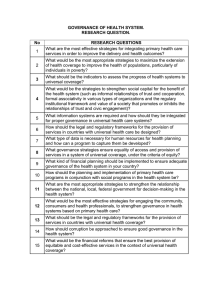

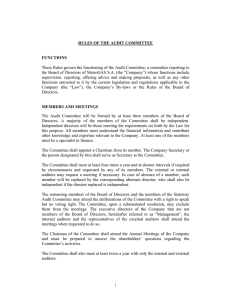

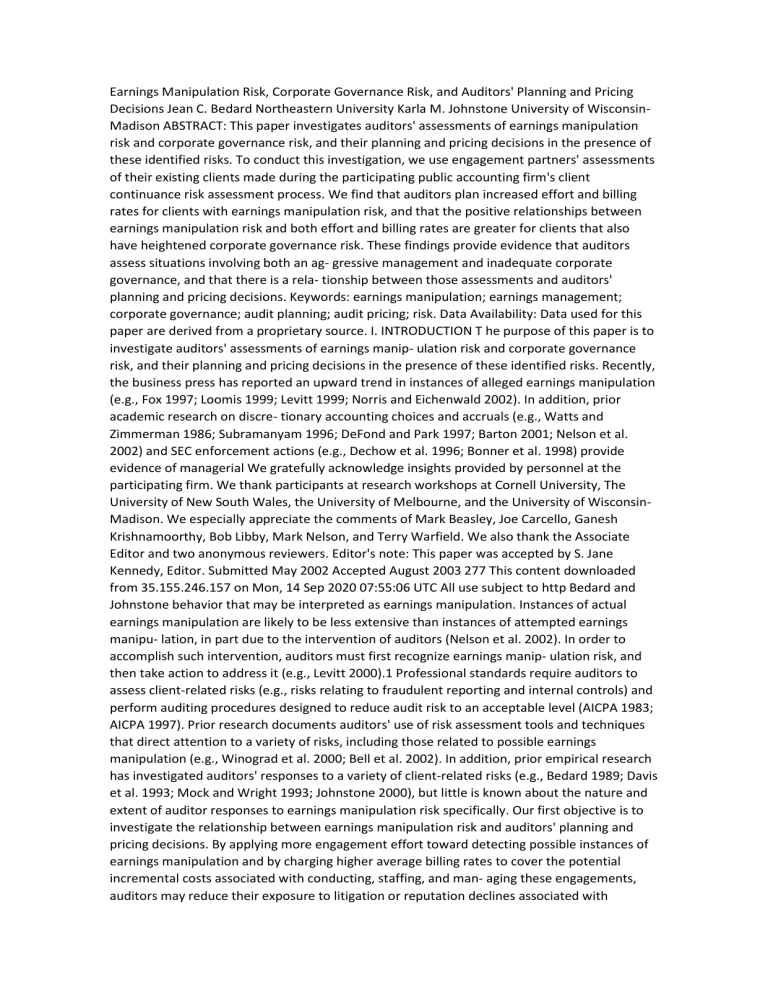

Earnings Manipulation Risk, Corporate Governance Risk, and Auditors' Planning and Pricing Decisions Jean C. Bedard Northeastern University Karla M. Johnstone University of WisconsinMadison ABSTRACT: This paper investigates auditors' assessments of earnings manipulation risk and corporate governance risk, and their planning and pricing decisions in the presence of these identified risks. To conduct this investigation, we use engagement partners' assessments of their existing clients made during the participating public accounting firm's client continuance risk assessment process. We find that auditors plan increased effort and billing rates for clients with earnings manipulation risk, and that the positive relationships between earnings manipulation risk and both effort and billing rates are greater for clients that also have heightened corporate governance risk. These findings provide evidence that auditors assess situations involving both an ag- gressive management and inadequate corporate governance, and that there is a rela- tionship between those assessments and auditors' planning and pricing decisions. Keywords: earnings manipulation; earnings management; corporate governance; audit planning; audit pricing; risk. Data Availability: Data used for this paper are derived from a proprietary source. I. INTRODUCTION T he purpose of this paper is to investigate auditors' assessments of earnings manip- ulation risk and corporate governance risk, and their planning and pricing decisions in the presence of these identified risks. Recently, the business press has reported an upward trend in instances of alleged earnings manipulation (e.g., Fox 1997; Loomis 1999; Levitt 1999; Norris and Eichenwald 2002). In addition, prior academic research on discre- tionary accounting choices and accruals (e.g., Watts and Zimmerman 1986; Subramanyam 1996; DeFond and Park 1997; Barton 2001; Nelson et al. 2002) and SEC enforcement actions (e.g., Dechow et al. 1996; Bonner et al. 1998) provide evidence of managerial We gratefully acknowledge insights provided by personnel at the participating firm. We thank participants at research workshops at Cornell University, The University of New South Wales, the University of Melbourne, and the University of WisconsinMadison. We especially appreciate the comments of Mark Beasley, Joe Carcello, Ganesh Krishnamoorthy, Bob Libby, Mark Nelson, and Terry Warfield. We also thank the Associate Editor and two anonymous reviewers. Editor's note: This paper was accepted by S. Jane Kennedy, Editor. Submitted May 2002 Accepted August 2003 277 This content downloaded from 35.155.246.157 on Mon, 14 Sep 2020 07:55:06 UTC All use subject to http Bedard and Johnstone behavior that may be interpreted as earnings manipulation. Instances of actual earnings manipulation are likely to be less extensive than instances of attempted earnings manipu- lation, in part due to the intervention of auditors (Nelson et al. 2002). In order to accomplish such intervention, auditors must first recognize earnings manip- ulation risk, and then take action to address it (e.g., Levitt 2000).1 Professional standards require auditors to assess client-related risks (e.g., risks relating to fraudulent reporting and internal controls) and perform auditing procedures designed to reduce audit risk to an acceptable level (AICPA 1983; AICPA 1997). Prior research documents auditors' use of risk assessment tools and techniques that direct attention to a variety of risks, including those related to possible earnings manipulation (e.g., Winograd et al. 2000; Bell et al. 2002). In addition, prior empirical research has investigated auditors' responses to a variety of client-related risks (e.g., Bedard 1989; Davis et al. 1993; Mock and Wright 1993; Johnstone 2000), but little is known about the nature and extent of auditor responses to earnings manipulation risk specifically. Our first objective is to investigate the relationship between earnings manipulation risk and auditors' planning and pricing decisions. By applying more engagement effort toward detecting possible instances of earnings manipulation and by charging higher average billing rates to cover the potential incremental costs associated with conducting, staffing, and man- aging these engagements, auditors may reduce their exposure to litigation or reputation declines associated with earnings manipulation risk (e.g., St. Pierre and Anderson 1984; Palmrose 1987; Becker et al. 1998; Heninger 2001). For example, audit firms may apply more effort when assessing the reasonableness of accounting estimates for clients with heightened earnings manipulation risk (e.g., AICPA 1988). Similarly, they may use en- gagement team personnel with more overall or industry-specific experience, as the greater knowledge possessed by these auditors enables better performance in detecting misstate- ments in complex client situations (e.g., Bedard and Biggs 1991; Johnson et al. 1991; Solomon et al. 1999; Johnstone and Bedard 2003). Because the use of such personnel raises the average audit cost per hour of work performed, audit firms may charge higher billing rates on engagements with higher earnings manipulation risk. Further, audit firms may charge a higher hourly billing rate to clients with higher earnings manipulation risk as a premium to compensate them for costs related to potential future litigation. Our second objective is to investigate the relationship between corporate governance risk and auditors' planning and pricing decisions.2 While intervention by auditors may deter instances of earnings manipulation, regulatory and professional standards and the business press have increasingly emphasized the need for effective corporate governance to help mitigate financial reporting risks, including earnings manipulation risk (e.g., Blue Ribbon Committee 1999). Boards of directors and audit committees should play an important role in controlling the quality of financial reporting (e.g., DeFond and Jiambalvo 1993; Public Oversight Board 1993, 1994, 2000; Dechow et al. 1996; Cohen et al. 2002). If external This paper studies the risk of earnings manipulation, which we define as management's intervention in the external financial reporting process using reporting practices with the intent of biasing users' views of the company. While the term "earnings management" is also used to describe this behavior (e.g., Nelson et al. 2002), our variable encompasses the potential for both GAAP and non-GAAP interventions in the financial reporting process. As such, we adopt the term earnings manipulation, which is also used by Dechow et al. (1996) to describe a similar construct. See the "Method" section for details of variable construction. 2 Corporate governance includes actions taken by boards of directors and audit committees to ensure the reliability of financial reporting (Public Oversight Board 1993). We measure corporate governance risk as the presence of risk factors (defined in the "Method" section) indicating that boards of directors or audit committees may be ineffective in performing these actions. We acknowledge that corporate governance also includes control by other parties within the financial reporting process (e.g., internal audit and shareholders). The Accounting Review, April 2004 278 This content downloaded from 35.155.246.157 on Mon, 14 Sep 2020 07:55:06 UTC All use subject to http Earnings Manipulation, Corporate Governance, and Auditors' Decisions auditors perceive that they cannot rely on corporate governance mechanisms, such as boards of directors and audit committees, to help control the quality of financial reporting, they may increase audit effort (e.g., Cohen and Hanno 2000) and charge higher billing rates as a risk premium to cover potential incremental costs for clients with heightened corporate governance risk. In addition to investigating the relationships between perceived earnings manipulation risk and corporate governance risk and audit planning and pricing decisions, we also ex- amine potential interactive relationships between these risks and auditors' decisions. The simultaneous presence of both types of risks implies both an aggressive management and inadequate corporate governance. This combination suggests particularly heightened risk, and implies a positive interaction of earnings manipulation risk and corporate governance risk in models of auditors' planning and pricing decisions. To address these research issues, we use engagement partners' assessments of their existing clients made during the participating public accounting firm's 2000-2001 client continuance risk assessment process.3 Following removal of privately held clients and those with missing data, our final sample contains over 1,000 engagement risk assessments, to- gether with auditors' effort and billing rate decisions made in conjunction with those risks. Using this sample, we estimate OLS regression models of the natural log of planned audit hours and planned average hourly billing rates on earnings manipulation risk, corporate governance risk, and their interaction. Our models control for other factors that prior re- search has shown to explain variance in audit planning and pricing, such as client size, financial condition, and industry membership. This paper, and the data on which it is based, provide the ability to extend the literatures on earnings manipulation and corporate governance in two main ways. First, the data we use to conduct our investigation provide a unique opportunity to investigate the risks as- sociated with earnings manipulation and corporate governance, topics of considerable con- temporary importance, across a large portfolio of publicly traded clients. For example, the paper provides evidence about the nature and relative frequency of earnings manipulation risk and corporate governance risk factors as measured by the participating firm, using auditors' actual assessments of these risks that are informed by their personal knowledge of the client's personnel and its business. As such, this paper answers calls for research providing evidence on the existence of behavior consistent with earnings management, particularly across a broad array of clients (Healy and Wahlen 1999). Further, the descriptive data and the inferences that can be drawn from coefficients in the hours and billing rate models provide unique evidence about these risks and related audit planning and pricing decisions.4 Second, because the data include components of planned fees (i.e., information on both effort and billing rate), we are able to investigate the nature of the relationship between earnings manipulation risk and corporate governance risk assessments and planning and pricing decisions, determining whether there is a relationship between the risks and changes in planned hours (which has implications for audit effectiveness), the planned billing rate per hour (which has implications for the audit firm's ability to cover costs), or 3 Client continuance risk assessments occur each year when audit firms decide whether to continue providing audit services to their clients. 4 Audit planning and pricing decisions are made by senior members of engagement teams, and these individuals also participate in risk assessment. This implies some level of endogeneity when modeling planning or pricing as a function of risk assessments, a common feature of studies in this area. Further, we note that auditors' risk assessments may not fully or consistently reflect the characteristics of their clients, due to information asymmetry between client and auditor, or to decision biases. Essentially, we study whether auditors' planning and pricing decisions vary systematically with the risks that they recognize during risk assessment. The Accounting Review, April 2004 279 This content downloaded from 35.155.246.157 on Mon, 14 Sep 2020 07:55:06 UTC All use subject to http Bedard and Johnstone both. Thus, we are able to disentangle the relationships between risk and planning and pricing decisions that are confounded in examinations of total audit fees. Descriptive results show that relatively few of the firm's clients were assessed as having high levels of earnings manipulation risk or corporate governance risk. For example, the distribution of earnings manipulation risk factors shows that 81.0 percent of clients have zero earnings manipulation risk factors, 15.1 percent have one, 2.5 percent have two, 0.9 percent have three, and 0.5 percent have four or more risk factors. The distribution of corporate governance risk factors shows that 83.8 percent of clients have zero corporate governance risk factors, 10.8 percent have one, 3.0 percent have two, 1.5 percent have three, and 0.9 percent have four or more risk factors. Results of the regression models indicate that heightened earnings manipulation risk, and the interactive effect of earnings manipulation risk and corporate governance risk, are both associated with increases in planned audit hours and planned billing rates. However, corporate governance risk alone is not associated with differences in planned hours or billing rates. These results reveal that only in the presence of factors suggesting management's aggressive financial reporting behavior is corporate governance risk associated with increases in audit hours and billing rates. Model coefficients imply an increase of 16.2 percent in audit hours, and an increase of about $4 in the hourly billing rate, for each earnings manipulation risk factor identified. For a client with one earnings manipulation risk factor and one corporate governance risk factor, model coefficients imply an increase of 20 percent in audit hours, and an increase of about $11 in the hourly billing rate. Because our sample includes a significant number of clients with neither earnings manipulation risk nor corporate governance risk, and a few clients with a high number of these risks, we conducted sensitivity tests to determine the robustness of our results. When we remove clients that do not have either earnings manipulation risk or corporate gover- nance risk, testing the models on only those clients with one or more of these risk factors, inferences from our results are unchanged: earnings manipulation risk is associated with increases in planned audit hours and billing rates, and there are positive interactions of earnings manipulation risk and corporate governance risk in both the planned hours and billing rate models. When we remove clients with two or more risk factors in either cate- gory, we continue to find that earnings manipulation risk is associated with increases in planned audit hours and planned billing rates, but the interactive effects of earnings ma- nipulation risk and corporate governance risk are no longer significant in either model. We infer that the interaction results that we report are driven by the clients with higher numbers of earnings manipulation or corporate governance risks. The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. We discuss background literature and hypotheses in Section II, followed by a description of our methods in Section III. We discuss results in Section IV. We discuss limitations and our conclusions in Section V. II. BACKGROUND AND HYPOTHESES Earnings Manipulation Risk The financial press, regulators, and prior academic research report many instances of alleged earnings manipulation (e.g., DeAngelo 1988; Fox 1997; Levitt 1998; Loomis 1999; Gaver and Paterson 2001; Nelson et al. 2002; Norris and Eichenwald 2002). Prior evidence also indicates that the capital markets react negatively to alleged instances of earnings manipulation. For example, Feroz et al. (1991) and Dechow et al. (1996) document about a 9 percent decline in stock price in response to the initial announcement of alleged earnings manipulation by companies. It is well understood that public dissemination of negative information about clients, and resulting stock price declines, expose auditors to litigation The Accounting Review, April 2004 280 This content downloaded from 35.155.246.157 on Mon, 14 Sep 2020 07:55:06 UTC All use subject to http Earnings Manipulation, Corporate Governance, and Auditors' Decisions risk and reputational damage (St. Pierre and Anderson 1984; Palmrose 1987; Stice 1991; Pratt and Stice 1994; Heninger 2001; Weber et al. 2001). Auditing standards suggest that auditors should respond to engagement risks by altering the nature, timing, and extent of audit procedures (e.g., SAS No. 47, AICPA 1983; SAS No. 82, AICPA 1997). Considering prior research, behavioral experiments generally report results consistent with recommendations and requirements in the auditing standards, finding evidence of risk responsiveness in both planning and pricing decisions (e.g., Messier and Plumlee 1987; Maletta and Kida 1993; Bedard and Wright 1994; Pratt and Stice 1994; Zimbelman 1997; Houston et al. 1999; Johnstone 2000; Asare and Wright 2002; Glover et al. 2002; Graham and Bedard 2003). However, results of archival studies on auditors' risk responsiveness are mixed. Some recent studies report that auditors adapt their planning and/ or pricing decisions to assessed risks (e.g., Davis et al. 1993; Bell et al. 2001; Johnstone and Bedard 2001; Mock and Turner 2002), while other studies report that they do not (Bedard 1989; Mock and Wright 1993, 999; O'Keefe et al. 1994; Simunic and Stein 1996).5 Prior research, however, does not directly examine the relationship between auditors' perceived earnings manipulation risk and their planning and pricing decisions.6 The current paper investigates this important relationship. Given auditors' downside risk associated with both actual ptand attempted eaings manipulation (i.e., litigation risk and reputational dam- age), we propose the following hypotheses: Hla: There will be a positive relationship between earnings manipulation risk and planned audit hours. Hib: There will be a positive relationship between earnings manipulation risk and billing rates. Corporate Governance Risk As part of the overall internal control environment, boards of directors and audit com- mittees have a responsibility to provide oversight on the reliability of financial reporting (Loebbecke et al. 1989; Wild 1996; Beasley et al. 1997; Blue Ribbon Committee 1999; Johnstone et al. 2001; Abbott et al. 2002). Prior empirical research provides some evidence of a positive relationship between the quality of corporate governance and the reliability of financial reporting. For example, companies without audit committees are more likely to This paper differs in two important ways from Johnstone and Bedard (2001). First, the sample in that study was derived from a firm's client acceptance database, so the risk assessments in that research were based upon preliminary evaluations of clients for which the firm had no prior experience, unlike the continuing client sample in this paper. Further. , the sample in Johnstone and Bedard (2001) is dominated by privately held clients (87 percent private clients), whereas our sample includes only public clients. Earnings manipulation, and the asso- ciated downside risk for the audit firm, is more relevant for public clients. Second, Johnstone and Bedard (2001) investigate the effects of a fraud risk measure, which focuses almost exclusively on the risk factors included in the "management's characteristics and influence over the control environment" section of SAS No. 82 (AICPA 1997). In contrast, this paper focuses on auditors' responses to specific indications of earnings manipulation behavior, which encompasses both GAAP and non-GAAP interventions in financial reporting. 6 Because earnings manipulation risk encompasses the risk of non-GAAP management interventions in financial reporting, some of the components of the earnings manipulation risk variable are also fraud risk indicators. For example, in some instances, management's financial reporting choices are clearly within GAAP, while in other instances these choices are clearly fraud. Within these bounds, there exists a gray area. For a discussion of the continuum from earnings management to fraud, see Public Oversight Board (2000, 77-83). Prior research addresses the relationship between fraud risk and audit planning, using experimental data (e.g., Zimbelman 1997; Asare and Wright 2002; Glover et al. 2002; Graham and Bedard 2003) and archival data (e.g., Mock and Turner 2002). The Accounting Review, April 2004 281 This content downloaded from 35.155.246.157 on Mon, 14 Sep 2020 07:55:06 UTC All use subject to http Bedard and Johnstone have fraudulent financial reporting (Dechow et al. 1996; McMullen 1996) and earnings overstatements as revealed by prior period adjustments (DeFond and Jiambalvo 1991). Fraud is also more likely among companies having fewer independent members on the board of directors and the audit committee (Beasley 1996; Dechow et al. 1996; Abbott et al. 2000; Beasley et al. 2000), and those having audit committees that meet infrequently (Abbott et al. 2000). These studies imply that when this key element of oversight is missing, there are likely to be consequences in terms of financial reporting quality. As part of their financial reporting oversight role, boards of directors and audit com- mittees should support external auditors as they work to address financial reporting risks (Public Oversight Board 1993, 1994; Blue Ribbon Committee 1999). However, there is little specific professional guidance on the role of corporate agovernance in the conduct of the audit. Recently, research has begun to address the effect of variance in corporate gov- ernance quality/risk on auditors' decisions and audit outcomes. Two such studies provide evidence that characteristics of audit committees influence the extent of support for auditors against management in contentious situations. DeZoort and Salterio (2001) find that audit committee members with less corporate governance experience and less financial reporting/ auditing knowledge are less supportive of an external auditor who advocates a "substance over form" approach in a dispute with client management. Carcello and Neal (2000) find that for companies experiencing financial distress, there is a significant negative relationship between the presence of affiliated (i.e., nonindependent) directors on the audit committee and the incidence of going-concern opinions. Further, Cohen et al. (2002) report that au- ditors generally find audit committees to be ineffective in overseeing the financial reporting process, lacking the expertise and power to perform this role. These studies suggest that auditors should consider the effectiveness of their clients' corporate governance processes because those processes may affect audit risk and auditor business risk. Prior research shows that auditors increase engagement effort for clients with significant internal control weaknesses in general (Wallace 1984; Kaplan 1985; Kruetzfeldt and Wallace 1986), consistent with professional standards (AICPA 1995, AU 319.19, 319.20, 319.26). However, there is very little research examining weakness in corporate governance specifically. One study that does address this issue is Cohen and Hanno (2000). Auditors in their experimental setting planned increased substantive testing in the presence of ineffective corporate governance. In sum, the risk-based perspective of the research cited above suggests a positive relationship between corporate governance risk (i.e., lower cor- porate governance quality) and audit effort, suggesting the following hypothesis: H2a: There will be a positive relationship between corporate governance risk and planned audit hours. In addition to considering the relationship between corporate governance risk and planned audit hours, we also consider its relationship with pricing. As previously noted, there is mixed evidence on the extent to which auditors adjust audit fees in the presence of heightened risk. However, several recent studies (e.g., Davis et al. 1993; Bell et al. 2001; Johnstone and Bedard 2001) report that fees are higher for riskier clients. The results of these studies imply that auditors will charge clients with higher corporate governance risk higher billing rates due to the audit firm's need to cover potentially higher incremental costs associated with such clients. In contrast to this risk-based perspective, several studies adopt a demand-based per- spective regarding the role of corporate governance in audit pricing, arguing that board/ audit committee characteristics indicative of higher quality corporate governance will be The Accounting Review, April 2004 282 This content downloaded from 35.155.246.157 on Mon, 14 Sep 2020 07:55:06 UTC All use subject to http Earnings Manipulation, Corporate Governance, and Auditors' Decisions associated with higher audit fees because of a demand for higher audit quality. In the U.K., Collier and Gregory (1996) find that in the early 1990s, the presence of an audit committee was associated with an increase in fees. In contrast, Goddard and Masters (2000) find no differences in audit fees between companies that adhere to the U.K.'s Cadbury Code standards for audit committees and those that do not.7 In the U.S. environment, Carcello et al. (2002) find that board of director independence (percentage of outside directors), diligence (number of meetings), and expertise (number of outside directorships held in other corporations) are positively associated with audit fees. However, they find that audit committee independence, diligence, and expertise are not associated with audit fees (after controlling for board of director characteristics). Thus, these studies provide limited support for the theory that high-quality corporate governance leads to higher audit fees via a demand effect.8 There are two important difficulties associated with these demand-perspective studies that prevent unambiguous application to our setting. First, data used in these prior studies were not collected for the purpose of auditors' risk management, as is the case for this study. Our measures include auditors' direct assessments of corporate goveance a risk (e.g., assessments of problematic resignations, insufficiency of information provided to board of director or audit committee members, and inadequate financial literacy). In contrast, data used in prior studies include very general proxies for corporate governance quality (e.g., the existence of an audit committee, the number of meetings, and the number of outside directorships). This difference in focus is important because our data include risk assess- ments made by audit partners of their existing clients for the purpose of considering under what conditions the audit firm would continue to provide service to the client. Because of auditors' significant litigation risk, it seems logical that the identification of heightened corporate governance risk will be associated with increased billing rates. Second, the the- oretical assumption underlying these prior studies is that board of director/audit committee members are actively involved in audit fee setting (i.e., that audit committees demand higher or lower audit fees depending on corporate governance quality). However, these studies use data from 1991 (Collier and Gregory 1999), 1992-1993 (Carcello et al. 2002), and 1996 (Goddard and Masters 2000), a time period in which such active involvement seems un- likely. Speaking to the general lack of audit committee involvement during that time period, Corrin (1993) notes that audit committee involvement was "little more than a diplomatic sideshow." Providing more recent evidence on this point, Cohen et al. (2002) find that auditors view management as the primary driver of corporate governance, and that they view audit committees as typically ineffective and with little real power. It has not been until very recently that audit committee members have realistically become more involved in issues such as fee setting and audit decision making (e.g., Blue Ribbon Committee 1999; U.S. House of Representatives, Committee on Financial Services 2002). 7 The Cadbury Code requires that audit committees meet certain minimum standards, including: (1) reporting on the quality of corporate controls, (2) disclosing committee membership, (3) being composed of nonexecutive directors, and (4) meeting at least twice a year. 8 These studies may find mixed results for two reasons. First, these studies measure corporate governance quality in different ways. Collier and Gregory (1996) measure it as the existence of an audit committee; Goddard and Masters (2000) measure it as whether a company adheres to the Cadbury Code; Carcello et al. (2002) measure it as the percentage of independent audit committee members, the number of meetings, and the number of similar positions held in other corporations. Second, data in these studies come from varying regulatory envi- ronments, since Collier and Gregory (1996) and Goddard and Masters (2000) use data from the U.K. (where audit committees are voluntary), whereas Carcello et al. (2002) use data from the U.S. (where audit committees are mandatory for companies traded on the major stock exchanges). Both of these differences make comparisons of these studies' results problematic. The Accounting Review, April 2004 283 This content downloaded from 35.155.246.157 on Mon, 14 Sep 2020 07:55:06 UTC All use subject to http Bedard and Johnstone In contrast to assuming that boards of director/audit committees are actively involved in audit pricing, we analyze audit pricing directly from the auditors' perspective, based on their identification of heightened corporate governance risk. This increases the power to detect a positive relationship between corporate governance risk and billing rates, if one exists. As such, we propose that: H2b: There will be a positive relationship between corporate governance risk and bill- ing rates. Interactive Relationships of Earnings Manipulation Risk, Corporate Governance Risk, and Auditors' Planning and Pricing Decisions We also examine whether the relationship between earnings manipulation risk and audit planning and pricing decisions varies with changes in the level of corporate governance risk. Several studies cited previously (e.g., Dechow et al. 1996; Beasley et al. 2000) provide evidence that corporate governance is associated with earnings quality. Related to earnings management specifically, both Chtourou et al. (2001) and Klein (2002) show that audit committee characteristics such as independence and expertise are associated with reductions in discretionary accruals. We extend this line of research by investigating auditors' effort and billing rate decisions in the presence of both earnings manipulation risk and corporate governance risk. Specif- ically, we expect a positive interaction between these two sources of risk. When the auditor detects evidence that client management may be aggressively manipulating earnings, and features of the client's board and audit committee indicate that these individuals cannot be relied upon to help control management's behavior, the relationship between earnings ma- nipulation risk and audit planning and pricing decisions should be greater than in the absence of such indications of heightened risk. Based on this discussion, we propose the following interaction hypotheses: H3a: The positive relationship between earnings manipulation risk and planned audit hours will be greater for clients with heightened corporate governance risk. H3b: The positive relationship between earnings manipulation risk and billing rates will be greater for clients with heightened corporate governance risk. III. METHOD Sample The data used in this research are derived from engagement partners' assessments of their existing clients made during the participating firm's 2000-2001 client continuance risk assessment process, during which the firm's engagement partners consider the risks posed by their clients and make planning and pricing decisions. Following that process, we obtained information on the population of the firm's continuing, public client engagements. We deleted approximately 7 percent of these clients due to missing data, leaving over 1,000 for hypothesis testing.9 Variable Definitions Our primary empirical tests concern how earnings manipulation risk and corporate governance risk are associated with engagement planning and pricing. Dependent variables 9 We have been requested not to disclose the exact number of public clients. The Accounting Review, April 2004 284 This content downloaded from 35.155.246.157 on Mon, 14 Sep 2020 07:55:06 UTC All use subject to http Earnings Manipulation, Corporate Governance, and Auditors' Decisions in the models are the natural log of HOURS (total planned audit hours) and BILLRATE (the hourly billing rate, which is the total planned fee divided by the total planned personnel hours).10 Earnings Manipulation Risk and Corporate Governance Risk Variables The participating firm's client continuance risk assessment process requires audit part- ners to answer questions concerning a number of risk factors related to earnings manipu- lation and corporate governance. We measure earnings manipulation risk as the number of high-risk responses to "yes/no" questions relating to nine earnings manipulation risk fac- tors (EARNMANIP RISK). The questions are worded such that a "yes" answer represents the high-risk response; we code each "yes" equal to 1 and each "no" equal to 0. The questions relate to the following issues: the company has a history of exactly meeting consensus earnings estimates; the company's stock price is based on an unusually high P/E multiple for its industry; the company has indications of unusually aggressive or cre- ative accounting practices; the company has a history of inaccurate accounting estimates; certain accounting policies may be inappropriate to the business; the engagement team has nonspecific concerns about earnings manipulation; management has provided inaccurate representations, or has been less than forthright about financial reporting issues; there has been a restatement in the last three years, and it was due to intentional manipulation; and the engagement team has concerns about a particular accounting treatment. Some of these questions are similar to factors used in other studies investigating issues related to earnings manipulation (e.g., Dechow et al. 1996; Nelson et al. 2003; Frankel et al. 2002; Johnstone et al. 2002). We measure corporate governance risk as the number of high-risk responses to "yes/ no" questions relating to 11 board of director and audit committee risk factors (CORPGOV RISK). The questions relate to the following issues for board of director members: recent problematic resignations, insufficient independence from management, lack of frequent timely meetings, and lack of availability of information about sensitive issues or information to monitor management. The questions relate to the following issues for audit commit- tee members: lack of a written charter, lack of frequent timely meetings, members who are not outside directors or who are not independent from management, members who are not financially literate, and lack of availability of information to monitor management. Some of these questions are similar to factors used in other studies on the relationship between board of director and audit committee characteristics and behavior, and financial reporting outcomes (e.g., Menon and Williams 1994; Beasley 1996; Beasley et al. 2000; Carcello and Neal 2000; DeZoort and Salterio 2001; Raghunandan et al. 2001; Carcello et al. 2002). Control Variables We control for other factors that may affect the relationships between the earnings manipulation risk and corporate governance risk variables and the dependent variables. These include variables common to the audit planning and pricing literatures, such as those measuring the client's size, financial condition, internal controls, and industry membership. We include the natural log of total assets (InASSETS) in the model to control for greater audit effort and increased auditor business risk (i.e., litigation or reputation risks) for audits of large clients (e.g., Palmrose 1986a, 1986b; Francis 1984; Francis and Simon 1987; 10 The data do not contain effort estimates by staffing level, so the billing rate is best viewed as an expected average of the rate per hour across all staffing levels and types. The billing rate is the amount that the participating firm expects to receive (i.e., it is not a "standard" rate that would subsequently be reduced via a "realization" reduction). The Accounting Review, April 2004 285 This content downloaded from 35.155.246.157 on Mon, 14 Sep 2020 07:55:06 UTC All use subject to http Bedard and Johnstone O'Keefe et al. 1994; Davidson and Gist 1996; Johnstone et al. 2004)." We expect a positive relationship between client size and both audit effort and the billing rate. We also control for factors related to the client's financial condition. Audit firms gen- erally apply more effort and charge higher billing rates to the audits of financially weaker clients (e.g., Simunic 1984; O'Keefe et al. 1994; Simon 1985; Stice 1991; Stein et al. 1994; Houston et al. 1999; Bell et al. 2001; Johnstone 2000; Johnstone and Bedard 2001). There- fore, we expect a positive relationship between LEVERAGE (total liabilities divided by total assets) and both audit effort and the billing rate, and we expect a negative relationship between ROA (net income divided by total assets) and both audit effort and the billing rate. Further, we control for internal control quality using the engagement team's judgment of whether the client does (WEAK CONTROLS 1) or does not (WEAK CONTROLS = 0) have any significant internal control weaknesses. We also include several dichotomous control variables for industry membership, which is found by prior research to be associated with audit planning and pricing decisions (e.g., Stein et al.1994; Hackenbrack and Knechel 1997; Johnstone and Bedard 2001). These variables represent the firm's own industry categorizations, and indicate whether the com- panies operate in the retail (IND-RETAIL), financial services (IND-FINSERV), manufactur- ing (IND-MANUFACTURING), high technology (IND-HIGHTECH), or other industries (e.g., service industries; IND-OTHER). Models of Planned Audit Hours and Billing Rates We model the natural log of planned audit hours and planned average billing rates as functions of earnings manipulation risk, corporate governance risk, their interaction, and control variables, as follows: ln(HOURS) = ao + a, EARNMANIP RISK + a2 CORPGOV RISK + a3 CORPGOV RISK * EARNMANIP RISK + a4 InASSETS + aS LEVERAGE + a6 ROA + a7 WEAK CONTROLS + a8 IND-RETAIL + a9 IND-FINSERV + al, IND-MANUFACTURING + a,, IND-HIGH TECH + u (1) BILLRATE = bo + b, EARNMANIP RISK + b2 CORPGOV RISK + b3 CORPGOV RISK * EARNMANIP RISK + b4 InASSETS + b5 LEVERAGE + b6 ROA + b7 WEAK CONTROLS + b8 IND-RETAIL + bg IND-FINSERV + b,o IND-MANUFACTURING + b,, IND-HIGH TECH + u' (2) where: HOURS = planned audit personnel hours; BILLRATE = planned hourly billing rate; 11 We winsorized the financial variables at +/- three standard deviations. The Accounting Review, April 2004 286 This content downloaded from 35.155.246.157 on Mon, 14 Sep 2020 07:55:06 UTC All use subject to http Earnings Manipulation, Corporate Governance, and Auditors' Decisions EARNMANIP RISK = CORPGOV RISK = ASSETS = LEVERAGE = ROA = WEAK CONTROLS = IND-RETAIL = IND-FINSERV = IND-MANUFACTURING = IND-HIGH TECH = u, u' = Descriptive Statistics number of high-risk responses to earings manipulation risk questions; number of high-risk responses to board of director and audit committee quesitons; total assets (in thousands); total liabilities - total assets; net income + total assets; 1 if client possesses significant internal control weaknesses, 0 otherwise; 1 if retail industry, 0 otherwise; 1 if financial services industry, 0 otherwise; 1 if manufacturing industry, 0 otherwise; 1 if hightechnology industry; 0 otherwise; and error terms. IV. RESULTS Table 1 presents descriptive statistics on variables included in the models.12 Panel A shows that the mean (median) number of planned total audit hours is 1,880 (760) hours, with a mean (median) average hourly billing rate of $161 ($150). The highest number of earnings manipulation risk factors for any client is 7.0, and the mean (median) number is 0.26 (0.00). The distribution of earnings manipulation risk factors (not tabled) shows that 81.0 percent of clients have zero earnings manipulation risk factors, 15.1 percent have one, 2.5 percent have two, 0.9 percent have three, and 0.5 percent have four or more risk factors. The highest number of corporate governance risk factors is 6.0, with a mean (median) of 0.25 (0.00). The distribution of corporate governance risk factors (not tabled) shows that 83.8 percent of clients have zero corporate governance risk factors, 10.8 percent have one, 3.0 percent have two, 1.5 percent have three, and 0.9 percent have four or more risk factors. The mean (median) asset value for clients in the sample is about $5.3 billion ($275 million). Mean (median) LEVERAGE and ROA a R re 0.79 (0.59) and -0.12 (0.01), respectively.'3 Finally, only 2 percent of clients have significant internal control weaknesses identified. Table 1, Panel B provides distributionspecific descriptive statistics for clients with various levels of earnings manipulation risk and corporate governance risk. The descriptive statistics show that a significant percentage of the sample (68 percent) has no earnings manipulation or corporate governance risk factors, 13 percent of the sample (8 percent + 5 percent) has one or more corporate governance risk factors only, and 16 percent of the sample (13 percent + 3 percent) has one or more earnings manipulation risk factors only. Just 1 percent of the sample has more than one corporate governance risk factor and more than one earnings manipulation risk factor. The descriptive statistics also show that clients with zero or one of the risk factors have a lower billing rate ($155-$166 per hour) 12 We have been requested not to disclose the relative industry composition of the sample. 13 A limitation of our data is that it does not contain client names, so we are unable to gather publicly available proxies for corporate governance risk or earnings manipulation risk. To provide a comparison between our sample and the market as a whole during this period, we calculated descriptive statistics from the Compustat database on our financial variables. Our sample is similar to the population of public companies on these variables. For example, in 2000, mean (median) total assets is $4.6 billion ($182 million), and in 2001 it is $4.8 billion ($186 million). In 2000, mean (median) leverage is 1.86 (0.59), and in 2001 it is 2.60 (0.61). In 2000, mean (median) return on assets is -0.10 (0.01), and in 2001 it is 0.15 (0.01). The Accounting Review, April 2004 287 This content downloaded from 35.155.246.157 on Mon, 14 Sep 2020 07:55:06 UTC All use subject to http 00 00 TABLE 1 Descriptive Statistics Panel A: Overall Descriptive Statistics Variable Name HOURS BILLRATE EARNMANIP RISK CORPGOV RISK ASSETS LEVERAGE ROA WEAK CONTROLS Variable Description Planned audit personnel hours Planned hourly billing rate Sum of high-risk responses to earnings manipulation risk questions Sum of high-risk responses to board of director and audit committee questions Total assets (in thousands) Total liabilities + total assets Net income - total assets 1 if client possesses significant internal control weaknesses; 0 otherwise Minimum 32.00 50.00 0.00 0.00 12.00 0.00 -69.12 0.00 Maximum 100,000.00 382.00 7.00 6.00 123,645,161 82.26 15.79 1.00 Mean (Median) 1879.65 (760.00) 160.79 (150.00) 0.26 (0.00) 0.25 (0.00) 5,336,839 (275,256) 0.79 (0.59) -0.12 (0.01) 0.02 (0.00) Std. Deviation 5117.21 44.95 0.66 0.71 20,647,614 3.98 2.63 0.15 (continued on next page) This content downloaded from 35.155.246.157 on Mon, 14 Sep 2020 07:55:06 UTC All use subject to http F. c- TABLE 1 (continued) Panel B: Distribution-Specific Descriptive Statistics for Levels of EARNMGT RISK and CORPGOV RISK" CORPGOV RISK = 0 CORPGOV RISK = 1 CORPGOV RISK > 1 EARNMGT RISK = 0 68% 8% 5% $159 ($43) $155 ($38) $163 ($50) 0.11 (1.50) 0.21 (1.22) 0.34 (1.36) EARNMGT RISK = 1 13% 2% 0% $166 ($50) $156 ($38) $218 ($90) 0.05 (0.37) 0.01 (0.01) 0.06 (0.11) EARNMGTRISK > 1 3% 0% 1% $176 ($46) $188 ($74) $213 ($89) 0.03 (0.11) 0.01 (0.01) 0.01 (0.01) a In Panel B values in cells represent the percentage of the total sample in each category, the mean (standard deviation) of BILLRATE, and the mean (standard deviation) of HOURS/ASSETS. 00 O0 This content downloaded from 35.155.246.157 on Mon, 14 Sep 2020 07:55:06 UTC All use subject to http Bedard and Johnstone than clients with more than one of the risk factors ($163-$218), although the ratio of planned personnel hours to total assets is similar for all clients (ranging from 0.01-0.21 for clients with zero or one of the risk factors to 0.01-0.34 for clients with more than one of the risk factors). Table 2 provides descriptive information on the frequency of risk factors that make up the EARNMANIP RISK and CORPGOV RISK variables. The most common risk factor for EARNMANIP RISK is a history of exactly meeting consensus earnings estimates (e.g., 35 percent of EARNMANIP RISK factors identified involved a history of exactly meeting con- sensus earnings estimates), followed by a high P/E multiple (17 percent), indications of unusually aggressive or creative accounting practices (12 percent), and a history of inac- curate accounting estimates (10 percent). For CORPGOV RISK, the most common risk factors are a lack of a formal written charter for the audit committee (e.g., 26 percent of CORPGOV RISK factors identified involved a lack of a formal written audit committee charter), problematic resignations of board of director members (13 percent), an insuffi- ciently independent board of directors (12 percent), an audit committee that meets infre- quently with management (13 percent), and audit committee members that are not outside directors (12 percent). Table 3 presents correlations among earnings manipulation risk, corporate governance risk, and control variables. Earnings manipulation risk is positively correlated with planned audit hours and planned average billing rates, while corporate governance risk is not sig- nificantly correlated with either of those dependent variables. Earnings manipulation risk is positively correlated with client size, leverage, and weak controls, while coporate gov- ernance risk is negatively correlated with client size and return on assets. However, earnings manipulation risk and corporate governance risk are not significantly correlated with each other, implying that weak governance is not necessarily associated with aggressive earnings behavior. Model of Planned Audit Hours Results of Full-Sample Model Table 4 presents results from estimating Model 1, an OLS regression of planned audit hours on earnings manipulation risk, corporate governance risk, and control variables, using all clients.'4 Results of the full-sample model indicate that earnings manipulation risk is positively associated with planned audit hours (t = 4.058, p = 0.000), consistent with Hla. Since the dependent variable is the natural log of audit hours, the coefficient on EARN- MANIP RISK implies that for each earnings manipulation risk factor present for a client, audit hours increase by 16.2 percent.15 Therefore, for the average client with 1,880 en- gagement hours, model coefficients imply an increase of 305 hours (i.e., 1,880 x 0.162) for a client with one earnings manipulation risk factor. In contrast, corporate governance risk is not associated with planned audit hours, so the results are not consistent with H2a. However, the interaction is marginally significant (t = 1.610, p = 0.054), implying that the 14 Tests of OLS regression assumptions for Models 1 and 2 show no violations. White's (1980) test reveals no heteroscedasticity. Variance inflation factors (VIF) and condition indices indicate no collinearity problems (Belsley et al. 1980; Neter et al. 1985), as the highest VIF is 3.291 and the highest condition index is 24. Further, we examined the data for influential outliers and find that removing the largest four, six, or eight outliers, respectively, in both the hours and billing rate models only acts to improve the significance levels of reported results (and inferences remain unchanged). 15 The interpretation of a regression coefficient for an independent variable that is not logged, in a model in which the dependent variable is logged, is that it is a proportionate response (i.e., a percentage change in the dependent variable associated with a one-unit change in the independent variable) (see Johnston and DiNardo 1997, 46). The Accounting Review, April 2004 290 This content downloaded from 35.155.246.157 on Mon, 14 Sep 2020 07:55:06 UTC All use subject to http Earnings Manipulation, Corporate Governance, and Auditors' Decisions TABLE 2 Relative Frequency of Earnings Manipulation Risk and Corporate Governance Risk Factors Number of % of Total "Yes" "Yes" Earnings Manipulation Risk Factors Responses Responses * Company has a history of exactly meeting consensus 113 35 earnings estimatesa * Company's stock price is based on an unusually high PE 55 17 multiple for its industry * Company has indications of unusually aggressive or creative 38 12 accounting practices * Company has a history of inaccurate accounting estimates 35 10 * Certain accounting policies may be inappropriate to the 26 8 business * The engagement team has nonspecific concerns about 18 6 earnings management * Management has provided inaccurate representations, or has 17 5 been less than forthright about financial reporting issues * There has been a restatement in the last three years, and it 17 5 was due to intentional manipulation * The engagement team has concerns about a particular 9 2 accounting treatment Total 328 100% Corporate Governance Risk Factors Board of Directors * There are recent problematic resignations of BOD members 42 13 * The BOD is insufficiently independent from management 40 12 * The BOD does not hold frequent timely meetings with CFO 18 6 and accounting officers * The BOD is not provided sufficient timely information to 6 2 allow for monitoring of important management behavior * The BOD is not provided sufficient timely information about 5 1 sensitive issues Audit Committees ? The AC does not have a formal written charter 85 26 ? The AC does not hold frequent timely meetings with the 42 13 CFO or other accounting officers ? The AC members are not made up of outside directors 40 12 ? The AC is insufficiently independent from management 19 6 ? The AC members are not financially literate 18 6 ? The AC is not provided sufficient timely information to allow 10 3 for monitoring of important management behavior Total 325 100% a This table illustrates the relative frequency of the risk factors making up the measures of earnings manipulation risk and corporate governance risk. Each percentage represents the relative frequency of that particular risk factor in terms of the total number of risk factors identified for that measure across the sample population. For example, 35 percent of earnings manipulation risk factors identified involved a history of exactly meeting consensus earnings estimates. The Accounting Review, April 2004 291 This content downloaded from 35.155.246.157 on Mon, 14 Sep 2020 07:55:06 UTC All use subject to http TABLE 3 Correlation Matrix ?Z ~1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. 11. 12. 13. 1. InHOURS 1.000 2. BILLRATE 0.055* 1.000 3. EARNMANIP RISK 0.170** 0.109** 1.000 4. CORPGOV RISK -0.048 0.046 0.006 1.000 5. InASSETS 0.437** -0.098** 0.057* 0.105** 1.000 ,o 6. LEVERAGE 0.083** 0.010 0.081** -0.015 0.010 1.000 7. ROA 0.006 -0.033 0.010 -0.057* 0.104** 0.156** 1.000 8. WEAK CONTROLS 0.125** 0.082** 0.085** 0.022 0.107** -0.001 0.002 1.000 9. IND-RETAIL 0.091** 0.024 0.011 0.031 -0.019 -0.018 -0.033 - 0.031 1.000 10. IND-FINSERV -0.044 -0.129** -0.059* -0.089** 0.294** 0.023 0.059* 0.042 0.271** 1.000 11. IND-OTHER 0.033 -0.190** -0.051 0.084* -0.124** -0.023 0.013 0.006 0.119** -0.213** 1.000 12. IND-MANUFACTURING -0.016 -0.044 0.053 -0.029 -0.135** 0.048 0.027 -0.022 -0.205** -0.369** -0.162** 1.000 13. IND-HIGH TECH -0.029 0.292** 0.039 0.046 -0.259** -0.043 -0.074** -0.004 -0.217** -0.390** -0.171** -0.295** 1.000 * and ** indicate that the estimated coefficients are significantly different from zero at the 5 percent and 1 percent levels, respectively, in two-tailed tests. Pearson correlations are reported; Spearman correlations yield similar results. This content downloaded from 35.155.246.157 on Mon, 14 Sep 2020 07:55:06 UTC All use subject to http TABLE 4 Ordinary Least Squares Regression of the Natural Logarithm of Planned Audit Hours on Earnings Manipulation Risk, Corporate Governance Risk, and Control Variables (1) ln(HOURS) = aO + a, EARNMANIP RISK + a2 CORPGOV RISK + a3 CORPGOV RISK * EARNMANIP RISK + a4 InASSETS + a5 LEVERAGE + a6 ROA + a7 WEAK CONTROLS + a8 IND-RETAIL + a9 IND-FINSERV + alo IND-MANUFACTURING + a1l IND-HIGH TECH + u Variable Name CONSTANT EARNMANIP RISK (H a) CORPGOV RISK (H2a) CORPGOV RISK x EARNMANIP RISK (H3a) % LnASSETS ? LEVERAGE x ROA . IWEAK CONTROLS Predicted Sign + ? + + + + Full-Sample Model Coefficient (t-statistic) 2.715 (11.119)*** 0.162 (4.058)*** -0.048 (-1.229) 0.086 (1.610)* 0.203 (18.290)*** 0.021 (3.324)*** -0.017 (1.777)** 0.480 (2.940)*** Reduced-Sample Models Model A Coefficient (t-statistic) 3.039 (7.250)*** 0.150 (2.666)*** -0.079 (-1.483) 0.096 (1.688)** 0.196 (10.249)*** 0.006 (0.787) 0.016 (- 1.625)* 0.531 (2.303)** Model B Coefficient (t-statistic) 2.727 (10.971)*** 0.192 (2.599)*** -0.048 (-1.206) 0.125 (1.126) 0.201 (17.796)*** 0.054 (5.089)*** -0.011 (-1.141) 0.475 (2.825)*** C- c~ I" ;3 Z. I1~ IZ (Z IZ Mocel C Coefficient (t-statistic) 2.571 (10.092)*** 0.159 (3.904)*** -0.026 (-0.283) 0.153 (1.055) 0.208 (17.925)*** 0.021 (3.244)*** -0.017 (1.730)** 0.472 (2.788)*** (continued on next page) This content downloaded from 35.155.246.157 on Mon, 14 Sep 2020 07:55:06 UTC All use subject to http TABLE 4 (continued) Variable Name IND-RETAIL IND-FINSERV IND-MANUFACTURING IND-HIGH TECH Model Fstatistic Adjusted R2 Predicted Sign + + + Full-Sample Model Coefficient (t-statistic) 0.320 (2.888)*** -0.217 (-2.253)** 0.137 (1.328) 0.226 (2.196)** 40.553*** 0.255 The following symbols indicate significant effects: * = < 0.10; ** = < 0.05; *** = < 0.01. Tests of directional expectations are one-tailed, while all other tests are two-tailed. The full-sample model reports results for the entire sample. The reduced-sample models report results of sensitivity tests eliminating clients with various characteristics. Model A shows results eliminating those clients with zero CORPGOV RISK and EARNMANIP RISK factors. Model B shows results eliminating those clients with two or more EARNMANIP RISK factors. Model C shows results eliminating those clients with two or more CORPGOV RISK factors. Reduced-Sample Models Model A Coefficient (t-statistic) 0.246 (1.420) -0.386 (-2.408)** -0.013 (-0.077) 0.073 (0.441) 17.431*** 0.306 Model B Coefficient (t-statistic) 0.313 (2.804)*** -0.228 (-2.355)** 0.134 (1.287) 0.238 (2.298)** 37.452*** 0.247 Mocel C Coefficient (t-statistic) 0.374 (3.261)*** -0.175 (- 1.737)* 0.202 (1.874)* 0.274 (2.548)** 37.222*** 0.249 This content downloaded from 35.155.246.157 on Mon, 14 Sep 2020 07:55:06 UTC All use subject to http Earnings Manipulation, Corporate Governance, and Auditors' Decisions positive relationship between earnings manipulation risk and planned audit hours is some- what higher for clients with heightened corporate governance risk, consistent with H3a. The coefficients of Model 1 imply that for a client with one earnings manipulation risk factor and one corporate governance risk factor, audit hours increase by 20 percent (i.e., 0.162 - 0.048 + 0.086), which for the average client with 1,880 engagement hours amounts to an increase of 376 hours (i.e., 1,880 x 0.20). For the control variables, the results indicate that the firm plans more effort for larger clients (t = 18.290, p = 0.000), those with weaker financial condition (t = 3.324, p = 0.001 and t = -1.777, p = 0.038 for LEVERAGE and ROA, respectively), and those with internal control weaknesses (t = 2.940, p = 0.002). The coefficients on the industry variables are generally significant as well. These results suggest that clients in the retail and high-technology industries have higher planned audit effort on average, while those in the financial services industry have lower planned effort, than clients in the other (i.e., service) industries. Results of Reduced-Sample Models Because our sample includes a significant number of clients with neither earnings manipulation risk nor corporate governance risk, and a few clients with higher numbers of these risk factors, we conducted sensitivity tests to determine the robustness of our results. To examine the sensitivity of our results to excluding those clients with neither earnings manipulation risk nor corporate governance risk, we removed these clients from the sample (see Table 4, Reduced-Sample Model A). The inferences from our results are the same as those in the full-sample model, i.e., earnings manipulation risk is positively associated with planned audit hours (t = 2.666, p = 0.004) and the interaction of CORPGOV RISK x EARNMANIP RISK is significant (t = 1.688, p = 0.046). This implies that among the set of clients with some risk factors in each category, the relationship of planned effort decisions to risk is stronger as the number of risk factors increases. To examine the sensitivity of our results to excluding those clients with relatively high numbers of earnings manipulation risk or corporate governance risk, we removed these clients from the sample (see Table 4, Reduced-Sample Models B and C). The results con- tinue to indicate that earnings manipulation risk is positively associated with planned audit hours (t = 2.599, p = 0.005; t = 3.904, p = 0.000, respectively), but the interaction of CORPGOV RISK x EARNMANIP RISK, while still positive in sign, is no longer significant (t = 1.126, p = 0.130; t = 1.055, p = 0.146, respectively). Thus, the interaction results that we report in the full-sample model are driven by the clients with relatively high num- bers of earnings manipulation or corporate governance risks. Model of Planned Average Billing Rates Results of Full-Sample Model Table 5 presents results from estimating Model 2, an OLS regression of the planned average hourly billing rates on earnings manipulation risk, corporate governance risk, and control variables. Results of the full-sample model indicate that earnings manipulation risk is positively associated with average billing rates (t = 2.151, p = 0.016), consistent with Hlb. The results imply that for each earnings manipulation risk factor present, the billing rate increases by $4.06 per hour of effort. In contrast, corporate governance risk is not associated with planned billing rates, so the results are not consistent with H2b. However, the positive relationship between earnings manipulation risk and planned billing rates is greater for clients with heightened corporate governance risk (i.e., a significant interaction) (t = 2.585, p = 0.005), consistent with H3b. These results imply that the hourly billing The Accounting Review, April 2004 295 This content downloaded from 35.155.246.157 on Mon, 14 Sep 2020 07:55:06 UTC All use subject to http t,) C0N TABLE 5 Ordinary Least Squares Regression of Planned Average Hourly Billing Rates on Earnings Manipulation Risk, Corporate Governance Risk, and Control Variables (2) BILLRATE = bo + b, EARNMANIP RISK + b2 CORPGOV RISK + b3 CORPGOV RISK * EARNMANIP RISK + b4 InASSETS + b5 LEVERAGE + b6 ROA + b7 WEAK CONTROLS + b8 IND-RETAIL + b9 IND-FINSERV + blo IND-MANUFACTURING + blI IND-HIGH TECH + u' Variable Name CONSTANT EARNMANIP RISK (H a) CORPGOV RISK (H2a) CORPGOV RISK x EARNMANIP RISK (H3a) LnASSETS LEVERAGE Predicted Sign + + + + + ROA WEAK CONTROLS + Full-Sample Model Coefficient (t-statistic) 135.960 (11.773)*** 4.056 (2.151)** 0.390 (0.209) 6.556 (2.585)*** -0.239 (-0.456) 0.189 (0.628) -0.136 (-0.296) 23.308 (3.016)*** Reduced-Sample Models Model A Coefficient (t-statistic) 151.195 (7.403)*** 4.455 (1.620)* 0.466 (0.179) 6.411 (2.310)** -1.253 (-1.344) 0.677 (1.751)** -0.181 (-0.368) 30.925 (2.753)*** Model B Coefficient (t-statistic) 131.409 (11.213)*** 4.476 (1.288)* 0.831 (0.440) 1.807 (0.347) -0.033 (-0.062) -0.596 (-1.178) -0.304 (-0.661) 25.932 (3.268)*** (continued on next page) Model C Coefficient (t-statistic) 136.400 (11.483)*** 4.684 (2.462)*** -3.028 (0.719) -1.154 (-0.170) -0.153 (-0.283) 0.155 (0.519) -0.032 (-0.070) 21.048 (2.667)*** This content downloaded from 35.155.246.157 on Mon, 14 Sep 2020 07:55:06 UTC All use subject to http TABLE 5 (continued) IND-RETAIL + 29.611 29.616 30.122 27.979 (5.651)*** (3.506)*** (5.722)*** (5.225)*** IND-FINSERV + 19.412 20.836 20.181 18.204 (4.261)*** (2.669)*** (4.417)*** (3.874)*** IND-MANUFACTURING + 23.114 22.353 25.645 20.749 (4.742)*** (2.746)*** (5.222)*** (4.136)*** IND-HIGH TECH + 49.946 59.582 50.203 47.311 (10.275)*** (7.435)*** (10.258)*** (9.445)*** Model F-statistic 17.447*** 10.894*** 14.920*** 13.860*** ; Adjusted R2 0.124 0.210 0.111 0.105 The following symbols indicate significant effects: * = < 0.10; ** = < 0.05; *** = < 0.01. Tests of directional expectations are one-tailed, while all other tests are two-tailed. The full-sample model reports results for the entire sample. The reduced-sample models report results of sensitivity tests eliminating clients with various characteristics. Model A shows results eliminating those clients with zero CORPGOV RISK and EARNMANIP RISK factors. Model B shows results eliminating those clients with two or more EARNMANIP RISK factors. , Model C shows results eliminating those clients with two or more CORPGOV RISK factors. This content downloaded from 35.155.246.157 on Mon, 14 Sep 2020 07:55:06 UTC All use subject to http Bedard and Johnstone rate for clients with one earnings manipulation risk factor and one corporate governance risk factor is about $11 higher than the rate for a client with no such risk factors (i.e., 4.056 + 0.39 + 6.556). For the control variables, results indicate that billing rates are positively associated with internal control weaknesses (t = 3.016, p = 0.002), but are unaffected by client size and financial condition. This implies that the effects of size and financial condition on the total audit fee are due to differences in effort, while there is an incremental effect of internal control weakness on audit fees beyond the incremental effort observed in Model 1. The industry control variables are all positive and significant in this model, indicating higher billing rates in these industries relative to those in other (i.e., service) industries. Results of Reduced-Sample Models To examine the sensitivity of our results to excluding those clients with neither earnings manipulation risk nor corporate governance risk, we removed these clients from the sample (see Table 5, ReducedSample Model A). The inferences from our results are the same as those in the full-sample model, i.e., earnings manipulation risk is positively associated with the billing rate (t = 1.620, p = 0.053) and the interaction of CORPGOV RISK x EARNMANIP RISK is significant (t = 2.310, p = 0.011). To examine the sensitivity of our results to excluding those clients with high numbers of earnings manipulation risk or corporate governance risk, we removed these clients from the sample (see Table 5, Reduced- Sample Models B and C). The results continue to indicate that earnings manipulation risk is positively associated with the billing rate (t = 1.288, p = 0.099; t = 2.462, p = 0.007, respectively), but the interaction of CORPGOV RISK x EARNMANIP RISK is no longer significant (t = 0.347, p = 0.365; t = -0.170, p = 0.433, respectively). Thus, results of this sensitivity analysis are consistent with the sensitivity analysis in the models of planned hours. The effect of earnings manipulation risk is consistently strong, but the significance of the interaction varies. Among clients with some recognized risk factors, the positive interaction of earnings manipulation risk and corporate governance risk remains. In contrast, when the sample is restricted to clients with zero or one risk factors by category, the interaction loses significance. Variable Validation While prior research and firm personnel provided validation for the earnings manipu- lation and corporate governance risk variables, we also obtained independent verification of the choices of questions to include as measures of these variables. Two researchers familiar with the earnings manipulation and corporate governance literatures assessed whether a set of possibly relevant questions should be included as an earnings manipulation risk factor, a corporate governance risk factor, or neither. Each individual rated the questions independently, and then met to reconcile any differences, leading to a final reconciled list. Based on this process, we added a question to the corporate governance risk variable (audit committee has no formal written charter). The final list did not include two of the earnings manipulation risk questions (stock price based on unusually high P/E multiple, and en- gagement team has concerns about a particular accounting treatment). In a sensitivity test removing these questions, we find that the results are very similar to those we report, except that the main effect for EARNMANIP RISK in the full-sample billing rate model becomes marginally significant (t = 1.462, p = 0.072), and inferences are unchanged. The Accounting Review, April 2004 298 This content downloaded from f:ffff:ffff:ffff:ffff:ffff:ffff on Thu, 01 Jan 1976 12:34:56 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.o Earnings Manipulation, Corporate Governance, and Auditors' Decisions V. LIMITATIONS AND CONCLUSIONS Limitations This paper has several limitations. First, the data are derived from a single firm. As a result, we must await disclosure of similar data by other firms to determine whether our findings hold on a profession-wide basis. However, using data from a single firm has the advantage of allowing the investigation of a large sample of risk assessments made using common information and procedures, thus potentially increasing the power of empirical tests (O'Keefe et al. 1994). Second, the data represent risk assessments and planned audit effort and billing rate decisions, which do not allow for analysis of actual engagement actions implemented by the auditors in the presence of their risk assessments. However, since our sample is composed of continuing audit engagements, the auditors' ability to provide reasonable estimates of planned audit hours is likely better than it would be for initial audit engagements. This limitation suggests that future research on the actual conduct of engagements will be useful in order to more completely understand auditors' decisions relating to earnings manipulation risk and corporate governance risk. Third, the data do not indicate length of auditor tenure. However, the sample includes only continuing clients, so at least one engagement has been performed. Much of the prior literature on audit effort and fees does not measure auditor tenure (e.g., Davis et al. 1993), although O'Keefe et al. (1994) do include this variable, finding no relationship between tenure and either the hours or audit fees. Fourth, we do not control for the relationship between audit firm office location and billing rates. An interesting extension of our research would be to analyze differences in auditors' risk-responsiveness by office, region, or line of business. Fifth, as is common in audit planning research, auditors' risk assessments are not exogenous. The same engagement team members assess risk, plan hours, and plan billing rates. As such, the judgment process resulting in the earnings management risk and corporate governance risk assessments is not independent of the decision-making process that produces the effort and billing rate decisions. Conclusions The purpose of this paper is to investigate auditors' assessments of and planning and pricing decisions related to earnings manipulation risk and corporate governance risk. Our primary finding is that heightened earnings manipulation risk is associated with an increase in planned audit effort, and with increased billing rates. For example, model coefficients from the full-sample models imply an increase of 16.2 percent in hours and about $4 in the hourly billing rate for a client with one earnings manipulation risk factor. Future re- search should address the actual use and effectiveness of various strategies that can be adopted by audit firms to apply the incremental planned effort and fees. For instance, auditors could add specific tests designed to detect the presence of certain entries that could be used to manage earnings in a particular industry. In addition, they could increase the extent of testing in targeted areas that are highly susceptible to earnings manipulation, such as complex or end-of-period transactions. Further, they could make alternative personnel assignments to accomplish the preceding tasks. The positive relationship between the billing rate and earnings manipulation risk is also consistent with several possible actions on the part of auditors. For example, increased average billing rates related to earnings manipu- lation risk may imply that auditors are recovering costs associated with the above types of effort-related actions. In addition, it may also imply that they are anticipating the necessity of funds to address unforeseen longer-term costs (i.e., a risk premium associated with potential future litigation) associated with clients possessing this risk. The Accounting Review, April 2004 299 This content downloaded from 35.155.246.157 on Mon, 14 Sep 2020 07:55:06 UTC All use subject to http Bedard and Johnstone In contrast to our findings for earnings manipulation risk, the results of the full-sample models show that auditors' planning and pricing decisions are less strongly related to cor- porate governance risk. Specifically, we find no main effect of corporate governance risk associated with planned effort or billing rates. Rather, corporate governance risk is asso- ciated only with increases in planned effort or billing rates when earnings manipulation risk is already heightened. The interactive relationship of earnings manipulation risk and corporate governance risk with auditors' planning and pricing decisions suggests that au- ditors are most concerned about corporate governance risk when there are signals that client management is "playing games" with earnings. From field interviews, Cohen et al. (2002) conclude that auditors generally consider boards and audit committees to be less influential than management in corporate gover- nance, but that boards and audit committees are of greater importance when client risks are high due to a greater need for monitoring and guidance in that setting. Our results build on those findings, because we show that when earnings manipulation risk is low, corporate governance risk is not associated with either planned effort or billing rates. However, when earnings manipulation risk is heightened, auditors increase planned hours and billing rates to a greater extent in situations where they are less likely to receive support from the client's board or audit committee. Since our findings suggest a relationship between corporate governance and pricing only for those clients also at risk of earnings manipulation, further research on the implications of specific corporate governance characteristics for effective corporate control, and auditors' responses to these characteristics, is clearly needed. While results of both full-sample models show interactions between corporate gover- nance risk and earnings manipulation risk, results of sensitivity tests in the reduced-sample models reveal that the interactions in both the hours and billing rate models are driven by the relatively few clients with more than two earnings manipulation or corporate governance risk factors. Therefore, it appears that in situations where there is heightened earnings manipulation risk, corporate governance must be particularly weak in order to affect the relationship between earnings manipulation risk and audit planning and pricing decisions. Our data show that relatively few clients are assessed as having more than two factors in either risk category. In current practice, one difficulty that audit firms face is to identify the riskiest clients from their portfolios and to plan and price those engagements (e.g., John- stone and Beddard 2004). While our data indicate relatively few clients of this firm are recognized as being at high risk on dimensions of earnings manipulation and corporate governance risk, these are of key importance from the point of view of overall audit firm risk management. REFERENCES Abbott, L. J., Y. Park, and S. Parker. 2000. The effects of audit committee activity and independence on corporate fraud. Managerial Finance 26 (11): 55-67. , S. Parker, G. Peters, and K. Raghunandan. 2002. An empirical investigation of audit fees, non-audit fees and audit committees. Working paper, University of Memphis. American Institute of Certified Public Accountants (AICPA). 1983. Audit Risk and Materiality in Conducting an Audit. Statement on Auditing Standards No. 47. New York, NY: AICPA. . 1988. Auditing Accounting Estimates. Statement on Auditing Standards No. 57. New York, NY: AICPA. . 1995. Consideration of Internal Control in a Financial Statement Audit: An Amendment to Statement on Auditing Standards No. 55. Statement on Auditing Standards No. 78. New York, NY: AICPA. The Accounting Review, April 2004 300 This content downloaded from 35.155.246.157 on Mon, 14 Sep 2020 07:55:06 UTC All use subject to http Earnings Manipulation, Corporate Governance, and Auditors' Decisions . 1997. Consideration of Fraud in a Financial Statement Audit. Statement on Auditing Stan- dards No. 82. New York, NY: AICPA. Asare, S. K., and A. Wright. 2002. The impact of fraud risk assessments and a standard audit program on fraud detection plans. Working paper, University of Florida. Barton, J. 2001. Does the use of financial derivatives affect earnings management decisions? The Accounting Review (January): 1-26. Beasley, M. 1996. An empirical analysis of the relation between the board of director composition and financial statement fraud. The Accounting Review 71 (October): 443-465. , J. V. Carcello, and D. R. Hermanson. 1997. Fraudulent Financial Reporting: 1987-1997. New York, NY: COSO. , , ,and P. Lapides. 2000. Fraudulent financial reporting: Consideration of in- dustry traits and corporate governance mechanisms. Accounting Horizons 14 (December): 441- 454. Becker, C. L., M. L. DeFond, J. Jiambalvo, and K. F. Subramanyam. 1998. The effect of audit quality on earnings management. Contemporary Accounting Research 15 (Spring): 1-24. Bedard, J. C. 1989. An archival survey of audit program planning. Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory (Fall): 5771. , and S. Biggs. 1991. The effect of domain-specific experience on evaluation of management representations in analytical procedures. Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory 10 (Supple- ment): 77-90. , and A. Wright. 1994. The functionality of decision heuristics: Reliance on prior audit ad- justments in evidential planning. Behavioral Research in Accounting (Supplement): 62-89. Bell, T. B., W. R. Landsman, and D. A. Shackelford. 2001. Auditors' perceived business risk and audit fees: Analysis and evidence. Journal of Accounting Research 39 (June): 35-43. , J. C. Bedard, K. M. Johnstone, and E. F. Smith. 2002. KRiskSM: A computerized decision aid for client acceptance and continuance risk assessments. Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory 21 (September): 97-113. Belsley, D. A., E. Kuh, and R. E. Welsch. 1980. Regression Diagnostics Identifying Influential Data and Sources of Collinearity. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons. Blue Ribbon Committee (BRC). 1999. Report and Recommendations on Improving the Effectiveness of Corporate Audit Committees. New York, NY: The New York Stock Exchange and The Na- tional Association of Securities Dealers. Bonner, S., Z-V. Palmrose, and S. M. Young. 1998. Fraud type and auditor litigation: An analysis of SEC accounting and auditing enforcement releases. The Accounting Review 73 (October): 503- 532. Carcello, J. V., and T. Neal. 2000. Audit committee composition and auditor reporting. The Accounting Review 75 (October): 453-467. , D. R. Hermanson, T. L. Neal, and R. R. Riley. 2002. Board characteristics and audit fees. Contemporary Accounting Research 19 (3): 365-384. Chtourou, S. M., J. Bedard, and L. Courteau. 2001. Corporate governance and earnings management. Working paper, Universite Laval. Cohen, J. R., and D. M. Hanno. 2000. Auditors' consideration of corporate governance and manage- ment control philosophy in preplanning and planning judgments. Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory 19 (2): 133-146. , G. Krishnamoorthy, and A. Wright. 2002. Corporate governance and the audit process. Con- temporary Accounting Research 19 (4): 573-594. Collier, P., and A. Gregory. 1996. Audit committee effectiveness and the audit fee. The European Accounting Review 5 (2): 177-198. Corrin, J. 1993. A blatant slur on executive directors' integrity. Accountancy 111 (April): 81-82. Davidson, R. A., and W. E. Gist. 1996. Empirical evidence on the functional relation between audit planning and total audit effort. Journal of Accounting Research 34 (Spring): 111-124. Davis, L. R., D. N. Ricchuite, and G. Trompeter. 1993. Audit effort, audit fees, and the provision of nonaudit services to audit clients. The Accounting Review 68 (January): 135-150. The Accounting Review, April 2004 301 This content downloaded from 35.155.246.157 on Mon, 14 Sep 2020 07:55:06 UTC All use subject to http Bedard and Johnstone DeAngelo, L. 1988. Managerial competition, information costs, and corporate governance. Journal of Accounting and Economics 10: 3-36. Dechow, P., R. Sloan, and A. Sweeney. 1996. Causes and consequences of earnings manipulation: An analysis of firms subject to enforcement actions by the SEC. Contemporary Accounting Research 13: 1-26. DeFond, M. L., and J. Jiambalvo. 1991. Incidence and circumstances of accounting errors. The Ac- counting Review (July): 643-655. , and . 1993. Factors related to auditor-client disagreements over income-increasing accounting methods. Contemporary Accounting Research 9 (Spring): 415-443. , and C. W. Park. 1997. Smoothing income in anticipation of future earnings. Journal of Accounting and Economics 23 (July): 115-139. DeZoort, T., and S. Salterio. 2001. The effects of corporate governance experience and financial- reporting and audit knowledge on audit committee members' judgments. Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory 20 (September): 31-47. Feroz, E. H., K. Park, and V. S. Pastena. 1991. The financial and market effects of the SEC's ac- counting and auditing enforcement releases. Journal of Accounting Research 29 (Supplement): 107-142. Fox, J. 1997. Learn to play the earnings game (and Wall Street will love you). Fortune (March 31): 76-80. Francis, J. R. 1984. The effect of audit firm size on audit prices: A study of the Australian market. Journal of Accounting and Economics (6): 133-151. , and D. T. Simon. 1987. A test of audit pricing in the small-client segment of the U.S. audit market. The Accounting Review 62 (January): 145-157. Frankel, R. M., M. F. Johnson, and K. K. Nelson. 2002. The relation between auditors' fees for non- audit services and earnings quality. The Accounting Review 77 (Supplement): 71-105. Gaver, J. J., and J. S. Paterson. 2001. The association between external monitoring and earnings management in the property-casualty insurance industry. Journal of Accounting Research 39 (2): 269-282. Glover, S. M., D. F. Prawitt, J. J. Schultz, and M. F. Zimbelman. 2002. Changes in auditors' fraud- related planning judgments since the issuance of SAS No. 82. Working paper, Brigham Young University. Goddard, A. R., and C. Masters. 2000. Audit committees, Cadbury Code, and audit fees: An empirical analysis of U.K. companies. Managerial Auditing Journal 15 (7): 358-371. Graham, L. E., and J. C. Bedard. 2003. Fraud risk and audit planning. International Journal of Auditing (March): 55-70. Hackenbrack, K., and W. R. Knechel. 1997. Resource allocation decisions in audit engagements. Contemporary Accounting Research 14 (Fall): 481-499. Healy, P. M., and J. M. Wahlen. 1999. A review of the earnings management literature and its implications for standard setting. Accounting Horizons 13 (December): 365-383. Heninger, W. G. 2001. The association between auditor litigation and abnormal accruals. The Ac- counting Review 76 (January): 111-126. Houston, R. W., M. F. Peters, and J. H. Pratt. 1999. The audit risk model, business risk, and audit- planning decisions. The Accounting Review 74 (July): 281-298. Johnson, P., K. Jamal, and G. Berryman. 1991. Effects of framing on auditor decisions. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 50: 75-105. Johnston, J., and J. DiNardo. 1997. Econometric Methods. Fourth edition. New York, NY: McGraw Hill. Johnstone, K. M. 2000. Client acceptance decisions: Simultaneous effects of client business risk, audit risk, auditor business risk, and risk adaptation. Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory 19 (Spring): 1-27. , and J. C. Bedard. 2001. Engagement planning, bid pricing, and client response in the market for initial attest engagements. The Accounting Review 76 (2): 199-220. The Accounting Review, April 2004 302 This content downloaded from 35.155.246.157 on Mon, 14 Sep 2020 07:55:06 UTC All use subject to http Earnings Manipulation, Corporate Governance, and Auditors'Decisions , M. H. Sutton, and T. D. Warfield. 2001. Antecedents and consequences of independence risk: Framework for analysis. Accounting Horizons (March): 1-18. , J. C. Bedard, and S. F. Biggs. 2002. Aggressive client reporting: Factors affecting auditors' generation of financial reporting alternatives. Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory (March): 47-65. , and . 2003. Risk management in client acceptance decisions. The Accounting Review 78 (October): 1003-1025. , and . 2004. Audit firm portfolio management decisions. Journal of Accounting Re- search (forthcoming). , and M. L. Ettredge. 2004. The effect of competitive bidding on engagement planning and pricing. Contemporary Accounting Research 21 (1). Kaplan, S. E. 1985. An examination of the effects of environment and explicit internal control on planned audit hours. Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory (Fall): 12-25. Klein, A. 2002. Audit committee, board of director characteristics, and earnings management. Journal of Accounting and Economics 33: 375-400. Kreutzfeldt, R. W., and W. A. Wallace. 1986. Error characteristics in audit populations: Their profile and relationship to environmental factors. Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory (Fall): 20- 43. Levitt, A. 1998. The numbers game. Remarks delivered at the NYU Center for Law and Business, New York, NY, September 28. . 1999. Quality information: The lifeblood of our markets. Remarks delivered at the Economic Club of New York, New York, NY, October 18. . 2000. Renewing the covenant with investors. Remarks delivered at the New York University Center for Law and Business, New York, NY, May 10. Loebbecke, J. K., M. M. Eining, and J. J. Willingham. 1989. Auditors' experience with material irregularities: Frequency, nature, and detectability. Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory (Fall): 1-28. Loomis, C. J. 1999. Lies, damned lies, and managed earnings: The crackdown is here. Fortune (August 2): 75-92. Maletta, M., and T. Kida. 1993. The effect of risk factors on auditors' configural information proc- essing. The Accounting Review 68 (January): 681-691. McMullen, D. A. 1996. Audit committee performance: An investigation of the consequences associ- ated with audit committees. Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory (Spring): 87-103. Menon, K., and J. D. Williams. 1994. The use of audit committees for monitoring. Journal of Ac- counting and Public Policy 13: 121-139. Messier, W., and D. Plumlee. 1987. The effects of anticipation and frequency of errors on auditors' selection of substantive procedures. Accounting and Business Research: 349-358. Mock, T. J., and A. Wright. 1993. An exploratory study of auditors' evidential planning judgments. Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory 12 (Fall): 39-61. , and . 1999. Are audit program plans risk-adjusted? Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory 18 (Spring): 55-74. , and J. L. Turner. 2002. An archival study of audit fraud risk assessments made under SAS No. 82. Working paper, University of Southern California. Nelson, M. W., J. A. Elliott, and R. L. Tarpley. 2003. How are earnings managed? Examples from auditors. Accounting Horizons 17 (Supplement): 17-35. , , and . 2002. Evidence from auditors about managers' and auditors' earnings- management decisions. The Accounting Review 77 (Supplement): 175-202. Neter, J., W. Wasserman, and M. H. Kutner. 1985. Applied Linear Statistical Models: Regression, Analysis of Variance, and Experimental Designs. Second edition. Homewood, IL: Irwin. Norris, F., and K. Eichenwald. 2002. Fuzzy rules of accounting and Enron. The New York Times (January 30): C1. O'Keefe, T. B., D. A. Simunic, and M. T. Stein. 1994. The production of audit services: Evidence from a major public accounting firm. Journal of Accounting Research 32 (Autumn): 241-261. The Accounting Review, April 2004 303 This content downloaded from 35.155.246.157 on Mon, 14 Sep 2020 07:55:06 UTC All use subject to http Bedard and Johnstone Palmrose, Z-V. 1986a. Audit fees and auditor size: Further evidence. Journal of Accounting Research 24 (Spring): 97-110. . 1986b. The effect of nonaudit services on the pricing of audit services: Further evidence. Journal of Accounting Research 24 (Autumn): 405411. . 1987. Litigation and independent auditors: The role of business failures and management fraud. Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory 6 (Spring): 90-103. Pratt, J., and J. D. Stice. 1994. The effects of client characteristics on auditor litigation risk judgments, required audit evidence, and recommended audit fees. The Accounting Review 69 (October): 639-656. Public Oversight Board (POB). 1993. Issues Confronting the Accounting Profession. Stamford, CT: POB. 1994. Strengthening the Professionalism of the Independent Auditor. Stamford, CT: POB. 2000. Panel on Audit Effectiveness Report and Recommendations. Stamford, CT: POB. Raghunandan, K., W. Read, and D. Rama. 2001. Audit committee composition, "gray directors," and interaction with internal auditing. Accounting Horizons 15 (June): 105-118. St. Pierre, K., and J. Anderson. 1984. An analysis of the factors associated with lawsuits against public accountants. The Accounting Review 59 (April): 242-263. Simon, D. T. 1985. The audit services market: Additional empirical evidence. Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory 5 (Fall): 71-78. Simunic, D. A. 1984. Auditing, consulting, and auditor independence. Journal of Accounting Research 22 (Autumn): 679-702. , and M. T. Stein. 1996. The impact of litigation risk on audit pricing: A review of the economics and the evidence. Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory 15 (Supplement): 119- 134. Solomon, I., M. Shields, and 0. R. Whittington. 1999. What do industry specialist auditors know? Journal of Accounting Research 37 (Spring): 191-208. Stein, M. T., D. A. Simunic, and T. B. O'Keefe. 1994. Industry differences in the production of audit services. Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory 13 (Supplement): 128-142. Stice, J. D. 1991. Using financial and market information to identify pre-engagement factors associated with lawsuits against auditors. The Accounting Review 66 (July): 516-533. Subramanyam, K. R. 1996. The pricing of discretionary accruals. Journal of Accounting and Eco- nomics 22 (AugustDecember): 249-281. U.S. House of Representatives, Committee on Financial Services. 2002. Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002. Public Law No. 107-204. Washington, D. C.: Government Printing Office. Wallace, W. 1984. A Time Series Analysis of the Effect of Internal Audit Activities on External Fees. Altamonte Springs, FL: Institute of Internal Auditors Research Foundation. Watts, R. L., and J. L. Zimmerman. 1986. Positive Accounting Theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall. Weber, J., D. Little, D. Henry, and L. Lavelle. 2001. Arthur Andersen: How bad will it get? BusinessWeek (December 24). White, H. 1980. A heteroscedasticity-consistent covariance matrix and a direct test for heteroscedas- ticity. Econometrica (48, May): 817-838. Wild, J. 1996. The audit committee and earnings quality. Journal of Accounting, Auditing & Finance (Spring): 247-276. Winograd, B. N., J. S. Gerson, B. L. Berlin. 2000. Audit practices of PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC). Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory (Fall): 175-182. Zimbelman, M. F. 1997. The effects of SAS No. 82 on auditors' attention to fraud risk factors and audit planning decisions. Journal of Accounting Research 35 (Supplement): 75-97. The Accounting Review, April 2004 304 This content downloaded from 35.155.246.157 on Mon, 14 Sep 2020