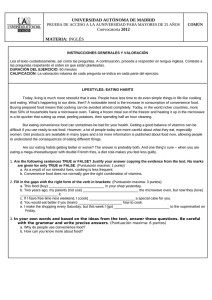

Eating and Weight Disorders - Studies on Anorexia, Bulimia and Obesity https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-020-00846-2 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Integrated weight loss and cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) for the treatment of recurrent binge eating and high body mass index: a randomized controlled trial Marly Amorim Palavras1,2 · Phillipa Hay2 · Haider Mannan2 Stephen Touyz3,5 · Angélica M. Claudino1 · Felipe Q. da Luz3,4 · Amanda Sainsbury3 · Received: 29 October 2019 / Accepted: 8 January 2020 © Springer Nature Switzerland AG 2020 Abstract Purpose The association between binge eating and obesity is increasing. Treatments for disorders of recurrent binge eating comorbid with obesity reduce eating disorder (ED) symptoms, but not weight. This study investigated the efficacy and safety of introducing a weight loss intervention to the treatment of people with disorders of recurrent binge eating and a high body mass index (BMI). Methods A single-blind randomized controlled trial selected adults with binge eating disorder or bulimia nervosa and BMI ≥ 27 to < 40 kg/m2. The primary outcome was sustained weight loss at 12-month follow-up. Secondary outcomes included ED symptoms. Mixed effects models analyses were conducted using multiple imputed datasets in the presence of missing data. Results Ninety-eight participants were randomized to the Health Approach to Weight Management and Food in Eating Disorders (HAPIFED) or to the Cognitive Behavioural Therapy-Enhanced (CBT-E). No between-group differences were found for percentage of participants achieving weight loss or secondary outcomes, except for reduction of purging behaviour, which was greater with HAPIFED (p = 0.016). Binge remission rates specifically at 12-month follow-up favoured HAPIFED (34.0% vs 16.7%; p = 0.049). Overall, significant improvements in the reduction of ED symptoms were seen in both groups and these were sustained at the 12-month follow-up. Conclusion HAPIFED was not superior to CBT-E in promoting clinically significant weight loss and was not significantly different in reducing most ED symptoms. No harm was observed with HAPIFED, in that no worsening of ED symptoms was observed. Further studies should test approaches that target both the management of ED symptoms and the high BMI. Level of evidence Level I, randomized controlled trial Trial registration US National Institutes of Health clinical trial registration number NCT02464345, date of registration 1 June 2015. Keywords Binge-eating disorder · Bulimia nervosa · Therapy · Weight loss * Marly Amorim Palavras [email protected] 1 Eating Disorders Program (PROATA), Department of Psychiatry, Universidade Federal de São Paulo (UNIFESP), Rua Major Maragliano 241, São Paulo, SP 04017‑030, Brazil 2 School of Medicine, Translational Health Research Institute, Western Sydney University, 1797 Locked Bag Avenue, Sydney 2751, Australia 3 Boden Collaboration for Obesity, Nutrition, Exercise and Eating Disorders, Faculty of Medicine and Health, Charles Perkins Centre, The University of Sydney, Sydney 2006, Australia 4 Eating Disorders Program (AMBULIM), Faculty of Medicine, Universidade de São Paulo (USP), Rua Dr. Ovidio Pires de Campos, 785, São Paulo, SP 05403‑010, Brazil 5 School of Psychology, Faculty of Science, The University of Sydney, Sydney 2006, Australia 13 Vol.:(0123456789) Eating and Weight Disorders - Studies on Anorexia, Bulimia and Obesity Introduction Around 40% of people in the community with eating disorders (EDs) characterized by recurrent binge eating, specifically bulimia nervosa (BN) or binge eating disorder (BED), have a high body mass index (BMI; kg/m2) [1].This comorbidity is increasing faster than either problem alone. Darby et al. [2] have reported that, from 1995 to 2005 in Australia, the increase in prevalence of people with ED behaviours comorbid with obesity is significantly higher (4.5 times) than either the increase in prevalence of people with obesity alone (1.6 times), or with ED behaviours without obesity (3.1 times). The combination of an ED with obesity shows greater mental health impact as demonstrated in an observational study in a clinical sample of women that compared four groups—obese + BN, obese + BED, obese without ED and normal weight controls. The authors reported more severity for binge eating frequency, depressive and anxiety traits, drive for thinness, body dissatisfaction, harm avoidance and self-directedness for the obese + BN group, followed by the obese + BED group, when compared with the other two groups [3]. In a study comparing group-based cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) to CBT delivered online, Bulik et al. (2012) identified that 30% of participants with BN were overweight. Because of an observed trend of high BMI in this sample, these authors highlighted the need to include weight management in new approaches for this disorder [4]. In a systematic review of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) reporting psychological treatment for people with BN or BED comorbid to overweight/obesity, no study including people with BN associated with high BMI was found [5]. Systematic and qualitative reviews reinforce that psychological approaches do not promote weight loss in people with BED [6–8]. Treatment for individuals with BN or BED comorbid with a high BMI is, however, problematic because the approaches used for weight loss generally do not focus on the presence of binge eating and its related psychological symptoms [9, 10], and, on the other hand, psychological treatments for EDs are ineffective in promoting weight loss [5–8]. The efficacy of psychological therapies treating the association between weight loss and binge eating in adults with EDs comorbid with high BMI was evaluated through a systematic review of RCTs, and CBT was the most consistently tested intervention [5]. CBT reduced binge eating frequency, but not BMI when compared with the wait list. For the same variables (weight loss and binge eating reduction), CBT was not superior compared with active interventions, e.g., interpersonal psychotherapy [11]. The meta-analyses showed superiority for CBT versus behavioural weight loss therapy (BWLT) related to binge eating reduction at the end of treatment, but not at 12-month follow-up [5]. 13 A manualized therapy named a Healthy Approach to Weight Management and Food in Eating Disorders (HAPIFED) has been since developed [12]. Originally, a pilot study tested this new intervention in a 20-session group format with 11 participants receiving the therapy. At the end of treatment, six participants had reduction of body weight (range − 1.1 to − 6.0%) and decreased EDs symptoms (measured by the Eating Disorder Examination-Questionnaire) [12]. HAPIFED combines the main features of CBT-Enhanced (CBT-E) [13] with BWLT that are effective for binge eating reduction and weight loss in BED [14]. Its aim is a modest weight loss goal of 5% of body weight that may yet improve physical and metabolic health status [15]. In addition, self-awareness of hunger, internal appetite regulation and satiety cues are highlighted when treating these conditions and have greater emphasis compared to external regulation of food intake, an approach suggested by Bulik et al. [4] and Sainsbury-Salis [16]. Compared with CBTE, HAPIFED provides more psychoeducation about a high BMI including its risks, nutritional counselling, self-monitoring of appetite regulation, promotion of physical exercise and the management of behavioural activation of daily routine activities that increase energy expenditure. HAPIFED also requires the participation of a multidisciplinary team. An important feature of HAPIFED is the longer number of sessions (30) and treatment period (over 6 months), i.e. one-third more sessions and 2 months longer duration than CBT-E [13]. It may allow more time for patients to make the necessary behavioural changes to reduce disordered eating and weight. The aim of this study was to examine the efficacy and safety of introducing weight loss management in the treatment of people with disorders of recurrent binge eating and a high BMI. The primary hypothesis of this RCT was that, at the end of treatment, 6-month and 12-month follow-ups, the participants receiving HAPIFED would have lost more body weight than those receiving CBT-E. In addition, it was hypothesized that individuals who achieved binge eating remission would have a greater degree of weight loss than those with continuing binge eating, regardless of intervention type. Safety was investigated in regards to concerns that BWLT may worsen ED symptoms and comparing outcomes of both groups on levels of EDs symptoms, i.e. binge eating, purging behaviours or any compensatory method, restraint and eating, weight and shape concerns. Methods This paper reports weight loss as the primary outcome and ED psychopathology as the secondary outcome. Other secondary outcomes stated in clinicaltrials.gov (registration Eating and Weight Disorders - Studies on Anorexia, Bulimia and Obesity number NCT02464345) will be provided in a subsequent publication. Design This was a single blind, two-arm RCT conducted at the Eating Disorders Program (PROATA) of the Department of Psychiatry of the Universidade Federal de São Paulo (UNIFESP), Brazil. Participants Participants were recruited from July 2015 to November 2017 through the Eating Disorders Program waiting list, advertisements in radio and printed media and printed notices. Participants were included if they were aged ≥ 18 years, fulfilled the primary threshold or subthreshold criteria for diagnosis of BED or BN according to DSM-5 [17] and/or the proposed ICD-11 criteria [18] and had a BMI ≥ 27 kg/m2 and < 40 kg/m2. The main exclusion criteria were the presence of severe mental disorders, current use of weight loss medication, history of bariatric surgery, clinical conditions that interfere with appetite regulation, or current psychological treatment for an ED (For details see Palavras et al. [19]). Sample size The sample size calculation was based on the estimate of a moderate effect size (i.e. 0.6) between groups for the primary outcome (weight loss). To achieve this with a power of 0.8 and alpha = 0.05 (one-tailed test), a minimum of 36 participants per group were required according to Cohen´s tables. Allowing for attrition, the sample size was defined as 50 per treatment arm. Interventions Both treatments comprised an initial individual session followed by a 29 × 90-min group sessions twice weekly for 4 weeks, then weekly thereafter, with a total duration of 6 months. The individual session assessed the participant’s personal history (mainly related to the ED symptoms) and created a personalized formulation of the process that might be contributing to sustained eating problems, in accordance with the CBT-E model [13]. The treatment program, and any concerns the participant might have about it, was also clarified. HAPIFED (experimental intervention) HAPIFED is a multidisciplinary manualized program and its manual has been published [12]. Four conjoint sessions were included, involving dietician and/or an occupational therapist plus the psychological therapists, occurring in the first stage of therapy. Moreover, the treatment included two home visits by the occupational therapist with the purpose of assessing weight-maintaining habits and the domestic environment, proposing changes in the daily routine to favour a better management of food preparation and consumption, and stimulating physical activities. Stage one (sessions 2–11): information about dieting, EDs diagnoses and their main symptoms, high BMI-related health risks, the relevance and role of life events and mood intolerance and other aspects of the CBT-E formulation were presented. The use of real-time self-monitoring of eating and associated behaviours, thoughts, feelings and events was a central component introduced early in the treatment and checked in each session. Regular times for eating, appetite awareness according to internal versus external cues and increased fruit and vegetable intake and exercise in the daily routine were promoted. Stage two (session 12): the CBT-E formulation was revised and discussed. An attempt to identify barriers to change was also checked (fear of change, monitoring, treatment priority, etc.). Stage three (sessions 13–19): promotion of increased activity was continued along with behavioural experiments aimed to reduce EDs behaviours (e.g., binge eating, excessive exercise, compensatory mechanisms) and to establish regular meal patterns and a sense of self-control. Participants were counselled in lifestyle changes that enhance better food choices and increase physical activity patterns. Stage four (sessions 20–27): problem-solving and Socratic questioning were introduced. This stage involved the challenging of unhealthy beliefs and attitudes, which reinforce ED behaviours. Examples are valuing oneself according to one’s weight and shape, and the “all or nothing” type of binary thinking often experienced by people with EDs. Specific emotion regulation skills were taught to address mood intolerance. Stage five (sessions 28–30): similar to the final stage of CBT, this was a preparation for relapse prevention and review of successful cognitive and behavioural strategies. At the end of therapy, the goal was achieving a regular pattern of eating a varied and appetizing diet with mild to modest energy restriction. EDs behaviours, especially binge eating and self-induced vomiting, should be markedly reduced or absent, and food, eating and weight no longer dominate the person’s self-regard. CBT‑E (control intervention) The control intervention was CBT-E [13], which is based on CBT, the standard leading evidence-based therapy for BN and BED [20–22], here administered in a group format. The CBT-E [13] focus version and its broad version comprise four stages along 20 sessions (when applied to individuals above BMI 17.5 kg/m2). In this study, the broad 13 Eating and Weight Disorders - Studies on Anorexia, Bulimia and Obesity version was used, which included additional topics (clinical perfectionism, low self-esteem and interpersonal problems). It has been extended to 30 sessions offered over 6 months, to match HAPIFED in duration and number of sessions. Stage one (sessions 2–7): aimed to engage the participant in treatment, to create the formulation, to provide psychoeducation and to introduce real-time self-monitoring (as mentioned above in HAPIFED), in-session weighting and regular eating. Stage two (sessions 8–9): progress was reviewed, the formulation was revised and ongoing barriers to change were addressed. Stage three (sessions 10–17): therapy was provided for maintaining mechanisms, such as mood intolerance. Stage four (sessions 18–20): the participant was prepared for therapy end and continued progress beyond the active treatment phase. In the present study, four group follow-up sessions over the subsequent 6 months were provided for both interventions. The same psychologists who led the group sessions also conducted these subsequent sessions of 6-month and 12-month follow-ups. The purpose was to address relapses/ lapses, review ongoing progress and facilitate continued improvement. (For more details on both interventions, see Palavras et al. [19]). 1.1 Socio-demographic and clinical self-report questionnaire. 1.2 Objective measure of height and weight. 2. For psychiatric diagnoses evaluation: 2.1 Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview– MINI [23]. 3. For ED diagnoses and symptomatology: 3.1 The Eating Disorder Examination (EDE) interview—Edition 17.0D [24]. Cronbach’s α for the global score in this sample was 0.77 (22 items). Evaluation of binge eating frequency and the presence of compensatory methods were based on the EDE specific questions. 3.2 The Loss of Control over Eating Scale (LOCES) [25]. Cronbach’s α for the current sample was 0.92 (24 items). Treatment integrity: evaluation of blindness integrity in the trial was checked at the end of treatment and it was conducted by asking participants to guess which group, experimental or control, they thought they were in. Assessment Outcomes After a brief screening by telephone or email to check eligibility (n = 589), 191 participants were invited for in-person interview. First, the study was further explained, eligibility criteria was double checked and informed consent was obtained. Then a medical history was undertaken and height and weight were obtained. Additionally, a semi-structured interview to access psychiatric disorders’ diagnosis (including EDs) and self-report questionnaires were applied to evaluate the presence and severity of the prospective participant’s ED. All measurements were collected after the informed consent was signed. In a second visit, a semi-structured interview was conducted to confirm the EDs diagnosis and to obtain detailed information on ED psychopathology and behaviours. Assessments occurred at baseline, mid and end therapy, and 6- and 12-month follow-ups and were conducted on all participants who agreed to complete evaluations, including those who withdrew before the end of treatment. All instruments used in this study have satisfactory psychometric properties as detailed in the previously published protocol [19]. The final assessment occurred in March 2019 when the length of 12-month follow-up was achieved. The instruments used to collect the measures of this study were: The primary outcome of this intervention was a reduced body weight sustained to 12 months after completion of the intervention, considering the percentage of total body weight loss and the percentage of participants presenting a weight loss ≥ 5% of baseline measure. ED symptoms were secondary outcomes. 1. For socio-demographic and clinical measures: 13 Randomization, masking and protection against bias Randomization was conducted in blocks of 20, with participants randomized in a 1:1 ratio to either a HAPIFED or CBT-E group with up to ten participants per group. An investigator external to the site (PH) administered the allocation using a computer-generated sequence facilitated by the sealed envelope website (www.sealedenvelope.com). The therapists and therapy supervisors had access to the allocation of participants, but the individuals randomized were blind to the treatment group. The allocation of participants occurred after the first individual session, which was similar for both interventions. To maintain blinding, no handouts or written material given to participants during the intervention identified the name of the treatment (e.g. by referring to the original therapy manual). Assessors collecting outcome data were blind to participant’s treatment arm, with the exception of one assessor (the dietitian) who performed Eating and Weight Disorders - Studies on Anorexia, Bulimia and Obesity anthropometric measurements. A statistician blind to treatment arms conducted the outcome analyses only after the final, 12-month follow-up. Treatment fidelity Therapies were guided in accordance with their treatment manuals. Four therapists trained in both therapies conducted the treatments. Each group of two therapists provided CBT-E and HAPIFED in turn to control for non-specific therapists’ effect. In preparation for this RCT, therapists experienced with CBT-E and HAPIFED (PH, Jessica Swinbourne) trained all therapists (psychologists, occupational therapist and dietitian) and conducted monthly telephone supervision sessions during two pilot therapy groups, one for HAPIFED and one for CBT-E (August 2014 to February 2015). PH provided regular supervision throughout the trial, with additional specialist supervision by AS, who has expertise in appetite regulation and other specific approaches to weight management. Moreover, PH visited Brazil twice a year for 3 years for face-to-face supervision of the Brazilian team. In addition, an onsite Brazilian therapist, CM, had undergone the Oxford CBT-E online training. During the RCT, another author (FQdL) conducted regular qualitative appraisals of a random sample of de-identified digitally recorded audiotaped sessions to assess for and promote fidelity to the manual. Statistical analyses Baseline univariate between-group tests were done to compare groups on outcome variables, as well as clinical and demographic data. For univariate analysis, the Chi-squared test or Fisher´s exact test was used to assess the association between the categorical dependent variable and treatment versus control groups. Two independent sample t tests were performed to compare the means for between the treatment and control groups when the outcomes followed a normal distribution. Linear mixed effects modelling, Poisson mixed and logistic mixed models [26] were used to test between-group differences for continuous, counting and binary outcome measures, respectively. The overall effects of group, time and time by group interactions were tested by likelihood ratio Chi-squared tests. Whenever statistically significant time or time by group interactions were found, multiple comparisons using Bonferroni correction were conducted to identify distinct groups of means or proportions. Mixed effects linear model assumed a normal distribution. This assumption was verified using Kolmogorov–Smirnov normality test. Effect sizes between the treatment and control groups for a continuous or a count outcome variable were estimated using Cohen’s d, with small, moderate and large effect sizes being defined as 0.20–0.49, 0.50–0.79 and 0.80–1.00, respectively [27]. For categorical outcome variables, odds ratios were calculated, with small, moderate and large effect sizes being defined as 1.52, 2.74 and 4.72, respectively [28]. The confidence intervals for Cohen’s d were estimated using non-central t distributions when the outcome variables for the two groups were normally distributed. All 95% confidence intervals were corrected for multiplicity using the Bonferroni method. Data were analysed following “intention-to-treat” principles. To perform all statistical analysis in the presence of missing data, multiple imputed datasets were used based on multivariate normal (numerical variables) or (dichotomous variables) imputation with Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) algorithm [29]. For this trial, 15 imputations were performed. Finally, the results were pooled using Rubin’s rules [30]. Statistical analyses were performed using STATA 15 [31], with a small number of analyses (i.e. for baseline socio-demographic and clinical features) being performed using SPSS version 20 for Windows [32]. Results Participants Ninety-eight participants were randomized to enter the trial. Fifty participants were allocated in the experimental intervention group (HAPIFED) and 48 in the control intervention group (CBT-E). Dropout rates along the study time points for the total sample (N = 98) were: 31.6%, 48.0% and 36.7% for end of treatment, 6-month follow-up and 12-month follow-up, respectively. Attrition did not differ between groups along the stages of the trial. Figure 1 outlines the participant’s flowchart diagram. This sample consisted mainly of women (96%) who were white (75%) and employed (60%). Almost half of the participants were married (45%) and had completed a tertiary degree (43%). The mean age was 41 (SD 11.7) years, and the mean BMI was 33.68 (SD 3.31) kg/m2. The most prevalent psychiatric comorbidities among participants were major depressive episodes (32%) and generalized anxiety disorder (47%). Thirty-four percent of the participants were taking medication for diabetes mellitus and 12% were on psychotropic/antidepressant medication. Sixty-six (67.3%) participants met the DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for BED and 13 (13.3%) for BN. Of the remaining 19 participants, 5 (5.1%) had other specified feeding or eating disorder (OSFED) BED-type, 7 (7.1%) had OSFEDBN type and 7 (7.1%) unspecified feeding or eating disorder (UFED). Of those receiving UFED diagnosis, all reported regular recurrent binge eating, but five did not fulfil Criterion B or C for BED, one with recurrent binge eating and 13 Eating and Weight Disorders - Studies on Anorexia, Bulimia and Obesity Assessed for eligibility (n = 589) Randomized (n = 98) Allocated to HAPIFED group (n = 50) Received allocated intervention (n = 46) Did not receive allocated intervention (n = 4) Got sick (n = 2) Got a job (n = 2) Excluded (n = 491) Declined (n = 266) Not meeting selection criteria (n =190) Other reasons (n = 35) Allocated to CBT-E group (n = 48) Received allocated intervention (n = 44) Did not receive allocated intervention (n = 4) No interest (n = 2) Got a job (n = 2) Middle of treatment Assessed (n = 42) Discontinued intervention (n = 4) Lost to follow-up (n = 4) Middle of treatment Assessed (n = 35) Discontinued intervention (n = 5) Lost to follow-up (n = 8) End of treatment Assessed (n = 37) Discontinued intervention (n = 8) Lost to follow-up (n = 5) End of treatment Assessed (n = 30) Discontinued intervention (n = 10) Lost to follow-up (n = 8) Follow-up 6 months Assessed (n = 28) Discontinued intervention (n = 10) Lost to follow-up (n = 12) Follow-up 6 months Assessed (n = 23) Discontinued intervention (n = 12) Lost to follow-up (n = 13) Follow-up 12 months Assessed (n = 31) Discontinued intervention (n = 7) Lost to follow-up (n = 12) Follow-up 12 months Assessed (n = 31) Discontinued intervention (n = 6) Lost to follow-up (n = 11) Analysed (n = 50) Analysed (n = 48) Excluded from analysis (n = 0) Excluded from analysis (n = 0) Fig. 1 Participant flowchart 13 E n r o l l m e n t A l l o c a t i o n F o l l o w u p A n a l y s i s Eating and Weight Disorders - Studies on Anorexia, Bulimia and Obesity self-induced vomiting episodes did not meet Criterion D for BN, and one met all criteria for BN, but only reported subjective binge eating. As shown in Table 1, treatment groups did not differ at baseline in any socio-demographic or clinical features, with the exception of the EDE restraint subscale (p = 0.042), for which the HAPIFED group showed a higher level of eating restraint behaviours. Outcomes The outcome findings are summarized in Table 2 and all participants (n = 98) were analysed by original assigned groups in all outcome measures. Primary outcome: weight loss No differences were found for between-group comparisons in weight loss measures, in the percentage of total body weight loss (χ2(3) = 0.19, p = 0.979) or in the percentage of participants presenting a weight loss ≥ 5% of baseline weight (χ2(3) = 0.22, p = 0.974). A time effect was found for ≥ 5% body weight loss measures from baseline to end of treatment (using Bonferroni-adjusted correction for multiple comparisons), which was sustained across the 6- and 12-month follow-up (χ2(3) = 9.06, p = 0.029). At 12-month follow-up, 20.5% of participants in the HAPIFED group and 21.9% in the CBT-E group achieved ≥ 5% of body weight loss (Table 2). Secondary outcomes Binge eating Although no differences were found for between-group comparisons for the frequency of objective binge eating (OBE) and subjective binge eating (SBE), a time effect was observed for both types of binge eating (p < 0.001). The mean OBE frequency decreased from baseline to end of treatment and was sustained in subsequent time points in both groups. For SBE, the mean frequency also decreased from baseline to end of treatment and did not change until the 6-month follow-up, but increased in the 12-month follow-up, as shown in Table 2. Complete abstinence from any type of binge eating was considered for the definition of the variable binge eating remission. No difference in between-group comparisons was found in the group x time interaction analysis. However, a post hoc analysis revealed that, specifically at the 12-month follow-up, a greater percentage of individuals (34.0% versus 16.7%) achieved binge eating remission in the HAPIFED group (χ 2(1) = 3.97, p = 0.049). In addition, binge eating remission was not associated with greater reduction of weight at any time point of the study in the whole sample (end of treatment: p = 0.654; 6-month follow-up: p = 0.528; 12-month follow-up: p = 0.589). ED behaviours and psychopathology As EDE restraint differed between groups at baseline (group x time interaction: χ2(3) = 7.90, p = 0.048), an adjusted analysis of this outcome using the EDE restraint subscale as a covariable in the model was conducted, but results did not alter previous findings (χ2(1) = 2.47, p = 0.116). No differences were observed for the presence of “any” type of compensatory behaviour between groups at any time point, but a greater reduction of any “purging” behaviour (group x time interaction: χ 2(3) = 10.35, p = 0.016) was found favouring HAPIFED. The percentage of any purging behaviour between groups was higher (18.8%) in CBT-E than in HAPIFED (6.0%) at the 6-month follow-up (Wald χ 2(1) = 9.321, p = 0.002), but not different at other time points (Wald χ2(2) = 3.21, p = 0.201). Group x time interaction analyses did not find betweengroup differences for any measure of ED psychopathology as measured with the EDE subscales and LOCES, although a trend favouring HAPIFED was observed for EDE global score (p = 0.051) and EDE weight concern subscale (p = 0.054). Bonferroni-adjusted comparisons for time effect showed significant differences for restraint, as well as for concerns about eating, shape and weight, which decreased in severity from baseline to end of treatment, stabilizing over the follow-up period (p < 0.001). Loss of control over eating (LOCES scores) significantly decreased from baseline until the 12-month follow-up (p < 0.001). A further outcome was achieving a global EDE score ≤ one standard deviation of the community mean (EDE global score cutoff = 1.737) [13]. A time effect was observed for the reduction in the percentage of individuals remaining above one standard deviation of EDE global mean. At the end of treatment, 61.5% (HAPIFED group) and 58.6% (CBT-E group) achieved a global EDE global score ≤ 1.737, and for 12-month follow-up, the values were 67.7% and 52.5%, respectively. Protocol integrity and blinding Protocol violations (antidepressant prescription) occurred in seven participants due to worsening of depressive symptoms (3.3% CBT-E versus 16.2% HAPIFED; p = 0.120). Participant blinding was examined at the end of treatment questionnaires, and of the 65 who replied to this question, 55.4% (36/65) chose the correct treatment allocation. This was equally distributed between groups (p = 0.140). 13 Eating and Weight Disorders - Studies on Anorexia, Bulimia and Obesity Table 1 Baseline sociodemographic and clinical features of treatment groups (n = 98) Gender, female Ethnicity White/Caucasian Black/African/Asian* Marital status Married Single Divorced/widowed Educational level Completed middle school Completed high school Completed undergraduation Completed postgraduation Current occupation Employed Not employed Student Housewife Presence of current major depressive episodes Presence of any current anxiety disorder Use of psychotropic medication Use of diabetes medication DSM-5 diagnoses Binge eating disorder Bulimia nervosa OSFED UFED Presence of any purging behaviour Presence of any compensatory behaviour Age, years Weight, kg Body mass index (kg/m2) Eating disorder illness duration EDE global score EDE restraint subscale EDE eating concern subscale EDE shape concern subscale EDE weight concern subscale Loss of Control over Eating Scale Current (3-month) frequency of objective binge eating HAPIFED (n = 50) CBT-E (n = 48) p N (%) 48 (96.0) 46 (96.0) 38 (77.6) 11 (22.4) 35 (74.5) 12 (25.5) 1.000a 0.904c 22 (44.0) 22 (44.0) 6 (12.0) 22 (45.8) 19 (39.6) 7 (14.6) 2 (4.0) 17 (34.0) 24 (48.0) 7 (14.0) 0 (0.0) 21 (43.8) 18 (37.5) 9 (18.8) 30 (60.0) 14 (28.0) 3 (6.0) 3 (6.0) 15 (30.0) 27 (54.0) 7 (14.0) 18 (36.0) 29 (60.4) 14 (29.2) 1 (2.1) 4 (8.3) 16 (33.3) 22 (45.8) 5 (10.4) 15 (31.3) 30 (60.0) 8 (16.0) 8 (16.0) 4 (8.0) 9 (18.0) 16 (32.0) Mean (SD) 40.90 (11.47) 88.96 (11.93) 33.62 (3.19) 15.18 (10.09) 2.72 (0.82) 2.05 (1.24) 1.56 (1.14) 3.78 (1.05) 3.49 (1.02) 3.28 (0.57) 40.10 (30.39) 36 (75.0) 5 (10.4) 4 (8.4) 3 (6.3) 9 (18.8) 9 (18.8) 40.19 (12.05) 89.59 (13.34) 33.74 (3.47) 14.74 (11.56) 2.40 (0.79) 1.58 (0.98) 1.44 (1.19) 3.53 (1.24) 3.08 (1.17) 3.13 (0.66) 38.67 (29.19) 0.940c 0.375c 0.841c 0.723b 0.419b 0.589b 0.619b 0.597c 0.924b 0.132b 0.765b 0.805a 0.854a 0.849a 0.057a 0.042a 0.619a 0.285a 0.068a 0.257a 0.812a CBT-E Cognitive behavioural therapy-enhanced, DSM Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, EDE Eating disorder examination, HAPIFED Health approach to weight management and food in eating disorders, OSFED other specified feeding or eating disorder, UFED unspecified feeding or eating disorder *There was only one Asian participant a 13 T test;bx2test;cFisher’s test HAPIFED CBT-E HAPIFED CBT-E HAPIFED CBT-E HAPIFED CBT-E HAPIFED CBT-E HAPIFED CBT-E HAPIFED EDE weight concern EDE shape concern EDE restraint EDE eating concern Current frequency of OBE last 3 months Current frequency of SBE last 3 months LOCES CBT-E HAPIFED CBT-E EDE global % reduction in HAPbody weight/ IFED kg CBT-E Group 3.13 (0.10) 2.72 (0.12) 2.40 (0.11) 3.49 (0.15) 3.08 (0.17) 3.78 (0.15) 3.53 (0.18) 2.05 (0.18) 1.58 (0.14) 1.56 (0.16) 1.44 (0.17) 40.10 (4.30) 38.67 (4.21) 10.30 (3.48) 10.17 (2.91) 3.28 (0.08) n.a n.a Mean (SE) Baseline Cohen’s d Mean (95% CI) (SE) 1.92 (0.13) 28.55, 3 (< 0.001) 42.79, 3 (< 0.001) 145.25, 3 5.82, 3 (< 0.001) (0.121) 105.07, 3 7.10, 3 (< 0.001) (0.069) 1.14, 1 0.00 ( − 0.40 to (0.286) 0.39) 0.51, 1 0.11 ( − 0.28 to (0.477) 0.51) 0.06, 1 0.23 ( − 0.17 to (0.811) 0.63) 0.00, 1 − 0.04 ( − 0.43 to (0.976) 0.36) (0.13) 32.63, 3 (< 0.001) 1.28, 1 0.22 ( − 0.18 to (0.257) 0.61) (0.15) 34.76, 3 (< 0.001) 3.37, 1 0.26 ( − 0.14 to (0.067) 0.66) 1.23, 1 0.05 ( − 0.35 to (0.268) 0.44) 51.91, 3 (< 0.001) 3.68, 1 0.19 ( − 0.21 to (0.055) 0.58) 305.23, 4 4.29, 4 (< 0.001) (0.368) 3.50, 3 (0.320) 3.75, 3 (0.290) 5.32, 3 (0.150) 7.63, 3 (0.054) 7.76, 3 (0.051) 0.19, 3 (0.979) 1.19, 3 (0.756) 0.02, 1 0.02 ( − 0.38 to (0.896) 0.41) Group × time Chi sq, df (p value) − 0.01 − 0.02 ( − 0.41 to (1.11) 0.38) 0.14 (1.41) 1.42 0.03 ( − 0.36 to (0.16) 0.43) 1.63 (0.16) 1.87 − 0.02 ( − 0.42 to (0.22) 0.38) 2.29 (0.24) 2.42 0.04 ( − 0.36 to (0.21) 0.44) 2.75 (0.22) 0.84 0.00 ( − 0.40 to (0.50) 0.40) 0.82 (0.53) 0.55 0.12 ( − 0.27 to (0.13) 0.52) 0.66 (0.15) 3.98 − 0.04 ( − 0.44 to (2.58) 0.35) 8.32 (2.75) 8.37 0.03 ( − 0.37 to (3.74) 0.42) 7.45 (3.50) 1.69 0.10 ( − 0.29 to (0.11) 0.50) 1.73 Time 0.42 0.03 ( − 0.37 to (1.09) 0.42) 0.28 (1.21) 1.42 − 0.13 ( − 0.53 to (0.14) 0.26) 1.45 (0.16) 1.93 − 0.05 ( − 0.45 to (0.22) 0.34) 1.91 (0.22) 2.60 − 0.02 ( − 0.41 to (0.21) 0.38) 2.66 (0.23) 0.61 − 0.11 ( − 0.50 to (0.50) 0.29) 0.61 (0.57) 0.54 − 0.18 ( − 0.57 to (0.12) 0.22) 0.64 (0.12) 5.07 0.05 ( − 0.34 to (2.18) 0.45) 4.42 (2.10) 0.77 − 0.22 ( − 0.61 to (0.53) 0.18) 0.86 (0.37) 1.89 0.01 ( − 0.38 to (0.15) 0.41) 2.00 Group Cohen’s d Chi sq, df Chi sq, df (95% CI) (p value) (p value) 12-month follow-up Cohen’s d Mean (95% CI) (SE) 6-month follow-up Cohen’s d Mean (95% CI) (SE) End of treatment − 0.22 0.03 ( − 0.37 to (0.78) 0.43) − 0.31 (0.71) − 0.06 (0.88) n.a n.a 1.67 (0.17) n.a 1.52 (0.15) n.a n.a 2.22 (0.19) n.a 2.15 (0.19) n.a n.a 2.71 (0.19) n.a 2.68 (0.20) n.a n.a 0.96 (0.42) n.a 0.65 (0.43) n.a n.a 0.84 (0.18) n.a 0.63 (0.16) n.a n.a 4.85 (2.01) n.a 5.63 (2.35) n.a n.a 5.35 (3.03) n.a 1.34 (2.11) 2.33 0.00 1.91 (0.12) ( − 0.39 to 0.40) (0.13) − 0.45 (0.67) − 0.23 ( − 0.63 to 0.17) 2.34 (0.13) − 0.01 ( − 0.40 to 0.39) − 0.05 ( − 0.44 to 0.35) − 0.10 ( − 0.50 to 0.30) − 0.42 ( − 0.82 to 0.02) − 0.22 ( − 0.61 to 0.18) − 0.37 ( − 0.77 to 0.03) − 0.39 ( − 0.79 to 0.01) n.a Cohen’s d Mean (SE) (95% CI) Middle of treatment Table 2 Outcomes of each group for the total sample using imputation (n = 98 in all analyses, being n = 50 in HAPIFED and n = 48 in CBT-E) and mixed effect models Eating and Weight Disorders - Studies on Anorexia, Bulimia and Obesity 13 13 HAPIFED CBT-E Above 1 standard deviation EDE global score n.a 18.0 (5.4) 18.8 (5.6) 32.0 (6.6) 18.8 (5.6) 90.0 (4.2) 81.3 (5.6) n.a % (SE) Mean (SE) Baseline 2.08 (0.64 to 6.72) 2.04 (0.8 to 5.21) 0.95 (0.34 to 2.64) Odds Ratio (95% CI) n.a n.a n.a n.a n.a n.a 5.7 (4.6) n.a 5.9 (3.8) % (SE) Cohen’s d Mean (SE) (95% CI) n.a n.a n.a 1.15 (0.1 to 12.97) 38.5 (7.5) 0.89 (0.36 to 2.18) 41.4 (7.8) 26.0 (6.2) 2.06 (0.74 to 5.71) 14.6 (5.1) Odds Ratio (95% CI) 12.3 (5.6) 0.79 (0.19 to 3.30) 15.0 (6.3) 12.0 (4.6) 0.80 (0.25 to 2.57) 14.6 (5.1) % (SE) Time 1.57, 1 (0.210) 32.3 (7.6) 0.52 (0.2 to 1.38) 47.5 (8.4) 24.31, 3 (< 0.001) 3.55, 3 (0.314) 2.25, 1 (0.134) 24.0 (6.0) 1.20 (0.46 to 3.11) 20.8 (5.9) 33.2 (8.1) 0.98 (0.37 to 2.63) 33.5 (7.7) 3.25, 3 (0.355) 0.00, 1 (0.961) 22.0 (5.9) 1.22 (0.46 to 3.28) 18.8 (5.6) 9.06, 3 (0.029) 0.05, 1 (0.825) Odds Ratio (95% CI) 20.5 (6.6) 0.92 (0.32 to 2.65) 21.9 (7.2) 8.0 (3.8) 0.43 (0.12 to 1.55) 16.7 (5.4) % (SE) Odds Ratio (95% CI) 17.2 (7.5) 0.73 (0.19 to 2.84) 21.7 (7.0) 6.0 (3.4) 0.28 (0.07 to 1.09) 18.8 (5.6) % (SE) Group Cohen’s d Chi sq, df Chi sq, df (95% CI) (p value) (p value) 12-month follow-up Cohen’s d Mean (95% CI) (SE) 6-month follow-up Cohen’s d Mean (95% CI) (SE) End of treatment Cohen’s d Mean (95% CI) (SE) Odds Ratio (95% CI) Middle of treatment 4.39, 3 (0.222) 6.83, 3 (0.078) 10.35, 3 (0.016) 0.22, 3 (0.974) Group × time Chi sq, df (p value) Presence of any purging behaviour: HAPIFED BL > EoT = 6 M FU = 12 M FU, CBT-E BL = EoT = 6 M FU = 12 M FU, group comparison 6 M FU: A > B, for another time of evaluation there were no differences between groups Bonferroni-adjusted correction for multiple comparisons interaction group × time CBT-E cognitive behavioural therapy – enhanced, EDE Eating Disorder Examination interview, HAPIFED Health Approach to Weight Management and Food in Eating Disorders, LOCES Loss of Control over Eating Scale, OBE objective binge eating episode, SBE subjective binge eating episode HAPIFED CBT-E Presence of any compensatory behaviour Achieved ≥ 5% HAPIFED reduction in body weIght CBT-E HAPPresence of IFED any purging behaviour CBT-E Group Table 2 (continued) Eating and Weight Disorders - Studies on Anorexia, Bulimia and Obesity Eating and Weight Disorders - Studies on Anorexia, Bulimia and Obesity Discussion To our knowledge, this is the first RCT that has tested a new intervention (HAPIFED) examining the efficacy and safety of integrating CBT with weight loss management in the treatment of people with disorders of recurrent binge eating and a high BMI. In this RCT, HAPIFED was not different from CBT-E for measures of weight loss (primary outcome). A greater reduction of purging behaviours was observed in individuals receiving HAPIFED, but only a limited number of participants included in the trial presented this behaviour. Overall, significant reductions were observed in both groups for most primary and secondary outcomes with end of treatment measures, and up to 12-month follow-up (i.e. loss of control over eating). Binge remission was not associated with greater weight loss in this trial. A modest weight loss (≥ 5% of body weight) has been found to show improvements in the medical status of individuals with a high BMI [15]. However, and in line with findings in the literature relative to psychological approaches to BED associated with high BMI [5–8], HAPIFED did not significantly improve weight loss over CBT-E in this trial, with only about 12% of individuals achieving ≥ 5% of baseline weight at the end of treatment, and around 21% at the 12-month follow-up. It is unclear why HAPIFED did not promote weight change at least in the range observed for lifestyle interventions. It is possible that the "dose" of therapy dedicated to weight management in HAPIFED was insufficient to achieve weight loss. In addition, a higher level of impairment due to the combination of EDs with recurrent binge eating and high BMI may have influenced the lack of expected weight loss. Nevertheless, a relevant improvement of the ED psychopathology (EDE and binge eating measures) was achieved from baseline to the end of the active interventions (time effect). The reduction in measures of ED psychopathology is reflected in the finding of reduction in the percentage of participants that presented EDE global scores remaining above one standard deviation of the mean EDE global score (based in community norms) [13] in the course of the study. In other words, many individuals reduced their ED symptoms to levels commonly encountered in the general population, in line with findings of other studies [20, 33, 34]. Systematic reviews support the effectiveness of CBT in promoting binge eating abstinence in people with BED, with rates varying from 22.5% (at the end of treatment and 4-month follow-up) [35], 61% (end of treatment), 58% (12month follow-up) [36] and 52% (4-year follow-up) [37]. For BN, binge abstinence rates tend to be lower in trials testing CBT (and other therapies), being in the range of 12%–50% at the end of treatment and 15% at 1-year follow-up [38]. This study identified apparently lower abstinence rates of binge eating (around 30% at the end of treatment and 34% at the 12-month follow-up for HAPIFED) compared to the literature. However, our measure was based on the frequency of binge eating in the last 3 months, while studies usually report on 15–28 days’ abstinence of binge eating. It is of note that, although both objective and subjective binge eating showed significant reductions in frequency over the course of the study, objective binge eating showed significant reduction during the treatment phase and stabilized during the followups (up to 12 months). Subjective binge eating reduction was maintained only up to 6 months and increased after that. This result may seem contradictory with the finding of continuous improvement and reduction of loss of control over eating (LOCES) score, but this scale reflects loss of control in both types of binges, and all but one individual included in this trial reported objective binge eating. In this RCT, a significantly greater decrease of any purging behaviour favouring HAPIFED was found. Our positive finding was an isolated result that must be considered with caution due to the small number of participants with BN included. However, when taken together with the similar effects obtained with CBT on reduction of ED measures and binge eating reduction, it reinforces the safety of HAPIFED in relation to the introduction of weight management for people with BN and high BMI. In other words, introduction of approaches to healthy eating and weight management did not worsen ED symptoms. The mean dropout rates in this trial were higher at the end of treatment (31.6%) compared to a mean around 24% reported in a recent meta-analysis of RCTs testing CBT for ED [39]. Nonetheless, the authors highlighted the large range of dropout definition in studies. A novelty in this trial is the greater number of sessions (30) offered, aiming to propose a reasonable time for changes in ED behaviours and weight loss. This higher number is supported by Ariel et al. [40], who reported that a higher duration of sessions (from 16 to 24 sessions) in behavioural treatment could promote better results for binge eating severity compared to a smaller duration (8 sessions). However, the authors reported that no additional improvements were observed comparing a high dose (24 sessions) versus a moderate dose (16 sessions) of treatment. Thus, an optimum dose for HAPIFED needs to be reconsidered, as it is possible that the long duration of the treatment influenced the attrition rates. Participants described struggling to meet competing demands of therapy and employment and having paid employment has been reported to increase the risk of attrition [41]. It is known that findings of small effect sizes in the psychology field are common (around 30% of findings are below a Cohen´s d of 0.2) and effects in the 0.05–0.2 range are frequently reported in medical research; however, even small effect sizes may have clinical impact [42]. Our results were mostly of small effect sizes favouring the 13 Eating and Weight Disorders - Studies on Anorexia, Bulimia and Obesity HAPIFED approach; thus, replication in larger samples is needed to clarify the benefits of this new approach. In the future, research approaches to the conjoint conditions of this trial require innovative techniques that can handle the complexity of this combination. New integrative strategies with the goal of targeting both binge remission and weight loss are being developed. Cooper et al. [43] proposed a new model to be tested combining CBT-E and CBT for high BMI for individuals with BED comorbid to high BMI. Pattinson et al. [44] have designed a new prospective study to test the real-world effectiveness of HAPIFED, including people with BED and BN comorbid to high BMI. The strengths of this study are the novelty of introducing an integrative approach that targets ED psychopathology and weight management for people with disorders of recurrent binge eating and a high BMI, which resulted in the improvement (not worsening) of ED symptoms. The participants were blind to group, and an intention-to-treat approach was applied to analyses, reducing risk of bias. Limitations include moderate attrition, a small number of participants with BN, as well as the low number of men, limiting generalizability and precluding subgroup analyses. The lack of a greater effect of HAPIFED on weight loss compared to CBT-E and the moderate attrition support the need of restructuring interventions to better tackle these goals. Finally, this study suggests that this new multidisciplinary psychological approach (HAPIFED) may be used when participants clearly look for help for addressing both ED symptoms and weight problem, or where individuals with BN or BED present in the context of weight loss treatment (e.g. in multidisciplinary metabolic clinics where the primary goal is weight loss management). As a standalone therapy, HAPIFED may need to be extended to enhance its weight loss management strategies, such as firmer emphasis and monitoring of portion sizes. HAPIFED, in the modified form, may also be appropriate for people at risk of recurrent binge eating relapse, where the goal is weight loss maintenance following a weight loss treatment. What is already known on this subject? Over half of the people with BN and/or BED are of a high BMI. To our knowledge, however, no study has tested as yet a psychological approach that integrates the management of weight and recurrent binge eating in individuals with these EDs and a high BMI, especially for people with bulimia nervosa. 13 What does this study add? This study suggests that this new approach (HAPIFED) integrating the expertise of an interconnected and multidisciplinary team of professionals can safely treat weight and EDs behaviours (e.g. recurrent binge eating) in a group format, joining individuals with BN and BED (a transdiagnostic approach) and high BMI. The reduction of binge eating and improvement of other related ED symptoms were comparable to those observed with CBT, the intervention with greater evidence of efficacy in the field. The progress of research focused on the improvement of techniques that can safely and effectively manage this specific combination (BN or BED and high BMI) may help reduce the burden of the growing number of people affected by both conditions. Conclusion HAPIFED presented good results for the improvement of ED symptomatology in people with disorders of recurrent binge eating associated with high BMI, but did not achieve greater weight loss than CBT-E. Further studies should test approaches that effectively target the management of ED symptoms and high BMI. Acknowledgements The authors acknowledge Jessica Swinbourne who contributed to the HAPIFED manual development, Nara Mendes who contributed to the translation of LOCES and protocol development, Mireille Coelho and Mitti Koyama for the support with different aspects of the trial and the entire team of professionals from PROATA who collaborated with the study execution. Author contributions All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation and data collection were performed by Marly A. Palavras, and analysis was performed by Marly A. Palavras, Haider Mannan, Phillipa Hay and Angélica M. Claudino. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Marly A. Palavras, Phillipa Hay and Angélica M. Claudino. All authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. Funding This study was financed in part by the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior–Brasil (CAPES)–Finance Code 001. PH was part supported by the School of Medicine WSU for travel to Sao Paulo including sabbatical leave in 2012. AS was supported by the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) of Australia via Senior Research Fellowships (1042555 and 1135897) and via a Sydney Outstanding Academic Researcher (SOAR) Fellowship–the University of Sydney. FQdL was supported by The São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP) via a Young Investigator Fellowship. Data availability The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. Eating and Weight Disorders - Studies on Anorexia, Bulimia and Obesity Compliance with ethical standards Conflicts of interest Marly A. Palavras participated in a 2016 meeting of an advisory board for the treatment of binge eating disorder at Shire Pharmaceuticals, Brazil. Phillipa Hay receives/has received sessional fees and lecture fees from the Australian Medical Council, Therapeutic Guidelines publication and New South Wales Institute of Psychiatry; royalties/honoraria from Hogrefe and Huber, McGraw Hill Education, Blackwell Scientific Publications, Biomed Central and PlosMedicine; and has received research grants from the NHMRC and ARC. She is Chair of the National Eating Disorders Collaboration Steering Committee in Australia (2019–) and a Member of the ICD-11 Working Group for Eating Disorders (2012–2018) and was Chair of the Clinical Practice Guidelines Project Working Group (Eating Disorders) of RANZCP (2012–2015). She has received honoraria from Shire Pharmaceuticals for educational seminars for psychiatrists and prepared a commissioned report. Angélica M. Claudino is a member of the World Health Organization Working Group on Feeding and Eating Disorders for the Revision of ICD-10 Mental and Behavioral Disorders. Amanda Sainsbury is the author of The Don’t Go Hungry Diet (Bantam, Australia and New Zealand, 2007) and Don’t Go Hungry for Life (Bantam, Australia and New Zealand, 2011). She has also received payment from Eli Lilly, the Pharmacy Guild of Australia, Novo Nordisk, the Dietitians Association of Australia, Shoalhaven Family Medical Centres, the Pharmaceutical Society of Australia, and Metagenics for presentation at conferences, and served on the Nestlé Health Science Optifast® VLCDTM Advisory Board from 2016 to 2018. Stephen Touyz receives royalties from Hogrefe and Huber, Routledge and McGrawHill Publishers. He has also been the recipient of honoraria and travel and research grants from Shire Pharmaceuticals. He has chaired their Australian Binge-Eating Disorder Advisory Board and has been the author of commissioned reports. All views expressed in these reports have been his own. He is a mental health advisor to the Australian Commonwealth Department of Veterans Affairs and a consultant to Weight Watchers (WW). Haider Mannan and Felipe Quinto da Luz have no conflicts of interest to report. Ethical approval All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. The study was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of UNIFESP (CAAE 43874315.4.0000.5505). Informed consent Informed consent was obtained from all participants included in the study. References 1. Hay P, Girosi F, Mond J (2015) Prevalence and sociodemographic correlates of DSM-5 eating disorders in the Australian population. J Eat Disord 25:3–19. https: //doi.org/10.1186/s40337 -015-0056-0 2. Darby A, Hay P, Mond J, Quirk F, Buttner P, Kennedy L (2009) The rising prevalence of comorbid obesity and eating disorder behaviors from 1995 to 2005. Int J Eat Disord 42:104–108. https ://doi.org/10.1002/eat.20601 3. Villarejo C, Jiménez-Murcia S, Álvarez-Moya E, Granero R, Penelo E, Treasure J, Vilarrasa N, Gil-Montserrat de Barnabé M, Casanueva FF, Tinahones FJ, Fernández-Real JM, Frühbeck G, de la Torre R, Botella C, Agüera Z, Menchón JM, FernándezAranda F (2014) Loss of control over eating: a description of the eating disorder/obesity spectrum in women. Eur Eat Disord Rev 22:25–31. https://doi.org/10.1002/erv.2267 4. Bulik CM, Marcus MD, Zerwas S, Levine MD, La Via M (2012) The changing "weightscape" of bulimia nervosa. Am J Psychiatry 169:1031–1036. https: //doi.org/10.1176/appi. ajp.2012.12010147 5. Palavras MA, Hay P, Santos Filho CA, Claudino A (2017) The efficacy of psychological therapies in reducing weight and binge eating in people with bulimia nervosa and binge eating disorder who are overweight or obese–a critical synthesis and meta-analyses. Nutrients 9:E299. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu9030299 6. Iacovino JM, Gredysa DM, Altman M, Wilfley DE (2012) Psychological treatments for binge eating disorder. Curr Psychiatry Rep 14:432–446. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-012-0277-8 7. McElroy SL, Guerjikova AI, Mori N, Munoz MR, Keck PE Jr (2015) Overview of the treatment of binge eating disorder. CNS Spectr 20:546–556. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1092852915000759 8. Brownley KA, Berkman ND, Peat CM, Lohr KN, Cullen KE, Bann CM, Bulik CM (2016) Binge-eating disorder in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med 165:409– 420. https://doi.org/10.7326/M15-2455 9. Niego SH, Kofman MD, Weiss JJ, Geliebter A (2007) Binge eating in the bariatric surgery population: a review of the literature. Int J Eat Disord 40:349–359 10. Hart LM, Granilo MT, Jorm AF, Paxton SJ (2011) Unmet need for treatment in the eating disorders: a systematic review of eating disorder specific treatment seeking among community cases. Clin Psychol Rev 31:727–735. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. cpr.2011.03.004 11. Wilfley DE, Welch RR, Stein RI, Spurrell EB, Cohen LR, Saelens BE, Dounchis JZ, Frank MA, Wiseman CV, Matt GE (2002) A randomized comparison of group cognitive–behavioral therapy and group interpersonal psychotherapy for the treatment of overweight individuals with binge-eating disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 59:713–721 12. da Luz FQ, Swinbourne J, Sainsbury A, Touyz S, Palavras M, Claudino A, Hay P (2017) HAPIFED: a healthy approach to weight management and food in eating disorders: a case series and manual development. J Eat Disord 16:5–29. https://doi. org/10.1186/s40337-017-0162-2 13. Fairburn CG (2008) Cognitive behavior therapy and eating disorders. The Guilford Press, New York 14. Grilo CM, Masheb RM, Wilson GT, Gueorguieva R, White MA (2011) Cognitive–behavioral therapy, behavioral weight loss, and sequential treatment for obese patients with binge-eating disorder: a randomized controlled trial. J Consult Clin Psychol 79:675–685. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0025049 15. Klein S, Burke LE, Bray GA, Blair S, Allison DB, Pi-Sunyer X, Hong Y, Eckel RH (2004) American Heart Association Council on Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Metabolism clinical implications of obesity with specific focus on cardiovascular disease: a statement for professionals from the American Heart Association Council on Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Metabolism: endorsed by the American College of Cardiology Foundation. Circulation 110:2952–2967 16. Sainsbury-Salis A (2007) The don’t go hungry diet. Bantam, Australia 17. American Psychiatric Association (APA) (2013) Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edn. American Psychiatric Publishing, Arlington 18. Claudino AM, Pike KM, Hay P, Keeley JW, Evans SC, Rebello TJ, Bryant-Waugh R, Dai Y, Zhao M, Matsumoto C, Herscovici CR, Mellor-Marsá B, Stona AC, Kogan CS, Andrews HF, Monteleone P, Pilon DJ, Thiels C, Sharan P, Al-Adawi S, Reed GM (2019) The classification of feeding and eating disorders in the ICD-11: results of a field study comparing proposed ICD-11 guidelines with existing guidelines. BMC Med 17:93. https://doi. org/10.1186/s12916-019-1327-4 13 Eating and Weight Disorders - Studies on Anorexia, Bulimia and Obesity 19. Palavras MA, Hay P, Touyz S, Sainsbury A, Luz F, Swinbourne J, Estella NM, Claudino A (2015) Comparing cognitive behavioural therapy for eating disorders integrated with behavioural weight loss therapy to cognitive behavioural therapy enhanced alone in overweight or obese people with bulimia nervosa or binge eating disorder: study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Trials 16:578. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-015-1079-1 20. Kass AE, Kolko RP, Wilfley DE (2013) Psychological treatments for eating disorders. Curr Opin Psychiatry 26:549–555. https:// doi.org/10.1097/YCO.0b013e328365a30e 21. Hay P, Chinn D, Forbes D, Madden S, Newton R, Sugenor L, Touyz S, Ward W (2014) Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists. Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists clinical practice guidelines for the treatment of eating disorders. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 48:977–1008. https://doi. org/10.1177/0004867414555814 22. Polnay A, James VA, Hodges L, Murray GD, Munro C, Lawrie SM (2014) Group therapy for people with bulimia nervosa: systematic review and metaanalysis. Psychol Med 44:2241–2254. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291713002791 23. Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, Amorim P, Janavs J, Weiller E, Hergueta T, Baker R, Dunbar GC (1998) The Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview MINI the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM IV and ICD 10. J Clin Psychiatry 59(20):22–33 24. Fairburn CG, Cooper Z, Connor M (2014) The eating disorder examination, 17th ed. The Centre for Research on Eating Disorders at Oxford. https:/www.credo- oxford .com/pdfs/EDE170 D.pdf. Accessed 3 July 2015. 25. Latner JD, Mond JM, Kelly MC, Haynes SN, Hay PJ (2014) The Loss of control over eating scale development and psychometric evaluation. Int J Eat Disord 47:647–659. https://doi.org/10.1002/ eat.22296 26. Skrondal A, Rabe-Hesketh S (2004) Generalized latent variable modeling: multilevel, longitudinal, and structural equation models. Chapman & Hall/CRC Press, Boca Raton 27. Cohen J (1988) Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, New Jersey 28. Chen H, Cohen P, Chen S (2010) How big is a big odds ratio Interpreting the magnitudes of odds ratios in epidemiological studies. Commun Stat Simul Comput 39:860–864 29. Li KH (1987) Imputation using Markov chains. J Stat Comput Simul 30:57–79 30. Rubin DB (2004) Multiple imputation for nonresponse in surveys. John Wiley and Sons, New York 31. 31. StataCorp (2017) Stata Statistical Software: Release 15 StataCorp LLC College Station 32. IBM Corp Released (2011) IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 20.0. IBM Corp, New York 33. Fairburn CG, Cooper Z, Doll HA, O’Connor ME, Bohn K, Hawker DM, Wales JA, Palmer RL (2009) Transdiagnostic cognitive–behavioral therapy for patients with eating disorders: a twosite trial with 60-week follow-up. Am J Psychiatry 166:311–319. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.08040608 34. McIntosh VVW, Jordan J, Carter JD, Frampton CMA, McKenzie JM, Latner JD, Joyce PR (2016) Psychotherapy for transdiagnostic 13 35. 36. 37. 38. 39. 40. 41. 42. 43. 44. binge eating: a randomized controlled trial of cognitive–behavioural therapy, appetite-focused cognitive–behavioural therapy, and schema therapy. Psychiatry Res 30:412–420. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.psychres.2016.04.080 Wonderlich SA, Peterson CB, Crosby RD, Smith TL, Klein MH, Mitchell JE, Crow SJ (2014) A randomized controlled comparison of integrative cognitive-affective therapy (ICAT) and enhanced cognitive–behavioral therapy (CBT-E) for bulimia nervosa. Psychol Med 44:543–553. https: //doi.org/10.1017/S00332 91713 0010 98 de Zwaan M, Herpertz S, Zipfel S, Svaldi J, Friederich HC, Schmidt F, Mayr A, Lam T, Schade-Brittinger C, Hilbert A (2017) Effect of internet-based guided self-help vs individual face-toface treatment on full or subsyndromal binge eating disorder in overweight or obese patients: the INTERBED randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry 74:987–995. https://doi.org/10.1001/ jamapsychiatry.2017.2150 Hilbert A, Bishop ME, Stein RI, Tanofsky-Kraff M, Swenson AK, Welch RR, Wilfley DE (2012) Long-term efficacy of psychological treatments for binge eating disorder. Br J Psychiatry 200:232–237. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.110.089664 Hay PJ, Claudino AM (2010) Bulimia Nervosa. BMJ. Clin Evid 19:2010 Linardon J, Hindle A, Brennan L (2018) Dropout from cognitive–behavioral therapy for eating disorders: a meta-analysis of randomized, controlled trials. Int J Eat Disord 51:381–391. https ://doi.org/10.1002/eat.22850 Ariel AH, Perri MG (2016) Effect of dose of behavioral treatment for obesity on binge eating severity. Eat Behav 22:55–61. https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2016.03.032 Dalle Grave R, Calugi S, Molinari E, Petroni ML, Bondi M, Compare A, Marchesini G; QUOVADIS Study Group (2005) Weight loss expectations in obese patients and treatment attrition: an observational multicenter study. Obes Res 13:1961–1969 Scientifically sound—–reproducible research in the digital age. Cohen’s D: how to interpret it? (2017). https: //scient ifica llyso und. org/2017/07/27/cohens -d-how-interp retat ion/. Acessed 06 January 2020 Cooper Z, Calugi S, Dalle Grave R (2019) Controlling binge eating and weight a treatment for binge eating disorder worth researching. Eat Weight Disord 18:9–10. https://doi.org/10.1007/ s40519-019-00734-4 Pattinson AL, Nassar N, Luz FQ, Hay P, Touyz S, Sainsbury A (2019) The real happy study protocol for a prospective assessment of the real world effectiveness of the HAPIFED program a healthy approach to weight management and food in eating disorders. Behav Sci 9:72. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs9070072 Publisher’s Note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.