Do Hedonic and Utilitarian Apps Differ

in Consumer Appeal?

Bidyut Hazarika ✉ , Jiban Khuntia, Madhavan Parthasarathy,

and Jahangir Karimi

(

)

Business School, University of Colorado Denver, 1475 Lawrence Street,

Denver, CO 80202, USA

{bidyut.hazarika,jiban.khuntia,madhavan.parthasarathy,

jahangir.karimi}@ucdenver.edu

Abstract. This research in progress suggests that hedonic and utilitarian mobile

applications (apps) differ in consumer appeal. We operationalize consumer appeal

through addiction, frustration and consumer value perception. The interplay of

frustration in the presence of a set of addicted customers is interesting, as many

apps may have an addicted consumer baser-specifically for games, communica‐

tions of or entertainment apps. Consumer frustration may act as a negative

complementing factor to consumer addiction, and this substitution effect is argued

to be higher for hedonic products than utilitarian products. Hypotheses are drawn

and a methodology is suggested. Possible implications and contributions are

discussed.

Keywords: Consumer addiction · Consumer frustration · Digital products ·

Apps · Hedonic · Utilitarian · Consumer evaluation

1

Introduction

Continuous development in mobile technologies and related applications (apps) has

emerged to converge in the apps market space. Starting with a handful of apps in 2008,

the Apple Store has more than a million apps for sale in 2015. Similar trends are observed

in the Android and Microsoft apps stores as well. Many companies are using mobile

apps as traditional trade channels. Revenue from app users is projected to increase from

$10.3 billion in 2013 to $25.2 billion in 2017 [5].

In this study, we propose to explore how hedonic and utilitarian apps differ in

consumer appeal. We posit that consumer appeal is reflected by addiction, frustration

and value perception, amongst other factors. We ask the research question how the

relationships of consumer addiction and frustration on consumer evaluation is differen‐

tiated by hedonic and utilitarian apps. Based on prior studies [13], we denote the term

hedonic to those apps that “aim to provide self-fulfilling value to the user”; whereas

utilitarian apps “aim to provide instrumental value to the user”. A conceptual model is

suggested with possible avenues for data collection and research execution. Possible

contributions and implications are discussed.

© Springer International Publishing Switzerland 2016

V. Sugumaran et al. (Eds.): WEB 2015, LNBIP 258, pp. 233–237, 2016.

DOI: 10.1007/978-3-319-45408-5_28

234

2

B. Hazarika et al.

Conceptual Development and Hypotheses

Existing information systems has differentiated the hedonic and utilitarian use of infor‐

mation technology, through the lens of usage behavior as a result from a reasoned

appraisal of pre-adoption beliefs of the IT artifact [9]. A few studies have extended the

hedonic and/or utilitarian lens to mobile computing (e.g. [11]) and other general IT

products (e.g. [8]).

Addiction is the use of something for relief, comfort, or simulation, and which often

continues in part, due to cravings when it is absent and has affected people’s life in

various ways and some people may require treatment [14]. When someone becomes

dependent on a certain type of technology and have to use it repeatedly, it becomes a

behavioral addiction [4]. The existence of such addiction to digital artifacts has been

proven by Turel and Serenko [10].

Addiction is a trait when a consumer gets obsessed with a certain product and keeps

using it repeatedly over and over again. In case of apps, if a consumer keeps checking

an app repeatedly to check its content, we can classify them as addiction. This repeated

use of the app leads to eventual addiction of the consumer. Consumer addiction indicates

not only the liking of consumers for an app due to its appeal, function or on the attribute

to meet a specific unique need; but also that the app has the potential to be sustained in

the market due to a set of addicted consumers. For example, a fitness app would have a

good appeal for the consumer segment that want to stay fit, and hence, would have

generated a set of consumers who use and get addicted to it. These addicted consumers

would then derive higher benefits, be testers, will work towards the improvement of the

app by providing feedback and in general help in mitigating the aspects related to the

frustration technology issues. The features such as an app having a great design, inte‐

gration, functionality contributes towards the addiction. An app in a work place works

smoothly as advertised can lead to greater productivity and utilization from its workers

resulting in good evaluations, leading to positive word of mouth and better customer

evaluation.

Consumer frustration is the result of the failure a consumer faces when a technology

fails to achieve its desired task. In an individual level, consumer frustration can be

defined as the negative emotion due to an unsuccessful use of a technology [1]. In case

of an app, the main cause of consumer frustration is inaccurate description, not enough

engagement, not user friendly, crash and other usage problems. Consumer frustration

leads to dissatisfaction, and loss of self-efficacy and eventually lead to consumer unin‐

stalling the app and leaving a bad review. Consumer frustration may also lead to disrup‐

tion in workplace, slow functionalities and not using the app [6] or also may lead to high

levels of anxiety and anger on part of the user [12] eventually leading the user to stay

away from the technology [7]. As pointed out by Guchait and Namasivayan [2], all the

above mentioned factors create a bad response for the technology in the market.

Consumer frustration deals with the negative emotions that individuals feel with the

use of technology. In the context of apps, if an app doesn’t perform as it is supposed to,

it leads to consumers discontinuing the app, or being dissatisfied by the app. The

performance of the app in this study is based on the factors such as crash, design, usage,

integration and functionality issues. Prior studies note that consumer frustration leads

Do Hedonic and Utilitarian Apps Differ in Consumer Appeal?

235

to loss of the users’ self-efficacy and subsequent personal dissatisfaction. For example,

when the user used an app for a game or to stream a movie, and the app fails or crashes;

then it leads to discontinuation of the game or the movie, leading to dissatisfaction of

the user. Similarly, an apartment finder app, or a business networking app, if do not work

properly as desired, lead to failure of the business and loss of productivity and revenue.

Often the resulting negative word-of-mouth from dissatisfied users will lead to less

adoption of the app which in turn will lead to decrease the consumer evaluation of the

app, finally leading to the death of the app. Prior studies (e.g. [2, 3]) note that the frus‐

tration felt by consumers when shared in a public forum creates a negative image of the

product in the market.

Based on the discussions in the existing literature, as elaborated in previous para‐

graphs, we develop a conceptual model for this study. Figure 1 below shows the

proposed conceptual model. We posit that addiction and frustration have direct effects

on consumer evaluation of an app. However, these direct effects being not so surprising,

we do not hypothesize those, and focus on the differentiating hypotheses of hedonic and

utilitarian apps.

Fig. 1. Conceptual model

When people decide to use an app, it can be due to two values: utilitarian and hedonic

behavior. Utilitarian behavior is more relational and task related. We classify utilitarian

apps as those apps that are used by consumers in an effective manner. For example, apps

that are downloaded to track finances, medical records are all classified as utilitarian

apps: apps that are used to achieve certain tasks. Hedonic apps on the other hand are

apps that are used for fun and playfulness vs. task completion. Thus, we posit that

hedonic apps are mostly used by consumers for entertainment value such as: arousal,

heightened involvement, perceived freedom, fantasy fulfillment and escapism.

Hedonic apps will have more success as they are more likely to be used more often

compared to utilitarian apps. The degree of addiction will also be high for these apps as

well. If hedonic apps works seamlessly, the consumer evaluation will be much higher

as people would have greater evaluation for these apps. In case of utilitarian apps, people

use them only to achieve certain task and not for its enjoyment value. So, if a utilitarian

app crashes or have technical glitches, consumer will be more forgiving compared to a

hedonic app. Based on these arguments, we hypothesize that:

236

B. Hazarika et al.

H1a: The positive effect of consumer addiction on consumer evaluation is higher for

hedonic apps than utilitarian apps.

H1b: The negative effect of consumer frustration on consumer evaluation is higher for

hedonic apps than utilitarian apps.

3

Proposed Method and Discussion

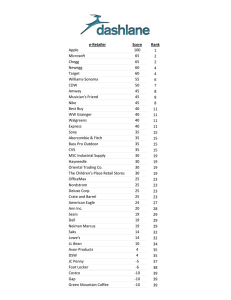

This research in progress suggests to collect secondary data for several weeks, code the

variables using text mining and analyze the data using econometric methods. We expect

to find support for the hypotheses. We also plan to conduct a set of robustness tests to

validate our findings.

This study aims to report the findings on whether consumer frustration has a negative

association on consumer evaluation, whether the interaction of addiction and frustration

has differentiating effects on consumer evaluation for hedonic and utilitarian apps.

The findings would inform managers to focus on design aspects, such as app designs

can be oriented to have more “hedonist” design aspects, even though they have utilitarian

value. Further, the study would inform managers that technical design and integration

plays a highly valuable role in consumer acceptance of the app. Finally, as much as an

app’s release is important, taking feedback from consumers and tracking evaluation

regularly (almost on a daily basis) is critical for an app’s success.

In terms of research contributions, this study as of now is the first one to explore the

comparative effects of consumer behavioral factors associated with apps adoption; with

a set of nuanced variables such as addiction, frustration associated with hedonic and

utilitarian apps. Further, indirectly this study identifies the important role of design and

evaluation factors associated with IT business value, specifically in the apps market

context. Moreover, it also informs to the vast literature in the marketing on the product

feature or aspects that influences consumer evaluation of products.

In conclusion, the objective of this study is to explore to what extent consumer

addiction and consumer frustration influences consumer evaluation of apps; and how

these effects differ across utilitarian and hedonic apps. We propose to analyze secondary

data for android apps and to validate the model and hypotheses. This study contributes

to the research on the digital business strategy for apps markets.

References

1. Bessière, K., Newhagen, J.E., Robinson, J.P., Shneiderman, B.: A model for computer

frustration: the role of instrumental and dispositional factors on incident, session, and postsession frustration and mood. Comput. Hum. Behav. 22(6), 941–961 (2006)

2. Guchait, P., Namasivayam, K.: Customer creation of service products: role of frustration in

customer evaluations. J. Serv. Market. 26(3), 216–224 (2012)

3. Hazarika, B., Karimi, J., Khuntia, J., Parthasarathy, M.: Consumer Frustration and Consumer

Valuation Shift for Mobile Apps: An Exploratory Study (2015)

4. Holden, C.: ‘Behavioral’ addictions: do they exist? Science 294(5544), 980–982 (2001)

5. IDC.: Worldwide and U.S. Mobile applications download and revenue 2013–2017 forecast:

The app as the emerging face of the internet (2013)

Do Hedonic and Utilitarian Apps Differ in Consumer Appeal?

237

6. Lazar, J., Jones, A., Hackley, M., Shneiderman, B.: Severity and impact of computer user

frustration: a comparison of student and workplace users. Interact. Comput. 18(2), 187–207

(2006)

7. Lenhart, A.: The Ever-Shifting Internet Population: A New Look At Access and the Digital

Divide. Pew Internet & American Life Project, Washington, D.C. (2003)

8. Lin, C.P., Bhattacherjee, A.: Extending technology usage models to interactive hedonic

technologies: a theoretical model and empirical test. Inf. Syst. J. 20(2), 163–181 (2010)

9. Mallat, N.: Exploring consumer adoption of mobile payments–a qualitative study. J. Strateg.

Inf. Syst. 16(4), 413–432 (2007)

10. Turel, O., Serenko, A., Bontis, N.: User acceptance of hedonic digital artifacts: a theory of

consumption values perspective. Inf. Manag. 47(1), 53–59 (2010)

11. Wakefield, R.L., Whitten, D.: Mobile computing: a user study on hedonic/utilitarian mobile

device usage. Eur. J. Inf. Syst. 15(3), 292–300 (2006)

12. Wilfong, J.D.: Computer anxiety and anger: the impact of computer use, computer experience,

and self-efficacy beliefs. Comput. Hum. Behav. 22(6), 1001–1011 (2006)

13. Wakefield, R.L., Whitten, D.: Mobile computing: a user study on hedonic/utilitarian mobile

device usage. Eur. J. Inf. Syst. 15(3), 292–300 (2006)

14. Young, K.S.: Internet addiction: the emergence of a new clinical disorder. Cyber Psychol.

Behav. 1(3), 237–244 (1998)