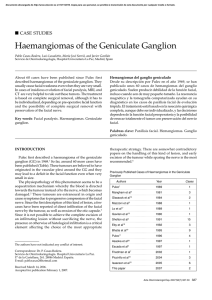

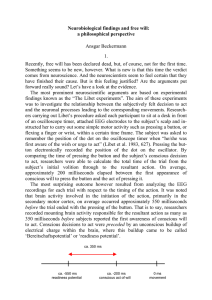

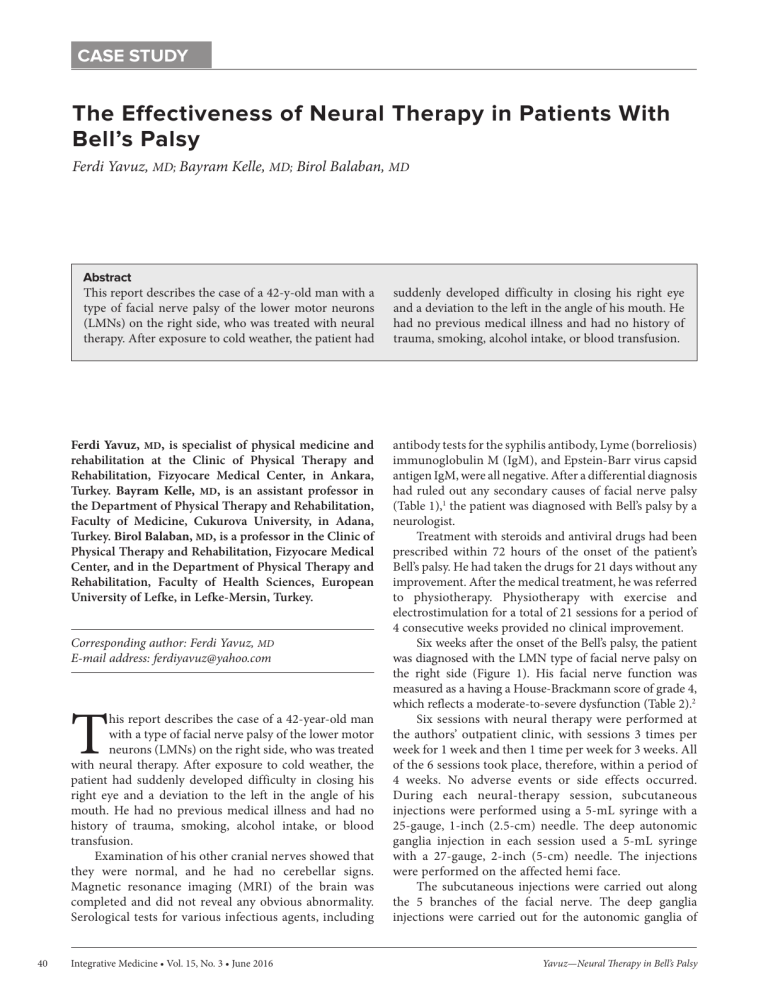

CASE STUDY The Effectiveness of Neural Therapy in Patients With Bell’s Palsy Ferdi Yavuz, MD; Bayram Kelle, MD; Birol Balaban, MD Abstract This report describes the case of a 42-y-old man with a type of facial nerve palsy of the lower motor neurons (LMNs) on the right side, who was treated with neural therapy. After exposure to cold weather, the patient had Ferdi Yavuz, MD, is specialist of physical medicine and rehabilitation at the Clinic of Physical Therapy and Rehabilitation, Fizyocare Medical Center, in Ankara, Turkey. Bayram Kelle, MD, is an assistant professor in the Department of Physical Therapy and Rehabilitation, Faculty of Medicine, Cukurova University, in Adana, Turkey. Birol Balaban, MD, is a professor in the Clinic of Physical Therapy and Rehabilitation, Fizyocare Medical Center, and in the Department of Physical Therapy and Rehabilitation, Faculty of Health Sciences, European University of Lefke, in Lefke-Mersin, Turkey. Corresponding author: Ferdi Yavuz, MD E-mail address: [email protected] T his report describes the case of a 42-year-old man with a type of facial nerve palsy of the lower motor neurons (LMNs) on the right side, who was treated with neural therapy. After exposure to cold weather, the patient had suddenly developed difficulty in closing his right eye and a deviation to the left in the angle of his mouth. He had no previous medical illness and had no history of trauma, smoking, alcohol intake, or blood transfusion. Examination of his other cranial nerves showed that they were normal, and he had no cerebellar signs. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain was completed and did not reveal any obvious abnormality. Serological tests for various infectious agents, including 40 Integrative Medicine • Vol. 15, No. 3 • June 2016 suddenly developed difficulty in closing his right eye and a deviation to the left in the angle of his mouth. He had no previous medical illness and had no history of trauma, smoking, alcohol intake, or blood transfusion. antibody tests for the syphilis antibody, Lyme (borreliosis) immunoglobulin M (IgM), and Epstein-Barr virus capsid antigen IgM, were all negative. After a differential diagnosis had ruled out any secondary causes of facial nerve palsy (Table 1),1 the patient was diagnosed with Bell’s palsy by a neurologist. Treatment with steroids and antiviral drugs had been prescribed within 72 hours of the onset of the patient’s Bell’s palsy. He had taken the drugs for 21 days without any improvement. After the medical treatment, he was referred to physiotherapy. Physiotherapy with exercise and electrostimulation for a total of 21 sessions for a period of 4 consecutive weeks provided no clinical improvement. Six weeks after the onset of the Bell’s palsy, the patient was diagnosed with the LMN type of facial nerve palsy on the right side (Figure 1). His facial nerve function was measured as a having a House-Brackmann score of grade 4, which reflects a moderate-to-severe dysfunction (Table 2).2 Six sessions with neural therapy were performed at the authors’ outpatient clinic, with sessions 3 times per week for 1 week and then 1 time per week for 3 weeks. All of the 6 sessions took place, therefore, within a period of 4 weeks. No adverse events or side effects occurred. During each neural-therapy session, subcutaneous injections were performed using a 5-mL syringe with a 25-gauge, 1-inch (2.5-cm) needle. The deep autonomic ganglia injection in each session used a 5-mL syringe with a 27-gauge, 2-inch (5-cm) needle. The injections were performed on the affected hemi face. The subcutaneous injections were carried out along the 5 branches of the facial nerve. The deep ganglia injections were carried out for the autonomic ganglia of Yavuz—Neural Therapy in Bell’s Palsy Table 1. Causes of Secondary, Unilateral Facial Nerve Palsy Types of Causes Examples Metabolic Disease • Diabetes • Preeclampsia Stroke • Ipsilateral pontine infarction • Pontine tegmental hemorrhage Infection • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • Hansen’s disease (leprosy) Otitis media Mastoiditis Herpes simplex infection Varicella zoster infection Ramsey–Hunt syndrome Influenza viruses Borreliosis Cryptococcosis Neurocysticercosis Toxocariasis Tuberculous meningitis Parotitis and parotid abscess Malignant external otitis Syphilis Surgery • Removal of cerebellopontine angle tumors Trauma • Head trauma (crush injury) • Birth injury Tumor • Facial nerve neurinoma • Cerebellopontine angle tumors (neurinoma) • Pons tumor • Tumors of the petrosal bone • Tumors of the middle ear • Leucemia • Tumors of the parotid gland • Lymphoma Immune System Disorder • • • • Drugs • Interferon • Linezolid Other Causes • Moebius syndrome • Melkersson–Rosenthal syndrome • Sarcoidosis • Histiocytosis X • Autism • Asperger’s syndrome • Parkinson syndrome Guillain–Barré syndrome Miller–Fisher syndrome Systemic lupus erythematodes Myasthenia gravis Yavuz—Neural Therapy in Bell’s Palsy Figure 1. Examination of Facial Nerve Function Before Neural Therapy A B Note: Figure 1A shows inability to lift his right eyelid and Figure 1B shows drooping corner of mouth and loss of nasolabial fold on his right side. Integrative Medicine • Vol. 15, No. 3 • June 2016 41 Table 2. House-Brackmann Scores HBS Grade 1 • Normal, symmetrical function in all areas 2 • Slight weakness on close inspection • Complete eye closure with minimal effort • Slight asymmetry of smile with maximal effort • Slight synkinesis, absent contracture or spasm 3 • • • • 4 • • • • • • Obvious disfiguring weakness Inability to lift brow Incomplete eye closure Asymmetry of mouth with maximal effort Severe synkinesis Mass movement, spasms 5 • • • • • • Motion barely perceptible Incomplete eye closure Slight movement at corner of mouth Synkinesis Contracture Usually absence of spasm 6 • • • • • No movement Loss of tone No synkinesis Contracture Spasm A Obvious weakness but not disfigurement Inability to lift eyebrow Complete and strong eye closure Asymmetrical mouth movement with maximal effort • Obvious but not disfiguring synkinesis • Mass movement, spasms Abbreviation: HBS, House-Brackmann score. oticum and pterygopalatinum. A total of 10 mL of a solution consisting of 0.4% lidocaine was used for each subcutaneous injection, and 2 to 3 mL of a solution consisting of 1% procaine was used for the infiltration of the autonomic ganglia. After the 6 neural therapy sessions, the patient’s House-Brackmann score was grade 1, which describes a normal, symmetrical function in all areas (Figure 2). Since the treatments occurred, the patient has been asymptomatic, and no recurrence has been noted during his follow-up visits. A unilateral, peripheral, facial nerve palsy may have a detectable cause (ie, may be a secondary facial nerve palsy) or may be idiopathic (ie, primary, without an 42 Figure 2. Examination of Facial Nerve Function After Neural Therapy Integrative Medicine • Vol. 15, No. 3 • June 2016 B Note: Figure 2A shows the patient can lift his right eyelid and Figure 2B shows the patient can move his mouth symmetrically. There is no sign with drooping corner of mouth and loss of nasolabial fold. obvious cause, such as Bell’s palsy).3-5 Secondary facial nerve palsy can be due to various causes (Table 1) and is generally less prevalent than Bell’s palsy at 25% versus 75%,6 respectively. Bell’s palsy was first described by Friedreich7 in 1974 and is a diagnosis of exclusion.8 In the treatment of Bell’s palsy, many therapies consist of corticosteroids, antiviral agents, exercise physiotherapy, electrostimulation, and surgical decompression. Corticosteroids and antivirals are strongly recommended in the guideline for patients with Bell’s palsy. No recommendations have been made regarding offering exercise physiotherapy for acute facial nerve palsy of any severity. However, exercise physiotherapy is weakly Yavuz—Neural Therapy in Bell’s Palsy recommended for patients with persistent facial muscle weakness.9 The use of electrostimulation is also weakly recommended for patients with Bell’s palsy of any severity.9 Facial nerve palsy can take up to 1 year to improve.10 Patients with incomplete palsy have a better prognosis than patients with complete palsy.11 Without treatment, the prognosis for complete Bell’s palsy is generally fair, but approximately 20% to 30% of the patients are left with varying degrees of permanent disability.5,8,12 Approximately 80% to 85% of patients recover spontaneously and completely within 3 months, whereas 15% to 20% experience some kind of permanent nerve damage.12 Neural therapy is an injection treatment that is designed to repair the dysfunction of the autonomic nervous system and shows its effects by correcting the electrical condition of cells and nerves. Thus, the bioelectric disturbance at a specific site or nerve ganglion can be restored to normality. In neural therapy, local anesthetics, usually procaine or lidocaine, are used. Neural therapy involves the injection of local anesthetics into peripheral nerves, autonomic ganglia, scar tissues, endocrine glands, acupuncture points, trigger points, and other tissues.13 Some clinical trials and case reports have shown that neural therapy could be an effective treatment for relieving pain and improving functional loss or disability for patients with various disorders.14-16 However, the effectiveness of neural therapy is still in question.17,18 Conclusion The authors believe that this case review is the first description of the effectiveness of neural therapy for patients with Bell’s palsy. In the current case, the neural therapy was used as an alternative treatment, which worked very well for the patient’s recovery from Bell’s palsy. Yavuz—Neural Therapy in Bell’s Palsy Author Disclosure Statement The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest. References 1. Finsterer J. Management of peripheral facial nerve palsy. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2008, 265(7):743-752. 2. House JW, Brackmann DE. Facial nerve grading system. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1985;93(2):146-147. 3. Kawiak W, Dudkowska A, Adach B. Diagnostic difficulties in etiology of the lesion of peripheral neuron of the facial nerve during the growth of sialoma. Ann Univ Mariae Curie Sklodowska. 1993;48:125-128. 4. Peitersen E. Bell’s palsy: The spontaneous course of 2,500 peripheral facial nerve palsies of different etiologies. Acta Otolaryngol Suppl. 2002;549:4-30. 5. Shaw M, Nazir F, Bone I. Bell’s palsy: A study of the treatment advice given by neurologists. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2005;76(2):293-294. 6. Peitersen E. Bell’s palsy: The spontaneous course of 2,500 peripheral facial nerve palsies of different etiologies. Acta Otolaryngol Suppl. 2002;549:4-30. 7. Wolf SR. Idiopathic facial paralysis. HNO. 1998;46(9):786-798. 8. Axelsson S, Lindberg S, Stjernquist-Desatnik A. Outcome of treatment with valacyclovir and prednisone in patients with Bell’s palsy. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2003;112(3):197-201. 9. de Almeida JR, Guyatt GH, Sud S, et al. Management of Bell palsy: Clinical practice guideline. CMAJ. 2014;186(12):917-922. 10. Atzema C, Goldman RD. Should we use steroids to treat children with Bell’s palsy? Can Family Physician. March 2006;52:313-314. 11. Adour KK, Wingerd J. Idiopathic facial paralysis (Bell’s palsy): Factors affecting severity and outcome in 446 patients. Neurology. 1974;24(12):1112-1116. 12. Slavkin HC. The significance of a human smile: Observations on Bell’s palsy. JADA. 1999;130(2):269-272. 13. Nazlıkul H. In: Nazlıkul H, ed. Nöralterapi Teknikleri ve Bozucu Alan Terapisi. Nöralterapi, Turkey: Nobel Tıp Kitabevleri; 2010. 14. Weinschenk S, Brocker K, Hotz L, Strowitzki T, Joos S; HUNTER (Heidelberg University Neural Therapy Education and Research) Group. Successful therapy of vulvodynia with local anesthetics: A case report. Forsch Komplementmed. 2013;20(2):138-143. 15. Hui F, Boyle E, Vayda E, Glazier RH. A randomized controlled trial of a multifaceted integrated complementary-alternative therapy for chronic herpes zoster-related pain. Altern Med Rev.2012;17(1):57-68. 16. Atalay NS, Sahin F, Atalay A, Akkaya N. Comparison of efficacy of neural therapy and physical therapy in chronic low back pain. Afr J Tradit Complement Altern Med. 2013;10(3):431-435. 17. Brobyn TL, Brobyn TL, Chung MK, LaRiccia PJ. Neural therapy: An overlooked game changer for patients suffering chronic pain?. J Pain Relief. 2015;4:184. 18. Weinschenk S. Neural therapy—A review of the therapeutic use of local anesthetics. Acupunct Related Ther. 2012;1:5-9. Integrative Medicine • Vol. 15, No. 3 • June 2016 43