UGIB Risk Scores: Blatchford vs. Rockall for Clinical Intervention

Anuncio

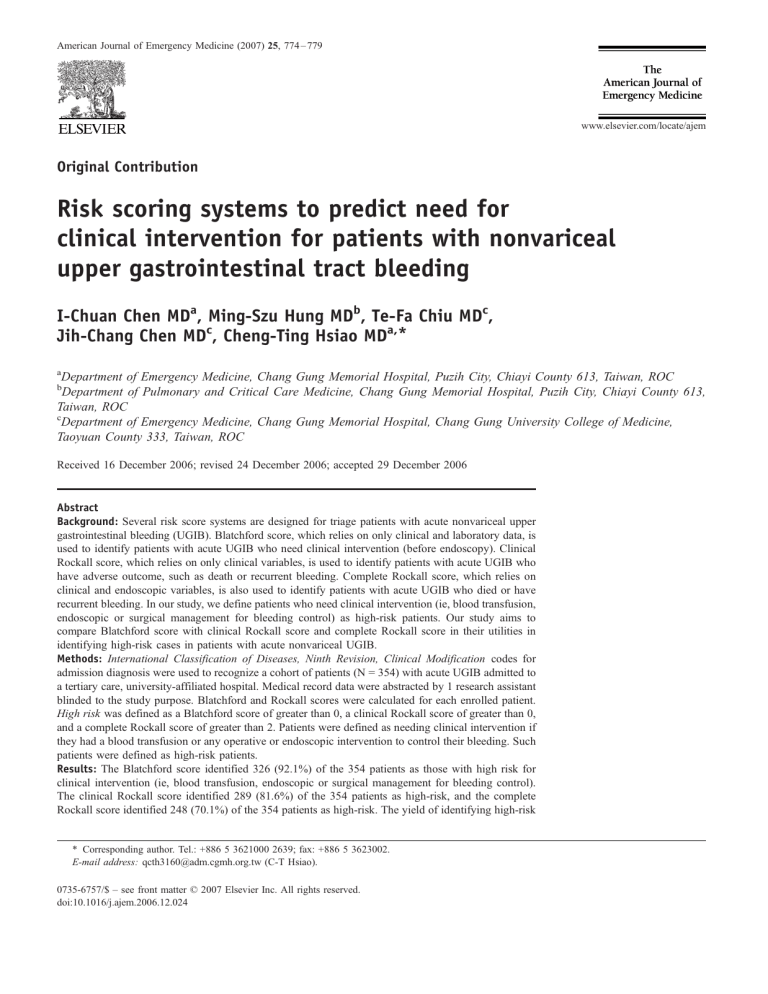

American Journal of Emergency Medicine (2007) 25, 774 – 779 www.elsevier.com/locate/ajem Original Contribution Risk scoring systems to predict need for clinical intervention for patients with nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal tract bleeding I-Chuan Chen MDa, Ming-Szu Hung MDb, Te-Fa Chiu MDc, Jih-Chang Chen MDc, Cheng-Ting Hsiao MDa,* a Department of Emergency Medicine, Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, Puzih City, Chiayi County 613, Taiwan, ROC Department of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine, Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, Puzih City, Chiayi County 613, Taiwan, ROC c Department of Emergency Medicine, Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, Chang Gung University College of Medicine, Taoyuan County 333, Taiwan, ROC b Received 16 December 2006; revised 24 December 2006; accepted 29 December 2006 Abstract Background: Several risk score systems are designed for triage patients with acute nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding (UGIB). Blatchford score, which relies on only clinical and laboratory data, is used to identify patients with acute UGIB who need clinical intervention (before endoscopy). Clinical Rockall score, which relies on only clinical variables, is used to identify patients with acute UGIB who have adverse outcome, such as death or recurrent bleeding. Complete Rockall score, which relies on clinical and endoscopic variables, is also used to identify patients with acute UGIB who died or have recurrent bleeding. In our study, we define patients who need clinical intervention (ie, blood transfusion, endoscopic or surgical management for bleeding control) as high-risk patients. Our study aims to compare Blatchford score with clinical Rockall score and complete Rockall score in their utilities in identifying high-risk cases in patients with acute nonvariceal UGIB. Methods: International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification codes for admission diagnosis were used to recognize a cohort of patients (N = 354) with acute UGIB admitted to a tertiary care, university-affiliated hospital. Medical record data were abstracted by 1 research assistant blinded to the study purpose. Blatchford and Rockall scores were calculated for each enrolled patient. High risk was defined as a Blatchford score of greater than 0, a clinical Rockall score of greater than 0, and a complete Rockall score of greater than 2. Patients were defined as needing clinical intervention if they had a blood transfusion or any operative or endoscopic intervention to control their bleeding. Such patients were defined as high-risk patients. Results: The Blatchford score identified 326 (92.1%) of the 354 patients as those with high risk for clinical intervention (ie, blood transfusion, endoscopic or surgical management for bleeding control). The clinical Rockall score identified 289 (81.6%) of the 354 patients as high-risk, and the complete Rockall score identified 248 (70.1%) of the 354 patients as high-risk. The yield of identifying high-risk * Corresponding author. Tel.: +886 5 3621000 2639; fax: +886 5 3623002. E-mail address: [email protected] (C-T Hsiao). 0735-6757/$ – see front matter D 2007 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2006.12.024 Predictors for non-variceal UGI bleeding 775 cases with the Blatchford score was significantly greater than with the clinical Rockall score ( P b .0001) or with the complete Rockall score ( P b .0001). In our total 354 patients, 246 (69.5%) patients were categorized as those with high risk for clinical intervention (ie, blood transfusion, endoscopic or surgical management for bleeding control, as aforementioned) in our study. The Blatchford score identified 245 (99.6%) of 246 patients as high-risk. Only 1 patient who met the study definition of needing clinical intervention was not identified via Blatchford score. This patient did not have recurrent bleeding nor die and did not receive blood transfusion. The clinical Rockall score identified 222 (90.2%) of 246 patients as high-risk. Twenty-four patients who met the study definition of needing clinical intervention were not recognized via clinical Rockall score. Of these patients, 0 died, 7 developed recurrent bleeding, and 6 needed blood transfusion. The complete Rockall score identified 224 (91.1%) of 246 patients as high-risk. Twenty-two patients who met the study definition of needing clinical intervention were not recognized via complete Rockall score. Of these patients, 2 died, 3 developed recurrent bleeding, and 20 needed blood transfusion. Conclusions: The Blatchford score, which is based on clinical and laboratory variables, may be a useful risk stratification tool in detecting which patients need clinical intervention in patients with acute nonvariceal UGIB. It does not need urgent endoscopy for scoring and has higher sensitivity than the clinical Rockall score and the complete Rockall score in identifying high-risk patients. D 2007 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. 1. Introduction 2. Methods Upper gastrointestinal bleeding (UGIB) has an estimated incidence of about 102 in 100 000 people per year [1]. Upper gastrointestinal bleeding is a common medical emergency in clinical practice. There is no doubt that hospitalization is mandatory for variceal hemorrhage in cirrhotic patients. However, nonvariceal UGIB is highly inconstant in severity and outcome. Patients with UGIB may present with a wide range of clinical severity, ranging from insignificant bleeding to fatal outcomes [2]. Several systems have been designed to identify patients with high risks of adverse outcomes (commonly defined as a risk of recurrent bleeding of N5% and N1% mortality) and differentiate them from patients with lower risks [3-8]. However, because clinical treatment aims to prevent patients from dying and complication, we believe that identifying which patients will require clinical intervention is more practical than identifying who may die or have recurrent bleeding. The Blatchford score suggests that it be used to identify patients with acute UGIB who need clinical intervention before endoscopy. Patients with a Blatchford score of greater than 0 are considered to require clinical intervention [9]. The clinical Rockall score is calculated from routine clinical variables. Patients with a clinical Rockall score of greater than 0 are considered to be at high risk for adverse outcomes. Besides the clinical Rockall score, the complete Rockall score is calculated from clinical and endoscopic variables. Patients with a complete Rockall score of greater than 2 are considered to be at high risk for recurrent bleeding and death [2,3,10,11]. Our study aims to compare the Blatchford score with the clinical Rockall score and the complete Rockall score in their utilities in assessing the need for clinical intervention in patients with acute nonvariceal UGIB. An electronic search was made of all adult (N18 years of age) patients with acute UGIB admitted to the emergency department (ED) of Chang Gung Memorial Hospital (Taoyuan County, Taiwan)—a tertiary care, universityaffiliated hospital—with an admission diagnosis of gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding (International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision codes 5780, 5781, and 5789). This search was made from our hospital’s medical record database and began from January 2006 to July 2006. These patients were then further selected for the absence of bleeding esophageal varices (International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification code 4650). Patients thus chosen for study had the diagnosis of UGIB without bleeding esophageal varices confirmed on endoscopy. Before endoscopy, all patients were treated with intravenous proton pump inhibitors (ie, omeprazole, pantoprazole). Patients were excluded if they did not undergo endoscopy, were not treated with proton pump inhibitors, were 18 years old or younger, or bled from lower-GI source. A patient was considered to have developed recurrent bleeding if one of the following events occurred: repeated endoscopy before hospital discharge, surgery for control of UGIB, or readmission to the hospital within 30 days of discharge due to UGIB. Patients thus identified had their case records reviewed for their initial vital signs and their laboratory test results taken at the time of presentation to the ED with UGIB. Demographic information, clinical presentation, presence of comorbid medical conditions (as defined by the Charlson comorbidity index [12]), findings of endoscopy, number of unit of blood transfusion, types of treatment of UGIB, and medication being taken at the time of admission were also reviewed. Data collections were made by 1 research assistant who was blinded to the purpose of the study and to the Rockall and Blatchford score calculations. 776 Table 1 I.-C. Chen et al. Blatchford score Admission risk marker Score component value Blood urea nitrogen level (mg/dL) z18.2 to b22.4 z22.4 to b28 z28 to b70 z70 Hemoglobin level for men (g/dL) z12 to b13 z10 to b12 b10 Hemoglobin level for women (g/dL) z10 to b12 b10 Systolic blood pressure (mm Hg) z100 to b109 z90 to b99 b90 Other markers Pulse rate z100 beats/min Presentation with melena Presentation with syncope Hepatic disease Heart failure 2 3 4 6 1 3 6 1 6 1 2 3 1 1 2 2 2 2.1. Specification of variables and statistical analysis Range of scores is from 0 to 23; maximum score is 23, high risk, greater than 0. Patients were defined as needing clinical intervention if they had a blood transfusion or any operative or endoscopic intervention to control their bleeding. Such patients were defined as high-risk patients. A Blatchford score was calculated for each patient based on points assigned for 8 clinical or laboratory variables at the time of patient presentation, including blood urea nitrogen level, hemoglobin level, systolic blood pressure, heart rate, presentation with melena, presentation with syncope, evidence of hepatic disease, and evidence of heart failure (Table 1). A Blatchford score of greater than Table 2 0 was considered as high risk, and clinical intervention was required. The clinical Rockall score, which was calculated without endoscopic finding, for each patient was based on points assigned for 3 clinical variables: patient age at presentation, shock status based on initial heart rate and systolic blood pressure, and presence of comorbid disease (Table 2). A clinical Rockall score of greater than 0 was considered as high risk for substantial adverse outcomes, such as recurrent bleeding and death associated with UGIB. The complete Rockall score (after endoscopy) was calculated for each patient based on points assigned for each of the 3 aforementioned clinical variables plus 2 endoscopic variables: endoscopic diagnosis and stigmata of recent hemorrhage based on the initial endoscopic examination. The complete Rockall score was equal to the sum of the points assigned. Patients with complete Rockall score of greater than 2 points were considered to be at high risk for substantial adverse outcomes. We compared the proportions of patients identified as high-risk using v 2 tests, and SPSS statistical software version 12 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, Ill) was used for data analysis and management. A 2-sided P value of less than .05 was thought to be statistically significant. Sensitivity and specificity in detecting patients who needed clinical intervention, had recurrent bleeding, or died were calculated for Blatchford score, clinical Rockall score, and complete Rockall score with confidence interval. 3. Results Three hundred fifty-four patients with acute nonvariceal UGIB were enrolled and analyzed. Two hundred thirty- Rockall risk score Variable Score 0 1 2 Age (y) Shock Comorbidity b60 60-79 HR N 100 beats/min z80 SBP b 100 mm Hg IHD, CHF, any major comorbidity Endoscopic diagnosis Mallory-Weiss tear or no lesion observed Clean-based ulcer, flat pigmented spot Stigmata of recent hemorrhage Peptic ulcer disease, erosive esophagitis 3 Renal failure, liver failure, metastatic malignancy Malignancy of upper GI tract Blood in upper GI tract, clot, visible vessel, bleeding The clinical Rockall score, which is calculated without endoscopic finding, for each case was based on points assigned for 3 clinical variables: patient age at presentation, shock status based on initial heart rate and systolic pressure, and presence of comorbid disease. The complete Rockall score (after endoscopy) is calculated for each case based on points assigned for each of 3 aforementioned clinical variables plus 2 endoscopic variables: the endoscopic diagnosis and stigmata of recent hemorrhage based on the initial endoscopic examination. Patients with clinical Rockall scores (before endoscopy) of greater than 0 and patients with complete Rockall scores (after endoscopy) of greater than 2 are considered to be at high risk for developing adverse outcomes (recurrent bleeding, death). HR indicates heart rate; SBP, systolic blood pressure; IHD, ischemic heart disease; CHF, congestive heart failure. Predictors for non-variceal UGI bleeding 777 seven were men (66.9%) and 117 were women (33.1%). The mean age of total number of patients was 61.6 (16.2SD) years. About 42% (148/354) were actively taking nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, including aspirin, before UGIB developed. All 354 patients were treated with proton pump inhibitors; 22 were treated with omeprazole (6.2%) and 332 (93.8%) were treated with pantoprazole. Of the Table 3 Characteristics of patients in our study No. of patients in our study No. of patients identified as high-risk in total no. of patients Blatchford score Clinical Rockall score Complete Rockall score No. of patients treated with proton pump inhibitors No. of patients treated with pantoprazole No. of patients treated with omeprazole No. of high-risk patients in our study No. of patients treated with pantoprazole in high-risk patients No. of patients identified as high-risk in our high-risk group Blatchford score Clinical Rockall score Complete Rockall score No. of missed patients (who should have been identified as high-risk but were not) Blatchford score Clinical Rockall score Complete Rockall score No. of patients treated with pantoprazole in missed patients Blatchford score Clinical Rockall score Complete Rockall score Total no. of patients who developed recurrent bleeding in our study No. of patients who developed recurrent bleeding in missed patients Blatchford score Clinical Rockall score Complete Rockall score Total no. of patients who died in our study No. of patients who died in missed patients Blatchford score Clinical Rockall score Complete Rockall score Total no. of patients who received blood transfusion in our study No. of patients treated with pantoprazole in patients with blood transfusion No. of patients who received blood transfusion in missed patients Blatchford score Clinical Rockall score Complete Rockall score 354 326 289 248 354 (92.1%) (81.6%) (70.1%) (100%) 332 (93.8%) 22 (6.2%) 246 246 245 (99.6%) 222 (90.2%) 224 (91.1%) 1 24 22 1 24 22 23 0 7 3 3 0 0 2 191 191 0 6 20 total 354 patients, 68 (19.2%) had gastric ulcer bleeding, 64 (18.1%) had duodenal ulcer bleeding, 71 (20.0%) had gastric ulcer with protruding vessel, 64 (18.1%) had duodenal ulcer with protruding vessel, and 87 (24.6%) had UGIB due to other causes (eg, esophageal ulcer, hemorrhagic gastritis). Twenty-three (6.5%) patients developed recurrent bleeding and 3 (0.85%) patients died. The Blatchford score identified 326 (92.1%) of the 354 patients as those with high risk for clinical intervention (ie, blood transfusion, endoscopic or surgical management for bleeding control). The clinical Rockall score identified 289 (81.6%) of the 354 patients as high-risk, and the complete Rockall score identified 248 (70.1%) of the 354 patients as high-risk. The yield of identifying high-risk patients with the Blatchford score was significantly greater than with the clinical Rockall score ( P b .0001) or with the complete Rockall score ( P b .0001). Of our total 354 patients, 191 (54.0%) patients needed blood transfusion. All of these 191 patients were treated with pantoprazole. A total of 246 (69.5%) patients were categorized as those with high risk for clinical intervention (blood transfusion, endoscopic or surgical management for bleeding control, as aforementioned) in our study. All of these 246 patients were treated with pantoprazole. The mean age of these high-risk patients was 63.9 (14.8SD) years, and 160 (65.0%) were men. The Blatchford score identified 245 (99.6%) of 246 patients as high-risk. Only 1 patient who met the study definition of needing clinical intervention was not identified via Blatchford score. This patient did not have recurrent bleeding nor die and did not receive blood transfusion, and he was treated with pantoprazole. Therapeutic endoscopy was performed to this patient to control bleeding caused by Mallory-Weiss tear. The clinical Rockall score identified 222 (90.2%) of 246 patients as high-risk. Twenty-four patients who met the study definition of needing clinical intervention were not recognized via clinical Rockall score. Of these patients, 0 died, 7 developed recurrent bleeding, and 6 needed blood transfusion. All of these 24 patients were treated with pantoprazole. The complete Rockall score identified 224 (91.1%) of 246 patients as high-risk. Twenty-two patients who met the study definition of needing clinical intervention were not recognized via complete Rockall score. Of these patients, 2 died, 3 developed recurrent bleeding, and 20 needed blood transfusion. All of these 22 patients were treated with pantoprazole (Table 3). 4. Discussion In patients with GI tract bleeding, the severity of an upper GI source influences the urgency of upper endoscopy, the need for blood transfusion, and the need to consult specialists to control GI tract bleeding [13-16]. In recent years, several practice guidelines and risk scores, combining clinical and endoscopic parameters, have been developed [3,5,17,18] with the aim of assisting physicians in the early stages of 778 I.-C. Chen et al. Table 4 Test characters of Blatchford score, clinical Rockall score, and complete Rockall score in detection of high-risk patients, recurrent bleeding, and death in nonvariceal UGIB Blatchford score Sensitivity Specificity Positive predictive value Negative predictive value Clinical Rockall score Sensitivity Specificity Positive predictive value Negative predictive value Complete Rockall score Sensitivity Specificity Positive predictive value Negative predictive value High-risk patients Recurrent bleeding Death 99.6 25.0 75.2 96.4 (97.7-99.9) (17.8-33.9) (70.2-79.5) (82.3-99.4) 100 8.5 7.1 100 (85.7-100) (5.9-12.0) (4.7-10.4) (87.9-100) 100 8.0 0.9 100 (43.8-100) (5.6-11.3) (0.3-2.7) (87.9-100) 90.2 38.0 76.8 63.1 (85.9-93.4) (29.4-47.4) (71.6-81.3) (50.9-73.8) 69.6 17.5 5.5 89.2 (49.1-84.4) (13.8-22.0) (3.4-8.8) (79.4-94.7) 100 18.5 1.0 100 (43.8-100) (14.8-22.9) (0.4-3) (94.4-100) 91.1 77.8 90.3 79.2 (86.8-94.0) (69.1-84.6) (86.0-93.4) (70.6-85.9) 87.0 31.1 8.1 97.2 (67.9-95.5) (26.4-36.3) (5.3-12.1) (92.0-99.0) 33.3 29.6 0.4 98.1 (6.1-79.2) (25.1-34.6) (0.1-2.2) (93.4-99.5) Values inside parentheses are 95% confidence intervals. decision making [3,15,19-23]. Such a prediction may help physicians decide about hospital admission or discharge, the level of assistance that admitted patients’ need, and the type of treatment to be adopted. Of these various scoring systems for UGIB, the complete Rockall score has been assumed as a predictive index assessing risk of rebleeding and mortality of UGIB most frequently [3,22,24]. It is based on clinical and endoscopic findings. The clinical Rockall score is obtained by clinical findings alone. However, because clinical treatment aims to prevent patients from dying, facilitate patients to heal, and prevent patients from complications, we believe that identifying which patients will require clinical intervention (ie, blood transfusion, endoscopy or surgery for bleeding control) is more logical than identifying who may die or have recurrent bleeding. Also, some patients identified to be at low risk for recurrent bleeding and death may need blood transfusion after UGIB. Admission to the hospital is indicated to such patients, and they are therefore no longer low-risk patients. The Blatchford score is a validated risk assessment device for the need for clinical intervention of patients with acute UGIB. The Blatchford score is based on only clinical and laboratory data, so it can be applied soon without the need for urgent endoscopy. Thus, we hypothesize that the Blatchford score has higher sensitivity for identifying patients with acute nonvariceal UGIB who need clinical intervention than other risk scoring systems. The findings of our study are consistent with our hypothesis. In our retrospective study of 354 patients, 246 patients were categorized as high-risk in whom clinical intervention was needed. Of 246 patients, the Blatchford score identified 245 (99.6%) patients, and only 1 was not identified. This patient did not have recurrent bleeding nor die and did not receive blood transfusion. In contrast, the clinical Rockall score missed 24 patients who needed clinical intervention; none of them died, and 7 of them developed recurrent bleeding, although there were only 23 patients who had recurrent bleeding in our total of 354 patients. The complete Rockall score missed 22 patients who needed clinical intervention; 2 of them died, 3 of them developed recurrent bleeding, and 20 of them needed blood transfusion. Only 3 people died in our total of 354 patients, and the complete Rockall score failed to recognize 2 of them. Table 4 reveals the sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, and negative predictive value of the Blatchford score, the clinical Rockall score, and the complete Rockall score in identifying patients with acute nonvariceal UGIB who needed clinical intervention, who developed recurrent bleeding, and who died. The Blatchford score had higher sensitivity in all 3 categories. The first limitation of our study is that it is a retrospective study. Medical records that are not designed for research purposes may not include all variables of research interest or may contain inaccurate descriptions. To resolve these problems, we collected all data needed by a joint review of medical records by 2 principal investigators. In addition, undefined chart review procedures result in unreliable abstraction or, worse, biased abstraction if the abstractor knows the specific hypothesis. To maximize the validity and reliability of the review process, we used several techniques recommended for chart reviews— formal inclusion criteria, abstractor blinding to specific hypotheses, abstractor blinding between predictor and outcome variables, maintenance and regular revision of a study manual, specific variable definitions, standardized abstraction forms, and periodic abstractor monitoring. A second limitation of our study is that because only medical record data from our institution were available for reviewing, the data on postdischarge outcomes may be incomplete. However, we believe that most patients discharged from our hospital would return to the same institution if UGIB recurred. A third limitation is the Predictors for non-variceal UGI bleeding impact of treatment. Although we have limited the drug options for acute UGIB to proton pump inhibitors in our study, different drugs (such as omeprazole and pantoprazole) were chosen according to the clinical physicians’ favorite. However, we believe these drug options would not have much influence to the results of our study [25,26]. 5. Conclusion In summary, the Blatchford score, which is based on clinical and laboratory variables, may be a useful risk stratification tool in detecting which patients need clinical intervention in patients with acute nonvariceal UGIB. It does not need urgent endoscopy for scoring and has higher sensitivity than the clinical Rockall score and the complete Rockall score in identifying high-risk patients. Further prospective studies are indicated to evaluate such risk stratification system in the identification of high-risk patients with acute UGIB. Acknowledgment We thank Mrs Estella Liu for her thoughtful comment on this article. References [1] Longstreth GF. Epidemiology of hospitalization for acute upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage: a population-based study. Am J Gastroenterol 1995;90(2):206 - 10. [2] Rockall TA, Logan RF, Devlin HB, Northfield TC. Selection of patients for early discharge or outpatient care after acute upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage. National Audit of Acute Upper Gastrointestinal Haemorrhage. Lancet 1996;347(9009):1138 - 40. [3] Rockall TA, Logan RF, Devlin HB, Northfield TC. Risk assessment after acute upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage. Gut 1996; 38(3):316 - 21. [4] Clason AE, Macleod DA, Elton RA. Clinical factors in the prediction of further haemorrhage or mortality in acute upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage. Br J Surg 1986;73(12):985 - 7. [5] Saeed ZA, Winchester CB, Michaletz PA, Woods KL, Graham DY. A scoring system to predict rebleeding after endoscopic therapy of nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage, with a comparison of heat probe and ethanol injection. Am J Gastroenterol 1993;88(11): 1842 - 9. [6] Pimpl W, Boeckl O, Waclawiczek HW, Heinerman M. Estimation of the mortality rate of patients with severe gastroduodenal hemorrhage with the aid of a new scoring system. Endoscopy 1987;19(3):101 - 6. [7] Bordley DR, Mushlin AI, Dolan JG, et al. Early clinical signs identify low-risk patients with acute upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage. JAMA 1985;253(22):3282 - 5. 779 [8] Katschinski B, Logan R, Davies J, Faulkner G, Pearson J, Langman M. Prognostic factors in upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Dig Dis Sci 1994;39(4):706 - 12. [9] Blatchford O, Murray WR, Blatchford M. A risk score to predict need for treatment for upper-gastrointestinal haemorrhage. Lancet 2000; 356(9238):1318 - 21. [10] Rockall TA, Logan RF, Devlin HB, Northfield TC. Variation in outcome after acute upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage. The National Audit of Acute Upper Gastrointestinal Haemorrhage. Lancet 1995; 346(8971):346 - 50. [11] Rockall TA, Logan RF, Devlin HB, Northfield TC. Influencing the practice and outcome in acute upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage. Steering Committee of the National Audit of Acute Upper Gastrointestinal Haemorrhage. Gut 1997;41(5):606 - 11. [12] Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis 1987;40(5):373 - 83. [13] Peterson WL, Barnett CC, Smith HJ, Allen MH, Corbett DB. Routine early endoscopy in upper-gastrointestinal-tract bleeding: a randomized, controlled trial. N Engl J Med 1981;304(16):925 - 9. [14] Sacks HS, Chalmers TC, Blum AL, Berrier J, Pagano D. Endoscopic hemostasis. An effective therapy for bleeding peptic ulcers. JAMA 1990;264(4):494 - 9. [15] Laine L, Peterson WL. Bleeding peptic ulcer. N Engl J Med 1994; 331(11):717 - 27. [16] Forrest JA, Finlayson ND, Shearman DJ. Endoscopy in gastrointestinal bleeding. Lancet 1974;2(7877):394 - 7. [17] Longstreth GF, Feitelberg SP. Outpatient care of selected patients with acute non-variceal upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage. Lancet 1995; 345(8942):108 - 11. [18] Hay JA, Lyubashevsky E, Elashoff J, Maldonado L, Weingarten SR, Ellrodt AG. Upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage clinical-guideline determining the optimal hospital length of stay. Am J Med 1996; 100(3):313 - 22. [19] Longstreth GF, Feitelberg SP. Successful outpatient management of acute upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage: use of practice guidelines in a large patient series. Gastrointest Endosc 1998;47(3):219 - 22. [20] Garripoli A, Mondardini A, Turco D, Martinoglio P, Secreto P, Ferrari A. Hospitalization for peptic ulcer bleeding: evaluation of a risk scoring system in clinical practice. Dig Liver Dis 2000;32(7): 577 - 82. [21] Vreeburg EM, Terwee CB, Snel P, et al. Validation of the Rockall risk scoring system in upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Gut 1999;44(3): 331 - 5. [22] Sanders DS, Carter MJ, Goodchap RJ, Cross SS, Gleeson DC, Lobo AJ. Prospective validation of the Rockall risk scoring system for upper GI hemorrhage in subgroups of patients with varices and peptic ulcers. Am J Gastroenterol 2002;97(3):630 - 5. [23] Hay JA, Maldonado L, Weingarten SR, Ellrodt AG. Prospective evaluation of a clinical guideline recommending hospital length of stay in upper gastrointestinal tract hemorrhage. JAMA 1997;278(24): 2151 - 6. [24] Camellini L, Merighi A, Pagnini C, et al. Comparison of three different risk scoring systems in non-variceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Dig Liver Dis 2004;36(4):271 - 7. [25] Regula J, Butruk E, Dekkers CP, et al. Prevention of NSAIDassociated gastrointestinal lesions: a comparison study pantoprazole versus omeprazole. Am J Gastroenterol 2006;101(8):1747 - 55. [26] Somberg LKR, Blatcher D, et al. Intermittent intravenous pantoprazole (P) maintains control of gastric pH in intensive care unit patients. Am J Gastroenterol 2002;97(Suppl):S47.