![[Javier E. Díaz-Vera] Metaphor and Metonymy acros(BookZZ.org)](http://s2.studylib.es/store/data/008964531_1-381f886bf81fda028f44f5c0bed7b0f2-768x994.png)

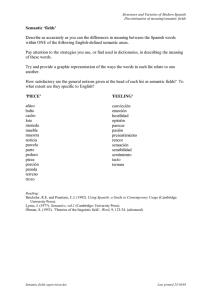

Javier E. Díaz-Vera (Ed.)

Metaphor and Metonymy across Time and Cultures

Cognitive Linguistics Research

Editors

Dirk Geeraerts

John R. Taylor

Honorary editors

René Dirven

Ronald W. Langacker

Volume 52

Metaphor and

Metonymy across

Time and Cultures

Perspectives on the Sociohistorical Linguistics

of Figurative Language

Edited by

Javier E. Díaz-Vera

DE GRUYTER

MOUTON

ISBN 978-3-11-033543-9

e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-033545-3

e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-039539-6

ISSN 1861-4132

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

A CIP catalog record for this book has been applied for at the Library of Congress

Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek

The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie;

detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de.

© 2015 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Munich/Boston

Typesetting: Meta Systems Publishing & Printservices GmbH, Wustermark

Printing and binding: CPI books GmbH, Leck

♾ Printed on acid-free paper

Printed in Germany

www.degruyter.com

Contents

Introductory chapter

Javier E. Díaz-Vera

Figuration and language history: Universality and variation

3

Diachronic metaphor research

Dirk Geeraerts

Four guidelines for diachronic metaphor research

15

Conceptual variation and change

Kathryn Allan

Lost in transmission? The sense development of borrowed metaphor

31

Xavier Dekeyser

Loss of the prototypical meaning and lexical borrowing: A case of semantic

51

redeployment

Roslyn M. Frank

A complex adaptive systems approach to language, cultural schemas and

serial metonymy: Charting the cognitive innovations of ‘fingers’ and ‘claws’

65

in Basque

Richard Trim

The interface between synchronic and diachronic conceptual metaphor:

95

The role of embodiment, culture and semantic field

Figuration and grammaticalization

Andrew D. M. Smith and Stefan H. Höfler

The pivotal role of metaphor in the evolution of human language

Miao-Hsia Chang

Two counter-expectation markers in Chinese

141

123

vi

Contents

Wolfgang Schulze

The emergence of diathesis markers from MOTION concepts

171

Figurative language in culture variation

Javier E. Díaz-Vera and Teodoro Manrique-Antón

‘Better shamed before one than shamed before all’: Shaping shame in Old

English and Old Norse texts

225

Dylan Glynn

The conceptual profile of the lexeme home: A multifactorial diachronic

265

analysis

Cristóbal Pagán Cánovas

Cognitive patterns in Greek poetic metaphors of emotion: A diachronic

295

approach

Juan Gabriel Vázquez González

‘Thou com’st in such a questionable shape’: Embodying the cultural model

319

for ghost across the history of English

Index

349

Introductory chapter

Javier E. Díaz-Vera

Figuration and language history:

Universality and variation

And make time’s spoils despised everywhere

Give my love fame faster than time wastes life;

So, thou prevene’st his scythe and crooked knife.

Shakespeare, Sonnet 100 (11–14)

1 Figuration and lexico-semantic change

These verses by Shakespeare illustrate one instance of what literary theorists

have traditionally referred to as figurative language: the attribution of typically

human features to an abstract entity. Such figures of speech as personification,

simile, irony, hyperbole, metaphor and metonymy have been traditionally described as poetic devices used by writers for specific aesthetic purposes. Only

after the late-twentieth century development of Conceptual Metaphor Theory

(henceforth CMT; Lakoff and Johnson 1980, Ortony 1993, Goatly 2007), figurative language started to attract the attention of a growing number of linguists

interested in the study of these figures of speech within the realm of everyday

language and, much more importantly, of our ordinary conceptual system.

CMT has since developed and elaborated, although not always in complete

agreement.

Figuration refers to a meaning that is dependent on a figurative extension

from another meaning. Figurative language has got an inherently second-order

nature. Figurative expressions (such as it made my blood boil) can only be

recognized as such because of their contrast with more literal expressions (as

in it made me angry). From a diachronic perspective, figurative expressions are

historically later than the corresponding conventional ones. As Croft and Cruse

(2004) put it, metaphors have their own life-cycle that normally runs from a

first coinage as an instance of semantic innovation (a novel metaphor requiring

an interpretative strategy on the side of language user) to a more commonplace

metaphor (a conventional metaphor whose meaning has become well-established in the speakers’ mental lexicon). Eventually, the literal meaning of an

expression may fall out of use, interrupting its dependency relationship with

the corresponding figurative meaning (a dead metaphor).

Javier E. Díaz-Vera: Universidad de Castilla-La Mancha

4

Javier E. Díaz-Vera

Cognitive semantics regards polysemy as involving family resemblances,

stressing the systematic relationship between the different meanings (both literal and figurative) of a word and including polysemy as a result of conceptual

organisation such as categorisation. This view has given rise to a variety of

models for lexical networks (Lakoff 1987; Langacker 1990) based on the notion

that the different meanings of a lexeme “form a radially structured category,

with a central member and links defined by image-schema transformation and

metaphors” (Lakoff 1987: 460). In other words, each instantiation of a word

always retains its whole range of senses regardless of the context in which it

appears, senses which are related to one another by various means. Thus, a

given word belongs to a complex semantic network determined by different

domains and cognitive processes, where there may be senses more representative than others. Things being so, it can be argued that these polysemic networks are shaped by the course of a series of diachronic processes of semantic

extension, through which new figurative expressions emerge and evolve. As

Nerlich and Clarke (2001: 252) put it,

metaphor is a pragmatic strategy used by speakers to convey to hearers something new

that cannot easily be said or understood otherwise or to give an old concept a novel, witty

or amusing package, whereas metonymy is a pragmatic strategy used by speakers to convey to hearers something new about something already well known. Using metaphors

speakers tell you more than what they actually say, using metonyms they tell you more

while saying less. From the point of view of the hearer, metaphor is a strategy used to

extract new information from old words, whereas metonymy is a strategy used to extract

more information from fewer words.

For example, the progressive rise in the frequency of embodied expressions

showing the anger is the heat of a fluid in a container emotion metaphor

in a corpus of 11th to 15th century English texts has been connected to the popularization of humoural doctrine in later medieval England, according to which

anger is an effect of the overproduction of yellow bile (or choler), considered

a warm and dry substance (Gevaert 2002: 202). As Gevaert convincingly shows,

the use of words and expressions directly taken from the humoural theory,

such as the verbs ME distemperen and boilen, indicates a completely different

conceptualization of anger by speakers of Middle English. As this new cultural

model advanced, people started to use the original heat-related items as anger

expressions, which clearly differ from the old anger expressions in terms of

their capacity to add new information (as encoded in the metaphor anger is

the heat of a fluid in a container, which implies not only that anger is a

hot fluid, but also that the body is a container) to the already existing one.

Furthermore, through the expansion of the new anger words over the language

community, this metaphor became a dominant expression of anger in Middle

Figuration and language history: Universality and variation

5

English, producing the progressive neglect of other expressions based on the

Anglo-Saxon anger is swelling metonymy (i.e. emotion is one of the physiological effects of that emotion). As Geeraerts (2010) puts it, “words die

out because speakers refuse to choose them, and words are added to the lexical

inventory of a language because some speakers introduce them and some

others imitate these speakers” (p. 265). These lexical choices show a strong

sociolinguistic facet, characterized by a pragmatic and a cognitive side (Blank

1999: 62): when speakers of a language decide to adopt a new expression because it is convincing to any extent, this is a pragmatic decision based on the

good cognitive performance of the innovation.

Similarly, metonymy has been traditionally described as a cognitive abbreviation mechanism (Esnault 1925), and the metonymical stretching of a word

has been considered an indicator of cost-effective communication. Rather than

adding new information to our knowledge of a given emotional experience,

emotion metonymies exploit a wide range of metonymic relations based on

image-schemata (as in the case of emotion is an effect of that emotion) in

order to let us shorten conceptual distances and ultimately say things quicker

(Nerlich and Clarke 2001: 256). For example, the list of Old English expressions

of fear (Díaz-Vera 2011; Díaz-Vera 2013) includes a wide variety of metonymic

extensions, such as fear is motion backwards (as in OE wandian ‘to turn

away from something’ hence ‘to turn away from a source of fear’), fear is

motion downwards (as in OE creopan ‘to creep’ hence ‘to creep with fear’)

and fear is paralysis (as in OE bīdan ‘to wait’ hence ‘to await with fear’). In

these three cases, the Old English predicates that illustrate these metonymies

are able to express with one single word both (i) the emotion that the experiencer is feeling and (ii) his/her physiological reaction to that emotion. The mechanism followed by these semantic changes is quite evident and straightforward: from a historically earlier meaning (i.e. the prototypical or central meaning of a word, such as ‘to turn away’, ‘to creep’ or ‘to wait’) speakers derive

one (or more, as in the case of serial metonymy) meaning extensions towards

the domain of fear, taking advantage of the widely-known proximity relation

between the emotion and its various effects on the experiencer.

As in the case of metaphor, the cumulative effect of the multiple individual

choices on the side of the speakers will eventually result into a general acceptance of the new metonymic expression over the language community. Furthermore, entire polysemic networks will be developed as a consequence of the

actuation of diachronic metaphor and metonymy over long periods of time

through the progressive addition of new senses to the historically earlier ones.

The detailed reconstruction and analysis of these conceptual networks are indicative not only of the different ways a given domain was conceptualized by

6

Javier E. Díaz-Vera

speakers in the different historical stages of a language but, perhaps more importantly, of some of the possible ways the mind works in conjunction with

language.

2 Figuration and lexico-grammatical change

The impact of figuration on grammatical structure has been demonstrated by

a number of researchers, including Barcelona (2003, 2004, 2005, 2008), Ruiz

de Mendoza Ibanez and Mairal (2007), Ziegeler (2007), Brdar (2007) and Panther, Thornburg and Barcelona (2009). Broadly speaking, these studies show

that there is no clear-cut distinction between the lexicon and grammar. Within

this view, individual lexical items and function words and morphemes are considered meaning-bearing units and, and such, their properties can be motivated by figurative thought.

In the same way as lexemes, grammatical categories frequently convey figurative extended uses, forming networks of related meanings. Grammatical

constructions can be used figuratively and, as in the case of lexical metaphor

and metonymy, they can cue figurative cognitive structures. In fact, the same

general types of conceptual metonymies operate at different linguistic levels.

Diachronic processes of grammatical recategorization illustrate the central role

of metonymy in grammatical change. For example, the Old English noun angul

‘angle’ started to be used as a verb meaning ‘to use an angle’ by the end of the

15th century (instrument for action metonymy). Similarly, the grammatical

recategorization of place names (such as champagne, porto and chianti, all of

which illustrate the metonymic mapping place for product made there) and

personal names (as in a jack, a peter or a magdalen; ideal member for class)

as common nouns can be frequently attributed to metonymic processes.

The relationship between metonymy and metaphor, on the one hand, and

syntactic processes, on the other, has been amply dealt with in recent research.

Tab. 1: Metonymy and metaphor in grammaticalization (Hopper and Traugott 2003)

Metonymy

Metaphor

−

−

−

−

−

−

−

−

Syntagmatic level

Reanalysis (abduction)

Conversational implicature

Operates through interdependent syntactic

constituents

Paradigmatic level

Analogy

Conventional implicature

Operates through conceptual domains

Figuration and language history: Universality and variation

7

Hopper and Traugott (2003) propose a grammaticalization model based on

both metonymy and metaphor, which are seen as pragmatic processes. Whereas metonymy is the result of conversational implicature and is linked to reanalysis, metaphor is the result of conventional inferencing and is linked to

analogy.

According to Hilpert (2007), figuration also plays an important role in the

process of grammaticalization of body part names into prepositions, postpositions or adverbs in a wide variety of languages. For example, the noun head

develops the metaphorical meaning ‘top part’ (metaphor objects are human

beings), from where the grammatical meaning ‘over’ is developed in a number

of languages through the part for orientation metonymy. Also, Barcelona

(2008) shows that metonymy is a conceptual mechanism that operates not only

at the lexical level, but also under the lexicon (phonology, morphemics) and

above the lexicon (phrase, clause, sentence, utterance and discourse).

3 Figuration and conceptual change

One major area of debate is the pretended universality of conceptual patterns.

Cognitive linguists assume that non-literal conceptualizations are grounded in

embodied experience. Things being so, figurative linguistic expressions should

be considered mostly universal and, as such, without a cultural basis. However, cross-cultural studies of figurative expressions clearly show that mental

conceptualizations can differ not only between languages but also between

dialectal and diachronic varieties of the same language. Every single human

language uses non-literal expressions, some of which seem highly stable

across time and space. For example, the conceptual metaphor of journey, according to which we conceptualize such experiences as life or love as a journey,

is recorded in a wide variety of cultures since ancient times. However, different

languages have got different specific-level elaborations of this metaphoric conceptualization, grounded in cultural salience. For example, whereas English

speakers conceptualize love as a journey on a vehicle (either on water or

land), Akan speakers will normally refer to love as a journey on foot, indicating the cultural relevance of walking in their culture (Ansah 2011). In a similar

fashion, multimodal evidence demonstrates that the same concept can be expressed in very different ways: this is the case, for example, of the recurrent

use of ‘loss of hands’ in Japanese mangas with reference to loss of emotional

control (Abbott and Forceville 2011), or the frequent representation of characters with their upper arms attached to the body to indicate fear in the Bayeux

Tapestry (Díaz-Vera 2013).

8

Javier E. Díaz-Vera

Based on these differences, some authors (see especially Kövecses 2000)

have argued the existence of two different levels of conceptualization: a generic level of human embodied cognition and a more specific level of elaboration

of these universal schemas. Conceptual variation, according to these researchers, would be limited to the second level. However, as Gevaert’s (2007) historical data described above shows, cultural variation can also affect general level

conceptualizations. This is the case of the pressurized container metaphor

for emotions, traditionally described as an instance of physiological embodiment. According to her Old English data, Anglo-Saxon speakers show a strong

preference for non-embodied conceptualizations of anger. It is only after the

rise of humoral theory in Western Europe that English (and, probably, other

European vernaculars) will develop new metaphorical expressions based on

the emotion is a hot fluid in a container mapping. The spread and popularization of this medical doctrine produced, to start with, a new physiological

association between emotions (i.e. anger) and bodily temperature (i.e. heat).

As a consequence, speakers of Middle English started to substitute some of

their old literal and figurative emotional expressions by a brand-new set of

metaphors based on the new mapping emotion is a hot fluid in a container.

As demonstrated by Gevaert, cultural change can lead to some forms of

cognitive change which, on the long run, will contribute to the development

and spread of new figurative expressions. More importantly, her study of diachronic variation in figurative language illustrates some of the possible ways

in which cultural practice and knowledge can shape bodily experience by

changing the way we conceptualize and, very probably, feel emotions.

4 Contributions to this volume

The papers included in this volume examine and expand on some of the questions discussed above. The main aim of this book is to provide an interdisciplinary view of diachronic conceptual variation and its linguistic and cultural

manifestations. The volume is arranged in three different sections, ranging

from papers on the analysis of semantic extension through metaphorization,

to the role of figurative language in processes of grammaticalization, and the

interplay between cultural change and figurative language. A foreword by Dirk

Geeraerts introduces a list of frequent shortcomings to avoid by diachronic

metaphor researchers, the so-called four fallacies: ‘the dominant reading only’

fallacy, the ‘semasiology only’ fallacy, the ‘natural experience only’ fallacy and

Figuration and language history: Universality and variation

9

the ‘metaphorization only’ fallacy. A common denominator behind these principles is the recognition that language is culturally transmitted and, as such,

it should be considered a predominantly historical phenomenon.

The first section in this volume focuses on some of the manifold relationships between polysemy, semantic change and figurative language. Kathryn

Allan (“Lost in transmission? The sense development of borrowed metaphor”)

presents a discussion of the significance of borrowing in the histories of metaphors. Through the detailed analysis of the literal and figurative uses of three

different lexical items borrowed by Middle English speakers (the noun muscle,

the verb inculcate and the adjective ardent), the author describes the later evolution of all the senses of these words in the target language. According to her

analysis, while the figurative meanings of these loanwords were retained, their

original, literal meanings were lost in the process of transmission into English.

Similarly, Xavier Dekeyser (“Loss of prototypical meaning and lexical borrowing: A case of semantic redeployment”) describes the process of semantic restructuring undergone by two English lexical sets: the noun and adverb deal

and the verb starve. The study of the meanings expressed by these words

throughout the long period of time between the Old English and the early Modern English period indicates how the original, ancestral meanings of a lexical

item can become peripheral or even get lost in favour of newer, figurative senses of the same word. Roslyn M. Frank (“A complex adaptive systems approach

to language, cultural schemas and serial metonymy: Charting the cognitive

innovations of ‘fingers’ and ‘claws’ in Basque”) proposes a study of the Basque

lexeme hatz and the different meanings developed by it through serial metonymy. Her analysis shows that the lexicon acts both as a memory bank and a

fluid vehicle for the transmission of cultural cognition across time and space.

Finally, Richard Trim (“The interface between synchronic and diachronic conceptual metaphor: The role of embodiment, culture and semantic field”) compares figurative language data from English and Oriental language in order to

analyse variation in synchronic and diachronic metaphor.

The second section focuses on the role of metaphor and metonymy in processes of grammaticalization. The three papers included in this section take the

view that all grammatical elements in language are meaningful and that they

impose and symbolize particular ways of construing conceptual content. In

the opening chapter (“The pivotal role of metaphor in the evolution of human

language”), Andrew D. M. Smith and Stefan H. Höfler claim that the cognitive

mechanisms underlying metaphor can provide a unified explanation of the evolution of two different aspects of language: symbols and grammar. Based on

this model, the authors propose suggest a reconstruction of how human language could have initially emerged from ‘no language’ to complex grammatical

10

Javier E. Díaz-Vera

structures. Miao-Hsia Chang (“Two counter-expectation markers in Chinese”)

studies the origins and the diachronic development of Chinese of sha4 煞

and jieguo 結果, two markers of counter-expectation grammatizalized through

a series of intricate processes of metaphorization, metonymization and metaphtonymy. As the author shows here, the changes undergone by these two

lexemes in the history of Chinese are indicative of the pervasive effect of metaphor and metonymy on the semanticization and adverbialization of a verbal

morpheme from a content word to a highly grammaticalized sentential. Similarly, Wolfgang Schulze (“The emergence of diathesis markers from motion

concepts”) analyses the grammaticalization background behind the development of East Caucasian passive constructions. As the data presented here

shows, verbal forms expressing motion underwent a process of semantic

change into change-of-state and, from there, they grammaticalized into passive auxiliaries.

Conceptual change provides evidence of the link between between linguistic change and sociocultural change. The chapters in the last section explore

some of the relationships between cultural, linguistic and cognitive change.

Javier E. Díaz-Vera and Teodoro Manrique-Antón (“‘Better shamed before one

than shamed before all’: Shaping shame in Old English and Old Norse texts”)

propose an analysis of shame-expressions in Old English and in Old Norse.

According to their research, the Christianization of these two Germanic societies implied the introduction and spread of new shame-related values through

the use of a brand-new set of expressions that illustrate the progressive individualization of this social emotion. Similarly, Dylan Glynn (“The conceptual profile of the lexeme home: A multifactorial diachronic analysis”) proposes a diachronic study of the American concept of home over the course of two centuries. Through the fine-grained analysis of a series of sample texts by three 19th

century American writers, the author demonstrates the feasibility of the multivariate usage-feature method for the description of conceptual structures. Cristóbal Pagán Cánovas (“Cognitive patterns in Greek poetic metaphors of emotion: A diachronic approach”) uses Bending Theory’s dynamic model to analyze love expressions in ancient Greek poetry. Finally, Juan Gabriel Vázquez

González (“‘Thou com’st in such a questionable shape’: Embodying the cultural model for ghost across the history of English”) proposes a contrastive reconstruction of the cultural model for ghost in Old English and in PresentDay British English. The type of cultural variation envisaged by the author

incorporates a diachronic and a within-culture perspective.

In short, the papers in this volume show that metaphor and metonymy are

not just linguistic phenomena but, rather, they reflect dynamic cognitive patterns of thought and emotion. Through the fine-grained examination of dia-

Figuration and language history: Universality and variation

11

chronic data from a variety of languages and linguistic families, this volume

contributes to our understanding of the dominant conceptual mechanisms of

linguistic change and their interaction with sociocultural factors.

References

Abbott, Michael & Charles Forceville. 2011. Visual representations of emotion in manga:

loss of control is loss of hands in Azumanga Daioh volume 4. Language and

Literature 20(2). 1–22.

Ansah, Gladys Nyarko. 2011. The cultural basis of conceptual metaphors: The case of

emotions in Akan and English. In Kathrin Kaufhold, Sharon McCulloch & Ana Tominc

(eds.), Papers from the Lancaster University Postgraduate Conference in Linguistics &

Language Teaching 5, 2–24. Lancaster: Department of Linguistics and English

Language.

Barcelona, Antonio. 2003. Names: A metonymic ‘return ticket’ in five languages. Jezikoslovlje

4: 11–41.

Barcelona, Antonio. 2004. Metonymy behind grammar: The motivation of the seemingly

“irregular” grammatical behavior of English paragon names. In Günter Radden & KlausUwe Panther (eds.), Studies in linguistic motivation, 357–374. Berlin & New York:

Mouton de Gruyter.

Barcelona, Antonio. 2005. The multilevel operation of metonymy in grammar and discourse,

with particular attention to metonymic chain. In Francisco José Ruiz de Mendoza

Ibáñez & M. Sandra Peña Cerbel (eds.), Cognitive linguistics: Internal dynamics and

interdisciplinary interaction, 313–352. Berlin & New York: Mouton de Gruyter.

Barcelona, Antonio. 2008. Metonymy is not just a lexical phenomenon: On the operation of

metonymy in grammar and discourse. In Christina Alm-Arvius, Nils-Lennart

Johannesson & David C. Minuch (eds.), Selected papers from the Stockholm 2008

Metaphor Festival, 3–41. Stockholm: Stockholm University Press.

Brdar, Mario. 2007. Metonymy in grammar: Towards motivating extensions of grammatical

categories and constructions. Osijek: Faculty of Philosophy, Josip Juraj Strossmayer

University.

Croft, William & D. Alan Cruse. 2004. Cognitive linguistics. Cambridge: Cambridge University

Press.

Díaz-Vera, J. E. 2011. Reconstructing the Old English cultural model for ’fear’. Atlantis: Journal

of the Spanish Association of Anglo-American Studies, 33(1). 85–103.

Díaz-Vera, Javier E. 2013. Embodied emotions in medieval English language and visual arts.

In Rosario Caballero & Javier E. Díaz-Vera (eds.), Sensuous cognition — Explorations into

human sentience: Imagination, (e)motion and perception, 195–220. Berlin & New York:

Mouton de Gruyter.

Esnault, Gaston. 1925. L’Imagination populaire − Métaphores occidentales. Paris: Les Presses

Universitaires de France.

Geeraerts, Dirk. 2010. Prospects for the past: Perspectives for diachronic cognitive

semantics. In Margaret E. Winters, Heli Tissari & Kathryn Allan (eds.), Historical

cognitive linguistics, 333–356. Berlin & New York: Mouton de Gruyter.

12

Javier E. Díaz-Vera

Gevaert, Caroline. 2002. The evolution of the lexical and conceptual field of ANGER in Old

and Middle English. In Javier Enrique Díaz-Vera (ed.), A changing world of words:

Studies in English historical lexicology, lexicography and semantics, 275–299.

Amsterdam: Rodopi.

Gevaert, Caroline. 2007. The history of anger: The lexical field of anger from Old to Early

Modern English. Leuven: Katholieke Universiteit Leuven dissertation.

Goatly, Andrew. 2007. Washing the brain: Metaphor and hidden ideology. Amsterdam &

Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

Hilpert, Martin. 2007. Chained metonymies in lexicon and grammar. In Günter Radden,

Klaus-Michael Köpcke, Thomas Berg & Peter Siemund (eds.), Aspects of meaning

construction, 77–98. Amsterdam & Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

Hopper, Paul J., & Elizabeth Closs Traugott. 2003. Grammaticalization, 2nd edn. Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press.

Kövecses, Zoltan. 2000. Metaphor and emotion: Language, culture, and body in human

feeling. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Lakoff, George. 1987. Women, fire and dangerous things. What categories reveal about the

mind. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Lakoff, George & Mark Johnson. 1980. Metaphors we live by. Chicago: University of Chicago

Press.

Langacker, Ronald. 1990. Concept, image and symbol. Berlin & New York: Mouton de

Gruyter.

Nerlich, Brigitte & David D. Clarke. 2001. Serial metonymy: A study of reference-based

polysemisation. Journal of Historical Pragmatics 2(2). 245–272.

Ortony, Andrew. 1993. Metaphor and thought, 2nd edn. Cambridge: Cambridge University

Press.

Panther, Klaus-Uwe & Linda L. Thorburg. 2009. Introduction: On figuration in grammar. In

Antonio Barcelona, Klaus-Uwe Panther, Günter Radden & Linda L. Thorburg (eds.),

Metonymy and metaphor in grammar, 1–44. Amsterdam & Philadelphia: John

Benjamins.

Ruiz de Mendoza, Francisco & Ricardo Mairal. 2007. High-level metaphor and metonymy in

meaning construction. In Günter Radden, Klaus-Michael Köpcke, Thomas Berg & Peter

Siemund (eds.), Aspects of meaning construction in lexicon and grammar, 33–49.

Amsterdam & Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

Ziegeler, Debra. 2007. Arguing the case against coercion. In Günter Radden, Klaus-Michael

Köpcke, Thomas Berg & Peter Siemund (eds.), Aspects of meaning construction in

lexicon and grammar, 99–123. Amsterdam & Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

Diachronic metaphor research

Dirk Geeraerts

Four guidelines for diachronic metaphor

research

Abstract: Drawing on earlier (and fairly scattered) work that I have been doing

on diachronic metaphor theory, I would like to point out a number of difficulties that such studies are faced with. In particular, I will draw the attention to

the following methodological mistakes. The ‘dominant reading only’ fallacy

takes the historically original meaning of an item to be the source of any metaphorical meaning arising in the course of its history. This approach is ironically

a-historical, because it denies the importance of the intermediate steps in a

word’s history. The ‘semasiology only’ fallacy measures the importance of a

metaphorical pattern by counting the relative frequency of semasiological

source-target mappings in the lexical field of the source, rather than the relative (onomasiological) frequency of the source within the field of the target.

The ‘natural experience only’ fallacy substitutes the motivational ground of a

metaphor by the vehicle expressing that ground. While a focus on vehicles

at the expense of grounds is perhaps the most conspicuous danger besetting

Conceptual Metaphor Theory, its consequences for diachronic studies need to

be spelled out. The ‘metaphorization only’ fallacy biases universalist interpretations of metaphorical patterns at the expense of culture-specific analyses.

Methodologically, the universalist attitude neglects the transmitted nature of

language by favouring interpretations that assume direct access to the original

motivation of an expression. The latter assumption also triggers the neglect

of a phenomenon that illustrates that transmitted nature very well, viz. the

emergence of metaphor through deliteralization, i.e. the construction of a metaphorical interpretation for an item whose literal motivation has waned.

1 Introduction

The modest purpose of this short paper is to formulate a gentle reminder about

a few features that Cognitive Linguistics attributes to meaning, and that have

important (but perhaps slightly underestimated) consequences for diachronic

metaphor research. The points whose consequences I would like to explore

Dirk Geeraerts: University of Leuven

16

Dirk Geeraerts

are the following: first, that meaning is prototypically structured; second, that

meaning is structured both semasiologically and onomasiologically; third, that

meaning is embodied in both natural and cultural experience, and fourth, that

meaning is transmitted through language. Because these points are either selfevident (like the final one), or deeply entrenched in Cognitive Linguistic thinking (like the other three), I do not think it is necessary to present them in more

detail here. The consequences of these issues for diachronic metaphor research

are however far-reaching, and they are not necessarily universally recognized.

In the following pages, I will illustrate the impact of the four principles on

diachronic metaphor research, and refer to the neglect of those principles –

with a certain degree of rhetorical hyperbole – as four ‘fallacies’. (The illustrations will predominantly come from studies that I published elsewhere over

the last twenty years, supplemented with a few cases involving original materials. This inevitably entails that my own work will be disproportionately present

in the bibliographical section of the paper. To be sure, this is not meant to

diminish the value of other authors’ work. For a more balanced account of

recent work in historical cognitive semantics, see Geeraerts 2010.)

2 The ‘dominant reading only’ fallacy

The fact that meaning is prototypically structured implies that the prototypical

semantic development of words needs to be taken into account when establishing the presence of a metaphor of a certain type (see Geeraerts 1997 for an

extensive treatment of prototype effects in diachronic semantics). In a target

is source pattern, the meaning that is selected as the Source is very often

taken to be the currently dominant literal reading, but that is not necessarily

historically correct. To achieve a historically adequate picture of the emergence

of a metaphor, the birth of the metaphor needs to be checked against the individual word histories of the expression in question: the meaning of the Source

item that provides the historical basis for the metaphorical expression may be

a different one than the most readily available candidates.

A straightforward example may be found in the following use of the word

antenna. The following quotation is taken from a web version of How to Turn

your Ability into Cash by “master salesman and successful author” Earl Prevette.

There are three separate Departments of the Mind which deal with ideas. The function of

these Three Departments of the Mind bears a striking similarity to the three Departments

of the Government. First: The Emotion is the Legislative Department of the Mind. The

Four guidelines for diachronic metaphor research

17

Emotion is the antenna of the Mind radiating and emitting thoughts into space, and also

receiving them from space (…) Second: The Judgment is the Judicial Department of the

Mind. (…) Third: The Desire is the Executive Department of the Mind. (…)

The metaphor emotion is the antenna of the mind is echoed by other expressions. In a web text by the Rev. Tim Dean, chaplain of the Cayuga Medical

Center, we note that feelings are like the antennae of the soul, and in the internet document A Rhetoric of Objects, Jonathan Price mentions that attention is

the antenna of the soul. Further examples that can be found googling for the

combination sensitive antenna include the following:

Artists are like sensitive antenna and pick up on things in the culture

I don’t know, I thought it was fine and I have a pretty sensitive antenna for that type of

stuff

With my sensitive antenna to sense the vibes from different people, I subconsciously tried

to act and speak in a way to prove myself

What I am referring to are the early stages of panic that my sensitive antenna are picking

up

Correct me if I’m wrong, but if there’s no sex in your life, then my sensitive antennae are

telling me that you’re either resting or else you’re recovering from a broken relationship

Up till now, for the sake of old times, when I cared less about what my sensitive antennas

told me, I decided to remain acquainted with these people with devastating effects

Applying the standard argumentative format of Conceptual Metaphor Theory,

examples such as these could readily lead to postulating a metaphor sensitivity is an aerial, or more broadly, human communication is a radio device.

Beyond the word antenna, this pattern would seem to be supported by expressions like we are on the same wavelength, he couldn’t tune in to her reasoning,

there is a lot of noise on our communication, they have to fine-tune their interaction, I am getting your point loud and clear, are we using the same frequency.

However, the presence of the plural antennae in the examples invites a

closer look at the semantics of antenna: next to the dominant ‘aerial’ reading

(for which antennas is the regular plural), the interpretation ‘feeler of an animal’ occurs, with the plural antennae. But while the ‘feeler’ reading is synchronically the secondary meaning, it is diachronically primary: the ‘feeler’ reading

occurs in English since the 17th century, when it is introduced as a loan from

Latin; the radio antenna, on the other hand, was only invented by Marconi in

the first years of the 20th century. The question then arises whether the associa-

18

Dirk Geeraerts

tion between emotional sensitivity and antenna might not also be older than

the sensitivity is an aerial metaphorical pattern assumes. And indeed, the

OED includes the following relevant quotations for the figurative interpretation

of the ‘feelers’ reading:

O. W. Holmes, Poems 214 1855 “Go to yon tower, where busy science plies Her vast antennae, feeling thro’ the skies”

E. Pound, Pavannes and Divisions 43, 1918 “My soul’s antennae are prey to such perturbations”

Listener 17 Dec. 1959 1082/1 “This is where an author with sound learning, a seeing eye,

and sensitive ‘antennae’ can be of great assistance

The first example predates the invention of the radio antenna, while the other

two belong here on the basis of the plural form. The metaphorical pattern understanding is a tactile event that may be associated with the expression

is further illustrated by words like feeling, to feel, to touch, to grasp, to get (a

point).

It follows that the examples cited earlier for a pattern sensitivity is an

aerial, or more schematically, human communication is a radio device

need to be revisited, and that, in fact, at least some of the examples would

rather illustrate understanding is a tactile event than human communication is a radio device. How to decide between the competing interpretations

will not always be a straightforward matter. References to immaterial signals

(like ‘waves’ or ‘vibes’) point towards the ‘radio’ interpretation, whereas the

use of the plural (specifically in the form antennae) points towards the ‘feelers’

interpretation. Indications such as these do not necessarily decide the issue,

though, because the individual quotations do not always contain such indices,

and moreover, the indices themselves may be indecisive. The utterance artists

are like sensitive antenna and pick up on things in the culture suggests, for instance, that antenna also appears as a plural: should we then assume that

other instances of antenna may also be plurals, and that those plurals suggest

a ‘feeler’ pattern?

The fundamental point to be made here is not so much the difficulty of

deciding between the two interpretations, but the fact that a look at the history

of the word antenna reveals the very existence of those interpretations. Antenna goes through a process of semantic change in which the original ‘feeler’

meaning gives rise, by a cognitive process based on visual and functional similarity, to the ‘aerial’ meaning. To be precise, this semantic shift primarily occurs in Italian, when Marconi adopted the term antenna for the new invention.

In English, the radio antenna is a loan from Italian while the feeler antenna

Four guidelines for diachronic metaphor research

19

has a Latin origin. As such, the relationship in English is primarily homonymic,

even though the semantic relationship between the two words will not go unnoticed for most speakers. Crucially for the argument that I am developing,

both meanings of antenna go through a process of metaphorization targeting

the domain of communicative sensitivity – but if the specific history of antenna

were not taken into consideration, the metaphorical ambiguity of an expression like my soul’s antenna would remain hidden.

3 The ‘semasiology only’ fallacy

The fact that meaning is structured both semasiologically and onomasiologically implies that both the semasiological and the onomasiological perspectives need to be taken into account when studying historical metaphorical patterns, i.e. establishing the importance of a target is source pattern is often

done by merely charting the presence of Target in the semasiological range of

Source, without checking the importance of Source in the onomasiological

range of Target. This may hugely overestimate the importance of the pattern

for the conceptualization of the target. Schematically, the relevant perspectives

are presented in Table 1.

Tab. 1: Semasiological and onomasiological perspectives.

semasiology of Source

onomasiology of Target

target is source

target is not-source

not-target is source

The dominant perspective in Conceptual Metaphor Theory is to look at the data

along the horizontal dimension of Table 1: starting from the Source expression,

it is established that target is source plays a significant role in the semasiological range of Source next to not-target is source, just like in the previous

paragraph, for instance, we noted that the target domain of communicative

sensitivity appears in the semasiological range of antenna. But how important

that presence is for the conceptualization of communicative sensitivity cannot

be established by only looking at the semasiology of Source: what one would

really like to know is the importance of the pattern in the onomasiology of

the Target, i.e. if we look along the vertical dimension of Table 1, what other

conceptualizations of the Target do we find, and how strongly is target is

20

Dirk Geeraerts

source represented within that onomasiological range, in comparison to target is not-source?

A concrete example of such a way of thinking is found in Geeraerts and

Gevaert (2008). When we compare anger is heat (a cherished metaphorical

pattern in Conceptual Metaphor Theory) to other expressions for anger in Old

English, it turns out that the literal expressions dominate, and that anger is

heat takes up only a minority position in the onomasiological range of anger.

In Table 2, the most common Old English expressions are listed according to

the conceptual theme that they illustrate. A specification of the semantic process behind the name, together with the frequency with which it occurs in the

data (covering all available Old English sources) makes clear that metaphorical

naming is proportionately not in the majority, and that an anger is heat metaphor in particular is marginal.

Tab. 2: Old English expressions of anger.

Theme

Expressions

semantics

nº

wrong emotion

fierce

insane

strong emotion

unmild

ire

gram, wrað

ellenwod

anda

unmiltse

literal

literal or hyperonymy

literal or hyperonymy

hyperonymy

hyperonymy

46

15

1

2

1

65

affliction

sadness

swelling

synaesthesia

fierce

heat

torn, sare

unblide, gealgmode

belgan

sweorcan, biter, hefig

reðe

hatheort, hygewaelm

metonymy

metonymy

metaphor

metaphor

metaphor

metaphor

11

3

33

3

4

2

56

4 The ‘natural experience only’ fallacy

The fact that meaning is embodied in natural and cultural experience implies

that diachronic metaphor theory needs to take into account the cultural background of experience just as well as it physiological basis, i.e. diachronic metaphor theory should take into account the history of ideas, and the history of

daily life (the point has been made before, see for instance Pagán Cánovas

2011). Because there are various aspects to this broader background, a number

of illustrations may be mentioned here.

First, it was pointed out in Geeraerts and Grondelaers (1995; an article that

was influential in bringing about the ‘cultural turn’ of Conceptual Metaphor

Four guidelines for diachronic metaphor research

21

Theory described in Kövecses 2005) that the scientific conceptions of a given

age – or more broadly, the scientific traditions of a given culture – may have

an influence on the vocabulary of the common language. Specifically, we

pointed out that there is plenty of evidence for the impact of the humoural

theory of human physiology and psychology on natural language, as in the

expressions brought together in Table 3. For each of the four basic physiological fluids that constitute the humoural theory, the table shows how it has left

relics – with meanings in the physiological or the psychological domain – in

English, French, and Dutch.

Tab. 3: Impact of the humoural theory on natural languages.

english

french

dutch

phlegm

phlegmatic

‘calm, cool, apathetic’

avoir un flegme

imperturbable

‘to be imperturbable’

valling

(dialectal) ‘cold’

black

bile

spleen ‘organ filtering

the blood; sadness’

mélancolie

‘sadness, moroseness’

zwartgallig ‘sad,

depressed’

(literally ‘black-bilious’)

yellow

bile

bilious

‘angry, irascible’

colère

‘anger’

z’n gal spuwen ‘to vent

(literally ‘to spit out’) one’s

gall’

blood

full-blooded

‘vigorous, hearty,

sensual’

avoir du sang dans les

veines ‘to have spirit,

pluck’

warmbloedig ‘passionate’

(literally ‘warm-blooded’)

We then argued that the anger is heat metaphor could also be part of that

humoural legacy. Rather than being directly motivated by universal physiological phenomena, as was initially suggested by Lakoff and Kövecses, the anger

is heat metaphor (or more precisely the anger is the heat of a fluid in a

container metaphor as identifed by Lakoff and Kövecses) fits into the humoural framework. An analysis of anger expressions in literary texts like

Shakespeare’s The Taming of the Shrew supports such an analysis.

In the present context, the crucial feature of this story is the necessity of

incorporating the history of ideas into the analysis of metaphorical expressions. Regardless of whether the anger is the heat of a fluid in a container

metaphor is exclusively based on the humoural theory or whether it is a combination of the humoural theory and a physiological impulse, a proper understanding of conceptual metaphors implies an awareness of the cultural and

scientific traditions that may have influenced the language.

22

Dirk Geeraerts

Two points may be added to this general idea. To begin with, the historical

influences are not restricted to the history of ideas: the history of the material

culture may also leave its marks. One may notice, for instance, how successive

technological (and not just scientific) developments provide source domains

for conceptualizing human psychology. Taking our examples from Dutch (in

most of the following expressions, the English translation exhibits the same

figurative polysemy as the Dutch original), we identify the influence of clocks

in expressions like opgewonden ‘excited’ (literally ‘wound up’), van slag zijn

‘be off one’s stroke’, drijfveer ‘mainspring’, afgelopen ‘wound down’. Steam

engines have left their mark in stoom afblazen ‘to let of steam’, klaarstomen

‘to steam up, to make ready’, druk ‘pressure’, and onder stoom staan ‘to be

steamed up’. Radio provides a source domain in op dezelfde golflengte zitten

‘to be on the same wavelength’, onderling afstemmen ‘to tune in to each other’,

ruis ‘noise’ stoorzender ‘jammer; (hence figuratively) nuisance’ – and of course,

antenna. Simply stating that these expressions illustrate a general the mind is

a machine metaphor is not giving them their due: each technological source

provides perspectives that seem to be specifically suited for conceptualizing

specific target domains, or specific aspects of target domains. The radio metaphors favour a communicative target domain. The steam engine metaphors

highlight power and pressure. The clock metaphors focus on precision and

smooth operation. Moving beyond the schematic level of the mind is a machine and analyzing this specificity of the metaphorical expressions is an integral part of Conceptual Metaphor Theory, but it requires two things: a systematic analysis of the ground of the metaphor in the sense of Richards (1936), i.e.

the quality that motivates the use of a source (‘vehicle’ in Richards’ terminology) for a specific target (‘Tenor’ according to Richards), and a sensitivity for

the history of the material culture that constitutes a part of the environment of

a language.

A second point to be added involves the possibility of cultural changes of

a more far-reaching, but at the same time less tractable nature than the

changes in the immaterial and material context that we have illustrated by the

humoural theory, and the technological domains of clocks, steam engines, and

radiography. Cultural history distinguishes between major periods of development in which not just the material culture or the political and economical

circumstances evolve, but in which people’s outlook on life, in a broad and

vague sense, change pervasively. For the history of the West, the succession

from classical antiquity to the middle ages and then to the renaissance and the

modern world is a case in point. To the extent that these shifts are real, we

may expect them to have a bearing on the semantic changes, metaphorical and

other, that the vocabulary of a language undergoes in a certain period. This is

Four guidelines for diachronic metaphor research

23

not an issue that is very systematically investigated, but if we stay in the domain of emotion terms, the following two examples may briefly illustrate the

point.

Diller (1994) suggested that the Middle English emergence of the word anger, as against older ire and wrath, signals a sociohistorical shift towards the

individualization of the emotion – precisely the kind of shift, in other words,

that would correspond with a transition towards the individual self-awareness

that is traditionally attributed to the post-medieval period. Diller’s hypothesis

was tested by means of a quantitative corpus-based analysis in Geeraerts, Gevaert and Speelman (2012). The results of the quantitative analysis support Diller’s hypothesis.

For a second example we turn to the word emotion iself, or more precisely

to the French verb émouvoir from which it derives. Geeraerts (2014) presents

evidence, based on Bloem (2008), that the psychological interpretation of

émouvoir (and, in fact, its near-synonym mouvoir) may have come about in the

context of the theory of humours. When the psychological reading enters Old

French, it does so indiscriminately in the verb émouvoir and in the verb mouvoir. For both verbs, the psychological reading seems to be a literal expression

in the context of the theory of humours, referring to the movement of the humours in the body and their psychological side-effects. Without going into detail, an example like the following may illustrate the kind of bridging contexts

in which the psychological reading emerges:

Le roy demande: Felonnie de quoi avient? Sydrac respont: Des humeurs mauvaises qui

aucune fois reflambent au cors comme le feu, et esmuevent le cuer et eschaufent, et le

font par leur reflambement noir et obscur; et por cele obscurté devient mornes et penssis

et melanconieus.

‘The king asks: Where does felony come from? Sydrac replies: From the bad humours

that at one point start burning in the body like fire, and that move the heart and heat it,

and make it dark and black by their burning; and from this darkness it becomes sad and

thoughtful and melancholy’

The movement in this example is primarily literal: the humours that fill the

heart are agitated and heated, but this literal process has outspoken psychological side-effects. It can be shown that in the Old French period, both émouvoir and mouvoir exhibit the same range of readings: purely spatial ones, purely psychological ones, and bridging ones like in the example.

But in the course of time, this equivalence of the two verbs gives way to

the current specialization, in which émouvoir is restricted to the psychological

readings. Why there should be such a growing differentiation of both verbs is

difficult to answer definitively, but it is not implausible that cultural history

24

Dirk Geeraerts

played a role. A structural explanation might refer to a principle of isomorphic

efficiency, which in this case would imply a ban on superfluous synonymy. The

general validity of such a principle is however debatable: see the discussion in

Geeraerts (1997: 123–156). A functional explanation, by contrast, could assume

that there is a diachronically growing need for concepts referring exclusively

to psychological phenomena, i.e. for words that provide an independent lexicalization for individual mental experiences like feelings (and the generic notion of ‘feeling’). In the terminology of Geeraerts, Grondelaers and Bakema

(1994), the conceptual onomasiological salience or ‘entrenchment’ of a concept

rises to the extent that the things that could possibly be identified by that

concept are actually being identified by it. The rise, then, of a specialized,

dedicated term for the concept ‘to feel, in a psychological sense’ can be seen

as a structural analogy of growing conceptual onomasiological salience. The

growing entrenchment of a concept is reflected, on the level of usage, in the

increased frequency of words exclusively referring to that concept, and on the

level of vocabulary structure, in the emergence of words specialized for that

concept.

The growing structural independence of the concept of emotion is also reflected in the word émotion itself, which is added much later to the vocabulary

than the verb émouvoir, but whose appearance as such contributes to the growing entrenchment of the concept of emotion in the structure of the lexicon. In

addition, since its emergence in the late 15th century émotion enjoys a growing

success at the expense of the verb (see also Bloem 2012). In the context of

Cognitive Linguistics, the heightened nominal rather than verbal construal

could again be seen as signalling the strengthened recognition of emotion as

a thing in its own right.

In short, the diachronic differentiation of mouvoir and émouvoir (and

hence, émotion) seems to fit into a longitudinal cultural development towards

psychologization and interiorization of mental life, similar to Diller’s hypothesis about the success of anger in contrast with older terms. The need for a

dedicated term for the emotions, as inner mental experiences, increases; or, to

put it in a slightly different terminology, the conceptual onomasiological salience of émouvoir and émotion in their psychological reading rises.

5 The ‘metaphorization only’ fallacy

The fact that meaning is transmitted through language implies metaphors do

not just arise through original metaphorization, but that they may also arise

Four guidelines for diachronic metaphor research

25

through a ‘deliteralizing’ reinterpretation process: while a new target is

source pattern is usually formed by figuratively categorizing the Target as

Source, it may also happen that an existing literal categorization is reinterpreted as a figurative target is source pattern, because the literal motivation of

the original expression is no longer accessible.

The concept ‘emotion’ provides an example of the process. (Again, see

Geeraerts 2014 for more details.) Let us assume that French émotion or English

emotion are currently perceived as metaphorically linked to the concept of

movement. This will not generally be the case. For many language users, the

words may well be basically opaque. But at least in some cases, a metaphorical

association with the concept of movement is envisaged. The Oxford English

Dictionary, for instance, explains the reading ‘any strong mental or instinctive

feeling, as pleasure, grief, hope, fear, etc.’ as an extension of a reading ‘an

agitation of mind; an excited mental state’, which itself seems to be analyzed

as a metaphorical interpretation of the general literal meaning ‘movement; disturbance, perturbation’. Now, if people indeed perceive such a metaphorical

link, and if we further assume that the original historical motivation for the

emergence of the term involves the humoural theory, then the metaphorical

interpretation comes about in a different way from what we normally consider

to be the process of metaphorical speech.

In fact, in the regular type of creative metaphor, an expression with reference A and sense α is applied with reference B and with an extended, figurative

sense α′. Surely, this is a simplified picture of the relationship between α and

α′ (very often, the precise nature of α′ is not as easy to determine as this simple

variable suggests), but it helps to contrast the regular form of metaphor with

reinterpretive deliteralization. In the latter, an expression with reference A and

sense α is interpreted with the same reference A but with an extended, figurative sense α′. Comparing two examples may bring out the differences more

clearly. A lover who addresses his beloved as sparkles triggers the implication

that he sees her as lively, dynamic, vigorous and invigorating. In this kind of

metaphor, which may be said to be based on ‘figuration’, the reference of sparkles shifts from small burning fragments and glittering points of lights to a

person; at the same time, the sense of the word shifts from the material or

optical field to a psychological one: the beloved person does not literally sparkle. The shift occurs, by and large, because there is a unique and forceful experience that calls for a singular and pithy expression. In comparison, thinking

that emotion is a non-literal kind of motion does not change the reference of

emotion, but merely reinterprets the link between the word and its referent.

This reinterpretation is triggered by the fact that the original, literal motivation

for the word is no longer available. In that sense we can say (with a little

26

Dirk Geeraerts

exaggeration) that metaphor based on figuration involves making sense of the

world – ‘what is this overwhelming experience that she invokes in me, and

how shall I call it?’ – whereas metaphor based on deliteralization involves

making sense of the language – ‘why is this thing called as it is?’.

In the larger scheme of things, deliteralization as defined here is part of

a broad class of reinterpretation processes in which existing expressions are

semantically reinterpreted when the original motivation of the expression is

no longer available to the language user. Further examples (specifically in the

field of idiomatic expressions and compound nouns) can be found in Geeraerts

(2002). Deliteralization is a prime example of the integrated nature of culture

and cognition in the realm of language: language users do not invent language

from scratch, but they receive it as part of their cultural environment; at the

same time, they cognitively process what is relayed to them, and that mental

absorption may imply a partial reinvention of what is being reproduced. The

relationship between culture and cognition is a dialectic one: language is a

culturally transmitted and hence intrinsically historical phenomenon, but at

each point in time, the transmission process requires cognitive reproduction.

6 Conclusions

To summarize and conclude, I have argued that there are four fallacies to avoid

in diachronic metaphor research in Cognitive Linguistics: the dominant reading

only fallacy, which neglects to have a closer look at the history of words; the

semasiology only fallacy, which neglects the relevance of the onomasiological

alternatives for Target; the natural experience only fallacy, which neglects the

cultural background of cognitive processes; and the metaphorization only

fallacy, which neglects processes of deliteralization and reinterpretation as

sources of metaphoricity. Each of these points derives from a tenet taken for

granted in Cognitive Linguistics: respectively, that meaning is prototypically

structured; that meaning is structured both semasiologically and onomasiologically; that meaning is embodied in both natural and cultural experience; that

meaning is transmitted through language. Beyond these specific backgrounds,

the common denominator behind the identification of the four fallacies is the

obvious recognition (perhaps so obvious that it tends to be forgotten) that historical metaphor research needs to take the historicity of language as its main

starting-point.

Four guidelines for diachronic metaphor research

27

References

Bloem, Annelies. 2008. Et pource dit ausy Ipocras que u prin tans les melancolies se

esmoeuvent. L’évolution sémantico-syntaxique des verbes ‘mouvoir’ et ‘émouvoir’.

Leuven: Katholieke Universiteit Leuven dissertation.

Bloem, Annelies. 2012. (E)motion in the XVIIth century. A closer look at the changing

semantics of the French verbs émouvoir and mouvoir. In Ad Foolen, Ulrike M. Lüdtke,

Timothy P. Racine & Jordan Zlatev (eds.), Moving ourselves, moving others: Motion and

emotion in intersubjectivity, consciousness and language, 407–422. Amsterdam &

Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

Diller, Hans-Jürgen. 1994. Emotions in the English lexicon: A historical study of a lexical

field. In Francisco Moreno Fernández, Miguel Fuster & Juan Jose Calvo (eds.), English

historical linguistics 1992, 219–234. Amsterdam & Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

Geeraerts, Dirk. 1997. Diachronic prototype semantics. A contribution to historical lexicology.

Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Geeraerts, Dirk. 2002. The interaction of metaphor and metonymy in composite expressions.

In René Dirven & Ralf Pörings (eds.), Metaphor and metonymy in comparison and

contrast, 435–465. Berlin & New York: Mouton de Gruyter.

Geeraerts, Dirk. 2010. Prospects for the past: Perspectives for diachronic cognitive

semantics. In Margaret E. Winters, Heli Tissari & Kathryn Allan (eds.), Historical

cognitive linguistics, 333–356. Berlin & New York: Mouton de Gruyter.

Geeraerts, Dirk. 2014. Deliteralization and the birth of ‘emotion’. In Masataka Yamaguchi,

Dennis Tay & Ben Blount (eds.), Approaches to language, culture, and cognition. The

intersection of cognitive linguistics and linguistic anthropology, 50–67. London:

Palgrave MacMillan.

Geeraerts, Dirk & Caroline Gevaert. 2008. Hearts and (angry) minds in Old English. In Farzad

Sharifian, René Dirven, Ning Yu & Susanne Niemeier (eds.), Culture and language:

Looking for the mind inside the body, 319–347. Berlin & New York: Mouton de Gruyter.

Geeraerts, Dirk, Caroline Gevaert & Dirk Speelman. 2012. How ‘anger’ rose. Hypothesis

testing in diachronic semantics. In Kathryn Allan & Justyna Robinson (eds.), Current

methods in historical semantics, 109–132. Berlin & New York: Mouton de Gruyter.

Geeraerts, Dirk & Stefan Grondelaers. 1995. Looking back at anger: Cultural traditions and

metaphorical patterns. In John Taylor & Robert E. MacLaury (eds.), Language and the

construal of the world, 153–180. Berlin & New York: Mouton de Gruyter.

Geeraerts, Dirk, Stefan Grondelaers & Peter Bakema. 1994. The structure of lexical variation.

Meaning, naming, and context. Berlin & New York: Mouton de Gruyter.

Kövecses, Zoltán. 2005. Metaphor in culture. Universality and variation. Oxford: Oxford

University Press.

Pagán Cánovas, Cristobal. 2011. The genesis of the arrows of love: Diachronic conceptual

integration in Greek mythology. American Journal of Philology 132. 553–579.

Richards, Ivor A. 1936. The philosophy of rhetoric. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Conceptual variation and change

Kathryn Allan

Lost in transmission? The sense

development of borrowed metaphor

Abstract: Both metaphor and borrowing are generally acknowledged to be key

processes in the enrichment of the English lexicon: metaphor is recognised as

a trigger for the development of polysemy, and borrowing has been, and continues to be, a major source of new lexis. This paper considers the effects when

these two processes coincide, when metaphorical sense developments are borrowed across language boundaries. As a starting point, it focuses on “dead” or

“historical” metaphors in English which were “alive” in the donor language at

the time of borrowing. Many of the examples of “dead” or “historical” metaphor that have been identified in the literature are lexemes that were borrowed

into English. For example, the noun pedigree was borrowed into Middle English from Anglo-French pé de grue ‘foot of a crane, pedigree’, but only seems

to be recorded in English with its “metaphorical” sense; the metaphor that

existed in French is therefore opaque for most monolingual English speakers.

ardent was also borrowed into English in the Middle English period, and might

be expected to be more likely to retain its metaphorical polysemy, since it relates to a conceptual metaphor which is still found in English, intensity (in

emotion) is heat. Although both the literal sense ‘burning’ and figurative

senses including ‘passionate’ are attested in English, the literal sense is archaic

or obsolete in Present Day English, and evidence from resources such as the

Middle English Dictionary and Early English Books Online suggests that it appears to be rare even in earlier periods. Where it is found in earlier documents,

the ‘burning’ sense appears to be restricted to particular text types and contexts. Again, the historically metaphorical motivation for the meaning ‘passionate’ is not obvious to contemporary speakers unless they are familiar with

the French or Latin etymons of the lexeme. The role of borrowing in the semantic development of non-native lexemes has been discussed by various scholars.

For example, Durkin (2009) notes that borrowing sometimes only involves a

component of the meaning of the donor form, and discusses later borrowing of

additional senses from the donor language; in his classic account of language

contact, Weinreich (1964) also discusses the impact of borrowing on the existing lexis of a language. However, the significance of borrowing in the histories

of metaphors has not been considered in detail. This paper explores what the

Kathryn Allan: University College London

32

Kathryn Allan

implications of borrowing are for diachronic metaphor studies, and for the

term “metaphor” itself.

1 Introduction

Both metaphor and borrowing are generally acknowledged to be key processes

in the enrichment of the English lexicon. Metaphor is recognised as a trigger

for the development of polysemy, and is often listed as one of the best-attested

tendencies in semantic change: for example, Ullmann includes metaphor as a

one of four “cardinal types” of association “such as have proved their strength

by initiating semantic changes” (Ullmann 1959: 79), and Traugott and Dasher

note that “For most of the twentieth century metaphor(ization) was considered

the major factor in semantic change” (Traugott and Dasher 2004: 28). Some

linguistic metaphors are “alive” to contemporary speakers, in the sense that

they are expressed by lexemes with both “literal” source senses and “metaphorical” target senses; others are “dead” or “historical” in that no corresponding “literal” sense is used (see for example Deignan 2005: 40). For some scholars, these cannot be considered metaphors, but from a historical point of view

their metaphorical motivation is interesting and significant. Borrowing also

has a major impact on the lexicon, as a major source of new vocabulary. It is

generally accepted that modern English is a “lexical mosaic” (Katamba 2005:

135) which reflects a great deal of borrowing in earlier periods, especially from

French and Latin in the period after the Norman Conquest. Core vocabulary has

been the least affected, although it still seems to show considerable influence;

borrowing has changed the shape of other areas of the lexicon, such as scientific vocabulary and many technical registers, even more dramatically. Scheler

(1977: 72) examines the proportion of loanwords in the lexis of English, using

a variety of sources1. In a basic list which concentrates on core vocabulary, he

finds that approximately 50 % of items are borrowed. His figure for a longer

list composed of data from a learner’s dictionary is higher at approaching 70 %,

and in a very large wordlist derived ultimately from the Oxford English Dictionary (OED) the total of loanwords reaches 70 %, with 56 % derived from French

and Latin (although this list omits many rarer and obsolete words).

1 See Durkin (2014: 22–24) for a longer discussion and updated figures based on revised material in OED3.

Lost in transmission? The sense development of borrowed metaphor

33

This paper considers the effects when borrowing and metaphor coincide,

i.e. when metaphorical sense developments are borrowed across language

boundaries along with the lexemes that express them. As a starting point, it

focuses on “dead” or “historical” metaphors in English which were “alive” in

the donor language at the time of borrowing. It considers what happened to

the senses of a number of loanwords in their early histories in English, and

how their etymologically “metaphorical” senses were lost. Two case studies

will be presented: first, I will consider the verb inculcate, which is discussed

by Goatly as an example of “dead and buried metaphor” (Goatly 2011: 32), and

secondly, I will look in detail at the adjective ardent, also mentioned in the

literature on historical metaphor (Deignan 2005: 39; see also Steen 2007: 95–

96). The central question addressed in the paper is whether the process of borrowing itself is likely to result in metaphor “death”: is it usual for both senses

of a linguistic metaphor to be borrowed, and then for the “literal sense” to die

out within the target language, or is it more likely that the metaphor will be

“lost in transmission”?

2 Borrowed metaphor

In the literature on metaphor within cognitive linguistics, borrowing is rarely

mentioned; metaphorical sense developments within a language are much

more common as a focus of study. Where the etymologies of borrowed lexemes

with metaphorical senses are discussed, there is usually little consideration of

which senses in the donor language are borrowed along with the word form.

A typical example can be found in an article on ‘Metaphors in English, French,

and Spanish Medical Written Discourse’, which gives muscle as an instance of

metaphor and briefly details its etymology:

A frequently cited example [of metaphor] is ‘muscle’ (from the Latin word musculus,

which means ‘small mouse’). In this metaphor, ‘muscle’ is the Topic, ‘small mouse’ is the

Vehicle … (Divasson and Léon 2005: 58)

While it does acknowledge the history of the English lexeme, this kind of comment blurs the distinction between the forms that appear in different languages and their meanings. In this example, it is not clear in which language

the linguistic metaphor is “alive”: there is no information about whether the

Latin term musculus means both ‘little mouse’ and ‘muscle’, or whether the

loanword muscle has both senses in English (or had these senses in an earlier

period), or both. A closer look at the history of muscle in OED3 shows that the

34

Kathryn Allan

sense ‘little mouse’ is not recorded (or at least, not frequently enough to be

included in the entry); muscle is only found in English with the sense ‘part of

the body’ and related meanings, such as ‘physical strength’, ‘power’ (e.g. of a

machine) and ‘Threat of physical violence’. The entry also shows that muscle

should not be regarded as a loanword borrowed solely from Latin; Middle

French muscle, muscule is presented as a co-etymon of Latin musculus, indicating that both languages are likely to have influenced the establishment of the

English lexeme and its semantic (and formal) development. The Trésor de la

Langue Française Informatisé (TLFi) and the Dictionnaire du Moyen Français

give more information about the senses of muscle in Middle French, and the

account it presents suggests that it was not used with the sense ‘mouse’ or

any related senses; the metaphor only existed linguistically in Latin, and the

etymologically “literal” sense was not transmitted to French or English.

My intention here is not to single out Divasson and Léon’s paper for criticism, since their focus is not historical. Their interest is in current lexemes

in the medical terminology of different languages which evidence the same

metaphorical mapping, and they give this example only to explain the different

constituent parts of a metaphor and the kind of relationship these have. However, their comment is representative of the lack of attention that has been

given to the issue of borrowing and its central importance in the lexical history

of metaphorically motivated lexemes in English (and other languages). Traugott draws attention to borrowing in a 1985 paper which examines the metaphorical origins of a set of lexemes including illocutionary verbs, and notes

that the “metaphoricity” of loanwords in the borrowing language should not

be taken for granted.