- Ninguna Categoria

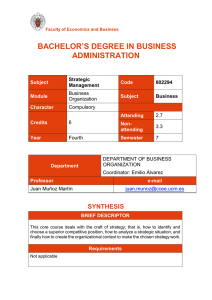

Introduction to Economics Course Guide - University of London

Anuncio