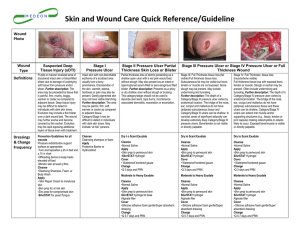

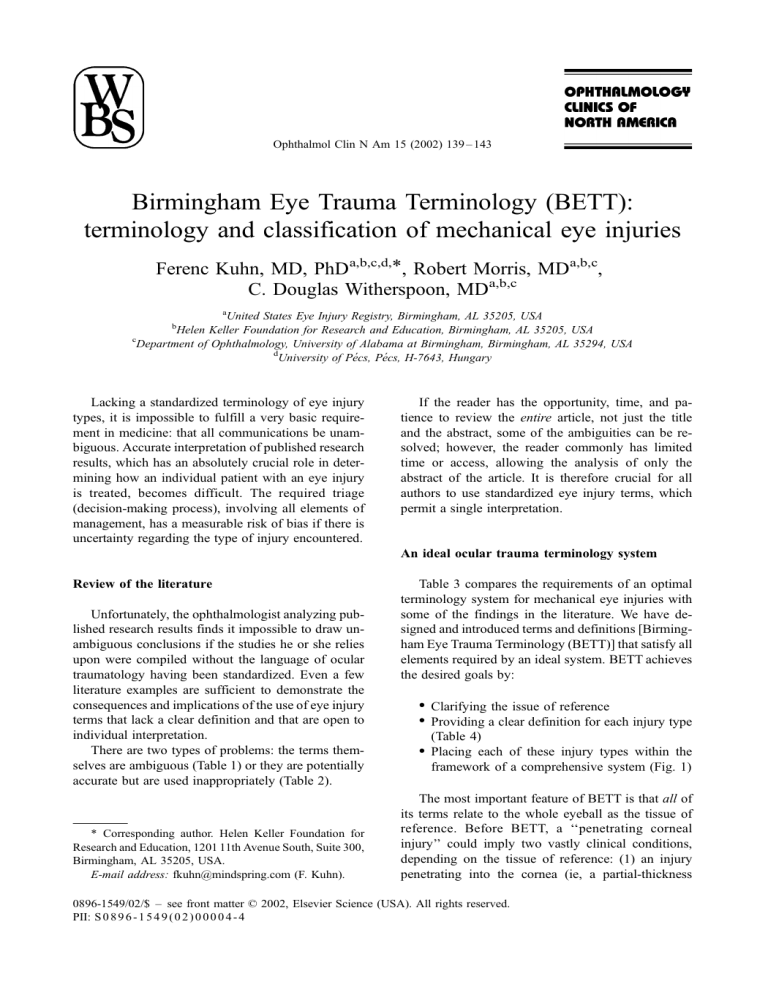

Ophthalmol Clin N Am 15 (2002) 139 – 143 Birmingham Eye Trauma Terminology (BETT): terminology and classification of mechanical eye injuries Ferenc Kuhn, MD, PhDa,b,c,d,*, Robert Morris, MDa,b,c, C. Douglas Witherspoon, MDa,b,c a United States Eye Injury Registry, Birmingham, AL 35205, USA Helen Keller Foundation for Research and Education, Birmingham, AL 35205, USA c Department of Ophthalmology, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, AL 35294, USA d University of Pécs, Pécs, H-7643, Hungary b Lacking a standardized terminology of eye injury types, it is impossible to fulfill a very basic requirement in medicine: that all communications be unambiguous. Accurate interpretation of published research results, which has an absolutely crucial role in determining how an individual patient with an eye injury is treated, becomes difficult. The required triage (decision-making process), involving all elements of management, has a measurable risk of bias if there is uncertainty regarding the type of injury encountered. If the reader has the opportunity, time, and patience to review the entire article, not just the title and the abstract, some of the ambiguities can be resolved; however, the reader commonly has limited time or access, allowing the analysis of only the abstract of the article. It is therefore crucial for all authors to use standardized eye injury terms, which permit a single interpretation. An ideal ocular trauma terminology system Review of the literature Unfortunately, the ophthalmologist analyzing published research results finds it impossible to draw unambiguous conclusions if the studies he or she relies upon were compiled without the language of ocular traumatology having been standardized. Even a few literature examples are sufficient to demonstrate the consequences and implications of the use of eye injury terms that lack a clear definition and that are open to individual interpretation. There are two types of problems: the terms themselves are ambiguous (Table 1) or they are potentially accurate but are used inappropriately (Table 2). * Corresponding author. Helen Keller Foundation for Research and Education, 1201 11th Avenue South, Suite 300, Birmingham, AL 35205, USA. E-mail address: [email protected] (F. Kuhn). Table 3 compares the requirements of an optimal terminology system for mechanical eye injuries with some of the findings in the literature. We have designed and introduced terms and definitions [Birmingham Eye Trauma Terminology (BETT)] that satisfy all elements required by an ideal system. BETT achieves the desired goals by: Clarifying the issue of reference Providing a clear definition for each injury type (Table 4) Placing each of these injury types within the framework of a comprehensive system (Fig. 1) The most important feature of BETT is that all of its terms relate to the whole eyeball as the tissue of reference. Before BETT, a ‘‘penetrating corneal injury’’ could imply two vastly clinical conditions, depending on the tissue of reference: (1) an injury penetrating into the cornea (ie, a partial-thickness 0896-1549/02/$ – see front matter D 2002, Elsevier Science (USA). All rights reserved. PII: S 0 8 9 6 - 1 5 4 9 ( 0 2 ) 0 0 0 0 4 - 4 140 Term [reference] Interpretation Clinical implication Resolution Blunt injury [2,3] The consequences of the trauma are blunt. The inflicting object is blunt. Closed globe injury (contusion) Open globe injury (rupture) Contusion rupture [4] ? (How can an injury be contusion and a rupture?) ? (What kind of injury is it? Contusion? Rupture?) We must eliminate blunt from our eye injury vocabulary and use either of the two accurate and unambiguous terms instead: contusion or rupture. This term should not be used. Blunt nonpenetrating globe injury [5] ? (Is there a sharp nonpenetrating injury? If so, what is it? If not, why use the term blunt at all?) ? (How can an injury be blunt and penetrating?) Blunt penetrating trauma [6] Sharp laceration [7] Blunt rupture [8] ? (Is there a laceration that is not sharp? If all lacerations are sharp, why the distinction? If not, how do they differ?) ? (Aren’t all ruptures blunt? If so, why the distinction? If not, how do they differ?) This term should not be used. ? (What kind of injury is it? Rupture? Penetrating?) This term should not be used. This term should not be used. This term should not be used. F. Kuhn et al / Ophthalmol Clin N Am 15 (2002) 139–143 Table 1 Literature review: ocular trauma terms difficult to interpret F. Kuhn et al / Ophthalmol Clin N Am 15 (2002) 139–143 141 Table 2 Literature review: ocular trauma terms used inappropriately Penetrating [9] Penetrating [10] Rupture [11,12] Likely interpretation by the reader Original interpretation in the article Resolution Injury with an entrance wound Injury with an entrance wound Any type of open globe injury Penetrating = perforating Open globe injury caused by impact of a blunt object Any type of open globe injury, including those caused by intraocular foreign bodies All penetrating injuries are open globe, but not all open globe injuries are penetrating. Penetrating and perforating injuries must be distinguished because they have vastly different management and prognostic implications. All ruptures are open globe, but not all open globe injuries are ruptures. Table 3 Ocular trauma terminology: an ideal system versus reality What should be the case What is the case Each eye injury term has a unique definition. It is exceptional that published studies provide definitions; nor are these definitions required by editors. The same term ( perforating) is used to describe two distinctly different clinical conditions: an injury with a single (entrance) wound [13] or one with both entrance and exit wounds [14]. The same type of injury (having an entrance and an exit wound) is referred to as double penetrating [15], double-perforating [16], and perforating [17]. No term can be used for describing two different injury types. No type of injury is described by different terms. Table 4 Terms and definitions in BETT a Term Definition/interpretation Explanation Eyewall Sclera and cornea Though technically the eyewall has three coats posterior to the limbus, for clinical and practical purposes, violation of only the most external structure is taken into consideration. Closed globe injury Open globe injury Contusion No full-thickness wound of eyewall Full-thickness wound of the eyewall No (full-thickness) wound Lamellar laceration Rupture Partial-thickness wound of the eyewall Full-thickness wound of the eyewall caused by a blunt object Laceration Full-thickness wound of the eyewall caused by a sharp object Entrance wound Penetrating injury Retained foreign object(s) Perforating injury a Entrance and exit wounds The injury results from direct energy delivery by the object (eg, choroidal rupture) or from the changes in the shape of the globe (eg, angle recession). The wound of the eyewall is not ‘‘through’’ but ‘‘into.’’ Because the eye is filled with incompressible liquid, the impact results in momentary increase of the intraoccular pressure. The eyewall yields at its weakest point (at the impact site or elsewhere; eg, an old cataract wound dehisces even though the impact occurred elsewhere; The actual wound is produced by an inside-out mechanism. The wound occurs at the impact site by an outside-in mechanism. If more than one wound is present, each must have been caused by a different agent. Technically this a penetrating injury but grouped separately because of different clinical implications. Both wounds are caused by the same agent. Some injuries remain difficult to classify (an intravitreal BB pellet) whereas technically an intraocular foreign body (IOFB) injury is a blunt object that requires great force to enter the eye, involving an element of rupture. In such situations, the ophthalmologist should describe the injury as ‘‘mixed’’ (ie, rupture with an IOFB) or select the most serious type of the mechanisms involved. 142 F. Kuhn et al / Ophthalmol Clin N Am 15 (2002) 139–143 Fig. 1. BETT. The thick boxes contain the diagnoses used in clinical practice. corneal wound: a closed globe injury) or (2) an injury penetrating into the globe (ie, a full-thickness corneal wound: an open globe injury). In BETT, a penetrating injury is unambiguously an open globe injury with a single (entrance) wound; corneal simply refers to wound location. BETT [1] has been endorsed by several organizations (eg, American Academy of Ophthalmology; International Society of Ocular Trauma; Retina Society; United States Eye Injury Registry and its 32 international affiliates; Vitreous Society; and the World Eye Injury Registry) and is mandatory for all submission by several journals (eg, Graefe’s Archives for Clinical and Experimental Ophthalmology; Journal of Eye Trauma; Klinische Monatsblätter für Augenheilkunde; and Ophthalmology). With BETT becoming the language of everyday clinical practice, we can reasonably hope to eliminate all ambiguities in our communications in the field of ocular traumatology. References [1] Kuhn F, Morris R, Witherspoon CD, Heimann K, Jeffers J, Treister G. A standardized classification of ocular trauma terminology. Ophthalmology 1996;103:240 – 3. [2] Joseph E, Zak R, Smith S, Best W, Gamelli R, Dries D. Predictors of blinding or serious eye injury in blunt trauma. J Eye Trauma 1992;33:19 – 24. [3] Russell S, Olsen K, Folk J. Predictors of scleral rupture and the role of vitrectomy in severe blunt ocular trauma. Am J Ophthalmol 1988;105:253 – 7. [4] Eide N, Syrdalen P. Contusion rupture of the globe. Acta Ophthalmol 1987;182S:169 – 71. [5] Liggett PE, Gauderman WJ, Moreira CM, Barlow W, Green RL, Ryan SJ. Pars plana vitrectomy for acute retinal detachment in penetrating ocular injuries. Arch Ophthalmol 1990;108:1724 – 8. [6] Meredith TA, Gordon PA. Pars plana vitrectomy for severe penetrating injury with posterior segment involvement. Am J Ophthalmol 1987;103:549 – 54. [7] de Juan E, Sternberg P Jr, Michels RG. Penetrating ocular injuries. Ophthalmology 1983;90:1318 – 22. [8] Kylstra JA, Lamkin JC, Runyan DK. Clinical predictors of scleral rupture after blunt ocular trauma. Am J Ophthalmol 1993;115:530 – 5. [9] de Juan E, Sternberg P Jr, Michels R, Auer C. Evaluation of vitrectomy in penetrating ocular trauma. A casecontrol study. Arch Ophthalmol 1984;102:1160 – 3. [10] Hassett P, Kelleher C. The epidemiology of occupational penetrating eye injuries in Ireland. Occup Med 1994;44:209 – 11. [11] Pump-Schmidt C, Behrens-Baumann W. Changes in the epidemiology of ruptured globe eye injuries due to societal changes. Ophthalmologica 1999;213:380 – 6. [12] Rudd J, Jaeger E, Freitag S, Jeffers J. Traumatically F. Kuhn et al / Ophthalmol Clin N Am 15 (2002) 139–143 ruptured globes in children. J Ped Ophthalmol Strab 1994;31:307 – 311v. [13] Punnonen E, Laatikainen L. Prognosis of perforating eye injuries with intraocular foreign bodies. Acta Ophthalmol 1989;66:483 – 91. [14] Ramsay RC, Knobloch WH. Ocular perforation following retrobulbar anesthesia for retinal detachment surgery. Am J Ophthalmol 1978;86:61 – 4. [15] Ramsay RC, Cantrill HL, Knobloch WH. Vitrectomy 143 for double penetrating ocular injuries. Am J Ophthalmol 1985;100:586 – 9. [16] Topping TM, Abrams GW, Machemer R. Experimental double-perforating injury of the posterior segment in rabbit eyes. Arch Ophthalmol 1979;97:735 – 42. [17] Hutton -WL, Fuller DG. Factors influencing final visual results in severely injured eyes. Am J Ophthalmol 1984;97:715 – 22.