[Industrial Marketing Management 1982-feb vol. 11 iss. 1] Renato Fiocca - Account portfolio analysis for strategy development (1982) [10.1016 0019-8501(82)90034-7] - libgen.li

Anuncio

![[Industrial Marketing Management 1982-feb vol. 11 iss. 1] Renato Fiocca - Account portfolio analysis for strategy development (1982) [10.1016 0019-8501(82)90034-7] - libgen.li](http://s2.studylib.es/store/data/009421155_1-34d374ae74ffa1d203f84b9927072308-768x994.png)

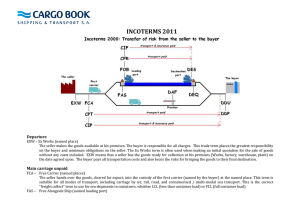

I I PIE I I Account Portfolio Analysis for Strategy Development * Renato Fioccat- This article proposes a method of composhzg and complementing industrial marketing strategy. A new approach to industrial marketh~g strategy is presented, it has the customer as the core of the analysis and considers some of the most important elements of industrial marketing, such as derived demand and buyer~seller relationships. This new approach, ,.'ailed account portfolio analysis, offers some indications to bulustrial managers and scholars for the analysis of markethzg strategies tailored expressly for industrial companies. INTRODU .¢,TION With only a few notable exceptions [1,2], the need to distinguish between industrial and consumer products has been seldom recorded in marketing strategy and strategic planning literatures. Strategic analysis methods, such as the product portfolio analysis by the Boston Consulting Group [3], the McKinsey/General Electric approach [41, *An Italian versien of this amcle has been published in Svi/uppoe Organi:zazione 62:35-47 (November-December 1980) under the title "L'Analisi dei Portafoglio Clienti nel Marketing Industriale." tThe author expresses great appreciation and gratitude to Associate Professor Thomas V. Bonoma of the Harvard Business School lot his review of the manuscript, th0: useful comments, and encouragement. Gratitude is also due to Professors Luigi Guatri and Stefano Podesta of Bocconi University and to Scuola di Direzione Aziendale of Bocconi University and the Italian National Research Committee (C.N.R.) for financial support. Industrial MarketingManagement 11, 53-62 (1982) ~) Elsevier Science Publishing Co., Inc., 1982 52 Vanderbilt Ave., New York, New York 10017 and the PIMS project (Profit Impact of Marketing Strategy) [41, have been developed without fully exploring the distinctive features between industrial end consumer marketing. The lack of specific emphasis on extremely ienponant factors in the industrial market, such as derived demand, sales concentration, structure and distributio,n of the power in the market, and buyer/seller relationships, can hide relevant implications in formulating industrial marketing strategy. IMPORTANCE OF THE CUSTOMER IN INDUSTRIAL MARKETS Effective marketing strategies must begin wi~h complete understanding of the most relevant factors that shape the particular environment where the finn operates. Many factors suggest that in formulating industrial marketing strategy the consideration and analysis of the customer is critically important. According to Webster: "'All good indus~al marketing planning begins and ends with the customer and takes the product as a variable, not as a given" [2, p. 19]. In industrial markets the critical importance of each single custcwer derives from several factors; the most important one.s are listed below: 1. Sales concentration. Industrial markets consist of a limited number of important buyers responsible for 53 _ • III I IIII i --- iI an important share of the seller's business. Moreover, each customer often has special and unique needs and behaviors that are not comparable with the needs and behaviors of other customers. As consequence, industrial sellers must often handle each customer individually. 2. Structure of the power in the market. Because of the considerable importance of each buyer, the buyer's contractual force, his power is very significant. In industrial markets it is very usual to observe cases in which the power is almost equally divided between buyer and seller 151. Industrial marketers can partially reduce *he effects arising from customers' power by weaving a network of durable and constructive working relationships with their customers. 3. Buying process complexly.,. Inside each buying company the industrial seller often interacts with managers who have personal and professional pursuits that are often very different. The differences in objectives pursued by the persol[ls in~,olved in the buying process reinforces the riced for a careful analysis of each customer. 4. Buyer~seller relationships. Smc~ " ; markeJng indus. trial products is often a long-term process in which repeat buying is extremely imi~ortant, industrial sellers are interested in building ;trong and durable customer relationships. Accordi g to Corey, "The development of strong, multidim,~nsional, an:] constructive working relationships v,ith one's customers is the key to industrial markq;ting success" [I, p. 5l. i 5. Derived ~&mand. The particulal!" nature of industrial demand also increases the strategic importance of the customer in industrial mlarketing. In fact, every marketing decision made by industrial sellers should take into account not only the market and the competition for their produlct, but also, and importantly, the market and cor~petition for their customer's product. As a result off derived demand, industrial marketers must alw@s be up to date about the current and prospecti/ve trends ir, their customer's business. ! I Since the customer becomes the cor,: of the analysis in industrial marketing strategy, it can be convenient for the i f Renato Fiocca is Assistant Professor at Bocconi University and at Scuola di Direzione Aziendale, Milan, Ita~,ly,where he teaches marketing in graduate and undergraduate courses. 54 .......... J,I "'" " ' Ii Ill 1 I III selling company to divide its business among accounts, rath.. Jan among products or product lines. In so doing, Ihe selling company should always consider that each account must be a homogeneous entity and must be meaningful from a quantitative (i.e., in terms of sales) point of view. As a rule each account fits in with one customer, that is, with a buying company. However, when the buying company is very diversified and centralized purchasing operations are not used, it can be more useful for the selling company to deal with the divisions and to consider each division as a single account. ACCOUNT PORTFOLIO ANALYSIS Account portfolio analysis is a two-step analysis that is based on the customer and on the related accounts. On a general level the complete portfolio of the selling company is considered. Industrial sellers can develop a graph, indicating the strategic importance of each account and the difficulties in managing it. The second step is an in-depth analysis of each important account. At this level, account portfolio analysis consists of a twodimensional display with the customer's business attractiveness on one axis and the buyer/seller relationship on the other. This enables the seller to assess marketing strategies and profitability with respect to the account considered. ,Step One: Analyzing the Accounts on a General Level From an overview of all their accounts, industrial sellers can rate the importance and the difficulty of managing each account, in particular, industrial sellers can establish which accounts need special attention and which deserve in-depth analysis. Nearly all companies have customers they regard as more important than the rest. Similarly, all companies have accounts that are more difficult to manage than others~ usually because of the special needs and behaviors of the customers. Generally industrial sellers consider an account very important when its purchases----or potential purchasesm are larger than those of other buyers. However, other elements can define an account as an "important account." When the account is particularly prestigious (for example, industrial companies that participated in the NASA projects) or a market leader, industrial sellers may only marginally consider the amount of purchases. These are usually considered important accounts because deal- ing with them increase the prestige of the company, thus aiding in the development of future accounts Other elements that make an account important can be grouped under the label of "overall account desirability." To determine this status the industrial seiler should consider the following questions. Can the relationship with an account diversify the industrial company's business? Improve company's technological strength? Open new markets (from domestic to international)? Improve, or conversely, spoil relationships with other customers? The factors by which the strategic importance of the account can be determined are summarized below: • • • • • Volume or dollar value of purchases Pt~tential of the account Prestige of the account Customer market leadership Overall account desirability • company's business diversification • open new markets • improve technological strength • improve/spoil other relationships In addition to looking at the account's strategic importance, industrial sellers need to determine the difficulty of managing each account. There are numerous factors involved here and they differ in nature and importance. They can be grouped under three major headings: (1) product characteristics, (2) account characteristics, and (3) competition for the account. II I larly difficult in the early stages of the product's development, since the customer often does not fully understand how the product works and how to draw the best results from it. Differences among customers in terms of needs and requirements and often in terms of behavior are typical in industrial markets. Some customers may require different levels of post-sale service or may need detailed technical information in the sales presentation. Yet the amount of time needed before making a purchasing decision vary widely from customer to customer. As a result of customers' heterogeinity, there are some customers with whom it is very easy to deal with, while with some others it is much more difficult. Generally, industrial sellers can obtain this kind of information directly from the salespeople in direct contact with the customers. The customer's buying power is another important element defining the difficulty in managing the account. For example, customers hold a powerful position when their purchases represent an important share of the selling company's sales, or when the products purchased are standard or undifferentiated, i.e., when they can easily change suppliers without suffering high switching costs. (An in-depth analysis of buyers' power is given in Refs. 5 and 6.) As a rule, the stronger the buyer's power, the more difficult it is to deal with the account. A strong customer can impose rules regarding terms of purchase and conditions of payment. In other circumstances, the objectives pursued by customers in their buying activity II Analyze the accounts on a general level Product characteristics are often determined by what meets the particular needs of each customer rather than by what is inherent in the product itself. For example, a piece of equipment can be considered extremely complex by a buyer who is using it for the first time; on the contrary, another customer can consider the same equipment very simple, since he or she knows how to use it. Generally speaking, the more the product is perceived as complex, the more the relationship with the account requires special attention. In these cases the seller must closely follow the customer's operations and sometimes must educate the customer in the use of the product. In addition, the relationship with an account is particu- can increase the difficulty of an account. For example, some customers want to buy from more than one supplier (usually three or four) and because of the increased competition among sellers, they are usually able to obtain better purchasing conditions. The intensity of competition on the account is another element that defines the difficulty in managing the account. Generally speaking, the higher the competitie.n on the same account, the more difficult it is for each selling company to manage that particuhtr account. The number of competitors on the account, their strength and weakness, and their position vis-a-vis the customer can indicate the intensity of competition ,on the account. 55 The factors from which the diffi;,ulty in managing the account depends are summarized belowl: • Product characteristics • novelty • complexity • Account characteristics • customer's needs and requirements • customer's buying behavior • customer's technical and commercial competence • customer's power • customer creates competition (wants many suppliers) • Competition for the account • number of competitors • strengths and weaknesses of competitors • competitors position vis-/l-vis the customer By combining these two variablesmstrategic importance of the account and difficulty in managing the accountuin a two-dimensional matrix (Fig. 1), industrial sellers can have a clear and immediate picture of their entire account portfolio. Both strategic importance of the account andi difficulty in managing the account can be high or low. The accounts can lie in one of four quadrants where they are defined as key/nonkey with resp(ct to the strategic importance of the account and dif!icult/easy with respect to the management of the acco mt. Upon examining the position of their accounts on t ~e matrix, industrial sellers can decide which accounts deserve a more in-depth analysis. Generally speaking, the accounts in quadrants 1 and 2 can be considered worth~ of further analysis. The industrial seller should restrict the number of accounts to analyze, considering only the key accounts, since the second part of account portfolio analysis involves analyzing each account in depth, which can be both time consuming and costly. high difficulty in managing the account Key Difficult I low 56 Nonkey Difficult 3 Key Easy 2 Nonkey Easy 4 high low Step Two: Analyzing a Key Account The second part of account portfolio analysis is based on a nine-celled matrix (Fig. 2). Each matrix graphically represents a single account. For example, if the selling company has five key accounts, as defined in the first part of the analysis> ~ e analysis must start from the arrangement of five matrixes, one for each account. The following variables are considered in the matrix: 1. The customer's business attractiveness (vertical axis) 2. The relative stage of the present buyer/seller relationship (horizontal axis) CUSTOME~'S BUSINESS ATTRACTIVENESS Account port folio analysis does not consider the industrial seller's product: demand, but the demand of the product of the industrial seller's customer. For example, if the account is General Motors and the industrial company is selling engine carburetors (for example, the selling company is Bendix), Bendix management is interested in examining the market trend of General Motor's products, i.e., cars, trucks, buses, and so on, and not the trend of the engine carburetor market. In other words, in order to have information about the trend of his products the industrial seller must consider the evolution of the customer's market. By using this approach the industrial seller considers the derived nature of industrial demand, which is one of the most relevant factors in industrial markets. Customer's business attractiveness can be high, medium, or low. The concept of the customer's business attractiveness can be derived from some existing literature in strategic planning |4, pp. 211-227; 7]. In defining customer's high customer's business attractiveness medium low strong medium strategic importance of the account relative buyer/seller relationship FIGURE 1. FIGURE 2. weak I I business attractiveness, industrial sellers must analyze the attractiveness of the customer's market and the status/position of the customer's business. The factors that make a customer attractive are usually grouped under five major headings: market factors, competition, financial and economic factors, technological factors, and sociopolitical factors (Table 1). The basic question the industrial seller must answer is whether it is more or less convenient for the selling company to do business with a certain customer. In this case convenience is determined through an analysis of the customer's business attractiveness. If the market in which the customer operates is attractive and if the customer's position in the market is strong, one can expect that the operations of the selling company (which supplies products and raaterials) will result in a positive business relationship. Table 1 must be considered as a guideline for the analysis of customer's business attractiveness. While relatively complete, it is not exhaustive. When performing customer's business attractiveness analysis, industrial i sellers must keep in mind that there are often factors that are unique to the industry involved. As a consequence, each customer's business must be examined separately, with its unique features taken into account. Very often management judgment and experience ca~ facilitate the understanding of customer's businesses, even more than the analysis of the factors listed in Table 1. The analysis of customer's business attractiveness can be more or less sophisticated depending on how many businesses the seller has decided to examine. If it is necessary to analyze a great number, the selling company can decide to dramatically reduce the variables considered. If only a few businesses are to be examined, the amount of detail and time invested can be considerable. RELAT|VE STAGE OF THE PRESENT BUYER/SELLER RELA'rlONSHIP The relative stage of the present buyer/ seller relationship is plotted on the horizontal axis of Fig. 2. Because of its strategic importance in industrial marketing, the buyer/seller relationship can be considered a measure of the competitive position of the selling company. In order to have more information about the TABLE 1 Measurement of Customer's Business Attractiveness" Attractiveness of Customer's Market Status,Position of Customer's Business Market Factor~ Size (dollars, unit, or both) customer's share: Size of key segments customer's share of key segments Growth rate per year customer's growth rate Sensitivity to price, service features customer's influence on the market and external factors Types of competitors Degr-e of concentration Changes in type and mix Substitution by new technology Competition customer's position, strength and weakness degrees and types of integration Financial and Contribution margins Leveraging factors, such as economies of scale and experience Barrier to entry or exit (both financial and non financial) Capacity utilizg~tion customer's vulnerability to new technology customer's level of integration Economic Factors customer's margins customer's scale and experience barriers to customer's entry or exit customer's capacity utilization Technological Factors Maturity and frequency of changes Customer's ability to cope with changes Complexity Depth of customer's skills Differentiation Types of customer's technological skills Patents and copyrights Customer's patent protection Changes in the environment Sociopolitical Factors Customer's ability to cow and to fit '+Source: adapted from Ref. 4, p. 214 57 I 1 ii strength ,of a buyer/seller relationship it is necessary to compare the existing relationship.between a buyer and seller with the buyer's relationships with other companies that are in competition with the selling company. For example, Bendix (selling company), in order to evaluate its relationship with General Motors (buying company), must compare it with the relationships that General Motors has with the direct competitors of Bendix, i.e. Bosch, Lucas, and so on. The buyer/seller relationship call be strong, medium, or weak. To assert that a relationship with a customer is strong, medium, or weak can be extremely easy or very difficult for the selling company. It, of course, depends on how much knowledge the seller has of his customers and of the relationships that the3, have with other sellers. Certainly a relationship is strong when it has lasted many years, when the volume or dollar value of purchases is large, or when the percentage of customer's purchases on supplier"s sales is high. Other factors are less easily measurable; for example, a relationship can be strong when there is "friendship" between buyer and seller, which, in business, can be defineG as the common wish to cooperate and to reach positive results for both. A relationship can be equally strong if one of the participants--buyer or seller has enough power to establish an authoritative and domineering relationship. The geographic location of buy r and seller can also ; influence the strength of the relationship. Certainly proximity encourages the development of a strong relationship, since it is easier to meet and communicate. The converse holds as well. Differences in language and culture can diminish the strength of a buyer/seller relationship. For example, many Western companies find it difficult to deal with Japanese customers because their business mannerisms are often very different from what is usual in the United States and in Europe. Some of the factor,; that make a buyer/seller relationstdp strong or weak are listed in Table 2. Table 2 is intended to be suggestive only. In analyzing the strength of the relationship with the customer, the selling company will probably eliminate or add some items, depending on the relationship being considered. Often the selling company has more than one relationship with the same account. For example, if the selling company sells three different products to the same customer (i.e., to the same account) it is likely that there exist three different relationships, perhaps of different strength, 6ach one based on one product. In these cases the measurement of the strength of the relationship must 58 TABLE 2 Measurement of the Strength of the Buyer/Seller Relationship Relationship Factors Strong Weak Length of the relationship Volume or dollar value of purchases Importance of the customer (i.e., percentage of customer's purchases on supplier's sales) Power of the participants (one or both) Friendship Cooperation in development Management "'distance" (language and culture) Geographic distance long high short low high high yes high low near low low no low high far be arranged separately. Some of the factors that influence the strength of the relationship (for example, geographic distance) remain unchanged, since they are related to the account in general. On the contrary, other factors, such as length of the relationship, volume or dollar value of purchases, etc., can change with respect to the relationship considered. How to Arrange an Account Portfolio Matrix An example can clarify how to arrange an account portfolio matrix. Assume that the selling company "'A" produces and sells two products ( " x " and " y " ) to five customers: accounts " 1 " - " 5 . " Consider only account 1. Account 1 is an automotive producer and has three product lines: cars "'~a," trucks "' l b , " and buses " l c . " Account 1 buys products x and y from company A; product x is used in the production of products I a and I b, while product y is u,;.ed for products lb and lc. Company A has a strong relationship with account 1 with respect to product x and a medium relationship with respect to product y. Customer's 1 business attractiveness is low for product l a (cars), medium for product l b (trucks), and high for product lc (buses). The essential data are summarized in Table 3. TABLE 3 Company "A" vs. Account (or Customer) "1" f P r o(strong d u c t relationship) "x'" I i product "'ia'" (low attractiveness) product ""I b'" (medium attractiveness) Product ""y" I (medium relationship) I Product "'lb" (medium attractiveness) / [_... product ""Ic" (high attractiveness) high customer's business attractiveness medium * lc/y * ! b/x low * I b/y * la/x strong medium weak relative buyer/seller relationship FIGURE 3 At this point it is possible to determine the position of the two products (x and y) in the matrix, with respect to the customer's business attractiveness of products l a, l b, and lc (Fig. 3). Inside the matrix two other variables can be inserted (Fig. 4): !) The dollar value of purchases of the buying company for every single product (depicted by the area of file circle representing each product on the matrix). By following the same example, company A needs to know what is the total amount of purchases of account i with respect to products x and y (purchases from company A and from other supplying companies), in oJaterto be able to determine the second variable; that is, 2) The account market share for each product, represented by the dark pie slice inside the circle. The size of the account market share gives information about the effective position of the selling company in a given account vis41-vis its competitors. The dollar value of account i for produclts x and y and the account market share held by company A complete the design of the matrix as in Figure 4. In order to complete the analysis of its account, company A must arrange matrices for account 2-5. In some circumstances it is necessary to add another vm'iable: the short period potential of each product in a given account, represented by a dashed circumference (Fig. 5). In an account portfolio the concept of potential appears twice: a long-term and a short-term potential. The account's long-term potential is a direct result of the different product positions in the matrix in correspondence with the axis of the ordinates, i.e.. customer's business attractiveness. In fact, selling a product ~o a firm that is in a very attractive business offers greaters pros- company A marl~ct s h a r e of p r o d u c t x in a c c o u r t ! actua! de-anc ~f high i business Y ~n ~ccrunt J customerts mediu~ I attractiveness low stronc me'iu~ relative buyer/se!!er u e =,~, re! -t ; ~n -~ " - FIGURE 4. $9 S high custonerls business medium I/ ~ ~I Ir ~'~1 attractiveness m low i strong medium weak relative buyer/seller rel~tionship FIGURE 5. pect for growth than selling the same product to a firm in an unattractive business. The short tern1 potential, represented by the dashed circumference in Fig. 5, refers to 'he industrial seller's product (and not to the customer's product) and represents the normal concept of potential which usually is adopted in marketing, even though here it refers strictly to a given account. Two reasons suggest distinguishing between short and long term potential. The first is that for some industrial products (equipment, for example), even if the customer industry is not in a promising phase, it is possible that the obsolete equipment will have to be replaced. The equipment rebuy can be an interesting opportunity for the selling company, but only in the short term. in fact, a new rebuy, if it occurs at all, will occur only after many years. The second reason why it is better to combine the analysis of short- and long-term potential relates to the time gag between when customer's business attractiveness appears and when it has positive results on the selling o)mpany's operations. This time gap can last for years, as it did in the color television market (the industrial prouuct considered is the TV picture tube). If indastrial companies base their decisions only on customer's business attractiveness, that is, on the long- 60 term potential, they could draw wrong conclusions. Combining short- and long-term potential can prevent the selling company from the dangers arising from a remote reality which is difficult to forecast and impossible to influence in any way. ANALYZINGTHEACCOUNTPORTFOLIO MATRIX By analyzing the position of their products in the account portfolio matrix (Fig. 4), industrial sellers can have information about • marketing strategies * profitability Marketinf°~trategies There a . hree basic strategies that industrial sellers can pursue: ,,,.i:"oving the strength of the relationship, holding the position, and withdrawal. Each strategy depends .an the position of the product inside the matrix with respect to customer's business attractiveness and relative buyer/seller relationship. The customer's business attractiveness will help industrial sellers to de,.ermine whether to improve the relationship with a certain customer. Improving the strength of the relationship is when the product is positioned in cells 1, 2, 4, or 5 of Fig. 2. The attractiveness of the customer's business should induce industrial sellers to invest time and money trying to better the relationship. When the relationship is weak (cells 1 and 4) the customer usually has a high perceived risk caused by the lack of information about the selling company and the product offered. Moreover, if the relationship is based on a new product, the customer's perceived risk tends to be higher. A team approach appears to be a valid way for improving the relationship with a customer whose business is promising. In this way the selling company can better understand and solve customer's problems and, as a consequence, it can be easier to start a durable relationship. However, the selling company must consider that team approach requires considerable efforts both in a financial and management point of view. As a result of different levels of customer's business attractiveness the needs and behaviors of the customers can change. When the customer's business attractiveness is particularly high, the customer often is very demanding both from a technological and a commercial point of view. High customer's business attractiveness often means high growth rates of the customer's industry; in these circumstances the customer usually has some difficulties in planning purchases, since it is difficult to forecast the market development. The ability in problem solving and the rapidity in product delivery become basic elements of the sale. In order to increase the intensity of the relationship with a c"~tomer who has a medium attractiveness, it is necessary to have the previously described capabilities even though the relationship is less stressing and can more easily managed. As a rule the buyer i.s able to plan orders since his market development is easier to forecast. In this respect the delivery punctuality (more than delivery rapidity) is very important. Holding the position is appropriate when the buyer/ seller relationship is strong (cells 3, 6, and 9). In this case the decision of the selling company should be oriented to the preservation of the strength of the relationship, paying attention to every possible external change (new competitors, new products, and so on) that can affect this strot~g position. The selling company must be particularly careful when one of its products is in cell 9. At first sight cell 9 should appear an almost card'ree situation for the selling comparty. There are few or no changes in R&D, few marketing expenses, and the quasicertainty that, when the customer needs a product he will contact the seller with whom he has a strong relationship. However, this is also a dangerous situation. In fact, if the customer's business Lsrecording a low attractiveness, the customer may try to better his position through diversification in other businesses where the selling company is probably no longer involved as a supplier. In this situation it is possible to suggest two different strategies. In the short term the selling company should try to examine, in cooperation with the customer, new forms of the same product. This would be done to obtain some reduction in customer's production costs and a related increase in the profit which could discourage, for the time being, diversification alternatives. In the medium-long term, sellers can offer their customer some diversification alternatives in new and more attractive businesses where they could have a promising position as a supplier. When the customer's business attractiveness is !o~ and the buyer/seller relationship is not strong (cells 7 and 8) any intervention that could better the selling company position is not advisable. A more advisable course for the selling company to adopt is a withdrawal strategy. The seller should only manage the relationship to prevent ruining the company's global image and the relationships founded on other products placed in more. promising cells. Profitability Concerning the different positions of the prt~uct in the account portfolio matrix some implications in tem~ of account profitability can be shown. In account portfolio analysis, profitability depends on the different price sensitivity of the customer and on the amount of marketing, product development, and R&D" expenses that are related to the different cells of the matrix. In the first stages of development of the relationship. usually marketing efforts are vet), intense since the selling company wishes to develop and consolidate its business. Consequently ~ k e t , n g expenses are also yen. high. When the bu)eriseller relationship is getting stronger, the selling company does not need to impro~,~c its position and the marI,~ting expense.,, tend to decrease New customers often ask that the product is adapted to their operations so that in opening a new relationship the selling company is often forced to change the offere6 product/service package. As a consequence. R&D and product development expenses are also sometimes higher in the first stages of the relationship. Profitability is also correlated to the customer's price 61 ,,,,, sensitivity that changes in reference to both the customer's business attractiveness position and to the stage of development of the relationship. It is possible to argt~e that customers in a very attractive business would not t;;: particularly concerned abom the cost of products and materials bought. Moreover, their price sensitivity decreases if the purchased product is a new one. In this case, the buying company usually has a lack of information about the potential supplying companies and the market prices, if they exist. On the contrary, when the customer's business attractiveness is in the lower levels an increase in price sensitivity is recorded, due to the less interesting perspectives of customer's profit and also due to the fact that, in the meantime, the customer has probably developed information ab,:}ut the possible alternatives and prices of the purchased products. Referring now to the sta~]e of development of the buyer/seller relationship, one can suppose that when the relationship is strong the selling company has a broader freedom in price fixing. In other words, it often happens that buyers .ale disposed to pay a reasonable additional price to buy from a supplier they trust. Customers' price sensitivity become much weaker when the relationship is so strong that the selling company has a quasimonopolistic position, having the complete share of the account, with regard to a determinate product. Combining the expenses of the selling company with the customer's price sensitivity, i~ is possible to generalize some conclusions ~n terms of profitability inside the account portfolio matrix. Generally speaking, profitability is 1o,~, in cells 1 and 4 due to the high level of marketing, product development, and R&D expenses, even if in these cells the selling company can have more freedom in price fixing, due to the weak customer's price sensitivity. On the contrary, in cell 6 and, above all, in cell 9 the expenses of the selling company decrease, and even if in the meantime customer's price sensitivity increases, it seems that the selling company's profitability would reach the highest levels. 62 i II I if I I I =,,,, ,,,, SUMMARY The critical ilnportance of the customer in industrial markets suggests that an industrial marketing strategy ~r~ust be based on the analysis of the customers and of the related accounts~ The new approach to industrial marketing strategy prol?osed in this article considers some of the most important elements that influence the decisions of industrial seller,;, such as derived demand and buyer/ seller relationships. A two-step analysis has' been prceosed. In the first part the complete poltfolio of accounts of the selling company has been considered. By analyzing all their accou~its industrial sellers can decide which accounts need special attention and, as a consequence, which accounts deserve a more in-depth analysis. In the second part of the analysis each " k e y " account has been analyzed. Through the examination of customer's business attractiveness and buyer/seller relationships, industrial marketers can define their marketing strategies with respect to each account considered. REFERENCES I. Corey, E. Raymond, Industrial Marketing: Cases ami Com'epts. Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ, 1976. 2 Webster. Frederick E., Jr, Industrial Marketing Strategy. New York. 1979. Boston Consulting Group Staff. Per.ff~ectiveon l:xperience. BCG, Boston, i 968. 4. Abell, Derek F., and Hammond, John S., Strategi,' Market Phmning. Prentice Hail, Englewood Cliffs, NJ, 1979. 5. Bonoma, Thomas V., and Johnston, Wesley J.. The Social Psychology of Industrial Buying and Selling. In&~stri,i Marketing Manageo,,,nt 7. 213224 (1978). 6. Porter, Michael E., Competitive Sltrategy. Free-Press, N:w York, 1980, pp. 24-27, ! 13-I 14. 7. Hofer, Charles W., and Schendel, Dan, Strategy Formul,~tion: Analvtit'al Con,'qJts. West Publishing Co., 19,78.