job search and social cognitive theory: The role of career-relevant activities. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 74, 117–127. doi:10.1016/j.jvb.2008.11.001 Received November 10, 2012 Revision received April 29, 2013 Accepted May 10, 2013 䡲

Anuncio

Documentos relacionados

Descargar

Anuncio

Añadir este documento a la recogida (s)

Puede agregar este documento a su colección de estudio (s)

Iniciar sesión Disponible sólo para usuarios autorizadosAñadir a este documento guardado

Puede agregar este documento a su lista guardada

Iniciar sesión Disponible sólo para usuarios autorizados