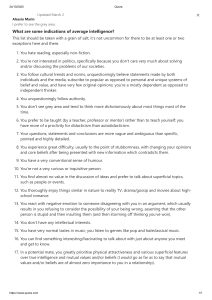

Copyright © The British Psychological Society Reproduction in any form (including the internet) is prohibited without prior permission from the Society 689 British Journal of Educational Psychology (2005), 75, 689–708 q 2005 The British Psychological Society The British Psychological Society www.bpsjournals.co.uk Confirmatory factor analysis of the Teacher Efficacy Scale for prospective teachers Gypsy M. Denzine1*, John B. Cooney2 and Rita McKenzie3 1 Northern Arizona University, USA University of Northern Colourado, USA 3 Buena Vista University, USA 2 Background. Research on teacher self-efficacy has revealed substantive problems concerning the validity of instruments used to measure teacher self-efficacy beliefs. Although claims about the influence of teachers’ self-efficacy beliefs on student achievement, success with curriculum innovation, and so on, may be true statements, one cannot make those claims on the basis of that body of evidence if the instruments are not valid measures of teachers’ self-efficacy beliefs. Aims. The purpose of this investigation is to employ the use of modern confirmatory factor-analytic techniques to investigate the validity of the hypothesized dimensions of the Teacher Efficacy Scale (Gibson & Dembo, 1984; Woolfolk & Hoy, 1990). Sample. Participants for this investigation were 387 prospective teachers recruited from a university located in the south-western region of the UA. Participants for Study 2 were 131 prospective elementary teachers recruited from the same university as in Study 1. Results. A confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) procedure was used to evaluate the goodness-of-fit for two theoretical models of the TES items. The proposed two- and three-factor models of teacher self-efficacy for prospective teachers were rejected. A re-specified three-factor model of the TES was then derived from theoretical and empirical considerations. The re-specified model hypothesized three dimensions: self-efficacy beliefs, outcome expectations, and external locus-of-causality. In Study 2, the re-specified three-factor measurement model was evaluated in a new sample. Results of the CFA procedure indicated satisfactory fit of the re-specified model to the data; however, the results were not consistent with predictions derived from social learning theory. Conclusions. The results of this study call into question the use of the TES and the interpretation of a large body of literature purporting to study the relationship of teachers’ self-efficacy beliefs to important educational outcomes. * Correspondence should be addressed to Gypsy M. Denzine, Associate Dean, College of Education, Northern Arizona University, PO Box 5774, NAU, Flagstaff, AZ 86011, USA (e-mail: [email protected]). DOI:10.1348/000709905X37253 Copyright © The British Psychological Society Reproduction in any form (including the internet) is prohibited without prior permission from the Society 690 Gypsy M. Denzine et al. Since two Rand Corporation studies (Armor et al., 1976; Berman & McLaughlin, 1977) investigated the role of teacher self-efficacy in teaching effectiveness, there has been a steady increase in research in this area. The construct of teacher self-efficacy refers to teachers’ beliefs about their ability to have a positive affect on student learning and their achievement (Ashton, 1984). Previous research indicates teacher self-efficacy is related to teachers’ success in curriculum innovation (Berman & McLaughlin, 1977), beliefs about students’ capabilities (Ashton, 1984) and intelligence (Klein, 1996), quality of student relationships (Ashton & Webb, 1986), confidence in working with parents (HooverDempsey, Bassler, & Brissie, 1987), time spent on academic learning (Allinder, 1995), selfefficacy of low-achieving students (Midgley, Feldlaufer, & Eccles, 1989), and their ability to hold students accountable for their learning and performance (Ashton & Webb, 1986). The more recent research on teacher self-efficacy has revealed substantive problems concerning the validity of instruments used to measure teacher self-efficacy beliefs (Brouwers & Tomic, 2003; Colardci & Fink, 1995; Henson, 2001, 2002; Henson, Kogan, & Vacha-Haase, 2001; Pajares, 1992; Tschannen-Moran, Hoy, & Hoy, 1998). Although claims about the influence of teachers’ self-efficacy beliefs on student achievement, success with curriculum innovation, and so on, may be true statements, one cannot make those claims on the basis of that body of evidence if the instruments are not valid measures of teachers’ self-efficacy beliefs. And, although new instruments for the measurement of teachers’ self-efficacy beliefs have recently appeared in the literature (Tschannen-Moran & Hoy, 2001) it is necessary to make sense of the existing body of data. Thus, the purpose of this investigation is to employ the use of modern confirmatory factor-analytic techniques to investigate the validity of the hypothesized dimensions of the TES (Gibson & Dembo, 1984; Woolfolk & Hoy, 1990) and to explore alternative interpretations in the event the hypothesized dimensions are disconfirmed. A brief history In the original Rand studies, teacher self-efficacy was measured by asking two questions: (a) ‘When it comes right down to it, a teacher really can’t do much because most of a student’s motivation and performance depends on his or her home environment’, and (b) ‘If I try really hard, I can get through to even the most difficult or unmotivated students’. The first question was hypothesized to assess teachers’ outcome expectations, typically labelled teaching efficacy (TE). In contrast, the second item was hypothesized to reflect personal teaching efficacy (PE). From this perspective, TE relates to a teacher’s outcome expectations and PE is based on the teacher’s judgments of his or her personal ability to influence student learning. Early Rand researchers grounded teacher self-efficacy in Rotter’s (1966) locus of control construct and placed significant emphasis on outcome expectations and personal responsibility when interpreting efficacy scores. Later, Ashton and Webb aligned the construct with a socialcognitive theoretical perspective of self-efficacy (1977, 1978). In contrast to the locus of control perspective, the social-cognitive approach emphasizes the relations between efficacy beliefs and outcome expectations. According to Bandura, outcome and efficacy beliefs are related but can be conceptually and empirically differentiated (1986, 1997). For Ashton and Webb, TE and PE represent measures of outcome expectations and efficacy expectations, respectively. One of the earliest attempts to measure the dimensions of teacher self-efficacy was conducted by Gibson and Dembo (1984), who developed the Teacher Efficacy Scale (TES) based on Ashton and Webb’s conceptual model. Gibson first piloted a 53-item Copyright © The British Psychological Society Reproduction in any form (including the internet) is prohibited without prior permission from the Society Teacher self-efficacy 691 version of the TES with 90 experienced teachers (Gibson & Brown, 1982). Based on results from a principal-factor analysis with orthogonal rotation, the authors reduced the TES to 30 items. Gibson and Dembo administered the revised 30-item TES to 208 elementary school teachers selected from 13 schools, with two-thirds of the sample having 10 or more years of teaching experience. Results of a principal-factor analysis on the TES items were used to infer the existence of two independent dimensions (r ¼ :19). By eliminating items with a factor pattern coefficient less than .45 (items that did not contribute to the reliability of the scale, and items that did not exhibit simple structure), the TES was reduced from 30 items to 16 items. Factor 1 (labelled PE) accounted for 18.2% of the total variance with a Cronbach’s a coefficient of .78 for the scores on this scale. Factor 2 (labelled TE) accounted for 10.6% of the total variance with a Cronbach’s a coefficient of .75 for the scores of this scale. Gibson and Dembo interpreted their findings to be consistent with Bandura’s model, which states that PE corresponds to self-efficacy, whereas TE measures an outcome expectancy dimension. Extending the research on teacher self-efficacy to prospective teachers, Woolfolk and Hoy (1990) administered a version of the TES that included the 16 items from the TES developed by Gibson and Dembo (1984), two items concerning the adequacy of their teacher preparation programme, and the two original Rand items. Woolfolk and Hoy administered the TES to 182 undergraduate liberal arts majors (155 women and 27 men) enrolled in the teacher preparation programme at a state university in the eastern region of the USA. The majority of the participants were sophomores (87%), with the remaining 13% equally divided between freshmen and seniors. In the USA, sophomore refers to second-year students. Freshmen, juniors, and seniors are first, third, and fourthyear students, respectively. Seventy percent of their sample were between the ages of 20 and 30. Fifty-seven percent of the sample were seeking certification in elementary education, and the remaining 43% sought certification in secondary education. Results from a principal axis factor analysis (using squared multiple correlations on the diagonal and the PA2 extraction option in SPSSx) of the TES items were interpreted by Woolfolk and Hoy (1990) to compose two dimensions of teacher efficacy that account for 27% of the variance in the data. Because the factors were essentially uncorrelated (r ¼ :008), it was further argued that the dimensions are independent. The factor structure and factor pattern coefficients were very similar to those reported by Gibson and Dembo (1984). Consistent with previous researchers, Woolfolk and Hoy labelled their two factors as teaching efficacy and personal efficacy; however, they hypothesized that the TE factor is a measure of one’s beliefs about the ability of teachers in general rather than a measure of outcome expectations, per se. To illustrate, the item with the highest factor pattern coefficient for the TE factor reads, ‘A teacher is very limited in what he/she can achieve because a student’s home environment is a large influence on his/her achievement’. Cronbach’s a coefficients for the scores on the 12 PE items and eight TE were .82 and .74, respectively. Two items (‘the influence of a student’s home experiences can be overcome by good teaching’, and ‘some students need to be placed in slower groups so they are not subjected to unrealistic expectations’) were dropped because they were unrelated to either factor. In further analysis, Woolfolk and Hoy (1990) evaluated Guskey’s (1981) claim that PE itself is actually composed of two dimensions. According to Guskey, positive and negative student outcomes are different facets of responsibility that differentially influence personal efficacy. The three-factor solution accounted for 32.8% of the variance. The factor pattern coefficients for TE items were similar in the two- and threefactor solutions; however, the PE items separated into two moderately, but inversely Copyright © The British Psychological Society Reproduction in any form (including the internet) is prohibited without prior permission from the Society 692 Gypsy M. Denzine et al. related (r ¼ 2:402) dimensions in the three-factor solution. Wookfolk and Hoy interpreted their three-factor solution as being consistent with Guskey’s interrelated dimensions of personal responsibility for positive (PE) and negative (PE) student outcomes. Ultimately, however, Woolfolk and Hoy opted for parsimony by adhering to the two-factor solution on the grounds that the relationships between efficacy and other relevant independent variables (e.g. beliefs about control) remained the same whether they used the two- or three-factor solution. In their study based on 161 pre-service teachers, Emmer and Hickman (1991) concluded the construct of teacher self-efficacy might be divided into three dimensions: personal efficacy in the areas of management and discipline, external influences, and personal teaching efficacy. They argue classroom management/discipline efficacy is distinct from other types of teacher efficacy. Emmer and Hickman used the method of principal axis factor analysis, followed by rotation using the varimax criterion. Although the researchers claim their results support and extend the conception of teacher efficacy advanced by Gibson and Dembo (1984), their interpretation of the obtained factor structure may be challenged. Most concerning is the researchers’ decision to move five items from one factor to another in order to provide a better conceptual fit of the data. For example, the item, ‘if a student did not remember information I gave in a previous lesson, I would know how to increase his/her reaction in the next lesson’ had a factor pattern coefficient of .57 for the classroom management/discipline efficacy factor but was moved to the personal teaching efficacy factor even though it had a factor pattern coefficient of less than .25 for this factor. Soodak and Podell (1996) replicated the factor structure obtained by Woolfolk and Hoy (1990) in both the two- and three-factor solutions in a sample of 310 experienced teachers (with a mean of 9.2 and a standard deviation of 8.2 years of teaching experience). Soodak and Podell, however, disagreed with Guskey’s (1981) interpretation that PE is composed of positive and negative dimensions of the same underlying construct. Rather, they claim the three factors of the TES reflect independent dimensions of personal efficacy, outcome efficacy, and teaching efficacy. In a subsequent study, Soodak and Podell (1997) replicated the two-factor structure of the TES in a sample composed of 169 prospective teachers and 626 experienced teachers. The average number of teaching years was 7.7 (SD ¼ 7:6) for the experienced teacher group. No differences were found between experienced and prospective teachers in ANOVA tests on the scales. The researchers, however, did not investigate the invariance of the measurement model across the two groups. Guskey and Passaro (1994) administered the TES (Gibson & Dembo, 1984) to a sample of 283 experienced teachers, (average 10.4 years teaching experience) and 59 prospective teachers. There were no differences in elements of the variance/covariance matrix of item responses between the experienced and prospective teachers. The factor model, however, was not evaluated for invariance. Although their results replicated the factor pattern found by Woolfolk and Hoy (1990), Guskey and Passaro concluded that the two dimensions of teacher self-efficacy do not represent PE and TE. Rather, they interpreted the scales as reflecting internal and external dimensions of efficacy. According to Guskey (1998), the internal and external dimension is similar to, but not isomorphic with, Rotter’s (1966) locus of control construct. The internal dimension measures the extent to which teachers believe they, and teachers in general, can or do have influence on students’ learning. Whereas the external dimension measures teachers’ perceptions of the influences of factors that exist outside the classroom, beyond the teacher’s control. Guskey distinguished these dimensions from internal Copyright © The British Psychological Society Reproduction in any form (including the internet) is prohibited without prior permission from the Society Teacher self-efficacy 693 and external locus of control variables by arguing they are distinct and independent, not simply opposite poles on a continuum, as is the case with the internal/external dimensions of locus of control. Further, Guskey argued that previous studies have yet to explain or describe the construct of teacher self-efficacy with these two dimensions, as there may be other factors playing equally important roles in the construct of teacher self-efficacy. Deemer and Minke (1999) used a modified version of Gibson and Dembo’s (1984) TES to test Woolfolk and Hoy’s (1990) hypothesis that items load onto factors due in part to wording confounds within the scale, specifically the positive and negative orientations of the items (‘I can: : :’ and ‘teachers cannot: : :’). This confound was also pointed out by Guskey and Passaro (1994), who suggested internal and external dimensions of efficacy instead of personal and teacher efficacy. Therefore, Deemer and Minke investigated a two-factor solution indicating factors that would reflect the positive or negative orientation of the wording of the items, and a four-factor structure, which included Guskey and Passaro’s internal/external dimensions. The four-factor solution was hypothesized to show items clustering into positive and negative dimensions for both internally and externally oriented TES items. Two modified versions of the TES, comprised the 16 Gibson and Dembo items and one of the items from Woolfolk and Hoy’s instrument were used, reflecting items all written in the first person with positively and negatively oriented wording available for each item. The sample included 196 practising teachers, who were administered one of the two differently worded versions of the TES. One group had an average of 6.8 years teaching experience, while the other had 8.4 years of teaching experience. Using principal axis factoring with oblimin rotation, it was found that the four-factor structure was not adequate, as items did not cluster meaningfully into the internal/external and positive/negative dimensions. In addition, the two-factor structure was not adequate, as items failed to load meaningfully on either of the two proposed factors. While the majority of previous researchers have employed exploratory factoranalytic techniques, Kushner (1993) used a confirmatory factor-analytic approach to investigate a measurement model underlying the Teacher Self-Efficacy Scale. Kushner tested the two-factor model proposed by Woolfolk and Hoy (1990) with two samples of pre-service teachers. In an effort to validate the use of the TES for pre-service teachers, Kushner modified several items so that they would better reflect an individuals’ status as a future teacher. In this study, the wording of the 12 PE items used by Woolfolk and Hoy was modified, to reflect status as a future teacher. For example, wording such as ‘when I really try: : :’ was changed to ‘if I really try: : :’. The eight items from the TE scale were not modified. The two original Rand items were not included in this study. The modified scale was administered twice, once during the summer term to 192 pre-service education majors and again in the autumn term to 162 pre-service education majors. Principal axis factoring using PA2 and varimax rotation resulted in the researchers’ interpretation of a two-factor solution for the first administration. Results from the EFA revealed several departures from Woolfolk and Hoy’s two-factor model interpretation. Specifically, two PE items (Item 15 ‘if a student in my class becomes disruptive and noisy, I will know some techniques to redirect him/her quickly’ and Item 20, ‘my teacher training programme and/or experiences will give me the necessary skills to be an effective teacher’) loaded almost identically on the TE factor. Results from a subsequent CFA indicated a lack of fit and a rejection of the measurement model. Specifically, the x value (419.20), goodness-of-fit index (.80), adjusted goodness-of-fit index (.75), and root MSE residual (.09) are all indicative of a poorly fitting model. Kushner used the second Copyright © The British Psychological Society Reproduction in any form (including the internet) is prohibited without prior permission from the Society 694 Gypsy M. Denzine et al. sample to replicate the previous study. Using EFA (PA2 and varimax rotation) again with the second administration revealed slightly different factor pattern coefficients, but again subsequent CFA suggests a poor fit of the model. In the second study, CFA results were fairly similar to those in the first analyses (x ¼ 419:20, goodness-of-fit index ¼ .83, adjusted goodness-of-fit index .79, and root MSE residual (.9). Kushner concluded that the rewording of items to better match the experiences of pre-service teachers did not influence the structure of the construct when EFA techniques were employed. Based on CFA results, Kushner concludes that TES items and subscales may need to be revised or eliminated before the scale can be recommended for use with pre-service teachers. Kushner did not, however, use CFA results to re-specify a proposed measurement model for the TES. Brouwers and Tomic (2003) commented on Kushner’s (1993) work, noting that it is not possible to conclude whether the observed lack of fit was a consequence of a poorly fitting two-factor model, one or more poorly operationalized items, or a combination of both. In response to the competing measurement models of the TES, Brouwers and Tomic (2003) conducted a study to test several factor models, which have been summarized in this article. They tested the following four models: (a) the two-factor model initially proposed by Gibson and Dembo (1984), (b) Woolfolk and Hoy (1990) and Soodak and Podell’s (1996) three-factor model, (c) the three-factor model proposed by Emmer and Hickman (1991), and (d) a four-factor model, which contained a teaching efficacy factor and three factors in which the items of the personal teaching efficacy factor were divided into three factors: the classroom management efficacy factor of Emmer and Hickman, the outcome efficacy factor of Soodack and Podell, and the personal efficacy factor of Soodack and Podell, excluding the items pertaining to classroom management. Brouwers and Tomic used a confirmatory factor-analytic approach to investigate the aforementioned measurement models with a sample of 540 practising teachers in the Netherlands. Their sample included 321 male teachers and 219 female teachers. Their average age was 44.7 (SD ¼ 8:97) with a range of 21–69 years. Their sample of teachers had a wide range of experience from 0 to 39 years. The average number of years of teaching experience was 18.8, with a standard deviation of 9.76. For this study, they used Gibson and Dembo’s (1984) shortened 16-item version of the TES, which was translated into Dutch and then calibrated using one-half of their sample. Because Brouwers and Tomic’s sample comprised such an experienced group of teachers, and our focus is on pre-service teachers, we will not describe their results in detail. Of greatest importance is their finding that none of their four hypothesized models provided an adequate fit to the data. Chi-squared values and other fit indices (AGFI, RMR, TLI, CFI, and PCFI) showed problems with the proposed measurement models. However, inspection of the modification indices suggested that a re-specified model might improve the fit of the model. Even after removing three poor items, CFA results based on the validation sample revealed an inadequately fitting model. In their concluding remarks, Brouwers and Tomic stated ‘in the present study it is concluded that this instrument, in its current state, is not suitable for obtaining precise and valid information about teacher efficacy beliefs’ (p. 78). In sum, two- and three-factor solutions yield similar factor pattern coefficients for the items of the TES. Modifications of the TES consist of rewording items to balance positive and negative statements to accommodate prospective teachers’ lack of teaching experience, and have added little clarity to understanding construct validity. Kushner’s rewording of items from the PE scale from past to future tense, did not lead to a better understanding of the measurement model for the TES. Kushner’s CFA results, however, Copyright © The British Psychological Society Reproduction in any form (including the internet) is prohibited without prior permission from the Society Teacher self-efficacy 695 were rather decisive in eliminating the model with revised wording from further consideration. Early on, Gibson and Dembo (1984) expressed concern about the TES and argued for the use of CFA procedures to evaluate the validity of the number of hypothesized dimensions of the TES. To date, the research community has yet to evaluate the goodness-of-fit of the proposed measurement models of the TES. Others have also raised concerns about the psychometric properties (Colardci & Fink, 1995; Guskey & Passaro, 1994; Henson, 2002; Soodak & Podell, 1996). Although Brouwers and Tomic (2003) extended the literature by employing CFA techniques, their sample included a very experienced group of practising teachers, whose beliefs about teaching efficacy may vary from those of pre-service teachers. The purpose of this investigation was to evaluate the validity of the proposed twoand three-factor models of the TES using modern CFA techniques. Additionally, the relationships among the constructs implied by theory will be evaluated using structural equation models (SEM). STUDY 1 Method Sample and setting Participants for this investigation were 387 prospective teachers recruited from a university located in the south-western region of the USA. The mean age of participants was 21.9. The majority of the participants were sophomores (83%), with the remaining 17% equally divided between freshmen, juniors, and seniors. Female students comprised 71% of the sample. Of the participants, 2.4% plan to teach at the preschool level, and 51.9%, 12.6%, 28.5%, plan to teach at K-5, middle school/junior high, and high school, respectively. The teacher preparation programme from which the participants were drawn consisted of a traditional sequence of university courses, field experience, and a semester-length student teaching experience. University students who are formally admitted into the teacher education programme complete a formal fieldwork experience during their second year in the programme. The college’s Office of Student Services places pre-service teacher candidates into one of the local schools for a 45-hour fieldwork experience. Pre-service teachers are placed with an experienced practising teacher, who serves as a model for the teacher candidate and oversees the pre-service teacher’s required fieldwork assignments. Pre-service teachers complete a fieldwork contract, time sheets, written assignments, and retain artifacts for their professional portfolio. Portfolios from the fieldwork experience are due in the Office of Student Services 2 weeks prior to the end of the academic term. At this university, students planning to become elementary school teachers major in education and declare a content area in a specific discipline. Students planning to teach in secondary education declare an academic major and minor and complete three semesters of professional education courses. In terms of demographic characteristics and educational context, this sample most closely resembles the sample studied by Woolfolk and Hoy (1990). Instrumentation Teacher efficacy beliefs were assessed using the 20-item version of the TES developed by Woolfolk and Hoy (1990). TES items were presented in a Likert scale format in which the Copyright © The British Psychological Society Reproduction in any form (including the internet) is prohibited without prior permission from the Society 696 Gypsy M. Denzine et al. students selected a number to indicate their level of agreement with each item (1 ¼ strongly disagree to 6 ¼ strongly agree). Additionally, a cover page contained questions concerning selected demographic characteristics (e.g. age, gender). All responses were collected anonymously. Items comprising the TES are presented in Table 1. Procedure The TES was administered to participants, as a group, in their undergraduate Educational Foundations and Educational Psychology class. Participation in the study was voluntary and participants did not receive remuneration or extra credit for their participation. Results Mean responses, standard deviations, and correlations among the items of the TES are presented in the Appendix. Goodness-of-fit for the two-factor and three-factor models described by Woolfolk and Hoy (1990) was evaluated using maximum likelihood estimation procedures in EQS/Windows (Bentler, 1998). Two-factor model Each item is hypothesized to have a non-zero loading on the factor designated in Table 1 (PE or TE) with independent unique variance, and the two factors are assumed to be correlated. The first step in evaluating the fit of the two-factor model is to check for redundancy by comparing the fit of the two-factor model relative to a one-factor model. Results are presented in Table 2. Although the two-factor model (Model 3) specified by Woolfolk and Hoy (1990) was a statistically significant improvement over the one-factor model (Model 2), the chi-squared test, non-normed fit index (NNFI), comparative fit index (CFI), and the root MSE of approximation (RMSEA) for the two-factor model indicate the fit of the model to the data is not acceptable. (See Bryant & Yarnold, 1998 for an overview of the various fit tests available.) Three-factor model The three-factor model of the TES (Model 4) specified by Woolfolk and Hoy (1990) retains the hypothesis concerning the composition of the TE scale; however, the PE scale was separated into two factors: personal efficacy for positive outcomes (PE þ ) and personal efficacy for negative outcomes (PE 2 ) as shown in Table 1. The threefactor model is identical to the two-factor model with the restriction that the correlation between the PE þ and PE 2 is 1.0, and is therefore nested under the two-factor model. Although the three-factor model is a statistically significant improvement over the two-factor model (see Table 2), the chi-squared statistic, NNFI, CFI, and RMSEA for the three-factor model of the TES also indicate that the fit of the three-factor model to the data is not acceptable. In sum, neither the two-factor or three-factor specifications of the TES measurement model provide an acceptable fit to TES item covariance matrix in this sample of prospective teachers. Discussion Evidence that the two-factor and three-factor models of the TES are not acceptable raises questions about the search for a statistically acceptable and theoretically meaningful Copyright © The British Psychological Society Reproduction in any form (including the internet) is prohibited without prior permission from the Society Teacher self-efficacy 697 Table 1. Measurement models of the Teacher Efficacy Scale Item No. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 Item When a student does better than usually, many times it is because I exert a little extra effort. The hours in my class have little influence on students compared to the influence of their home environment. The amount a student can learn is primarily related to family background. If students aren’t disciplined at home, they aren’t likely to accept any discipline. I have enough training to deal with almost any learning problem. When a student is having difficulty with an assignment, I am usually able to adjust it to his/her level. When a student gets a better grade than he/she usually gets, it is usually because I found better ways of teaching that student. When I really try, I can get through to most difficult students. A teacher is very limited in what he/she can achieve because a student’s home environment is a large influence on his/her achievement. Teachers are not a very powerful influence on student achievement when all factors are considered. When the grades of my students improve, it is usually because I found more effective teaching approaches. If a student masters a new concept quickly, this might be because I knew the necessary steps in teaching that concept. If parents would do more for their children, I could do more. If a student did not remember information I gave in a previous lesson, I would know how to increase his/her retention in the next lesson. If a student in my class becomes disruptive and noisy, I feel assured that I know some techniques to redirect him/her quickly. Even a teacher with good teaching abilities may not reach many students. Woolfolk and Hoy Two-factor model Woolfolk Re-specified and Hoy Three-factor Three-factor model model PE PE þ Omitted TE TE Omitted TE TE E-LOC TE TE Omitted PE PE 2 Omitted PE PE 2 Omitted PE PE þ OE PE PE 2 Omitted TE TE E-LOC TE TE E-LOC PE PE þ OE PE PE þ OE TE TE Omitted PE PE 2 SEB PE PE 2 SEB TE TE Omitted Copyright © The British Psychological Society Reproduction in any form (including the internet) is prohibited without prior permission from the Society 698 Gypsy M. Denzine et al. Table 1. (Continued) Item No. 17 18 19 20 Item If one of my students couldn’t do a class assignment, I would be able to accurately assess whether the assignment was at the correct level of difficulty. If I really try hard, I can get through to even the most difficult or unmotivated students. When it comes right down to it, a teacher really can’t do much because most of a student’s motivation and performance depends on his/her home environment. My teacher training program and/or experience has given me the necessary skills to be an effective teacher. Woolfolk and Hoy Two-factor model Woolfolk Re-specified and Hoy Three-factor Three-factor model model PE PE 2 SEB PE PE 2 Omitted TE TE E-LOC PE PE 2 Omitted Note. PE ¼ Personal Efficacy, TE ¼ Teaching Efficacy, PE þ ¼ Personal Efficacy for positive outcomes, PE 2 ¼ Personal Efficacy for negative outcomes, SEB ¼ Self-efficacy beliefs, OE ¼ Outcome expectations, E-LOC ¼ External locus-of-causality beliefs. Table 2. Fit indexes for alternative measurement models of the Teacher Efficacy Scale. Model x2 Woolfolk and Hoy (1990) measurement models 1. Independence model 1905.86* 2. One-factor model 1126.21* 3. Two-factor model 795.33* Difference between Model 2 and Model 3 330.88* 4. Three-factor model 549.25* Difference between Model 3 and Model 4 246.08* Respecified measurement model 5. Independence model 835.02* 6. Respecified three-factor measurement model 61.94* Difference between Model 5 and Model 6 773.08* Cross-validation of respecified measurement model 5. Independence model 372.29* 6. Re-specified one-factor measurement model 145.52* Difference between Model 5 and Model 6 226.77* 7. Re-specified two-factor measurement model 82.45* Difference between Model 6 and Model 7 63.07* 8. Respecified three-factor measurement model 35.97 Difference between Model 7 and Model 8 46.48* df x2/df NNFI CFI RMSEA 190 170 169 21 167 2 10.03 6.62 4.71 .38 .59 .44 .64 .171 .098 3.29 .75 .78 .077 1.94 .95 .96 .049 8.27 4.16 .57 .66 .156 2.42 .80 .85 .105 1.12 .98 .99 .032 45 32 13 45 35 10 34 1 32 2 Note. NNFI ¼ Non-normed fit index, CFI ¼ Comparative fit index, RMSEA ¼ Root mean squared error of approximation. * p , :05. Copyright © The British Psychological Society Reproduction in any form (including the internet) is prohibited without prior permission from the Society Teacher self-efficacy 699 specification of a measurement model for the TES items. One approach to improving model specification is to use modification indexes such as the multivariate Lagrange Multiplier (LM) test (for adding parameters) and the Wald W statistic for trimming parameters. The multivariate LM test associated with the three-factor model, for example, indicated the chi-squared statistic could be reduced approximately 473 points by estimating 34 additional parameters. The search for proper model specification based solely on modification indexes, however, is unlikely to identify the proper specification (Silvia & MacCallum, 1988). An alternative starting-point for developing a more satisfactory measurement model of the TES is to evaluate the items with respect to theoretical guidelines for constructing self-efficacy scales (Bandura, 1997, 2005). Self-efficacy beliefs are personal judgments about one’s generative capability for cognitive, behavioural, social, and emotional actions that vary in terms of their level (i.e. task demands), generality (range of activities) and strength (durability; Bandura, 1986, 1997). Items assessing self-efficacy are written in a form that expresses a belief about one’s capability to execute some action (e.g. ‘how certain are you that you can quickly redirect a disruptive student to the lesson you are teaching’?). Respondents are asked to rate the strength of their beliefs to perform the action on a 100-point scale with 10-point increments ranging from 0 (certain I cannot do) to 50 (moderately certain I can do) to 100 (certain I can do). It is important to distinguish self-efficacy beliefs from outcomes and the expectations for certain outcomes. In the item above, the respondent is asked to evaluate their capability for redirecting a disruptive student. Redirecting the disruptive student is an action, not an outcome. Outcome expectations refer to judgments about the probable consequence(s) of a specific action and may include physical effects, social reactions, and/or self-evaluative reactions (Bandura, 1997). An item that reads, ‘when I redirect a disruptive student to the lesson they will learn the concept I am teaching’, reflects the expectancy of a specific outcome for a particular action. This relation between responses and outcomes has been referred to as ‘responseoutcome expectancy’ by Bandura (1977) and as ‘action-outcome expectancy’ by Heckhausen (1977). Social cognitive theory also distinguishes outcome expectations from the locus-of-causality construct (Heider, 1958; Rotter, 1966; Weiner, 1986). For example, endorsing an item that reads, ‘teachers are the most important influence on student achievement’ reflects an internal locus of outcome causality, whereas ‘the home environment is the most important influence on student achievement’ reflects an external locus of causality. Unlike outcome expectations, items assessing locus-ofcausality beliefs are more general in nature items. The examples given, specific actions of the teacher, or elements of the home environment that might affect student achievement are global. Similarly, the specified outcome, student achievement, is also a global outcome. Re-specification of the TES measurement model Two criteria were applied to the re-specification of the TES measurement model in an attempt to align the items with self-efficacy theory. Each item was first evaluated on rational grounds for compatibility with the theoretical definitions of: (a) self-efficacy beliefs, (b) outcome expectations, or (c) locus of causality. If an item was judged to be consistent with one of these theoretical definitions, it was retained for further consideration. Next, the location of items was identified. Items located on a common factor with a squared factor pattern coefficient greater than .20 were retained in the re-specified measurement model of the TES. Copyright © The British Psychological Society Reproduction in any form (including the internet) is prohibited without prior permission from the Society 700 Gypsy M. Denzine et al. Four TES items in Table 1 (V6, V14, V15, and V17) were judged as being the most consistent with the theoretical definition of self-efficacy beliefs. Although these items ask students to make a judgment about their capabilities (e.g. ‘: : :I would know how to increase his/her retention: : :’), the items do not ask for judgments about their capability to accomplish a specific action (e.g. ‘: : :I know how to use advance organizers to increase his/her retention: : :’). Thus, there is some ambiguity about whether the judgment involves an action or an outcome. Each of these items is located on the PE factor specified by Woolfolk and Hoy (1990) with factor pattern coefficients of .18, .73, .80, and .65, respectively. Despite the apparent similarity of the items, the magnitude of the factor pattern coefficient for V6 is small in both absolute and relative terms. Moreover, Item V6 is associated with eight standardized residuals with an absolute value greater than .10, whereas the other items are associated with two, and at most three, standardized residuals with absolute value greater than .10. Thus, Item V6 was eliminated and the measurement model for self-efficacy beliefs (SEB) was re-specified to include items V14, V15, and V17. In sum, only three items were judged as potential indicators of self-efficacy beliefs about teaching. One item refers to classroom management and the remaining two items refer to instructional capabilities. None of the items affords measurement of the level or generality of self-efficacy beliefs. Analysis of the TES items for consistency with the definition of outcome expectations identified items V1, V7, V11, and V12 as the best candidates for the re-specified measurement model. Item V1, however, is less precise with regard to the specification of the outcome (‘when a student does a little better: : :’) in relation to a performance attainment (exerting a little extra effort) than item V12, for example, which specifies concept mastery as an outcome of knowing the steps for teaching a concept. In view of the ambiguous outcome and performance attainment, item V1 was eliminated from further consideration. The remaining items (V7, V11, and V12), originally specified on the PE factor by Woolfolk and Hoy (1990), exhibit moderate to large magnitude factor pattern coefficients (.65, .74, and .61, respectively) in the present study. Insofar as the outcomes are not linked to a specific action, it could be argued that items V7, V11, and V12 measure a persons’ belief in an internal locus-of-causality (Guskey, 1998; Guskey & Passaro, 1994). Tentatively, these items were included in the re-specified measurement model as hypothesized indicators of outcome expectations (OE). Among the remaining items of the TES, six items (V3, V4, V9, V10, V16 and V19) were considered potential indicators of beliefs about the locus-of-causality in student achievement. Specifically, the items reflect an external locus-of-causality, the influence of the students’ family background or home environment. Only four (V3, V9, V10 and V19) of these six items, however, had squared factor pattern coefficients greater than .20. Hence, only these four items were included in the re-specified model as possible indicators of pre-service teachers’ external locus-of-causality (E-LOC). In sum, theoretical and empirical criteria were applied to the items of the TES to re-specify a measurement model that is hypothesized to be more closely aligned with the theoretical constructs of self-efficacy beliefs (SEB), outcome expectations (OE), and external locus-of-causality (E-LOC). Only 10 items were retained from the original 20-item scale (See Table 1). Because the re-specified measurement model is based on post hoc analysis, it was evaluated in an independent sample of pre-service teachers. Copyright © The British Psychological Society Reproduction in any form (including the internet) is prohibited without prior permission from the Society Teacher self-efficacy 701 STUDY 2 Evaluation of the validity of the re-specified measurement model is accomplished in two steps. The first step consists of fitting the re-specified model to the data as a first-order model with three correlated factors. If the model is an acceptable fit to the data, an equivalent model with a causal structure can be fit to the data to evaluate relationships among the constructs predicted by theory. Social cognitive theory (Bandura, 1997), for example, posits the relationship between efficacy beliefs and outcome expectations is mediated by the structure of the contingencies, actual or perceived, between actions and outcomes in a given domain. When outcomes are contingent upon the quality of actions, efficacy beliefs account for most of the variance in outcome expectancies. In contrast, when outcomes are not contingent upon the quality of actions, self-efficacy beliefs become independent of outcome expectations. Method Participants Participants for this investigation were 131 prospective elementary teachers recruited from the same university in Study 1. None of the students in the second study participated in the first study. All of the students in this sample were enrolled in a required course for teacher licensure, in which they complete a practicum experience in an elementary school classroom setting. Experiences include teaching observation, small group interaction, and one-on-one assistance to children. Students included in this sample ranged in age from 20 to 53, with a mean age of 22.8. Of the sample, 87% fell within the age range 20–23. A majority of participants were in their senior (61%) or junior (33%) year in college, with the remaining 6% either in a postgraduate certification programme or had provided insufficient data on their college level. 93.9% (N ¼ 123) of the sample were female, 85.5% were White, 3.1% were Native American, 6.9% were Hispanic, and 3.1% self-identified as multiracial. All participants were admitted to the elementary education programme. In contrast to the participants in Study 1, Study 2 participants were further along in their educational programme, had more supervised teaching experience and were, on average, 11 months older. Instrumentation The instrument completed by participants in Study 2 was identical to the instrument used in Study 1. Procedure The TES was administered to participants, as a group, in their usual classroom setting. Participation in the study was voluntary and participants did not receive remuneration or extra credit. All responses were collected anonymously. Results and discussion Correlations, means and standard deviations for all TES items are presented in the Appendix. Although data for all 20 items of the TES are presented in the Appendix, the CFA analysis is based only on the 10 items specified in Table 1. The first step in evaluating the fit of the re-specified three-factor is to check for redundancy by comparing the fit of the three-factor model relative to a two-factor model that combines Copyright © The British Psychological Society Reproduction in any form (including the internet) is prohibited without prior permission from the Society 702 Gypsy M. Denzine et al. the external locus-of-causality (E-LOC) and outcome expectancy (OE) scales and a onefactor model. The results are shown in Table 2. Although the one-factor model is a statistically significant improvement over the independence model, the chi-squared test and fit indexes indicate that the one-factor model is unacceptable fit to the data. Similarly, the re-specified two-factor model is a statistically significant improvement over the one-factor model; however, the chi-squared test, NNFI, CFI, and RMSEA lead to the rejection of the model as an acceptable fit to the data. Finally, the CFA results in Table 2 show the three-factor model is a statistically significant improvement over the two-factor model. Moreover, the chi-squared test, NNFI, CFI, and RMSEA all provide evidence the model is an acceptable fit to the data. Standardized and unstandardized estimates of the model parameters are presented in Fig. 1 and Table 3, respectively. Inspection of the unstandardized solution reveals that all indicators have statistically significant factor pattern coefficients on the re-specified constructs. The standardized solution further reveals the factor pattern coefficients are moderate to large in magnitude, and the relationships among all latent constructs are positive and statistically significant. This simple correlated factors measurement model, however, does not evaluate the critical predications of social cognitive theory. It would be helpful in this context to specify a model that estimates the relative contributions of the external locus-of-causality in achievement and self-efficacy beliefs to the prediction of outcome expectancies. The need for such specificity was stated by Skinner (1996), who argued this is a proliferation of constructs related to ‘control’, which has been costly to the understanding of control in theoretical, empirical, and practical terms. The path model in Fig. 2 is mathematically identical to the model specified in Fig. 1 (cf. Lee & Hershberger, 1990). The chi-squared value, fit indexes, and factor pattern Figure 1. Re-specified three-factor measurement model of the Teacher Efficacy Scale. Copyright © The British Psychological Society Reproduction in any form (including the internet) is prohibited without prior permission from the Society Teacher self-efficacy 703 Table 3. Estimates of the measurement model for the Revised Teacher Efficacy Scale Latent variable and measure SEB – self-efficacy beliefs V14 V15 V17 OE – outcome expectations V7 V11 V12 E-LOC – external locus-of causality beliefs V3 V9 V10 V19 Latent variable covariances SEB, OE SEB, E-LOC OE, E-LOC Unstandardized estimate Standard error z-statistic 0.827 0.146 5.66* 0.867 0.145 5.98* 0.791 0.113 7.00* 0.795 0.115 6.91* 0.963 0.182 5.29* 0.826 0.918 0.160 0.165 5.16* 5.56* 0.357 0.326 0.263 0.090 0.091 0.096 3.97* 3.58* 2.74* Fixed Fixed Fixed Variances 0.561 0.630 0.392 0.522 0.798 0.477 0.438 0.514 0.723 1.111 0.892 0.899 0.758 *p , :05. coefficients of the indicators for the model in Figs. 1 and 2 are identical. What is different about the model in Fig. 2 is that it reflects the causal structure specified by self-efficacy theory assuming valid measurement of the constructs. The magnitude of the relationship between self-efficacy beliefs (SEB) and outcome expectations (OE), for example, should depend on the magnitude of relationship between the respondents’ external locus-of-causality (E-LOC) and outcome expectations (OE). Specifically, we are interested in testing the following structural relations among the hypothesized constructs (Fs) of the re-specified model for consistency with predictions from social cognitive theory: F ðSEBÞ ¼ b1 £ F ðE2LOCÞ ; and F ðOEÞ ¼ b2 £ F ðSEBÞ þ b3 £ FðE2LOCÞ Figure 2. A structural model of the Teacher Efficacy Scale. Copyright © The British Psychological Society Reproduction in any form (including the internet) is prohibited without prior permission from the Society 704 Gypsy M. Denzine et al. Social cognitive theory predicts that b2 . 0 as b3 ! 0. Predictions concerning b1 are less precise, although Bandura (1997) argues that beliefs ‘about whether one can produce certain actions (perceived self-efficacy) cannot, by any stretch of the imagination, be considered the same as beliefs about whether actions affect outcomes (locus of control)’ (p. 20). Moreover, self-efficacy beliefs and global perceptions about the locus-of-causality are differentially related to successful functioning across many domains (Smith, 1989; Taylor & Pompa, 1990). Hence, a reasonable hypothesis is that b1 ¼ 0. It is important to note that in the present study, we are dealing with perceived control (i.e. an individual’s beliefs about how much control is available) rather than objective control or experiences of control (Skinner, 1996). A second basic premise important to note is that the previously mentioned hypothesis is dealing with a means– ends type of relation. Due to the complex and complicated nature of the use of control terms in research, Skinner (1996) has argued researchers must be explicit about agents, means, and ends of control. In the present study, the agent is the individual pre-service teacher. The means refers to the pathway through which control is exerted (i.e. direct pathway to outcome expectations and unrelated to self-efficacy beliefs). Ends refer to the desired or undesired outcomes over which control exerted (e.g. student achievement). Bandura (1997) contended that even in cases whereby the individual believes that outcomes can be influenced by one’s behaviour or efforts, they will not attempt to exert control unless they also believe they are capable of producing the requisite responses themselves. We also note in the present study that we are referring to behavioural rather than cognitive control or responses. Standardized estimates of the relationships among the latent constructs for the equivalent model are shown in Fig. 2. As the structural model shows, outcome expectations are independent of external locus-of-causality beliefs (b3 ¼ 0). Hence, we would expect b2 . 0. Consistent with social cognitive theory, the path coefficient between self-efficacy beliefs and outcome expectations is positive, moderate in magnitude, and statistically significant. Contrary to the prediction of social cognitive theory, however, external locus-of-causality beliefs and self-efficacy beliefs are not unrelated, b1 . 0. Indeed, there is considerable overlap in the two constructs. Approximately 25% of the variance in the constructs is common variance. Moreover, the direction of the relationship is opposite of what would be expected between external locus-of-causality beliefs and self-efficacy beliefs. In sum, the magnitude and direction of the relationship between these two latent variables casts doubt on the validity of the constructs as locus-of-causality and/or self-efficacy. GENERAL DISCUSSION Originally developed by Gibson and Dembo (1984), and revised by Woolfolk and Hoy (1990), the TES was designed to measure teachers’ beliefs about (a) their ability to influence student learning, labelled PE scale, and (b) outcome expectations, labelled TE scale. Other investigators, however, have argued that the TES represents three dimensions of teachers’ beliefs. Guskey (1981), for example, interpreted the PE scale as composed of positive and negative dimensions of the same underlying construct: personal responsibility for positive (PE) and negative (PE) student outcomes. In contrast, Soodak and Podell (1996) argued the three dimensions of the TES reflect independent dimensions of personal efficacy, outcome efficacy, and teaching efficacy. Results from a confirmatory factor analysis of the TES, however, lead to the rejection of Copyright © The British Psychological Society Reproduction in any form (including the internet) is prohibited without prior permission from the Society Teacher self-efficacy 705 the two-factor and three-factor measurement models. Thus, the interpretation of the hypothesized factor structures of the TES is moot. A re-specified measurement model for the TES was derived from the application of rigorous theoretical and empirical criteria. The re-specified measurement model retained 10 of the 20 original items hypothesized as indicators of three latent variables: self-efficacy beliefs (SEB), outcome expectations (OE), and an external locus of causality (E-LOC). Although the three-factor measurement model was an acceptable fit to the data, the structural relations among the constructs were not consistent with the predictions of social cognitive theory. Whereas, social cognitive theory specifically posits self-efficacy beliefs and locus-of-causality beliefs are theoretically unrelated constructs (Bandura, 1997), and whereas other investigators have found no connection between self-efficacy beliefs and locus-of-causality beliefs (Smith, 1989; Taylor & Pompa, 1990), results from this investigation are inconsistent with theory and evidence about the relationship between locus-of-causality beliefs and self-efficacy beliefs. The hypothesized constructs of self-efficacy beliefs (SEB) and external locus-of-causality show a moderate positive statistically significant association. Approximately 25% of the variance in the two constructs is common variance. In sum, the results of this investigation provide the empirical evidence for arguments that the adoption of the TES as a measure of teachers’ self-efficacy was premature (Gibson & Dembo, 1984; Henson, 2001, 2002). Perhaps the most important implication of the present study is that the results call into question the interpretation of a large body of data involving the TES. Although studies using the TES may have identified important relationships between the TES and aspects of teaching and learning, we would conclude on the basis of the findings presented here that the previously reported relationships are questionable. Given the problems associated with the TES, we suggest the abandonment of previous evidence rather than a re-analysis of the data collected from the use of the TES. One alternative interpretation of the data is that problems with the validity of the TES as a measure of self-efficacy beliefs about teaching is restricted to pre-service teachers. That is, the measure is valid in the population of experienced teachers, but not preservice teachers. There are theoretical and empirical arguments against this alternative interpretation. First, to claim that pre-service teachers have no basis for making judgments about their capabilities in various teaching situations is unwarranted: there is no stricture in the tenets of social cognitive theory that would preclude a novice from making accurate judgments about his or her capabilities in any domain of functioning. Naı̈vety would be reflected in the mean structure (i.e. lower or higher mean scores for pre-service teachers than experience teachers) of the TES items, not their covariance structure. Second, Guskey and Passaro (1994) reported invariance in the TES item variance covariance matrix between experienced and pre-service teachers. In sum, there is little support for the alternative interpretation that the results of the present investigation are peculiar to pre-service teachers. The findings from the present study corroborate Brouwers and Tomic’s (2003) findings, which were found in their study based on an experienced sample of teachers, that the TES is not an adequate scale for obtaining precise and valid information about teacher efficacy beliefs. Recently, new instruments for measuring teachers’ self-efficacy beliefs have emerged in the literature (Tschannen-Moran & Hoy, 2001). The items of the instrument, Teachers’ sense of efficacy scale (originally titled the Ohio state Teacher Efficacy Scale) are based on a subset of items that accompany an unpublished manuscript providing guidelines for the construction of self-efficacy scales (Bandura, 1990). The items were specifically Copyright © The British Psychological Society Reproduction in any form (including the internet) is prohibited without prior permission from the Society 706 Gypsy M. Denzine et al. constructed to measure teachers’ capabilities in seven domains of functioning: efficacy to influence decision-making, efficacy to influence school resources, instructional efficacy, disciplinary efficacy, efficacy to enlist community involvement, efficacy to create a positive school climate, and efficacy to enlist parental involvement. Investigators, however, failed to find evidence for the originally hypothesized dimensions of the new instrument (Tschannen-Moran & Hoy, 2001). The strategy of abandoning the a priori dimensions discerned from a careful analysis of the capabilities necessary to succeed in a domain of functioning in favour of re-labelling the scales on the basis of factor pattern coefficients from exploratory factor analysis places this instrument at risk for psychometric problems similar to those underlying the TES. References Allinder, R. M. (1995). An examination of the relationships between teacher efficacy and curriculum-based measurement and student achievement. Remedial and Special Education, 16, 247–254. Armor, D., Conry-Oseguera, P., Cox, P., King, N., McDonnell, L., Pascal, A., Pauly, E., & Zellman, G. (1976). Analysis of the school preferred reading program in selected Los Angeles minority schools (Report No. R-2007-LAUSD). Santa Monica, CA: The Rand Corporation. Ashton, P. (1984). Teacher efficacy: A motivational paradigm for effective teacher education. Journal of Teacher Education, 35, 28–32. Ashton, P., & Webb, R. B. (1986). Making a difference: Teachers’ sense of efficacy and student achievement. New York: Longman. Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review, 84, 191–215. Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall. Bandura, A. (1990). Multidimensional scales of perceived academic efficacy. Sanford, CA: Stanford University. Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. New York: Freeman. Bandura, A. (2005). Guide for constructing self efficacy scales. Retrieved from: http://www.des. emory.edu/mfp/self-efficacy.html#instruments. Bentler, P. M. (1998). EQS for Windows (Version 5.7b) [Computer Software]. Encino, CA: Multivariate Software. Berman, P., & McLaughlin, M. W. (1977). Federal programs supporting educational change: Vol. VII. Factors affecting implementation and continuation. Santa Monica, CA: The Rand Corporation. Brouwers, A., & Tomic, W. (2003). A test of the factorial validity of the Teacher Efficacy Scale. Research in Education, 69, 67–80. Bryant, R. B., & Yarnold, P. R. (1998). Principal-components analysis and exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis. In L. G. Gimm & P. R. Yarnold (Eds.), Reading and understanding multivariate statistics (pp. 66–99). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. Colardci, T., & Fink, D. R (1995, April). Correlations among measures of teacher efficacy: Are they measuring the same thing? Paper presented at the annual meeting of the American Educational Research Association, San Francisco. Deemer, S. A., & Minke, K. M. (1999). An investigation of the factor structure of the teacher efficacy scale. Journal of Educational Research, 93, 3–10. Emmer, E. T., & Hickman, J. (1991). Teacher efficacy in classroom management and discipline. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 51, 755–765. Copyright © The British Psychological Society Reproduction in any form (including the internet) is prohibited without prior permission from the Society Teacher self-efficacy 707 Gibson, S., & Brown, R. (1982, March). The development of a teacher’s personal responsibility/self-efficacy scale. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the American Educational Research Association, New York. Gibson, S., & Dembo, M. H. (1984). Teacher efficacy: A construct validation. Journal of Educational Psychology, 76, 569–582. Guskey, T. R. (1981). Measurement of the responsibility teachers assume for academic successes and failure in the classroom. Journal of Teacher Education, 32, 44–51. Guskey, T. R. (1998, April). Teacher efficacy measurement and change. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the American Educational Research Association, San Diego, CA. Guskey, T. R., & Passaro, P. D. (1994). Teacher efficacy: A study of construct dimensions. American Educational Research Journal, 31, 627–643. Heckhausen, H. (1977). Achievement motivation and its constructs: A cognitive model. Motivation and Emotion, 1, 283–329. Heider, F. (1958). The psychology of interpersonal relations. New York: Wiley. Henson, R. K. (2001). Teacher self-efficacy: Substantive implications and measurement dilemmas. Keynote address presented at the meeting of the Educational Research Exchange, College Station, TX, USA. Henson, R. K. (2002). From adolescent angst to adulthood: Substantive implications and measurement dilemmas in the development of teacher efficacy research. Educational Psychologist, 37, 137–150. Henson, R. K., Kogan, L. R., & Vacha-Haase, T. (2001). A reliability generalization study of the teacher efficacy scale and related instruments. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 61, 404–420. Hoover-Dempsey, K. V., Bassler, O. C., & Brissie, J. S. (1987). Parent involvement: Contributions of teacher efficacy, school socioeconomic status, and other school characteristics. American Journal of Educational Research, 24, 417–435. Klein, R. (1996). Teacher efficacy and developmental math instructors at an urban university: An exploratory analysis of the relationships among personal factors, teacher behaviors, and perceptions of the environment. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Akron, Ohio, USA Kushner, S. N. (1993, February). Teacher efficacy and preservice teachers: A construct validation. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Eastern Educational Research Association, Clearwater Beach, FL, USA. Lee, S., & Hershberger, S. (1990). A simple rule for generating equivalent models in covariance structure modeling. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 25, 313–334. Midgley, C., Feldlaufer, H., & Eccles, J. S. (1989). Changes in teacher efficacy and students self- and task-related beliefs in mathematics during the transition to junior high school. Journal of Educational Psychology, 81, 247–258. Pajares, F. (1992). Teachers’ beliefs and educational research: Cleaning up a messy construct. Review of Educational Research, 62, 307–332. Rotter, J. B. (1966). Generalized expectancies for internal vs. external control of reinforcement. Psychological Monographs, 80, 1–28. Silvia, E. S. M., & MacCallum, R. C. (1988). Some factors affecting the success of specification searches in covariance structure modeling. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 23, 297–326. Skinner, E. A. (1996). A guide to constructs of control. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 71, 549–570. Smith, R. E. (1989). Effects of coping skills training on generalized self-efficacy and locus of control. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 56(2), 228–233. Soodak, L. C., & Podell, D. M. (1996). Teacher efficacy: Toward the understanding of a multifaceted construct. Teaching and Teacher Education, 12, 401–411. Soodak, L. C., & Podell, D. M. (1997). Efficacy and experience: Perceptions of efficacy among preservice and practicing teachers. Journal of Research and Development in Education, 30, 214–221. Copyright © The British Psychological Society Reproduction in any form (including the internet) is prohibited without prior permission from the Society 708 Gypsy M. Denzine et al. Taylor, K. M., & Popma, J. (1990). An examination of the relationships among career decisionmaking, self-efficacy, career salience, locus of control, and vocational indecision. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 37(1), 17–31. Tschannen-Moran, M., & Hoy, A. W. (2001). Teacher efficacy: Capturing an elusive construct. Teaching and Teacher Education, 17, 783–805. Tschannen-Moran, M., Hoy, A. W., & Hoy, W. K. (1998). Teacher efficacy: Its meaning and measure. Review of Educational Research, 68, 202–248. Weiner, B. (1986). An attributional theory of motivation and emotion. New York: SpringerVerlag. Woolfolk, A., & Hoy, W. K. (1990). Prospective teachers’ sense of efficacy and beliefs about control. Journal of Educational Psychology, 82, 81–91. Received 27 August 2003; revised version received 19 August 2004