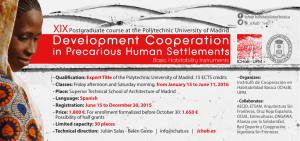

A New View of Goya's Tauromaquia Author(s): Nigel Glendinning Source: Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes, Vol. 24, No. 1/2 (Jan. - Jun., 1961), pp. 120-127 Published by: The Warburg Institute Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/750777 Accessed: 06-09-2018 14:38 UTC JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms The Warburg Institute is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes This content downloaded from 201.82.148.205 on Thu, 06 Sep 2018 14:38:24 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms 120 NOTES significance has undergone a change in pattern is its followed her the course of his preparation of the etching. faces of the other figu of the The Lefort and Douce "Dark parts commentaries which Lady" are close to the poems do not the contribute muche But in our understanding of the final stage in still to further fro pleasant. Goya's treatment of the theme. But their these hints of gene relevance is explained if the Dicimas are wickedness are deve the source for his preliminary drawing. Ultidescending darkness fi mately perhaps the Carderera manuscript the plate which had on in gives the best interpretation of the plate preliminary the when it suggests thatmons all men are equally made yet itself more perverted by passion; that misery and misare recognizably repe viously The fortune figure are human conditions from which the of a owl, nobody which can escape. In fact Goya sym has ex- reason so the horned head accentuates the vileness or often in the panded the original story to make his criti- C cisms general rather than particular, by showing the punisher to be no better than ignorance of his nature. By contrast, the soldier is still less despicable than formerly. the punished. Nevertheless, the lesser-known commentaries were also right in their way Heavy shading on his neck has made his chin when they pointed to one of the "casos deterstronger and firmer. His features as a whole minados" which Sanchez Cant6n suggests seem less coarse. Altogether he is a much underlie many of the Caprichos.21 They serve more pathetic figure than he was in the draw- to remind us that Goya was as much an ing, and his penitential robe now covers him as a learned and literary-minded completely. The head and shoulders ofobserver an of society; that he was equally inapparently genuine penitent echo him in critic the background instead of the allegorical dog.fluenced by what he saw or heard and by what he read.22 Clearly Goya's conception of the story and NIGEL GLENDINNING 19 This aquatint is in the Prints and Drawings De- partment of the British Museum and has the reference 21 F. J. SAnchez Cant6n, Los dibujos de Goya, Madrid and it is probably earlier than either the drawing or the 22 The illustrations to this Note are reproduced by I860-4-I4-27. Delteil (Plate 37) dates it about 1795 1954, I, Introducci6n p. C (v). etching of 'Trigala, perro'. The dress of the three courtesy of the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, the animals is so ambiguous that it is impossible to say Museo del Prado, Madrid, and the Trustees of the whether the aquatint is in any way connected with the British Museum. I am grateful to the Curators of the story of the Monk and the Soldier, or is merely a Bodleian Library, Oxford, for permission to quote caricature of a purge. material from the copy of the Caprichos in their Douce 20 Cf. George Levitine, "Some emblematic sourcescollection as well as extracts from Douce's corresof Goya", Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes, pondence and papers. XXII, 1959, pp. 19 ff. A NEW VIEW OF GOYA'S TA UROMAQUIA The Tauromaquia most recent interpretations of Goya's (P1. 2o) make it one of the least coherent and unified of his series of etch- ings.' In view of the single central topic this may seem paradoxical. But critics have so far always inclined to the opinion that the artist's conception varied in the course of the work. And although it was originally agreed that Goya's prime intention was to describe the Spanish national sport accurately and realistically-in the manner of the later nineteenthcentury costumbristas in Spain-it was early noticed that there were elements in some of x See, for example, E. Lafuente Ferrari's two detailed studies: "Ilustraci6n y elaboraci6n en la 'Tauro- the plates which did not fit in with the sup- maquia' de Goya", in Archivo Espai~ol de Arte, No. 75, posed documentary approach. Th6ophile 1946, pp. 177-21 6, and "Los toros en las artes pl sticas", Gautier in 1842 was one of the first to point in Los toros, ed. Jos6 Maria de Cossio, Madrid, 1953. II, pp. 737 et seq. In subsequent notes these will be otherwise indicated, to the standard published edition referred to as Archivo and Toros respectively. The Plate numbers throughout this Note refer, unless of the Tauromaquia. This content downloaded from 201.82.148.205 on Thu, 06 Sep 2018 14:38:24 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms ::::::.:.:,:,.::::::i:i: iii~~^lii.i;iiiiii:iii~:~:B:: ::i:::::::::::::::::li:i:i:*:"i: i:i: iiiiii-isi~ii:i.ii~i i'.ii?iiiiiii'i.i':i::j::i: :,::.::.::.::.::.::;::::::::::-::: ::::::;:i:i:i:i:i:i:i::::::::::::::::::: -iiiii:i~iiii:i:iii:iiii :i:i;i-ilii?i'iiiiijiiii-ii-ii;iiii:::ii :i''''""''''''''''::':'iii~i ??:~?:i~~'.i?i::-:::?:-:-:-:-:-:::-::::: ::::-:-:::-:::i'iiiii_::i::i:::::::::-: ::iii;iiiiii:iii:i:iai-iiiiiii:i--ii~' :::::::::::::::::: ~l::~c~':Z'~~ iii;i'':"i'iiiiiiZiiiiiiii:i:ii .,i:i;iiiiii;iiliiiiii'i'i'i'i'i'iiii ,~iiii iiiii 'i:iiii:i-iiiiiii:i-ii-iiiiiiiiiiii 'i:::;:::::::~:::: :: i.i-i r -.l:iii:ii:iiii;iiiiiiiiii.iiiiliiiiii i~-'F1~T'';':-: : :: ii~iiiiiiiiii ii--i8ifiii~i'iiii:::ii: i:i::: :::i:i:iii;-iii:; i:i i-iii-iii:i-iiiiiiiiii:iii r:iii iii:iii:i.iiiiiii:i:ii:i::iiii ::-:-:-:::-:::?:::::::::::::: ::::::::::::::::::::i::i:--:::---:.:-:-: :i'iiiiiiiiiii:i:i:i~iiii:iiiiiiiiiiiiii i-i:-iiiiiiii iii iiiiiiiiiijii;iii;ii:iiiiiiiiiiii:-i':i -- iiii-iii:iii:ii:i::iii-,i-iii:~li;: r:::i:::::: iiiiijijijiiiiiiiiiii'iiili;iiiid :::i:::-::-::: i-ii';i'i-i-i:i:i-ici: :ii:i:i-iii:iiiiii=?iiiiiiii-iiii:l:iiii ::::: ::i:i:':::::::-::::;:-::: :I:::i,, ......:.., iK-:-i- ::- ~_i---*ii --::-::-:::iP:i--:::iiiiiiiii:i:i:::,- --:~ - ~i---::i-iii iiiiiiiiiiii _:::-:::::ii-i:_j:i:::_:::::-:::: iiiiiii:ii:-iiiii:-i-i:is-:-:i::::::r:i-c::ii:-i-:i:-:-:-:i: L:- :-::::::-:::::::is:-i:i:ii:::::::::::: i~.ii-i:~i?-i!,iiiiili:siixiiiiiiiiiii .ii~iil:::isiii-i:~i:i-lii:i; i-i:i:i-i-iid -:':;:::'':':":':::::::'::::: iiiii:iiiiii.8:iliici:;i../i:/ii:j/:I/l iiaiiiriii!ii::-i-ii-iitiaiiiiiii;ii iiiiiiiiiii:iii:i"iciai~:-i:iiii:isZi:ii :i:iii:i:i:i:iii'.i:i:ilii;ii.-i;iii-iiii : :-i-::::::- ;iii:i:iiiiiii:i::i:i-il:i8Jiiiiiiiiii-i ii-i'i-iii'i:i's'iiii:iiiii?ii:ii:i~': i:iii-:i:-i:i-iii:Bii.i~ ?iiii-i iii'iii"iiiii:i-i-i'iiiii::~:s- ::.. ::i----:---: :. i :-:-::-:_-:::::::i:i:::::::i:-i:l:i:_:i:::?:::-:-:::::::-:(:i:::::::::::::::?:?::i:iiii~iil::i:l:iai:i-.i-iii-i:iiii:i-iiiiliicii:i:iii:iEiij:i:ji:j/ij_::i:j ii- -i-i-i-i:i-i-iii-: ::::::::::: C iii ii-i iii ii-i iiii -: :::-:-::?::::i::--::-i-:il:;:i:::i:;:~:: ::?::: i.`iii:i::i:i:":~ri:i:i-":i:i:i iiiiiiiiiiiii'iiiiii-i:i-i-iii:i-i-i:i i-ici iiiiiiiiiiiiiiiuii "i:ii-i-i-i-i- :jiiiiiiii~ii:il?ili'iii'i'i'iiiiiii:'ii i:i:-:-:-:::-i::-: :i:iiiii?ii:iiiiiliiiiiiiii-i:iiiii'iii i-i-i:iii-ici.iil -i- -:-i-i:i-i-i: ?:~9i- -i:i i-i-i-i-i-i-i- . i ...b i- i:i i-i-i-i-i i:i i-i ... i:i iii -ii?i~ii:ii:,iiiiiii:,?:?:;:i:as:ii i-iiiii:i:ii:i iii:i~:i:i: iiii~i..i'.iii~j~ii~?;i-iii:l-::-:i::2ii iiiiiijiiii:i:i:iiiii:iiiiiiiiiiii 'i~t';l;-Bi'i:ii~:l:?-i?";i:iiiiil':lii ':- i(i-i-i'i''i' 'i'iii;iiiiiii i ;i': i i-?i Bi -i :i :i i :i ~ .: -: :;-: : -: -: : : - - .- . :_:- :- : _: -: i:-?: -: - -. : . i:'l.:i- ~:ai - i- i- di- "i -i: -i: _:j-: : :? :j _: - :_-_-: iiiiiiiizi'?i"i?i:ii?-iiiiiiiiiliiiii iii::i-i-ii~ :::::::::::::::::::: ::::i:::::ji:i.ii.iii-:iiiiciiiii: .. i:i:ii:ij_?ii:ii:ii:i:i-::-:-:::?:::::: ?;:-: :':"aii~:-i-i:ic:i:i:i-i:_:;l:r:;i:i i:i:i:::::?-:c-:?.:i:::-:-i:::::::::-::: :?::::::: ::::::-:-:-:-:::::-:-:-:-:::i:: ::::i::i::i:: :::::??::-::::::::::::::-::-;:i:::::::i: -ii;ii:i:ii:iiii-ii i-i .... i:ii-ii: -ii-i-i:-ii-ii i:i:iii-i-i:iiiiiii:iiiii:i:i:i-iii-i:i: iiiiiiiilii:iiiii: bi:i-iii:i:i:iii--i~iiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiii- ....::. i: :::i--i-i-i:ii- :ii i i--i--i -:--:: : -:. -:_ :: ::-:_ ::ili-i:i--i-:ii-i:i:ii-i-ii:iiiiiiiiiii : -:--: - -: . :-- :: ::: :: :: :: : : : :--:---:-- :----- -:-::-:::::: ... --i:i:iiiiiii;iii:iiiii-i-:-i:i-i:i:i:i- ii:i-iii-i-iiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiii-liiiiii :--i i-i---i:i-iiii ii:i:i:i-i:i:iii:iiiis_-. iiiiii;iiiiiiii'i:;iii-i:i-i-i:: irlff~?iii~P .ii~i:: . .. :: -_- :i-i-i-ii-i:ici-i-iii-iiiiiiii:i-i:i-i-i i:i:iii:iiiiiiiiiiiijiiiiii iiiiiiiii~iiiiiiiiiiiii iii .. i-i-i- ii:i i-i:i .. ::.. :i i:i-i~:ii-i~ : ._ : ... ::::::::::::::::: :::::_:::_:::-:- -:---::-:-----::-:-i-?:::i -:_ . . -: -:i:_:i--:_---::_---:--:_:-i~:? aiiiijijiii iii -i -:_ ii :_ : ii -i i .. ii ii-i, -iiiiiiiiiiiiisi:iiii:iiiiii-ijfiiitiiiiiii -:: _:: -:;:::-:-: :i:-:i:i:::::-:::- -:: ::_:-:i:i:-: -i:i-i-iiiijiiijijiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiii:i- li;iiii-~iiili-i-rii:iilii~iis;iiiiiii -iiisiiiiii iiii-iii-ii iiiiiiiii.ii-:j --i:ii:ii-ni ---~: ii-i-i-iii:i~ii:i;-iiili:i---:i-i-i'i-i iiii-????????????~ :i:r-::c:::i:i:i:i::-:-:::::-:i:::i '~-''~:~:~iiiiiiiiiiiiiiii?:'::l:''?:i:- i::i;-i.iiiiii iiii:i:iii:i:ii:i:.iii~;ii'~!ii-iii:ii .::. .:...:.. :::.::.._ -::::::::I::: :: ::: :_ :.:.:..._ -i:i-i:iiiii-iiiiii;.i~i::i:i.:'iiiiiii :iii~iiii~~.ii~i~iiiiiiiiiiijiiiiiiciiiii~iiii Li-:iiii:iiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiii:i ~ iiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiili"i:iii:::::i:'':'l: :~':i::i:i;iiZ-'''':`-::::::::;'::::::: -.---" :::-:-:::::::: :::::::::: i-i'i-fii:i':i''i'i'iii-i:i-i-i-i:ili i -:::~ ii ii ::- -:-::::: -i-iiziiiiiiiii-iiiiii:ii.ii .:. ~i ::_ --_-- i-iii-i:i-ii~?~'l?:.:~:::ii-iiiiiii--iii i: -i-:i -:i ii?iii;iiiiiiiiiiiiii i-i iii i:- i-- iisi:ici:siid;?.-j.~jiij:i:ii-i:j:ji i- -; ::::::---::: :i- i -ii?i-i-iii:ii iiiiiiiii-iiii :::::::::: ::__,__ :_ :: -*~:--ii:-~i:iiiiiijiiji_::_::,::-::,,,, :-:- - ::: ::: .-.- b-Title-page a-Goya, aquatint, 'Le Clystere', British Museum, Department of Prints and Drawings, 1860-4-14-27 (p. I19) c-Lysippus the Younger, medal depicting Catalano Casali (p. 128) d-reverse of (c) (p. I28) This content downloaded from 201.82.148.205 on Thu, 06 Sep 2018 14:38:24 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms M 20 Photo : Conway Library, Courtauld Inst. of Art, London a-Goya, Tauromaquia, No. I, 'Modo con que los antiguos espafioles cazaban los toros a caballo en el campo', Ist ed., 1816 (p. 12o) b-Goya, Tauromaquia, No. Io, 'Carlos V lanceando un toro en la plaza de Valladolid', Ist ed., 1816 (p. I20) : Conway Library, Courtauld Inst. of Art, London This content downloaded from 201.82.148.205 on Thu, 06 Sep 2018Photo 14:38:24 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms A NEW VIEW OF GOYA'S TAUROMAQUIA 121 inconsistencies they find in the series, because this out. "Quoique les attitudes, les poses, they still techadhere to the initial nineteenthles attaques, ou, pour parler le langage nique, les diff6rentes suertes et cogidas century soient view that the Tauromaquia is a serious and documentary work.7 Faced d'une exactitude irreprochable," historical he wrote, "Goya a repandu sur ces scenes des with ombres inaccuracies, they tend to suggest that at best Homer was momentarily nodding, and mysterieuses et ses couleurs fantastiques.'" Other nineteenth-century critics shared Gau-dealing with the more distant at worst (when tier's view. It was implicit in Carderera's past) was awake but simply not interested in what hewhich was doing.8 Yet it is hardly good discussion of the preliminary drawings critical method to treat what seem to be were in his possession, and in Matheron's description of the etchings themselves; lapsesBrunet on the part of the artist in a cavalier manner before it is certain that they do not, quoted and Charles Yriarte paraphrased Gautier with respect and evidentinapproval.3 fact, form an integral part of the work and But the straightforward duality ofcontribute spirit and to its meaning. Goya was perfectly content-the one Romantic and the other capable of accuracy when he wished. The factual-which they thought they saw trouble in the he took over significant detail in Tauromaquia, has long since been set aside as religious paintings has often been certain an over-simplification. Already in 1877 Leattested,9 and there is no reason to suppose fort could trace two separate mannersthat, in the given his interest in bull-fighting, he actual execution of the work,4 and recently could not have acquired the necessary historiLafuente Ferrari has outlined no less than cal information had it been his purpose to three distinct phases or conceptions in it.communicate it. The suggestion that Goya The view of the whole nature of the series has was not genuinely interested in the non- changed radically. And now, instead of thecontemporary side of the work is equally highly coloured but accurate account of theexceptionable. Why should he have embull-ring beloved of the nineteenth century, barked upon it in the first place if he would we have a work full of anachronisms and inhave preferred to give an account only of adequate documentation: afrente por detrdswhat by he had seen himself? The existence of Moors in Plate 6; incongruous archesAntonio in Carnicero's Coleccidn de las principales Plate 8; Charles V improperly dressed in suertes de una corrida de toros (Madrid, 1790) Plate Io; and in Plate 30 a method of holding would hardly have been sufficient to stop him the sword for the kill more appropriate if tothat a was what he really wanted to produce. hand-saw, according to one critic and aficionado.6 In view of the increasing number of anomalies found in the Tauromaquia some new overall interpretation would seem to be necessary if the work is to be seen as a satisfactory artistic whole and not an arbitrary string of brilliant independent pieces united only by medium and general topic. Up to the present most critics have rather condescendingly tried to explain away and not to account for the In re-examining the Tauromaquia, therefore, I intend first to inquire into the exact nature of the historical basis of the work and the artist's treatment of it. Is it as straightforwardly documentary and "realistic" as is usually supposed? And, if it is, are the inaccuracies merely accidental or is there some ulterior motive behind them? Finally, is Goya's carelessness or ignorance or unconcern the only possible explanation of the anomalies in the series, or is there some other explana- tion which would give them function and 2 Le cabinet de l'amateur et de l'antiquaire, Paris, 1842, significance? I, p. 344. 1 Cf. Laurent Matheron, Goya, Paris, 1858; article of Carderera in Gazette des Beaux-Arts, Paris, i86o, VII, pp. 225-6; M. G. Brunet, Etude sur Francisco Goya, Paris, I865, p. i9; Charles Yriarte, Goya, Paris, 1867, p. 120o ("le parti pris de coloration . . . donne A ces planches un aspect fantastique et conventionnel"). ' Paul Lefort, Francisco Goya, Paris, 1877, p. 69- "II y a deux manibres dans la Tauromachie, et les planches num6rot6es de I I12, par exemple, nous paraissent diff6rer de celles num6rot6es I9, 23, 27, 28, 31 et 32, pour ne citer que les plus saillantes, aussi bien par le proc6d6 et la conduite de la pointe que par le mode de composition et par le dessin." * Cf. Archivio, p. I85. d Cf. Toros, comments on Pls. 6, 8, Io and 30. 7 Cf. for example A. de Beruete y Moret, Goya, Madrid, 1928, p. 230; Archivo, p. 177 ("Es la Tauromaquia la dinica serie grabada del artista que parece ostentar un cierto valor documental e ilustrativo, consciente y decidido en su autor"); also p. 18I, but compare comments on Pls. 3 and 9, pp. 188, 191. 8 Cf. Toros, p. 779 for example ("en nada mejora su documentaci6n hist6rica para representar al Cid, que aparece aqui grotesca y anacr6nicamente vestido .. ."). Lafuente seems to suggest that Goya was almost relieved to give up the historical side of the work in P1. 13, see p. 786. 1 Cf. F. Sanchez Cant6n, Vida y obras de Goya, Madrid, 1951, p. 114. This content downloaded from 201.82.148.205 on Thu, 06 Sep 2018 14:38:24 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms 122 At NOTES is usually taken to be "Martincho" throwing sight it wou a bull in the Madrid arena, could in fact be Goya conceived first that Mam6n" who is mentioned of by historical"brave survey tisement which was inserted in the Diario de Moratin plausibly enough as one who caught Madrid on 28 October 1816, and again bulls in by the tail and climbed on to them.'5 the Gaceta de Madrid in December of the same But the mere presence of historical material, year, appears to say so unequivocally.'0 from whatever source it is taken, does not necessarily mean that the work is intended to "Colecci6n de estampas inventadas y grabadas al agua fuerte por Don Francisco Goya,impart historical information in a simple documentary way. Indeed, Goya's failure to pintor de cdmara de S.M.," it runs, "en que se representan diversas suertes de toros, ykeep to a chronological order on several occalances ocurridos con motivo de estas funciones sions and his apparent lack of concern for en nuestras plazas; dindose en la serie de las accuracy of detail, might be taken to imply that it was not his intention to be documenestampas una idea de los principios, progreso y tary. Obviously, before further conclusions estado actual de dichas fiestas en Espafia, que can be reached we should ask whether the sin explicaci6n se manifiesta por la sola vista de ellas . . ." (my italics). Apart from the departures from chronological order and slight possibility of irony in the reference tohistorical accuracy might not in themselves the present state of bull-fighting-Goya porhave formed part of the artist's aim. Some trays practically nothing after the turn of the light is thrown on this difficult problem by a century-everything in the announcementmanuscript list of the plates bound with the points to a didactic and historical approach, copy of the Tauromaquia bought by Francis which was precisely what distinguished itDouce, probably in the I820's, and now in from the earlier and immensely popular series the Ashmolean Museum at Oxford.s6 This of Antonio Carnicero.1" The fact that Goya manuscript, Asuntos de las Estampas, differs based his work on NicolAs FernAndez de from the list originally printed and distriMoratin's Carta histdrica sobre el origen buted y pro-with the work in both the descriptions gresos de las fiestas de toros en Espania (Madrid, and the order of the plates. The order it 1777, with new editions in Madrid, 18oi0, gives is, in fact, more rigidly chronological than that of the usual text, and if it could and Valencia, 1815), adds still further weight to this view.12 Lafuente Ferrari, collating be argued that Goya had this particular seand developing the conclusions of earlier quence in mind when preparing the platescritics, claims that no less than fifteen or of the at least before numbering them-there original set of thirty-three plates can be traced to Moratin's Historical Letter.x3 And in sobre el origen y progresos de la fiestas de toros en Espania, fact two more borrowings can probably be1777 (B8 v and Cx r). Madrid, 15 The manuscript description of this plate in the added to this count. Plate 13, which repre- Ashmolean Museum copy of the Tauromaquia reads sents "A Spanish nobleman on horseback "El esforzado Mamdn vuelca un toro en la de Madrid". breaking lances without the assistance of Cf. Moratin, op. cit. (C8 r). See below for details of chulos", could well portray, to judge from the the Ashmolean copy of the Tauromaquia. It is difficult to say when exactly Douce acquired vaguely seventeenth-century dress of 16 the the copy of the Tauromaquia. In the "Transcript of rider, the Duke of Medina-Sidonia, whom Douce's Dairy of Antiquarian Purchases 1803-34" in Moratin mentions as killing two bulls thewith Bodleian Library (MS. Douce d. 63), there is a two lances at the wedding of Charlescurious II in entry under Ist March 1828 which may conceivably refer to Goya's work. It reads: "Spanish rules I679, or Don Bernardino Canal, who fought of... illd by Aroya", which could be a transcription bulls in the manner depicted in the presence of "Spanish rules of bull-fighting ill[ustrated] by of the King in I725.-4 And Plate 16, Goya"-a which possible description of the work. On the other hand, not all Douce's purchases were entered in the 10 The advertisement in the Diario is quoted byDiary and he may have bought the Tauromaquia earlier. He bought two copies of Goya's Caprichos in SAnchez Cant6n, op. cit. I Ii. The Gaceta announce- I818 ment appeared on 31 December I816 and is in noand 1825, and had long been interested in bull- significant way different from that in the Diario. fighting prints. He acquired a French print entitled Course de Taureaux a Cuenca (Quito) in June, 1804, and 11 Cf. Toros, p. 859 et seq. possessed a tinted set of Antonio Carnicero's Coleccidn 12 Cf. Toros, p. 767. Valerian von Loga, "Juan de de had las principales suertes de una corrida de toros as well as la Encina", Ventura Bargtids and Sinu6s Urbiola all mentioned Moratin in connection with the Taurosome smaller imitations of that series (Bodleian Library, Douce Prints, E. I. 4 (251-263) ). I must maquia before Lafuente. thank Mr. Giles Barber of the Bodleian and Mrs. C. A. 18 Cf. Toros, p. 768 et seq. The plates in question are Nos. I, 2, 3, 5, 6, 7, 9, 10, II, 12, 14, 15, 18, 19, 27. Gunn of the Fine Arts Library in the Ashmolean for invaluable assistance in my Douce researches. 14 Cf. NicolAs Fernandez de Moratin, Carta histdrica This content downloaded from 201.82.148.205 on Thu, 06 Sep 2018 14:38:24 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms t A NEW VIEW OF GOYA'S TAUROMAQUIA 123 que sehis celebraron might be grounds for supposing that de-alli, por el nacimiento de su hijo I. (1o) partures from it had some specialFelipe purpose. Vn caballero By courtesy of the AshmoleanXIII. Museum I en plaza quebrando re- joncillos. (13) quote the manuscript in full here, distinguish- ing the order it gives from the usual XIV. Desjarrete one byde la canalla, con lanzas, medias-lunas, banderillas y otras armas. (12)to the which follow the descriptions refer XV. Elnormal diestrisimo Estudiante de Falces, emPlates to which they correspond in the bozado burlando order. It will be seen that "Palenque que al toro con sus quiebros. (14) hacia la canalla" (No. XI in the manuscript-- Roman numerals. The Arabic numbers XVI.chronoEl insigne Martincho, poniendo banNo. 17 normally) is in its proper logical position-although the use of the term derillas al quiebro.del (I5) mismo Martincho en XVII. Temeridad la canalla in the manuscript instead of los plaza de Madrid. (18) moros seems to fit the preliminary la drawing Otra better than the plate itself;17 thatXVIII. the Cid is locura del propio Martincho en placed logically before Charles V; and that la de garagoza. (19) XIX.and El esforzado Mamon vuelca un toro en the plates portraying "Martincho" "Pepe-Hillo" are grouped appropriately la detoMadrid. (I6) gether. XX. Ligereza y atrevimiento deJuanito Apifiani, alias el de Calahorra, tambien en la de ASUNTOS DE LAS ESTAMPAS18 Madrid. (20) I. El modo con que los antiguos espafiolesXXI. Desgracias acaecidas en el tendido de cazaban los Toros a caballo en el campo. esta plaza, y muerte del Alcalde de Torrejon. (21) (I) XXII. Valor varonil de la celebre Pajuelera II. Otro modo de cazarlos a pie. (2) en la de Zaragoza. (22) III. Los moros establecidos en Espafia, pres- cindiendo de las supersticiones de su Alcoran, adoptaron esta caza y arte. (3) IV. Comienzan los moros a capear los toros en cercado, con el albornoz. (4) V. Otro capeo de toros hecho por los moros en plaza. (6) VI. Los moros torean con harpones, 6 banderi- llas. (7) VII. Vn moro es cogido del toro, lidiando con banderillas. (8) VIII. El valiente moro Gazul lanzed, con galanteriay destreza. (5) IX. El Cid Campeador, el primer caballo (sic) espai~ol que alanced los toros con esfuerzo. (i i) X. Otro caballero espafiol, despues de haber perdido el caballo, mata el toro a pie con summa gallardia. (9) XI. Palenque que hacia la canalla con burros, para defenderse de los toros. (17) XII. Carlos V, mata un toro de una lanzada en la plaza de Valladolid en las fiestas de toros, 17 In the preliminary drawing none of the men fight- ing the bull are obviously Moors (No. 191 in Sanchez Cant6n, Los dibujos de Goya, Madrid, I954, I). 18 In transcribing the manuscript I have kept strictly to the spelling and accentuation of the original, XXIII. Mariano Ceballos, alias el Yndio, mata al toro desde su caballo. (23) XXIV. El mismo Ceballos quiebra rejones montado sobre otro toro en la de Madrid. (24) XXV. Caida de un Picador de su caballo devajo del toro. (26) XXVI. El celebre Fernando del Toro bari- larguero, obligando a la fiera con su garrocha. (27) XXVII. El esforzado Rendon, que murid en esta suerte en la Plaza de Madrid. (28) XXVIII. Perros. (25) XXIX. Vanderillas de fuego. (31) XXX. Dos grupos de picadores arrollados en el suelo de seguida por un solo toro. (32) XXXI. Pedro Romero matando a toro parado. (30) XXXII. Pepe-Hillo, haciendo al toro el recorte. (29) XXXIII. Su desgraciada muerte en la plaza de Madrid. (33) The immediate problems which arise from this manuscript are those of its date, source and connections with the artist. Clearly, if it is not earlier than the final numbering of the series it can have little relevance for the study XXI and XXVIII. Those which are closer to the of the work: Goya could not possibly have borne it in mind when preparing the plates. Of course, the very fact that the numbering Nos. IX, XII, and XIX. an indication of earlier date, although it is and italicized those portions of the comments which differ from the printed text. The following are slightly abbreviated by comparison with that text: Nos. XIII, is different from that finally adopted could be wording of Moratin in the manuscript version are This content downloaded from 201.82.148.205 on Thu, 06 Sep 2018 14:38:24 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms 124 NOTES conceivable such a l seen that as the expression of the view that there drawn up subsequently was cruelty and coarseness in those who w sion. But there is at least one feature of the fought and those who watched, the Tauromanuscript itself which gives us both more maquia could be brought into line with Goya's concrete evidence of its date and a hint about other series of etchings, whose critical views its source. It is evident that a thirty-fourth and pessimism about human nature have long plate figured on the original list and was been cut recognized. Since Lafuente Ferrari has out at some later date; a reference lightly already hinted at the possibility of irony in crossed through on the manuscript title-page one of the plates, and since "Juan de la Encina" and other critics have on occasion reveals that the etching in question was titled "el modo de poder volar los hombres conclaimed that Goya was purposely showing the alas"-one later included with the Proverbios bull-fight in its most barbaric and brutal or Disparates. Now this plate is known to have light, it is surprising that such a view of the work been added by Cedn Bermidez to the set of has not been seriously considered be- fore.22 But the tendency has been for critics the Tauromaquia etchings sent to him by Goya so that he could revise the titles.19 So it seems to explain the element of barbarity in terms quite likely that this manuscript itself came of "realism", for it is difficult at first sight to from CeAn Bermidez and represents reconcile the criticism of the sport with the tradiorder of plates which he suggested. Unfortutional-one might almost say legendarynately, it has not been possible to identifyidea the of Goya as an aficionado, "el de los toros", handwriting. possibly even as a bull-fighter himself in his time.23 Yet if there is evidence that Goya was This theory, of course, in no way explains why Goya did not adopt this order, which anisenthusiastic follower of the spectacle and obviously more satisfactory from the point personalities of of the bull-ring as a young man, there is little to suggest that he seriously held view of logic and chronology. But since Goya usually followed his friend's advice in matters such views in his later life. It may be true of wording and presentation,20 he must have that in the portrait of Pedro Romero, Goya was at pains to capture, as Jose Somoza had some particularly good reason for not doing so in this instance: the desire to achieve suggests, the "uprightness, even the sensia special effect by means of disorder, for tivity" of the bull-fighter, avoiding anything example. It is the main contention of the which might reflect "the heartless ferocity of present article that this disorder is indeed the gladiator's habits".24 But there can be meaningful, and contributes to a satirical, no notdoubt about the critical view of bulls a historical, effect. The possibility that fighting the expressed in the series of lithographentitled Los toros de Burdeos, finished in 1825, whole work is satirical cannot be lightly only ten years after the Tauromaquia.25 thrown aside, as some critics have supposed.21 Considering the circumstances in which the Such an interpretation of the Tauromaquia work was produced, there is much to be said would in fact justify most of the apparent both for and against the satirical theory. The anomalies mentioned at the beginning of this article. It would give new significance to the 2* Lafuente Ferrari commenting on P1. 6 in Toros grotesque appearance of Charles V and the "N6tese que Goya, un tanto graciosa y gratuitaancient Spaniards. Other inaccuracies in writes: the mente, achaca en cierto modo a los moros esta suerte de plates would add to the ironic and critical frente por detrds" (my italics). For Goya's concentraeffect. Furthermore, if the work were to be on barbarity, see "Juan de la Encina", Goya en tion 19 Cf. Paul Lefort, op. cit., p. 88. Zig-zag, Madrid, s.d., especially pp. 166, 167 and 175; Hans Rothe, Francisco Goya Handzeichnungen, Miinchen, 20 Cedn Bermddez is generally supposed1943, to have P. 12; and Angel SAnchez Rivero, Los grabados written the announcement of the Caprichos inserted in Madrid, 1920, p. 49. de Goya, the Diario de Madrid for 6 February 1799; and23critics Cf. for example Charles Yriarte, Goya, sa vie, son usually suppose that he gave advice on the oeuvre, Desastres Paris, 1867, p. 120o ("s'il faut en croire ses amis also, see August L. Mayer, Francisco de Goya, London, Ribera et Velasquez (?), il s'est meme engag6 dans une quadrilla, et a tue lui-meme") and Valentin Carderera's 1924, Pp. 95 and Ioo. 21 See, for example, Angel SAnchez Rivero, Los earlier article "Frangois Goya, sa vie, ses dessins et ses grabados de Goya, Madrid, 1920, p. 48 ("Eneaux-fortes" la Tauro- in Gazette des Beaux-Arts, Paris, 186o, VII, maquia abandona Goya su visi6n de moralista .. ."); p. 225 ("Les courses de taureaux 6taient sa distraction favorite Jos6 Llampayas, Goya, Madrid, 1943 ("En estos gra-. . ."). More scholarly detail in Toros, pp. 737 bados no hay humor ni sdtira . . . sino emoci6n et seq. y verdad."); F. D. Klingender, Goya in the democratic 24Cf. "Recuerdos e impresiones de Don Jos6 tradition; London, 1948, p. 166 ("In this work Goya Somoza", in Biblioteca de Autores Espanioles, LXVII, was not concerned, like the author of Pan yp.Toros, to 458, quoted by Lafuente in Toros, p. 740. condemn bull-fights as inhuman."). 25 Cf. Toros, pp. 844-5. This content downloaded from 201.82.148.205 on Thu, 06 Sep 2018 14:38:24 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms A NEW VIEW OF GOYA'S TAUROMAQUIA 125 I8Io. intellectuals were opposed to fact that the Tauromaquia appeared atMany a time when bull-fighting was particularly bull-fighting popular at the time and several of Goya's friends andof the subjects of his portraits like seems to weigh against the satirical view the series. After the Peninsular War bullJovellanos, Tomas de Iriarte and Melkndez fighting was looked upon as a truly national Valdes, for instance, spoke out against it.29 Even if there is some doubt about the friendpastime, infinitely preferable to anything which smacked of French influence, like ship between Goya and Vargas Ponce, one piano-playing or neo-classical drama. A of the strongest critics of the bull-ring"Colecci6n de 12 estampas y una portada ...Lafuente Ferrari suggests that Goya was que representan las principales suertes de una anxious to skimp his portrait30-it is certain corrida de toros"-probably Carnicero's series or one modelled on it-was advertised that the artist must have heard many attacks on the national sport by those he knew and at least three times between 1815 and respected, 1817, and have read others by men with and therefore must have sold well.26 And whom he had no personal contact. Antonio de Capmany, who had set upStill as more tangible support for the satirical arbiter of taste for Spanish patriots in his is to be found in the Ashmolean copy theory Centinela contra franceses, gave bull-fights of his the Tauromaquia, whose manuscript descrip- official blessing in an Apologia de las fiestas tions of the plates have already been quoted. publicas de toros published in 1815. Although The manuscript title-page is equally interestone or two intellectuals could still write ing and seems to imply quite clearly that the was intended to be critical. The actual against the bulls at this juncture, towork do so openly would certainly have seemed lay-out afran- and handwriting can be seen in the cesado. photograph reproduced with this note (see On the other hand, it may have been P1. the I9b). The text reads as follows: ripeness of the time from another point of Treinta y tres Estampas view-that of the likelihood of sale-which que representan diferentes suertes y actitudes made Goya publish a new series of etchings on bull-fighting precisely when he did. Prints del arte de lidiar los Toros; y una el modo de poder volar los hombres and etchings in general were much in demand con alas. in the years which followed the war. The Ynventadas, disefiadas y grabadas al agua Almacen de Estampas in the Calle Mayor at fuerte por el Pintor original Madrid, which was ultimately to sell the D. Francisco de Goya y Lucientes Tauromaquia, frequently advertised its stock En Madrid. from 1815 onwards.27 And the Real Calcoi Barbara Diversion! grafia resumed its activities in August 1816, Estaofes la voz del Publico racional, religioso offering Goya's and Castillo's engravings eight paintings from the Royal Palace on 6 ilustrado de Espafia. 19 September, and Goya's Caprichos on the 26th of the same month.28 29 Cf. Toros, p. 140 et seq. It is very possible that Goya's mentor CeAn Bermidez-an admirer of Jovel- This kind of circumstantial evidence is,lanos of and Vargas Ponce-was also opposed to bullfighting. And Leandro Fernindez de Moratin was necessity, inconclusive, but if we accept Car- derera's word for the slow elaboration of the another friend of the painter probably against the sport. He makes no mention of his father's Carta Tauromaquia-very approximately between histdrica in the life of Nicolds FernAindez de Moratin I8oo and I815-there is perhaps more in the which he wrote for the edition of the latter's Obras pdstumas, Barcelona, 1821. And there is a passage in period background to support the satirical his Notes on England where he compares the idle young theory. In the first place official policy in the English gentlemen with "carniceros o toreros puestos early years of the century was opposed to en limpio" because of their "aspecto rdstico y amenaza- bull-fighting. After a series of restrictions imdor". This comparison, following as it does a highly critical description of "la juventud mAs decente de posed during the reign of Charles III, the Londres" suggests that Leandro was not as wholecorridas were banned altogether in 18o5 and in favour of bull-fighting as was his father. resumed only under Joseph Bonaparte heartedly in80 Lafuente's statement of the facts seems rather biased (Toros, p. 764). Vargas did not know Goya personally before the painting of his portrait and asked 26Gaceta de Madrid, 1815, p. 604; xI86, p. 470; 1817, p. 408. 27 Cf. Gaceta de Madrid, x8x5, PP. 244, 276, 500, 548, 806, o108, 1030, o1090, 1238, 1358. 28 Cf. Gaceta de Madrid, pp. 899-900 (re-opening of the Calcografia reported) ; p. 1o0o (notice of Goya and Castillo's work); p. 1051 (advertisement of Caprichos). his friend CeAn Bermddez for a letter of introduction on 8th January x805. As a friend of Cedn one would have expected Goya to receive him well. And, in fact, there is nothing to show that Vargas was dissatisfied with the painting, since he was one of the first to praise Goya in print in his Proclama de un solterdn (x8o8). The This content downloaded from 201.82.148.205 on Thu, 06 Sep 2018 14:38:24 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms 126 If NOTES this page, were only difficulty Goya's is that we do not know how farow orGoyaone himself approved ofover the contents of the w agreement manuscriptwith title-page, which is inCetn the same aim of the handwriting etchings as the Asuntos de las Estampas and -unless we were to conclude that he dispresumably from the same source. In the sociated himself by irony in the last lines last from resort, only the plates themselves and the rational, enlightened and religious people in preliminary drawings can tell us the real nature of the work. Spain, which would be difficult to prove from his other works.31 Furthermore, apart Infrom fact in these drawings and etchings for the final words themselves, the original theintenTauromaquia there is no lack of detail of tion to include in the series what was later to an apparently critical nature. The broad, be one of the Disparates would seem an addipicture-like frames which surround all but tional pointer to the pessimistic conception eight of of the series may suggest no more than a human nature underlying the series. There certain detachment on the part of the artist. 33 is no obvious optimism in the flying menBut of the evidence within the various plates is "Modo de volar". Goya often associates flight telling: the gap-toothed faces of the ancient with the forces of evil, and flying in general Spaniards in Plates I and 2 for instance; the remained a folly or a symbol for man's futile ludicrously dressed figure of Charles V in Plate Io, with authentic beard and moustache pride until the Romantics began to see somebut cross-bands and headgear not unreministhing admirable in ascent into the sky.32 The cent of the French soldiers in the Desastres;34 details about the letter of introduction are given by the unconcerned rider who, in Plate 25 and Sinchez Cant6n, Vida y obras de Goya, Madrid, 1951, the preliminary drawing for it, turns his back p. 81. eloquently on the carnage of the dogs;35 31 In particular Goya's idealistic view of Reason can be adequately supported by reference to the Caprichosespecially No. 45-and to the drawing with the caption "Divina Raz6n, no deges ninguno" (SAnchez Cant6n, Los dibujos de Goya, Madrid, 1954, II, No. 380). 32 The interpretation of No. 4 of the Disparates presents some difficulties. Cam6n Aznar in his "Los Disparates" de Goya y sus dibujos preparatorios, Barcelona, 1951, p. 61, suggests that it is not really a Disparate at all. He inclines towards the same idealistic and volar", of which there is a copy in the LAzaro collection at Madrid. Finally, in the Disparates themselves, Goya again uses flying to suggest violent passions in No. 5 ("Disparate volante"), in which an evil-looking bird bears a horseman into the blackness. Admittedly it would be wrong to equate "Modo de volar" with the man-into-beast etchings which preceded it. Nevertheless, Goya's earlier treatment of flying, and the night- quality of the Disparates as a group, suggest that Romantic approach to the work as Blamiremare Young thelatter more pessimistic interpretation is nearer the truth. (The Proverbs of Goya, London, 1923, p. 55). The sees the winged figure in the foreground as "a muscular, 33 The plates without frames are Nos. I9, 23, 27, 28, fearless, clean-living man, with strong resolute 29, features, 31 and 32. No. 14 has only a very narrow frame. As head". will be seen, these are the ones which Lefort determined mouth and well-shaped intellectual picked out as stylistically different from the rest. Since For him this figure represents "the higher development plates of humanity that Goya knew"; all the flyingthe men are dated 1815 are among them, and since they areIn uniformly darker in tone than the rest, it is tempt"fixed by the same enthusiasm for discovery". fact there is absolutely nothing to support this kinding of to view. place them later. They appear more obviously dark in spirit also, and contain some of the most The etching makes no overt statement about the barbaric-looking bull-fighters. At the same time it morals ("clean-living") or the aspirations ("enthusiasm cannot be said that Goya's critical approach is confor discovery") of the men depicted: Blamire Young fined to probably finds them because they are the qualities hethem (i.e. is the result of second thoughts). seems to admire in Goya and Spain, whose "inspired Nos. 2, I2 and 26 are equally direct in underlining the brutality and magnificent brutality" he singles out for praise in and coarseness of the features of the bull- his dedication. On the other hand there is little obvious fighters. basis for the unidealistic view of the plate-the "inky 34 Cf. Desastres Pls. 3 ("Lo mismo") and 31 ("Fuerte menace" which Aldous Huxley, for instance, has seen cosa es!") for French soldiers with cross-bands and in the background (cf. his Foreword to The Complete furry headgear respectively. Other parallels with Etchings of Goya, New York, 1943, P. 14). Nevertheless, the Desastres have already been noted by critics. Since when we compare the plate with others by Goya which Gautier's article in the Gazette des Beaux-Arts, Goya's treat flying subjects, Huxley's "menacing" view seems Moors have often been associated with the Mamelukes, more probable than Cam6n Aznar and Young's "higher development of humanity" conception. In the Caprichos, for instance, apart from the plates which associate flying with witchcraft and evil, we find men turned into eagle-like birds of prey by reason of their which figure in related paintings if not in the Desastres themselves. And Lafuente Ferrari has connected P1. 8 of the Tauromaquia with one of the preliminary drawings for the series (cf. Toros). It is perhaps worth noting that some of the men in the group at the left of passions and sensuality (No. 72, "No te escapards"). the preliminary drawing for P1. I7 of the Tauro- And in the Desastres, bird-men are again essentially evil maquia are not unlike French soldiers. Such apparent and predatory, as in Nos. 71 ("Contra el bien general") parallels would certainly tend to accentuate the sense and 72 ("Las resultas"). No. 72, indeed, is slightly of human barbarity in the Art of bull-fighting for Goya's similar in its treatment of patterns of black wings, to the black-on-white-background version of "Modo de contemporaries. *3 A similar figure reappears in P1. 36 C and its This content downloaded from 201.82.148.205 on Thu, 06 Sep 2018 14:38:24 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms A NEW VIEW OF GOYA'S TAUROMAQUIA 127 possibly also the comic way in which experts the "idea of the origins, progress and present state of bull-fighting" which was supposed to be self-evident in the work. But the critical Plate 30 ;36 certainly the distorted and barbaric faces of bull-fighters and assistants in view apparently expressed would hardly have Plates I8, 19, 24, 26, 28, 31 and 32: allescaped these Goya's enlightened friends. seem to imply criticism of the people involved. The advantages to the present-day reader Finally the treatment of the bull itself, nowview of the Tauromaquia are that it of this pathetically cornered or beaten, now provides heroic- a unifying force for the work, which ally scattering the crowd in the tendido enables or lay- it to be fitted more easily into the ing low Pepe-Hillo, helps to underline the pattern of Goya's etchings. Lafuente general artist's apparent attack on humans in and three phases are reduced to one, and Ferrari's around the bull-ring. his theory that Goya was expressing his revulSuch factors as these seem to the present sion from everyday life by escaping into the writer to add considerable weight to the pastevican be replaced by the view that he was dence of the Ashmolean copy. They attacking cannot the behaviour and nature of manall be explained away in terms of the realism, kind in much the same way as in the Caprichos, lack of documentation or poor attention to and later Disparates.38 If accepted, Desastres detail of the artist. Clearly the fact that there the view would suggest that the Tauromaquia was general support for bull-fightingisat the nearer to the searing attack of the much time of the work's publication may have led Toros de Burdeos in conception than to the Goya to revise slightly the extent of his critipicturesque earlier bull-fighting paintings. cism and to avoid such overt references to Above all, it would give the Tauromaquia a satirical ends as that of the manuscript titlemore universal significance than has generally tell us Pedro Romero holds his sword in been page. Some of the etchings seem more allowed.39 temperate than their preliminary drawings ;37 and the advertisement for the series omits, perhaps prudently, to say what exactly was 38 Already NIGEL GLENDINNING in 1867, Yriarte, referring to the artist of the etchings, could write "I1 n'y a pas dans Goya un preliminary drawing. It is interesting to contrast these philosophe en belle humeur . . . il y a un satirique scenes with Carnicero's treatment of the same subject ardent, qui s'attaque A tout et A tous, toujours pr&t A in his Coleccidn de las principales suertes de una corrida de mordre, mais pour faire une morsure empoisonn6e." toros. Carnicero shows the bull erect in the act of toss(Goya, Paris, 1867, p. 102.) The theory that the series ing a dog with his horns, and trampling another under of etchings were all related to crises in the life of Goya foot, while other dogs and men look on. Goya, on the was first advanced by Manuel G6mez-Moreno in his other hand, shows the bull crouching down, with head article "Las crisis de Goya" in the Revista de la Biblioteca, low, surrounded by aggressive and apparently large Archivoy Museo, 1935, I. So far as Goya's view of bulldogs-altogether a more sympathetic and tragic treatfighting in the other series of etchings is concerned, it ment of the bull's position. is interesting to note that he uses it as an allegory for 36 Lafuente does not accept Bargiit's criticism human of barbarity in the Caprichos (77, "Unos a otros"), Goya's P1. 30 (Archivo, p. 205). In fact, the positionillustrating of the way in which men struggle bitterly and the hand is not very different from that of the matador unceasingly for superiority over others. In the Dis- in P1. X of Carnicero's series. parates, also, we find a similar conception of bulls to "7 This is not always the case: the increased detail that of the Tauromaquia. The two animals which are of the faces in Pls. I8, 19, 20, 26 and 31, adds tolooking towards us in No. 21, "Disparate de toritos", their critical force. But the figure with the sword is have much the same expression of fear in their eyes as more violent in the drawing for P1. 3 than in the etchthe bull in Pl. 3 of the Tauromaquia. The blackness ing, although the bull is less obviously suffering; the around the bulls and the animal on the right falling Spanish nobleman in the drawing for Pl. 9 is more helplessly into the void reinforces the view that their bizarre than in the plate itself; there is more sense of situation, here as in the Tauromaquia, is basically tragic. violence in the drawing for P1. 12 than in the etching; 9 Cf. Aldous Huxley, Foreword to The Complete less urbanity in the face of the nobleman in the drawing Etchings of Goya, New York, 1943, p. I I. ("For the non- for P1. 13; a more vapid expression on the face of "la Spaniard the plates . . . will probably seem the least c6lebre Pajuelera" in the drawing for P1. 22. interesting of Goya's etchings . .") This content downloaded from 201.82.148.205 on Thu, 06 Sep 2018 14:38:24 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms