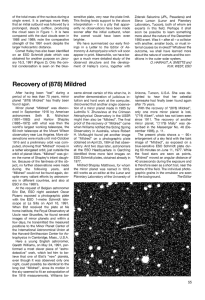

JHA, xxii (1991) THE EARLIEST NATIONAL OBSERVATORIES IN LATIN AMERICA PHILIP C. KEENAN, The Ohio State University Introduction This paper gives a very brief summary of the founding of the first five national observatories that appear to have actually undertaken astronomical research in Latin America. The difficulties involved in launching a national observatory, serious enough in the most advanced European countries, were much worse in colonial Iberoamerica. To the notorious economic and scientific stagnation of Spain and Portugal in the seventeenth century was added the deliberate policy of the home governments to discourage independent thought in their colonies. A partial exception was in Mexico City, which was more cosmopolitan than most of the more isolated colonial capitals. From the arrival of Enrico Martinez (Heinrich Martin) in 1589 there were usually some men with astronomical training active in Mexico, but no one seems seriously to have considered setting up a national observatory there during the three centuries of Spanish rule. Nueva Granada It was largely a matter of chance that it was in the Viceroyalty of Nueva Granada, which included the present countries of Colombia and Venezuela in South America, that the first Latin-American national observatory was erected. When in the middle of the eighteenth century Charles III of Spain was trying to revive scientific activity in his domain, he sent several botanical and geographical exploring expeditions to the New World. A young physician with broad scientific interests, Jose Celestine Mutis, was invited to accompany the incoming Viceroy of Nueva Granada, Mascia de la Zerda. They arrived in the capital, Santa Fe de Bogata, in 1761. Mutis was soon lecturing at the Colegio del Rosario. In his astronomy courses he naturally taught the Copernican theory, since it was nearly a century after Newton's work. The Dominican authorities of the Universidad Thomistica there, however, denounced Mutis to the Inquisition in 1771. Fortunately, the power of the Holy Office was weakening by then, and Mutis's reputation was so strong that the charges were dismissed. For most of his life in Nueva Granada Mutis was preoccupied with organizing and leading the great Botanical Expedition, which was concerned with mapping the country as well as exploring its natural resources, particularly the cinchona tree as a source of quinine. In all of this work he was strongly supported by the viceroys. At the end of the century they turned their attention to the erection of a national observatory, which would be located in the garden of the Botanical Expedition. I 0021-8286/91/2201-0021 $2.50 © 1991 Science History Publications Ltd 22 Philip C. Keenan FIG. l. The Bogota Observatory, from photograph by R. F. Wing. National Observatories in Latin America 23 Construction was authorized by the Minister Marques de Sonora, and the first stone was laid on 24 May 1802. The Observatorio Astronomico de Bogota was completed on 20 August 1803. While the word "National" does not appear in its title, there is no doubt that in intent and in fact it was the National Observatory, first of the Viceroyalty, and later of the Republic of Colombia. It was built near the centre of the old city of Bogota, which lies in a broad valley, surrounded by low mountains, at an altitude of 2630 metres, about 4to north of the equator. From Figure 1 it can be seen that the building was one of the old European-style observing towers.' By 1805 Mutis was seventy-five years old, and recommended his former student, Francisco Jose de Caldas, as the first Director of the Observatory. Born in 1771, on the western slope of the country, in Popayan, Caldas became adept in meteorology, botany and astronomy. He made many of his own instruments, and among other devices invented the hydrometer, a simple form of barometer that measured the air pressure by the temperature at which water boiled. He, as well as Mutis, met and aided Humboldt and Bonpland in their famous exploration across Neuva Granada to the Andes in 1800-3. 3 For Caldas, as for Mutis, the observatory was an integral part of the Botanical Expedition, which was not limited to studying plants but was concerned also with mapping the country and providing useful meteorological data. Thus it is not surprising that of Caldas's forty-three publications only six can be considered astronomical, and they either are almanacs or refer to the position of the Observatory. Also, Caldas's astronomical work was seriously limited by lack of telescopes. Three boxes of instruments, including a transit which had been ordered by the Marques de Sonora with the help of the King, were lost in shipment from Cadiz. Caldas made the observatory a centre for scientific gatherings, but had only a few years in which to work. Caught up in the revolt which began in July 1810, and which eventually led to independence for the country, he was later captured by the Spanish army under General Morillo, and condemned to death. He and his friends asked that he be spared to continue his scientific work, but according to legend the Spanish commander said "Espana no necesita de sabios", and Calda was executed by a firing squad in the Plaza de San Francisco, a few blocks from the observatory, on 29 October 1816. Although Colombia was finally liberated by Bolivar a few years later, there was little time or money for astronomy in the impoverished country, torn by political quarrels. Through all its ups and downs, however, the old building remained officially El Observatorio de Bogota until its astronomical functions were formally transferred to the University of Bogota on the outskirts of the city in 1936.4 Throughout its history the old observatory was always handicapped by the lack of a large telescope, and only a few scattered astronomical publications ever appeared. At times the vicissitudes of war and politics made its history more romantic than astronomical, but its purpose was never completely forgotten.> 24 Philip C. Keenan FIG. 2. The Imperial Observatory of Rio de Janeiro in its original location on the Morro do Castello at the Military and Naval School, from Annales de I'Observatoire Imperiale de Rio de Janeiro, i (1882), frontispiece. Rio de Janeiro In the eighteenth century the Portuguese government had done little to encourage science in Brazil, where no printing press was allowed to operate until 1808. That was the year that Jose VI moved the Portuguese court to Brazil in order to escape from the armies of Napoleon. Then, and especially after the peaceful transition to independence under Pedro I in 1822, there was a dramatic rise in scientific activity. There had been desultory astronomical observations made at the Military School early in the century," but it was in 1827 that the authorization for a national observatory was issued by the Imperial Government. A commission appointed in 1825 drew up elaborate plans for an observatory that would aid in mapping the country and provide a base for courses in practical astronomy for students in the Military and Naval Academies. Presumably from lack of funds, nothing materialized for some seventeen years. In 1845 the Minister of War, Jeronimo Francisco Coelho issued an order for an inventory to be made of the astronomical instruments lying around the Military School. Professor Soulier de Sauve was named Director of the Observatorio Astronomico, and after some argument about the site, the hill Morro do Castelo on the grounds of the Escole Militar was chosen (Figure 2). National Observatories in Latin America 25 FIG. 3. The two little sheds of the U.S. Naval Expedition on the north slope of the hill of Santa Lucia, Santiago. From James M. Gilliss, The U.S. naval astronomical expedition to the southern hemisphere during the years 1849-50 (Washington, 1856), i, II. Soulier de Sauve died in 1850, before the Observatory was completed. The next Director, Antonio Manuel de Melo, published some ephemerides and organized parties to observe the solar eclipses of 1858 and 1865. The largest telescope mentioned in earliest accounts of the Observatory was an 8.5-cm (3.3-inch) refractor of Dollond.? Partly because of the economic strain of the war with Paraguay, little was done at the Observatory in the 1860s. The Emperor, Dom Pedro II, however, had an interest in astronomy and had a working knowledge of telescopes and astronomical clocks." As soon as the war was over (1870) he reorganized the Observatory and brought in the capable French astronomer Emanuel Liais, as Director. Since then the Observatory has remained active. In 1909 its name was changed to Observatorio Nacional, and in 1922 it was moved from the Escole Militar to a better site on the Morro de Sao Januario. Santiago Dreams of an observatory in Chile go back to the War of Independence. When the hero of the war, Bernardo O'Higgins, lay dying in exile in Peru in 1842 he wrote to his friends expressing the hope that part of his estate could be used to establish an astronomical observatory on the hill of Santa Lucia near the centre 26 Philip C. Keenan of Santiago." This did not happen, and it was by coincidence that when Lt James Gilliss led a U.S. Naval Observatory expedition to Chile in 1849 he set up his little observatory on that same hill.!? The purpose of the expedition was to obtain an improved solar parallax by simultaneous observations of Venus and Mars from the northern and southern hemispheres. President Bulnes of Chile, his successor Manuel Montt, and the University Delegate, Ignacio Domeyko, enthusiastically welcomed the expedition, and it was soon agreed that the observatory should be transferred to the Government of Chile on the departure of the United States Observers. Lt Gilliss wanted it to be a gift to Chile, but it took so long to get the authorization approved by the U.S. Congress that he was obliged to leave before it came through, and the Chilean Government actually bought the instruments and prefabricated sheds at cost, 7823 pesos. Figure 3 shows the two little buildings reproduced from the original sketch by Lt Gilliss.!? Since Gilliss had been in charge of the construction of the original U.S. Naval Observatory in Washington, he can be said to have founded two national observatories some 5000 miles apart! EI Observatorio Nacional de Santiago officially opened on the day of the transfer of title, 17 August 1852.11 The first Director was Karl Wilhelm Moesta from Zierenberg, Germany, who had been in Chile with the Topographical Survey of that country for two years. The two original instruments were a 16.5em (6.5-inch) refractor with a lens ground by Henry Fitz of New York, and a meridian circle from Pistor & Martins. For several years, until the death of Gilliss in 1865, the Observatory in Santiago and the U.S. Naval Observatory cooperated on the solar parallax program. Newcomb included the Chilean observatories in his reduction of all available data relating to the solar parallax, leading to a distance to the Sun of 92,350,000 miles, only slightly below the best present estimates.'! It was soon necessary to replace the wooden buildings, and since both Gilliss and Moesta had noticed that heating of the rock on which the pier rested caused a periodic shift in the azimuth of the transit instrument, a new site was desirable. By 1862 the observatory was moved to new buildings on the grounds of the Quinta Normal de Agricultura, unfortunately in the lowest and foggiest part of the city. It was not until the present century that the observatory moved to higher ground, at Lo Espejo south of the city. Then, between 1956and 1963, the present site on the Cerro Calan, where the city rises to the foothills of the Andes, was developed. Cordoba Across the Andes in Argentina there was little opportunity for scientific activity until the overthrow of the dictator Rosas in 1852 and the arrival of that human dynamo, Domingo Faustino Sarmiento. In 1865-66 Sarmiento served as Argentine Minister to the United States, and here he became friendly with Benjamin Gould, the former Director at Albany Observatory. Given Sarmiento's passionate interest in the development of education and science in his National Observatories in Latin America FIG. 27 4. The first Mexican National Observatory on the roof of the Castle of Chapultepec. The small dome on the left is that of the Observatory. From coloured print provided by Eugenio Mendoza. country, Gould had little difficulty in persuading him that Argentina should have a national observatory to survey the southern sky." Sarmiento became President of the Argentine Republic in 1867, and even while putting down insurrections and struggling to establish a better school system in the country, he forced an appropriation for an observatory through the National Congress. Gould was appointed Director, and immediately built the Observatory and began observations. Although it was located at Cordoba, near the venerable University of Cordoba, Sarmiento made it clear that it was a truly national observatory. When he travelled to Cordoba to dedicate it on 24 October 1871, he declared (in Sersic's translation), "It's said that it is too early or superfluous to have an observatory in young countries with a budget in the red. Well, I say we have to resign the rank of nation, and the title of civilized people, unless we take our share in the progress and the movement of the natural sciences."14 The main telescope was a Clark reflector of 28-cm (II-inch) aperture. Gould returned to the United States in 1885 after completing several catalogues. The work on the Cordoba Durchmusterung, containing more than 570,000 stars, however, was continued by John Thome and his wife. This catalogue and atlas formed the most important contribution to astronomy made by any Latin American observatory in the nineteenth century.P 28 Philip C. Keenan Mexico City If we look to the north, at Mexico, we should not be surprised that the bloody Civil Wars preceding and following independence in 1821 discouraged the building of observatories. Yet as early as 1822, Simon Tadeo had suggested the establishment of an observatory on the roof of the Castle of Chapultepec." After the suppression of the old University of Mexico in 1833, astronomy was taught in the Colegia de Mineria, which after 1842 maintained a small observatory (Figure 4) on the Castle until it was destroyed in the siege of the Castle by the U.S. Army in 1848. In the following years when Mexico was trying to recover from that war the most active astronomer in the country was the engineer-scientist Francisco Diaz Covarrubias. In January 1863 when President Benito Juarez was trying to find means of resisting the invading French army, Diaz Covarrubias began work in what was intended to be a national observatory on the Castle, using an Ertel meridian circle. By May, however, the government was forced to abandon the city, and in 1864 Maximilian was made Emperor by the French. Maximilian evidently had some interest in astronomy, for he invited Diaz Covarrubias to resume his observations. The latter, however, refused to have anything to do with the French administration. Then Maximilian invited Matthew Maury to come to Mexico as Director of the National Observatory. Maury, the first Director of the U.S. Naval Observatory, had joined the Confederate Government at the outbreak of the Civil War in the United States, and at the end of the war had fled to England. He had become acquainted with Maximilian in Europe, and now accepted his invitation. Maury, however, was much more interested in a plan to resettle former Confederates in Mexico than in doing anything with the few astronomical instruments available. Also, he soon realized that the Empire was doomed, and returned to England in January 1866 - before the overthrow and execution of Maximilian. I? With Juarez in power again Diaz Covarrubias returned to Mexico City as an official in the office of the Secretary of Development. He set up a small observatory in the National Palace in the centre of the city, and made a few observations there until he took some of the instruments with him when he left in 1874 as leader of the Mexican expedition to Japan to observe the transit of Venus in December of that year." When Portfirio Diaz gained the Presidency by a military coup in 1876, he at first appointed some good men to his cabinet. Vicente Riva Palacio, Secretary of Development (Fomento), was keenly interested in science. He called in a young engineer, D. Angel Anguiano, who had been Inspector General of Roads, but had already demonstrated ability in astronomy. Riva Palacio is reported to have said to him: "We are going to have an astronomical observatory as soon as possible, and you are going to be the Director."19 Anguiano proved to be the right man for the task, and by 1878 the new observatory, back on the roof of Chapultepec, was in operation - and El Observatorio Astron6mico Nacional has continued as a centre of research since, though not in the same place. In 1883 a new observatory building was National Observatories in Latin America 29 erected at Tacubaya, a more suitable part of the city, with a 32-cm (12.6-inch) telescope as the principal instrument. Here the observatory continued to operate until it was moved out of the city to Tonantzintla, in the Valley of Cholula, in 1951. This, and the newer observatory at San Pedro Martin in Baja, California, are administered by the Instituto de Astronomia on the huge campus of the Universidad Nacional Autonomia at the southern edge of Mexico City. There, in 1978, the hundredth anniversary of the official founding of the observatory was celebrated." Summary These five national observatories share one common feature: each came into existence only when one or more officials of the government showed enthusiasm and determination that it should be built. I had expected to find that foreign scientific expeditions would have played a major role, but this was true only in Chile. Although practical needs for geographical positions and almanacs were involved in the founding of each observatory, it is striking that the last four were created with the primary aim of contributing research in pure astronomy. Of course, these hopes were not fulfilled at all times. With changing governments and staffs most of the observatories went through periods of stagnation when only routine observations were expected or made. At least four of the five, however, have emerged as active centres of research today. Acknowledgements I am indebted to Brenda Corbin and Steven J. Dick (Washington) for details of the Gilliss expedition. Dr Dick has also made very helpful editorial comments. I thank the staff of the Instituto Astron6mico, particularly Paris Pismis, Eugenio Mendoza, and Marco Moreno C. for information and texts relating to astronomy in Mexico. REFERENCES I. The primary source for the history of the observatory, from the arrival of Mutis to 1950, is Alfredo D. Bateman, El Observatorio Astronomico de Bogota: Monografia historica con ocasion del 150. anniversario de su fundacion, 1803- agosto 20 -1953 (Bogota, 1954). The Botanical Expedition has been described by Florentino Vezga, La Expedicion Botanica (Bogota, 1936). 2. The Observatory still stands (as of last report) next to the Presidential Palace, in one corner of the large plaza which extends to the National Capital. Although surrounded by the remains of the garden of the Botanical Expedition, it is now difficult to visit or photograph. With the increase of terrorism in recent years the entire square was surrounded by a high fence topped with barbed wire, and is patrolled by members of the Presidential Guard. 3. In addition to the book of Bateman, there is a biographical monograph by Lino de Pombo, Luis Marra Murillo, and Alfredo D. Bateman, Francisco Jose de Ca/das, published as a Supplement to La Revista de la Academia Colombiana de Ciencias Exactas, Fisicas y Naturales (Bogota, 1958). 4. The astronomical library, however, including the books that belonged to Caldas, were still housed in the old tower when I visited it around 1970. 30 Philip C. Keenan 5. Bogota was probably the only observatory to have two of its Directors (Caldas and Burla) killed by Spanish forces. It must also have been the only one to have been used as a prison for a deposed President of the Republic - General Mosquera, during most of 1867. 6. These seem to have been mostly geodetic observations. N. E. Mailly, Tableau de l'astronomie dans l'hemisphere austral et dans l'Inde (Brussels, 1872), 222, mentions an observatory in Rio de Janeiro as early as 1780, but Morais (op. cit. (ref. 7), 120) thinks that this refers to surveys of the boundaries of Rio made by Sanchez Dorta and Oliveira Barbosa in 1781. 7. The story of the founding of the Observatorio Astronomico de Rio de Janeiro has been summarized well by A. de Morais in vol. i, ch. 2 of Fernando de Azevedo, Las ciencias no Brazil (Rio de Janeiro, n.d.) and in Henrique Morize, Observatorio Astronomico, urn secula de historia 1827-1927) (Rio de Janeiro, 1987). 8. When the Emperor came to the United States in 1876 in connection with the Philadelphia Exposition, he requested a visit to the U.S. Naval Observatory. Simon Newcomb, then in charge of the transit circle, was in the group appointed to receive him. In his Reminiscences of an astronomer (Boston, 1903), 116-20, Newcomb describes his surprise when Dom Pedro cut the ceremonies short in order to make a thorough tour of the Observatory and take a view of the Moon with the 26-inch reflector. The Emperor examined particularly the mounting of the clocks. 9. Jaime Eyzaguirre, O'Higgins (Santiago, 1946),463-4. 10. The expedition is described in the detailed report, James M. Gilliss, The U.S. naval astronomical expedition to the southern hemisphere during the years 1849-50 (5 vols, Washington, 1856). II. The history of the Observatory has been related by P. C. Keenan, S. Pinto, and H. Alvarez, The Chilean National Astronomical Observatory (1852-1965) (Santiago, 1985). The text is in both English and Spanish. Many of the earlier documents and reports of the Observatory were published in Annales de la Universidad de Chile from 1852 to 1965. 12. S. Newcomb, Appendix II to the Astronomical and meteorological observations made at the United States Naval Observatory during the year 1865 (Washington, 1867). 13. Some account of the discussion between Sarmiento and Gould is given by G. C. Comstock, "Benjamin Apthorp Gould", Biographical memoirs of the National Academy of Sciences, xvii (1922), 155-80. 14. A description of the founding and work of the Observatory is given in the centennial publication, Observatorio Astronomico de Cordoba. 1871- 24 de Octubre -1971. Gould's own description of the early days of the Observatory was published in American journal of science, 3rd series, i (1871), 153--6. 15. The work of the Cordoba Observatory between 1909 and 1936 has been described by John E. Hodge, "Charles Dillon Perrine and the transformation of the Argentine National Observatory", Journalfor the history of astronomy, viii (1977), 12-25. 16. Ortiz de Ayala and Simon Tadeo, Resumen de la Estadistica del Impero Mexicano, 1882 (Mexico, 1968).The early efforts to establish an observatory in Mexico City are described by Marco A. Moreno C., "Algunos sucesos que dieron origen a la fundacion definitiva del Observatorio Astronomico Nacional de Mexico en 1878", Quipu, iii (1986), 299-309. There is a brief account of astronomy in Mexico in Eli de Gortari, La ciencia en la historia de Mexico (Mexico City, 1980), 178. 17. The Maximilian-Maury interlude is treated briefly in the several biographies of each. Cf Frances L. Williams, Mathew Fontaine Maury. scientist of the sea (New Brunswick, 1963). 18. There is an interesting description of the expedition to Japan in Luis de Leon, Los progresos de la astronomia en Mexico desde 1810 a 1910 (Mexico City, 1911). 19. Ibid., 17-19. 20. A special issue of Ciencia y desarollo (May-June, 1978) was devoted to the anniversary. An address by Paris Pismis, "EI Observatorio Astronomico Nacional: Su huella en el primer siglo de vida", appeared in Revista de la Universidad de Mexico, August 1978.