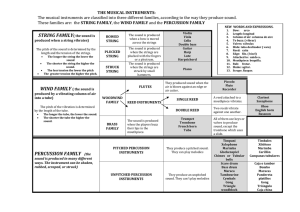

Green Industrial Policy Promoting Competitiveness and Structural Transformation Core reading Module 4: Green Industrial Policy Instruments 1 Introduction The process of green industrialization is a complex undertaking. It calls for a holistic and integrated approach to policymaking across the economic, social, and environmental sectors. At the same time, the type of transformative change required to instigate a green industrial policy naturally brings with it a certain degree of uncertainty and risk. This change may not occur voluntarily, and a range of “carrots” and “sticks” – i.e. incentives and deterrents – will therefore need to be employed to trigger the actions necessary for green structural change. This change will necessarily be government-led, and public policy, as a shaper and driver of economic and societal transformation, should therefore sit at the heart of the process. Public policy may be implemented through a range of mutually reinforcing policy instruments, to meet the increased need of green industrial policy to build synergistic links across a range of thematic areas which bridge environmental, economic, and social concerns. The range of policy instruments should be drawn on to enhance value addition within sectors in a radically different way. For example, a comprehensive circular economy strategy may feature taxation for landfill, carbon footprint, and product and materials, include VAT exemptions, feed-intariffs, and public procurement programmes, and finally promote R&D for eco-design programmes [1]. To this end, policy instruments are constantly evolving in response to the demand for systemic solutions to the complex challenges of our time. At the same time, governments are adapting and refining policy instruments according to their past experiences, as well as their capabilities, needs, and level of industrialisation. Finally, it should be noted that in practice, the boundaries between instrument categories are not always clearly defined. Instruments often possess the features of more than one category. For example, governments may mandate emission quotas, but introduce tradable permits to enhance 1 efficiency. Voluntary standards may also form part of the gradual introduction of regulation with increasing degrees of compulsion over time. Indeed, governments are now increasingly employing instruments from more than one category, as part of a strategic and coordinated mix of several instrument types. The specific design of the green industrial policy will depend on the issue to be addressed, and on the specific country circumstances at play. 2 A policy instrument framework Economic/ Fiscal (Marketbased) Commandand-Control Voluntary/ Informational 2 Figure 1. Categories of policy instruments There are three broad categories of policy instruments. Regulatory instruments (“command-andcontrol”) encompass instruments related to norms and standards, environmental liability, and control and enforcement. Regulation, provided it is strictly enforced, has a strong steering impulse. The steering impulse of voluntary or informational instruments, on the other hand, is soft. Market-based instruments (“economic/fiscal”) lie somewhere in between, with their steering impulse depending on the scale of market manipulation and the responsiveness (i.e. the elasticity) of supply and demand. Market-based instruments typically have a good degree of dominance in the instruments mixes of green industrial policy. The matrix on the following page highlights the various types of instruments that can be used for green industrial policymaking, and identifies where each of these sit in the spectrum of steering impulse: for instance, whether they are “soft” or “hard”, and whether they reward or penalise, motivate or support. Recommended reading Luken, R. A. and Clarence-Smith, E., “Green Industrialization in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Guide for Policy Makers” (2019) UONGOZI Institute. https://www.africaportal.org/publications/greenindustrialization-sub-saharan-africa-guide-policy-makers/. Cosbey, A., Wooders, P., Bridle, R. and Casier, L., “In with the Good, Out with the Bad: Phasing Out Polluting Sectors as Green Industrial Policy” in PAGE, Green Industrial Policy: Concept, Policies, Country Experiences (2017) UNEP and DIE, p. 72, for an overview of the spectrum of types of disruptive green industrial policies. https://www.unpage.org/files/public/green_industrial_policy_book_aw_web.pdf UNIDO, “A Shift in the Production Paradigm” (2019) Making It Magazine. An interview with Manuel Albaladejo. https://www.makingitmagazine.net/?p=10886 Figure 2. A policy matrix for green industrial policies 3 Source: UNIDO, Green Industry: Policies for Supporting Green Industry (2011) 3 Command-and-control instruments Regulatory or “command-and-control” instruments typically form the basis of environmental policy frameworks in both developed and developing countries. Regulations address a broad range of environmental problems and are particularly useful in addressing those issues that can be easily identified, monitored, and enforced, such as point sources of pollution. They also provide certainty and clarity for administrators, and businesses [2]. Generally, regulation consists of four main activities: (i) standard-setting; (ii) issuance of licenses; (iii) compliance monitoring; and (iv) enforcement in cases of non-compliance. The combined purpose of these four activities is to encourage and guide conduct that is favourable to the environment, or to prohibit conduct that is detrimental [3]. For example, a review of Ghana’s environmental regulations recommended that the Environmental Protection Agency should expand its permits (i.e. licensing) scheme to include all medium-sized and large enterprises. Currently, it has provided permits to only 250 to 300 enterprises, out of an estimated population of 500 to 600 medium-sized and large enterprises [3]. Similarly, Nigeria has a comprehensive range of strict environmental quality and pollutant discharge standards that are in line with those put forward in the World Bank guidelines, but the problem of limited enforcement remains. Only in the case of Lagos state is there a noticeable enforcement effort [3]. Flexible, well-designed standards and regulations can also be a short-term stimulus for innovation and technology diffusion by creating a demand for products and services. However, poorly designed regulations can also have the opposite effect, and stifle longer-term technological innovation. In general, regulatory instruments are less economically efficient than market-based instruments, and often have significant informational requirements for their effective design. They can also be complex to administer, although again this depends largely on the way in which they are structured. However, in practice the distinction between direct regulations and market-based or economic instruments is often blurred. Any system of economic instruments usually requires appropriate legislative or regulatory backing. Regulations should therefore form part of a mix of policy instruments, and be supported by an integrated overarching legal framework. Germany’s Energy Conservation Regulations Germany’s EnEV (Energy Conservation Regulations) 2013 represent an encompassing example of “command-and-control” regulations, which also draw on a range of complementary instruments to leverage their impact. They also highlight a stepwise tightening of construction law to a carbon neutral standard by 2021, whereby standards are incrementally introduced and tightened over time. 4 Financial incentives to comply with regulations and voluntary mechanisms are provided in the form of subsidy programmes offered by the public bank, Kreditanstaltfür Wiederaufbau (KfW). These programmes offer support for the refurbishment and construction of new buildings, and for heating with renewable energy. The government’s 2004 CO2 Reduction Programme includes two subsidised loan schemes: the KfW programme for energy efficient refurbishment, and the KfW programme for energy efficient new buildings. Grants and loans are staggered according to the degree of energy efficiency: the more energy efficient the building is, the higher the grant and the more favourable the repayment conditions for loans. This approach covers the whole range of technically feasible market options, and is regularly revised to increase the required energy efficiency standards. Preferential loans with low-interest rates for energy efficiency can be combined with loans for a new heating system based on renewable energies. Information-based programmes complement the policy package, including the mandatory energy performance certificate for buildings, and the targeted promotion of jobs and expertise related to energy efficiency. Various information and trust-building measures for homeowners, tenants, experts, and the construction industry support knowledge exchange and provide security for stakeholders in the market. The German energy efficient building programme has had a positive impact on energy consumption, regional value chains, and investment dynamics in the sector. The incremental introduction and tightening of regulations, accompanied by research and model projects, have led to substantial reductions in primary energy consumption over time. Source: Kemp, R. and Never, B., “Developing Green Technologies and Phasing Them In” in PAGE, Green Industrial Policy: Concept, Policies, Country Experiences (2017) UNEP and DIE, pp. 87-101. https://www.unpage.org/files/public/green_industrial_policy_book_aw_web.pdf 4 Market-based instruments Market-based or economic instruments are designed to price the use of environmental resources and the emission of pollutants. Such instruments incorporate the “hidden” costs of production and consumption in a cost-effective way, and represent an effective means by which to signal environmental costs while leaving it to competitive market forces to find the most efficient technological and organisational solutions. Some examples include taxes, charges, subsidies, incentives and tradable permits, and liability and compensation schemes, while they may also extend to environmental fiscal reform. This entails the removal of support or subsidies that are harmful to the environment, such as tax exemptions for kerosene or subsidies for coal. 5 Market-based instruments can be employed to achieve a range of policy objectives, which can be broken down into three broad categories: • Benefitting the environment • Raising fiscal revenues • Increasing fiscal efficiency and competitiveness In terms of the developing country context, the prevailing renewable energy-related policies in SubSaharan African countries are fiscal incentives. These include tax reductions, public investments, low-interest loans, and grants. Tax reductions – the most widespread incentive – require no additional budget allocation (but do imply a budget loss), fewer administrative procedures, and minimal regulatory supervision compared to other support policies [3]. More broadly, it has been argued that political economy constraints in developing countries are likely to keep carbon and other pricing measures at a low level. A high incidence of market failures has instead led to these countries adopting a greater number of non-price instruments (e.g. regulations) than in developed countries. Such non-price instruments and infrastructure programs are favoured as the most effective tools for achieving these objectives within developing countries, as they are seen as being more credible than any long-term carbon price-signal [4]. Success factors for implementing economic or market-based instruments (MBIs): Knowledge: Agencies responsible for implementing MBIs must have the technical knowledge necessary to formulate and implement these instruments. At the same time, polluters must possess the knowledge necessary for them to respond appropriately. Good governance: Legal structures and frameworks must define property rights adequately, and establish an authority to implement and enforce these. Competitive markets: If firms are operating under soft budget constraints, they will not respond as effectively to fiscal incentives. Financial and administrative capacity: Agencies implementing MBIs must have the capacity to initiate, monitor and enforce fiscal programmes. Flexibility in response: The private sector and individuals should have freedom of choice in how they are to meet the requirements under the MBI. Source: Sharp, B., “Institutions and Decision Making for Sustainable Development” (2002) New Zealand Treasury Working Paper 02/20, as cited in UNIDO, Green Industry: Policies for Supporting Green Industry (2011) p. 67. Environmental taxes and charges Environmental taxes may operate within discharge limitations in order to make the polluting firm pay for the discharges from its facility, even though they may be within regulatory limits. In this way, taxes 6 help to ensure that prices reflect the negative environmental impacts and costs of various products and processes that are not included in the market price. At the same time, placing a cost on the discharge of wastes and emissions creates an incentive for the producer to become more efficient, and to reduce the intensity of their resource use and pollution [2]. Material input taxes can also be an important tool for increasing resource efficiency [5]. Such taxes are a means of encouraging the more efficient use of resources, as well as fostering eco-innovations to develop more material efficient production technologies and less material-intensive products. Naturally, these have to be designed in a careful manner to ensure that they have the desired effect and do not instead lead to undesired resource substitutions. Emissions into the atmosphere, for instance, should ideally be charged at the same level in all countries because they are not confined to a specific location or country. The proceeds from such taxes can then be used to cross-subsidise the damage mitigation required as a result of adverse environmental impacts [2]. Examples of natural gravel tax Material input taxes have been introduced in a number of countries – including Sweden, Latvia, the United Kingdom, and Estonia – for the extraction of sand and gravel. The taxes are charged either per weight or by the volume of the extracted material. Sweden adopted its sand and gravel law in 1996, and in 2013 the tax generated SEK 146 million (approximately USD 22 million) in fiscal revenue for the government. The price of the tax is continuously monitored to ensure that it reflects an appropriate signal, with the Swedish Government increasing the price from 13 SEK to 15 SEK per ton in 2014. Source: PAGE, Practitioner’s Guide to Strategic Green Industrial Policy (2016) p. 82. Example of a pesticides tax in the agricultural sector in Denmark Effective as of July 1st 2013, Denmark’s pesticide tax is paid according to the significance of the impacts that a pesticide has on health, nature, and groundwater. The pesticides with the highest environmental and health impacts are the most heavily taxed, creating a strong economic incentive to use those pesticides with the lowest footprints. Industry response to the tax: The Danish Food and Agricultural Council (Association of Farmers and Food Industry) were pleased that the new tax was to be based on environmental and health impacts, and not on consumption, and thought it was positive that those pesticides with the highest impacts would be taxed the most heavily. They also emphasised the usefulness of having an indicator for monitoring pesticide impacts, in order to make it easier for farmers and industry to choose the pesticides that have the lowest footprints. However, the food industry expressed concern that some crops would suffer as a result of the new taxes, and it was also argued that the increased taxes could damage the industry’s competitiveness abroad, potentially leading to a loss of jobs. 7 Source: The Danish Ecological Council, “Fact sheet: Tax on Pesticides.” Green Budget Europe. https://green-budget.eu/wp-content/uploads/Tax-on-Pesticides_FINAL.pdf. Tradable permits Tradable permits have attracted growing attention in recent years as either a supplement or an alternative to environmental taxes. When designing an emissions trading system, two key variables relate to a) whether the authorities set an upper limit (cap) on the total amount of a substance (e.g. CO2) that can be emitted; and b) how the permits for emitting pollutants are initially to be allocated to the various enterprises involved. Once a tradable permit has been established, enterprises are then free to buy and sell permits among themselves, facilitating greater economy-wide costeffectiveness and allowing greater scope for technological innovation. The EU Emissions Trading Scheme represents one such example of a cap and trade system that is designed to reduce greenhouse emissions from industry sources [2]. Pricing Pricing influences spending and investment behaviour and is a powerful tool for determining patterns of economic growth. Market prices do not usually reflect ecological costs, so while decisions made on the basis of market prices may be economically efficient, they do not always generate positive environmental outcomes. Policies should therefore be aimed at increasing the prices for raw materials and energy in a way that accounts for the external environmental and social costs related to resource use [2]. Environmentally-motivated subsidies Subsidies are frequently used in policymaking to achieve an objective, such as stimulating investment in green production technologies, when this will have positive adoption spillovers. They can also complement the use of other market-based instruments, such as pollution taxes. Subsidy support can come in many different forms, including through tax provisions, loan guarantees, and charging below the cost price for public services, such as water, waste, and wastewater collection. However, subsidies can also generate inefficiencies and negative environmental effects, and should therefore be designed and applied with care. If not time-bound, subsidies can become “locked-in,” along with the (potentially inefficient) practices or technologies that they support. At the same time, providing subsidies to encourage compliance with direct regulations can result in significant economic distortions, and induce strategic behaviour among enterprises [6]. To this end, environmentally-motivated subsidies are deemed not to violate the polluter-pays principle when: • • They do not introduce significant distortions in international trade and investment They are limited to sectors which would otherwise have difficulties complying with environmental requirements 8 • They are limited to a well-defined transition period, and adapted too socio-economic problems associated with the implementation of a country’s environmental policy [2]. Special Fund for Energy Efficiency in SMEs Small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) face multiple barriers to initiating energy efficiency measures. Most SMEs lack the necessary technical knowledge to identify efficiency opportunities, as well as the options available to them to take advantage of these, including having the capacity to finance the adoption of energy-saving measures. As a result, in 2008 the German Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Energy (BMWi) – together with KfW, the public bank – established the “Special Fund for Energy Efficiency in SMEs” to tackle both the knowledge and financial barriers that such companies face. The programme has two components. First, it provides grants to SMEs to obtain advice and consultancy services regarding potential energy efficiency opportunities. Second, it offers low-interest loans to SMEs for investment in energy-saving measures. Overall, the programme represents an effective tool in supporting the energy efficiency efforts of SMEs in Germany. Source: IEA, “Special Fund for Energy Efficiency in SMEs” https://www.iea.org/policies/1769-special-fund-for-energy-efficiency-in-smes. 5 (2017). Voluntary and informational instruments Voluntary and informational instruments can be used to set more ambitious goals than regulations and, at the same time, entail less administrative costs. Today, there are a range of voluntary and informational instruments that can be employed by governments, business, and civil society to inter alia raise awareness about sustainability issues, incentivise more sustainable behaviour, and stimulate sustainable product and business development. In particular, information-based instruments can promote a wide range of activities and services, including environmental data collection and dissemination, development of indicators, environmental valuation, energy audits, education and training, eco-labelling or certification schemes, and public disclosure of enterprises’ environmental performance. Importantly, industry groups and civil society have also been active partners in the promotion and use of such tools. While voluntary and informational instruments are not exclusively the domain of industry, this represents a notable contrast to the traditional “command-and-control” types of regulation. 9 In terms of environmental management and energy use, the ISO14000 and ISO50001 standards have become important management tools for manufacturing enterprises that wish to green their existing industrial processes. By adopting these standards, companies can enhance buyer-supplier relationships while improving industrial competitiveness. They can also be employed as stand-alone activities, or included in a package of programmes for subsectors or SMEs. The Indian Green Building Council’s Green New Buildings Rating System The Green New Buildings rating system is a pertinent example of the non-regulatory options that may be employed to support a green industry. In India, the Green Building Council introduced the measurable ratings programme tool to aid and incentivise property developers to apply green concepts, and to reduce negative environmental impacts beyond those that are prescribed by law. Different levels of green building certification are awarded based on the credits earned. Certification levels range from “good practice” to “national excellence,” and finally to “global leadership.” Environment Management Systems (EMSs) Environment Management Systems (EMSs) are another example of a voluntary measure that can be used by both government and businesses to achieve improved environmental outcomes, while at the same time helping companies to comply with environmental regulations. EMSs are a type of management system which allow for external assessments to be made against a common standard. Source: PAGE, Practitioner’s Guide to Strategic Green Industrial Policy (2016) p. 82. In the context of the transition towards a green economy, there has now also been a shift from the sale of products to the sale of services. Tools such as chemical leasing (see below) fall into this category. Ideally, such tools are combined with other measures to form more powerful packages for greening industry. Chemical leasing Chemical leasing is a service-oriented business model that shifts the focus from increasing the sales volume of chemicals towards a value-added approach. Under a chemical leasing business model, the producer primarily sells the functions performed by the chemical, with functional units forming the main basis for payment. Within such models, the responsibility of the producer – now a service provider – is extended, and may include management of the entire life cycle. Chemical leasing aims at promoting the efficient use of chemicals while 10 reducing the risks that they pose to the environment and human health. To this end, it improves the economic and environmental performance of participating companies, and also enhances their access to new markets. Key elements that have been identified from successful chemical leasing business models include proper benefit sharing, high quality standards, and mutual trust between participating companies. Source: UNIDO, “Chemical Leasing” (n.d.) https://www.unido.org/our-focus-safeguardingenvironment-resource-efficient-and-low-carbon-industrial-production/chemical-leasing. Pause to reflect Participatory activity: Identify and elaborate some of the advantages and disadvantages of each of the policy categories and individual policy instruments. Read: Schlegelmilch, K., Eichel, H. and Pegels, A., “Pricing Environmental Resources and Pollutants and the Competitiveness of National Industries” in PAGE, Green Industrial Policy: Concept, Policies, Country Experiences (2017) UNEP and DIE, pp. 103-116. In the context of Denmark’s Pesticide Tax, how would you respond to and address the concerns expressed by industry stakeholders? What recommendations would you have for the Danish policymakers that developed this tax? 6 A mixture of instruments The optimal choice of policy instruments will largely depend on local and national conditions [7]. Today, it is becoming increasingly common for governments to apply a mixture of policies and approaches (through, for example, public-private platforms) to address increasingly complex and interrelated policy challenges. This trend is in line with the recognition that no single instrument alone can effectively promote the greening of industries, and is supported by innovation policy literature which emphasises that a policy mix is particularly relevant for sustainable industrial transitions “that require joined-up interventions from different policy domains” [7]. An increasing number of countries, including Peru, Mexico, Denmark, Germany, and Portugal, are now adopting this practice [8]. The table below provides an example from Denmark in the context of a circular economy. 11 Table 1. Example of policy instruments and tools currently being employed in Denmark to promote circularity Policy intervention types Education, information & awareness Examples of existing policy interventions • Consumer information campaigns • Green industrial symbiosis programme • Four new partnerships (food, textile, construction, and packaging) as part of the Danish waste prevention strategy • ‘Genbyg Skive’ pilot project to re-use building materials in order to create business opportunities and reduce waste • Fund for Green Business Development to support innovation and new business models • Government strategy on intelligent public procurement contains initiatives to support circular procurement practices • Strategy on waste prevention also contains an initiative to develop guidelines for circular public procurement Collaboration platforms Business support schemes Public procurement & infrastructure • Ambitious energy efficiency and GHG emission targets • Ambitious targets for recycling/incineration/landfill to promote recycling and waste prevention (updated every six years) • Taskforce for increased resource efficiency to review existing regulations affecting circular economy practices • Taxes on extraction and import of raw materials, vehicle registration and water supply • High and incrementally increased taxes on incineration/landfill to promote recycling and waste prevention • Highest energy taxes in Europe and CO2 taxes • Tax cuts designed to promote use of low carbon energy Regulatory frameworks Fiscal/economic frameworks Source: Based on Ellen MacArthur Foundation, Delivering the Circular Economy: A Toolkit for Policymakers (2015) p. 46. 12 It is important that governments have the optimal mix of policy instruments in place, and that these are supported by national strategies and integrated policy framework(s). Indeed, “finding the right policy mix for a given challenge is strongly conditioned by the governance context in which individual policies emerge and evolve over time” [7]. While a particular type of policy instrument – or mix of instruments – may appear appropriate on paper, this does not always necessarily translate into public acceptance or enforceability. For example, a particular instrument may produce results that are most consistent with the objectives of green industry, but at the same time face public resistance or pushback from businesses if the policy is perceived to be costly to implement. In some cases, undue influence may also be brought to bear by a limited number of parties. A number of policy options should therefore be drawn in order to address possible uncertainty. In most cases, policy mixes will need to respond to different challenges simultaneously. A green industrial policy may need to both reward and penalise industries, while at the same time supporting businesses through collective incentives. Doing so may require adopting a combination of “soft” and “hard” policy measures. For example, the introduction of an environmental tax to stimulate resource efficiency can only be effective if producers also have access to the financial, technological, and knowledge resources necessary to change business behaviour in response. Guiding considerations for selecting effective policy instrument mixes: Flexibility: Instrument mixes should be constructed in an economically efficient manner, which provides flexibility and does not stifle innovation. This can be achieved by setting long-term targets that facilitate long-term investment decisions by both businesses and consumers (e.g. more efficient processing technologies). Combining instruments: Combining information-based instruments (e.g. labels) with measures that directly target the environmental externality (e.g. tax/regulation) can enhance the effectiveness of both instruments. Avoid instrument overlap: While policy combinations can be beneficial or mutually reinforcing (e.g. taxes and labelling schemes), overlap between some types of instruments (e.g. taxes and product standards) can impede the proper working of the instruments involved, or generate redundancies and unnecessary administration costs. One such example relates to the overlapping objectives between extended producer responsibility obligations on the packaging industry for packaging waste, and the statutory recycling targets set for local authorities. Remove harmful subsidies: The effectiveness of a given instrument mix will be tempered if subsidies are being given to ‘neighbouring’ sectors of the economy, and particularly where these sectors are major contributors to the environmental problem in question. For instance, the granting of agricultural subsidies can limit the effectiveness of policies designed to control the extraction and quality of water. Broad application: Instrument mixes should be applied as broadly as possible, covering all relevant sectors of the economy as well as all countries. For “multi-aspect” environmental issues, policymakers should combine instruments that limit the total amounts of pollution to be released 13 or emitted (e.g. performance standard) with instruments that address the way in which a certain product can be used (e.g. technology standard). Avoid transferring problems: It is important that policy mixes avoid transferring environmental problems between different media (e.g. limiting the leakage of pollutants from waste landfills into groundwater can result in an increase in air pollution from waste incinerators and compost plants). Policy design: Policy mixes should be formulated in a way that encourages preventive rather than end-of-pipe solutions. Source: UNIDO, Green Industry: Policies for Supporting Green Industry (2011) p. 66. Citing OECD, “OECD Environmental Outlook to 2030” (2008). Finally, consideration of the potential costs and benefits of a policy mix is important. While the costs of financial subsidies can be estimated easily, costs arising within enterprises and public administrations that are subject to different policy instruments can be difficult to accurately quantify [9]. Recommended reading Magro, E. and Wilson, J. R., “Policy-mix Evaluation: Governance Challenges from New Placebased Innovation Policies” (2019) 48(10) Research Policy. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0048733318301550 14 Trencher, G. and van der Heijden, J., “Instrument Interactions and Relationships in Policy Mixes: Achieving Complementarity in Building Energy Efficiency Policies in New York, Sydney and Tokyo (2019) 54 Energy Research & Social Science 34-45. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/331821298_Instrument_interactions_and_relationships _in_policy_mixes_Achieving_complementarity_in_building_energy_efficiency_policies_in_New_ York_Sydney_and_Tokyo OECD, “OECD Environmental Outlook to 2030” (2008). https://www.oecd.org/env/indicatorsmodelling-outlooks/40200582.pdf 7 Addressing market failures As discussed in Modules 1 and 2, one of the key features of green industrial policy is that it is typically designed to correct so-called “market failures”. For each of the five policy domains that were identified in Module 3, the table below outlines the wide range of tools, measures, or instruments that can be used to address market failures within these. The measures and instruments fall within the three broad policy instrument categories that have been explored in this Module (command-and-control, market-based, and voluntary/informational). It should be emphasized that not all of the measures, instruments and indeed policy domains will be relevant for each country, and nor are the lists in the table intended to be exhaustive. Indeed, the choice of domain, and the instrument or measure to be employed, will be based on each country's respective idiosyncratic needs, nature of problems, level of industrialization, and development goals. Table 2. Policy instruments for addressing market failures Policy domain Intervention tools/measure/instrument to address market failures Product Import tariffs, export subsidies, subsidy reforms, tax credits, investment/FDI incentives, green procurement policy, export market information or trade fairs, linkage programmes, FDI country marketing, investment promotion agencies Labour Wage tax credits/subsidies, training grants, training institutes, skills councils Capital Direct credit, interest rate subsidies, loan guarantees, development bank lending, finance targeting infrastructure improvements Land Subsidised rental, EPZs, factory shells, infrastructure, legislative change, incubator programmes Technology Technology transfer support, technology extension programmes Source: PAGE, Practitioner’s Guide to Strategic Green Industrial Policy (2016) p. 80. Finally, once the appropriate policy domain and policy measure or instrument(s) has been identified, policymakers may encounter issues while implementing these. Where possible, such issues should be identified beforehand. A policy selection matrix (PSM) can be employed for this purpose. A PSM identifies the results associated with employing different types of policy instruments under a variety of different policy conditions. The table below (on page 17) presents an example of a PSM in the context of a green industrial policy formulation. 8 Conclusion A range of policy instruments can be adopted as part of a green industrial policy to achieve transformational change. These instruments are continually evolving: countries adapt and refine their use according to past experiences, learn lessons in the process, and manage interactions between different tools and measures. Command-and-control regulation, provided it is strictly enforced, has a strong steering impulse. The steering impulse of voluntary/informational instruments is soft, while market-based instruments lie somewhere in between – depending on the scale of market manipulation, and the responsiveness (i.e. elasticity) of supply and demand curves. The process of green industrialization is a complex undertaking, and calls for a holistic approach to policymaking across economic, social, and environmental sectors. It is therefore fundamental that governments employ instruments from each policy category, as part of a coordinated and strategic 15 policy mix. The specific design of this mix will be determined by the environmental issue to be addressed, and on the specific circumstances of that country, including its stage of industrialization, and local conditions and priorities. 16 Implementation Issue Command-andcontrol instruments Policy management cababilities Regulation is useful if compliance is observable, the number of regulated agents is small, and enforcement can be safeguarded. Less technical capacity required Small number of polluters Can be the most effective instrument when the number of polluters is small Individual negotiation with market players entails risks Rent seeking Market-based instruments Taxes/Charges Deposit Subsidies refund schemes The political aspects of monitoring and enforcement need attention, as corruption complicates the implementation of market-based policies. Subsidies may be subject to lobbying, and information on their appropriate level may be obtained by competitive processes, such as the public tendering of renewable energy feed-in tariffs. “Sunset clauses” should therefore be introduced and communicated from the beginning Smaller numbers of stakeholders/actors are able to coordinate more easily and thus exert pressure on policymakers to achieve favourable design for marketbased instruments Create stakeholder opposition Has good potential to address rent seeking May trigger rentseeking and related wasteful activities. Cap-and-Trade Possible if the number of polluters is sufficient and pollution sources can be monitored. However, it requires a higher technical capacity base. Regulatory measures may therefore be preferable if technical capacity is low There is a risk of price manipulation when the number of market participants is too small May be used as an entry barrier, with the risk that polluters Voluntary/informational instruments Voluntary/informational instruments are natural starting points for information disclosure May be better for smaller number of polluters 17 Carry a low risk of rentseeking. Require “sunset clauses” to address such behaviour Inflation Inflation complicates price-based policies Distribution/ Poverty Can have indirect social and distributive effects when the costs of regulation are passed onto the consumer The regressive effects of taxes can be mitigated by revenue use. Charges may be more politically appealing May provide people living in poverty with income opportunities Social and distributional effects depend on who receives and who pays for the subsidies Competitiveness in small, open economy Global coordination or compensation of taxpayers is needed if global competition is strong Global coordination or compensation of taxpayers is needed if global competition is strong May be suitable in a small, open economy Compatibility with international trade law needs to be considered (please see Module 5 for further information) will lobby for free permits Unaffected by inflation Tradable permits are popular with polluters if allocated freely, but they can lead to price changes for consumers (e.g. energy prices) Cap-and-trade instruments may be integrated into the framework of international treaties (e.g. Kyoto Protocol to the UNFCCC) Unlikely to have negative social or distributive effects Can increase access to environmentally-conscious export markets if standards are adhered to Source: Table is adapted from PAGE, Practitioner’s Guide to Strategic Green Industrial Policy (2016) p. 83. Based on Sterner, T. and Coria, J., Policy Instruments for Environmental and Natural Resource Management (2nd edn., Routledge 2012) pp. 256-257. 18 References [1] UNIDO, “A Shift in the Production Paradigm” (2019) Making It Magazine. An interview with Manuel Albaladejo. Retrieved from: https://www.makingitmagazine.net/?p=10886. [2] UNIDO, Green Industry: Policies for Supporting Green Industry (2011) p. 72. Citing UNEP/Wuppertal Institute Collaborating Centre on Sustainable Consumption and Production (CSCP), Wuppertal Institute for Environment, Climate, Energy GmbH and GTZ, Policy Instruments for Resource Efficiency: Towards Sustainable Consumption and Production (2006). [3] Luken, R. A. and Clarence-Smith, E., “Green Industrialization in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Guide for Policy Makers” (2019) UONGOZI Institute. [4] Finon, D., “Carbon Policy in Developing Countries: Giving Priority to Non-Price Instruments” (2019) 132 Energy Policy 38-43. [5] PAGE, Practitioner’s Guide to Strategic Green Industrial Policy (2016) p. 82. Citing Behrens, A. et al, “The Material Basis of the Global Economy: Implications for Sustainable Resource Use Policies in North and South” (2005). Retrieved from: https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/46a7/1570b2582e270e64fc58d891b61eb653e0a1 .pdf?_ga=2.44289956.1882134927.1590575340-943342942.1590575340. [6] OECD. OECD Environmental Outlook to 2030 (2008). OECD, Paris. [7] Magro, E. and Wilson, J. R., “Policy-mix Evaluation: Governance Challenges from New Place-based Innovation Policies” (2019) 48(10) Research Policy. [8] Ellen MacArthur Foundation, Delivering the Circular Economy: A Toolkit for Policymakers (2015). Retrieved from: https://www.ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/assets/downloads/government/EllenMa cArthurFoundation_Policymakers-Toolkit.pdf. [9] UNEP/Wuppertal Institute Collaborating Centre on Sustainable Consumption and Production (CSCP), Wuppertal Institute for Environment, Climate, Energy GmbH and GTZ, Policy Instruments for Resource Efficiency: Towards Sustainable Consumption and Production (2006). 19