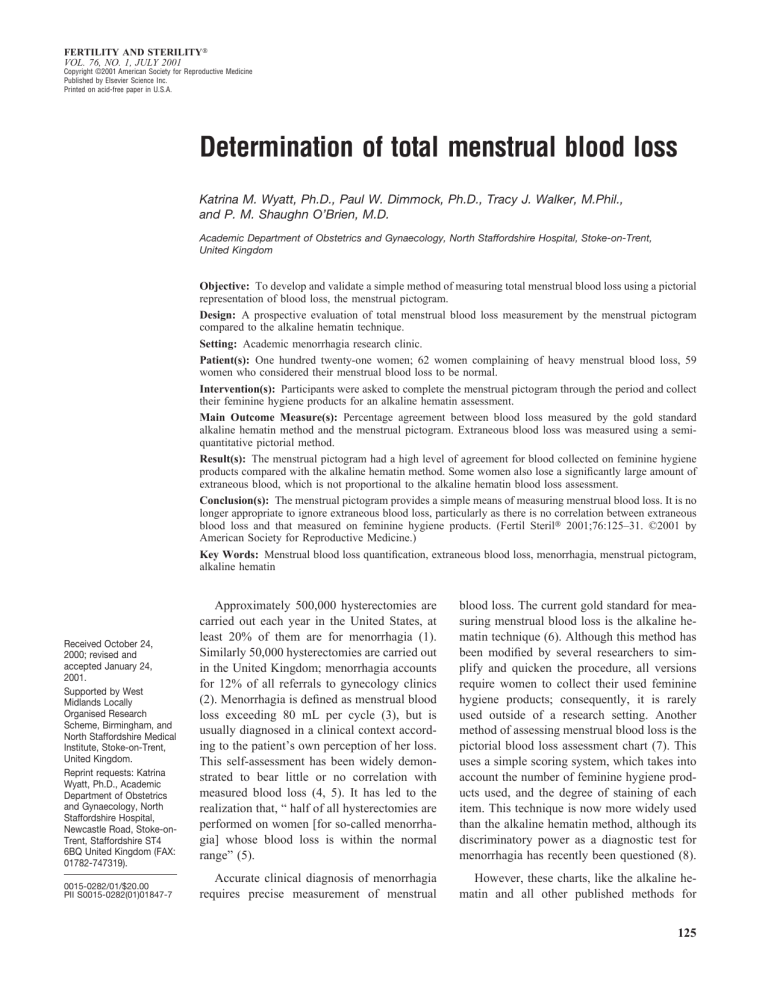

FERTILITY AND STERILITY威 VOL. 76, NO. 1, JULY 2001 Copyright ©2001 American Society for Reproductive Medicine Published by Elsevier Science Inc. Printed on acid-free paper in U.S.A. Determination of total menstrual blood loss Katrina M. Wyatt, Ph.D., Paul W. Dimmock, Ph.D., Tracy J. Walker, M.Phil., and P. M. Shaughn O’Brien, M.D. Academic Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, North Staffordshire Hospital, Stoke-on-Trent, United Kingdom Objective: To develop and validate a simple method of measuring total menstrual blood loss using a pictorial representation of blood loss, the menstrual pictogram. Design: A prospective evaluation of total menstrual blood loss measurement by the menstrual pictogram compared to the alkaline hematin technique. Setting: Academic menorrhagia research clinic. Patient(s): One hundred twenty-one women; 62 women complaining of heavy menstrual blood loss, 59 women who considered their menstrual blood loss to be normal. Intervention(s): Participants were asked to complete the menstrual pictogram through the period and collect their feminine hygiene products for an alkaline hematin assessment. Main Outcome Measure(s): Percentage agreement between blood loss measured by the gold standard alkaline hematin method and the menstrual pictogram. Extraneous blood loss was measured using a semiquantitative pictorial method. Result(s): The menstrual pictogram had a high level of agreement for blood collected on feminine hygiene products compared with the alkaline hematin method. Some women also lose a significantly large amount of extraneous blood, which is not proportional to the alkaline hematin blood loss assessment. Conclusion(s): The menstrual pictogram provides a simple means of measuring menstrual blood loss. It is no longer appropriate to ignore extraneous blood loss, particularly as there is no correlation between extraneous blood loss and that measured on feminine hygiene products. (Fertil Steril威 2001;76:125–31. ©2001 by American Society for Reproductive Medicine.) Key Words: Menstrual blood loss quantification, extraneous blood loss, menorrhagia, menstrual pictogram, alkaline hematin Received October 24, 2000; revised and accepted January 24, 2001. Supported by West Midlands Locally Organised Research Scheme, Birmingham, and North Staffordshire Medical Institute, Stoke-on-Trent, United Kingdom. Reprint requests: Katrina Wyatt, Ph.D., Academic Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, North Staffordshire Hospital, Newcastle Road, Stoke-onTrent, Staffordshire ST4 6BQ United Kingdom (FAX: 01782-747319). 0015-0282/01/$20.00 PII S0015-0282(01)01847-7 Approximately 500,000 hysterectomies are carried out each year in the United States, at least 20% of them are for menorrhagia (1). Similarly 50,000 hysterectomies are carried out in the United Kingdom; menorrhagia accounts for 12% of all referrals to gynecology clinics (2). Menorrhagia is defined as menstrual blood loss exceeding 80 mL per cycle (3), but is usually diagnosed in a clinical context according to the patient’s own perception of her loss. This self-assessment has been widely demonstrated to bear little or no correlation with measured blood loss (4, 5). It has led to the realization that, “ half of all hysterectomies are performed on women [for so-called menorrhagia] whose blood loss is within the normal range” (5). blood loss. The current gold standard for measuring menstrual blood loss is the alkaline hematin technique (6). Although this method has been modified by several researchers to simplify and quicken the procedure, all versions require women to collect their used feminine hygiene products; consequently, it is rarely used outside of a research setting. Another method of assessing menstrual blood loss is the pictorial blood loss assessment chart (7). This uses a simple scoring system, which takes into account the number of feminine hygiene products used, and the degree of staining of each item. This technique is now more widely used than the alkaline hematin method, although its discriminatory power as a diagnostic test for menorrhagia has recently been questioned (8). Accurate clinical diagnosis of menorrhagia requires precise measurement of menstrual However, these charts, like the alkaline hematin and all other published methods for 125 quantifying menstrual blood loss, fail to measure extraneous blood loss, that is, blood not collected on feminine hygiene products. Anecdotal evidence suggests that this is the component of menstruation that women find most distressing, leading to the request for hysterectomy. Only one technique has attempted to address the measurement of this extraneous loss: the menses cup or gynaeseal is a latex menstrual diaphragm that was designed to collect total blood loss (9, 10). However, because up to 20% of the collected blood is spilled during removal of the diaphragm, the method is considered unsuitable for either clinical or research use. In clinical practice, the diagnosis of heavy menstrual bleeding remains dependent on the patient’s perception of her loss. Yet, some studies have shown that objective measurement of menstrual blood loss and informing the patient that her loss is within the normal range can be sufficient for some women to no longer seek medical or surgical treatment (11, 12). Much has been written about factors, which may influence an individual patient’s perception of menstrual blood loss volume. Duration of menses, age, number of feminine hygiene products used, menstrual incontinence, flooding, and accidents may all influence how heavy a woman perceives her blood loss to be (4, 5). A recent article by Higham and Shaw (13) found an association between height, age, parity, and blood loss, but concluded that objective measurement was still required. It has also been suggested that the complaint of menorrhagia is not always an organic disease and for some women there may be important psychosomatic elements (14, 15). Greenburg (14) found that women who presented with menorrhagia were more likely to be depressed, whereas Sainsbury (15) reported that they were more likely to have higher scores for neuroticism and lower extraversion scores. However, neither investigator related the psychiatric assessment of the women with an objective measurement of menstrual blood loss. Granlesse (16), who objectively measured menstrual blood loss (using the alkaline haematin), found no difference in personality characteristics between women presenting with menorrhagia whose menorrhagia was confirmed and those whose blood loss was less than 80 mL. It has yet to be determined whether the patients with blood loss less than 80 mL, but who believe they have heavy periods, comprise the group with psychological morbidity, although this seems likely. It has been suggested that it is the extraneous loss that is often the primary reason given by women presenting with menorrhagia; a recent article by Hurskainen et al. (17) states that the failure to assess total blood loss could “systematically underestimate” the proportion of women with heavy menstrual bleeding. This would inappropriately suggest that these women have menstrual intolerance and potentially label them as having a psychological disorder that could deprive them of the necessary treatment. We have developed a new quantitative method of mea126 Wyatt et al. Determination of total menstrual blood loss suring total menstrual blood loss, the menstrual pictogram, which addresses many of the shortcomings of previous methods. Our principal aims were to validate the new menstrual pictogram icons for feminine hygiene products against the alkaline hematin method, to quantify extraneous blood lost when changing feminine hygiene products, and to try and determine why women whose measured blood loss is less than 80 mL believe they have menorrhagia. Participants and Methods This study was approved by the Scientific Merit Committee and the Research Ethics Committee of the North Staffordshire Hospital NHS Trust. All participants gave their informed, written consent. Women presenting with a stated symptom of menorrhagia were recruited from the gynecologic outpatients clinics of North Staffordshire Hospital. To obtain a well-balanced distribution of menstrual blood loss, women requesting sterilization and healthy volunteers who considered their blood loss to be normal were also invited to participate. Participants were provided with branded feminine hygiene products (Tampax regular, super, or super plus and Kotex Maxi super or Maxi nighttime napkins) and an airtight container for their collection. They were given the menstrual pictogram and instructed how to complete it. The menstrual pictogram contains pictorial representations of graded staining from slight to severely stained sanitary napkins and tampons (Fig. 1). In addition to scoring each sanitary item women were also asked to distinguish whether it was a daytime or nighttime napkin and whether the tampon was regular, super, or super plus, all of which have different absorption characteristics. Icons representing blood lost as clots as well as that lost when changing feminine hygiene products were also included in the menstrual pictogram. Extraneous blood loss was estimated using three pictogram representations of slight, moderate, and severe blood loss when changing feminine hygiene products. Participants were instructed to mark down the loss each time they changed their napkin or tampon. Three visual analog scales were included to quantify the woman’s perception of her bleeding, whether she had flooding episodes and whether her bleeding prevented her from carrying out her usual activities. At the end of their period women returned to the Menorrhagia Research Clinic with the completed menstrual pictogram and the soiled feminine hygiene products. Venous blood (3 mL) was then taken from each participant. The blood content of the feminine hygiene products was quantified using the alkaline hematin method described by Hallberg and Nilsson (6). A scoring system for the feminine hygiene product icons was devised (Fig. 1). Small, medium, and large clots were scored as 1, 3, and 5 mL, respectively. A semiquantitative method for measuring extraneous blood loss was devised. Known volumes of expired venous blood Vol. 76, No. 1, July 2001 FIGURE 1 Assessment of menstrual blood loss using the menstrual pictogram. The scores (in milliliters) associated with each icon are given. Left: sanitary napkins. Right: tampons. Wyatt. Determination of total menstrual blood loss. Fertil Steril 2001. were added to lavatory basins and 25 female volunteers, with a range of measured menstrual blood loss, were asked to score the resulting color as A, B, or C (Fig. 2). This was repeated for different designs of lavatory basins. The volumes that the volunteers associated with each icon were then averaged and the standard deviation was subtracted from the mean to give a conservative estimate of extraneous blood loss. This resulted in a score of 1, 3, and 5 mL being assigned to icon A, B, and C, respectively (Fig. 2). The scores from the menstrual pictogram icons for feminine hygiene products only (and not for the icons for extraneous blood loss) were compared with the blood loss measured by the alkaline hematin technique. The volume measured on the feminine hygiene product was compared to the extraneous blood loss. Statistical Analysis The scores from the menstrual pictogram and the blood loss measured by the alkaline hematin method were compared using the technique of measure of agreement, described by Bland and Altman (18). The statistic was used to generate a percentage agreement between the two techniques. A value ⬍0.2 indicates poor agreement, whereas FERTILITY & STERILITY威 ⬎0.8 indicates very good agreement, significantly beyond chance. A Spearman rank correlation coefficient was used to determine correlations between data. When comparisons were made between subgroups statistical significance was assessed by a 2 test, P⬍.05 was considered to be significant. Definitions of Menorrhagia Complaint of menorrhagia (CM) is all women presenting at clinic with a symptom of menorrhagia; verified menorrhagia (VM) is women presenting with menorrhagia that is confirmed using the alkaline hematin method; and refuted menorrhagia (RM) is women presenting with menorrhagia but whose measured loss is ⬍80 mL using the alkaline hematin method. RESULTS One hundred twenty-one women were recruited to the study. This included 62 who presented at the clinic with CM and 59 self-defined controls, who considered their blood loss to be normal. Thirteen of the women failed to complete the study. Of these, one (menorrhagia patient) used her usual 127 FIGURE 2 Icons representing extraneous blood loss and the mean scores derived for each icon. Wyatt. Determination of total menstrual blood loss. Fertil Steril 2001. brand of feminine hygiene products and not that provided for the study, and 12 (controls) failed to collect all their feminine hygiene products. The mean age of the 61 women presenting with menorrhagia was 39 years (range 25–50 years). The mean age of the control group was 37 years (range 22–51 years). The ages of the women who failed to complete the study were not significantly different to those who completed it. Scores for Feminine Hygiene Products Only The menstrual pictogram scores for feminine hygiene products only for the CM group ranged (CM) from 15 to 456.5 mL (median 67 mL) and from 7 to 159 mL (median 31 mL) for the control group. The alkaline hematin measurements ranged from 8 to 606 mL (median 68 mL) for the women presenting with menorrhagia and from 4 to 184 mL (median 36 mL) for the self-defined controls. Of the 61 women who presented with CM, 22 had VM and 39 had RM as determined by the alkaline hematin assessment. The RM group had alkaline hematin scores that ranged from 8 to 78 mL (median 42 mL) and from 15 to 124 mL (median 55 mL) assessed by the menstrual pictogram (feminine hygiene product icons only). Six of the 47 self-defined normal controls had menorrhagia as determined by the alkaline hematin. The agreement between the scores from the menstrual pictogram icons for feminine hygiene products and the alkaline hematin is shown in Figure 3. The menstrual pictogram had a sensitivity of 86% and specificity of 88% in diagnosing menorrhagia (as defined by the alkaline hematin method). The associated statistic for the comparison between the feminine hygiene product icons and the alkaline hematin assessment was 0.8. 128 Wyatt et al. Determination of total menstrual blood loss Scores for Extraneous Blood Loss The volume of extraneous blood (as assessed by the pictogram) ranged from 1 to 245 mL (median 49 mL) for the CM group and from 0 to 96 mL (median 12 mL) for the self-defined control group. When the extraneous blood loss was taken into account, the group presenting with menorrhagia had a median total blood loss (alkaline hematin measurement plus extraneous blood loss) of 109 mL (range 15 to 836 mL), whereas the median total blood loss for the control group was 48 mL (range 4 to 211 mL). When the values calculated for extraneous blood loss were added to the volume of blood collected on feminine hygiene products (as assessed by the alkaline hematin), 45 of the 61 women who had initially presented with menorrhagia then had blood loss that exceeded 80 mL. (This compares with 22 of the CM group when extraneous blood loss was not considered.) The inclusion of extraneous blood loss increased the number of women whose blood loss exceeded 80 mL in the control group from 6 to 10. There was no correlation between the amount of blood collected on feminine hygiene products (as assessed by either technique) and extraneous blood loss, r ⫽ 0.58 (Fig. 4). There also was no correlation when the women were divided into groups according to their initial belief and subsequent objective measurement (Table 1). There was no correlation between the number and severity of accidents reported and extraneous blood loss for any of the groups (Table 1). The incidence of menstrual accidents was higher in the CM group than in the control group; the group that reported the highest number of accidents was the group whose menorVol. 76, No. 1, July 2001 FIGURE 3 Difference between menstrual pictogram and alkaline hematin blood loss measurement against mean score. Horizontal dotted lines denote 2 SD. Wyatt. Determination of total menstrual blood loss. Fertil Steril 2001. rhagia was verified by the alkaline hematin assessment (VM). Table 2 details the medians and ranges for the measured variables for the two groups of women presenting at clinic with menorrhagia. Of the RM group 78% stated that their bleeding was heaviest on the same day that they lost the most blood extraneously, compared with 66% of the VM group (P ⫽ .22). Also of the RM group 66% stated that the day their bleeding most prevented them from carrying out their usual activities was the same day that they lost the most blood extraneously, compared with only 48% of the VM group (P ⫽ .20). Similarly 66% of the RM group stated the day they suffered the worst episodes of flooding was the day that TABLE 2 TABLE 1 Correlation coefficients for variables possibly related to extraneous blood loss. Menorrhagia Alkaline haematin vs. extraneous blood Number of reported accidents vs. extraneous blood ⬎80ml ⬍80ml ⬎80ml r ⫽ 0.64 r ⫽ 0.115 r ⫽ 0.205 r ⫽ 0.222 r ⫽ 0.379 r ⫽ 0.139 r ⫽ 0.34 r ⫽ 0.19 FERTILITY & STERILITY威 Subjective menorrhagia Control ⬍80ml Wyatt. Total menstrual blood loss. Fertil Steril 2001. Possible factors influencing perception of menstrual blood loss for women presenting at clinic with menorrhagia. Results are presented as medians and ranges. Age (y) No. days bleeding No. accidents No. items sanitary wear No. items sanitary wear/measured mbl 37 (26–49) 4 (2–9) 3 (0–27) 16.5 (9–31) 2.45 (0.5– 8.3) Objective menorrhagia 41 (32–50) 6 (3–7) 9 (0–29) 29 (15–70) 6.3 (2.5– 11.0) Wyatt. Total menstrual blood loss. Fertil Steril 2001. 129 FIGURE 4 Correlation between extraneous blood loss and blood loss measured by the alkaline hematin (r ⫽ 0.58). Wyatt. Determination of total menstrual blood loss. Fertil Steril 2001. their extraneous blood loss was heaviest, this compares with 50% of the VM group (P ⫽ .2). DISCUSSION We have developed a new method to assess total menstrual blood loss, the menstrual pictogram. This consists of pictorial representations of soiled sanitary protection, clots and icons representing the volume of blood lost when changing feminine hygiene products. We have shown that the icons for feminine hygiene products have a high level of correlation and agreement with the alkaline hematin method. The menstrual pictogram is more accurate than the original pictorial blood loss assessment charts (7), this is probably due to an increased range of icons as well as making the distinction between the differing levels of absorbency of blood into the napkins and tampons. Although the menstrual pictogram has been validated for a single brand of sanitary napkin and tampon for the purpose of this project, calculation of correction factors for the leading other brands of sanitary protection are underway for subsequent use in the clinical setting. In 36% of the 61 women presenting with the complaint of menorrhagia, the complaint was objectively verified by the alkaline hematin method. Previously published studies quote between 38% and 53% of women presenting menorrhagia having objective menorrhagia (4, 5, 8, 13). In general women with heavier blood loss used a greater number of feminine hygiene products but in agreement with other studies we found no overall correlation between the number of feminine hygiene products used and blood loss. An extreme example being one woman who collected 210 mL on 15 130 Wyatt et al. Determination of total menstrual blood loss napkins and another who used 18 napkins to collect only 34 mL. When the volume of extraneous blood loss was taken into account, the number of women with ⬎80 mL total menstrual blood loss increased to 45 (corresponding to 74% of those women who originally presented with menorrhagia). The original cutoff point of 80 mL for menorrhagia is based on the alkaline hematin assessment of blood loss on feminine hygiene products in a population (3). It will now be necessary to redefine the upper limit of normal in population studies based on total loss. Although the women in this study who suffered very heavy blood losses tended to lose a greater volume of extraneous blood, there was no overall correlation between the amount of blood collected on feminine hygiene products and the amount of extraneous blood loss. Even when the menorrhagia and the control groups were divided according to their objective blood loss assessment into groups with loss ⬎80 mL and ⬍80 mL, no agreement could be found (Table 1). It would also appear to be insufficient to question women about the number of accidents as an indication of extraneous blood loss. Several factors that could influence the perception of blood loss were studied in the women presenting with menorrhagia. There was no significant difference in age between the VM group and the RM group. There also were no significant differences in the duration of bleeding between these two groups. Women with RM could not attribute their perceived heavy blood loss to the number of sanitary items used, as this group used significantly fewer feminine hygiene Vol. 76, No. 1, July 2001 products than the VM group. Similarly, they reported fewer menstrual accidents than the women with VM (Table 2). The women in the study were asked to record their perception of how heavy their blood loss was each day during menstruation. Women whose menorrhagia was not objectively confirmed tended to state that the day their bleeding was heaviest was the same day that they had the greatest blood loss extraneously, although this was also true for the VM group, the overall agreement was not as good. Similarly, these women also perceived the day that their bleeding prevented them carrying out their usual activities to the greatest extent was the day their extraneous blood loss was greatest. Again this was more likely to occur for women with RM rather than CM. Although it is possibly naı̈ve to believe that it is solely the extraneous blood loss that causes women to seek help for menorrhagia, it is clearly an important and significant factor in determining how women perceive their blood loss. Failure to assess extraneous blood loss will significantly underestimate the volume of blood lost each cycle. This could mean that women may not receive the appropriate treatment or worse, that they are labeled as depressed or neurotic for a condition that they genuinely have. In conclusion, we have developed a simple means of quantifying total menstrual blood loss. The icons for feminine hygiene products in the menstrual pictogram have a high level of agreement with the alkaline hematin method. The menstrual pictogram has another significant advantage of providing a semiquantitative estimate of extraneous blood loss. The measurement of total blood loss would allow women to make a more informed choice about the appropriate treatment options. As the knowledge that their measured blood loss is normal is sufficient for some women to no longer seek medical or surgical therapy, there is support for menstrual blood loss assessment becoming a routine procedure (11, 12). In a study looking at outcome after endometrial ablation, women with VM had better outcomes than those with RM (19). The menstrual pictogram could easily be used in primary and secondary care as a simple, effective method of diagnosing heavy menstrual bleeding, which will improve clinical treatment decisions and could result in improved outcomes from any treatment. The validation of the menstrual pictogram will allow us to undertake studies to determine total objective blood loss in a normal population. This population-based blood loss study will necessarily include patient perception of blood loss, quality of life, and hemato- FERTILITY & STERILITY威 logic parameters. It will permit us to define new limits for normal and abnormal menstruation and propose a more clinically relevant, quantitative, definition of menorrhagia for research and evaluating treatment. Acknowledgments: The authors are grateful to the West Midlands Locally Organised Research Scheme and North Staffordshire Medical Institute for the support of the research fellow and research assistant (KMW and TJW) throughout. References 1. Hidlebaugh DA, Orr RK. Long-term economic evaluation of resectoscopic endometrial ablation versus hysterectomy for the treatment of menorrhagia. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laprascop 1998;5:351– 6. 2. Coulter A, Bradlow J, Agass M, Martin-Bates C, Tulloch A. Outcomes of referrals to gynaecology outpatient clinics for menstrual problems; an audit of general practice records. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1991;98: 789 –96. 3. Hallberg L, Hogdahl A, Nilsson L, Rybo G. Menstrual blood loss—a population study. Acta Obstet Gynaecol Scand 1966;45:320 –51. 4. Chimbira TH, Anderson ABN, Turnbull AC. Study of menstrual blood loss. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1980;87:603–9. 5. Fraser IS, McCarron G, Markham R. A preliminary study of factors influencing perception of menstrual blood loss volume. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1984;149:788 –93. 6. Hallberg L, Nilsson L. Determination of menstrual blood loss. Scand J Clin Lab Invest 1964;16:244 – 8. 7. Higham JM, O’Brien PMS, Shaw RW. Assessment of menstrual blood loss using a pictorial chart. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1990;97:734 –9. 8. Reid PC, Coker A, Coltart R. Assessment of menstrual blood loss using a pictorial chart: a validation study. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 2000;107: 320 –2. 9. Gleeson N, Devitt M, Buggy F, Bonnar J. Menstrual blood loss measurement with gynaeseal. Aust NZ J Obstet Gynaecol 1993;33:79 – 80. 10. Cheng M, Kung R, Hannah M. Menses cup evaluation study. Fertil Steril 1995;64:661–3. 11. Higham JM, Reid P. A preliminary investigation of what happens to women complaining of menorrhagia but whose complaint is not substantiated. J Psychosom Obstet Gynecol 1995;16:211– 4. 12. Rees MCP. Role of menstrual blood loss measurements in the management of complaints of excessive menstrual bleeding. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1991;98:327– 8. 13. Higham JM, Shaw RW. Clinical associations with objective menstrual blood volume. Eur J Obstet Gynecol 1999;82:73– 6. 14. Greenberg M. The meaning of menorrhagia. An investigation into the association between the complaint of menorrhagia and depression. J Psychosom Res 1983;27:209 –14. 15. Sainsbury P. Psychosomatic disorders and neurosis in outpatients attending a general hospital. J Pyschosom Res 1960;4:261–73. 16. Granlesse J. Personality, sexual behaviour and menstrual symptoms: their relevance to clinically presenting with menorrhagia. Person Individ Diff 1990;11:379 –90. 17. Hurskainen RH, Teperi J, Turpeinen U, Grenman S, Kivela A, Kujansuu E, et al. Combined laboratory and diary method for objective assessment of menstrual blood loss. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 1998; 77:201– 4. 18. Bland JM, Altman DG. Statistical method of assessing agreement between two methods of clinical measurement. Lancet 1986;:307–10. 19. Canon MJ, Day P, Hammadieh N, Johnson N. A new method for measuring menstrual blood loss and its use in screening women before endometrial ablation. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1996;103:1029 –33. 131