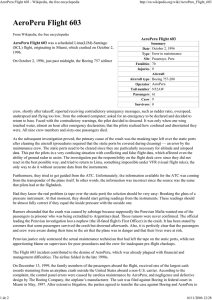

USAARL Report No. 93-2 Flight Helmets: How They Work and Why You Should Wear One (Reprint) John S. Crowley Biomedical Applications Research Division . and Joseph R. Licina James E. Bruckart Biodynamics Research Division October 1992 United States Army Aeromedical Research Laboratory Fort Rucker, Alabama 36362-0577 Notice Qualified reouesters Qualified requesters may obtain copies from the Defense Technical Information Center (DTIC), Cameron Station, Alexandria, Virginia 22314. Orders will be expedited if placed through the librarian or other person designated to request documents from DTIC. Chanse of address Organizations receiving reports from the U.S. Army Aeromedical Research Laboratory on automatic mailing lists confirm correct address when corresponding about laboratory reports. should Disposition Destroy this report to the originator. when it is no longer needed. Do not return Disclaimer The views, opinions, and/or findings contained in this report are those of the author(s) and should not be construed as an official Department of the Army position, policy, or decision, unless so designated by other official documentation. Citation of trade names in this report does not constitute an official Department of the Army endorsement or approval of the use of such commercial items. Reviewed: CHARLES A. SALTER Director, Biomedical Research Division Applications Rej..qased for publication: \ DAVID H. KARNEY Colonel, MC, FS Commanding V . 4 REPORT DOCUMENTATION Form Approved OMBNO.07044188 PAGE 1 b. RESTRICTIVE MARKINGS la. REPORT SECURITY CLASSIFICATION Unclassified 3 . DISTRIBUTION /AVAILABILITY 2r. SECURITY CLASSIFICATION AUTHORITY 2b.DECWSIFICATION 0. PERFORMING I DOWNGRADING ORGANIZATION USAARL Report Approved for unlimited SCHEDULE 5. MONITORING REPORT NUMBER(S) public OF REPORT release; ORGANIZATION distribution REPORT NUMBER(S) No. 93-2 6a.NAME OF PERFORMING ORGANIZATION U.S. Army Aeromedical Research Laboratory SCADDRESS (Uty, State, and ZIPCook) P.O. Box 577 Fort Rucker, AL 36362-5292 6b. OFFICE SYMBOL (If l pplkable) 7r. NAME OF MONITORING k. NAME OF FUNDING/SPONSORING ORGANIZATION Bb. OFFICE SYMBOL f/f dpPkd&?) 9. PROCUREMENT INSTRUMENT IDENTIFICATION k ADDRESS (City, I 1. TITLE (he/u& Flight stdtd, dfld Suufity ORGANIZATION U.S. Army Medical Research and Development Command 7b. ADDRESS (City, stdtd, dd ZIP CO&) . Fort Detrick Frederick, MD 21701-5012' NUMBER 10. SOURCE OF FUNDING NUMBERS ZIP Co&) PROGRAM ELEMENT NO. PROJECT NO. 3M1627 06027878 878875 SK WORK UNIT ACCESSION NO. . Al? 382 ~dSSifiCdtiOfl) Helmets: How They Work and Why You Should Wear One _. 12. PERSONAL AUTHOR(S) Final Reprinted with permission from WordPerfect of Air Medical Transport, Vol II, pp 19-26, 16. SUPPLEMENTARYNOTATION Published in Journal 17. 18. SUBJECT TERMS (Continue on reverse if necessary COSATI CODES FIELD SUB-GROUP GROUP Publishing Corporation, 1992. c Helmets, flight safety, head injury, dd khtiti bY aviation blotk mmk) medicine 06/05 23104 19. ABSTRACT (Conthe on reverse if necessary dnd McfItifY by block fWmkr) Flight helmets have been in use since the early days of aviation, yet, debate continues regarding their benefit. The most common cause of death in aircraft accidents is head injury, and several studies have concluded that helmets can provide significant protection. This review chronicles the development of the modern helicopter crew helmet, and presents arguments and data supporting their use. Throughout histo?y, man has worn head protection in response to the threat of head injury. Such a w has limitations and drawbacks, but in helicopter aviation, it is effective and worthwhile. , 20. DISTRIBUTION Chief, /AVAILABILITY Scientific )D Form 1473, JUN 86 OF ABSTRACT Information . 2 1. ABSTRACT SECURITY CIASSIF ICATION Center SECURITY CLASSIFICATION OF THIS PAGE UNCLASSIFIRD CLINICAL &PORT ~ is Flight Helmets:-How They Work and Why ShOuldWear One You I John S. Cqwley, MD, MPH; Joseph R. Licln8, MSS; Jamss E. Brucksrt, MD, MPH Introduction ?kE MOST COMMON CAUSEOF DEATH IN accidentsof all typesis head injury.‘” Over the years, several strategieshave been employed to reducethe incidenceof headinjury. Theseincludethe useof lap belt and shoulderharnessrestraintsystems, andmakingthe cockpitlesslethalby eliminating sharp knobs and other protrusions,increasingthe amount of spacearound the occupant,and padding surfaces likely to cause injury.4~5 This paperreviewsanother classicbut surprisinglycontroversial approach-the flighthelmet. aircrdt Helmet History . Protective helmets have been around as long as armed conflict. Originally,their mainpurposewasto protect the head from blows from primitive weapons;later, helmets helpedstopcrossbowboltsandmusket balls.These early helmetsdidn’t permit much mobility of the head and neck-one medievalarmor helmetwornby CharlesV weighedover 40 lb.6 .In’1908, while flying with Orville Wright, an unhelmetedArmy pilot Figure 1. World War I experimental helmet, circa 1918. (Reprinted from Dean B: Helmets and Body Armor in Modern Warfare. 2nd ed, Tuckahoe, MY., Carl J. Pugliese, 1977.) namedThomasSelfridgebecamethe first poweredairplanefatalitywhen he sufferedlethalheadinjuriesin the crash of a Wright Flyer.7 Subsequently,a few Americanaviators, including Lt. Henry “Hap” Arnold(laterGeneralArnold),began The authors above work at the U.S. wearing leather footballhelmets to Army Aeromedical Research Laboratory protect the skull from injury in case at Fort Rucker, Ala. John S. Crowley and of a crash.8 In Great Britain, many James E. Bruckartare majors in the U.S. Army Medical Corps and senior flight early aviatorswore modified hard surgeons;Joseph R. Licina is the safety motorcycleracing helmetsto avoid and occupationalhealth manager. injury.g The Journalof Air Medical Transport l August 1992 1 Figure 2. The APHQ Helmet (official U.S. Army photograph). During World War I, allied instructors andstudentscontinuedto wear theserigid-stylehelmets,while mostoperational pilotsoptedfor soft leather flying helmetsthat afforded betterheadmovementandsomeprotectionfrom wind and cold,but preciouslittle crashprotection.Late in the war, it wasrecognizedthat aviatorsneededmoreballisticprotection, .and a 2 lb steel flight helmet was designed(Figure1js6 Flight helmetsfor bombercrews in World War II were similarly intendedfor ballisticprotection@rimarily from flak), and many lives 19 Figure 3. The SW-4 Hslfnst (offkid U.S. Army photograph). Figure 4. British inventor W.T. Warren in 1912 demonstrating __ c&u&y were savedby thesesteel-plated helmets.6Towardthe end of WorldWar II, helmets were also designedfor impactprotection,mainly for use in new jet aircraft. Test pilots were r encounteringseverebuffetingwhen fly@ at high speedsin turbulence, incurringhead injuriesfrom contact with the aircraftcan~py.~FMecting the headduringan ejectionsequence alsowasa growingconcern. Thus,a p@losophy of headprotection for fixed-wingaviatorsevolved (andenduresto this day) that relied on in-flight escape to protect the fixed-wingaviatorloomcrashforces. For the rotary-wingpilot, who must “ride out”the entire crashsequence inside the aircraft, head protection requirements. are much more demanding. Head Injury Protection Deceleration is expressed in meters per second,2or “g,” where one g is equalto the forceof gravity on the earth’ssurface.The g forceof an impactdependson initialvelocity andavailablestoppingdistance. Head tolerance to a focused impact(bonebreakstrength)ranges from30gfor the noseto NO-200gfor onesquareinchof frontalbone.4The head can tolerate more diffuse impact forces of 300-400g without 20 a rprlng- of Quadrant/Flight Inbmational). skull fractureor concussion. Helmet ing locally procured helmets, it designersendeavorboth to insulate becameevidentthat headprotection the headfrom penetratinginjuryand waseffectiveandnecessary. Table 1 depictsan evolutionof the alsoto reduceglobalhead decelerahelicopterflighthelmetoverthe past tionforcesto the 300grange. The ideal flight helmet should 35 years. New, specializedhelmets weighlessthan4.4 lb, andthe center with integratedvisualdisplays(used of gravityof the helmet-headcombi- by Apachepilots)are not includedin nation should match that of the thisdiscussion. 7Jae AF’H-5 Helmet.With headprounhelmetedheadas closelyas possible. A heavy or unbalancedhelmet tection as the primary driver, the will rapidly cause fatigue or neck Army adopted the Navy’s Aircrew pain and could affect performance. ProtectiveHelmet (APH-5)for wear The helmetshouldbe assmoothand in 1959 (Figure 2), although some streamlined as possible, to avoid Army pilots had beep wearing this cockpit entanglementsand reduce helmetsince1954.liar the effectof tangentialimpacts. The APH-5 providedimpact proApartfrom distributingthe impact tectionby combininga compressible force and providingenergy-absorb- liner with a hardshellconstructedof ing substance, a goodhelmet fulfills resin-stiffenedlayers of fiberglass. a variety of other functions. Understandardtestconditions, a helHelicopters are notoriously noisy, meted headform experienced less and a helmetcan protecthearingas than 25Og.l* Separatefoam sizing well as facilitatecommunication.It padswere providedin three thickalso may serveas a platformfor an nessesto facilitatecustomfitting. oxygen mask or specializednight The retentionsystemconsistedof visionequipment. a padded nylon chin strap screwsecuredto the shell on both sides Modern Flight Helmets andfastenedviaasnap.DuetolimlIn the decade following World t&ions of this single-snapfastener War II, headprotectionwasnotwide system,chin strapstrengthwasonly ly availablefor U.S. Army helicopter 159lb. pilots.However,asaccidentstatistics AlthoughtheNH-5 was,in generbegan to demonstrate fewer head al, well-received, aviatorscomplained injurieswhen aviatorscrashedwear- that the helmet was too hot, too 2 TheJouInnlofAirMedicalT~ l AlJgustl9Q2 4 ! I’ ‘W.I heavy, and too tight.13These prob- assemblyprovidesa comfortablefit lems, combined with other design withoutheadcontactwith any partof deficiencies,spurredthe searchfor a the Styrofoam shell. During an impact,the nylonstrapselongate(up replacement The SPH-4 Helmet. In the mid- to 2%) andthe clipsbend,providing 196Os,the Army determinedthat the impactattenuationprior to headconAPH-5 providedinadequatehearing tact with the styrofoamshell. Drop protection,particularlyin the low fre testsshowthatthe SPH-4limitshead quency soundrange (75-2,000 Hz). decelerationto 300g. Although this Subsequent testsof the Navy’snewer representsa 50gincreasein transmltsound protective helmet (SPH-3) ted energy comparedto the perforproved it superior to the APH-5 in manceof the APH-5,it is still below soundattenuation,earphonedesign, the 300-4OOgthresholdfor concusthe suspensionsystem,microphone, siveinjury.’ The retentionsystemconsistsof a andeaseof fit After severalmoditicationsimprovingthe crashworthiness nylon/cotton assemblyholding the andretentionof the helmet,the SPH- eat-cups,chin strap,and nape strap, 3 was acceptedby the Army as the forming a circular harness around the neck. -Aswith the APH5, chin SPH-4(F&n-e 3). The SPH4 providestwo layersof strapstrengthin earlyversionsof the impact protection via a hard fiber- SPH4 was limited to 150 lb because glassclothandresinshellanda hiih- of a single-snapfastener.The chin densitysingle-piecestyrofoamliner. strapcomfortpad of the APH-5 was A third layer of protectionincludesa downsizedto providea closerfit for suspensionsystem consisting of a the SPH-4,anda maximumallowable leather-covered nylonheadbandwith chin strap elongation of 1.5 in three intersecting crown straps improvedhelmetretention.‘Ihe SPHattachedto the shellwith metalclips. 4 employs the M-87 microphone, Properadjustmentof the suspension which greatly reducesvoice distor- The Journal ofAirMedical Transport l August 1992 3 tion,14and a singleacrylicvisorwith plasticoutercover. Studiesshowedthat aviatorspreferredthe SPH-4overthe APH-5with respectto fit, comfort,noiseattenuation, and the communication system.” As crash experiencewith the SPH-4 accumulated over the years, several improvementswere made. For example, the chin strap was modified to improve helmet retentionby usingstrongermate&l, and by installingtwo snapson one side and a screwpostattachmenton the other. The SPH-dB Helmet. Despitethe overall successof the SPH-4, it did not provide ideal head protection. Army epidemiologists notedthathelicopter crash victims wearing the SPH-4were still at hiih risk for two principal types of head injury: concussion and basilar skull fracture. The latest upgrade to the SPH-4, termed the SPHAB,greatlyreduces the risk of these injuries. Global impact protectionwas improved by reducing the density of the polystyreneliner (to allow the foam 21 to compress more easily) and increasing the liner thickness (to increasestoppingdistance) .I5 The elevatedrisk of basilarskull fracturein SPH4 wearerswastraced to the rigid plastic earcups.16Onefourth of all impacts to the SPH-4 occurto the ear-cupregion, and the lack of energy attenuation in the earcupallowedexcessiveforceto be transmittedto the baseof the skull. The new SPH4B includesa thinner plasticearcup and more liner foam alongthe sidesof the helmet, allowing energyfrom a lateralblow to be dissipatedby fracturing the helmet earctlp.17 Otherchangesin the new SPH4B helmetincludea mod&d chin strap andyoke assemblyto improveretention of the helmet, a thermoplastic liner to improvecomfortand fit, and a Kevlar’“” shell (Table 1). These modificationsresultin a new helmet that is .5 lb lighter than its predecessor,the SPH-4. Ihe SPH-5 Helmet. A civilianversionof the Army’s SPH4B helmet is calledthe SPH-5.It is similarto the SPH4B in weight and performance, but the Kevlarshellof the SPH4B is replaced with ballistic nylon and graphite(Table1). The Alpha Helmet. Developedby HelmetsLimitedof St. Albans,Great Britain,the Alphahelmetwasintended to be usedby helicopterpilo&and fixed-wingpilots.The significantdii ferencebetweenthis helmetand the SPH seriesis the foamliner,whichis integralto the helmet shell, providing extra stiffness with minimal weight18 Fixed-Wing Helmets. Helmets designedexclusivelyfor usein fixedwinga&raft shouldbe carefullyevaluated before purchase. Many of these lightweight helmets are designedto withstandejection and windblastforces,but will not provide sufficientenergy attenuationto prevent injury in a rotary-wingaccident sequence. In addition, helmets designedfor use in a fixed-wingaircraft may not providesufficientprotectionfrom the low frequencynoise often encountered in helicopter flight18 Helmet Effectiveness Althoughprotectiveflight helmets were scornedby some early flight safety authorities,lg others were strongbelievers.GraemeAnderson, in his 1919 aviation medicine textbook,20reported that of 58 training accidentsin his experience,student pilotswere savedfrom headinjuryin 15. “Over and over again the author has seenpilotsthrown out who owe their escapefrom more or less seriousheadwounds,to their safetyhelmets.” Most pre-World War I aviators, on the other hand, were unconvinced of their benefitlg The early helmet developeroften tested his own designs,sometimes beforean amusedand skepticalau& ence(F&me 4), andsometimes by hitting himselfon the headwitha mallet in the privacy of his laboratory.8 Modem helmetengineersuseprecise ly calibrateddrop towersand other devicesto assess helmetperformance. However, the most compelling evidenceregardinghelmeteffectiveness is actualcrashinjurydata Table 1 Characteristics of Helicopter Helmet Detail APHQ SPH-4 SPH-46 SPH-5 ALPHA Year Fielded 1958 1970 1991 NA NA WeighP 3.5 lb 3.3 lb 2.8 lb 2.8 lb 2.8 lb Visor Type Acrylic single Acrylic single Polycarbonate Polycarbonateb dual Polycarbonate dual Shell Material Fiberglass Fiberglass Kevlar graphite Nylon/graphite Kevtar graphite Styrofoam Liner Thickness 0.5 inc 0.4 in 0.6 in 0.6 in 0.75 in Suspension System Leather-covered foam pads Three-strip sling Thermoplastic liner Thermoplastic liner Sling/pad Impact Protection 2509 3009 1809 l6Og ~WI Chin Strap Strength 150 lb 150 lb 440 lb 440 lb 450 lb Earcup Type Eclipse-shaped soft foam 6mm flat flange rigid plastic 3mm contour rigid plastic crushable 3mm contour rigid plastic crushable NA l Weight indudes medium-sizedhedmet.viaor. and communicationaatmmbly. b!Singbandduahrisor ayabm!3amavaiMe. ~linaviaaplitintothmeL3t3uba dtidmetedheadimpausanateurfaoefrom6-nfreefan. 22 Flight Helmets 4 . 1 1 c /’ There have been two studies of emergencymedicalservices(EMS) helmet effectivenessin helicopter aviation programs used flight helaccidents-onein 1961andthe other mets,and29%usedfire-retardant uniin 1991.The first studyexaminedthe forms. Reasons cited for helmet effectof the Army’s APH-5helmeton non-useincludedbadpublicrelations, injury severity during the period high costs,and uncertaineffectiveHoffmanand Shiiskie report1957-1960.13 Fatalheadinjurieswere ness.22 foundto be 2.4 times more common ed in 1990 that helmet use had among unhelmeted occupants of increasedto 21%,noting that 5%of potentiallysurvivablehelicopteracci- responding programs reported at dents than among helmet-wearing least one in-flight injury that could occupants.The author credited the havebeenpreventedby helmetuseF3 then-newAPH-5 helmet with saving 265livesduringthe studyperiod. The 1991 study comparedcrash occupantswearingthe later helmet, the SPH-4, with unhelmeted occupantsof severe,but potentiallysurvivable helicopter accidents from 1972-Bs1 In the crashesstudied,the risk of fatalheadinjurywas6.3 times greater in unhelmeted occupants compared with those wearing the SPH-4 (pcO.01).Unhelmeted occupantsriding in the rear of the crash aircraftwere at even higher risk of fatal head injury (relative risk=7.5; p&01). This latterfindingis particularly relevantbecausecivilianflight medicalpersonnelgenerallyride in the rearof the helicopter. Sincethesestudiesare basedsolely on U.S. Army accident data, the issueof externalvalidityshouldfirst be addressed, that is, can these resultsbe appliedto civilianaviation? Althoughmuchcivil helicopterflying is obviouslydifferent from tactical militaryaviation(controlledairspace, high altitude, busy airports), some civilian flying is very similar. Since civil aviationinjury dataare lacking, it does appear reasonableto apply these military data to civilian helicopter scenarioswith similar flight profiles. . Reluctance to Use Flight Helmets Despite the acceptanceof flight helmets in military helicopter aviation, and the recommendationsof numeroussafetyagencies,the civilian rotary-wing community has been slowto embraceheadprotectionand otheraviationlife supportequipment, suchasfire protectiveflight suitsand flightgloves.In 1939Kruppareported in JAMT that only 13%of civilian The Joumal of Air Medii Transport August 1992 5 These concernsaboutpublicrelations and the patient’s emotional state, while well-intended, ignore three things: (1) a regular aircrew member’s level of risk over a career spanningseveralyears is far higher thanthe patient’srisk duringa single flight; (2) if there shouldbe a crash, consciousflight crewmemberswill be of better use to the patientthan would an unconsciouscrew; (3) by providinga headsetfor the patient, reassuringcommunicationcan actuallybe enhanced.” Conclusions Throughout history, man has worn head protectionin responseto the threatof headinjury.Sucharmor haslimitationsanddrawbacks,but in helicopteraviationit is effectiveand worthwhile.All personnelregularly participating in helicopter flight (civilian or military) should be equippedwith protectiveheadgear. Acknowledgment The views, opinions,and/or find- ings contained in this report are thoseof the authorsand shouldnot be construed as an official Department of the Army position, policy,or decision,unlessso designatedby otherofficialauthority. n References 1. McMeekin RR:AiraatI accidentinvest& tion. In: Fundamentalsof AerospaceMedicine. DeHart RL, (ed). Philadelphia,Lea & Febiier, 1985.pp 762614. 2. Beareh AAz Army Erpcriencewith Crash Injuriesand ProtectiveEquipment.Fort Rucker, 26 Ala., U.S. Army Board for Aviation Accident Research:M-87, M3.3, USABAARWeekly SummaReseal&. 1961. ry1971,13(1):l2. 15. HaleyJL Jr., HundleyTA: &c& dhelmet 3. Sha&an DF. %anahanMO: Injury in U.S. mndrwtionon impacteneqyattenuation.[Poster Army helicoptercrashes,Ott 1979-Sept1985./ Tmuma 1989.29~415422. abstract],New Orleans. La. AerospaceMedical 1978. 4. GlaisterDH: Headinjuryand protection.In: Association, 16.ShanahanDF: Basilarskullfmcturein U.S. AviationMcdicne.Em&g J. King P. (eds). 2nd Armyairaaftao4es1tsUS.USAARLRcportNo. ed, Imdon, Bu@nvorths,1988,pp 174-184. 5. Anonymous:Forewarned and forearmed. 8511. Fort Rucker,Ala., U.S. Army Aeromedical [Editorial].77reAenqUane ReseamhLaboratory,1985. 1913;53471-2. 17. PalmerRw: SPH4 aircrewhelmetimpact andBoa)Annor in Modem 6. DeanB: Helmets Wa&tv. 2nd ed, Tuckahoe,N.Y.. CarlJ. Pugheae, protection improvements 19701990. USAARL. 1977,p 228. RepotiNo. 91-11, Fort Rucker.Ala., U.S. Army 7.,CombsH: Kill Devil Hill. Englewood,Cola., AeromedicalResearchlaboratory,1991. TernstylePressLtd. 1979,p 304. 18. GamblinRw: Flight helmet user require 8. SweetingCG:Cm&at&fag Qthing. smith- mentsandhowtheyarexhieved.Imf+uc&fngsof sonianIn&ution Ress, Washington D.C., 1984, the Twenty-Fipk Annual SAFE Symposium. NewhaU,Calif.,SAFE~1967,pp235240. pp 71-79.. 9. Greer L, Harold A: FQing Clothing-7be 19.Rob&on DH: & DangetvusSky:A Hisb .%nyofitsDevclopment.Shrewsbmy,Engkmd,Air-ty of Aviation Medicine. Seattle, University of life PublishingLtd, 1979,p 15. Wash&ton presS 1973. 10.New Helmet.Awfuloig 1958,4(11):15. 2O.AndexsonHG:MedicalandSu*gicoAs@da ll.BynumJA:UserevaMationsoftwoaimew of Aviatior, London, Oxford University Press, protectivehelmets. USAARU Report69-1, Fort 1919,p 162. Rucker.Ala., U.S. Army AeromedicalResearch 21. CrowleyJS:Shouldhelicopterfrequentflyvi& 1968. erswearheadprote&m?Astudyofhelmeteffec12. Societyof AutomotiveEngineers:Motor 6venessJoccllpMed1991;33:76669. vehicle instrumentpanel laboratoryimpact test 22.KruppaRM:Airmedicalsafety4fonow-up procedure-head area SAE Recommended Fmctice. smvey.jAirMed Tmnsport1989;4(10):1@21. !!iAEJ921b. Pennsyhrani SAE 1979, p 34.133 23. Hoffman DJ. ShinskieDW: Evaluationof 34.134. helmet wearing by medicalhelicopter services 13. U.S. Army Board for Aviation Accident [Ab&act].jAfrMuf7hz@orr1~9(9):79. Research:Army AvMtion AccidentExperience: 24. Foster-BalonJ. Effectsof patientheadset ReportNo. HF 461, Fort Rucker,Ala, USABAAR, utiliaationduring aeromedicalhelicoptertrans1961. port. [Abstract]. / Air Med Transport 1990; 14. U.S. Army Board for Aviation Accident 9(9)91. 6 The Journal of Air Medical Transport August 1992 l