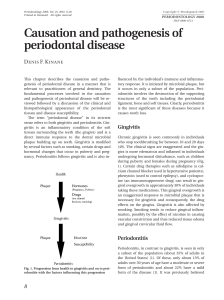

ral giant cell granulorna ntic treatment olfson, DDS,* H. Tat, DMD, PhD,* and S. Covo, Tel Aviv, Israel dwing DMD, Dip. Drtho.** inflammatory and hyperplastic gingival responses during orthodontic treatment are common. These may complicate the actual treatment and may require periodontal therapy. The present report describes the development of an interproximal enlarged peripheral giant cell granuioma during orthodontic treatment, resulting in migration and separation of the neighboring teeth and resorption of the interproximal alveolar septum and molar root. The lesion was excised and the bone was curetted; this led to spontaneous migration of the involved teeth to their natural positions. (AM .J ORTHOD DENTOFAC ORTHOP 1989;96:519-23.) eripheral giant ceil granuloma is considered a benign hyperplastic reaction of the gingival or periodontal tissues to trauma or irritation.’ Traumatic factors contributing to development of the lesion include periodontal pockets, extractions, periodontal surgery, denture irritation, and malposed teeth.2.3 Development may take months, and the lesion can reach a diameter of 2 cm. The pressure of the growing mass of tissue occasionally causes migration and spacing of the teeth.” Histologically, the mass is typically covered with a stratified squamous epithelium and with a fibrillar connective tissue stroma containing ovoid or spindleshaped cells beneath. Interspersed within the connective tissue are multinucleated giant cells resembling osteoclasts i with numerous capillaries often present at the periphery of the lesion. In addition, inflammatory infiltrate containing polymorphonuclear cells, lymphocytes, and plasma cells is commonly seen in the tissue.5 In most cases the lesion is confined to the gingivae and there is DOdestruction of the underlying bone. ’ However, the giant cells can be stimulated by the inflammatory response and act as osteoclasts, resulting in alveolar bone resorption. 5z Surgical excision including the entire base of the growth is the recommended treatment. Persistence after surgery is common and, because of this, the lesion was once inconectly referred to as a tumor.7 The present article reports an uncommon phenomenon in which orthodontic treatment may have played a role in the initiation of a peripheral giant cell granuloma. The clinical and histopathologic features and From The Maurice and Gabriela Tel A;viv University. “Department of Periodontology. -“Department of Orthodontics. 8/4110416 Goldschleger School of Dental Medicine. considerations and the management of the case are described. CASE REPORT An 1 1%year-old boy was accepted in May 1983 for orthodontic treatment at the Tel Aviv University School of Dental Medicine. The patient’s general health was good, with no significant medical history. Developmental and skeletal stages of his teeth were in accordance with his chronologic age (early permanent de&ion). Intraoral examination revealed relatively fair oral hygiene, two small amalgam restorations, no caries, and some localized marginal gingivitis. Molar relationships were classified as slightly Class III on both sides, Class III in the left canines, and Class I in the right canines. There was an anterior crossbite refationship between the maxillary central incisors and the left lateral incisor with the six anterior mandibular teeth (Fig. 1, A). The lower left first premolar was in a crossbite relationship with the two maxillary left premolars. There was a 1 mm negative overjet, a 30% overbite, and a maxillary midline deviation of 3 mm to the right. From initial contact lo maximal dental contact, some forward shift of the mandible was registered. Small facets of attrition were present on the buccal cusps of the lower first permanent molars and second premolars and on the lingual cusps of the corresponding teeth in the maxilla. The maxillary arch was round, with 6 mm of crowding; the mandibular arch was ovoid, with 1.5 mm lack of space for the left canine and two premolars. Radiographic examination did not reveal any pathologic findings (Fig. 1, B). The trabecular structure of the aiveolar bone and the width of the periodontal ligament were within normal limits, and no caries was visible. The buds of the third molars were missing. Cephalometric analysis did not reveal any marked signs of skeletal Class III discrepancy (SNA, 81.5 degrees; SNB, 8 1.5 degrees). The mandibular incisors were labially proclined and the maxillary incisors were slightly lingually in- 520 Wolfsorz,Tal, and Cove Fig. 1. A, Diagnostic casts showing anterior crossbite tooth relationship and crossbite relationship of lower first premolar. Bitewing radiograph showing normal morphology of perioiontium and alveolar bone crest at second premolar-first molar area of left mandible. clined (i to NB, 27 degrees; 1 to NA, 2.5 degrees). The lower third of the face was slightly reduced in height. The case was classified as a dental Class III with crowding. owever, the possibility existed that at a later stage it could express itself as a more skeletal Class III malocclusion. The treatment plan was based on a slight expansion of the maxillary and mandibular arches, advancement of the maxiIIary incisors, and retroclination of the mandibular incisors. In June 1983, bands with double tubes were cemented onto the maxillary and mandibular first molars. The bands were properly fitted with no overhanging or impinging margins into the gingival sulcus. Edgewise brackets, 0.022 x 0.028 inch, were bonded on the remaining teeth. At a later date a stopped 0.018 inch round wire was attached to the mandibular arch and a stopped 0.018 X 0.025 inch rectangular wire was attached to the maxillary arch. Medium elastics, % inch, were applied 24 hours a day from the distal aspect of the maxillary molars to a soldered hook placed between the mandibular canines and incisors. After 1 year of orthodontic treatment, crowding was eliminated, the anterior and lateral crossbites were corrected, and good interdental relations were established. At this time a Fig. 2. A, A 2.5 cm lesion between the lower left first molar and second premolar. The lesion was a bluish red, soft, sessile growth. B, Periapical radiograph of aifected zone shows 2 mm space between first molar and second premolar, Periodontal ligament space is widened on the mesial aspects of the molar roots, indicating distal movement. small gingival proliferation was observed in the interdental space between the left first mandibular molar and second premolar. The lesion was asymptomatic, but bieeding occurred on probing. The area was examined for possibie local irritation or trauma (i.e., food impingement, occlusal trauma, or excessive orthodontic force). but the findings were negative. A thorough scaling of the area was carried out to eliminate any subgingival irritation, but the soft tissue enlargement persisted. The patient was referred to the department of periodontology for further treatment of the lesion. The lesion between the lower left first molar and second premolar appeared as a red soft mass with a rough pebbly surface that nearly reached the height of the marginal ridge. The mass was confined to the interproximal zone and did not extend to the !ingual or buccal surfaces. The lesion was ulcerated on the surface and bled profusely on probing. Radiographic examination showed slight resorption of the crestal bone between the two teeth. The lesion was clinically diagnosed as a localized gingival hyperplasia or possibly a pyogenic granuloma. The gingival Voiume 96 Number 6 Fig. 3. A, Photomicrograph of periphery of lesion. Many multinucleated giant cells in a granulomatous and densely cellular stroma are observed under a thin connective tissue layer. B, Higher magnification of lesion shown in A, presenting multinucleated cells in a densely ceilular connective tissue stroma. tissue was removed with dental curets, and at the same time the roots were scaled and planed to eliminate future sources of gingival irritation. No histologic examination was carried out. Healing was uneventful. Orthodontic treatment was continued after removal of the band from the left first molar 2 weeks later. Three months later the patient returned to the clinic complaining that the gingivae were swollen. Examination revealed that the lesion had recurred but this time in an enlarged form. It now appeared as a bluish red sessile growth, 2.5 cm wide, extending into the alveolar mucosa on both the lingual and buccal sides; its surface was rough and ulcerated (Fig. 2, A). There was a space of 2 to 3 mm between the premolar and the first molar. Radiographic examination showed resorption of the interproximal alveolar bone (Fig. 2, B). On the basis of clinical appearance, rate of growth, effect on the neighboring teeth, and superficial bone resorption, a provisional diagnosis of peripheral giant cell granuloma was made. There were no systemic or local symptoms or signs that could support the diagnosis of a more destructive condition. Since the orthodontic goals had been achieved at this stage, orthodontic treatment was terminated, the bands were removed, and an upper Hawley appliance was inserted for retention. To avoid irritation of the lesion, no retainer was placed in the lower arch. A surgical procedure was performed in the area to remove the lesion and all remaining interproximal tissue above the alveolar bone. Histologic examination of the biopsy specimen showed features consistent with peripheral giant cell granuloma (Fig. 3, A and B). Healing was uneventful, but the diastema between the two teeth remained unchanged (Fig. 4). Fig. 4. Diagnostic casts Healing was uneventful, 1 month after surgical removal of lesion. but the diastema remained tinchanged. Ten weeks after the surgical procedure the patient was seen again at the clinic with a lesion that appeared very similar to the one that was removed. It was about 2.5 cm wide and had expanded symmetrically both lingually and buccaliy. Radiographic examination showed further bone resorption and minimal resorption of the molar root (Fig. 5). It was decided that the surgical procedure should be repeated, but this time the bone associated with the soft tissue lesion was vigorously filed and curetted. Postoperative healing was uneventful. Histologic examination revealed features similar to those of the original lesion. 22 Wdjson, Tul, and Cove Fig. 5. Periapical radiograph showing moderate bone resorption between first molar and second gutta-percha point is located at the mesial groove root of the molar. interproximal premolars. A of the mesial Follow-up examinations during the subsequent months revealed that the space between the two teeth closed 3 months after surgery and the alveolar bone stabilized without any appreciable regeneration (Fig. 6, A to C). The development of the lesion in the present case and its relationship to the orthodontic treatment are difficult to explain. Throughout the treatment period the area was subjected to only the trauma and irritation exerted by the orthodontic movement. To associate this with the development of the lesion would be debatable. However, since to the best of our knowledge the area was not exposed to any other external or environmental influences, such an association cannot be ruled out. The nature of the lesion is not similar to that of the inflammatory hyperplastic gingival lesions often noted during orthodontic treatment. Barack, Staffileno, and Sadowsky” described an inflammatory proliferative and destructive lesion caused by subgingival plaque during orthodontic treatment. The latter is consistent with the features of a pyogenic granuloma, whereas a peripheral giant cell granuloma is essentially granulomatous in nature with the additional characteristic presence of osteoclast-like giant cells. Peripheral giant ceil granuioma may vary considerably in clinical appearance. It always appears on the gingiva or the alveolar processes, frequently anterior to molars. The lesion is pedunculated or sessile and seems to be originating deeper in the tissue than many other superficial lesions in this area, such as the fibrous hyperplasia or pyogenic granuloma. Unlike the central giant cell granuloma and the lesions associated with von Reckiinghausen’s disease of the bone, which pre- Fig. 6. A, Clinical view of treated site 3 months after surgical procedure. Healing was uneventful, and the diastema was eliminated. B, Bitewing radiograph showing complete elimination of diastema between first molar and second preformation and reformation of radiographic crestal lamina dura at a reduced height. C, Study models showing interarch relationship at end of treatment. sents similar histologic features, peripheral giant cell granuloma is less destructive and rarely results in more than superficial bone resorption. In view of the different treatment modalities required ential diagnosis is important, nation of malignant conditions. by these lesions, differespecially in the elimi- Case report This case emphasizes that during surgical excision care should be taken to remove the entire base of the lesion. If only the superficial portion is removed, recurrence should be expected. In the past, it was common practice to remove the adjacent tooth at the time of excision to prevent possible recurrence. This is contraindicated. Although spacing between the teeth is a common sequela of peripheral giant cell granuloma, the spontaneous closing of the space immediately after its resolution in the present case is noteworthy. Apparently the pressure caused by the proliferating lesion was sufficient to overcorhe the connecting transseptal fibers and displace the first molar distally. The fact that the int&-proximal diastema closed rapidly after resolution of the lesion supports the observation that, after periodontal surgery, migrated teeth may tend to spontaneously reposition themselves.’ This may be due to the elimination of edema and granulation tissue and regeneration of the gingival and transseptal collagen fibers. 1. Shafer WG, Hine MK, Levy BM. A textbook of oral pathology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: WE Saunders, 1974:132-4. 5 2. Bhaskar SN; Cutright DE, Beasley JD, Perez B. Giant cell reparative granuloma (peripheral): report of 50 cases. 3 Oral Surg 1971;29:110-15. 3. Gottsegen R. geripheral giant cell reparative granuloma following periodontal surgery. J Periodontol 1962;33:190-4. 4. Shklar G, Cataldo E. The gingival giant ceil granuloma: histochemical observations. Periodontics 1967;5:303-7. review 5 Giansanti JS, Waidron C. Peripheral giant cell granuloma: of 720 cases. J Oral Surg 1969;27:787-91. 6 Anneroth G, Sigurdson A. Hyperplastic lesions of the gingiva and alveolar mucosa. Acta Odontol Stand 1983;41:75-86. Phillips RL, Shafer WG. An evaluation of peripheral giant cell tumor. J Periodontol 1955;26:216-20. Barack D, Staftileno H, Sadowsky C. Periodontal complication during orthodontic therapy. AM J ORTHGD 1985;88:461-5. Manor A, Kaffe I, Littner MM. Spontaneous repositioning of migrated teeth following periodontal surgery. J Clin Periodontol 1984;11:540-5. Reprint requests to: Prof. Haim Tal, Chairman Department of Periodontology The Maurice and Gabriela Goldschleger School of Dental Medicine Tel Aviv University Tel Aviv, Israel