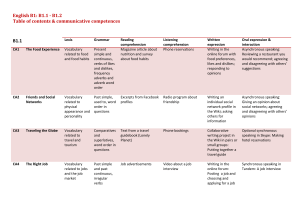

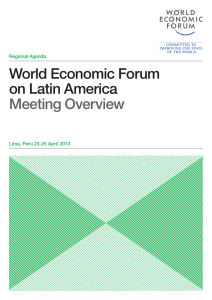

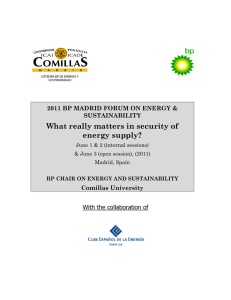

The Strategic Forum: aligning objectives, strategy and process Barry Richmonda Barry Richmond is managing director of High Performance Systems, Inc., where he is responsible for the overall strategic direction of the company as well as for stewarding product and service development. Abstract Most organizations do a good job of establishing strategic objectives and of crafting a strategy that is designed to achieve these objectives. However, the question of whether the strategy, even if successfully implemented, can in fact yield the espoused objectives is rarely entertained. And, even when it is entertained, the processes that are employed for answering the question leave much to be desired. The Strategic Forum engages a senior management team in a rigorous process designed to align strategy and business processes with stated objectives. Senior management teams emerge from a Strategic Forum with a clearer operational picture of how their business works and with a greater sense of what is needed to ensure an ongoing internal consistency among objectives, strategy, and business processes. © 1997 by John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Syst. Dyn. Rev. 13, 131–148, 1997 (No. of Figures: 3 No. of Tables: 2 No. of Refs: 0) An important, unmet business need We want to be a $5 billion company by the year 2000. We plan to get there by aggressive expansion of our direct sales force and simultaneous bolstering of our indirect sales force (OEMs, VARS and VADs). With some modification of numbers and timing, the preceding quotation is a brief but accurate summary of a major American company’s strategic objective and strategic plan. Although objectives, strategies and processes differ in substance, most organizations develop similar statements to express where they want to go and how they plan to get there. Developing such statements, and engaging in the strategic discussions which produce them, is good management practice. However, when the process at work in several companies has been examined, an important question arises: How does a management team actually go about determining whether the strategy and associated processes are feasible, i.e., can they in fact yield the stated objective? It is important to recognize that this question is not the same as: “Will the objective be achieved?” Rather, it is equivalent to: “Can the objective be achieved?” The difference between the two questions is critical. Whether the objective will be achieved, depends on a large number of factors — many of which lie beyond management’s control. These include such things as competitor initiatives, changes in government regulations, the performance of the macroeconomy, technological advances and shifts in consumer preferences. By contrast, the question of whether a High Performance Systems, 45 Lyme Road, Suite 300, Hanover NH 03755, U.S.A System Dynamics Review Vol. 13, No. 2, (Summer 1997): 131–148 © 1997 by John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. CCC 0883-7066/97/020131–18 $17.50 Received October 1996 Accepted January 1997 131 132 System Dynamics Review Volume 13 Number 2 Summer 1997 the objective can be achieved has to do with whether the objective(s), strategy, and processes form an internally consistent set. The operative question here is: “Given that all of the assumptions about the non-controllables hold true, will successful execution of the strategy yield performance which matches the stated objectives?” Too frequently, this question is not asked. And that is because the need to ensure such an internal consistency is rarely recognized. But even when the question is asked, the process for answering it is woefully inadequate, which points to the need for a process like the Strategic Forum. The current method for ensuring that execution of strategy through current processes will yield stated objectives typically consists of a series of crossfunctional discussions supported by various number-crunching analyses. A document that states the strategic objective(s), and then outlines the plan for meeting the objective(s), will be comprehensively reviewed. Much work will have gone into the document prior to the initial review session. Then, during the sequence of session(s), each functional representative will lay out an operating plan (how their function will execute through their processes) to show what contribution their function will make toward achievement of the strategic objective(s). After numerous flipchart pages worth of give and take and a thorough review of the resulting “numbers,” action items will be assigned for purposes of nailing down any issues which have surfaced in the discussion. Additional sessions will then be used to process the action items, thereby tying up any loose ends. Ultimately, the management team will bless the overall strategy — issuing a fiat that the objective(s) will be achieved. What remains is then to execute the strategy to ensure that this in fact comes to pass. While neat, useful and consensus-building, there are two critical problems with this approach. First, functional managers do not speak the same language. The day-to-day operating realities of the sales, manufacturing, finance, service HR, marketing and engineering environments are very different. As a consequence, each operating arena has evolved its own dialect and way of looking at the world. Because some common language is needed for communicating across functions, the default choice most often is the language of finance. The associated “technology” is the spreadsheet. This choice makes some sense in that all functions contribute in some way to the “bottom line,” but finance really is only a language for “keeping score.” It is useful for characterizing how well a business is performing (along one important dimension). However, it does not communicate, in operational terms, how the various functions of a business actually work — either in isolation or together. Furthermore, without an operational, cross-functional language, it is difficult for individual members of a management team to fully contribute their function-specific knowledge and expertise to a critical scrutiny of the strategy. Without a true shared understanding (mental map) of how the business works, Richmond: The Strategic Forum 133 many such teams function collectively with a lower “IQ” than any individual member would manifest functioning alone and a major opportunity for synergy goes untapped. A second problem with the current sanity-checking process is that working only with words and whiteboards/flipcharts, it is not possible to check rigorously the connections various team members are intuitively making between process, strategy and resulting performance. There is considerable evidence which shows that humans are not very good at intuiting the dynamic behavior that will be produced by the interaction of even a few simple structural relationships. Although spreadsheets can provide some check on unaided intuition, they in fact impose very little discipline on the process. Spreadsheets make it too easy to conform intuition, bestowing upon wish lists an air of quantitative rigor and “scientific” legitimacy. They permit variables that are interdependent to be treated as independent and they enable (indeed encourage) non-financial relationships to be ignored. The absence of a rigorous process for connecting process and strategy to performance makes it too easy to achieve consensus on a fantasy. Addressing the need: An overview of the Strategic Forum process The Strategic Forum has arisen in response to the need for a more effective process for ensuring the feasibility of a strategy. To date, more than a dozen Strategic Forums have been conducted with companies from a broad variety of industries ranging from high tech to finance and from consumer products to industrial products and non-profit. Although the substance of each Forum has differed, the basic framework and process has remained essentially the same. The Forum session itself is a two-to-three day process, almost always conducted off-site. Attendees are senior managers, typically from across the organization — both functionally and geographically. Teams have ranged in number from two to fifty people, with an average size of about 15–20. The short-term purpose of a Strategic Forum is to enable a cross-functional management team to increase the likelihood that the organization’s strategy and processes can in fact yield its stated performance objectives and to do so in a highly time-efficient manner — building a shared understanding of the business in the process. The longer-term purpose of the Forum process is to build a capacity for systems thinking and for using the operational language of stocks and flows, so that team members can continue to enhance and extend their shared understanding of how the pieces of the business work together as a system. 134 System Dynamics Review Volume 13 Number 2 Summer 1997 Table 1. An overview of the steps in a Strategic Forum Step 1. Step 2. Step Step Step Step Step 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. Step 8. Pre-forum: Phase 1 (Conducted 8–16 weeks prior to Forum). Pre-forum: Phase 2 (Conducted 3–4 weeks prior to Forum). (Steps 3–7 are conducted at the Forum) Setting expectations (1⁄2 hour) ‘‘Big Picture’’ discussion (1–11⁄2 hours) Internal-consistency check exercises (3–6 hours) Strategy design session (3–6 hours) Wrap-up discussion (1–2 hours) (Step 8 is taken after completion of Forum) Follow-up activities The Strategic Forum process Table 1 lays out the steps in a “typical” Strategic Forum process, including an approximate timing and duration for each step. In practice, the sequence of steps is rarely this neat. There is usually some hopping back and forth — particularly between Steps 5 and 6 — and also a good measure of improvisation. In all instances, models are constructed (equations written) and tested, and learning environments are created, in advance of the Forum session. Mapping, and some graphical function specification, is done during the interview sessions held in advance. Occasionally, some modification to the preconstructed models occurs during the Forum. Step 1. Pre-Forum: Phase 1 Well in advance of the scheduled session, the people facilitating the Forum must plan to make several visits to the organization for whom the Forum is being conducted. The visits serve three functions: to gain team members’ confidence, to construct and “validate” maps, and to secure other required “data”. Because the Forum experience is intimate, challenging, and penetrating, it also can be very threatening. As such, it is essential to secure each team member’s confidence in advance of the session. Forum participants must feel comfortable revealing themselves, their ideas, and their information base to the facilitation team. A full discussion of techniques and processes for securing this confidence is beyond the scope of this article. There is no question, however, that establishing a solid rapport is of utmost importance. Success both in the pre-forum steps and during the Forum itself depends upon it. Throughout the course of the subsequent discussion, a few techniques for securing confidence that have proven effective will be discussed. One of the most important of these is demonstrating a solid grasp of the business, and one of the most effective ways to do this is to sketch out a stock/ flow map of a relevant piece of the business and then talk it through, asking for feedback and guidance as you go. Everyone likes to “teach,” particularly about their Richmond: The Strategic Forum 135 Fig. 1. A typical phase 1 “map of the business” piece of the business. Giving each team member (if possible) this opportunity has proven to be a very effective way to secure team member confidence and to build rapport. It also supports the second purpose of the Phase 1 pre-forum visits: constructing and “validating” maps of the business. The maps, translated into a set of computer simulation models, will be used in Steps 5 and 6 — the two steps which constitute the bulk of the activity in the Forum session. The big difference in constructing maps using system dynamics model building and simulation software, as opposed to doing it on a whiteboard or flipchart, is that the former provides a rigorous way to connect structure to dynamic behavior. Without this rigor, the connection can become whatever the team consensus deems it to be. Because the language of stocks and flows will be new to most participants, it is essential to begin exposing them to the basic nouns, verbs and sentence structure of the language as soon as possible. At the same time, it is important for facilitators to get some feedback on the state of their understanding of how the business works. Figure 1 depicts a typical, round-1 map of the overall business. The final purpose of the Phase 1 pre-forum visits is to secure other required “data”. We use the term “data” here in the broadest possible sense. It does mean 136 System Dynamics Review Volume 13 Number 2 Summer 1997 Table 2. Examples of pre-first-interview questions Question 1. Question 2. Question 3. Question 4. What do you consider to be the major challenges facing the organization over the next five years? What are the major constraints, both internal and external, to meeting these challenges? If you could change one thing about the way the organization currently works, what would it be? Repeat questions 1–3 for your piece of the organization. numbers — such as LRP data, annual report data, and data from any special studies that the organization may have recently commissioned — but it also includes information about the formal and informal structure of the organization, major operating policies, important “war stories,” the political situation, heroes and villains within the culture, and current perceptions about constraints, stresses and strains. The most important thing to remember in conducting this activity is to listen very carefully — to what is said and how it is said, and also to what is not said (and by whom). The aim is to try to ferret out any information that may ultimately bear on the operational ability to successfully execute the strategy. At the same time, information is gathered for constructing operational maps of the various pieces of the system, and of the system as a whole. Developing a clear image of people’s current mental models is important if the process is to succeed in having people share these models with each other and also, potentially, in changing these models. To assist in collecting data, we usually send out a brief questionnaire in advance of the first face-to-face meeting. Doing so enables people to feel prepared for, and therefore in more control of, the subsequent interview. An illustrative set of prefirst-interview questions appears as Table 2. These questions are designed to find out what people are feeling, as well as what they are thinking. The former, perhaps not surprisingly, often overshadow the latter in importance at the Forum itself. In advance of the first meeting (if possible), it is important to obtain three other key pieces of data: a vision or mission statement, a statement of strategic objectives, and a summary of the principal function-specific strategies (with associated operating policies) that will be employed to achieve the objectives. These three pieces of information constitute the conceptual infrastructure around which a Forum is built. Reviewing the Phase 1 maps is a primary activity of the second pre-forum visit. The review step is a critical one. The preliminary maps must capture enough of the operating realities to show that the approach that you are taking has potential to “add value.” Yet, they must have enough slack in them so that people can make them their own by adding and tweaking. An indication that the process is on the right track is when people look at a map and say things like: “I’ve never seen the business like this” or “How’d you figure all this out after just one visit?” Then, in Richmond: The Strategic Forum 137 the next breath, they add: “But, you know, you left this out over here.” Such comment pairs suggest that the appropriate balance has been struck to build both credibility and rapport. It is very important not to be defensive about the maps that have been created — no matter how much time has been invested. The intention of creating the preliminary maps is precisely to solicit revision, and, in doing so, to build a feeling of “ownership.” After participants have been exposed to the round-1 maps and feedback collected, it is important to examine carefully the information obtained. Are there any major disagreements or differences in intrerpretation about the basic “plumbing” of the business? It is quite possible that there will be. Often, managers progress up the ladder within a single function. In many companies, the functions are characterized using metaphors such as “silos”, “stove pipes,” or “light houses.” These metaphors are intended to suggest that there is very little communication between the functions, except sometimes at the very top of the organization. Because of such arrangements, many senior managers never develop first-hand knowledge of how functions, other than their own, work. Instead, impressions are at least in part formed by deductions made from observing performance. Since the connection between performance and structure is often difficult to make, it is not uncommon to find some basic gaps in the knowledge bases of Forum participants. It is important to recognize that the gaps of interest, at this point in the process, are “structural,” rather than “behavioral,” in nature. The Forum itself is the arena for addressing gaps in participant knowledge about behavior (i.e., linking strategy and processes to performance). Gaps in knowledge about “structure”, however, must be closed before the Forum. When such gaps do appear, it is important to manage the gap-elimination process with great care. The third Phase 1 visit is often taken up with “gap-elimination” activities. We have given the label “3 in a room” to one of the most effective gap-elimination processes that we employ. In this process, a session is convened involving two people from different functions. The session is not positioned as a “let’s correct your misimpressions” meeting. Rather, it is billed as an opportunity for the facilitation team to clarify some things for themselves about how these two particular functions work. One, or both, of the other people involved can have misimpressions. If only one of the two is misinformed, we team up that person with a player from the function about which they are misinformed. Next, using a round-2 map as a focal point, we have each person explain their piece of the map to a facilitator. Again, in general, people love to “teach.” It feels good to demonstrate knowledge. And, by playing the role of the “learner,” the facilitator not only can learn a lot, but at the same time is also building an effective rapport. In addition, when the facilitator serves as a “learning target,” this creates a “safe” learning environment for the two managers. The “3 in a room” process has proven quite 138 System Dynamics Review Volume 13 Number 2 Summer 1997 effective for eliminating basic knowledge gaps about “structure.” It is essential to detect and fill as many of these gaps as possible prior to convening a Forum. Doing so helps to ensure that each player can fully participate in the Forum process. It also can save someone from what might otherwise be a great personal embarrassment during the Forum session. Step 1 can be considered complete when a high-level map of the overall business, which all Forum participants (if possible) have “signed-off” on, has been created. It also is useful to have several “blow-up” maps of the key pieces of the business in hand. It is not necessary to wait until Step 1 is completed, however, before embarking upon Step 2. Step 2. Pre-Forum: Phase 2 Step 2 can begin once a vision statement, a statement of strategic objectives, and a summary of key functional strategies (with associated operating policies) have been assembled. The principal focus of Step 2 is development of a set of exercises on which participants will work (in small groups) during the Forum session (Step 5). To support these exercises, a progression of computer simulation models must be constructed. The maps developed in Step 1 are usually the departure point for proceeding with this step. The progression of exercises, and associated models, typically “zooms” from the “Big Picture” down into the operating detail associated with specific functions. At the same time as the models become more detailed in structure, they also become more disciplined. This means that they move from being essentially “you can make the system perform almost as you wish” to “there are no free lunches here.” For example, in the case of the company which wishes to grow by expanding its direct sales force, the first model in the progression assumed that the company could hire the volume of sales people that it needed with no unforeseen delays and experience no decrement in average sales productivity or adverse impact on the growth of indirect sales activity. Successive exercises and models systematically removed these “free lunches,” making the company’s strategic objective that much more of a challenge to achieve. Both the type and quantity of exercises that we have employed have varied quite widely. However, each exercise is “discovery-oriented” in nature — which means that participants must work to develop whatever insights they can glean for themselves. In addition, the basic progression of steps within each exercise is essentially the same: “put a stake in the ground,” confront the stake, then discuss and resolve disparities. “Putting a stake in the ground” refers to the process of getting participants to commit a priori (i.e., before simulation) to a projection of how the system — as Richmond: The Strategic Forum 139 represented by the model being used in the exercise — will perform. Often, the “putting the stake in the ground” process involves getting participants to commit to an estimate of some of the system’s key operating parameters as well. Once the stake has been sunk, the model is run. Then, participants are confronted with any differences that arise between their projections of performance and the actual performance generated by the model. If there are disparities — which is almost always the case — the third step is to resolve them. Usually lots of interesting issues arise in the resolution process. After some agreed-upon resolution, the group proceeds to the next exercise. In constructing the progression of models during this Step, it is extremely important to obtain the best available numerical data (both for the real system’s performance and for operating parameters). The quickest way to discredit a model is to show that it is using inaccurate numerical information. The estimates that are obtained for particular barometers of performance and/or operating parameters during the Forum may differ from those that are collected during this Step. However, in all instances in our experience, the two have been close enough for the basic results obtained from the models during this pre-forum step to hold up during the Forum. This is important, as it enables the facilitators to prepare in advance for at least part of the discussion which is likely to unfold during the Forum. Step 3. Setting expectations Once the Forum is convened, the first formal activity consists of introductions and setting expectations. Typically all of the players know each other quite well and if the facilitators have made several visits prior to the Forum, they also are well known to the group. Because the group is relatively “cosy,” it is usually not a good idea to have any “spectators” present at the Forum — either from the company or from the organization with which the facilitators are associated. In terms of expectations-setting, it is important that people expect that they will be challenged and also that they be given “permission” to be “wrong”. The latter must come from the CEO. It cannot be granted by Forum facilitators. It is also useful to have the message reiterated by the second tier of senior managers (usually functional and/or geographic VPs). Then, it is useful to have the message repeated at least twice each day. There usually is a lot of ego present in these gatherings and embarrassment is a real danger to spontaneity. Granting explicit permission to be wrong is vital to the success of any Forum session. Business people, even at senior levels, are usually not accustomed to thinking in the kind of intensely disciplined manner that characterizes most Forum experiences. They are certainly not used to doing so for six to eight hours at a sitting! Good Forum facilitators will keep a watchful eye out for the telltale signs of fatigue 140 System Dynamics Review Volume 13 Number 2 Summer 1997 and call unscheduled time-outs accordingly. Participants should expect that this will be done and then asked to help send the signals needed to ensure that it is done effectively. Step 4. “Big Picture” discussion Substantive discussion in a Forum begins with a look at the “Big Picture”. The notion here is first to get the group to write down a working statement of the vision (or mission) to which they feel a commitment. In all Forums in our experience, such a statement has already been in existence. Next, discussion should shift to an initial elaboration of the strategic objectives that support the stated vision. Then, once objectives have been articulated, the major planks in the strategy should be outlined. Like the vision statement, both objectives and strategy are usually clearly known to participants in advance of the session. This first piece of the Forum typically concludes with a discussion of key issues. This discussion is more open-ended than the warm-up, which really is more of an “information dump.” In the discussion, the objective is to bring to the surface potential internal and external constraints that participants feel could restrict progress toward achievement of the strategic objectives. The flipchart sheets with mission, objectives, strategy and potential constraints should be taped up and remain visible over the course of the Forum. They prove to be valuable for focusing and re-focusing discussion. It is usually interesting to compare the initial statements on these sheets with how the statements read at the close of the Forum. Step 5. Internal-consistency check exercises Most of the activity in the Forum transpires in Steps 5 and 6. Step 5 consists of a carefully orchestrated sequence of internal-consistency check exercises. The purpose of the exercises is twofold. First, they are designed to enable participants to assess the internal consistency between vision, strategy and processes/operating policies. Second, they are intended to assist in building systems thinking capacity and capacity with the stock/flow language. Building these capacities is designed to enable Forum participants to think and communicate in a more effective manner about their business after the session is over. In terms of group process, there are some excellent reasons for focusing the major activity around a progression of small group exercises. It enables people who normally do not “roll up their sleeves” together to do so, and it enables them to do so in a group that is small enough to make hiding impossible. We often rearrange Richmond: The Strategic Forum 141 the composition of the small groups for each exercise. Rearranging gives everyone a chance to rub elbows with everyone else. In addition, because large-group discussion is almost inevitably dominated by the more vocally aggressive (and, where rank is involved, often by those with higher ranks), there needs to be some way to ensure that everyone is heard. Also, because there is a new language being used, the issues are cross-functional, and a computer interface is involved, there are lots of opportunities to be “wrong.” A small group, working out of the spotlight, is one of the least threatening environments in which to be “wrong.” Participants can test-fly their ideas with other members of the small group before exposing them to the full team. Finally, the exercise format is very “doing” oriented. As such, there is a clear sense of task and a well defined time-frame for completion. Participants thus feel that they are engaged, “discovering” for themselves, and making visible progress. The potential downside of the preconceived and preformulated “sequence of exercises” approach is twofold. Participants can feel “led by a ring in the nose” or “set up.” Preoccupation with ensuring that all of the exercises are covered can cut off productive discussion before its time. The key to avoiding the “set up” feeling is getting buy-in for the sequence from the CEO and a sample of team members before the Forum. If the CEO has signed off, s/he will help to reassure team members that the progression “makes sense” should that issue arise. In very few of the Forums that we have executed to date have we completed the full complement of preformulated exercises, or not improvised an additional exercise or two, over night or over lunch. Sensing when to allow work on an exercise, or the ensuing discussion, to overflow the pre-allotted time is part of the art of being an effective facilitator. In our experience, if things are becoming intense, they should be allowed to reach a climax and then cool down. In particular, no attempt should be made to intervene or arrest a heated discussion by suggesting that the matter be tabled and proceeding with the next exercise. As already noted, the sanity-check exercises are performed in small groups (of three or four people). Each group has its own personal computer for executing simulations associated with the exercise. Usually the exercises are two to three typewritten pages. Each contains a sequence of questions. Space is left for inserting simulation outputs and simple stock/flow maps, as well as for answering free-form questions. Upon completion of each exercise, participants return to the large group to report back and for full-team discussion. Issues are brought to the surface, the question of “Can we still get there from here?” is examined, and action items are recorded. In the “putting a stake in the ground” step, participant teams are usually asked to develop an estimate of both output behavior and certain key operating parameters of the model associated with the particular exercise. Frequently, developing an 142 System Dynamics Review Volume 13 Number 2 Summer 1997 estimate of “output behavior” simply consists of laying out the numbers associated with the strategic objective. As an example, one group, whose strategic objective was defined in terms of sales revenues, was asked to estimate the revenues that the company would generate between 1996 and 2000. In another Forum, a group, who had couched their strategic objective in terms of market share, was asked to commit to market-share estimates for two company and two competitor models over a fiveyear horizon. Still another group, which was concerned with ROI, was asked to project this ratio out to 1998. In terms of “estimating operating parameters,” participants are basically asked to supply numerical values for certain key operating variables. Typically, variables include such things as: the average amount of time it takes a rookie salesperson to come up to speed, the average productivity of a rookie and an experienced salesperson, the average length of time a customer holds the company’s product before disposing of it, and the average price per unit sold. Once the “stakes” are sunk, the second step — “confronting the stakes” — proceeds. The facilitators (or participants) incorporate the parameter values into the model in use in the exercise. The model is then simulated to yield performance results which can be directly compared to the a priori estimates of performance provided by participants. Sometimes the initial model is so simple that the comparison yields no disparity. However, in our experience, usually even firstexercise models can prove to be eye-openers. In no case have we needed to progress beyond the second exercise in order to produce an “interesting” disparity between participant-estimated and model-generated performance. Once a disparity does arise, the group finds itself in a very interesting situation. They have committed to a certain prediction of performance. Participants have derived the prediction by intuiting the way that the “plumbing” (which they have “signed off”) will behave when its key operating parameters are substituted with the particular set of numerical values which they have also signed off. But now that the map has actually been simulated, model performance does not match what was intuited. At this point, the team is trapped in an internal inconsistency of its own making. The team must do one or more of the following: 1. alter the map; 2. alter its estimates of operating parameters; or 3. change its prediction with respect to performance. The use of simulation has thus imposed some real discipline on the strategy development process. It is no longer possible to make the results by consensual fiat. The advent of the first disparity between predicted and model-generated performance begins the next step in the Forum process (the discussion/resolution step). Richmond: The Strategic Forum 143 However, before discussing this step, consider the following illustration of the internal consistency “trapping” process in order to create a clearer picture of what is involved. The team who served as the basis for this illustration put a consensus “stake in the ground” around a five-year market-share prediction for two of its own, and two of its competitor’s, product lines in a particular market segment. This was the performance “stake.” Next, they provided a whole host of parameter estimates (approximately 20 in all) to use in some “plumbing” which represented the generic set of stocks and flows associated with the customer base for these four products in the given market segment. Because both the estimates of parameters and projection of performance were arrived at after considerable discussion and by consensus, the group had a high degree of ownership of the resulting a priori information. When the simulation was conducted, one company’s model-generated market shares fell below the team’s estimates by as much as 25% over the five year-period. In seeking to get to the bottom of the disparities, the group carefully examined the model’s output (which broke demand in this segment into three component sources). The examination revealed that a good part of the disparity resulted from a shared, implicit assumption about which of the three components would be the principal one in this segment. The implicit assumption had not been incorporated into the model. And, after some discussion, the group agreed that the assumption was indeed not appropriate for the particular market segment that they were using the model to look at. The assumption instead was a “hold over” which applied to a market segment that had historically been the focus of the team’s attention. This realization led to a significant reorientation of the company’s marketing strategy for the new segment. The illustration, as presented, progressed rather quickly from disparity to “fruitful resolution.” In practice, the progression has rarely been either quick or easy. Indeed, there seems to be a predictable pattern to the progression. This pattern typically has three phases: denial, resignation, and resolution. The “denial” phase most often begins with an attempt to impugn the model (or modelers). This process typically does not last too long because the team can be reminded that they signed off on the model during the pre-forum sessions. Nevertheless, given the level of cognitive dissonance that typically exists when such disparities first arise, some team members are likely to want to make modifications to the structure of the model. These modifications will usually be quite easy to implement. If changes are made, it is important that they be done (or at least reviewed) “publicly” and everyone must sign off once again. Otherwise, the model risks losing its face validity. Performing (or reviewing) the “surgery” in public also has the advantage of providing a way to practice using the language and 144 System Dynamics Review Volume 13 Number 2 Summer 1997 Fig. 2. An illustrative control panel thinking skills. After the modifications have been completed, if the performance disparities disappear (which has never been our experience) the process may continue. If they do not, participants may seek the next “avenue of denial.” In either case, an explanation may be offered (or better still, have the participants discover one for themselves) as to why the modifications had the effect that they did. This is another area where a technical knowledge of, and substantial experience with, systems thinking is indispensable. Once the “denigrate the model” gambit has been exhausted, the next phase of “denial” usually consists of questioning the parameter estimates. “Are we really sure about these numbers? Let’s try some other ones!” It is in this step that having a “control panel” can pay big dividends. It enables Forum participants to perform a large number of “what if’s” in rapid-fire succession. A control panel consists of a set of devices which enable team members to adjust all of the relevant operating parameters and policy levers in the model. Such a panel also usually contains a set of output devices which enable team members to view a representative set of output variables. A simple, illustrative control panel is pictured in Figure 2. Operation of the devices is self-explanatory: a number is typed in, a button pushed, or a slide bar moved. One particularly powerful device is the Graphical Function editor (Figure 3). The user double-clicks the device and then changes a scenario or behavioral relationship by dragging the mouse over the grid. Even very non-technical managers seem to enjoy making such modifications. Two examples of graphical function editor devices are shown. Richmond: The Strategic Forum 145 Fig. 3. Illustrative graphical functions In terms of group process for the “challenge the parameters” phase, we have found it most effective simply to allow participants to return to small groups and flail away with the control panel, rather than to attempt to proceed with the large group in a centralized facilitation manner. Regardless of whether this activity is done in the small or large group, it is a good idea to ask participants to infuse some discipline into their flailing. Typically, we facilitate this infusion by providing them with “recording forms”. The structure of the forms encourages participants to adhere to the following four-step process: 1. record the initial and altered value of the parameter being changed; 2. record an a priori prediction of the change in performance that will result from the parameter alteration; 3. record the actual change in performance; 4. resolve any disparities between predicted and actual. By adhering to this process — which is basically the same “plant the stake,” confront it, resolve disparities cycle — participants will squeeze the maximum amount of learning out of each simulation. If participants are not allowed to “gloss over” disparities, the pressure to alter thinking patterns is more difficult to ignore. As with the typical kinds of alterations that teams make to the “plumbing,” in most cases even major changes in the numerical values of operating parameters fail to eliminate the performance discrepancies that have arisen. Hence, the “deny the parameter estimates” ploy similarly soon runs out of steam. On occasion, a final denial ploy is attempted. We call this one the “deny the performance prediction” ploy. Usually, as already noted, the performance prediction is simply a restatement of a strategic objective, or of a behavior that the group feels must come to pass in order for a particular objective to be achieved. An example of the latter would be a particular volume of hiring, which must be achieved in order to get the direct sales force headcount up to the level needed to generate the target sales volume. By this 146 System Dynamics Review Volume 13 Number 2 Summer 1997 point in the strategy development process, there is usually much commitment to making the objectives “happen,” so there is a real reluctance to alter the objectives. As a consequence, the “denial” phase usually moves quickly through its last ploy, if it gets that far. Once “denial” has been exhausted as a means of eliminating the performance disparity, the team normally moves with considerable vigor into the “resignation” and “resolution” stages. The team essentially steps back, and says: “OK, we can still pull this off. We just need to figure out how to do it!” Such statements herald the beginning of Step 6, Policy Design. Step 6. Strategy design session A natural next step, after the sequence of internal-consistency check exercises, is a strategy design session. The internal-consistency exercises often call into question whether one or more of the strategic objectives can indeed be realized — given the current strategic plan and associated set of processes/operating policies. The strategy design session is an opportunity to pursue new ideas and to rethink old ones, for purposes of increasing the likelihood that the strategic objectives can be met. The session may be conducted in two parts. In the first part, participants work in small groups to identify potentially promising strategy initiatives. Then, either in small groups or as a whole, participants use one or more of the simulation models to test the initiatives for their impact on performance. Once again, the three-step discipline of “stake, confront, resolve” may be valuable when this exercise is performed. The session usually concludes with a discussion of what looks promising. Normally, it is this session which produces the greatest number of “action items.” The action items generated during this session typically take the form of some further analysis (that must be done by a staff member) of a particular strategy initiative. As many as 15 action items have emerged from one of these sessions. Step 7. Wrap-up discussion The Forum concludes with a wrap-up discussion. The discussion consists of revisiting the vision, objectives, strategy, and operating policies in light of what has gone on during the Forum. Frequently, changes in the strategy (and associated operating policies) are recorded. Less frequently, strategic objectives are modified. Only once in our experience has there been any significant change to the overarching vision statement. If the Forum has been successful, however, the team is seeing all three in both a more operational and a more systemic manner. Richmond: The Strategic Forum 147 Some discussion of “next steps” is part of the wrap-up. In our experience, “next steps” have taken several forms (some of which are discussed in the next section). Finally, it may be valuable to include a quick review of a list summarizing: action items, person responsible, and due date. The list should be transcribed and sent out to participants — along with transcriptions of the flipchart meanderings — as a way of preserving the thrust of Forum discussions. Step 8. Follow-up activities Although a Strategic Forum is a significant “event” for the underlying thought processes and associated stock/flow language to take root, it is essential that the organization pursues some form of ongoing systems thinking process or activity. To date, follow-up activities have varied. The following is a description of what happened in one company and provides an illustration of a fruitful progression. EXAMPLE. During a Forum involving this company’s operations committee (which included the CEO and eight direct reports), several important shifts in viewpoint occurred. One of these shifts entailed moving from a view of sales-force productivity as the cause of sales force-retention (i.e., one-way causality), to a view that retention in fact fed back to influence productivity as well. Productivity and retention came to be seen as locked into a mutually reinforcing relationship. The feedback from retention to productivity was both direct and indirect. It was direct in that high rates of turnover were demoralizing to those who stayed. It was indirect in that as salespeople departed, rookies had to be brought on board to replace them. Because rookies had lower productivity than those who had departed, average productivity declined. As the Forum participants discovered, the circularity of the relationship made it difficult to intuit how the system was going to behave. A good chunk of time in this Forum was spent in exploring a detailed map of the relationships governing sales-force productivity. The group’s feeling was that the sales organization needed to be involved in, and contribute to, this “learning.” This, in turn, led to several activities. The first of these was a second Forum. This one was conducted for the sales senior management team (i.e., the VP of Sales, his direct reports, and select members of their staffs). Prior to this Forum, the productivity/retention map was developed further. It then was explored in detail during the Forum. The exploration resulted in several major operating policy and strategy changes. Following the Forum, the group felt strongly that the entire sales organization needed to be exposed to “this way of thinking”. This in turn led to development of a computerbased “game” which embodied the consensus sales branch productivity map as part of the web of relationships governing the success of a sales branch. The game, 148 System Dynamics Review Volume 13 Number 2 Summer 1997 embodied in a three-day course, now has been played by virtually all of the company’s domestic and international branch sales managers (some 150 people). A version of the game is also being implemented into the firm’s core training courses for all sales people. In addition, the company’s Director of Management Education is developing systems thinking skills so that he may assist and spearhead other such interventions in the future. A session covering basic systems thinking principles also has been integrated into the company’s management development core course sequence. Conclusions For a Forum to be considered truly successful, it must be more than an “event.” Some broadscale diffusion of the systems thinking framework and associated language skills must occur. The approach and organizational conditions that are necessary in order to achieve a successful diffusion of the framework and language are the subject of much current ongoing research in the field of system dynamics. The Strategic Forum concept is still developing. Although we have learned a great deal over the last few years, there is a vast amount more to discover — both about the process and about the technology required to support the process. We hope that this article encourages others to get involved in some aspect of a Forum experience, either as a facilitator or as a participant. There is enormous potential inherent in this process for helping to develop organizations that are truly capable of designing their own success.