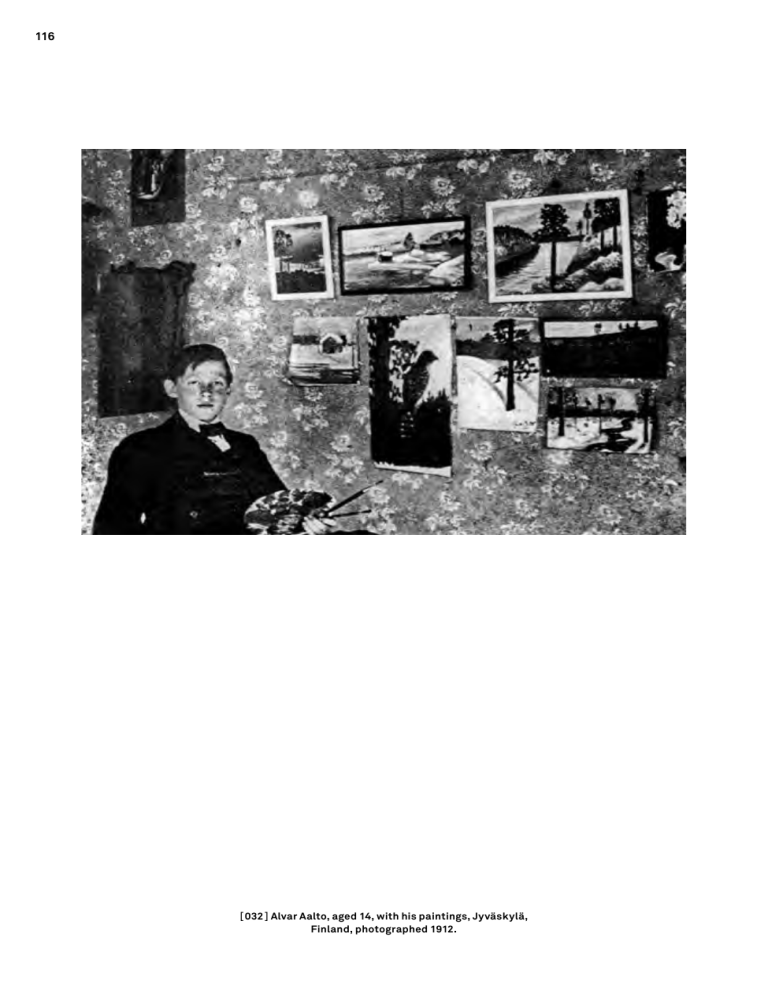

116 [ 032 ] Alvar Aalto, aged 14, with his paintings, Jyväskylä, Finland, photographed 1912. 117 Symbolic Imageries: Alvar Aalto’s Encounters with Modern Art Eeva-Liisa Pelkonen A picture of a 14-year-old Aalto in front of a group of his paintings holding a palette with brushes gives a portrait of somebody who, at an early age, thought of himself as an artist [ 032 ]. By that time he already was taking lessons from a prominent local painter and a couple of years later started to work as a semi-professional artist doing book covers and illustrations for the local publisher and newspaper in his home town, Jyväskylä. 1 Throughout his life, Aalto’s encounters with modern art were manifold: he continued to paint and draw, adding reliefs and sculpture to his repertoire at a later date; his international network included many famous artists – Alexander Calder, Fernand Leger, László Moholy-Nagy, just to name a few; and he was an active promoter of modern art in his native Finland, spearheading the first museum exhibition of continental modern art in Helsinki in 1938. Yet, unlike Le Corbusier whose art was exhibited during his lifetime in major galleries and museums, Aalto has never been taken quite seriously as an artist. This dismissal certainly has something to do with the fact that, while Le Corbusier can be credited for launching an artistic movement, Purism, Aalto’s references to art are less formally specific. Furthermore, while Le Corbusier’s paintings offer a key to his architecture, Aalto’s artistic production does not offer such direct correlation.2 As a result, links drawn between Aalto’s architecture and modern art have been based either on biographical facts or on loose formal associations. Here, Aalto’s biographer Göran Schildt deserves credit both for tracing Aalto’s contacts with continental artists as well as for speculating on some more formal affinities, commenting, for example, on Aalto’s “deep understanding of Cézanne’s conception of space”.3 118 Eeva-Liisa Pelkonen In what follows, I will argue that pursuing Aalto’s involvement with various dimensions of the world of art – including criticism – offers an important window to his engagement with the key themes surrounding modern architecture, namely how forms navigate functional, material and symbolic signification, and how they eventually enter into human experience. Furthermore, we must be reminded that the network of artists, gallery owners, museum curators, critics and historians not only facilitated Aalto’s exposure to these key debates, but eventually cemented his role and reception within the Modern Movement. Therefore, in order to understand Aalto’s unique position within the movement we must turn to his engagement with debates surrounding modern art. “Living Forms” Aalto’s early paintings offer a window to the formative stage of the development of his artistic imagination. Most often they depict landscapes in his native Finland, often with a carefully placed element that suggests movement through the landscape as a Leitmotiv – a river, a path or a ski track – inviting us with our eye to follow the journey as it disappears into the horizon. By the time he was fifteen, he had mastered the complex art of depicting spatial depth essential to the genre. For example, a painting from 1914 depicts a meandering ski-track disappearing into the horizon through a branch of snow-covered weeping willow in the foreground [ 033 ]. The choice of colours – pink and light blue in the front to accentuate the play of light [ 033 ] Alvar Aalto, Ski Track in the Snow, 1914. Watercolour and gouache, 30 × 25 cm. Private collection. Symbolic Imageries: Alvar Aalto’s Encounters with Modern Art on the snow, and greens and yellow for vegetation at the back – reverses the spatial reading as the yellows in the background seem to move forward. One is also drawn to the emphasis on the soft, curvilinear lines, which Aalto uses to entice our eyes to caress the contours of the landscape. Together with the choice of motifs, these technical subtleties make the mind ponder the deeper meanings invested in every detail. Subsequently, Aalto starts to break loose from naturalism altogether. A painting from 1916 depicting a steamboat at Jyväskylä harbour uses vertical paint strokes to replace contour lines, merging its subject matter effectively into its background [ 034 ]. Here also Aalto demonstrates his interest in how colour affects our perception: different fields of bright colour make the picture plane fluctuate to the point that it is difficult to distinguish between foreground and background. It is clear that at this point Aalto had to believe that the value of art lay not in the depicting of reality but in the artist’s ability to manipulate the perception and mental states of the viewer. It is hard to tell if Aalto had been exposed to current trends in painting while living in Jyväskylä but, considering his preferred subject matter of landscape, it is hard to imagine that he had not seen the work of one of Finland’s most prominent landscape painters, Pekka Halonen (1865–1933). Later, when working as a freelance art critic for the Helsinki daily Iltalehti in the early 1920s, Aalto wrote of how he admired not only Halonen’s ability to depict the changing seasons but the very fact that he invested every detail with deeper meaning, commenting that “Halonen sees the Nordic nature through the lens of changing seasons” and realizing how seasons [ 034 ] Alvar Aalto, Steamboat at Jyväskylä Harbour, 1916. Watercolour. Private collection. 119 120 Eeva-Liisa Pelkonen “determine the daily life of Nordic citizens”.4 For Aalto, Halonen’s paintings embodied ideas and emotions, rather than pure facts [ 035 ]. Similar emphasis on the mental, contemplative dimension of art was apparent in the review Aalto wrote about the same time of a gallery show of Finland’s most prominent Symbolist painter, Hugo Simberg (1873–1917), whose work has a certain supernatural, other-worldly quality. Aalto wrote how “his symbolism, unlike the more common symbolism of the 1880s, is not describable, through words. It is not even ‘symbolic’ in the same sense. Hugo Simberg’s paintings contain a magical vision, which has for some miraculous reason just happened to find an outlet in art.” 5 Aalto particularly admired the artist’s ability to collapse “big and small events of the world” by depicting a scene such as “silently moving skeletons dressed in black capes” going about their morbid routine in one of his most famous paintings, Tuonelan Portilla [At the Gate to the Underworld] from 1898 in a sympathetic, everyday manner [ 036 ].6 Like Halonen, Simberg, according to Aalto, makes us ponder the essence of human life. It is important to note Aalto’s impulse to register his reactions to these paintings in writing – yet another sign of his belief in the non-material essence of art; for him art depicted ideas rather than material facts. Around the same time he started to see architecture in a similar vein: a single detail or a thing was never to be considered for its face value, but was always invested with deeper meaning. The article “Motifs from Past Ages”, which he wrote for the Finnish Architectural Review in 1922, offers a new way of looking at architecture, particularly historical architecture: A portal: even as an idea, a bold venture for Finland in those days. Not just living stone, but living forms. Style. Here we met with architecture. It was a work of style as seen by a particular northern architect, the portal’s designer. This was no longer the inherited skill of the master bricklayer taking pleasure in a job well done; it was the artistic creation of an architect.7 The point Aalto makes is clear: architecture requires the transcending of a mere craft. The shift from “living stone” to “living form” suggests a move from material to the formal determination of architecture. Line gains prominence over matter as the means to register the psychological investment rather than the mere labour of the creator. The key word is style, commonly used in nineteenth- and early twentieth-century aesthetic debates, where focus shifts from a purely materialistic notion of architecture to one that endorses higher ideas and ideals invested in form. Here Aalto’s reading comes close to Heinrich Wölfflin’s: “Technical factors cannot create a style […] The word art always implies primarily a particular conception of form.” 8 The word style refers here to a moment when a work reveals the mentality of the artist and by extension the whole era. In other words, style is being understood as the non-material essence of architecture, which can only be directly experienced and felt. Like Wölfflin, Aalto referred to the “living form”, a concept that can be traced to Schiller’s notion of Lebensform (life form) and lebende Gestalt Symbolic Imageries: Alvar Aalto’s Encounters with Modern Art [ 035 ] Pekka Halonen, Winter Landscape, Kinahmi, 1923. Oil on canvas, 95.5 × 65.5 cm. Ateneum Art Museum – Finnish National Gallery, Helsinki 121 122 Eeva-Liisa Pelkonen [ 036 ] Hugo Simberg, At the Gate to the Underworld, 1898. Oil on canvas, 41 × 18 cm. Gösta Serlachius Fine Arts Foundation, Mänttä, Finland. Symbolic Imageries: Alvar Aalto’s Encounters with Modern Art (living form). As an intellectual heir to one of the leaders of the German Romantic movement, Aalto too believed that what makes a true artist, a true man, is to rise above pure nature and to mould it to one’s will. The idea behind the notion of “living form” is simple: forms were born out of life, and gained a second life, as it were, in the mind of the onlooker. This notion bears the influence of the internationally known professor of aesthetics at Helsinki University, Yrjö Hirn (1870–1952), a leading critic of speculative aesthetics, who insisted that art was an essential, everyday human activity and should be discussed as such. Aalto’s interest in the character of lines and textures that starts to gain importance over the subject matter can be understood in the context of Hirn’s words from The Origins of Art: “physiological counterparts of distinct emotions may be, so to speak, translated into lines and forms, by which the emotion is reproduced in other minds. Thus even an object of handicraft – a vase, for instance – may, by the suggestiveness of its shape, affect our emotional life in an almost immediate way.” 9 The ability of “living form” to enter and transform our minds completes its life cycle: from nature to form and back to nature, as it were. Art’s function was to participate in the ongoing processes of life. Various ideas pertaining to migration and transformation add to the “living”, animated quality of art. Aalto proposed that an architectural “motif ” had an ability to migrate from one culture to another; materials had the ability to transform into forms and lines and further into mental states. These processes depend on both geographic and temporal shifts and dislocations. For example, a single architectural motif borrowed from distant cultures embodies both the longing for past golden eras as well as aspiration for those yet to come. It is noteworthy that Aalto himself had just made his first foreign trip to Riga and was, a few years later, to conduct a honeymoon trip through the continent to Italy; his own mobile life added to the sense that architecture can migrate and take on a new life when penetrating new minds and new settings. We are also reminded about the migration of aesthetic ideas from Germany to Finland during the early part of the twentieth century that spoke to the idea that art should enhance life. Here it is worth mentioning Aalto’s indebtedness to the vitalist aesthetic theory and the idea of animation and animus carried to Finland by the pioneering modern architect Gustav Strengell, who worked with Henry van der Velde before setting up a successful office in Helsinki. Aalto’s works and words from late 1910s and early 1920s demonstrate his exposure to and interest in the ability of form to register the dynamism of the modern life he shared with Strengell and other pioneering Finnish modernists. 123 124 Eeva-Liisa Pelkonen Symbolic transfers Aalto continued to paint and draw throughout the 1920s, becoming a master of animated pencil sketches that use contour lines to depict the subject matter in a rather economic way, while leaving room for the viewer to complete the drawing with his or her eyes and mind. He includes a related artistic medium, bas-reliefs made in wood, to his repertoire in the early 1930s; they too highlight contours. One of the first depicts two strips of wood gently strolling from the upper left to the lower right corner, diverging in the middle to form an ovoid shape loosely mimicking the grain of the plywood background [ 037 ]. As in the case of his drawings, the wood reliefs gain their power from the ambiguous play between naturalism and incompleteness. The choice of bas-relief as a medium is in itself significant when considering Aalto’s continuing interest and engagement in aesthetic ideas. We must remember that the rediscovery and theorizing of the technique, along with the outline drawing, went hand-in-hand with a shift of sensibility in German aesthetic thought. The previously absolute category of the beautiful started to be theorized in terms of the polarity between inanimate and animate, revealed and hidden, and as something produced and discovered only through individual experience. The credit for the rediscovery of bas-relief goes to Johann Jochem Winckelmann, the eighteenth-century German art theorist who extolled Greek beauty exactly because it did not settle into the simple presentation of reality but transformed it in ways that made visible the aspiration towards higher goals.10 Bas-relief presented a technique by which this could be achieved: by flattening something three-dimensional to a two-dimensional surface, an object of art could come to a close encounter with the real and recede from it simultaneously. In his own passionate words, Winckelmann noted how “bas-relief, being founded in fiction, can only counterfeit reality”. He noted basrelief ’s ability to “entice”, bewitch” and “affect us with that irresistible delight which, flowing from [the artist’s] pencil, enchants our senses and imagination.” 11 In Aalto’s case, the primary tension between three-dimensional and two-­ dimensional form was supplemented with that between matter and form. A series of material relief studies suggests that he began the process with the discovery of a raw piece of wood, which at later stages he laminated and bent to form a graphic form and pattern. In this respect, his material studies bear a close resemblance to those conducted at the Bauhaus. Aalto’s studies with laminated wood correspond loosely with Moholy’s three-step process as outlined in his book Von Material zur Architektur of 1929: experiments with structure that explore inherent material qualities; texture, e.g. the impact of external force, like bending, on the material; and, finally, faktura, which applied mechanical process – multi-ply lamination – on the material. The two met when Aalto became the Finnish representative of the Congrès Internationale de l’Architecture Moderne (CIAM) in 1929; their lifelong friendship has been well documented by Schildt.12 We can only speculate on their intellectual Symbolic Imageries: Alvar Aalto’s Encounters with Modern Art exchange, but we know that Moholy gave Aalto a copy of the above-mentioned book as a present during a visit to Finland in summer 1931. Its central thesis – a trans­ cendence of matter to space, which is discussed as the medium of life – certainly corresponds with Aalto’s previous interest in “living form”. Likewise, while it is uncertain whether Moholy-Nagy shared with Aalto his early essay “Call to Elemental Art”, which he wrote with Hans Arp, Raoul Hausman and Ivan Puni, traces of its primary thesis – form-giving as a primary creative act – emerge in Aalto’s work at the time. In the essay the authors exclaim how: to surrender to the elements of form-giving is to be an artist. The elements of art can only be discovered by an artist. They do not come about as a result of his individual choice; the individual is not an entity broken off from the whole as an artist is but an exponent of the forces that give shape to the elements of the world.13 While symbolism had already introduced Aalto to the homology between form and feeling, abstract art introduced a new epistemological principle into the mix, namely that people do not observe the world from without but from within. Elemental art, as described in the quotation above, does not settle for depicting the world but rather makes visible its constituent processes and relationships. Form is considered not as the representation of a visible world but the concretization of various dynamic forces that exist within it. Art’s task is to make these invisible forces visible. Important also is the notion that we don’t simply see forms, thus keeping them at bay; forms have a way of inhabiting and invading our minds, whether we like it or not. [ 037 ] Alvar Aalto, Material Study with Laminated Wood, 1934. 90 × 84 × 8.5 cm. Alvar Aalto Museum. 125 126 Eeva-Liisa Pelkonen Moholy-Nagy served also as a link to many key critics and historians, most notably Carola Giedion-Welcker, a prominent art historian, critic and curator, and her husband Sigfried Giedion, the secretary of the CIAM, who could be considered the Modern Movement’s power couple. Aalto’s frequent visits to the continent often ended in Switzerland with the Giedions, complementing an extensive correspondence, thus enabling Aalto to access key work and ideas as they were being produced and formulated. It is, for example, very likely that, when visiting Zurich for the first time after the Berlin CIRPAC meeting in 1930, Aalto saw the exhibition Paris Produktion 1930 curated by Carola Giedion-Welcker, which displayed the work of Jean Arp and Piet Mondrian side by side. A particularly significant trip took place in 1933 when Aalto was attending the CIAM Athens meeting, whose official topic, “Functional City”, disguised the fact that, by that time, art had become a kind of shadow debate to the more practical concerns dominating the official debates. On the return leg of the trip back to Marseille, Léger presented a talk, “Discourse to Architects”, calling for more use of colour in architecture, in which Aalto is known to have actively participated.14 On the way back from Marseilles, Aalto, together with the Giedions and Moholy, stopped at La Sarraz castle, hosted by Mme de Mandrot, the great patron of modern art and architecture, whose foundation Maison des Artistes fostered interdisciplinary debates between various arts [ 038 ] [ 039 ].15 Aalto’s own formulations about the creation and experience of art certainly found resonance with those of Giedion-Welcker: “Form” and “symbol” were the key concepts of her reading of abstract art. She too believed not only that art represented the real, but that art works acted as symbols, able to condense layers of meanings, associations and experiences that had accumulated throughout history into form.16 Such symbolic forms could embody the whole “spiritual atmosphere” of an era, while at the same time bridging different eras and geographic locations. In her view, the art historian’s task was to unravel these layers of trans-historical associations and meanings, and how art embodied both individual lives as well as the lives of whole societies. She also introduced the concept of “irrationality” – which eventually migrated to the title of her husband’s first article on Aalto, “Irrationalität und Standard”, published in the German journal Cicerone in 1941 – to refer to the complicated process of form-giving resulting in a web of meanings which was mirrored in the creative act, where symbolic depth of meaning was achieved through a mental process that drew from the unconscious. It was also probably through Giedion-Welcker that Aalto gained access to the forms and ideas behind biomorphic art, as they emerged in his work around 1930; his material relief depicting a fluid ovoid against a plywood background bears a startling resemblance to Arp’s relief Amphora from 1931, which belonged to Carola Giedion-Welcker’s extensive art collection [ 040 ]. The piece originated from a period Symbolic Imageries: Alvar Aalto’s Encounters with Modern Art when Arp had given up the practice of automatic writing, where the outcome is left to chance, and started working on reliefs with titles such as “Configuration”, “Constellation” or “Construction” which emphasized the gathering together of disparate elements to form a whole. Arp described his interest around 1930: “Concretion signifies the natural process of condensation, hardening, coagulating, thickening, growing together. Concretion designates the solidification of a mass.”17 Using natural metaphors, he saw forms as “emblems of natural growth and change”. Giedion-Welcker, a major promoter and scholar covering Arp’s work from early on, credits the artist for his ability to synthesize and to throw together, as it were, different layers of meanings and anecdotes from daily life. She saw Arp’s work as a seismographic notation of his psycho-physical engagement with the world around him, resulting in art she considered as “pure poetry, [which] allows everything anecdotal and specific as well as psychological and individual to flow into one larger reservoir of unexpected and bizarre everyday human incidents.” 18 Similarly, Aalto’s curvilinear lines seem to condense together various meanings – functional, semantic, material – in single form. This becomes apparent when the form migrates to various uses; more specifically, in chronological order, to the Paimio Chair (1931), an acoustic ceiling at the Viipuri Library (1934), the Savoy Vase (1936), the Metsä Exhibition pavilion (1938) and the media wall at the New York World’s fair (1939). The versatility of the form was further amplified with the fact that multiple layers of meaning could be found even in a single work. This density of meaning is best demonstrated with the Savoy Vase. The pencil and crayon sketch drawn for the Karhula-Iittala glass design competition in 1936 – “The Eskimo Girl’s Leather Breeches” – suggests a semantic reading [ 041 ]. Yet some later sketches of the vase make us see the form as an outcome of pure formal play, while photographs of the final product with flowers suggest it was functionally motivated. Indeed, in this case, Aalto combined semantic, abstract and functional in one form. Likewise, the acoustic ceiling at Viipuri never settles into a singular reading as the form helps to create a multilayered psycho-physcial environment with both visual and acoustic components. Aalto’s use of the curvilinear form in Viipuri embodies the idea of the symbolic in the way Giedion-Welcker defined it, as that which “allows all aspects of the human soul to be thrown together at once”.19 127 128 Eeva-Liisa Pelkonen “Musée imaginaire” The migration of the curvilinear form from one use to another was further amplified by the fact that, unlike architecture, objects and furniture travel well. Soon after he launched the Paimio Chair in 1933, Aalto’s furniture was exhibited, published and written about around the globe, his newly gained international network helping in this process. The 1933 trip from Athens to Marseille on board the Patris II proved particularly fruitful. During the trip Aalto met many old friends, such as the Giedions, Moholy-Nagy and Morton Shand, editor-in-chief of The Architectural Review, who invited him to exhibit in London later that year. New acquaintances included Christian Zervos, publisher of Cahiers d’Art, one of the most important art publications of the time.20 It is at that moment that Aalto’s work entered the circulation of images and ideas around the Modern Movement. The first public display of his furniture took place at the Milan Triennale in 1933, and later, in the autumn, at the Fortnum & Mason department store in London. A leading Helsinki gallery, Salon Strindberg, exhibited Aalto’s furniture along with the above-mentioned relief and glasswork in 1934 [ 042 ]. The furniture was included in all three world’s fairs in the 1930s – Brussels (1935), Paris (1937) and San Francisco (1939) – and in New York (1939/1940) [ 043 ]. By 1935 Aalto was well aware that the Modern Movement was based on the circulation of people, images, ideas and objects. The first step Aalto took was to found, together with Maire Gullichsen and Nils-Gustav Hahl, the company Artek [ 038 ] Alvar Aalto (3rd from left), Alfred Roth (left), Aino Aalto (centre), Mme de Mandrot (right) in La Sarraz, Switzerland, August 1933. Symbolic Imageries: Alvar Aalto’s Encounters with Modern Art for the production and distribution of his furniture through a network of partners, which originally included Finmar in London, Wohnbedarf in Zurich, Svenska Artek in Stockholm, S. Jasinski in Brussels, Stylclair in Paris, GATEPAK in Barcelona, and Kerr & Co in Johannesburg [ 044 ]. The programme statement shows how the core function of exhibiting and selling the furniture was to be interlaced with the exhibiting and selling of paintings, prints, sculpture, photography and “objects from different time periods”, as well as “archaeological exhibitions”. Organized in non-linear manner, a network for these various complementary activities culminated in the statement “För ökad mondial aktivitet” [For increased international activity]. Artek sponsored the first exhibition of modern art in Finland, which took place in 1937 featuring work by Braque, Chagall, Matisse and Picasso, among others [ 045 ]. Importantly, exhibitions and publications allowed the art work to gain different meanings in different contexts as it entered into dialogue with other objects. Furniture proved quite versatile in this respect: it could be considered as art when exhibited in a museum setting and as a piece of industrial design when exhibited in a trade fair, while world’s fairs teased out various semantic readings, for example that the curvilinear forms mimicked the forms of the Finnish lake landscape. The 1938 retrospective, “Architecture and Furniture: Aalto”, which took place in the Museum of Modern Art, New York, exemplified the first. The furniture was exhibited hung on the wall, as art objects [ 046 ]. The catalogue texts by the show’s curator John McAndrew emphasized this link: “Certain materials and forms once [ 039 ] Alvar Aalto (2nd from left), Aino Aalto (centre), Mme de Mandrot (right) in La Sarraz, Switzerland, August 1933. 129 130 Eeva-Liisa Pelkonen [ 040 ] Hans Arp, Amphora (Vase), 1931. Painted wood relief, 139.3 × 109.2 × 4 cm. Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen, Düsseldorf. Symbolic Imageries: Alvar Aalto’s Encounters with Modern Art renounced because of their association with non-modern work are now used again, in new ways or even in the old ones. To the heritage of pure geometric shapes, the younger men have added free organic curves; to the stylistic analogies with the painters, Mondrian and Leger, they have added Art.”21 Importantly, McAndrew put forward the idea that the curvilinear forms found in Aalto’s furniture should be read as a shift from more geometric forms, a dichotomy which, according to him, corresponded to one found in art. McAndrew borrowed this idea from Alfred Barr, director of the museum, who in his 1936 catalogue Cubism and Abstract Art had identified these as the “two main traditions of abstract art”.22 [ 047 ] Similarly, when Aalto’s wood relief featuring an early prototype of the L-shaped stool leg ended in Alfred Roth’s sizable art collection, it entered a dialogue with other objects, including a painting by Mondrian. The circulation and reproduction of photographs supplemented the circulation of these objects as interest in Aalto’s built work grew in parallel to the popularity of his furniture. We must remember that the type of photography we now associate with modern architecture – carefully composed black-and-white photographs including close-ups from multiple angles – originated from the very moment in the mid-1920s when the Modern Movement came into being and went hand-in-hand with the establishment of organizations, publications and exhibitions whose goal was to promote and expand the mission in the international arena. Aalto got on board with the new art form soon after gaining access to the new visual imagery through books, magazines and exhibitions, and when he started getting requests [ 041 ] Vase design Eskimåkvinnans Skinnbuxor (The Eskimo Girl’s Leather Breeches) for the Karhula-Iittala glass design competition, 1936. Crayon, pastel and gouache on paper collage, 70 × 50 cm. Design Museum Helsinki. 131 132 Eeva-Liisa Pelkonen from editors and curators to publish and exhibit his work. Tellingly, his correspondence with Sigfried Giedion deals predominantly with the shipment of objects and drawings to be displayed at various CIAM-related exhibitions or with the sending of photographs. In a letter of 1933, Giedion wrote to Aalto: “Your sanatorium has arrived. One can sense your (or Aino’s?) hand in every plate!” 23 Aalto responded to requests for photographs by working with a number of leading photographers, most famously Heinrich Iffland, Gustaf Welin and Eino Mäkinen, who well understood that photography was not about documenting facts but about registering and choreographing the reactions of the beholder. In a letter to Zervos, whose magazine Cahiers d’Art was conceived around high-quality photographic reproductions of art work, Aalto noted how his “photographer [Welin] was at that very moment on his way to photograph the Viipuri Library”.24 The package of photographs Aalto eventually sent to Zervos in 1936 contained several now iconic shots of the building, among them the round skylights in the reading room and the undulating ceiling in the auditorium [ 048 ].25 Considering that most of Aalto’s work was located in Finland, it was these photographs that enabled his work to enter the historical lexicon of modern architecture. Zervos was convinced enough by the photographs to suggest adopting Aalto’s skylights into the planned museum of modern art in Paris.26 The fact that he had never visited the building was irrelevant. Zervos did not consider that photographic reproduction replaced or destroyed an original work of art (or architecture for that matter), but made it [ 042 ] Exhibition of Aalto furniture with wood relief in the background, Salon Strindberg, Helsinki, 1934. → [ 043 ] Finnish Pavilion, New York World’s Fair, USA, 1937–39. 134 Eeva-Liisa Pelkonen [ 044 ] Cover of an Artek brochure, late 1930s. [ 045 ] Invitation to the opening of an exhibition of French art at the Artek gallery, 1937. Symbolic Imageries: Alvar Aalto’s Encounters with Modern Art enter into ongoing discourse – in the case of Viipuri, into the discourse around the proper design of a museum dedicated to the display of modern art.27 Neither did photographic reproduction replace the need to display the original art work; in fact, in tandem to publishing one of the most widely circulated art journals of his time, he ran an art gallery. Through exhibitions and publications, Aalto’s oeuvre thus entered what the French art theorist and minister of culture André Malraux famously called the “musée imaginaire”, translated into English as “museum without walls.” 28 This notion referred to the moment when museums and publications made it possible for an art work to transcend geographic and temporal boundaries as well as well-­ defined historical and stylistic categories and enter into the world of images and discourse. Although Malraux did not address architecture per se, the implications might have been even more drastic if buildings were made known well beyond their physical location. Furthermore, Aalto’s photography allowed buildings to enter into an intellectual discussion that exceeded even the discipline of architecture. Malraux also talked about the power of images whereby art works enter our consciousness; without us even knowing, we carry them in our minds where they communicate with us and with each other. To be sure, both architectural and art history depend on photography by allowing works to be compared, paired and organized into categories according to formal and technical similarities. Rather than a linear process, the link between art and architecture ceases at this point to do with synthesis but goes through a web of images, concepts and ideas that converge and migrate to our consciousness in myriad ways. The way photographs came to govern Aalto’s reception proves the point. Take, for example, how the juxtaposition of images in the second issue of Siegfried Giedion’s Space, Time and Architecture (1949) – Savoy Vase, plan of the Finnish Pavilion in the New York World’s Fair and Finnish lake landscape – was an example of the outcome of Malraux’s thesis [ 049 ]. All sharing the same formal trope, the curvilinear form, the gathered photographs trigger associations between them, and in so doing enter our active imaginations making us speculate, for example, about the various geographic and geopolitical meanings of Aalto’s formal language. It is therefore no surprise that that single page has perhaps influenced Aalto’s reception more than any single photo­graph or project. The combination of images took on a life of their own, entering into scholarship and various interpretations of Aalto’s work, perhaps even into his own mind. → [ 046 ] Installation view of the exhibition Aalto. Architecture and Furniture, MoMA, New York 1938. 135 138 Eeva-Liisa Pelkonen Latencies In many ways, the debates surrounding the relationship between art and architecture can be considered an untold story in the history of modern architecture in general and the CIAM discourse in particular. For example, it is rarely mentioned that CIAM grew under the broader umbrella of the Maison des Artistes founded in 1926. Besides hosting the first meeting of CIAM in 1928, Mme de Mandrot hosted numerous other events for various artistic communities at her castle in La Sarraz, which served as a lively summer meeting place for a large group of architects, artists, musicians and filmmakers of diverse backgrounds who, as the Italian architect Ernesto N. Rogers put it, shared the same “flame” for modern art.29 Aalto stopped at the castle on his way back from Marseille, yet another sign of his integration into the broader artistic community. While the relationship between art and architecture was discussed as early as the Athens meeting in 1933 entitled “The Functional City”, it gained momentum and urgency only after the Second World War, first in Bridgewater in 1947, and then as the main focus in Bergamo in 1949, appropriately titled “Art and Architecture”. In the same year, Giedion published his chapter on Aalto and Ernesto Rogers, editor-in-chief of the Italian magazine Domus, asked Aalto to reflect on the relationship between architecture and abstract art. Aalto’s text, which took the form of a thirteen-page illustrated article, “Architettura e arte concreta” [Architecture and Concrete Art], deserves a close reading.30 It is the first of his to address the relationship [ 047 ] Cover of the catalogue by Alfred Hamilton Jr. Barr for the exhibition Cubism and Abstract Art, MoMA, New York 1936. Symbolic Imageries: Alvar Aalto’s Encounters with Modern Art between art and architecture in a more explicit, albeit subtle manner. Importantly, he starts by rejecting the most obvious reading about the relationship: the notion of the synthesis of art. He had “no interest in having more monumental paintings in public buildings,” he exclaimed, before starting to weave a more complex story that has to do with how forms come into being, transform to new contexts and migrate into different uses. The common “root” between the two refers to the germ of the idea that contains such evolutionary powers. The biological reference is significant and the article abounds in references to various kinds of processes and transformations. Translated into English as “The Trout and the Stream”, the essay associates this kind of creative process with a biological one: architecture and its details are in some way all part of biology. Perhaps they are, for instance, like some big salmon or trout. They are not born fully grown; they are not even born in the sea or water where they normally live. They are born hundreds of miles away from their home grounds, where the rivers narrow to tiny streams, in clear rivulets between the fells, in the first drops of water from the melting ice, as remote from their normal life as human emotion and instinct are from our everyday work.31 The sudden shift of subject matter from the growth of a fish to mental processes at the end of the article captures the main thesis: practical and functional solutions that stem from a design process that allows imagination and instinct to run free are as healthy and robust as the salmon born in clear waters. The river could also be interpreted as a metaphor for an idea of the human unconscious, able to store and synthesize experiences and information. “Rooted”, as it were, in the human unconscious, a certain type of design process allows aspects of this vast reservoir to percolate to the surface and make itself manifest in visible form, like a tree or a trout. Much of the essay is devoted to the discussion of Aalto’s own design process, which he insists does not follow a rational or linear path. Before beginning to design he insists on putting aside all practical concerns, arguing that only a more unconscious process allows one to accommodate both practical as well as human concerns. Using his by now signature formal trope the curvilinear form as an example, he explains how it first appeared in his work through material studies with wood, without any particular functional purpose in mind, but later gained several different kinds of functional application. He characterizes this process as instinctual and “irrational”, without a clear determined path: “I can mention that what appears to be nothing but playing with forms may unexpectedly, much later, lead to the emergence of an actual architectural form.” 32 In the end, the form can, in other words, absorb different programmatic material, as well as psychological and cultural requirements. Form in this case is not the outcome, but a sponge of sorts that allows all dimensions of architecture to coexist. → [ 048 ] Wall of the auditorium at Viipuri Library, Viipuri (Vyborg), Karelia (Russia, formerly Finland), 1927–35, photographed by Gustaf Welin, c. 1935. 139 142 Eeva-Liisa Pelkonen [ 049 ] A page from Sigfried Giedion’s Space, Time and Architecture, Harvard University Press, Cambridge 1949. Symbolic Imageries: Alvar Aalto’s Encounters with Modern Art He describes scribbling ideas intuitively on paper, without a preconceived idea of the outcome, and claims that this intense creative experience leads to an equally intense artistic experience for the beholder. He then goes on to suggest that in this way architecture can gain depth of meaning – a quality he admired in abstract: “[Abstract art]… can be understood purely and solely through feeling, even though ideas about construction and the web of human tragedy often come into it and loom behind it. In this way it is a weapon that can create in us a flow of purely human feeling that the written word has somehow lost.” 33 References to creativity/creation suggest that a certain type of mental activity – “instinctual” as opposed to “rational” – allows the mind to make connections and synthesize information and, perhaps most importantly, take a hike into the deepest unconscious. The essay also refers to longer historical transfers. Take a single architectural detail – a classical column is given as an example. It contains a memory of its wooden tectonic origins, while evolving through time. The transformation depends on the investment of “human qualities”, in Aalto’s words, which can be interpreted as the ability to turn a purely material condition into a cultural symbol. Aalto’s sketches thus culminate in the move from naturalism to the registration of the effects that natural phenomena have on the mind of the creator and subsequently on the onlooker. The travel sketches in particular allow us to feel Aalto’s eye scanning the environment for characteristic elements, be it an architectural fragment, branch of a tree or a human silhouette, registering the eye’s movement, as it [ 050 ] Alvar Aalto, Encounter in a Village Street, travel sketch from Morocco, 1951. Pencil on tracing paper, 33 × 25 cm. Private collection. 143 144 Eeva-Liisa Pelkonen were, with quick pencil strokes [ 050 ]. Aalto used the sketch as a tool to notate impressions and observations before they had been fully processed through reason. Aalto’s Domus essay maintains that lines and forms have a power to migrate in and out of our consciousness. They help us see and make sense of the world around us, produce meanings, even suggest new solutions to problems. Suggesting a fluid and porous relationship between locations, meanings, and between subject and object, art is posited as something that helps us organize, represent and make sense of the world around us and enter into communion with other people. Putting pictures on the wall is not enough; only by entering the shared transitory symbolic realm of art can both the producer and viewer submit themselves to dialogue, change and transformation. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 For more information about Aalto’s artistic career see Erik Kruskopf, Alvar Aalto Kuvataiteilijana, Helsinki, Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura, 2012. I am referring to Robert Slutzky’s and Colin Rowe’s seminal article from 1963, “Transparency: Literal and Phenomenal”, Perspecta, Vol. 8. (1963), pp. 45–54. The article draws parallels between a number of Le Corbusier’s projects, most notably Villa Garches and Cubism. Göran Schildt, Alvar Aalto: The Early Years, New York, Rizzoli, 1984, p. 191. Alvar Aalto, “Pekka Halonen”, Iltalehti, 24 March 1922. Alvar Aalto, “Hugo Simberg”, Iltalehti, 9 March 1922. Ibid. Alvar Aalto, “Menneitten aikojen motiivit”, Arkkitehti 2, 1922, p. 25; English trans. from Göran Schildt, Aalto in His Own Words, Helsinki 1997, p. 33. Heinrich Wölfflin, Renaissance and Baroque, Ithaca, Cornell University Press, 1966, p. 79. Yrjö Hirn, The Origins of Art: A Psychological and Sociological Inquiry, London, Macmillan, 1900, p. 98. 10 My discussion of Winckelmann and German aesthetic tradition has been informed by Barbara Maria Strafford, “Beauty of the Invisible: Winckelman and the Aesethetics of Imperceptibility”, Zeitschrift für Kunstgeschichte, vol. 43, 1980, pp. 65–78. 11 Johann Joachim Winckelman, Reflections on the Painting and Sculpture of the Greeks, London, A. Millar on the Strand, 1765, p. 93. 12 See Schildt 1984 (footnote 3). 13 Raoul Hausmann, Hans Arp, Ivan Puni and László MaholyNagy, “Aufruf zur elementalen Kunst”, De Stijl 10, October 1921, quoted and translated by Oliver Árpad István Botar, “Prolegomena to the Study of Biomorphic Modernism: Biocentrism, László MoholyNagy’s ‘New Vision’ and Ernõ Kallai’s Bioromantic”, Ph.D. thesis, University of Toronto, 1998, p. 405. 14 See Fernand Léger, “Discourse to Architects”, reprinted in Martin Steinmann, CIAM: Internationale Kongresse für Neues Bauen: Congrès Internationaux d’Architecture Moderne: Dokumente, 1928–1939, Basel, Birkhäuser, 1979, pp. 130–32. 15 16 17 18 19 For Aalto’s participation see Nils-Gustav Hahn, “Kongressen Reser” [Congress Travels], Hufvudstadsbladet, 10 September 1933, p. 13. For more detail regarding Aalto’s relationship to Mme de Mandrot, see Antoine Baudin, Hélène de Mandrot et la Maison des Artistes de La Sarraz, Lausanne, Editions Payot, 1998, pp. 161–69. For more discussion about Giedion-Welcker’s writings and ideas, see Iris Bruderer-Oswald, Das neues Sehen: Carola Giedion-Welcker und die Sprache der Moderne, Sulgen, Benteli, 2007. Jean Arp, “Looking”, in Arp, exhibition catalogue, New York, Museum of Modern Art, 1958, pp. 14–15. Carola Giedion-Welcker, “Hans Arp: Dichter und Maler”, reprinted in Carola Giedion­Welcker: Schriften, 1926–71, Cologne, M. Dumont Schenbert, 1973, p. 249. Carola Giedion-Welcker, Plastik des XX. Jahrhunderts: Volumen und Raumgestaltung, Stuttgart, Hatje, 1955, p. 5. The quote, serving as introductory motto to the text is by Jakob Bachofen. Symbolic Imageries: Alvar Aalto’s Encounters with Modern Art 20 Aalto subscribed to numerous international magazines, including Cahiers d’Art between 1927 and 1929. 21 John McAndrew, Foreword, Architecture and Furniture: Alvar Aalto, exhibition catalogue, New York, Museum of Modern Art, 1938, p. 3. 22 Alfred Barr, Jr., Cubism and Abstract Art, New York, Museum of Modern Art, 1936, p. 19. 23 Giedion to Aalto, postcard, written in Zurich, 6 August 1933; Alvar Aalto Museum. Aino was Alvar Aalto’s wife and professional partner. 24 Aalto to Zervos, letter, written in Turku in 1936; reprinted in Christian Derouet, Zervos et Cahiers d’Art, Paris, Centre Pompidou, 2011, pp. 88–89. 25 The set of photographs and drawings of Viipuri Library that Aalto posted to Zervos is published in ibid., pp. 90–93. 26 Zervos discussed the museum project in the article “Exposition Van Gogh”, published in Cahiers d’Art 1–3, 1937, pp. 98–99. The paragraphs dealing with Aalto’s Viipuri Library are reprinted in Derouet, op. cit., p. 92. 27 Zervos published Aalto’s Finnish Pavilion for the Paris World’s Fair in the fair’s Special Issue; see Cahiers d’art: Souvenirs de l’Exposition 1937 8–10, 1937. 28 André Malraux, Museum Without Walls, Garden City, NY, Doubleday, 1967; trans. from Le Musée Imaginaire, Paris, Gallimard, 1965. The book grew out of a 1947 article of the same name. 29 Ernesto Rogers, “La Maison des Artistes”, Domus 212, August 1946, p. 2; quoted in Antoine Baudin, Hélène de Mandrot et la Maison des Artistes de La Sarraz, Lausanne, Editions Payot, 1998, p. 301. 30 Alvar Aalto, “Architettura e arte concreta”, Domus 223–225, 1947, pp. 103–15; English trans. from Göran Schildt, Alvar Aalto in His Own Words, New York, Rizzoli, 1998, p. 107. 31 Ibid., p. 109. 32 Ibid. 33 Ibid. 145