Canon in the History of Economics Critical Essays (Routledge Studies in the History of Economics, 28) (Psalidopoulos) (z-lib.org)

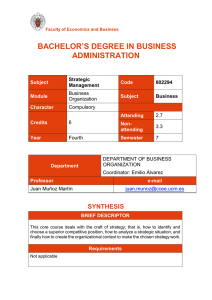

Anuncio