- Ninguna Categoria

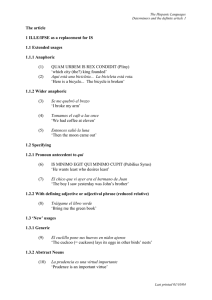

(Inter)Subjectivity, Subjectification, and Grammaticalization

Anuncio