A study of churches as a source of support for families with special children

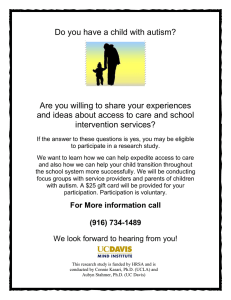

Anuncio