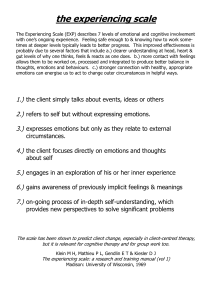

500 Kohlenberg & Tsai ries o f t h e p a s t t r a u m a t i z i n g e v e n t s ( A m e r i c a n P s y c h i a t r i c A s s o c i a t i o n , 1994). So s o m e t i m e s p e o p l e cannot forget t h e i r t r a u m a s . C o u p l e d w i t h w h a t we k n o w a b o u t t h e constructive n a t u r e o f h u m a n m e m o r y - - we d o n o t r e c o r d o u r m e m o r i e s t h e way a c a m e r a takes a p i c t u r e ( B r a n s f o r d & J o h n s o n , 1973) - - t h e r e is r e a s o n to b e wary o f acc o r d i n g validity to all r e p o r t s b y p a t i e n t s o f h a v i n g b e e n s e x u a l l y a b u s e d . Social scientists as well as t h e legal syst e m s h a r e a h e a v y r e s p o n s i b i l i t y in d e c i d i n g w h e t h e r a g i v e n r e c o v e r e d m e m o r y o f a b u s e is a r e f l e c t i o n o f a n act u a l ( a n d c r i m i n a l ) e v e n t . E r r i n g i n e i t h e r d i r e c t i o n creates a n i n j u s t i c e f o r e i t h e r t h e a c c u s e d o r t h e accuser. References American Psychiatric Association. (1994). Diagnosticand statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed.). Washington, DC: Author. Bransford, J. D., & Johnson, M. K. (1973). Considerations of some problems of comprehension. In W. G. Chase (Ed.), Visual information processing. NewYork: Academic Press. Beck, A. T. (1967). Depression:Clinical, experimentaland theoreticalaspects. New York: Harper & Row. Beck, A. T. (1976). Cognitive therapyand the emotionaldisorders.New York: International Universities Press. D'Zurilla, T.J., & Goldfried, M. R. (1971). Problem-solving and behavior modification. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 78, 107-126. Ellis, A. (1962). Reason and emotion in psychotherapy. New York: Lyle Stuart. Fairburn, C. G. (1985). Cognitive-behavioral treatment for bulimia. In D. M. Garner & E E. Garfinkel (Eds.), Handbook ofpsychotherapyfor anorexia nervosa and bulimia. New York: Guilford Press. Kanfer, E H., & Saslow, G. (1969). Behavioral diagnosis. In C. M. Franks (Ed.), Behavior therapy: Appraisal and status. New York: McGraw-Hill. Lazo,J. (1995). True or false: Expert testimony on repressed memory. Loyola of Los Angeles Law Review, 28, 1345-1413. Linehan, M. M. (1993). Cognitivebehavioraltreatmentof borderlinepersonality disorder: The dialectics of effective treatment. New York: Guilford Press. Pirsig, R. M. (1974). Zen and the art of motorcyclemazntenance:An inquiry into values. New York: Morrow. Seligman, M. E. R (1974). Depression and learned helplessness. In R.J. Friedman & M. M. Katz (Eds.), The psvchology of depression: Contemporary theory and research.Washington, DC: Winston-Wiley. Watson, D., & Friend, R. (1969). Measurement of social-evaluative anxiety. Journal of Consulting and ClinicalPsychology,33, 448-457. Weissman, A. N., & Beck, A. T. (1978). Developmentand validation of the Dysfunctional Attitude Scale: A preliminary investigation. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the American Educational Research Association, Toronto. Address correspondence to Gerald C. Davison, Ph.D., Department of Psychology, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA 900891061; e-mail: [email protected] Received: August 25, 1999 Accepted: September30, 1999 Response Paper Radical Behavioral Help for Katrina RobertJ. Kohlenberg, University o f W a s h i n g t o n M a v i s T s a i , I n d e p e n d e n t Practice, Seattle, W a s h i n g t o n Our treatment plan for Katrina is guided by the principles of functional analytic psychotherapy (FAP; Kohlenberg & Tsai, 1991), an approach derived from radical behaviorism. The fundamental assumption is that we and our clients act the way we do because of the contingencies of reinforcement we have experienced in past relationships. It then follows that clinical improvements, which are acts of the client, also involve contingencies of reinforcement that occur in the relationship between the client and therapist. Thus, our treatment of Katrina emphasizes the use of the client-therapist interaction as an in-vivo learning opportunity. It is for this reason that FAP views a caring, genuine, sensitive, and emotional client-therapist relationship as the most important element in the change process. We describe a FAP case conceptualization form designed to help the therapist achieve a curative therapeutic relationship. Our case conceptualization of Katrina includes an account of how Katrina's history resulted in her current daily life problems, identification of Katrina's cognitive phenomena that might be related to her current problems, and most importantly the prediction of how Katrina's clinically relevant behavior dailv life problems, dysfunctional thinking, and improvements~might occur during the session within the therapist-client relationship. UR COMMENTS a b o u t this case a r e f r o m t h e p e r s p e c tive o f p r a c t i c i n g r a d i c a l b e h a v i o r a l c l i n i c i a n s . T h e t h e o r y t h a t g u i d e s o u r c l i n i c a l w o r k is d e c e p t i v e l y simple. It is t h a t we a n d o u r c l i e n t s act t h e way we d o b e c a u s e o f t h e c o n t i n g e n c i e s o f r e i n f o r c e m e n t we e x p e r i e n c e d i n p a s t r e l a t i o n s h i p s . B i o l o g i c a l v a r i a b l e s s u c h as g e n e t i c p r e d i s p o s i t i o n s a r e also i n f l u e n t i a l , b u t s i n c e t h e s e g i v e n s c a n n o t h e c h a n g e d , o u r e m p h a s i s i n t r e a t m e n t is o n c o n tingencies of reinforcement. These contingencies are c u r r e n t a n d a r e always h a p p e n i n g d u r i n g t h e give a n d take o f t r e a t m e n t - - w h e n e v e r we i n t e r a c t w i t h o u r clients. B a s e d o n this t h e o r y , c l i n i c a l i m p r o v e m e n t s , h e a l i n g , o r p s y c h o t h e r a p e u t i c c h a n g e , all o f w h i c h a r e acts o f t h e clie n t , also i n v o l v e contingencies o f r e i n f o r c e m e n t t h a t o c c u r in t h e r e l a t i o n s h i p b e t w e e n t h e c l i e n t a n d t h e r a p i s t . T h e t r e a t m e n t b a s e d o n t h e s e p r i n c i p l e s is c a l l e d f u n c t i o n a l a n a l y t i c p s y c h o t h e r a p y (FAP; K o h l e n b e r g & Tsai, 1991), a n d s t e m s f r o m t h e f u n c t i o n a l analysis d e s c r i b e d b y B. E S k i n n e r . I n c o n t r a s t to p o p u l a r m i s c o n c e p t i o n s a b o u t O Cognitive and Behavioral Practice 7, 500-505, 2000 1077-7229/00/500-50551.00/0 Copyright © 2000 by Association for A d v a n c e m e n t of Behavior Therapy. All rights of reproduction in any form reserved. Response: Radical Behavioral Help radical behaviorism, FAP views a caring, genuine, sensitive, and emotional client-therapist relationship as the most important element in the change process. In applying this approach to Katrina, keep in mind that "act" refers to anything a person does. This includes private, beneath-the-skin acts, such as thinking, feeling, seeing, hearing, experiencing, and knowing, as well as public acts. Every aspect o f being h u m a n is included in this definition, as long as it is expressed as a verb. Thus, instead o f Katrina having a childhood "memory" of abuse and "bad feelings" and associated beliefs, she is "remembering" it, "feeling" the feelings (see Chapter 3 of FAP for a m o r e detailed account of how this happens), and thinking (e.g., "this is horrible" or "I am a screwed up freak and not g o o d e n o u g h for Peter"). Because behaviorism is a theory of behavior change, describing the client's problems as acts provides many options about appropriate targets for change. For example, one option is based on the notion that the remembering, thinking, and feeling per se are not the problem; instead, the problem is her struggling against these and not getting on with her life. For this option, therapy would focus on Katrina developing skills n e e d e d for accepting the intrusive remembering: thinking and feeling as opposed to changing or eliminating them. Steve Hayes's radical behavioral treatment, acceptance and c o m m i t m e n t therapy (ACT; Hayes & Wilson, 1994), and Marsha Linehan's dialectical behavioral therapy (DBT; Linehan, 1993) have highly developed methods for accomplishing this; acceptance is also used in FAP. A n o t h e r option is based on the notion that current situations evoke the remembering of early trauma, and that Katrina is actually avoiding some of the detail in remembering. This avoidance prevents exposure and exposurebased extinction. This paradoxical interpretation o f intrusive memories and flashbacks is also consistent with Katrina's report that she can r e m e m b e r the details o f her abuse and "not feel" (for a more detailed explanation of our account of flashbacks, see Kohlenberg & Tsai, 1998). A third option is that Katrina's thinking does influence subsequent behavior, including feeling depressed and suicidal ideation, and using cognitive therapy to change her thinking would be called for. (For a discussion of cognitive therapy in FAP, see Kohlenberg & Tsai, 1991, Chapter 5; and Kohlenberg & Tsai, 1994a). For a discussion on the process for deciding which of these other options are most appropriate for a particular client, see Kohlenberg and Tsai (1994b). 501 scribed feeling better because of two behavioral repertoires: She had gone back to school and she was more engaged with family and friends. We will refer to these two repertoires as "working" and "close interpersonal relating." We assume that Katrina would agree the primary goals of treatment are to reestablish and maintain her going to school and being engaged with family and friends. From this perspective, impulsive self-destructive behaviors (and subsequent hospitalization) are problematic because they interfere with these goals. H e r feelings (depression, low self-esteem) and thinking are also problematic to the extent that they cause the impulsive behavior and interfere with interpersonal relating. Given this perspective, treatment may or may not focus on changing her thinking and feeling (depression, suicidal ideation, and intrusive memories o f abuse). We will say m o r e about this later. A s s e s s m e n t and Consultation Given Katrina's dangerous behaviors, our first task is to consult an expert on BPD and suicide. Marsha Linehan (the expert we consulted) had several suggestions. 1 First, lethality of the self-injurious behaviors needs to be assessed. Based on the case material, Linehan's impression is that Katrina's self-injurious behaviors present a significant risk of lethality. Thus, it is important that the client receives medical treatment for self-inflicted injuries as needed. Second, additional assessment is needed to determine if the client meets criteria for borderline personality disorder. If so, there is empirical support for using DBT (Linehan, 1993). It is important to assure that the therapist does not reinforce self-injurious behavior; instead, the therapist should reinforce alternative, more adaptive behavior. For example, DBT calls for a 24-hour hiatus in treatment after self-injurious behavior leading to hospitalization; a focus in the session on the chains of behavior leading up to the self-injurious behavior, to the exclusion of other, less aversive topics; and the availability of the therapist between sessions for p h o n e contacts to reinforce more adaptive alternatives to self-injurious behavior. Consistent with DBT, FAP focuses on the therapistclient relationship as an opportunity for in-vivo learning. Specifically, the therapist-client relationship is used as an environment for building behaviors that result in decreasing impulsive and self-injurious behavior and increasing intimate interpersonal relating and other skills. Case Conceptualization Katrina's Presenting Problems As behaviorists, we begin by asking what actions (acts) does Katrina take (or fail to take) that are problematic. In Katrina's case, she reported that she was "better than ever" prior to her last hospitalization. Further, she de- FAP case conceptualization serves three purposes. First, it generates an account of how the client's history 1Marsha Linehan did not review this manuscript, so we take responsibility for an), misrepresentations. 502 Kohlenberg & Tsai resulted in the current daily life problems. Historical interpretations are preferred and include an explanation of how the current problems were learned, and how they were adaptive at the time they were acquired. Historical interpretations set the scene for the client to learn new ways of behaving. Second, it identifies possible cognitive p h e n o m e n a that might be related to current problems. In FAP, the role of cognition in treatment and in accounting for daily life problems lies on a continuum. O n one end of the continuum, problems are more or less caused by the thinking and believing that precede them. In this case, cognitive therapy is appropriate. O n the other end of the c o n t i n u u m , cognition does n o t play a causal role, and in fact may even be absent. In the latter case, cognitive therapy may not be effective and may even be countertherapeutic (see Kohlenberg & Tsai, 1991, Chapter 3). Third, and most importantly, FAP case conceptualization identifies and predicts how clinically relevant behavior (CRB)--daily life problems, dysfunctional thinking, and i m p r o v e m e n t s - - m i g h t occur during the session within the therapist-client relationship. W h e n daily life problems are manifested in the therapeutic relationship, they represent special opportunities for significant therapeutic change because of the widely accepted notion that in-vivo learning is superior. Hence, the case conceptualization helps therapists to notice CRB as they occur and to use these opportunities to shape and reinforce improvements in-vivo. Since the case conceptualization consists of hypotheses, it changes as treatment progresses and more information is gathered. Katrina's Case Conceptualization Katrina engages in impulsive, self-destructive behavior that interferes with productive working (going to school) and close interpersonal relating. She lacks skills to prevent the impulsive self-destructive behavior and those required for productive working and close interpersonal relating. Because of the overlap between increasing close interpersonal relating and increasing productive work- (1) (2) (3) (4) (s) (6) Corresponding Daily Life In-Session Daily Life Relevant Corresponding Problems History In-Session Cognitive Concepts Goals Goals Problems (Automatic (CRB2) Thoughts, Core (CRBls) Beliefs, Underlying Assumptions) FiS. 1. Case conceptualization form used during functional analytic psychotherapy. ing, our discussion will focus on the former. (As an aid to formulating a FAP case conceptualization, the form shown in Figure 1 is used.) 1. Daily Life Problems a. Impulsive behavior due to being unaware of early antecedents. Early antecedents include lower intensity negative feeling and environmental events (such as failure at a task, perceived rejection by others, absence of others who provide social support, lack of reciprocated affection from her husband, etc.). b. In lieu of being aware of and attending to problems that are typically expected to occur with those close to her, she puts on a g o o d front. c. If she were aware of her feelings (early antecedents to impulsive behavior), Katrina doesn't know what to do about low levels of negative feeling (lack of problem-solving skills, skills in describing and talking about negative feelings, asking for what she wants, etc.). d. Intrusive memories of childhood abuse. e. Difficulties in close interpersonal relating related to above. f. Depression. 2. Relevant History History refers to childhood and significant lifespan events or more recent experiences that acc o u n t for the thinking, actions, and m e a n i n g that may be implicated in daily life problems. In Katrina's case, her parents punished her expression of negative thoughts or feelings and reinforced her for acting normal and competent. As a means of doing what her parents wanted, it is likely that Katrina learned not to be aware of her negative feelings (wants, unhappiness, anxiety, and fear) until they became extremely intense (according to behaviorists, awareness is a behavior that is learned). Hence, Katrina's impulsive behavior seems to be a "sudden impulse," with Katrina being unaware of any discernable antecedent. Because Katrina did not learn to be aware of and express "normal" negative feelings, she did not learn to problem-solve before things got out of control. 3. Corresponding In-Session Problems It is likely that Katrina will engage in some daily life problematic behavior during the therapy, within therapist-client relationship. These are referred to as clinically relevant behaviors, Type 1 (CRBls). The therapist needs to be aware of CRBs as they occur such that improvements can be shaped and naturally reinforced in vivo. a. Katrina will not be aware of negative feelings about the therapy or the therapist until they reach intense levels and she acts impulsively. Response: Radical Behavioral Help Correspondingly, she will n o t be aware o f the environmental event that evoked the negative feelings. Evocative environmental events occur frequently during treatment, and may include the therapist being momentarily inattentive, disagreeing with Katrina, not being supportive in a way Katrina might prefer, taking a vacation, turning down a sexual advance, and presenting an assignment that she has difficulty doing. b. In lieu of being aware of and attending to problems that occur with the therapist or the therapy, Katrina "puts on a g o o d front." c. If aware o f negative feelings and problems in the therapy, Katrina will not discuss these or ask for help in resolving the problems. She probably will not discuss her negative feelings about evocative events until they become very intense. d. Katrina probably will have memories of early abuse during the session, but will not identify the events (topic being discussed, either warm or angry feelings evoked by therapist-client relationship, etc.) that were the antecedents and stimulus for the remembering. e. Katrina will be limited in being open with the therapist about her feelings and wants, may become fearful and anxious if she "trusts" the therapist too m u c h or may engage in relationship-sabotaging behaviors as a way o f avoiding closeness. f. Katrina will b e c o m e more depressed during sessions after certain types o f interpersonal interactions that involve perceived rejection by the therapist or failure on her part. She also may have within-session depressogenic cognitions (see below). 4. Corresponding Cognitive Concepts (Automatic Thoughts, Core Beliefs, Underlying Assumptions) Katrina's stated beliefs, such as "If I allow myself to feel, the feeling will never stop" and "If I share my pain with others, they will be freaked out," might play a role in her lack of contact with lowerintensity negative feelings. Katrina's statement "I do not feel. I can tell you anything about my abuse, without feeling a thing" is probably a description of her avoidance of fully rem e m b e r i n g or describing early traumatic events and is not a cognitive p h e n o m e n a that plays a causal role in Katrina's problems. Katrina makes depressogenic self-statements such as "I am a total loser," "I'm not g o o d e n o u g h for Peter (and to be a client)," and I cannot be happy if I d o n ' t have "kids, jobs, fun things to do . . . . " She might also make statements such as "if I ask for what I want, I won't get it." Katrina also might have beliefs such as "I must get rid of my intrusive memories of abuse a n d / o r feeling depressed before I can get on with my life" that are targeted in acceptance therapy. 5. Daily Life Goals a. Becoming aware of situations and feelings that are problematic before they b e c o m e so intense that they evoke impulsive self-destructive behavior. b. Being able to "look bad" (e.g., be emotional, express negative feelings, make complaints with family and friends). c. Try to solve problems before they b e c o m e too intense (e.g., call the therapist or invoke other social support before self-injurious behavior occurs). Develop skills such as being able to verify if an interpersonal rejection has occurred and, if so, to find alternative, more adaptive coping behavior (other than extreme impulsive acts), and m o r e effectively ask others for what she wants, even if she may be rejected. d. Reduce the frequency and intensity of intrusive memories, and if they occur, still make progress toward goals (have memories and get on with life). e. Become m o r e o p e n in close relationships about her feelings and wants. Become m o r e tolerant o f interpersonal fear and anxiety. Become m o r e trusting of others. Detect and stop relationshipsabotaging behaviors. f. Reduce the frequency and intensity o f depression, and if it occurs, make progress toward goals (be depressed and get on with life). 6. In-Session Goals (CRB2) a. Become aware of problems with the therapy or therapist early in the sequence. Be m o r e aware o f low-intensity feeling as it is occurring during the session. b. Be able to "look bad" (e.g., be emotional, express negative feelings with the therapist). c. Develop skills during the therapy session, within the context o f the therapist-client relationship, to identify and discuss negative feeling. Be able to directly talk about rejections (by the therapist) when they occur. Ask the therapist directly for what she wants. Compromise in accepting what the therapist can and cannot give. d. Be m o r e open about her feelings and wants within the context o f the client-therapy relationship. Trust the therapist and b e c o m e m o r e tolerant o f interpersonal fear and anxiety existing within the therapist-client relationship. Detect and stop relationship-sabotaging behaviors. e. Learn to detect therapist-client interactions that evoke intrusive memories and to develop better ways to deal with these situations in session. Re- 503 504 Kohlenberg & Tsai duce the frequency and intensity of intrusive memories occurring during the session. If intrusive memories do occur, remain on task while remembering (use in vivo acceptance procedures). Reduce the frequency and intensity of depression occurring during the session and learn how to stay on task even if depressed (use in vivo acceptance procedures). Treatment O u r treatment plan for Katrina occurs simultaneously on two levels. The first level is cognitive therapy based on Beck, Rush, Shaw, and Emery (1979), and consists of procedures such as defining and setting goals; structuring the session with an agenda, eliciting feedback from client, and using homework assignments; presenting the rationale; and using cognitive behavioral strategies and techniques. In FAP, many of the cognitive therapy procedures are modified to enhance the occurrence and detection of CRB. For example, the t h o u g h t record has been modified to include an in vivo column that helps to call attention to the parallels between the problems occurring in daily life and the therapist-client interaction. At the same time we are using cognitive therapy, we are looking for Katrina's daily life problems occurring in the here and now, within the context of the therapistclient relationship. In particular, we look for CRBls and CRB2s. For example, in assigning homework, we look for unspoken negative feelings about the assignment or about her sense of failure in not understanding it. We would be particularly vigilant for indications that Katrina reacts negatively to something the therapist has (or has not) done, but hides her feelings by putting on a g o o d front. The use of prompting and discrimination training would be used to help Katrina detect and report on lowintensity negative feeling (see Kohlenberg & Tsai, 1991, Chapter 4, for a more detailed description). Of equal importance, we would attempt to shape and naturally reinforce improvements (CRB2s). For example, whenever possible, we would reinforce direct requests (saying directly what she wants) by acquiescing. If we are not able to do what she wants, Katrina's request would be taken seriously, and compromises would be proposed. O u r two levels of treatment are also consistent with and guided by DBT (Linehan, 1993). FAP Rationale P r e s e n t e d to Client In conclusion, we will summarize the philosophy and methods used to help Katrina by describing the rationale that we would present to her. The rationale includes a cognitive therapy c o m p o n e n t while at the same time embracing alternative noncognitive explanations. The importance of the therapy relationship and in-vivo learning are also included. To help understand our approach, we translated the radical behavioral concepts that underlie our therapy into everyday language. The FAP A p p r o a c h to Therapy Clients come into therapy with complex life stories of joy and anguish, dreams and hopes, passions and vulnerabilities, unique gifts and abilities. This therapy will be conducted in an atmosphere of caring and respect in which new ways of approaching life are learned. O u r work will be a joint effort; your input is valued and will be used in the treatment plan. What We Will Focus on in Therapy 1. Learning More Empowering Ways of Thinkinff. We will be teaching you the tools of cognitive therapy (CT). These tools are powerful skills to have at one's disposal. In CT, the basis of negative feelings and ineffective ways of acting is considered to be your thoughts and beliefs. That is, the way you think affects how you feel and what you do. In our treatment, however, we also believe that sometimes feelings can lead to thoughts and actions, or that something else altogether can cause both negative thoughts, negative feelings, and ineffective actions. 2. Increasing Activities That Bring You Pleasure and Mastery: You'll be using a chart to m o n i t o r your activities and moods, and we'll figure out what you can do to increase a sense of accomplishment and enj o y m e n t of life. 3. Considering Other Causes of Negative Feelings and Ineffective Actinff. Some clients may benefit from considering other causes of negative feelings and ineffective acting, such as losses still needing to be grieved, anger turned inward, true self unexpressed, not having e n o u g h joy in relationships and work, needing nurturance but not knowing how to get it, being uncertain of who you are, or being fearful of intimacy. The focus of your therapy will d e p e n d on the causes of your problems. Thus, along with cognitive therapy, your treatment might also include exploring your strengths and seeing the best of who you are; grieving your losses, contacting your feelings, especially those that are difficult for you to experience; developing relationship skills; developing mindfulness, acceptance, and an observing self; and gaining a sense of mastery in your life. 4. Focusing on the Here and No~. The most powerful kind of interaction is based on the present, where something you say affects me, or something I say affects you. Therapy is m o r e impactful when you talk about your experience in the present m o m e n t , like feelings of being depressed and anxious, or thoughts of being unsure of yourself, that are hap- Response: A Dialectical Formulation p e n i n g in the session r a t h e r than j u s t r e p o r t i n g feelings f r o m the past week. W h e n we l o o k at something that is h a p p e n i n g right now, we can experience a n d u n d e r s t a n d it m o r e fully, a n d t h e r a p e u t i c change is s t r o n g e r a n d m o r e i m m e d i a t e . . Focusing on the Therapeutic Relationship as a Way to Learn New Pattern~ T h e therapy relationship prorides o p p o r t u n i t i e s to learn how to express yourself fully a n d create b e t t e r relationships. It will be helpful to focus o n o u r interaction if you have issues or difficulties that c o m e u p with m e that also c o m e u p with o t h e r p e o p l e in your life. W h e n you express y o u r thoughts, feelings, a n d desires in an authentic, caring, a n d assertive way, you are m o r e likely to work productively a n d have closer interpersonal relationships. Closing Comments Above all, o u r t r e a t m e n t o f Katrina emphasizes the use o f the client-therapist interaction as an in-vivo learn- ing opportunity. Even t h o u g h this type o f work has b e e n called for by some cognitive b e h a v i o r therapists (see Goldfried, 1982), we feel its i m p o r t a n c e has b e e n overlooked. A n i n d i c a t i o n o f the potential for in vivo work is illustrated by Marsha L i n e h a n ' s suggestion that the FAP type o f use o f the t h e r a p e u t i c relationship as used in h e r t r e a t m e n t m i g h t prove to be the most i m p o r t a n t e l e m e n t in DBT efficacy (M. L i n e h a n , p e r s o n a l c o m m u n i c a t i o n , March 24, 1999). References Beck, A. T., Rush, A., Shaw, B., & Emery, G. (1979). Cognitivetherapy of depression. New York: Guilford Press. Goldfried, M. R.(1982). Resistance and clinical behavior therap~ In E L. Wachtel (Ed.), Resistance: Psychodynamic and behavioral approaches (pp. 95-113). NewYork: Plenum. Hayes, S. C., & Wilson, K. G. (1994). Acceptance and commitment therapy: Altering the verbal support for experiential avoidance. The BehaviorAnalyst, 17, 289- 303. Kohlenberg, R.J., & Tsai, M. (1998). Healing interpersonal trauma with the intimacy of the therapeutic relationship. In E R. Abueg, V. Follette, &J. Ruzek, (Eds.), Trauma in context:A cognitivebehavioral approach. New York: Guilford Press. Kohlenberg, R. J, & Tsai, M. (1991). Functional analyticpsychotherapy: Creatingintense curative therapeuticrelationships. New York: Plenum. Kohlenberg, R.J., & Tsai, M. (1994a). Improving cognitive therapy for depression with functional analytic psychotherapy: Theory and case study. The BehaviorAnatyst, 17, 305-320. Kohlenberg, R.J., & Tsai, M. (1994b). Functional analytic psychotherapy: A radical behavioral approach to treatment and integration. Journal ofPsychotherapyIntegration, 4, 175-201. Linehan, M. (1993). Cognitivebehavioraltreatmentof borderlinepersonality disorder: The dialecticsof effectivetreatment.NewYork: Guilford Press. 505 Response Paper A Dialectical Behavioral Formulation: The Case of Katrina S h e l l e y M c M a i n , Centre f o r A d d i c t i o n a n d M e n t a l H e a l t h a n d University o f Toronto Katrina is a 25-year-old woman who presents with multiple problems, among them chronic suicidal behavior. Clients like Katrina, who impress diagnostically with a Borderline Personality Disord~ are particularly suited to Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT). It is an appropriate approach because it was developed in the context of working with such individuals, and is one of the few treatments for this population for which there is outcome data to support its efficacy. A DBT approach helps the therapist identify the range of a client's problems and organize problems in order of priority. Treatment interventions, which are premised on a biosocial theory of the etiology and maintenance of a client's difficulties, are guided by a stage theory of treatment. The behavioral patterns that characterize borderline individuals and that often become obstacles to progress are an important focus of treatment. A n overview of a D B T approach and the application of D B T formulation to the case of Katrina is presented. Y GENERAL APPROACH to p s y c h o t h e r a p y has b e e n largely i n f l u e n c e d by my training in e x p e r i e n t i a l t h e r a p y ( G r e e n b e r g & Paivio, 1997; G r e e n b e r g , Rice, & Elliott, 1993) a n d dialectical behavior therapy (DBT; L i n e h a n , 1993a, 1993b). A basic assumption that guides my u n d e r s t a n d i n g is that e m o t i o n dysregulafion figures centrally in the etiology a n d m a i n t e n a n c e o f psychopathology. T h e n a t u r e a n d e x t e n t o f a client's p r o b l e m s determines my decision a b o u t the relevance a n d a p p r o p r i ateness o f a specific therapy m o d e l in each case. T h e case o f Katrina, a w o m a n who presents with multiple problems, a m o n g t h e m c h r o n i c suicidal behavior, impresses diagnostically as B o r d e r l i n e Personality D i s o r d e r (BPD), c o n c u r r e n t with o t h e r D S M disorders. DBT is an a p p r o priate a p p r o a c h to this case for two reasons: (1) DBT was d e v e l o p e d within the c o n t e x t o f treating clients with BPD; therefore, the p r o t o c o l is readily a p p l i e d to this case, a n d (2) t h e r e is a growing b o d y o f o u t c o m e data to s u p p o r t the efficacy o f this t r e a t m e n t with these clients (Linehan, Armstrong, Suarez, Allmon, & H e a r d , 1991; L i n e h a n , H e a r d , & Armstrong, 1993; L i n e h a n , Tutek, H e a r d , & Armstrong, 1994). Address correspondence to Robert J. Kohlenberg, Department of Psychology351635, University of Washington, Seattle, WA98195-1635. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice 7, 5 0 5 - 5 0 9 , 2 0 0 0 Received: August 25, 1999 Accepted: September30, 1999 1077-7229/00/505-50951.00/0 Copyright © 2000 by Association for Advancement of Behavior Therapy. All rights of reproduction in any form reserved.